Unlocking the Genetic and Developmental Blueprint: Mechanisms of Animal Body Plan Evolution and Their Biomedical Implications

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the genetic, genomic, and cellular mechanisms governing the evolution of animal body plans.

Unlocking the Genetic and Developmental Blueprint: Mechanisms of Animal Body Plan Evolution and Their Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the genetic, genomic, and cellular mechanisms governing the evolution of animal body plans. It explores foundational concepts from evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo), including the pivotal role of Hox genes and ancestral body plans. We then detail modern methodological approaches, such as comparative genomics and transcriptomics, highlighting their application in identifying body size-associated genes (BSAGs) and pathways in models from gobies to snakes. The review addresses key challenges in the field, including distinguishing homologous from convergent traits, and validates findings through cross-phyla comparisons and fossil evidence. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis underscores how understanding evolutionary mechanisms provides profound insights into fundamental developmental processes, with potential implications for understanding growth regulation and disease.

The Genetic and Developmental Foundations of Animal Body Plans

Hox genes, a family of homeobox-containing transcription factors, represent one of the most profound discoveries in developmental biology, providing fundamental insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying animal body plan evolution. These genes encode proteins containing a highly conserved 60-amino acid DNA-binding motif known as the homeodomain, which allows them to bind specific regulatory sequences and control the expression of downstream target genes [1] [2]. First identified through dramatic homeotic transformations in Drosophila melanogaster—where mutations caused structures to develop in incorrect locations, such as legs growing from the head in place of antennae—Hox genes have since been recognized as master regulators of anterior-posterior (AP) axis patterning across bilaterian animals [1]. Their deep evolutionary conservation, coupled with their precise spatiotemporal expression patterns, positions Hox genes as central players in the genetic toolkit that has shaped animal diversity over hundreds of millions of years.

The concept of the "Hox code" emerges from the precise correspondence between the combinatorial expression of Hox genes along the AP axis and the morphological identity of body segments [3] [4]. This code functions as a positional addressing system, providing cells with information about their location within the embryo and instructing them to develop appropriate segment-specific structures. The regulatory logic of this system exhibits remarkable conservation from invertebrates to vertebrates, though the genomic organization of Hox genes has undergone significant modifications through evolution, including cluster duplications and gene diversification that have contributed to the emergence of novel morphological features in vertebrate lineages [5] [6].

Molecular Organization and Evolutionary History of Hox Clusters

Genomic Arrangement and Collinearity Principles

Hox genes are characterized by their unique genomic organization into clusters and the phenomenon of collinearity, which describes the precise correspondence between the physical order of genes on the chromosome and their expression patterns along the AP axis [6]. This organizational principle manifests in two distinct forms: spatial collinearity, where genes at the 3' end of the cluster are expressed in anterior regions while those at the 5' end are expressed in progressively more posterior regions; and temporal collinearity, where 3' genes are activated earlier in development than their 5' counterparts [7] [6]. In Drosophila, the eight Hox genes are arranged in a single cluster split into two complexes (Antennapedia and Bithorax), while mammals possess 39 Hox genes distributed across four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) located on different chromosomes [1] [6].

The molecular mechanisms governing collinearity involve progressive chromatin remodeling along the cluster, with CTCF binding sites playing a crucial role in the sequential activation of Hox genes from 3' to 5' [8]. This sequential activation creates nested domains of Hox gene expression that establish a combinatorial code for positional identity along the AP axis. The conservation of this regulatory logic across diverse animal phyla underscores its fundamental importance in animal development and its contribution to the evolution of body plans.

Cluster Duplications and Vertebrate Diversification

The expansion of Hox clusters through genome duplication events represents a pivotal chapter in vertebrate evolution. Invertebrates typically possess a single Hox cluster, while vertebrates exhibit multiple clusters resulting from two rounds of whole-genome duplication early in vertebrate evolution [5] [2]. Mammals retained four Hox clusters (A, B, C, and D), while teleost fishes underwent an additional duplication event, resulting in up to eight Hox clusters [5] [6]. These duplication events provided raw genetic material for functional diversification through several mechanisms:

- Subfunctionalization: Partitioning of ancestral functions among paralogs

- Neofunctionalization: Acquisition of novel functions by duplicated genes

- Adaptive diversification: Divergent selection acting on both paralogs [2]

Evidence from evolutionary developmental biology indicates that positive Darwinian selection acted on the homeodomain immediately after cluster duplications, particularly at sites involved in protein-protein interactions rather than DNA-binding surfaces [2]. This adaptive evolution following duplication events contributed to the functional diversification of Hox genes and facilitated the emergence of morphological novelties in vertebrate lineages, including specialized appendages and more complex axial organization.

Table 1: Hox Cluster Organization Across Animal Lineages

| Organismal Group | Number of Hox Clusters | Total Hox Genes | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit Fly (Drosophila) | 1 | 8 | Split into Antennapedia and Bithorax complexes |

| Amphioxus | 1 | 15 | Representative of ancestral chordate condition |

| Mammals | 4 | 39 | Clusters located on different chromosomes |

| Teleost Fishes | 7-8 | 45-47 | Additional cluster duplication event |

Hox Gene Function in Invertebrate Model Systems

Drosophila melanogaster: The Paradigmatic System

The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster serves as the foundational model for understanding Hox gene function, with pioneering work by Ed Lewis and others revealing the principles of homeotic gene regulation [1]. In Drosophila, the eight Hox genes are organized in a single cluster and specify the identity of segments along the AP axis through precisely demarcated expression domains. The functional hierarchy of Hox genes in flies follows an posterior prevalence rule (formerly called "posterior dominance"), where more posteriorly expressed Hox proteins can repress the function of more anteriorly expressed ones, ensuring proper segmental identity [6].

Classic loss-of-function mutations in Drosophila Hox genes result in homeotic transformations where one body segment develops the identity of another. For example, mutations in Ultrabithorax (Ubx) cause the third thoracic segment to develop like the second, resulting in flies with two sets of wings instead of the normal one wing pair and one haltere pair [1]. Conversely, ectopic expression of Hox genes in inappropriate segments leads to opposite transformations, such as the famous Antennapedia mutant where legs develop in place of antennae. These dramatic phenotypes demonstrated that Hox genes function as master switches controlling developmental pathways that determine segment identity.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Target Gene Networks

The precision of Hox-mediated patterning in Drosophila depends on sophisticated regulatory mechanisms that establish and maintain expression boundaries. These include:

- Auto- and cross-regulatory interactions among Hox genes that maintain expression patterns

- Gap and pair-rule gene inputs that initiate Hox expression domains in the early embryo

- Chromatin-modifying complexes such as Polycomb and Trithorax groups that maintain repressed or active states

- MicroRNAs that provide post-transcriptional fine-tuning of Hox expression levels [6]

Hox proteins execute their morphological functions by regulating batteries of downstream target genes involved in processes including cell proliferation, cell shape, adhesion, and differentiation. For example, the Ubx protein directly represses wingless in the haltere imaginal disc, contributing to the development of this balancing organ instead of a second pair of wings [1]. The ability of Hox proteins to coordinate complex morphological outcomes through regulation of diverse target gene networks underscores their role as master regulators of development.

Vertebrate Axial Patterning and the Hox Code

Somitogenesis and Vertebral Identity

In vertebrates, Hox genes play a crucial role in patterning the axial skeleton, which derives from somites—transient, segmented structures that form sequentially along the AP axis during embryogenesis [3] [4]. The vertebral column exhibits remarkable regionalization, with distinct morphologies characterizing cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and caudal vertebrae, despite their similar embryonic origins. This regional specificity is directed by the combinatorial expression of Hox genes, which provide positional information to somites and their derivatives [3] [8].

Extensive research in mouse models has demonstrated that loss-of-function mutations in specific Hox genes lead to homeotic transformations of vertebral identity. For example, simultaneous inactivation of all three genes in the Hox10 paralogous group (Hoxa10, Hoxc10, and Hoxd10) results in the transformation of ribless lumbar vertebrae into rib-bearing thoracic-like vertebrae [5]. Conversely, misexpression of Hox genes in inappropriate axial locations can cause anterior or posterior transformations, such as the development of cervical vertebrae with thoracic characteristics when Hox genes normally restricted to more posterior regions are expressed anteriorly [4]. These genetic studies have firmly established that Hox genes are key determinants of vertebral morphology along the AP axis.

Recent Insights from Human Developmental Studies

A landmark 2024 study utilizing single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and in-situ sequencing of human fetal spines between 5 and 13 weeks post-conception has provided unprecedented resolution of Hox gene expression during human development [8]. This research revealed several novel insights:

- A conserved set of 18 positionally informative Hox genes was identified across stationary cell types in the developing spine, exhibiting consistent anterior-posterior expression patterns

- Neural crest cell derivatives unexpectedly retain the anatomical Hox code of their origin while also adopting the code of their destination, creating a unique "source code" signature

- The antisense gene HOXB-AS3 exhibited strong positional specificity for the cervical region, suggesting previously unrecognized regulatory functions

- Distinct Hox expression patterns were observed in dorsal versus ventral domains of the spinal cord, providing insights into motor pool organization [8]

These findings in human development highlight both the deep conservation of Hox-mediated patterning principles and human-specific aspects of Hox gene regulation that may contribute to unique features of human anatomy.

Table 2: Key Hox Gene Functions in Vertebrate Axial Patterning

| Hox Paralogue Group | Primary Axial Expression Domain | Functional Role | Phenotype of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox1-5 | Cervical vertebrae | Specify cervical identity | Anterior homeotic transformations |

| Hox6-9 | Thoracic vertebrae | Promote rib development | Loss of ribs, posterior transformations |

| Hox10 | Lumbar vertebrae | Suppress rib formation | Ectopic ribs in lumbar region |

| Hox11 | Sacral vertebrae | Specify sacral identity | Defects in sacrum formation |

| Hox13 | Caudal vertebrae | Pattern tail structures | Truncated axial skeleton |

Evolutionary Diversification of Body Plans Through Hox Gene Modifications

Axial Elongation and Regionalization in Squamates

The evolution of snake body plans provides a compelling natural example of how modifications to Hox gene expression can drive dramatic morphological change. Snakes exhibit a dramatically elongated body with hundreds of pre-cloacal vertebrae, most of which bear ribs, and a reduction or loss of limbs and sternum [5]. Early interpretations suggested that the snake axial skeleton was "deregionalized" with reduced morphological differentiation along the AP axis. However, recent geometric morphometric analyses have revealed that snakes actually possess distinct cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebral regions, though with modified boundaries compared to limbed lizards [5].

Expression analyses in snake embryos showed that Hoxa10 and Hoxc10, which in mammals and lizards suppress rib formation in the lumbar region, are expressed in rib-bearing regions of the snake axial skeleton [5]. Surprisingly, transgenic experiments demonstrated that the snake Hoxa10 protein retains the ability to suppress rib formation when expressed in mice, indicating that the functional change lies not in the Hox protein itself but in its regulatory context [5]. Instead, a polymorphism was identified in a Hox/Pax-responsive enhancer that renders it unable to respond to rib-suppressing Hox10 proteins, providing a molecular explanation for the extended ribcage of snakes [5]. This example illustrates how changes in regulatory elements rather than protein-coding sequences can drive major evolutionary transformations.

Limb Reduction and Axial Specification

The limbless condition of snakes is also linked to modifications in Hox gene expression, particularly in the lateral plate mesoderm that gives rise to limb buds. In limbed vertebrates, Hox genes define the position along the AP axis where limb buds will initiate, with specific combinations of Hoxc6 and Hoxc8 expression marking the forelimb field [5] [1]. In snakes, the expression domains of these genes are shifted, potentially contributing to the failure of limb bud initiation or outgrowth. Additionally, changes in the expression of Hox genes in the somatic mesoderm likely influence the development of the girdle skeletons that support the limbs.

The correlation between shifts in Hox expression boundaries and morphological changes in the axial skeleton extends beyond snakes to other vertebrate groups. Comparative analyses across amniotes have revealed that the evolutionary differences in the axial skeleton correspond to changes in the expression domains of Hox genes [5]. For example, the transition between cervical and thoracic vertebrae, defined by the first vertebra bearing ribs, correlates with the anterior expression boundary of Hoxc6 in multiple species, with shifts in this boundary associated with changes in the number of ribless cervical vertebrae [5]. These comparative studies underscore how relatively simple modifications to the Hox code can generate substantial morphological diversity through evolution.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies in Hox Biology

Genetic Manipulation Techniques

Our understanding of Hox gene function has been propelled by sophisticated genetic approaches in model organisms. In mice, targeted gene disruption through homologous recombination has been particularly informative, revealing the functions of individual Hox genes and paralogous groups [3] [1]. Because of functional redundancy among paralogs, single knockouts often yield subtle phenotypes, while compound mutants lacking multiple paralogs exhibit dramatic homeotic transformations. For example, inactivation of all three Hox10 paralogs (Hoxa10, Hoxc10, and Hoxd10) causes the transformation of lumbar vertebrae into thoracic-like vertebrae with ectopic ribs, demonstrating this group's essential role in suppressing rib development [5].

More recent approaches include:

- Conditional knockout strategies using Cre-loxP systems to eliminate Hox function in specific tissues or at specific developmental stages

- Gain-of-function experiments through targeted misexpression using tissue-specific promoters

- Interspecies transgenic approaches, such as expressing snake Hox genes in mice to test functional conservation [5]

- CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to create precise mutations in regulatory elements or coding sequences

These genetic manipulations have been complemented by biochemical studies of Hox protein function, including analysis of DNA-binding specificity, protein-protein interactions, and transcriptional regulatory properties.

Genomic and Transcriptomic Analyses

Recent technological advances have revolutionized our ability to study Hox gene regulation and function at genome-wide scales. Single-cell RNA sequencing has enabled the resolution of Hox expression patterns at unprecedented cellular resolution, as demonstrated in the developing human spine [8]. Spatial transcriptomics techniques preserve anatomical context while providing genome-wide expression data, allowing Hox expression domains to be mapped directly onto tissue architecture. Additionally, chromatin conformation capture methods have revealed the three-dimensional organization of Hox clusters and how long-range regulatory interactions control their sequential activation.

The integration of these high-throughput approaches with classic genetic and embryological techniques represents the cutting edge of Hox biology. For example, the combination of single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial transcriptomics in human fetal tissues has revealed previously unappreciated complexities of Hox expression in neural crest derivatives and specific neuronal populations [8]. These methodologies continue to provide new insights into the regulation and function of these fundamental patterning genes.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Hox Gene Research

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Model Systems | Drosophila melanogaster, Mouse (Mus musculus), Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Functional analysis through genetic manipulation |

| Genome Editing Technologies | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, Zinc Finger Nucleases | Targeted mutation of Hox genes and regulatory elements |

| Transcriptional Profiling | Single-cell RNA-seq, Spatial transcriptomics, In-situ hybridization | Mapping expression patterns with cellular resolution |

| Protein Detection Methods | Immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, Protein-binding assays | Localization and interaction studies of Hox proteins |

| Computational Resources | Phylogenetic analysis tools, Genomic browsers, Single-cell data portals | Evolutionary and expression pattern analyses |

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Hox Genes in Hematopoiesis and Leukemia

While traditionally studied in the context of embryonic development, Hox genes have significant clinical relevance, particularly in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Specific HOX genes, especially members of the HOXA cluster, are highly expressed in certain subtypes of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and appear to play functional roles in disease pathogenesis [9] [10]. Approximately 70% of AML cases show overexpression of HOXA9, which is associated with poor prognosis and appears to maintain leukemogenesis through promoting self-renewal of myeloid leukemia cells [10].

A dominant HOX gene expression signature is particularly characteristic of AML carrying NPM1 mutations, which account for approximately 30% of all AML cases [10]. In these leukemias, HOXA9 and its cofactor MEIS1 are highly expressed, driving leukemogenesis through effects on CEBPα and lysine methyltransferase 2A (KMT2A) [10]. This molecular understanding has led to the development of targeted therapies, including menin inhibitors that disrupt the Menin-KMT2A interaction critical for HOXA9 expression in NPM1-mutant AML [10]. Clinical trials of menin inhibitors such as revumenib (SNDX-516) and ziftomenib (KO-539) have shown promising response rates of 40-60% in heavily pretreated patients with KMT2A-rearranged or NPM1-mutant AML [10].

Hox Genes as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets

Beyond their roles in leukemia, HOX genes are misregulated in various other cancers, with expression patterns that differ based on tissue and tumor type [9]. Comprehensive analyses comparing HOX gene expression across multiple cancer types using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) projects have identified distinctive HOX expression signatures that can discriminate between tumor and healthy samples [9]. For example, glioblastoma multiforme shows differential expression of 36 HOX genes compared to healthy brain tissue, while other cancer types such as esophageal carcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and stomach adenocarcinoma show altered expression of at least a third of all HOX genes [9].

The tissue-specific and cancer-type-specific patterns of HOX gene misregulation suggest potential applications as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers. Additionally, the functional importance of HOX genes in certain cancers positions them as potential therapeutic targets. However, targeting transcription factors directly has proven challenging, leading to strategies focused on upstream regulators or downstream effectors of HOX protein function. Further understanding of Hox gene regulation and function in both normal development and disease states will continue to inform therapeutic development for cancer and potentially other conditions.

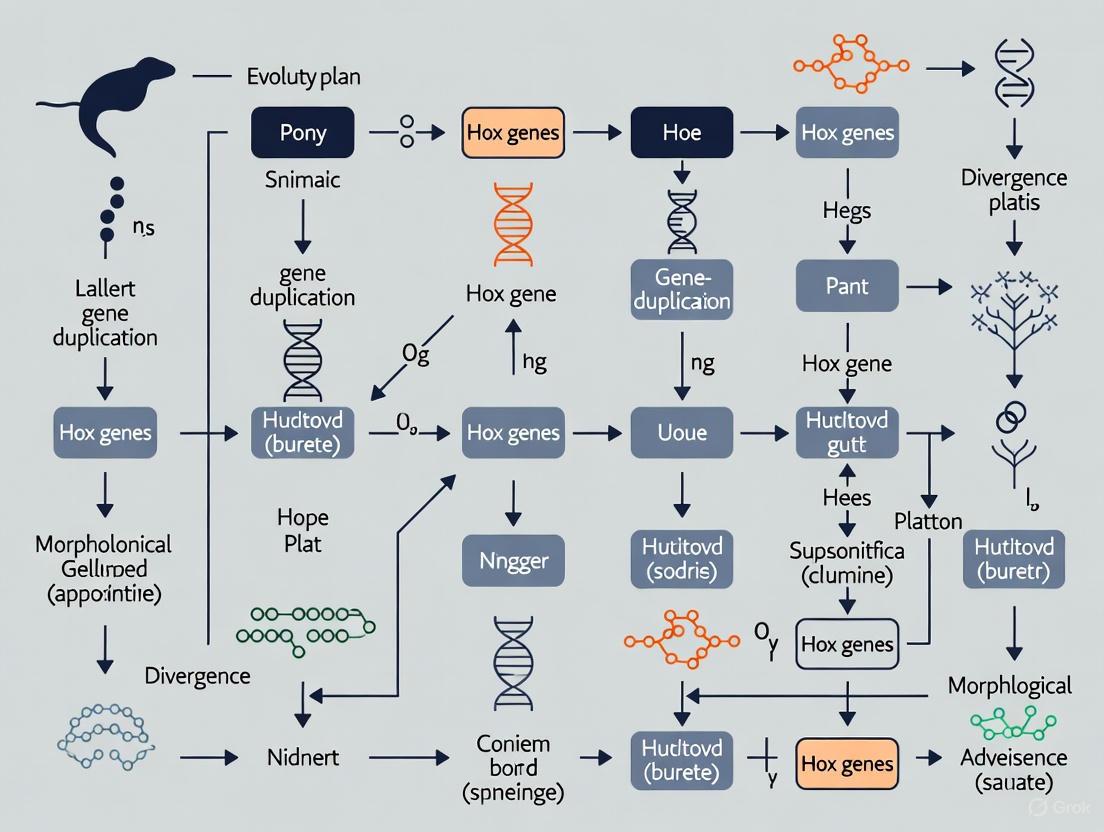

Visualizing Hox Gene Regulation and Function

Figure 1: Regulatory Logic of Hox Gene Patterning. The establishment of Hox gene expression involves integration of chromatin state, signaling gradients, and transcription factor inputs to generate precise expression patterns that direct morphological outcomes.

Figure 2: Evolutionary Trajectories of Hox Cluster Duplication. Gene duplication events provide raw material for functional diversification through multiple mechanisms that ultimately contribute to morphological evolution.

Hox genes represent a paradigmatic example of how conserved genetic toolkits can be adapted and modified through evolution to generate tremendous biological diversity. From their initial discovery as regulators of segment identity in fruit flies to their recognized roles in patterning the vertebrate axial skeleton and their clinical importance in human disease, the study of Hox genes has continually provided fundamental insights into developmental and evolutionary processes. The deep conservation of the Hox code across bilaterian animals underscores its fundamental importance in animal body planning, while species-specific modifications to this code reveal the flexibility that enables morphological diversification.

Future research directions in Hox biology will likely focus on several key areas: (1) understanding the three-dimensional chromatin architecture and epigenetic mechanisms that govern Hox cluster regulation; (2) elucidating the complete networks of target genes through which Hox proteins orchestrate morphological outcomes; (3) exploring the non-canonical functions of Hox genes in processes beyond AP patterning, such as organogenesis and cell differentiation; and (4) leveraging knowledge of Hox gene function for therapeutic applications, particularly in cancer and regenerative medicine. As technological advances continue to provide new windows into gene regulation and function at unprecedented resolution, Hox genes will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of research aimed at understanding the fundamental principles of animal development and evolution.

The reconstruction of ancestral body plans is a central goal in evolutionary developmental biology. Among bilaterian animals, the Spiralia—a vast and morphologically diverse clade including annelids, mollusks, platylhelminths, and nemerteans—offer unique and critical insights into the anatomy, development, and genetics of the protostome ancestor and, by extension, the last common ancestor of all bilaterians [11] [12]. The Spiralia constitute one of the three major bilaterian clades, alongside Ecdysozoa (e.g., arthropods, nematodes) and Deuterostomia (e.g., chordates, echinoderms) [11]. Historically, molecular genetic research has focused disproportionately on ecdysozoan and deuterostome model systems, creating a significant gap in understanding that spiralians are uniquely positioned to fill [11].

The defining characteristic of spiralian development is a highly conserved mode of early embryogenesis known as spiral cleavage [12] [13]. This stereotypic pattern of cell division is not merely a curiosity of embryology; it represents a foundational blueprint from which the diverse adult body plans of these animals are constructed. Recent phylogenetic analyses confirm that this developmental program was almost certainly present in the common ancestor of the Lophotrochozoa, a superphylum within Protostomia, underscoring its ancient origin and evolutionary importance [12] [14]. The study of spiralian development thus functions like a "time machine," allowing researchers to extrapolate back in time to understand the developmental mechanisms that shaped some of the earliest animals on Earth [15] [16]. This review synthesizes classic and contemporary findings from spiralian embryology to propose a more refined model of the bilaterian ancestor, with a particular focus on axial patterning and segmentation.

The Spiral Cleavage Fate Map: A Conserved Blueprint with Implications for Ancestral Polarity

The spiral cleavage program is a quintessential example of evolutionary conservation, providing a cellular framework upon which hundreds of millions of years of diversification have been built. Its name derives from the conspicuous oblique orientation of cell divisions, which creates a spiraling arrangement of daughter cells, or micromeres, atop larger macromeres [11] [17].

Core Principles of Spiral Cleavage

- Quadrant Architecture: After initial divisions, the embryo is typically composed of four quadrants (A, B, C, D), each giving rise to a distinct set of descendant cells with predictable fates [11] [17].

- Micromere Quartets: Micromeres are born in successive quartets (1a-1d, 2a-2d, etc.), each contributing to specific embryonic tissues.

- D Quadrant Specialization: A pivotal and highly conserved feature is the dominance of the D quadrant, which gives rise to the mesentoblast (4d cell), the primary progenitor of mesodermal tissues and a key organizer of the embryonic axis [17].

Revision of a Classic Dogma

A significant advance in spiralian embryology has been the revision of the long-held, simplistic rubric "D is dorsal." Modern cell-lineage tracing in nemerteans and flatworms has revealed a more complex reality: the dorsal-ventral (DV) midline is not fixed to a single quadrant throughout development [11]. Instead, the fates of odd- and even-numbered micromere quartets are rotated by 45 degrees relative to each other. Consequently, the definitive dorsal midline often forms at the boundary between the C and D quadrants, not squarely within the D quadrant [11]. This nuanced understanding of the fate map, evident in 19th-century drawings but later forgotten, highlights the danger of oversimplifying complex biological patterns and provides a more accurate framework for understanding axial patterning in the spiralian ancestor.

Table 1: Developmental Fate of Key Blastomeres in Spiralian Embryos

| Blastomere | Developmental Origin | Primary Tissue Contributions | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesentoblast (4d) | Fourth quartet micromere from the D quadrant | Mesoderm, endoderm (in some taxa) | Highly conserved; primary source of internal mesodermal tissues; an organizing center in many species [17]. |

| 2d (Somatoblast) | Second quartet micromere from the D quadrant | Ectoderm of the trunk (body wall) | In annelids, becomes a ectodermal growth zone for the trunk; illustrates early specification of somatic tissues [17]. |

| First Quartet Micromeres | First set of micromeres (1a-1d) | Anterior ectoderm, nervous system, head structures | Forms head-specific structures, indicating early specification of the anteroposterior axis [11] [17]. |

| Macromeres (A-C) | Primary yolk-bearing cells (A, B, C quadrants) | Nutritive (yolk), endoderm | Often serve a primarily nutritive role, with their developmental potential reduced in derived lineages [17]. |

Axis Formation and Segmentation: A Tale of Two Annelids

The formation of the primary body axes—anteroposterior (AP), dorsoventral (DV), and left-right (LR)—is a fundamental event in embryogenesis. Research in spiralians, particularly annelids, has revealed both deeply conserved genetic mechanisms and surprising phylum-specific variations in how these axes are established.

Hox Genes and the Patterning of the Anteroposterior Axis

The Hox genes, a conserved family of transcription factors, are renowned for their role in specifying regional identity along the AP axis in bilaterians [11]. Spiralians are no exception, but their study has revealed intriguing differences in the timing and deployment of this genetic toolkit.

- Expression in Polychaetes (e.g., Chaetopterus): In polychaete annelids, which develop via a trochophore larva, Hox genes are expressed in a temporal and spatial collinear fashion within a posterior growth zone from which new segments bud sequentially [11]. This mode—where Hox expression is linked to the process of segment formation—is considered ancestral for annelids and potentially for spiralians more broadly.

- Expression in Clitellates (e.g., Helobdella, Tubifex): In leeches and oligochaetes, which develop directly without a larval stage, segments are produced by teloblastic stem cells. Here, segment identity appears to be determined by the stem cell lineage itself, with Hox gene expression initiating later, during organogenesis, after segment boundaries are already established [11]. This suggests that in these derived annelids, Hox genes may function in fine-tuning segmental morphology rather than in its initial specification.

This disparity indicates that the genetic machinery for AP patterning can be deployed differently over evolutionary time, with a potential evolutionary shift from a Hox-dependent growth zone mechanism to a cell lineage-based mechanism in certain spiralian lineages.

Table 2: Comparison of Axial Patterning Mechanisms in Spiralian Models

| Feature | Polychaete Annelids (e.g., Chaetopterus) | Clitellate Annelids (e.g., Helobdella, Tubifex) | Mollusks (Basal Groups) | Cnidarians (e.g., Nematostella) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hox Expression Onset | During segment formation in posterior growth zone [11] | During organogenesis, long after segments form [11] | Data needed for early stages | In early development, defining segments [15] [16] |

| Segmentation Mechanism | Sequential addition from posterior growth zone [11] | Teloblastic cell lineages [11] | Not applicable (non-segmented) | Radial segmentation under Hox control [15] [16] |

| Segment Polarity Role of engrailed | Data needed | No critical role in cell signaling (based on ablation studies) [11] | Data needed | Polarization of segments under Hox control [15] [16] |

| Mesoderm Origin | From mesentoblast (4d) [17] | From mesentoblast (4d) and teloblasts [11] [17] | From mesentoblast (4d) [17] | Not applicable |

The Enigma of Segmentation and Segment Polarity

The question of whether segmentation in annelids, arthropods, and chordates is homologous or independently evolved remains a subject of intense debate [11]. Molecular investigations of the segment polarity gene engrailed (en) have been particularly illuminating. In the fruit fly Drosophila, en-expressing cells are crucial organizers that pattern the entire segment through intercellular signaling [11].

However, laser ablation experiments in the leech Helobdella have yielded dramatically different results. When the en-expressing blast cell sublineage is ablated, the development of adjacent cells proceeds normally, showing no dependence on signals from the en-expressing cells [11]. This key finding suggests that the intercellular signaling network downstream of engrailed, which is fundamental to arthropod segmentation, is not conserved in this annelid. This points to either a non-homologous origin of segmentation or, perhaps more likely, a profound evolutionary divergence in the cellular execution of a shared ancestral genetic program.

A Cellular Perspective on Body Plan Evolution

The evolution of body plans ultimately occurs through changes in the behavior of embryonic cells. The spiralian embryo provides a window into how cellular characteristics such as cell fate determination, induction, and morphogenesis have been modified over deep evolutionary time.

The Spectrum of Cell Fate Determination

Spiralians exhibit a range of strategies for specifying cell fates, from highly regulative (where cell fate is determined by interactions with neighbors) to highly determinative/mosaic (where cell fate is intrinsic and established early via asymmetric cell divisions) [17].

- Regulative Ancestors: Studies on acoel flatworms like Childia suggest the ancestral spiralian condition may have been highly regulative, as isolated blastomeres can regulate to form complete, normal-sized worms [17].

- Evolution of Mosaic Development: The rigid, stereotypic pattern of spiral cleavage may have provided a stable scaffold that allowed for the evolution of more determinative (mosaic) development. This enables the rapid production of a feeding larva with minimal energy investment, a clear selective advantage [17]. The consistent specification of the D quadrant and the mesentoblast across most spiralian phyla is a prime example of this evolutionary stabilization.

Inductive Interactions and the Origins of Germ Layers

A critical developmental event conserved across metazoans is the inductive interaction between the ectoderm and endomesoderm, which allows for the specialization of germ layers and drives gastrulation [17]. This interaction is evident even in the most regulative spiralians and is considered a fundamental, ancient metazoan characteristic. In annelids, further inductive interactions between mesoderm (from the mesentoblast) and ectoderm are required for the development of the trunk region, highlighting how conserved cellular "dialogues" have been co-opted to build more complex body plans [17].

Experimental Approaches in Spiralian Evolutionary Developmental Biology

Modern insights into spiralian development rely on a suite of classical and modern techniques that allow researchers to probe cell lineage, gene function, and evolutionary relationships.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for studying spiralian development, from empirical data collection to evolutionary inference.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Laser Ablation of Specific Blastomeres

Objective: To determine the autonomy of cell fate and the role of specific cells in embryonic patterning and cell signaling [11].

- Embryo Preparation: Collect and stage embryos at the desired cleavage stage (e.g., when target blastomeres like the O/P lineage in Helobdella are clearly identifiable).

- Mounting: Immobilize embryos in a suitable chamber with a soft agarose substrate or in a microinjection dish.

- Ablation: Using a laser microbeam coupled to a compound microscope, precisely target the identified blastomere. The laser energy is calibrated to kill the cell without damaging surrounding cells.

- Culture & Observation: Allow the operated embryos to continue development in a controlled environment. Monitor for morphological defects and assay for molecular markers (e.g., via in situ hybridization for genes like engrailed) in adjacent cells.

- Analysis: Compare the development of experimental embryos to unoperated controls. The absence of effects on neighboring cells, as seen in Helobdella engrailed ablations, indicates that the ablated cell does not serve an essential inductive role [11].

Protocol 2: Teloblast Frameshift or Transplantation

Objective: To investigate the autonomy of segment identity specification in clitellate annelids [11].

- Donor and Host Preparation: Use embryos from the same developmental stage. For frameshift experiments, microsurgically reposition a single teloblast (e.g., an O/P teloblast) so that its progeny are generated out of sync with the other teloblastic lineages [11]. For transplantation, isolate a teloblast from a donor embryo.

- Transplantation: Transplant the isolated donor teloblast into a host embryo, potentially replacing a host teloblast or adding it ectopically.

- Lineage Tracing: Label the transplanted or frameshifted teloblast with a fluorescent lineage tracer (e.g., dextran conjugates) to track the fate of its progeny.

- Analysis: Assess the identity of the segments or tissues generated by the manipulated teloblast. In Tubifex, transplanted teloblasts contribute to segments consistent with their intrinsic identity (number of divisions completed), not their new position, indicating an early, lineage-intrinsic specification of identity [11] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Models in Spiralian Evolutionary Developmental Biology

| Reagent / Model Organism | Category | Key Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Lineage Tracers (Fluorescent Dextrans) | Chemical Tracer | Injected into individual blastomeres to fates of their clonal descendants, enabling fate map construction [11] [13]. |

| Helobdella robusta (Leech) | Model Organism | Clitellate annelid; ideal for teloblast lineage analysis, laser ablation, and studying mosaic development [11]. |

| Chaetopterus variopedatus (Polychaete Worm) | Model Organism | Polychaete annelid; used to study the ancestral mode of Hox gene expression during posterior growth zone segmentation [11]. |

| Nematostella vectensis (Sea Anemone) | Model Organism | Non-bilaterian outgroup; provides a baseline for understanding the evolution of bilaterian features like segmentation and Hox patterning [15] [16]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Molecular Technique | Allows genome-wide profiling of gene expression across different embryonic regions, revealing segment-specific gene networks without a priori knowledge [15]. |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) | Functional Tool | Knocks down gene function to test the role of specific genes (e.g., Hox genes, signaling molecules) in development. |

| Trochin & Lophotrochin | Spiralian-Specific Genes | Novel genes identified as specific markers for ciliary bands, key spiralian structures, highlighting clade-specific innovation [17]. |

Synthesis and Evolutionary Implications: A Revised View of the Bilaterian Ancestor

Integrating evidence from spiralian embryology allows for a more confident reconstruction of the bilaterian ancestor's developmental repertoire. The conservation of spiral cleavage across a vast swath of the protostome tree strongly suggests that the bilaterian ancestor possessed a stereotyped, spiralian-like pattern of early cleavage with a specialized D quadrant giving rise to the mesoderm via a mesentoblast [11] [17]. This ancestor was likely capable of significant regulative development, with determinative elements becoming more prominent in various descendant lineages [17].

The genetic toolkit for axial patterning was already highly sophisticated in this ancestor. The presence and functional importance of Hox genes in patterning the AP axis are indisputable, but spiralians show that the regulatory logic of how this toolkit is deployed can be flexible—tied to a growth zone in some lineages and to stem cell lineages in others [11]. Similarly, while key signaling pathways like Nodal (for LR asymmetry) and neurotrophin (for nervous system development) have bilaterian origins, their specific functions have been extensively modified [19].

Diagram 2: Evolution and deployment of the ancestral genetic toolkit. While the core genes are conserved, their functional deployment and necessity in development can diverge significantly between lineages.

The case of engrailed provides a powerful lesson in distinguishing between different levels of homology. The engrailed gene itself is homologous across bilaterians, but its role in segment polarity signaling—a function critical in arthropods—is not conserved in annelids [11]. This implies that the elaborate signaling network for segment polarity seen in flies is not an ancestral bilaterian characteristic. Therefore, while segmentation itself may be homologous, the molecular mechanisms for polarizing segments may have evolved independently or been extensively rewired in different lineages. Recent work in cnidarians like Nematostella further blurs the lines, showing that the genetic programs for segmentation and polarization are more ancient than the bilaterian ancestor, even if they were used to build different types of body plans [15] [16]. This supports a "Lego block" model of evolution, where a common set of genetic building blocks is reassembled in novel ways to generate the spectacular diversity of animal forms [15].

The foundational framework of the Modern Synthesis (MS), which integrated Mendelian genetics with Darwinian natural selection, has been repeatedly challenged by new biological disciplines, particularly evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo). This review examines the historical and contemporary criticisms of the MS, often mislabeled as "Neo-Darwinism," and assesses calls for its extension or replacement, such as the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES). We trace these arguments from early critics like Conrad Waddington and Stephen Jay Gould to modern proponents who argue that the MS excessively focused on genes and natural selection while ignoring developmental processes, epigenetics, and macroevolution. By synthesizing recent research on the genetic toolkit for body plan development and presenting quantitative data on evolutionary design principles, this work argues that many proposed challenges can be accommodated within an expanded, pluralistic evolutionary framework, although conceptual integration of structuralism and macroevolution remains ongoing.

The Modern Synthesis (MS) of the mid-20th century successfully unified population genetics, paleontology, and systematics, establishing a robust framework for understanding evolutionary change through natural selection acting on genetic variation. However, this framework has faced persistent criticism for its perceived gene-centrism and exclusion of developmental biology. Contemporary evolutionary biology now reflects a conceptually split landscape with multiple coexisting analytical frameworks, including adaptationism, mutationism, neutralism, and selectionism [20].

Recent decades have witnessed renewed calls for a more Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES) that overcomes the perceived limitations of the MS framework. Some radical critics argue for entirely abandoning the current evolutionary framework in favor of entirely new paradigms. These criticisms are not new; they have resurfaced repeatedly since the formation of the MS, particularly articulated by developmental biologist Conrad Waddington and paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould [20]. The core argument posits that the MS became excessively "hardened" over time, focusing narrowly on natural selection while ignoring developmental processes, epigenetics, paleontology, and macroevolutionary phenomena.

Core Conceptual Challenges to the Neo-Darwinian Paradigm

Gene-Centrism and the Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework of neo-Darwinism has created barriers to theoretical expansion through its reliance on specific metaphors including 'gene', 'selfish', 'code', 'program', 'blueprint', 'book of life', 'replicator' and 'vehicle'. This form of representation confuses conceptual and empirical matters, requiring clear distinction. The definition of the central concept of 'gene' has evolved dramatically from describing a necessary cause (defined in terms of the inheritable phenotype itself) to an empirically testable hypothesis (in terms of causation by DNA sequences) [21].

Neo-Darwinism traditionally privileges 'genes' in causation, whereas multi-way networks of interactions suggest there can be no single privileged cause. An alternative conceptual framework proposes a more integrated systems view of evolution that avoids these problems and accommodates multi-causal networks [21]. This framework better accounts for phenomena where a common genetic toolkit guides the development of vastly different animal body plans, demonstrating that the genetic logic underlying the construction of extremely different animal forms—from sea anemones to humans—remains largely conserved [16].

The Role of Developmental Processes in Evolution

A primary criticism of the MS is its neglect of how developmental processes shape evolutionary trajectories. Evolution ultimately shapes phenotypes by tinkering with cellular characteristics. Understanding how diverse animal body plans evolved requires examining how specification networks control cell biological functions, not just genetic pathways [22]. Recent breakthroughs in applying molecular techniques to a broader range of research organisms beyond traditional models (e.g., mouse, fly, round worm, and zebrafish) enable better understanding of cellular regulation and coordination during morphogenesis across under-sampled branches of the animal tree of life [22].

Table 1: Key Challenges to the Modern Synthesis Framework

| Challenge Area | Core Argument | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Processes | MS ignored how development shapes evolutionary trajectories | Conserved genetic toolkit for body plan development [16] |

| Epigenetics | Non-genetic inheritance provides additional evolutionary mechanisms | Epigenetic inheritance systems beyond DNA sequence [21] |

| Macroevolution | MS focused on microevolution, neglecting paleontological patterns | Discordance between microevolutionary rates and macroevolutionary patterns [20] |

| Niche Construction | Organisms modify environments, creating new selection pressures | Ecosystem engineering and its evolutionary consequences [20] |

Quantitative Evidence from Evolutionary Design Principles

The field of quantitative evolutionary design uses evolutionary reasoning to understand why physiological and anatomical quantities have specific numerical values rather than others. This approach examines the magnitudes of biological reserve capacities—excesses of capacities over natural loads—through the lens of natural selection and ultimate causation [23].

Biological Safety Factors

Safety factors, defined as ratios of capacities to loads (SF = C/L), typically range from 1.2-10 for both engineered and biological components. These safety factors serve to minimize the performance failure overlap zone between the low tail of capacity distributions and the high tail of load distributions. The modest sizes of safety factors imply the existence of costs that penalize excess capacities, likely involving wasted energy or space for large components and opportunity costs for minor components [23].

Table 2: Safety Factors in Biological Structures [23]

| Structure | Organism | Safety Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Jawbone | Biting monkey | 7.0 |

| Wing bones | Flying goose | 6.0 |

| Leg bones | Running turkey | 6.0 |

| Leg bones | Galloping horse | 4.8 |

| Leg bones | Running elephant | 3.2 |

| Leg bones | Hopping kangaroo | 3.0 |

| Leg bones | Running ostrich | 2.5 |

| Dragline | Spider | 1.5 |

| Backbone | Human weightlifter | 1.35 |

Safety Factors in Physiological Systems

Physiological systems also demonstrate characteristic safety factors across different organs and species. These values reflect evolutionary compromises between the costs of maintaining excess capacity and the risks of performance failure. Studies of organ resection in humans reveal the functional limits of physiological safety factors, showing that unassisted survival becomes difficult after significant organ mass reduction [23].

Table 3: Safety Factors in Physiological Systems and Organs [23]

| Organ/System | Organism | Function | Safety Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreas | Human | Enzyme secretion | 10.0 |

| Kidneys | Human | Glomerular filtration | 4.0 |

| Mammary glands | Human | Milk secretion | 3.0 |

| Small intestine | Human | Absorption | 2.0 |

| Liver | Human | Metabolism | 2.0 |

| Lungs | Cow | Aerobic capacity | 2.0 |

| Lungs | Dog | Aerobic capacity | 1.25 |

Experimental Evidence from Evolutionary Developmental Biology

The Conserved Genetic Toolkit for Body Plan Development

Research on the starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis) provides compelling evidence for a deeply conserved genetic toolkit for body plan development. Despite lacking bones, brains, and a complete gut, sea anemones share a common ancestor with humans that lived over 600 million years ago. Studies of Nematostella development reveal genes that guide segment formation and direct segment polarity programs strikingly similar to those in bilaterian organisms, including humans [16].

Spatial transcriptomics has identified hundreds of segment-specific genes in Nematostella, including two crucial transcription factors that govern segment polarization under Hox gene control and are required for proper muscle placement. This represents the first evidence of a molecular basis for segment polarization in a pre-bilaterian animal, suggesting ancient evolutionary origins for these developmental mechanisms [16].

Diagram 1: Genetic Control of Nematostella Development

Experimental Protocols for Evolutionary Developmental Biology

Protocol 1: Spatial Transcriptomics in Non-Model Organisms

Objective: To identify segment-specific gene expression patterns in emerging model organisms like Nematostella vectensis.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Fix embryonic and larval stages at precise developmental timepoints in RNase-free conditions

- Tissue Sectioning: Cryosection tissue at 10-20μm thickness and mount on specialized slides for spatial genomics

- RNA Capture: Permeabilize tissues to allow RNA transfer to spatially barcoded capture probes

- Library Preparation: Reverse transcribe bound RNA, amplify cDNA, and prepare sequencing libraries with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs)

- Sequencing and Analysis: Perform high-throughput sequencing and map transcripts to spatial coordinates using reference genome

Key Considerations: This approach enables genome-wide expression profiling while retaining crucial spatial information, revealing how gene expression patterns guide morphogenesis. The technique is particularly valuable for organisms lacking genetic tools, allowing comparison of developmental pathways across deep evolutionary timescales [16].

Protocol 2: Quantitative Analysis of Safety Factors

Objective: To determine the safety factors of physiological systems and evolutionary components.

Methodology:

- Capacity Measurement (C): Determine maximal performance capacity (e.g., Vmax for enzymes, maximal load for structural elements)

- Load Measurement (L): Quantify natural operating loads under normal physiological conditions

- Safety Factor Calculation: Compute SF = C/L for each component

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: Evaluate evolutionary tradeoffs between excess capacity costs and failure risks

- Comparative Analysis: Compare safety factors across species, tissues, and physiological systems

Applications: This quantitative approach reveals evolutionary design principles and the selective pressures shaping physiological systems. Safety factors increase with coefficients of variation of load and capacity, with capacity deterioration over time, and with cost of failure, but decrease with costs of initial construction, maintenance, operation, and opportunity [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Evolutionary Developmental Biology

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Barcoding Arrays | Capture location-specific transcriptome data | Mapping gene expression patterns in Nematostella embryos [16] |

| Cross-Species Antibodies | Detect conserved proteins in non-model organisms | Immunostaining of Hox protein expression [22] |

| PhyloTranscriptomic Databases | Compare gene expression across species | Identifying deeply conserved developmental genes [16] |

| Genome Editing Tools (CRISPR) | Functional genetic testing in emerging models | Testing gene function in tunicate muscle development [22] |

| Live Imaging Systems | Visualize dynamic developmental processes | Tracking cell movements during morphogenesis [22] |

A Revised Conceptual Framework for Evolutionary Biology

The emerging framework for evolutionary biology acknowledges the complementary nature of previously competing perspectives. Rather than requiring a complete replacement of the MS, the evidence suggests a pluralistic expansion that accommodates developmental processes, epigenetic inheritance, and multi-level selection while preserving the mathematical rigor of population genetics.

This revised framework recognizes that:

- Genetic toolkit conservation enables diverse morphological evolution through regulatory network tinkering

- Quantitative evolutionary design principles apply across biological organization levels

- Developmental processes actively shape evolutionary possibilities through bias and constraint

- Multiple analytical perspectives (adaptationism, mutationism, neutralism, selectionism) provide complementary insights

Diagram 2: Integration of Evolutionary Frameworks

The integration of evolutionary developmental biology into the Modern Synthesis represents not its overthrow but its natural maturation as a scientific framework. Quantitative analyses of biological safety factors, comparative studies of genetic toolkits, and investigations of cellular morphogenesis mechanisms collectively reveal a more complex, pluralistic, and integrated evolutionary theory than traditionally conceived. While structuralism ("Evo Devo") and macroevolution await complete conceptual integration within mainstream evolutionary theory, the existing framework demonstrates remarkable capacity to accommodate new evidence through expansion rather than replacement. Future research should focus on mechanistic understanding of how cells build and shape body plans, enabling assessment of which cell types and morphogenetic processes are conserved versus convergently evolved versus truly evolutionarily novel.

The evolutionary origins of the planet's most prolific animal group, the Ecdysozoa, represents a central focus in understanding the Cambrian explosion. Ecdysozoans, the clade of molting invertebrates that encompasses arthropods, nematodes, and their relatives, comprise the largest proportion of animal biodiversity and disparity on Earth today [24] [25]. Despite their modern dominance, the early evolutionary history of this superphylum and the nature of its ancestral body plan have long remained contentious [24] [26]. For decades, the prevailing hypothesis, supported by molecular phylogenies and fossil evidence, reconstructed the last common ecdysozoan ancestor as a vermiform (worm-like) organism [24] [25]. However, recent fossil discoveries from Cambrian deposits are fundamentally challenging this paradigm, suggesting instead that the earliest ecdysozoans may have exhibited non-vermiform, sac-like body plans [24] [25] [27]. This whitepaper synthesizes current fossil evidence and experimental approaches that are reshaping our understanding of early ecdysozoan body plan evolution, providing a framework for researchers investigating the mechanisms underlying animal diversification.

Fossil Evidence of Early Ecdysozoan Body Plans

The Saccorhytida: A Basal, Non-Vermiform Clade

Recent paleontological investigations have identified an extinct group of microscopic ecdysozoans, the Saccorhytida, characterized by a sac-like body architecture distinct from traditional vermiform models. This group includes two formally described genera: Saccorhytus and the newly discovered Beretella.

Table 1: Characteristics of Saccorhytid Fossils

| Feature | Beretella spinosa | Saccorhytus coronarius |

|---|---|---|

| Geological Period | Basal Cambrian (Terreneuvian, Stage 2, ~529 Ma) [24] | Basal Cambrian (~535 Ma) [24] [25] |

| Body Size | Maximal length 3 mm [24] [25] | Microscopic [24] |

| Body Shape | Beret-like, ellipsoidal [24] | Sack-like [24] |

| Symmetry | Pronounced bilateral symmetry [24] [25] | Bilateral symmetry [24] |

| Key Features | Single opening (presumed oral); spiny ornamentation with sclerites; no anus [24] [25] | Single opening; conical sclerites; no anus [24] |

| Phylogenetic Position | Sister to all known Ecdysozoa [24] [25] | Sister to all known Ecdysozoa [24] [25] |

Beretella spinosa, discovered in the Yanjiahe Formation of South China, exhibits a distinctive beret-like profile with a convex dorsal side and flattened ventral surface [24]. Its body bears a complex ornamentation of five sets (S1-S5) of spiny sclerites with broad bases, directed toward the elevated posterior end [24] [25]. The sclerites show an internal cavity and ellipsoidal transverse section, preserved through secondary phosphatization [25]. The ventral surface, though poorly preserved, appears to feature a single opening, interpreted as a mouth, with no evidence of an anus [24]. This configuration suggests a digestive system with a single opening, a significant departure from the through-gut typical of many ecdysozoans.

Phylogenetic Context and Evolutionary Significance

Cladistic analyses place Beretella and Saccorhytus in a sister group relationship to all known ecdysozoans, forming the clade Saccorhytida [24] [25]. This phylogenetic positioning suggests that ancestral ecdysozoans may have been non-vermiform animals, with the vermiform body plan emerging later in the group's evolution [24]. The Saccorhytida likely represent an early divergent lineage that became extinct during the Cambrian, yet they provide crucial insight into the primitive morphology of molting animals [24].

The following diagram illustrates the proposed phylogenetic relationships and the evolution of key morphological traits within early Ecdysozoa:

Figure 1: Phylogenetic relationships of early ecdysozoans based on fossil evidence, showing the basal position of Saccorhytida relative to vermiform groups and panarthropods.

Additional Fossil Evidence

Beyond the Saccorhytida, other Cambrian fossils provide critical insights into ecdysozoan diversification. The recent description of Uncus dzaugisi from 555-million-year-old Ediacaran rocks in South Australia represents the oldest confirmed ecdysozoan, extending the group's fossil record into the Precambrian [26]. This worm-like organism features a cylindrical body, rigid cuticle, and evidence of motility, showing similarities with modern nematodes [26]. Additionally, kinorhynch fossils like Eokinorhynchus rarus from the early Cambrian (~535 Ma) demonstrate the presence of segmented, spiny body plans in the early ecdysozoan radiation [28].

Table 2: Temporal Distribution of Key Ecdysozoan Fossil Groups

| Fossil Group/Taxon | Geological Period | Age (Millions of Years) | Body Plan Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncus dzaugisi [26] | Late Ediacaran | ~555 | Cylindrical worm-like form, rigid cuticle, motility traces |

| Saccorhytus coronarius [24] | Basal Cambrian | ~535 | Sac-like, single opening, conical sclerites |

| Beretella spinosa [24] | Early Cambrian Stage 2 | ~529 | Beret-shaped, bilateral symmetry, spiny ornamentation |

| Eokinorhynchus rarus [28] | Early Cambrian | ~535 | Segmented body, distinct spines, kinorhynch-like |

| Priapulid worms [29] | Early-Middle Cambrian | ~521-505 | Vermiform, introvert, pharyngeal apparatus |

Experimental Approaches in Ecdysozoan Taphonomy and Phylogeny

Experimental Decay Protocols

Understanding the preservation biases affecting ecdysozoan fossils is crucial for accurate morphological interpretation. Experimental decay studies using modern priapulids (Priapulus caudatus) have established standardized protocols to investigate taphonomic processes [29]:

Organism Collection and Maintenance: Specimens are collected via benthic trawling from marine environments (e.g., Gullmar fjord, Sweden) and maintained in controlled conditions before experimentation [29].

Decay Experimental Setup: Two primary conditions are established: (1) artificial seawater without sediments, and (2) artificial seawater with fine-grained sediments. This allows assessment of sediment impact on preservation potential [29].

Temperature Control and Monitoring: Experiments are conducted at multiple temperature regimes (e.g., 7°C, room temperature) to simulate different environmental conditions and decay rates. Character states are monitored regularly to establish sequence of anatomical degradation [29].

Character State Documentation: Detailed observations focus on the relative decay susceptibility of internal non-cuticular anatomy versus recalcitrant cuticular structures. Specific attention is paid to the preservation potential of nervous tissues, gut systems, and other internal organs compared to cuticular features [29].

The experimental workflow for taphonomic studies can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for investigating ecdysozoan taphonomy through controlled decay studies.

Taphonomic Findings and Implications

Decay experiments reveal consistent bias toward rapid loss of internal non-cuticular anatomy compared with recalcitrant cuticular structures [29]. This pattern, also observed in onychophoran decay studies, appears to be general for early ecdysozoans [29]. Key findings include:

Cuticular Preservation Bias: Cuticular structures show significantly higher preservation potential than internal tissues, explaining the prevalence of cuticle-derived features in Cambrian fossil assemblages [29].

Internal Tissue Lability: Nervous tissues, gut systems, and other internal organs decay rapidly except under conditions conducive to authigenic mineralization, challenging interpretations of such structures in organically preserved fossils [29].

Sediment Impact: The presence of fine-grained sediments can enhance preservation fidelity but does not fundamentally alter the sequence of character loss [29].

These taphonomic constraints necessitate careful interpretation of fossil anatomies, particularly for claims of preserved neural or vascular tissues in Cambrian ecdysozoans [29].

Phylogenetic Analysis Framework

To mitigate taphonomic biases in evolutionary interpretations, researchers have developed explicit protocols for phylogenetic analysis of fossil ecdysozoans:

Character Coding: Implementation of taphonomically informed character coding distinguishes between truly absent features and those potentially lost to preservation biases [29]. This involves separate coding for characters absent due to taphonomic processes versus phylogenetic absence.

Decay-Based Character Weighting: Characters are weighted based on empirical data about their relative decay resistance, reducing the influence of systematic taphonomic biases on phylogenetic inference [29].

Multiple Analysis Conditions: Phylogenetic analyses are conducted under multiple conditions, including traditional and taphonomically informed character coding, to test the stability of topological relationships [29].

Application of these methods to scalidophoran taxa reveals high sensitivity to taphonomic character coding, while panarthropodan relationships remain relatively stable [29]. This underscores the importance of incorporating taphonomic data in phylogenetic analyses of early ecdysozoans.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Ecdysozoan Fossil Research

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fine-Grained Sediments | Enhanced preservation of fine anatomical details in fossilization experiments [29] [26] | Experimental taphonomy |

| Artificial Seawater Formulations | Standardized medium for decay experiments controlling for environmental variables [29] | Experimental taphonomy |

| Phosphatization Reagents | Simulation of secondary phosphatization processes common in Cambrian microfossils [24] [30] | Fossil preservation studies |

| 3D Laser Scanning Technology | High-resolution digital preservation of fossil specimens without physical removal [26] | Field documentation and analysis |

| Clay Powder Matrix | Experimental investigation of sediment-organism interactions in preservation [29] | Taphonomic experiments |

| Synchrotron Radiation Technology | Non-destructive internal imaging of rare fossil specimens [30] | Fossil embryology and morphology |

Discussion: Implications for Body Plan Evolution

The discovery of saccorhytids as potential stem-group ecdysozoans challenges traditional models of early animal evolution and necessitates reconsideration of body plan ground patterns. Several key implications emerge:

Reconsidering the Ancestral Ecdysozoan

The phylogenetic position of Saccorhytida suggests three possible evolutionary scenarios for the ancestral ecdysozoan body plan:

Non-Vermiform Ancestor: The last common ecdysozoan ancestor may have possessed a small, sac-like body with a single opening, with the vermiform body plan arising later in ecdysozoan evolution [24] [25].

Vermiform Ancestor with Secondary Simplification: Saccorhytids may represent a secondarily simplified lineage that derived from vermiform ancestors, though this would require extensive anatomical modifications including loss of vermiform organization, introvert, and through-gut [31].

Meiobenthic Ancestor: An alternative model suggests the ancestral ecdysozoan might have been small and meiobenthic, with multiple body plans emerging early in the group's radiation [31].

Current evidence does not definitively resolve these possibilities, highlighting the need for additional fossil discoveries and refined phylogenetic analyses.

Developmental and Evolutionary Plasticity

The coexistence of three distinct ecdysozoan body plans (sac-type, vermiform, and limb-bearing) during the Cambrian indicates unexpected plasticity in early animal evolution [27]. This diversity suggests that early ecdysozoans explored a broader range of morphological possibilities than previously recognized, with most of this disparity subsequently lost to extinction.

Recent studies of fossil embryos from the basal Cambrian further reveal diverse developmental strategies among early ecdysozoans [30]. Specimens assigned to the new genus Saccus show cuticle-bearing, non-ciliated, bag-shaped bodies without introverts or paired limbs, potentially representing indirect developers that hatched as lecithotrophic larvae [30]. This developmental diversity parallels the morphological disparity observed in adult forms.

Integration with Molecular Phylogenetics

Molecular clock analyses have consistently suggested an Ediacaran origin for ecdysozoans, predating their appearance in the fossil record [28] [26]. The discovery of Uncus dzaugisi in Ediacaran deposits helps bridge this temporal gap, confirming the presence of ecdysozoans before the Cambrian explosion [26]. However, discrepancies remain between molecular predictions and fossil evidence, particularly regarding the timing of cladogenetic events and the sequence of morphological innovations.

The fossil evidence from Cambrian deposits is fundamentally reshaping our understanding of early ecdysozoan evolution. The discovery of non-vermiform saccorhytids at the base of the ecdysozoan tree challenges long-held assumptions about the ancestral body plan of this immensely successful animal group. Integrated approaches combining detailed fossil description, experimental taphonomy, and rigorous phylogenetic analysis provide a powerful framework for reconstructing early animal evolution. As research continues, with particular focus on poorly explored Ediacaran-Cambrian transitions and the application of novel imaging technologies, our understanding of ecdysozoan origins will undoubtedly continue to evolve, offering broader insights into the mechanisms driving animal body plan evolution during this pivotal period in life's history.

The body plan concept, or Bauplan, forms the foundational backbone of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo). Defined as a suite of characters shared by a group of phylogenetically related animals at some point during their development, body plans represent both historical artifacts of shared evolutionary history and contemporary subjects of ongoing evolutionary processes [32]. The study of body plan evolution has progressed from Aristotle's "unity of plan" and Owen's idealistic "archetype" to our modern materialistic understanding grounded in Darwinian common descent [32]. Despite this rich history, the relative contributions of internal selection and developmental constraints in stabilizing and directing body plan evolution over deep geological timescales remain inadequately characterized within the broader thesis of animal evolution research.

This technical review examines the underappreciated roles of internal selection and developmental constraints as pivotal forces in body plan evolution. We integrate quantitative evolutionary design principles with modern genomic analyses to provide researchers with both theoretical frameworks and practical methodologies for investigating these phenomena. The evolutionary stability of fundamental anatomical organizations over hundreds of millions of years, despite continuous genetic drift, presents a paradox that can only be resolved by understanding the delicate balance between external stabilizing selection, internal developmental constraints, and their collective impact on organismal robustness [33]. Through this synthesis, we aim to equip researchers with the conceptual tools and experimental approaches necessary to advance this fundamental aspect of evolutionary biology.

Theoretical Foundations: From Quantitative Evolutionary Design to Developmental Constraints

The Quantitative Evolutionary Design Paradigm

The field of quantitative evolutionary design uses evolutionary reasoning in terms of natural selection and ultimate causation to understand why physiological and anatomical quantities possess specific numerical values rather than higher or lower alternatives [23]. This approach provides crucial insights into how natural selection optimizes biological systems, bridging the gap between physiology and evolutionary biology.

Central to this framework is the concept of safety factors - defined as the ratio of biological capacity to natural load (SF = C/L) [23]. Safety factors typically range from 1.2 to 10 for both engineered and biological components, serving to minimize performance failure by reducing overlap between capacity and load distributions. The modest sizes of biological safety factors imply the existence of costs that penalize excess capacities, likely involving wasted energy, space, or opportunity costs [23]. The table below illustrates representative biological safety factors across different organizational levels:

Table 1: Biological Safety Factors Across Organizational Levels

| Structure/System | Species | Safety Factor | Functional Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jawbone | Biting monkey | 7 | Structural support during mastication |

| Leg bones | Running elephant | 3.2 | Weight support during locomotion |

| Leg bones | Running ostrich | 2.5 | High-speed bipedal locomotion |

| Dragline | Spider | 1.5 | Web construction |

| Backbone | Human weightlifter | 1.35 | Extreme axial loading |

| Intestinal glucose transporter | Mouse | 2.8 | Nutrient absorption |

| Renal function (paired kidneys) | Human | 4 | Metabolic waste filtration |

| Hepatic metabolic capacity | Human | 2 | Xenobiotic detoxification |

The closely matched safety factors of series components operating in physiological pathways (e.g., intestinal hydrolyses and transporters) highlight the precision of evolutionary optimization despite these components being coded by separate genes [23]. This optimization reflects the balance between the costs of excess capacity and the risks of performance failure - a fundamental principle of quantitative evolutionary design.

Developmental Constraints and Evolutionary Channeling

Developmental constraints represent biases on the production of phenotypic variation imposed by the structure, character, composition, or dynamics of developmental systems [32]. These constraints channel evolutionary outcomes along certain trajectories while limiting others, creating phylogenetic patterns of body plan conservation. The exceptional morphological stability of ascidian embryos over 500 million years, despite extreme genome sequence divergence, exemplifies this phenomenon [33].

Several categories of developmental constraints operate during body plan formation:

- Structural constraints: Physical and architectural limitations imposed by existing anatomical organizations

- Phylogenetic constraints: Historical limitations derived from ancestral developmental programs

- Generative constraints: Limitations in the production of phenotypic variation due to developmental system properties

- Selective constraints: Biases in the preservation of phenotypic variation during evolution

The integration of these constraints creates evolutionary channelling wherein certain morphological transformations become statistically improbable despite potential adaptive value. This explains the remarkable conservation of fundamental body plans across deep evolutionary timescales, even as superficial characteristics diversify extensively.

Quantitative Framework: Modeling the Evolution of Complex Traits

Quantitative Traits and Their Evolutionary Dynamics

Body plan characteristics typically manifest as quantitative traits - continuously varying phenotypes dependent on the cumulative action of many genes and environmental influences [34]. Unlike qualitative traits with discrete categorical expressions, quantitative traits exhibit normal distributions within populations, with most individuals showing intermediate phenotypes and extremes being rare [34].

The evolution of quantitative traits is governed by their heritability - the proportion of phenotypic variation attributable to genetic variation. Specifically, narrow-sense heritability (h² = VA/VP) quantifies the additive genetic component of phenotypic variance that responds predictably to selection [34]. This parameter is crucial for predicting evolutionary responses in body plan characteristics:

Table 2: Parameters for Quantitative Trait Evolution

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic variance | V_P | Total observed variation in a trait | Sets upper limit on heritable variation |

| Additive genetic variance | V_A | Proportion of variance from additive gene effects | Determines response to selection |

| Dominance variance | V_D | Proportion from allelic interactions | Non-responsive to selection |

| Environmental variance | V_E | Proportion from environmental influences | Reduces heritability |

| Narrow-sense heritability | h² | VA/VP | Predicts response to selection |

| Selection differential | S | Mean difference between selected and population | Direct measure of selection strength |

| Selection gradient | β | Regression of relative fitness on trait value | Measures direct selection on a trait |

The evolutionary response of a quantitative trait (R) is predicted by the breeder's equation: R = h²S, where S represents the selection differential [34]. This framework enables researchers to quantify both the strength of selection on body plan elements and their predicted evolutionary trajectories.

Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Modeling of Expression Evolution

Gene expression evolution across mammals follows an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process rather than neutral drift, indicating stabilizing selection on transcriptional programs [35]. The OU model describes changes in expression (dXₜ) across time (dt) by:

dXₜ = σdBₜ + α(θ - Xₜ)dt

where dBₜ denotes Brownian motion (drift), σ represents the drift rate, α quantifies the strength of selective pressure, and θ signifies the optimal expression level [35]. This model elegantly quantifies the contributions of both stochastic drift and selective pressures, with expression levels reaching a stable normal distribution (mean θ, variance σ²/2α) over evolutionary time.

Applications of the OU model to mammalian RNA-seq data across seven tissues and 17 species reveal that most genes evolve under stabilizing selection within the mammalian lineage [35]. This approach enables researchers to:

- Quantify the extent of stabilizing selection on a gene's expression across different tissues

- Parameterize the distribution of each gene's optimal expression level