Tracing Cell Lineages in Evolution: From Fate Maps to Clinical Breakthroughs

This article explores the transformative role of cell lineage tracing in understanding evolutionary and developmental biology.

Tracing Cell Lineages in Evolution: From Fate Maps to Clinical Breakthroughs

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of cell lineage tracing in understanding evolutionary and developmental biology. It details the journey from foundational techniques like direct observation and dye labeling to cutting-edge single-cell barcoding and computational methods. The content covers the principles, applications, and limitations of key technologies, including recombinase systems, CRISPR-based barcoding, and integrative imaging-sequencing approaches. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a framework for troubleshooting experimental design, optimizing lineage tracking accuracy, and validating findings through comparative analysis. The article synthesizes how these advanced methods are unraveling cell fate decisions in development, regeneration, and disease, offering new avenues for regenerative medicine and therapeutic discovery.

The Evolutionary Roots of Cell Lineage Tracing: From Whitman's Leeches to Single-Cell Resolution

Fate mapping stands as a foundational methodology in developmental biology, enabling researchers to study the embryonic origin of various adult tissues and structures by mapping the developmental "fate" of each cell or group of cells onto the embryo [1]. The earliest fate maps, originating in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were constructed through the direct observation of living embryos, laying the groundwork for our understanding of cell lineage and embryonic patterning. These pioneering studies established a critical framework for contemporary evolutionary developmental biology ("evo-devo") by providing the first empirical evidence of how ancestral cell lineages are conserved or diverged across species. The fundamental principle—tracking progenitor cells to their terminal fates—connects the phylogenetic history of organisms to their ontogenetic development, allowing modern researchers to trace cell lineages across an evolutionary context.

Pioneers and Foundational Experiments

The creation of the first fate maps was made possible by the meticulous work of early embryologists who studied optically clear embryos of marine invertebrates.

Edwin Conklin and the Ascidian Egg

In 1905, Edwin Conklin conducted the first definitive cell lineage study by visually tracking the development of the ascidian (Styela partita, a sea squirt) egg [1]. His methodology relied on:

- Natural Pigment Granules: He utilized the naturally pigmented cytoplasm in the ascidian egg as an intrinsic marker.

- Direct Microscopic Observation: He painstakingly observed and documented the segregation of these pigment granules into specific daughter cells during each cleavage division.

- Fate Documentation: By tracing these pigmented cells through development, he could determine which tissues and organs they ultimately formed, creating a detailed map of cell fate.

This work was seminal as it provided the first clear evidence that the developmental potential of embryonic cells becomes restricted in a predictable manner, and that specific blastomeres give rise to specific larval structures. Conklin's direct observation approach established the core concept that a cell's ancestry, or lineage, is intrinsically linked to its final fate.

Walter Vogt and the Vital Staining Revolution

While Conklin used endogenous markers, the next major advancement came from introducing external markers. In 1929, Walter Vogt invented a technique that significantly enhanced the precision of fate mapping: local vital staining [1]. His protocol represented a major methodological leap:

- Preparation of Markers: Vogt prepared chips of agar impregnated with vital dyes, such as Nile blue or neutral red, which could stain cells without killing them.

- Localized Application: He applied these dyed agar chips to specific, precisely chosen regions on the surface of amphibian embryos.

- Lineage Tracing: As the embryo developed and underwent complex morphogenetic movements, particularly gastrulation, he tracked the movement and displacement of the stained cell populations over time.

Vogt's technique allowed him to create the first accurate fate maps for amphibian gastrulation, providing unprecedented insights into the dynamic rearrangements of cell layers that had previously been inferred from static sections. This approach introduced an innovative, dynamic dimension to morphogenesis research, moving beyond simple lineage tracing to mapping cell movements.

Table 1: Foundational Fate Mapping Experiments by Direct Observation

| Researcher | Year | Model Organism | Core Methodology | Key Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edwin Conklin | 1905 | Ascidian (Styela partita) [1] | Observation of natural pigment granules during cleavage. | Demonstrated a predictable, restricted cell lineage where specific blastomeres give rise to specific structures. |

| Walter Vogt | 1929 | Amphibians (Urodeles and Anurans) [1] | Local application of vital dyes (e.g., on agar chips) to track cell populations. | Mapped the dynamic movements of cell sheets during gastrulation, creating the first modern fate maps. |

Quantitative Framework and Modern Interpretations

While early studies were qualitative, modern research has built upon them to develop quantitative frameworks. Contemporary quantitative fate mapping is a computational approach that reconstructs the hierarchy, commitment times, population sizes, and commitment biases of intermediate progenitor states based on the time-scaled phylogeny of their descendants [2]. This modern perspective allows scientists to analyze progenitor fate and dynamics long after embryonic development in any organism, directly leveraging the phylogenetic relationships recorded in cell lineages. Algorithms like Phylotime infer time-scaled phylogenies from lineage barcodes, and ICE-FASE uses these phylogenies to reconstruct quantitative fate maps, allowing researchers to extract dynamic progenitor state information from static lineage data [2] [3]. This provides a powerful link between the historical foundation of direct observation and current capabilities in evolutionary cell lineage analysis.

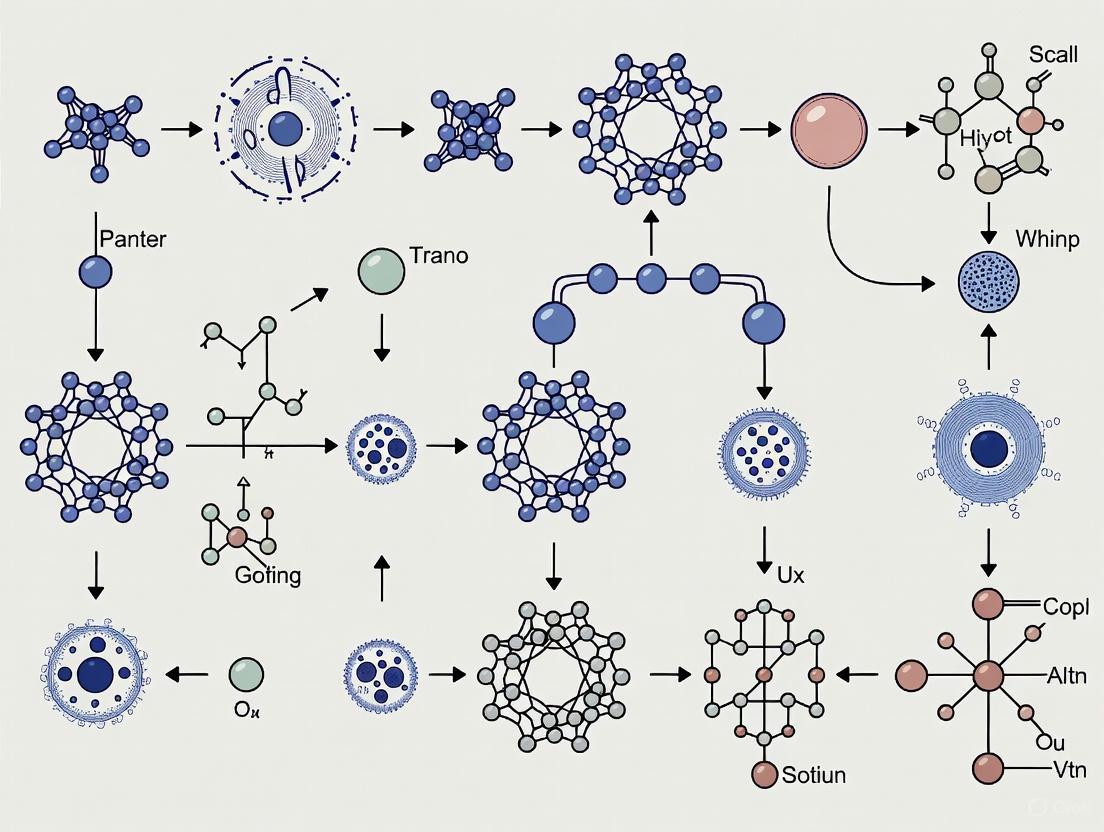

Visualizing Foundational Fate Mapping Techniques

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the core methodologies established by the pioneers of fate mapping.

Direct Observation of Natural Markers

Vital Staining with Artificial Markers

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials central to the historical and foundational fate mapping techniques described.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Classical Fate Mapping

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Pigment Granules | Endogenous cytoplasmic markers for visual tracking of cell divisions without experimental manipulation. | Used by Conklin (1905) in ascidian eggs to establish the first cell lineages [1]. |

| Agar Chips | Solid, biocompatible substrate for holding and locally applying dyes to delicate embryonic tissues. | Used by Vogt (1929) to prevent dye diffusion and enable precise regional staining of amphibian embryos [1]. |

| Vital Dyes (Nile Blue, Neutral Red) | Non-toxic stains that bind to cellular components, allowing long-term tracking of live cell populations. | The core labeling agent in Vogt's vital staining technique for fate mapping gastrulation [1]. |

| Marine Invertebrate Embryos | Transparent, rapidly developing model systems ideal for direct microscopic observation of cell divisions. | Ascidian (Styela partita) and tunicate (Holocynthia roretzi) embryos were used by Conklin and others [1] [4]. |

| Amphibian Embryos | Large, robust embryos suitable for microsurgery and manipulation, model for complex morphogenesis. | Used by Vogt and subsequent researchers to study gastrulation movements in vertebrates [1]. |

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol: Classical Vital Staining Fate Map

This protocol is adapted from the historic work of Walter Vogt (1929) for use in a modern developmental biology laboratory context [1].

Objective: To map the fates of specific cell populations on the surface of an amphibian embryo during gastrulation.

Materials:

- Early gastrula-stage amphibian embryos (e.g., Xenopus laevis)

- Fine agarose

- Vital dye: 1% Nile Blue sulfate or Neutral Red solution in distilled water

- Standard microscope slides

- Fine forceps and hair loops

- Dissecting microscope with a cool light source

- Petri dishes with 3% agarose coated with 1x MBS or MMR

Procedure:

- Preparation of Dyed Agar Chips:

- Melt 3% fine agarose in distilled water and allow it to cool to ~50°C.

- Mix with an equal volume of 1% Nile Blue sulfate solution.

- Pipette a small amount onto a microscope slide and allow it to solidify.

- Using a razor blade, cut the dyed agar into small chips (~100-200 µm square).

Embryo Preparation and Staining:

- De-jelly embryos manually if necessary.

- Transfer an embryo to an agarose-coated dish filled with buffer to stabilize it.

- Using fine forceps, carefully place a single dyed agar chip on the desired region of the embryo's surface (e.g., prospective neural plate, epidermis).

- Allow the dye to transfer for 10-30 seconds before gently removing the chip.

Tracking and Analysis:

- Maintain the stained embryo in a temperature-controlled incubator.

- At regular intervals (e.g., every 2-4 hours), observe the embryo under a dissecting microscope.

- Document the position and shape of the stained cell cluster using camera lucida drawings or time-lapse photography.

- Continue observations until the desired developmental stage is reached, noting the final tissue contributions of the stained cells.

- Repeat the experiment on multiple embryos (n > 10) staining the same region to build a probabilistic fate map.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Poor dye transfer: Ensure the agar chip makes firm contact with the embryo's surface. Slightly drying the embryo surface before application can improve transfer.

- Toxicity/Embryo death: Test dye concentrations and exposure times on non-essential embryos first. Neutral red is often less toxic than Nile blue.

- Diffuse staining: Minimize the time the chip is in the buffer before application to prevent dye leakage.

Application in Evolutionary Context

The direct observation techniques established by Conklin and Vogt remain relevant in evolutionary developmental biology. Modern simulation laboratories allow students and researchers to apply these principles computationally. For instance, the FatemapApp enables the quantitative analysis of fate maps for Xenopus laevis (frog), Danio rerio (zebrafish), and Holocynthia roretzi (tunicate) [4]. Cross-species comparative analysis of these simulated fate maps allows for the inference of tissue organization across chordate and vertebrate embryos that may be evolutionarily conserved, directly building upon the foundational work of the early fate mappers [4]. This bridges the historical method of direct observation with contemporary quantitative analysis, facilitating insights into the evolution of developmental programs.

Cell fate determination is a fundamental process in multicellular development, where cells display remarkable plasticity, allowing them to revert to prior states or adopt alternative differentiation pathways in response to specific stimuli. Investigating this plasticity is essential for understanding organ development, tissue homeostasis, and disease pathogenesis, providing critical insights for regenerative medicine strategies [5]. Lineage tracing technologies have fundamentally revolutionized our understanding of cell fate dynamics by enabling the identification and tracking of cells and their progeny in vivo [5]. The evolution of these technologies—from direct observation and dye-based labeling to sophisticated recombinase-mediated genetic techniques—has progressively enhanced our ability to interrogate cellular heterogeneity with increasing precision. This technical progression frames the central challenge in modern evolutionary and developmental biology: how to move from manipulating cell populations defined by single genes to targeting specific cellular subpopulations defined by unique molecular signatures [6] [7]. This article details the application of advanced recombinase systems to overcome this challenge, providing detailed protocols and resources for implementing these powerful genetic labeling technologies in lineage tracing research.

Intersectional Genetics: A Framework for Enhanced Specificity

The Principle of Intersectional Genetics

Intersectional genetics represents a paradigm shift in genetic targeting, moving beyond the limitations of single-recombinase systems. This methodology facilitates spatial and temporal genome manipulation in a more precisely defined subset of cells by combining multiple orthogonal recombinase systems (e.g., Cre, CreERT, Tet, Flp, Dre) in a single model organism [6]. Each recombinase recognizes its own unique target sites (Cre-lox, CreERT-lox, Tet-tTA, Flp-Frt, Dre-Rox), allowing for expression of reporters or functional effectors only in cell populations defined by the co-expression of distinct genetic markers rather than a single gene [6]. This approach directly addresses the critical issue of cellular heterogeneity, where not all cells expressing a shared gene have identical biological roles [6].

For example, while a CckCre::Ai40D mouse enables visualization of all Cck-expressing cells, and a Slc32a1Cre::Ai40D mouse targets all GABAergic neurons, an intersectional approach using a CckCre::Slc32a1FlpO::Ai80D mouse enables selective manipulation of only the specific subpopulation of GABAergic neurons that co-express Cck [6]. This precision is vital for unraveling functional heterogeneity within seemingly uniform cell populations.

Core Components and Implementation Strategies

An intersectional genetics system requires three minimal components [6]:

- A recombinase driver line of interest.

- A second, orthogonal recombinase driver line of interest.

- A "double-stop" reporter line that is activated only after recombination by both driver lines.

Implementation can be achieved through two primary methods:

- Traditional Breeding: Although more time-consuming, this approach offers the advantage of consistent, reproducible expression over successive generations [6].

- Viral Delivery: This provides a more expedited means of introducing multiple recombinase systems and may be particularly advantageous when time is a critical factor. However, careful consideration must be given to factors such as variability in transduction efficiency [6].

Quantitative Characterization of Recombinase-Based Digitizers

The performance of genetic circuits, including those used for lineage tracing, can be quantitatively evaluated using standardized metrics from synthetic biology. These metrics are crucial for comparing systems and predicting their behavior in new contexts.

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Recombinase-Based Digitizer Circuits [8]

| Metric | Definition | Application in Circuit Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Fold Change (FC) | The mean ON-state expression level divided by the mean OFF-state expression level. | Measures signal amplitude but does not describe population variance. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Captures both signal amplitude and variance within cell populations. | Quantifies the distinguishability between ON and OFF states; higher SNR indicates better signal quality. |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. | Another distribution-based metric that captures the distinguishability between two phenotypic states. |

Applying these metrics reveals key design considerations. For instance, a basic, inducible recombinase digitizer (e.g., Tet-ON Flp) may demonstrate significant leaky expression in the OFF-state, undermining its digital performance [8]. Engineering solutions to control this leak include:

- Feedforward-shRNA Topology: Incorporates a shRNA element controlled by a coherent feedforward loop to stifle leaky recombinase expression. This design can increase fold change (e.g., 15-fold) compared to a no-shRNA design (8.5-fold) by dramatically decreasing basal OFF-state expression [8].

- Constant-shRNA Topology: Produces shRNA at a steady level to establish a transcriptional threshold. This effectively controls leak but can lead to over-repression, resulting in low fold change and a failure to achieve robust population-level activation [8].

Experimental Protocols for Intersectional Lineage Tracing

Protocol 1: Implementing Intersectional Genetics via Breeding

This protocol outlines the steps for generating a mouse model for intersectional lineage tracing using traditional breeding [6].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Driver Lines: Genetically engineered mouse strains expressing a recombinase (e.g., Cre, Flp, Dre) under a cell-type-specific promoter.

- Reporter Line: A mouse strain containing a genetically embedded reporter (e.g.,

Ai65D,Ai80D) that requires the action of two recombinases for activation. The reporter typically has a ubiquitous promoter driving expression of a fluorescent protein or effector gene, preceded by two transcription stop cassettes, each flanked by recognition sites for a different recombinase [6] [7]. - Genotyping Kits: Reagents for PCR-based determination of mouse genotypes.

Methodology:

- Cross 1: Mate the first recombinase driver line (e.g.,

Cck-Cre) with the dual-recombinase-responsive reporter line (e.g.,Ai80D). - Cross 2: Mate the second, orthogonal recombinase driver line (e.g.,

Slc32a1-FlpO) with the offspring from Cross 1 that are heterozygous for both the first recombinase and the reporter. - Experimental Animal Generation: Select offspring from Cross 2 that are heterozygous for both driver genes and the reporter allele. These animals will have the genotype

Cck-Cre::Slc32a1-FlpO::Ai80D. - Validation: Validate the model using immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry to confirm that reporter expression is restricted to cells expressing both original genetic markers.

Protocol 2: Viral Delivery for Intersectional Labeling

This protocol is suitable for rapid interrogation of cellular subpopulations, especially in species or contexts where breeding is impractical [6].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Recombinant Adeno-Associated Viruses (rAAVs): Engineered to express orthogonal recombinases (e.g., Cre and Flp). These should be serotyped for high tropism to the target cell population.

- Stereotaxic Instrumentation: Equipment for precise intracranial injection of viral vectors into specific brain regions of adult animals.

- Inducing Agents: If using inducible systems (e.g., CreERT2), tamoxifen or its analogs are required for temporal control of recombinase activation.

Methodology:

- Virus Preparation: Produce high-titer, purified rAAVs encoding Cre and Flp recombinases. A reporter mouse line (e.g.,

Ai65D) that requires both Cre and Flp for tdTomato expression is used as the host. - Stereotaxic Surgery: Anesthetize the adult reporter mouse and secure it in a stereotaxic frame. Use coordinates to target the brain region of interest.

- Co-injection: Inject a mixture of the Cre- and Flp-expressing rAAVs into the target region.

- Incubation: Allow 2-4 weeks for robust viral transduction, recombinase action, and reporter protein expression.

- Analysis: Process tissue for imaging or flow cytometry. Reporter expression will be confined to cells that were co-transduced with both viruses and thus expressed both Cre and Flp.

Figure 1: Breeding strategy for generating an intersectional genetics mouse model. The final experimental animal expresses the reporter only in cells where both driver genes are active.

Expanded Reagent Toolkit for Researchers

The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) and other repositories host numerous driver and reporter models specifically suitable for intersectional genetics. The table below summarizes key reagents.

Table 2: Selected Intersectional Genetics Reporter Models [6]

| JAX Strain # | Common Name | Recombinase Dependence | Effector/Reporter | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ai162D | TIGRE::TRE2 + CAG | Cre- and Tet-dependent | GCaMP6s + tTA2s | Calcium indicator |

| Ai65D | R26::CAG | Cre- and Flp-dependent | tdTomato | General cell labeling (xFP) |

| Ai80D | R26::CAG | Cre- and Flp-dependent | CatCh (ChR2*L132C) / EYFP | Optogenetics and fluorescence |

| Ai139D | TIGRE::TRE2 + CAG | Cre- and Tet-dependent | EGFP + tdT + tTA2 | Differential fluorescent protein expression |

| RC::FPDi | R26::CAG | Flp-inducible, then Cre- & CNO-inducible | Gi-DREADD (hM4Di) :: mCherry | Chemogenetic neuronal silencing |

Application in Dual Recombinase Fate Mapping

Dual recombinase systems have been powerfully applied to answer complex questions in development and regeneration. For example, a Cre-loxP/Dre-rox dual system was recently used to determine the origin of regenerative cells in remodelled bone, successfully distinguishing otherwise homogenous periosteal tissue into distinct layers and evaluating their respective contributions to fracture healing [7]. This demonstrates the power of intersectional genetics for deconstructing complex tissues and fate-mapping specific cellular subpopulations within an evolutionary context of tissue repair and regeneration.

Figure 2: Viral workflow for intersectional fate mapping. Reporter activation requires co-expression of two recombinases, precisely defining a subpopulation for lineage tracing.

Defining Cell Fate and Plasticity in Development and Evolution

Core Concepts and Mechanisms of Cell Fate

Cell fate determination is the process whereby a cell becomes committed to a specific lineage or differentiated state during development. This commitment is governed by a complex interplay of intrinsic factors, such as transcription factors and inherited cytoplasmic determinants, and extrinsic factors, including signaling molecules from neighboring cells and mechanical cues from the microenvironment [9] [10] [11]. The final outcome is the acquisition of a specific cellular identity, characterized by a stable pattern of gene expression that defines the cell's function [12] [11].

Modes of Cell Fate Specification

There are three primary mechanisms by which a cell's fate is specified [9]:

- Autonomous Specification: A cell-intrinsic process where fate is determined by asymmetrically localized maternal molecules (proteins, mRNAs) partitioned into the daughter cell during division. This leads to mosaic development, where the isolated cell will still form the structure it was pre-programmed to create.

- Conditional Specification: A cell-extrinsic process where fate is determined by interactions with neighboring cells or concentration gradients of morphogens. This mechanism demonstrates cellular plasticity, as a cell's fate can be altered by signals from its environment. If a tissue is ablated, neighboring cells can often regenerate the lost structure.

- Syncytial Specification: A hybrid mechanism observed in insects, where morphogen gradients operate within a syncytium (a cell with multiple nuclei) before cellularization, influencing nuclei in a concentration-dependent manner.

The Role of Signaling Pathways and Gene Regulatory Networks

Critical cell fate decisions are coordinated by conserved signaling pathways and intricate gene regulatory networks (GRNs). Key pathways include Notch, Wnt, Hedgehog, and BMP [9] [10]. These pathways ultimately influence the activity of transcription factors (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, Hox genes) that form auto-regulatory loops to establish and maintain cell identity [13] [11]. The activity of these GRNs is further fine-tuned by epigenetic mechanisms—such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling—which regulate gene accessibility without altering the DNA sequence, providing a layer of cellular memory [9] [11].

Table: Key Signaling Pathways in Cell Fate Determination

| Pathway | Key Components | Primary Role in Cell Fate | Associated Tissues/Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Notch | Notch receptor, Delta/Jagged ligands | Lateral inhibition; binary fate decisions | Neurogenesis, Somitogenesis |

| Wnt | Wnt ligands, Frizzled receptors, β-catenin | Cell proliferation, polarity, and fate specification | Axis formation, Stem cell maintenance |

| Hedgehog | Hedgehog ligand, Patched/Smoothened receptors | Patterning and progenitor cell fate | Neural tube, Limb bud patterning |

| BMP/TGF-β | BMP/TGF-β ligands, SMAD transcription factors | Dorsoventral patterning; differentiation | Bone/Cartilage formation, Epidermal specification |

Quantitative Frameworks and Cell Fate Dynamics

Understanding cell fate requires moving beyond qualitative descriptions to quantitative models that can predict cellular behaviors. The cell can be viewed as a dissipative dynamical system, where its molecular state evolves over time according to a set of regulatory rules [12].

The State-Space and Attractor Theory

The complete molecular profile of a cell (e.g., gene expression, protein abundance) can be represented as a point in a high-dimensional state-space [12]. Within this space, specific, stable patterns of expression that correspond to functional cell fates are conceptualized as attractors—isolated regions toward which the system evolves from a range of initial conditions (the basin of attraction) [12]. This framework explains why many different molecular states can map to the same cellular function (robustness), while also accounting for the existence of "fault lines" that separate discrete fates.

Quantifying Plasticity and Fate Transitions

Cell fate plasticity can be quantified by probing the stability of these attractor states. Waddington's landscape is a classic metaphor for this, where cell fates are represented as valleys. The following table summarizes quantitative measures used to analyze fate dynamics [12] [14].

Table: Quantitative Measures for Analyzing Cell Fate Dynamics

| Measure | Description | Application Example | Experimental Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Velocity | Computes time derivatives of gene expression from scRNA-seq data to infer past/future states [15]. | Inferring developmental trajectories in murine skin [15]. | Pseudotime analysis of differentiation. |

| Attractor Stability | Mathematical robustness of a stable state in a GRN model to perturbations. | Modeling pluripotency and differentiation networks. | Measured by fate resilience after transient signal inhibition. |

| Lineage Tracing Clonal Statistics | Quantitative analysis of clone sizes, composition, and complexity from lineage tracing data [14]. | Determining multipotency vs. unipotency in mammary gland and prostate development [14]. | Direct measurement of stem cell potential in vivo. |

| Plasticity Index | The range of possible fates a cell can adopt upon experimental perturbation. | Assessing the gain/loss of plasticity during evolution and development [16]. | Embryonic blastomere isolation and transplantation assays. |

Experimental Protocols for Lineage Tracing and Fate Mapping

To move from theory to mechanism, rigorous experimental protocols are required to track cell fate in living organisms. Lineage tracing is the gold-standard method for mapping the fate of individual cells and their progeny within their natural context over time [15] [14].

Protocol: Saturation Lineage Tracing for Assessing Stem Cell Potency

This protocol is designed to definitively determine whether a population of stem cells is unipotent or multipotent by labeling all cells within a lineage [14].

1. Principle: By genetically labeling 100% of a candidate stem cell population (saturation), one can trace all descendant lineages without ambiguity, avoiding false conclusions from mosaic labeling.

2. Materials:

- Inducible CreER Mouse Model: Genetically engineered mouse with Cre recombinase fused to a mutant estrogen receptor (ER) under the control of a cell-type-specific promoter (e.g., K5-CreER for basal cells, K8-CreER for luminal cells) [14].

- Reporter Mouse Strain: Rosa26-loxP-STOP-loxP-tdTomato (or similar fluorescent reporter) [14].

- Tamoxifen: Prepared in corn oil for intraperitoneal injection.

- Confocal Microscope for whole-mount and tissue section imaging.

- Flow Cytometry equipment for cell sorting and analysis.

- Antibodies for key lineage markers (e.g., K5, K8, K14).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Mouse Crosses. Cross the cell-type-specific CreER driver mouse with the reporter mouse to generate experimental cohorts.

- Step 2: Tamoxifen Administration. Administer a high dose of tamoxifen (e.g., 1-3 mg per 25g body weight) to pubertal or adult mice to activate CreER and induce recombination in virtually all cells of the target lineage.

- Step 3: Tissue Harvest and Analysis.

- Time Point 1: Harvest tissue (e.g., mammary gland, prostate) 48-72 hours post-tamoxifen to confirm >95% labeling efficiency in the target population via flow cytometry and confocal microscopy.

- Time Point 2: Allow mice to age through key developmental windows (e.g., puberty, pregnancy) or for several months for homeostasis.

- Step 4: Lineage Analysis. Harvest tissues and prepare whole mounts and sections. Analyze by confocal microscopy and flow cytometry for the presence of the tdTomato reporter in both the originally targeted lineage and the putative sister lineage (e.g., are labeled K5+ basal cells giving rise to K8+ luminal cells?).

- Step 5: Data Interpretation. True multipotency is concluded only if a single, labeled founder cell gives rise to all lineages within the tissue. The persistence of unlabeled cells of a particular lineage indicates the existence of independent, unipotent progenitors [14].

Protocol: Dynamic DNA Barcoding with CRISPR for High-Resolution Phylogeny

This cutting-edge protocol uses CRISPR/Cas9 to generate cumulative, heritable mutations in synthetic DNA barcodes, enabling the reconstruction of high-resolution lineage trees with single-cell RNA-seq readout [15] [17].

1. Principle: A CRISPR/Cas9 system is engineered to target and induce mutations in a specific, heritable genomic barcode locus. With each cell division, new, unique mutations are added, creating a record of lineage relationships that can be read out by sequencing.

2. Materials:

- KP-tracer Mouse Model (or similar): A genetically engineered mouse model (e.g., for Kras;Trp53-driven lung cancer) harboring a Polylox-based or similar CRISPR-recordable barcode array at the Rosa26 locus [17].

- Viral Vectors (if needed): For delivery of Cre recombinase or Cas9/sgRNA.

- Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing (scRNA-seq) platform (e.g., 10X Genomics).

- Bioinformatics Pipelines for phylogenetic tree reconstruction (e.g., provided in [17]).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Barcode Induction. In the model organism, induce the expression of Cas9 and sgRNAs targeting the barcode array. This can be done via tamoxifen-induced Cre or viral delivery.

- Step 2: Tumor Evolution / Development. Allow the tissue (e.g., lung tumor) to evolve over time from a single transformed cell to a metastatic lesion.

- Step 3: Single-Cell Sequencing. At multiple time points, harvest the tissue and dissociate it into a single-cell suspension. Perform scRNA-seq to capture both the transcriptomic state of each cell and the sequence of its heritable barcode.

- Step 4: Phylogenetic Reconstruction.

- Align sequenced barcodes to the original, unmodified reference.

- Construct a phylogenetic tree based on the shared and unique mutations in the barcodes, which reflects the cells' division history.

- Overlay the transcriptional data from the scRNA-seq onto the phylogenetic tree.

- Step 5: Fate and Plasticity Analysis. Identify branching points and clonal expansions. Correlate transcriptional states (e.g., alveolar-type2-like, metastatic) with specific branches to map evolutionary trajectories and identify periods of high transcriptional plasticity [17].

Diagram: Workflow for Dynamic DNA Barcoding Lineage Tracing. The process involves engineering a heritable barcode, its cumulative editing during development/disease, and final phylogenetic analysis with single-cell resolution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Models

This section details key research reagents and model systems central to studying cell fate and plasticity.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Fate and Lineage Tracing Studies

| Reagent / Model | Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cre-loxP System (Inducible: CreER) | Genetically labels a specific cell population and all its progeny in a temporally controlled manner [9] [14]. | Fate mapping of stem cells during development, homeostasis, and regeneration. |

| Multicolor Reporters (Brainbow) | Stochastic expression of multiple fluorescent proteins creates a unique color barcode for each cell, allowing visual tracking of clones [9] [15]. | Visualizing clonal boundaries and cell mingling in tissues like brain and skin. |

| CRISPR Recorder Systems (e.g., Polylox) | Engineered genomic loci that accumulate Cas9-induced mutations over time, serving as dynamic lineage barcodes [15] [17]. | High-resolution, retrospective lineage tracing at single-cell level, esp. in cancer evolution. |

| scRNA-seq Platforms | Profiles the transcriptome of individual cells, defining cell states and inferring developmental trajectories [15] [12] [17]. | Characterizing heterogeneity, identifying novel cell types, and computational fate mapping. |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | A vertebrate model with high embryonic plasticity, optical clarity, and genetic tractability [18] [16]. | Studying transdifferentiation (e.g., melanophore to leucophore) and evolutionary cell fate. |

| Mouse (Mus musculus) | A mammalian model with sophisticated genetic tools (e.g., inducible Cre) and relevance to human biology [14] [17]. | Saturation lineage tracing, studying stem cell dynamics in organs, and modeling disease. |

Diagram: Core Logic of Cell Fate Commitment. Extrinsic and intrinsic signals activate transcription factors that rewire Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs), leading to epigenetic modifications that lock in the new transcriptional state, ensuring a stable fate.

The emergence of sophisticated single-cell technologies has revolutionized our ability to dissect cellular heterogeneity and trace lineage relationships with unprecedented resolution. Lineage tracing, defined as any experimental design aimed at establishing hierarchical relationships between cells, has become an essential approach for understanding cell fate, tissue formation, and human development [7]. When framed within evolutionary biology, these techniques provide a mechanism-based understanding of how cellular phenotypes diversify and adapt over time, linking population genetics principles with cell biological mechanisms [19]. This integration is fundamental to building a quantitative framework for evolutionary cell biology, connecting processes like mutation, selection, and drift to cellular outcomes across the Tree of Life [19]. This article details cutting-edge protocols and analytical frameworks that empower researchers to resolve lineage heterogeneity within this integrative context.

Methodological Foundations in Lineage Tracing

Imaging-Based Lineage Tracing

Imaging-based techniques form the historical cornerstone of lineage analysis, allowing direct observation of spatial relationships and phenotypic outcomes.

- Site-Specific Recombinase Systems: The Cre-loxP system remains a fundamental tool. In this system, Cre recombinase excises a STOP codon flanked by loxP sites, activating a fluorescent reporter gene. Specificity is achieved by driving Cre expression with cell-type-specific promoters. A key limitation is the difficulty in distinguishing clonal groups within a homogenously labelled population, which can be mitigated by sparse labelling approaches (e.g., titrating Tamoxifen in CreERT2 models) to limit recombination to a sparse subset of cells [7].

- Dual Recombinase Systems: Combining Cre-loxP with orthogonal systems like Dre-rox increases experimental flexibility. These systems enable complex genetic operations, such as requiring sequential recombination events to activate a reporter, allowing for more precise fate mapping of cells based on the expression of two genes [7].

- Multicolour Reporter Cassettes: Technologies like Brainbow and R26R-Confetti represent a major advance. These cassettes use stochastic Cre-loxP-mediated recombination to generate a multitude of distinct, heritable fluorescent colors in progenitor cells and their progeny. This allows for clonal analysis at the single-cell level within complex tissues, enabling researchers to visualize multiple lineages simultaneously and track their expansion, migration, and differentiation [7].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized protocol for implementing a multicolour Confetti reporter system for clonal analysis:

Sequencing-Based Lineage Tracing

Sequencing-based methods leverage next-generation sequencing to read out lineage relationships on a massive scale, often coupled with cellular state information.

- Clonal Lineage Tracing with Integrated Barcodes: This method involves stably integrating random lentiviral barcode libraries into a population of progenitor cells. As these cells divide and differentiate, the barcode is faithfully passed to all progeny, creating detectable clones. Key steps include optimizing library diversity to minimize barcode duplication, ensuring stable barcode integration, and capturing barcode information alongside cellular transcriptomes in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) [20].

- Single-Cell Multi-omics Integration: This approach combines lineage barcodes with scRNA-seq, enabling the direct correlation of clonal relationships with transcriptional states (state-fate analysis) [20]. This powerful combination allows researchers to identify transcriptional programs that precede and potentially determine specific cell fate decisions.

The experimental workflow for barcode-based lineage tracing is detailed below, from barcode design to final integrated analysis:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key reagents and tools critical for implementing modern lineage tracing studies.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Single-Cell Lineage Tracing

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cre-loxP System [7] | Cell-type-specific and inducible genetic recombination; reporter activation. | Prospective fate mapping of defined cell populations. |

| R26R-Confetti Reporter [7] | Stochastic multicolour fluorescent labelling. | Intravital clonal analysis and visualization of multiple lineages in parallel. |

| Lentiviral Barcode Libraries [20] | Heritable genetic labelling for high-throughput lineage tracking. | Large-scale, unbiased lineage tracing combined with single-cell transcriptomics. |

| Nucleoside Analogues (e.g., EdU) [7] | Label proliferating cells by incorporating into newly synthesized DNA. | Identification and tracking of actively dividing cell populations. |

| SingleCellExperiment Object [21] | Standardized data structure in R for storing and analyzing single-cell data. | Integration of gene expression, metadata, and lineage barcodes for computational analysis. |

Quantitative Data and Analytical Frameworks

Key Single-Cell Datasets for Lineage Analysis

Publicly available datasets provide a foundational resource for method development and hypothesis generation.

Table 2: Selected Public Single-Cell Datasets for Lineage and Heterogeneity Studies

| Dataset | Description | Cell Count | Access Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tabula Muris [21] | A comprehensive atlas of single-cell transcriptomes from multiple mouse tissues and organs. | ~100,000 cells | CZ CELLxGENE [22] |

| Tabula Sapiens [22] | A multi-organ, single-cell transcriptomic atlas of human cells from various organ donors. | ~500,000 cells | CZ CELLxGENE [22] |

| Deng et al. [21] | Single-cell RNA-seq of 268 cells from mouse preimplantation embryos (oocyte to blastocyst). | 268 cells | Bioconductor |

| Human Pancreas (Muraro/Segerstolpe) [21] | Single-cell transcriptomes of healthy and type 2 diabetic human pancreatic islet cells. | Varies by study | CZ CELLxGENE |

Computational Analysis Workflow

The analysis of single-cell lineage tracing data involves a multi-step computational process to derive biological insights from raw sequencing data. The diagram below outlines the core steps for analyzing barcoded single-cell RNA-seq data, from raw data processing to final biological interpretation:

Key analytical steps include:

- Barcode Assignment and Clonal Grouping: Tools are used to accurately assign cellular barcodes from sequencing data and group cells sharing the same barcode into clones [20].

- Cell Type Annotation and Differential Expression: Automated algorithms (e.g., ScType) and manual annotation using marker genes characterize cell states. Differential expression analysis then identifies genes that are significantly different between clones or between cells within a clone that have adopted different fates [23].

- Trajectory and State-Fate Analysis: Computational methods like Monocle3 perform trajectory inference (pseudotime analysis) to reconstruct the continuum of cell-state transitions [23]. When overlaid with clonal information, this enables state-fate analysis, revealing how progenitor states are linked to descendant fates.

Integrated Protocol: Combining Barcoding and Transcriptomics

This section provides a detailed step-by-step protocol for performing single-cell lineage tracing with expressed barcodes, adapted from established methodologies [20].

Protocol: Single-Cell Lineage Tracing with Expressed Barcodes

Objective: To trace lineage relationships and correlate them with transcriptional states in a population of dividing cells.

Materials:

- Lentiviral barcode library (e.g., with high diversity >10^8 unique barcodes)

- Target cells (e.g., primary stem or progenitor cells)

- Appropriate cell culture media and reagents

- Transduction reagents (e.g., polybrene)

- Single-cell RNA-sequencing platform (e.g., 10x Genomics)

- Computational resources and software (e.g., CellRanger, Seurat/R, Trailmaker [23])

Procedure:

Library Design and Viral Production:

- Clone a complex library of random barcode sequences into a lentiviral expression vector downstream of a strong, ubiquitous promoter. The vector should be designed for transcriptomic capture (e.g., barcode within the polyA transcript).

- Produce high-titer lentiviral particles. Determine the functional titer via transduction of a reference cell line.

Cell Transduction and Clonal Expansion:

- Transduce the target cell population at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI << 1). This ensures most infected cells receive a single, unique barcode, establishing the foundation for clonal resolution.

- Allow cells to expand in vitro or engraft and develop in vivo for a defined period. This expansion phase is critical for generating detectable clones derived from single barcoded progenitors.

Single-Cell Sequencing Library Preparation:

- Harvest cells and prepare a single-cell suspension with high viability.

- Proceed with single-cell RNA-sequencing library preparation according to platform-specific protocols (e.g., 10x Genomics). Ensure that the library preparation captures the barcode sequence as part of the transcriptome.

Sequencing and Data Generation:

- Sequence libraries on an Illumina platform. Ensure sufficient sequencing depth to confidently detect both barcodes and transcriptomes from thousands of single cells.

Data Analysis Workflow

Preprocessing and Barcode Assignment:

- Process raw sequencing data through a pipeline (e.g., CellRanger) to generate a gene expression count matrix.

- Use computational tools to extract barcode sequences from the transcriptomic data and assign them to each cell.

Clonal Grouping and Quality Control:

- Group cells with identical barcode sequences into clones.

- Apply quality filters to remove barcodes with low read counts or those likely resulting from PCR errors or ambient RNA.

Integrated Clonal and Transcriptomic Analysis:

- Import the gene-count matrix and clonal metadata into an analysis environment (e.g., a

SingleCellExperimentobject in R [21] or a commercial platform like Trailmaker [23]). - Perform standard scRNA-seq analysis: normalization, highly variable gene selection, dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP), and clustering.

- Annotate cell clusters based on known marker genes.

- Visualize clonal distributions on UMAP plots to assess fate bias.

- Perform differential expression analysis between clones or between fates within a clone to identify potential fate determinants.

- Import the gene-count matrix and clonal metadata into an analysis environment (e.g., a

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low Clonal Diversity: Optimize transduction efficiency to achieve a low MOI.

- High Doublet Rate: Ensure a proper single-cell suspension and follow platform-specific guidelines for cell loading.

- Clonal Dropouts: Increase sequencing depth for barcode recovery and use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for amplification bias.

The single-cell revolution has provided a powerful toolkit to resolve lineage heterogeneity with extraordinary precision. By integrating sophisticated imaging, high-throughput barcoding, and multi-omics sequencing, researchers can now reconstruct lineage relationships and correlate them with dynamic changes in cell state. Framing these technological advancements within the principles of evolutionary cell biology—considering the roles of mutation, drift, and selection in shaping cellular phenotypes—enriches the interpretation of lineage data. As these protocols become more accessible and computational tools continue to evolve, the field is poised to unlock deeper insights into the fundamental processes of development, disease, and evolution at their most basic cellular level.

A Technical Deep Dive: Modern Lineage Tracing Tools and Their Applications

Site-specific recombinases (SSRs) have revolutionized our ability to decipher the lineage relationships between cells, providing a powerful toolkit for understanding evolutionary processes at the cellular level. These molecular tools enable researchers to permanently mark progenitor cells and track the fate of their descendants through development, homeostasis, and disease. The Cre-loxP system, derived from bacteriophage P1, has served as the foundational technology for lineage tracing for decades, allowing for precise genetic manipulations in a spatiotemporally controlled manner [24]. As research questions have evolved toward understanding more complex biological systems, the recombinase toolbox has expanded to include orthogonal recombinase systems such as Dre-rox and Flp-FRT, which operate independently without cross-reactivity [5]. This expansion enables researchers to simultaneously track multiple cell populations or interrogate how different lineages interact, offering unprecedented insight into the cellular ecosystems that underlie tissue formation, regeneration, and disease evolution. The continuous development of these technologies—from single recombinase systems to sophisticated multi-recombinase platforms—represents a paradigm shift in our ability to reconstruct cellular phylogenies and understand the rules governing cell fate decisions in an evolutionary context.

The Recombinase Toolbox: Mechanisms and Molecular Properties

Site-specific recombinases are enzymes that recognize specific DNA sequences and catalyze recombination between them, leading to excision, integration, inversion, or translocation of DNA fragments. The Cre-loxP system remains the gold standard, where Cre recombinase recognizes 34-base pair loxP sites consisting of two 13-bp inverted repeats flanking an 8-bp asymmetric core that determines orientation [24]. The versatility of this system stems from the ability to control recombination through tissue-specific promoters and inducible systems such as CreERT2, which requires tamoxifen administration for nuclear translocation and activity [24].

Recent engineering advances have substantially expanded the recombinase repertoire. The Dre-rox system, a close relative of Cre-loxP, demonstrates similar efficiency but maintains orthogonal specificity [25]. Additionally, several yeast-derived recombinases (KD, B2, B3, R) have been shown to function efficiently in animal systems with distinct target specificities, enabling more complex genetic manipulations [25]. Large serine recombinases (LSRs) represent another valuable class, capable of mediating direct, site-specific genomic integration of multi-kilobase DNA sequences without pre-installed landing pads [26].

Table 1: Key Site-Specific Recombinase Systems and Their Properties

| Recombinase System | Origin | Target Site | Key Features | Applications in Lineage Tracing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cre-loxP | Bacteriophage P1 | loxP (34 bp) | Gold standard; high efficiency; temporal control with CreERT2 | Conditional knockout; single-lineage tracing [24] |

| Dre-rox | Bacteriophage D6 | rox (32 bp) | Orthogonal to Cre-loxP; similar efficiency | Dual recombinase systems; intersectional lineage tracing [5] |

| Flp-FRT | S. cerevisiae | FRT (34 bp) | Early alternative to Cre; lower efficiency at 37°C | Genetic manipulation in multiple model systems [5] |

| KD, B2, B3, R | Yeast species | B2RT, B3RT, KDRT, RSRT (34-40 bp) | Four non-cross-reacting pairs; low toxicity | Complex lineage tracing; parallel independent manipulations [25] |

| Large Serine Recombinases (e.g., Dn29) | Bacterial genomes | attP/attB | Unidirectional integration; large cargo capacity | Direct genomic integration without landing pads [26] |

Advanced Applications in Lineage Tracing and Evolutionary Biology

Dual Recombinase Systems for Intersectional Lineage Tracing

Dual recombinase systems have emerged as powerful tools for addressing one of the fundamental challenges in lineage tracing: precisely defining the origin of regenerative cells or distinguishing contributions from multiple progenitor populations simultaneously. By combining Cre-loxP with Dre-rox, researchers can achieve intersectional labeling where expression occurs only when both recombinases are active in the same cell, or when one is present and another absent [7]. This approach was successfully employed to determine the origin of regenerative cells in remodeled bone, distinguishing otherwise homogenous periosteal tissue into distinct layers and evaluating their respective contributions to fracture healing [7]. Similarly, this strategy clarified the cellular origins of alveolar epithelial stem cells post-injury by simultaneously tracking multiple epithelial cell populations [7]. A recent methodological advancement demonstrated a dual recombinase system that synchronously labels cell membranes with tdTomato and nuclei with PhiYFP, enabling clear observation of nuclear and membrane dynamics during lineage tracing [27].

Multicolor Labeling and Clonal Analysis

The development of multicolor reporter cassettes represents another major advancement in imaging-based lineage tracing. The Brainbow system, capable of expressing up to four different fluorescent proteins through stochastic Cre-loxP-mediated excision and/or inversion, enables researchers to distinguish multiple clones within the same tissue [7]. The R26R-Confetti reporter, one of the most popular adaptations, has been widely applied for clonal analysis at the single-cell level across diverse tissues including hematopoietic, epithelial, kidney, and skeletal cells [7]. These multicolor approaches are particularly valuable for studying clonal expansion and cell fate plasticity in evolutionary contexts, as they visually reveal how specific progenitors contribute to tissue formation and maintenance. Recent applications include intravital imaging to trace macrophage origin and proliferation in mammary glands in real time, offering insights into cellular dynamics during organogenesis [7].

Single-Cell Lineage Tracing with DNA Barcodes

The integration of DNA barcoding technologies with single-cell RNA sequencing has propelled lineage tracing into the era of high-throughput analysis, enabling simultaneous interrogation of lineage relationships and transcriptomic profiles in thousands of individual cells [28]. Three primary barcoding strategies have emerged:

- Integration barcodes: Utilizing retroviral libraries to introduce unique, heritable DNA sequences that serve as clonal markers [29]

- CRISPR barcodes: Leveraging CRISPR/Cas9 to generate cumulative insertions and deletions that serve as genetic landmarks for lineage reconstruction [28]

- Polylox barcodes: Employing Cre-loxP recombination to generate diverse barcode combinations through stochastic rearrangements [29]

These approaches are particularly powerful for reconstructing cellular phylogenies and understanding hematopoietic stem cell heterogeneity, as they can track the contribution of individual stem cells to the entire blood system with clonal resolution [29]. A recent breakthrough using base editors has further enhanced recording capacity by creating more informative sites to document cell division events, enabling reconstruction of more detailed cell lineage trees with higher statistical support [29].

Diagram 1: Single-Cell Lineage Tracing Workflow. This workflow illustrates the key steps in single-cell lineage tracing experiments, from initial barcode integration in progenitor cells to final lineage reconstruction and transcriptomic analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Dual Recombinase-Mediated Lineage Tracing with Membrane and Nuclear Labeling

This protocol describes a method for synchronized lineage tracing of cell membranes and nuclei using Cre and Dre recombinases, enabling precise fate mapping with subcellular resolution [27].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Dual Recombinase Lineage Tracing

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Mice | R26R-tdT; PhiYFP-nuc | Express fluorescent proteins upon recombination | Confirm specific localization (membrane vs. nuclear) |

| Cre-Driver Mice | Tissue-specific Cre or CreERT2 (e.g., Cdh5-Cre) | Control recombination in specific cell types | Validate specificity and efficiency before experiments |

| Dre-Driver Mice | Tissue-specific Dre or DreERT2 (e.g., Prox1-Dre) | Provide orthogonal recombination control | Ensure no cross-reactivity with Cre system |

| Inducing Agents | Tamoxifen (for CreERT2/DreERT2) | Temporally control recombinase activation | Optimize dose for sparse vs. dense labeling |

| Imaging Equipment | Confocal/intravital microscopy | Visualize and track labeled cells | Ensure capability for multi-color fluorescence |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Mouse Model Generation:

- Cross appropriate Cre-driver and Dre-driver mice with reporter mice containing loxP-stop-loxP-tdTomato (membrane-localized) and rox-stop-rox-PhiYFP (nuclear-localized) cassettes.

- Genotype offspring to identify mice with all required alleles. Allow at least 2 weeks after weaning for transgene expression stabilization.

Sparse Labeling Induction:

- For inducible systems (CreERT2/DreERT2), prepare tamoxifen solution (20 mg/mL in corn oil).

- Administer tamoxifen intraperitoneally at a titrated dose (typically 1-5 mg per 25 g body weight) to achieve sparse labeling. Lower doses label fewer cells for higher clonal resolution.

- For simultaneous dual recombination, administer both inducers together or sequentially based on experimental design.

Tissue Collection and Processing:

- At desired time points post-induction, euthanize animals and harvest tissues of interest.

- For whole-mount imaging, fix tissues in 4% PFA for 2-4 hours at 4°C depending on tissue size.

- For sectioning, cryopreserve tissues in OCT compound or process for paraffin embedding.

Imaging and Analysis:

- Image whole-mount tissues or sections using confocal microscopy with appropriate filter sets for tdTomato (excitation 554 nm, emission 581 nm) and PhiYFP (excitation 515 nm, emission 528 nm).

- For intravital imaging, surgically expose the tissue of interest and use a specialized imaging chamber to maintain physiological conditions.

- Process images to quantify clone size, distribution, and morphological features using software such as ImageJ or Imaris.

Validation and Controls:

- Include control animals lacking one or both recombinases to confirm specific labeling.

- Validate cell identity using immunohistochemistry for cell-type-specific markers.

- For proliferation studies, incorporate EdU labeling (1 mg per 25 g body weight, administered 4-6 hours before sacrifice) to detect recently divided cells.

Protocol: Programmable Chromosome Engineering for Evolutionary Studies

Recent advances in recombinase engineering have enabled programmable chromosome engineering (PCE), allowing precise manipulation of large DNA fragments for studying evolutionary processes [30]. This protocol outlines the use of engineered Cre-loxP systems for megabase-scale chromosomal rearrangements.

Materials and Reagents

- Engineered Cre variants: AiCE-evolved Cre with enhanced efficiency and specificity

- Asymmetric lox sites: Novel lox variants that minimize reversible recombination

- Prime editing components: PE2 protein and re-pegRNA for scarless editing

- Delivery system: Appropriate vectors for your model organism (e.g., AAV for mammalian cells)

Step-by-Step Methodology

System Design:

- Identify target genomic regions for rearrangement (inversion, translocation, deletion).

- Design asymmetric lox sites flanking the target region to prevent backward recombination.

- Design re-pegRNAs to precisely replace residual lox sites with original genomic sequence after rearrangement.

Component Delivery:

- Co-deliver engineered Cre recombinase, asymmetric loxP donor constructs, and prime editing components to target cells.

- For in vivo applications, use viral vectors (e.g., AAV) with appropriate tropism for your tissue of interest.

- Optimize delivery efficiency using reporter constructs and titrate components to minimize toxicity.

Screening and Validation:

- Isolate successfully edited cells or organisms using selection markers or fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

- Validate rearrangements using PCR, Southern blotting, and long-read sequencing (Oxford Nanopore or PacBio).

- Confirm the absence of residual lox sites and off-target rearrangements through whole-genome sequencing.

Phenotypic Characterization:

- Assess the functional consequences of chromosomal rearrangements on gene expression using RNA-seq.

- Evaluate phenotypic changes in relevant evolutionary contexts (e.g., herbicide resistance in plants, developmental defects in animals).

Diagram 2: Programmable Chromosome Engineering Workflow. This diagram illustrates the key steps in advanced genome architecture programming using engineered Cre recombinases and prime editing for scarless modifications.

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Advanced Recombinase Systems

| System/Application | Efficiency | Specificity | Cargo Capacity | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type Cre-loxP | High (up to 100% excision) | Moderate (native loxP sites) | Limited by delivery vector | Baseline for comparison [24] |

| Engineered LSRs (Dn29 variants) | Up to 53% integration | 97% genome-wide specificity | Up to 12 kb | superDn29-dCas9: 53% efficiency, 97% specificity [26] |

| Programmable Chromosome Engineering | High for large rearrangements | Enhanced via asymmetric lox sites | Up to megabase scale | 315-kb inversion in rice; 18.8 kb insertion [30] |

| Dual Cre/Dre Systems | Varies with promoters | High with intersectional approaches | Standard reporter capacity | Enables fate mapping of overlapping populations [7] [27] |

| Single-Cell Barcoding | Varies by method (20-80%) | Limited by barcode diversity | N/A (records divisions) | Base editors: >20 mutations/barcode [29] |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The evolving landscape of site-specific recombinase technologies continues to transform our approach to studying cellular evolution and lineage relationships. Current developments point toward several exciting future directions, including the integration of recombinase systems with single-cell multi-omics technologies, enabling simultaneous reconstruction of lineage history and comprehensive molecular profiling. Additionally, the ongoing engineering of highly specific recombinases with minimal off-target effects through machine learning-guided design will further enhance the precision of genetic manipulations [26] [30]. The application of these technologies to human organoids and in vivo models of human disease will provide unprecedented insights into the cellular origins of pathology and the evolutionary trajectories of diseased cell populations.

In conclusion, the expansion of the recombinase toolbox beyond Cre-loxP to include orthogonal systems, engineered variants with enhanced properties, and integration with complementary genome editing technologies has dramatically increased the resolution and scale at which we can trace cellular lineages. These advances are not merely technical improvements but represent fundamental enhancements to our ability to test hypotheses about cellular behavior in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease evolution. As these technologies continue to mature and become more accessible, they will undoubtedly yield new insights into the rules governing cell fate decisions and the cellular phylogenies that underpin complex biological systems.

Multicolor and Dual Recombinase Systems for Complex Lineage Mapping

Lineage tracing remains an indispensable methodology for understanding cell fate, tissue formation, and the evolutionary trajectories of cellular populations in multicellular organisms [7]. It encompasses any experimental design aimed at establishing hierarchical relationships between cells, making it fundamental for studying developmental biology, regenerative processes, and disease pathogenesis [7] [5]. In an evolutionary context, these techniques allow researchers to reconstruct developmental pathways that may reflect ancestral relationships and selective pressures. Modern lineage tracing studies are rigorous and multimodal, integrating advanced microscopy, state-of-the-art sequencing, and diverse biological models to validate hypotheses through multiple methodological avenues [7].

The evolution of lineage tracing technologies has progressed from direct observation and dye labeling to sophisticated genetic tools that provide permanent, heritable markers [5]. While traditional imaging-based approaches remain central to the field, the integration of sequencing technologies has revolutionized our capacity to formulate and validate lineage-tracing hypotheses at single-cell resolution [7]. This review focuses specifically on multicolor and dual recombinase systems—cutting-edge approaches that enable researchers to unravel complex lineage hierarchies with unprecedented precision, thereby offering insights into the evolutionary mechanisms that shape cellular diversity and tissue complexity.

Technological Foundations

Core Recombinase Systems

Central to modern genetic lineage tracing are site-specific recombinase (SSR) systems, with Cre-loxP being the most fundamental and widely utilized [7]. The Cre recombinase, derived from P1 bacteriophage, catalyzes recombination between specific 34-base pair DNA sequences known as loxP sites [31]. This system enables precise genetic modifications—including deletion, inversion, or exchange of DNA sequences—when loxP sites are strategically arranged [5].

A foundational labeling strategy is the loxP-Stop-loxP (LSL) system, where Cre-mediated excision removes a transcriptional STOP cassette flanked by tandem loxP sites, thereby activating a downstream reporter gene [5]. The specificity of this activation depends on Cre expression, which can be driven by cell-type-specific promoters or induced temporally using fusion proteins like CreER (a fusion with the estrogen receptor ligand-binding domain) that translocate to the nucleus upon tamoxifen administration [31]. This temporal control allows researchers to initiate labeling within specific developmental windows, a crucial capability for studying evolutionary transitions in cell fate.

Other recombinase systems include Dre-rox (from D6 bacteriophage), Flp-frt (from Saccharomyces cerevisiae), and Nigri-nox, which operate on similar principles but recognize distinct target sequences [31] [5]. The orthogonality of these systems—their ability to function independently without cross-reactivity—enables their combination for more sophisticated lineage tracing approaches [5].

The Advent of Multicolor and Dual Recombinase Systems

Conventional lineage tracing using single fluorescent reporters provides valuable population data but faces limitations in resolving clonal relationships at the single-cell level, particularly when distinguishing adjacent clonal populations within homogenously labeled tissues [7]. Sparse labeling approaches, where the inducing agent (e.g., tamoxifen in CreERT2 models) is titrated to limit recombination to a subset of cells, can mitigate this issue but increase experimental variability and require extensive sampling [7].

Multicolor and dual recombinase systems represent significant advancements that overcome these limitations. Multicolor approaches, such as the "Brainbow" technology and its derivative R26R-Confetti, utilize stochastic Cre-loxP-mediated excision to activate one of multiple possible fluorescent proteins within individual cells [7]. This creates a diverse color palette that enables simultaneous tracking of numerous clones within the same tissue.

Dual recombinase systems combine orthogonal recombinase systems (e.g., Cre-loxP with Dre-rox) to implement Boolean genetic logic—OR, AND, and NOT gates—for precise cellular targeting [31]. These approaches significantly improve resolution by enabling more specific labeling of cell populations, capturing transient gene activation, and performing sophisticated genetic manipulations that were previously unattainable with single-recombinase systems [31]. The enhanced precision of these methods makes them particularly valuable for investigating evolutionary questions about cellular plasticity and fate restriction across different species and developmental contexts.

Multicolor Lineage Tracing Systems

Principles and Mechanisms

Multicolor lineage tracing systems operate on the principle of stochastic DNA recombination to generate diverse fluorescent signatures in individual cells and their progeny. The original Brainbow system utilizes multiple pairs of loxP sites arranged within a genetic cassette to facilitate mutually exclusive recombination events through excision and/or inversion [7]. Each recombination event produces a distinct configuration that places a different fluorescent protein gene under transcriptional control, resulting in expression of cyan, yellow, red, or other fluorescent proteins depending on the construct design [7].

The R26R-Confetti reporter, one of the most popular adaptations, builds upon this concept with optimized fluorescent proteins and integration into the Rosa26 locus, ensuring widespread applicability to existing Cre models [7]. In this system, Cre-mediated recombination randomly selects one of four possible fluorescent reporters (nGFP, YFP, RFP, or CFP), creating a heritable color signature that is passed to all descendant cells. This approach enables clonal analysis at single-cell resolution by providing spatial separation of clones based on distinct color signatures, even within densely populated tissues.

Quantitative Applications and Data Interpretation

Multicolor Clonal Analysis

The quantitative power of multicolor lineage tracing enables rigorous assessment of stem cell potential and clonal dynamics. Wuidart et al. developed statistical frameworks for analyzing multicolor data to define multipotency potential with high confidence [14]. Their approach involves:

- Clonal Analysis: Tracking the composition and spatial distribution of individual colored clones over time

- Lineage Tracing at Saturation: Labeling all stem cells within a given lineage to assess cellular "flux" between different lineages

- Statistical Modeling: Applying probabilistic models to distinguish true multipotency from coincidental labeling of adjacent unipotent progenitors

Their work demonstrated that whereas the prostate develops from multipotent stem cells, only unipotent stem cells mediate mammary gland development and adult tissue remodeling [14]. This methodology provides a rigorous framework for assessing lineage relationships and stem cell fate across different organs and evolutionary contexts.

Table 1: Multicolor Reporter Systems and Their Applications

| System Name | Fluorescent Reporters | Mechanism | Key Applications | Tissues Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brainbow | Up to 4 FPs (CFP, YFP, RFP, etc.) | Stochastic Cre-loxP excision/inversion | Neural lineage mapping [7] | Brain, retina [7] |

| R26R-Confetti | nGFP, YFP, RFP, CFP | Stochastic activation of one FP | Clonal analysis at single-cell level [7] | Hematopoietic, epithelial, kidney, skeletal [7] |

| MARCM | GFP (positively labeled clones) | GAL4/UAS with FLP-FRT mitotic recombination | Drosophila neural development [7] | Brain, imaginal discs [7] |

Protocol: Multicolor Clonal Analysis in Mammary Gland

Application: Assessing stem cell potency and clonal dynamics during postnatal development [14]

Materials:

- K14-CreER or K5-CreER transgenic mice (basal cell-specific)

- R26R-Confetti reporter mice

- Tamoxifen (prepared in corn oil)

- Tissue culture reagents for whole-mount preparation

- Confocal microscopy equipment

Procedure:

- Mouse Crosses: Breed K14-CreER or K5-CreER mice with R26R-Confetti reporter mice to generate experimental animals.

- Tamoxifen Induction: Administer tamoxifen (100-200 μg/g body weight) intraperitoneally to pubertal (4-6 week) female mice to induce stochastic recombination.

- Temporal Analysis: Sacrifice mice at specific time points post-induction (e.g., 1 week, 4 weeks, 12 weeks) to track clonal evolution.

- Tissue Processing:

- Dissect mammary glands and prepare whole mounts

- Fix tissues in 4% PFA for 2 hours at 4°C

- Permeabilize with 1% Triton X-100 overnight

- Counterstain with DAPI for nuclear visualization

- Imaging and Analysis:

- Acquire z-stack images using confocal microscopy with appropriate filter sets for each fluorescent protein

- Reconstruct entire mammary gland ducts using tile scanning

- Identify and map individual clones based on color signatures

- Quantify clone size, composition (basal vs. luminal cells), and spatial distribution

Interpretation: True multipotency is indicated by individual colored clones containing both basal (K5/K14+) and luminal (K8/K18+) cells. Unipotent stem cells generate single-lineage clones restricted to either basal or luminal compartments [14].

Dual Recombinase Systems for Enhanced Resolution

Boolean Logic for Precise Cell Targeting

Dual recombinase systems implement genetic Boolean logic (OR, AND, NOT) to achieve unprecedented specificity in cell lineage tracing [31]. These systems typically combine Cre-loxP with Dre-rox, two orthogonal recombinase systems that function independently without cross-reactivity [31] [5].

OR-logic strategies target cells expressing either of two markers, enabling comprehensive labeling of heterogeneous populations. AND-logic approaches require simultaneous expression of two markers, allowing precise targeting of specific cell subtypes. NOT-logic configurations exclude certain cell populations from labeling, refining specificity by eliminating confounding signals [31].

The DeaLT (Dual-recombinase-Activated Lineage Tracing) system exemplifies this approach, utilizing interleaved or nested reporter designs where Dre-rox recombination controls subsequent Cre-loxP recombination [31]. This sequential logic enables precise fate mapping by preventing ectopic labeling of non-target cells that might express one marker but not both.

Protocol: AND-Logic Fate Mapping of Bronchioalveolar Stem Cells

Application: Specific lineage tracing of bronchioalveolar stem cells (BASCs) in lung homeostasis and regeneration [31]

Materials:

- Sftpc-DreER transgenic mice (alveolar type 2 cell-specific)

- Scgb1a1-CreER transgenic mice (club cell-specific)

- R26-RSR-tdTomato reporter mice

- Tamoxifen

- Lung injury models (e.g., naphthalene, bleomycin)

- Tissue processing equipment for lung analysis

Procedure:

- Mouse Crosses: Generate Sftpc-DreER; Scgb1a1-CreER; R26-RSR-tdTomato triple transgenic mice.

- Tamoxifen Induction: Administer tamoxifen (75-150 mg/kg) to adult mice (8-12 weeks) to activate both DreER and CreER recombinases.

- Injury Models (optional):

- For naphthalene injury: Administer 200 mg/kg naphthalene intraperitoneally in corn oil

- For bleomycin injury: Administer 2-3 U/kg bleomycin intratracheally

- Tissue Collection and Analysis:

- Perfuse lungs with PBS followed by 4% PFA

- Inflate lungs with 1% low-melting point agarose for spatial preservation

- Prepare cryosections or whole mounts for imaging

- Immunostain for lineage markers (SPC for AT2 cells, CC10 for club cells, T1α for AT1 cells)

- Image Analysis:

- Quantify tdTomato+ BASCs and their progeny

- Assess differentiation into AT1, AT2, or club cell lineages

- Determine proliferation rates via EdU incorporation or Ki67 staining

Interpretation: AND-logic labeling specifically marks BASCs co-expressing Sftpc and Scgb1a1, enabling precise fate mapping during homeostasis and regeneration. This approach has demonstrated that BASCs serve as a source of alveolar regeneration after lung injury [31].

Dual Recombinase Logic Gates

Protocol: Synchronized Membrane and Nuclear Labeling

Application: High-resolution lineage tracing with simultaneous membrane and nuclear labeling for detailed morphological analysis [27]

Materials:

- Appropriate Cre and Dre driver lines (tissue-specific)

- Dual reporter mice (e.g., membrane tdTomato + nuclear PhiYFP)

- Tamoxifen or respective inducers

- Intravital imaging equipment

- Confocal or light-sheet microscopy systems

Procedure:

- System Configuration:

- Utilize reporting systems with Cre, Dre, or Dre+Cre mediated recombination

- Design constructs with tdTomato targeted to cell membrane (e.g., via CAAX box)

- Include nuclear-localized PhiYFP for simultaneous nuclear tracking

- Animal Model Generation:

- Cross appropriate Cre and Dre drivers with dual reporter mice

- Validate specific labeling in target tissues (e.g., cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes)

- Temporal Induction:

- Administer tamoxifen or other inducers at desired developmental timepoints

- For proliferation studies, combine with ProTracer system for enhanced precision

- Imaging and Analysis:

- Perform intravital imaging for dynamic visualization

- Acquire three-dimensional image stacks for structural analysis

- Track nuclear positioning and membrane dynamics over time

- Quantify morphological parameters during differentiation processes

Interpretation: This system enables clear observation of both nucleus and membrane, allowing for comprehensive analysis of cell morphology, division patterns, and migration behaviors during development and disease progression [27].

Quantitative Analysis and Data Interpretation

Statistical Framework for Lineage Tracing Data

Robust interpretation of lineage tracing data requires rigorous statistical frameworks to distinguish true multipotency from experimental artifacts [14]. Key considerations include:

- Labeling Specificity: Precise characterization of initial Cre/LoxP recombination specificity using single-timepoint analysis before significant cell division occurs [14].

- Clonal Analysis Distinction: Differentiating between multipotent stem cells generating dual-lineage clones versus adjacent unipotent progenitors independently labeled by imperfectly specific Cre drivers [14].

- Saturation Labeling: Implementing lineage tracing at saturation, where all stem cells within a given lineage are labeled, to assess cellular "flux" between lineages and avoid sampling bias [14].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Genetic Lineage Tracing

| Issue | Potential Causes | Solutions | Control Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|