The Womb's Whisper

How Developmental Psychobiology Rewrites Our Understanding of Life's Beginnings

Exploring how early experiences shape our brains, behaviors, and mental health across the lifespan

The Silent Symphony of Development

What if the seeds of our mental health are sown not in the turbulent years of adolescence, but in the silent, secret world of the womb? This provocative question lies at the heart of developmental psychobiology, an interdisciplinary science that explores how early life experiences—beginning even before birth—alter behavioral and brain development, canalizing development to suit different environments 3 .

Decades of research have demonstrated that the developing organism's trajectory is influenced by environmental factors beginning in the fetus and extending through adolescence, with the specific timing and nature of the environmental influence having unique impact on adult mental health 3 .

This field represents a revolutionary fusion of psychology, biology, neuroscience, and genetics, revealing how the delicate dance between our genes and environment shapes who we become. From a mother's stress during pregnancy to an infant's first bond with a caregiver, developmental psychobiology unveils how seemingly small early experiences orchestrate a lifetime of psychological and biological outcomes.

Laying the Groundwork: Key Concepts and Theories

What is Developmental Psychobiology?

Developmental psychobiology investigates biological, genetic, neurological, psychosocial, cultural, and environmental factors of human growth across the complete lifespan 1 . It starts from a revolutionary premise: the infant brain is not merely an immature version of the adult brain, but is uniquely designed to function within the ecological niche of infancy 3 .

Nature-Nurture Dialogue

The polarized debate between genes and environment has evolved into understanding how behavioral and environmental influences affect the very expression of genes through epigenetic mechanisms 1 .

Lifelong Neuroplasticity

The brain remains shaped by experience throughout life, but there are sensitive periods in early development when neural circuits are exceptionally receptive to environmental input 3 .

Interdisciplinary Approach

Understanding development requires integrating multiple levels of analysis, from genes and cells to broad sociocultural systems 8 .

Foundational Theories of Development

While developmental psychobiology represents a modern interdisciplinary approach, it builds upon foundational theories that first recognized the significance of early development:

| Theorist | Theory | Core Concept | Developmental Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jean Piaget 1 | Cognitive Development | Children move through four stages of intellectual development | Childhood |

| John Bowlby 1 | Attachment Theory | Early infant-caregiver bonds shape future relationships and security | Infancy to Adulthood |

| Erik Erikson 7 | Psychosocial Development | Personality develops through eight stages of confronting psychological crises | Entire Lifespan |

| Sigmund Freud 1 | Psychosexual Development | Personality formed through five stages focused on different erogenous zones | Childhood |

These pioneering theories established the crucial understanding that early experiences matter profoundly, and development occurs through distinct phases with unique characteristics and challenges 1 .

The Scientist's Toolkit: Methods and Approaches

Decades of research in developmental psychobiology have demonstrated the profound, enduring effects of early life experience on behavioral development using various animal models, with this work quickly replicated in nonhuman primates and applied to humans 3 . The field employs ingenious research methods tailored to the capabilities of developing humans at different stages.

Specialized Research Methods

Infant-Friendly Approaches

Since infants cannot follow verbal instructions or report their experiences, researchers have developed creative methods to understand their world. Habituation procedures capitalize on the fact that infants look longer at novel stimuli relative to familiar items 2 .

In one classic study, researchers used this method to demonstrate that infants as young as 3½ months understand object permanence—knowing something exists even when hidden—much earlier than previously believed 2 .

Psychophysiological Measures

Modern developmental psychobiology increasingly incorporates psychophysiological data such as measures of heart rate, hormone levels, or brain activity to understand bidirectional relations between biology and behavior 2 .

Event-related potentials (ERPs), recorded through sensors on the scalp, reveal how infants' brains respond to different stimuli, helping identify neural markers of future developmental risks 2 .

Voluntary Response Measures

As children develop, researchers can study their understanding through voluntary behaviors. The elicited imitation procedure, for instance, assesses recall memory in preverbal children by having them recreate action sequences with novel toys 2 .

Through this method, we've learned that 6-month-old infants remember one step of a 3-step sequence for 24 hours, while 20-month-olds remember the individual steps and temporal order of 4-step events for at least 12 months 2 .

A Closer Look: The Maternal Immune Activation Experiment

Background and Methodology

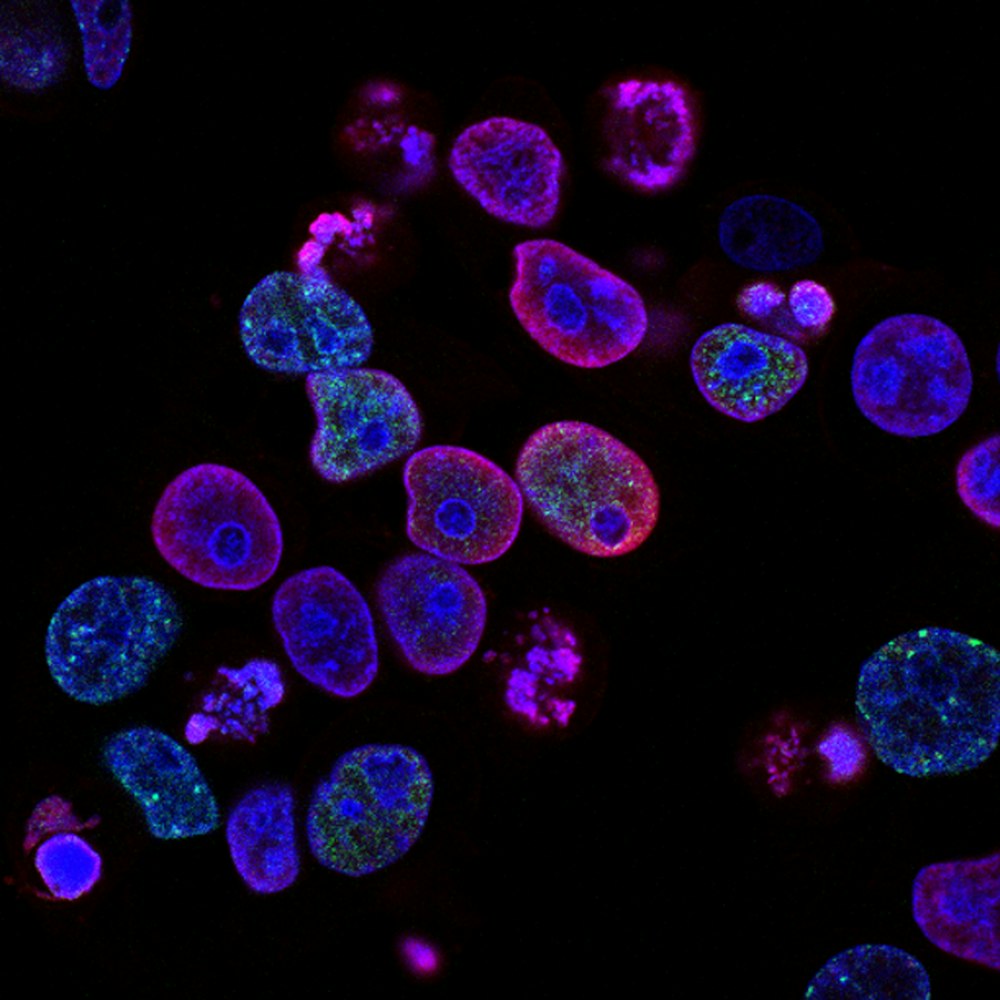

One illuminating example of developmental psychobiology research comes from studies investigating how maternal immune activation during pregnancy influences fetal brain development 3 . This research was motivated by epidemiological studies showing that maternal bacterial and viral infections during pregnancy are linked to neuropsychiatric disorders with presumed neurodevelopmental origins, including schizophrenia and autism 3 .

Researchers hypothesized that it wasn't necessarily the specific infectious agent that mattered, but rather the mother's immune response to the infection. To test this, they designed an elegant experiment:

Experimental Design

- Subject Population: Pregnant mouse dams

- Immune Stimulation: A single intravenous injection of PolyI:C

- Control Groups: Pregnant dams receiving a placebo injection

- Outcome Measures: Comprehensive behavioral, cognitive, and neurobiological assessment of offspring

Scientific Premise

The immune response would release proinflammatory cytokines—proteins that function as chemical mediators of immune response—which would then cross the placental barrier and alter the development of the fetal brain 3 .

Results and Implications

The findings were striking: adult offspring whose mothers experienced immune activation during pregnancy displayed multiple psychosis-related abnormalities after puberty, including sensory processing deficits, learning impairments, and heightened sensitivity to psychoactive drugs 3 .

| Domain Assessed | Key Finding in Adult Offspring | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sensorimotor Processing | Deficits in prepulse inhibition | Mimics sensory gating problems in schizophrenia |

| Learning and Memory | Impaired working memory and cognitive flexibility | Reflects cognitive deficits in psychiatric disorders |

| Drug Sensitivity | Enhanced response to psychoactive drugs | Suggests altered neurodevelopmental trajectory |

| Social Behavior | Reduced social interaction and preference | Models social withdrawal in certain disorders |

This research demonstrates the fetal origins of mental health, revealing how an environmental insult during a specific developmental period can predispose individuals to psychological disorders that don't manifest until decades later 3 . The faulty development of the central nervous system initiated in utero may remain relatively silent and only lead to overt psychopathological traits in later life 3 .

From Lab to Life: Applications and Future Directions

The insights from developmental psychobiology are transforming how we support healthy development and address mental health challenges across the lifespan.

Early Intervention and Prevention

Understanding that early experiences canalize development has led to fundamental shifts in intervention strategies. Research now supports:

Prenatal Support Programs

Recognizing that maternal psychological and physical health during pregnancy can shape fetal neurodevelopment, there's growing emphasis on supporting maternal mental health and reducing stress during pregnancy 3 .

Attachment-Based Interventions

Based on Bowlby's attachment theory, programs now help caregivers provide the sensitive, responsive care that promotes secure attachment relationships, known to support healthy emotional regulation 1 .

Early Childhood Policies

Evidence about sensitive periods in brain development has informed early childhood education initiatives and support systems, recognizing that early investments yield lifelong returns 3 .

The Future of Developmental Psychobiology

The field is rapidly evolving with several exciting directions:

Precision Mental Health

There's a growing movement toward precision mental health approaches that use multilevel data (genetic, neural, behavioral) to personalize interventions and improve outcomes 8 . This recognizes the incredible heterogeneity in development—multiple pathways can lead to the same outcome (equifinality), and similar starting points can lead to different outcomes (multifinality) 8 .

Technology Integration

Digital and mobile technologies are creating new research and intervention possibilities. Ecological momentary assessment via smartphones allows researchers to study moods and behaviors in real time in natural environments 8 . Meanwhile, wearable sensors can measure physiology, physical activity, sleep, and social interactions in unprecedented detail 8 .

Lifespan and Cultural Expansion

The field is increasingly extending beyond its traditional focus on childhood to examine development across the entire lifespan, recognizing that developmental processes continue into late adulthood 8 . There's also growing emphasis on investigating culture at multiple levels and incorporating macro-level influences into developmental research 8 .

Conclusion: The Developmental Dance

Developmental psychobiology has taken us on a remarkable journey—from seeing development as a predetermined genetic blueprint to understanding it as a dynamic, ongoing dance between our biology and our experiences, beginning before birth and continuing throughout our lives.

This interdisciplinary science has revealed that our earliest experiences, even those we cannot consciously remember, whisper through our neural architecture, emotional patterns, and relationship capacities across our entire lifespan.

The future of this field points toward more personalized, preventative approaches to mental health that respect individual developmental pathways while recognizing our shared human need for nurturing environments.

As we continue to unravel the complexities of development, we move closer to a world where we can support every child's potential and understand that caring for developing minds begins not when problems emerge, but from life's very first moments—and even before.