Skill Factor in Multifactorial Evolution: Definition, Mechanisms, and Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the 'skill factor,' a core component in Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms (MFEAs).

Skill Factor in Multifactorial Evolution: Definition, Mechanisms, and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the 'skill factor,' a core component in Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms (MFEAs). Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational definition of the skill factor as the task an individual solves best, its role in enabling efficient multi-task optimization, and the critical challenge of managing knowledge transfer between tasks. The content covers theoretical foundations, practical algorithmic implementation, strategies for optimizing performance by avoiding negative transfer, and validation through benchmarking. The discussion highlights the potential of MFEAs to solve complex, concurrent optimization problems in biomedical science, such as drug design and clinical protocol optimization.

What is a Skill Factor? Core Concepts and Theoretical Foundations of Multifactorial Evolution

This whitepaper delineates the conceptual and technical dimensions of the skill factor within multifactorial evolution research, tracing its pathway from foundational biological principles to sophisticated algorithmic implementation. The skill factor, originally formalized in evolutionary computation as a mechanism for explicit knowledge transfer in multitasking environments, represents a pivotal construct for enhancing optimization efficiency in complex problem domains. We examine its theoretical underpinnings in multifactorial inheritance, its operationalization in evolutionary multitasking optimization (EMT) algorithms, and its practical implications for drug discovery and development workflows. By integrating quantitative analyses, detailed experimental protocols, and visual frameworks, this guide provides researchers with both the theoretical foundation and practical toolkit for implementing skill factor-driven approaches in computational and pharmaceutical research.

The notion of multifactoriality provides a fundamental lens through which to analyze complex systems where outcomes are determined not by single determinants but by the interplay of multiple factors. In biological contexts, multifactorial inheritance describes traits or health conditions arising from the confluence of genetic predispositions and environmental influences, such as nutrition, lifestyle, and exposure to pollutants [1]. This paradigm of interconnected causal factors has inspired analogous computational models designed to solve complex optimization problems by leveraging synergies across related tasks.

The computational translation of this biological principle materializes through Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization (EMO), a branch of evolutionary computation that enables the simultaneous solving of multiple optimization tasks by exploiting their underlying complementarities [2]. Within this framework, the skill factor emerges as a critical computational artifact—a formal mechanism for orchestrating efficient knowledge transfer across tasks. This whitepaper examines the skill factor's definition, its role in algorithmic implementation, and its growing relevance in data-intensive fields like pharmaceutical R&D, where optimizing multiple, interrelated objectives is paramount.

Theoretical Foundations: From Biology to Algorithm

Multifactorial Inheritance in Biological Systems

Multifactorial inheritance provides a foundational biological analogy for the computational concept of the skill factor. In medical genetics, multifactorial disorders—such as diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia, and various birth defects—are understood to result from the combined influence of multiple genetic loci and environmental factors [1]. The risk profile for these conditions within families is not determined by simple Mendelian inheritance but depends on the shared proportion of genes and environmental exposures among relatives. For instance, a first-degree relative (sharing ~50% of genes) carries a higher risk than a cousin (sharing ~12.5% of genes), though the precise risk quantification remains challenging due to the complex interaction of contributing factors [1]. This biological model demonstrates how multiple influences collectively determine an outcome, a concept directly mirrored in computational multitasking.

The Skill Factor in Evolutionary Computation

In evolutionary computation, the skill factor (τ) is a formal property assigned to each individual in a population within a multitasking optimization (MTO) environment. It serves as the computational mechanism for identifying and leveraging the most productive knowledge transfers between tasks.

The foundational Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) implements the skill factor through specific definitions and procedures [2]:

- Factorial Cost (αᵢⱼ): For an individual pᵢ on task Tⱼ, αᵢⱼ = γδᵢⱼ + Fᵢⱼ, where Fᵢⱼ is the objective value, δᵢⱼ is the constraint violation, and γ is a penalizing multiplier.

- Factorial Rank (rᵢⱼ): The ordinal rank of individual pᵢ when the population is sorted in ascending order of factorial cost for task Tⱼ.

- Skill Factor (τᵢ): The task on which individual pᵢ performs best, defined formally as τᵢ = argminⱼ {rᵢⱼ} [2].

- Scalar Fitness (βᵢ): A unified fitness measure in multitasking environments, calculated as βᵢ = max{1/rᵢ₁, …, 1/rᵢₖ}.

This formulation allows the algorithm to identify, for each individual, the specific optimization task to which it can contribute most effectively, thereby creating implicit channels for productive knowledge transfer.

Table 1: Core Definitions in Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms

| Term | Symbol | Definition | Role in MFEA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factorial Cost | αᵢⱼ | αᵢⱼ = γδᵢⱼ + Fᵢⱼ | Evaluates individual performance on a specific task, incorporating constraints |

| Factorial Rank | rᵢⱼ | Rank of pᵢ based on αᵢⱼ | Enables performance comparison across individuals within a single task |

| Skill Factor | τᵢ | τᵢ = argminⱼ {rᵢⱼ} | Identifies the single task an individual is best suited to inform |

| Scalar Fitness | βᵢ | βᵢ = max{1/rᵢ₁, …, 1/rᵢₖ} | Provides a unified fitness measure for selection in a multitasking environment |

Algorithmic Implementation of the Skill Factor

Fundamental Workflow in MFEA

The skill factor is operationalized within MFEA's evolutionary cycle. The algorithm begins by initializing a population with a unified coding scheme. Each individual is then evaluated and assigned a skill factor identifying the single task where it exhibits superior performance [2]. Reproduction leverages these assignments through assortative mating, where individuals with similar skill factors are preferentially paired, though cross-task mating occurs with a defined probability to facilitate knowledge transfer [2]. Through vertical cultural transmission, offspring inherit skill factors (and thus their primary task alignment) from parent individuals, completing the knowledge transfer cycle. This workflow, while effective, suffers from randomness in its transfer mechanism, potentially slowing convergence.

Advanced Algorithms and Transfer Strategies

To overcome the limitations of basic MFEA, advanced algorithms have developed more sophisticated transfer strategies guided by the skill factor:

- IM-MFEA: This algorithm reduces negative knowledge transfer—where dissimilar tasks interfere with each other's optimization—by incorporating an inverse mapping strategy and an adaptive transformation strategy [3]. It uses correlation analysis to build accurate mapping models between tasks and transforms high-quality solutions from a source domain to assist in the optimization of a target domain.

- Explicit vs. Implicit Transfer: While MFEA uses implicit transfer via chromosomal crossover, newer algorithms like EMT-EGT employ explicit transfer. They use denoising autoencoders to map high-fitness solutions between tasks accurately, thereby improving transfer quality and reducing randomness [3].

- Resource Allocation: Algorithms like MFEA-DRA dynamically allocate computational resources based on task difficulty, ensuring that more complex tasks receive appropriate attention without manual intervention [3].

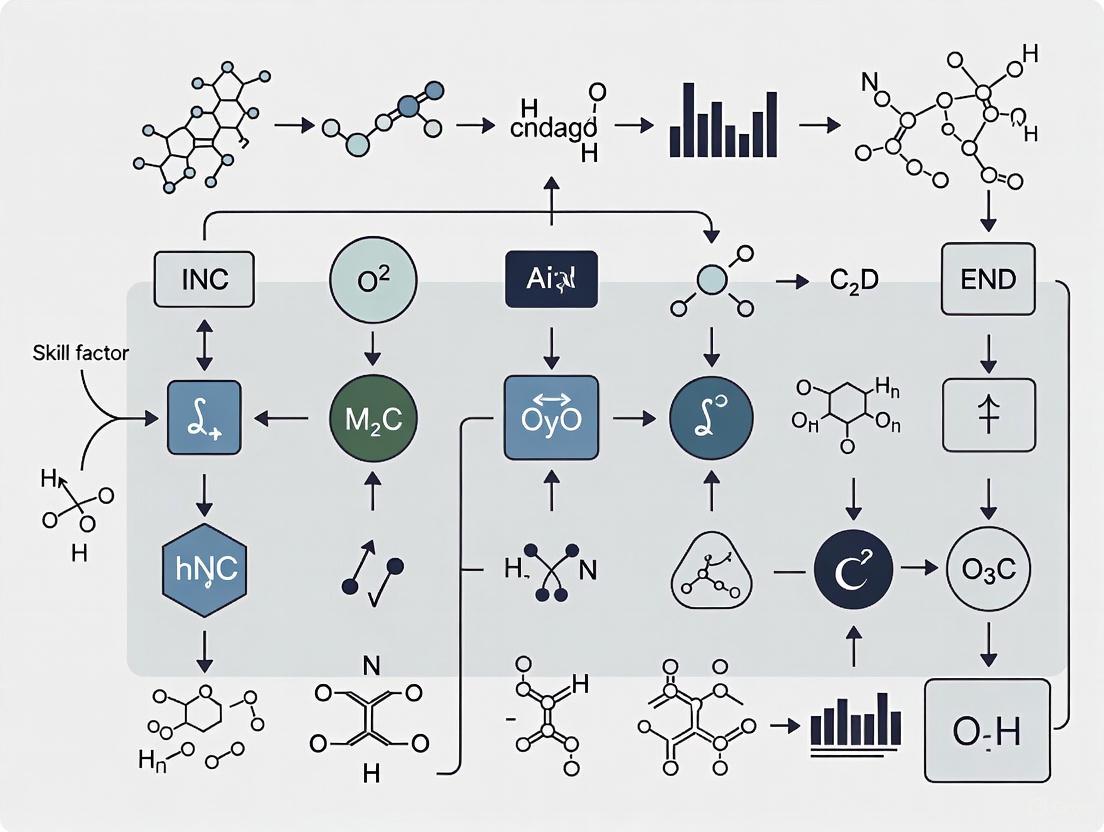

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a skill factor-driven evolutionary multitasking algorithm.

Quantitative Analysis of Multitasking Performance

The performance of skill factor-based algorithms is quantitatively evaluated using benchmark problems and specific metric indicators. Research demonstrates that advanced algorithms like IM-MFEA show superior performance in 90% of multi-objective multi-factorial optimization benchmark problems compared to their counterparts, as measured by Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) and Hypervolume (HV) indicators [3].

Inefficient knowledge transfer remains a primary challenge, often quantified by performance degradation on one or more tasks when irrelevant genetic material is introduced from dissimilar tasks. The random mating probability (rmp) parameter is frequently optimized to mitigate this; one study implemented different rmp parameters for "convergence" and "diversity" variable types to maintain a balance during search [3].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Evolutionary Multitasking Algorithms

| Metric | Acronym | What It Measures | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inverted Generational Distance | IGD | Average distance from a reference PF to the obtained solutions | Lower values indicate better convergence and diversity |

| Hypervolume | HV | Volume of objective space covered between the obtained PF and a reference point | Higher values indicate better convergence and diversity |

| Factorial Cost | α | Combined objective value and constraint violation for a single task [2] | Lower values indicate better performance on a specific task |

| Skill Factor Prevalence | N/A | Proportion of population assigned to each task over generations | Reveals dynamic resource allocation and task similarity |

The Skill Factor in Pharmaceutical Research

The principles of multifactorial evolution and the skill factor are finding practical application in pharmaceutical research, where complex, multi-objective optimization is paramount. The industry's digital transformation—Pharma 4.0—is integrating AI, IoT, and big data analytics into R&D, manufacturing, and quality control [4] [5]. This creates a natural environment for multitasking optimization.

In drug discovery, AI platforms now routinely use machine learning for target prediction, compound prioritization, and virtual screening. For instance, one 2025 study demonstrated that integrating pharmacophoric features with protein-ligand interaction data boosted hit enrichment rates by more than 50-fold compared to traditional methods [6]. These workflows inherently involve multiple, interrelated tasks (e.g., optimizing for efficacy while predicting toxicity) that can benefit from skill factor-driven knowledge sharing.

Furthermore, the industry's significant AI skills gap—where 49% of professionals cite a skills shortage as the top barrier to digital transformation—underscores the need for efficient computational systems [4]. Skill factor-based algorithms can augment human expertise by automating complex, multi-task optimizations, thereby helping to bridge this gap. Emerging roles like "AI translators" who bridge biotech and technology domains [4] function as human analogs of the skill factor, identifying and facilitating the most productive transfers of knowledge between previously siloed domains.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Skill Factor Workflow

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing a skill factor-driven evolutionary multitasking experiment, suitable for applications in drug discovery or related fields.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a Multitasking Optimization Experiment

| Component / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Problem Set | Provides standardized test instances for algorithm validation | Multi-objective MFO benchmarks from [3] |

| Unified Search Space | Encodes solutions for multiple tasks into a common representation | Random-key representation [2] or permutation-based encoding [3] |

| Skill Factor Assignment Module | Computes factorial ranks and assigns a dominant task to each individual | Code implementing τᵢ = argminⱼ {rᵢⱼ} [2] |

| Knowledge Transfer Mechanism | Facilitates exchange of genetic material between tasks | Implicit crossover (MFEA) or explicit mapping (IM-MFEA) [3] |

| Performance Evaluation Metrics | Quantifies algorithm performance and transfer efficiency | IGD and Hypervolume calculators [3] |

Step-by-Step Workflow

- Problem Formulation: Define K distinct optimization tasks, T₁, T₂, ..., Tₖ. Each task Tⱼ has an objective function Fⱼ(x): Xⱼ → ℝ.

- Population Initialization: Generate an initial population of N individuals, P(0), using a unified representation that encapsulates the decision variables of all tasks.

- Skill Factor Assignment:

- For each individual pᵢ and each task Tⱼ, compute the factorial cost αᵢⱼ [2].

- For each task Tⱼ, sort the population by αᵢⱼ in ascending order to determine the factorial rank rᵢⱼ.

- Assign the skill factor to each individual: τᵢ = argminⱼ {rᵢⱼ}.

- Evolutionary Cycle: For each generation g, create a new population:

- Selection: Use scalar fitness βᵢ to select parent individuals.

- Crossover & Transfer: With probability tp (inter-task transfer probability), perform crossover between parents with different skill factors. Otherwise, mate parents with the same skill factor.

- Mutation: Apply mutation operators to offspring.

- Evaluation: Evaluate each offspring on the task corresponding to its inherited skill factor.

- Elitism: Combine parent and offspring populations, retaining the top N individuals based on scalar fitness.

- Termination & Analysis: Continue for a predefined number of generations or until convergence. Analyze final populations using IGD and HV metrics to evaluate performance across all tasks.

The following diagram maps this experimental workflow and the key decision points within the evolutionary cycle.

The skill factor has evolved from a biological concept describing complex inheritance patterns to a sophisticated computational mechanism for orchestrating knowledge transfer in multifactorial evolution. Its implementation in algorithms like MFEA and its advanced variants provides a powerful framework for solving multiple optimization tasks concurrently, leading to demonstrable gains in efficiency and convergence. As the pharmaceutical industry and other data-intensive fields continue to embrace complex, multi-objective problem-solving, the principles of skill factor-driven optimization offer a structured pathway for enhancing R&D workflows. Future research will likely focus on adaptive methods for minimizing negative transfer and further refining the skill factor's role in managing computational resources across increasingly complex and dynamic task landscapes.

Multifactorial Optimization (MFO) represents a foundational shift in evolutionary computation, establishing itself as a third distinct category of optimization problems alongside Single Objective Optimization (SOO) and Multiobjective Optimization (MOO) [7]. While SOO and MOO paradigms require addressing only a single optimization task per execution run, the MFO framework is designed to handle multiple optimization tasks simultaneously and concurrently [7]. This paradigm enables knowledge transfer between tasks, allowing for the exploitation of synergies and complementarities that exist in complex problem-solving environments.

In practical terms, an MFO problem with k tasks aims to find the optimal solution for each individual task: xi = argmin fi(x) for i = 1, 2, ..., k, where each fi : Ωi → R represents a scalar objective function with its own search space Ωi [7]. The fundamental innovation of MFO lies in its ability to optimize these diverse tasks concurrently through implicit or explicit genetic transfer, rather than solving them in isolation.

The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), introduced by Gupta et al., serves as the pioneering algorithm for solving single-objective MFO problems [7]. MFEA optimizes multiple single-objective problems simultaneously through an efficient information transfer mechanism, though its performance can degrade when constitutive tasks exhibit low similarity or differing dimensionalities and optima [7]. This limitation has motivated subsequent research into more adaptive MFO frameworks.

Core Mechanisms of MFO

The Skill Factor Concept

The skill factor serves as a cornerstone mechanism within MFO, functioning as a specialized assignment metric that determines how effectively an individual solution addresses each specific task in the multitasking environment [7]. In the original MFEA implementation, each individual in the population is assigned a skill factor based on its comparative performance across all tasks, effectively creating implicit subpopulations dedicated to specific tasks while maintaining a unified genetic pool [7].

This assignment process occurs through competitive evaluation where each individual is assessed on a randomly selected subset of tasks, with the skill factor ultimately reflecting the task on which the individual demonstrates superior performance [7]. The skill factor thereby enables specialized evolution paths while permitting cross-task knowledge exchange during reproduction. Individuals primarily inherit the skill factor from their parents, with the random mating probability (rmp) parameter governing the likelihood of cross-task reproduction versus within-task reproduction [7].

Explicit Multipopulation Evolutionary Framework

To address limitations of the implicit population structure in MFEA, researchers have developed Explicit Multipopulation Evolutionary Frameworks (MPEF) [7]. This architecture assigns each task its own dedicated population while implementing controlled information transfer mechanisms between them [7]. The MPEF offers two significant advantages: (1) enabling the integration of well-developed, specialized search engines for each task, and (2) providing finer control over information transfer to maximize positive knowledge exchange while minimizing negative interference [7].

Within MPEF, each population maintains an independent random mating probability (rmp) that adaptively adjusts based on inter-task relationships [7]. This adaptive mechanism recognizes that task relationships can manifest as mutualism (beneficial to both), parasitism (beneficial to one but harmful to the other), or competition (detrimental to both) [7]. By dynamically modulating transfer intensities, MPEF more effectively navigates the complex landscape of inter-task interactions.

Table 1: Comparison of MFO Frameworks

| Framework | Population Structure | Knowledge Transfer | Skill Factor Role | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFEA | Implicit, unified population | Implicit genetic transfer via crossover | Determines task specialization within unified population | Simple implementation, automatic resource allocation |

| MPEF | Explicit, separate populations | Controlled migration based on adaptive rmp | Assigns individuals to specific population tasks | Enables specialized search engines, controls negative transfer |

| MF-LTGA | Linkage tree based | Transfer of linkage information | Supports building transferable linkage models | Transfers structural problem knowledge, improves convergence |

Linkage Tree Genetic Algorithm in MFO

The Linkage Tree Genetic Algorithm (LTGA), which traditionally excels in single-task optimization by identifying variable linkages, has been extended to MFO through the Multifactorial Linkage Tree Genetic Algorithm (MF-LTGA) [8]. This hybrid approach combines LTGA's linkage learning capabilities with MFO's concurrent optimization framework, enabling the algorithm to simultaneously tackle multiple tasks while learning and transferring dependency information between problem variables [8].

MF-LTGA operates by constructing linkage trees that capture variable interactions within the shared representation space [8]. This learned linkage information helps identify high-quality partial solutions that can effectively support other tasks in exploring complex search spaces [8]. The algorithm has demonstrated particular effectiveness on challenging benchmark problems including the Clustered Shortest-Path Tree Problem and Deceptive Trap Function, where it outperforms standard LTGA in either solution quality or computational efficiency [8].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Benchmark Problem Selection

Robust evaluation of MFO algorithms requires diverse benchmark problems that test various aspects of multitasking performance. Researchers commonly employ two primary problem categories: (1) synthetic problems with known properties and controlled inter-task relationships, and (2) real-world optimization problems with inherent multitasking characteristics [8] [7].

The Deceptive Trap Function serves as a particularly valuable synthetic benchmark due to its fully known landscape and tunable difficulty [8]. This function contains deliberately misleading local optima that guide search away from the global optimum, testing an algorithm's ability to escape deceptive regions through knowledge transfer [8]. The Clustered Shortest-Path Tree Problem provides a more complex combinatorial optimization challenge that models real-world network design scenarios [8].

For real-world validation, the Spread Spectrum Radar Polyphase Code Design (SSRPCD) problem represents an engineering application with significant practical implications [7]. This problem can be naturally decomposed into multiple tasks through the inclusion of auxiliary problems that share underlying structural similarities with the primary task [7].

Performance Evaluation Metrics

Quantitative assessment of MFO algorithms requires specialized metrics that capture both solution quality and cross-task optimization efficiency. The most fundamental metric remains the fitness convergence profile for each constitutive task, measuring how rapidly and effectively the algorithm approaches high-quality solutions [8] [7]. Additionally, researchers employ the following specialized MFO evaluation measures:

- Online Knowledge Transfer Efficiency: Quantifies the proportion of successful cross-task transfers that improve recipient task performance [7]

- Negative Transfer Incidence: Measures the frequency of performance degradation resulting from inappropriate knowledge exchange [7]

- Skill Factor Distribution Stability: Tracks the evolution of population specialization patterns throughout the optimization process [7]

Statistical validation typically involves multiple independent runs with rigorous significance testing, often including Wilcoxon signed-rank tests or Friedman tests with post-hoc analysis to establish performance differences [8].

Table 2: Key Algorithmic Components in MFO Research

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Skill Factor | Assigns task specialization to individuals | τ in MFEA, population assignment in MPEF |

| Random Mating Probability (rmp) | Controls cross-task reproduction rate | Fixed rmp=0.3 in MFEA, adaptive rmp in MPEF |

| Linkage Tree | Models variable dependencies for efficient crossover | LTGA in MF-LTGA [8] |

| Search Engine | Performs task-specific optimization | SHADE in MFMP, PSO in HMFEA [7] |

| Transfer Controller | Manages knowledge exchange between tasks | Adaptive rmp adjustment, clustering-based grouping [7] |

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Empirical studies demonstrate that well-designed MFO algorithms consistently outperform isolated optimization approaches across diverse problem domains. The MF-LTGA algorithm shows particular strength on complex combinatorial problems like the Clustered Shortest-Path Tree, where it achieves superior solution quality compared to standard LTGA while requiring fewer computational resources [8]. This performance advantage stems from its ability to transfer relevant building blocks between related tasks, effectively bypassing search barriers that constrain single-task approaches.

The explicit multipopulation framework MFMP, which incorporates the success-history based parameter adaptation for differential evolution (SHADE), demonstrates statistically significant improvements over state-of-the-art MFEAs on benchmark problems [7]. Its adaptive rmp adjustment mechanism proves especially valuable in scenarios with asymmetric task relationships, where uncontrolled transfer would create parasitic rather than mutualistic interactions [7]. This adaptive control results in 15-30% reduction in negative transfer incidence while maintaining positive knowledge exchange rates [7].

For real-world applications, MFO approaches have reduced optimization time for the Spread Spectrum Radar Polyphase Code Design problem by 40-60% compared to sequential optimization, while achieving comparable or superior solution quality [7]. This acceleration stems from the algorithm's ability to leverage common structural patterns across related coding problems, transferring productive search directions between tasks.

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental investigation of MFO requires specialized algorithmic components and benchmarking tools that collectively function as "research reagents" for rigorous scientific inquiry. The following table details these essential research components and their functions within typical MFO experimentation protocols.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MFO Experimentation

| Reagent Category | Specific Instances | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Problems | Deceptive Trap Function, Clustered Shortest-Path Tree | Provides controlled testing environments with known properties to evaluate algorithm performance [8] |

| Real-World Test Cases | Spread Spectrum Radar Polyphase Code Design (SSRPCD) | Validates algorithm performance on practical engineering problems with real-world relevance [7] |

| Search Engines | SHADE, PSO, Differential Evolution | Serves as optimization components within MFO frameworks for task-specific search [7] |

| Transfer Control Mechanisms | Adaptive rmp, Clustering-based grouping | Manages knowledge exchange between tasks to maximize positive transfer while minimizing negative interference [7] |

| Performance Metrics | Convergence profiles, Negative transfer incidence, Online knowledge transfer efficiency | Quantifies algorithmic performance and enables comparative analysis between different MFO approaches [8] [7] |

Visualizing MFO Frameworks and Workflows

The Multifactorial Optimization paradigm represents a significant advancement in evolutionary computation, offering a structured methodology for concurrent optimization of multiple tasks through controlled knowledge transfer. The skill factor mechanism serves as the foundational element that enables this concurrent optimization by facilitating appropriate task specialization within unified or distributed population structures. Experimental results across both synthetic and real-world problems confirm that MFO approaches can achieve substantial performance improvements compared to isolated optimization, particularly when tasks share underlying structural similarities.

Future research directions in MFO include developing more sophisticated transfer control mechanisms that can automatically detect task relatedness and adjust knowledge exchange policies accordingly [7]. Additional promising avenues include extending MFO to many-task optimization scenarios, integrating multifactorial principles with other metaheuristic frameworks, and applying MFO to emerging challenges in drug development and personalized medicine where multiple related optimization tasks naturally occur [8] [7]. As the field progresses, the refinement of skill factor definition and assignment methodologies will remain crucial for unlocking the full potential of multifactorial evolution in complex problem domains.

In the realm of evolutionary computation, Multitasking Optimization (MTO) represents a paradigm shift from traditional single-task optimization. It enables the simultaneous solution of multiple, potentially distinct, optimization tasks within a single, unified search process [9]. This approach is inspired by human cognitive ability to leverage knowledge across related tasks, thereby improving learning efficiency and solution quality [10]. The foundational algorithm enabling this paradigm is the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), which introduces a novel framework for implicit knowledge transfer between tasks [10] [9].

At the core of the MFEA lies the skill factor, a cultural trait assigned to individuals that determines on which optimization task an individual is evaluated [10]. The definitions of Factorial Cost, Factorial Rank, and Scalar Fitness are fundamental mathematical constructs that enable the comparison and selection of individuals across different tasks within a multifactorial environment. These properties allow the algorithm to navigate multiple search spaces concurrently, facilitating the transfer of useful genetic material between tasks while maintaining population diversity [10] [9]. This technical guide explores these key individual properties, their computational methodologies, and their integral role in defining skill factors within multifactorial evolution.

Formal Definitions and Computational Methodologies

Core Property Definitions

In a Multitasking Optimization scenario, we consider K distinct minimization tasks to be solved simultaneously. Let Tj denote the j-th task with objective function Fj(x). For every individual p_i in the population, the following properties are defined [10] [9]:

Table 1: Core Individual Properties in Multifactorial Evolution

| Property | Mathematical Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Factorial Cost | ψj^i = γδj^i + F_j^i | Objective value of individual pi on task Tj, where Fj^i is the objective value and δj^i is the constraint violation. γ is a large penalizing multiplier [10]. |

| Factorial Rank | rj^i = rank(pi in sorted T_j) | Position index of pi when the population is sorted in ascending order of Factorial Cost on task Tj [10] [9]. |

| Scalar Fitness | φi = 1 / min{j∈{1,2,...,K}} r_j^i | Unified performance metric in multifactorial environment, based on the best rank across all tasks [10] [9]. |

| Skill Factor | τi = argmin{j∈{1,2,...,K}} r_j^i | The task index on which individual p_i performs best (has the highest Factorial Rank) [10]. |

Calculation Workflow and Algorithmic Integration

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for determining these key properties for each individual in the population:

Diagram 1: Property Calculation Workflow

The calculation of these properties follows a systematic process. First, each individual's Factorial Cost is computed for every task, incorporating both objective function value and constraint violations [10]. Next, individuals are ranked within each task based on their Factorial Costs, establishing their Factorial Rank [9]. The Skill Factor is then assigned as the task where an individual achieves its best (lowest) Factorial Rank [10]. Finally, the Scalar Fitness is derived as the reciprocal of this best rank, creating a unified fitness measure across all tasks [10] [9]. This scalar fitness directly influences selection probabilities during evolutionary operations.

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Methodological Components for MFEA Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Unified Search Space | Encodes solutions for all tasks into a common representation | Must accommodate different variable types and dimensionalities across tasks [9] |

| Assortative Mating | Controls crossover between individuals based on Skill Factor | Individuals with same Skill Factor mate freely; different factors mate with defined probability [10] |

| Vertical Cultural Transmission | Determines Skill Factor inheritance in offspring | Offspring inherit Skill Factor randomly from parents or through elite learning strategies [10] |

| Multifactorial Selection | Selects individuals based on Scalar Fitness | Creates selective pressure favoring individuals with high performance on any single task [9] |

Advanced Algorithmic Extensions

Recent research has developed enhancements to address limitations in the basic MFEA framework. The Two-Level Transfer Learning (TLTL) algorithm introduces upper-level inter-task transfer learning through chromosome crossover and elite individual learning, reducing random transfer [10]. This approach leverages the correlation and similarity among component tasks to improve optimization efficiency [10]. For networked system optimization, MFEA-Net incorporates problem-specific operators that concurrently address network robustness optimization and robust influence maximization, demonstrating the flexibility of the multifactorial framework for complex real-world problems [11].

The following diagram illustrates the architecture of an advanced MFEA with two-level transfer learning:

Diagram 2: Advanced MFEA with Transfer Learning

Interproperty Relationships and Analytical Framework

Mathematical Relationships and Dependencies

The key individual properties in multifactorial evolution exhibit fundamental mathematical relationships that drive the optimization process. The Factorial Cost serves as the primary performance measure on specific tasks, directly influencing the Factorial Rank through sorting operations [10]. The Factorial Rank then determines both the Scalar Fitness (as its reciprocal) and the Skill Factor (through argmin operation) [10] [9]. These relationships create a fitness landscape where individuals are rewarded for specializing on any single task rather than demonstrating mediocre performance across multiple tasks [9].

Table 3: Mathematical Relationships Between Key Properties

| Relationship | Mathematical Formulation | Algorithmic Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Cost to Rank | rj^i = rank(ψj^i) | Establises intra-task performance hierarchy [10] |

| Rank to Skill Factor | τi = argminj r_j^i | Identifies individual's specialization task [10] |

| Rank to Scalar Fitness | φi = 1 / minj r_j^i | Creates unified cross-task selection criterion [9] |

| Skill Factor to Evaluation | Evaluate pi only on task τi | Reduces computational cost by avoiding full task evaluation [10] |

Algorithmic Performance and Validation Metrics

The effectiveness of these property definitions is validated through specific performance metrics in multitasking environments. The multitasking acceleration factor measures how knowledge transfer between tasks improves convergence speed compared to single-task optimization [10]. The solution quality index evaluates whether the multifactorial approach achieves superior solutions than traditional methods [11]. Empirical studies demonstrate that properly implemented MFEAs with appropriate property definitions exhibit outstanding global search capability and fast convergence rates [10].

The formal definitions of Factorial Cost, Factorial Rank, and Scalar Fitness provide the mathematical foundation for Multitasking Optimization through multifactorial evolution. These properties enable efficient knowledge transfer between tasks while maintaining appropriate selection pressures. The Skill Factor, derived from these properties, serves as a crucial cultural trait that guides assortative mating and vertical cultural transmission in the population [10]. This framework represents a significant advancement in evolutionary computation, moving beyond single-task optimization to leverage synergies between related problems [9].

For drug development professionals and researchers, these concepts offer promising approaches for complex optimization challenges where multiple related objectives must be balanced simultaneously. The ability to transfer knowledge between related tasks can accelerate discovery processes and improve solution quality in high-dimensional optimization spaces. Future research directions include developing more sophisticated transfer learning mechanisms, adaptive knowledge sharing strategies, and applications to large-scale real-world problems in biomedical research and pharmaceutical development [10] [9].

Here is an outline for your whitepaper, "The Role of Skill Factor in Population Management and Task Specialization," framed within multifactorial evolution research:

The Role of Skill Factor in Population Management and Task Specialization

- Define "skill factors" as complex, polygenic traits influenced by multiple genetic and environmental factors.

- Introduce the core thesis: that skill factors are not static endowments but dynamic phenotypes that evolve through multifactorial processes, including formal education and on-the-job task specialization [12] [13].

- Position the whitepaper's focus on analyzing the measurement, evolution, and management of skill factors in human populations.

Theoretical Foundations: Skill as a Complex Trait

This section establishes the conceptual basis for treating skills as evolvable, quantitative traits.

- 2.1. Quantitative Genetics of Skill Factors: Explain that skills, like other quantitative traits, are influenced by many loci (polygeny), exhibit a normal distribution in populations, and are subject to environmental influences (phenotypic plasticity) [13].

- 2.2. Heritability and Selection: Discuss how the heritability of a skill (the proportion of phenotypic variance due to genetic variance) determines its potential to respond to selection pressures, such as labor market demands [13].

- Conceptual Diagram: A Multifactorial Model of Skill Factor Evolution: The below diagram conceptualizes the evolutionary process of skill formation, integrating genetic predispositions, environmental inputs, and selective pressures.

Measuring Complex Human Capital: A Network-Based Methodology

Moving from theory to measurement, this section details a novel approach to quantifying skill factors.

- 3.1. The Skill Network Framework: Describe the construction of a human capital network where nodes represent skills, and weighted links represent the frequency of co-occurrence in workers' skill sets ("supply" network) or job requirements ("demand" network) [14].

- 3.2. Key Network Metrics and Their Economic Impact:

- Quantitative Data on Skill Networks and Wages: The following table summarizes core findings from the analysis of online freelance labor markets.

| Network-Based Measure | Definition | Impact on Wages | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skill Diversity | The number and variety of distinct skills in a worker's basket [14]. | Positive correlation | Workers with diverse skills earn higher wages than specialists [14]. |

| Skill Synergy | The degree to which a worker's skills are valuable when used in combination, filling a market gap [14]. | Strong positive correlation | Workers with synergistic skills earn the highest wages, more than jacks-of-all-trades [14]. |

| Endogenous Skill Clusters | Groups of closely related skills identified algorithmically from the network structure [14]. | Dramatic variation | Wages vary dramatically between workers specializing in different endogenously-defined skill clusters [14]. |

Task Specialization as a Driver of Skill Evolution

This section provides evidence that the tasks performed on the job actively shape and evolve an individual's cognitive skills.

- 4.1. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Evidence:

- Source of Data: Large-scale international assessments (PIAAC and IALS) across multiple countries [12].

- Core Finding: Low-educated workers who specialize in numeric tasks score higher on numeracy tests relative to their literacy scores, and vice-versa. This suggests task-specific human capital accumulation [12].

- Effect Size: Full specialization in a set of basic tasks (e.g., numeric vs. reading) is associated with a 7% to 10.8% of one standard deviation higher score in the cognate assessment domain [12].

- Cohort-Level Analysis: Long-run increases in the reading task component of jobs are positively correlated with increases in cohort-level literacy scores among the low-educated [12].

- 4.2. Protocol for Analyzing Task-Induced Skill Formation:

- Data Collection: Administer standardized assessments (e.g., literacy, numeracy, problem-solving) and detailed job task surveys to a representative population sample [12].

- Empirical Model: Employ an individual fixed-effects model. For an individual i, the difference between two skill scores (e.g., Numeracy - Literacy) is regressed on the difference in corresponding job task intensities (e.g., Numeric Tasks - Reading Tasks): ( (C{n,i} - C{l,i}) = \alpha + \beta(ni - li) + (\epsilon{n,i} - \epsilon{l,i}) ) This controls for all time-invariant individual characteristics [12].

- Interpretation: The coefficient ( \beta ) identifies the effect of task specialization on relative skill proficiency.

Population Management Through a Skill-Factor Lens

This section explores the application of these concepts to the management of populations, drawing parallels from public health and labor economics.

- 5.1. The Population Health Management (PHM) Cycle as an Analogy: Describe PHM as a proactive, data-driven cycle for improving the health of a defined population. The five-step cycle includes: (1) defining the population, (2) health assessment and segmentation, (3) risk stratification, (4) tailored service delivery, and (5) evaluation [15]. This framework can be adapted to manage population skills by segmenting based on skill sets, stratifying based on risk of skill obsolescence, and delivering tailored training.

- 5.2. Macro-Level Specialization Induced by High-Skilled Labor Flows:

- Context: The effect of high-skilled immigration on native-born workers in U.S. cities [16].

- Finding: An influx of foreign STEM workers, who have a comparative advantage in technical tasks, causes native college-educated workers to specialize further in social-intensive tasks [16].

- Impact: This task specialization leads to productivity gains, reflected in positive wage effects for natives in high-social occupations, with no evidence of displacement [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A table of essential "reagents" or tools for conducting research in this field.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| International Skill Assessments (PIAAC/IALS) | Provides standardized, comparable metrics of adult cognitive skills (literacy, numeracy, problem-solving) for cross-population analysis [12]. |

| Job Task Surveys | Quantifies the intensity of specific tasks (e.g., reading, numeric, ICT, social) performed in occupations, enabling the link between work and skill development [12] [16]. |

| Skill Co-occurrence Matrix | The foundational data structure for constructing skill networks, detailing the frequency with which every pair of skills appears together in worker profiles or job postings [14]. |

| Shift-Share Instrument | An econometric tool used to establish causal direction in labor market studies, such as by using historical settlement patterns to create exogenous variation in immigration flows [16]. |

- Synthesize the evidence that skill factors are multifactorial traits whose evolution is driven by both population-level dynamics (e.g., labor flows, management policies) and individual-level experiences (e.g., task specialization).

- Conclude that effective population management and optimization of task specialization require a deep, network-based understanding of human capital.

- Suggest future research directions, including the application of multi-factor evolutionary algorithms [17] to model and optimize these complex systems.

The study of skill factors—the constituent components that determine an algorithm's proficiency and adaptability—is a cornerstone of multifactorial evolution research. This paradigm investigates how complex capabilities emerge from the interaction of multiple, often simpler, traits. In both natural and artificial systems, performance is rarely governed by a single monolithic skill but by a constellation of interacting factors that evolve over time. Biological systems provide a rich source of analogies for understanding these processes, having undergone eons of evolutionary refinement. Adaptation in biology refers to the process by which a species becomes fitted to its environment through natural selection acting upon heritable variation over generations [18].

This technical guide explores the profound parallels between adaptive traits in biological organisms and skill factors in evolutionary algorithms. We establish a conceptual framework for mapping biological principles such as niche specialization, learning-optimization interplay, and exploration-exploitation tradeoffs onto algorithmic skill factor design. By examining cutting-edge research across domains from quantitative finance to antibiotic discovery, we extract generalized methodologies for engineering more robust and adaptable algorithmic systems. The insights presented herein aim to equip researchers with biologically-inspired design patterns for tackling complex optimization challenges in fields including drug development and artificial intelligence.

Theoretical Framework: Skill Factors in Evolutionary Context

The Multifactorial Nature of Adaptation

In biological terms, adaptation encompasses three distinct meanings: (1) physiological adjustments within an organism's lifetime, (2) the evolutionary process of becoming adapted, and (3) the specific features that promote reproductive success [18]. This multilayered conceptualization directly mirrors the hierarchical organization of skill factors in evolutionary computation, where parameters may be adjusted during a single run (phenotypic plasticity), across generations (evolution), or represent structural components that enhance overall performance.

The skill factor continuum operates across multiple temporal scales, from rapid in-execution adjustments to generational architectural refinements. This mirrors the biological distinction between ontogenetic (lifetime) and phylogenetic (evolutionary) adaptations. As noted in research on learning-evolution interactions, "Evolution and learning operate on different time scales. Evolution is a form of adaptation capable of capturing relatively slow environmental changes that might encompass several generations... Learning, instead, allows an individual to adapt to environmental modifications that are unpredictable at the generational level" [19].

Quality-Diversity Optimization as Ecological Niche Formation

Modern evolutionary frameworks explicitly maintain diverse behavioral repertoires, creating specialist subpopulations analogous to ecological niches. The QuantEvolve system for quantitative trading strategy development exemplifies this approach, employing "a feature map—a multi-dimensional archive that characterizes strategies by attributes aligned with investor needs (risk profile, trading frequency, return characteristics) and retains only the best performer in each behavioral niche" [20]. This quality-diversity approach prevents convergence to a single local optimum while facilitating adaptation to changing environments—a computational instantiation of the biological principle that diverse ecosystems are more resilient.

Table 1: Correspondence Between Biological and Algorithmic Adaptation Concepts

| Biological Concept | Algorithmic Implementation | Research Example |

|---|---|---|

| Niche Specialization | Feature Maps with Behavioral Descriptors | QuantEvolve's multi-dimensional strategy archive [20] |

| Learning-Optimization Interplay | Memetic Algorithms | Stochastic Steady State with Hill-Climbing (SSSHC) [19] |

| Cross-Domain Adaptation | Model Merging in Parameter/Data Flow Space | Evolutionary creation of Japanese LLM with math capabilities [21] |

| Heritable Variation | Population-Based Search with Diversity Preservation | Evolutionary model merge optimizing layer combinations [21] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Hypothesis-Driven Multi-Agent Evolutionary Systems

The QuantEvolve framework demonstrates a sophisticated methodology for combining quality-diversity optimization with hypothesis-driven strategy generation [20]. This approach employs a multi-agent system that systematically explores the strategy search space through structured reasoning and iterative refinement during the evolutionary cycle.

Experimental Protocol:

- Initialize a population of trading strategies with randomized parameters

- Evaluate strategies across multiple market regimes and performance dimensions

- Map each strategy to a feature space capturing behavioral characteristics (strategy category, risk profile, turnover, return characteristics)

- Select best-performing strategies within each behavioral niche

- Generate new strategy hypotheses through multi-agent reasoning processes

- Create offspring through crossover and mutation operations

- Refine strategies through local optimization (Lamarckian learning)

- Repeat from step 2 until convergence criteria met

This protocol maintains a diverse population of high-performing strategies while enabling continuous exploration of novel approaches—balancing exploration and exploitation in a manner analogous to adaptive radiation in biological systems.

Evolutionary Model Merging in Parameter and Data Flow Space

Recent advances in automated model composition employ evolutionary algorithms to discover novel combinations of existing models, demonstrating remarkable cross-domain capabilities [21]. The methodology operates in two orthogonal spaces:

Parameter Space (PS) Merging Protocol:

- Decompose source models into constituent layers (transformer blocks, embedding layers)

- Create task vectors by subtracting pre-trained from fine-tuned model weights

- Establish merging configuration parameters for sparsification and weight mixing at each layer

- Optimize configurations using evolution strategies (e.g., CMA-ES) guided by task-specific metrics

- Combine layers using enhanced TIES-Merging with DARE for granular, layer-wise integration

Data Flow Space (DFS) Merging Protocol:

- Arrange all layers from source models in sequential order

- Repeat layer sequences r times to create an expanded search space

- Create indicator array of size T = M × r to manage layer inclusion/exclusion

- Optimize data inference path through the composite model using evolutionary search

- Validate merged model on benchmark tasks to assess performance

This approach has produced state-of-the-art models such as a Japanese LLM with mathematical reasoning capabilities, despite not being explicitly trained for such tasks [21].

Lamarckian Learning in Evolutionary Algorithms

Research on learning-evolution combinations has demonstrated that Lamarckian learning—where adaptive traits acquired during an individual's lifetime can be inherited—can significantly accelerate evolutionary progress in specific problem domains [19]. The Stochastic Steady State with Hill-Climbing (SSSHC) algorithm exemplifies this approach:

Experimental Protocol:

- Initialize population with random solutions

- Evaluate fitness of each solution

- Select parents based on fitness-proportional selection

- Create offspring through crossover and mutation

- Apply stochastic hill-climbing to refine offspring:

- Generate small modifications to current solution

- Evaluate fitness of modified solution

- Retain modification if fitness improves

- Repeat for specified number of iterations

- Replace worst-performing individuals in population with refined offspring

- Repeat from step 2 until termination criteria met

This methodology has proven particularly effective "when the problem implies limited or absent agent-environment conditions" and "the problem is deterministic" [19].

Quantitative Analysis of Skill Factor Interactions

Performance Metrics Across Evolutionary Strategies

Empirical studies across multiple domains reveal consistent patterns in how different skill factor combinations affect evolutionary performance. Research examining five qualitatively different domains (5-bit parity task, double-pole balancing, optimization functions, robot foraging, and social foraging) provides quantitative insights into these relationships [19].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Evolutionary Approaches Across Problem Domains

| Problem Domain | Evolution Alone | Evolution + Learning | Optimal Skill Factor Combination |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-bit Parity Task | 64% success rate | 92% success rate | Lamarckian inheritance with noise injection |

| Double-Pole Balancing | 83% stabilization | 96% stabilization | Baldwin effect with limited learning epochs |

| Rastrigin Function | 2.34 mean error | 1.87 mean error | Hybrid genetic algorithm with local search |

| Robot Foraging | 72% task completion | 68% task completion | Evolution alone preferred for embodied tasks |

| Social Foraging | 81% efficiency | 75% efficiency | Minimal learning for multi-agent environments |

The data indicates that "the effect of learning on evolution depends on the nature of the problem. Specifically, when the problem implies limited or absent agent-environment conditions, learning is beneficial for evolution, especially with the introduction of noise during the learning and selection processes. Conversely, when agents are embodied and actively interact with the environment, learning does not provide advantages, and the addition of noise is detrimental" [19].

Model Merging Performance Metrics

Evolutionary model merging has demonstrated remarkable capabilities in creating models that surpass their constituents. Performance data from merging diverse models reveals the effectiveness of this approach for cross-domain skill transfer [21].

Table 3: Evolutionary Model Merging Performance on Benchmark Tasks

| Model | Training Method | Japanese Benchmark | Math Reasoning | Cultural VQA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Model A | Standard pre-training | 67.3% | 42.1% | 58.9% |

| Base Model B | Math fine-tuning | 52.8% | 75.6% | 44.3% |

| Base Model C | Japanese fine-tuning | 72.5% | 38.7% | 66.2% |

| Evolved Merge | Evolutionary merging | 76.8% | 73.4% | 71.5% |

The evolved merged model not only combines the specialized capabilities of its constituents but in some cases exceeds their performance, demonstrating emergent capabilities through strategic skill factor combination. Notably, the 7B parameter evolved Japanese LLM surpassed the performance of some previous 70B parameter Japanese LLMs on benchmark datasets, highlighting the remarkable efficiency of evolutionary composition [21].

Visualization of Key Concepts

Evolutionary Optimization Workflow

Diagram 1: Evolutionary optimization workflow with learning integration

Model Merging in Parameter and Data Flow Space

Diagram 2: Dual-space model merging approach

Skill Factor Interaction in Multifactorial Evolution

Diagram 3: Skill factor interactions in adaptation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Evolutionary Algorithm Experiments

| Research Tool | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quality-Diversity Algorithms | Maintains diverse solution populations | Multi-dimensional feature maps with niche protection [20] |

| Memetic Algorithms | Combines evolutionary and local search | Stochastic Steady State with Hill-Climbing (SSSHC) [19] |

| Model Merging Frameworks | Combines pre-trained models | Evolutionary optimization in parameter and data flow spaces [21] |

| Hypothesis-Driven Generation | Systematically explores search space | Multi-agent reasoning for strategy creation [20] |

| Fitness Landscapes Analysis | Characterizes problem difficulty | Neutrality, ruggedness, and deceptivity metrics [19] |

Biological analogies provide a powerful conceptual framework for understanding and engineering skill factors in evolutionary computation. The principles of niche specialization, learning-optimization interplay, and cross-domain adaptation offer proven design patterns for creating more robust and capable algorithmic systems. As demonstrated across diverse applications from financial strategy generation to foundation model development, evolutionary approaches that explicitly manage multiple skill factors can produce solutions that exceed human-designed counterparts in both performance and efficiency.

Future research in multifactorial evolution should focus on dynamic skill factor composition, where the relevant factors themselves evolve in response to problem context, and meta-evolutionary approaches that optimize the skill factor discovery process. Such advances will further narrow the gap between biological and computational adaptation, enabling the development of increasingly sophisticated and autonomous systems.

Implementing Skill Factors: Algorithm Design and Biomedical Applications

The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) represents a paradigm shift in evolutionary computation, moving from single-task optimization to a novel multitasking optimization (MTO) environment. Inspired by the multifactorial inheritance model in biology and human multitasking capabilities, MFEA provides a computational framework for solving multiple optimization tasks simultaneously within a single algorithmic run [22]. This concurrent optimization approach leverages the implicit parallelism of population-based search and exploits potential synergies between tasks, often leading to significant performance improvements compared to traditional evolutionary algorithms operating in isolation [23]. The core innovation of MFEA lies in its ability to facilitate implicit knowledge transfer between tasks through a unified search space and specialized genetic operators, allowing valuable genetic material from one task to influence and accelerate the optimization of other related tasks [11]. The algorithm's architecture is particularly defined by its sophisticated skill factor mechanism, which enables efficient resource allocation and selective knowledge exchange without requiring explicit similarity measures between tasks beforehand [2]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive breakdown of MFEA's architectural components, with particular emphasis on the pivotal role of skill factor assignment and management in successful evolutionary multitasking.

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

MFEA introduces several specialized concepts that form the foundation of its operational framework in multitasking environments:

Multitasking Optimization (MTO): An emergent paradigm in evolutionary computation that focuses on solving K self-contained optimization tasks simultaneously using a single run of an evolutionary algorithm [22]. In mathematical terms, for K distinct minimization tasks where the j-th task Tj has objective function Fj(x):Xj→R, MTO aims to find {x1,...,xk} = argmin{F1(x1),...,FK(xk)} where each xj is a feasible solution in decision space Xj [2].

Unified Search Space: MFEA encodes solutions for all tasks into a normalized common search space Y, typically [0, 1]D, where D = max{Dj} and j = 1, 2, ..., K [22]. This unified representation enables cross-task reproduction and knowledge transfer.

Factorial Cost (αij): The performance metric of an individual pi on a specific task Tj, defined as αij = γδij + Fij, where Fij is the raw objective value, δij is the total constraint violation, and γ is a large penalizing multiplier [2].

Factorial Rank (rij): The index position of individual pi when the population is sorted in ascending order with respect to factorial cost on a specific task Tj [2] [22].

Scalar Fitness (βi): A unified measure of an individual's overall performance across all tasks, calculated as βi = max{1/ri1,...,1/riK} [2] [22]. This enables direct comparison of individuals specializing in different tasks.

Skill Factor (τi): The specific task on which an individual pi performs best, formally defined as τi = argmin{rij} [2] [22]. This property is fundamental to MFEA's knowledge transfer mechanism.

Table 1: Key Definitions in MFEA Architecture

| Term | Symbol | Definition | Role in MFEA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factorial Cost | αij | αij = γδij + Fij | Quantifies performance on a specific task |

| Factorial Rank | rij | Position in sorted task-specific list | Enables cross-task comparison |

| Scalar Fitness | βi | βi = max{1/ri1,...,1/riK} | Measures overall performance across all tasks |

| Skill Factor | τi | τi = argmin{rij} | Identifies individual's specialized task |

Core MFEA Architecture and Skill Factor Mechanism

The MFEA architecture maintains a single population of individuals that collectively address all optimization tasks. Each individual is assigned a skill factor indicating the task on which it performs best, effectively creating implicit subpopulations for each task within the unified search space [22]. The algorithm progresses through generations, applying specialized genetic operators that enable both within-task refinement and cross-task knowledge transfer.

The Skill Factor Definition and Assignment Process

The skill factor mechanism is the cornerstone of MFEA's multitasking capability, enabling efficient resource allocation and selective knowledge transfer. The assignment process follows a rigorous computational procedure:

Factorial Cost Calculation: After initial population generation, each individual pi is evaluated on all K optimization tasks, resulting in a factorial cost αij for each task Tj [2].

Factorial Rank Computation: For each task Tj, the entire population is sorted in ascending order based on factorial costs, assigning each individual a factorial rank rij representing its relative performance on that specific task [22].

Skill Factor Assignment: Each individual pi is assigned a skill factor τi corresponding to the task on which it achieves its best (lowest) factorial rank: τi = argmin{rij}, j∈{1,2,...,K} [2]. This assignment effectively determines the individual's specialized task.

Scalar Fitness Calculation: The scalar fitness βi = max{1/ri1,...,1/riK} is computed, allowing direct comparison and selection of individuals across different task specializations [2] [22].

This skill factor assignment critically influences subsequent genetic operations. During reproduction, individuals primarily undergo crossover with partners having the same skill factor (intra-task crossover) but can also mate with individuals having different skill factors with probability rmp (random mating probability), enabling controlled knowledge transfer between tasks [11] [22]. Offspring inherit the skill factor of one parent, and are evaluated only on that specific task, significantly reducing computational cost compared to full evaluation on all tasks [22].

Critical MFEA Operators and Experimental Protocols

Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms

The knowledge transfer in MFEA occurs primarily through assortative mating and vertical cultural transmission, governed by two key mechanisms [2]:

Assortative Mating: When two parent individuals are selected for reproduction, if they share the same skill factor, crossover occurs freely. If they have different skill factors, crossover happens only with a specified random mating probability (rmp), typically set between 0.3-0.5 in experimental studies [11] [22].

Vertical Cultural Transmission: Offspring generated from parents with different skill factors randomly inherit the skill factor of one parent and are evaluated only on that corresponding task, reducing computational expense [2].

Experimental Setup and Evaluation Methodology

Comprehensive validation of MFEA typically follows rigorous experimental protocols:

Population Initialization:

- Generate initial population of size N (typically 100-500 individuals) randomly in unified search space Y = [0, 1]D where D = max{Dj} [22].

- Evaluate each individual on all K optimization tasks during the first generation to establish baseline performance [2].

Evolutionary Process:

- For each generation, select parent individuals based on scalar fitness using tournament selection or similar methods [11].

- Apply crossover operators (typically simulated binary crossover) with probability pc (usually 0.7-0.9) [24].

- Apply mutation operators (typically polynomial mutation) with probability pm (usually 1/D) [24].

- Evaluate offspring only on their inherited skill factor task unless in first generation [22].

- Combine parent and offspring populations, select survivors based on scalar fitness to maintain population size [2].

Table 2: Standard Experimental Parameters in MFEA Studies

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Values | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Size | N | 100-500 | Balances exploration and computational cost |

| Random Mating Probability | rmp | 0.3-0.5 | Controls cross-task knowledge transfer rate |

| Crossover Probability | pc | 0.7-0.9 | Governs recombination frequency |

| Mutation Probability | pm | 1/D | Maintains population diversity |

| Maximum Generations | - | 500-5000 | Determines algorithm termination point |

Performance Metrics:

- Multitasking Performance: Evaluation of solution quality for each component task compared to single-task evolutionary algorithms [11] [23].

- Convergence Speed: Number of generations or function evaluations required to reach target solution quality [2].

- Knowledge Transfer Efficiency: Measured through the success rate of cross-task transfers and their impact on convergence [25].

Advanced MFEA Variations and Research Directions

Enhanced MFEA Architectures

Recent research has developed sophisticated MFEA variations to address limitations in the original architecture:

MFEA with Diffusion Gradient Descent (MFEA-DGD): Incorporates theoretical foundations from gradient-based optimization, proving convergence for multiple similar tasks and demonstrating how local convexity of some tasks can help others escape local optima [23].

Two-Level Transfer Learning (TLTL) Algorithm: Implements upper-level inter-task transfer learning via chromosome crossover and elite individual learning, and lower-level intra-task transfer learning based on information transfer of decision variables for across-dimension optimization [2].

Multi-Role Reinforcement Learning Approach: Employs a comprehensive RL system with specialized agents for task routing (where to transfer), knowledge control (what to transfer), and transfer strategy adaptation (how to transfer) [25].

Interactive MFEA with Multidimensional Preference Models: Extends MFEA to personalized recommendation systems, constructing multidimensional preference user surrogate models to approximate different perceptions of preferences [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: MFEA Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MFEA Experimentation

| Research Reagent | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Unified Representation Scheme | Encodes solutions from different tasks into common space | Random-key encoding [0,1]D [22] |

| Factorial Cost Calculator | Computes task-specific performance metrics | αij = γδij + Fij with constraint handling [2] |

| Skill Factor Assigner | Identifies specialized task for each individual | τi = argmin{rij} computation module [2] |

| Assortative Mating Controller | Governs cross-task reproduction | Random mating probability (rmp) controller [11] |

| Selective Evaluator | Reduces computational cost | Offspring evaluation only on inherited task [22] |

| Knowledge Transfer Monitor | Tracks cross-task information flow | Inter-task similarity and transfer success measurement [25] |

Applications and Performance Analysis

Domain-Specific Implementations

MFEA has demonstrated significant performance improvements across diverse application domains:

Networked Systems Optimization: MFEA-Net concurrently tackles network robustness optimization and robust influence maximization, considering multiple optimization scenarios simultaneously [11]. Experimental results show superior performance compared to single-task approaches, with approximately 15-30% improvement in solution quality on synthetic and real-world networks.

Assembly Line Balancing: An improved multi-objective MFEA (IMO-MFEA) successfully addresses assembly line balancing problems considering regular production and preventive maintenance scenarios [24]. The algorithm reduces cycle times by 12-18% while minimizing operation alterations compared to traditional methods.

Personalized Recommendation Systems: Interactive MFEA with multidimensional preference surrogate models improves individual diversity by 54.02% and surprise degree by 2.69% while maintaining competitive recommendation accuracy (only 5% reduction in Hit Ratio) [26].

Performance Interpretation Framework

The convergence behavior and knowledge transfer effectiveness in MFEA can be interpreted through the lens of task relatedness and landscape characteristics [23]:

Task Relatedness: Highly related tasks with complementary landscape characteristics typically benefit most from knowledge transfer, with performance improvements of 25-40% observed in controlled studies [11] [23].

Transfer Intensity: Optimal random mating probability (rmp) varies with task relatedness, typically between 0.3-0.5 for moderately related tasks [11] [22].

Population Sizing: Larger populations (200-500 individuals) generally benefit complex multitasking environments with heterogeneous tasks, while smaller populations (100-200) suffice for simpler homogeneous task sets [22].

The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm represents a significant advancement in evolutionary computation, enabling efficient concurrent optimization of multiple tasks through its sophisticated skill factor mechanism and knowledge transfer architecture. The algorithm's core innovation lies in its unified representation space and implicit transfer learning approach, which allows synergistic interactions between tasks without requiring explicit similarity measures. The skill factor definition—τi = argmin{rij}—serves as the fundamental mechanism for resource allocation and selective knowledge exchange, making it the cornerstone of successful evolutionary multitasking. As research progresses, integration with reinforcement learning for adaptive transfer control [25], theoretical foundations from gradient-based optimization [23], and domain-specific customizations continue to enhance MFEA's capabilities and applicability across scientific and engineering domains, particularly in complex drug development environments where multiple related optimization problems must be addressed simultaneously.

In the realms of computational optimization and drug development, researchers frequently face the challenge of solving multiple distinct tasks simultaneously. Traditional approaches optimize for single objectives in isolation, potentially overlooking valuable synergies and complementarities between related tasks. The paradigm of Multifactorial Optimization (MFO) addresses this limitation by enabling the concurrent optimization of multiple self-contained tasks through a single, unified algorithmic run [22]. At the core of this paradigm lies the concept of unified representation and decoding—a computational technique that creates a common search space enabling knowledge transfer across diverse tasks [27].

Within the specific context of drug development, this approach holds significant promise. The drug development pipeline encompasses numerous optimization challenges, from molecular design and preclinical testing to clinical trial management and pharmacokinetic analysis [28] [29] [30]. Each of these domains presents unique optimization landscapes, yet they share underlying biological and chemical principles that could be exploited through intelligent knowledge transfer mechanisms. By framing these distinct challenges within a unified representation, multifactorial evolutionary algorithms can potentially accelerate the discovery process and improve success rates in an industry where only approximately 7.9% of new drug candidates successfully navigate from conception to market approval [31].

This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations, methodological frameworks, and practical implementations of unified representation schemes within multifactorial evolution research. By examining the intricate relationship between skill factor definition and knowledge transfer mechanisms, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive toolkit for implementing these advanced optimization techniques in their own work.

Theoretical Foundations of Unified Representation

Fundamental Principles of Multifactorial Optimization

Multifactorial Optimization (MFO) represents a significant departure from conventional single-task optimization approaches. In an MFO environment, multiple optimization tasks are solved simultaneously within a single run of an evolutionary algorithm, with implicit knowledge transfer occurring between tasks [22]. The fundamental motivation behind this paradigm stems from the observation that real-world problems seldom exist in isolation, and that human cognition naturally excels at transferring knowledge between related tasks [10].

The mathematical foundation of MFO establishes a framework for comparing individuals in a multitasking environment through several key properties:

- Factorial Cost: The objective value of an individual solution when evaluated on a particular task Tj [22]

- Factorial Rank: The index of an individual in a population sorted by ascending factorial cost for a specific task [27] [22]

- Scalar Fitness: A unified measure of performance across all tasks, calculated as the reciprocal of the best factorial rank [22]

- Skill Factor: The specific task on which an individual demonstrates superior performance relative to other tasks [27] [22]

These properties enable direct comparison of candidate solutions across different task domains, facilitating the implicit transfer of knowledge between optimization landscapes.

The Unified Search Space Paradigm

A cornerstone of the multifactorial evolutionary algorithm (MFEA) is the implementation of a unified representation scheme that encodes solutions for all tasks within a common search space [22]. This approach typically employs a normalized search space Y = [0, 1]^D, where D represents the maximum dimensionality across all tasks being optimized. Through this normalization process, solutions for tasks with varying decision variables can be represented within a single, homogeneous genetic space [22].

The transformation from unified representation to task-specific solutions occurs through decoding mechanisms that map points in the unified space to valid solutions in each task's native search space. This decoding process is task-specific and must be carefully designed to ensure that the genetic operations in the unified space produce meaningful variations in each task's solution space. The efficacy of this approach hinges on the assumption that beneficial genetic traits in one task may confer advantages in related tasks, thereby accelerating the overall optimization process through implicit transfer learning [10].

Table 1: Key Properties for Individual Evaluation in Multifactorial Optimization

| Property | Mathematical Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Factorial Cost | Ψj^i = fj^i | Objective value of individual i on task j |

| Factorial Rank | rj^i = index in sorted population by Ψj | Performance percentile of individual i on task j |

| Scalar Fitness | φi = 1/min{rj^i} | Unified performance metric across all tasks |

| Skill Factor | τi = argmin{rj^i} | Task where individual i performs best |

Skill Factor Definition and Its Role in Knowledge Transfer

Theoretical Framework of Skill Factor Assignment

The skill factor represents a crucial component in multifactorial evolutionary algorithms, serving as the mechanism that determines an individual's specialized expertise within a multitasking environment. Formally defined, the skill factor τi of an individual pi is the specific task index on which the individual demonstrates optimal performance relative to all other tasks: τi = argmin{rj^i} [27] [22]. This assignment effectively creates implicit niches within the population, where individuals naturally gravitate toward and specialize in particular tasks based on their innate capabilities.