Simulating Developmental Evolution with Algorithms: A New Frontier for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

This article explores the transformative potential of algorithms that simulate developmental evolutionary (Evo-Devo) processes for a specialized audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Simulating Developmental Evolution with Algorithms: A New Frontier for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of algorithms that simulate developmental evolutionary (Evo-Devo) processes for a specialized audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It provides a comprehensive examination of the foundational principles of evolutionary computation, including genetic algorithms and evolutionary strategies. The scope extends to detailed methodological approaches for implementing these simulations, with a specific focus on applications in drug design, such as molecular optimization and property prediction. The content further addresses critical challenges in model reliability and optimization, including data scalability and black-box interpretability, and provides a framework for the validation and comparative analysis of different algorithmic approaches against traditional methods. Finally, the article synthesizes key findings to project future directions and implications for accelerating biomedical innovation.

From Biology to Code: The Core Principles of Simulated Evolutionary Optimization

Core Principles and Analogies

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are a class of population-based metaheuristic optimization algorithms inspired by the principles of natural selection and genetics [1]. They provide a computational framework for solving complex problems for which no satisfactory exact solution methods are known, by reproducing essential mechanisms of biological evolution: reproduction, mutation, recombination, and selection [1]. In this analogy, a population of candidate solutions to an optimization problem represents individuals in an ecosystem, and a fitness function determines the quality of these solutions, analogous to an individual's ability to survive and reproduce [1] [2].

The foundational concepts of EAs draw direct parallels from biological evolution [3]:

- Natural Selection: In nature, fitter individuals are more likely to survive and pass their genes to the next generation. In EAs, candidate solutions with better fitness scores are preferentially selected as "parents" [2].

- Mutation: Random genetic changes introduce novel traits in offspring. In EAs, the mutation operator introduces random modifications to offspring solutions, maintaining population diversity and enabling exploration of new regions in the search space [3].

- Recombination (Crossover): Offspring inherit genetic material from two parents. In EAs, the crossover operator combines parts of two or more parent solutions to create new offspring solutions [2].

- Genetic Drift: In small populations, random chance can cause gene frequency changes. This biological concept informs EA design, highlighting the risk of "premature convergence" in small populations and the importance of diversity-preserving mechanisms [3].

The Generic Evolutionary Algorithm Workflow

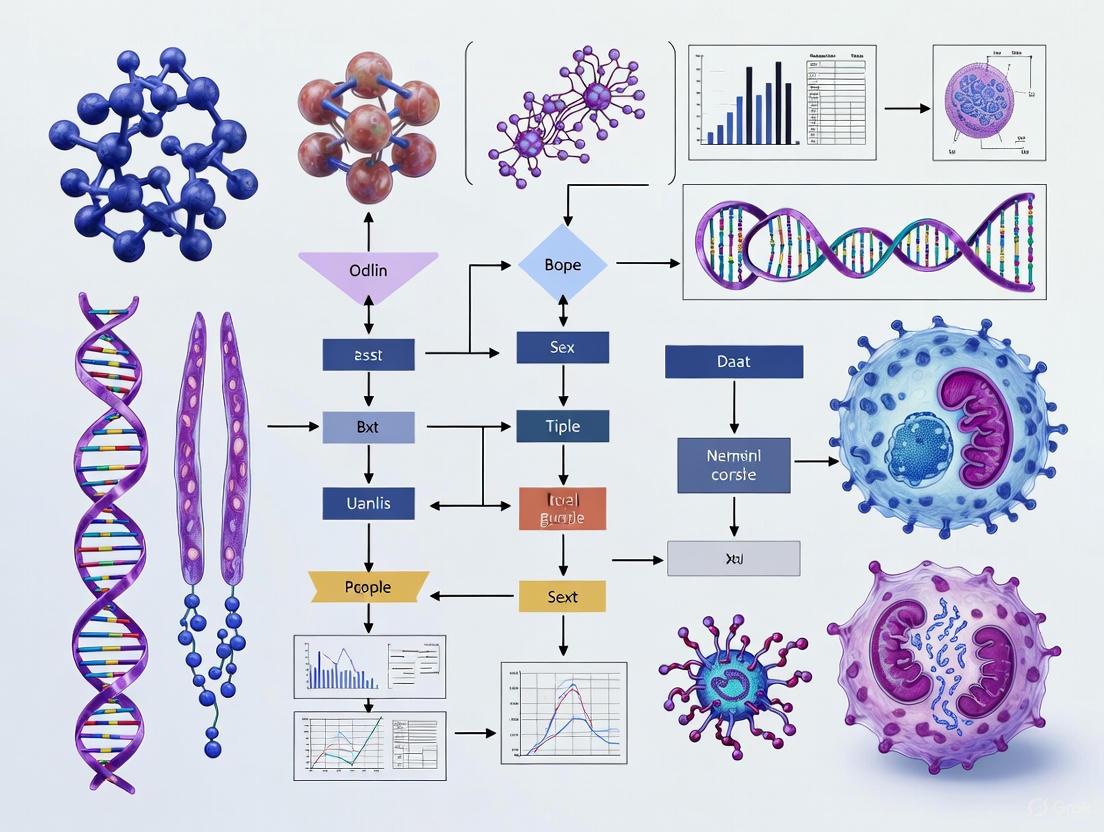

The following diagram illustrates the iterative process of a generic Evolutionary Algorithm, showing how a population evolves over generations toward improved fitness.

Figure 1: The iterative workflow of a generic Evolutionary Algorithm.

The algorithm operates as a cycle, iterating over the following steps [1] [2]:

- Initialization: Randomly generate an initial population of individuals (candidate solutions).

- Fitness Evaluation: Calculate the fitness of each individual in the population using a problem-specific fitness function.

- Termination Check: If a termination condition is met (e.g., a satisfactory solution is found, a maximum number of generations is reached), the algorithm stops and returns the best solution(s).

- Parent Selection: Select individuals from the current population to act as parents, with a bias towards higher fitness.

- Reproduction: Create offspring from the selected parents through crossover (recombining genetic material from multiple parents) and mutation (introducing small random changes) operators.

- Population Update: Select individuals, preferably of lower fitness, for replacement by the new offspring, mimicking natural selection.

This cycle repeats, forming subsequent generations, until the termination criteria are satisfied [1].

Algorithm Variants and Technical Specifics

Evolutionary algorithms encompass a family of related techniques that differ in their representation of individuals and implementation details [1].

Table 1: Key Types of Evolutionary Algorithms

| Algorithm Type | Solution Representation | Primary Application Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) [1] [2] | Strings of numbers (e.g., binary, integers) | Broad optimization problems |

| Genetic Programming (GP) [1] | Computer programs | Program synthesis, symbolic regression |

| Evolution Strategy (ES) [1] | Vectors of real numbers | Numerical optimization |

| Differential Evolution [1] | Vectors based on differences | Numerical optimization |

| Neuroevolution [1] | Artificial neural networks | AI, game playing, control systems |

| Learning Classifier System [1] | Set of rules (classifiers) | Data mining, pattern recognition |

| Quality-Diversity Algorithms [1] [4] | Varies (e.g., neural networks, programs) | Generating diverse, high-performing solutions |

Application Protocol: Drug Discovery with REvoLd

The REvoLd (RosettaEvolutionaryLigand) protocol represents a cutting-edge application of EAs for screening ultra-large make-on-demand chemical libraries in drug discovery, demonstrating the practical utility of EAs in a high-stakes research domain [5].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The diagram below outlines the specific steps of the REvoLd protocol for evolutionary ligand discovery.

Figure 2: The REvoLd protocol for evolutionary ligand discovery.

Detailed Methodology [5]:

Problem Definition and Initialization:

- Chemical Space Definition: The algorithm operates on a combinatorial chemical library (e.g., Enamine REAL Space), constructed from lists of substrates and known chemical reactions. This ensures all explored molecules are synthetically accessible.

- Initial Population: Randomly generate an initial population of ligands (e.g., 200 individuals) from the defined chemical space.

Fitness Evaluation:

- Employ a flexible protein-ligand docking protocol (RosettaLigand) that allows for both ligand and receptor flexibility. This provides a more accurate binding affinity prediction compared to rigid docking.

- The docking score serves as the fitness function, with lower (more negative) scores indicating better predicted binding and higher fitness.

Evolutionary Cycle:

- Selection: Select the top-performing individuals (e.g., 50 ligands) from the current population to serve as parents for the next generation.

- Reproduction:

- Crossover: Recombine fragments from pairs of fit parents to create novel offspring ligands.

- Mutation - Fragment Switching: Replace single fragments in a promising ligand with low-similarity alternatives, preserving most of the structure while introducing significant local novelty.

- Mutation - Reaction Switching: Change the core reaction used to assemble the ligand fragments, exploring fundamentally different regions of the combinatorial space.

- Population Update: Create a new generation by combining a percentage of the fittest individuals from the previous generation (elitism) with the newly generated offspring. The algorithm incorporates a secondary round of crossover and mutation excluding the very fittest molecules to allow less-fit individuals with potentially useful genetic material to contribute.

Termination and Output:

- The process runs for a predefined number of generations (e.g., 30), after which it outputs a set of high-scoring, synthetically accessible ligand candidates.

- Multiple independent runs are recommended to explore diverse regions of the chemical space and uncover various promising scaffolds.

Performance Metrics and Reagent Solutions

Table 2: REvoLd Benchmark Performance on Drug Targets [5]

| Performance Metric | Result | Context & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Hit Rate Enrichment Factor | 869 to 1622 | Compared to random selection; demonstrates exceptional efficiency in finding potential drug candidates. |

| Molecules Docked per Target | ~49,000 to ~76,000 | Total unique molecules docked over 20 runs; a tiny fraction of the billion-sized library, showing targeted exploration. |

| Convergence Behavior | Good solutions in ~15 gens; continued discovery after 30 gens | Balances rapid initial improvement with sustained exploration, avoiding immediate stagnation. |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Algorithm-based Drug Discovery

| Tool / Resource | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Combinatorial Chemical Library (e.g., Enamine REAL Space) [5] | Defines the vast search space of synthetically accessible molecules from which ligands are built and evolved. |

| RosettaLigand Software [5] | Provides the flexible docking backend that evaluates the fitness (predicted binding affinity) of each candidate ligand. |

| REvoLd Algorithm [5] | The core evolutionary framework that orchestrates selection, crossover, and mutation to efficiently navigate the chemical space. |

| Fragment Libraries & Reaction Rules [5] | The "genetic alphabet" and "grammar" that define the building blocks and allowable combinations for constructing valid molecules. |

Theoretical and Practical Considerations

Theoretical Foundations

- No Free Lunch Theorem: This theorem states that no single optimization algorithm is universally superior to all others across all possible problems [1]. Therefore, to be effective, EAs must incorporate domain-specific knowledge, such as problem-adapted representations (e.g., real-valued vectors for numerical optimization) or hybridizations with local search procedures (creating memetic algorithms) [1].

- Convergence: For EAs that preserve the best individual from one generation to the next (elitist EAs), it can be proven that the algorithm will converge to an optimal solution if one exists [1]. However, practical convergence rates and the risk of premature convergence on suboptimal solutions are influenced by operator choices and population management strategies.

Practical Implementation Insights

- Maintaining Diversity: A key challenge is balancing the exploitation of good solutions through selection with the exploration of the search space via mutation and crossover [3]. In small populations, the stochastic force of genetic drift can overpower selection and lead to premature convergence. Using sufficiently large population sizes, low mutation rates, and diversity-preserving mechanisms (e.g., niche promotion, specific population models) is recommended to counteract this [1] [3].

- Fitness Function Design: The fitness function must not only define the end goal but also effectively guide the search process. This sometimes requires rewarding incremental improvements that do not immediately fulfill the final quality criteria [1].

Evolutionary systems are a class of optimization algorithms inspired by biological evolution, designed to solve complex problems across scientific domains. These systems operate on a population of potential solutions, applying principles of selection based on fitness and genetic variation to iteratively improve solutions over generations. For researchers in drug development and biomedical engineering, evolutionary algorithms provide powerful tools for tackling challenges with large search spaces and multiple competing objectives. This article examines the three core components of these systems—populations, fitness functions, and genetic operators—within the context of simulating developmental evolution, complete with practical implementation protocols for research applications.

Core Components and Theoretical Framework

Populations

The population constitutes the fundamental substrate for evolutionary algorithms, representing a collection of potential solutions to the optimization problem. Population diversity is critical for effective evolutionary search, as it maintains exploration capacity and prevents premature convergence to local optima. In Dynamic Gene Expression Programming (DGEP), researchers have developed an Adaptive Regeneration Operator (DGEP-R) that introduces new individuals at critical evolutionary stages when fitness stagnation occurs [6]. This approach has demonstrated a 2.3× increase in population diversity compared to standard GEP, significantly enhancing global search capability [6]. Population-based methods like the Paddy field algorithm employ density-based reinforcement, where solution vectors (plants) produce offspring based on both fitness and local population density, creating a natural mechanism for maintaining diversity while exploiting promising regions of the search space [7].

Fitness Functions

Fitness functions serve as the objective measure of solution quality, guiding the evolutionary process toward optimal regions of the search space. In systems biology and drug development, these functions often combine quantitative and qualitative data. A powerful approach converts qualitative observations into inequality constraints that are incorporated into the fitness evaluation [8]. The combined objective function takes the form:

ftot(x) = fquant(x) + fqual(x)

where fquant(x) represents the standard sum of squares over quantitative data points, and fqual(x) implements a penalty function for violations of qualitative constraints [8]. This methodology is particularly valuable in biological contexts where qualitative phenotypes (e.g., viability/inviability of mutant strains) provide critical information for parameterizing models [8].

Genetic Operators

Genetic operators introduce variation into the population, enabling exploration of new solutions. These include mutation, crossover, and specialized operators that modify individuals or their representations. DGEP introduces a Dynamically Adjusted Mutation Operator (DGEP-M) that modulates mutation rates based on evolutionary progress, effectively balancing exploration and exploitation throughout the search process [6]. In multiobjective RNA inverse folding problems, researchers have experimented with various crossover operators including Simulated Binary, Differential Evolution, One-Point, Two-Point, K-Point, and Exponential crossovers, combined with selection operators such as Random and Tournament selection [9]. The performance of these operator combinations varies significantly across problem domains, highlighting the importance of operator selection to specific applications.

Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Molecular Design and Optimization

Evolutionary algorithms have demonstrated remarkable success in molecular design tasks. In one implementation, molecular structures are evolved using a genetic algorithm operating on Morgan fingerprint vectors, with a recurrent neural network decoding the evolved fingerprints into valid molecular structures [10]. This approach maintains chemical validity while optimizing for target properties such as light-absorbing wavelengths. The method employs structural constraints through blacklisted substructures to ensure synthetic feasibility and maintain desired molecular characteristics [10].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Evolutionary Algorithms in Molecular Design

| Algorithm | Application Domain | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| DGEP [6] | Symbolic regression | 15.7% better R² scores, 35% higher escape rate from local optima | Dynamic operator adjustment prevents premature convergence |

| Multiobjective EA [9] | RNA inverse folding | Hypervolume (HV), Constraint Violation (CV) metrics | Effective handling of conflicting objectives in sequence design |

| Deep Learning-Guided GA [10] | Organic molecule design | Successful wavelength optimization while maintaining validity | Chemical validity ensured through neural network decoding |

| Paddy Algorithm [7] | Chemical optimization | Robust performance across diverse benchmarks, resistance to local optima | Density-based propagation without inferring objective function |

Drug Discovery and Development

In pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) modeling, evolutionary algorithms and related optimization techniques play crucial roles in parameter identification and experimental design. Physiologically based PK (PBPK) models integrate drug-specific parameters (molecular weight, lipophilicity, permeability) with biological system parameters (blood flow, organ volume) to predict drug behavior [11]. Evolutionary optimization helps refine these complex models, enabling more accurate prediction of efficacy and safety profiles during early-stage drug development [11]. The transition from descriptive to predictive models represents a significant advancement in pharmaceutical research, with evolutionary algorithms facilitating the identification of optimal parameter values from limited experimental data.

Accessible Design Solutions

Evolutionary algorithms have demonstrated versatility in addressing accessibility challenges in scientific communication. Researchers have employed genetic algorithms to optimize color schemes for user interfaces, ensuring sufficient contrast for users with color vision deficiencies while preserving aesthetic qualities [12]. By incorporating Web Content Accessibility Guidelines into the fitness function, these systems evolve color palettes that meet specific contrast ratio requirements (4.5:1 for Level AA, 7:1 for Level AAA) while minimizing perceptual differences from original designs [12]. This application highlights how evolutionary systems can balance multiple, potentially competing objectives to create inclusive scientific tools.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing Dynamic Gene Expression Programming for Symbolic Regression

Objective: Apply DGEP to solve symbolic regression problems with enhanced diversity maintenance.

Materials and Software:

- Programming environment with DGEP implementation

- Benchmark function datasets

- Performance evaluation metrics (R², diversity measures)

Procedure:

- Initialize Population: Create an initial population of candidate solutions representing mathematical expressions.

- Implement Adaptive Regeneration (DGEP-R): Monitor fitness improvement rates. When stagnation is detected (e.g., <1% improvement over 10 generations), introduce new randomly generated individuals to replace worst-performing solutions [6].

- Apply Dynamically Adjusted Mutation (DGEP-M): Calculate mutation rates based on recent evolutionary progress:

mutation_rate = base_rate × (1 - improvement_rate)[6]. - Evaluate Fitness: Compute fitness using mean squared error between predicted and target values.

- Select Parents: Use tournament selection to choose parents for reproduction.

- Apply Genetic Operators: Perform crossover and mutation operations to create offspring population.

- Repeat: Iterate steps 2-6 for predetermined generations or until convergence criteria met.

Validation: Compare DGEP performance against standard GEP on benchmark functions, measuring solution accuracy (R²), population diversity, and convergence rates [6].

Protocol: Multiobjective Optimization for RNA Inverse Folding

Objective: Design RNA sequences that fold into target secondary structures using multiobjective evolutionary algorithms.

Materials and Software:

- RNA folding prediction software (e.g., ViennaRNA)

- Multiobjective evolutionary algorithm framework

- Benchmark RNA structures

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: Define the RNA inverse folding problem with three objective functions: Partition Function, Ensemble Diversity, and Nucleotides Composition, with a Similarity constraint [9].

- Solution Representation: Implement real-valued chromosome encoding representing RNA sequences.

- Algorithm Selection: Choose from multiobjective evolutionary algorithms (e.g., NSGA-II, SPEA2) and operator combinations.

- Operator Configuration: Test various crossover operators (Simulated Binary, Differential Evolution, One-Point, Two-Point) with selection operators (Random, Tournament) [9].

- Evaluation: For each candidate sequence, compute objective values using RNA folding predictions.

- Evolutionary Process: Run the multiobjective optimization for sufficient generations to achieve convergence.

- Solution Analysis: Identify Pareto-optimal solutions from the final population.

Validation: Evaluate performance using hypervolume (HV) and constraint violation (CV) metrics on benchmark RNA structures [9].

Protocol: Deep Learning-Guided Evolutionary Molecular Design

Objective: Optimize organic molecules for target properties using evolutionary algorithms guided by deep learning.

Materials and Software:

- Chemical database (e.g., PubChem)

- RDKit cheminformatics toolkit

- Recurrent neural network (RNN) for SMILES generation

- Deep neural network (DNN) for property prediction

Procedure:

- Seed Selection: Choose initial seed molecules from existing database in SMILES format.

- Molecular Encoding: Convert SMILES to extended-connectivity fingerprint (ECFP) vectors using a 5000-dimensional representation with neighborhood size of 6 [10].

- Initial Population Generation: Create population of fingerprint vectors through mutation of seed molecule fingerprints.

- Decoding and Validation: Use RNN to convert ECFP vectors to SMILES strings, validating chemical correctness with RDKit.

- Fitness Evaluation: Predict molecular properties using DNN model with ECFP vectors as input.

- Selection and Reproduction: Select top-performing molecules as parents for next generation using fitness scores.

- Genetic Operations: Apply crossover and mutation to parent fingerprints to create offspring population.

- Structural Constraints: Apply blacklist filters to eliminate molecules with undesirable substructures (e.g., fused rings outside size 4-7, alkyl chains >6 carbons) [10].

- Iteration: Repeat steps 4-8 for multiple generations until target properties are achieved.

Validation: Synthesize and experimentally test top-evolved molecules to verify predicted properties [10].

Visualization of Workflows

DGEP Operational Workflow

Deep Learning-Guided Molecular Evolution

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Evolutionary Algorithm Implementation

| Item Name | Type/Category | Function in Research | Example Sources/Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Chemical validity checking, molecular manipulation | Open-source cheminformatics |

| EvoTorch | Optimization Library | Implementation of evolutionary algorithms | Python-based framework |

| ViennaRNA | Bioinformatics Software | RNA secondary structure prediction | Open-source bioinformatics |

| PubChem Database | Chemical Repository | Source of seed molecules and training data | NIH public database |

| Paddy Algorithm | Evolutionary Optimizer | Density-based evolutionary optimization | Python library (GitHub) |

| NONMEM | PK-PD Modeling Software | Nonlinear mixed effects modeling for drug development | Commercial software |

| Ax Framework | Bayesian Optimization | Benchmarking and comparison of optimization methods | Meta Open Source |

| Hyperopt | Python Library | Tree-structured Parzen estimator optimization | Open-source Python library |

Evolutionary systems provide a powerful framework for solving complex optimization problems in drug development and biomedical research. The synergistic interaction between populations, fitness functions, and genetic operators enables these algorithms to efficiently navigate high-dimensional search spaces while balancing multiple objectives. The protocols and applications presented in this article demonstrate the practical utility of these methods across diverse domains, from molecular design to PK-PD modeling. As evolutionary algorithms continue to evolve with advancements in deep learning and hybrid approaches, their capacity to accelerate scientific discovery and therapeutic development will expand accordingly. Researchers are encouraged to systematically evaluate operator combinations and problem representations to maximize performance for specific applications.

Application Notes

Theoretical Foundation and Biological Analogy

The conceptual framework for bridging micro- and macroevolution rests on the principle that long-term, large-scale evolutionary patterns (macroevolution) emerge from the accumulation of population-level processes (microevolution) such as mutation, selection, gene flow, and genetic drift [13] [14]. A critical insight from biological studies is that the same forces driving population differentiation—such as chromosomal rearrangements—can, over time, lead to lineage diversification and speciation [13]. Computational models allow us to formalize this relationship, treating evolution as a form of learning or optimization process where successful phenotypic "solutions" are discovered through iterative trial and error across generations [15]. This process can lead to phenomena analogous to overfitting in machine learning, where a population becomes highly specialized for a specific environment but loses the flexibility to adapt to new conditions, representing an evolutionary trade-off [15].

The proposed computational framework is a bottom-up, process-based model that integrates mechanisms across different biological levels to simulate how microevolutionary processes generate macroevolutionary trends. The core components and their interactions are visualized in the following workflow. This integrated approach allows for the emergence of large-scale biodiversity patterns, such as biphasic diversification and niche structuring, from explicit individual-level processes [16].

Key Quantitative Parameters for Model Configuration

To operationalize the framework, specific quantitative parameters must be defined. These parameters control the behavior of the simulation and can be adjusted to test different evolutionary hypotheses. The table below summarizes the core parameters derived from evolutionary biology and computational modeling.

Table 1: Key Parameters for the Multi-Level Evolutionary Framework

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Biological/Computational Significance | Typical Value/Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Architecture | Mutation Rate | Controls the introduction of new genetic variation [16]. | User-defined (e.g., 10⁻⁵–10⁻⁸ per locus) |

| Gene Duplication Rate | Enables genomic expansion and emergence of novel functions [16]. | Stochastic, user-defined probability | |

| Recombination Rate | Impacts linkage disequilibrium and efficiency of selection [16]. | User-defined | |

| Population Dynamics | Migration Rate (Gene Flow) | Counteracts divergence; key to linking micro/macroevolution [17]. | 0 (isolated) to 0.5 (panmictic) |

| Population Size (N) | Affects genetic drift and effectiveness of selection [16]. | Variable (e.g., 100–10,000 individuals) | |

| Selection Strength (σ² in OU) | Strength of stabilizing selection towards an optimum [17]. | Estimated from trait data | |

| Phenotypic Landscape | Number of Phenotypic Traits | Defines complexity and dimensionality of adaptation [16]. | User-defined (e.g., 1–100) |

| Number of Ecological Niches | Determines diversity of selective pressures [16]. | Emergent or user-defined | |

| Macroevolution | Speciation Threshold | Phenotypic/genetic divergence level for speciation [16]. | User-defined (e.g., 5% divergence) |

| Background Extinction Rate | Base rate of lineage extinction [16]. | User-defined (e.g., 0.1 events/My) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Simulating Trait Evolution under Gene Flow and Selection

This protocol uses an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process with migration to model phenotypic trait evolution along a phylogeny, explicitly incorporating the microevolutionary process of gene flow during speciation [17].

- Objective: To estimate the strength of selection and migration from time-series or phylogenetic comparative data and assess the bias introduced by ignoring gene flow.

Materials and Software:

- Programming Environment: R or Python.

- Key R Packages:

geiger,ouch,splits. - Input Data: A time-series of trait means from subpopulations or a phylogeny with trait data at the tips.

Procedure:

- Model Formulation: Define an OU process for two subpopulations that share a migrant pool. The model is characterized by the stochastic differential equation:

dX(t) = α(θ - X(t))dt + σdW(t)whereX(t)is the trait mean,αis the strength of selection,θis the optimal trait value,σis the random fluctuation rate, anddW(t)is the Wiener process [17]. - Parameterize Migration: Incorporate a migration rate

mthat decreases exponentially over time within a branch of the phylogeny, simulating the reduction of gene flow during speciation:m(t) = m₀ * exp(-λt)[17]. - Parameter Estimation: Use maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference to jointly estimate the parameters

α,σ, andm₀from the input data. - Model Comparison: Compare the model's fit against a traditional OU model that lacks migration (

m=0) using likelihood-ratio tests or information criteria (AIC/BIC) [17]. - Bias Assessment: Quantify the difference in estimated selection strength (

α) between the models with and without migration.

- Model Formulation: Define an OU process for two subpopulations that share a migrant pool. The model is characterized by the stochastic differential equation:

Expected Outcome: The model incorporating migration is expected to provide a better fit to the data. Neglecting migration will likely lead to a significant underestimation of the strength of selection and a decrease in the expected phenotypic disparity between species [17].

Protocol 2: Evolving Developmental Programs for Pattern Formation

This protocol uses evolutionary simulations of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) to explore the congruence between developmental and evolutionary sequences, a concept known as recapitulation [18].

- Objective: To evolve GRNs that can generate a target spatial pattern (e.g., stripes) and analyze the parallelism between the evolutionary trajectory and the developmental process.

Materials and Software:

- Simulation Framework: Custom C++, Python, or MATLAB code.

- Representation: A one-dimensional array of cells.

- GRN Model: A system of differential equations or a graph-based model governing gene expression in each cell.

Procedure:

- Initialization: Create a population of 100-1000 "organisms," each with a randomly initialized GRN. The GRN can be represented as a matrix of interaction weights or a graph [18] [19].

- Development: For each organism, run the GRN dynamics over a fixed developmental time. Gene expression in each cell is influenced by intracellular regulations and diffusion of signaling molecules between neighboring cells [18].

- Fitness Evaluation: When development is complete, calculate the fitness based on the match between the final expression pattern of a target "output" gene and a predefined optimal pattern (e.g., a series of stripes) [18].

- Selection and Reproduction: Select the top-performing individuals to become parents of the next generation. Create offspring by copying parental GRNs and introducing mutations (e.g., small changes to interaction weights or network structure).

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 for thousands of generations.

- Analysis:

- Track the evolutionary trajectory of the GRN and the phenotype.

- For the final evolved GRN, analyze the sequence of developmental pattern formation.

- Compare the sequence of pattern acquisition in evolution (over generations) with the sequence of pattern formation in development (over time within an individual) [18].

Expected Outcome: The simulation often reveals recapitulation: the evolutionary sequence of phenotypic change mirrors the developmental sequence, with general traits (e.g., broad domains) evolving and developing before specific ones (e.g., fine stripes) [18]. The dynamics are often epochal, with periods of stasis punctuated by rapid change.

Protocol 3: Generating Open-Ended Evolution with a Multi-Level Mechanistic Model

This protocol implements a comprehensive framework to study how macroevolutionary trends emerge from microevolutionary mechanisms without pre-defined goals (open-ended evolution) [16].

- Objective: To simulate the emergence of macroevolutionary patterns like diversification curves, species duration distributions, and niche structuring from individual-level processes.

Materials and Software:

- Software: The custom, open-source framework described in Latorre et al. (2025) or a similar agent-based platform [16].

- Computing Resources: High-performance computing (HPC) resources are recommended for large-scale simulations.

Procedure:

- World Initialization: Set up a simulated environment with defined resource distributions and spatial structure.

- Populate with Ancestors: Seed the environment with a founding population of individuals. Each individual possesses a genome that maps to its phenotypic traits via a defined genotype-phenotype map [16].

- Define Life-Cycle Operations: Implement the following core operations that run in each time step (generation):

- Fitness Evaluation & Selection: Individuals compete for resources and reproduce based on their fitness, which is determined by their traits and the environment [16].

- Mutation & Gene Flow: Introduce stochastic mutations (point mutations, gene duplications) and allow for migration and mating between subpopulations [16].

- Niche Construction & Biotic Interactions: Allow the activities and traits of organisms to modify their own and other species' selective environments (e.g., through resource consumption or predation) [16].

- Speciation Mechanism: Implement a dynamic speciation model where new species arise when subpopulations accumulate sufficient genetic and/or phenotypic divergence and become reproductively isolated, either allopatrically or sympatrically [16].

- Data Logging: Track macroevolutionary metrics over deep time, including:

- Species richness and diversification rates.

- Phylogenetic tree structure.

- Phenotypic disparity.

- Niche occupancy and overlap.

- Validation: Compare the emergent patterns from the simulation (e.g., species duration distributions, saturation of diversity) with known paleontological and phylogenetic patterns [16].

Expected Outcome: The framework is capable of reproducing multiple well-documented macroevolutionary patterns as emergent phenomena, such as biphasic diversification (high initial rate slowing over time), correlations between speciation and extinction, and self-organized niche occupancy [16].

Visualization of Core Concepts

The Adaptive Landscape as a Learning Process

The following diagram illustrates the analogy between evolution and machine learning, highlighting concepts like exploration (mutation/genetic drift), exploitation (selection), and the risk of overfitting (evolutionary trade-offs). This conceptual bridge can inform the design of more robust evolutionary algorithms and predictive models in biology [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential computational tools, models, and data types that serve as the "reagents" for conducting research in evolutionary computational modeling.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Evolutionary Simulation

| Reagent Category | Specific Item | Function/Purpose | Example/Biological Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Models | Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) Process | Models trait evolution under stabilizing selection towards an optimum; can be extended with migration [17]. | geiger R package |

| Brownian Motion (BM) Model | Models neutral trait evolution (baseline model) [17]. | phytools R package |

|

| Birth-Death Model | Models speciation and extinction processes on a phylogeny [16]. | TreeSim R package |

|

| Genotype-Phenotype Maps | Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) Models | Defines how genes interact to produce a phenotype during development; core to EvoDevo simulations [18] [19]. | System of differential equations or graph-based model (CGP/GNN) [19] |

| Quantitative Genetics Model | Maps additive genetic values to phenotypic traits [17]. | Lande model | |

| Data Inputs | Time-Series Data | Trait measurements over time for estimating microevolutionary parameters (selection, migration) [17]. | Field or experimental data |

| Phylogenetic Tree & Tip Data | Tree structure and trait data at tips for macroevolutionary inference [17] [16]. | Data from resources like TreeBASE | |

| Algorithmic "Primers" | Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Optimization technique inspired by natural selection [15]. | For hyperparameter tuning |

| Graph-Based Cartesian Genetic Programming (CGP) | An interpretable ("white-box") method for evolving GRNs or developmental rules [19]. | Evolving truss structures [19] |

The Emergence of Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Evo-Devo) in Algorithmic Design

Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Evo-Devo) has emerged as a transformative framework for algorithmic design, shifting the focus from directly optimizing final solutions to evolving generative rules that can develop designs over time. This approach, often termed "evolving the designer, not the design," leverages biological principles of how genotypes map to phenotypes through developmental processes [19]. In computational terms, this means evolving developmental rules encoded in a genome, which are then executed to generate complex structures, rather than evolving the structures themselves [19]. This paradigm is proving particularly valuable in fields with complex design spaces, including generative design in engineering and phenotypic screening in drug discovery, where it enables more flexible, adaptive, and interpretable solutions.

The core analogy draws from biology: natural evolution discovers powerful developmental plans (genomes) that, when executed, can generate adaptive phenotypes in response to environmental conditions. Similarly, Evo-Devo algorithms aim to discover computational developmental plans that can be reused and adapted across different problem instances [19] [20]. This stands in contrast to traditional optimization that produces single-point solutions, offering instead generative processes that exhibit properties like robustness, modularity, and evolvability. The integration of this approach with modern machine learning is providing a path beyond the limitations of black-box optimization, creating systems that not only perform well but are also more interpretable and reusable [19] [20].

Application Note 1: Generative Structural Design with Evo-Devo Principles

Protocol: Evolving Graph-Based Developmental Rules for Truss Structures

This protocol details a method for applying Evo-Devo principles to generative structural design, specifically for optimizing bridge truss structures. The approach evolves developmental rules that control local growth processes, which are then applied to an initial simple structure to develop a final, optimized design [19].

Step 1: Problem Representation and Initialization

- Represent the initial design (e.g., a simple bridge truss) as a graph where vertices represent joints and edges represent structural members.

- Decompose this graph into basic units termed "cells," each associated with a vertex and its connecting edges.

- Define the environmental stimulus for each cell based on the mechanical loading regime applied to the structure.

Step 2: Genotype Encoding and GRN Models

- Encode the developmental plan in a genome representing an artificial Gene Regulatory Network (GRN).

- Implement the GRN using one of two primary models:

- The GRN in each cell takes the local state (e.g., stress, strain) as input and outputs instructions for local growth actions.

Step 3: Developmental Cycle

- In each cell, execute the identical GRN model. The network responds to the local state of the cell, which is induced by external stimuli from the environment (structural loads) and neighboring cells [19].

- The GRN output controls local developmental mechanisms, such as moving vertices or changing edge features (e.g., cross-sectional area) [19].

- Execute this process synchronously or asynchronously across all cells for a predefined number of developmental time steps.

Step 4: Evolutionary Optimization of GRNs

- Use a genetic algorithm to evolve the parameters of the GRN models (GNN or CGP).

- Evaluate the fitness of each individual (a complete GRN) by:

- Applying its developmental rules to the initial design.

- Analyzing the resulting final structure using finite element analysis to compute performance metrics (e.g., weight-to-strength ratio, compliance).

- Select the best-performing individuals and use variation operators (mutation, crossover) to create the next generation.

- Repeat for multiple generations until a termination condition is met (e.g., fitness plateau, maximum generations).

Step 5: Rule Reuse and Transfer Learning

- Once evolved, the developed GRN can be applied to different but related engineering problems without running a full optimization procedure, enabling rapid design automation [19].

Quantitative Performance of GRN Models

Table 1: Comparison of GRN Models for Generative Structural Design [19]

| GRN Model | Key Characteristics | Interpretability | Performance | Primary Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Operates directly on graph structure; uses neural network weights | Low ("Black-box") | Produces near-optimal truss structures | High representational power and learning capacity |

| Cartesian Genetic Programming (CGP) | Graph-based representation of mathematical functions | High ("White-box") | Results similar to GNN-based methods | Produces human-interpretable developmental rules |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Evo-Devo Generative Design

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Representation Library | Encodes the design space as a graph of vertices and edges | Representing truss structures for cellular decomposition [19] |

| Finite Element Analysis Solver | Provides fitness evaluation by simulating structural performance | Calculating stress, strain, and displacement under load [19] |

| Evolutionary Algorithm Framework | Manages population and evolves GRN parameters | Conducting genetic search for optimal developmental rules [19] |

| GNN/CGP Implementation | Executes the core gene regulatory network logic | Translating local cell state into growth actions [19] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Evo-Devo generative design workflow. The process begins with a simple design, represents it as a graph, and uses an evolutionary loop to discover GRNs. These networks are then executed in a development cycle, influenced by the environment, to create the final structure. The evolved GRN can be reused.

Application Note 2: Phenotypic Screening in Drug Discovery

Protocol: An Evo-Devo-Inspired Approach to Phenotypic Drug Discovery

This protocol outlines a biology-first, phenotypic screening approach for drug discovery, which aligns with Evo-Devo principles by focusing on the observable outcome (phenotype) of cellular systems in response to perturbations, rather than starting with a predefined molecular target. The integration of multi-omics data and AI allows for the decoding of the underlying "developmental" pathways that lead to the observed phenotypic state [21].

Step 1: High-Content Phenotypic Screening

- Treat disease-relevant cells (e.g., cancer cell lines, patient-derived cells) with a library of chemical compounds or genetic perturbations.

- Use high-content imaging (e.g., Cell Painting assay) to capture multiparametric morphological data. This assay visualizes multiple cellular components (nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, etc.) to generate rich phenotypic profiles [21].

- Alternatively, employ single-cell technologies (e.g., Perturb-seq) to link genetic or compound perturbations to transcriptional outcomes at single-cell resolution [21].

Step 2: Data Integration and Multi-Omics Profiling

- Extract and process the cells post-perturbation for multi-omics analysis.

- Integrate the high-dimensional phenotypic data with layers of molecular omics data:

- Transcriptomics to reveal active gene expression patterns.

- Proteomics to clarify signaling and post-translational modifications.

- Metabolomics to contextualize stress response and disease mechanisms.

- Epigenomics to provide insights into regulatory modifications [21].

Step 3: AI-Driven Pattern Recognition and Model Building

- Use AI and machine learning models, such as deep learning networks, to fuse the heterogeneous phenotypic and multi-omics datasets.

- Train models to detect subtle phenotypic patterns that correlate with desired outcomes (e.g., disease reversion, efficacy, safety) [21].

- Implement specific AI tools for:

- Bioactivity Prediction: Integrating multimodal data to characterize compounds or predict on/off-target activity.

- Mechanism of Action (MoA) Elucidation: Inferring how tested compounds interact with the biological system to produce the observed phenotype.

- Virtual Screening: Identifying compounds that are predicted to induce a desired phenotypic profile, prioritizing them for further testing [21].

Step 4: Backtracking to Targets and Lead Optimization

- Once a compound inducing a beneficial phenotype is identified, use the integrated AI model to backtrack and propose potential molecular targets and pathways involved in the response [21].

- This approach "uncovers how to treat the disease without knowing the target a priori" [21].

- Validate proposed targets and pathways through follow-up experimental studies.

Step 5: Iterative Refinement

- Use the newly generated experimental data to refine the AI models, creating a closed-loop, adaptive learning system for continuous improvement of drug candidates.

Key Outcomes from Integrated Phenotypic Screening

Table 3: Exemplary Drug Discovery Outcomes from Evo-Devo-Inspired Phenotypic Screening [21]

| Disease Area | Technology/Model | Key Finding/Output |

|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | Archetype AI (Phenotypic Data + Omics) | Identified AMG900 and new invasion inhibitors from patient-derived data |

| COVID-19 | DeepCE Model (Predicting Gene Expression) | Predicted gene expression changes induced by chemicals; generated new lead compounds for repurposing |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer | idTRAX (Machine Learning) | Identified cancer-selective targets based on phenotypic profiling |

| Antibacterial Discovery | GNEprop, PhenoMS-ML (Imaging & Mass Spec) | Uncovered novel antibiotics by interpreting complex phenotypic outputs |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Phenotypic Screening & Multi-Omics Integration

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Painting Assay Kits | Generate high-content morphological profiles from fluorescent microscopy | Staining nuclei, ER, actin, etc., to create a phenotypic "fingerprint" [21] |

| Single-Cell Sequencing Kits | Link perturbations to transcriptional outcomes at single-cell resolution | Perturb-seq for functional genomics [21] |

| AI/ML Integration Platform | Fuses multimodal data for pattern recognition and prediction | Platforms like PhenAID for MoA prediction and virtual screening [21] |

| Multi-Omics Profiling Services | Provide molecular context (genomic, proteomic, metabolomic) | Adding layers of biological data to phenotypic observations [21] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 2: Phenotypic drug discovery workflow. The process starts by perturbing a biological system and measuring the phenotypic and multi-omics response. AI integrates this data to identify predictive patterns and elucidate the Mechanism of Action (MoA), leading to candidate validation and iterative refinement.

Core Evo-Devo Principles as Algorithmic Design Rules

The power of Evo-Devo in algorithmic design stems from the implementation of specific biological principles that govern how complex structures are generated. These principles can be formalized as general design rules for computational systems.

The Inhibitory Cascade as a Predictive Design Rule

A powerful example of a quantifiable Evo-Devo design rule is the Inhibitory Cascade (IC) model. Originally described in tooth development, it can be generalized to any sequentially forming structure that develops from a balance between auto-regulatory 'activator' and 'inhibitor' signals [22]. The model makes explicit quantitative predictions about the proportional variation among segments in a series.

The core IC equation for a segment ( sn ) is: [ [sn] = a - i \cdot n ] where ( n ) is the segment position, ( a ) is the activator strength, and ( i ) is the inhibitor strength [22].

For a three-segment system, this predicts:

- The middle segment size is ~1/3 of the total.

- The proximal and distal segment proportions act as a trade-off.

- Variance is apportioned parabolically, with the middle segment having the least variation.

This rule has been validated across diverse vertebrate structures, including phalanges, limb segments, and somites. In digits, for example, experimental blockade of signals between segments shifted proportions as predicted by the IC model, confirming its role as a fundamental regulatory logic [22]. This demonstrates how a high-level developmental rule can predict outcomes from microevolution to macroevolution.

Regulatory Connections and Somatic Variation

Two other critical principles are:

- Regulatory Connections: In computational Evo-Devo, the "genome" does not encode the final structure but a set of regulatory rules that control the development process. This is implemented through models like GNNs or CGP, which act as the Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) [19] [20]. These networks respond to local and environmental cues, allowing for context-dependent development.

- Somatic Variation & Selection with Weak Linkage: Biological development involves variation and selection at the cellular level (somatic) during an organism's lifetime, which is "weakly linked" to the genetic template. In algorithms, this can be mirrored by introducing stochastic, local variation during the developmental cycle (e.g., random movements of vertices), which is then selected based on global fitness. This helps systems escape local optima and increases robustness [20].

This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for genotype-to-phenotype (G-P) mapping, contextualized within computational research on simulating developmental evolution. The protocols are designed for researchers investigating the genetic architecture of complex traits.

The field employs diverse strategies, from detailed molecular mapping to genome-wide analyses. The following table summarizes the quantitative scope and key findings of several established approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Genotype-to-Phenotype Mapping Strategies

| Mapping Approach / Study | Genotypic Scale | Phenotypic Scale | Key Quantitative Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestral Transcription Factor Deep Mutational Scan | 160,000 protein variants (4 amino acid sites) | Specificity for 16 DNA response elements | Only 0.07% of genotypes were functional; GP map is strongly anisotropic and heterogeneous. | [23] |

| E. coli lac Promoter Mutagenesis | 75 base-pair promoter region | Transcriptional activity (1-9 fluorescence scale) | Additive effects accounted for ~67% of explainable phenotype variance; pairwise epistasis explained an additional ~7-15%. | [24] |

| G–P Atlas Neural Network (Simulated Data) | 3,000 loci across 600 individuals | 30 simulated phenotypes | Model captures additive, pleiotropic (20% chance per locus), and epistatic (20% chance per locus) effects simultaneously. | [25] |

| GSPLS Multi-omics Method (Small Sample) | Genome-wide SNPs | Disease state (e.g., Lung Adenocarcinoma) | Achieved superior prediction accuracy (AUC) on small sample datasets (n=84) compared to traditional methods. | [26] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Deep Mutational Scanning of a Protein-DNA Interface

This protocol details the procedure for empirically defining a high-resolution G-P map, as used in studies of ancestral transcription factors [23].

1.1 Library Construction

- Genotype Definition: Define the genotypic space as all possible combinations of amino acids at historically variable sites within the protein's functional domain (e.g., a recognition helix). For 4 sites with 20 possible amino acids, this yields 160,000 variants [23].

- DNA Synthesis: Synthesize a combinatorial library of DNA sequences encoding all genotypic variants.

- Vector Cloning: Clone the variant library into an appropriate expression vector.

1.2 Phenotypic Assay via Specificity Screening

- Phenotype Definition: Define the phenotypic space as the ability to recognize all possible substrates. For transcription factors, this involves specific binding to all combinatorial variants of a DNA response element (e.g., 16 possible sequences) [23].

- Reporter Strains: Engineer yeast strains, each containing a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., GFP) driven by a unique response element variant.

- Transformation & Selection: Transform each reporter strain with the entire protein variant library. Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to enrich for and isolate cells where a functional protein-DNA complex activates GFP expression.

1.3 Data Acquisition and Phenotype Assignment

- Deep Sequencing: Sequence the protein variants from sorted cell populations to determine enrichment scores for each genotype-phenotype pair.

- Fluorescence Modeling: Use a generalized linear model trained on experimental data to assign a quantitative fluorescence value, representing binding strength, to each protein-DNA complex [23].

- Classification: Classify protein variants as "specific" (functional with one RE), "promiscuous" (functional with multiple REs), or "nonfunctional" based on fluorescence thresholds derived from wild-type controls.

Protocol 2: G–P Atlas Neural Network Framework for Multi-Trait Prediction

This protocol outlines the data-efficient, neural network-based method for mapping genotypes to multiple phenotypes simultaneously [25].

2.1 Data Preparation and Model Architecture

- Input Data: Prepare paired genotype (e.g., SNP data) and phenotype (multiple quantitative traits) matrices.

- Two-Tiered Architecture: Implement a denoising autoencoder framework.

- Tier 1 - Phenotype Autoencoder: Train an encoder-decoder network to learn a low-dimensional, latent representation of the phenotypic data from a corrupted (noised) input. The decoder is fixed after this step.

- Tier 2 - Genotype Mapper: Train a separate network to map corrupted genotypic data directly into the latent space of the fixed phenotypic decoder.

2.2 Training and Validation

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use grid search to optimize latent space size, hidden layer size, and noise levels on a held-out test set (e.g., 20% of data).

- Training Regimen: Train the model using the Adam optimizer for a fixed number of epochs (e.g., 250) with a batch size of 16. Apply L1 and L2 regularization to the genotype mapper weights to prevent overfitting [25].

- Validation: Assess model performance on the test set using mean squared error for quantitative traits.

2.3 Inference and Variable Importance

- Phenotype Prediction: Use the trained model to predict complex trait outcomes from novel genotypic data.

- Causal Genotype Identification: Use permutation-based feature ablation to estimate the importance of individual genetic variants by measuring the increase in prediction error when that feature is omitted [25].

Diagrammatic Visualizations

Workflow for Deep Mutational Scanning

G–P Atlas Neural Network Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Genotype-to-Phenotype Mapping Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in G-P Mapping | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial DNA Library | Represents the full spectrum of genotypic variation to be tested. | Can be synthesized to cover all amino acid combinations at key protein sites [23]. |

| Barcoded Expression Vectors | Enables tracking of individual genotypic variants throughout a high-throughput assay. | Critical for multiplexed deep sequencing. |

| Reporter Cell Lines | Provides a scalable, functional readout for a molecular phenotype. | e.g., Yeast strains with GFP reporters for transcription factor binding [23]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Physically enriches cell populations based on phenotypic output (e.g., fluorescence). | Enables selection of functional variants from a large library [23]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Quantifies the abundance of each genotype before and after selection. | Used to calculate enrichment scores for variants. |

| eQTL Datasets | Provides pre-compiled data on associations between genetic variants and gene expression levels. | Used as a bridge to link genotype to molecular phenotype in silico (e.g., from GTEx) [26]. |

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks | Provides prior biological knowledge on gene-gene functional relationships. | Used to constrain and inform computational models (e.g., from PICKLE database) [26]. |

Implementing Evo-Devo Algorithms: Techniques and Transformative Applications in Drug Development

The integration of evolutionary algorithms and genetic programming into drug discovery represents a paradigm shift, enabling the efficient exploration of vast chemical and biological search spaces that are intractable for traditional methods. These bio-inspired algorithmic architectures excel in optimization tasks critical to pharmacology, from de novo molecular design to predicting drug-target interactions. By simulating evolutionary processes—selection, crossover, and mutation—these systems generate novel, synthetically accessible compounds with optimized properties. Framed within the broader thesis of simulating developmental evolution, these algorithms provide a computational framework where iterative, fitness-driven adaptation mirrors natural selection, accelerating the identification of viable therapeutic candidates. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these architectures, supported by quantitative benchmarks and standardized workflows for research scientists.

The drug discovery process is fundamentally a search problem within a combinatorial explosion of possible molecular structures and their interactions with biological targets. Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) and genetic programming (GP) address this by implementing a Darwinian search paradigm. A population of candidate solutions (e.g., molecular structures or binding poses) is iteratively refined over generations. Each candidate's fitness is evaluated against a defined objective function, such as binding affinity, selectivity, or favorable ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties. The fittest individuals are selected to propagate their "genetic" material to subsequent generations through simulated crossover (recombination) and mutation operations.

This approach is particularly suited to the massive search spaces presented by make-on-demand chemical libraries, which now contain billions of readily available compounds [5]. The core strength of evolutionary architectures lies in their ability to navigate this complexity without exhaustive enumeration, making them indispensable for modern, AI-driven discovery platforms that aim to compress traditional research and development timelines from years to months [27].

Application Notes & Quantitative Benchmarks

Key Applications in the Drug Discovery Pipeline

Evolutionary algorithms are deployed across multiple stages of the drug discovery pipeline, delivering significant gains in efficiency and success rates.

- Ultra-Large Virtual Screening: Traditional virtual high-throughput screening (vHTS) of billion-molecule libraries is computationally prohibitive, especially when incorporating essential ligand and receptor flexibility. Evolutionary algorithms like REvoLd (RosettaEvolutionaryLigand) efficiently search combinatorial make-on-demand chemical space by exploiting their modular construction from substrates and reactions, achieving hit rate improvements by factors between 869 and 1622 compared to random selection [5].

- De Novo Molecular Design: Algorithms such as Galileo and SpaceGA optimize molecules within a defined combinatorial chemical space. They use mutation and crossover rules to evolve novel molecular structures that maximize a multi-objective fitness function, balancing potency, selectivity, and synthetic accessibility [5]. This mirrors the developmental evolutionary process by exploring a wide phenotype space (chemical structures) to find adaptations (viable drugs) suited to an environment (the biological target).

- Clinical Trial Optimization: Beyond discovery, evolutionary principles are applied through Bayesian causal AI in clinical trial design. These models adapt trial parameters in real-time based on emerging patient response data, effectively "evolving" more efficient and precise trial protocols, thereby raising success rates and reducing costs [28].

Performance Benchmarking

The following tables summarize quantitative performance data for evolutionary algorithms against traditional methods.

Table 1: Performance of REvoLd in Ultra-Large Library Docking [5]

| Drug Target | Hit Rate Enrichment vs. Random | Approximate Unique Molecules Docked |

|---|---|---|

| Target 1 | 1622x | 49,000 - 76,000 |

| Target 2 | 869x | 49,000 - 76,000 |

| Target 3 | 1215x | 49,000 - 76,000 |

| Target 4 | 1450x | 49,000 - 76,000 |

| Target 5 | 1100x | 49,000 - 76,000 |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Algorithm Frameworks [5] [29]

| Algorithm / Framework | Primary Application | Key Metric | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| REvoLd | Flexible Protein-Ligand Docking | Hit Rate Enrichment | 869x - 1622x improvement |

| Galileo | Chemical Space Optimization | Fitness Convergence | Mixed success in pharmacophore optimization |

| GP-CEA | Scheduling (Analogous to Multi-parameter Optimization) | Hypervolume (HV) Metric | Superior on ~59.4% of instances |

| ParadisEO (C++) | General Optimization | Energy Efficiency (η = fitness/kWh) | Highest algorithmic productivity [29] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: REvoLd for Ultra-Large Virtual Screening

This protocol details the use of the REvoLd evolutionary algorithm for structure-based hit identification within the Enamine REAL chemical space [5].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for REvoLd Protocol

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Enamine REAL Space | Make-on-demand combinatorial library of billions of compounds, constructed from lists of substrates and chemical reactions. Serves as the search space [5]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Macromolecular modeling software; provides the RosettaLigand flexible docking protocol and the REvoLd application [5]. |

| Prepared Protein Target | A 3D structure of the drug target (e.g., a kinase), prepared for docking by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and defining the binding site. |

| High-Per Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computational resources necessary for running multiple parallel evolutionary searches with flexible docking. |

II. Step-by-Step Workflow

Problem Setup & Parameter Initialization

- Define the target protein structure and the binding site coordinates.

- Configure the REvoLd hyperparameters:

population_size: 200 individuals.generations: 30.selection_cutoff: 50 top individuals selected for reproduction.

- These parameters were optimized to balance exploration of chemical space and convergence speed [5].

Initial Population Generation

- The algorithm generates an initial random population of 200 ligands by combinatorially assembling available substrates and reactions from the Enamine REAL library.

Fitness Evaluation

- Each ligand in the population is docked into the target's binding site using the RosettaLigand protocol, which accounts for full ligand and receptor flexibility.

- The Rosetta docking score (in Rosetta Energy Units, REU) is assigned as the primary fitness metric; a lower score indicates more favorable binding.

Evolutionary Optimization Loop (Repeat for 30 generations)

- Selection: The top 50 scoring ligands from the current population are selected as parents.

- Reproduction (Crossover): Pairs of parent ligands are recombined. This involves swapping molecular fragments between them to create new offspring ligands.

- Mutation: Offspring ligands undergo mutation. REvoLd uses specialized mutation steps:

- Fragment switching to low-similarity alternatives.

- Changing the core reaction of the molecule to explore diverse scaffolds.

- Elitism: The best-performing individuals can be carried forward to maintain high fitness.

- Evaluation: The new generation of offspring and mutants is evaluated via flexible docking.

Output and Analysis

- After 30 generations, the algorithm outputs all unique, high-scoring molecules discovered during its run.

- It is recommended to perform 20 independent runs with different random seeds to maximize the diversity of discovered hits [5].

- The final list of candidates is prioritized for in vitro testing.

Protocol 2: Genetic Programming for Predictive Model Evolution

This protocol employs Genetic Programming (GP) as a hyper-heuristic to evolve problem-specific predictive models or dispatching rules, a method applicable to complex optimization tasks in drug discovery, such as multi-parameter candidate prioritization [30].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for GP Protocol

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Training Dataset | A curated dataset relevant to the problem (e.g., molecular structures with associated bioactivity or ADMET properties). |

| GP Framework | Software such as DEAP (Python) or ECJ (Java) for implementing genetic programming. |

| Terminal & Function Set | A set of primitive functions (e.g., +, -, *, /, log) and terminals (e.g., molecular descriptors, constants) from which models are built. |

| Fitness Function | A defined metric (e.g., predictive accuracy on a test set, Matthews Correlation Coefficient) to evaluate model quality. |

II. Step-by-Step Workflow

Initialization

- Define the terminal set (e.g., molecular weight, logP, number of hydrogen bond donors) and the function set (e.g., arithmetic operators, logical operators).

- Specify GP run parameters: population size (e.g., 500), number of generations, and crossover/mutation rates.

Population Generation

- Generate an initial population of 500 randomly constructed computer programs (model trees) using the defined function and terminal sets.

Fitness Evaluation

- Execute each evolved program in the population to make predictions on the training dataset.

- Calculate the fitness of each program based on the predefined fitness function (e.g., minimizing the root mean square error).

Evolutionary Loop

- Selection: Use a selection method (e.g., tournament selection) to choose fitter programs as parents.

- Crossover: Swap random subtrees between pairs of parent programs to create offspring.

- Mutation: Randomly alter a subtree in an offspring program to introduce new genetic material.

- This loop continues for the specified number of generations.

Result Extraction

- After the final generation, the best-performing model (the one with the highest fitness) is extracted from the population.

- The model is validated on a held-out test set to ensure its generalizability.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section catalogues critical software, data resources, and algorithmic frameworks for implementing evolutionary architectures in drug discovery.

Table 5: Essential Tools for Evolutionary Drug Discovery

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Access / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | Modeling Software | Provides the REvoLd application for flexible protein-ligand docking within evolutionary searches [5]. | https://www.rosettacommons.org/ |

| Enamine REAL Space | Chemical Library | An ultra-large, make-on-demand combinatorial library of billions of compounds; serves as the primary search space for algorithms like REvoLd [5]. | https://enamine.net/compound-libraries |

| DEAP (Python) | Algorithm Framework | A widely-used library for rapid prototyping of Evolutionary Algorithms and Genetic Programming [29]. | https://github.com/DEAP/deap |

| ParadisEO (C++) | Algorithm Framework | A powerful C++ framework for metaheuristics; shown to have high energy efficiency (fitness/kWh) in evolutionary computations [29]. | http://paradiseo.gforge.inria.fr/ |

| IBM Watson | AI Platform | An example of a commercial AI system applied to analyze medical data and suggest treatment strategies, illustrating the integration of advanced AI in pharmacology [31]. | Commercial Platform |

| ADMET Predictor | Predictive Software | Uses neural networks and other AI methods to predict critical pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties of compounds, often used as a fitness function [31]. | Commercial Software |

The process of drug discovery faces a fundamental challenge: navigating an astronomically vast chemical space, estimated to contain up to 10^60 drug-like molecular entities, to find compounds with specific therapeutic properties [32]. De novo molecular design represents a paradigm shift, moving beyond the screening of existing compound libraries to the computational generation of novel, optimized drug candidates from scratch. Framed within the research on simulating developmental evolution with algorithms, these methods treat molecular discovery as an evolutionary optimization process. Generative deep learning models and evolutionary algorithms act as the "selection pressure," exploring the chemical fitness landscape to evolve populations of candidate molecules with desired bioactivity, synthesizability, and drug-like properties [33]. This approach raises the level of generality from finding specific solutions (a single molecule) to discovering algorithms that can generate families of solutions, embodying the core principle of hyper-heuristic research in evolutionary computation [34].

Next-Generation Platforms for Molecular Design

Recent advances have produced several sophisticated computational platforms that operationalize this evolutionary design concept. The table below summarizes the architecture and application of three key approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced De Novo Molecular Design Platforms

| Platform Name | Core Architecture | Molecular Representation | Design Approach | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DrugGEN [35] [36] [37] | Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) with Graph Transformer layers | Molecular Graphs | Target-specific generative adversarial learning | Design of AKT1 protein inhibitors for cancer |

| DRAGONFLY [38] | Graph Transformer + LSTM-based Chemical Language Model | Molecular Graphs & SMILES strings | Interactome-based, "zero-shot" learning | Generation of PPARγ partial agonists |

| GP-CEA [30] | Genetic Programming-based Cooperative Evolutionary Algorithm | Problem-specific Terminal Nodes | Hyper-heuristic evolution of dispatching rules | Automated design of scheduling algorithms (paradigm illustration) |

DrugGEN: Target-Centric Generation with Graph Transformers

The DrugGEN system exemplifies an end-to-end generative approach for designing target-specific drug candidates [35] [37]. Its architecture is modeled after a competitive co-evolutionary process where a Generator network creates candidate molecules (a population) and a Discriminator network evaluates them, providing selective pressure towards molecules that resemble known bioactive compounds for a specific protein target [36].

Experimental Protocol: Training and Validating DrugGEN

- Data Curation: Assemble two datasets.

- Model Training: Train the GAN with graph transformer layers. The generator learns to transform input molecular graphs into novel candidates that are indistinguishable from real inhibitors by the discriminator [35].

- In Silico Validation:

- Experimental Validation:

DRAGONFLY: Interactome-Based "Zero-Shot" Design

The DRAGONFLY framework leverages deep interactome learning, capitalizing on the network of interactions between ligands and their macromolecular targets [38]. This approach avoids the need for application-specific reinforcement or transfer learning. It processes either a small-molecule ligand template or a 3D protein binding site as a graph, which is then translated into a SMILES string representing a novel molecule with the desired properties [38].

Experimental Protocol: Prospective Validation with DRAGONFLY

- Interactome Construction: Build a graph where nodes represent bioactive ligands and protein targets, with edges denoting high-affinity interactions (≤ 200 nM) from databases like ChEMBL [38].

- Model Application: Input the target binding site (e.g., for PPARγ) into the pre-trained DRAGONFLY model to generate a library of candidate molecules.

- In Silico Triage: Rank generated molecules based on predicted synthesizability (e.g., Retrosynthetic Accessibility Score), structural novelty, and on-target bioactivity predicted by QSAR models [38].

- Prospective Experimental Characterization:

- Chemically synthesize the top-ranking de novo designs.

- Characterize compounds through binding assays, functional cellular assays, and selectivity profiling against related targets.

- Determine the crystal structure of the ligand-receptor complex to confirm the anticipated binding mode, providing ultimate validation of the design rationale [38].

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and workflow of these target-aware generative models.

The Evolutionary Computation Backbone: Hyper-Heuristics for Algorithm Design

Underpinning advanced molecular generators is the evolutionary computation concept of hyper-heuristics—algorithms that automatically design or configure other algorithms [34]. This mirrors a meta-evolutionary process where the unit of selection is not a molecule, but a problem-solving strategy itself.

A Genetic Programming-based Cooperative Evolutionary Algorithm (GP-CEA), for instance, can evolve a set of high-quality, problem-specific dispatching rules (DRs) [30]. In a molecular design context, these rules could govern how molecular fragments are assembled and optimized. The process involves a training stage where genetic programming evolves heuristic rules through population iterations, and a testing stage where these rules are applied to generate novel solutions [30]. This demonstrates the core thesis of simulating developmental evolution: by defining an appropriate set of primitives (e.g., molecular fragments, reaction rules), evolutionary algorithms can combine them in novel, Turing-complete ways to create highly effective, domain-specific design algorithms [34].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of De Novo Generated Molecules

| Evaluation Metric | Methodology | Application Example | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted Bioactivity | QSAR Models (Kernel Ridge Regression) using ECFP4, CATS, USRCAT descriptors [38] | DRAGONFLY generated molecules | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) ≤ 0.6 for pIC50 prediction for 1265 targets [38] |

| Synthesizability | Retrosynthetic Accessibility Score (RAScore) [38] | Prioritization of molecules for synthesis | High correlation between desired and generated molecular properties (r ≥ 0.95) [38] |

| Binding Affinity & Mode | Molecular Docking & Molecular Dynamics Simulations [35] [37] | DrugGEN molecules targeting AKT1 | Effective binding to the target protein confirmed [35] |

| In Vitro Potency | Enzymatic Inhibition Assays (IC50 determination) [35] | Synthesized DrugGEN compounds | Low micromolar inhibition of AKT1 [35] |

| Selectivity Profile | Biochemical & Biophyscial Characterization against related targets [38] | DRAGONFLY designed PPARγ agonists | Favorable activity and desired selectivity profiles achieved [38] |