Reconstructing Gene Networks from QTL Data: Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

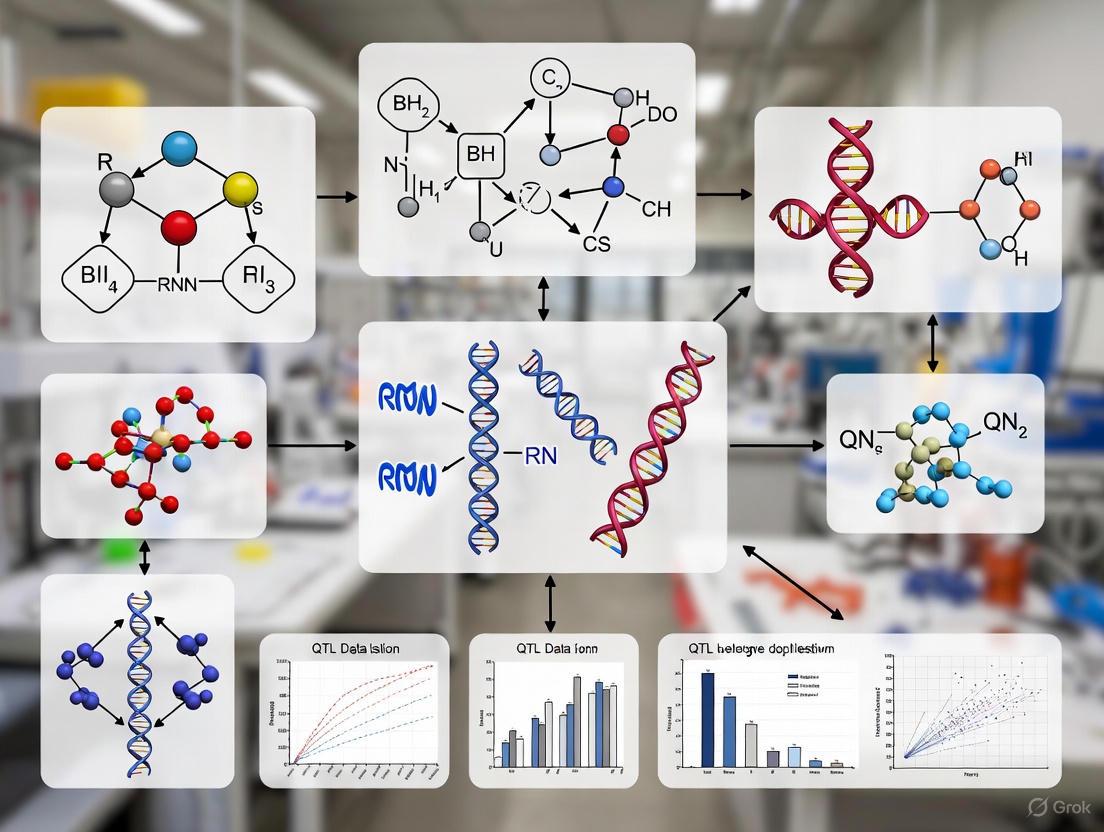

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern computational strategies for reconstructing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) from Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) data.

Reconstructing Gene Networks from QTL Data: Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern computational strategies for reconstructing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) from Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) data. It explores the foundational principles of QTL mapping and network inference, details cutting-edge methodologies that integrate multi-omics data, addresses common challenges and optimization techniques for robust network reconstruction, and discusses validation and comparative analysis frameworks. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent advances to empower the identification of causal genetic variants and their regulatory mechanisms underlying complex traits and diseases.

The Building Blocks: Understanding QTLs and Gene Network Fundamentals

Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) mapping is a foundational statistical method for identifying regions of the genome associated with complex traits that exhibit continuous variation, such as height, yield, or disease susceptibility [1]. Unlike traits controlled by a single gene, complex traits are influenced by multiple genetic loci (QTLs), environmental factors, and their interactions [2]. The core principle of QTL mapping involves analyzing the co-segregation of molecular markers and phenotypic traits within a mapping population to pinpoint chromosomal regions that explain a significant portion of the observed phenotypic variance [2] [1].

The process establishes a crucial link between genotype and phenotype, providing a powerful framework for annotating genetic variants with functional effects [1]. This is particularly valuable for understanding the genetic architecture of complex diseases and agronomically important traits, enabling researchers to move beyond mere correlation to identify potential causal mechanisms [1]. As a result, QTL mapping has become an indispensable tool in diverse fields, from medical research investigating complex diseases to agrigenomics aimed at improving crop yields and livestock productivity [1].

Fundamental Principles and Experimental Design

Core Mathematical Framework

The statistical foundation of QTL mapping often relies on likelihood-based methods, such as interval mapping, which tests for a putative QTL at multiple positions along the genome [3] [2]. The likelihood of a QTL genotype given the observed phenotype and marker data can be modeled as:

[L(QTL\ genotype | phenotype,\ marker\ data) = \frac{P(phenotype | QTL\ genotype) \times P(QTL\ genotype | marker\ data)}{P(phenotype)}]

Where:

- (P(phenotype | QTL\ genotype)) is the probability of the phenotype given the QTL genotype.

- (P(QTL\ genotype | marker\ data)) is the probability of the QTL genotype given the marker data.

- (P(phenotype)) is the probability of the phenotype [2].

Designing a QTL Mapping Experiment

A well-designed experiment is critical for successfully identifying QTLs with high accuracy and precision. The key principles of experimental design for QTL mapping include [2]:

- Large sample size: A sufficient number of individuals is required to detect QTLs with moderate to large effects.

- High marker density: A dense set of genetic markers is necessary to achieve complete genome coverage and detect QTLs.

- Accurate phenotyping: Precise and reliable measurement of the trait of interest is essential.

- Controlled environment: Environmental factors should be standardized to minimize their impact on the trait.

Table 1: Common Types of Mapping Populations in QTL Analysis

| Population Type | Description | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| F₂ Population | Derived from crossing two parental lines and then intercrossing the F₁ offspring. | Commonly used; individuals are genetically heterogeneous. |

| Backcross (BC) Population | Created by crossing an F₁ individual back to one of the parental lines. | Simplifies analysis by reducing heterozygosity. |

| Recombinant Inbred Lines (RILs) | Generated by repeated selfing or sib-mating of F₂ individuals over multiple generations. | Lines are nearly homozygous, allowing for replicated phenotyping. |

| Multiparent Advanced Generation Inter-Cross (MAGIC) | Involves intercrossing multiple parental lines to generate a diverse set of recombinant lines. | Captures greater genetic diversity and increases mapping resolution. |

The choice of mapping population depends on the organism, the trait of interest, and the specific research question [2]. For instance, a 2025 study on Luciobarbus brachycephalus (Aral barbel) used an F₁ full-sib family comprising 165 progenies, along with the male and female parents, to construct a high-density genetic map [4].

Advanced QTL Mapping Techniques and Protocols

High-Density Linkage Map Construction Using Whole-Genome Resequencing

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have dramatically advanced QTL mapping by enabling the construction of ultra-high-density genetic maps. The following workflow, based on a 2025 study in Luciobarbus brachycephalus, details this protocol [4]:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Population Design and Tissue Collection:

- Establish a mapping population from phenotypically distinct parents. The referenced study used Luciobarbus brachycephalus parents with yellow and red body coloration to generate an F₁ full-sib family [4].

- Raise 165 progeny under controlled aquaculture conditions (e.g., water temperature 25.0 °C ± 0.5 °C, dissolved oxygen >6.0 mg/L) [4].

- After a growth period (e.g., 10 months), anesthetize specimens and collect tissue samples (e.g., white skeletal muscle). Flash-freeze samples immediately in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C [4].

High-Quality Phenotyping:

- Collect precise morphometric measurements for the traits of interest. Adhere to established standards (e.g., Chinese National Standard GBT 18654.3–2008) [4].

- Record measurements such as Body Weight (BW), Total Length (TL), Body Length (BL), Body Height (BH), Preanal Body Length (PBL), and Fork Length (FL) using calibrated digital instruments [4].

- Perform Pearson correlation analysis to assess relationships among traits, which may indicate shared genetic regulation (pleiotropy) [4].

Whole-Genome resequencing (WGRS) and Genotyping:

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA from all parents and progeny.

- Prepare sequencing libraries and perform whole-genome sequencing on an appropriate NGS platform to achieve sufficient coverage.

- Align sequence reads to a reference genome and perform genome-wide variant calling to identify high-quality single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The 2025 study identified 164,435 high-quality SNPs for map construction [4].

Linkage Map Construction and QTL Analysis:

- Construct a high-density genetic linkage map using the identified SNPs. The cited study created a map spanning 50 linkage groups with a total genetic distance of 6,425.95 cM and an average marker density of 0.10 cM [4].

- Perform genome-wide QTL scanning using interval mapping or composite interval mapping methods. Calculate Logarithm of Odds (LOD) scores to identify genomic regions where the QTL effect is statistically significant.

- Identify putative candidate genes by examining the genomic intervals underlying significant QTL peaks.

Expression QTL (eQTL) Mapping in Specific Cellular Contexts

Many disease-associated genetic variants function in a context-specific manner. Mapping eQTLs under stimulated conditions can reveal regulatory mechanisms missed in standard approaches [5]. The following protocol is adapted from a 2025 Nature Communications study using iPSC-derived macrophages [5]:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Cell Culture and Differentiation:

Multi-Condition Stimulation and RNA Sequencing:

- Apply a panel of relevant stimuli to the differentiated cells. The referenced study used ten different immune stimuli (e.g., IFNγ, IL-4, LPS) at two timepoints (6h and 24h), resulting in 24 distinct cellular conditions [5].

- Collect samples for RNA-seq from all conditions, including unstimulated controls. Use a low-input RNA-seq protocol if cell numbers are limited. The study generated 4,698 high-quality RNA-seq libraries [5].

Genetic Regulation Analysis:

- Perform cis-eQTL mapping for each condition independently (±1 Mb from the transcription start site) using genotyping data (from arrays or WGS) and gene expression matrices [5].

- To identify response eQTLs (reQTLs)—variants whose regulatory effect changes significantly upon stimulation—use a statistical model like

mashrthat compares eQTL effect sizes across conditions against a defined baseline (e.g., unstimulated cells) [5].

Integration with Complex Disease:

- Perform colocalization analysis between reQTL signals and genome-wide association study (GWAS) hits for relevant diseases to nominate effector genes and potential mechanisms [5].

Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for QTL Mapping

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Mapping Population | Provides the genetic material for analyzing trait and marker segregation. | F₁ full-sib family of L. brachycephalus (n=165) for growth trait analysis [4]. |

| DNA Sequencing Kit | Prepares libraries for whole-genome or reduced-representation sequencing. | Whole-genome resequencing for high-density SNP discovery [4]. |

| RNA Sequencing Kit | Profiles transcriptome-wide gene expression levels. | RNA-seq of iPSC-derived macrophages across 24 stimulation conditions for eQTL mapping [5]. |

| Phenotyping Equipment | Accurately measures quantitative traits of interest. | Digital calipers for precise morphometric measurements in fish [4]. |

| QTL Analysis Software | Performs statistical genetic analyses, including linkage map construction and QTL detection. | R/qtl, QTL Cartographer for interval mapping and multiple QTL modeling [2]. |

Quantitative Data and Analysis Outputs

Performance Metrics in Recent QTL Studies

Table 3: Key Metrics from Recent QTL Mapping Studies

| Study / Organism | Mapping Approach | Population Size | Key Result / Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luciobarbus brachycephalus (Aral barbel) [4] | WGRS-based linkage mapping | 165 F₁ progeny | 164,435 SNPs mapped to 50 LGs; QTL for body weight on LG20, LG26 (PVE: 6.27-39.36%). |

| Human iPSC-derived macrophages [5] | Context-specific eQTL mapping | 209 donor lines, 24 conditions | 10,170 unique eGenes identified; 1.11% of response eQTLs (reQTLs) were condition-specific. |

| Three-spined stickleback [6] | Spectral network QTL (snQTL) | Not Specified | Identified chromosomal regions affecting gene co-expression networks, overcoming multiple testing challenges. |

Expanding the QTL Toolkit for Gene Networks

The standard QTL framework has been extended to investigate the genetic architecture of molecular networks:

- snQTL (Spectral Network QTL): A novel method that maps genetic loci affecting entire gene co-expression networks. It uses a tensor-based spectral statistic to test the association between a genetic variant and the joint differential network, thereby avoiding the massive multiple testing burden of analyzing individual gene pairs [6].

- co-QTL / aQTL: These methods aim to identify genetic variants that influence the coordination (co-expression) between pairs of genes or overall gene activity scores derived from networks [6].

These network-based QTL analyses provide a deeper understanding of the genotype → network → phenotype mechanism, revealing how genetic variants can alter global regulatory architecture rather than just the expression of individual genes [6].

The transition from identifying quantitative trait loci (QTL) to reconstructing global gene networks represents a paradigm shift in genetics research. While QTL mapping successfully pinpoints genomic regions associated with phenotypic variation, it often leaves the underlying gene-gene interaction networks unresolved. Systems genetics bridges this gap by integrating QTL data with high-throughput genomic technologies to model complex biological systems as interconnected networks, enabling researchers to move from correlation to causation in understanding disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets [7]. This approach has become increasingly powerful with advances in machine learning and the availability of diverse gene expression datasets, including microarray, RNA-seq, and single-cell RNA-seq data [7].

The conceptual framework involves reconstructing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) where genes, proteins, and other molecules interact through complex networks. At the heart of these networks are transcription factors—specialized proteins that interact with specific DNA regions to control gene activation or repression [7]. This process of gene expression regulation creates intricate feedback loops where genes mutually inhibit or activate one another, allowing cellular processes to be exquisitely fine-tuned in response to internal signals and external stimuli [7].

Key Analytical Frameworks and Data Types

QTL Mapping Foundations

R/qtl provides the essential computational environment for initial QTL mapping, implementing hidden Markov model (HMM) algorithms for dealing with missing genotype data in experimental crosses [8]. This software enables the identification of genetic loci associated with complex traits through several core functionalities:

- Genetic map estimation and genotyping error identification

- Single-QTL genome scans using interval mapping, Haley-Knott regression, and multiple imputation

- Two-dimensional genome scans for detecting epistatic interactions between loci

- Covariate integration to account for variables such as sex, age, or treatment effects

The current version (1.72 as of 2025-11-19) supports backcrosses, intercrosses, and phase-known four-way crosses, providing the statistical foundation for subsequent network reconstruction [8].

Network Reconstruction Models

Gene regulatory network reconstruction employs multiple modeling approaches, each with distinct strengths and applications in systems genetics:

Table 1: Gene Network Modeling Approaches

| Model Type | Key Characteristics | Applications | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topological Models | Graph-based representation of gene connections | Protein-protein interaction networks, coexpression networks | Static interaction data |

| Control Logic Models | Captures regulatory significance of dependencies | Identifying specific regulatory interactions | Limited knowledge contexts |

| Dynamic Models | Describes temporal fluctuations in system state | Predicting network response to environmental changes | Time-series expression data |

| Machine Learning Models | Algorithmic prediction of regulatory behavior | Large-scale network inference from diverse data types | Multi-omics datasets |

These models can be understood as existing on a spectrum from architectural depiction of entire genomes to detailed simulation of few-gene dynamics [7]. Logical models provide straightforward approaches when knowledge is limited, while dynamic models represent conventional techniques for modeling temporal gene network behavior developed before the contemporary genomic period [7].

Integrated Protocol: From QTL Mapping to Network Reconstruction

Stage 1: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Materials and Reagents:

- Experimental Organism: Appropriate model system (e.g., mouse, rat, or yeast crosses) with genetic diversity

- Genotyping Platform: Microarray or next-generation sequencing reagents for genome-wide marker identification

- RNA Extraction Kit: High-quality RNA isolation materials (e.g., TRIzol or column-based kits)

- Expression Profiling Technology: Microarray chips or RNA-seq library preparation reagents

Protocol Steps:

Cross Design and Population Establishment

- Implement appropriate crossing scheme (backcross, F2 intercross, or recombinant inbred lines)

- Ensure sufficient sample size (typically 100-1000 individuals) for statistical power

- Record relevant covariates (sex, age, treatment conditions)

Phenotypic and Molecular Data Collection

- Measure target quantitative traits with technical replicates

- Extract genomic DNA for high-density genotyping

- Isolve RNA from relevant tissues under standardized conditions

- Perform gene expression profiling using microarray or RNA-seq

Data Quality Control and Normalization

Stage 2: QTL Analysis and Candidate Gene Identification

Materials and Software:

- R/qtl Package: Install current version (1.72) from CRAN [8]

- Computational Resources: Workstation with sufficient RAM (≥16GB) for genome scans

- GeneNetwork Access: Web-based resource for integrative analysis [9]

Protocol Steps:

Initial Genome Scan

- Calculate genotype probabilities using

calc.genoprob()function - Perform single-QTL scan with

scanone()using appropriate method (EM algorithm, Haley-Knott regression, or multiple imputation) - Establish significance thresholds through permutation tests (n=1000)

- Calculate genotype probabilities using

Advanced QTL Mapping

- Conduct two-dimensional scan with

scantwo()to detect epistatic interactions - Incorporate covariates using the

addcovarorintcovarparameters - Perform binary trait analysis when applicable using

scanone.binary()

- Conduct two-dimensional scan with

Expression QTL (eQTL) Mapping

- Map expression levels as quantitative traits to identify regulatory loci

- Distinguish cis-eQTL (local regulation) from trans-eQTL (distant regulation)

- Use GeneNetwork advanced queries for specific patterns:

Stage 3: Network Inference and Validation

Materials and Software:

- Network Inference Tools: R packages for mutual information, Bayesian networks, or correlation networks

- Visualization Software: Cytoscape for network exploration and display

- Validation Reagents: CRISPR/Cas9 components for experimental validation of predicted interactions

Protocol Steps:

Data Integration for Network Inference

- Combine eQTL data with protein-protein interaction databases

- Incorporate prior knowledge from transcription factor binding databases

- Integrate multi-omics datasets where available (epigenomic, proteomic)

Network Reconstruction Using Machine Learning

- Select appropriate algorithm based on data characteristics and research question:

- Random Forests for handling non-linear relationships

- Bayesian Networks for modeling causal relationships

- Regularized Regression for large-scale network inference

- Optimize model parameters through cross-validation

- Assess network stability using bootstrap procedures

- Select appropriate algorithm based on data characteristics and research question:

Network Validation and Interpretation

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on network modules

- Validate key predictions experimentally using perturbation approaches

- Compare network topology properties (degree distribution, centrality) to random networks

- Integrate disease-associated genes from public databases for translational insights

Visualization and Computational Implementation

Workflow Diagram

Network Inference Logic

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| R/qtl Software | QTL mapping in experimental crosses | Initial genetic locus identification [8] |

| GeneNetwork | Integrative genetic analysis platform | eQTL mapping and network queries [9] |

| RNA-seq Reagents | High-throughput transcriptome profiling | Gene expression quantification for network edges [7] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Targeted genome editing | Experimental validation of predicted gene interactions [7] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq Kit | Cell-type-specific expression profiling | Resolution of cell-type-specific networks [7] |

| Bayesian Network Software | Causal network inference | Directional relationship prediction between genes [7] |

Data Integration and Interpretation

Quantitative Data Standards

Table 3: Key Quantitative Metrics in QTL and Network Analysis

| Metric | Interpretation | Threshold Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| LOD Score | Strength of QTL evidence | Significant: ≥3.0, Suggestive: ≥2.0 [9] |

| cisLRS | Local expression QTL evidence | Significant: ≥15 within 5Mb window [9] |

| transLRS | Distant expression QTL evidence | Significant: ≥15 outside 5Mb exclusion zone [9] |

| Contrast Ratio | Visualization accessibility | Minimum 4.5:1 for large text, 7:1 for standard text [10] |

| Network Density | Connectivity of reconstructed graph | Disease networks often show higher density than random |

Advanced Analytical Considerations

For perturbation experiments essential for causal inference, datasets containing gene expression measurements from gene knockouts or drug treatments provide valuable information about causal relationships and gene-gene interactions [7]. Time-series expression data available through resources like DREAM Challenges enable researchers to study changes in gene expression over time to infer dynamic gene regulatory networks and identify regulatory relationships based on temporal patterns [7].

The integration of multi-omics datasets establishes a more complete picture of gene regulation by combining information on transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics [7]. This integrative approach is particularly powerful for distinguishing direct from indirect regulatory relationships in reconstructed networks, addressing a fundamental challenge in systems genetics.

A central challenge in modern genetics is explaining how genetic variation identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) ultimately manifests as complex traits and diseases. The majority of disease-associated variants lie in non-coding regions of the genome, suggesting they exert their effects through regulatory mechanisms rather than directly altering protein structure [11]. This realization has propelled the adoption of molecular quantitative trait locus (QTL) analyses, which map genetic variants to intermediate molecular phenotypes, thereby bridging the gap between genotype and organism-level traits.

Two particularly powerful approaches in this domain are expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) and methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTL) analyses. eQTLs identify genetic variants associated with changes in gene expression levels [12], while meQTLs pinpoint variants that influence DNA methylation patterns at specific CpG sites [13]. When integrated together with genotype data, these data types provide a multi-layered view of the regulatory architecture underlying complex traits, enabling researchers to reconstruct the causal pathways from genetic variation to disease susceptibility.

This Application Note provides a comprehensive framework for integrating genotype, eQTL, and meQTL data to reconstruct gene regulatory networks, with specific protocols for study design, data analysis, and experimental validation.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL)

An eQTL is a genetic locus that explains a portion of the genetic variance in gene expression levels. eQTLs are typically categorized based on their genomic position relative to the gene they regulate:

- cis-eQTLs: Variants located within 1 megabase (Mb) on either side of a gene's transcription start site (TSS) [11]. These are often considered to have direct regulatory effects on the nearby gene.

- trans-eQTLs: Variants located at least 5 Mb downstream or upstream of the TSS or on a different chromosome [11]. These typically exert their effects through intermediate molecules such as transcription factors.

Most regulatory control occurs locally, with early studies detecting thousands of genes with significant cis-eQTLs [11]. However, as sample sizes in studies have increased, researchers have identified hundreds to thousands of replicated trans-eQTLs, which tend to be highly tissue-specific [11].

Methylation Quantitative Trait Loci (meQTL)

meQTLs are genetic variants associated with variation in DNA methylation levels at specific CpG sites [13]. As DNA methylation is a key epigenetic mechanism that can suppress gene transcription by modifying chromatin structure [13], meQTLs provide critical insights into how genetic variation can influence gene regulation through epigenetic modifications.

The functional interpretation of meQTLs is particularly valuable when the CpG sites they regulate are located in promoter regions, as these modifications can directly influence gene expression and potentially contribute to disease pathogenesis [13].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Molecular QTL Types

| QTL Type | Molecular Phenotype | Regulatory Impact | Typical Mapping Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| cis-eQTL | Gene expression level | Direct transcriptional regulation | Within 1 Mb of gene TSS |

| trans-eQTL | Gene expression level | Indirect regulation through intermediates | >5 Mb from TSS or different chromosome |

| meQTL | DNA methylation level | Epigenetic regulation of gene expression | Variable, often cis-acting |

Experimental Design and Data Collection Protocols

Study Design Considerations

Sample Size and Power Requirements: Large sample sizes are critical for robust QTL mapping. The eQTLGen consortium achieved substantial power by including 31,684 individuals, enabling comprehensive detection of both cis- and trans-eQTLs in blood [14]. For tissue-specific studies, the GTEx project analyzed 54 non-diseased tissues from over 1,000 individuals [14]. While meQTL studies can be effective with smaller sample sizes (e.g., 223 lung tissue samples in GTEx Lung meQTL dataset) [13], larger cohorts increase detection power for context-specific effects.

Tissue and Context Selection: Regulatory genetic effects demonstrate significant context specificity. The GTEx study revealed that eQTL detection follows a U-shaped curve—they tend to be either highly tissue-specific or broadly shared across many tissues [14]. When designing your study, consider:

- Tissue relevance: Select tissues physiologically relevant to your trait of interest. For example, adipose tissue eQTLs show stronger correlation with obesity-related traits than blood eQTLs [11].

- Dynamic contexts: Consider measuring QTLs across multiple conditions, such as during development [14], in response to immune stimuli [14], or drug treatments [14], as many regulatory effects are condition-specific.

Multi-ethnic Representation: Historically, most GWAS and QTL studies have focused on European populations, creating a critical gap in understanding regulatory variation in diverse populations [14]. Studies have shown that 17-29% of loci have significant differences in mean expression levels between population pairs [11]. Whenever possible, include diverse ethnic backgrounds to ensure broader applicability of findings.

Data Generation Protocols

Genotyping and Imputation:

- Use high-density SNP arrays or whole-genome sequencing to capture comprehensive genetic variation

- Perform quality control: remove samples with high missing rates, check sex inconsistencies, exclude related individuals

- Impute to reference panels (e.g., 1000 Genomes) to increase variant coverage

- Apply standard filters: minor allele frequency (MAF > 0.05), Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 1×10⁻⁶), call rate (>95%)

Gene Expression Profiling:

- Bulk RNA-seq: Standard approach for eQTL studies. Provides averaged gene expression across tissues.

- Protocol: Isolate high-quality RNA (RIN > 7), sequence with minimum 30 million reads per sample, 150bp paired-end recommended

- Quantify expression using TPM (transcripts per million) or FPKM values [15]

- Single-cell RNA-seq: Emerging approach that resolves cellular heterogeneity

- Protocol: Fresh tissue dissociation, target cell viability >90%, use platform (10X Genomics recommended)

- Enables identification of cell-type-specific eQTLs [14]

DNA Methylation Profiling:

- Use Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip arrays covering >850,000 CpG sites

- Protocol: Treat DNA with bisulfite conversion, hybridize to arrays, perform quality checks for bisulfite conversion efficiency

- Preprocessing: Normalize data, correct for background noise, remove probes with detection P > 0.01

- β-values calculated as ratio of methylated signal to total signal [13]

Table 2: Essential Public Data Resources for QTL Studies

| Resource | Data Type | Sample Details | Access URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| GTEx Portal | Multi-tissue eQTLs | 54 tissues from >1,000 individuals | https://gtexportal.org/ |

| eQTLGen Consortium | Blood eQTLs | 31,684 individuals | https://eqtlgen.org/ |

| Metabrain | Brain eQTLs | 8,613 RNA-seq samples | https://metabrain.nl/ |

| GTEx Lung meQTL | Lung methylation | 223 lung tissue samples | Available via GTEx Portal |

| TCGA | Multi-omics cancer data | Various cancer types with matched normal | https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/ |

Computational Analysis Workflows

Preprocessing and Quality Control

Genotype Data QC:

Expression Data Normalization:

- Remove lowly expressed genes (TPM < 1 in less than 20% of samples)

- Apply variance-stabilizing transformation or TMM normalization

- Correct for technical covariates: sequencing batch, RIN, library size

- Use PEER or PCA to account for hidden confounding factors [14]

Methylation Data Processing:

- Perform functional normalization using

minfiR package - Remove cross-reactive probes and SNPs-containing probes

- Correct for cell type heterogeneity using reference-based methods

QTL Mapping Protocols

cis-eQTL Mapping: This protocol identifies local regulatory effects using matrix eQTL:

meQTL Mapping: Similar analytical approach applied to methylation data:

Multiple Testing Correction:

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) control using Benjamini-Hochberg procedure

- For genome-wide significance, typical threshold is FDR < 0.05

- Permutation procedures can also be used to establish empirical p-values

Integrated QTL-GWAS Analysis

Colocalization Analysis: This approach tests whether GWAS signals and QTL signals share the same causal variant:

Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization: Uses GWAS and eQTL summary statistics to infer causal relationships between gene expression and traits:

The following diagram illustrates the complete integrated analysis workflow from raw data to biological interpretation:

Case Study: Integrated meQTL-eQTL Analysis in Lung Adenocarcinoma

A recent study on non-smoking lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) provides an exemplary model of integrated QTL analysis [13] [16]. The research demonstrated how combining meQTL and eQTL data can elucidate complete mechanistic pathways from genetic variation to disease risk.

Experimental Findings

The study identified:

- rs939408 as a significant meQTL associated with methylation levels of cg09596674 in the LRRC2 gene (β < 0, P < 0.001) [13]

- A negative correlation between cg09596674 methylation and LRRC2 expression (r = -0.32, P < 0.001) [13]

- The A allele of rs939408 was associated with both decreased methylation and reduced LUAD risk (OR = 0.89, P = 0.019) [13]

- Functional validation showed that increased LRRC2 expression inhibited LUAD malignancy in vitro and suppressed tumor growth in mouse models [13]

Mechanistic Interpretation

This case demonstrates a clear mechanistic pathway: the protective A allele of rs939408 → decreased methylation of cg09596674 → increased LRRC2 expression → reduced cancer risk. This comprehensive mapping from genotype to epigenetic modification to gene expression to disease phenotype showcases the power of integrated QTL analysis.

The following diagram illustrates the established mechanistic pathway from this case study:

Advanced Applications and Emerging Methodologies

Single-cell QTL Mapping

Traditional bulk RNA-seq averages expression across cell types, masking cellular heterogeneity. Single-cell eQTL (sc-eQTL) mapping resolves this limitation:

Experimental Design:

- Profile at least 100 donors with 1,000+ cells per donor recommended

- Cell-type annotation using marker genes or reference-based methods

- Account for technical variation: batch effects, amplification efficiency

Analysis Protocol:

Notable projects include the OneK1k study, which analyzed 1.27 million peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 982 donors and identified thousands of cell-type-specific eQTLs, 19% of which colocalized with GWAS risk variants [14].

Dynamic and Context-specific QTLs

Regulatory effects can vary across developmental stages, environmental exposures, and disease states. Identifying such dynamic QTLs requires longitudinal or multi-condition designs:

Stimulation QTL Studies:

- Measure gene expression before and after immune stimulation [14]

- Treat cells with cytokines, pathogens, or drugs

- Identify response QTLs (response quantitative trait loci)

Disease-specific QTLs:

- Compare QTL effects in healthy vs. diseased tissues

- Example: Liver eQTLs exclusive to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) patients [14]

Drug Target Prioritization

Integrated QTL analysis facilitates drug discovery by:

- Identifying genes whose expression influences disease risk (Mendelian randomization)

- Highlighting potential drug targets with genetic support

- Informing drug repurposing opportunities

A study on liver tissues from MASLD patients identified genotype- and cell-state-specific sc-eQTLs that may offer prospective therapeutic targets [14].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated QTL Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Products/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality DNA for genotyping | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen), PureLink Genomic DNA Kits |

| RNA Preservation | Stabilize RNA for expression studies | RNAlater, PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes |

| Bisulfite Conversion | DNA treatment for methylation analysis | EZ DNA Methylation kits (Zymo Research) |

| Single-cell Isolation | Cell separation for scRNA-seq | Chromium Controller (10X Genomics), BD Rhapsody |

| Genotyping Arrays | Genome-wide SNP profiling | Global Screening Array (Illumina), Infinium Asian Screening Array |

| Methylation Arrays | CpG methylation profiling | Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 (Illumina) |

| QTL Mapping Software | Statistical analysis of QTLs | MatrixEQTL, TensorQTL, QTLtools, fastQTL |

| Colocalization Tools | Integrated GWAS-QTL analysis | COLOC, echolocatoR, hyprcoloc |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Data Quality Issues:

- Low genotype concordance: Check sample swaps using sex chromosomes or known sample relationships

- Batch effects in expression: Include batch as covariate, use ComBat or remove first few principal components

- Methylation array failures: Check bisulfite conversion efficiency, exclude samples with >5% failed probes

Statistical Challenges:

- Multiple testing burden: Use hierarchical testing approaches, prioritize candidate genes

- Confounding: Include genotyping principal components, known covariates, and hidden factors (PEER)

- Cell type heterogeneity: In bulk tissues, estimate cell type proportions and include as covariates

Interpretation Caveats:

- Direction of effects: QTL associations do not imply causality; use additional methods like Mendelian randomization

- Linkage disequilibrium: Fine-mapping approaches (SuSiE, FINEMAP) can help identify causal variants

- Context specificity: Be cautious about generalizing findings across tissues, populations, or environmental contexts

Integrating genotype, eQTL, and meQTL data provides a powerful framework for reconstructing gene regulatory networks and elucidating the functional mechanisms through which genetic variants influence complex traits. The protocols outlined in this Application Note equip researchers with comprehensive methodologies for study design, data generation, computational analysis, and experimental validation.

Future developments in the field will likely focus on increasing resolution through single-cell multi-omics, expanding diversity in study populations, and developing more sophisticated computational methods for causal inference. As demonstrated by the LUAD case study, this integrated approach can successfully bridge the gap between genetic association and biological mechanism, ultimately accelerating the translation of genomic discoveries into therapeutic interventions.

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL) mapping is a foundational technique in systems genetics for linking genetic variation to changes in gene expression, thereby illuminating the regulatory architecture of complex traits. An eQTL is defined by a genetic variant (eSNP) associated with the expression level of a gene (eGene) [17]. Within this framework, a cis-eQTL involves an eSNP located within 1 megabase (Mb) of the transcription start site (TSS) of its associated eGene. In contrast, a trans-eQTL involves an eSNP that is distant from its eGene, typically defined as being more than 5 Mb away or on a different chromosome [17] [18].

trans-eQTL hotspots are a phenomenon of particular interest; these are genomic loci where a single genetic variant (or a set of linked variants) is associated with the expression levels of many distant genes [19]. These hotspots are considered statistical footprints of underlying regulatory networks, often orchestrated by master regulators such as transcription factors or RNA-binding proteins. The distinction between cis- and trans-acting mechanisms, and the identification of trans-hotspots, is therefore critical for moving beyond mere genetic associations to a mechanistic understanding of disease etiology [17] [19].

Comparative Analysis: cis-QTLs vs. trans-QTL Hotspots

The following table summarizes the core characteristics that distinguish cis-QTLs from trans-QTL hotspots, highlighting their unique roles in gene regulatory networks.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of cis-QTLs and trans-QTL Hotspots

| Feature | cis-QTL | trans-QTL Hotspot |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Location | eSNP within 1 Mb of the eGene's TSS [17] [18] | eSNP >5 Mb from eGene or on different chromosome; one locus affects many genes [17] [19] |

| Putative Mechanism | Direct, local effects on gene regulation (e.g., promoter/enhancer variants) [17] | Indirect, mediated through trans-acting factors (e.g., a cis-regulated TF that regulates distant targets) [17] [19] |

| Detection Power | High; readily detected with moderate sample sizes (e.g., hundreds) [18] | Lower; requires large sample sizes (e.g., thousands) for sufficient power [17] |

| Typical Effect Size | Generally larger [17] | Generally smaller [17] |

| Primary Biological Insight | Identifies genes directly influenced by local genetic variation [17] | Reveals higher-order regulatory networks and master regulators [19] |

| Enrichment for GWAS Signals | Yes, provides direct gene-to-variant links | Yes, particularly enriched for disease associations and can implicate new pathways [19] |

Protocol for Identification and Analysis

This section provides a detailed workflow for identifying cis- and trans-QTLs and subsequently reconstructing the regulatory networks underlying trans-eQTL hotspots.

Protocol 1: Genome-wide QTL Mapping

Objective: To identify significant cis- and trans-eQTL associations from genotype and RNA-seq data.

Materials and Input Data:

- Genotype data: Imputed genotype data in VCF (Variant Call Format) or GDS format [20].

- RNA-seq data: Normalized and quality-controlled gene expression matrix (e.g., TPM or FPKM).

- Covariates: Technical (e.g., sequencing batch, RIN) and biological (e.g., age, sex) covariates; genetic principal components to account for population stratification [17] [20].

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Convert genotype files to GDS format. Calculate genetic principal components (PCs) and a Genetic Relationship Matrix (GRM) to account for population structure and relatedness [20].

- Expression Normalization: Normalize the gene expression matrix using quantile normalization, followed by inverse quantile normalization to map expression values to a standard normal distribution. Regress out technical and biological covariates to obtain residual expression values for analysis [17].

- cis-eQTL Mapping: For each gene, test associations between its normalized expression and all genetic variants within a 1 Mb window of its TSS. Use a linear model (e.g., from MatrixeQTL) or a linear mixed-effect model (e.g., from GENESIS) if familial relatedness is present [18] [20].

- trans-eQTL Mapping: Test associations between each gene and all genetic variants located beyond a 5 Mb window from its TSS (both upstream and downstream). Due to the massive multiple testing burden, a stringent significance threshold is required [17].

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply False Discovery Rate (FDR) control. For cis-eQTLs, a standard FDR < 0.05 is typical. For trans-eQTLs, a more lenient FDR (e.g., < 0.25) may be used to define a set of "candidate" associations for downstream validation due to lower power [17].

- Hotspot Identification: Cluster significant trans-eQTL associations by the genomic position of their eSNPs. A genomic locus associated with a statistically significant overabundance of trans-eGenes is classified as a trans-eQTL hotspot [19].

Protocol 2: Network Reconstruction from a trans-QTL Hotspot

Objective: To infer the regulatory network downstream of a identified trans-eQTL hotspot.

Materials and Input Data:

- trans-eQTL Hotspot: A list of significant trans-eGene associations for a specific hotspot locus.

- Biological Priors: Curated data on Transcription Factor (TF) binding motifs, protein-protein interactions (e.g., from BioGrid), and chromatin interaction data (e.g., from Hi-C) [19].

- Multi-omics Data: (Optional) DNA methylation data (meQTL) or other molecular phenotypes from the same samples to constrain network inference [19].

Procedure:

- Identify Candidate Mediator: For the lead eSNP in the hotspot, check for overlap with known cis-eQTLs. A common mechanism is cis-mediation, where the eSNP regulates the expression of a nearby gene (the cis-eGene), which in turn acts as a trans-regulator [17].

- Statistical Mediation Analysis: Perform formal mediation analysis to test if the effect of the trans-eQTL on each trans-eGene is statistically explained by the expression level of the candidate cis-eGene [17].

- Annotate Cis-Mediated Genes: If the cis-eGene is a transcription factor or RNA-binding protein, it is a strong candidate for the master regulator of the hotspot [17].

- Integrate Prior Knowledge: Use manually curated biological prior information (e.g., known TF-target relationships from public databases) to guide the inference of regulatory connections between the candidate master regulator and the trans-eGenes [19].

- Network Inference: Apply state-of-the-art network inference methods (e.g., graphical lasso, BDgraph) that can incorporate these priors to reconstruct the most likely regulatory network underlying the observed trans-associations [19].

- Functional Validation: Link the reconstructed network to disease biology by performing colocalization analysis between the trans-eQTL signals and GWAS loci for relevant diseases (e.g., schizophrenia) [17] [18].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Item/Resource | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| QTLtools [17] | Software | A comprehensive toolkit for QTL mapping in cis and trans, supporting various normalization schemes and permutation testing. |

| yQTL Pipeline [20] | Computational Pipeline | A Nextflow-based pipeline that automates the entire QTL discovery workflow, from data preprocessing to association testing and visualization. |

| GENESIS [20] | Software/R Package | Performs genetic association testing using linear mixed models, accounting for population structure and familial relatedness. |

| BDgraph / glasso [19] | Software/R Package | Network inference methods capable of incorporating continuous biological prior information to reconstruct regulatory networks. |

| Biological Priors (e.g., STRING, BioGrid, Roadmap) [19] | Data Resource | Curated databases of protein-protein interactions, TF-binding motifs, and epigenetic marks used to guide and improve network inference. |

| PsychENCODE / MetaBrain [17] [18] | Data Resource | Large-scale consortium data providing genotype and RNA-seq data from human brain tissues, essential for powering trans-eQTL discovery. |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The strategic differentiation between cis-QTLs and trans-QTL hotspots is paramount for reconstructing gene networks from genetic data. While cis-eQTLs efficiently pinpoint genes of interest, trans-eQTL hotspots reveal the broader regulatory landscape and expose master regulators that would otherwise remain hidden. The protocols outlined here demonstrate that robust trans-eQTL and network analysis is now feasible, though it demands large sample sizes and sophisticated computational methods that integrate multi-omics data and existing biological knowledge [19].

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on the integration of single-cell sequencing data, which can resolve QTL effects to specific cell types, thereby dramatically refining the reconstructed networks [18]. Furthermore, the application of these approaches to diverse populations and a wider range of tissues will be critical for understanding the context-specificity of regulatory networks and for ensuring the broad applicability of findings in therapeutic development.

From Data to Networks: A Guide to Modern Reconstruction Methodologies

The integration of Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) mapping with gene co-expression network analysis represents a powerful systems genetics approach to bridge the gap between genotype and complex phenotype. While traditional QTL mapping identifies chromosomal regions associated with phenotypic variation, it often fails to identify the underlying genes or biological mechanisms [6]. Similarly, gene co-expression networks like those generated through Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) can identify clusters of functionally related genes but may not establish genetic causality [21] [22]. Their integration creates a synergistic framework where QTL mapping provides the genetic anchors while co-expression networks reveal the functional context and regulatory relationships, enabling more efficient candidate gene prioritization and biological mechanism discovery [23] [24].

This integrative approach is particularly valuable for understanding the genetic architecture of complex traits controlled by multiple genes and their interactions. Evidence suggests that genetic variants can broadly alter co-expression network structure, creating footprints in association studies that reflect underlying regulatory networks [6] [19]. Methods like spectral network QTL (snQTL) have emerged to directly map genetic loci affecting entire co-expression networks using tensor-based spectral statistics, overcoming multiple testing challenges inherent in conventional approaches [6]. Meanwhile, the combination of linkage mapping with WGCNA has proven effective for predicting candidate genes for yield-related traits in wheat [23] and growth stages in castor [24].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

QTL Mapping Protocol

Population Development and Genotyping

- Mapping Population Construction: Develop a segregating population suitable for QTL analysis. For plants, this typically involves crossing two parental lines with contrasting phenotypes for your target trait, followed by selfing or backcrossing to generate Recombinant Inbred Lines (RILs), F2, or BC1 populations [23] [24]. Population sizes should provide sufficient power for detection; typically 200-500 individuals are used [23] [24].

- DNA Extraction and Genotyping: Extract genomic DNA using established methods (e.g., CTAB protocol for plants) [24]. Genotype using appropriate marker systems such as SSR markers [24] or SNP arrays [25]. The number of markers should provide adequate genome coverage; for example, 566 SSR markers were used in a castor study [24] while 4,583 SNPs were used in an almond study [25].

Phenotypic Data Collection and QTL Analysis

- Trait Measurement: Record phenotypic measurements for your target traits across environments when possible. For agricultural traits, this may include plant height, spike length, kernel characteristics, flowering time, or seed dormancy [23] [24] [25]. Measure multiple biological replicates to account for environmental variation.

- Linkage Map Construction and QTL Scanning: Construct a genetic linkage map using software such as JoinMap or R/qtl. Perform QTL analysis using Composite Interval Mapping (CIM) or Inclusive Composite Interval Mapping (ICIM) [24]. Apply appropriate significance thresholds (e.g., via permutation tests) to control false discovery rates. Identify both major and minor effect QTLs, noting their physical positions, confidence intervals, and proportion of variance explained [23].

Table 1: Key Parameters for QTL Mapping Populations and Analysis

| Parameter | Specification | Example Values from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Population Types | F2, RILs, BC1, GWAS panels | F2 (282 individuals), BC1 (250 individuals) [24] |

| Marker Systems | SSR, SNP arrays | 566 SSR markers [24]; 4,583 SNPs [25] |

| QTL Methods | CIM, ICIM, interval mapping | CIM, ICIM [24] |

| Significance Testing | Permutation tests, LOD thresholds | 1,000 permutations, LOD ≥ 3.0 |

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) Protocol

Data Preprocessing and Network Construction

- Expression Data Collection: Generate or obtain transcriptome data (RNA-seq or microarray) for the tissues and conditions relevant to your target traits. Ensure adequate sample size; studies typically use 30-100 samples [21] [22]. For paired designs or complex experiments, account for batch effects using appropriate statistical models [21].

- Data Filtering and Normalization: Filter genes with low expression or minimal variation. Typically, retain genes above a minimum expression threshold and select the most variable genes for analysis (e.g., top 5,000-10,000 genes by variance) [22]. Normalize data using appropriate methods (e.g., RMA for microarrays, TPM/FPKM for RNA-seq).

- Network Construction and Module Detection: Calculate pairwise correlations between all genes using Pearson or Spearman correlation. Transform correlations into adjacency matrices using a soft power threshold (β) that approximates scale-free topology [21] [22] [26]. Convert adjacency to Topological Overlap Matrix (TOM) to measure network interconnectedness. Perform hierarchical clustering on TOM-based dissimilarity and identify modules using dynamic tree cutting [22] [26]. Modules are typically assigned color names (e.g., "turquoise," "blue").

Module-Trait Associations and Hub Gene Identification

- Relating Modules to Phenotypes: Calculate module eigengenes (MEs) as the first principal component of each module's expression matrix [21] [22] [26]. Correlate MEs with phenotypic traits of interest. For paired designs or complex experiments, use linear mixed-effects models to account for within-pair correlations or other random effects [21]. Calculate Gene Significance (GS) as the correlation between individual gene expression and traits, and Module Membership (MM) as correlation between gene expression and module eigengenes [21] [22].

- Hub Gene Identification: Identify intramodular hub genes as those with high MM and GS values [22] [26]. Visualize relationships using scatterplots of MM vs. GS. Perform functional enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) on significant modules to interpret biological relevance [22].

Table 2: Essential WGCNA Parameters and Analytical Steps

| Analysis Step | Key Parameters | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Network Construction | Soft thresholding power (β), network type (signed/unsigned) | Select β where scale-free topology fit ≈ 0.8-0.9 [22] [26] |

| Module Detection | Minimum module size, deepSplit, mergeCutHeight | Typical min module size: 20-30 genes; merge similar modules (cutheight ≈ 0.25) [26] |

| Trait Associations | Module-trait correlations, linear mixed models | For paired designs: use LMM to account for within-pair correlations [21] |

| Hub Gene Identification | Module Membership (MM), Gene Significance (GS) | Hub genes have high MM (>0.8) and high GS [22] [26] |

Integration Strategies for QTL and Co-expression Networks

Candidate Gene Prioritization within QTL Regions

- Extract all genes within QTL confidence intervals based on genome annotations. Cross-reference these genes with those in trait-associated co-expression modules [23] [24]. For example, in wheat, this approach identified 29 candidate genes for plant height and 47 for spike length by integrating QTL mapping with WGCNA [23].

- Prioritize genes that are both located in QTL regions and show high connectivity in relevant modules. Further filter candidates based on differential expression analyses between parental lines or extreme phenotypes [24]. Functional annotations and pathway enrichment of these candidate genes provide additional validation.

Network-Driven QTL Validation

- Use co-expression networks to infer biological plausibility for QTL effects. If genes within a QTL region are hub genes in modules associated with the trait, this supports their potential causal role [23] [22].

- For trans-QTL hotspots that affect multiple genes across the genome, reconstruct regulatory networks using prior biological knowledge from databases like BioGrid, GTEx, or Roadmap Epigenomics [19]. Methods such as BDgraph or graphical lasso can incorporate these priors for network inference [19].

Diagram 1: Integrated QTL and WGCNA analysis workflow.

Applications and Case Studies

Plant Growth and Development Traits

The integration of QTL mapping with co-expression networks has been particularly successful in dissecting complex agricultural traits. In wheat, researchers combined QTL mapping for yield-related traits with WGCNA of spike transcriptomes, identifying 29 candidate genes for plant height, 47 for spike length, and 54 for thousand kernel weight [23]. Notably, this approach successfully captured known genes including Rht-B and Rht-D for plant height and TaMFT for seed dormancy, validating its effectiveness [23]. Similarly, in castor, integration of QTL mapping with transcriptome analysis and WGCNA identified four candidate genes (RcSYN3, RcNTT, RcGG3, and RcSAUR76) for growth stages within two major QTL clusters on linkage groups 3 and 6 [24]. These case studies demonstrate how network analysis can prioritize candidates from large QTL intervals for functional validation.

Disease Mechanisms and Biomedical Applications

In biomedical research, these integrative approaches have elucidated disease mechanisms and identified potential therapeutic targets. In Alzheimer's disease, WGCNA of human hippocampal expression data identified two modules significantly associated with disease severity, functioning in NF-κB signaling and cGMP-PKG signaling pathways [22]. Hub gene analysis revealed key players including metallothionein (MT) genes, Notch2, MSX1, ADD3, and RAB31, with increased expression confirmed in AD transgenic mice [22]. For complex human diseases, network reconstruction of trans-QTL hotspots using multi-omics data and prior biological knowledge has generated novel functional hypotheses for conditions including schizophrenia and lean body mass [19]. This approach demonstrates how genetic associations can be mapped to regulatory networks to explain disease pathophysiology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Integrated QTL-Network Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping | SSR markers, SNP arrays (e.g., Axiom 60K) | Genetic marker systems for linkage analysis and QTL mapping [24] [25] |

| Transcriptomics | RNA-seq, Microarrays (e.g., Affymetrix) | Genome-wide expression profiling for co-expression network construction [23] [22] |

| QTL Analysis Software | R/qtl, JoinMap, ICIM | Genetic map construction and QTL detection [24] |

| Network Analysis | WGCNA R package, Omics Playground | Co-expression network construction, module detection, and trait associations [22] [26] |

| Functional Enrichment | clusterProfiler, WebGestalt | Gene ontology and pathway analysis of significant modules [22] |

| Network Visualization | Cytoscape, ggplot2 | Visualization of co-expression networks and results [22] [27] |

Diagram 2: Candidate gene prioritization logic flow.

Advanced Integration Techniques and Emerging Methods

Spectral Network Approaches for Network QTL Mapping

Beyond traditional QTL and WGCNA integration, advanced methods like spectral network QTL (snQTL) have been developed to directly map genetic loci affecting entire co-expression networks [6]. This approach tests associations between genotypes and joint differential networks via tensor-based spectral statistics, overcoming multiple testing challenges that plague conventional methods [6]. Applied to three-spined stickleback data, snQTL uncovered chromosomal regions affecting gene co-expression networks, including one strong candidate gene missed by traditional eQTL analyses [6]. This represents a paradigm shift from mapping genetic effects on individual genes to mapping effects on network structures themselves.

Multi-Omics Integration for trans-QTL Hotspot Resolution

For trans-QTL hotspots - genetic loci influencing numerous genes across different chromosomes - advanced integration strategies combine genotype, gene expression, and epigenomic data (e.g., DNA methylation) with prior biological knowledge from databases like GTEx, BioGrid, and Roadmap Epigenomics [19]. State-of-the-art network inference methods including BDgraph and graphical lasso can incorporate these continuous priors to reconstruct regulatory networks underlying trans associations [19]. Benchmarks demonstrate that prior-based strategies outperform methods without biological knowledge and show better cross-cohort replication [19]. This approach has generated novel functional hypotheses for schizophrenia and lean body mass by elucidating the molecular networks through which trans-acting genetic variants influence complex traits.

The integration of QTL mapping with gene co-expression network analysis represents a mature but still evolving framework for dissecting complex traits. By combining genetic anchors with functional context, researchers can efficiently prioritize candidate genes and generate testable hypotheses about biological mechanisms. As evidenced by successful applications across diverse organisms from plants to humans, this integrative approach consistently outperforms single-dimensional analyses. Future methodological developments will likely focus on improved multi-omics integration, dynamic network modeling across developmental stages or environmental conditions, and machine learning approaches for causal network inference. These advances will further enhance our ability to reconstruct gene networks from QTL data, ultimately accelerating discovery in both basic biology and applied biotechnology.

Reconstructing gene networks from quantitative trait loci (QTL) data is a cornerstone of modern systems biology, enabling researchers to move from associative genetic findings to causal mechanistic models. The integration of multi-omics data—particularly genotype, gene expression, and DNA methylation—presents unprecedented opportunities to unravel complex regulatory hierarchies governing cellular processes and disease pathogenesis. This integration is technically challenging due to the hierarchical relationships between molecular layers, differing timescales of regulation, and the high-dimensional nature of omics data. This Application Note provides a comprehensive framework of current methodologies, protocols, and tools for inferring biological networks from these three critical data types, with emphasis on practical implementation for researchers in genomics and drug development.

Methodological Landscape for Multi-omics Network Inference

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Multi-omics Network Inference Methods

| Method | Primary Data Types | Statistical Approach | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ColocBoost [28] | Genotype, Expression, Methylation, Protein | Multi-task gradient boosting | Scales to hundreds of traits; accommodates multiple causal variants; specialized for xQTL analysis | Computational intensity for very large datasets |

| MINIE [29] | Transcriptomics, Metabolomics | Bayesian regression with differential-algebraic equations | Explicitly models timescale separation between molecular layers; integrates single-cell and bulk data | Currently optimized for metabolomics-transcriptomics integration |

| iNETgrate [30] | Gene Expression, DNA Methylation | Correlation network integration with PCA | Creates unified gene networks; enables survival risk stratification; superior prognostication | Requires longer computational time (~6 hours for standard analyses) |

| EMDN [31] | DNA Methylation, Gene Expression | Multiple network framework with differential networks | Avoids pre-specifying methylation-expression correlation; identifies both positive and negative correlated modules | Limited to pairwise gene relationships in network construction |

| Regression2Net [32] | Gene Expression, Genomic/Methylation Data | Penalized regression | Builds Expression-Expression and Expression-Methylation networks; identifies functional communities | Network topology dependent on regression parameters |

| Guided Network Estimation [33] | Any multi-omic data (e.g., SNPs, Expression, Metabolites) | Graphical LASSO with guided network conditioning | Conditions target network on guiding network structure; reveals biologically coherent metabolite groups | Requires pre-specified guiding network structure |

The methodological landscape for multi-omics network inference has evolved substantially from single-omic analyses to approaches that vertically integrate across molecular layers. ColocBoost represents a significant advancement for genotype-focused integration, implementing a multi-task learning colocalization framework that efficiently scales to hundreds of molecular traits while accommodating multiple causal variants within genomic regions of interest [28]. For DNA methylation and gene expression integration, the iNETgrate package provides a robust network-based solution that computes a unified correlation structure from both data types, significantly improving prognostic capabilities in cancer datasets compared to single-omic analyses [30]. The EMDN algorithm offers an alternative multiple-network framework that constructs separate differential comethylation and coexpression networks, then identifies epigenetic modules common to both networks without pre-specifying correlation directions [31].

Protocol: Multi-omics QTL Colocalization with ColocBoost

Experimental Workflow

Diagram: ColocBoost Multi-omics QTL Analysis Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedures

Input Data Preparation

- Genotype Data: Process VCF files to obtain dosages for 5M-10M SNPs across the genome for N ≈ 600 samples. Perform standard QC: call rate > 95%, MAF > 0.01, HWE p-value > 1×10⁻⁶.

- Molecular QTL Data: Prepare normalized gene-level molecular traits including:

- Expression QTL: TPM or FPKM values from RNA-seq of relevant tissues

- Methylation QTL: Beta values from Illumina EPIC arrays or bisulfite sequencing

- Protein QTL: LFQ intensities from mass spectrometry-based proteomics

- Covariates: Include known technical (batch, platform) and biological (age, sex, genetic ancestry) covariates to reduce false positives.

ColocBoost Implementation

Output Interpretation

- Variant-trait Associations: Identify SNPs with non-zero effect sizes (β ≠ 0) across multiple traits

- Colocalization Confidence: Calculate posterior probabilities for shared causal variants across molecular layers

- Functional Validation: Integrate with external regulatory annotations (ENCODE, promoter-capture Hi-C) to prioritize likely causal mechanisms

Protocol: Integrated Methylation-Expression Network Analysis with iNETgrate

Experimental Workflow

Diagram: iNETgrate Unified Network Construction

Step-by-Step Procedures

Data Preprocessing and Integration

- Methylation Data: Process IDAT files with minfi, perform functional normalization, and map CpG sites to gene regions (TSS1500, TSS200, 5'UTR, 1st Exon, Gene Body, 3'UTR).

- Gene-level Methylation Scores: Compute eigenloci using PCA for each gene's CpG sites:

- Expression Data: Process raw counts with DESeq2 or voom, normalize for library size, and batch effects.

Network Construction and Module Detection

- Integrative Factor Optimization: Test μ values from 0 to 1 in increments of 0.1 to determine optimal weighting between methylation and expression correlations.

- Edge Weight Calculation: For each gene pair (i,j), compute integrated edge weight: where μ = 0.4 was optimal in LUSC analysis [30].

- Module Identification: Apply hierarchical clustering with dynamic tree cutting to identify gene modules with coherent multi-omic patterns.

Survival and Functional Analysis

- Eigengene Extraction: Compute module eigengenes from expression (suffixed "e"), methylation (suffixed "m"), and integrated data (suffixed "em").

- Prognostic Model Building:

- Pathway Enrichment: Perform overrepresentation analysis using KEGG, Reactome, or GO databases to interpret identified modules.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Specification | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Generation | Illumina EPIC BeadChip | 850K CpG sites | Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling |

| 10x Genomics Multiome | Simultaneous GEX + ATAC | Paired transcriptome and epigenome in single cells | |

| Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing | >30X coverage | Base-resolution methylation mapping | |

| Computational Tools | ColocBoost R package | Gradient boosting framework | Multi-omics QTL colocalization |

| iNETgrate Bioconductor package | Network integration | Unified methylation-expression networks | |

| EMDN R package | Multiple network algorithm | Epigenetic module identification | |

| CellChat | Cell-cell communication | Ligand-receptor network inference from spatial data | |

| Reference Databases | CellMarker | Cell-specific markers | Cell type annotation in scRNA-seq |

| KEGG PATHWAY | >500 pathways | Functional enrichment analysis | |

| ENCODE rE2G Catalog | Enhancer-gene links | Validation of regulatory predictions |

Applications in Disease Mechanism Elucidation

The integration of genotype, expression, and methylation data has proven particularly powerful in uncovering disease mechanisms. In glioblastoma multiforme, Regression2Net identified 447 genes with methylation-expression connections significantly enriched in cancer pathways, including ABC transporter genes associated with drug resistance [32]. For Alzheimer's disease, ColocBoost analysis of 17 xQTL traits from the ROSMAP cohort revealed sub-threshold GWAS loci with multi-omics support, including genes BLNK and CTSH, providing new functional insights into AD pathogenesis [28]. In breast cancer, the EMDN algorithm successfully identified epigenetic modules that accurately predicted subtypes and patient survival time using only methylation profiles, demonstrating the clinical translational potential of integrated networks [31].

The strategic integration of genotype, gene expression, and DNA methylation data provides a powerful framework for reconstructing comprehensive gene regulatory networks from QTL data. The methodologies presented here—from multi-omics QTL colocalization to unified network analysis—enable researchers to move beyond associative findings toward mechanistic models of disease pathogenesis. As multi-omics technologies continue to advance, these network inference approaches will play an increasingly critical role in therapeutic target identification and validation for complex diseases.

Integrating Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) data with advanced computational models is a powerful paradigm for elucidating the complex genetic architectures underlying phenotypic variation. The reconstruction of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) from genetic data enables researchers to move from identifying isolated loci to understanding the systems-level interactions that govern biological processes and complex traits. Advanced computational frameworks—including graphical models, Bayesian networks, and regularized regression techniques—provide the statistical rigor and scalability necessary for this task. These methods can effectively handle the high-dimensional nature of genomic data, where the number of variables (genes, markers) often vastly exceeds sample sizes, while also modeling the direct and indirect regulatory relationships between genetic elements.

The primary challenge in GRN reconstruction from QTL data lies in distinguishing direct causal relationships from indirect correlations and in dealing with the inherent noise and sparsity of biological datasets. Computational frameworks address this by incorporating constraints based on biological principles, such as sparsity (networks have limited connections), temporal dynamics (regulatory effects change over time), and modularity (functional grouping of genes). When applied to the context of a broader thesis on reconstructing gene networks from QTL data, these frameworks provide a principled approach to transitioning from genetic association to mechanistic understanding, ultimately illuminating the causal chains from DNA to phenotype.

Graphical Models for Network Inference

Theoretical Foundations and Application Notes

Graphical models offer a comprehensive probabilistic framework for characterizing the conditional independence structure between random variables, represented as nodes in a graph. In the context of GRNs, these variables are typically genes, and the edges represent regulatory interactions. The Markov property of graphical models allows for the factorization of the complex joint distribution of gene expressions into simpler, local distributions, making computation and inference tractable.

Several distinct classes of graphical models are employed in computational biology:

- Undirected Graphical Models (UGs): Represent symmetric associations, such as metabolic couplings or protein-protein interactions, where directionality is not inferred. The joint distribution factorizes over the cliques of the graph [34].

- Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs): Model asymmetric, causal relationships under the constraint of no feedback loops. They are fundamental to Bayesian Networks and allow for intuitive representation of causal pathways from genetic loci to traits [34].

- Reciprocal Graphs (RGs): A more general class that can model both directed and undirected edges, including feedback loops and cyclic relationships, which are ubiquitous in biological systems (e.g., in circadian rhythms or feedback inhibition). RGs strictly contain DAGs and UGs as special cases, providing greater flexibility for modeling complex biological networks [34].

The following protocol outlines the application of graphical models to QTL-integrated network inference.

Protocol 1: Building a Conditional Independence Graph with QTL Constraints

- Objective: To reconstruct an undirected graph of a gene regulatory network from gene expression data, using QTLs as structural priors to guide the inference.

- Research Reagents:

- Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize the gene expression data to minimize technical artifacts. Genotype data should be encoded numerically.

- QTL Mapping: Identify genomic loci significantly associated with the expression levels of each gene. These are known as expression QTLs (eQTLs). Cis-eQTLs (local to the gene) can be used as fixed, causal anchors in the network.

- Conditional Independence Testing: For each pair of genes, test for independence conditional on all other genes and, critically, on the identified eQTLs. Use a partial correlation-based test (for Gaussian data) or an entropy-based test like the G^2 test.

- Graph Construction: Apply the PC algorithm or a similar constraint-based method. An edge between two genes is included if they remain dependent after conditioning on all possible subsets of other genes and the relevant QTLs. This step helps eliminate edges resulting from indirect regulation or common genetic confounding.

- Global Optimization: Use a scoring function, such as the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), to search the space of possible graphs and identify the model that best explains the data without overfitting.

- Technical Notes: The faithfulness assumption (that conditional independencies in the data imply separations in the graph) is critical for the correctness of this approach. Violations can occur with small sample sizes. The

pcalgpackage in R provides robust implementations of these algorithms.

The workflow for this protocol, integrating QTL data as causal anchors, is visualized below.

Key Methodological Variations

Different graphical model approaches offer specific advantages for particular biological scenarios. Empirical Bayes methods, such as the Empirical Light Mutual Min (ELMM) algorithm, use a data-driven approach to estimate prior distributions for independence parameters, which is particularly advantageous for small sample sizes and noisy data [38]. ELMM also introduces a heuristic relaxation of independence constraints in dense network regions to mitigate the multiple testing problem associated with recovering hubs [38].

For data where feedback mechanisms are a critical component, Reciprocal Graphical (RG) models are highly suitable. They extend the capability of DAGs to model cyclic causality, providing a more realistic representation of biological feedback loops, such as those found in oscillatory networks or homeostasis mechanisms [34]. An advanced application involves integrating multi-omics data (DNA, RNA, protein) within an RG framework by factorizing the joint distribution according to the central dogma of biology, thereby constructing a coherent, multi-layer regulatory network [34].

Table 1: Comparison of Graphical Model Approaches for GRN Inference

| Method Type | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Suitable Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undirected (UG) | Gaussian Markov Random Fields | Computationally efficient; models symmetric relationships. | Cannot infer causality; assumes no feedback. | Steady-state gene expression data. |

| Bayesian Network (DAG) | Conditional probability via directed, acyclic graphs. | Infers causal direction; intuitive representation. | Cannot model feedback loops; search space is large. | Intervention/perturbation data; eQTL data. |

| Reciprocal Graph (RG) | Generalization of DAGs and UGs. | Models feedback loops; integrates multi-omics data. | Complex model specification and inference. | Time-course data; multi-omics (RNA, ATAC, Protein). |

| Empirical Bayes (ELMM) | Data-driven prior estimation for parameters. | Robust to small sample sizes; improved hub recovery. | Heuristic relaxation may require calibration. | High-dimensional, low-sample-size expression data. |

Bayesian Networks and Bayesian Inference

Application Notes and Protocol

Bayesian Networks are a class of probabilistic graphical models that represent the joint distribution of variables via a DAG, where the direction of an edge implies a potential causal relationship. In GRNs, this allows researchers to model the expression of a target gene as a conditional probability distribution given the states of its parent regulator genes. The power of the Bayesian framework lies in its ability to quantify uncertainty in network structures and to incorporate prior knowledge, such as information from QTL studies or previously published interactions, into the inference process.

A key development is the use of coloured graphical models, or regulatory graphs, which incorporate edge attributes (colours) to directly represent hypotheses about regulatory mechanisms, such as inhibition or excitation. These models admit a conditional conjugate analysis, enabling efficient Bayesian model selection to identify high-probability network structures even in huge model spaces [39].

Protocol 2: Bayesian Network Inference with QTL Integration