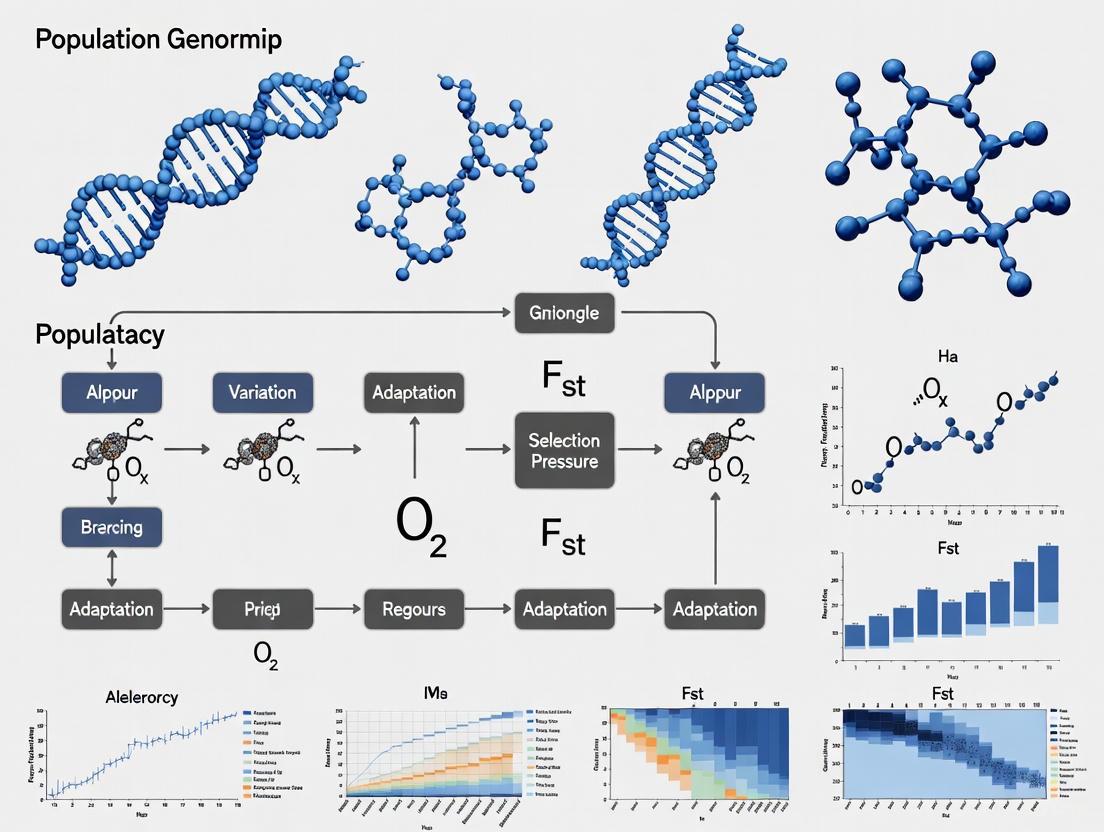

Population Genomic Approaches to Local Adaptation: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of population genomic methodologies for identifying local adaptation, a process critical for understanding how species evolve to environmental heterogeneity.

Population Genomic Approaches to Local Adaptation: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of population genomic methodologies for identifying local adaptation, a process critical for understanding how species evolve to environmental heterogeneity. We explore foundational evolutionary concepts and detail core analytical techniques, including differentiation outlier scans and genotype-environment associations (GEA). The content addresses significant methodological challenges, such as confounding demographic history and statistical power, and outlines best practices for validation. Finally, we discuss the translational potential of these approaches in biomedical research, highlighting how insights into adaptive genetic variation can inform drug discovery, predict disease susceptibility, and guide conservation efforts for species with biomedical relevance.

The Genomic Landscape of Local Adaptation: Core Concepts and Evolutionary Significance

Local adaptation occurs when individuals from a population have higher average fitness in their local environment than those from other populations of the same species, driven by divergent natural selection across heterogeneous environments [1]. This process represents a cornerstone of evolutionary biology, with critical implications for understanding how populations diversify and respond to environmental variation. The genetic basis of local adaptation primarily arises through two distinct mechanisms: antagonistic pleiotropy, where alternate alleles at a single locus are favored in contrasting habitats, creating genetic trade-offs; and conditional neutrality, where alleles are beneficial in one environment but neutral in others [2] [3]. Understanding the balance between these mechanisms is essential for predicting population responses to environmental change and has practical applications in conservation, agriculture, and drug development.

Quantitative Landscape of Local Adaptation

Research across diverse systems has quantified the relative contributions of antagonistic pleiotropy and conditional neutrality to local adaptation. The following table summarizes key findings from empirical studies:

Table 1: Prevalence of antagonistic pleiotropy and conditional neutrality across study systems

| Study System | Antagonistic Pleiotropy | Conditional Neutrality | Experimental Context | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boechera stricta (mustard plant) | 2.8% of genome | 8% of genome | Field experiments with recombinant inbred lines across parental environments | [2] [3] |

| Escherichia coli (bacteria) | Larger populations evolved heavier fitness trade-offs | - | Experimental evolution in nutritionally limited environments | [4] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | CBF2 locus showed strong trade-offs | - | Reciprocal transplant and gene-editing experiments | [5] |

Table 2: Characteristics of antagonistic pleiotropy versus conditional neutrality

| Characteristic | Antagonistic Pleiotropy | Conditional Neutrality |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Alleles reverse fitness rank in alternative environments | Alleles advantageous in one environment, neutral in others |

| Effect on genetic variation | Maintains polymorphism across landscape | May lead to fixation of conditionally beneficial alleles |

| Detection requirement | Significant fitness effects in ≥2 environments | Significant fitness effect in one environment only |

| Response to gene flow | Maintained despite moderate gene flow | More susceptible to swamping by gene flow |

| Contribution to local adaptation | Direct genetic trade-offs | Environment-specific optimization |

The data reveal that while conditional neutrality appears more common genomically, antagonistic pleiotropy occurs at biologically significant levels and can involve loci with major fitness effects. The CBF2 locus in Arabidopsis thaliana provides a particularly compelling case, where a single gene explains a substantial fitness trade-off: the foreign CBF2 genotype reduced long-term mean fitness by over 10% in Sweden and more than 20% in Italy [5].

Experimental Protocols for Dissecting Local Adaptation

Protocol 1: Reciprocal Transplant Field Experiments

Purpose: To quantify local adaptation and identify genetic trade-offs in natural environments [2] [5].

Materials:

- Recombinant Inbred Lines (RILs) or ecotypes from contrasting habitats

- Field sites representing parental environments

- Equipment for monitoring survival, reproduction, and environmental variables

Procedure:

- Generate Mapping Population: Develop RILs through repeated selfing or sibling mating of crosses between ecotypes from contrasting environments (e.g., 177 F₆ RILs for Boechera stricta) [2].

- Experimental Design: Plant multiple individuals per RIL at each field site (e.g., 6 individuals/RIL/garden) in randomized complete blocks.

- Fitness Monitoring: Track key fitness components across the complete life cycle:

- Probability of survival

- Age at first reproduction

- Fecundity (seed or fruit production)

- Total lifetime fitness

- Environmental Data Collection: Record abiotic and biotic factors (temperature, precipitation, pathogen load) to correlate with selection.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Compare fitness of local versus foreign genotypes at each site

- Perform QTL mapping to identify genomic regions associated with fitness

- Test for QTL × environment interactions to distinguish antagonistic pleiotropy from conditional neutrality

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Candidate Genes

Purpose: To confirm causal genes underlying local adaptation and their mechanisms [5].

Materials:

- Near-isogenic lines (NILs) with introgressed candidate regions

- Gene-editing tools (CRISPR-Cas9)

- Controlled environment growth chambers

- Field sites or simulated native environments

Procedure:

- Develop Near-Isogenic Lines: Create lines with candidate genomic regions (e.g., CBF2 locus) introgressed into alternative genetic backgrounds through repeated backcrossing.

- Gene Editing: Generate replicated gene-edited lines in native genetic backgrounds to test specific nucleotide polymorphisms.

- Environment Simulation: Program growth chambers to mimic temperature and photoperiod regimes of native habitats.

- Fitness Assays: Quantify fitness components in both field and controlled environments:

- Survival under stress conditions (e.g., freezing)

- Fecundity measurements

- Physiological traits (e.g., cold acclimation)

- Mechanism Testing:

- Compare fitness of NILs with alternate alleles across environments

- Validate trade-offs using gene-edited constructs

- Partition fitness effects into viability and fecundity components

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for local adaptation studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Inbred Lines (RILs) | Fixed genetic combinations enabling replication across environments | Mapping QTLs for fitness components in field environments [2] |

| Near-Isogenic Lines (NILs) | Isolated genomic segments in controlled backgrounds | Validating individual locus effects on fitness trade-offs [5] |

| Gene-Edited Lines | Precise nucleotide modifications in native backgrounds | Establishing causality of specific polymorphisms [5] |

| Common Garden Sites | Field environments representing selective regimes | Quantifying local adaptation and fitness trade-offs [2] [5] |

| Environmental Simulators | Growth chambers programmed with native conditions | Controlled tests of gene function under ecologically relevant conditions [5] |

| Genetic Markers | Genome-wide polymorphisms for genotyping | Tracking allele frequency changes in response to selection [2] |

Methodological Advances in Detection

Traditional approaches for detecting local adaptation have relied on comparisons between QST (quantitative genetic differentiation) and FST (neutral genetic differentiation). However, these methods frequently assume equal relatedness among subpopulations, which rarely holds in natural populations [6] [7]. Recent methodological innovations address this limitation:

The LogAV method compares the log-ratio of two estimates of the same ancestral additive genetic variance—one derived from between-population effects and the other from within-population effects. Under neutrality, these estimates should be equal, while deviations indicate local adaptation [6] [7]. This approach accounts for complex population structures and genealogical relationships, providing a more accurate neutral baseline for detecting selection.

Local adaptation arises through the combined effects of antagonistic pleiotropy and conditional neutrality, creating a genomic architecture that enables populations to specialize to their local environments while maintaining evolutionary potential. The experimental frameworks outlined here provide robust approaches for disentangling these mechanisms across diverse systems. As methodological innovations continue to enhance our ability to detect selection in complex populations, integrating field studies with functional validation will remain crucial for establishing the causal chains connecting genetic variation to fitness consequences in ecologically relevant contexts.

Understanding the genetic basis of how organisms adapt to local environments represents a central challenge in modern evolutionary biology. This process, known as ecological speciation, occurs when reproductive isolation evolves between populations as a result of ecologically based divergent natural selection [8]. The study of ecological speciation sits at the intersection of population genetics, genomics, and ecology, requiring sophisticated approaches to detect the genomic signatures of selection and link them to ecological processes. As genomic technologies advance, researchers are increasingly able to unravel the complex architecture of local adaptation, revealing that it can be driven by various genetic mechanisms including standing genetic variation, new mutations, and regulatory changes [9] [8]. This application note provides a structured framework for investigating these evolutionary questions, offering standardized protocols, data presentation standards, and analytical workflows tailored for research on genetic variation and ecological speciation within population genomic studies.

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts in Ecological Speciation Genetics

| Concept | Definition | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological Speciation | Evolution of reproductive isolation between populations due to ecologically based divergent natural selection [8] | Requires demonstrating a link between divergent selection and reproductive isolation |

| Standing Genetic Variation | Preexisting genetic variation in a population upon which selection can act [8] | Can enable more rapid adaptation than waiting for new mutations |

| Mutation-Order Speciation | Populations fix different mutations while adapting to similar selection pressures [8] | Contrasts with ecological speciation; divergence occurs by chance rather than selection |

| Genomic Architecture | The number, effect sizes, and distribution of genes underlying adaptive traits [10] | Influences detectability in genomic scans and evolutionary potential |

| Extrinsic Postzygotic Isolation | Reduced hybrid fitness that is environmentally dependent [8] | Hybrids have lower fitness in parental environments but not necessarily in lab conditions |

Quantitative Foundations: Measuring Genetic Variation and Divergence

Comprehensive population genomic studies have quantified patterns of genetic variation within and between populations, providing baseline metrics for studying local adaptation. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings that establish expected parameters for diversity and differentiation measurements in evolutionary genomics studies.

Table 2: Quantifying Human Genomic Variation (Based on 929 High-Coverage Genomes) [11]

| Variant Type | Number Identified | Notable Features | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) | 67.3 million | Includes ~1 million variants at ≥20% frequency in specific populations not found in previous datasets | Highlights importance of diverse sampling for discovering common population-specific variants |

| Small Insertions/Deletions (indels) | 8.8 million | Typically involve <50 nucleotides; less frequent than SNVs but potentially larger functional impact [12] | Important for coding region analyses; may cause frameshift mutations |

| Copy Number Variants (CNVs) | 40,736 | Structural variants involving ≥50 nucleotides; account for more variation between individuals than SNVs and indels combined [13] | Challenging to detect with short-read sequencing; require long-read technologies for comprehensive assessment |

Table 3: Expected Variant Load in a Typical Human Genome (vs. Reference) [12]

| Variant Category | Average Count per Genome | Nucleotides Affected | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) | ~5,000,000 | ~5,000,000 nucleotides | Distinguish between rare variants and polymorphisms (≥1% frequency) |

| Insertion/Deletion Variants | ~600,000 | ~2,000,000 nucleotides | Detection requires specialized algorithms beyond standard SNP callers |

| Structural Variants | ~25,000 | >20,000,000 nucleotides | Long-read sequencing significantly improves detection accuracy [13] |

| TOTAL | ~5,625,000 variants | ~27,000,000 nucleotides | Complete genome is ~99.6% identical to reference |

Experimental Workflows: From Sampling to Genomic Analysis

Conducting robust research on ecological speciation requires integrated workflows that combine field observations, laboratory experiments, and genomic analyses. The following standardized protocols ensure comprehensive data collection and interpretation.

Integrated Workflow for Ecological Speciation Genomics

Protocol 1: Genome Sequencing for Variant Discovery

Purpose: To comprehensively identify genetic variants within and between populations, providing the foundation for studies of local adaptation.

Materials:

- High-quality DNA samples (≥100 ng/µL, minimum degradation)

- PacBio Revio system or Illumina NovaSeq for long-read or short-read sequencing respectively [13]

- Twist target enrichment probes for regions of interest (optional) [13]

- Standard library preparation reagents

Procedure:

- Sample Quality Control: Verify DNA integrity using agarose gel electrophoresis or Bioanalyzer (RIN ≥ 7.0).

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA and attach sequencing adapters according to manufacturer protocols.

- Sequencing: Process libraries on appropriate platform to achieve minimum 30x coverage for whole genome sequencing [13].

- Variant Calling: Map reads to reference genome using minimap2 (long-read) or BWA (short-read), then call variants using specialized pipelines.

- Variant Annotation: Classify variants by type (SNV, indel, SV), genomic location, and predicted functional impact.

Technical Notes: Long-read sequencing (PacBio HiFi) provides superior performance for structural variant detection and phasing [13]. For large sample sizes, consider tunable coverage (10-30x) based on research budget and objectives.

Protocol 2: Genotype-Environment Association Analysis

Purpose: To identify genetic variants associated with environmental variables, suggesting local adaptation.

Materials:

- Genotype data (VCF format) for all sampled individuals

- Environmental data layers (climate, soil, vegetation) for sampling locations

- R or Python with appropriate packages (LEA, BayPass, RDA)

Procedure:

- Environmental Data Collection: Compile relevant environmental variables for each sampling location using GIS databases or direct measurements.

- Data Quality Control: Filter genetic variants for missing data (>10% missingness), minor allele frequency (<5%), and deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

- Population Structure Correction: Perform Principal Components Analysis (PCA) or use ADMIXTURE to identify and control for neutral population structure [14].

- Association Testing: Apply one or more of the following methods:

- Redundancy Analysis (RDA): Constrained ordination that identifies genetic variation explained by environmental factors [14]

- Bayesian Methods: BayPass or similar for modeling allele frequency-environment correlations

- Outlier Tests: FDIST2 or similar to identify loci with excessive differentiation

- Significance Thresholding: Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg) to account for multiple testing.

Technical Notes: Significance in GEA studies can be influenced by population history; always correct for structure to reduce false positives. IBE (Isolation by Environment) results should be interpreted alongside IBD (Isolation by Distance) [14].

Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Genomics

Selecting appropriate reagents and platforms is critical for successful research in ecological speciation genomics. The following table details essential research solutions and their specific applications.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Ecological Speciation Genomics

| Reagent/Platform | Primary Function | Application in Ecological Speciation | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi Sequencing | Long-read sequencing with high accuracy | Reference-grade genome assembly; comprehensive variant detection across all classes [13] | Ideal for structural variants, phasing, and challenging genomic regions |

| Twist Target Enrichment | Capture probes for specific genomic regions | Focused sequencing of candidate regions; cost-effective for large sample sizes [13] | Can be combined with long-read sequencing for targeted approach |

| Illumina Short-Read Sequencing | High-throughput sequencing with low error rates | SNP discovery and genotyping; population genomic analyses [11] | Limited for structural variants and repetitive regions |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | DNA treatment for methylation studies | Epigenetic analyses of local adaptation; gene regulation studies | PacBio HiFi provides methylation data without special preparation [13] |

| RNA Extraction Kits (e.g., TRIzol) | Isolation of high-quality RNA from tissues | Gene expression studies; functional validation of candidate genes [14] | Critical for connecting genotype to phenotype |

Conceptual Framework: Genetic Mechanisms of Reproductive Isolation

Understanding how reproductive isolation evolves through ecological mechanisms requires integrating knowledge of genetic architecture with ecological processes. The following diagram illustrates the key genetic mechanisms and their relationships in ecological speciation.

Advanced Analytical Framework: From Genotypes to Adaptive Phenotypes

Translating genomic data into meaningful biological insights about local adaptation requires sophisticated analytical approaches that connect genetic variation to ecological function.

Protocol 3: Quantifying Genomic Vulnerability to Climate Change

Purpose: To project how well populations are adapted to future environments and identify those most at risk from climate change.

Materials:

- Genotype-Environment association results

- Future climate projections (e.g., IPCC scenarios)

- R packages (gradientForest, SDM, or similar)

Procedure:

- Model Allele-Environment Relationships: Build models linking allele frequencies to current environmental conditions using machine learning approaches.

- Project Future Genomic Composition: Use future climate projections to predict the genomic composition that would be optimal under future conditions.

- Calculate Genomic Offset: Quantify the mismatch between current and predicted future genomic compositions [14].

- Identify Vulnerable Populations: Rank populations by their genomic vulnerability scores for conservation prioritization.

Technical Notes: This approach has been successfully applied to understory herbs like Adenocaulon himalaicum, identifying populations in the southeastern Himalayas and northern Japan as particularly vulnerable to climate change [14].

Statistical Considerations for Architecture of Adaptation

A critical challenge in studying the genetics of local adaptation is that current methods are biased toward detecting large-effect loci, potentially missing a substantial fraction of adaptive variation [10]. This bias creates a gap between the total amount of locally adaptive variation and what is explained by genomic studies. To address this limitation:

- Combine Approaches: Integrate GWAS, candidate gene studies, and gene expression analyses

- Validate Functionally: Use gene editing (CRISPR) or transgenic approaches to confirm effects

- Consider Standing Variation: Acknowledge that adaptation often proceeds from standing genetic variation rather than new mutations [8]

Studies of threespine stickleback demonstrate how standing genetic variation in marine populations has been repeatedly used during adaptation to freshwater environments, facilitating rapid parallel evolution [8].

Research on ecological speciation and local adaptation has progressed from documenting patterns to understanding genetic mechanisms and ecological consequences. The integrated approaches presented in this application note provide a roadmap for connecting genomic variation to ecological processes across different spatial and temporal scales. Future research will benefit from deeper integration of genomic and phenotypic analyses, increased attention to regulatory variation and epigenetic mechanisms, and application of these methods to inform conservation strategies in rapidly changing environments.

In evolutionary genetics, a genomic signature of selection refers to a characteristic pattern in DNA sequences that provides evidence of past natural selection [15]. These signatures arise because beneficial genetic variations that increase an organism's fitness become more common in a population over generations. The identification of these signatures allows researchers to infer the action of selection directly from genomic data, pinpoint the specific genes or genomic regions involved, and understand the evolutionary history and adaptive processes of populations [16] [17]. This framework is fundamental to studying local adaptation, where populations genetically diverge to become better suited to their local environmental conditions, such as climate, pathogens, or dietary resources [16] [18]. The core of detection methods lies in distinguishing these selection signatures from patterns that could be caused by neutral processes like genetic drift [16].

Theoretical Expectations and Key Signatures

Selective events alter the distribution of genetic variation in a population, creating predictable statistical anomalies in genomic data. The expected signatures depend on the mode and timing of selection.

- Selective Sweeps: A hard sweep occurs when a new, beneficial mutation arises and rapidly increases in frequency, carrying with it the surrounding linked neutral variants in a process called "hitchhiking" [17]. This results in a region of the genome with reduced genetic diversity and an excess of rare variants. Because the beneficial allele arises on a single haplotype background, it also creates a region of high linkage disequilibrium (LD) and long, high-frequency haplotypes [17] [19]. In contrast, a soft sweep occurs when selection acts on a beneficial allele that is already present as standing variation or arises on multiple haplotype backgrounds. This leads to a less pronounced reduction in diversity and the presence of multiple haplotypes at high frequency [17].

- Local Adaptation: In spatially structured populations, selection can favor different alleles in different environments. This leads to increased genetic differentiation between populations at the loci under selection, which can be detected by metrics like FST that measure the proportion of genetic variance due to differences between populations [16] [18]. Alleles at these loci will also show strong correlations with environmental variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation, soil composition) [16].

The diagram below illustrates the genomic consequences of a selective sweep.

Diagram 1: Genomic Impact of a Selective Sweep. A beneficial mutation (red) arises on one haplotype background. As positive selection drives it to high frequency, it "sweeps" linked neutral variants (green) along with it, reducing genetic diversity and creating a long, high-frequency haplotype in the region.

Different statistical tests have been developed to detect these signatures, each with unique power depending on the selection stage and model.

Table 1: Key Statistical Methods for Detecting Selection Signatures

| Category | Statistic | Core Concept | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population Differentiation | FST [16] [19] | Measures genetic differentiation between populations based on allele frequencies. | Identifying local adaptation; contrasting populations in different environments. | Simple, intuitive; directly targets spatial variation. |

| XP-CLR [19] | A composite likelihood ratio that models allele frequency differentiation while accounting for LD and population history. | Identifying selective sweeps by comparing two populations. | More robust to demographic history than FST. | |

| Haplotype-Based | iHS [17] [19] | Compares the integrated haplotype homozygosity (EHH) around a core allele to that of other alleles within a single population. | Detecting ongoing or incomplete selective sweeps. | High power for selection before the beneficial allele reaches fixation. |

| XP-EHH [17] [19] | Compares EHH of a core haplotype between two populations. | Detecting selective sweeps that have completed or reached near-fixation in one population. | Effective for finding nearly fixed selective sweeps. | |

| Allele Frequency Spectrum | Tajima's D [19] | Compares the number of segregating sites to the average pairwise nucleotide diversity. | Distinguishing between purifying selection (negative D) and balancing selection (positive D). | Classic test for deviations from neutral expectations. |

| CLR [19] | Compares the likelihood of the site frequency spectrum under selection vs. neutrality at a specific locus. | Identifying selective sweeps in a single population. | Incorporates recombination rate to improve specificity. | |

| Branch Statistic | PBS [18] | Estimates the genetic divergence of a focal population from two outgroup populations in a tree-like model. | Identifying local selective sweeps specific to one population. | Controls for shared ancestral polymorphism and genetic drift. |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Selection Statistics [19]

| Statistic | Power During Ongoing Selection | Power at/Near Fixation | Sensitivity to Demography | Optimal Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FST | Moderate | High | High | Multiple populations, ~15+ individuals per population [19] |

| iHS | High | Low | Moderate | Single population, high-density SNPs (>1 SNP/kb) [19] |

| XP-EHH | Low | High | Moderate | Two populations for comparison |

| CLR | Moderate | High | Lower (if recombination map is known) | Single population, known recombination rate |

| PBS | High | High | Moderate | Three populations to define evolutionary branches [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Scan for Local Adaptation using FST and PBS

This protocol uses allele frequency differences between populations to identify loci under local selection [16] [18].

1. Sample Collection and DNA Sequencing

- Sample Selection: Collect tissue or blood samples from multiple individuals from at least two populations (for FST) or three populations (for PBS) inhabiting distinct environmental conditions. A minimum of ~15 diploid individuals per population is often sufficient for initial scans [19].

- DNA Extraction & Genotyping: Perform whole-genome sequencing to achieve sufficient coverage (>10x) or genotype using a high-density SNP array. High marker density (>1 SNP/kb) is critical for power and resolution [19].

2. Data Quality Control (QC)

- Variant Calling: Use standard pipelines (e.g., GATK) to call SNPs and indels.

- Filtering: Apply quality filters, for example:

- Remove SNPs with a high missingness rate (e.g., >10%).

- Remove SNPs with low minor allele frequency (MAF) (e.g., < 5%).

- Exclude individuals with excessive relatedness or population outliers (assessed via Principal Component Analysis).

3. Population Genetic Structure Analysis

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Perform PCA on the genotype data to visualize genetic relationships and confirm population structure [20]. This helps interpret FST results.

4. Calculation of FST

- Method: Use software like VCFtools [20] or PLINK to calculate Weir and Cockerham's FST estimator in sliding windows across the genome (e.g., 20-50 kb windows).

- Command Example (VCFtools):

vcftools --vcf [input.vcf] --weir-fst-pop [pop1.txt] --weir-fst-pop [pop2.txt] --fst-window-size 50000 --fst-window-step 10000 --out [output_prefix]

5. Calculation of Population Branch Statistic (PBS)

- Concept: PBS uses FST values to measure the amount of allele frequency change along the branch of a focal population relative to two outgroups [18].

- Calculation:

- Calculate pairwise FST (focal vs. outgroup1, focal vs. outgroup2, outgroup1 vs. outgroup2).

- Transform FST to genetic distance: T = -log(1 - FST).

- Calculate PBS for the focal population: PBSfocal = (Tf-o1 + Tf-o2 - To1-o2) / 2.

- Normalization: For improved specificity, use rescaled statistics like PBSn1 or Population Branch Excess (PBE) to minimize false positives from background selection or parallel selection [18].

6. Identification of Outlier Loci

- Thresholding: Identify windows or SNPs in the top 1% (or 0.1%) of the empirical FST or PBS distribution as candidate selection signatures.

- Visualization: Generate Manhattan plots to visualize FST/PBS values across the genome and highlight outlier regions.

The following workflow summarizes the key steps in this protocol.

Diagram 2: Workflow for a Population Differentiation Scan. This protocol outlines the steps from sample collection to the identification of candidate genomic regions under selection.

Protocol 2: Detecting Selective Sweeps with Haplotype-Based Statistics (iHS/XP-EHH)

This protocol leverages patterns of extended haplotype homozygosity to detect recent and strong positive selection [17] [19].

1. Phasing and Imputation

- Data Requirement: Haplotype-based methods require phased genotype data.

- Execution: Use phasing software (e.g., SHAPEIT2, Eagle2) with a reference panel (e.g., 1000 Genomes) to infer haplotypes. Impute to a dense reference panel if using array data.

2. Calculation of Integrated Haplotype Score (iHS)

- Objective: To detect ongoing selection within a single population.

- Method: For each SNP in the dataset, the iHS statistic measures the integrated EHH for the ancestral and derived alleles. The score is standardized to have a mean of 0 and variance of 1.

- Software: Use the

rehhpackage in R [19]. - R Code Example:

library(rehh)hap <- data2haplohh("phased_data.hap", "map_file.map")ihs <- scan_hh(hap, polarized = FALSE) # If ancestral state is unknownihs_res <- ihh2ihs(ihs)

3. Calculation of Cross-Population Extended Haplotype Homozygosity (XP-EHH)

- Objective: To detect selection that has driven an allele to near-fixation in one population but not in another.

- Method: XP-EHH compares the integrated EHH for a core haplotype between a test population and a reference population.

- Software: Use the

rehhpackage or standalone scripts. - R Code Example:

xpehh <- calc_cross_ehh(hap_test, hap_ref, mrk = "focal_SNP_name")

4. Normalization and Analysis

- Standardization: Raw iHS/XP-EHH scores are normalized genome-wide. For iHS, the absolute value |iHS| is often used, as selection signals can come from either the ancestral or derived haplotype.

- Outlier Detection: Identify SNPs in the extreme tails of the distribution (e.g., |iHS| > 2, or top 1% of |iHS|/XP-EHH values).

5. Annotation of Candidate Regions

- Gene Mapping: Use genome annotation databases (e.g., ENSEMBL, UCSC Genome Browser) to identify genes located within candidate sweep regions.

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Perform Gene Ontology (GO) or pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., with g:Profiler, Enrichr) to determine if candidate genes are overrepresented in specific biological processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Selection Signature Studies

| Category / Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sample & Data Types | Whole Blood, Tissue Biopsies, DNA Extracts | Source of genomic material for sequencing and genotyping. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) Data | Provides a comprehensive view of genetic variation; superior to arrays for detecting rare variants and fine-mapping [20]. | |

| High-Density SNP Array Data (e.g., Illumina) | A cost-effective alternative to WGS for genotyping common variants in many individuals. | |

| Reference Data | Annotated Reference Genome (e.g., GRCh38, Gallus_gallus-5.0) | Essential for aligning sequence reads and annotating the genomic location of variants [20]. |

| Genetic Recombination Maps | Used by methods like CLR to improve accuracy by modeling local variation in recombination rate [19]. | |

| Functional Genomic Annotations (e.g., ENCODE) | Helps prioritize candidate regions by marking functional elements (coding, regulatory) [21]. | |

| Software & Tools | PLINK [20] | A core toolset for whole-genome association and population-based analysis, including QC and FST. |

| VCFtools [20] | A suite of utilities for working with VCF files, including FST calculation. | |

rehh R package [19] |

Specifically designed for computing iHS, XP-EHH, and related haplotype-based statistics. | |

SweepFinder2, CLR [19] |

Software for implementing the composite likelihood ratio test for selective sweeps. |

Population genomic approaches have revolutionized local adaptation research by enabling researchers to decode the genetic basis of how organisms evolve in response to environmental heterogeneity. By integrating high-throughput sequencing technologies with advanced computational analyses, scientists can now identify adaptive genetic variants across genomes and predict species' vulnerability to rapid environmental change, particularly climate change. This application note explores how model systems from plant, animal, and microbial domains provide critical insights into adaptive mechanisms, focusing on experimental protocols, data interpretation, and practical applications for conservation and resource management.

Table 1: Genomic Insights into Local Adaptation Across Model Systems

Table summarizing key findings from recent studies on local adaptation in various organisms.

| Organism | Sequencing Approach | Sample Size | Key Adaptive Drivers | Candidate Genes/Variants | Application Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Populus koreana (Forest tree) [22] | Whole-genome resequencing (230 individuals) | 24 populations | Climate variables (10 temperature, 9 precipitation factors) | 3,013 SNPs, 378 indels, 44 SVs associated with climate [22] | Predicting climate-induced vulnerability; forest breeding |

| Fragaria nilgerrensis (Wild strawberry) [23] | Whole-genome resequencing (193 individuals) | 28 populations | Environmental and geographic variables | Genomic regions associated with local adaptation to heterogeneous habitats [23] | Crop wild relative utilization; strawberry breeding |

| Actinidia eriantha (Kiwifruit) [24] | Landscape genomics (311 individuals) | 25 populations | Precipitation, solar radiation | AeERF110 involved in adaptation to precipitation and radiation [24] | Conservation prioritization; assessing future adaptation risk |

| Mullus barbatus (Red mullet) [25] | Reduced-Representation Sequencing (771 individuals) | Mediterranean-wide | Environmental gradients | Candidate loci linked to ontogeny and environmental adaptation [25] | Sustainable fishery management |

Experimental Protocols for Local Adaptation Studies

Protocol 1: Whole-Genome Resequencing for Detecting Local Adaptation

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

- Population Sampling: Collect tissue samples (leaves, fins, etc.) from 20-30 populations across environmental gradients. For Populus koreana, 230 individuals from 24 populations were sampled [22].

- DNA Extraction: Use high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA extraction kits (e.g., Nanobind Tissue Big DNA kit) for long-read sequencing. Verify DNA quality via UV/VIS spectrophotometry, fluorometry, and capillary electrophoresis [25].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Long-Read Sequencing: Prepare libraries for Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) or PacBio systems. For ONT, use the 1D Genomic DNA by ligation protocol (SQK-LSK109). Sequence on PromethION flow cells [25].

- Short-Read Sequencing: Utilize Illumina platforms for high-coverage sequencing. Average depth of ~27.4× was achieved for P. koreana with 94.6% coverage [22].

- Hi-C Library Preparation: Use Dovetail Genomics Omni-C kit for chromatin interaction data to scaffold assemblies. Sequence on Illumina NovaSeq in paired-end mode [25].

- RNA Sequencing: Extract RNA from multiple tissues using kits (e.g., Quick-RNA Miniprep Plus). Prepare libraries with Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep kit for transcriptome validation [25].

Data Processing and Genome Assembly

- Basecalling and Filtering: Perform high-accuracy basecalling with Guppy (v5.0.13). Filter reads with Filtlong (v0.2.1) for minimum length and quality [25].

- Genome Assembly: Assemble genomes using integrated data from multiple technologies. The P. koreana assembly captured 401.4 Mb with contig N50 of 6.41 Mb and 97.8% BUSCO completeness [22].

- Variant Calling: Identify SNPs, indels, and structural variations (SVs) using alignment tools (e.g., BWA) and variant callers (e.g., GATK). For P. koreana, 16,619,620 high-quality SNPs, 2,663,202 indels, and 90,357 SVs were identified [22].

Protocol 2: Genotype-Environment Association (GEA) Analysis

Environmental Data Collection

- Climate Data: Obtain 19+ bioclimatic variables from WorldClim or similar databases, including temperature and precipitation metrics [22] [24].

- Geographic Data: Record latitude, longitude, and altitude for each sampling site [23].

Statistical Analysis

- Latent Factor Mixed Models (LFMM): Implement LFMM to test genotype-environment associations while accounting for population structure. In P. koreana, this identified 3,013 climate-associated SNPs [22].

- Redundancy Analysis (RDA): Use RDA to partition genomic variation between environmental and geographic factors. For F. nilgerrensis, RDA revealed environment explains more variation than geography [23].

- Selective Sweep Scans: Employ statistical tests (Tajima's D, π, FST) to detect signatures of selection. F. nilgerrensis populations showed distinct Tajima's D values indicating differential selection pressures [23].

Vulnerability Assessment

- Genetic Offset: Model the genetic composition change required to track future environments using climate projections [22].

- Risk Prioritization: Identify high-risk populations facing greatest challenges under climate change scenarios. For A. eriantha, middle and east clusters showed highest vulnerability [24].

Visualization of Research Workflows

Genomic Local Adaptation Workflow

Diagram illustrating the comprehensive workflow for identifying locally adaptive genetic variation, from sample collection to practical application.

GEA Analysis Pipeline

Diagram showing the key analytical steps in genotype-environment association studies, from data input to identifying adaptive loci.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Population Genomic Studies

Comprehensive list of key reagents, kits, and platforms used in local adaptation research.

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Application in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Nanobind Tissue Big DNA kit (PacBio) | High-molecular-weight DNA extraction for long-read sequencing | Used for Mullus barbatus genome assembly [25] |

| Long-Read Sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) PromethION | Generating long reads for genome assembly and structural variant detection | P. koreana genome: ~42.42 Gb of Nanopore data [22] |

| Short-Read Sequencing | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | High-coverage resequencing for variant calling | Mullus barbatus Hi-C and RNA library sequencing [25] |

| Hi-C Library Prep | Dovetail Genomics Omni-C kit | Chromatin interaction mapping for chromosome-scale scaffolding | Mullus barbatus chromosome-level assembly [25] |

| RNA Extraction | Quick-RNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research) | High-quality RNA isolation for transcriptome sequencing | Mullus barbatus transcriptome from multiple tissues [25] |

| Variant Calling | Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) | Identifying SNPs, indels from sequencing data | Standard pipeline for population SNP datasets [22] |

| GEA Analysis | Latent Factor Mixed Models (LFMM) | Detecting genotype-environment associations | Identified 3,013 climate-associated SNPs in P. koreana [22] |

| Population Genomics | ADMIXTURE, PCA, FST statistics | Inferring population structure and differentiation | Revealed 3 genetic clusters in P. koreana [22] |

Data Interpretation and Application

Population genomic studies of local adaptation generate complex datasets requiring careful biological interpretation. Key considerations include distinguishing true adaptive signals from false positives caused by population structure, understanding the polygenic nature of most adaptive traits, and translating genomic findings into practical conservation strategies.

The genetic variants identified through GEA analyses can inform conservation priorities by identifying populations most vulnerable to future climate change. For species of economic importance, these adaptive markers can guide breeding programs aimed at enhancing climate resilience. The protocols and applications outlined here provide a framework for advancing local adaptation research across diverse model systems.

A Practical Guide to Genomic Scans for Selection: Methods and Real-World Applications

Differentiation Outlier Methods (e.g., FST-based Scans)

Differentiation outlier methods are a cornerstone of population genomics, enabling researchers to identify genetic loci under spatially divergent selection by analyzing patterns of genetic differentiation among populations. The foundational principle of these methods is that loci involved in local adaptation often exhibit levels of genetic differentiation that are significantly higher than the background genome-wide average, which is shaped primarily by neutral processes such as genetic drift and gene flow [16]. When natural selection acts differently on a trait across various habitats—for example, due to differences in climate or soil composition—the allele frequencies at loci underlying that trait will diverge more rapidly between populations than neutral loci. By scanning the genome for these statistical "outliers," researchers can pinpoint candidate genes for adaptive traits without prior knowledge of the specific selective pressures involved [16].

The history of these methods dates back to the Lewontin-Krakauer test developed in the 1970s [26]. However, the field has advanced dramatically with the advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies, which provide the vast number of genome-wide markers needed to distinguish the signal of selection from the noise of demographic history. Today, FST-based genome scans are widely used in ecological and evolutionary genetics to uncover the genetic basis of adaptation in natural populations, with applications ranging from understanding fundamental evolutionary processes to informing the conservation and management of species [16].

Key Methodological Approaches

Differentiation outlier methods can be broadly categorized based on their underlying assumptions about population structure and demography. The following table summarizes the core features of several prominent methods.

Table 1: Key Differentiation Outlier Methods for Detecting Local Adaptation

| Method Name | Underlying Principle | Key Assumption | Handles Complex Demography? | Reference/Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDIST2 | Identifies outliers from an expected neutral FST distribution generated via coalescent simulation under an island model. |

Populations evolve independently according to an island model. | No | [26] |

| BayeScan | Uses a Bayesian approach to partition locus-specific (α) and population-specific (β) effects on FST. |

Samples represent populations that have evolved independently from a common ancestor (multinomial-Dirichlet distribution). | No | [26] [27] |

| BayeScEnv | An extension of the BayeScan model that incorporates environmental data to distinguish selection from other confounding factors. | Considers two locus-specific effects: divergent selection and other non-adaptive processes. | Yes, more robust than BayeScan | [27] |

| FLK | Extends the Lewontin-Krakauer test by accounting for population relationships using a phylogenetic tree of coancestry. | Population tree accurately reflects shared evolutionary history. | Yes | [26] |

| pcadapt | Uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify loci excessively associated with population structure. | Major axes of genetic variation reflect population structure; outliers are loci disproportionately contributing to this structure. | Yes, through PCA | [28] |

| OutFLANK | Estimates the neutral distribution of FST using a chi-squared approximation based on the distribution's median, reducing sensitivity to outliers. |

The true neutral FST distribution can be approximated from the central mass of observed FST values. |

Yes, robust to some demographic complexities | [28] |

Critical Considerations for Method Selection

The choice of method is critical and is heavily influenced by a population's demographic history. Methods like FDIST2 and BayeScan that assume an island model or independent population history are highly susceptible to false positives when this assumption is violated [16] [26]. Common demographic scenarios such as isolation-by-distance (IBD) and range expansion can create idiosyncratic patterns of genetic differentiation that mimic the effect of selection. For instance, during a range expansion, "allele surfing" can cause alleles to drift to high frequency at the leading edge, creating false signatures of selective sweeps [16].

Therefore, in species with known or suspected complex demography, methods that explicitly account for population structure—such as FLK, BayeScEnv, pcadapt, and OutFLANK—are generally recommended. These methods either estimate a covariance matrix among populations (Bayenv2), infer a population tree (FLK), or use principal components (pcadapt) to establish a more realistic null model, thereby substantially reducing false-positive rates [26] [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

General Workflow forFSTOutlier Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the overarching workflow for a typical differentiation outlier analysis, from data preparation to validation.

Protocol 1: Outlier Detection with pcadapt

The pcadapt method transforms genotype data into principal components (PCs) and identifies outliers as SNPs with excessive association to these major axes of genetic variation [28].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for pcadapt Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Genotype Data | Input data containing individual genotypes for numerous SNPs. | Often in VCF (Variant Call Format) format. |

| R Statistical Software | Platform for running the pcadapt package and associated analyses. | Version 3.6.1 or higher. |

pcadapt R package |

Contains functions to read genetic data, perform PCA, and compute outlier statistics. | Version 4.3.3 or higher. |

qvalue R package |

Used to correct p-values for multiple testing and control the False Discovery Rate (FDR). | Critical for determining significant outliers. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Import and Preparation: Read the genotype data (e.g., VCF file) into R using

read.pcadapt. This function converts the data into the specialized format required by the package [28].Perform PCA and Determine Optimal Number of Components (K): Run the PCA on the genetic data. Use a scree plot of the resulting object to visualize the proportion of variance explained by each PC and choose an appropriate

K[28].Compute and Visualize p-values: The function computes p-values for each SNP testing the null hypothesis of no association with the first

KPCs. A Manhattan plot provides a visual summary of these p-values across the genome [28].Correct for Multiple Testing and Identify Outliers: Apply an FDR correction to the p-values using the

qvaluepackage. SNPs with a q-value below a chosen threshold (e.g., 0.1) are declared significant outliers [28].

Protocol 2: Outlier Detection with OutFLANK

OutFLANK employs an FST-based approach designed to be robust to modest departures from simple demographic models by estimating the neutral FST distribution from the central mass of the data [28].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation with vcfR: Use the

vcfRpackage to read the VCF file and extract the genotype matrix. The data may need to be converted from VCF format to a genotype matrix compatible with OutFLANK [28].Calculate

FSTand Other Necessary Statistics: Use OutFLANK's functions to compute theFSTfor each locus and the necessary accompanying statistics (e.g., heterozygosity) [28].Estimate the Neutral

FSTDistribution: OutFLANK fits a chi-squared distribution to the central portion of the observedFSTvalues, trimming the extreme tails to reduce the influence of potential selected loci on the null model [28].Identify Outliers: The method calculates p-values for each locus based on the fitted null distribution. Loci with significantly high

FSTafter multiple-testing correction are considered candidates for selection [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful execution of a differentiation outlier study requires a suite of bioinformatic tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | DNA Extraction Kit | High-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA isolation from tissue or blood samples. |

| SNP Genotyping Array / Sequencing Kit | Platform for generating raw genotype data (e.g., Illumina Infinium arrays, Illumina sequencing kits). | |

| Software & Packages | PLINK | Pre-processing and quality control (QC) of genotype data (filtering, pruning). |

| R Studio & R Packages | Statistical computing environment; essential packages include pcadapt, vcfR, qvalue, and OutFLANK. |

|

| BayeScan | Standalone software for Bayesian outlier detection. | |

| GENEPOP | Software for calculating basic population genetic statistics, including FST. |

|

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for managing large genomic datasets and running computationally intensive analyses. |

Analysis of a Case Study: Local Adaptation in Red Coral

A study on the red coral, Corallium rubrum, provides a compelling real-world application of these methods. Researchers used RAD sequencing to analyze the genetic structure of six pairs of shallow versus deep populations across three geographical regions [29]. The species is known to be highly genetically structured, and the goal was to detect signals of local adaptation to depth and thermal regime.

The analysis revealed significant genetic differentiation not only among the three geographical regions but also between shallow and deep populations within regions, separated by as little as 20 meters depth [29]. Subsequent genomic scans identified several candidate loci under selection. However, the authors highlighted a major methodological challenge: in a "strongly genetically structured species," it is difficult to distinguish true signals of local adaptation from the confounding effects of population history, potentially leading to a high false-positive rate [29]. This case underscores the critical importance of using robust methods and a well-replicated sampling design to separate authentic adaptive signals (the "wheat") from spurious signals generated by demography (the "chaff") [29].

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Integrating Environmental Data

There is a growing trend towards integrating outlier approaches with Genetic-Environment Association (GEA) analyses. GEAs test for direct correlations between allele frequencies and specific environmental variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation). Combining these two approaches can provide stronger evidence for local adaptation, as it both identifies differentiated loci and proposes a possible selective agent [16]. Newer methods like BayeScEnv are explicitly designed to incorporate environmental data directly into the FST outlier model, which helps to lower the false-positive rate by distinguishing selection from other non-adaptive processes that can create differentiation, such as range expansions [27].

The Critical Role of a Neutral Locus Set

A powerful strategy to improve the reliability of any outlier method is to use a empirically derived null distribution. This involves identifying a set of putatively neutral loci—for example, SNPs in non-coding, intergenic regions—to characterize the genome-wide background distribution of FST [26]. This empirical null can then be used to assess the significance of FST values for other loci. Studies have shown that using such a neutral parameterization set consistently improves the performance of methods like FLK and Bayenv2, and is crucial for obtaining reliable results with any method under complex demography [26].

Future Outlook

As sequencing costs continue to fall, the use of whole-genome sequencing data will become standard. This will allow for more powerful scans and the ability to detect selection on rare variants and in more complex genomic regions. Furthermore, the integration of outlier scans with functional genomics data (e.g., gene expression, epigenomics) will be essential for moving from a list of candidate SNPs to a mechanistic understanding of how these genetic variants contribute to adaptive phenotypes [16].

Genotype-Environment Association (GEA) Analyses

Genotype-Environment Association (GEA) analyses represent a powerful landscape genomic approach to identify putative adaptive genetic variation by correlating allele frequencies with environmental variables across natural populations [30]. In the context of local adaptation research, GEAs serve as a screening tool to detect genetic loci potentially under environmentally driven selection, thereby illuminating the molecular basis of how populations adapt to their local conditions [31] [30]. The fundamental premise is that loci involved in local adaptation will exhibit allele frequency clines along environmental gradients, such as temperature, precipitation, or specific soil properties [32]. As climate change accelerates, understanding this genetic architecture of adaptation has become crucial for predicting species' responses and informing conservation strategies [22]. This protocol outlines the implementation of GEA analyses, from study design to experimental validation, providing a framework for researchers investigating local adaptation in natural populations.

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for conducting GEA studies, integrating both computational and experimental components.

Key Experimental Findings and Validations

Experimental Validation of GEA Candidates

Table 1: Experimental Validation of GEA-Identified Genes in Arabidopsis thaliana

| Gene | GEA Source | Experimental Approach | Key Validated Phenotypes | G×E Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WRKY38 | Moisture-associated GEA [31] | t-DNA knockout mutants | Decreased stomatal conductance, reduced specific leaf area under drought | Significant G×E for fitness traits |

| LSD1 | Moisture-associated GEA [31] | t-DNA knockout mutants | Altered flowering time under drought conditions | Significant G×E for flowering time |

| Additional Genes | Three moisture GEA studies [31] | Screening of 42 t-DNA knockout lines | Flowering time effects with no drought interaction | 11 genes showed effects |

GEA Applications Across Taxa

Table 2: GEA Case Studies Across Different Organisms

| Species | Study Focus | Environmental Variables | Key Adaptive Loci | Spatial Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabis alpina (Alpine rockcress) | Effect of topographic variable resolution [33] | High-resolution DEM derivatives (0.5-16m) | Topography-associated variants | Micro-geographic (4 alpine valleys) |

| Hermit thrush (Catharus guttatus) | Climate adaptation across range [32] | Temperature, precipitation | Temperature-associated loci | Macro-geographic (continental range) |

| Populus koreana (Poplar) | Climate vulnerability assessment [22] | 19 climate variables (10 temperature, 9 precipitation) | 3,013 SNPs, 378 indels, 44 SVs | Landscape (East Asian distribution) |

| U.S. Red Angus cattle | Growth trait G×E [34] | Climate ecoregions | 14 significant G×E interactions for growth | Management units |

Detailed Methodologies

Population Sampling and Genomic Data Generation

Proper study design begins with strategic population sampling across environmental gradients. For non-model organisms, whole-genome resequencing provides the most comprehensive variant discovery, while reduced-representation approaches like RADseq offer cost-effective alternatives.

- Sample Collection: Target 20-30 populations across the environmental gradient of interest, with 10-20 individuals per population to capture within-population variation [32] [22]. For fine-scale studies, sampling at multiple spatial resolutions (0.5-16m) can reveal microgeographic adaptation [33].

- DNA Extraction: Use high-molecular-weight DNA extraction kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy) suitable for whole-genome sequencing. Quality control should include fluorometric quantification and fragment analysis.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: For whole-genome resequencing, prepare Illumina short-read libraries (350-500bp insert size) and sequence to a minimum coverage of 20-30×, as achieved in the Populus koreana study [22]. For large genomes, consider cost-effective reduction techniques like target capture or RADseq.

Environmental Data Collection and Processing

Environmental variables should be carefully selected based on hypothesized selective pressures and processed at appropriate spatial resolutions.

- Climate Data: Source from WorldClim, CHELSA, or other climate databases at resolutions matching your sampling scale (30 arc-seconds ~1km is common) [32].

- Topographic Variables: Derive from Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) using GIS software. Primary attributes include slope, aspect, curvature; secondary attributes include solar radiation, topographic wetness index, and vector ruggedness [33].

- Spatial Resolution Testing: Implement a multi-scale approach by generalizing fine-resolution DEMs (e.g., 0.5m) to coarser resolutions (e.g., 2m, 4m, 8m, 16m) to identify the most relevant scale for each variable type [33].

- Variable Selection: Use forward selection procedures or collinearity analysis to reduce environmental variable dimensionality before GEA analysis [33].

Genotype-Environment Association Analysis

Multiple statistical approaches exist for detecting GEAs, each with strengths and limitations.

Table 3: Comparison of GEA Analytical Methods

| Method | Statistical Approach | Traits Supported | Population Structure Control | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LFMM (Latent Factor Mixed Models) | Mixed model with latent factors [22] | Quantitative, Binary | Latent factors | Lower power for polygenic adaptation |

| RDA (Redundancy Analysis) | Multivariate constrained ordination [33] | All trait types | Conditioning on covariates | Higher power for polygenic adaptation; robust to demography |

| Gradient Forest | Machine learning, random forests [32] | All trait types | Limited inherent control | Captures non-linear relationships; identifies allele turnover points |

| Univariate Linear Models | Single-locus regression [34] | Quantitative, Binary | PCA covariates | Higher false positive rates; requires careful multiple testing correction |

The analytical framework for these methods involves several key steps as visualized below:

Experimental Validation of GEA Candidates

Validation is crucial for confirming the adaptive role of GEA-identified loci. Multiple experimental approaches can be employed:

- Common Garden Experiments: The gold standard for detecting local adaptation through genotype-by-environment (G×E) interactions for fitness [30]. Grow genotypes from multiple environments in controlled conditions to isolate genetic effects.

- Functional Genetics in Model Systems: Use T-DNA insertion lines (in Arabidopsis), CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, or RNAi to create knockouts of candidate genes and test phenotypes under environmental treatments [31].

- Near-Isogenic Lines (NILs): Introgress candidate alleles into different genetic backgrounds to test their effects in isolation, though this is time-consuming [31].

- Physiological Phenotyping: Measure ecophysiological traits relevant to the environmental gradient (e.g., stomatal conductance, water use efficiency, photosynthetic rates) to link genotypes to adaptive mechanisms [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GEA Studies

| Category | Item/Reagent | Function/Application | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Reagents | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality DNA extraction | [32] [22] |

| Illumina DNA Prep kits | Library preparation for WGS | [22] | |

| T-DNA insertion mutants | Functional validation of candidate genes | [31] | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | LFMM Software | GEA analysis with latent factors | [22] |

| RDA in R (vegan package) | Multivariate GEA analysis | [33] | |

| Gradient Forest | Machine learning GEA approach | [32] | |

| PLINK/GEMMA | Genome-wide association analysis | [34] | |

| Environmental Data | WorldClim/CHELSA | Historical climate data | [32] [22] |

| Digital Elevation Models | Source for topographic variables | [33] | |

| Google Earth Engine | Environmental data processing platform | - |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

- Population Structure: Control for confounding effects of demographic history using latent factors (LFMM), principal components, or kinship matrices [30] [22].

- Spatial Autocorrelation: Account for spatial non-independence using MEMs (Moran's Eigenvector Maps) or spatial cross-validation [32].

- Multiple Testing: Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction rather than Bonferroni due to linkage disequilibrium among markers [31].

- Sample Size: Power simulations suggest larger samples (n>500) are often needed to detect G×E interactions [35].

- Environmental Variable Resolution: Test multiple spatial resolutions (0.5-90m) as optimal grain size depends on variable type, terrain, and study extent [33].

Landscape genomics is an emerging interdisciplinary field that combines population genomics, spatial statistics, and landscape ecology to identify genetic variants underlying local adaptation to environmental heterogeneity [36] [37]. This approach investigates how spatial and environmental factors shape genomic variation, providing insights into the genetic basis of adaptive traits and evolutionary potential of populations [38]. The core premise of landscape genomics is that natural selection leaves detectable signatures in the genome—alleles associated with survival and reproduction in specific environments become more frequent in populations experiencing those conditions [37]. By analyzing genome-environment associations, researchers can identify candidate loci involved in local adaptation without prior knowledge of phenotypes, making this approach particularly valuable for non-model organisms and ecological studies [39].

The field has significant implications for conservation biology, agricultural science, and understanding evolutionary processes in wild populations. For conservation, landscape genomics helps predict population vulnerability to climate change by quantifying the mismatch between current adaptive genotypes and future environmental conditions [40] [38]. In agriculture, it facilitates the identification of genetic variants valuable for breeding stress-resilient crops by studying landraces and wild relatives that have adapted to diverse environments [41] [36]. The rapid advancement of genomic sequencing technologies has enabled the generation of high-density genome-wide markers, making landscape genomics increasingly accessible and powerful for studying local adaptation across diverse taxa [42].

Fundamental Principles and Key Concepts

Neutral versus Adaptive Genetic Variation

A fundamental distinction in landscape genomics is between neutral and adaptive genetic variation. Neutral variation refers to genetic differences not influenced by natural selection, primarily shaped by demographic history, gene flow, and genetic drift [39]. In contrast, adaptive variation results from natural selection, where certain alleles enhance fitness in specific environments [37]. Landscape genomics employs various statistical methods to distinguish these processes by determining whether patterns of genetic differentiation exceed neutral expectations or correlate with environmental parameters after accounting for neutral population structure [39] [38].

Isolation by distance (IBD) and isolation by environment (IBE) represent two key frameworks for understanding spatial genetic patterns. IBD describes the pattern where genetic differentiation increases with geographic distance due to limited dispersal [42]. IBE occurs when genetic differentiation increases with environmental dissimilarity, regardless of geographic distance, suggesting local adaptation [42]. Many natural systems exhibit a combination of both processes, requiring analytical approaches that can disentangle their relative contributions [39].

Genomic Signature of Local Adaptation

Local adaptation produces characteristic genomic signatures through spatial variation in selection pressures. These signatures manifest as: (1) elevated genetic differentiation at specific loci compared to neutral background (( F_{ST} ) outliers); (2) significant correlations between allele frequencies and environmental variables; and (3) allelic turnover along environmental gradients [39] [37] [38]. The polygenic nature of many adaptive traits means that local adaptation often involves subtle allele frequency shifts at multiple loci rather than fixed differences at single genes [41].

Genomic vulnerability (also called genomic offset) represents a key application of these principles, measuring the degree of maladaptation expected under environmental change by quantifying the difference between current adaptive genotypes and those required for future conditions [39] [40] [38]. This predictive framework helps identify populations at greatest risk from climate change and informs conservation strategies such as assisted gene flow [40] [38].

Experimental Design and Data Requirements

Sampling Strategies

Effective landscape genomic studies require careful sampling designs that adequately represent both geographic and environmental spaces. Individual-based sampling has become increasingly favored over population-based approaches due to several advantages: broader geographic coverage, finer spatial resolution, and lower impact on vulnerable populations [42]. With genomic data, even single individuals per location can provide robust inferences when many markers are analyzed, as each locus represents an independent realization of evolutionary processes [42].

Sampling should encompass the environmental heterogeneity across the species' range, particularly including marginal habitats and environmental extremes where strong selection pressures may operate [42]. This strategy increases power to detect genotype-environment associations and captures a broader spectrum of adaptive variation. For example, a study of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum across subtropical China sampled 156 individuals from 24 sites spanning 18° of longitude, 13° of latitude, and 1,000 m of elevation to capture environmental gradients [39].

Table 1: Comparison of Sampling Strategies in Landscape Genomics

| Strategy | Spatial Resolution | Environmental Coverage | Impact on Populations | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-based | High (many sites, few individuals each) | Broad, captures environmental heterogeneity | Low, minimal disturbance | Conservation of threatened species, widespread species |

| Population-based | Lower (fewer sites, many individuals each) | Limited by fewer locations | Higher, requires more individuals | Species with clear population boundaries, phenotypic studies |

Landscape genomics integrates three primary data types: genomic, environmental, and spatial. Genomic data ranges from targeted SNP arrays to whole-genome sequencing, with density depending on research questions and resources [41] [37]. Environmental data typically includes climatic variables (temperature, precipitation), edaphic factors (soil properties), and topographic features (elevation, slope) [39] [37]. Spatial data consists of geographic coordinates and derived predictors like geographic distance matrices.

Table 2: Essential Data Types for Landscape Genomic Studies

| Data Category | Specific Variables | Common Sources | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic | SNPs, indels, structural variants | RAD-seq, GBS, WGS, SNP arrays | Marker density, genome coverage, missing data |

| Environmental | Temperature, precipitation, UV radiation, soil pH | WorldClim, CHELSA, SoilGrids | Spatial resolution, temporal matching with sampling |

| Spatial | Latitude, longitude, elevation, geographic distances | GPS, digital elevation models | Projection systems, spatial autocorrelation |

The SoySNP50K array provided 42,080 markers for studying environmental adaptation in soybean germplasm [41], while genotyping-by-sequencing approaches generated 37,636 high-quality SNPs for naked barley landraces on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau [37]. Reduced-representation sequencing like SLAF-seq identified 30,252 SNPs for Tetrastigma hemsleyanum across subtropical China [39]. Environmental data is often obtained from global databases like WorldClim, which provides 30+ bioclimatic variables at resolutions from 30 seconds to 2.5 minutes [39] [37].

Analytical Framework and Workflow

Core Analytical Pipeline

Landscape genomic analysis follows a structured workflow from raw data processing to biological interpretation. The initial quality control steps include filtering markers based on missing data, minor allele frequency, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [37]. For SNP datasets from sequencing approaches, this involves alignment to reference genomes, variant calling, and stringent filtering [39] [37].

The core analysis consists of three complementary approaches: (1) population genomic analysis to characterize neutral structure; (2) outlier detection to identify loci under selection; and (3) environment association analysis to link genetic variation with environmental gradients [39] [38]. Population structure is typically inferred using methods like ADMIXTURE, TESS, or DAPC, which identify genetic clusters and estimate individual ancestry coefficients [41] [39]. These population structure estimates are crucial covariates in subsequent analyses to avoid spurious associations [39].

Statistical Methods for Detecting Local Adaptation

Outlier Tests identify loci with exceptionally high genetic differentiation compared to neutral expectations. These methods include FST-based approaches like BayeScan, Arlequin, and pcadapt that detect loci potentially under divergent selection [39] [38]. For example, in a study of Quercus rugosa, 74 FST outlier SNPs were identified from 5,354 markers, suggesting potential local adaptation [38].

Environment Association Analysis (EAA) tests for statistical relationships between allele frequencies and environmental variables while controlling for population structure. Common methods include Redundancy Analysis (RDA), Latent Factor Mixed Models (LFMM), and Gradient Forests (GF) [39] [42]. RDA combines multiple regression and principal components analysis to identify multivariate associations between genetic and environmental data [42]. LFMM uses a Bayesian approach to account for unobserved confounders that might create spurious associations [42]. In the Tetrastigma hemsleyanum study, EAA identified 275 candidate adaptive SNPs along genetic and environmental gradients [39].

Gradient Forests and Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling (GDM) are nonlinear, multivariate methods that model allele frequency turnover along environmental gradients [39] [38]. These approaches can handle complex, non-linear relationships and identify environmental variables with the strongest influence on genetic composition. In Quercus rugosa, GF analysis revealed that precipitation seasonality was the strongest predictor of genetic structure [38].

Application Notes: Case Studies Across Taxa

Crop Plants: Soybean and Barley

Soybean germplasm accessions from the USDA collection (N = 17,019) were analyzed using landscape genomics to identify genomic regions involved in environmental adaptation [41]. Population structure analysis revealed distinct Chinese subpopulations, and genotype-environment associations identified genes involved in flowering regulation, photoperiodism, and stress response cascades [41]. The study recovered previously known flowering time genes (E1-E4 loci) and discovered new candidate genes, demonstrating the polygenic nature of environmental adaptation in soybean [41]. Analysis of haplotype distribution in North American and European cultivars showed that while early maturity haplotypes have been selected during breeding, many putative adaptive haplotypes for cold regions remain underrepresented in modern cultivars [41].

Naked barley landraces from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau were studied to understand adaptation to extreme conditions including high UV radiation, low temperatures, and variable precipitation [37]. Genotyping-by-sequencing of 157 accessions yielded 37,636 high-quality SNPs for analysis [37]. The study identified 136 signatures associated with temperature, precipitation, and ultraviolet radiation, with 13 showing pleiotropic effects [37]. Genes involved in cold stress and flowering time regulation were detected near significant associations, including the known gene HvSs1 [37].

Wild Plants: Trees and Medicinal Herbs

Quercus rugosa, a widespread oak species in Mexico, was studied using landscape genomics to inform conservation under climate change [38]. Researchers identified 74 FST outlier SNPs and 97 environment-associated SNPs from 5,354 markers genotyped across 103 individuals from 17 sites [38]. Gradient Forests modeling revealed that precipitation seasonality and geographic distance were the strongest predictors of genetic structure [38]. The study mapped genomic vulnerability under future climate scenarios, identifying populations likely to experience the greatest maladaptation [38].

Tetrastigma hemsleyanum, a perennial herb in subtropical China, was investigated using 30,252 SNPs from 156 individuals across 24 populations [39]. Multivariate methods determined that climate explained more genomic variation than geographical distance, with winter precipitation as the strongest predictor [39]. The study identified 275 candidate adaptive SNPs with functions related to flowering time and abiotic stress response [39]. Genomic vulnerability analysis revealed central-northern populations faced the highest risk under future climate, informing targeted conservation efforts [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Landscape Genomics

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Examples/Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|