Phylogenomic Comparative Methods: A Modern Framework for Biodiversity Discovery and Biomedical Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of phylogenomic comparative methods (PCMs) in biodiversity science.

Phylogenomic Comparative Methods: A Modern Framework for Biodiversity Discovery and Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of phylogenomic comparative methods (PCMs) in biodiversity science. It covers foundational principles, from distinguishing PCMs from traditional phylogenetics to defining key metrics like phylogenetic diversity. The piece details cutting-edge methodological approaches, including software pipelines and core gene sets, for analyzing evolutionary patterns and processes. Crucially, it addresses common pitfalls and biases in phylogenetic analysis, offering strategies for troubleshooting and model validation. Finally, it explores rigorous validation techniques and comparative frameworks, demonstrating how phylogenomic insights can fuel discovery in evolutionary biology, conservation prioritization, and the search for novel biomolecules.

Laying the Groundwork: From Basic Phylogenetics to Phylogenomic Comparative Methods

Defining Phylogenomic Comparative Methods and Their Core Objectives

Phylogenomic comparative methods (PCMs) represent the integration of principles from phylogenetic comparative methods with genome-scale datasets to analyze trait evolution and biodiversity patterns. These methods have revolutionized evolutionary biology by enabling researchers to study how traits evolve across species while accounting for their shared evolutionary history, using hundreds to thousands of genomic loci instead of just a few genes [1] [2]. The core objective of these methods is to understand the tempo and mode of trait evolution—how quickly traits change and the patterns these changes follow—while properly accounting for the complex phylogenetic relationships that arise from genomic data [2]. This is particularly crucial in biodiversity research, where understanding evolutionary relationships helps guide conservation priorities, inform species delimitation, and reveal evolutionary processes that generate and maintain biological diversity [3] [4].

A fundamental challenge addressed by phylogenomic comparative methods is phylogenetic non-independence—the statistical issue that closely related species tend to share similar traits due to common ancestry rather than independent evolution [1]. Early phylogenetic comparative methods, developed since the 1980s, provided initial approaches to account for this non-independence, but were typically limited to single-gene trees or morphological data [1] [5]. The advent of modern genomics has revealed that genomes are often composed of mosaic histories with different parts having independent evolutionary paths that disagree with each other and with the species tree—a phenomenon known as gene tree discordance [2]. Phylogenomic comparative methods specifically extend traditional approaches to handle this genomic complexity, providing more accurate inferences about evolutionary processes across the tree of life [2] [4].

Key Concepts and Biological Significance

Fundamental Concepts in Phylogenomic Comparative Methods

Gene tree discordance occurs when individual loci have evolutionary histories that conflict with each other and with the overall species phylogeny [2]. This discordance arises primarily from two biological processes: incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), where ancestral genetic polymorphisms persist through multiple speciation events, and introgression, which involves historical hybridization and gene flow between species [6] [2]. The presence of widespread discordance has profound implications for comparative methods because evolution along discordant gene tree branches can produce trait similarities among species that lack shared history in the species tree, potentially leading to incorrect evolutionary inferences when using standard comparative approaches [2].

The problem of hemiplasy emerges when single trait transitions on discordant gene trees falsely appear as homoplasy (convergent evolution) when analyzed solely on the species tree [2]. This can mislead researchers into overestimating the number of trait transitions or the rate of trait evolution [2]. Phylogenomic comparative methods address this challenge by incorporating the entire distribution of gene trees, rather than relying on a single species tree, thereby capturing the complete evolutionary history that has shaped trait variation [2].

Biological and Conservation Significance

In practical applications, phylogenomic comparative methods have become indispensable for biodiversity assessment and conservation prioritization [4]. The increased resolution provided by genomic data can reveal previously unrecognized population structure and cryptic species diversity, directly informing conservation decisions [4]. For example, these methods have been used to delineate taxonomic units in the Greater Short-horned Lizard complex and to identify repeated hybridization events in Liolaemus lizards, necessitating revisions to taxonomic and conservation units [4]. This is particularly important in legal frameworks where species protection often depends on taxonomic distinctiveness [4].

The NSF's Systematics and Biodiversity Science Cluster highlights the importance of this research by specifically funding projects that use "phylogenetic comparative studies to biogeographic and exploratory biodiversity studies" [3]. Such support acknowledges that phylogenomic comparative methods address fundamental biological questions about what organisms exist, how they are related, and how phylogenetic history illuminates evolutionary patterns and processes in nature [3]. As biodiversity faces unprecedented threats in the Anthropocene, these methods provide crucial insights for understanding the evolution of life on Earth, guiding environmental policy, and informing conservation strategies [4].

Comparative Framework: Traditional vs. Phylogenomic Approaches

Table 1: Comparison between Traditional Comparative Methods and Phylogenomic Comparative Methods

| Aspect | Traditional Comparative Methods | Phylogenomic Comparative Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Framework | Single species tree | Distribution of gene trees plus species tree |

| Data Requirements | Few genes or morphological traits | Hundreds to thousands of genomic loci |

| Handling of Discordance | Typically ignored or addressed via simple models | Explicitly incorporated through covariance matrices or multi-tree approaches |

| Assumptions About Trait Evolution | Evolution follows species tree | Evolution follows the heterogeneous history across the genome |

| Primary Analytical Challenges | Phylogenetic non-independence | Gene tree discordance, hemiplasy, and computational complexity |

| Covariance Structure | Simple tree-based covariances (C matrix) | Comprehensive covariances incorporating discordance (C* matrix) |

| Applications in Conservation | Limited resolution for recently diverged groups | Fine-scale population structure and cryptic species detection |

The fundamental difference between traditional and phylogenomic approaches lies in how they model evolutionary relationships. Traditional phylogenetic comparative methods use a single phylogenetic tree to account for shared evolutionary history, calculating expected trait variances and covariances based on this tree structure [2]. In contrast, phylogenomic comparative methods incorporate the full distribution of gene trees, recognizing that different genomic regions may have distinct evolutionary histories due to incomplete lineage sorting, introgression, or other population-level processes [2].

The statistical implications of this distinction are substantial. When analyses rely solely on the species tree, they fail to account for evolutionary processes along discordant branches, potentially resulting in overestimated evolutionary rates and incorrect inferences about the number and direction of trait transitions [2]. For example, standard Brownian motion models applied to species trees may incorrectly estimate the evolutionary rate parameter (σ²) when gene tree discordance is present, with simulations showing that failure to account for discordance can bias estimates upward [2]. Phylogenomic comparative methods correct for these biases by incorporating the complete evolutionary history captured across the genome.

Protocols for Phylogenomic Comparative Analysis

Protocol 1: Updated Variance-Covariance Matrix Approach

The variance-covariance matrix approach provides a framework for incorporating gene tree discordance into comparative analyses without requiring specialized software. This method develops an updated phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix (denoted C*) that includes covariances introduced by discordant gene trees [2].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Gene Tree Collection: Obtain a set of gene trees with branch lengths, either through empirical estimation from genomic data or by calculation from a species tree under the multispecies coalescent model [2].

Internal Branch Identification: For each gene tree, identify all internal branches and their lengths. Internal branches represent shared evolutionary history that generates trait covariances between species [2].

Frequency Weighting: Weight each gene tree's internal branches by its observed or expected frequency in the dataset. Under the multispecies coalescent, expected frequencies can be calculated from the species tree in coalescent units [2].

Matrix Construction: Calculate the updated C* matrix by summing the internal branches across all gene trees, weighted by their frequencies. Each off-diagonal entry in the matrix represents the expected covariance between a pair of species based on their shared history across all gene trees [2].

Comparative Analysis: Use the completed C* matrix in place of the standard phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix in existing comparative method software packages for tasks such as phylogenetic regression, rate estimation, or ancestral state reconstruction [2].

The R package seastaR implements this protocol, providing functions to construct C* from either empirical gene trees or a species tree alone [2]. This approach assumes that each gene tree contributes equally to trait variation and that loci affecting traits follow the same distribution of topologies as the genome overall [2].

Protocol 2: Multi-Tree Pruning Algorithm Approach

The multi-tree pruning approach applies Felsenstein's pruning algorithm across a set of gene trees to calculate the likelihood of observed trait data given the complete phylogenomic history [2].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Gene Tree Preparation: Compile a representative set of gene trees that capture the distribution of topologies and branch lengths present in the genomic data.

Trait Model Specification: Define an evolutionary model for trait change (e.g., Brownian motion, Ornstein-Uhlenbeck) with initial parameter estimates.

Likelihood Calculation per Tree: For each gene tree, calculate the likelihood of the observed trait data using the pruning algorithm, which efficiently computes the probability of the data by traversing the tree from tips to root [2].

Likelihood Integration: Combine likelihoods across all gene trees, weighting by their frequencies, to obtain the overall likelihood of the trait data given the complete phylogenomic dataset.

Parameter Estimation: Optimize model parameters by maximizing the combined likelihood across the set of gene trees.

This approach, while computationally intensive, enables more sophisticated comparative inferences including ancestral state reconstruction and identification of lineage-specific rate shifts in the presence of discordance [2]. Though currently limited to smaller numbers of species, it represents a powerful approach for detailed analysis of trait evolution.

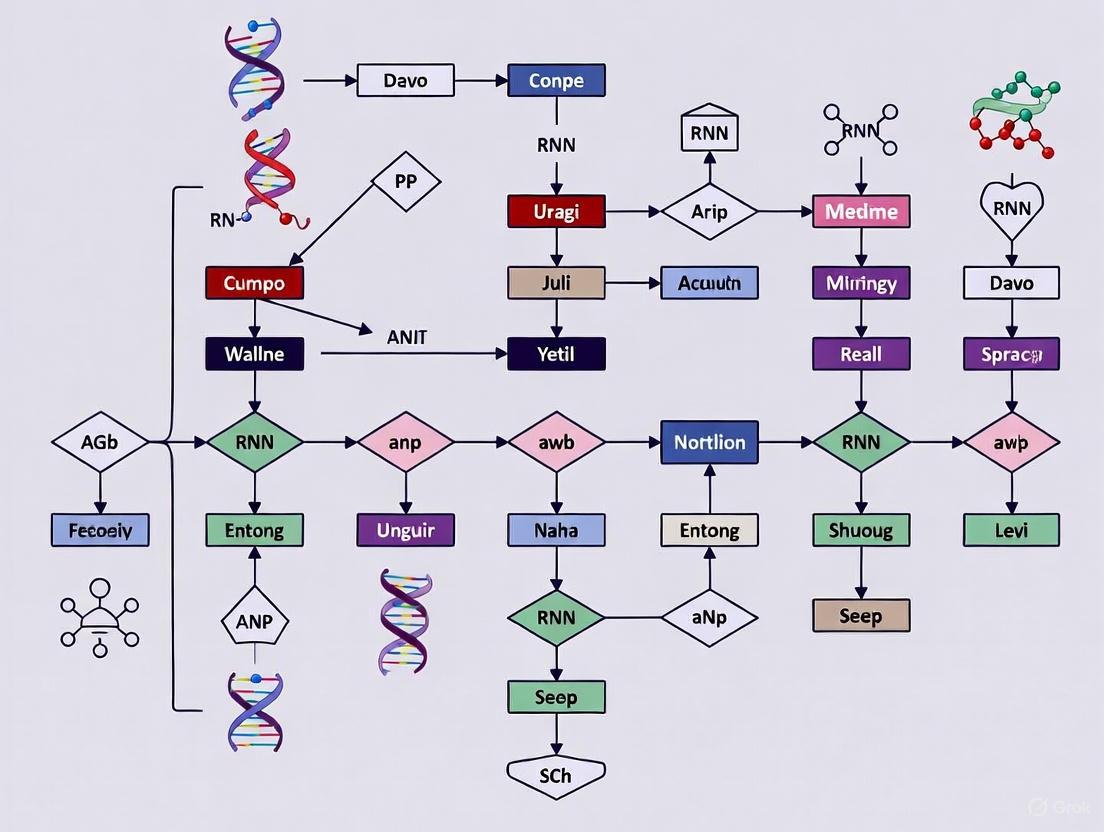

Workflow Visualization

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Phylogenomic Comparative Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Software | seastaR R package | Constructs updated variance-covariance matrices incorporating gene tree discordance [2] |

| Tree Databases | TreeHub database | Provides 135,502 phylogenetic trees from 7,879 studies for comparative analysis [7] |

| Genomic Data Sources | Dryad, FigShare | Open-access repositories for phylogenomic datasets and associated trait data [7] |

| Methodological Guides | ConGen Courses | Intensive training in conservation genomics and phylogenomic analysis [8] |

| Funding Resources | NSF Systematics and Biodiversity Science Cluster | Supports research advancing understanding of organismal diversity and evolutionary history [3] |

| Taxonomic Reference | NCBI Taxonomy Database | Provides standardized taxonomic names for integrating species information across studies [7] |

The seastaR R package represents a specialized tool developed specifically for phylogenomic comparative methods, enabling researchers to construct the updated C* matrix that accounts for gene tree discordance [2]. This package offers two approaches: the trees_to_vcv function constructs the matrix from a list of gene trees with branch lengths and their observed frequencies, while get_full_matrix calculates expected internal branches and frequencies directly from a species tree in coalescent units using multispecies coalescent theory [2].

The recently developed TreeHub database addresses a critical need in the field by providing comprehensive access to phylogenetic trees extracted from scientific publications [7]. This resource includes 135,502 phylogenetic trees from 7,879 research articles across 609 academic journals, spanning diverse taxa including archaea, bacteria, fungi, viruses, animals, and plants [7]. Each tree in TreeHub is associated with rich metadata, including taxonomic information derived from both publication text and terminal node labels, facilitating efficient retrieval of phylogenies relevant to specific research questions [7].

For researchers designing phylogenomic studies, conservation genomics courses such as ConGen provide essential training in both theoretical foundations and practical analytical skills [8]. These intensive programs cover topics ranging from study design and genome sequencing to population genomic analysis and phylogenomic inference, preparing researchers to effectively implement the protocols described herein [8].

Interpretation Guidelines for Phylogenomic Networks

When phylogenomic analyses reveal evidence of reticulate evolution, proper interpretation of phylogenetic networks becomes essential. In these networks, reticulation vertices represent hybridization events, with two incoming branches (parental lineages) and one outgoing branch (hybrid descendant) [6]. The inheritance probability (γ) parameter denotes the proportion of genetic material that the hybrid lineage inherits from each parent, with values near 0.5 indicating symmetrical hybridization and values approaching 0 or 1 suggesting asymmetrical introgression [6].

It is crucial to recognize that γ values near 0.5 do not necessarily indicate hybrid speciation without backcrossing; alternative scenarios such as bidirectional backcrossing at equal rates can produce similar patterns [6]. Similarly, distinguishing between recent and ancient hybridization events based solely on γ values is challenging and may involve subjectivity [6]. Researchers should supplement network analyses with additional biological evidence, such as reproductive isolation mechanisms or genomic evidence from high-quality assemblies, to draw robust conclusions about evolutionary history [6].

Phylogenomic networks provide powerful insights for biodiversity conservation by identifying historically isolated lineages versus those connected by gene flow, informing decisions about population management and conservation unit delineation [6] [4]. As these methods continue to develop, they offer increasingly sophisticated approaches for understanding the complex evolutionary histories that shape biological diversity.

How PCMs Differ from Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction

In the field of evolutionary biology, the distinction between phylogenetic tree reconstruction and phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) is foundational yet often misunderstood. Phylogenetic tree reconstruction aims to infer the evolutionary relationships among species or genes, producing the branching diagram that represents their historical descent [9]. In contrast, PCMs are statistical techniques that use these phylogenetic trees as a framework to test evolutionary hypotheses, analyze trait evolution, and correct for phylogenetic non-independence among species [1]. Within biodiversity research, understanding this distinction is crucial for designing robust studies and accurately interpreting evolutionary patterns.

This article provides a clear methodological separation between these two domains, offering practical protocols and tools that empower researchers to apply both approaches effectively in phylogenomic studies.

Core Conceptual Distinctions

Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction: Building the Evolutionary Framework

Phylogenetic tree construction is the process of inferring evolutionary relationships from molecular or morphological data [9]. The general workflow begins with sequence collection, proceeds through multiple sequence alignment and model selection, and culminates in tree inference [9]. This process produces the essential phylogenetic tree that serves as a scaffold for all subsequent comparative analyses.

Several principal algorithms are used for tree reconstruction, each with different theoretical foundations and applications [9]:

- Distance-based methods (e.g., Neighbor-Joining): These methods convert sequence data into a distance matrix and use clustering algorithms to build trees. They are computationally efficient and suitable for large datasets [9].

- Character-based methods: This category includes:

- Maximum Parsimony (MP): Seeks the tree that requires the fewest evolutionary changes [9].

- Maximum Likelihood (ML): Finds the tree that maximizes the probability of observing the data under a specific evolutionary model [9] [10].

- Bayesian Inference (BI): Uses Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to approximate the posterior probability distribution of trees [1].

Phylogenetic Comparative Methods: Analyzing Evolution on a Fixed Tree

PCMs begin where tree reconstruction ends—they operate on an already inferred phylogenetic tree to test evolutionary hypotheses [1]. These methods are essential because species share evolutionary history, making their traits non-independent data points. PCMs statistically account for this non-independence to avoid biased results [1].

Common PCMs include:

- Independent Contrasts (IC): Uses differences between sister taxa to analyze trait evolution under a Brownian motion model [1].

- Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS): Extends traditional regression to account for phylogenetic relationships [1].

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Estimates trait values for ancestral nodes in the tree.

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental relationship between these two processes and their distinct roles in evolutionary analysis.

Methodological Comparison

The table below summarizes the key differences in objectives, inputs, outputs, and applications between tree reconstruction and PCMs.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction and Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Aspect | Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction | Phylogenetic Comparative Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Infer evolutionary relationships and branching patterns [9] | Test evolutionary hypotheses using established relationships [1] |

| Primary Input | Molecular sequences (DNA, RNA, amino acids) [9] | Phylogenetic tree + trait data [1] |

| Core Methods | Distance-based (NJ), Maximum Parsimony, Maximum Likelihood, Bayesian Inference [9] | Independent Contrasts, PGLS, ancestral state reconstruction [1] |

| Key Output | Phylogenetic tree topology with branch lengths [9] | Statistical inferences about evolutionary processes [1] |

| Model Dependencies | Sequence evolution models (e.g., JC69, HKY85) [9] | Trait evolution models (e.g., Brownian motion, Ornstein-Uhlenbeck) [1] |

| Primary Application | Establish phylogenetic relationships for taxonomic groups [9] | Understand adaptation, trait correlations, and evolutionary rates [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Maximum Likelihood Tree Reconstruction

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a phylogenetic tree using the Maximum Likelihood approach, which is widely used in modern phylogenomic studies [9] [10].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for Maximum Likelihood Phylogenetic Reconstruction

| Reagent/Software | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Data | Raw molecular data for analysis | DNA, RNA, or amino acid sequences in FASTA format [9] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool (e.g., MUSCLE) | Align homologous sequences for comparison [10] | Essential for identifying evolutionarily corresponding positions [9] |

| Model Testing Software (e.g., ModelTest-NG) | Select best-fit nucleotide/amino acid substitution model [9] | Critical for ML accuracy; uses AIC/BIC criteria [9] |

| ML Tree Inference Program (e.g., RAxML, IQ-TREE) | Implement ML algorithm to find optimal tree [9] | Uses heuristic searches for computational efficiency [9] |

| Branch Support Assessment | Evaluate statistical confidence in tree nodes | Typically 100-1000 bootstrap replicates [9] |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sequence Collection and Alignment: Collect homologous sequences from public databases (e.g., GenBank, EMBL) or experimental data. Perform multiple sequence alignment using tools such as MUSCLE [10] or Clustal. Visually inspect and refine alignments to remove poorly aligned regions.

Evolutionary Model Selection: Use model selection software to identify the best-fit substitution model based on information criteria (AIC/BIC). The model describes the relative rates of substitution between character states [9].

Tree Inference: Execute ML analysis using the selected model. The algorithm will search tree space to find the topology with the highest likelihood of producing the observed data [9] [10]. Use heuristic search strategies for larger datasets.

Branch Support Assessment: Perform bootstrap analysis (typically 100-1000 replicates) to assess statistical confidence in tree nodes. Bootstrap values >70% are generally considered well-supported [9].

Tree Visualization and Storage: Visualize the final tree using appropriate software (e.g., FigTree, iTOL). Save the tree in Newick format, which uses parentheses and commas to represent tree topology with branch lengths [11].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this protocol:

Protocol 2: Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) Analysis

PGLS is a fundamental PCM that tests for correlations between traits while accounting for phylogenetic non-independence [1]. This protocol begins with a constructed phylogenetic tree.

Table 3: Essential Components for PGLS Analysis

| Component | Role in Analysis | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Tree | Evolutionary framework for analysis | Must include branch lengths; often in Newick format [11] |

| Trait Dataset | Phenotypic or ecological measurements | Continuous traits; requires normal distribution or appropriate transformation |

| Covariance Matrix | Quantifies phylogenetic structure | Derived from the phylogenetic tree and evolutionary model [1] |

| Evolutionary Model | Specifies trait evolution process | Brownian motion is default; consider Ornstein-Uhlenbeck for constrained evolution [1] |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R) | Implement PGLS algorithm | Packages: ape, nlme, caper [1] |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation: Compile trait data for the species in your phylogenetic tree. Ensure the trait data and tree tip labels match exactly. Log-transform continuous data if necessary to meet normality assumptions.

Phylogenetic Covariance Matrix Construction: Calculate a variance-covariance matrix from the phylogenetic tree, which represents the expected covariance between species due to shared evolutionary history under a specified model (e.g., Brownian motion).

Model Specification: Define the PGLS model structure using the formula:

trait1 ~ trait2 + ...with the phylogenetic covariance matrix incorporated as a correlation structure.Model Fitting: Execute the PGLS analysis using appropriate statistical software. The method will simultaneously estimate the regression parameters and phylogenetic signal.

Result Interpretation: Evaluate the significance of relationships using phylogenetic corrected p-values. Interpret effect sizes in an evolutionary context, considering the biological implications of any detected relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenomic Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| IQ-TREE | Tree Reconstruction | Efficient maximum likelihood tree inference [9] | Large-scale phylogenomic analyses with model selection |

| BEAST2 | Tree Reconstruction | Bayesian evolutionary analysis with time calibration [1] | Dated phylogenies; population dynamics |

| RAxML | Tree Reconstruction | Rapid ML-based tree inference [9] | Large-scale phylogenomic analyses |

| R (ape, phytools, nlme packages) | PCM Analysis | Implementation of various comparative methods [1] | PGLS, ancestral state reconstruction, phylogenetic signal testing |

| Newick Format | Data Standard | Tree representation with parentheses and commas [11] | Universal format for storing and exchanging tree data |

| gitana | Visualization | Automated production of publication-ready tree figures [12] | Standardizing tree visualization and nomenclature formatting |

| TOP/FMTS | Tree Comparison | Compare tree topologies using Boot-Split Distance [13] | Assessing congruence between gene trees |

Advanced Considerations in Phylogenomic Analysis

Dealing with Incongruence: The Forest of Life

Modern phylogenomics has revealed that different genes often tell different evolutionary stories, creating a "Forest of Life" rather than a single Tree of Life [13]. This incongruence arises from biological processes like horizontal gene transfer (especially in prokaryotes), incomplete lineage sorting, and hybridization, as well as analytical artifacts [13].

Methods like the Boot-Split Distance (BSD) have been developed to compare multiple phylogenetic trees while accounting for bootstrap support, helping researchers identify robust phylogenetic signals amidst conflicting topologies [13]. This approach weights tree splits according to their bootstrap values, providing a more nuanced comparison than methods considering all branches as equal [13].

Methodological Pitfalls and Validation

Comparative methods require careful implementation and validation. For example, the Independent Evolution (IE) method was promoted as a novel PCM but was subsequently shown through simulations to produce severely biased estimates of ancestral states and branch-specific changes [14]. This highlights the importance of rigorous methodological validation through simulation studies before adopting new comparative approaches.

Researchers should incorporate uncertainty in phylogenetic comparative analyses using Bayesian methods or bootstrap resampling [1]. The mathematical framework for incorporating phylogenetic uncertainty in Bayesian methods can be represented as:

[ P(\theta | D) = \int P(\theta | G) P(G | D) dG ]

where (\theta) represents the parameters of interest, (D) is the trait data, and (G) is the phylogenetic tree [1].

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction and phylogenetic comparative methods represent distinct but interconnected phases in evolutionary analysis. Tree reconstruction builds the evolutionary scaffold from molecular data, while PCMs use this scaffold to test hypotheses about evolutionary processes and trait relationships. Understanding this distinction—and the appropriate application of each approach—is fundamental to robust phylogenomic research in biodiversity studies. As the field advances with increasingly large genomic datasets, this methodological clarity becomes ever more critical for generating reliable insights into evolutionary patterns and processes.

Phylogenetic Diversity, Signal, and Evolutionary Models

Phylogenetic diversity (PD) and phylogenetic signal are foundational concepts in modern evolution and biodiversity research. PD quantifies the evolutionary history represented by a set of species, often calculated as the sum of branch lengths connecting them on a phylogenetic tree [15]. This approach recognizes that not all species contribute equally to biodiversity; some represent unique evolutionary lineages with distinct feature diversity that should be prioritized in conservation planning [15] [16]. Phylogenetic signal describes the statistical tendency for related species to resemble each other more than distant relatives due to shared evolutionary history, serving as a crucial bridge between evolutionary patterns and ecological processes [17].

The quantitative framework for analyzing these concepts has expanded dramatically, with at least 70 phylogenetic metrics now available, creating what has been termed a "jungle of indices" [16]. These metrics can be organized into three mathematical dimensions: richness (sum of accumulated phylogenetic differences), divergence (mean phylogenetic relatedness), and regularity (variance in phylogenetic differences) [16]. Proper selection and application of these metrics requires connecting research questions with the appropriate dimension while avoiding arbitrary assumptions about the relationship between phylogenetic pattern and underlying feature diversity [15].

Table 1: Key Dimensions of Phylogenetic Diversity Metrics

| Dimension | Conceptual Meaning | Anchor Metrics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Sum of accumulated phylogenetic differences | PD (Faith's phylogenetic diversity) | Conservation prioritization, feature diversity estimation |

| Divergence | Mean phylogenetic relatedness among taxa | MPD (mean pairwise distance) | Community assembly inference, biogeographic patterns |

| Regularity | Variance in phylogenetic differences | VPD (variation of pairwise distances) | Evolutionary radiation analysis, trait evolution studies |

Quantitative Framework and Metrics

Core Phylogenetic Diversity Metrics

The most established PD metric is Faith's PD, which calculates the sum of the branch lengths of the phylogenetic tree connecting all species in an assemblage [16]. This richness-based metric has become particularly valuable in conservation biology for prioritizing species that maximize feature diversity [16]. Complementary divergence metrics include MPD (mean pairwise distance), which measures the average phylogenetic distance between all pairs of species in an assemblage, and MNTD (mean nearest taxon distance), which calculates the average distance between each species and its closest relative in the assemblage [16].

For quantifying phylogenetic signal, the Kmult statistic measures the ratio of observed to expected phenotypic variation when accounting for phylogenetic nonindependence versus ignoring it, with an expected value of Kmult = 1 under a Brownian motion model of evolution [17]. This approach has been successfully applied to diverse morphological systems, including recent studies of delphinid vertebral columns where it helped disentangle ecological adaptation from phylogenetic constraints [17].

Mathematical Comparisons and Selection Guidelines

Recent mathematical analyses have quantified the differences between phylogenetic diversity indices, particularly comparing Fair Proportion and Equal Splits indices [18]. These analyses determine the maximum value of the difference between phylogenetic diversity of an assemblage and the sum of diversity indices of individual species under various phylogenetic tree constraints [18]. This work highlights that metric choice requires careful consideration of both mathematical properties and biological questions.

Table 2: Applications of Phylogenetic Metrics Across Ecological Sub-disciplines

| Sub-discipline | Primary Questions | Recommended Metrics | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservation Biology | Which species maximize preserved evolutionary history? | PD, ED (Evolutionary Distinctiveness) | Feature diversity, option value, complementarity |

| Community Ecology | Are co-occurring species more related than expected by chance? | MPD, MNTD, NRI, NTI | Ecological assembly rules, environmental filtering |

| Macroecology | How do evolutionary processes shape large-scale diversity patterns? | PD, MPD, VPD | Spatial scaling, evolutionary rates, diversification patterns |

| Comparative Biology | How conserved are traits across phylogeny? | Kmult, Blomberg's K, λ | Evolutionary models, trait lability, adaptation rates |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Assessing Phylogenetic Signal in Morphological Traits

This protocol outlines the assessment of phylogenetic signals in morphological datasets, based on methods successfully applied in studying delphinid vertebral evolution [17].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software Environment: R statistical platform with Geomorph package (v4.0.8) for geometric morphometrics and phylogenetic comparative analyses [17]

- Phylogenetic Tree: Time-calibrated molecular phylogeny relevant to the study group (e.g., from previous phylogenomic studies) [17]

- Morphometric Data: Three-dimensional landmark configurations digitized from morphological specimens [17]

- Alignment Tools: MAFFT v7.503 or similar for sequence alignment in molecular phylogeny construction [19]

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: IQ-TREE 3 for maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis [19]

Procedure:

- Data Collection: For each specimen, digitize three-dimensional landmarks representing the morphological structures of interest. For vertebral studies, typical configurations include 28-41 landmarks and semilandmarks across different vertebral regions [17].

- Procrustes Superimposition: Perform generalized least-squares Procrustes analysis (GPA) to remove non-shape variation using the

gpagenfunction in the Geomorph package. This procedure computes centroid size as a size variable and produces aligned shape coordinates for subsequent analysis [17]. - Phylogenetic Signal Testing: Apply the

physignal.zfunction in Geomorph with RRPP v2.0.3 to compute effect and p-values for the Kmult statistic. This test measures phylogenetic signal as the ratio of observed to expected phenotypic variation under Brownian motion evolution [17]. - Phylogenetic Ordination: Perform three complementary ordination analyses to visualize shape-space patterns and evolutionary trends:

- Angle Testing: Assess similarity in direction of the first component across PA, PhyPCA, and PACA using the

angleTestin the MORPHO package to evaluate orientation similarity between different ordination approaches [17].

Protocol: Quantifying Temporal Phylogenetic Diversity in Pathogens

This protocol describes methods for analyzing temporal dynamics of phylogenetic diversity, as applied in SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance studies [19].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Genomic Database: GISAID database for accessing complete genome sequences and associated metadata [19]

- Alignment Software: MAFFT v7.503 for multiple sequence alignment [19]

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: IQ-TREE 3 for maximum likelihood tree building [19]

- Diversity Calculation: Custom R or Python scripts for calculating MedPD (median pairwise distance) and PVR (phylogenetic eigenvector regression) [19]

Procedure:

- Data Retrieval and Filtering: Download complete genome sequences and metadata from GISAID. Apply filtering criteria: include only complete genomes (>29,000 nucleotides for SARS-CoV-2), exclude low-coverage entries (>5% undefined bases), and retain only entries with complete collection dates [19].

- Sequence Alignment: Perform multiple sequence alignment using MAFFT v7.503. Manually curate the resulting alignment to identify and address misaligned regions or problematic sequences [19].

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Construct maximum likelihood phylogenies using IQ-TREE 3 with appropriate substitution models selected through model testing [19].

- Pairwise Distance Calculation: Compute pairwise phylogenetic distances between all sequences for each time period of interest.

- Phylogenetic Diversity Metrics: Calculate MedPD (median pairwise distance) as a robust measure of phylogenetic diversity within time windows. Perform PVR (phylogenetic eigenvector regression) derived from principal coordinate analysis of pairwise distances to identify major axes of phylogenetic variation [19].

- Temporal Analysis: Track changes in phylogenetic diversity metrics across sampling periods, identifying peaks associated with emergence of novel variants and correlating with epidemiological parameters [19].

Analytical Framework and Evolutionary Models

Resolving Phylogenetic Trees and Accounting for Uncertainty

A critical consideration in phylogenetic diversity analyses is phylogenetic resolution. Studies have demonstrated that measures of community phylogenetic diversity and dispersion are generally more sensitive to loss of resolution basally in the phylogeny and less sensitive to loss of resolution terminally [20]. The loss of phylogenetic resolution generally causes false negative results rather than false positives, potentially causing researchers to miss significant patterns [20]. This has important implications for the growing field of phylogenomics, where incomplete lineage sorting can create challenging polytomies, particularly in rapid radiations like birds and dolphins [21] [17].

In dolphin vertebrates, for example, phylogenetic signal varies dramatically across different vertebral regions. The anterior thorax, posterior thorax, and synclinal point show low phylogenetic signals with diversification associated primarily with size and habitat, while the mid-torso and tail stock retain strong phylogenetic signals, reflecting subfamily level conservatism [17]. This regional variation highlights the modularity of evolutionary influences across anatomical structures.

Integrating Eco-Evolutionary Processes into Biodiversity Models

Modern biodiversity modeling seeks to integrate multiple eco-evolutionary processes including species' physiology, dispersal capabilities, biotic interactions, and evolutionary adaptation [22]. These processes interact in complex ways that create non-trivial effects on species range dynamics and community patterns [22].

Key interplays include:

- Dispersal and Biotic Interactions: Density-dependent dispersal and enemy-victim interactions can dramatically affect migration rates during climate change [22]

- Abiotic Environment and Biotic Interactions: The structure of interaction networks varies spatially and with environmental conditions, as conceptualized in the stress-gradient hypothesis [22]

- Evolutionary Adaptation and Range Limits: Evolutionary processes shape species' physiology, dispersal characteristics, and biotic interactions, thereby influencing geographic range dynamics [22]

Applications in Biodiversity Research

Case Study: Avian Phylogenomics and Adaptive Radiation

Birds represent a compelling case study in phylogenetic diversity analysis, with neoavian species accounting for over 95% of modern avian diversity emerging from an explosive radiation event near the Cretaceous–Palaeogene boundary [21]. Phylogenomic studies using whole-genome data have revealed that the rapid adaptive radiation of birds was influenced by multiple factors including global forest collapse at the end-Cretaceous mass extinction, which created ecological opportunities for diversification [21].

The incomplete lineage sorting across the ancient adaptive radiation of neoavian birds has created significant challenges for resolving the avian tree of life, described as a "hard polytomy at the root of Neoaves" [21]. This demonstrates how phylogenetic diversity analyses must account for fundamental uncertainties in tree topology, particularly for rapidly diversifying clades.

Case Study: SARS-CoV-2 Evolutionary Dynamics

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided unprecedented opportunities for analyzing phylogenetic diversity dynamics in real-time. Studies of SARS-CoV-2 in Central Brazil revealed distinct peaks in phylogenetic diversity associated with the emergence of Gamma and Omicron variants, demonstrating how temporal phylogenetic diversity metrics can track evolutionary shifts among variants of concern [19].

The strong phylogenetic signal over time, reflected in the first PCoA axis of pairwise distances, highlighted the evolutionary trajectory of the virus and mirrored epidemiological characterization of the epidemic over time [19]. This application demonstrates the public health relevance of phylogenetic diversity analyses for understanding viral diversification and informing surveillance strategies.

The integration of phylogenetic diversity, phylogenetic signal, and evolutionary models provides a powerful framework for biodiversity research across scales from conservation planning to pandemic surveillance. The growing availability of phylogenomic data has revolutionized our ability to quantify and interpret these patterns, while also revealing new complexities such as the prevalence of hybridization, cryptic species, and microbiomes that influence evolutionary trajectories [23].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on integrating multiple processes into biodiversity models, accounting for the complex interplay between physiology, dispersal, biotic interactions, and evolutionary adaptation [22]. Additionally, the challenge of metric selection from the proliferating "jungle of indices" necessitates continued development of unifying frameworks that connect research questions with appropriate analytical approaches [16]. As phylogenetic comparative methods continue to evolve, they promise to provide increasingly sophisticated insights into the eco-evolutionary dynamics of species and communities under changing environments.

The Critical Importance of Accounting for Phylogenetic Non-Independence

Phylogenetic non-independence refers to the fundamental statistical challenge that arises from the shared evolutionary history of species. Closely related species tend to resemble each other more than distantly related species due to their common ancestry, violating the key assumption of data independence in traditional statistical analyses [24]. This phenomenon, known as phylogenetic signal, represents the tendency for traits to be similar among related species and must be properly accounted for to avoid biased or incorrect conclusions in comparative biological studies [25] [24].

The critical importance of addressing phylogenetic non-independence extends across multiple biological disciplines, from evolutionary ecology and conservation biology to genomics and drug discovery. In biodiversity research, failing to incorporate phylogenetic relationships can lead to spurious correlations between traits, incorrect estimations of evolutionary rates, and flawed predictions about species responses to environmental change [26] [25]. As phylogenomic datasets continue to expand, proper accounting for these evolutionary relationships has become increasingly essential for robust biological inference [26] [21].

Theoretical Foundations and Statistical Framework

The Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) Approach

Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) represents the cornerstone methodological framework for addressing phylogenetic non-independence in comparative studies. PGLS extends traditional generalized least squares regression by incorporating a phylogenetic covariance matrix that explicitly models the expected covariance between species based on their phylogenetic relationships [24]. This matrix quantifies how much the data points are expected to deviate from independence due to shared evolutionary history.

The PGLS framework operates on several key assumptions that researchers must verify: the phylogenetic tree must be accurate and well-resolved, trait data should approximate a normal distribution, and the evolutionary model must be correctly specified for the traits and phylogeny under investigation [24]. The method estimates Pagel's λ, a parameter that measures the strength of phylogenetic signal in the residual variation of traits, with λ = 0 indicating no phylogenetic signal (independent evolution) and λ = 1 suggesting strong signal consistent with a Brownian motion model of evolution [25] [24].

Comparative Performance of Statistical Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Statistical Methods for Handling Phylogenetic Non-Independence

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Regression | Assumes data independence | Simple implementation; Computationally efficient | Produces biased p-values and effect sizes | Non-phylogenetic data; Single-species studies |

| PGLS | Incorporates phylogenetic covariance matrix | Accounts for phylogenetic signal; Flexible evolutionary models | Requires accurate phylogeny; Sensitive to model misspecification | Continuous trait evolution; Multi-species comparisons |

| Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts (PIC) | Calculates independent contrasts at nodes | Standardized contrasts; Handles speciose phylogenies | Assumes Brownian motion; Limited to single traits | Testing evolutionary correlations; Adaptive radiation studies |

| Phylogenetic Mixed Models | Partitions variance into phylogenetic and specific components | Handles complex random effects; Flexible for various data types | Computationally intensive; Complex implementation | Multi-level data; Heritability estimation |

Application Notes for Biodiversity Research

Protocol 1: Phylogenetic Diversity Assessment in Conservation Planning

Objective: To identify geographical areas with the greatest representation of evolutionary history for conservation prioritization.

Methodology:

- Phylogeny Compilation: Assemble a time-calibrated phylogeny for the target taxonomic group using genomic, transcriptomic, or mitogenomic data [27] [28].

- Spatial Data Integration: Overlay species distribution data with phylogenetic relationships using GIS platforms.

- Diversity Metrics Calculation:

- Calculate Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) as the sum of branch lengths for all species present in a site

- Compute Phylogenetic Endemism (PE) to identify areas with spatially restricted phylogenetic diversity

- Significance Testing: Use randomization procedures to identify significant centers of phylogenetic diversity and endemism [28].

Application Context: This approach was successfully applied across multiple taxonomic groups (plant genera, fish, tree frogs, acacias, and eucalypts) in the Murray-Darling basin region of southeastern Australia, revealing taxon-specific patterns of evolutionary significance and informing regional conservation strategies [28].

Protocol 2: Phylogenetically-Corrected Extinction Risk Assessment

Objective: To identify biological traits and external factors associated with extinction risk while accounting for phylogenetic and spatial non-independence.

Methodology:

- Data Collection:

- Compile threat status (e.g., IUCN categories) and geographic range size for each species

- Assemble biological trait data (e.g., seed number, adult height, flowering period, fire response)

- Obtain environmental variables (e.g., habitat loss, climate data) across species distributions [25]

- Variance Partitioning:

- Implement the Freckleton & Jetz model to partition variance into phylogenetic (λ'), spatial (ϕ), and independent (γ) components

- Use the formula: V(ϕ,λ) = γh + λ'Σ + ϕW, where Σ is the phylogenetic variance-covariance matrix and W is the spatial variance-covariance matrix [25]

- Model Fitting:

- Fit models using maximum likelihood estimation with phylogenetic and spatial matrices

- Simplify full models to minimum adequate models retaining only significant predictors

Application Context: This protocol was applied to the plant genus Banksia in Australia's Southwest Botanical Province, revealing that extinction risk was primarily associated with biological traits (brief flowering period) and human impact indicators (habitat loss) rather than phylogenetic relatedness or geographic proximity [25].

Protocol 3: Large-Scale Biodiversity Inventory Using Phylogenomics

Objective: To accelerate inventorying of hyperdiverse tropical groups during the current biodiversity crisis by integrating phylogenomic and mitochondrial data.

Methodology:

- Field Sampling: Conduct systematic sampling across the target group's geographic range (~700 localities for comprehensive coverage) [27]

- Multi-Scale Molecular Data Generation:

- Sequence transcriptomes or use anchored hybrid capture for ~40 terminals to build a robust phylogenetic backbone

- Generate mtDNA data (COI, 16S, rrnL) for thousands of specimens to delimit species and assess diversity

- Integrative Data Analysis:

- Use phylogenomics to define natural genus-group units and resolve deep relationships

- Apply species delimitation approaches (e.g., 5% uncorrected pairwise threshold) to estimate species diversity

- Map spatial structure of diversity and identify biodiversity hotspots [27]

Application Context: This workflow was implemented for Metriorrhynchini beetles, processing ~6,500 terminals and revealing ~1,850 putative species, approximately 1,000 previously unknown to science, while identifying a biodiversity hotspot in New Guinea [27].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for Phylogenetic Comparative Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function/Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Reconstruction | anchored hybrid capture | Provides phylogenomic data for resolving deep relationships | Ideal for non-model organisms; requires tissue samples [27] |

| transcriptome sequencing | Generates data for phylogenetic backbone construction | Requires fresh or preserved tissue; computationally intensive [27] | |

| mitogenomic markers (COI, 16S) | Facilitates species-level delimitation and population genetics | Cost-effective for large sample sizes; standardized protocols [27] | |

| Statistical Analysis | R packages (ape, regress) | Implements PGLS and variance partitioning algorithms | Open-source; strong community support [25] [24] |

| Bayesian PGLS frameworks | Handles complex models and uncertainty incorporation | Computationally intensive; flexible for diverse data types [24] | |

| Data Integration | Spatial analysis software (GIS) | Links phylogenetic diversity with geographic distributions | Essential for conservation prioritization [28] |

| Multiple imputation methods | Addresses missing data in comparative analyses | Reduces bias from incomplete trait data [24] |

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for phylogenetic comparative analysis, illustrating key decision points and methodological pathways from research question formulation through data collection, analysis selection, and result interpretation.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Integration with Biodiversity Accounting Frameworks

The System of Environmental-Economic Accounting Experimental Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA-EEA) provides a framework for organizing biodiversity information in a spatially explicit format consistent with national statistical systems [29]. Phylogenetic data can enhance these accounts by incorporating evolutionary distinctiveness and phylogenetic diversity metrics alongside traditional species counts, offering a more comprehensive perspective on biodiversity value. The Biological Diversity Protocol (BD Protocol) further enables organizations to standardize the measurement and reporting of biodiversity impacts, creating opportunities for integrating phylogenetic information into corporate environmental accounting [30].

Emerging Opportunities in Phylogenomics

Recent advances in whole-genome sequencing and computational methods are revolutionizing phylogenetic comparative approaches. The burgeoning availability of clade-scale genomic datasets enables researchers to move beyond correlation-based inference to directly identify the functional genetic variation underlying trait evolution [26]. In avian phylogenomics, for example, analyses of over 1,500 loci have resolved previously contentious relationships within Neoaves, providing a robust framework for investigating the evolutionary drivers of avian diversification [21]. These phylogenomic scaffolds support increasingly precise investigations of how phenotypic traits and genomic characteristics co-evolve during adaptive radiations [21].

Future developments will likely focus on integrating PGLS with machine learning approaches, developing more user-friendly software implementations, and creating standardized workflows for handling the computational challenges of massive genomic datasets [24]. As these methodological innovations mature, accounting for phylogenetic non-independence will remain a critical component of rigorous biological research, enabling scientists to distinguish evolutionary signal from statistical artifact across diverse applications from conservation prioritization to pharmaceutical development.

Major Questions PCMs Can Answer in Biodiversity and Biomedical Research

Application Note: Resolving Deep Evolutionary Relationships in Adaptive Radiations

Background and Biological Question

A central challenge in evolutionary biology involves resolving the rapid diversification events that generate most of life's diversity. Phylogenomic comparative methods (PCMs) provide the statistical framework to test hypotheses about the timing, pattern, and drivers of these adaptive radiations. A critical question PCMs can address is: How do we resolve the deep evolutionary relationships and timing of diversification in major vertebrate groups like birds, and what factors drove their ecological and phenotypic diversification? This question is fundamental for understanding how biodiversity is generated and maintained over macroevolutionary timescales.

Experimental Protocol: Whole-Genome Phylogenomics for Divergence Dating and Trait Evolution

Objective: To reconstruct the avian tree of life using whole-genome data, estimate divergence times, and correlate diversification with ecological opportunities and phenotypic traits [21].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Taxon Sampling and Genome Sequencing:

- Select representative taxa across all major avian lineages, with particular focus on Neoaves which comprises over 95% of modern bird diversity [21].

- Sequence whole genomes using high-coverage, long-read technologies to maximize data completeness. The objective is hundreds of loci or entire genomes for robust analysis [21].

Data Matrix Assembly and Orthology Prediction:

- Assemble genomes and identify single-copy orthologous genes using tools like

OrthoFinderorBUSCO. - Alon nucleotide and amino acid sequences for each ortholog using multiple sequence aligners (e.g.,

MAFFT,PRANK). - Concatenate alignments into a supermatrix or use gene tree-species tree methods with data partitions.

- Assemble genomes and identify single-copy orthologous genes using tools like

Phylogenetic Inference and Divergence Time Estimation:

- Perform maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses with tools like

RAxML-NGandMrBayesto infer species trees. - Estimate divergence times using Bayesian relaxed-clock methods (e.g.,

MCMCTree,BEAST2). Calibrate the tree with multiple robust fossils (e.g., Archaeopteryx) and known geological events [21].

- Perform maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses with tools like

Trait-Diversification Correlation Analysis:

- Code ecological (e.g., diet, habitat) and phenotypic traits (e.g., body size, plumage) from literature and museum specimens.

- Use PCMs such as

BayesTraitsorphylolmin R to test for correlations between trait evolution and diversification rates, correcting for phylogenetic uncertainty.

Key Results and Interpretation

Recent phylogenomic studies have leveraged PCMs to reveal that modern birds underwent an explosive radiation near the Cretaceous–Palaeogene (K-Pg) boundary, with neoavian lineages diversifying rapidly after the mass extinction event [21]. Comparative analyses indicate that this diversification was linked to ecological opportunity and potentially influenced by the concurrent rise of flowering plants [21]. PCMs were crucial in establishing this timeline and testing the hypothesis of adaptive radiation in response to new ecological niches.

Application Note: Accelerating Biodiversity Inventory in Hyperdiverse Taxa

Background and Biological Question

The overwhelming majority of species on Earth, particularly in the tropics, remain unknown to science, creating a critical "taxonomic impediment" to conservation. How can we rapidly inventory and delimit species in hyperdiverse groups to establish a robust framework for conservation prioritization and evolutionary studies? PCMs applied to genomic data provide a powerful solution for scaling up biodiversity discovery and mapping biogeographic patterns.

Experimental Protocol: Integrative Phylogenomic and Mitochondrial Workflow for Species Delimitation

Objective: To combine phylogenomic backbone trees with dense mitochondrial DNA barcoding to delimit species, estimate diversity, and identify biodiversity hotspots in a hyperdiverse beetle tribe (Metriorrhynchini) from the tropics [27].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Field Sampling and DNA Extraction:

- Conduct systematic field sampling across the target group's geographic range (~700 localities for beetles) [27].

- Preserve specimens in >95% ethanol or RNA later for genomic analyses. Subsample for voucher specimens.

- Extract high-molecular-weight DNA for a subset of specimens for phylogenomics, and total DNA for all specimens for mtDNA sequencing.

Multi-Tiered Sequencing Strategy:

- Phylogenomic Backbone: For a subset of specimens (~50), use Anchored Hybrid Enrichment (AHE) or transcriptome sequencing to obtain hundreds to thousands of nuclear loci [27].

- Mitochondrial Screening: For all specimens (~6500 terminals), amplify and sequence standard mtDNA barcode regions (e.g., COI, 16S) using Sanger sequencing [27].

Data Analysis and Species Delimitation:

- Reconstruct a robust phylogenomic tree from the nuclear loci to define natural genus-level and higher clades.

- Map the mtDNA data onto this backbone using constrained phylogenetic analysis.

- Apply species delimitation methods (e.g.,

ABGD,mPTP) to the mtDNA data, using the phylogenomic tree to guide and validate species-level clusters. A common threshold is a 5% uncorrected pairwise genetic distance for preliminary species hypotheses [27].

Spatial Analysis of Diversity:

- Georeference all sampling localities.

- Use spatial analysis in GIS software (e.g.,

QGIS) and R packages (phyloregion,raster) to map species richness and endemism, identifying geographic hotspots.

Key Results and Interpretation

This integrative PCM-based protocol successfully identified approximately 1,850 putative species from ~6,500 beetle specimens, with an estimated 1,000 species new to science [27]. The analysis revealed a previously unrecognized biodiversity hotspot in New Guinea and showed extremely high species-level endemism [27]. This workflow provides a scalable, evidence-based scaffold for prioritizing conservation efforts in regions of highest unique diversity.

Application Note: Delineating Conservation Units for Wildlife Management

Background and Biological Question

Effective conservation requires managing populations that represent unique evolutionary lineages. The key question is: How can we diagnose evolutionarily significant populations and forecast their vulnerability to environmental change to inform targeted conservation strategies? PCMs, combined with genomic data and ecological niche modeling, allow for the identification of such conservation units and the prediction of their future trajectories.

Experimental Protocol: Genomic Delineation of Conservation Units with Niche Modeling

Objective: To use reduced-representation genomic data (ddRADseq) and niche modeling to delimit species and infraspecific conservation units in North American least shrews (Cryptotis parvus group), and to project their future vulnerability [31].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Tissue Sampling and Genotyping:

- Obtain tissue samples (e.g., ear clips, organ biopsies) from museum collections or field efforts, covering the species' geographic range.

- Perform double-digest Restriction-site Associated DNA sequencing (ddRADseq) to generate genome-wide SNP data for population-level analysis.

Population Genomic Analysis:

- Process raw sequences using a pipeline like

STACKSoripyradfor SNP calling. - Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and ADMIXTURE analysis to visualize genetic clustering.

- Construct a coalescent-based species tree using

SNAPPorASTRALto resolve species relationships. - Calculate population genetic statistics (e.g., F~ST~, nucleotide diversity) and test for mito-nuclear discordance.

- Process raw sequences using a pipeline like

Ecological Niche Modeling:

- Compile georeferenced occurrence records for the target species and related lineages.

- Obtain current and future bioclimatic data from WorldClim or CHELSA.

- Use MaxEnt or a similar platform to model the current ecological niche. "Hindcast" the model to past climate conditions (e.g., Last Glacial Maximum) to infer historical range shifts.

- "Forecast" the model under future climate scenarios to predict range contractions or expansions.

Conservation Unit Designation:

- Synthesize genomic and niche modeling results to define Evolutionarily Significant Units (ESUs) and Management Units (MUs) based on neutral and adaptive divergence [31].

Key Results and Interpretation

The application of PCMs to the shrew system revealed that the westernmost peripheral populations constitute an evolutionarily distinct unit based on nuclear genomic data, consistent with a relict conservation unit [31]. The study also found mito-nuclear discordance, suggesting past hybridization or mitochondrial capture [31]. Niche modeling predicted continued future loss of suitable habitat for these peripheral populations, highlighting their vulnerability and the urgent need for targeted monitoring and conservation [31].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Phylogenomic Analysis for Adaptive Radiations

Title: Phylogenomic workflow for evolutionary radiations.

Integrative Biodiversity Inventory

Title: Workflow for biodiversity inventory.

Conservation Unit Delineation

Title: Workflow for conservation genomics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key research reagents, materials, and analytical tools for phylogenomic comparative methods.

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application | Example Use Case(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anchored Hybrid Enrichment (AHE) Probes | Molecular Biology Reagent | Hybridization-based capture of hundreds to thousands of conserved nuclear loci from across the genome. | Resolving deep evolutionary relationships in adaptive radiations of birds [21] and beetles [27]. |

| ddRADseq Kit | Molecular Biology Kit | Double-digest Restriction-site Associated DNA sequencing for cost-effective, genome-wide SNP discovery. | Delineating infraspecific conservation units and population structure in least shrews [31]. |

| Orthologous Gene Sets (e.g., BUSCO) | Bioinformatic Resource | Benchmark0 universal single-copy orthologs to assess data completeness and for phylogenomic matrix construction. | Data quality control and orthology prediction in avian phylogenomics [21]. |

| RAxML-NG / IQ-TREE | Software Tool | Fast and scalable maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference from molecular sequence data. | Building the species tree from large concatenated alignments of genomic data [21] [27]. |

| BEAST2 | Software Tool | Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees, used for divergence time estimation and phylodynamics. | Dating the radiation of neoavian birds after the K-Pg boundary [21]. |

Phylogenetic Comparative Methods (PCM) R packages (e.g., phylolm, geiger) |

Software Library | Statistical framework in R for analyzing trait evolution and correlations while accounting for phylogeny. | Testing for correlations between ecological traits and diversification rates [21]. |

Species Delimitation Software (e.g., mPTP, ABGD) |

Software Tool | Objective, data-driven methods for clustering individuals into putative species using genetic data. | Accelerating species discovery in hyperdiverse tropical beetle assemblages [27]. |

| MaxEnt | Software Tool | Algorithm for modeling species' ecological niches and geographic distributions from occurrence data. | Forecasting future habitat suitability for peripheral populations of least shrews [31]. |

Tools and Techniques: Implementing Phylogenomic Analyses in Practice

In the face of global biodiversity decline, phylogenomic comparative methods have become essential tools for quantifying evolutionary relationships and prioritizing conservation efforts. Moving beyond traditional species richness metrics, these approaches integrate evolutionary history, functional traits, and spatial distribution to provide a more comprehensive understanding of biodiversity patterns. This application note details three key software solutions—BioDT, PhyloNext, and the BAT R package—that enable researchers to implement these advanced methodologies. We provide a comparative analysis of their capabilities, detailed experimental protocols for phylogenetic diversity analysis, and visual workflows to guide users in selecting and implementing the appropriate tools for their biodiversity research needs.

BioDT (Biodiversity Digital Twin) represents an advanced modeling framework designed to calculate and visualize biodiversity metrics from dynamic global data sources. As a prototype digital twin, it provides sophisticated simulation capabilities for understanding and predicting biodiversity dynamics, leveraging the PhyloNext pipeline for core computational workflows [32]. PhyloNext is a flexible, data-intensive computational pipeline specifically designed for phylogenetic diversity and endemicity analysis, integrating GBIF occurrence data with Open Tree of Life phylogenies through the Biodiverse software [33] [34]. The BAT R package provides comprehensive tools for assessing alpha and beta diversity across all dimensions (taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional), implementing algorithms for biodiversity analysis based on species identities/abundances, phylogenetic/functional distances, trees, and hypervolumes [35].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biodiversity Software Tools

| Feature | BioDT | PhyloNext | BAT R Package |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Digital twin for biodiversity simulation & prediction | Pipeline for phylogenetic diversity analysis | Biodiversity assessment tools for R |

| Core Methodology | PhyloNext pipeline integration | GBIF + OpenTree integration via Biodiverse | Phylogenetic/functional diversity indices |

| Data Sources | GBIF, Open Tree of Life, custom data | GBIF occurrence data, OpenTree phylogenies | User-provided species data, trees, distances |

| Implementation | Web-based interface with cloud/HPC support | Nextflow pipeline with Docker/Singularity | R package |

| Key Metrics | Phylogenetic diversity, evolutionary distinctiveness | PD, PE, CANAPE, endemism, richness | Taxonomic, phylogenetic, functional diversity |

| Accessibility | User-friendly web interface | Command-line with containerized deployment | Programming interface (R) |

| Visualization | Interactive maps and charts | Interactive maps, GeoPackage export | Standard R graphics |

Table 2: Data Handling Capabilities Comparison

| Data Aspect | BioDT | PhyloNext | BAT R Package |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Scope | Broad eukaryotic coverage via OToL | User-defined taxa via GBIF backbone | User-defined species lists |

| Spatial Handling | Dynamic spatial binning | H3 hexagonal spatial indexing | User-defined spatial units |

| Temporal Scope | Flexible temporal windows | Year filtering (e.g., post-1945) | Not explicitly defined |

| Data Quality Control | Integrated from PhyloNext | Coordinate precision, uncertainty filters, outlier removal | Dependent on input data |

| Phylogenetic Scale | Full eukaryotic tree of life | Customizable taxonomic subsets | User-provided phylogenetic trees |

Integrated Workflow for Phylogenetic Diversity Analysis

The complementary nature of these tools enables a comprehensive workflow for phylogenetic diversity assessment. BioDT provides the overarching digital twin framework for hypothesis testing and scenario projection, PhyloNext delivers automated data integration and processing capabilities at scale, and BAT offers granular statistical analysis and diversity metric computation for customized analytical approaches. This integration is particularly valuable for conservation planning, where each tool contributes specific capabilities—BioDT for forecasting conservation outcomes, PhyloNext for reproducible continental-scale analyses, and BAT for detailed community-level assessments.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Continental-Scale Phylogenetic Diversity Assessment Using PhyloNext

This protocol enables large-scale phylogenetic diversity analysis using GBIF occurrence data and Open Tree of Life phylogenies, suitable for identifying evolutionary hotspots and conservation priorities across broad geographic regions.

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PhyloNext Analysis

| Component | Source/Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Species Occurrence Data | GBIF (≥2.93 billion records) | Primary distribution data input |

| Phylogenetic Framework | Open Tree of Life (2.3+ million terminals) | Evolutionary relationships |

| Spatial Indexing System | Uber H3 Hexagonal Hierarchy | Geographic binning standardization |

| Computational Environment | Docker/Singularity Container | Reproducible software environment |

| Diversity Calculation Engine | Biodiverse v.4 | Core phylogenetic metric computation |

| Taxonomic Crosswalk | GBIF Backbone + ChecklistBank | Name matching and resolution |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Pipeline Setup and Installation

- Install Nextflow workflow manager (version 22.10+)

- Pull PhyloNext Docker container:

docker pull vmikk/phylonext - Verify installation:

nextflow run vmikk/phylonext -r main --help

Input Parameter Configuration

- Define taxonomic scope using GBIF backbone taxonomy (e.g.,

--family "Felidae,Canidae") - Set geographical boundaries using coordinates or country codes (e.g.,

--country "DE,PL,CZ") - Specify temporal window (e.g.,

--minyear 1945for post-1945 records) - Configure spatial resolution (H3 resolution level 4-6 recommended for continental analyses)

- Define taxonomic scope using GBIF backbone taxonomy (e.g.,

Data Retrieval and Filtering

- Automated download of GBIF occurrence records for specified taxa and region

- Application of quality filters: coordinate precision <0.1°, uncertainty <10,000m

- Removal of spatial outliers using DBSCAN clustering (ε=700km, min points=3)

- Exclusion of fossil specimens, cultivated records, and non-terrestrial occurrences

Spatial Processing and Phylogenetic Integration

- Spatial binning using Uber H3 hexagonal system at specified resolution

- Automated name matching between GBIF species keys and OpenTree taxonomy

- Retrieval of synthetic phylogeny from Open Tree of Life

- Pruning of phylogenetic tree to match species present in filtered occurrence data

Diversity Metric Calculation

- Calculation of phylogenetic diversity (PD), phylogenetic endemism (PE)

- Computation of standardized effect sizes (SES) via randomization (999-1000 iterations)

- CANAPE (Categorical Analysis of Neo- and Paleo-Endemism) classification

- Generation of richness, redundancy, and evolutionary distinctiveness metrics

Output Generation and Visualization

- Export of results in tabular format with H3 cell identifiers

- Generation of GeoPackage files for GIS software integration

- Creation of interactive Leaflet maps for web-based visualization

- Compilation of data provenance and derived dataset DOI for citation

Protocol 2: Fine-Scale Community Diversity Analysis Using BAT R Package

This protocol details the use of the BAT package for detailed analysis of taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional diversity components within ecological communities, enabling comparisons across sites or temporal scales.

Materials and Software Requirements

- R environment (version 3.0.0 or higher)

- BAT package (version 2.11.0 or higher) with dependencies: ape, vegan, phytools, hypervolume

- Species abundance matrix (sites × species)

- Phylogenetic tree (Newick or Nexus format) or functional trait matrix

- Geographic coordinates for spatial analyses (optional)

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation and Import

- Load species abundance data with sites as rows and species as columns

- Import phylogenetic tree and validate tip labels match species names

- Format functional trait data as matrix or distance object

- Check for missing data and apply appropriate imputation or filtering

Alpha Diversity Assessment

- Calculate taxonomic richness:

richness(abundances) - Compute phylogenetic diversity:

pd(abundances, tree) - Estimate functional diversity:

fd(abundances, traits) - Compare diversity components across sites using correlation analysis

- Calculate taxonomic richness:

Beta Diversity Decomposition

- Calculate taxonomic turnover:

beta(abundances) - Partition phylogenetic beta diversity:

beta(abundances, tree) - Assess functional composition changes:

beta(abundances, traits) - Visualize patterns using ordination methods (PCA, PCoA)

- Calculate taxonomic turnover:

Hypothesis Testing

- Compare observed diversity patterns to null models

- Test for correlation between diversity dimensions using Mantel tests

- Assess spatial autocorrelation using Moran's I

- Perform regression analyses to identify environmental drivers

Applications in Biodiversity Research and Conservation

The integration of these tools enables advanced applications across multiple domains of biodiversity science. For conservation prioritization, PhyloNext's CANAPE method identifies areas with significant phylogenetic endemism, highlighting regions with evolutionarily unique lineages that may represent conservation priorities [33]. For climate change impact assessment, BioDT's digital twin capability allows researchers to model how phylogenetic diversity patterns may shift under different climate scenarios, supporting proactive conservation planning [32]. In monitoring program design, BAT's multidimensional beta diversity analysis helps identify representative sites that capture the full spectrum of taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional diversity within a region [35].

For drug discovery professionals, these tools offer valuable applications in bioprospecting and natural product discovery. Phylogenetic diversity metrics can prioritize sampling of evolutionarily distinct lineages that may possess unique biochemical compounds, while spatial phylogenetic analyses can identify regions with high concentrations of evolutionarily distinct species that may represent promising sources for novel molecular structures.

BioDT, PhyloNext, and the BAT R package represent complementary pillars in the modern biodiversity informatics toolkit. PhyloNext excels at automated, large-scale phylogenetic diversity analysis by seamlessly integrating massive data sources from GBIF and Open Tree of Life. BAT provides comprehensive statistical tools for multidimensional diversity analysis within the flexible R environment. BioDT integrates these capabilities within a digital twin framework for predictive modeling and scenario testing. Together, these platforms enable researchers to move beyond simple species counts to capture the evolutionary history, functional potential, and spatial distribution of biodiversity, supporting more informed conservation decisions and advancing our understanding of global biodiversity patterns.

Calculating Phylogenetic Diversity Metrics with Tools like Biodiverse