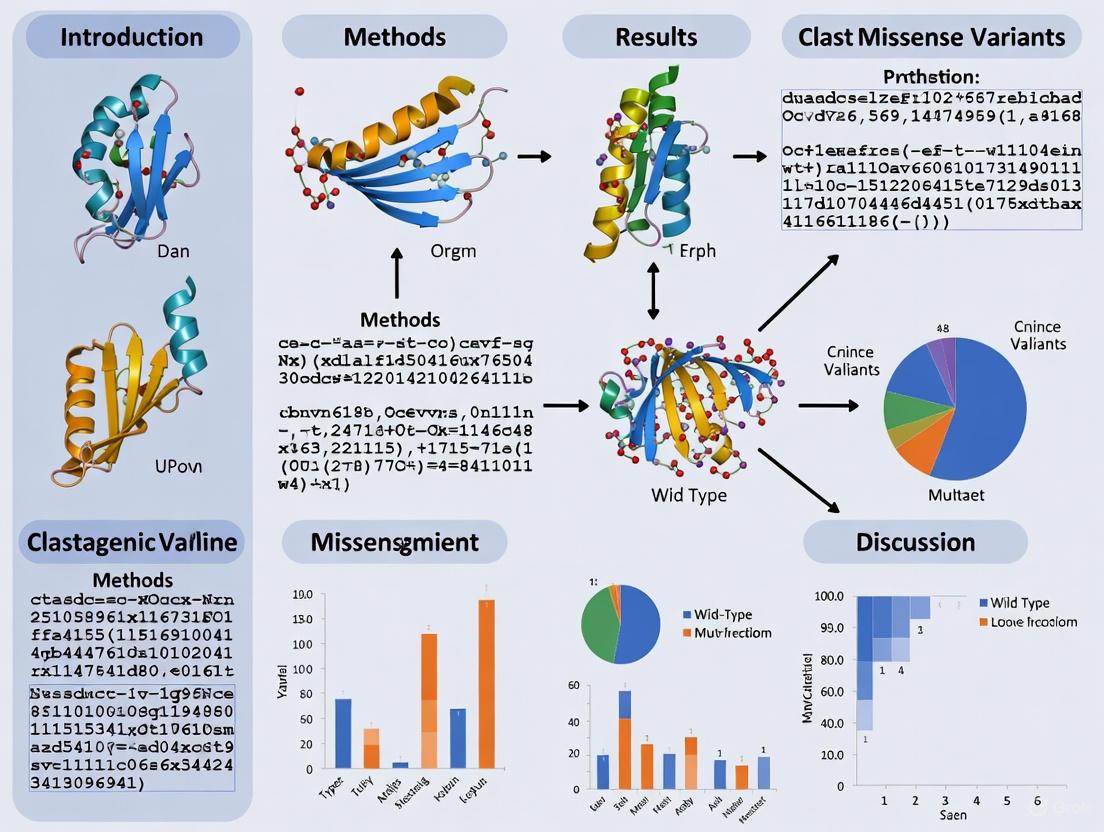

Pathogenic Missense Variant Classification: From VUS to Clinical Action with AI and Structural Biology

Accurate classification of missense variant pathogenicity is a critical challenge in clinical genetics and precision medicine, with over 98% of known variants still classified as Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS).

Pathogenic Missense Variant Classification: From VUS to Clinical Action with AI and Structural Biology

Abstract

Accurate classification of missense variant pathogenicity is a critical challenge in clinical genetics and precision medicine, with over 98% of known variants still classified as Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS). This article synthesizes the latest computational and experimental strategies to address this bottleneck, exploring foundational molecular principles of pathogenicity, advanced machine learning methodologies integrating structural biology and knowledge graphs, optimization techniques for complex cases, and rigorous validation frameworks. For researchers and drug development professionals, we provide a comprehensive roadmap covering disease-specific prediction models, AlphaFold2-enabled structural feature extraction, paralog-based evidence transfer, and emerging approaches for elucidating mode-of-action beyond binary classification to inform therapeutic development and clinical decision-making.

The Molecular Landscape of Missense Variants: From Protein Structure to Clinical Phenotype

In clinical genetics, a Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) represents a genetic change whose impact on health and disease risk is unknown. The classification and management of VUS constitute one of the most significant challenges in modern genomic medicine, creating what this article terms the "interpretation gap"—the disconnect between our ability to detect genetic variants and our capacity to understand their clinical relevance. This gap has profound implications for patient care, research consistency, and therapeutic development.

Recent large-scale studies have quantified the staggering scope of this problem. An analysis of over 1.6 million individuals undergoing hereditary disease genetic testing found that 41% of participants had at least one VUS [1]. The burden of VUS is not equally distributed; it varies dramatically by testing indication and population background. Research reveals that the number of reported VUS relative to pathogenic variants can vary by over 14-fold depending on the primary indication for testing and 3-fold depending on self-reported race [2] [3]. Furthermore, VUS reclassification rates highlight the dynamic nature of this field, with one study finding that at least 1.6% of variant classifications used in electronic health records for clinical care are outdated based on current ClinVar classifications [2].

Quantifying the VUS Burden: Key Statistics

Prevalence and Distribution

Table 1: VUS Prevalence Across Different Studies and Populations

| Study Population | Sample Size | Key Finding on VUS Prevalence | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-gene panel testing | 1.6 million individuals | 41% had at least one VUS | Invitae study [1] |

| Adult genetics practices | 5,158 patients | VUS rate varied 14-fold by testing indication, 3-fold by race | Brotman Baty Institute Database [2] |

| ClinVar database | 206,594 missense variants | 57.5% (118,864) classified as VUS | Nature Communications [4] |

| Variant reclassification | 26 specific instances | Reclassifications never communicated to patients | Folta et al. [2] |

Table 2: Factors Contributing to VUS Interpretation Discordance

| Factor | Impact on VUS Interpretation | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Testing laboratory differences | 43% rate of classification difference for same variant between labs | Interview data with geneticists [5] |

| Clinician expertise | Genetics experts routinely reassess lab interpretations; non-experts report high trust without reassessment | Clinician interviews [5] |

| Population ancestry | Ashkenazi Jewish/White individuals: lowest VUS rates; Pacific Islander/Asian individuals: highest VUS rates | Invitae study [1] |

| Panel size | VUS rate increases with number of genes tested | Analysis of multi-gene panels [1] |

Methodological Frameworks for VUS Interpretation

Standardized Variant Classification Guidelines

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) have established guidelines for variant classification that form the current gold standard. These guidelines categorize variants into five distinct classes:

- Pathogenic and Likely Pathogenic: Variants with sufficient evidence supporting disease causation

- Benign and Likely Benign: Variants with sufficient evidence supporting no clinical significance

- Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS): Variants with insufficient evidence for either pathogenic or benign classification [6]

The ACMG/AMP framework recommends that laboratories report only pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in most clinical contexts, though VUS may be reported in specific circumstances where the information may still have clinical utility [6].

Advanced Computational Methods for Missense Variant Interpretation

Experimental Protocol: ESM1b Protein Language Model for Pathogenicity Prediction

Recent research has demonstrated that protein language models can significantly enhance missense variant interpretation:

- Data Collection: Gather missense variant information from population databases (gnomAD) and clinical databases (ClinVar) [4]

- Feature Extraction: Utilize the ESM1b model to generate numerical scores for all possible amino acid changes

- Variant Scoring: Apply the ESM1b scoring system where scores less than -7.5 indicate likely pathogenic missense variants [4]

- Phenotype Correlation: Correlate ESM1b scores with clinical phenotypes across multiple genes

- Validation: Assess prediction accuracy against known variant classifications and clinical outcomes

This methodology has shown remarkable predictive power, with ESM1b scores significantly predicting mean phenotype of missense variant carriers in six of ten cardiometabolic genes studied (binomial enrichment p = 2.76E-06) [4]. The model can also distinguish between loss-of-function and gain-of-function variants, providing crucial functional insights beyond simple pathogenicity classification.

Integrated Workflow for VUS Assessment and Reclassification

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive VUS Reclassification System

Data Integration

- Extract variant information from electronic health records (EHR)

- Cross-reference with public databases (ClinVar, OMIM, GeneReviews)

- Incorporate population frequency data (gnomAD, 1000 Genomes)

Evidence Aggregation

- Collect clinical patient data and phenotype information

- Perform segregation analysis within families

- Incorporate functional study results from literature

- Utilize computational predictions from multiple algorithms

Multidisciplinary Review

- Convene variant review committees with clinical and laboratory geneticists

- Assess evidence strength using ACMG/AMP criteria

- Make classification decisions based on aggregated evidence

Reclassification Communication

This systematic approach has demonstrated real-world impact, with one study identifying 26 instances where testing laboratories updated ClinVar with variant reclassifications, but this critical information was never communicated to the affected patients [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for VUS Interpretation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Databases | ClinVar, ClinGen, Franklin Genoox | Aggregate variant classifications and evidence | Centralized repository of clinical interpretations with multiple submitter data [7] |

| Population Databases | gnomAD, 1000 Genomes, dbSNP | Provide allele frequency across populations | Filtering of common polymorphisms; identification of rare variants [8] |

| Computational Prediction Tools | ESM1b, AlphaMissense, PolyPhen-2, SIFT | Predict functional impact of missense variants | Integration of evolutionary conservation and structural features [8] [4] |

| Clinical Resources | GeneReviews, OMIM | Curated gene-disease relationships and clinical management | Expert-reviewed clinical summaries and practice guidelines [7] |

| Protein Structure Tools | AlphaFold2, PDBe, PDB | Provide protein structural context | Assessment of variant impact on protein folding and function [8] |

| Visualization Platforms | IGV, UCSC Genome Browser | Genomic context visualization | Integration of multiple data types for variant interpretation |

Troubleshooting Common VUS Interpretation Challenges

FAQ 1: How should we handle discrepant variant classifications between different testing laboratories?

Issue: Variant classifications for the same variant differ between laboratories, creating clinical confusion.

Solution:

- Review the specific evidence cited by each laboratory for their classification

- Consult independent databases such as ClinVar to assess consensus classification

- Evaluate whether clinical features in your patient support one classification over another

- Consider orthogonal testing methods or referral to specialized centers for complex cases

- Document the rationale for ultimately following a particular classification [5]

Genetic counselors report that disagreements with laboratory variant classifications, while uncommon, most frequently stem from conflicting laboratory interpretations or discrepancies in clinical correlation [7].

FAQ 2: What is the most effective approach for VUS reclassification?

Issue: VUS reclassification rates are substantial, but systematic approaches are lacking.

Solution:

- Implement proactive monitoring systems for previously identified VUS

- Establish clear institutional protocols for reassessment timelines and triggers

- Prioritize VUS in genes with strong disease association and available functional data

- Utilize computational methods like ESM1b scores that show strong correlation with phenotype severity [4]

- Develop standardized patient re-contact procedures for clinically significant reclassifications

Research indicates that clinical evidence, including detailed patient information and family studies, contributes most significantly to VUS reclassifications [1].

FAQ 3: How can we address disparities in VUS rates across different ancestral populations?

Issue: Individuals from non-European ancestries experience higher VUS rates, exacerbating health disparities.

Solution:

- Prioritize inclusion of diverse populations in genomic research databases

- Utilize population-specific allele frequency databases when available

- Advocate for funding and research focused on variant interpretation in underrepresented groups

- Implement careful pre-test counseling about VUS likelihood based on patient ancestry

- Support efforts to develop ancestry-informed computational prediction models [1]

Studies demonstrate that Ashkenazi Jewish and White individuals have the lowest observed VUS rates, while Pacific Islander and Asian individuals have the highest, highlighting the critical need for more diverse genomic data [1].

FAQ 4: What clinical guidance should be provided for VUS findings?

Issue: Uncertainty about appropriate clinical management when a VUS is identified.

Solution:

- Base clinical management on personal and family history, not VUS findings alone

- Document clear rationale against basing clinical decisions on VUS status

- Provide ongoing counseling about the possibility of future reclassification

- Establish systems to track VUS and facilitate reassessment over time

- Encourage patients to update contact information to enable future re-contact [7]

Genetic counselors report that most do notify patients of reclassification from VUS to pathogenic or benign categories, though communication methods vary, indicating a need for standardized protocols [7].

Future Directions: Closing the Interpretation Gap

The field of VUS interpretation is rapidly evolving with several promising approaches to reduce the interpretation gap. Machine learning methods are showing substantial progress, with one commercial laboratory reporting that their AI-driven approaches have already helped reduce uncertain results for over 300,000 individuals [1]. Integration of polygenic risk scores with monogenic variant analysis represents another promising avenue, as research demonstrates that polygenic background significantly modifies phenotype among pathogenic variant carriers [4]. Advanced sequencing technologies including long-read sequencing and single-cell approaches are improving variant detection in technically challenging regions, potentially resolving previously unclassifiable variants [9].

The systematic implementation of evidence-based frameworks for variant interpretation and reclassification, coupled with standardized protocols for communicating updated information to patients and providers, will be essential for addressing the current VUS challenge. As these approaches mature, the field moves closer to realizing the full potential of precision medicine by ensuring that genetic findings translate to clear clinical guidance rather than uncertainty.

Interpreting the clinical significance of genetic variants is a cornerstone of modern genomic medicine. For missense variants, this task is particularly challenging as their effect on protein function is not always obvious. The three-dimensional structure of a protein provides a critical physical framework for understanding how and why certain amino acid changes lead to disease. Proteins perform their functions through precise arrangements of domains, surfaces, and interaction interfaces, and pathogenic missense variants are not randomly distributed across these structural elements. Research has consistently demonstrated that these variants cluster in structurally and functionally important regions, including protein-protein interaction interfaces, catalytic sites, and structurally constrained cores [10] [11]. This technical support document provides researchers and drug development professionals with practical guidance for leveraging structural biology in variant interpretation, framed within the context of investigating these enrichment patterns.

Core Concepts: Structural Enrichment of Pathogenic Variants

Quantitative Enrichment Patterns

Large-scale studies analyzing atomic-resolution interactomes have revealed distinct statistical patterns in the distribution of pathogenic variants. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings on the enrichment of pathogenic variants in different structural regions.

Table 1: Enrichment of Pathogenic Missense Variants Across Protein Structural Regions

| Structural Region | Enrichment Observation | Statistical Significance & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction Interface | Significant enrichment of in-frame pathogenic variations [10] | Considered "hot-spots"; alterations are significantly more disruptive than evolutionary changes [10] |

| Entire Interacting Domain | Enrichment of pathogenic variations, not limited to interface residues [10] | Suggests the entire domain's structural integrity is crucial for proper interaction [10] |

| Buried Residues (Low Solvent Accessibility) | Pathogenic variants strongly associated with low Relative Solvent Accessibility (RSA) [12] | p = 2.89e-2,276; proteins are less tolerant of buried mutations [12] |

| Regular Secondary Structures (Alpha helices, Beta-sheets) | Tendency for mutations to be pathogenic [12] | Odds Ratio (OR) for alpha helices: 1.73; OR for beta-sheets: 1.97 [12] |

| Disulfide Bonds | Very high likelihood of pathogenicity if disrupted [12] | Odds Ratio (OR) = 93.8; 98.72% of disruptive variants were pathogenic [12] |

| Loops/Irregular Stretches | Tendency for mutations to be benign [12] | Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.32 [12] |

Key Structural Principles of Pathogenicity

The quantitative data above supports several core principles:

- Interface Disruption: Variations at interaction "hot-spots" can directly disrupt the biophysical strength of protein-protein interactions [10].

- Structural Destabilization: Pathogenic variations often introduce substantial changes in protein stability (measured as ΔΔG), more so than benign variants [12]. This can lead to misfolding, aggregation, or degradation.

- Domain-Wide Integrity: The enrichment of pathogenic variants across entire interacting domains, not just the direct contact residues, underscores that the overall structural fold and stability of a domain are essential for its function [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Our lab has identified a VUS in a gene of interest. The variant is buried in the protein core with low RSA. How should we prioritize it for further analysis?

A variant with low RSA is a higher priority for functional analysis. Buried residues are critical for maintaining the protein's stable core. Mutations in these regions often destabilize the protein's native fold, leading to loss of function. You should:

- Calculate the predicted change in stability (ΔΔG) using tools like FoldX.

- Check if the residue is highly conserved.

- A significantly destabilizing ΔΔG (e.g., < -2 kcal/mol) and high conservation strongly suggests pathogenicity [13] [12]. Proceed with functional assays to test for protein expression, stability, and localization.

FAQ 2: A variant is located in a loop region, which is often considered more tolerant of mutation. However, our structural model shows it is near the active site. How do we resolve this?

Loop regions can be functionally important despite their general tolerance. Proximity to an active site is a major red flag. You must investigate:

- Direct Involvement: Does the loop form part of the active site cavity?

- Allosteric Role: Could a mutation in this loop affect the dynamics or precise positioning of active site residues? Use Structure-Based Network Analysis (SBNA) to quantify the residue's topological importance within the 3D network; a high network score would indicate critical structural importance despite being in a loop [11].

FAQ 3: We are studying a variant that disrupts a salt bridge not at a known interaction interface. What is the potential mechanism of pathogenicity?

The disruption of a stabilizing salt bridge is a classic mechanism for pathogenic loss-of-function. Even if not at an interface, this can:

- Reduce Global Stability: Lower the protein's melting temperature and increase its propensity to unfold or aggregate.

- Alter Local Conformation: Impair the precise geometry of a functional pocket or allosteric site.

- Affect Dynamics: Hinder necessary conformational changes required for function. Evaluate the ΔΔG and correlate with clinical data. In vitro thermal shift assays are an excellent method for experimental validation [13].

FAQ 4: When using predicted structures from AlphaFold2, how reliable are they for calculating stability metrics (ΔΔG) and identifying interface residues?

AlphaFold2 has expanded structural coverage of the human proteome dramatically. Studies show that for regions with high per-residue confidence scores (pLDDT > 80), AlphaFold2 structures can be used to compute stability metrics with accuracy similar to experimentally determined structures [13] [12]. However, high-quality experimental structures (e.g., from X-ray crystallography) should still be preferred when available, as they can outperform AlphaFold2 in stability calculations [13]. For interface prediction, the newer AlphaFold3 promises better modeling of complexes, but this has yet to be fully validated for variant interpretation [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Validating a Putative Protein-Protein Interaction Disruptor

Problem: A VUS is predicted to lie at a protein-protein interaction interface, but you need experimental validation that it disrupts the interaction.

Solution: A Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) assay is a well-established method for this purpose.

Workflow Overview: The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for this experimental validation.

Detailed Protocol:

- Generate Variants: Using the wild-type cDNA clone (e.g., from the human ORFeome collection), generate the specific VUS allele via site-directed mutagenesis. Use a kit such as the Stratagene QuikChange Kit and mutagenic primers designed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Perform mutagenesis PCR with a high-fidelity polymerase like Phusion [10].

- Clone into Y2H Vectors: Clone both the wild-type and VUS sequences into appropriate Y2H vectors (e.g., pGBKT7 as bait and pGADT7 as prey).

- Co-transform Yeast: Co-transform the bait and prey plasmids into a suitable yeast strain (e.g., AH109 or Y2HGold).

- Select for Diploids: Plate the transformed yeast on synthetic dropout (SD) media lacking Leucine and Tryptophan (SD/-Leu/-Trp) to select for cells containing both plasmids. Incubate at 30°C for 3-5 days.

- Assay for Interaction: Restreak positive colonies onto more stringent selective media, typically SD media lacking Adenine and Histidine (SD/-Ade/-His) and supplemented with X-α-Gal. A successful protein-protein interaction will activate reporter genes, allowing growth and turning colonies blue.

- Interpret Results: Compare the growth and color of yeast containing the VUS pair against the wild-type positive control and empty vector negative controls. Lack of growth/blue color suggests the VUS disrupts the interaction.

Guide: Choosing the Right Protein Structure for Analysis

Problem: Inconsistent results from in silico tools due to the use of different protein structures or models.

Solution: Follow a structured hierarchy for selecting the most reliable protein structure.

Workflow Overview: The diagram below outlines the decision-making process for structure selection.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check the PDB: Always first search the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for an experimentally determined structure.

- Prioritize by Method: Prefer high-resolution X-ray crystallography or high-quality Cryo-EM structures. NMR structures, while informative for dynamics, are less suitable for computing stability metrics due to their conformational ensembles [13].

- Evaluate Quality: If multiple structures exist, choose the one with the highest resolution and completeness for your region of interest.

- Use Predictions if Necessary: If no experimental structure exists, use a predicted structure from AlphaFold2 (via the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database). Focus your analysis on regions with high per-residue confidence (pLDDT > 80) [12].

- Consider Homology Modeling: As an alternative, check repositories like SWISS-MODEL for homology models, but native or ab initio predicted structures are generally preferred [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

This table lists key materials and tools required for experiments investigating the structural basis of variant pathogenicity.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Structural Pathogenicity Analysis

| Category / Item Name | Specific Example / Vendor | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cloning & Mutagenesis | ||

| Human ORFeome Collection | e.g., Human ORFeome v8.1 [10] | Source of wild-type, sequence-verified cDNA clones for a wide array of human genes. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | e.g., Stratagene QuikChange Kit [10] | Introduces specific nucleotide changes into plasmid DNA to create VUS and control constructs. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | e.g., Phusion Polymerase (NEB) [10] | Used for accurate amplification during mutagenesis PCR to avoid introducing secondary mutations. |

| Interaction Validation | ||

| Yeast Two-Hybrid System | e.g., MATCHMAKER Gal4 System (Clontech) | In vivo method to test for protein-protein interaction disruption by a variant [10]. |

| Y2H Yeast Strain | e.g., AH109, Y2HGold | Genetically engineered yeast strains with multiple auxotrophic markers for selection. |

| Structural Analysis Software | ||

| Molecular Visualization | UCSF Chimera, PyMOL | Visualizes 3D structures, maps variants, and analyzes residue burial and contacts. |

| Stability Prediction | FoldX [13] [12] | Industry-standard tool for predicting the change in protein stability (ΔΔG) upon mutation. |

| Structure-Based Network Analysis | Custom SBNA scripts [11] | Quantifies topological importance of a residue within the 3D protein structure network. |

| Solvent Accessibility | Naccess [10] | Calculates Relative Solvent Accessibility (RSA) from PDB files. |

| Structural Databases | ||

| Experimental Structures | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [10] [13] | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins. |

| Predicted Structures | AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [12] | Database of AlphaFold2 predictions for a large portion of the human proteome. |

| Domain Interactions | 3did, iPfam [10] | Curated databases of protein domain-domain interactions. |

Evolutionary Conservation and Paralogous Genes as Evidence for Pathogenicity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: What is a paralogous variant and how can it serve as evidence for pathogenicity?

A paralogous variant is a missense variant located in a paralogous gene at the analogous residue position, as defined by a multiple sequence alignment across a gene family, and it shares the same reference amino acid as the target gene [14].

The presence of a pre-classified pathogenic variant at this conserved position in a paralogous gene provides quantifiable evidence for the pathogenicity of a novel variant in your gene of interest. Systematic analyses show that this evidence, termed the para-SAME criterion, is associated with a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 13.0 for variant pathogenicity. Even a pathogenic variant with a different amino acid change at the same position (the para-DIFF criterion) has an LR+ of 6.0 [14].

Q2: Why is my variant still a VUS even though a pathogenic variant exists in a paralog?

This typically occurs for one of the following reasons:

- Insufficient Sequence Similarity: The paralogous gene used for comparison may not share a high enough degree of sequence similarity (>90% in key domains) to confidently transfer pathogenic evidence. Always verify the quality of the multiple sequence alignment.

- Lack of Gene-Family Specific Calibration: The strength of evidence from paralogous variants can differ significantly across gene families [14]. General guidelines may not be calibrated for your specific gene family.

- Conflicting Evidence: Other lines of evidence, such as population frequency or computational predictions, may conflict with the paralog-based evidence, preventing an upgrade from VUS to Likely Pathogenic.

Q3: How many pathogenic paralogous variants are needed for strong evidence?

While a single pathogenic variant in a paralog provides moderate evidence, the strength of evidence increases with the number of independent pathogenic variants found at the same conserved residue across multiple paralogs within the gene family [14]. The fold enrichment of pathogenic variants progressively rises with a higher number of supporting paralogous variants.

Q4: How do I handle phenotypes when using paralogous evidence?

Phenotype patterns can be conserved across paralogs. For example, in voltage-gated sodium channels, loss-of-function related disorders in genes like SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN5A, and SCN8A show overlapping spatial variant clusters in 3D protein structures [14]. When selecting paralogous variants as evidence, consider if the associated disorders in the paralog share a similar molecular disease mechanism with the disorder linked to your target gene. Integrating phenotype data can improve variant classification.

Q5: What are the best tools for identifying and analyzing paralogous genes and variants?

The table below summarizes essential tools for this workflow.

Table 1: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Paralog and Variant Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Application in This Context | Source/Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST | Sequence similarity search | Identifying paralogous genes via sequence comparison [15] [16]. | NCBI |

| Clustal Omega / MAFFT | Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Creating alignments to find conserved residue positions across paralogs [15]. | EMBL-EBI |

| HAMAP-Scan | Protein family classification | Scanning sequences against curated protein families [17]. | Expasy |

| OrthoDB | Cataloging orthologs & paralogs | Providing evolutionary and functional annotations for paralogs [17]. | OrthoDB |

| AlphaMissense | Pathogenicity prediction | Computational evidence for missense variant pathogenicity [18]. | Google Research |

| gnomAD | Population variant frequency | Assessing variant frequency to find benign controls [14] [19]. | gnomAD |

| UCSC Genome Browser | Genome visualization | Visualizing variant conservation across paralogous regions [19]. | UCSC |

| SAMtools | Handling sequence data | Processing and manipulating alignment files (BAM/VCF) [16]. | SAMtools |

Quantitative Data on Paralogous Variant Evidence

The following table summarizes the key quantitative findings from a large-scale exome study on using paralogous variants as evidence for pathogenicity [14].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Integrating Paralogous Variant Evidence

| Metric | Gene-Specific Evidence Only | With Paralogous Evidence | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classifiable Amino Acid Residues | 22,071 residues | 83,741 residues | 3.8-fold increase |

| Positive Likelihood Ratio (LR+) | |||

| • para-SAME (same AA change) | N/A | 13.0 (95% CI: 12.5-13.7) | N/A |

| • para-DIFF (different AA change) | N/A | 6.0 (95% CI: 5.7-6.2) | N/A |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Pathogenic Variants in Paralogous Genes

This protocol outlines the steps to systematically gather evidence from paralogs for a missense VUS.

1. Define the Gene Family: * Input: Your gene of interest (e.g., PRPS1). * Method: Use databases like HGNC, OrthoDB, or PANTHER to identify all members of the gene family [20] [17]. * Output: A list of paralogous genes (e.g., for PRPS1, this includes PRPS2, PRPS3, PRPSAP1, PRPSAP2).

2. Perform Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): * Input: Protein sequences for all paralogs. * Method: Use a tool like Clustal Omega or MAFFT to generate a high-quality MSA [15]. * Troubleshooting: If alignment quality is poor in key domains, consider aligning specific protein domains identified via Pfam or PROSITE [19] [17]. * Output: A residue-to-residue alignment mapping your VUS position to the equivalent positions in all paralogs.

3. Mine Variant Databases: * Input: The equivalent amino acid positions in all paralogs. * Method: Query clinical databases (ClinVar, HGMD) and population databases (gnomAD, ExAC) for all variants at these aligned positions [14] [19]. * Output: A list of pre-classified variants (Pathogenic, Likely Pathogenic, Benign, etc.) at the conserved residue across the gene family.

4. Apply Classification Criteria: * Input: The list of variants from Step 3. * Method: * If a Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic variant with the identical amino acid change is found, apply the para-SAME criterion. * If a Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic variant with a different amino acid change is found, apply the para-DIFF criterion. * Output: Supporting evidence for pathogenicity (at the supporting, moderate, or strong level, depending on gene-family specific calibration) for your VUS.

Protocol 2: Calibrating Paralogous Evidence for a Specific Gene Family

To use paralogous evidence quantitatively, gene-family specific calibration is recommended [14].

1. Curate a Gold-Standard Variant Set: * Compile known pathogenic variants (from ClinVar/HGMD) and benign population variants (from gnomAD) for all genes in the family.

2. Map Variants to MSA: * Map all variants to the multiple sequence alignment to identify residues with variants in multiple paralogs.

3. Calculate Likelihood Ratios (LR):

* For a given residue, calculate the LR as follows:

LR = (Probability residue is in a pathogenic variant | Pathogenic) / (Probability residue is in a pathogenic variant | Benign)

* This calculates how much more likely it is to find a pathogenic variant at a residue that is "hit" by a pathogenic paralogous variant compared to a benign variant.

4. Establish Evidence Strength Thresholds: * Based on the calculated LRs, define thresholds for supporting, moderate, and strong levels of evidence for your gene family, similar to the ACMG/AMP guidelines for PS1 and PM5 criteria [21].

Identifying Pathogenic Variants in Paralogous Genes Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Databases for Paralog-Based Pathogenicity Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| ClinVar | Database | Public archive of reports of human genetic variants and interpretations [14] [18]. | NIH/NCBI |

| HGMD (Human Gene Mutation Database) | Database (Commercial) | Comprehensive collection of published pathogenic mutations in human genes [14]. | Qiagen |

| gnomAD (Genome Aggregation Database) | Database | Population genome variant frequency database; used as a source of benign control variants [14] [19]. | Broad Institute |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot | Database | Expertly curated protein sequence and functional information [17]. | SIB Swiss Institute |

| HGNC Gene Family Data | Database | Authoritative gene families as defined by the Human Gene Nomenclature Committee [14]. | HGNC |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Computational Tool | Fundamental for identifying conserved residue positions across paralogs [14]. | Clustal Omega, MAFFT |

Evolutionary Relationship of Paralogous Genes

FAQs: Core Concepts and Molecular Features

FAQ 1: What are the key molecular and cellular features that differentiate pathogenic missense variants from benign ones?

Pathogenic and benign missense variants can be distinguished by their distinct molecular footprints across protein structure, functional pathways, and proteomic properties. The following table summarizes the key differentiating features identified through large-scale analyses.

Table 1: Key Molecular Features Differentiating Pathogenic and Benign Variants

| Feature Category | Pathogenic Variant Association | Benign (Population) Variant Association |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structural Region | Enriched in protein cores and interaction interfaces [22] | Enriched on protein surfaces and in disordered regions [22] |

| Functional Pathways | Affect cell proliferation and nucleotide processing pathways [22] | Not strongly associated with specific pathways in this analysis [22] |

| Protein Abundance | Found in more abundant proteins [22] | No strong correlation with abundance [22] |

| Protein Stability | Often predicted to be destabilizing to protein structure [23] [24] | Often predicted to have neutral stability effects [23] |

| Downstream Proteomic Effect | Destabilizing pathogenic variants linked to lower protein levels in cancer samples [23] | Not associated with significant changes in protein levels [23] |

FAQ 2: How does the local 3D structural context of a variant influence its pathogenicity?

The location of a missense variant within a protein's three-dimensional structure is a major determinant of its functional impact. Pathogenic variants are significantly enriched in buried residues that form the protein core and at residues that form interfaces with other molecules. In contrast, population variants are more common on the solvent-accessible protein surface. This is because residues in the core are often critical for maintaining structural stability, while interface residues are essential for specific binding and signaling functions. Variants on the surface or in intrinsically disordered regions are more likely to be tolerated, as they less frequently disrupt the protein's fundamental architecture [22]. Furthermore, a study exploring mechanistic impacts found that disease-linked variants are enriched in predicted small-molecule binding pockets and at protein-protein interfaces [23].

FAQs: Experimental Approaches and Validation

FAQ 3: What high-throughput experimental methods can functionally profile thousands of missense variants at once?

Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) is a powerful framework for exhaustively mapping the functional consequences of missense variants. The core workflow involves creating a vast library of variant genes, expressing them in a system where protein function influences a selectable outcome (like cell growth), and using high-throughput sequencing to quantify the effect of each variant.

Table 2: Key Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) Methodologies

| Method Stage | Description | Key Techniques/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Mutagenesis | Generation of a library containing all possible amino acid substitutions. | Random codon mutagenesis (e.g., POPCode) to ensure even coverage [25]. |

| 2. Library Generation | Cloning the variant library into an expression system. | Can be barcoded (DMS-BarSeq) for tracking individual variants or tiled (DMS-TileSeq) for direct variant sequencing [25]. |

| 3. Functional Selection | Applying a selection pressure linked to protein function. | Often uses functional complementation assays in yeast or other models to test if variants rescue a loss-of-function phenotype [25]. |

| 4. Readout & Analysis | Quantifying variant fitness from selection results. | High-throughput sequencing of barcodes or tiled amplicons before and after selection to calculate enrichment/depletion [25]. |

The diagram below illustrates the two primary DMS workflows.

FAQ 4: How can I validate the functional impact of a specific missense variant in a live animal model?

Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is a simple, cost-effective in vivo model for functional validation. The protocol involves:

- Ortholog Analysis: Identify the C. elegans ortholog of the human gene of interest. Approximately 250 human disease genes have clear orthologs in C. elegans, and about half of documented human variants in these genes are missense variants of uncertain significance [26].

- Strain Generation: Use CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to introduce the specific human missense variant into the orthologous C. elegans gene.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Conduct assays to compare the phenotype of the variant-bearing worm to wild-type and known loss-of-function mutants. Phenotypes can include morphological defects, changes in lifespan or reproduction, and sensitivity to stress.

- Rescue Experiments: Test if the observed pathogenic phenotype can be rescued by supplementation with a relevant molecule, such as coenzyme Q10 for variants in the COQ2 ortholog, coq-2 [26].

This approach provides direct, quantitative phenotypic data on the functional consequences of a variant in a living organism.

FAQs: Computational Prediction and Troubleshooting

FAQ 5: A widely-used computational predictor (AlphaMissense) classified my variant as pathogenic, but my experimental data suggests it is benign. Why might this happen?

Discordance between computational predictions and experimental or clinical findings is a known challenge. A 2025 study highlighted specific limitations of deep learning models like AlphaMissense:

- Performance Gaps: When evaluated on a rare disease cohort, AlphaMissense showed a precision of only 32.9%, meaning many variants it flagged as likely pathogenic were not classified as such by expert curation in ClinVar [27].

- Intrinsic Disorder: AlphaMissense and other models struggle to accurately evaluate pathogenicity in intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which lack a fixed 3D structure, leading to unreliable predictions in these protein segments [27].

- Splice Effects: Some variants classified as missense may actually affect mRNA splicing. In one analysis, 5-7% of pathogenic missense variants not caught by predictors had potential splice-disrupting effects, which the missense-focused models would not account for [27].

Always correlate computational predictions with other lines of evidence, such as population frequency, evolutionary conservation, and functional assay data, before drawing conclusions.

FAQ 6: With over 97 variant effect predictors (VEPs) available, how do I choose one and avoid biased evaluations?

Choosing and evaluating VEPs requires careful consideration to avoid data circularity, which can make predictors seem more accurate than they are. The following table compares a selection of widely used predictors.

Table 3: Comparison of Selected Variant Effect Predictors (VEPs)

| Predictor Name | Underlying Approach | Score Range & Interpretation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaMissense | Deep learning (based on AlphaFold2), fine-tuned on population frequency [28] [27] | 0 to 1; <0.34 Benign, >0.56 Pathogenic [28] | Struggles with disordered regions; author thresholds may favor recall over precision [27]. |

| REVEL | Ensemble method combining 13 other tools [29] [28] | 0 to 1; Higher scores = more likely pathogenic [28] | An established meta-predictor that integrates multiple independent signals. |

| SIFT | Evolutionary conservation of amino acids [30] [28] | 0 to 1; <0.05 Deleterious [28] | One of the earliest and most widely used methods. |

| PolyPhen-2 | Physical/ comparative considerations of protein structure/function [30] [28] | 0 to 1; Higher scores = more likely deleterious [28] | Provides a probability of a variant being damaging. |

| CADD | Integrates diverse genomic annotations into one score [30] | Phred-scaled score; Higher scores = more likely deleterious | Not trained solely on human clinical variants, reducing some circularity [30]. |

To perform a robust benchmark of VEPs, use data from Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) experiments. DMS data provides several advantages: it does not rely on pre-assigned clinical labels (reducing variant-level circularity), and performance can be compared on a per-protein basis (reducing gene-level circularity) [31]. Studies show a strong correspondence between a VEP's performance on DMS benchmarks and its ability to classify clinical variants correctly, especially for predictors not directly trained on human variant data [31].

FAQ 7: How can I visualize the decision-making process of a machine learning model for variant classification?

The LEAP (Learning from Evidence to Assess Pathogenicity) model provides a framework for explainable machine learning in variant classification. It ranks evidence features by their contribution to the final prediction. The diagram below illustrates a simplified, generalizable workflow for how such a model might integrate different evidence categories to classify a variant.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Variant Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| gnomAD Database | Population Database | Provides allele frequencies from a large population, serving as a key resource for assessing variant rarity and prioritizing benign variants [22] [29]. |

| ClinVar Database | Clinical Database | A public archive of reports on the relationships between human variants and phenotypes, with supporting evidence [22] [27]. |

| COSMIC Database | Disease Database | Catalogs somatic mutations in human cancer, useful for identifying driver mutations in oncology research [22]. |

| AlphaFold2 DB | Structural Database | Provides high-accuracy predicted protein structures for the human proteome, enabling structural analysis of variants when experimental structures are unavailable [23]. |

| ZoomVar Database | Integrated Resource | A database that allows programmatic annotation of missense variants with protein structural information and calculation of variant enrichment in different protein regions [22]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Molecular Tool | Enables precise genome editing to introduce specific missense variants into model organisms (e.g., C. elegans) for functional validation [26]. |

| Yeast Complementation Assay | Functional Assay | A classical genetics technique adapted for high-throughput DMS to test the functional impact of human gene variants by rescuing a deficient yeast strain [25]. |

Advanced Computational Frameworks: AI, Knowledge Graphs, and Structural Biology

Graph Neural Networks for Disease-Specific Variant Interpretation

FAQs: Model Selection and Implementation

Q1: What are the key advantages of using a Graph Neural Network over traditional methods for variant interpretation?

Traditional methods often treat genetic variants as independent entities, overlooking the complex biological relationships between genes, proteins, and diseases. GNNs excel by integrating diverse biomedical data into a knowledge graph, allowing them to capture these relationships. For disease-specific prediction, a key advantage is the ability to predict edges between variant and disease nodes within a graph, essentially determining whether a variant is pathogenic in the context of a specific disease [32]. This is a more clinically useful approach than disease-agnostic models.

Q2: My GNN model for pathogenicity prediction is performing well on known disease genes but fails to generalize. What could be wrong?

This is a common challenge. Many models are not calibrated across the entire proteome, meaning their scores are not designed to compare variant deleteriousness in one gene versus another [33]. To address this, consider using a model like popEVE, which leverages both deep evolutionary data and shallow human population data (e.g., from gnomAD) to transform scores to reflect human-specific constraint. This provides a continuous, proteome-wide measure of deleteriousness, enabling more meaningful comparisons across different proteins [33].

Q3: How can I integrate protein structure data into my GNN model for variant interpretation?

You can leverage tools like AlphaFold2 to generate predicted protein structures for features. Rhapsody-2 is a machine learning tool that does precisely this; it uses AlphaFold2-predicted structures to generate a set of descriptors including 17 structural, 21 dynamics-based, and 33 energetics-based features [34]. These features can be incorporated as node or edge attributes in your biological network to provide a more mechanistic interpretation of variant pathogenicity.

Q4: What is the recommended way to handle Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in a GNN framework?

A powerful approach is to build a comprehensive knowledge graph that interconnects various biomedical entities (proteins, diseases, phenotypes, drugs, etc.). You can then train a two-stage architecture: first, a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to encode the complex biological relationships in this graph, and second, a neural network classifier to predict disease-specific pathogenicity [32]. This method allows you to integrate domain knowledge and essentially predict new pathogenic links for VUS.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Pitfalls and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common GNN Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor model generalizability to new genes. | Model is overfitting to features of known disease genes and lacks proteome-wide calibration. | Incorporate population data (e.g., from gnomAD) to calibrate evolutionary scores, as done in popEVE, enabling cross-gene comparison of variant deleteriousness [33]. |

| Low contrast in model visualization hinders interpretation. | Color choices for graphs/charts do not meet accessibility standards. | Ensure a minimum contrast ratio of 3:1 for graphical objects like bars in a chart and 4.5:1 for text against backgrounds. Use tools like the WebAIM Contrast Checker [35]. |

| Model performance is biased towards specific ancestries. | Training data from population databases (e.g., GnomAD) over-represents certain groups. | Use methods that rely on coarse measures of variation ("seen" vs. "not seen") rather than precise allele frequencies, which can reduce population structure bias [33]. |

| Difficulty interpreting why the GNN made a specific prediction. | The GNN operates as a "black box," lacking explainability. | Employ interpretable GNN architectures. For pathway identification, combine GNNs with a Genetic Algorithm to identify key sub-netflows, or use methods that provide attention weights to highlight important nodes [36]. |

| Integrating genomic sequence data is computationally challenging. | Processing long DNA sequences into model inputs is non-trivial. | Use a DNA language model like HyenaDNA to generate dynamic gene embeddings directly from nucleotide sequences, which can then be used as features for downstream GNN tasks [36]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Methodology: A Two-Stage GNN for Disease-Specific Prediction

This protocol is adapted from a study that classified missense variants from ClinVar using a comprehensive knowledge graph [32].

Knowledge Graph Construction:

- Nodes: Incorporate 10+ types of biomedical entities (e.g., Protein, Disease, Drug, Phenotype, Pathway, Biological Process) [32].

- Edges: Connect nodes with 30+ relationship types (e.g., Disease-Gene association, Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI), Drug-Target). Enrich PPIs by classifying them as "transient" or "permanent" using time-course gene expression co-expression data [32].

- Variant Integration: Connect genetic variants to their associated gene nodes. Connect pathogenic variants to their known disease nodes, adding new disease nodes from ClinVar if necessary [32].

Feature Generation:

Model Training (Two-Stage Architecture):

- Stage 1 - Graph Encoding: Train a Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCN) on the knowledge graph to encode the complex biological relationships [32].

- Stage 2 - Classification: Feed the graph encodings into a standard neural network classifier. The goal is to predict the existence of edges between variant and disease nodes, i.e., disease-specific pathogenicity [32].

Workflow Diagram: Two-Stage GNN for Variant Interpretation

Table 1: Performance of popEVE on Severe Developmental Disorder (SDD) Cohort

This table summarizes the model's ability to capture variant severity by analyzing De Novo Missense Mutations (DNMs) [33].

| Metric | Value / Observation | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Enrichment in SDD Cases | DNMs in cases were consistently shifted toward higher predicted deleteriousness. | Comparison of 31,058 SDD cases vs. unaffected controls [33]. |

| High-Confidence Threshold | Score threshold set at -5.056. | Variants below this threshold have a 99.99% probability of being highly deleterious [33]. |

| Fold Enrichment | 15-fold enriched in the SDD cohort. | Measured for variants below the high-confidence severity threshold [33]. |

| Performance vs. Other Methods | 5x higher enrichment than other methods (e.g., PrimateAI-3D). | Benchmarking against established tools [33]. |

A list of essential databases and tools used in the cited research.

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ClinVar [32] [34] | Public Archive | Repository of human genetic variants and their relationships to phenotype (disease). |

| gnomAD [33] | Population Database | Catalog of human genetic variation from a large population, used to calibrate variant constraint. |

| AlphaFold DB [34] | Protein Structure DB | Provides predicted 3D structures for proteins, used to generate structural features for variants. |

| CCLE & TCGA [37] | Cancer Datasets | Provide genomic and transcriptomic data for cancer model systems and tumors. |

| DNA Language Models (e.g., HyenaDNA [36], DNABERT [32]) | Computational Tool | Generates numerical embeddings (representations) of DNA sequences for model input. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for GNN-based Variant Interpretation

| Item | Function | Example Tools / Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Graph Database | Serves as the scaffold for integrating heterogeneous biological data. | Custom-built from databases like Hetionet; typically includes nodes for Protein, Disease, Phenotype, etc. [32]. |

| Variant Effect Predictor | Annotates and predicts the functional consequences of genetic variants. | LOFTEE, VEP (Variant Effect Predictor) [36]. |

| Pathogenicity Scoring Models | Provides pre-computed features or benchmark comparisons for variant deleteriousness. | EVE, ESM-1v, AlphaMissense, popEVE [33] [34]. |

| Graph Neural Network Framework | Provides the software environment to build, train, and test GNN models. | PyTorch Geometric, Deep Graph Library (DGL). GATv2Conv is used for directed graphs with edge attributes [37]. |

| DNA Language Model | Converts raw nucleotide sequences into numerical embeddings that capture genomic context. | HyenaDNA, DNABERT, Nucleotide Transformer [32] [36]. |

Knowledge Graph Structure Diagram

Leveraging AlphaFold2 and ESM Models for Structural Feature Extraction

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between AlphaFold2 and ESMFold in their approach to structure prediction?

A1: The core difference lies in their use of evolutionary information. AlphaFold2 relies heavily on Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) to find homologous sequences, which requires querying large biological databases and can be computationally intensive [38]. In contrast, ESMFold is a single-sequence method that uses a pre-trained protein language model (ESM-2) to infer evolutionary patterns directly from the primary sequence, making it a standalone and much faster tool that does not require external database searches [39].

Q2: My AlphaFold2 run failed with an error: "Could not find HHsearch database /data/pdb70". What does this mean and how can I resolve it?

A2: This error indicates a missing or incorrectly configured homology detection database, which AlphaFold2 requires for its template-based modeling step [40]. To resolve this:

- Check Database Installation: Ensure all necessary databases (including pdb70) have been fully downloaded and are in the correct directory path specified in your AlphaFold2 installation.

- Use a Managed Service: Consider using a managed platform like the Galaxy server, which offers a pre-configured AlphaFold2 environment with all dependencies already installed [40].

- Verify File Permissions: Confirm that the user running AlphaFold2 has read permissions for the database files.

Q3: For predicting the impact of a missense variant on protein structure, should I use AlphaFold2 or AlphaMissense?

A3: These tools have distinct purposes. AlphaFold2 is designed to predict the 3D structure of a protein from its sequence [38]. To assess a variant, you would need to run it twice (for the wild-type and mutant sequences) and compare the outputs. AlphaMissense, built on AlphaFold's architecture, is a specialized tool that directly predicts the pathogenicity of missense variants by analyzing sequence and evolutionary context, providing a simple pathogenicity score [41]. For high-throughput variant screening, AlphaMissense is more efficient. However, for detailed, atomistic insight into how a specific variant alters the structure, running AlphaFold2 remains valuable.

Q4: The predicted structure for my protein of interest has low confidence scores (pLDDT) in a specific loop region. How should I interpret this?

A4: Low pLDDT scores (typically below 70) indicate regions where the model is less reliable. These often correspond to intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) or flexible loops that do not have a single, fixed conformation in solution [38]. In the context of missense variants, you should:

- Interpret with Caution: Be wary of over-interpreting structural changes due to mutations in these low-confidence regions.

- Use as a Hypothesis: The disordered nature itself can be biologically significant. The prediction can serve as a starting hypothesis, but these regions may require experimental validation.

Q5: Can I use ESMFold to predict multiple conformations or alternative folds for a protein?

A5: Current versions of ESMFold, like AlphaFold2, are primarily designed to predict a single, static protein structure [42]. They often struggle with proteins that have alternative conformations or are known as "metamorphic" proteins that can switch between different folds [42]. This is a known limitation of these AI-based prediction methods, and predicting the full conformational landscape of a protein remains an active area of research.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Low Confidence Predictions in AlphaFold2/ESMFold

Problem: A significant portion of your predicted model, or an entire domain, has low confidence metrics (pLDDT in AlphaFold2).

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Step 1: Verify the Input Sequence.

Step 2: Analyze the MSA (AlphaFold2 Specific).

- Low confidence often correlates with a shallow or poor-quality Multiple Sequence Alignment. Check the depth and diversity of the MSA generated by AlphaFold2. A lack of evolutionary homologs makes structure prediction more difficult [38].

Step 3: Cross-validate with ESMFold.

- Run the same sequence through ESMFold. As it uses a different methodology, it can serve as an independent check. Consistent low-confidence regions across both methods strongly suggest intrinsic disorder or a lack of evolutionary constraints in that area [39].

Step 4: Interpret Biologically.

- Map the low-confidence regions against known protein domains and functional annotations. They may be flexible linkers or disordered regions that are functionally important despite lacking a fixed structure.

Issue 2: AlphaMissense Misclassifies a Known Benign Variant as Pathogenic

Problem: When classifying missense variants for your gene of interest, AlphaMissense produces a high pathogenicity score for a variant that has been experimentally confirmed to be benign.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Step 1: Understand the Limitation.

- This is a documented limitation. AlphaMissense can conflate a variant's effect on protein function with its relevance to disease. It may correctly predict that a variant is damaging to a protein's biophysical properties, but that change may not be the mechanism of disease for that specific gene [41].

Step 2: Conduct Structural Analysis with AlphaFold2.

- Use AlphaFold2 to model the wild-type and mutant protein structures.

- Compare the two models to see if the variant causes significant destabilization, disrupts a key active site, or interferes with critical protein-protein interactions. This provides mechanistic context beyond a simple pathogenicity score.

Step 3: Consult Multiple Predictors and Experimental Data.

- Do not rely on AlphaMissense alone. Aggregate predictions from other state-of-the-art supervised and unsupervised tools [41].

- Prioritize evidence from high-throughput experimental assays (MAVEs) if available for your gene, but be aware that they can sometimes be discordant with clinical labels [41].

Final Recommendation: As concluded in recent research, "AlphaMissense cannot replace wet lab studies as the rate of erroneous predictions is relatively high" [41]. Use it as a powerful prioritization tool, not a final arbiter.

Comparative Data for Tool Selection

The table below summarizes the key quantitative and technical differences between AlphaFold2, ESMFold, and AlphaMissense to guide your experimental planning.

Table 1: Comparison of AlphaFold2, ESMFold, and AlphaMissense

| Feature | AlphaFold2 | ESMFold | AlphaMissense |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | 3D Protein Structure Prediction [38] | 3D Protein Structure Prediction [39] | Missense Variant Pathogenicity Scoring [41] |

| Core Methodology | MSA-based & Physical Geometry [38] | Single-sequence Protein Language Model [39] | Unsupervised Deep Learning (based on AlphaFold) [41] |

| Key Input | Amino Acid Sequence (for MSA generation) [38] | Amino Acid Sequence (single) [39] | Amino Acid Sequence & Variant Position [41] |

| Key Output | 3D Atomic Coordinates, pLDDT Confidence Metric [38] | 3D Atomic Coordinates [39] | Pathogenicity Score (0-1) [41] |

| Relative Speed | Slow (hours/days, due to MSA) [39] | Fast (order of magnitude faster than AlphaFold2) [39] | Very Fast (for variant scoring) |

| Recommended Application | High-accuracy static structures; detailed mutant analysis | High-throughput screening of metagenomic proteins; quick structural overview [39] | Prioritizing pathogenic variants in large-scale genetic studies [41] |

Table 2: ESM Model Family Overview

| Model | Parameters | Key Capability | Context Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 | 650M to 15B [39] | General protein language model, base for ESMFold [39] | 1026 [39] |

| ESMFold | 8M (folding head) [39] | End-to-end atomic structure prediction [39] | 1026 [39] |

| ESM Cambrian | 300M, 600M, 6B [45] | Next-generation representation learning, outperforms ESM-2 [45] | 2048 (after training) [45] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comparative Structural Analysis of a Missense Variant using AlphaFold2

Objective: To generate and compare the 3D structures of wild-type and mutant proteins to hypothesize the molecular mechanism of a missense variant.

Materials:

- Wild-type protein sequence in FASTA format.

- Mutant protein sequence (simulated by introducing the single amino acid change into the wild-type FASTA).

- Computing environment with AlphaFold2 installed and configured.

Methodology:

- Input Preparation:

- Create two separate FASTA files.

- Wild-type:

>Protein_X_WT [organism=Homo sapiens] - Mutant:

>Protein_X_MUT [organism=Homo sapiens] - Ensure the sequence is in valid FASTA format, with no line breaks in the header [46].

Structure Prediction:

- Run AlphaFold2 independently for both the wild-type and mutant FASTA files. This process involves MSA creation, template searching, and structure generation via the Evoformer and structure module [38].

- The output will be PDB files for each and a per-residue confidence metric (pLDDT).

Structural Comparison & Analysis:

- Superimposition: Load both PDB files into molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, ChimeraX) and superimpose the models based on conserved regions.

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD): Calculate the global and local RMSD to quantify structural differences. AlphaFold2 demonstrated a median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å in CASP14 [38].

- Visual Inspection: Manually inspect the mutation site for changes in:

- Side-chain conformation and contacts.

- Local backbone geometry.

- Disruption of hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, or hydrophobic cores.

- Obstruction of functional sites (e.g., active sites, binding pockets).

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Variant Prioritization using AlphaMissense and ESMFold

Objective: To rapidly screen a list of missense variants from a genetic study to prioritize candidates for further experimental validation.

Materials:

- A list of missense variants (e.g., from whole-exome sequencing) with their gene names and amino acid changes.

- Access to the AlphaMissense database or model.

- Computing environment capable of running ESMFold.

Methodology:

- Pathogenicity Scoring:

- Query the pre-computed AlphaMissense database for your variants to obtain pathogenicity scores.

- Apply the recommended threshold (score > 0.56) to flag likely pathogenic variants [41].

Structural Context Validation:

- For the shortlisted high-scoring variants, run ESMFold for the corresponding wild-type protein sequence to quickly obtain a structural model.

- Note: ESMFold's speed allows you to do this for dozens to hundreds of proteins in a practical timeframe [39].

Integrative Analysis:

- Map the variant position onto the ESMFold-predicted structure.

- Assess the structural context: Is the residue buried in the core, exposed on the surface, or part of a known functional motif? This step helps to distinguish variants that are likely to be destabilizing from those that might have more subtle functional effects.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for classifying pathogenic missense variants using the tools discussed in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| UniProt Knowledgebase | Comprehensive resource for protein sequences and functional information. | Source of canonical wild-type protein sequences for input into prediction models [45]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins. | Used for validation of computational models and for template-based modeling in AlphaFold2 [47]. |

| FASTA Format File | Standard text-based format for representing nucleotide or amino acid sequences. | The required input format for all tools discussed (AlphaFold2, ESMFold). The header must start with ">" [46] [43]. |

| AlphaFold2 Database | Pre-computed protein structure predictions for the human proteome and other key organisms. | Allows researchers to download predicted structures without running the model, saving computational time. |

| AlphaMissense Database | Pre-computed pathogenicity scores for a vast number of possible human missense variants. | Enables instant lookup of variant scores for prioritization without running the model locally [41]. |

| ESM-2 / ESM Cambrian Models | Pre-trained protein language models available via Hugging Face Transformers or EvolutionaryScale. | Provides the foundational understanding of protein sequences used by ESMFold; can be fine-tuned for specific tasks [39] [45]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using a knowledge graph over traditional databases for variant pathogenicity prediction? Knowledge graphs (KGs) integrate disparate biomedical data into a unified network, enabling the discovery of complex, multi-hop relationships that are not apparent in isolated databases [48] [49]. They provide a semantically rich structure that captures diverse entity types (e.g., genes, diseases, drugs, phenotypes) and their relationships, offering a more holistic context for interpreting variants [50] [49]. Crucially, path-based reasoning on KGs can generate transparent and biologically meaningful explanations for predictions, moving beyond the "black-box" nature of some complex models [48] [51].

Q2: My model for predicting pathogenic gene interactions lacks interpretability. How can a knowledge graph help? You can employ a path-based approach, such as the ARBOCK framework, which mines frequently observed connection patterns (metapaths) between known pathogenic gene pairs in a KG [48] [52]. These patterns are used to train an interpretable decision set model—a set of IF-THEN rules. When a new gene pair is predicted to be pathogenic, the model can provide the specific subgraph (the entities and relationships) that led to the conclusion, offering a clear, visual explanation grounded in biological knowledge [48].

Q3: How can I make pathogenicity predictions disease-specific instead of general? To achieve disease-specific prediction, structure your knowledge graph to include clear connections between variants and specific diseases. Then, you can train a classifier, such as a graph neural network, to essentially predict edges between variant and disease nodes [53]. This approach allows the model to learn the contextual patterns of pathogenicity unique to a particular disease, rather than relying on a single, generalized threshold [53].

Q4: What are some common data integration challenges when building a biomedical knowledge graph? A major challenge is disease entity resolution, as diseases are represented differently across various ontologies (e.g., MONDO, ICD, Orphanet) and clinical guidelines [49]. Harmonizing these into a consistent schema is critical. Furthermore, integrating omics data with ontological knowledge requires robust ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) pipelines and often the development of custom ontologies, such as a chromosomal location ontology, to bridge genomic features with broader biomedical concepts [54] [49].

Q5: How can I handle the "black-box" nature of deep learning models for variant interpretation? Implement an Explainable AI (XAI) framework that uses a knowledge graph as its knowledge base [51]. After a deep learning model makes a prediction, the KG can be used to generate human-readable explanations. This involves translating the important nodes and paths from the graph that contributed to the prediction into textual explanations that align with how clinicians investigate variants, for example, by referencing guidelines like those from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [51].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Predictive Performance on Novel Gene Pairs

Problem: Your KG model fails to identify novel pathogenic gene interactions outside of its training data.

Solution:

- Expand KG Connectivity: Ensure your KG integrates diverse and complementary biological networks. A gene-centric KG like BOCK showed that while individual networks (e.g., protein-protein interactions, co-expression) only partially connect known pathogenic pairs, their integration allows paths of lengths ≤3 to connect all pairs [48]. Incorporate networks such as:

- Leverage Multi-Hop Paths: Do not restrict your model to direct connections. Use a path traversal algorithm with a cutoff of 3 or 4 to capture long-range, indirect relationships between entities [48].

- Incorporate Pre-trained Embeddings: Enhance node features by integrating embeddings from biomedical language models (e.g., BioBERT) or genomic foundation models (e.g., HyenaDNA, Nucleotide Transformer) to provide rich, contextual information directly from textual descriptions or genomic sequences [53].

Issue 2: Inability to Generate Clinically Actionable Explanations

Problem: The model's predictions lack transparent explanations that clinicians can understand and trust.

Solution:

- Adopt a Rule-Based Model: Use association rule learning on the metapaths within your KG. The ARBOCK method generates a decision set of rules, where each rule is a specific pattern of connections frequently found in pathogenic cases [48] [52].

- Generate Instance-Specific Subgraphs: For every positive prediction, extract and visualize the exact subgraph of the KG that connects the gene pair, highlighting the specific biological entities and relationships that led to the conclusion [48].

- Align Explanations with Clinical Guidelines: Map the KG-derived explanations to established clinical frameworks. The XAI approach in [51] defines "X-Rules" that convert high-contribution nodes in the graph into text, ensuring the output references trusted sources like ClinVar and follows the logic of guidelines like those from the ACMG.

Issue 3: KG Fails to Capture Disease-Specific Variant Effects

Problem: Your pathogenicity predictions are not sensitive to the disease context.

Solution:

- Refine Graph Structure: Explicitly connect variants to their associated diseases. This can be done by linking variant nodes to disease nodes using edges from curated sources like ClinVar [53] [50].

- Implement a Disease-Specific Classifier: Train a two-stage model where a Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN) first encodes the complex relationships in the KG, and a subsequent neural network classifier predicts the "variant-causes-disease" edge [53]. This forces the model to learn in the context of a specific disease.

Problem: The process of merging different databases, ontologies, and omics data into a coherent KG schema is error-prone and inefficient.

Solution:

- Use a Foundational Scaffold: Build your KG on top of a unified base ontology like the Unified Biomedical Knowledge Graph (UBKG) or UMLS, which provides a pre-integrated framework for hundreds of biomedical ontologies [54] [49].

- Develop Modular Ingestion Protocols: Follow the practice of frameworks like Petagraph, which uses modular protocols to add new omics datasets to the UBKG base. This allows for consistent and reproducible integration of new data sources [54].

- Create Hub Nodes: For core entities like genes and variants, create central hub nodes that link to their corresponding entries across all integrated databases. This simplifies data access and cross-referencing [51].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Disease-Specific Pathogenicity Predictor Using a GCNN

Objective: To predict whether a missense variant is pathogenic for a specific disease using a graph neural network.

Methodology:

- Knowledge Graph Preparation:

- Obtain a base KG (e.g., from resources like PrimeKG [49] or build your own integrating genes, proteins, diseases, drugs, and phenotypes).

- Enrich the graph by splitting protein nodes into separate gene and protein nodes, connecting them with a

codes_foredge [53]. - Add variant nodes from ClinVar and link each variant to its corresponding gene with a

located_inedge. Connect pathogenic variants to their associated disease nodes with acausesedge [53].

- Feature Generation:

- Node Features: Generate initial feature vectors for all nodes using a biomedical language model like BioBERT. Use textual descriptions of the entities (e.g., disease summaries, gene names) as input [53].

- Variant Features: Use DNA language models (e.g., HyenaDNA, Nucleotide Transformer) to generate embeddings for variant nodes based on the genomic sequence surrounding the variant locus [53].

- Model Training:

- Implement a two-stage architecture:

- Stage 1 (Graph Encoding): A Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN) takes the KG with its node features and learns to generate dense, low-dimensional representations (embeddings) for every node, capturing their topological context [53].

- Stage 2 (Classification): A neural network classifier takes the embeddings of a variant node and a disease node and predicts the probability of a

causesedge existing between them [53].

- Train the model using known variant-disease associations from ClinVar as positive examples and benign variants as negative examples.

- Implement a two-stage architecture:

Protocol 2: Implementing an Interpretable Rule-Based Predictor for Gene Interactions

Objective: To predict pathogenic gene-gene interactions with explainable rules derived from knowledge graph paths.

Methodology:

- Path Extraction:

- From your KG (e.g., BOCK [48]), traverse all paths up to a length of 3 that connect known pathogenic gene pairs from a database like OLIDA. Ignore paths that go directly through "Disease" or "OligogenicCombination" nodes to avoid data leakage [48] [52].

- For each path, abstract it into a metapath—a sequence of node and edge types (e.g., Gene–interactswith–Gene–participatesin–BiologicalProcess–participates_in–Gene).

- Rule Mining:

- Use association rule learning to identify frequently occurring metapath patterns in the set of pathogenic gene pairs [48].

- These patterns form the IF part of the rules (e.g.,

IF Gene_A and Gene_B are connected by metapath X).

- Model Building:

- Combine the discovered rules into a Decision Set classifier [48] [52]. This is an unordered collection of IF-THEN rules where a gene pair is predicted as pathogenic if it satisfies any of the rules.

- The model's explanation for a prediction is simply the specific rule (and the corresponding concrete subgraph in the KG) that was triggered.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Resources for Knowledge Graph-Based Variant Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Features/Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOCK [48] [52] | Knowledge Graph | Exploring disease-causing genetic interactions. | Integrates oligogenic disease data (OLIDA) with multi-scale biological networks; designed for interpretable rule mining. |

| PrimeKG [49] | Knowledge Graph | Precision medicine analyses across a wide range of diseases. | Covers 17,080 diseases with multi-modal relationships (proteins, pathways, phenotypes, drugs including off-label use). |

| Petagraph [54] | Knowledge Graph Framework | Large-scale, unifying framework for biomolecular data. | Built on UBKG; embeds omics data into an ontological scaffold; highly modular for custom use cases. |

| AIMedGraph [50] | Knowledge Graph | Precision medicine, focusing on variant-drug relationships. | Integrates genes, variants, diseases, drugs, and clinical trials with evidence-based pathogenicity and drug susceptibility. |

| IDDB Xtra [55] | Specialized Database & KG | Infertility disease mechanism research and variant interpretation. | Manually curated genes, variants, and phenotypes for infertility; includes a dedicated infertility knowledge graph. |