Optimizing Phylogenetic Comparative Methods: Advanced Strategies for Robust Evolutionary Inference in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) to enhance the reliability of evolutionary inferences in biomedical studies.

Optimizing Phylogenetic Comparative Methods: Advanced Strategies for Robust Evolutionary Inference in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) to enhance the reliability of evolutionary inferences in biomedical studies. It explores the foundational principles of phylogenetic non-independence and its critical implications for statistical analysis. The content covers advanced methodological applications, including phylogenetically informed prediction and robust regression techniques, alongside practical troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls like tree misspecification. Through validation frameworks and comparative analyses, it demonstrates how optimized PCMs can yield more accurate trait predictions and evolutionary reconstructions, ultimately supporting more robust hypothesis testing in genomics, trait evolution, and therapeutic development.

The Phylogenetic Framework: Why Evolutionary History Matters in Comparative Analysis

Phylogenetic non-independence is a fundamental statistical challenge in evolutionary biology that arises because species share evolutionary history to varying degrees, violating the assumption of data independence in standard statistical tests. This phenomenon, recognized in most biological traits under selection, occurs when closely related species resemble each other more than distantly related species due to their shared ancestry [1]. When analyzing trait data across species, ignoring this non-independence can lead to inflated Type I error rates, spurious correlations, and biased parameter estimates because standard statistical methods treat each species as an independent data point when they are evolutionarily connected [2] [1].

The core problem stems from descent with modification - the principle that trait values will be more similar in closely related species than in distantly related species because the variance of trait values is proportional to their evolutionary time of divergence [1]. This shared ancestry creates what is known as phylogenetic signal, which represents the degree to which phylogenetic relationships influence trait data [2]. Addressing this non-independence is particularly crucial when studying evolutionary rates, trait evolution, and adaptations across species [1].

Key Concepts and Terminology

What is Phylogenetic Non-Independence?

Phylogenetic non-independence refers to the statistical dependence among species' traits resulting from their shared evolutionary history. This dependence manifests as a covariance structure where the expected similarity between species decreases as their evolutionary distance increases [1]. When phylogenetic signal is present but ignored in analyses, the effective sample size is overestimated, leading to incorrect statistical inferences about evolutionary processes and trait relationships [2] [1].

Understanding Phylogenetic Signal

Phylogenetic signal quantifies the extent to which related species resemble each other, representing the proportion of variance in trait data across species that can be explained by phylogenetic relationships [1]. Two common metrics for measuring phylogenetic signal include:

- Pagel's λ: A scaling parameter that measures the phylogenetic dependence in comparative data, where λ = 0 indicates no phylogenetic signal (traits evolved independently) and λ = 1 follows a Brownian motion model of evolution [1] [3]

- Blomberg's K: A statistic that compares the observed phylogenetic signal to that expected under a Brownian motion model [1]

Research has demonstrated that not only biological traits but even evolutionary rates themselves contain phylogenetic signal, meaning that closely related species often evolve at similar rates [1].

Consequences of Ignoring Non-Independence

Failure to account for phylogenetic non-independence can severely impact research conclusions:

- Spurious correlations: Finding significant relationships between traits that are actually explained by shared ancestry rather than functional relationships [2]

- Inflated Type I errors: Falsely rejecting null hypotheses at rates much higher than the specified alpha level [2]

- Biased parameter estimates: Incorrectly estimating the strength and direction of evolutionary relationships [3]

- Misleading rate summaries: Creating distorted profiles of evolutionary rates through time that reflect phylogenetic structure rather than genuine evolutionary patterns [1]

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Phylogenetic Non-Independence

Problem: Uncertainty about whether phylogenetic non-independence affects your dataset

Diagnostic Steps:

- Test for phylogenetic signal using appropriate metrics (λ or K) in software such as phytools [4] or BayesTraits [1]

- Visualize trait distribution on the phylogeny to identify clade-specific patterns

- Compare model fits between phylogenetic and non-phylogenetic methods

- Check for rate heterogeneity across the tree, as this can indicate phylogenetic structure in evolutionary processes [1]

Interpretation: Significant phylogenetic signal (λ significantly greater than 0) indicates that phylogenetic non-independence must be accounted for in your analyses [1]. High phylogenetic signal at the tips of phylogenetic trees is common, with studies finding median λ values of 0.926 for mammalian body mass, 0.729 for bird beak shape, and 1.0 for amniote bite force [1].

Addressing Model Misspecification in PGLS

Problem: Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) models producing questionable results

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify phylogenetic tree accuracy - ensure your tree is well-resolved and reflects current phylogenetic understanding [3]

- Check trait distribution assumptions - PGLS assumes normally distributed trait data [3]

- Assess model specification - confirm that the phylogenetic covariance structure appropriately models your data [3]

- Consider alternative evolutionary models - Brownian motion may not always be the best fit for your data

- Validate with sensitivity analyses - test how robust your results are to different phylogenetic hypotheses

Solution Approaches:

- Use information criteria (AIC or BIC) for model selection [3]

- Implement multiple imputation or robust regression methods for missing data and outliers [3]

- Consider Bayesian approaches to incorporate uncertainty in phylogenetic estimates [3]

Handling Weak Phylogenetic Signal

Problem: Low or non-significant phylogenetic signal in your data

Guidance:

- Confirm measurement reliability - ensure trait data are accurately measured across species

- Check phylogenetic scale - phylogenetic signal depreciates in deeper time slices due to reduced statistical power [1]

- Consider methodological limitations - small sample sizes and low rate heterogeneity reduce power to detect phylogenetic signal [1]

- Evaluate evolutionary patterns - some traits genuinely evolve with little phylogenetic constraint

Recommendations: Even with weak phylogenetic signal, it is safest to assume some degree of phylogenetic non-independence and use appropriate comparative methods, as the consequences of ignoring phylogenetic signal are more severe than accounting for it when unnecessary [1].

FAQ

What is phylogenetic non-independence and why does it matter?

Phylogenetic non-independence is the statistical dependence among species due to their shared evolutionary history. It matters because standard statistical tests assume data independence, and violating this assumption leads to inflated Type I error rates, spurious correlations, and biased parameter estimates. This can result in incorrect biological conclusions about evolutionary processes and trait relationships [2] [1].

How can I test for phylogenetic signal in my data?

You can test for phylogenetic signal using metrics such as Pagel's λ or Blomberg's K implemented in various software packages. In R, the phytools package provides functions for estimating phylogenetic signal [4]. The general approach involves comparing the observed trait distribution on the phylogeny to what would be expected under a null model of trait evolution (often Brownian motion), with significance testing using likelihood ratio tests or permutation approaches [1].

When should I use PGLS instead of traditional regression?

Use Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) instead of traditional regression when:

- You have trait data from multiple species related through a phylogeny

- Tests indicate significant phylogenetic signal in your data

- You want to account for evolutionary relationships while testing hypotheses about trait correlations

- You need accurate parameter estimates and statistical inferences about evolutionary processes [3]

PGLS incorporates a phylogenetic covariance matrix into the regression model, explicitly modeling the non-independence due to shared ancestry [3].

What are the limitations of phylogenetic comparative methods?

Key limitations include:

- Dependence on accurate phylogenetic trees [3]

- Assumptions about evolutionary models that may not match biological reality [3]

- Computational intensity for large datasets [3] [5]

- Sensitivity to model misspecification [3]

- Difficulty handling missing data [3]

- Challenges with discrete traits and rate heterogeneity [1]

How can I visualize phylogenetic non-independence?

You can visualize phylogenetic non-independence using:

- Trait mapping on phylogenies (traitgram plots)

- Phylogenetic scatterplots and correlation plots

- Visualization tools in R packages like phytools [4]

- Dependence structures illustrated through covariance matrices

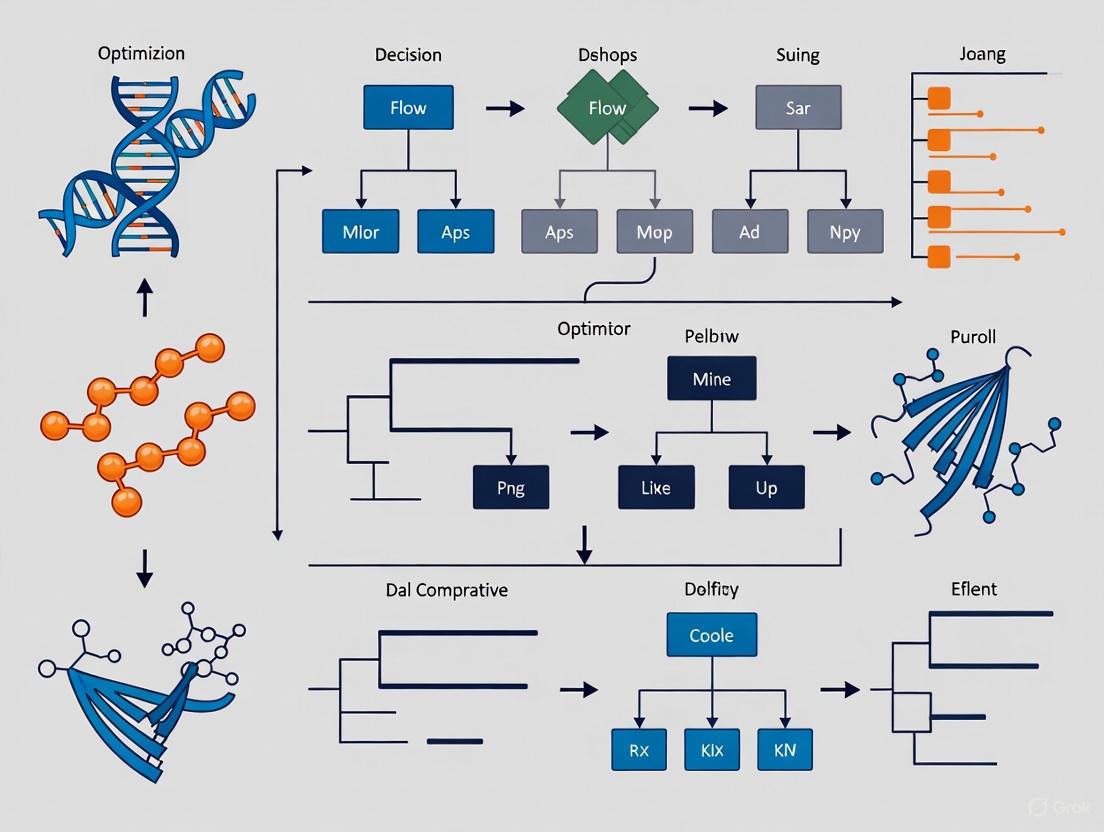

The following diagram illustrates how phylogenetic relationships create statistical non-independence:

Phylogenetic Non-Independence Cycle

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Testing for Phylogenetic Signal in Trait Data

Objective: Quantify the degree of phylogenetic signal in a continuous trait using Pagel's λ.

Materials:

- Phylogenetic tree of study species

- Trait measurements for each species

- R statistical environment with phytools package [4]

Procedure:

- Prepare data: Ensure trait data are properly matched to phylogeny tips

- Load packages: Install and load phytools in R [4]

- Fit phylogenetic signal model: Use appropriate functions (e.g.,

phylosigin phytools) to estimate λ - Test significance: Compare likelihood of model with estimated λ versus λ = 0 using likelihood ratio test

- Interpret results: λ significantly greater than 0 indicates phylogenetic signal

Troubleshooting:

- If phylogenetic signal is non-significant, verify data quality and phylogenetic scale

- For large trees, consider computational shortcuts or Bayesian approaches

- Ensure branch lengths are appropriate for the evolutionary model

Protocol 2: Implementing PGLS Analysis

Objective: Conduct Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares regression to test trait correlations while accounting for phylogenetic non-independence.

Materials:

- Time-calibrated phylogenetic tree

- Trait dataset for dependent and independent variables

- R environment with ape, nlme, and phytools packages [4]

Procedure:

- Data preparation: Check for missing data and normalize traits if necessary

- Model specification: Define the PGLS model structure with phylogenetic covariance matrix

- Parameter estimation: Use maximum likelihood or restricted maximum likelihood to fit model

- Model validation: Check residuals for phylogenetic structure and normality

- Result interpretation: Examine coefficients, confidence intervals, and p-values

Validation:

- Compare AIC values with non-phylogenetic models

- Conduct sensitivity analyses with alternative phylogenies

- Check for influential species using phylogenetic diagnostics

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Software and Tools

Table: Key Computational Tools for Addressing Phylogenetic Non-Independence

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| phytools [4] | Comprehensive phylogenetic comparative analysis | R package with hundreds of functions for trait evolution, diversification, and visualization |

| ape [4] | Phylogenetic tree manipulation and analysis | Core R package for reading, writing, and processing phylogenetic trees |

| BayesTraits [1] | Bayesian phylogenetic analysis | Software for estimating phylogenetic signal and testing evolutionary hypotheses |

| Dodonaphy [5] | Differentiable phylogenetics using hyperbolic embeddings | Advanced method for phylogenetic tree optimization in continuous space |

Analytical Frameworks

Table: Statistical Methods for Addressing Phylogenetic Non-Independence

| Method | Key Features | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| PGLS [3] | Extends GLS with phylogenetic covariance matrix | Testing trait correlations while accounting for phylogenetic relationships |

| Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts [2] | Uses differences between sister taxa | Analyzing trait evolution under Brownian motion model |

| Stochastic Character Mapping [4] | Maps character evolution on trees | Studying discrete trait evolution and ancestral state reconstruction |

| Variational Bayesian Phylogenetics [5] | Approximates tree distribution using probability | Capturing uncertainty in evolutionary relationships and tree topologies |

Workflow Visualization

Comprehensive PGLS Analysis Workflow

PGLS Implementation Process

Advanced Topics

Phylogenetic Signal in Evolutionary Rates

Recent research has revealed that not only biological traits but also evolutionary rates themselves exhibit phylogenetic signal. This means that closely related species tend to evolve at similar rates, creating an additional layer of phylogenetic non-independence that must be considered in comparative analyses [1].

Key Findings:

- Phylogenetic signal in rates is generally high and significant in younger time slices

- Signal depreciates in deeper time slices, but this reflects reduced statistical power rather than absence of signal

- Analyses of rates through time must account for phylogenetic non-independence to avoid misleading interpretations [1]

Emerging Methodological Advances

Hyperbolic embeddings and differentiable phylogenetics represent cutting-edge approaches to addressing phylogenetic non-independence. These methods:

- Represent phylogenetic trees in continuous space rather than as discrete entities

- Enable gradient-based optimization of tree structures using tools like soft neighbor-joining (soft-NJ)

- Facilitate more efficient exploration of tree space and evolutionary relationships [5]

Variational Bayesian methods provide another advanced framework for:

- Approximating the distribution of possible phylogenetic trees

- Capturing uncertainty in evolutionary relationships

- Optimizing variational parameters to improve tree estimates [5]

Addressing phylogenetic non-independence is not merely a statistical technicality but a fundamental requirement for valid evolutionary inference. The core principle recognizes that species are connected through shared ancestry, creating statistical dependencies that must be explicitly modeled in comparative analyses. By implementing appropriate phylogenetic comparative methods such as PGLS, researchers can draw more accurate conclusions about evolutionary processes, trait relationships, and adaptation patterns.

The field continues to advance with new computational methods and analytical frameworks, but the underlying principle remains: proper accounting for phylogenetic non-independence is essential for robust evolutionary inference. As research has demonstrated, this applies not only to biological traits but also to evolutionary rates themselves, creating complex dependencies that must be carefully considered in comparative analyses [1].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is phylogenetic pseudo-replication, and why is it a problem? Phylogenetic pseudo-replication occurs when species are treated as independent data points in statistical analysis despite sharing evolutionary history. This violates the core assumption of independence in standard statistical models (like standard linear regression), because closely related species often have similar traits due to common ancestry rather than independent evolution. Analyzing such non-independent data without accounting for phylogenetic relationships can inflate Type I error rates, leading to spurious conclusions about evolutionary relationships and trait correlations [2] [6].

Q2: How can I visually detect a strong phylogenetic signal in my trait data? A strong phylogenetic signal means that closely related species have more similar trait values than distantly related species. You can detect it visually by plotting your phylogenetic tree and mapping the trait values onto the tips.

- Methodology: After plotting your phylogeny, use a function to place dots or colored bars at the tree tips. The size or color of these markers should correspond to the value of the trait for each species [6].

- Interpretation: If you observe that large (or small) trait values cluster on specific clades or branches of the tree, this is a clear visual indicator of a strong phylogenetic signal. Conversely, if trait values appear randomly distributed across the tree, the phylogenetic signal is likely weak [6].

Q3: What are the main statistical methods to quantify phylogenetic signal? Pagel's λ (lambda) is a commonly used metric to quantify phylogenetic signal [6]. It scales the observed phylogenetic structure in the trait data against the structure expected under a Brownian motion model of evolution.

- Interpretation: A λ of 0 indicates no phylogenetic signal (traits evolved independently of phylogeny). A λ of 1 indicates that the trait has evolved exactly as expected under the Brownian motion model along the given tree structure [6].

- Calculation: This is typically implemented in R packages (e.g.,

ape,geiger) that use maximum likelihood to estimate the value of λ for your trait data and phylogeny [6].

Q4: My data shows a strong phylogenetic signal. What are my options for a proper analysis? When a phylogenetic signal is present, you should use phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) that explicitly incorporate the tree structure into your model. Two foundational approaches are:

- Phylogenetically Independent Contrasts (PIC): This method transforms the raw species data into statistically independent contrasts (differences between sister species or nodes). Standard statistical tests are then performed on these contrasts [6].

- Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS): This is a model-based approach that uses the phylogenetic tree to define a variance-covariance matrix for the error term in a generalized least squares model. PGLS can directly incorporate and test different evolutionary models, such as Brownian motion or Ornstein-Uhlenbeck processes [2] [6].

Q5: How do I choose between PIC and PGLS? While both methods account for phylogenetic non-independence, PGLS is generally more flexible and powerful. PIC is a specific case that is mathematically equivalent to a PGLS model under a Brownian motion assumption. PGLS allows you to fit and compare different evolutionary models (e.g., by estimating Pagel's λ) and is often easier to extend to complex models with multiple predictors [2] [6].

Q6: What are common pitfalls in phylogenetic tree construction, and how can I avoid them? Two major pitfalls during the tree construction phase can undermine your entire comparative analysis [2]:

- Model Misspecification: Using an inappropriate substitution or coalescent model for your genetic data can lead to an inaccurate tree.

- Solution: Use model selection techniques like likelihood ratio tests or Bayesian information criterion to identify the most suitable model for your data type (nucleotide, amino acid, etc.) [2].

- Insufficient Data: Using too little genetic data can result in a poorly supported tree with low confidence in branch lengths and topology.

- Solution: Use robust methods like Bayesian Inference, which can provide posterior probabilities for branch support, and aim for sufficient genomic coverage [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Inconsistent results between phylogenetic and non-phylogenetic methods.

- Problem: You get a statistically significant correlation using a standard linear model (TIPS - Tips Are Species) but the significance disappears or weakens when using PIC or PGLS.

- Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of phylogenetic pseudo-replication. The initial "significant" correlation was likely driven by a few closely related species sharing similar traits through common descent, not a general evolutionary relationship.

- Solution: Trust the phylogenetic method. The PIC/PGLS result is the more reliable estimate of the evolutionary relationship between your traits. Report these results and note that the TIPS analysis was likely misleading [6].

Issue: Low support values or high uncertainty in your phylogenetic tree.

- Problem: Your comparative analysis (e.g., PGLS) yields different results when using different plausible trees (e.g., maximum likelihood vs. Bayesian consensus).

- Diagnosis: Phylogenetic uncertainty is being propagated into your comparative analysis, making the results unstable.

- Solution: Incorporate phylogenetic uncertainty directly into your analysis. Instead of relying on a single tree, use Bayesian methods to run your comparative model across a posterior distribution of trees (a "tree sample"). This allows you to report a confidence interval for your parameter estimates (e.g., regression slopes) that accounts for uncertainty in the tree topology and branch lengths [2].

Issue: The PGLS model with a fitted λ does not converge or produces errors.

- Problem: The numerical optimization algorithm fails to find a maximum likelihood solution for the model parameters.

- Diagnosis: This can be caused by poorly scaled data, overly complex models, or a very weak phylogenetic signal.

- Solution:

- Check and scale your data: Standardize your continuous variables (e.g., convert to Z-scores).

- Simplify the model: Start with a simpler evolutionary model (e.g., Brownian motion) before trying more complex ones.

- Verify the tree and data: Ensure the species names in your trait data perfectly match those in the tree and that there are no missing data points.

Data Presentation and Protocols

Quantitative Comparison of Analytical Methods

The table below summarizes a typical comparison between non-phylogenetic and phylogenetic methods using the Rockfish dataset, analyzing the relationship between log(maximum length) and log(maximum age) [6].

Table 1: Comparison of TIPS, PIC, and PGLS Results for Trait Correlation

| Method | Model Assumption | Slope Estimate (β) | Correlation (r) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIPS | Traits are independent | ~1.19 | - | Prone to inflated Type I error; ignores phylogeny [6]. |

| PIC | Brownian Motion | ~1.19 | 0.625 | Accounts for phylogeny; mathematically equivalent to a specific PGLS model [6]. |

| PGLS (λ=1) | Brownian Motion | ~1.19 | - | Equivalent to PIC analysis [6]. |

| PGLS (λ=ML) | Data-driven evolution | - | - | Pagel's λ estimated at 0.583; provides the best statistical fit for this data [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis

This protocol outlines the key steps for a robust phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) analysis in R.

1. Data and Tree Preparation

- Input: A phylogenetic tree (e.g., in Newick format) and a corresponding trait dataset [6].

- Software: Use R packages such as

ape,geiger, andnlme/phylolm. - Action:

- Read the tree file using

read.tree()orread.nexus(). - Read the trait data from your CSV file.

- Crucially, check that the species names in the trait data perfectly match the tip labels in the tree and are in the same order. Use the

name.check()function from thegeigerpackage.

- Read the tree file using

2. Initial Exploration and Visualization

- Action:

3. Model Fitting and Selection

- Action:

- Fit a PGLS model. Use the

gls()function in thenlmepackage with a correlation structure defined by the phylogenetic tree (e.g.,corBrownianorcorPagel). - Find the best evolutionary model. Compare models with different fixed values of λ (e.g., 0 and 1) and a model where λ is estimated. Use Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to select the model with the best fit [6].

- Diagnostics. Check the model diagnostics (e.g., residual plots) to ensure assumptions are met. You can also transform the data using the phylogenetic correlation matrix to check for outliers and non-linear relationships [6].

- Fit a PGLS model. Use the

4. Interpretation and Reporting

- Action:

- Report the parameter estimates (slopes, intercepts) and their confidence intervals from the best-fitting model.

- Clearly state the estimated value of λ or other model parameters.

- Discuss your findings in the context of the phylogenetic relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Sequence Data | Raw molecular data (e.g., from mitochondrial or nuclear genes) used as the basis for inferring evolutionary relationships [6]. |

| Phylogenetic Tree | The hypothesized evolutionary relationships among species, represented as a branching diagram. This is the core structure for all comparative analyses [2] [6]. |

| Trait Dataset | A table of measured phenotypic (e.g., body size, lifespan) or ecological (e.g., habitat depth) characteristics for the species in the tree [6]. |

| R Statistical Environment | A free, open-source software environment for statistical computing and graphics. It is the primary platform for conducting PCMs [6]. |

ape R Package |

A core R package for reading, writing, plotting, and analyzing phylogenetic trees. Provides functions for PIC and basic models [6]. |

nlme & phylolm R Packages |

R packages that provide functions (e.g., gls) to fit PGLS models with various phylogenetic correlation structures [6]. |

| Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) | An online tool for the visualization, annotation, and management of phylogenetic trees. Useful for exploring and creating publication-quality figures [7]. |

Methodological Workflows and Relationships

Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis Workflow

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for deciding on and applying phylogenetic comparative methods.

Phylogenetic Tree Construction Process

This diagram visualizes the key steps and choices involved in building a phylogenetic tree, which forms the foundation for any comparative analysis.

Phylogenetic Comparative Methods (PCMs) and Phylogenetic Reconstruction represent two distinct stages in evolutionary analysis. PCMs use established evolutionary relationships (phylogenies) to test hypotheses about trait evolution, diversification, and adaptation across species [8]. In contrast, phylogenetic reconstruction focuses on inferring the evolutionary relationships and branching patterns themselves, typically from molecular or morphological data [2] [9].

This technical guide clarifies this distinction through troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and experimental protocols to optimize your phylogenetic comparative research.

Key Distinctions at a Glance

Table 1: Core Differences Between Phylogenetic Reconstruction and Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Aspect | Phylogenetic Reconstruction | Phylogenetic Comparative Methods (PCMs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Infer evolutionary relationships and branching order (the tree itself) [9]. | Analyze trait evolution and test hypotheses using a pre-established tree [8]. |

| Primary Input | Molecular sequences (DNA, RNA, amino acids) or discrete morphological characters [2] [9]. | A phylogenetic tree + data for traits of interest (e.g., body size, habitat) [8]. |

| Primary Output | A phylogenetic tree showing hypothesized relationships [2]. | Statistical insights into evolutionary processes (e.g., correlations, ancestral states, diversification rates) [8] [10]. |

| Common Methods | Maximum Likelihood, Bayesian Inference, Maximum Parsimony [2]. | Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS), Independent Contrasts, Ancestral State Reconstruction [8] [10]. |

| Role of the Tree | The tree is the unknown being estimated. | The tree is a known input used to account for non-independence due to shared ancestry [8] [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Confusing Data Inputs for Reconstruction vs. PCMs

Problem: A researcher attempts to use a continuous trait measurement (e.g., genome size) as input data to build a phylogenetic tree from scratch.

Diagnosis: This confuses the input for phylogenetic reconstruction (typically sequence data) with the input for PCMs (trait data analyzed on a pre-existing tree).

Solution:

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Use aligned molecular sequence data (e.g., DNA, proteins) or discrete morphological characters to infer the tree topology using methods like Maximum Likelihood or Bayesian Inference [2].

- PCMs: First, obtain a robust phylogenetic tree from prior reconstruction or a published source. Then, use this tree alongside your trait data (continuous or discrete) in a PCM to test your evolutionary hypothesis [8] [10].

Issue 2: Misinterpreting Phylogenetic Signal

Problem: A strong relationship between two traits is found using standard statistics, but the significance disappears when using a PCM like PGLS.

Diagnosis: The initial analysis did not account for phylogenetic non-independence. Closely related species are similar simply due to shared ancestry, creating spurious correlations if not controlled for [10]. The PCM correctly identifies that there is no evidence for the relationship evolving independently across the tree.

Solution: Always use PCMs for cross-species analyses. A significant result from a PCM provides much stronger evidence for a functional or adaptive relationship, as it demonstrates the pattern holds after accounting for shared history [8] [10].

Issue 3: Model Misspecification in Multivariate Analyses

Problem: When analyzing multiple traits simultaneously, statistical conclusions change drastically after a simple rotation of the data, such as a Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Diagnosis: This indicates the use of an inappropriate multivariate PCM that is sensitive to data orientation. Some methods assume traits evolve independently, which is often violated [11].

Solution: Use multivariate PCMs that are algebraically robust and insensitive to data orientation. Avoid methods that summarize patterns across traits separately or use pairwise composite likelihood, as they have high model misspecification rates [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why can't I consider different species as independent data points in my analysis?

Species share portions of their evolutionary history due to common descent. This means two closely related species are likely to be similar not because of independent evolution but because they inherited traits from a recent common ancestor. Using standard statistical tests that assume independence inflates the effective sample size and can lead to spurious conclusions (Type I errors) [8] [10]. PCMs explicitly incorporate the phylogenetic tree to correct for this non-independence.

FAQ 2: My trait evolves very rapidly. Do I still need to account for phylogeny?

Yes. Even for rapidly evolving traits, other variables in your analysis (known or unknown) might still be correlated with the phylogeny. Using phylogenetic comparative methods is a conservative approach that controls for potential spurious results arising from any phylogenetically structured variable, not just the one you are measuring [10].

FAQ 3: What is the most common PCM I should learn first?

Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) is one of the most widely used PCMs [8]. It is an extension of standard linear regression that incorporates the phylogenetic structure into the model's error term, allowing you to test for correlations between traits while accounting for evolutionary relationships [8] [10].

FAQ 4: I have a phylogeny with branch lengths measured in time (millions of years). Can I use it for all PCMs?

Most PCMs require an ultrametric tree, where all tips are aligned, and branch lengths are proportional to time. This is essential for analyses of trait evolution (e.g., under Brownian motion or Ornstein-Uhlenbeck models) and diversification [12]. If your tree has branch lengths in units of genetic change (e.g., substitutions/site), you may need to convert it to an ultrametric tree using appropriate software.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Workflow for a Basic Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis

This protocol outlines the steps to test for a correlation between two continuous traits using PGLS.

Objective: To test if genome size and body mass are correlated across a clade of mammals, controlling for shared evolutionary history.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Data Collection:

- Obtain a time-calibrated phylogenetic tree for your study species from a published source or database.

- Collect trait data (genome size, body mass) for the species in the tree from the literature.

Data Preparation:

- Ensure the species names in the trait dataset exactly match the tip labels on the tree.

- Prune the tree and trait data to include only species for which you have complete data.

Model Fitting with PGLS:

- Use the

pgls()function in the R packagecaperor thephylolm()function inphylolm[10]. - The model will be specified as:

Trait_Y ~ Trait_X, with the phylogenetic tree provided as a covariance matrix. - The analysis will estimate the regression slope and p-value, accounting for phylogeny.

- Use the

Interpretation:

- Examine the significance of the slope coefficient. A significant p-value indicates evidence for a correlation between the traits, independent of phylogeny.

The logical relationship and workflow between phylogenetic reconstruction and comparative methods is summarized in the following diagram.

Protocol 2: Implementing Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts

Objective: To calculate independent contrasts for a trait to be used in subsequent regression analysis, as originally proposed by Felsenstein [8].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Requirements: An ultrametric tree and continuous trait data for all tips.

- Calculation:

- Use the

pic()function in the R packageape[4]. - The function traverses the tree from tips to root, calculating standardized differences in trait values between each pair of sister nodes.

- Use the

- Output: A set of contrast values that are statistically independent and identically distributed, suitable for use in standard regression or correlation tests.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Software and Analytical Tools for Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment [4] | Software Platform | Core computing environment for statistical analysis and graphics. | Serves as the hub for installing and running specialized PCM packages. |

ape R Package [10] [4] |

Software Library | Reading, writing, and manipulating phylogenetic trees; basic comparative analyses. | Foundational package for phylogenetics in R; provides essential functions. |

phytools R Package [4] |

Software Library | Comprehensive toolkit for PCMs and phylogenetic visualization. | Extremely diverse functionality for trait evolution, ancestral state reconstruction, and plotting. |

caper R Package [10] |

Software Library | Implementing phylogenetic regression (PGLS) and independent contrasts. | User-friendly interface for common comparative analyses. |

MCMCglmm R Package [10] |

Software Library | Fitting phylogenetic mixed models using Bayesian inference. | Handles complex models with multiple fixed and random effects, including the phylogeny. |

| BayesTraits [10] | Standalone Software | Analyzing trait evolution using Bayesian methods. | Specialized for discrete and continuous trait analysis with a focus on correlated evolution. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My phylogenetic regression results seem biologically implausible. How can I verify if I've accounted for phylogenetic dependence correctly? A1: Biologically implausible results often indicate inadequate accounting for phylogenetic non-independence. First, test for phylogenetic signal in your residuals using Pagel's λ or Blomberg's K [8]. A significant signal suggests your model hasn't fully accounted for phylogenetic structure. Consider switching from Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts (PIC) to Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS), which provides more flexibility in modeling evolutionary processes and can directly test whether residuals show phylogenetic structure [8] [4].

Q2: I suspect the evolutionary rate of my trait of interest has varied across the tree. How can I test this?

A2: You can implement a multi-rate Brownian motion model using penalized-likelihood methods available in R packages like phytools [13]. This approach allows each branch to have a different evolutionary rate (σ²) while penalizing excessive rate variation between adjacent branches using a smoothing parameter (λ). Start by comparing a single-rate model to a multi-rate model using likelihood ratio tests, but beware that this method works best for exploratory analysis rather than testing specific a priori hypotheses [13].

Q3: When should I use Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts versus PGLS? A3: Use PIC when you want a simple, computationally efficient method that assumes a strict Brownian motion model of evolution [8]. PGLS is more appropriate when you need flexibility in evolutionary models (e.g., incorporating Ornstein-Uhlenbeck processes or Pagel's λ) or when analyzing multiple predictors [8]. PGLS also provides more straightforward interpretation of regression parameters and model diagnostics. For binary response variables, extend PGLS to phylogenetic generalized linear models [8].

Q4: How can I account for evolutionary lags when testing for trait correlations? A4: The Delayed-Response Phylogenetic Correlation method addresses this by matching corresponding changes in two traits while penalizing asynchronous responses [14]. This method weights trait pairs based on nodal or branch-length distance between changes, giving maximum weight to immediate (same-node) responses. It uses a weighted correlation coefficient across all character reconstructions, with significance testing via randomization of changes across the topology [14].

Troubleshooting Common Computational Issues

Table 1: Common Error Messages and Solutions in Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis

| Error Message | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Matrix is singular" or "Variance-covariance matrix is not positive definite" | Tips too recent for meaningful contrast calculation | Check tree root age; verify branch lengths; use picante or ape packages to check matrix properties [8] [4] |

| Contrasts with zero variance | Tips have identical values with short divergence | Check for data entry errors; consider pooling closely related species if biologically justified [8] |

| Model convergence failures in multi-rate models | Overparameterization or poor λ selection | Use model selection to optimize λ; try different starting values; simplify model structure [13] |

| Poor mixing in Bayesian comparative methods | Poor proposal mechanisms or priors | Adjust tuning parameters; run longer chains; check prior specifications [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Fitting and Comparing Multi-Rate Brownian Motion Models

This protocol tests whether evolutionary rates differ across a phylogeny using the multirateBM function in the phytools R package [13].

- Data Preparation: Format trait data as a vector with names matching tree tip labels. Ensure tree is ultrametric with appropriate branch lengths.

- Model Fitting: Fit models across a range of smoothing parameters (λ). Lower λ values penalize rate variation less, allowing more branch-specific rates.

- Model Selection: Compare models using information criteria (AIC, BIC) or cross-validation to select optimal λ.

- Rate Estimation: Extract branch-specific rate estimates from the best-fitting model.

- Visualization: Plot the tree with branches colored by their estimated evolutionary rates.

Key Parameters:

- λ (smoothing coefficient): Controls penalty on rate variation between edges

- σ²: Instantaneous variance of the Brownian process

- log(σ²): Evolutionary rate of rate variation under geometric Brownian motion

Protocol 2: Implementing Delayed-Response Phylogenetic Correlation

This method detects trait covariation while accounting for evolutionary lags [14].

- Character Mapping: Map both continuous characters onto the tree to generate data pairs.

- Pair Formation: Create trait pairs using both tree-down and tree-up approaches, matching corresponding changes in x and y traits.

- Weight Assignment: Apply weights to pairs based on nodal or branch-length distance between changes, penalizing delayed responses.

- Correlation Calculation: Compute weighted correlation coefficients across all character reconstructions.

- Significance Testing: Generate null distributions by randomly reallocating changes across the topology (Generalized Monte Carlo).

Validation: Test method performance using simulated datasets with known evolutionary relationships and lag structures [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| phytools [4] | Comprehensive phylogenetic analysis | Implements multi-rate BM, ancestral state reconstruction, trait evolution visualization | R package with 300+ functions for diverse comparative methods |

| ape [15] | Core phylogenetic operations | Tree manipulation, PIC implementation, variance-covariance matrix calculation | Foundational R package depended on by most comparative method packages |

| BEAST [15] | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Divergence time estimation, relaxed molecular clocks, demographic history | Bayesian MCMC framework with model flexibility |

| IQ-TREE [15] | Maximum likelihood phylogeny inference | Model selection, ultrafast bootstrapping, partition scheme finding | Efficient algorithm for large datasets with model testing |

| PAUP* | Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony | Maximum parsimony, distance matrix, maximum likelihood methods | Classic software with comprehensive tree-searching algorithms |

Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Phylogenetic Comparative Methods Decision Framework

Diagram 2: Multi-Rate Brownian Motion Estimation Process

Diagram 3: Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) Framework

Advanced PCMs in Action: From Theory to Practice in Genomic and Trait Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core advantage of phylogenetically informed prediction over standard predictive equations? Standard predictive equations treat each species as an independent data point, which can lead to inflated Type I error rates and spurious correlations because they ignore the shared evolutionary history among species. Phylogenetically informed prediction explicitly incorporates the phylogenetic tree to model the non-independence of data, leading to more statistically robust and biologically accurate predictions of trait evolution [8] [14].

2. My PGLS model failed to converge. What are the most common causes? Model non-convergence in Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) often stems from:

- An incorrectly specified evolutionary model: The assumed model of trait evolution (e.g., Brownian motion, Ornstein-Uhlenbeck) may be a poor fit for your data.

- Issues with the phylogenetic tree: Inaccurate branch lengths or tree topology can introduce error. Ensure branch lengths are meaningful (e.g., time, genetic divergence).

- Insufficient phylogenetic signal: If the trait has evolved with little regard to the phylogeny (low phylogenetic signal), the model may struggle to fit the phylogenetic structure [8] [4].

3. How do I handle a situation where one trait appears to evolve in response to another, but with a time lag (evolutionary lag)? The Delayed-Response Phylogenetic Correlation method is specifically designed for this. It tests for covariation between continuous characters while accounting for asynchronous responses by weighting data pairs based on the nodal or branch-length distance between changes in the two traits, penalizing responses that are far apart in the tree [14].

4. Which software is best for a researcher new to phylogenetic comparative methods?

The R environment is the standard. For beginners, the phytools package is highly recommended as it provides a vast ecosystem of hundreds of functions for trait evolution, diversification, and visualization, all within a unified framework [4]. The ape package is also a fundamental dependency for many of these analyses [4].

5. How can I visualize my phylogenetic tree along with the continuous trait data I am analyzing? The Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) is a powerful online platform for visualizing and annotating phylogenetic trees. It can display trees with over 50,000 leaves and allows you to map continuous trait data directly onto the tree using various visual styles like adjusting branch colors and widths [7]. The ETE Toolkit's online tree viewer is another option for simpler visualizations [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Statistical Power in Detecting Trait Correlations

Symptoms: Non-significant p-values for trait relationships even when a strong correlation is suspected biologically.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ignored evolutionary lags [14] | Test for delayed response using the Delayed-Response Phylogenetic Correlation method. | Implement the Delayed-Response method, which can detect correlations that standard methods miss by accounting for asynchronous evolution. |

| Incorrect evolutionary model [8] [4] | Fit multiple models of evolution (e.g., Brownian Motion, OU) and compare their fit to your data using AICc or likelihood ratio tests. | Use the best-fitting model for your analysis. Functions in phytools and geiger can help with this. |

| Weak phylogenetic signal in the traits [8] | Calculate Blomberg's K or Pagel's λ for your traits. A value near 0 indicates no signal. | If phylogenetic signal is very low, a non-phylogenetic method may be more appropriate, but this finding is itself biologically informative. |

Problem 2: Errors During Ancestral State Reconstruction

Symptoms: Unreasonable or highly uncertain estimates for ancestral character states; software returns an error.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme trait values at the tips influencing root estimation [8] | Plot the distribution of your trait data on the tree. Look for outliers. | Consider using a robust estimation method or re-check the data for measurement error. |

| Poorly resolved or incorrect tree topology [8] | Check the support values (e.g., bootstrap) for key nodes in your phylogeny. | If possible, use a more robust phylogeny. Be cautious when interpreting ancestral states at poorly supported nodes. |

| Mismatch between model and trait evolution [4] | The simple Brownian motion model may be inadequate. | Fit and compare alternative models (e.g., OU, Early-Burst) in phytools to find one that better describes your trait's evolutionary process [4]. |

Problem 3: Inaccurate Phylogenetic Signal Estimation

Symptoms: The estimate of phylogenetic signal (e.g., Pagel's λ) is at the boundary of its possible range (e.g., 0 or 1).

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Small sample size (fewer species) [8] | Check the number of tips in your tree. | Be aware that estimates of λ can be imprecise with small N. The biological interpretation of a boundary value should be made cautiously. |

| Incorrect branch lengths [8] | Try transforming branch lengths (e.g., logarithmic) or using a unit tree. | Re-estimate the phylogeny with reliable branch length information if possible. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Testing for Trait Covariation with PGLS

This protocol tests for a relationship between two continuous traits while accounting for phylogeny.

1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Tree | A hypothesis of the evolutionary relationships among your study species, with meaningful branch lengths (e.g., time, genetic divergence) [8]. |

| Trait Dataset | A table of continuous phenotypic or ecological measurements for each species in the phylogeny. |

| R Statistical Environment | The core software platform for statistical computing [4]. |

phytools R package |

A comprehensive library for phylogenetic comparative analysis, including model fitting and visualization [4]. |

ape R package |

Provides core functions for reading, writing, and manipulating phylogenetic trees [4]. |

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Prepare Data. Ensure your trait data matrix and phylogenetic tree have matching species names.

- Step 2: Fit PGLS Model. Using the

pglsfunction (from thecaperpackage) or similar functions inphytoolsornlme, fit a linear model between trait Y and trait X, specifying the phylogenetic tree and an evolutionary model (commonly Brownian motion or Pagel's λ) [8] [4]. - Step 3: Check Model Assumptions. Examine the distribution of the phylogenetically corrected residuals for normality and homoscedasticity.

- Step 4: Interpret Results. Evaluate the significance and slope of the relationship between trait X and trait Y from the PGLS model output.

Protocol 2: Implementing Delayed-Response Phylogenetic Correlation

This protocol is used to detect trait correlations that may involve evolutionary time lags [14].

1. Methodology

- Step 1: Map Character Changes. For two continuous traits, map their evolutionary changes onto the phylogenetic tree using a method such as squared-change parsimony.

- Step 2: Generate Data Pairs. Form data pairs for regression/correlation in two ways: "tree-down" and "tree-up," matching corresponding changes in X and Y.

- Step 3: Apply Distance Weighting. Weight each data pair by the nodal or branch-length distance between the changes in X and Y. Immediate responses (same node) get maximum weight; delayed responses are penalized.

- Step 4: Calculate Weighted Correlation. Compute a weighted correlation coefficient (r) or slope (b) using all combinations of character reconstructions.

- Step 5: Perform Randomization Test. Generate a null distribution by randomly reallocating trait changes across the tree topology and compare the observed correlation range to this distribution.

The table below summarizes the primary methods discussed, helping you select the right tool for your research question.

| Method Name | Primary Research Question | Key Strength | Software Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts [8] | Does trait X correlate with trait Y across species? | Transforms tip data into statistically independent contrasts. | ape (R), phytools (R) |

| PGLS [8] | Does trait X correlate with trait Y, controlling for phylogeny? | A flexible GLS framework that can incorporate different models of evolution (BM, OU, λ). | caper (R), nlme (R), phytools (R) |

| Delayed-Response Correlation [14] | Do two traits covary, but with an evolutionary lag? | Explicitly tests for and incorporates asynchronous trait evolution, preventing falsely non-significant results. | Custom implementation |

| Stochastic Character Mapping [4] | What is the history of a discrete character on the tree? What are the ancestral states? | Uses simulation to account for uncertainty in the history of discrete character evolution. | phytools (R) |

Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) in Comparative Genomics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is PGLS, and why is it essential in comparative genomics? Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) is a statistical method that measures the correlation between species traits while accounting for their evolutionary relationships. In comparative genomics, species cannot be treated as independent data points because they share traits through common descent. PGLS controls for this phylogenetic non-independence, preventing spurious conclusions and incorrect statistical inferences in genomic analyses [10].

2. My PGLS model fails to converge or produces errors. What should I check? Model convergence issues, such as "false convergence" or errors about infinite values, often stem from several common problems [17]:

- Data and Tree Mismatch: Ensure all species in your data are in the phylogenetic tree and vice versa. Use

name.check()from thegeigerR package to verify this [18] [19]. - Incorrect Function/Argument Syntax: Check for typos in function names (e.g.,

gls) and arguments. Ensure thecorrelationargument correctly specifies the phylogenetic structure (e.g.,corBrownian,corPagel) [20] [17]. - Parameter Scaling: Sometimes, scaling branch lengths of the phylogenetic tree can resolve convergence issues during model fitting [20].

3. How do I choose the right evolutionary model for my PGLS analysis? PGLS can incorporate different models of evolution. You should compare models using information criteria like AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) to select the best fit for your data [21].

- Brownian Motion (BM): Assumes trait divergence increases proportionally with time. Use

corBrownianin R [20]. - Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU): Models trait evolution under stabilizing selection. Use

corMartinsin R [20]. - Pagel's lambda (λ): A multilevel model that scales the phylogenetic covariance structure. Use

corPagelin R [20] [22].

4. My analysis has a high Type I error rate. What might be the cause? Standard PGLS that assumes a homogeneous evolutionary model across the entire tree can produce inflated Type I error rates if the trait has in fact evolved under a heterogeneous model (where the tempo and mode of evolution vary across clades). To address this, consider using methods that account for or test for rate heterogeneity in your phylogenetic regression [22].

5. How can I handle missing data or outliers in my PGLS analysis?

- Missing Data: Techniques like multiple imputation that account for phylogenetic relationships and trait correlations can be used [21].

- Outliers: Consider robust regression techniques or data transformation to reduce their impact. Always investigate whether outliers represent biological reality or measurement error [21].

Troubleshooting Guide

The following table outlines common PGLS errors, their likely causes, and solutions.

| Error Message / Problem | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "false convergence" or "error in eigen(val) : infinite or missing values in 'X'" [17] | Model optimization failure, often due to data-tree mismatch, incorrect syntax, or parameter scaling issues. | Check species names match between data and tree. Verify R function syntax and arguments. Try scaling tree branch lengths [20] [17]. |

| "could not find function 'gls'" or "'corPagel'" [17] | Required R packages are not loaded. | Load necessary libraries: library(nlme) for gls, library(ape) and library(phytools) for corPagel [17]. |

| Inflated Type I error rates [22] | Model misspecification; assuming a homogeneous evolutionary model when the true process is heterogeneous. | Implement PGLS methods that can handle or test for heterogeneous rates of evolution across the phylogeny [22]. |

| "object 'phy' is not of class 'phylo'" [17] | The object provided as the phylogenetic tree is not recognized as a valid tree in R. | Ensure your tree is read correctly (e.g., using read.tree or read.nexus) and is a valid "phylo" object [20] [18]. |

Model does not converge with corPagel [20] |

The maximum likelihood estimation for Pagel's lambda is unstable, potentially due to scaling. | Temporarily multiply all tree branch lengths by a constant (e.g., 100) to aid convergence. This rescales the nuisance parameter without affecting the analysis outcome [20]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Basic PGLS Regression Analysis in R

This protocol outlines the steps to perform a standard PGLS analysis to test for a correlation between two continuous traits.

1. Load Required Packages

2. Import Data and Phylogeny

3. Verify Data-Tree Match

4. Perform PGLS Regression This example fits a model under a Brownian Motion assumption.

Protocol 2: Comparing Evolutionary Models

This protocol extends the basic analysis to compare different evolutionary models using AIC.

1. Fit Multiple Models

2. Compare Model Fit

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential R packages and their primary functions for PGLS analysis.

| Package Name | Key Function(s) | Role in PGLS Analysis |

|---|---|---|

nlme |

gls() |

Fits generalized least squares models, the core function for PGLS [20] [18]. |

ape |

corBrownian(), read.tree() |

Provides evolutionary correlation structures and utilities for reading and handling phylogenetic trees [20] [10]. |

phytools |

corPagel(), corMartins() |

Offers a wide array of phylogenetic comparative methods, including various correlation structures for PGLS [20] [23]. |

geiger |

name.check() |

Crucial for data preparation and checking congruence between trait data and phylogeny [20] [18]. |

caper |

pgls() |

Provides an alternative implementation of PGLS within a comparative analysis framework [10]. |

Technical Support Center: Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My ancestral state reconstruction for migratory behavior is uncertain. How can I improve it? A1: High uncertainty often stems from oversimplified trait coding or insufficient phylogenetic resolution. The 2025 Catharus study achieved robust results by:

- Using Multi-State Coding: Migratory behavior was classified into four distinct states (Sedentary/SED, Elevational Migrant/ELM, Short-Distance Migrant/SDM, Long-Distance Migrant/LDM) instead of a simple binary migrant/resident trait [24].

- Leveraging Large Datasets: The analysis used a nearly comprehensive taxon sample and a genomic-scale dataset of 1,238 Ultra-Conserved Elements (UCEs) to build a well-supported phylogeny [24].

- Incorporating Functional Morphology: Using quantitative morphological traits like "volancy" (a mass-equated ratio of wing to tarsometatarsus length) as a proxy for migratory tendency can provide additional, continuous characters for analysis [24].

Q2: How can I account for a scenario where I know the ancestral state of some internal nodes from fossil or other data? A2: It is possible to fix the state of known internal nodes during reconstruction. The methodology involves:

- Binding Zero-Length Tips: For each internal node with a known state, add a zero-length tip to the tree and assign it the known character state. This effectively constrains the reconstruction at that specific node [23].

- Software Implementation: This technique can be implemented in R using the

phytoolspackage. The key steps involve usingbind.tipto add the tips and then proceeding with a standard ancestral state reconstruction function likeancron the modified tree object [23].

Q3: What are the key morphological correlates of migratory behavior in birds that I should measure? A3: Research on Catharus indicates that migratory behavior is linked to a trade-off between aerial and terrestrial locomotion [24]. Key measurements from museum specimens include:

- Forewing Length: Longer wings are associated with more aerial lifestyles and long-distance migration [24].

- Tarsometatarsus Length: Shorter legs reduce drag during flight and are typical of more volant species [24].

- Body Mass: Use as a migration-independent proxy for overall body size to create mass-equated ratios [24].

- Volancy (θ): A derived value calculated as the mass-equated ratio of wing length to tarsometatarsus length. This composite index shows a strong negative relationship and high phylogenetic signal with migratory strategy [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Phylogenetic ANOVA reveals no significant difference in trait means between groups.

- Potential Cause 1: The model does not account for phylogenetic non-independence, leading to inflated type I errors.

- Solution: Ensure you are using a phylogenetic ANOVA (e.g.,

phylANOVAingeigeror equivalent) that incorporates the tree structure into the model [24]. - Potential Cause 2: High trait variability within groups or poorly defined groups.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the coding of your discrete groups. The Catharus study successfully differentiated strategies by using four carefully defined migratory categories instead of two [24].

Problem: Ancestral state reconstruction for a discrete trait yields equivocal probabilities at key nodes.

- Potential Cause: The model of character evolution may be misspecified or the trait might be highly labile.

- Solution:

- Test Evolutionary Models: Fit and compare different models of discrete trait evolution (e.g., Equal Rates (ER), Symmetric (SYM), All Rates Different (ARD)) to identify the best fit for your data [23].

- Incorporate Additional Data: If possible, use a combined evidence approach. For migration, adding functional morphological data (like volancy) can provide more power to distinguish ancestral states [24].

- Consider a Threshold Model: For traits with an underlying continuous liability, a threshold model might be more appropriate than a standard Markov model [23].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Characterizing Migratory Behavior and Functional Morphology This protocol is adapted from the 2025 Catharus study to model the evolution of migratory behavior [24].

1. Taxon Sampling and Behavioral Coding

- Action: Assemble a comprehensive taxonomic sample. For each operational taxonomic unit (OTU), code its migratory strategy based on literature and tracking data into one of four states:

- SED: Sedentary (year-round resident).

- ELM: Elevational Migrant (seasonal altitudinal movements).

- SDM: Short-Distance Migrant (latitudinal migration without major barriers).

- LDM: Long-Distance Migrant (latitudinal migration across major barriers like oceans).

- Rationale: Fine-scale categorization captures more evolutionary nuance than a binary migrant/resident model.

2. Morphometric Data Collection

- Action: Collect the following measurements from museum study skins for each OTU:

- Forewing length (mm)

- Tarsometatarsus length (mm)

- Tail length (mm)

- Body mass (g) - can be sourced from specimen tags or literature.

- Rationale: These measurements allow quantification of the trade-off between aerial and terrestrial locomotion.

3. Data Analysis

- Action:

- Calculate volancy (θ) as a mass-equated ratio of wing and tarsus length.

- Use phylogenetic ANOVA to test for differences in mean morphological values (wing, tarsus, volancy) among the four migratory strategies.

- Reconstruct the ancestral states of both the discrete migratory strategy and the continuous volancy trait on your time-calibrated phylogeny.

Key Quantitative Findings from Catharus Study [24]

Table 1: Phylogenetic Signal of Morphological Traits

| Trait | Phylogenetic Signal (λ) | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Mass-Equated Wing Length | ≥ 0.99 | < 0.001 |

| Mass-Equated Tarsus Length | ≥ 0.99 | < 0.001 |

| Volancy (θ) | ≥ 0.99 | < 0.001 |

| Body Mass | Not Significant | 0.312 |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Ultra-Conserved Elements (UCEs) | Genomic markers for generating a robust, well-supported phylogeny [24]. |

| Museum Study Skin Morphometrics | Source for key functional morphological measurements (wing, tarsus) [24]. |

| Volancy (θ) Index | A composite quantitative trait representing the trade-off between forelimb and hindlimb investment; a proxy for migratory tendency [24]. |

| Phylogenetic ANOVA | Statistical test to compare trait means among groups while accounting for shared evolutionary history [24]. |

| Multi-State Markov Model | Model for reconstructing the evolution of discrete traits with more than two states (e.g., the 4 migratory strategies) [23]. |

Workflow Visualization

What are phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) and why are they important?

Phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) are statistical techniques used to analyze data from different species or populations while accounting for their phylogenetic relationships. These methods are essential in evolutionary biology because they allow researchers to correct for phylogenetic non-independence of data, reconstruct evolutionary histories, and identify patterns and processes that have shaped the evolution of traits [2]. The key importance of PCMs includes:

- Accounting for phylogenetic history: Species share evolutionary history, which creates non-independence in comparative data

- Trait evolution modeling: Understanding how morphological, behavioral, and molecular traits evolve across lineages

- Diversification studies: Analyzing patterns of speciation and extinction through time

- Multidisciplinary applications: PCMs have expanded beyond evolutionary biology to infectious disease epidemiology, virology, cancer biology, and sociolinguistics [4]

The role of semi-threshold and complex models in modern phylogenetics

Semi-threshold models represent an advanced class of phylogenetic comparative methods that bridge discrete and continuous trait evolution frameworks. These models are particularly valuable for analyzing traits with complex evolutionary dynamics where simple threshold models or continuous models alone are insufficient. The R package phytools has become a crucial platform for implementing these sophisticated models, providing researchers with tools to study trait evolution, diversification dynamics, and biogeographic history [4].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Complex Trait Evolution Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| phytools R package | Software library | Comprehensive phylogenetic comparative analysis | Trait evolution modeling, ancestral state reconstruction, diversification analysis [4] |

| ape R package | Software library | Phylogenetic tree manipulation and analysis | Reading, writing, and manipulating phylogenetic trees [4] |

| geiger R package | Software library | Analysis of evolutionary diversification | Model fitting, likelihood methods, rate estimation [4] |

| Dodonaphy | Software tool | Differentiable phylogenetics via hyperbolic embeddings | Gradient-based tree optimization, variational Bayesian phylogenetics [5] |

| soft-NJ algorithm | Computational method | Differentiable neighbor-joining | Gradient-based optimization over tree space [5] |

| Hyperbolic embeddings | Mathematical framework | Continuous space tree representation | Efficient encoding of trees in continuous spaces [5] |

| Variational Bayesian methods | Statistical framework | Approximation of phylogenetic tree distributions | Capturing uncertainty in evolutionary relationships [5] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Semi-Threshold Models Using Phytools

Objective: Fit and interpret semi-threshold models of trait evolution using the phytools package in R.

Materials Required:

- R statistical environment (version 4.0 or higher)

- phytools package (version 2.0 or higher)

- Phylogenetic tree in Newick or Nexus format

- Trait data in CSV or tab-delimited format

Methodology:

- Environment Setup:

Data Preparation:

Model Fitting:

Model Diagnostics:

Result Interpretation:

Expected Outcomes: This protocol will generate posterior distributions of ancestral states under threshold models, allowing researchers to identify evolutionary transitions between discrete character states while accounting for underlying continuous liabilities.

Protocol 2: Differentiable Phylogenetics with Hyperbolic Embeddings

Objective: Implement gradient-based optimization of phylogenetic trees using continuous space embeddings.

Materials Required:

- Dodonaphy software package

- Genetic sequence data (FASTA format)

- Python environment (for custom implementations)

Methodology:

- Environment Setup:

Data Preparation:

Hyperbolic Embedding:

Tree Optimization:

Variational Bayesian Inference:

Expected Outcomes: This approach enables more efficient exploration of tree space and provides measures of uncertainty for phylogenetic hypotheses through variational approximations.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Model Convergence Issues

Q: My threshold model fails to converge or has low effective sample size. What should I do?

A: Convergence issues in threshold models typically stem from three main sources:

- Insufficient MCMC iterations: Increase the

ngenparameter to at least 2,000,000 generations - Poorly chosen starting values: Use

acefunction to obtain empirical Bayes starting values - Model misspecification: Consider whether a threshold model is appropriate for your data

Solution Protocol:

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check trace plots:

plot(better_model$logLik) - Verify effective sample size > 200 for all parameters

- Compare multiple independent runs to assess consistency

Computational Performance Problems

Q: Analysis of my large dataset (100+ taxa) is computationally prohibitive. What optimization strategies can I use?

A: Large datasets require specialized computational approaches:

Solution Strategies:

- Algorithm Selection:

Technical Optimizations:

Approximation Methods:

- Use stochastic algorithms to escape local optima [5]

- Implement tree reduction techniques for very large datasets

Interpretation Challenges

Q: How do I interpret the output of complex models like hidden-rates or semi-threshold models?

A: Interpretation requires multiple diagnostic approaches:

Interpretation Framework:

- Model Comparison:

Visualization:

Biological Validation:

- Compare model predictions with independent paleontological data

- Test for correlation with environmental factors

- Validate using cross-validation approaches

Data Preparation Challenges

Q: What are the common data formatting issues that affect complex trait evolution analyses?

A: Data preparation problems frequently cause analysis failures:

Common Issues and Solutions:

- Taxon Name Mismatches: Ensure exact matching between tree tip labels and trait data rownames

- Missing Data: Implement appropriate missing data methods rather than complete-case analysis

- Trait Scaling: Standardize continuous traits to mean=0, SD=1 for better model convergence

Data Cleaning Protocol:

Advanced Visualization & Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for semi-threshold model analysis showing data preparation, model fitting, diagnostic checking, and biological interpretation stages.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Different Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Method/Model | Computational Complexity | Optimal Dataset Size | Key Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Mk Model | Low | Small to Medium (10-100 taxa) | Fast convergence, easy interpretation | Basic discrete trait evolution [4] |

| Threshold Model | Medium | Medium (50-200 taxa) | Models discrete traits with underlying continuous liability | Trait threshold evolution, polymorphism [4] |

| Hidden Rates Model | High | Medium to Large (100-500 taxa) | Accounts for rate variation across tree | Heterogeneous evolutionary processes [4] |

| Variational Bayesian with Hyperbolic Embeddings | Medium | Large (500+ taxa) | Efficient approximation, handles uncertainty | Large-scale phylogenetics, uncertainty quantification [5] |

| Differentiable Phylogenetics (soft-NJ) | Medium | Medium to Large (100-1000 taxa) | Gradient-based optimization, continuous space | Tree inference, parameter optimization [5] |

Table 3: Troubleshooting Solutions for Common Experimental Challenges

| Problem Type | Symptoms | Immediate Solutions | Long-term Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Non-convergence | Low ESS, divergent chains, poor mixing | Increase MCMC iterations, adjust tuning parameters, improve starting values | Model reparameterization, algorithm switching (e.g., Hamiltonian Monte Carlo) |

| Computational Limitations | Long run times, memory overflow, crashes | Data subsetting, parallel computing, cloud resources | Algorithm optimization, approximate Bayesian methods, variational inference [5] |

| Biological Implausibility | Unrealistic parameter estimates, poor predictive performance | Model checking, prior sensitivity analysis, expert validation | Model expansion, incorporation of additional data types, integrated models |

| Numerical Instability | NA/NaN values, matrix non-invertibility, singularity warnings | Data transformation, ridge regularization, reinitialization | Alternative likelihood approximations, robust statistical methods |

Navigating Pitfalls: Solutions for Tree Misspecification and Computational Challenges

The Critical Problem of Tree Misspecification and Its Impact on False Discovery

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High False Positive Rates in Phylogenetic Regression

Problem: My phylogenetic comparative analysis is producing unexpectedly high rates of false positive findings.

Explanation: High false positive rates often occur when the phylogenetic tree used in your analysis does not accurately reflect the true evolutionary history of your traits [25]. When you assume an incorrect tree (e.g., using a species tree for traits that evolved along gene trees), the model misrepresents the covariance between species, leading to inflated Type I error rates [25]. Counterintuitively, this problem worsens with larger datasets (more traits and more species), as more data amplifies the signal from the misspecified model [25].

Solution:

- Diagnose: Run your analysis assuming both a species tree and a plausible alternative tree (e.g., a gene tree). If the results (e.g., p-values, effect sizes) differ substantially, your analysis is sensitive to tree misspecification.

- Mitigate: Implement a Robust Phylogenetic Regression using a sandwich estimator [25]. This method is less sensitive to tree misspecification and can dramatically reduce false positive rates.

- Validate: For critical findings, repeat the analysis under multiple plausible tree hypotheses to ensure your conclusions are consistent.

Guide 2: Choosing the Right Phylogenetic Tree for Multi-Trait Analysis

Problem: I am analyzing a dataset with many different types of traits (e.g., morphological, gene expression) and don't know which phylogenetic tree to use.

Explanation: Different traits may have different evolutionary histories. For example, gene expression traits may follow the genealogy of the gene itself, which might not match the species tree due to processes like incomplete lineage sorting [25]. Assuming a single, incorrect tree for all traits is a common cause of model misspecification.

Solution:

- Trait Classification: Categorize your traits based on their suspected genetic architecture. Traits governed by many genes may be well-modeled by the species tree, while traits linked to specific genes might require their respective gene trees.

- Tree Assignment: Where possible, match the tree hypothesis to the trait. This might involve running separate analyses for different classes of traits.