Optimizing Evolutionary Algorithms for Deep Learning Architecture: A Guide for Biomedical Research

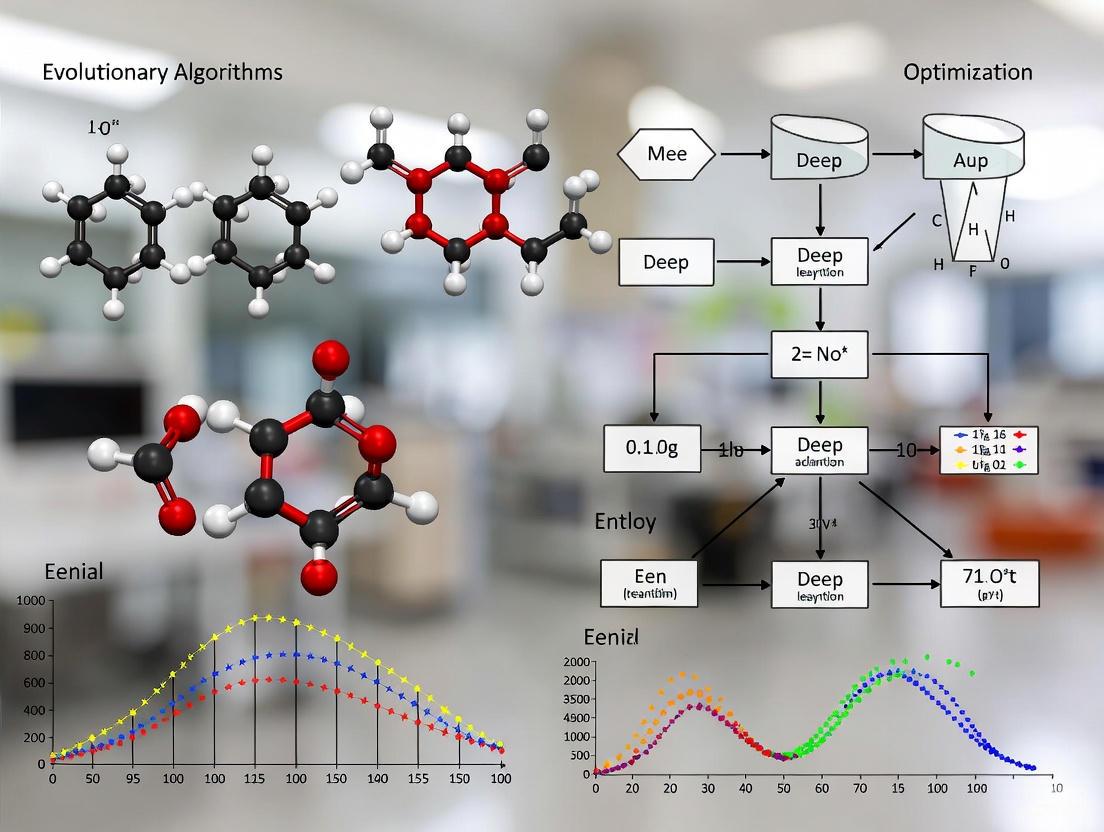

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging evolutionary algorithms (EAs) to automate and enhance deep learning model design.

Optimizing Evolutionary Algorithms for Deep Learning Architecture: A Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging evolutionary algorithms (EAs) to automate and enhance deep learning model design. We cover foundational concepts, from Neural Architecture Search (NAS) and Regularized Evolution to core genetic operators. The piece explores cutting-edge methodologies, including hyperparameter tuning and novel frameworks where deep learning guides evolution. It addresses critical troubleshooting aspects like managing computational cost and avoiding premature convergence. Finally, we present a rigorous validation framework, comparing EA performance against traditional methods and highlighting transformative applications and future directions in biomedical and clinical research.

The Foundations of Evolutionary Deep Learning: From Biological Inspiration to Architectural Search

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are powerful optimization techniques inspired by biological evolution, designed to solve complex problems where traditional methods may fail. For researchers optimizing deep learning architectures, understanding the three core components—populations, fitness functions, and genetic operators—is fundamental to designing effective experiments and achieving breakthrough results in fields like drug development. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to address common experimental challenges.

What is the role of a population in an Evolutionary Algorithm?

The population is the set of potential solutions, often called individuals or chromosomes, that the algorithm evolves over multiple generations.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: The algorithm converges too quickly to a sub-optimal solution.

- Investigation & Solution: This is often a sign of insufficient population diversity. Try increasing the

Population Size. A larger population explores a broader area of the solution space, reducing the risk of premature convergence. Additionally, review yourInitializationmethod; ensure the initial population is randomly generated to cover a wide range of possibilities [1]. - Problem: The algorithm is computationally slow.

- Investigation & Solution: A very large population size can be a major cause of this. Consider reducing the population size to a manageable level, or employ techniques like elitism (carrying the best individuals forward directly) to maintain performance with a smaller population [2].

How is a fitness function defined and what are common pitfalls?

The fitness function is a crucial component that evaluates how well each individual in the population solves the given problem. It quantifies the "goodness" of a solution, guiding the algorithm's search direction. In deep learning research, this could be a metric like validation accuracy, the success rate of a side-channel attack, or the efficiency of a neural network model [3].

FAQ: What should I do if my algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum?

- This can indicate an issue with the fitness function's design. The function might be too steep or may not sufficiently penalize certain weaknesses. Ensure your fitness function accurately captures all aspects of the problem. Introducing techniques like fitness sharing can help maintain diversity by reducing the fitness of individuals in crowded regions of the solution space [1] [4].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: The algorithm finds solutions that score well on the fitness function but perform poorly in practice.

- Investigation & Solution: This is a classic sign of a poorly designed fitness function that does not fully represent the real-world problem. The algorithm is "exploiting" a flaw in your metric. Re-evaluate your fitness function to ensure it aligns perfectly with your ultimate research goal and incorporates all necessary constraints [1].

What are genetic operators and how do they work?

Genetic operators are the mechanisms that drive the evolution of the population by creating new solutions from existing ones. The three primary operators are Selection, Crossover, and Mutation [4] [5].

The following diagram illustrates how these operators work together in a typical evolutionary cycle:

Selection

This operator chooses the fittest individuals from the current population to be parents for the next generation, mimicking "survival of the fittest" [1] [4].

- Advanced Techniques (2025): Modern approaches use adaptive selection methods and AI-based ranking systems to identify the most promising solutions faster and more efficiently [4].

Crossover (or Recombination)

This operator combines the genetic information of two parent solutions to create one or more offspring. This allows the algorithm to explore new combinations of existing traits [4] [6].

- FAQ: Why would I use a multi-parent crossover?

- Combining genetic material from more than two parents, an advanced technique, can create greater variety in the offspring, helping the algorithm explore the solution space more effectively and avoid local optima [4].

Mutation

This operator introduces small, random changes to an individual's genetic code. It is essential for maintaining population diversity and exploring new areas of the solution space that might not be reached through crossover alone [1] [5].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: The population lacks diversity after several generations.

- Investigation & Solution: Your

Mutation Ratemay be too low. Gradually increase the mutation probability to introduce more variation. Consider using adaptive mutation rates that change based on population diversity [4] [7]. - Problem: The algorithm behaves erratically and fails to converge.

- Investigation & Solution: Your

Mutation Rateis likely too high. An excessive mutation rate turns the search into a random walk. Reduce the mutation probability to allow beneficial traits to stabilize and be refined [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Hyperparameter Optimization for Deep Learning Models

This protocol is based on a study that used a Genetic Algorithm (GA) to optimize deep learning models for side-channel analysis, achieving 100% key recovery accuracy [3].

- Problem Formulation: Define the hyperparameter search space (e.g., learning rate, number of layers, layer types, activation functions).

- Population Initialization: Randomly generate an initial population of neural network models, each defined by a unique set of hyperparameters.

- Fitness Evaluation: Train and evaluate each model in the population. The fitness score is the model's performance on a validation metric, such as success rate (SR) or guessing entropy (GE) for side-channel attacks [3].

- Genetic Operations:

- Selection: Use a selection method (e.g., tournament selection) to choose parent models based on their fitness.

- Crossover: Create new offspring models by combining the hyperparameters of two parent models.

- Mutation: Randomly alter some hyperparameters in the offspring with a low probability to introduce new possibilities.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3-4 for multiple generations until a stopping condition is met (e.g., a maximum number of generations or a satisfactory fitness level is reached) [3] [1].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential computational "reagents" for experiments involving evolutionary algorithms in deep learning research.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm Framework | A software library (e.g., PyGAD, DEAP) that provides the foundational structure for implementing evolutionary algorithms, handling population management, and executing genetic operators [8]. |

| Fitness Function | A custom-defined function or model that quantitatively evaluates the performance of each candidate solution (e.g., a trained neural network) based on the research objectives [3] [5]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A powerful computing resource necessary for the parallel evaluation of fitness functions, which is often computationally expensive when training deep learning models [1]. |

| Neural Architecture Search (NAS) Benchmark | A standardized dataset or problem environment used to fairly evaluate and compare the performance of different evolutionary optimization strategies for discovering neural network architectures [3]. |

| Adaptive Genetic Operators | Advanced versions of selection, crossover, and mutation that can automatically adjust their parameters (e.g., mutation rate) during the experiment based on feedback, leading to more robust and efficient optimization [4] [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Neural Architecture Search (NAS) and how does it relate to evolutionary algorithms? Neural Architecture Search (NAS) is a technique within Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) that automates the design of artificial neural networks [9] [10] [11]. It searches a predefined space of possible architectures to find the optimal one for a specific task and dataset [9]. When framed within evolutionary algorithms, NAS treats architecture discovery as an optimization problem where a population of neural network models is evolved over generations [12] [13]. New architectures are generated through mutation and crossover operations, and the fittest models, based on performance, are selected for subsequent generations [9]. The EB-LNAST framework is a contemporary example that uses a bi-level evolutionary strategy to simultaneously optimize network architecture and training parameters [13].

Q2: What are the primary components of a NAS framework? A NAS framework consists of three core components [9] [10] [11]:

- Search Space: Defines the set of all possible neural network architectures to explore. This includes choices over layer types, number of layers, connectivity patterns, and hyperparameters [12] [11].

- Search Strategy: The algorithm that explores the search space. Common strategies include Reinforcement Learning, Evolutionary Algorithms, Bayesian Optimization, and Gradient-Based Methods like DARTS [12] [9] [14].

- Performance Estimation Strategy: The method for evaluating a candidate architecture's performance. Since full training is computationally expensive, strategies use proxy tasks, weight sharing, or one-shot models to speed up estimation [12] [10] [11].

Q3: Why would a researcher choose evolutionary algorithms over other NAS search strategies? Evolutionary algorithms are often chosen for their global search capabilities and ability to explore a wide search space without relying on gradients [12] [8]. They are less likely to get trapped in local optima compared to some gradient-based methods and can discover novel, high-performing architectures that might be overlooked by human designers or other strategies [9] [15]. Furthermore, they exhibit better "anytime performance," meaning they provide good solutions even if stopped early, and have been shown to converge on smaller, more efficient models [10].

Q4: What are the common computational bottlenecks when running evolutionary NAS, and how can they be mitigated? The primary bottleneck is the immense computational cost of training and evaluating thousands of candidate architectures [9] [15]. A full search can require thousands of GPU days [10] [11]. Mitigation strategies include [12] [9] [10]:

- Weight Sharing: As in ENAS, where a supernet's weights are shared across all candidate architectures, eliminating the need to train each one from scratch.

- Proxy Tasks: Performing the search on a smaller dataset, with fewer training epochs, or a downscaled model.

- Low-Fidelity Estimation: Using techniques like learning curve extrapolation to predict final performance based on early training epochs.

- One-Shot Models: Training a single, over-parameterized supernet that contains all architectures in the search space, then evaluating sub-networks without retraining.

Q5: How can I ensure the architectures discovered by my evolutionary NAS are optimal and not overfitted to the proxy task? To prevent overfitting and ensure optimality [15]:

- Robust Validation: Rigorously validate the final, best-performing architecture on a separate, held-out test set and, if possible, on a different but related dataset.

- Progressive Complexity: Start the search with simpler proxy tasks (e.g., smaller datasets) and gradually increase complexity to steer the evolution towards more generalizable architectures.

- Regularization: Incorporate multi-objective optimization that includes not just accuracy but also regularization terms for model size or complexity, as seen in the EB-LNAST framework which penalizes network complexity [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: The Search Process Fails to Find High-Performing Architectures

Symptoms:

- Stagnant or declining performance of the best model in the population over generations.

- The final evolved architecture performs no better than a simple baseline model.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poorly Designed Search Space. The search space may be too restricted, missing valuable architectural innovations, or too vast, making it difficult for the algorithm to find good candidates.

- Solution: Adopt a modular or hierarchical search space [12] [11]. Use a cell-based approach where the evolution searches for optimal building blocks (cells) that are then stacked to form the final network. This reduces the search complexity and has proven effective in architectures like NASNet [12] [9].

- Cause: Ineffective Evolutionary Operators. The mutation and crossover operations may be too destructive or not exploratory enough.

- Solution: Implement "network morphism" or structure-preserving mutations [10]. This allows the evolutionary algorithm to modify the architecture (e.g., adding a layer, changing a kernel size) while retaining the learned knowledge, leading to more stable training and efficient search.

- Cause: Inadequate Population Diversity. The population has converged prematurely, limiting exploration.

- Solution: Introduce mechanisms from newer algorithms like AmoebaNet's tournament selection or regularized evolution, which favor younger models and help maintain diversity within the population [12].

Issue 2: The NAS Experiment is Computationally Prohibitive

Symptoms:

- The experiment requires weeks to complete on a multi-GPU machine.

- Running out of memory during the architecture evaluation phase.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient Performance Estimation. Fully training every candidate model from scratch is the main source of cost.

- Cause: Lack of Hardware Awareness. The search is optimized only for accuracy, leading to models that are impractical to deploy.

- Solution: Use hardware-aware NAS [15]. Incorporate latency, memory footprint, or power consumption as additional objectives in the evolutionary fitness function. This guides the search towards architectures that are not only accurate but also efficient on the target hardware.

Issue 3: The Final Retrained Model Underperforms Expectations

Symptoms:

- The performance of the final, fully trained model is significantly lower than the performance estimated during the search phase.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Optimization Bias from Weight Sharing. In one-shot and weight-sharing methods, the shared weights may not be optimal for every architecture, leading to an inaccurate ranking of candidates [10].

- Solution: Use the architecture found via the fast search as a starting point and perform a "re-training from scratch" phase without weight sharing. Additionally, you can use the results from the fast search as a prior for a more focused, but lighter, evolutionary search without weight sharing.

- Cause: Overfitting to the Search Validation Set. The evolutionary process may have exploited peculiarities of the small validation set used during the search.

- Solution: Apply strong data augmentation during the search and final training [14]. Ensure the validation set used for the search is large and representative. Finally, validate the final model on a completely separate test set.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing a Basic Evolutionary NAS Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for a standard evolutionary NAS process [12] [9].

- Define the Search Space:

- Choose a search space type, such as a cell-based space where the algorithm evolves a single computational cell that is stacked to form the network [11].

- Define the allowed operations (e.g., 3x3 convolution, 5x5 depthwise convolution, max pooling, identity, zeroize).

- Initialize Population:

- Generate an initial population of

Nrandom architectures from the defined search space.

- Generate an initial population of

- Evaluate Population (Performance Estimation):

- For each architecture in the population, estimate its fitness (e.g., validation accuracy).

- To save time, use a low-fidelity method: train for a reduced number of epochs on a subset of the data [10].

- Evolve New Generation:

- Selection: Select the top-

Kbest-performing architectures as parents. - Crossover: Create new "child" architectures by combining components from two parent architectures.

- Mutation: Randomly modify child architectures by changing an operation, adding/removing a connection, or altering a hyperparameter.

- Selection: Select the top-

- Iterate:

- Replace the old population with the new generation of children.

- Repeat steps 3-5 for a fixed number of generations or until performance plateaus.

- Final Training:

- Select the best architecture found during the search.

- Train it from scratch on the full dataset with a full training schedule for a fair evaluation.

Protocol 2: Bi-Level Optimization for Architecture and Parameters

This protocol is based on frameworks like EB-LNAST, which simultaneously optimize the architecture and its training parameters [13].

- Problem Formulation:

- Upper-Level (Architecture) Optimizer: Managed by the evolutionary algorithm. Its goal is to minimize network complexity, penalized by the lower-level's performance.

- Lower-Level (Weight) Optimizer: For a given architecture from the upper level, it uses gradient descent (e.g., Adam, SGD) to minimize the loss function on the training data.

- Algorithm Workflow:

- The evolutionary algorithm (upper level) proposes a population of candidate architectures.

- For each candidate architecture, the lower-level optimizer trains the network's weights.

- The fitness of each architecture is a function of its final validation performance (from the lower level) and its complexity (e.g., number of parameters).

- The evolutionary algorithm uses this fitness to select, crossover, and mutate architectures for the next generation.

- This process continues, jointly optimizing the high-level architecture and low-level weights.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key components and their functions for setting up an Evolutionary NAS experiment.

| Research Reagent | Function in Evolutionary NAS |

|---|---|

| Search Space Definition | Defines the universe of all possible neural network architectures that the algorithm can explore [12] [11]. Examples include chain-structured, cell-based, and hierarchical spaces. |

| Evolutionary Algorithm | The core search strategy that explores the search space by evolving a population of architectures through selection, crossover, and mutation [12] [9]. Examples include Regularized Evolution (AmoebaNet) and Genetic Algorithms. |

| Performance Estimator | A method to quickly evaluate the fitness of a candidate architecture without full training [11]. This includes proxy tasks, weight sharing in one-shot models, and low-fidelity training [10]. |

| Supernet (One-Shot Model) | A single, over-parameterized neural network that contains all architectures in the search space as subnetworks. It enables efficient weight sharing across architectures [12] [11] [15]. |

| Fitness Function | The objective that guides the evolutionary search. It is often a combination of performance metrics like validation accuracy and efficiency metrics like model size or latency [13] [15]. |

Workflow and Algorithm Diagrams

Evolutionary NAS High-Level Workflow

Bi-Level Optimization in EB-LNAST

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Regularized Evolution NAS

FAQ: My evolutionary search is stuck in a performance plateau. What can I do?

A performance plateau often indicates insufficient exploration in your evolutionary algorithm [16]. To address this:

- Implement guided mutation: Steer mutations toward unexplored regions of your search space by calculating probability vectors from your current population's genetic material [16].

- Adjust selection pressure: Ensure your tournament selection size (typically 5-10% of population) provides adequate selective pressure without premature convergence [17].

- Verify aging mechanism: Regularly discard the oldest architectures in your population, not the worst-performing, to prevent stagnation and encourage novelty [17].

FAQ: How do I manage computational budget with large population sizes?

Regularized Evolution achieves efficiency through its aging mechanism, but these strategies help further:

- Implement weight sharing: Reuse parameters across similar architectures to reduce training time for new candidates [13].

- Use proxy metrics: Employ lower-fidelity performance estimates (e.g., shorter training epochs, subset of data) for initial screening [16].

- Apply early stopping: Terminate training of poorly-performing architectures quickly to reallocate resources [17].

FAQ: My architectures fail to generalize after evolution. How can I improve robustness?

Poor generalization suggests overfitting to the validation set during search:

- Regularize child networks: Incorporate dropout, L2 regularization, or batch normalization during architecture evaluation [13].

- Diversify validation data: Use multiple validation sets or data augmentation to prevent overspecialization [17].

- Enforce complexity constraints: Add parameter count or FLOPs as a secondary objective to discourage overly complex solutions [13].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Regularized Evolution Workflow

The Regularized Evolution algorithm improves upon standard evolutionary approaches by incorporating an aging mechanism that discards the oldest models in the population rather than the worst-performing [17]. This prevents premature convergence and maintains diversity throughout the search process.

Implementation Protocol:

Population Initialization

- Generate initial population of neural architectures with random configurations

- For each architecture: train to convergence, evaluate on validation set, record accuracy as fitness

Evolution Cycle

- Selection: Randomly sample N individuals (typically 5-10% of population), select best performer as parent [17]

- Mutation: Create offspring by applying mutation operations to parent architecture

- Evaluation: Train offspring architecture, evaluate on validation set

- Population Update: Add offspring to population, remove oldest individual (aging mechanism)

Termination Condition

- Continue evolution until computational budget exhausted or performance convergence observed

Key Experimental Parameters

Table: Regularized Evolution Hyperparameters for NAS

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Impact on Search |

|---|---|---|

| Population Size | 100-500 individuals | Larger populations increase diversity but require more computation |

| Tournament Size | 5-10% of population | Larger tournaments increase selection pressure |

| Mutation Rate | 0.1-0.3 per gene | Higher rates increase exploration |

| Aging Mechanism | Remove oldest individual | Prevents stagnation, maintains novelty |

| Initialization | Random architectures | Ensures diverse starting population |

Bi-Level Optimization Extension

For enhanced performance, recent approaches combine Regularized Evolution with bi-level optimization [13]:

- Upper Level: Minimizes network complexity penalized by lower level performance

- Lower Level: Optimizes training parameters to minimize loss function

This approach has demonstrated up to 99.66% reduction in model size while maintaining competitive performance [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for Evolutionary NAS Experiments

| Component | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture Encoder | Represents neural networks as evolvable genotypes | Use layer and connection genes to encode topology and parameters [17] |

| Fitness Evaluator | Measures architecture performance | Typically uses validation accuracy; can incorporate multi-objective metrics [13] |

| Mutation Operator | Introduces architectural variations | Modify layer types, connections, or hyperparameters; guide using population statistics [16] |

| Aging Registrar | Tracks individual age in population | Implement as FIFO queue or timestamp-based system [17] |

| Performance Proxy | Estimates architecture quality without full training | Uses partial training, weight sharing, or surrogate models [16] |

Workflow Visualization

Evolutionary Workflow for Regularized Evolution NAS

Architecture Encoding Using Genetic Representation

Performance Benchmarking

Table: Comparative Performance of Evolutionary NAS Methods

| Method | Search Type | Test Accuracy | Model Size Reduction | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regularized Evolution [17] | Macro-NAS | 94.46% (Fashion-MNIST) | Not reported | Lower than RL methods |

| PBG (Population-Based Guiding) [16] | Micro-NAS | Competitive | Not reported | 3x faster than Regularized Evolution |

| EB-LNAST [13] | Bi-level NAS | Competitive (WDBC) | Up to 99.66% | Moderate |

| MLP with Hyperparameter Tuning [13] | Manual | Baseline +0.99% | Baseline | Lower |

This technical support resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with practical implementation guidance for Regularized Evolution in Neural Architecture Search, enabling more robust and efficient architecture discovery for deep learning applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core practical difference between a Genetic Algorithm (GA) and a broader Evolutionary Algorithm (EA)?

In practice, Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) serve as a general framework for optimization techniques inspired by natural evolution. In contrast, a Genetic Algorithm (GA) is a specific type of EA that emphasizes genetic-inspired operations like crossover and mutation, typically representing solutions as fixed-length chromosomes (often binary or real-valued strings). Other EA variants, such as Evolution Strategies (ES), may focus more on mutation and recombination for continuous optimization problems and use different representations, like real-number vectors [18].

Q2: My deep learning model for drug discovery is converging to a poor local minimum. How can EAs help?

Evolutionary Algorithms are potent tools for global optimization and can effectively navigate complex, multi-modal search spaces where gradient-based methods often fail. By maintaining a population of solutions and using operators like mutation and crossover, EAs can explore a wide range of the solution space and are less likely to get trapped in local optima compared to methods like gradient descent [18] [19]. They are particularly suitable for optimizing non-differentiable or noisy objective functions common in real-world applications.

Q3: I need to optimize both the architecture and hyperparameters of a deep learning model for near-infrared spectroscopy. Which EA variant is most suitable?

For complex tasks like neural architecture search (NAS) in spectroscopy, a Genetic Algorithm (GA) is often an excellent choice. Recent research has successfully applied GA to dynamically select and configure network modules (like 1D-CNNs, residual blocks, and Squeeze-and-Excitation modules) for multi-task learning on spectral data [20]. GAs efficiently navigate the vast search space of potential architectures, automating the design process and eliminating the need for manual, expert-based design, which can be time-consuming and suboptimal [20].

Q4: When performing virtual high-throughput screening on ultra-large chemical libraries, how can I make the process computationally feasible?

For screening ultra-large make-on-demand chemical libraries (containing billions of compounds), using a specialized Evolutionary Algorithm is a state-of-the-art approach. Algorithms like REvoLd are designed to efficiently search combinatorial chemical spaces without enumerating all molecules. They exploit the structure of these libraries by working with molecular building blocks and reaction rules, allowing for the exploration of vast spaces with just a few thousand docking calculations instead of billions [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Performance and Premature Convergence

Problem: Your EA is converging too quickly to a suboptimal solution, lacking diversity in the population.

Solutions:

- Implement a "Random Jump" Mechanism: Introduce an operation that randomly alters a portion of a solution if it shows no improvement over several generations. This helps the algorithm escape local optima [22].

- Adjust Selection Pressure: Over-reliance on the fittest individuals can reduce diversity. Allow some less-fit solutions to participate in crossover and mutation to carry their unique genetic material forward [21].

- Tune Operator Rates: Experiment with the rates of crossover and mutation. Increasing the mutation rate can introduce more diversity, but if set too high, it can turn the search into a random walk [3].

Issue 2: Handling Mixed Parameter Types (Discrete and Continuous)

Problem: Your optimization problem involves both discrete (e.g., number of layers) and continuous (e.g., learning rate) parameters, which is challenging to encode.

Solutions:

- Use a Real-Valued Representation: Instead of binary chromosomes, represent individuals as real-valued vectors. This is more natural for continuous parameters and can be extended for discrete choices by rounding or using categorical distributions [18] [20].

- Employ a Hybrid EA: Consider using an Evolution Strategy (ES), which is particularly well-suited for continuous optimization problems and can be adapted for mixed-type spaces [18].

Issue 3: High Computational Cost of Fitness Evaluation

Problem: The fitness function (e.g., training a neural network or docking a molecule) is extremely time-consuming, making the EA run prohibitively slow.

Solutions:

- Integrate a Replay Buffer: Store and reuse past evaluations. If an individual (or a very similar one) has been evaluated before, retrieve its fitness from the buffer to avoid redundant computations [19].

- Utilize Parallelization: EAs are naturally parallelizable. Distribute fitness evaluations across multiple CPUs or GPUs since individuals in a population can be evaluated independently [18].

- Leverage Surrogate Models: Train a fast, approximate model (e.g., a neural network) to predict the fitness of new individuals based on past evaluations, reducing the number of expensive true fitness calculations [23].

Experimental Data & Protocol Summaries

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Evolutionary and Deep Learning Methods for Molecular Optimization

| Method | Type | Key Feature | Reported Performance (QED Score) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIB-SOMO [22] | Evolutionary (Swarm) | MIX operation with LB/GB | Finds near-optimal solutions quickly | Fast, computationally efficient, easy to implement | Free of chemical knowledge, may require domain adaptation |

| EvoMol [22] | Evolutionary (Hill-Climbing) | Chemically meaningful mutations | Effective across various objectives | Generic, straightforward molecular generation | Inefficient in expansive domains due to hill-climbing |

| JT-VAE [22] | Deep Learning | Maps molecules to latent space | N/A | Allows sampling and optimization in latent space | Performance dependent on training data quality |

| MolGAN [22] | Deep Learning | Operates directly on molecular graphs | High chemical property scores | Faster training than sequential models | Susceptible to mode collapse, limited output variability |

| Sample Type | Predicted Trait | Performance (R²) | Performance (RMSE) | Key Optimized Architecture Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Ginseng | PPT (saponins) | 0.93 | 0.70 mg/g | 1D-CNN, Residual Blocks, SE modules |

| American Ginseng | PPD (saponins) | 0.98 | 2.03 mg/g | Gated Interaction (GI), Feature Fusion (FFI) modules |

| Wheat Flour | Protein Content | 0.99 | 0.29 mg/g | 1D-CNN, Batch Normalization |

| Wheat Flour | Moisture Content | 0.97 | 0.22 mg/g | Feature Transformation Interaction (FTI) modules |

Objective: To automatically design a multi-task deep learning model for predicting multiple quality indicators from NIR spectral data.

Methodology:

- Problem Encoding: Define the search space. This includes:

- Backbone Components: 1D-CNN, Batch Normalization (BN) layers, Residual Blocks (Resblock), Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) modules.

- Task-Specific Interaction Modules: Gated Interaction (GI), Feature Fusion Interaction (FFI), Feature Transformation Interaction (FTI).

- Genetic Algorithm Workflow:

- Initialization: Create an initial population of neural network architectures, each formed by a random combination of the available components.

- Fitness Evaluation: Train and evaluate each architecture in the population. The fitness function is the model's performance (e.g., R², RMSE) on validation data for all prediction tasks.

- Selection: Select the best-performing architectures as parents for the next generation using a tournament selection strategy.

- Crossover: Recombine components from two parent architectures to create offspring architectures.

- Mutation: Randomly alter components in an offspring architecture (e.g., swap a 1D-CNN for a Resblock, add/remove an SE module).

- Termination: Repeat for a fixed number of generations or until performance plateaus.

- Outcome: The GA produces an optimized, task-specific neural network architecture without manual design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for EA-Driven Deep Learning Research

| Tool / Component | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RosettaLigand / REvoLd [21] | Flexible protein-ligand docking platform integrated with an EA. | Structure-based drug discovery on ultra-large chemical libraries. |

| Enamine REAL Space [21] | A "make-on-demand" library of billions of synthesizable compounds. | Provides the chemical search space for evolutionary drug optimization. |

| 1D-CNN Modules [20] | Neural network components for processing sequential data like spectra. | Feature extraction from NIR spectral data in automated architecture search. |

| Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) Modules [20] | Architectural units that adaptively recalibrate channel-wise feature responses. | Enhances feature extraction in GA-optimized networks for spectral analysis. |

| Gated Interaction (GI) Modules [20] | Allows controlled sharing of information between related learning tasks. | Improves performance in multi-task learning models discovered by GAs. |

| Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED) [22] | A composite metric that scores compounds based on desirable molecular properties. | Serves as a fitness function for evolving drug-like molecules. |

Workflow and Algorithm Diagrams

EA for Deep Learning Optimization

GA-Optimized MTL Architecture

Advanced Methods and Practical Applications in Evolutionary Deep Learning

Automating Hyperparameter Optimization with Evolutionary Computation

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common challenges you might encounter when implementing evolutionary algorithms for hyperparameter optimization (HPO) in a deep learning research environment.

FAQ 1: My evolutionary algorithm converges too quickly to a suboptimal model performance. How can I improve exploration?

- Problem: Premature convergence, where the algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum, is a common issue in evolutionary computation [24] [25].

- Solutions:

- Increase Mutation Rates: Temporarily increase the mutation probability or the magnitude of mutations to introduce more diversity into the population [25].

- Review Selection Pressure: If using a Genetic Algorithm (GA), check your tournament size (

N_tour) and selection probability (P_tour). Excessively high values can cause premature convergence by overly favoring the current best performers. Adjust these parameters to allow less-fit individuals a chance to propagate their genetic material [26]. - Dynamically Adjust Parameters: For Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), implement a time-dependent inertial weight (

w). Start with a high value (e.g., 0.9) to encourage global exploration and gradually reduce it to hone in on promising areas [26]. - Re-initialize Part of the Population: Introduce a small number of randomly generated individuals into the population every few generations to maintain genetic diversity.

FAQ 2: The optimization process is computationally expensive. How can I make it more efficient?

- Problem: Evaluating the fitness of each hyperparameter set by training a deep learning model is inherently time-consuming [27].

- Solutions:

- Leverage Parallelization: Evolutionary algorithms are embarrassingly parallel at the population level. Distribute the fitness evaluation of individuals across multiple GPUs or compute nodes to drastically reduce wall-clock time [28].

- Implement Multi-Fidelity Methods: Use techniques like successive halving or Hyperband to terminate training for poorly performing hyperparameter sets early, conserving resources for more promising candidates [27] [28].

- Adjust Population and Generation Parameters: There is often a trade-off between population size and the number of generations. A moderate population size run for more generations can sometimes find better solutions more efficiently than a large population run for fewer generations. For example, one study found a population of 200 with 30 generations to be a good balance [29].

FAQ 3: How do I handle both continuous and categorical hyperparameters within the same evolutionary framework?

- Problem: The hyperparameter search space often includes both types (e.g., learning rate is continuous, while optimizer type is categorical).

- Solutions:

- Encoding: This is typically handled by using a suitable encoding scheme within the chromosome or particle position.

- For Genetic Algorithms (GAs): A mixed encoding strategy works well. Represent continuous parameters with floating-point numbers and categorical parameters with integers. Ensure that crossover and mutation operators are designed to work appropriately with each data type [26].

- For Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): Since PSO operates in a continuous space, you can round the continuous values for categorical parameters to the nearest integer when constructing the actual model for fitness evaluation [26].

FAQ 4: How do evolutionary methods for HPO compare to traditional methods like Grid Search and Random Search?

- Answer: Evolutionary algorithms generally offer a superior balance of efficiency and effectiveness, especially in complex, high-dimensional search spaces.

- Performance Comparison:

- Grid Search: Becomes computationally intractable due to the "curse of dimensionality" as the number of hyperparameters grows. It is inefficient for exploring large spaces [27] [28].

- Random Search: Often outperforms grid search and is an important baseline. It is better at exploring the overall space but has no mechanism for leveraging information from good hyperparameter sets to find better ones [27] [28].

- Bayesian Optimization (BO): A strong competitor, BO builds a probabilistic model to guide the search. Studies have shown that enhancing BO with evolutionary algorithms like Differential Evolution (DE) or Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) can improve its performance [27].

- Evolutionary Algorithms (PSO, GA): These methods efficiently explore the search space by combining exploration (testing new areas) and exploitation (refining known good areas). They have been shown to find better hyperparameter settings than random search and can outperform standard Bayesian optimization in certain scenarios [27] [26].

Quantitative Comparison of HPO Methods

The table below summarizes the typical characteristics of different HPO methods based on findings from the literature [27] [28] [26].

| Method | Search Strategy | Parallelization | Scalability to High Dimensions | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Search | Exhaustive, systematic | Excellent | Poor | Small, low-dimensional search spaces |

| Random Search | Random sampling | Excellent | Good | Establishing a performance baseline |

| Bayesian Optimization | Sequential model-based | Poor | Good | When function evaluations are very expensive |

| Evolutionary Algorithms | Population-based, guided | Excellent | Very Good | Complex, noisy, and high-dimensional spaces |

Experimental Protocols for Evolutionary HPO

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing two key evolutionary algorithms for HPO, as referenced in recent literature.

Protocol 1: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for Hyperparameter Tuning

This protocol is adapted from applications in high-energy physics and AutoML systems [27] [26].

Initialization:

- Swarm Size: Initialize a population (swarm) of particles. A typical size ranges from 20 to 100+ [28] [26].

- Position (

x_i^0): Each particle's position is randomly initialized within the predefined bounds of the hyperparameter spaceH. This position represents one set of hyperparameters. - Momentum (

p_i^0): Each particle's momentum is randomly initialized, often within a fraction (e.g., one quarter) of each hyperparameter's range [26]. - Parameters: Set the cognitive and social weights (

c1,c2), often to 2.0. Define the inertial weight (w), which can be constant or decay over time. Choose the number ofN_infoparticles that contribute to the global best [26].

Iteration Loop (for k generations):

- Fitness Evaluation: For each particle, train the target machine learning model using the hyperparameters defined by its current position

x_i^k. Evaluate the fitness (e.g., validation set accuracy) as the scores(x_i^k). - Update Personal Best (

x_i^k): If the current position's fitness is better than the particle's personal best, update the personal best position. - Update Global Best (

x^k): Identify the best personal best position among theN_infoparticles and set it as the new global best. - Update Position and Momentum:

- Apply Boundary Constraints: If a particle moves outside the search space, clamp its position to the boundary and set its momentum to zero.

- Fitness Evaluation: For each particle, train the target machine learning model using the hyperparameters defined by its current position

Termination: The process repeats until a maximum number of generations is reached, a satisfactory fitness is achieved, or performance plateaus.

Protocol 2: Genetic Algorithm (GA) for Hyperparameter Tuning

This protocol is based on implementations used in drug discovery and machine learning benchmarking [29] [27] [26].

Initialization:

- Population Size: Create an initial population of chromosomes. Common sizes are in the range of 50 to 200 individuals [29] [26].

- Chromosome Encoding: Each chromosome encodes a full set of hyperparameters. Continuous parameters can be represented by floating-point numbers, while categorical parameters are represented by integers [26].

Evolutionary Loop (for k generations):

- Evaluation: Train and evaluate the model for each chromosome in the population to determine its fitness score.

- Selection (Tournament Method):

- Randomly select

N_tourchromosomes from the population to form a tournament. - Rank them by fitness and select the winner with a probability

P_tour. If not selected, try the next best, and so on [26]. - Repeat until enough parents are selected for the next generation.

- Randomly select

- Crossover (Recombination): Pair up parents to create offspring. For each pair, swap segments of their chromosomes (hyperparameters) with a given probability to produce new candidate solutions.

- Mutation: With a small probability, randomly alter genes (hyperparameters) in the offspring. For continuous parameters, this could be adding Gaussian noise; for categorical, it could be randomly switching to another valid option [29].

- Form New Population: The new generation is formed from the offspring, sometimes with a strategy (elitism) that carries over the best-performing individuals from the previous generation unchanged.

Termination: The algorithm terminates after a set number of generations or when convergence criteria are met.

Workflow Diagram: Evolutionary Hyperparameter Optimization

The diagram below illustrates the general workflow for automating HPO with an evolutionary algorithm, integrating components from both PSO and GA approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and algorithms essential for conducting evolutionary HPO experiments in deep learning research.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | A population-based optimizer inspired by natural selection. It is highly effective for navigating mixed (continuous/categorical) hyperparameter spaces using selection, crossover, and mutation operators [24] [26]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | An evolutionary algorithm inspired by social behavior. Particles fly through the hyperparameter space, adjusting their paths based on their own experience and the swarm's best-found solution, offering efficient exploration [26]. |

| Differential Evolution (DE) | A robust evolutionary strategy that creates new candidates by combining the differences between existing population members. It has been shown to improve the performance of standard Bayesian optimization in AutoML systems [27]. |

| Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) | An advanced evolutionary algorithm that dynamically updates the covariance matrix of its search distribution. It is particularly powerful for optimizing continuous hyperparameters in complex, non-linear landscapes [27]. |

| RosettaEvolutionaryLigand (REvoLd) | A specialized evolutionary algorithm for ultra-large library screening in drug discovery, demonstrating the application of EA for optimizing molecules (a form of hyperparameter) with full ligand and receptor flexibility [29]. |

| Lipizzaner Framework | A framework for training Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) using coevolutionary computation, addressing convergence issues like mode collapse. It exemplifies the application of EAs beyond traditional HPO [30]. |

Parameter Configuration for Evolutionary Algorithms

The table below provides a summary of key parameters for PSO and GA, with values informed by experimental setups in the search results [29] [26].

| Algorithm | Parameter | Description | Typical/Tested Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO | Swarm Size | Number of particles in the swarm. | 20 - 100+ [28] [26] |

Inertial Weight (w) |

Controls particle momentum. | Can decay from ~0.9 to ~0.4 [26] | |

Cognitive/Social Weights (c1, c2) |

Influence of personal vs. global best. | Often set to 2.0 [26] | |

| GA | Population Size | Number of chromosomes. | 50 - 200 [29] [26] |

Tournament Size (N_tour) |

Number of candidates in a selection tournament. | e.g., 3 [26] | |

Selection Probability (P_tour) |

Probability to select the tournament winner. | e.g., 0.85 - 1.0 [26] | |

| Generations | Number of evolutionary cycles. | ~30 (or until convergence) [29] |

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common problems encountered when implementing and running CoDeepNEAT experiments, helping researchers diagnose and resolve issues efficiently.

Population Stuck at Low Fitness

Symptoms:

- Fitness shows minimal improvement over many generations (20-50+)

- Best and average fitness plateau far from the target threshold

- Generation output shows little to no progress over time

Example of problematic output:

Causes & Solutions:

Table: Diagnosing and Resolving Stagnant Populations

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Fitness Function Issues | Check if genome.fitness is set for every genome; Verify fitness values are reasonable and differentiated; Confirm better performance equals higher fitness [31] |

Debug fitness function: Print sample values, check range and distribution; Ensure fitness increases with better performance [31] |

| Insufficient Genetic Diversity | Monitor species count and size; Check if population converges to similar structures prematurely [31] | Increase population size (150-300); Decrease compatibility threshold (e.g., 2.5 instead of 3.0) to create more species [31] |

| Inappropriate Network Structure | Review activation functions for problem domain; Check if recurrence is needed for temporal problems [31] | Use activation_options = tanh sigmoid relu; Set feed_forward = False for sequential problems; Start with 1-2 hidden nodes [31] |

| Overly Ambitious Fitness Target | Compare current fitness with problem complexity and computational resources [31] | Set realistic fitness thresholds; Allow more generations for complex problems [31] |

Debugging Code Example:

Look for: All None values (fitness not set), identical values (not differentiating performance), or decreasing values with better performance (sign backwards) [31]

All Species Went Extinct

Symptoms:

- Error message:

RuntimeError: All species have gone extinct - Generation output shows:

Population of 0 members in 0 species - Total extinctions reported during evolution

Causes & Solutions:

Table: Preventing and Recovering from Species Extinction

| Cause | Symptoms | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-positive Fitness Values | All genomes have fitness ≤ 0, preventing selection [31] | Ensure positive fitness: genome.fitness = max(0.001, raw_fitness) or shift with raw_fitness + 100.0 [31] |

| Population Too Small | Small populations vulnerable to random extinction events [31] | Increase population size to minimum 150; Use 300+ for complex problems [31] |

| Overly Aggressive Speciation | Too many tiny species that cannot survive [31] | Increase compatibility threshold (e.g., 4.0 instead of 2.0) to reduce species count [31] |

| Excessive Stagnation Removal | Species removed before they can improve [31] | Adjust stagnation settings: max_stagnation = 30 and species_elitism = 3 [31] |

| Extinction Cascades | Multiple species going extinct in succession [31] | Enable extinction recovery: reset_on_extinction = True in configuration [31] |

Monitoring Species Health:

Network Complexity Exploding

Symptoms:

- Networks develop hundreds of nodes/connections within few generations

- Evolution becomes computationally slow

- Fitness improves but networks become unnecessarily large

- Difficult to interpret or deploy evolved networks

Example of complexity explosion:

Causes & Solutions:

Table: Controlling Network Complexity

| Cause | Impact | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Mutation Rates | Excessive addition of nodes and connections [31] | Reduce addition probabilities: conn_add_prob = 0.3, node_add_prob = 0.1; Increase deletion: conn_delete_prob = 0.7, node_delete_prob = 0.5 [31] |

| No Complexity Pressure | Fitness function only rewards performance, not efficiency [31] | Add complexity penalty: fitness = task_fitness - 0.01 * (num_connections + num_nodes) [31] |

| Multiple Structural Mutations | Multiple structural changes per generation accelerate growth [31] | Enable single structural mutation: single_structural_mutation = true [31] |

| Overly Complex Initialization | Starting networks too large for the problem [31] | Start simple: num_hidden = 0, initial_connection = full (inputs to outputs only) [31] |

Complexity-Aware Fitness Function:

Checkpoint Restoration Errors

Symptoms:

AttributeError: 'DefaultGenome' object has no attribute 'innovation_tracker'FileNotFoundError: neat-checkpoint-50pickle.UnpicklingError: invalid load key- Incompatible checkpoint versions

Causes & Solutions:

Table: Checkpoint Management and Recovery

| Problem | Error Type | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Version Incompatibility | Innovation tracking changes between versions [31] [32] | Check NEAT-Python version: print(f"NEAT-Python version: {neat.__version__}"); Note: v1.0+ checkpoints incompatible with v0.x [32] |

| Corrupted Checkpoint Files | Partial writes from interrupted evolution or disk errors [31] | Verify file exists and size; Try loading earlier checkpoint; Implement checkpoint validation [31] |

| Missing Dependencies | Config files or custom classes not available at load time [31] | Use absolute paths; Ensure all dependencies are imported before loading [31] |

| Path Resolution Issues | Relative paths failing in different working directories [31] | Use absolute paths: checkpoint_path = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), 'neat-checkpoint-50') [31] |

Robust Checkpoint Handling:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Implementation & Configuration

Q: What are the key configuration parameters for controlling CoDeepNEAT evolution?

A: Critical configuration parameters include:

Table: Essential CoDeepNEAT Configuration Parameters

| Category | Parameter | Recommended Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | pop_size |

150-300 | Balances diversity and computational cost [31] |

| Speciation | compatibility_threshold |

2.5-4.0 | Controls species formation and diversity [31] |

| Mutation Rates | conn_add_prob node_add_prob |

0.1-0.3 | Controls network complexity growth [31] |

| Stagnation | max_stagnation species_elitism |

30, 3 | Prevents premature species removal [31] |

| Activation | activation_options |

tanh sigmoid relu |

Provides functional diversity [31] |

Q: How do I visualize evolution progress and results?

A: Use the built-in visualization utilities:

These visualizations show fitness progression over generations, species formation and extinction, and the final evolved network topology [31].

Multiobjective Optimization

Q: How can I implement multiobjective optimization in CoDeepNEAT?

A: CoDeepNEAT extends to multiobjective optimization through Pareto front analysis:

The multiobjective approach evolves networks considering accuracy, complexity, and performance simultaneously, creating Pareto-optimal solutions [33].

Q: What's the difference between single-objective and multiobjective CoDeepNEAT?

A: Key differences include:

Table: Single vs Multiobjective CoDeepNEAT Comparison

| Aspect | Single-Objective | Multiobjective (MCDN) |

|---|---|---|

| Fitness Evaluation | Single scalar fitness value [34] | Multiple objectives measured separately [33] |

| Selection Pressure | Direct fitness comparison [34] | Pareto dominance relationships [33] |

| Solution Output | Single best network [34] | Front of non-dominated solutions [33] |

| Complexity Control | Requires explicit penalty terms [31] | Natural trade-off between objectives [33] |

| Result Analysis | Simple fitness progression [34] | Multi-dimensional Pareto front analysis [33] |

Performance & Scaling

Q: How can I improve CoDeepNEAT performance on complex problems like drug discovery?

A: For complex domains like drug development:

- Modular Architecture: Leverage CoDeepNEAT's blueprint and module co-evolution for building reusable components [34] [33]

- Transfer Learning: Evolve architectures on related problems first, then fine-tune on specific drug targets

- Ensemble Methods: Combine multiple evolved networks for improved robustness and accuracy

- Domain-Specific Initialization: Start with known effective architectures (e.g., CNNs for molecular structure analysis)

Q: What computational resources are required for meaningful CoDeepNEAT experiments?

A: Requirements vary by problem complexity:

Table: Computational Requirements Guide

| Problem Scale | Population Size | Generations | Recommended Resources | Expected Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toy Problems (XOR, MNIST) | 50-100 | 50-100 | Single machine, CPU-only | Hours [35] [36] |

| Research Scale (CIFAR-10, Wikidetox) | 100-300 | 100-500 | Multi-core CPU or single GPU | Days [33] [36] |

| Production Scale (Image Captioning, Drug Discovery) | 300-1000 | 500-2000 | Cloud distributed (AWS, Azure, GCP) with multiple GPUs | Weeks [34] [33] |

The LEAF framework demonstrates cloud-scale CoDeepNEAT implementation with distributed training across multiple nodes [33].

Experimental Protocols

Standard CoDeepNEAT Workflow

CoDeepNEAT Experimental Workflow: The protocol involves initializing separate populations of modules and blueprints, assembling complete networks through combination, evaluating them against multiple objectives, and evolving both populations cooperatively [34] [33].

Multiobjective Optimization Protocol

Objective: Evolve neural architectures that balance prediction accuracy with computational efficiency for drug discovery applications.

Procedure:

- Define Objectives:

- Primary: Classification accuracy on molecular activity prediction

- Secondary: Network complexity (number of parameters)

- Tertiary: Inference speed on target hardware

Initialize Populations:

- Module population: 50-100 individuals

- Blueprint population: 30-50 individuals

- Initial connectivity: Minimal (input-output only)

Evaluation Cycle:

Termination Criteria:

- Maximum generations: 500

- Fitness plateau: <1% improvement in 50 generations

- Target Pareto front coverage achieved

Complexity Control Methodology

Problem: Prevent network bloat while maintaining performance.

Implementation:

- Complexity-Aware Fitness:

- Structural Mutation Balancing:

- Addition rate: Decreases over generations

- Deletion rate: Increases as networks mature

- Crossover: Favors simpler parent when performance equal

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools and Frameworks for CoDeepNEAT Research

| Tool/Framework | Purpose | Implementation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keras-CoDeepNEAT [36] | Reference implementation | Python, Keras, TensorFlow | Academic research, architecture search experiments |

| LEAF Framework [33] | Production-scale evolution | Cloud-distributed (AWS, Azure, GCP) | Large-scale drug discovery, image captioning |

| NEAT-Python [31] [32] | Core NEAT algorithm | Pure Python, standard library | Baseline experiments, educational purposes |

| TensorFlow/Keras [36] | Network training and evaluation | GPU-accelerated deep learning | Performance evaluation of evolved architectures |

| Graphviz [36] | Network visualization | DOT language, pydot | Analysis and publication of evolved topologies |

Software Environment Setup

Minimum Requirements:

Validation Script:

This technical support guide provides researchers with comprehensive troubleshooting and methodology for advancing drug discovery through neuroevolutionary architecture search. The protocols and solutions have been validated across multiple domains from image recognition to complex molecular prediction tasks [34] [33] [37].

This technical support center serves researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals integrating Deep-Learning (DL) guided Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) in their work. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to address common experimental challenges, framed within the broader context of optimizing EAs for deep learning architecture research [13]. The fusion of DL and EA leverages neural networks' pattern recognition to guide evolutionary search, enhancing performance in applications from drug discovery [29] [38] to complex neural architecture design [13].

? Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How can we prevent the neural network guide from overfitting to the evolutionary data? A common challenge is the network overfitting to limited or noisy evolutionary data, failing to generalize. Implement a transfer learning and fine-tuning strategy [23]. Pre-train the network on a broad dataset (e.g., the CEC2014 test suite) to learn general evolutionary patterns. Subsequently, fine-tune it on a small, targeted dataset generated during the algorithm's run. To retain pre-learned knowledge, fix the weights of the initial network layers and only adjust the final layers during fine-tuning [23].

2. Our model fails to generalize to novel protein structures in drug screening. What is wrong? This "generalizability gap" occurs when models rely on structural shortcuts in training data rather than underlying principles. Constrain the model architecture to learn only from the representation of the protein-ligand interaction space (e.g., distance-dependent physicochemical interactions), not the entire 3D structure [39]. Rigorously evaluate by leaving out entire protein superfamilies from training to simulate real-world discovery scenarios [39].

3. The algorithm converges prematurely. How can we improve exploration? Premature convergence indicates an imbalance between exploration and exploitation. Introduce diversity-preserving mechanisms into your EA. In drug discovery screens, modifying the evolutionary protocol to include crossovers between fit molecules and introducing low-similarity fragment mutations enhances exploration of the chemical space [29]. For architecture search, dynamic network growth that adds or removes layers can help escape local optima [19].

4. The training process is computationally too expensive. How can we improve efficiency? Leverage distributed computing frameworks like Apache Spark to parallelize the evolutionary process, especially the fitness evaluation of individuals in the population [40]. Integrate an experience replay buffer to store and reuse high-quality solutions, avoiding redundant fitness evaluations and reducing computation by up to 70% [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Performance of the DL-Guided Operator

- Problem: The neural network operator (NNOP) does not provide useful search directions, leading to worse performance than the standard EA.

- Solution:

- Verify Dataset Quality: The data used to train the guiding network must contain high-quality evolutionary information. Ensure you collect pairs of parent and offspring individuals where the offspring's fitness is better than the parent's [23].

- Check Input Encoding: For problems with variable dimensions, use a fixed-length encoding method. Pad inputs with a placeholder value (e.g., -1) for dimensions smaller than the maximum allowed length [23].

- Adjust Application Rate: The parameter

τcontrols the proportion of individuals evolved by the neural network. Conduct a sensitivity analysis. Research suggests a value of 0.3 can offer a good balance [23].

Issue 2: Ineffective Evolution in Ultra-Large Combinatorial Spaces

- Problem: When screening ultra-large make-on-demand compound libraries (e.g., billions of molecules), the algorithm fails to find high-quality hits.

- Solution:

- Optimize Hyperparameters: Tune the evolutionary protocol. A population size of 200, allowing the top 50 individuals to advance, and running for 30 generations is a robust starting point [29].

- Enhance Protocol Ruggedness: To avoid stagnation, incorporate multiple mutation steps (e.g., switching to low-similarity fragments) and a second round of crossover that includes lower-fitness individuals to promote diversity [29].

- Run Multiple Independent Trials: The algorithm may find different local optima in different runs. Execute multiple runs (e.g., 20) with different random seeds to uncover a diverse set of promising molecules [29].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing an Insights-Infused EA Framework

This methodology details how to build a framework where a neural network extracts and leverages "synthesis insights" from evolutionary data [23].

- Data Collection: During the EA's run, collect tuples of

(parent individual x_g, offspring individual x_{g+1})specifically from cases where the offspring's fitness is better (y_{g+1} < y_gfor minimization) [23]. - Network Selection & Training:

- Use a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) for its ability to capture global data characteristics, especially if problems lack temporal correlations [23].

- Structure the MLP with 8 blocks, each containing 10 layers, to effectively learn from the data [23].

- Train the network using the ADAM optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss [23].

- Self-Evolution Strategy:

- Integration as a Guided Operator: Design a Neural Network-Guided Operator (NNOP) that uses the network's predictions, combined with the current state of the population, to determine promising evolutionary directions [23].

Protocol 2: Directed Protein Evolution with Deep Learning

This protocol, "DeepDE," uses deep learning to guide the directed evolution of proteins for enhanced activity [41].

- Library Design: Construct a compact initial library of protein variants, focusing on triple mutants. This expands the explored sequence space compared to single or double mutants [41].

- Iterative Cycling:

- Test: Experimentally screen the library (approximately 1,000 variants) for the desired activity.

- Learn: Train a deep learning model on the screened variant-activity data.

- Predict: Use the trained model to propose a new set of promising triple mutants for the next round of testing.

- Repetition: Repeat the cycle for multiple rounds (e.g., four), using the model's predictions to focus screening efforts on the most promising regions of the sequence space [41].

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes key quantitative results from documented experiments.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of DL-Guided EAs in Various Applications

| Application Domain | Algorithm / System | Key Performance Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Engineering (GFP) | DeepDE | 74.3-fold increase in activity over 4 rounds, surpassing superfolder GFP [41]. | [41] |

| Drug Discovery (Screening) | REvoLd | Hit rate enrichment improved by factors between 869 and 1,622 compared to random selection [29]. | [29] |

| Big Data Classification | Distributed GA-evolved ANN | ~80% improvement in computational time compared to traditional models [40]. | [40] |

| Complex Control Tasks | ATGEN (GA-evolved NN) | Training time reduced by nearly 70%; over 90% reduction in computation during inference [19]. | [19] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative workflow of a deep-learning guided evolutionary algorithm, integrating elements from the described protocols.

DL-EA Workflow: This diagram shows the integration of a neural network into an evolutionary algorithm's cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

This table lists essential computational tools and their functions for developing and testing DL-guided EAs.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in DL-Guided EA |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta (REvoLd) [29] | Software Suite | Provides a flexible docking protocol (RosettaLigand) integrated with an EA for exploring ultra-large make-on-demand chemical libraries in drug discovery. |

| Apache Spark [40] | Distributed Computing Framework | Enables parallelization and distribution of the genetic algorithm's fitness evaluations, drastically reducing training time for large-scale problems. |

| Enamine REAL Space [29] | Chemical Database | A vast, synthetically accessible combinatorial library of molecules (billions of compounds) used as a search space for evolutionary drug discovery campaigns. |

| CEC Test Suites [23] | Benchmark Problems | Standard sets of optimization functions (e.g., CEC2014, CEC2017) used to train and validate the performance of new EA variants. |

| ATGEN Framework [19] | Evolutionary Algorithm | A GA-based framework that dynamically evolves neural network architectures and parameters, integrating a replay buffer and backpropagation for refinement. |

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our evolutionary algorithm for Neural Architecture Search (NAS) is converging on architectures that are too large and computationally expensive for practical deployment. How can we better constrain model complexity?

A: This is a common challenge where the fitness function over-emphasizes accuracy. Implement a bi-level optimization strategy. In this approach, the upper-level objective explicitly penalizes model complexity, while the lower level focuses on predictive performance.

- Methodology: Formalize this as a bi-level problem [13]:

- Upper Level: Minimizes network complexity (e.g., number of parameters, FLOPs), penalized by the lower-level performance function.

- Lower Level: Optimizes training parameters (weights, biases) to minimize the loss function on the training data.

- Solution: Incorporate a multi-objective fitness function that directly balances accuracy and model size. For instance, one study demonstrated that this method can achieve a 99.66% reduction in model size while maintaining competitive predictive performance (a marginal reduction of no more than 0.99%) [13].

Q2: When using evolutionary strategies to optimize RNNs for sequence tasks, the training is slow and requires large labeled datasets, which are scarce. How can we accelerate learning and reduce data dependency?

A: Integrate Evolutionary Self-Supervised Learning (E-SSL) into your pipeline. This approach uses unlabeled data to learn robust representations before fine-tuning on your specific, labeled task [42].

- Methodology: The process involves two stages [42]:

- Pretext Task: An evolutionary algorithm is used to search for an optimal model architecture or learning strategy. This model is then trained on a "pretext task" that generates its own labels from unlabeled data (e.g., predicting missing parts of the data, contrasting different augmented views of the same sample).

- Downstream Task: The pre-trained model, now featuring useful learned representations, is fine-tuned on your actual, labeled dataset for the final task (e.g., classification or prediction).

- Solution: This hybrid approach leverages vast amounts of unlabeled data to guide the evolutionary search towards architectures that learn more generalizable features, significantly improving data efficiency and robustness [42].

Q3: The evolutionary search process itself is inefficient and generates vast amounts of data that we don't fully utilize. How can we make the evolutionary algorithm smarter?

A: You can implement a Deep-Insights Guided Evolutionary Algorithm. This uses a neural network to learn from the data generated during evolution, extracting patterns to guide the search more effectively [23].

- Methodology: During the evolutionary process, collect pairs of parent and offspring individuals alongside their fitness values. Use this data to train a neural network (like a Multi-Layer Perceptron or MLP) to predict promising evolutionary paths.

- Solution: The trained network acts as a "guide." For a portion of the population in each generation, you can use the network's predictions to generate new candidate solutions, rather than relying solely on traditional crossover and mutation. This allows the algorithm to leverage historical evolutionary data, improving convergence speed and performance on complex problems [23].

Q4: For a project on network traffic classification using CNNs, our model training is slow, and parameter tuning is time-consuming. How can evolutionary algorithms help?

A: Apply a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) based framework to jointly optimize feature selection and model parameters. This automates the tuning process and can enhance both speed and accuracy [43].

- Methodology: Combine an Improved Extreme Learning Machine (IELM) classifier with PSO.

- Use a deep learning-based feature selection mechanism to prioritize relevant input features.

- Simultaneously, use the PSO algorithm to dynamically adapt the model's hidden layer weights and architecture size during training.

- Solution: This co-optimization approach has been shown to achieve high detection accuracy (e.g., 98.756% on network traffic datasets) while maintaining real-time applicability with prediction times of less than 15µs [43].

Summarized Experimental Data

The table below consolidates key quantitative results from recent studies applying evolutionary algorithms to optimize neural networks.

Table 1: Performance of Evolutionary Algorithm-Optimized Neural Networks

| Optimization Method | Application Domain | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Comparative Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Bi-Level NAS (EB-LNAST) [13] | Color Classification & Medical Data (WDBC) | Model Size Reduction | 99.66% reduction | Traditional MLPs |

| Predictive Performance | Within 0.99% of tuned MLPs | Hyperparameter-tuned MLPs | ||

| PSO-Optimized ELM (IELM) [43] | Network Traffic Classification | Detection Accuracy | 98.756% | Traditional ELM & GA-ELM |

| Prediction Latency | < 15μs | Not Specified | ||

| Siamese LSTM + Attention [44] | Duplicate Question Detection (Quora) | Detection Accuracy | 91.6% | Previously established models |

| Performance Improvement | 9% improvement | Siamese LSTM without attention |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evolutionary Bi-Level Neural Architecture Search (EB-LNAST)

This protocol is designed for finding optimal ANN architectures while tightly constraining model complexity [13].

Problem Formulation:

- Upper-Level Objective: Minimize network complexity (e.g., number of neurons, connections), penalized by the lower-level loss.

Upper_Level = Complexity + λ * Lower_Level_Loss - Lower-Level Objective: Minimize the training loss (e.g., Cross-Entropy) by optimizing the network's weights and biases.

- Upper-Level Objective: Minimize network complexity (e.g., number of neurons, connections), penalized by the lower-level loss.

Evolutionary Setup:

- Representation: Encode the neural network architecture (e.g., number of layers, neurons per layer) as an individual in the population.

- Fitness Evaluation: For each individual (architecture): a. Train the network (optimize weights) on the training dataset to fulfill the lower-level objective. b. Evaluate the trained network on a validation set to get its accuracy. c. Calculate the upper-level fitness, which combines the model's complexity and its validation performance.

- Evolution Operators: Use standard selection, crossover, and mutation operators to create a new generation of architectures.

Termination: Repeat for a fixed number of generations or until performance plateaus.

Protocol 2: Evolutionary Self-Supervised Learning (E-SSL) for RNNs

This protocol is suitable for sequence modeling tasks with limited labeled data [42].

Pretext Task Phase (Unsupervised):

- Task Definition: Define a pretext task that does not require human labels. For RNNs on text or time-series data, this could be:

- Next-Step Prediction: Train the RNN to predict the next element in a sequence.

- Masked Input Reconstruction: Randomly mask parts of the input sequence and train the RNN to reconstruct the original.

- Evolutionary Search: Use an evolutionary algorithm to search for optimal RNN hyperparameters (e.g., number of layers, hidden units, type of cell) or even the learning strategy. The fitness is the performance on the pretext task.

- Task Definition: Define a pretext task that does not require human labels. For RNNs on text or time-series data, this could be:

Downstream Task Phase (Supervised Fine-Tuning):

- Initialization: Take the best RNN model and its learned representations from the pretext phase.