Network Co-option vs. De Novo Evolution: Mechanisms, Methodologies, and Biomedical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of two fundamental mechanisms for evolutionary innovation: gene network co-option and de novo gene evolution.

Network Co-option vs. De Novo Evolution: Mechanisms, Methodologies, and Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of two fundamental mechanisms for evolutionary innovation: gene network co-option and de novo gene evolution. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, distinguishing methodologies, and validation frameworks for these processes. By synthesizing recent findings from evolutionary developmental biology and genomics, we clarify how the repurposing of existing genetic circuits contrasts with the emergence of new genes from non-coding DNA. The content addresses critical challenges in distinguishing these mechanisms and discusses their profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms, identifying therapeutic targets, and harnessing evolutionary principles for biomedical innovation.

Defining the Mechanisms: From Molecular Tinkering to Novel Gene Birth

Conceptual Framework: Co-option vs. De Novo Evolution

Definitions and Key Distinctions

What is the fundamental difference between network co-option and de novo gene emergence?

Network co-option involves the repurposing of preexisting genetic circuits for new biological functions, whereas de novo gene emergence describes the origin of entirely new genes from previously non-coding DNA sequences [1]. Co-option leverages established regulatory architectures and component interactions, while de novo evolution creates novel genetic elements lacking detectable homology to existing genes [1].

How can I experimentally distinguish between these two mechanisms in my research?

The distinction requires multiple lines of evidence focusing on sequence homology, phylogenetic distribution, and functional analysis. The table below summarizes the key diagnostic features:

Table 1: Diagnostic Features for Distinguishing Evolutionary Mechanisms

| Diagnostic Feature | Network Co-option | De Novo Gene Emergence |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Homology | Detectable similarity to known genes/circuits [1] | No significant similarity to any known genes [1] |

| Genomic Origin | Derived from pre-existing functional sequences [1] | Emerges from previously non-coding DNA [1] |

| Phylogenetic Distribution | Limited to related species/clades with the source circuit | Often restricted to a specific lineage or species [1] |

| Regulatory Elements | Reuses established promoters and regulatory logic [2] | May lack canonical regulatory regions or evolve new ones |

| Protein Domains | Contains characterized functional domains | Encodes novel protein folds or domains without known homologs [3] |

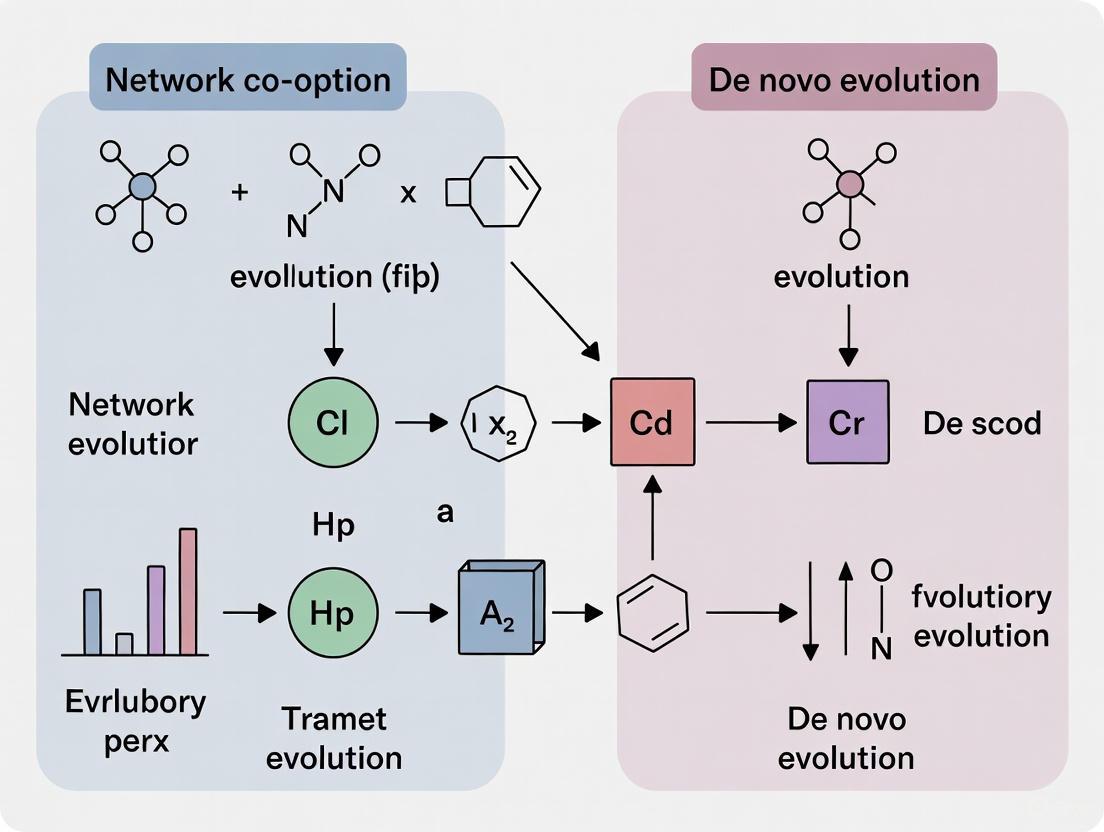

Visualizing the Conceptual Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points for classifying a genetic element as a product of co-option or de novo emergence.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Validating Co-option in a Toxin-Antitoxin System

This protocol is adapted from experimental work using the Evo genomic language model to generate and validate synthetic genetic systems [3].

Objective: To test the function of a predicted toxin-antitoxin (TA) pair generated through a co-option prompting strategy.

Materials:

- Generated toxin (e.g., EvoRelE1) and antitoxin sequences.

- Appropriate bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli).

- Growth media and incubator.

- Expression vectors with inducible promoters.

- Spectrophotometer for OD600 measurements.

Procedure:

- Cloning: Clone the generated toxin and antitoxin genes into separate expression vectors under the control of inducible promoters (e.g., pBAD or pTet).

- Transformation: Co-transform the toxin and antitoxin plasmids into the bacterial host strain.

- Growth Inhibition Assay:

- Inoculate cultures and grow to mid-log phase.

- Induce toxin expression while maintaining repression of the antitoxin.

- Monitor bacterial growth by measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD600) over 4-8 hours.

- Include control cultures where neither gene is induced, and where only the antitoxin is induced.

- Rescue Assay:

- Induce toxin expression and observe growth inhibition.

- After 2 hours, induce antitoxin expression.

- Monitor OD600 to assess recovery of bacterial growth.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate relative survival by comparing the final OD600 of the experimental culture to the non-induced control.

- A functional toxin will show significant growth inhibition (e.g., ~70% reduction), and a functional antitoxin will rescue growth upon its induction [3].

Workflow for Semantic Design of Co-opted Circuits

The diagram below outlines the "semantic design" workflow for generating novel, functional genetic circuits by prompting a genomic language model with contextual information [3].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Design and In Silico Analysis

Q: My generated sequences from the language model show low novelty and are highly similar to known natural sequences. How can I increase diversity?

- A: Adjust the sampling parameters of the model (e.g., increase temperature) to encourage exploration. Employ stricter novelty filters in your post-processing pipeline, requiring lower percentage identity to known sequences in databases like NCBI [3] [1]. Use more diverse or less conserved genomic contexts in your initial prompts.

Q: In silico protein interaction prediction fails to show complex formation for my generated toxin-antitoxin pair. Should I discard these candidates?

- A: Not necessarily. Computational predictions can yield false negatives. If the sequences were generated from a functional context, proceed to low-throughput experimental validation. The interaction interface might be novel and not recognized by standard prediction tools [3].

Experimental Validation

Q: In the growth inhibition assay, I observe no toxicity when the putative toxin is expressed. What are potential causes?

- A:

- Lack of Function: The generated sequence may not encode a functional protein.

- Expression Issue: Verify protein expression via Western blot. Check that the induction system is working correctly.

- Codon Usage: The generated sequence may use codons that are rare in your expression host, impairing translation. Consider codon optimization.

- Target Specificity: The toxin may be specific to a bacterial strain different from your experimental model.

Q: The antitoxin fails to neutralize the toxin in the rescue assay. What could be wrong?

- A:

- Stoichiometry: The expression level of the antitoxin may be insufficient. Titrate the induction level for both toxin and antitoxin.

- Kinetics: The antitoxin might need to be expressed before or concurrently with the toxin to form a complex. Modify the timing of induction.

- Non-specific Interaction: The generated pair may not form a specific, stable complex despite being generated from the same context.

Data Interpretation and Classification

Q: I have a functional genetic element with no homologs in databases. Can I immediately classify it as de novo?

- A: No. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Use comparative genomics across closely related species to confirm the absence of the sequence is not due to gaps in genome sequencing or annotation [1]. Additionally, investigate if the element could be a highly diverged product of an ancient duplication event, which can be misidentified as de novo [1].

Q: How do I demonstrate that a circuit was co-opted rather than evolved de novo?

- A: Provide evidence for the preexisting source. This can include:

- Identifying homologous circuit components in other species with different, ancestral functions.

- Showing that the core regulatory logic (e.g., promoter architecture, transcription factor binding sites) is conserved from a source circuit.

- Demonstrating that the new function relies on molecular interactions (e.g., protein-protein interactions) that existed in the ancestral system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Studying Network Co-option

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Language Models (e.g., Evo) | In-context generation of novel functional sequences by learning multi-gene relationships in prokaryotic genomes [3]. | Evo 1.5 model can perform "genomic autocomplete" and semantic design [3]. |

| Inducible Expression Systems | Controlled, separate induction of genetic circuit components (e.g., toxin and antitoxin) for functional testing [3]. | pBAD (arabinose-inducible), pTet (tetracycline-inducible). |

| Model Organisms | Versatile chassis for cloning and testing the function of synthetic genetic circuits. | Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Salmonella enterica [3]. |

| Sequence Databases | For homology searches and novelty assessment of generated sequences [1]. | NCBI GenBank, RefSeq [1]. |

| Genetic Design Automation (GDA) Tools | In silico design, modeling, and analysis of genetic circuits prior to physical construction [4]. | Cello 2.0 for automated circuit design [4]. |

| Plasmid Repositories | Source of standardized, well-characterized biological parts (promoters, RBS, etc.) for circuit construction. | Addgene repository [4]. |

The study of de novo gene evolution challenges the long-held belief that new genes arise exclusively from pre-existing genes through mechanisms like duplication. Instead, it reveals that genes can originate from scratch, emerging from ancestrally non-coding DNA sequences [5]. This process involves the transformation of non-functional genomic regions into sequences that encode functional proteins or RNAs, which then become integrated into the organism's genetic regulatory networks [6] [7].

For researchers in evolutionary biology and drug development, distinguishing true de novo origination from the co-option of existing network components is a complex task. This technical support center provides targeted guidance, experimental protocols, and data interpretation frameworks to address the specific challenges you may encounter in this emerging field.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the primary challenges in confirming de novo gene origination and how can I address them?

- Challenge 1: Differentiating from unannotated coding sequences.

- Solution: Employ a rigorous comparative genomics pipeline. Compare your candidate gene's genomic locus against closely related species and outgroups. A true de novo gene should have no homologous coding sequence in the ancestral genome, though the non-coding locus will be alignable [5]. Utilize multiple genomic databases to rule out annotation errors.

- Challenge 2: Detecting low or tissue-specific expression.

- Solution: Leverage single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Bulk RNA-seq can mask expression that is restricted to rare cell types. For example, in Drosophila testes, many de novo genes are primarily expressed in spermatocytes [5]. scRNA-seq can precisely identify these specific expression patterns and confirm the gene is not merely transcriptional noise.

- Challenge 3: Demonstrating protein-coding potential and function.

- Solution: Combine mass spectrometry with ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq). A mass spectrometry-first approach can detect peptides translated from previously unannotated open reading frames (ORFs). Corroborate these findings with Ribo-seq data to show that the ORF is actively bound by ribosomes, providing strong evidence of translation [5].

FAQ 2: How can I determine if a de novo gene has been integrated into existing gene regulatory networks?

- Issue: The gene is expressed, but its regulatory basis is unknown.

- Investigation Protocol:

- Identify Cis-Regulatory Elements: Analyze the chromatin accessibility (e.g., via ATAC-seq) around the de novo gene's locus. Look for open chromatin regions and conserved promoter motifs, which may be shared with adjacent, established genes [6].

- Pinpoint Key Transcription Factors (TFs): Apply computational methods to scRNA-seq data to infer which TFs are active in the same cell types where your de novo gene is expressed [7]. Research indicates that only a subset of TFs, such as achintya and vismay in Drosophila, may act as master regulators for many de novo genes [7].

- Perform Functional Validation: Genetically perturb the candidate TFs (e.g., via knockout or knockdown) and use RNA sequencing to observe if the expression of the de novo gene is significantly altered. A linear, dose-dependent response in the de novo gene's expression to TF copy number variation is strong evidence of direct regulation [6].

- Investigation Protocol:

FAQ 3: My experimental validation of a de novo gene's function is inconclusive. What are common pitfalls?

- Pitfall 1: Using an inappropriate phenotypic assay.

- Guidance: Many de novo genes may have subtle, context-specific, or redundant functions. If a standard viability or growth assay shows no effect, consider assays for stress response, competitive fitness, or specific physiological processes relevant to the gene's expression context (e.g., sperm competition for testis-expressed genes) [5].

- Pitfall 2: Overlooking non-coding RNA functions.

- Action: Do not assume the gene functions only at the protein level. Investigate potential roles as a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) or microRNA. Techniques like RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) can help identify if the RNA molecule itself interacts with proteins or other RNAs [3].

- Pitfall 3: Inadequate consideration of genetic background.

- Action: De novo genes can be polymorphic within a population [5]. Ensure you are using a well-characterized strain for functional assays and be aware that the gene's effect might be dependent on the specific genetic background.

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Identification and Validation Using Population Genomics

This protocol is adapted from foundational work in Drosophila to identify de novo genes that are polymorphic within a population [5].

- Sample Preparation: Sequence the genomes and transcriptomes (e.g., from relevant tissues like testes) of multiple strains or individuals from the species of interest.

- Candidate Identification: Map transcripts to the genome and identify transcribed regions that lack homology to annotated genes in the reference genome.

- Comparative Genomics: Align the genomic locus of each candidate to the genomes of closely related species. Filter for sequences where the ORF is present but was non-genic in the common ancestor.

- Expression Analysis: Analyze transcriptomic data to determine expression levels and tissue-specificity. Highly expressed, fixed genes are strong candidates for functional, selected de novo genes [5].

- Validation: Use RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing to confirm the expression and structure of the candidate gene.

Protocol 2: Confirming Protein Coding with Mass Spectrometry

This protocol outlines a method to find evidence of translation for putative de novo genes [5].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a protein extract from tissues or cell types where the candidate gene is highly expressed.

- Mass Spectrometry: Perform tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on the digested protein sample.

- Database Search: Search the mass spectrometry data against a custom database that includes the predicted protein sequences from all candidate de novo ORFs, in addition to the standard annotated proteome.

- Validation: Corroborate peptide identifications with high-stringency filters. Cross-reference hits with ribosome profiling data from the same tissue, if available, to strengthen the evidence for active translation.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key reagents and tools for studying de novo genes.

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Key Application in De Novo Research |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) | Profiling gene expression at single-cell resolution. | Identifying cell-type-specific expression of de novo genes, ruling out transcriptional noise [5]. |

| Custom Mass Spectrometry Database | Identifying peptides from unannotated ORFs. | Detecting protein products of de novo genes that are absent from standard protein databases [5]. |

| BioTapestry Software | Modeling and visualizing Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs). | Mapping the integration of de novo genes into regulatory circuits and modeling their interactions [8]. |

| Genomic Language Models (e.g., Evo) | In silico generation of functional genomic sequences. | Designing novel functional elements and exploring sequence space beyond natural evolution for comparative studies [3]. |

| idopNetworks Framework | Reconstructing personalized, dynamic GRNs. | Modeling how gene-gene interactions, including those with de novo genes, vary among individuals and over time [9]. |

Data Presentation and Workflow Visualization

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Established vs. De Novo Genes

This table helps differentiate de novo genes from traditional genes during analysis.

| Feature | Established Gene | De Novo Gene |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Origin | Modification of pre-existing gene [5] | Ancestrally non-coding DNA [5] |

| Sequence Homology | Detectable across lineages | Limited or none in related species [5] |

| Regulatory Integration | Complex, multi-factor regulation | Often reliant on a few master transcription factors [6] [7] |

| Expression Pattern | Broad or well-defined | Frequently tissue-/cell-type-specific (e.g., testes) [5] |

| Protein Structure | Typically ordered domains | Often disordered, but can become structured [5] |

Workflow Diagram for Distinguishing De Novo Evolution

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for validating a de novo gene, from discovery to functional analysis.

Validation Workflow for De Novo Genes

Regulatory Network Integration Diagram

This diagram illustrates how a de novo gene can be co-regulated with its genomic neighbors, a key concept for distinguishing its integration into the network.

Cis-Regulatory Co-regulation Model

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental conceptual difference between network co-option and de novo network evolution? Network co-option involves the re-deployment of an existing, functional gene regulatory network (GRN) into a new developmental context, space, or time. In contrast, de novo evolution builds new network connections and regulatory relationships from scratch, often through novel genetic mutations [10].

Q2: What are the primary experimental signatures that distinguish a co-opted network? A co-opted network shows immediate, simultaneous recruitment of multiple, interconnected genes in a new context, often upon manipulation of a single upstream "selector" transcription factor. The ectopic expression of this factor recapitulates a significant portion of the original phenotype (e.g., ectopic eye formation from eyeless misexpression) [10]. De novo traits lack this rapid, coordinated redeployment.

Q3: How can phylogenetic analysis help differentiate these evolutionary pathways? For a co-opted trait, deep phylogenetic analysis will reveal that the core GRN components and their regulatory linkages predate the novel trait, having functioned in a different ancestral context. For a de novo trait, the emergence of new regulatory genes and their specific interactions coincides with the origin of the trait itself [10].

Q4: What constitutes conclusive evidence for de novo evolution of a network? Conclusive evidence requires demonstrating that the core regulatory relationships between genes in the network are novel and lack homology to any pre-existing developmental program. This is often supported by the emergence of new regulatory genes and their specific cis-regulatory elements that arose concurrently with the new trait [10].

Q5: Why is the initial loss of tissue specificity a key diagnostic after a co-option event? Following co-option, the cis-regulatory elements (CREs) of the recruited network are activated in both the ancestral and the novel contexts. This immediate expansion of function leads to a loss of specificity and increased pleiotropy, which can be detected via comparative gene expression analyses [10].

Experimental Protocols for Distinction

Protocol 1: Ectopic Misexpression to Test Co-option Potential

Objective: To determine if a candidate "initiator" gene can recruit a putative network to a new developmental location.

Materials:

- Standard laboratory model organism (e.g., Drosophila, zebrafish).

- Molecular cloning reagents for transgenesis.

- GAL4/UAS or equivalent misexpression system.

- Antibodies for immunohistochemistry against key network components.

- RNA probes for in situ hybridization.

Methodology:

- Transgene Construction: Clone the coding sequence of the candidate initiator transcription factor (e.g., Antennapedia, eyeless) under the control of a tissue-specific promoter that is active in a neutral or naive ectopic location.

- Organism Transformation: Generate stable transgenic lines or use transient methods to introduce the construct.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Score the resulting phenotypes for the presence of ectopic structures. A homeotic transformation (e.g., leg forming where an antenna should be) is a strong indicator of wholesale network co-option [10].

- Molecular Validation: Use immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization to document the ectopic activation of downstream genes within the putative co-opted network. The simultaneous recruitment of multiple downstream effectors supports a co-option mechanism.

Protocol 2: Comparative Cis-Regulatory Analysis

Objective: To trace the evolutionary history of network components and their regulation to establish homology.

Materials:

- Genomic DNA from species possessing the novel trait and closely related species that lack it.

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) grade antibodies for key transcription factors.

- Next-generation sequencing facilities.

Methodology:

- CRE Identification: Use chromatin accessibility assays (e.g., ATAC-seq) and ChIP-seq against histone modifications to identify active candidate CREs for key network genes in the tissues of interest.

- Cross-Species Comparison: Compare the sequences and regulatory states of these CREs across species with and without the trait. For a co-opted network, homologous CREs will be active in different tissues across species.

- Functional Testing: Clone candidate CREs from multiple species into reporter constructs (e.g., GFP) and test their activity in the original versus the novel tissue context via transgenesis. A conserved ability to drive expression in the ancestral context, even in species that have evolved a new trait, supports co-option from that ancestral context.

Protocol 3: Network Perturbation and Pleiotropy Mapping

Objective: To quantify the degree of functional independence between a novel trait and its putative ancestral network.

Materials:

- CRISPR/Cas9 or RNAi resources for targeted gene disruption/knockdown.

- Phenotypic imaging and quantification software.

Methodology:

- Node Perturbation: Systematically knock out or knock down key genes within the network in the model organism.

- Phenotypic Scoring: Quantitatively assess the effects on both the novel trait and the ancestral trait where the network originally functioned.

- Pleiotropy Index: Calculate the correlation between phenotypic effects. A high correlation indicates strong pleiotropic constraint, consistent with a recent co-option event where specificity has not yet been restored. A low correlation suggests the network has evolved independence, which can occur over time after the initial co-option [10].

Table 1: Diagnostic Characteristics of Network Evolution Pathways

| Characteristic | Network Co-option | De Novo Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Basis | Change in expression of existing "selector" gene; re-use of existing CREs [10]. | De novo gene birth and/or evolution of novel CREs and transcription factors. |

| Pace of Trait Origin | Rapid (few genetic changes) [10]. | Gradual (accumulation of many mutations). |

| Initial Network Topology | Entire existing sub-circuit recruited wholesale or partially [10]. | New connections formed step-by-step. |

| Phylogenetic Signal | Network components and linkages predate the novel trait [10]. | Network emergence coincides with trait origin. |

| Pleiotropy | Initially high, due to shared CREs [10]. | Initially low, as the network is trait-specific. |

| Ectopic Expression Outcome | Can produce a recognizable, albeit imperfect, ectopic phenotype [10]. | No coherent ectopic phenotype expected. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Application in Distinguishing Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| GAL4/UAS System | Targeted gene misexpression. | Testing sufficiency of a single factor to recruit a network ectopically [10]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Precise gene knockout. | Disrupting network nodes to test necessity and map pleiotropic effects. |

| ChIP-seq Antibodies | Genome-wide mapping of protein-DNA interactions. | Identifying direct regulatory targets and comparing cis-regulatory landscapes. |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq | Profiling gene expression at cellular resolution. | Characterizing network deployment with high specificity in complex tissues. |

| Phylogenetic Footprinting Software | Comparing CREs across species. | Identifying ancient versus newly evolved regulatory sequences. |

Visualization Schematics

Graphviz Diagrams

Evolutionary Origins and Historical Context

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between network co-option and de novo evolution in evolutionary biology?

A1: Network co-option involves the reuse of existing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) in new developmental contexts, while de novo evolution describes the emergence of entirely new genes from previously non-coding DNA sequences. Co-option works with existing genetic "building blocks," whereas de novo evolution creates entirely new genetic elements [11] [5]. Co-option is considered an important mechanism for rapid evolutionary change because it allows complex traits to appear relatively quickly by repurposing existing developmental programs [11] [10].

Q2: What experimental evidence can help distinguish between these two mechanisms when I discover a novel trait?

A2: Several experimental approaches can help distinguish these mechanisms:

- Comparative Genomics: Identify if genes involved in the novel trait have homologs in related species and examine their ancestral functions. Co-opted genes will show sequence similarity and evidence of previous functions [12].

- Expression Analysis: Determine if gene expression patterns associated with the novel trait appear in other developmental contexts in the same organism, which suggests co-option [10] [13].

- Functional Testing: Use techniques like RNAi or CRISPR to disrupt candidate genes and test their necessity in both the novel and potential ancestral contexts [14].

- Regulatory Element Mapping: Identify whether cis-regulatory elements controlling novel trait genes are shared with other traits or are newly evolved [13].

Q3: What are the common methodological challenges in distinguishing co-option from de novo origins?

A3: Key challenges include:

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Difficulty in accurately inferring ancestral gene functions and expression patterns, especially when dealing with deep evolutionary timescales [12].

- Rapid Sequence Divergence: Newly evolved genes may be misclassified as de novo when they actually diverged rapidly from existing genes, obscuring homology [15].

- Transcriptional Noise: Distinguishing functional de novo genes from non-functional transcription of non-coding regions [5] [15].

- Incomplete Genomic Data: Missing data from key transitional species can obscure evolutionary pathways [12].

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconclusive results when testing whether a gene network was co-opted or newly evolved.

Solution: Implement a multi-evidence approach:

- Combine Phylogenetic and Expression Data: Use phylostratigraphy (gene age dating) alongside detailed spatiotemporal expression mapping [15].

- Test Regulatory Elements: Examine whether cis-regulatory elements controlling your candidate genes show evidence of previous functions or are entirely novel [13].

- Assess Network Context: Determine if the gene operates as part of a larger network that appears in other contexts, which would support co-option [10] [16].

Problem: Difficulty determining whether a novel gene is functional or represents transcriptional noise.

Solution: Apply convergent validation:

- Proteomic Validation: Use mass spectrometry to detect protein products [5].

- Ribosome Profiling: Confirm translation through Ribo-seq [15].

- Population Genetics: Test for signatures of selection using dN/dS ratios and population frequency analyses [15].

- Functional Screens: Implement CRISPR/Cas9 knockout experiments to assess phenotypic effects [15].

Key Diagnostic Features Comparison

Table 1: Diagnostic criteria for distinguishing evolutionary mechanisms

| Diagnostic Feature | Network Co-option | De Novo Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Origin | Preexisting genes with ancestral functions | Novel genes from non-coding DNA |

| Regulatory Elements | Often uses existing cis-regulatory elements with modified function | Frequently involves newly evolved regulatory elements |

| Evolutionary Pace | Relatively rapid, leveraging existing complexity | Typically slower, requiring entirely new functional elements |

| Sequence Signatures | High sequence similarity to ancestral genes | Often shorter sequences, lacking conserved domains |

| Network Context | Genes operate in known regulatory networks | Integration into existing networks may be incomplete |

Table 2: Molecular characteristics comparison

| Molecular Characteristic | Co-opted Elements | De Novo Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Length | Typical length for their gene family | Often shorter proteins (<100 amino acids) |

| Protein Structure | Conserved domains and structures present | Frequently lack recognizable domains, higher intrinsic disorder |

| Expression Pattern | Broader expression across multiple tissues | Highly restricted, tissue-specific expression |

| Evolutionary Conservation | Orthologs identifiable in related species | Lineage-specific, lacking clear orthologs |

| GC Content | Typical for conserved genes | Often reduced GC content |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Co-opted Gene Networks

Purpose: To determine whether a novel trait evolved through co-option of existing gene networks.

Methodology:

- Gene Expression Profiling: Perform RNA in situ hybridization or single-cell RNA-seq across multiple tissues and developmental stages [13] [5].

- Comparative Analysis: Compare expression patterns of candidate genes between the novel trait and other body structures.

- Regulatory Element Testing: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to modify candidate cis-regulatory elements and test effects on both the novel trait and potential ancestral expression domains [13].

- Network Mapping: Construct gene regulatory networks using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) or similar methods to identify shared transcription factors [10].

Interpretation: Evidence for co-option includes: 1) Shared expression patterns between novel and ancestral traits, 2) Regulatory elements that function in multiple contexts, and 3) Similar network architecture between traits.

Protocol 2: Validating De Novo Gene Origins

Purpose: To confirm that a candidate gene truly originated de novo from non-coding DNA.

Methodology:

- Phylostratigraphy: Perform systematic BLAST searches against increasingly distant relative species to confirm absence of homologs [15].

- Synteny Analysis: Examine genomic context across related species to confirm non-genic origin [15].

- Transcriptome Validation: Verify expression through RT-PCR, RNA-seq, and Ribo-seq to confirm translation [5] [15].

- Functional Tests: Implement gene knockout (CRISPR/Cas9) and overexpression to assess phenotypic effects [15].

Interpretation: Strong evidence for de novo origin includes: 1) Absence of homologs in sister species, 2) Non-genic ancestral sequence, 3) Translation evidence, and 4) Functional effects on phenotype.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and their applications

| Reagent/Technique | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Gene expression profiling at cellular resolution | Identifying subtle expression patterns suggesting co-option [5] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Targeted genome editing | Testing gene function and regulatory element activity [15] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Protein detection and characterization | Validating translation of putative de novo genes [5] |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) | Mapping transcription factor binding sites | Defining gene regulatory networks [10] |

| Whole-mount in situ Hybridization | Spatial localization of gene expression | Comparing expression patterns across tissues [13] |

| Ribosome Profiling (Ribo-seq) | Monitoring translation | Confirming protein-coding potential [15] |

Conceptual Diagrams

Evolutionary Pathways to Novelty

Experimental Decision Framework

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core difference between evolutionary tinkering and engineering in the context of gene evolution?

Evolution works as a tinkerer, not an engineer. Unlike an engineer who uses blueprints and purpose-selected materials, evolution lacks deliberate intent and works by reusing, combining, and modifying existing genetic parts. This process, termed bricolage, involves the opportunistic rearrangement of available elements, such as through gene duplication and domain shuffling, to create new functions. In contrast, rational engineering is based on foresight and precise planning [17].

Q2: What are the primary molecular mechanisms of evolutionary tinkering?

Molecular tinkering employs several key mechanisms to generate novelty, primarily by recombining existing protein "Lego blocks" [17]. The table below summarizes these core processes.

| Mechanism | Description | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Duplication [17] | Creation of extra gene copies that can acquire new functions. A primary source of genetic raw material. | Generation of gene families and functional diversification. |

| Domain Shuffling [17] | Creation of mosaic proteins through exon shuffling, gene fusion, or fission. | Production of novel proteins with new combinations of functional domains. |

| Alternative Splicing [17] | Generation of multiple mRNA variants from a single gene. | Increases proteome diversity from a finite set of genes. |

| De Novo Gene Birth [6] [5] | Emergence of new protein-coding genes from ancestrally non-genic DNA sequences. | Origin of entirely new genes not derived from pre-existing coding sequences. |

Q3: How can I experimentally distinguish a de novo gene from a missed gene annotation?

This is a common challenge in evolutionary genetics. A robust experimental protocol involves a multi-step validation process to rule out annotation errors and confirm genuine de novo origin. The workflow below outlines the key steps and decision points.

Q4: My analysis suggests a gene network was co-opted. What evidence is needed to support this hypothesis?

Substantiating network co-option requires convergent evidence from multiple lines of inquiry. The table below details the types of data and expected findings for a robust conclusion.

| Evidence Type | Description | Expected Finding for Co-option |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic [5] | Trace the evolutionary history of the network components (genes, regulatory elements). | Network components are ancient, but their coordinated expression in a new context is lineage-specific. |

| Expression [6] [18] | Map gene expression patterns of the network across different tissues, developmental stages, and species. | The same core set of genes is expressed in two distinct developmental or environmental contexts. |

| Regulatory [6] | Identify transcription factors and cis-regulatory elements controlling the network. | Shared regulatory logic (e.g., same transcription factors) controls the network in its old and new contexts. |

| Functional [18] | Test the functional requirement of key network genes in the new context (e.g., via knockouts). | Disruption of core network genes compromises the function of the novel trait. |

Q5: Why is the testes a common site for identifying young de novo genes, and can I find them in other tissues?

The testes of organisms like Drosophila are a hotspot for discovering young de novo genes due to strong sexual selection pressures and potentially less constrained regulatory environments, making it a fertile ground for evolutionary innovation [5]. However, de novo genes are not exclusive to the testes. They have been identified in other contexts, including genes linked to brain development in humans [5]. The choice of tissue should be guided by the biological question, with a focus on tissues under strong selective pressures or those known for rapid evolutionary divergence.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Distinguishing TrueDe NovoGenes from Annotation Artifacts

Problem: A candidate gene appears to be lineage-specific, but you suspect it may be an artifact of poor genome annotation or undetected homology.

Solution: Follow the multi-step experimental protocol outlined in FAQ #3. Key troubleshooting steps include:

- Verify with Multiple Genomic Alignments: Use several high-quality reference genomes from closely and distantly related species. A true de novo gene will have no identifiable coding sequence homolog in the ancestral genomic region.

- Check for Non-Coding Transcripts: Use RNA-seq data from outgroup species to ensure the ancestral locus is not a transcribed but non-coding RNA.

- Assess Protein Evidence: Use mass spectrometry data to confirm the gene is translated. For example, one study used a "mass spectrometry-first, ORF-focused computational approach" to validate nearly 1,000 previously unannotated protein products in Drosophila [5].

Issue 2: Low Confidence in Resolving Plasmid Sequences for Synthetic Biology Constructs

Problem: When using long-read sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore) to verify genetic constructs, the consensus sequence has low-confidence bases, complicating the validation of engineered sequences.

Solution: This is common in regions with specific sequence motifs. The table below lists common sources of error and how to address them.

| Problem Motif | Description | Solution / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Homopolymer Regions [19] | Long stretches of a single nucleotide (e.g., AAAAAA). | ONT is prone to indels here. Low confidence calls in a homopolymer region are expected. Validate with Sanger sequencing if precise length is critical. |

| Dcm Methylation Sites [19] | CC[A/T]GG sequences in the sample. | Errors often occur at the middle base. Be cautious when interpreting variants at these specific sites. |

| Dam Methylation Sites [19] | GATC sequences. | Similar to Dcm sites, these can cause sequencing errors. |

| Low Coverage [19] | Insufficient number of reads covering a base. | Aim for an average coverage of >20x for a highly accurate consensus. Improve DNA sample quality and concentration to yield more reads. |

Issue 3: Differentiating Network Co-option from Parallel Evolution

Problem: You observe similar gene networks functioning in two lineages. It is unclear if this is due to co-option of an ancestral network or independent parallel evolution of similar networks.

Solution: The key is to dissect the evolutionary history of both the components and the regulatory linkages.

- Construct a Detailed Phylogeny: For co-option, the core network genes themselves will be anciently homologous across the lineages. In parallel evolution, the genes themselves may be different but converged on a similar function.

- Analyze cis-Regulatory Elements: This is the most definitive step. If the same non-coding regulatory elements control the network's expression in both lineages, it provides strong evidence for co-option. Parallel evolution would likely involve different regulatory sequences.

- Test Deep Homology: If possible, perform cross-species transgenic experiments. For example, if a regulatory element from one lineage can drive the expression of a reporter gene in the novel context of a second lineage, it supports co-option from a shared, ancestral regulatory capacity [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table details key reagents and their applications for research in evolutionary genetics, specifically for studying de novo genes and network co-option.

| Item | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Custom Oligonucleotides [20] | Chemically synthesized DNA strands for PCR, sequencing, probe generation, and synthetic biology to build and validate genetic constructs. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq Kits | Profiling gene expression at single-cell resolution. Crucial for mapping the precise expression of young de novo genes to specific cell types (e.g., in Drosophila testes) [6] [5]. |

| Model Organism Strains (e.g., D. melanogaster) | Used for genetic manipulation (knock-outs, transgenics) to test the function of candidate de novo genes and manipulated gene networks [5]. |

| Plasmid Sequencing Services | Verification of synthetic DNA constructs. Whole-plasmid sequencing (e.g., via Oxford Nanopore) confirms the integrity of cloned sequences, including de novo gene inserts [19]. |

| Mass Spectrometry Equipment | Validating the translation of de novo genes by detecting their protein products. A key step in moving beyond transcriptional evidence [5]. |

| COBRA Toolbox [21] | A MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis of metabolic networks. Can model how new genes integrate into and affect existing metabolic pathways. |

Detection and Analysis: Experimental and Computational Approaches

Comparative Genomics and Phylogenetic Analysis

FAQs: Common Questions in Phylogenetic Comparative Genomics

Q1: Why is it essential to control for phylogenetic relationships in comparative genomics studies? Closely related species share genes due to common descent, meaning their genomes cannot be treated as independent data points in statistical analyses. Applying phylogeny-based methods accounts for this non-independence. Failure to do so can lead to incorrect biological conclusions, as similarities might be misinterpreted as independent evolutionary events rather than shared ancestry [22].

Q2: What is the difference between a GenBank (GCA) and a RefSeq (GCF) genome assembly? A GenBank (GCA) assembly is an archival record of an assembled genome submitted to an INSDC member (like DDBJ, ENA, or GenBank). A RefSeq (GCF) assembly is an NCBI-derived copy of a GenBank assembly that is maintained and curated by NCBI. RefSeq assemblies always include annotation, and they may not be completely identical to their source GCA assemblies if NCBI has made improvements [23].

Q3: How can I programmatically access genomic data from NCBI without encountering rate limits? The NCBI Datasets API and command-line tools are rate-limited. Without an API key, the default limit is 5 requests per second (rps). Using an NCBI API key increases this limit to 10 rps and helps NCBI monitor and troubleshoot issues more effectively [23].

Q4: My sequencing library yield is low. What are the primary causes? Low library yield can stem from several issues in the preparation process [24]:

| Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality | Enzyme inhibition from contaminants (e.g., salts, phenol) or degraded DNA/RNA. | Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) instead of just absorbance. |

| Fragmentation Issues | Over- or under-fragmentation produces fragments outside the optimal size range for adapters. | Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy) and verify the fragment size distribution. |

| Suboptimal Ligation | Poor ligase performance or incorrect adapter-to-insert ratio reduces library molecules. | Titrate adapter ratios; ensure fresh ligase and optimal reaction conditions. |

| Overly Aggressive Cleanup | Desired fragments are accidentally excluded during purification or size selection. | Adjust bead-to-sample ratios and avoid over-drying beads. |

Q5: What is an "atypical" genome assembly on NCBI? Atypical genomes are those flagged by NCBI for one or more problems relating to assembly quality, unusual size, or other flaws. These can be identified on NCBI pages by a warning icon (a yellow triangle with an exclamation point). Users can typically filter these assemblies out of their search results [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: Sequencing Preparation for Comparative Genomics

Effective sequencing is the foundation of reliable comparative genomics. This guide addresses common failure points.

Problem: High Duplication Rates in Sequencing Data

Failure Signals: Abnormally high levels of PCR duplicates in the sequencing data, leading to reduced library complexity and biased genomic coverage [24].

Root Causes and Solutions:

| Root Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-amplification | Too many PCR cycles during library amplification preferentially amplify a subset of fragments. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; use the minimum cycles necessary for adequate yield. |

| Insufficient Input DNA | Low starting material reduces the initial complexity of the library, making duplicates more likely. | Increase input DNA within the recommended range for the library prep kit. |

| Amplification Bias | Polymerase inefficiency or inhibitors cause uneven amplification across the genome. | Use a high-fidelity polymerase optimized for GC-rich regions; ensure input DNA is clean. |

Problem: Adapter Contamination in Sequences

Failure Signals: A sharp peak around 70-90 base pairs in the electropherogram (BioAnalyzer/TapeStation trace), indicating the presence of adapter dimers [24].

Root Causes and Solutions:

| Root Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Ligation | Adapters ligate to each other instead of the DNA insert due to suboptimal conditions. | Titrate the adapter-to-insert molar ratio to find the optimum; use fresh, active ligase. |

| Ineffective Size Selection | Adapter dimers are not adequately removed before the amplification step. | Optimize bead-based cleanup ratios or use gel electrophoresis for precise size selection. |

| Carryover Contamination | Adapters from a previous reaction contaminate the current one. | Use clean lab practices, including changing gloves and using filtered pipette tips. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Phylogenetically Controlled Analysis of Gene Gain

Objective: To test if the gain of a de novo gene is associated with a specific phenotypic trait while controlling for shared evolutionary history [22].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Identify species with and without the de novo gene of interest from genomic databases. Assemble corresponding phenotypic data.

- Phylogeny Reconstruction: Construct a robust phylogenetic tree for your species set using conserved, single-copy orthologs.

- Character Mapping: Map the presence/absence of the de novo gene and the phenotypic trait onto the tree.

- Statistical Testing: Employ phylogenetically independent contrasts (PIC) or a phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) model to test for a correlation between the gene's presence and the trait, using the tree to account for non-independence.

Protocol 2: Identifying Regulators ofDe NovoGenes

Objective: To identify transcription factors that act as master regulators of newly evolved de novo genes [6].

Methodology:

- Single-Cell Sequencing: Apply single-cell RNA sequencing (e.g., to tissues like the testis in Drosophila where many de novo genes are expressed).

- Computational Inference: Use computational tools to infer transcription factor activity and co-expression networks from the single-cell data.

- Genetic Manipulation: Engineer model organisms (e.g., fruit flies) to have varying copy numbers of the candidate transcription factors.

- Expression Validation: Perform RNA sequencing on the engineered organisms to observe linear shifts in the expression of the de novo genes, confirming the role of the transcription factors.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Phylogenetic Control in Comparative Analysis

De Novo Gene Regulatory Network

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| RefSeq Genome Assemblies (GCF) | Provides NCBI-curated and annotated genomes, serving as a standardized reference for comparative analyses [23]. |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software (e.g., for PIC, PGLS) | Implements statistical models that control for shared evolutionary history, allowing correct inference of evolutionary correlations [22]. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq Kits | Enables the profiling of gene expression at the resolution of individual cells, crucial for identifying rare cell types that express de novo genes [6]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Enzyme Kits | Used for library amplification with minimal error, reducing biases and artifacts in next-generation sequencing (NGS) library preparation [24]. |

| Bead-Based Cleanup Kits | Purifies and size-selects DNA fragments during NGS library prep to remove contaminants like adapter dimers and select the desired insert size [24]. |

Enhancer Mapping and Cis-Regulatory Element Identification

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My luciferase or STARR-seq assay in human cell lines shows unexpectedly high activity from interferon-signaling genes. What is the cause and how can I resolve this?

This is a documented systematic error. Transfection of plasmid DNA into many common human cell lines (e.g., HeLa-S3, GM12878) can trigger an innate immune response, activating the cGAS-STING pathway and inducing type-I interferon (IFN-I) expression. This causes enhancers near interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) to show dominant, false-positive signals [25].

- Solution: Treat cells during transfection with kinase inhibitors to suppress this pathway. Using a combination of the TBK1/IKKε inhibitor BX-795 and the PKR inhibitor C16 has been shown to prevent ISG induction and remove these false-positive enhancer signals without affecting true enhancer activity [25].

Q2: Where in the genome should I look to find the enhancers for my gene of interest, avoiding arbitrary distance limits?

The search space can be narrowed in a principled way using topologically associating domains (TADs). A gene and its enhancers are typically located within the same TAD, a fundamental unit of 3D genome organization. The boundaries of TADs are often conserved across cell types, even if the internal interactions are cell-type-specific [26].

- Solution: Use publicly available Hi-C data from various cell types to delineate the TAD boundaries surrounding your gene. This confines your enhancer search to a specific, functionally relevant genomic interval, which can then be screened for candidate cis-regulatory elements using epigenetic marks [26].

Q3: My reporter assays show conflicting results between plasmid-based systems and genomic context. What could be wrong?

A common issue involves the plasmid backbone itself. In widely used reporter systems (pGL3/4 and STARR-seq), the bacterial origin of replication (ORI) can act as a potent, conflicting core promoter, with most reporter transcripts initiating within the ORI rather than the intended minimal promoter [25].

- Solution: Redesign your plasmid to use the ORI as the core promoter, placing it immediately upstream of the reporter gene and candidate enhancer library. This avoids transcriptional interference from multiple promoters and has been shown to improve signal-to-noise ratios in both luciferase assays and STARR-seq screens [25].

Q4: How can I definitively prove that a candidate sequence is an enhancer for a specific gene, rather than just being in proximity?

Definitive proof requires demonstrating that perturbing the candidate sequence directly affects the expression of the target gene in its native genomic context. The traditional approach of testing for activity on a plasmid is not sufficient to confirm a functional gene-enhancer relationship in vivo [26].

- Solution: Use epigenome editing techniques like CRISPR interference (CRISPRi). By targeting a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to a repressive domain (e.g., KRAB) to the candidate enhancer, you can inactivate it. If this inactivation leads to downregulation of your candidate gene, it provides strong causal evidence for the enhancer-gene link [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Signal or High Background in Enhancer Activity Assays

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Conflicting Core Promoters | Map transcription start sites of reporter transcripts; a high percentage initiating in the plasmid ORI indicates this issue [25]. | Redesign constructs to use the ORI as the single, defined core promoter [25]. |

| Weak or Cell-Type-Inappropriate Enhancer | Check chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) and enhancer marks (H3K27ac, H3K4me1) in your cell type to confirm the element is expected to be active. | Use a positive control enhancer known to be active in your cell type. Consider screening in a different, more relevant cell model. |

| Inefficient Transfection | Measure transfection efficiency with a control plasmid (e.g., GFP reporter). | Optimize transfection protocol (e.g., electroporation parameters, reagent-to-DNA ratio) or use a different delivery method. |

Problem: Difficulty Linking Enhancers to Target Genes

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Search Space Too Large | The candidate enhancer and putative target gene are located in different TADs. | Use Hi-C or other 3D chromatin data to define the TAD containing your enhancer and prioritize genes within it [26]. |

| Lack of Functional Validation | Relying solely on proximity or correlation from chromatin interaction data. | Employ CRISPRi to knock down the enhancer and measure the impact on expression of all candidate genes within the TAD [26]. |

| Sparse Chromatin Contact Data | Individual Hi-C datasets are too sparse to reliably detect long-range or trans-chromosomal contacts [27]. | Use a meta-analytically integrated Hi-C map (meta-Hi-C), which aggregates hundreds of individual experiments to create a high-density contact network with superior power to predict functional relationships [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

This protocol provides a systematic workflow to identify enhancers for a specific gene.

- Delineate the TAD: Use publicly available high-resolution Hi-C data (e.g., from the ENCODE project) for multiple cell types to identify the conserved TAD boundaries that encompass your gene of interest.

- Identify Candidate Enhancers within the TAD: Generate or consult a genome-wide map of putative enhancers for your cell type. This can be done by analyzing ChIP-seq data for histone marks (H3K4me1, H3K27ac) and/or transcription factors, combined with assays for open chromatin (ATAC-seq/DNase-seq). Overlap these putative enhancers with the defined TAD to generate a shortlist of candidate regulatory elements.

- Validate Enhancer-Gene Link by Functional Perturbation: For each candidate enhancer, design sgRNAs to target them with a CRISPRi system (e.g., dCas9-KRAB). Transfert the sgRNAs and dCas9 repressor into your relevant cell type and measure the expression of the target gene using qRT-PCR or RNA-seq. A significant downregulation confirms a functional enhancer-gene relationship.

Workflow for mapping enhancers to a target gene.

This protocol outlines modifications to the STARR-seq method for more reliable enhancer screening in human cells.

- Library Design: Clone your candidate DNA fragments into a plasmid vector where the ORI is used as the core promoter, placed directly upstream of the reporter gene. This removes the conflicting minimal promoter and improves the signal.

- Transfection with Inhibitor Treatment: Transfect the STARR-seq library into your target cells (e.g., HeLa-S3) using your preferred method. Include BX-795 (TBK1/IKKε inhibitor) and C16 (PKR inhibitor) in the culture medium during and after transfection to prevent the IFN-I response.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Proceed with the standard STARR-seq protocol for RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing. Analyze the data, noting that interferon-related false positives should be significantly diminished.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Enhancer Mapping and Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| TBK1/IKKε Inhibitor (BX-795) & PKR Inhibitor (C16) | Suppresses false-positive enhancer signals from innate immune response in plasmid-based assays in human cells [25]. | Critical for STARR-seq and luciferase assays in many common cell lines (e.g., HeLa-S3). |

| ORI-as-Promoter Plasmid Backbone | Provides a single, strong core promoter for reporter assays, eliminating confounding transcription from the plasmid backbone [25]. | Improves signal-to-noise compared to traditional dual-promoter vectors. |

| dCas9-KRAB CRISPRi System | Enables targeted epigenetic silencing of candidate enhancers in their native genomic context to validate gene targets [26]. | Essential for establishing causal enhancer-gene relationships. |

| Meta-Hi-C Chromatin Contact Maps | High-density, aggregated chromatin interaction networks for human, mouse, and fly. Powerful for identifying long-range and trans-chromosomal gene-enhancer connections [27]. | Outperforms individual Hi-C datasets in predicting functional relationships like coexpression. |

| H3K27ac & H3K4me1 Antibodies | For ChIP-seq to map active enhancers and promoters genome-wide. H3K27ac marks active enhancers; H3K4me1 marks poised and active enhancers [28] [26]. | The "peak-valley-peak" pattern in H3K27ac data can help pinpoint the precise nucleosome-depleted enhancer core [26]. |

Data Presentation Tables

Table: Distinguishing Features of Enhancer Evolutionary Origins

| Feature | Network Co-option | De Novo Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | Repurposing of a pre-existing enhancer from another developmental context [29]. | Emergence of a new enhancer from previously non-regulatory DNA [30]. |

| Genomic Origin | Preexisting regulatory sequences, sometimes via transposable elements [29]. | Non-functional, non-coding sequences (e.g., decaying duplicated genes) [30]. |

| Sequence Signature | Often shows sequence conservation with the ancestral enhancer, though binding sites may be gained/lost [29]. | Lineage-specific sequence conservation; may be absent in ancestor [30]. |

| Functional Role | Links a gene into a pre-established regulatory network [31]. | Creates a novel node in the regulatory network, potentially for a new trait [31] [30]. |

| Example | Posterior lobe enhancers in Drosophila genitalia co-opted from posterior spiracle network [29]. | "Recycled Regions" in teleost fish derived from non-coding remnants of duplicated genes [30]. |

Table: Comparison of Chromatin Interaction Mapping Technologies

| Technology | Description | Key Application in Enhancer Mapping | Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hi-C | Unbiased, genome-wide mapping of all chromatin contacts [27]. | Defining TAD boundaries; identifying overall 3D genome structure [26]. | Very sparse for long-range/trans contacts in individual datasets [27]. |

| ChIA-PET | Protein-centric interaction mapping (e.g., Pol2 ChIA-PET) [32]. | Identifying enhancer-promoter interactions mediated by a specific protein. | Broad domains and super enhancers show higher connectivity [32]. |

| Capture Hi-C | Targeted Hi-C focusing on specific genomic regions of interest [27]. | High-resolution mapping of interactions for a pre-defined set of loci (e.g., GWAS hits). | Requires prior knowledge to select target regions. |

| Meta-Hi-C | Computational aggregation of thousands of Hi-C experiments into a single high-density map [27]. | Powerful identification of functional long-range and trans-chromosomal contacts that predict coexpression. | A reference resource that complements, but does not replace, cell-type-specific data [27]. |

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Regulatory Network Inference

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is single-cell RNA sequencing particularly powerful for inferring gene regulatory networks (GRNs) compared to bulk RNA-seq?

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables the measurement of gene expression in thousands of individual cells, providing high-resolution data on cellular heterogeneity. This cell-to-cell variability reveals statistical relationships that can be used to infer regulatory dependencies. While bulk RNA-seq averages expression across cell populations, thus masking underlying heterogeneity, scRNA-seq can identify rare cell populations and trace lineage relationships, making it ideal for reconstructing the GRNs that underlie functional heterogeneity and cell-type specification [33] [34]. Furthermore, scRNA-seq allows for the design of combinatorial perturbation experiments (e.g., Perturb-seq), where mixtures of genetic perturbations can be assayed in a single reaction, providing an efficient means of inferring GRNs [35].

Q2: What are the primary computational methods for inferring gene regulatory networks from scRNA-seq data?

Several computational methods have been developed specifically for GRN inference from single-cell data. Key approaches include:

- The Inferelator: A method based on regression with regularization that infers regulatory relationships between transcription factors (TFs) and target genes. It can incorporate multitask learning and has been successfully applied to scRNA-seq data from budding yeast [35].

- PIDC (Partial Information Decomposition and Context): An algorithm that uses multivariate information theory to explore statistical dependencies between triplets of genes. It identifies regulatory relationships by quantifying how much information two genes provide about a third, which often outperforms pairwise methods [34].

- Bayesian Formulations: Methods like Bayesian Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (bNMF) can be used to infer the depth of cellular heterogeneity and identify subgroup memberships, which is a key step in understanding regulatory complexity [36].

Q3: What are common sources of technical artifacts in scRNA-seq data that can confound network inference?

Technical artifacts that can significantly impact downstream GRN inference include:

- Ambient RNA: Transcripts released from damaged or apoptotic cells that are captured in droplets along with intact cells, contaminating the true gene expression profile [37].

- Doublets/Multiplets: Instances where more than one cell is captured in a single droplet or well, leading to hybrid expression profiles that can be mistaken for novel cell states or incorrect regulatory connections [37] [38].

- Low-Quality Cells: Cells with a high percentage of mitochondrial reads or a low number of detected genes, indicative of broken cells or insufficient mRNA capture [37] [38].

- Batch Effects: Technical variations introduced by differences in sample processing, library preparation, or sequencing runs, which can create spurious correlations and obscure true biological signals [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Ambient RNA Contamination

Symptoms:

- Detection of cell-type-specific marker genes in cell types where they are not expected.

- Generally high background noise in gene expression data.

Solutions:

- Computational Removal: Use specialized tools to estimate and subtract the background ambient RNA profile.

- SoupX: Effectively removes ambient RNA contamination and is less dependent on precise pre-annotation, though it requires some user input regarding marker genes [37].

- CellBender: A tool suited for cleaning up noisy datasets and providing an accurate estimation of background noise, often showing superior performance compared to other tools [37].

- Experimental Optimization: During sample preparation, minimize cell lysis and the generation of free-floating RNA. Use viability staining and dead cell removal protocols to reduce the contribution from dying cells [39] [40].

Problem 2: Excessive Doublet Rates

Symptoms:

- Cells co-expressing well-established marker genes for distinct cell types (e.g., a cell expressing both T-cell and B-cell markers).

- Outlier cells with unusually high UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) counts or numbers of detected genes [37] [38].

Solutions:

- Experimental Adjustment: Avoid overloading cells during library preparation. Refer to platform-specific guidelines (e.g., for 10x Genomics, loading the recommended number of cells is critical to control the multiplet rate) [38].

- Computational Detection and Removal: Employ doublet-detection algorithms, preferably using a combination of tools for robust identification.

- DoubletFinder: Has been shown to outperform other methods in terms of accuracy and its positive impact on downstream analyses like clustering [37].

- Scrublet: A scalable method suitable for large datasets [37].

- It is recommended to use these tools in conjunction with manual inspection of cells co-expressing markers of distinct lineages [37].

Problem 3: Low-Quality Cells Obscuring Biological Signals

Symptoms:

- A large fraction of cells with a low number of total genes or UMIs.

- Cells with a high percentage of reads mapping to mitochondrial genes.

Solutions:

- Apply Quality Control Filters: Filter the cell barcode matrix to remove low-quality cells based on established thresholds. The table below summarizes key metrics and typical filtering criteria, though these should be adjusted based on sample type and biology [37] [38].

Table 1: Quality Control Metrics for Filtering Low-Quality Cells

| Metric | Typical Indicator of Low Quality | Common Filtering Thresholds (Guide Only) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Genes per Cell | Insufficient mRNA capture; empty droplet | Filter cells with gene counts significantly below the distribution median [37]. |

| Total UMI Counts per Cell | Insufficient mRNA capture; empty droplet | Filter cells with UMI counts significantly below the distribution median [37]. |

| Mitochondrial Gene Percentage | Broken or dead cells; cellular stress | Often 5% - 15%, but varies by species and sample type. Highly metabolically active tissues may have higher baseline levels [37] [38]. |

| Stress-Related Gene Signature | Cellular stress from dissociation or handling | Filter cells expressing high levels of pre-defined dissociation or stress-related gene sets [37]. |

- Regress Out Unwanted Variation: During data scaling, regress out factors such as total UMIs per cell and mitochondrial gene percentage to mitigate the impact of these technical confounders on downstream analysis [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools for scRNA-seq GRN Inference

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Products/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Droplet-Based scRNA-seq Platform | High-throughput encapsulation of single cells into droplets for parallel library preparation. | 10x Genomics Chromium, ddSEQ from Bio-Rad, InDrop from 1CellBio [33]. |

| scRNA-seq Kit with UMIs | Facilitates whole-transcriptome analysis from single cells. UMIs enable accurate quantification by correcting for PCR amplification bias. | SMART-Seq kits (Takara Bio) [40], 10x Genomics Chromium Kits [38]. |

| Cell Suspension Buffer | Preserves cell integrity and prevents RNA degradation or interference with reverse transcription. | EDTA-, Mg2+- and Ca2+-free PBS; BD FACS Pre-Sort Buffer [40]. |

| Ambient RNA Removal Tool | Computationally estimates and subtracts background noise from the gene expression matrix. | SoupX, CellBender [37]. |

| Doublet Detection Tool | Identifies and removes multiplets from the dataset to prevent false biological interpretations. | DoubletFinder, Scrublet [37]. |

| GRN Inference Algorithm | Reconstructs regulatory networks from the processed single-cell gene expression matrix. | The Inferelator, PIDC [35] [34]. |

Visualizing the Experimental and Analytical Workflow

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for a scRNA-seq experiment aimed at inferring gene regulatory networks, highlighting key steps from sample preparation to computational analysis.

Diagram 1: scRNA-seq GRN inference workflow.

Applying scRNA-seq to Distinguish Network Co-option from De Novo Evolution

A primary challenge in evolutionary biology is determining whether a novel trait arises from the co-option of an existing gene regulatory network (GRN) or the de novo evolution of new regulatory circuitry. Single-cell RNA sequencing provides a powerful framework to address this question by enabling the detailed comparison of GRNs across species, cell types, and conditions.

Key Analytical Strategies:

- Comparative GRN Reconstruction: By applying GRN inference algorithms (like the Inferelator or PIDC) to scRNA-seq data from homologous tissues or cell types in different species, researchers can identify conserved network motifs. The presence of a conserved core network underlying a novel trait in a derived species strongly suggests co-option [35] [34].

- Mapping Cellular Phylogenies: Single-cell data allows for the inference of lineage trajectories (e.g., via pseudotime analysis). Mapping the activity of inferred GRNs onto these lineages can reveal if a new cell fate is associated with the rewiring of an ancestral developmental pathway (co-option) or the emergence of a unique regulatory program [33].

- Assessing Network Hierarchy: Bayesian model comparison frameworks, such as bNMF, can help determine the "depth of heterogeneity"—the number of distinct cell states or subtypes present in a sample. This can reveal whether a novel cell type is a subtle variant of an existing one (hinting at co-option) or a fundamentally distinct class, which could be consistent with either co-option or de novo evolution, requiring further investigation [36].

Visualizing the Core Evolutionary Question:

The following diagram contrasts the hypotheses of network co-option and de novo evolution, illustrating how scRNA-seq can help distinguish them.

Diagram 2: Co-option vs. de novo evolution.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Correlation Between Omics Layers

Problem: Expected strong correlations between differentially expressed transcripts and their corresponding proteins are not observed in your dataset.

Background: A lack of concordance between transcriptomic and proteomic data is a frequent challenge. This can arise from biological reasons (e.g., post-transcriptional regulation, differing turnover rates) or technical artifacts [41] [42].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Repeat the Experiment: Unless cost or time-prohibitive, repeat the experiment to rule out simple human error or one-off technical failures [43].

- Verify Data Quality and Preprocessing:

- Equipment and Reagents: Check that mass spectrometers and other equipment are properly calibrated. Confirm reagents have been stored correctly and have not degraded [43].

- Normalization and Batch Effects: Apply appropriate normalization techniques (e.g., log-transformation, quantile normalization) to each omics dataset separately. Use batch effect correction tools like ComBat to remove technical variation unrelated to biology [41] [44].

- Check Your Biological Assumptions:

- Time Delays: Consider the temporal relationship between mRNA transcription and protein translation. A time-series experiment may be necessary to capture delayed correlations [42].

- Plausible Biology: The discordance may be biologically real. Re-examine the literature to see if strong transcript-protein correlation is expected for your system and genes of interest [43].

- Start Changing Variables (One at a Time):

Guide 2: Troubleshooting a Multi-Omics Workflow for Biomarker Discovery

Problem: An integrated multi-omics analysis fails to yield a robust, interpretable biomarker signature for distinguishing disease states.

Background: Biomarker discovery requires the fusion of proteomic and metabolomic features to enhance sensitivity and specificity compared to single-omics approaches [44].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm the Experiment Actually Failed:

- Evaluate if the negative result is scientifically plausible. A dim signal could indicate a problem with the protocol, or it could mean the molecular event is not detectable in your sample type [43].

- Ensure Appropriate Controls:

- Include positive controls (e.g., a sample with a known strong disease signature) to confirm your experimental and analytical workflow is capable of detecting a signal [43].

- Refine Data Integration and Modeling:

- Algorithm Selection: If using a machine learning model, try different algorithms (e.g., MOFA2 for factor analysis, mixOmics for multivariate statistics) that may be more suited to your data structure [41] [44].

- Feature Selection: Overly complex models can overfit. Implement stricter feature selection prior to integration to focus on the most meaningful variables [42].

- Validate with Targeted Methods:

- Use targeted proteomics (e.g., PRM) and metabolomics (e.g., NMR) on an independent sample cohort to confirm the validity of biomarkers identified in an untargeted discovery screen [44].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core conceptual difference between network co-option and de novo evolution in the context of multi-omics?

A: Network co-option involves the re-deployment of an existing, functional gene regulatory network (GRN) to a new developmental context (e.g., a different tissue or time). This is observed in multi-omics data as a shared set of interconnected transcripts, proteins, and metabolites across two distinct biological processes. For example, in Drosophila, the larval posterior spiracle GRN was co-opted to the male genitalia, and later to the testis mesoderm [10] [45]. In contrast, de novo evolution typically involves the emergence of new genetic elements or the gradual, independent wiring of new regulatory interactions. Multi-omics signatures would show a unique, context-specific network without strong parallels to other established networks in the organism.

Q2: How can I practically distinguish network co-option from other phenomena using multi-omics data?

A: You can distinguish them through specific analytical approaches on your integrated data [10] [45]:

- Identify Shared regulatory elements: If you have genomic data, check if the same cis-regulatory elements (CREs) control gene expression in both the ancestral and novel contexts. This is a strong indicator of co-option.

- Construct Comparative Networks: Build correlation or co-expression networks (e.g., using WGCNA or xMWAS) for both contexts. Co-option is suggested if you find highly similar network modules (clusters of interconnected genes/proteins/metabolites) in both networks [46] [42].

- Check for "Interlocking": Analyze if changes to the network in one context (e.g., a novel gene expression pattern) are mirrored in the other, even if it provides no selective advantage there. This "interlocking" is a hallmark of recent co-option [45].

Q3: My multi-omics data comes from different sample cohorts (non-matched). Can I still integrate it?

A: Yes, but your choice of integration method is critical. Non-matched samples preclude simultaneous integration methods that require a single data matrix. You must use step-wise (or sequential) integration approaches [41]. In this paradigm, you:

- Analyze each omics dataset independently to generate results (e.g., lists of differentially expressed genes and metabolites).

- Integrate these results in a subsequent step using methods like:

Q4: What are the most common pitfalls in multi-omics sample preparation, and how can I avoid them?

A: The primary challenge is reconciling the different biochemical requirements for extracting macromolecules [44]. Common pitfalls and solutions include:

- Pitfall: Using extraction protocols optimized for one molecule (e.g., RNA) that degrade others (e.g., metabolites).