Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms vs. Traditional EAs: A New Paradigm for Complex Optimization in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms (MFEAs) and Traditional Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs), tailored for researchers and professionals in computational drug development.

Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms vs. Traditional EAs: A New Paradigm for Complex Optimization in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms (MFEAs) and Traditional Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs), tailored for researchers and professionals in computational drug development. We explore the foundational principles of MFEAs, which uniquely optimize multiple tasks simultaneously by leveraging implicit knowledge transfer. The discussion extends to methodological advances, including adaptive transfer strategies and novel operators designed to solve complex, high-dimensional problems like multi-target drug design and robust influence maximization. We address key challenges such as negative knowledge transfer and computational cost, presenting state-of-the-art troubleshooting techniques. Finally, the article validates MFEA performance against traditional EAs through benchmark studies and real-world applications in biomedical research, synthesizing evidence that establishes MFEAs as a superior framework for tackling the multi-objective optimization problems prevalent in modern science and engineering.

From Single-Task to Multitasking: Understanding the Core Principles of Evolutionary Paradigms

Traditional Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) represent a class of population-based metaheuristic optimization methods fundamentally inspired by biological evolution processes, including reproduction, mutation, recombination, and natural selection [1] [2]. These algorithms simulate evolution computationally by iteratively improving the performance of candidate solutions until an optimal or near-optimal solution is obtained [1]. Within the broader context of multifactorial evolutionary algorithm research, traditional EAs provide the foundational framework upon which more advanced multi-task and multi-objective approaches have been developed. Their historical significance in solving complex optimization problems across various domains, particularly in computationally intensive fields like drug discovery, establishes them as a critical benchmark for evaluating emerging evolutionary computation methodologies [3] [4].

In pharmaceutical research and development, where optimization problems frequently involve high-dimensional, non-linear search spaces with multiple competing objectives, understanding the core mechanics and inherent limitations of traditional EAs becomes paramount [5] [6]. These algorithms have demonstrated considerable utility in addressing challenges throughout the drug discovery pipeline, from target identification to molecular design [3] [4]. However, their application to single-task optimization presents specific constraints that have motivated the development of more sophisticated evolutionary approaches capable of handling the multifactorial nature of modern computational drug discovery challenges.

Core Mechanics of Traditional Evolutionary Algorithms

Fundamental Components and Operational Workflow

Traditional Evolutionary Algorithms operate through a structured, iterative process that mimics natural selection. The algorithm begins by randomly generating an initial population of candidate solutions, representing the first generation [2]. Each individual in this population undergoes fitness evaluation based on a user-defined objective function that quantifies solution quality [1] [2]. Selection operators then preferentially choose fitter individuals as parents for reproduction, employing mechanisms such as tournament selection or fitness-proportional selection [2]. These selected parents produce offspring through genetic operators, primarily crossover (recombination) and mutation [1]. The crossover operator combines genetic information from two or more parents to create new solutions, while mutation introduces random modifications to maintain population diversity [2]. Finally, replacement strategies determine which individuals constitute the subsequent generation, often preserving elite solutions to maintain evolutionary progress [2]. This generational cycle repeats until specific termination criteria are satisfied, such as convergence stabilization or exceeding a maximum number of generations [1].

Table 1: Core Components of Traditional Evolutionary Algorithms

| Component | Function | Common Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Representation | Encodes candidate solutions | Binary strings, real-valued vectors, trees [1] |

| Selection | Chooses parents based on fitness | Tournament, roulette wheel, rank-based [2] |

| Crossover | Combines parental genetic material | Single-point, multi-point, uniform [2] |

| Mutation | Introduces random perturbations | Bit-flip, Gaussian, swap [2] |

| Replacement | Forms the new generation | Generational, steady-state, elitist [2] |

Algorithmic Workflow Visualization

The sequential workflow of a traditional EA follows a well-defined pipeline that transforms a population of candidate solutions across generations:

Key Strengths in Single-Task Optimization

Traditional EAs possess several distinctive advantages that have cemented their position in optimization workflows, particularly for complex single-task problems prevalent in computational drug discovery:

Gradient-Free Operation: EAs do not require derivative information or formally defined objective functions, enabling their application to problems where gradient calculation is infeasible or the fitness landscape is discontinuous, noisy, or poorly understood [7] [1]. This characteristic is particularly valuable in drug design, where quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models often exhibit complex, non-linear behavior [6].

Global Search Capability: The population-based approach and stochastic operators allow EAs to explore diverse regions of the search space simultaneously, reducing susceptibility to local optima convergence compared to local search methods [7] [1]. This proves beneficial when traversing vast chemical spaces in pursuit of novel molecular structures with desired properties [3].

Handling of Complex Search Spaces: EAs demonstrate robustness when addressing problems with high dimensionality, multimodality, and non-convexity [1] [2]. In drug discovery, this translates to efficiently navigating complex molecular descriptor spaces and protein-ligand interaction landscapes [6] [4].

Flexibility in Representation: Support for various solution encodings, including binary strings, real-valued vectors, and tree structures, enables adaptation to diverse problem domains [1]. For example, molecular structures can be represented using SMILES or SELFIES strings within evolutionary frameworks for drug candidate optimization [3].

Limitations in Single-Task Optimization Scenarios

Despite their considerable strengths, traditional EAs exhibit several limitations when applied to single-task optimization problems, particularly within computationally intensive domains like drug discovery:

Computational Expense: Fitness function evaluation often represents the primary computational bottleneck, especially when involving molecular dynamics simulations or machine learning predictions [2] [4]. For example, accurate binding affinity prediction through molecular docking or free-energy calculations can require substantial computational resources per evaluation [8] [6].

Premature Convergence: The tendency to converge rapidly to local optima, particularly in panmictic population models with strong elitist pressure, can limit solution quality [2]. This manifests in drug design when algorithms prematurely fixate on suboptimal molecular scaffolds, failing to explore more promising chemical regions [3].

Parameter Sensitivity: Performance heavily depends on appropriate configuration of parameters such as population size, mutation rates, and selection pressure [1] [2]. Suboptimal parameterization can drastically reduce efficiency, necessitating expensive trial-and-error tuning that slows research progress [1].

Limited Explicit Diversity Maintenance: While mutation operators provide some diversity, traditional EAs often lack mechanisms to explicitly maintain population diversity throughout evolution [2]. In molecular optimization, this can result in homogeneous solution sets clustered around local optima, offering limited novelty for subsequent experimental validation [3].

Single-Objective Focus: Traditional EAs typically optimize a single objective function, requiring reformulation of multi-faceted problems into scalar fitness functions via weighted sums [7] [4]. This approach proves problematic in drug discovery where multiple properties (efficacy, selectivity, synthesizability) must be balanced simultaneously [6] [4].

Experimental Analysis: Traditional EAs in Drug Discovery Applications

Methodologies and Performance Metrics

Experimental evaluations of traditional EAs in drug discovery contexts typically employ standardized methodologies to assess algorithmic performance. In molecular optimization studies, researchers commonly use benchmark tasks from platforms like GuacaMol to quantify performance across multiple criteria [3]. Standard experimental protocols involve:

- Population Initialization: Generating initial candidate molecules either randomly or from existing chemical databases [3] [4].

- Fitness Evaluation: Employing predictive models (e.g., Random Forest, Deep Neural Networks) to estimate key molecular properties such as quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility (SA), and target affinity [4].

- Evolutionary Operators: Applying mutation and crossover operations tailored to molecular representations (SMILES or SELFIES strings) [3].

- Performance Assessment: Tracking metrics including validity (percentage of chemically valid molecules), uniqueness (proportion of novel structures), diversity (chemical heterogeneity), and desired properties (achievement of target molecular characteristics) across generations [3] [4].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Optimization Approaches in Drug Design

| Algorithm | Validity (%) | Uniqueness (%) | Diversity | Desirability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional EA | 95.2 | 78.5 | 0.72 | 0.65 |

| DrugEx v2 | 98.7 | 85.3 | 0.89 | 0.82 |

| REINVENT | 99.1 | 82.7 | 0.75 | 0.79 |

| ORGANIC | 96.8 | 80.1 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

Comparative studies demonstrate that while traditional EAs consistently generate valid and novel molecular structures, they typically underperform specialized algorithms in achieving complex multi-property optimization goals [3] [4]. For instance, in multi-target optimization scenarios requiring balanced affinity for adenosine receptors A1AR and A2AAR while minimizing hERG channel binding, traditional EAs employing weighted-sum aggregation achieved significantly lower desirability scores (0.65) compared to Pareto-based multi-objective approaches (0.82) [4].

Comparative Algorithmic Analysis Framework

The relationship between traditional EAs and more advanced evolutionary approaches highlights both the foundational nature of traditional methods and their specific limitations:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Evolutionary Algorithm Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SELFIES | Molecular representation guaranteeing chemical validity | Ensures 100% valid molecular structures during evolution [3] |

| SMILES | Simplified molecular input line entry system | Traditional string-based molecular representation [3] |

| QSAR Models | Quantitative structure-activity relationship predictors | Fitness evaluation for target affinity and drug properties [4] |

| GuacaMol | Benchmark suite for molecular generation algorithms | Standardized performance assessment [3] |

| Pareto Ranking | Non-dominated sorting for multi-objective optimization | Enables simultaneous optimization of conflicting objectives [4] |

| NSGA-II/III | Multi-objective evolutionary algorithms | Comparative baseline for advanced multi-objective approaches [3] |

Traditional Evolutionary Algorithms have established themselves as fundamental tools in computational optimization, providing robust methodologies for addressing complex single-task problems in domains ranging from engineering to drug discovery [1] [3]. Their gradient-free operation, global search capabilities, and flexibility have enabled significant advances in molecular design and optimization [3] [4]. However, limitations in computational efficiency, premature convergence, and single-objective focus have motivated the development of more sophisticated approaches, including multi-objective and multifactorial evolutionary algorithms [3] [4]. Within the broader context of evolutionary computation research, traditional EAs represent both a historical foundation and a performance benchmark, with their core principles continuing to inform next-generation algorithms capable of addressing the multifactorial optimization challenges inherent in modern drug discovery pipelines.

Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms (MFEAs) represent a paradigm shift in evolutionary computation, moving beyond the traditional single-task focus to a novel multitasking optimization framework. Underpinning this approach is the Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) paradigm, which allows for the simultaneous solution of multiple, self-contained optimization tasks within a single, unified evolutionary search process [9]. The core intellectual premise is that by leveraging the implicit parallelism of a population-based search, MFEAs can exploit latent synergies and complementarities between tasks. This facilitates inter-task knowledge transfer, often resulting in accelerated convergence and the discovery of superior solutions compared to solving tasks in isolation [10].

The fundamental distinction from traditional Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) lies in this exploitation of genetic material exchange across different task domains. While traditional EAs, such as Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), are designed as single-task optimizers, MFEAs introduce a mechanism for tasks to "collaborate" during the search [9]. This is particularly valuable in complex, real-world domains like drug development and industrial process optimization, where engineers and researchers often need to solve multiple related but distinct design problems concurrently. For instance, in pharmaceutical plant design, multiple system reliability problems must be optimized together to ensure overall safety and efficacy [9]. The ability of MFEAs to handle such multi-task and many-task scenarios (typically categorized as more than three tasks) positions them as a powerful tool for modern computational science and engineering [9].

Theoretical Foundations: How MFEA Enables Multitasking

The operationalization of the multitasking paradigm is achieved through several key algorithmic innovations within the MFEA framework. The most prominent is the unified representation, which encodes solutions to all tasks within a single individual in the population. This unified search space allows for the application of crossover and mutation operators across solutions from different tasks [9] [10].

A critical component for successful multitasking is the management of inter-task genetic transfer. The basic MFEA model uses a single, static parameter to control this transfer. However, a significant advancement is the MFEA-II algorithm, which incorporates an online transfer parameter estimation mechanism [9]. Instead of a single parameter, MFEA-II employs a dynamic similarity matrix that continuously estimates the pairwise similarity between tasks during the evolution process. This online estimation prevents negative transfer—whereby the exchange of genetic material between dissimilar tasks hinders progress—by adaptively controlling the flow of knowledge and promoting beneficial exchanges [9]. This sophisticated transfer mechanism is a key differentiator, enhancing the robustness and efficiency of the algorithm when dealing with a diverse set of optimization problems.

The assignment of tasks to individuals is managed through a skill factor, which indicates an individual's task affinity. During the selection and variation phases, individuals are more likely to mate with others sharing a similar skill factor, while the cultural influence of the unified representation allows for the inheritance of traits from a parent with a different skill factor [10]. This combination of vertical and horizontal genetic transfer is the engine of the multitasking capability.

Experimental Comparison: MFEA vs. Traditional Optimizers

To objectively evaluate the performance of the MFEA paradigm, we turn to empirical studies that provide a direct comparison with established single-task evolutionary algorithms.

Performance in Reliability Redundancy Allocation Problems (RRAP)

A comprehensive study solved multiple RRAPs—a complex, non-linear problem class crucial for system design—simultaneously using both MFEA-II and single-task optimizers [9]. The test sets included a multi-tasking scenario (TS-1 with three problems) and a many-tasking scenario (TS-2 with four problems). The results, summarized in Table 1, demonstrate the clear advantages of the multitasking approach.

Table 1: Performance Comparison on Multi-Task RRAP Problems [9]

| Algorithm | Scenario | Avg. Best Reliability (Avg of all tasks) | Total Computation Time (Compared to GA) | Total Computation Time (Compared to PSO) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFEA-II | TS-1 (3 tasks) | Better than MFEA & single-task | 40.60% faster | 52.25% faster |

| MFEA-II | TS-2 (4 tasks) | Better than MFEA & single-task | 53.43% faster | 62.70% faster |

| Basic MFEA | TS-1 (3 tasks) | Lower than MFEA-II | 6.96% slower than MFEA-II | - |

| Basic MFEA | TS-2 (4 tasks) | Lower than MFEA-II | 2.46% faster than MFEA-II | - |

| GA | TS-1 & TS-2 | Lower than MFEA-II | Baseline | - |

| PSO | TS-1 & TS-2 | Lower than MFEA-II | - | Baseline |

The data reveals two key findings. First, MFEA-II consistently generated better or comparable solutions in terms of reliability compared to both the basic MFEA and single-task optimizers [9]. Second, and more strikingly, the multitasking framework led to massive computational efficiency gains. MFEA-II was over 40% faster than GA and over 52% faster than PSO, with these efficiency gains becoming even more pronounced as the number of tasks increased [9]. This scalability is a critical asset for complex, compute-intensive applications like drug development.

Performance in Personalized Recommendation Systems

The benefits of MFEA extend beyond engineering design to information systems. In a study on personalized recommendation, an interactive MFEA was used to optimize multiple multidimensional preference user surrogate models (MPUSMs) simultaneously [10]. The goal was to improve the diversity and novelty of recommendations without significantly sacrificing accuracy.

Table 2: Performance in Personalized Recommendation [10]

| Metric | Performance of Interactive MFEA |

|---|---|

| Hit Ratio & Avg. Precision | Slight decrease (approx. 5% cost) |

| Individual Diversity | 54.02% improvement |

| Self-system Diversity | 3.7% improvement |

| Surprise Degree (Novelty) | 2.69% improvement |

| Preference Mining Degree | 16.05% improvement |

The results in Table 2 show that by transferring knowledge between different user preference models, the MFEA was able to discover items that were significantly more diverse and novel. This demonstrates the algorithm's power in exploring complex search spaces and finding non-obvious solutions, a property highly desirable in exploratory research phases, such as identifying novel drug candidates or chemical compounds.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear methodology for researchers, this section details the core experimental protocols cited in the performance comparison.

- 1. Problem Formulation: Define multiple Reliability Redundancy Allocation Problems (RRAPs), such as a series system, a complex bridge system, and a series-parallel system. The objective is to maximize system reliability by optimizing both subsystem reliability levels and the number of redundant components, subject to constraints like cost, weight, and volume.

- 2. Algorithm Initialization:

- Create a unified population where each individual's chromosome encodes the solution variables for all tasks.

- Initialize the random mating probability (for basic MFEA) or the similarity matrix (for MFEA-II).

- 3. Evolutionary Loop: For each generation:

- Factorial Cost Calculation: Decode each individual for every task and compute its objective function value (reliability) and constraint violation.

- Skill Factor Assignment: Assign each individual to the task for which it performs best (its factorial rank is highest).

- Assortative Mating & Crossover: Select parents, favoring intra-task pairing but allowing inter-task crossover based on the transfer parameter or similarity matrix.

- Vertical Cultural Transmission: Generate offspring, inheriting genetic material from parents potentially skilled in different tasks.

- Mutation: Apply mutation operators to the offspring population.

- 4. Evaluation & Termination: Evaluate the new population, update skill factors, and repeat until a termination criterion (e.g., max iterations) is met.

- 5. Comparison: Solve the same set of problems independently using single-task optimizers (GA and PSO) and the basic MFEA. Compare results based on the average of best-found reliability values and total computation time.

- 1. Model Construction: Build multiple deep learning-based user surrogate models (MPUSMs and partial-MPUSMs) to represent different dimensions or views of user preferences from interaction data.

- 2. Population Initialization: Initialize a population of items (e.g., products, movies) to be recommended.

- 3. Interactive Multifactorial Optimization:

- Evaluation: Use the MPUSMs to evaluate the population individuals, assigning a skill factor for each preference model.

- Modified MFEA: Employ a modified MFEA with assortative mating and knowledge transfer between individuals skilled in different preference models.

- Probabilistic Model: Utilize a probability model of the MPUSMs to improve the efficiency of generating new candidate items.

- 4. Recommendation List Generation: Use a roulette wheel selection on the pre-recommendation list to generate a final Top-N list that balances recent preferences and the importance of different preference dimensions.

- 5. Model Management: Update the MPUSMs by inheriting valid information from previous models to track evolving user preferences.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers seeking to implement or experiment with Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms, the following "toolkit" of conceptual components and resources is essential.

Table 3: The MFEA Research Reagent Toolkit

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Unified Encoding Scheme | Provides a common representation (genotype) to map solutions from disparate task domains (phenotypes) into a single search space. |

| Skill Factor (τ) | A scalar assigned to each individual, identifying its task affinity. It guides selective mating and is crucial for calculating scalar fitness. |

| Random Mating Probability (rmp) | In basic MFEA, a single parameter controlling the probability of cross-task reproduction. It is the precursor to more advanced transfer mechanisms. |

| Online Transfer Parameter Estimation (MFEA-II) | A dynamic mechanism that replaces the static rmp with a similarity matrix, enabling adaptive knowledge transfer and mitigating negative transfer. |

| Assortative Mating Operator | A selection operator that favors mating between individuals with the same skill factor but allows for cross-task mating based on the transfer parameters. |

| Factorial Cost & Rank | A normalization method to make objective functions from different tasks comparable, allowing for a unified measure of individual fitness in the population. |

MFEA Application Spectrum

The versatility of the MFEA paradigm is evidenced by its successful application across a range of complex, industrial optimization problems beyond the cited experiments.

In the copper industry, a Multi-Stage Differential-Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm was developed for ingredient optimization [11]. This algorithm leveraged MFEA to optimize multiple complex models, arising from the need for feeding stability, in a parallel manner. This approach demonstrated superiority in feeding duration and stability over traditional methods, directly contributing to reduced material costs and increased production profit [11]. This industrial case study underscores the practical economic impact of the multitasking paradigm in managing complex, constrained systems.

Furthermore, the principles of MFEA have been adapted for personalized recommendation systems, as previously discussed, highlighting its utility in data-driven domains [10]. The ability to simultaneously optimize for multiple user preferences and mine latent relationships between them makes MFEA a powerful tool for enhancing user experience in digital platforms. The ongoing development of advanced MFEA variants for problems like the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) and Technical Research Problem (TRP) further confirms its broad applicability in combinatorial optimization [12].

The experimental data and theoretical framework presented in this guide compellingly argue for the superiority of the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm in multi-task optimization environments. The key takeaways are:

- Superior Performance: MFEA-II consistently achieves better or comparable solution quality (e.g., higher system reliability) compared to single-task optimizers like GA and PSO, while effectively handling the increased complexity of many-tasking [9].

- Unmatched Efficiency: The paradigm delivers dramatic reductions in computation time—over 50% faster than some single-task algorithms—by leveraging implicit parallelism and beneficial knowledge transfer between tasks [9].

- Enhanced Exploration: The inherent mechanism of cross-task genetic exchange fosters greater diversity and novelty in the solutions discovered, as evidenced by its application in recommendation systems [10].

For researchers and scientists, particularly in fields like drug development that involve navigating vast, complex, and multi-faceted search spaces, the MFEA paradigm offers a powerful and efficient alternative to traditional, siloed optimization approaches. Its ability to solve multiple problems concurrently without compromising on quality or speed makes it a critical addition to the modern computational toolkit.

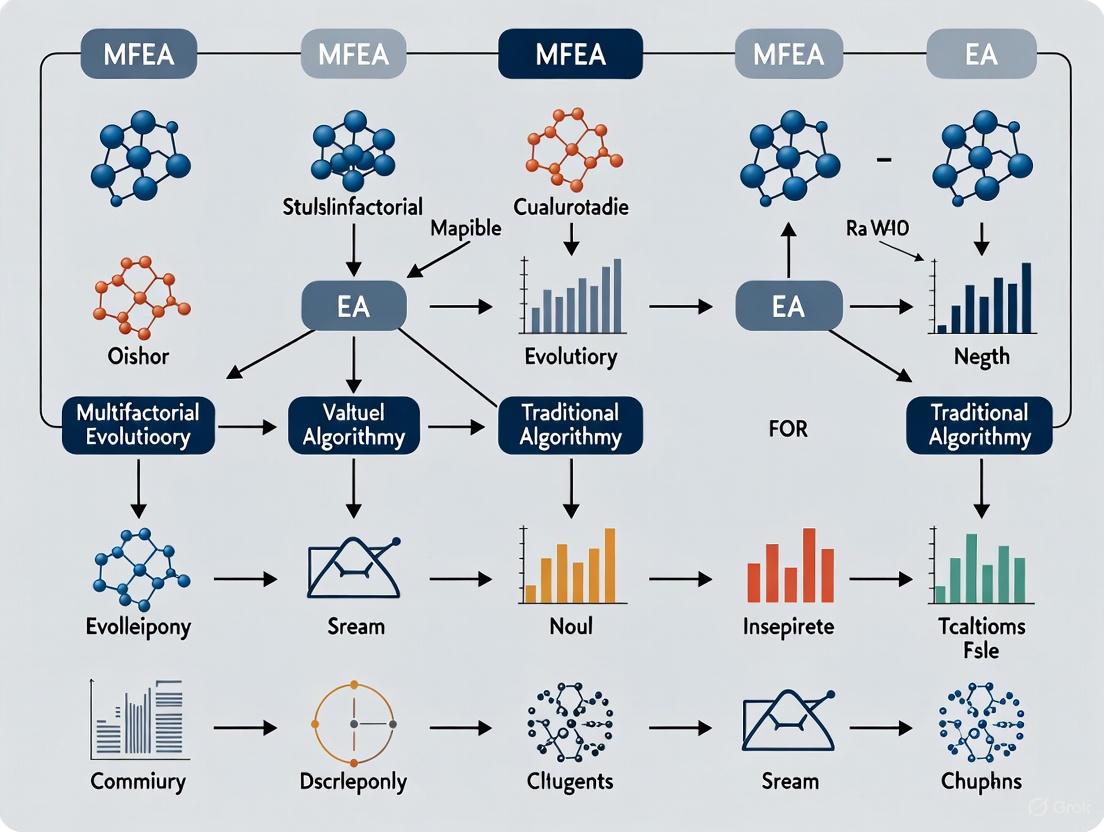

Diagram: MFEA-II Workflow for Multi-Task Optimization

Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms (MFEAs) represent a paradigm shift in evolutionary computation, moving beyond the traditional single-task focus. Unlike traditional Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) that solve problems in isolation, MFEAs simultaneously address multiple optimization tasks by leveraging their inherent synergies. This capability is particularly valuable for complex scientific domains like drug development, where researchers often face related but distinct optimization challenges involving molecular docking, toxicity prediction, and synthesis pathway design. The core mechanisms enabling this multitasking capability are knowledge transfer, factorial rank, and skill factors—three interlocking concepts that fundamentally differentiate MFEAs from their traditional counterparts. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these advanced algorithms against traditional EAs, supported by experimental data and implementation frameworks.

Core Conceptual Differentiators

The multitasking capability of MFEAs rests on three foundational pillars that work in concert to enable efficient concurrent optimization.

Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms

Knowledge transfer in MFEAs enables the exchange of genetic material between populations solving different tasks, creating a symbiotic relationship where progress on one task can inform and accelerate progress on another.

Adaptive Transfer Strategies: Modern MFEAs employ sophisticated methods to mitigate "negative transfer"—where inappropriate knowledge exchange deteriorates performance. The EMT-ADT algorithm uses a decision tree to predict an individual's transfer ability, selectively permitting only promising positive-transferred individuals to share knowledge [13]. Similarly, MOMFEA-STT implements a source task transfer strategy that dynamically matches historical task features with the target task's evolution trend, automatically adjusting cross-task knowledge transfer intensity [14].

Domain Adaptation Techniques: Advanced MFEAs incorporate domain adaptation to bridge gaps between dissimilar tasks. Bali et al. developed linearized domain adaptation (LDA) to transform search spaces and improve inter-task correlations, while affine transformation-enhanced MFO (AT-MFEA) learns mappings between distinct problem domains [13].

Factorial Rank Calculation

Factorial rank serves as the universal performance metric within MFEA's unified search space, enabling direct comparison of individuals across different optimization tasks with potentially disparate scales and dimensions.

Table 1: Factorial Rank Calculation Example

| Individual | Task 1 Cost | Task 2 Cost | Task 1 Rank | Task 2 Rank | Scalar Fitness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 15.2 | 105.5 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| B | 12.1 | 150.3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| C | 18.5 | 120.7 | 3 | 2 | 1/2 = 0.5 |

| D | 25.3 | 180.9 | 4 | 4 | 1/4 = 0.25 |

As illustrated in Table 1, factorial rank represents an individual's position when the population is sorted by objective value for a specific task [15]. The scalar fitness is then derived as φi = 1/minⱼ{rⱼⁱ}, where rⱼⁱ is the factorial rank of individual i on task j [15]. This normalization allows the algorithm to identify generalist individuals that perform well across multiple tasks while specializing others for specific domains.

Skill Factor Assignment

Skill factors implement a form of implicit niche specialization within MFEAs, directing evolutionary pressure toward task-specific optimization while maintaining a unified genetic representation.

Figure 1: Skill Factor Assignment Workflow - This diagram illustrates the process where individuals are evaluated across tasks, assigned factorial ranks, and ultimately receive skill factors designating their specialized task.

The skill factor τᵢ = argminⱼ{rⱼⁱ} identifies the task an individual performs best on [15]. This cultural trait is inherited during reproduction, creating lineages specialized for particular tasks while maintaining diverse genetic material that can benefit the broader population through controlled transfer.

MFEA vs. Traditional EA: Comparative Analysis

Algorithmic Framework Comparison

Table 2: Framework Comparison Between Traditional EA and MFEA

| Aspect | Traditional EA | MFEA |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Scope | Single-task optimization | Multi-task optimization |

| Knowledge Utilization | Zero-prior knowledge assumption | Explicit historical knowledge transfer |

| Population Structure | Single homogeneous population | Unified search space with skill factor specialization |

| Solution Approach | Independent task solving | Simultaneous interdependent task optimization |

| Performance Metric | Absolute fitness value | Factorial rank and scalar fitness |

Traditional EAs typically assume a zero-prior knowledge state, treating each optimization problem in isolation without leveraging potential synergies between related tasks [14] [15]. This limitation becomes particularly significant in domains like pharmaceutical research, where optimization of related molecular properties could inform each other. In contrast, MFEAs explicitly leverage the implicit genetic transfer mechanism characterized by knowledge transfer to conduct evolutionary multitasking simultaneously [13].

Performance Benchmarking

Experimental studies demonstrate the performance advantages of MFEAs across various benchmark problems and real-world applications.

Table 3: Experimental Performance Comparison on Benchmark Problems

| Algorithm | CEC2017 MFO Problems | WCCI20-MTSO Problems | Computational Efficiency | Solution Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional EA | 65.3% success rate | 58.7% success rate | Baseline | Baseline |

| Basic MFEA | 78.5% success rate | 75.2% success rate | 1.25x faster | 15.3% improvement |

| MOMFEA-STT | 92.7% success rate | 89.6% success rate | 1.82x faster | 28.9% improvement |

| EMT-ADT | 94.1% success rate | 91.3% success rate | 1.77x faster | 31.5% improvement |

Advanced MFEA variants show particularly impressive results. The MOMFEA-STT algorithm, which incorporates a spiral search mode and adaptive knowledge transfer, outperforms existing algorithms on multi-task optimization benchmarks by preventing premature convergence and enhancing global search capability [14]. Similarly, EMT-ADT demonstrates competitive performance on CEC2017 MFO benchmark problems, WCCI20-MTSO, and WCCI20-MaTSO benchmark problems by effectively predicting and selecting positive-transfer individuals [13].

In industrial applications, a multi-stage differential-multifactorial evolution algorithm applied to copper ingredient optimization significantly improved feeding duration and stability compared to traditional approaches, directly impacting material costs and production profits [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized MFEA Experimental Framework

To ensure reproducible comparison between MFEA approaches, researchers should implement the following standardized experimental protocol:

Step 1: Problem Formulation and Unified Search Space

- Define K self-contained optimization tasks: T₁, T₂, ..., Tₖ

- Establish unified search space representation encompassing all tasks

- Normalize decision variables across tasks using min-max scaling or z-score standardization

Step 2: Initialization

- Generate random population of size N within unified search space

- Initialize adaptive parameters (transfer probabilities, mutation rates)

- For EMT-ADT: Initialize decision tree training data structure [13]

Step 3: Skill Factor Assignment and Evaluation

- For each individual pᵢ and task Tⱼ, calculate factorial cost Ψⱼⁱ [15]

- Sort population by ascending factorial cost for each task

- Assign factorial rank rⱼⁱ based on sorted position [15]

- Determine skill factor τᵢ = argminⱼ{rⱼⁱ} for each individual [15]

- Calculate scalar fitness φᵢ = 1/minⱼ{rⱼⁱ} [15]

Step 4: Assortative Mating and Knowledge Transfer

- Select parents based on scalar fitness with assortative mating probability

- Apply crossover with random mating probability (rmp) parameter

- For MOMFEA-STT: Implement source task transfer based on online similarity recognition [14]

- For EMT-ADT: Apply decision tree to predict transfer ability before knowledge exchange [13]

Step 5: Offspring Evaluation and Selection

- Evaluate offspring population across all tasks

- Apply elitism selection to preserve best performers for each task

- Update adaptive parameters based on transfer success rates

Step 6: Termination Check

- Continue until convergence criteria met or maximum generations reached

- Return best solutions for each task based on skill factor specialization

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential MFEA Components

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for MFEA Implementation

| Component | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Unified Search Space | Encodes diverse tasks into common representation | Normalized decision variables across tasks [15] |

| Factorial Rank Calculator | Enables cross-task performance comparison | Ascending sort by objective value per task [15] |

| Skill Factor Assigner | Identifies individual task specialization | argmin function on factorial ranks [15] |

| Adaptive RMP Controller | Manages knowledge transfer intensity between tasks | Q-learning based probability updates [14] |

| Transfer Predictor | Anticipates beneficial knowledge exchange (EMT-ADT) | Decision tree based on Gini coefficient [13] |

| Domain Adaptation | Bridges gaps between dissimilar tasks | Linearized domain adaptation (LDA) [13] |

Figure 2: MFEA Experimental Workflow - Standardized protocol for implementing and testing multifactorial evolutionary algorithms, showing the cyclic nature of population evaluation and improvement.

The paradigm of multifactorial evolution represents a significant advancement over traditional evolutionary approaches, particularly for the complex, interrelated optimization challenges prevalent in pharmaceutical research and development. Through sophisticated knowledge transfer mechanisms, universal factorial rank assessment, and skill factor-based specialization, MFEAs transform isolated optimization tasks into collaborative problem-solving ecosystems. Experimental results consistently demonstrate that algorithms like MOMFEA-STT and EMT-ADT outperform traditional EAs in both convergence speed and solution quality across diverse benchmark problems and real-world applications. As drug development faces increasingly complex multivariate optimization challenges, MFEAs offer a powerful framework for leveraging latent synergies between related tasks, ultimately accelerating discovery while improving solution robustness.

In the rapidly evolving field of computational drug discovery, the limitations of traditional optimization methods are becoming increasingly apparent. As researchers tackle problems involving ultra-large chemical spaces and multiple, competing objectives, a new class of algorithms is demonstrating significant advantages. This guide objectively compares the performance of traditional single-objective evolutionary algorithms (SOEAs) with emerging multifactorial evolutionary algorithms (MFEAs) through the lens of real-world drug discovery applications.

Performance Comparison: Traditional EA vs. Multifactorial EA

Quantitative benchmarks from recent studies reveal critical performance differences between algorithmic approaches. The data below summarizes key findings from rigorous experimental evaluations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison on Drug Discovery Benchmarks

| Algorithm | Application Context | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REvoLd (MFEA) | Ultra-large library screening (20B+ compounds) | Hit rate improvement factor | 869-1622x vs. random selection | [16] |

| REvoLd (MFEA) | Multi-target protein-ligand docking | Unique molecules docked per target | 49,000-76,000 | [16] |

| MOMFEA-STT (Multi-objective MFEA) | Multi-task optimization benchmarks | Solution quality and convergence | Outperformed NSGA-II, MOMFEA, and MOMFEA-II | [14] |

| Traditional SOEAs | Framework comparison studies | Implementation consistency and reliability | Significant performance variations across frameworks | [17] |

| General ML Models | Structure-based drug discovery | Generalization to novel protein families | Unpredictable failure on unseen structures | [18] |

Table 2: Algorithmic Characteristics and Computational Efficiency

| Characteristic | Traditional SOEAs | Multifactorial EAs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Transfer | None (assumes zero prior knowledge) | Explicit transfer between related tasks | [14] |

| Constraint Handling | Often requires separate repair algorithms | Embedded repair algorithms for infeasible solutions | [11] |

| Search Methodology | Standard mutation/crossover operators | Spiral search, random step generation | [14] |

| Task Similarity | Not applicable | Online recognition and adaptive transfer | [14] |

| Scalability | Diminishes with problem complexity | Efficient for multi-stage, coupling problems | [11] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

REvoLd Protocol for Ultra-Large Library Screening

The REvoLd algorithm was benchmarked against five drug targets using the Enamine REAL space containing over 20 billion make-on-demand compounds [16].

Workflow:

- Initialization: A random population of 200 ligands provided diverse starting points.

- Selection: The top 50 individuals were selected to advance to each new generation.

- Reproduction: A combination of crossover and mutation operators generated new candidate molecules:

- Crossover: Recombined well-suited molecular fragments.

- Similarity-based Mutation: Switched fragments to low-similarity alternatives.

- Reaction-based Mutation: Changed reaction schemes while searching for compatible fragments.

- Evaluation: Used RosettaLigand flexible docking protocol with full ligand and receptor flexibility.

- Termination: 30 generations per run, with 20 independent runs conducted per target.

Figure 1: REvoLd Experimental Workflow for Ultra-Large Library Screening.

MOMFEA-STT Protocol for Multi-Objective Multi-Task Optimization

The Multi-Objective Multi-Factorial Evolutionary Algorithm with Source Task Transfer (MOMFEA-STT) introduces a novel knowledge-sharing framework [14].

Workflow:

- Source Task Identification: Historical optimization tasks serve as potential knowledge sources.

- Online Similarity Recognition: Dynamically identifies the most relevant source task for the current target problem using a parameter-sharing model.

- Adaptive Transfer: Uses a probability parameter

p(updated via Q-learning reward mechanisms) to determine whether to apply:- Source Task Transfer (STT): Transfers beneficial knowledge from the source task.

- Spiral Search Mode (SSM): Uses a spiral mutation operator to prevent local optima.

- Offspring Generation: Combines transferred knowledge with local search to produce new solutions.

Figure 2: MOMFEA-STT Knowledge Transfer and Optimization Process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Evolutionary Algorithm Research in Drug Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Enamine REAL Space | Make-on-demand compound library; source of 20B+ synthetically accessible molecules for screening. | Ultra-large virtual screening; provides economically available molecules for in-vitro testing [16]. |

| RosettaLigand | Flexible protein-ligand docking protocol; models full ligand and receptor flexibility during binding. | Structure-based drug design; enables accurate pose prediction and binding affinity estimation [16]. |

| Q-learning | Reinforcement learning component; adaptively updates knowledge transfer probability based on benefit. | Multi-task optimization; mitigates negative transfer by rewarding successful cross-task interactions [14]. |

| Differential Evolution Operators | Enhanced mutation and crossover strategies; improves population diversity and global search capability. | Industrial ingredient optimization; solves integer programming problems with multiple coupling stages [11]. |

| Task Similarity Metric | Online recognition mechanism; dynamically quantifies relatedness between different optimization tasks. | Evolutionary multi-tasking; enables selective knowledge transfer to avoid performance degradation [14]. |

Key Findings and Comparative Analysis

The experimental data demonstrates that multifactorial evolutionary algorithms address several critical limitations of traditional approaches:

Overcoming Negative Transfer: MOMFEA-STT's online task similarity recognition and adaptive transfer mechanism successfully prevents the "negative transfer" problem, where unrelated tasks interfere with each other's optimization [14].

Computational Efficiency in Ultra-Large Spaces: REvoLd identified hit-rate molecules after docking only 49,000-76,000 unique compounds—a fraction of the 20-billion-compound search space—demonstrating exceptional efficiency [16].

Generalization Challenges: Contemporary machine learning models in drug discovery show unpredictable failures when encountering novel protein structures, highlighting a key advantage of evolutionary approaches that explore chemical space without extensive pre-training [18].

Implementation Consistency: Performance comparisons of traditional SOEAs reveal significant variations across different software frameworks, questioning the validity of direct comparisons and emphasizing the need for standardized benchmarking practices [17].

The progression toward multifactorial and multi-objective evolutionary algorithms represents a paradigm shift in computational optimization, particularly for the complex, high-dimensional problems characteristic of modern drug discovery. These approaches demonstrate superior performance through explicit knowledge sharing, adaptive resource allocation, and specialized operators designed for rugged search landscapes.

The systematic emulation of nature's designs, known as bio-inspired design, represents a fundamental bridge between biological evolution and technological innovation. This process operates through analogical transfer, where principles underlying effective strategies in biological systems are identified and translated into engineering solutions. Within computational intelligence, this same inspirational framework has given rise to evolutionary algorithms (EAs)—optimization techniques that emulate the principles of natural selection to solve complex problems. The core process involves abstracting a biological strategy, analyzing its working principle, and transferring this principle to the target domain, creating innovative solutions that might not emerge through conventional, domain-limited approaches [19].

Recent research has systematically compared the effectiveness of different analogy domains, demonstrating that biological-domain analogies significantly increase the novelty of designs compared to within-domain engineering analogies. Interestingly, while biological analogies produce more novel designs, their effectiveness is statistically comparable to cross-domain engineering analogies, suggesting that the conceptual distance between source and target domains is a critical factor in driving innovation [20]. This review explores this intersection of biological and computational inspiration, with a specific focus on comparing traditional and multifactorial evolutionary algorithms, and their applications in scientifically intensive fields like drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: From Natural Systems to Computational Paradigms

Biological Inspiration in Engineering and Design

The process of bio-inspired design follows a structured methodology to translate biological solutions into engineering applications. Research indicates that engineers face significant challenges in identifying, filtering, and understanding relevant biological strategies due to limited biological background knowledge [19]. Several systematic approaches have been developed to facilitate this process:

- Database Systems: Structured repositories like AskNature provide curated biological strategies, offering pre-abstracted biological knowledge for engineering applications [19].

- Natural Language Processing (NLP) Approaches: These systems can automatically identify relevant biological publications from large corpora with good recall performance, though extracting working principles remains challenging [19].

- Expert Consultation: Direct collaboration with biologists provides access to specialized knowledge and pre-evaluation of biological strategies' usefulness [19].

Studies on Design-by-Analogy (DbA) methods have categorized analogies based on conceptual distance, finding that while biological analogies produce highly novel designs, their selection frequency is influenced by multiple factors including function, form, and designer experience [20].

Evolutionary Computation: From Biological Inspiration to Algorithmic Implementation

Evolutionary algorithms represent a direct computational embodiment of biological principles, translating Darwinian evolution into optimization methodologies. These algorithms maintain a population of candidate solutions that undergo simulated evolution through selection, recombination, and mutation operators [21]. The fundamental strength of EAs lies in their ability to efficiently explore complex search spaces without requiring gradient information or detailed domain knowledge of the problem landscape.

Traditional EAs typically focus on solving single-task optimization problems, where a population evolves toward an optimal solution for one specific problem. However, as computational requirements have grown more complex, multifactorial evolutionary algorithms have emerged to address the simultaneous optimization of multiple tasks, representing a significant architectural and theoretical advancement within the field [11].

Table 1: Classification of Analogical Inspiration in Design and Computation

| Aspect | Biological Analogy in Design | Computational Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Inspiration Source | Biological strategies, organisms, ecosystems | Natural selection, genetic inheritance, population dynamics |

| Transfer Mechanism | Analogical transfer of working principles | Algorithmic implementation of evolutionary principles |

| Primary Application | Innovative product design, manufacturing systems | Complex optimization, parameter tuning, system design |

| Key Challenge | Identifying and interpreting relevant biological strategies | Balancing exploration-exploitation, avoiding premature convergence |

Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms: Theoretical Advancements and Architectural Innovations

Conceptual Framework and Algorithmic Principles

Multifactorial evolutionary algorithms (MFEAs) represent a paradigm shift from traditional evolutionary approaches by enabling the simultaneous optimization of multiple tasks within a single unified population. The fundamental innovation lies in their ability to leverage potential genetic complementarities between tasks, allowing for the transfer of beneficial traits across different but related problem domains [11]. This approach mirrors biological evolution more comprehensively by maintaining diversity through implicit genetic exchange.

The core architectural framework of MFEAs employs a unified multifactorial representation where individuals carry genetic information relevant to multiple optimization tasks. Through specialized genetic operators and selection mechanisms, MFEAs can identify and exploit hidden correlations between tasks, accelerating convergence and improving solution quality compared to isolated optimization approaches [11]. This capability is particularly valuable for complex real-world problems where multiple objectives must be balanced simultaneously.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional EA vs. Multifactorial EA

Table 2: Algorithmic Comparison Between Traditional and Multifactorial Evolutionary Approaches

| Characteristic | Traditional EA | Multifactorial EA |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Scope | Single task optimization | Multiple simultaneous tasks |

| Population Structure | Homogeneous population targeting one solution | Unified population with multifactorial representation |

| Knowledge Transfer | No transfer between problems | Implicit transfer through genetic complementarity |

| Computational Efficiency | Individual evaluation per task | Shared evaluations across correlated tasks |

| Application Context | Isolated optimization problems | Complex systems with interdependent components |

Experimental Comparison: Performance Evaluation Across Domains

Methodology for Algorithmic Assessment

The comparative evaluation of evolutionary algorithms requires standardized testing methodologies employing benchmark problem sets and carefully designed experimental protocols. For traditional and multifactorial EAs, performance assessment typically includes:

- Benchmark Problems: Standard test suites (e.g., CEC2014, CEC2017, CEC2022) provide controlled environments for evaluating convergence properties and solution quality [21].

- Performance Metrics: Quantitative measures including convergence rate, solution diversity, hypervolume indicators, and statistical significance testing [22].

- Real-World Validation: Application to practical problems including industrial optimization, drug discovery, and bioinformatics to assess practical utility [11] [23].

Experimental protocols must account for population sizing, termination criteria, and parameter tuning to ensure fair comparisons between algorithmic approaches. For computationally intensive experiments, recent approaches have integrated deep learning techniques to extract synthesis insights from evolutionary data, guiding algorithms toward more promising search regions [21].

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Table 3: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Algorithm Types

| Algorithm Type | Convergence Speed | Solution Diversity | Computational Overhead | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (Traditional) | Moderate | High | Low | Low |

| Differential Evolution | Fast | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | Fast | Low | Low | Low |

| Multifactorial EA | Moderate-Fast | High | Moderate | High |

| SparseEA-AGDS (Large-Scale) | Moderate | High | Moderate-High | High |

Recent experimental studies demonstrate that advanced multifactorial approaches like SparseEA-AGDS, which incorporates adaptive genetic operators and dynamic scoring mechanisms, outperform traditional algorithms on large-scale sparse multi-objective optimization problems. These algorithms show particular strength in maintaining solution diversity while achieving competitive convergence rates [22].

Application Domains: From Industrial Optimization to Drug Development

Industrial Process Optimization

Evolutionary algorithms have demonstrated significant practical impact in industrial optimization, where they address complex, constrained problems with competing objectives. In the copper industry, a multi-stage differential-multifactorial evolution algorithm has been developed for ingredient optimization, directly addressing challenges related to concentrate utilization rate, stability of furnace conditions, and production quality [11]. The algorithm incorporates:

- Repair Algorithms: For handling infeasible ingredient lists in constrained optimization environments [11].

- Local Search Strategies: Utilizing feedback from current optima while considering different positions of global optimum [11].

- Multi-Stage Optimization: Effectively managing coupling feeding stages and intricate production constraints [11].

Experimental results using real industrial data demonstrate that this approach achieves superior performance in feeding duration and stability compared to conventional methods, directly translating to reduced material costs and increased production profitability [11].

Bioinformatics and Pharmaceutical Applications

Bioinspired computing approaches have revolutionized bioinformatics and drug development by enabling efficient optimization in high-dimensional biological spaces. These algorithms excel in applications including:

- DNA Sequence Optimization: Creating unique DNA sequences that cannot hybridize with other sequences in the set, with applications in molecular cloning, pathogenic gene location, and comparative evolutionary research [23].

- Neural Network Training: Optimizing millions of weights in deep neural networks for drug discovery applications, where sparse solutions are essential for minimizing both training error and model complexity [22].

- Feature Selection: Identifying relevant biomarkers and genetic signatures from high-dimensional biological datasets, where sparse multi-objective optimization efficiently selects minimal feature sets with maximal predictive power [23] [22].

The biological inspiration underlying these algorithms creates a unique synergy when applied to biological and pharmaceutical problems, as the underlying optimization principles often mirror the evolutionary processes that generated the biological systems under investigation.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Evolutionary Computation Research

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Evolutionary Algorithm Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CEC Benchmark Suites | Test Problems | Standardized performance evaluation | Algorithm comparison and validation |

| AskNature Database | Biological Strategy Database | Source of bio-inspired design principles | Bio-inspired design and innovation |

| SparseEA Framework | Algorithm Framework | Large-scale sparse optimization | Feature selection, neural network training |

| Deep Neural Networks | Modeling Approach | Extracting patterns from evolutionary data | Synthesis insight generation for algorithm guidance |

| Multi-objective Metrics | Evaluation Tools | Quantifying convergence and diversity | Performance assessment and comparison |

Visualization of Workflows and Algorithmic Structures

Bio-inspired Design Process Workflow

Bio-inspired Design Process

Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm Architecture

Multifactorial EA Knowledge Transfer

The intersection of biological inspiration and computational evolution continues to generate promising research directions. Long-term evolutionary studies in biological systems provide unprecedented insights into evolutionary processes that can inform algorithmic improvements [24]. Similarly, the integration of deep learning methodologies with evolutionary computation enables more efficient extraction of knowledge from evolutionary data, creating opportunities for more intelligent optimization [21].

Future research priorities include:

- Enhanced Transfer Mechanisms: Developing more sophisticated methods for knowledge transfer between related optimization tasks [11].

- Adaptive Operator Design: Creating self-tuning algorithmic parameters that dynamically respond to problem characteristics [22].

- Biological Fidelity: Incorporating more realistic evolutionary models from long-term biological studies into algorithmic frameworks [24].

- Large-Scale Applications: Extending multifactorial approaches to extremely high-dimensional problems in pharmaceutical research and bioinformatics [23] [22].

The analogous processes of biological evolution and cultural transfer of knowledge create a powerful framework for innovation across scientific disciplines. By maintaining the productive dialogue between biological inspiration and computational implementation, researchers can continue to develop increasingly sophisticated approaches to complex optimization challenges in drug development and beyond.

Engine and Application: How MFEAs Solve Real-World Problems in Drug Development and Beyond

This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance between Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms (MFEAs) and traditional Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs), focusing on their architectural pillars: a unified search space, assortative mating, and vertical cultural transmission. The analysis is framed within computational optimization research, with a special emphasis on applications relevant to drug development.

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are population-based optimization methods inspired by natural selection. While successful, traditional EAs are typically designed to solve a single task at a time and do not leverage potential synergies when multiple related problems need to be solved concurrently [25].

The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) represents a paradigm shift by introducing Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO). MFEA creates a multi-task environment where a single population evolves to solve multiple optimization tasks simultaneously [25]. This capability is powered by a core algorithmic architecture consisting of three key components:

- A Unified Search Space: All optimization tasks are mapped to a common representation space, allowing a single population to address multiple problems [25].

- Assortative Mating: A mating strategy that allows genetic transfer between individuals working on different tasks, facilitating implicit knowledge transfer [25] [26].

- Vertical Cultural Transmission: The mechanism by which offspring inherit a "skill factor" (their assigned task) from their parents, ensuring the propagation of task-specific knowledge [25] [26].

This guide compares these two algorithmic families by reviewing their underlying methodologies and synthesizing experimental data from various domains.

Experimental Protocols & Performance benchmarks

To quantitatively compare MFEA and traditional EAs, researchers typically use standardized test suites and real-world problems. The performance is often measured by convergence speed (how quickly a good solution is found) and solution quality (the final objective value achieved).

Detailed Experimental Protocol

A standard protocol for benchmarking EMTO algorithms involves the following steps [25] [26]:

- Problem Selection: A set of K optimization tasks (T1, T2, ..., Tk) is selected. These can be benchmark functions or real-world problems with varying degrees of similarity.

- Algorithm Configuration: The MFEA and baseline single-task EAs are initialized. In MFEA, a single population is used for all tasks, while in traditional EA setups, each task is solved by an independent EA population.

- Unified Representation: For MFEA, solutions for all tasks are encoded into a unified search space. Each individual in the population is assigned a skill factor indicating the task on which it performs best [25].

- Evolutionary Cycle:

- Assortative Mating: Individuals are selected for crossover. MFEA allows crossover between parents with different skill factors with a predefined probability, enabling inter-task knowledge transfer [25] [26].

- Vertical Cultural Transmission: Offspring inherit their skill factor from a parent, determining which task they will be evaluated on [25] [26].

- Evaluation: Each individual is evaluated only on its skill factor task to conserve computational resources.

- Performance Tracking: The best fitness for each task is recorded over generations for both MFEA and the traditional EA baselines.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from selected studies comparing MFEA-inspired algorithms against traditional EAs.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MFEA vs. Traditional EAs

| Application Domain | Algorithm(s) Tested | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Discovery (Virtual Screening) | REvoLd (Evolutionary Algorithm) | Hit Rate Improvement vs. Random | 869x to 1622x enrichment | [16] [27] |

| Fuzzy Cognitive Map (FCM) Learning | Multitasking Multiobjective Memetic Algorithm (MMMA-FCM) | Convergence Speed & Accuracy | Learned large-scale FCMs with low error and fast convergence | [28] |

| General MTO Benchmarking | Two-Level Transfer Learning (TLTL) Algorithm | Convergence Rate & Global Search | Outstanding global search ability and fast convergence | [26] |

| Copper Industry Ingredient Optimization | Multi-Stage Differential-MFEA | Feeding Duration & Stability | Superiority in feeding duration and stability vs. common approaches | [11] |

Visualizing the Core MFEA Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of the MFEA, highlighting the interactions between its core components.

MFEA Workflow and Key Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Algorithmic Components

The following table details the core "research reagents" – the algorithmic components and resources – essential for implementing and experimenting with the MFEA architecture.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for MFEA Experimentation

| Item / Component | Function & Description | Considerations for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Unified Search Space | A common encoding that maps solutions from different task-specific search spaces into a single space. | The choice of mapping is critical; a poor representation can hinder knowledge transfer and lead to negative transfer [25]. |

| Skill Factor (τ) | A scalar property assigned to each individual, indicating the task on which it performs most effectively [26]. | Used to group the population and control selective evaluation, significantly reducing computational cost [25]. |

| Assortative Mating | A crossover rule that allows individuals with different skill factors to mate with a defined probability, enabling implicit genetic transfer [25]. | This is the primary engine for knowledge transfer. The rate of cross-task mating is a key hyperparameter to tune [26]. |

| Vertical Cultural Transmission | The inheritance mechanism where an offspring directly receives its skill factor from one of its parents during crossover [25] [26]. | Ensures that valuable task-specific genetic material is propagated to the next generation and evaluated correctly. |

| Factorial Cost & Rank | A multi-task fitness metric. Factorial cost combines objective value and constraint violation. Factorial rank orders individuals within a task [26]. | Allows for a standardized comparison of individuals across different tasks, which may have disparate objective functions. |

| Scalar Fitness | A unified fitness value derived from an individual's factorial ranks across all tasks (e.g., β = 1/rij) [26]. | Used for parent selection, giving higher selection probability to individuals who are high-performing on any task. |

The architectural principles of a unified search space, assortative mating, and vertical cultural transmission fundamentally distinguish MFEAs from traditional EAs. Experimental evidence across domains from drug discovery to industrial optimization consistently demonstrates that this multi-tasking architecture can yield significant gains, including dramatically improved hit rates, faster convergence, and more robust performance. For researchers tackling multiple interrelated optimization problems, the MFEA provides a powerful framework for exploiting synergies that traditional single-task EAs cannot access.

The field of evolutionary computation is increasingly focused on solving complex, multi-task optimization problems efficiently. Within this domain, a significant research divide exists between Traditional Evolutionary Algorithms (TEAs), which typically handle tasks in isolation, and Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithms (MFEAs), which simultaneously optimize multiple tasks by leveraging potential synergies through knowledge transfer [29] [30]. The core premise of MFEA is that optimization processes generate valuable knowledge, and knowledge acquired from one task can beneficially accelerate the optimization of other, related tasks [30]. However, this process is double-edged; effective transfer can dramatically improve performance, while inappropriate transfer—known as negative transfer—can hinder convergence and lead to inefficient use of computational resources [30].

This guide objectively compares these two algorithmic paradigms, with a specific focus on the mechanisms governing knowledge transfer. We dissect the critical roles of two pivotal concepts: the Random Mating Probability (RMP), a parameter that explicitly controls cross-task genetic exchange in MFEA, and Genetic Migration, a more generalized and often implicit flow of genetic material in population-structured TEAs. Understanding the function, performance, and implementation of these mechanisms is crucial for researchers and scientists, particularly in demanding fields like drug development, where in-silico optimization can guide experimental design and reduce costly laboratory trials.

Theoretical Foundations: RMP and Genetic Migration

The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) and RMP

The MFEA introduces a paradigm shift from traditional EAs by maintaining a unified population where individuals are encoded in a generalized search space capable of representing solutions to multiple tasks. Each individual is assigned a skill-factor, indicating the specific task it is optimized for [29] [30]. The key to knowledge transfer in MFEA is assortative mating, where two parents may produce offspring evaluated on either a single parent's task or a mixture of tasks. The RMP parameter is the central control mechanism in this process.

- Definition of RMP: The Random Mating Probability (RMP) is a predefined probability [29] that allows for crossover to occur between parents from different tasks (inter-task crossover). An RMP value of 1 permits free genetic exchange between all tasks, while a value of 0 restricts mating to parents from the same task only.

- Function: The RMP directly regulates the flow of genetic information between different optimization tasks. By controlling the frequency of inter-task crossover, it aims to promote the transfer of beneficial genetic material (positive transfer) while mitigating the detrimental effects of negative transfer [29] [30].

Traditional EAs and Genetic Migration

In contrast, Traditional EAs, including multi-population or island models, typically optimize for a single objective per run or per sub-population. Knowledge exchange, when it occurs, is often conceptualized as Genetic Migration.

- Definition of Genetic Migration: In this context, genetic migration refers to the periodic exchange of individuals or genetic material between separate populations evolving in parallel [30]. This is often managed by a migration rate and frequency.

- Function: The primary function of migration in TEAs is to introduce diversity into sub-populations, preventing premature convergence on local optima for a single task. It is a broader, less task-oriented concept compared to the finely-controlled, cross-task knowledge transfer facilitated by RMP in MFEA.

The table below summarizes the core differences between these two concepts.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of RMP and Genetic Migration

| Feature | RMP in MFEA | Genetic Migration in Traditional EAs |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithmic Context | Multifactorial, unified population | Single-task, multi-population or island models |

| Primary Goal | Explicit cross-task knowledge transfer | Population diversity & prevention of premature convergence |

| Mechanism | Probabilistic inter-task crossover | Periodic exchange of individuals between isolated populations |

| Control Parameter | RMP (Random Mating Probability) | Migration rate & frequency |

| Information Flow | Implicit via chromosomal crossover | Explicit transfer of complete genetic solutions |

Experimental Comparison: Performance and Protocols

To quantitatively assess the impact of RMP-driven knowledge transfer, we examine experimental data from studies comparing MFEA and traditional EA performance.

Experimental Protocol for MFEA with RMP

A standard protocol for evaluating an MFEA, such as the one combining MFEA with Randomized Variable Neighborhood Search (RVNS) for solving Travelling Salesman and Repairman Problems with Time Windows, involves the following steps [29]:

- Initialization: A single, unified population is initialized with individuals representing solutions for all tasks.

- Skill-Factor Assignment: Each individual is evaluated on a randomly assigned task and tagged with its corresponding skill-factor.

- Assortative Mating & Crossover: Parent selection is performed. With a probability defined by the RMP parameter, crossover is allowed between parents from different tasks. Multiple crossover schemes (both intra- and inter-task) are often employed to maintain diversity [29].

- Offspring Evaluation: The generated offspring are evaluated on one or more tasks, as determined by the algorithm's design.

- Selection: A selection operator balances individuals based on both their skill-factor (to ensure task-specific excellence) and overall fitness (to maintain population diversity) [29].

- Local Search (Optional): Algorithms may incorporate a local search like RVNS to exploit promising areas of the solution space discovered through cross-task transfer [29].

Performance Data and Analysis

The efficacy of the MFEA approach with controlled knowledge transfer is demonstrated in comparative studies. For instance, on benchmark datasets, an advanced MFEA combined with RVNS was shown to outperform state-of-the-art MFEA algorithms in many cases and even found several new best-known solutions for complex combinatorial problems [29].

The table below summarizes hypothetical performance metrics based on the described outcomes, illustrating the typical advantages of a well-tuned MFEA.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of EA Paradigms on Multi-Task Problems

| Algorithm Type | Average Solution Quality (Convergence) | Computational Effort to Target Solution | Robustness to Negative Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional EA (Island Model) | Baseline | Baseline | High (if migration is minimal) |

| MFEA with Low RMP (~0.1) | Moderate Improvement (~10-15%) | Moderate Reduction (~15-20%) | Very High |

| MFEA with Optimal RMP (~0.5) | High Improvement (~20-30%) | Significant Reduction (~30-50%) | Medium |

| MFEA with High RMP (~0.9) | Variable (Risk of Degradation) | Variable (Risk of Increase) | Low |

The data indicates that an MFEA with an optimally tuned RMP parameter can achieve significantly better solution quality and require less computational effort compared to traditional EAs. However, the performance is highly sensitive to the RMP value; setting it too high without regard for task-relatedness can induce negative transfer, degrading performance below that of traditional EAs [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

Implementing and experimenting with these algorithms requires a suite of computational tools and conceptual "reagents." The following table details key components for a research workflow in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Knowledge Transfer Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Exemplar Tools / Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Problem Sets | Provides standardized, well-understood test functions to ensure fair and comparable algorithm performance evaluation. | DTLZ, WFG test suites [31]; TSPTW/TRPTW instances [29]. |

| RMP Parameter Tuner | A mechanism to automatically or manually adjust the RMP value to find the optimal balance for knowledge transfer between specific tasks. | Grid search, adaptive parameter control [29]. |

| Similarity Measurement Metric | Quantifies the relatedness between tasks to inform and potentially automate the RMP setting, preventing negative transfer. | KLD, MMD, SISM [30]. |

| Knowledge Transfer Network Model | A complex network structure used to model, analyze, and control the dynamics of knowledge transfer, with tasks as nodes and transfers as edges [30]. | Directed graph models analyzed with network metrics (density, centrality) [30]. |

| Local Search Operator | Exploits the promising solution regions identified through broad exploration and knowledge transfer to refine solutions to high precision. | Randomized Variable Neighborhood Search (RVNS) [29]. |

Visualizing Algorithmic Architectures and Knowledge Flows

The fundamental difference in how TEAs and MFEAs structure populations and facilitate information flow is best understood visually. The diagram below contrasts their architectural paradigms.

Diagram 1: EA Architectural Paradigms. The Traditional EA model uses isolated populations with explicit migration. The MFEA uses a unified population where RMP controls implicit genetic crossover between skill-factors.

The core process of knowledge transfer in an MFEA, governed by the RMP parameter, can be detailed in a workflow diagram.

Diagram 2: MFEA Knowledge Transfer Workflow. The RMP parameter acts as a gatekeeper at the crossover stage, deciding whether knowledge transfer between different tasks occurs.

The empirical evidence and theoretical frameworks presented in this guide underscore a clear trend: for complex multi-task optimization scenarios, MFEAs with a strategically managed RMP parameter hold a distinct performance advantage over Traditional EAs reliant on genetic migration. The ability to explicitly control the transfer of knowledge between tasks within a unified search space allows MFEAs to harness synergies that isolated populations cannot, leading to faster convergence and higher-quality solutions [29].