Mitigating Negative Transfer in Evolutionary Multitask Optimization: Detection, Prevention, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the challenge of negative transfer in Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO), a powerful paradigm for solving multiple optimization problems simultaneously.

Mitigating Negative Transfer in Evolutionary Multitask Optimization: Detection, Prevention, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the challenge of negative transfer in Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO), a powerful paradigm for solving multiple optimization problems simultaneously. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational causes of harmful knowledge transfer, survey state-of-the-art mitigation strategies—from machine learning-based adaptive methods to domain adaptation techniques—and offer a practical guide for troubleshooting and optimizing EMTO algorithms. The content is validated through comparative insights from benchmark studies and real-world applications, providing a roadmap for leveraging EMTO's full potential in complex biomedical research scenarios while ensuring robust and reliable outcomes.

Understanding Negative Transfer: The Foundational Challenge in EMTO

FAQs: Understanding Negative Transfer in EMTO

What is negative transfer in Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO)?

In EMTO, negative transfer occurs when knowledge shared between concurrently optimized tasks interferes with the search process, deteriorating performance compared to solving tasks independently [1]. It is the interference of previous knowledge with new learning, where experience with one set of events hurts performance on related tasks [2]. This happens when implicit knowledge from one task is not beneficial or is actively harmful to solving another.

What are the common symptoms of negative transfer in my experiments?

The primary symptom is a slower optimization convergence rate or a worse final solution quality on one or more tasks when using an EMTO algorithm compared to a traditional single-task evolutionary algorithm [1]. In the AB-AC list learning paradigm, a classic test for negative transfer, the learning rate for the second, modified list is slower than for the first list due to interference [2]. You may also observe the population converging to poor local optima that are shared across tasks.

How can I detect negative transfer during an optimization run?

Monitor the performance of each task individually throughout the evolutionary process. A practical method is to run a single-task algorithm in parallel as a baseline. If the performance of a task in the multi-task environment consistently falls below its single-task baseline, negative transfer is likely occurring [1]. You can also track the transfer of genetic material; if individuals migrated from one task consistently reduce the fitness of the receiving population, this indicates harmful knowledge transfer.

What are the main causes of negative transfer?

The primary cause is low correlation or hidden conflicts between the tasks being solved simultaneously [1]. If the globally optimal solutions for different tasks reside in dissimilar regions of the search space, forcing knowledge transfer can be detrimental. Other causes include inappropriate knowledge representation, an overly high rate of transfer, or transferring knowledge at the wrong time in the optimization process.

What strategies can I use to prevent or mitigate negative transfer?

Research focuses on two key aspects [1]:

- Determining Suitable Tasks for Transfer: Measure inter-task similarity to perform more transfer between highly correlated tasks and reduce transfer between weakly related ones. Dynamically adjust inter-task transfer probability based on the observed amount of positive transfer.

- Improving the Transfer Mechanism: Use implicit methods that improve the selection or crossover of transfer individuals, or explicit methods to directly construct inter-task mappings based on task characteristics to elicit more useful knowledge [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Performance Degradation in Multi-Task Setup

Observed Issue: One or more tasks in the EMTO system show significantly slower convergence or worse final results compared to being optimized independently.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Establish a Baseline: Run a single-task evolutionary algorithm for each task individually to establish performance baselines.

- Monitor Task Fitness: In the EMTO system, log the best and average fitness for each task separately at every generation.

- Compare and Identify: Graph the performance of each task against its single-task baseline. Identify which tasks are suffering and when the performance drop occurs.

- Analyze Transfer Links: If your algorithm tracks transfer events, analyze whether performance drops correlate with specific migration events between tasks.

Solutions:

- Solution 1: Adaptive Transfer Probability

- Methodology: Implement a dynamic mechanism that reduces the probability of transfer between task pairs where negative transfer is suspected. This can be based on the similarity of their current populations or the recent history of successful/unsuccessful transfers.

- Protocol:

- For each pair of tasks, calculate a similarity metric (e.g., based on genotype, phenotype, or fitness distribution) every K generations.

- Maintain a running success rate for migrated individuals over a window of recent generations.

- Adjust the transfer probability between two tasks proportionally to their calculated similarity and the success rate of past transfers.

- Solution 2: Factorized Multi-Task Representation

- Methodology: Use a multi-task algorithm that automatically learns a factorized representation of the search space, separating knowledge that is shared across tasks from knowledge that is task-specific.

- Protocol: Employ an EMTO variant that uses a probabilistic graphical model or a neural network to decompose the population's knowledge base. This allows the algorithm to transfer only the beneficial, shared components while preserving task-specific innovations.

Problem: Algorithm Convergence to Poor Local Optima

Observed Issue: The EMTO algorithm converges prematurely to solutions that are mediocre for all tasks, failing to discover high-quality, specialized solutions.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check the diversity of the population for each task. A rapid loss of diversity suggests that negative transfer is causing a population collapse.

- Analyze the transferred individuals. Are they consistently of lower quality than the receiving population's current best?

Solutions:

- Solution: Transfer Filtering

- Methodology: Implement a filter for migrating individuals based on their quality and novelty relative to the receiving population.

- Protocol:

- Before an individual is transferred from Task A to Task B, evaluate its fitness on a small, randomly sampled subset of the Task B population.

- Only allow the individual to migrate if its estimated fitness is above a certain threshold (e.g., the median fitness of Task B's population) or if it introduces sufficient genetic novelty into Task B's population.

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Negative Transfer

Protocol 1: Benchmarking with Synthetic Problems

This protocol uses well-defined benchmark problems with controllable inter-task relationships to systematically study negative transfer.

Methodology:

- Task Design: Create a set of benchmark functions (e.g., Sphere, Rastrigin). Generate pairs of tasks with known degrees of similarity by applying linear or non-linear transformations to the base functions. The similarity can be precisely controlled to create scenarios ranging from positive to negative transfer.

- Experimental Setup: Run your EMTO algorithm on these task pairs. For comparison, run single-task evolutionary algorithms on each task independently.

- Data Collection: Record the performance (e.g., best fitness vs. evaluation count) for each task in both the multi-task and single-task setups.

- Metric Calculation: Calculate the performance loss or gain attributable to multi-tasking.

Key Quantitative Data from EMTO Research

The following table summarizes metrics and findings relevant to diagnosing negative transfer, as observed in research surveys [1].

| Metric | Description | Typical Observation in Negative Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence Rate | Speed at which a task reaches its optimal solution. | Slower convergence in EMTO vs. single-task optimization [1]. |

| Success Rate of Transfers | Percentage of migrated individuals that improve fitness in the target task. | A low or declining success rate indicates harmful transfers. |

| Inter-Task Similarity | Measured correlation between task landscapes (e.g., using fitness-based metrics). | Negative transfer is more severe between low-similarity tasks [1]. |

| Final Solution Quality | The best fitness value achieved for a task after a fixed number of evaluations. | Worse final solution quality in EMTO vs. single-task optimization [1]. |

Protocol 2: Applying a Meta-Learning Framework for Drug Design

This protocol is adapted from a recent study that combined meta-learning with transfer learning to mitigate negative transfer in a low-data drug discovery context [3].

Methodology:

- Problem Formulation: The goal is to predict active inhibitors for a target protein (e.g., a specific protein kinase) with sparse data. This is the target task. The source domain consists of related prediction tasks (e.g., inhibitors for other protein kinases) with more abundant data [3].

- Meta-Learning Phase: A meta-model is trained to assign weights to individual data points in the source domain. Its objective is to identify an optimal subset of source samples for pre-training, thereby balancing potential negative transfer.

- Transfer Learning Phase:

- A base model (e.g., a classifier) is pre-trained on the weighted source data, where the weights are provided by the meta-model.

- This pre-trained model is then fine-tuned on the limited data from the target task.

- Validation: Model performance is evaluated on a held-out test set for the target task. The study reported a statistically significant increase in performance using this combined approach compared to standard transfer learning, effectively controlling for negative transfer [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data resources used in advanced transfer learning experiments for drug development, as featured in the search results.

| Item / Resource | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| ChEMBL / BindingDB | Public databases containing curated bioactivity data for drugs and small molecules, used as primary sources for building predictive models [3]. |

| ECFP4 Fingerprint | (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint). A molecular representation that encodes the structure of a compound as a fixed-length bitstring, enabling machine learning algorithms to process chemical information [3]. |

| repoDB | A standardized database for drug repositioning that collects both positive and negative drug-indication pairs, useful for training supervised machine learning models [4]. |

| GPT-4 / Large Language Models (LLMs) | Used to systematically analyze clinical trial data (e.g., from ClinicalTrials.gov) to identify true negative examples—drugs that failed due to lack of efficacy or toxicity—for creating more reliable training datasets [4]. |

| Meta-Learning Algorithms (e.g., MAML) | Algorithms that learn to learn; they can find optimal model initializations or weight training samples to enable fast adaptation to new tasks with little data, helping to mitigate negative transfer [3]. |

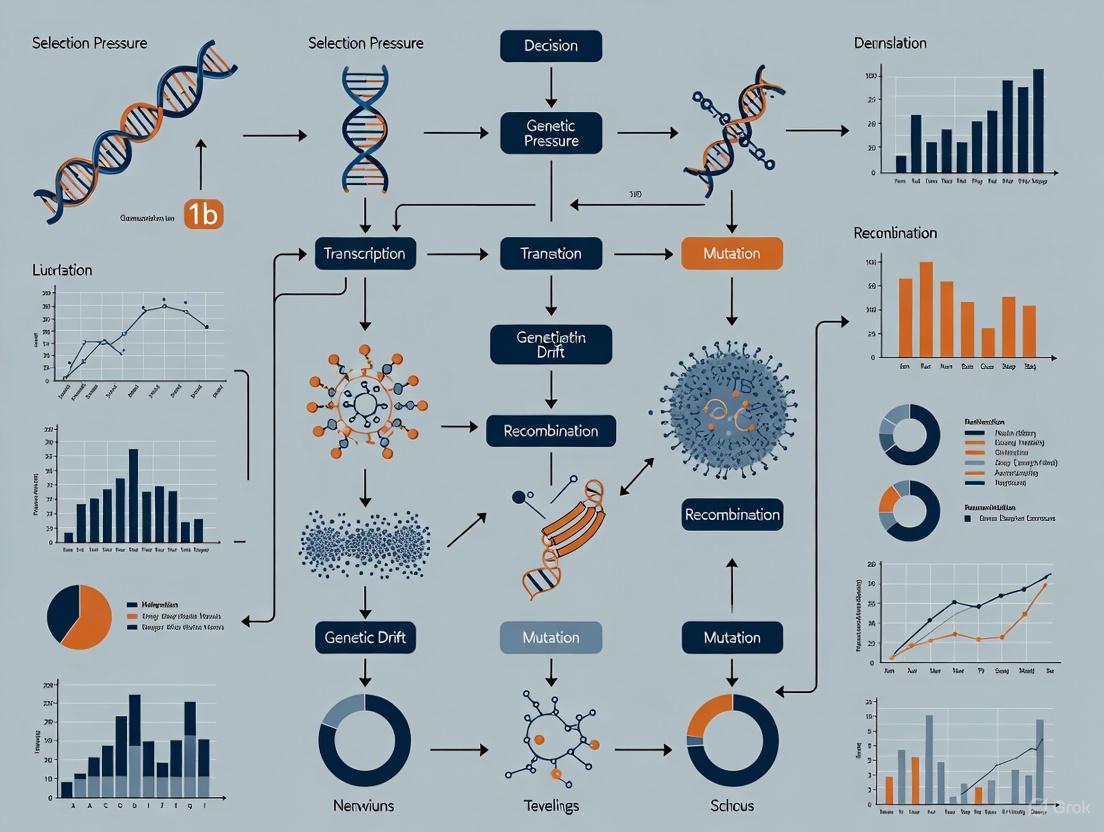

Workflow Visualization

Negative Transfer Mechanism

Mitigation via Meta-Learning

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common root causes of harmful transfer in EMTO? The primary causes are task dissimilarity and dimensionality mismatch. Task dissimilarity occurs when the tasks being optimized simultaneously have conflicting objectives or search spaces, leading to negative knowledge transfer [5]. Dimensionality mismatch happens when tasks have decision variables of different types, numbers, or domains, making it difficult to map and share knowledge between them effectively [5].

How can I detect negative transfer early in an optimization run? Monitor key performance indicators (KPIs) such as convergence speed and the quality of the non-dominated solution set. A noticeable slowdown in convergence or a degradation in the quality of solutions (e.g., a decrease in hypervolume) for one task when knowledge transfer is active is a strong indicator of negative transfer [5]. The use of an information entropy-based mechanism can help track the evolutionary process and identify stages where transfer is detrimental [5].

What is a practical method to prevent harmful transfer? Implement a collaborative knowledge transfer mechanism that operates in both the search space and the objective space. This involves using a bi-space knowledge reasoning method to acquire more accurate knowledge and an adaptive mechanism to switch between different transfer patterns (e.g., convergence-preferential, diversity-preferential) based on the current evolutionary stage of the population [5].

My algorithm suffers from transfer bias. How can this be mitigated? Transfer bias often arises from relying solely on knowledge from the search space while ignoring implicit associations in the objective space [5]. To mitigate this, employ a bi-space knowledge reasoning method that exploits distribution information from the search space and evolutionary information from the objective space. This provides a more comprehensive basis for knowledge transfer and reduces bias [5].

Are there standardized tests for multiobjective multitask optimization algorithms? Yes, research in the field utilizes benchmark multiobjective multitask optimization problems (MMOPs) to evaluate algorithm performance. When selecting or designing a test suite, ensure it contains tasks with varying degrees of similarity and dimensionality to thoroughly assess an algorithm's robustness and its ability to avoid harmful transfer [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Degraded Solution Quality Due to Task Dissimilarity

- Symptoms: The algorithm converges to a poor Pareto front for one or more tasks. The non-dominated solution set for a task is worse when optimized concurrently with other tasks compared to being optimized in isolation.

- Root Cause: The fundamental similarity between tasks is too low, or the knowledge being transferred is not relevant, leading to interference rather than assistance.

- Solution:

- Diagnose Similarity: First, analyze the similarity between tasks in both the search space and objective space. A low similarity often leads to negative transfer [5].

- Implement Adaptive Transfer: Use an information entropy-based collaborative knowledge transfer mechanism (IECKT). This mechanism can automatically detect the evolutionary stage and switch knowledge transfer patterns to favor convergence or diversity as needed, reducing the negative impact of dissimilar tasks [5].

- Refine Transfer Patterns: Configure the algorithm to use convergence-preferential knowledge transfer in the early evolutionary stages and diversity-preferential knowledge transfer in the later stages for complex MMOPs [5].

Problem: Slow Convergence from Dimensionality Mismatch

- Symptoms: Optimization progress is exceptionally slow. The population fails to find improving solutions efficiently across multiple tasks.

- Root Cause: A mismatch in the dimensionality (number or domain of decision variables) between tasks prevents effective knowledge mapping. The algorithm wastes effort on transferring unhelpful or misleading information.

- Solution:

- Employ Space Mapping: Use a search space mapping matrix, derived from techniques like subspace alignment, to transform the population of one task into the search space of another. This helps reduce the probability of negative transfer by aligning the different spaces [5].

- Leverage Bi-Space Reasoning: Adopt a bi-space knowledge reasoning (bi-SKR) method. This technique uses population distribution information from the search space and particle evolutionary information from the objective space to generate higher-quality knowledge for transfer, overcoming the limitations of a single-space view [5].

- Validate with Benchmarks: Test your approach on standardized benchmark problems with known dimensionality mismatches to verify the effectiveness of the mapping [5].

Quantitative Data on Transfer Effects

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from research on knowledge transfer, which can be used as a reference for diagnosing issues in your own experiments.

Table 1: Observed Effects of Knowledge Transfer in Multi-Task Optimization

| Transfer Condition | Impact on Convergence Speed | Impact on Solution Quality (Hypervolume) | Key Reference Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Transfer | Accelerated convergence [5] | Improved quality of non-dominated solution set [5] | CKT-MMPSO [5] |

| Negative Transfer (Harmful) | Slowed convergence or stagnation [5] | Degraded quality of solutions [5] | Standard MFEA [5] |

| Unregulated Implicit Transfer | Unstable and unpredictable [5] | Unstable and unpredictable due to random interactions [5] | MO-MFEA [5] |

| Adaptive Collaborative Transfer | High search efficiency [5] | High-quality solutions with balanced convergence and diversity [5] | CKT-MMPSO (with IECKT) [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Harmful Transfer Analysis

Protocol 1: Establishing a Baseline for Task Dissimilarity

- Objective: To quantify the baseline performance of algorithms on tasks with known, varying degrees of dissimilarity, without any knowledge transfer.

- Methodology:

- Task Selection: Select or design a set of benchmark multiobjective optimization tasks (e.g., ZDT, DTLZ series) where pairs of tasks have controlled differences in their objective functions or search space landscapes [5].

- Isolated Optimization: Run a standard multiobjective optimization algorithm (e.g., NSGA-II) on each task independently. Record the convergence trajectory and the final hypervolume or inverted generational distance (IGD) metric.

- Baseline Metrics: The performance from this isolated optimization serves as the baseline for comparing the effects of multitask optimization.

Protocol 2: Evaluating a Collaborative Knowledge Transfer Algorithm

- Objective: To test the efficacy of a collaborative knowledge transfer-based multiobjective multitask particle swarm optimization (CKT-MMPSO) in preventing harmful transfer.

- Methodology:

- Algorithm Setup: Implement the CKT-MMPSO scheme, which is designed to extract and transfer knowledge from both search and objective spaces [5].

- Integrate Bi-Space Reasoning: Implement the bi-space knowledge reasoning (bi-SKR) method to exploit population distribution information (search space) and particle evolutionary information (objective space) [5].

- Configure Adaptive Mechanism: Employ the information entropy-based collaborative knowledge transfer (IECKT) mechanism. This allows the algorithm to adaptively use different transfer patterns (e.g., convergence-preferential, diversity-preferential) during different evolutionary stages [5].

- Comparison: Execute the CKT-MMPSO on the same task pairs from Protocol 1. Compare its performance against the baseline and against other state-of-the-art EMTO algorithms like MO-MFEA to validate its superiority in mitigating harmful transfer [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational "reagents" — algorithms and components — essential for research into detecting and preventing harmful transfer.

Table 2: Essential Computational Components for EMTO Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Multiobjective Multitask Benchmark Problems (MMOPs) | Provides standardized test suites with known task similarities and mismatches to evaluate and compare algorithm performance fairly [5]. |

| Bi-Space Knowledge Reasoning (bi-SKR) Method | A core component that generates high-quality knowledge for transfer by reasoning across both search and objective spaces, preventing transfer bias [5]. |

| Information Entropy-based Collaborative Knowledge Transfer (IECKT) | An adaptive mechanism that balances convergence and diversity by switching knowledge transfer patterns based on the population's evolutionary stage [5]. |

| Performance Indicators (Hypervolume, IGD) | Quantitative metrics used to rigorously measure the quality and diversity of the obtained non-dominated solution sets for each task [5]. |

Diagnostic Diagrams for Harmful Transfer

Harmful Transfer Diagnosis Path

CKT-MMPSO Framework Overview

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is negative transfer in Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO), and why is it a critical issue? Negative transfer occurs when knowledge exchanged between optimization tasks is unhelpful or misleading, causing the algorithm's performance to deteriorate compared to solving each task independently [1]. It is critical because it can severely slow down convergence, cause populations to become trapped in local optima, and ultimately lead to poor-quality solutions, wasting computational resources and time [6] [7].

FAQ 2: What are the typical symptoms that my EMTO experiment is suffering from negative transfer? Common symptoms include:

- Slowed or Stalled Convergence: The optimization process for one or more tasks progresses much slower than expected or stops improving entirely [7].

- Premature Convergence: The population for a task quickly gets stuck in a local optimum that is inferior to the known global optimum [6].

- Diversity Collapse: A sharp loss of genetic diversity within a population, indicating that transferred solutions are overwhelming the task's own search process [6].

FAQ 3: How can I detect negative transfer during a run? Implement real-time monitoring of per-task performance. A clear indicator is when the performance (e.g., best fitness) of a task degrades or stagnates immediately after a knowledge transfer event [7]. Advanced methods use a competitive scoring mechanism to quantify and compare the outcomes of transfer evolution versus self-evolution [7].

FAQ 4: Are some tasks more prone to causing negative transfer? Yes. Negative transfer is most likely when tasks are highly dissimilar or have low correlation in their fitness landscapes [1]. This is particularly problematic when the global optimum of one task corresponds to a local optimum in another, as successful individuals from the first task can actively mislead the search of the second [6]. Transferring knowledge between tasks of different dimensionalities also carries a high risk if not managed correctly [6].

FAQ 5: What are the primary strategies for preventing negative transfer? The main strategies focus on the "when" and "how" of transfer [1]:

- Adaptive Task Selection: Dynamically select which tasks to transfer between based on their measured similarity or the historical success rate of previous transfers [1] [7].

- Controlled Transfer Frequency and Intensity: Automatically adjust the probability of knowledge transfer to balance it with a task's own evolutionary process [7].

- Search Space Mapping: Use techniques like linear domain adaptation or manifold alignment to create a more compatible mapping between the search spaces of different tasks before transfer, which is especially useful for tasks with differing dimensionalities [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Premature Convergence in One or More Tasks

Description After knowledge transfer, a task's population stops improving and converges to a suboptimal solution.

Diagnosis Steps

- Monitor Fitness Trajectories: Plot the best and average fitness for each task separately. A sudden plateau or drop following inter-task crossover is a strong signal [7].

- Check Population Diversity: Calculate metrics like genotypic or phenotypic diversity. A rapid decline confirms a loss of explorative potential.

- Correlate with Transfer Events: Log the timing of knowledge transfer events. If premature convergence consistently follows transfer from a specific task, you have identified the source of negative transfer.

Solutions

- Implement a Competitive Scoring Mechanism: Introduce a mechanism, like MTCS, that quantifies the success of "transfer evolution" versus "self-evolution." Use the scores to adaptively lower the transfer probability from tasks that cause performance drops [7].

- Apply a Dislocation Transfer Strategy: Rearrange the sequence of decision variables in transferred solutions. This increases individual diversity upon incorporation, helping the population escape local optima [7].

- Integrate a Diversity-Promoting Search Operator: Use a strategy like the Golden Section Search (GSS) based linear mapping to explore new, promising regions of the search space and counteract the homogenizing effect of negative transfer [6].

Problem 2: Performance Deterioration in High-Dimensional or Disparate Tasks

Description The algorithm performs poorly when tasks have a different number of decision variables or fundamentally different fitness landscapes.

Diagnosis Steps

- Profile Task Similarity: Before the run, analyze the tasks. Are their optimal solutions expected to be in different regions? Do they have different dimensionalities? This is a high-risk scenario [6].

- Evaluate Mapping Robustness: If you are using an explicit mapping function (e.g., for dimensionality reduction), check if it is learned from a sufficiently large and representative sample of the population. Unstable mappings are a primary source of negative transfer [6].

Solutions

- Use Manifold Alignment for Transfer: Employ a method like MDS-based Linear Domain Adaptation (LDA). This technique projects high-dimensional tasks into lower-dimensional latent subspaces and learns a robust linear mapping between them, enabling more effective and stable knowledge transfer [6].

- Adopt an Orthogonal Transfer Strategy: Algorithms like OTMTO are designed to learn an orthogonal mapping between tasks, which helps to preserve the unique characteristics of each task's search space while still allowing for beneficial knowledge exchange [6].

Problem 3: Identifying the Source of Negative Transfer in Many-Task Optimization

Description In a many-task scenario (involving more than three tasks), it is difficult to pinpoint which inter-task interaction is causing the overall performance to suffer.

Diagnosis Steps

- Implement Granular Logging: Record the performance of every task before and after every knowledge transfer event, noting the source and target tasks.

- Calculate a Transfer Impact Score: For each pair of tasks, maintain a running score based on the performance change in the target task after receiving knowledge from the source. A consistently negative score indicates a harmful transfer pair [7].

Solutions

- Deploy an Adaptive Source Task Selection: Based on the continuously updated transfer impact scores, dynamically adjust the probability of selecting a given task as a knowledge source. Tasks with a history of causing negative transfer should be chosen less frequently [7].

- Adopt a Multi-Population Framework: Use a multi-population EMTO algorithm where each task has its own population. This provides a clearer structure for monitoring and controlling inter-population (inter-task) knowledge transfers compared to a single, mixed population [7].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Negative Transfer

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate an EMTO algorithm's susceptibility to negative transfer.

Methodology:

- Select Benchmark Problems: Use established multi-task benchmark suites like CEC17-MTSO or WCCI20-MTSO. These suites contain problem pairs with known properties, including No Intersection (NI) of optimal solutions, which are designed to provoke negative transfer [7].

- Define Control Experiment: Run a single-task evolutionary algorithm on each task independently.

- Run EMTO Algorithm: Run the EMTO algorithm on the same set of tasks.

- Metric Calculation: For each task, calculate the performance relative to the control run. A negative value indicates that multitasking has harmed performance due to negative transfer.

Protocol 2: Evaluating a Mitigation Strategy

Objective: To test the effectiveness of a competitive scoring mechanism (e.g., MTCS) in reducing negative transfer.

Methodology:

- Setup: Configure the EMTO algorithm with and without the competitive scoring mechanism on a many-task problem.

- Data Collection: For both configurations, log the convergence curves and final solution quality for all tasks.

- Analysis: Compare the number of tasks that experienced performance degradation. A successful mitigation strategy should show a significant reduction in such tasks and an improvement in overall convergence [7].

Quantitative Data on Negative Transfer Impact: Table 1: Performance Comparison on a Two-Task Benchmark (NI-Type Problem)

| Algorithm | Task 1 Performance (vs. Single-Task) | Task 2 Performance (vs. Single-Task) | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Task EA | 0.0% (baseline) | 0.0% (baseline) | Baseline |

| Basic MFEA | -12.5% | -8.3% | -10.4% |

| MFEA with Adaptive Transfer | -2.1% | +1.7% | -0.2% |

| MTCS (Competitive Scoring) | +3.5% | +4.8% | +4.2% |

Table 2: Effectiveness of Mitigation Strategies on Many-Task Problems (≥5 tasks)

| Strategy | Avg. Performance per Task | Tasks with Degraded Performance | Computational Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Mitigation | -5.2% | 45% | Low |

| Similarity-Based Transfer | +1.1% | 20% | Medium |

| Competitive Scoring (MTCS) | +4.5% | <10% | Medium |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential "Reagents" for EMTO Research

| Item / Algorithm | Function in EMTO Experiments |

|---|---|

| MFEA (Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm) | The foundational algorithm for implicit knowledge transfer; serves as a baseline and framework for many advanced methods [6]. |

| CEC17-MTSO / WCCI20-MTSO Benchmarks | Standardized test problems with known properties to reliably replicate and study negative transfer in a controlled environment [7]. |

| Linear Domain Adaptation (LDA) | A technique to learn explicit mappings between the search spaces of different tasks, facilitating more robust knowledge transfer, especially for tasks of differing dimensionalities [6]. |

| Competitive Scoring Mechanism | A "reagent" to quantitatively measure the outcome of knowledge transfer, enabling algorithms to self-adapt and avoid negative transfer dynamically [7]. |

| Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) | A dimensionality reduction technique used to project tasks into a lower-dimensional latent space before applying transfer mappings, improving stability [6]. |

Workflow Diagrams

FAQs on Framework Selection and Problem Diagnosis

Q1: What are the fundamental architectural differences between Multi-Factorial (MFEA) and Multi-Population EMTO models?

The core distinction lies in how populations are organized and how knowledge transfer is managed.

Multi-Factorial (MFEA): Uses a single-population approach where one unified population tackles all tasks. Each individual is assigned a "skill factor" indicating which task it is most proficient at. Knowledge transfer occurs implicitly through crossover between individuals with different skill factors, controlled by a random mating probability (rmp) parameter [8] [9].

Multi-Population Models: Maintain separate populations for each task. Knowledge transfer is explicitly designed through mechanisms like mapping solutions between task-specific search spaces or using cross-task genetic operators within a unified space [9].

Table: Core Architectural Differences Between MFEA and Multi-Population Models

| Feature | Multi-Factorial (MFEA) | Multi-Population Models |

|---|---|---|

| Population Structure | Single shared population [8] | Multiple dedicated populations [9] |

| Task Association | Skill factor per individual [8] | One population per task [9] |

| Knowledge Transfer | Implicit via crossover (controlled by rmp) [8] | Explicit via mapping or cross-operators [9] |

| Unified Search Space | Required [8] | Often used for transfer [9] |

| Primary Vulnerability | Negative transfer between unrelated tasks [10] [11] | Ineffective mapping between task domains [9] |

Q2: What are the most common symptoms of negative transfer, and how can I diagnose its root cause in my experiments?

Common symptoms of negative transfer include sudden performance degradation, loss of population diversity, and premature convergence in one or more tasks [10] [11]. To diagnose the root cause, systematically check the following:

- Task Relatedness: Are you transferring knowledge between fundamentally unrelated tasks? Negative transfer frequently occurs when "tasks in EMTO have low inter-task similarity" [10] [11].

- Transfer Mechanism: Is your knowledge transfer mechanism too rigid? Fixed parameters like a constant

rmpin MFEA can force harmful transfers [12]. - Solution Quality: Are you directly transferring raw individuals? "Directly transfer[ing] individuals from the source task to target task cannot guarantee the quality of the transferred knowledge" [12].

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Negative Transfer

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid performance drop in one task after transfer | High negative transfer from unrelated tasks | Run tasks independently and compare convergence curves |

| Simultaneous stagnation across multiple tasks | Pervasive negative transfer causing search stagnation [13] | Monitor population diversity metrics (e.g., mean distance to centroid) |

| Slow convergence despite knowledge transfer | Ineffective or "useless" transferred knowledge [12] | Analyze the fitness of transferred solutions before incorporation |

| One task dominates population resources | Fixed resource allocation ignores task hardness differences [9] | Track the number of evaluations consumed by each task over time |

Q3: Which advanced frameworks can I use to mitigate negative transfer in my multi-task optimization experiments?

Several enhanced frameworks have been developed to promote positive transfer and suppress negative transfer:

- MFEA with Adaptive Knowledge Transfer (MFEA-AKT): Adaptively selects crossover operators based on past success to improve transfer quality [12].

- MFEA-II: Uses online learning to adapt the

rmpparameter based on transfer success, reducing negative transfer [12] [11]. - Self-Regulated EMTO (SREMTO): Employs an "ability vector" for each solution to dynamically capture task relatedness and create overlapping subpopulations for more natural transfer [8].

- Gaussian-Mixture-Model-Based Knowledge Transfer (MFDE-AMKT): Uses an adaptive Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to capture subpopulation distributions, with mixture weights adjusted based on inter-task similarity to enable fine-grained transfer control [11].

- Auxiliary-Population-Based Multitask Optimization (APMTO): Designs an auxiliary population to map the global best solution from a source task to a target task, improving transferred solution quality [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Algorithmic Components for Advanced EMTO Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function in EMTO | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Similarity Estimation (ASE) [12] | Mines population distribution info to evaluate task similarity and adjust transfer frequency. | Prevents negative transfer by adapting to actual task relatedness. |

| Opposition-Based Learning (OBL) [10] | Enhances global search ability via intra-task and inter-task opposition-based sampling. | Helps escape local optima and improves population diversity. |

| Hybrid Differential Evolution (HDE) [14] | Combines multiple differential mutation strategies to generate offspring. | Balances convergence speed and population diversity. |

| Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) [11] | Captures the subpopulation distribution of each task for comprehensive model-based transfer. | Enables fine-grained knowledge transfer based on distribution overlap. |

| Linear Domain Adaptation (LDA) [13] | Transforms the source-task subspace into the target-task subspace. | Mitigates negative transfer by aligning task domains. |

| Ability Vector [8] | Quantifies each individual's performance across all constitutive tasks. | Enables dynamic, self-regulated knowledge transfer. |

| Manifold Regularization [13] | Preserves the local geometric structure of data space during transfer. | Retains useful local information that subspace learning might ignore. |

Experimental Protocols for Detecting Harmful Transfer

Protocol 1: Quantifying Inter-Task Similarity Using Distribution Overlap

Objective: To quantitatively measure the similarity between optimization tasks and predict potential negative transfer.

Methodology:

- For each task, collect the elite subpopulation after initial generations.

- Model each task's distribution. The advanced approach uses a Gaussian distribution for each task and constructs a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM). The similarity between two tasks is then calculated based on "the overlap degree of the probability densities on each dimension" [11].

- Calculate a similarity matrix for all task pairs. This matrix can inform adaptive transfer strategies, such as adjusting the

rmpin MFEA or selecting helper tasks in multi-population models [12] [11].

Protocol 2: A/B Testing for Transfer Impact

Objective: To isolate and measure the specific effect of knowledge transfer on optimization performance.

Methodology:

- Setup: Run your EMTO algorithm on the same set of tasks twice.

- Condition A (With Transfer): The algorithm runs with knowledge transfer enabled.

- Condition B (Baseline): The algorithm runs with knowledge transfer disabled (e.g., by setting

rmp=0in MFEA, or isolating populations).

- Measurement: Track the convergence speed (e.g., number of evaluations to reach a target fitness) and final solution quality for each task under both conditions [10] [11].

- Analysis: Positive transfer is indicated by superior performance in Condition A. If Condition B performs better, it signifies dominant negative transfer. This simple protocol provides clear evidence of transfer effectiveness [10].

Diagnostic and Mitigation Workflows

Performance Comparison of Mitigation Strategies

Table: Quantitative Performance of Advanced EMTO Frameworks on Benchmark Problems

| Algorithm | Key Innovation | Reported Improvement Over Basic MFEA | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFDE-AMKT [11] | Adaptive Gaussian Mixture Model for knowledge transfer | Enhanced convergence and positive transfer on low-similarity tasks [11] | Tasks with measurable distribution overlap |

| MFEA-II [12] [11] | Online learning for adaptive rmp |

Reduced negative transfer through parameter adaptation [12] | Environments where task relatedness is unknown a priori |

| APMTO [12] | Auxiliary population for solution mapping | Produces higher-quality transfer knowledge [12] | Scenarios requiring high-fidelity solution translation |

| EMM-DEMS [14] | Hybrid Differential Evolution & Multiple Search Strategy | Faster convergence and better distribution performance [14] | Complex multi-objective MTO problems |

| SRPSMTO [8] | Self-regulated knowledge transfer in PSO | Superior performance on bi-task and five-task MTO problems [8] | PSO-based optimization environments |

Advanced Protocol: Integrating Large Language Models for Autonomous Transfer Design

Objective: To leverage Large Language Models (LLMs) for autonomously generating and improving knowledge transfer models in EMTO, reducing reliance on expert-designed models [15].

Methodology:

- Problem Formulation: Frame the search for a knowledge transfer model as a multi-objective optimization problem, targeting both transfer effectiveness and efficiency [15].

- LLM-Driven Generation: Use carefully engineered prompts with a few-shot chain-of-thought approach to guide the LLM in generating Python code for novel transfer models [15].

- Evaluation: Integrate the generated model into an EMTO framework and evaluate its performance on benchmark problems against hand-crafted models [15].

- Iterative Refinement: Use the evaluation feedback to refine the prompts and guide the LLM toward generating improved models in subsequent iterations [15].

This emerging approach shows promise in generating knowledge transfer models that can "achieve superior or competitive performance against hand-crafted knowledge transfer models" [15].

Advanced Strategies for Detecting and Preventing Harmful Transfer

# FAQ: Troubleshooting Guide for EMTO Experiments

Q1: What are the most effective metrics for quantifying task-relatedness to prevent negative transfer in my EMTO models?

Negative transfer occurs when indiscriminate task grouping harms model performance. To prevent this, recent research has established several robust metrics for quantifying task relatedness.

- Pointwise V-Usable Information (PVI): This metric estimates how much usable information a dataset contains for a given model, effectively measuring task difficulty. The core hypothesis is that tasks with statistically similar PVI estimates are related enough to benefit from joint learning [16] [17]. The methodology involves a two-stage process:

- Calculation: For each task, fine-tune a base model (e.g., a language model) twice: once on the full dataset and once on labels only. The PVI for a test instance is the difference in the negative log-likelihoods from these two models [17].

- Grouping: Perform statistical tests (e.g., paired t-tests) on the PVI estimates of different tasks. Group those tasks for which the PVI distributions are not significantly different [17].

- Task Attribute Distance (TAD): This is a model-agnostic metric that quantifies task relatedness via human-defined or learned attributes. It establishes a theoretical connection to the generalization error bound, meaning a lower TAD between tasks suggests easier adaptation and a lower expected error on the novel task [18].

- Online Transfer Parameter Estimation (in MFEA-II): Used specifically in evolutionary multi-tasking, this method moves beyond a single transfer parameter. It dynamically estimates a similarity matrix that captures the pairwise similarity between all tasks during the optimization process. This prevents negative transfer by ensuring knowledge is only shared between truly similar tasks [19].

The following table summarizes the key metrics and their applicability:

Table 1: Comparison of Task-Relatedness Metrics

| Metric Name | Underlying Principle | Key Advantage | Primary Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pointwise V-Usable Information (PVI) | Measures task difficulty via the usable information in a dataset for a given model [16] [17]. | Directly tied to model performance; applicable to neural networks. | Natural Language Processing, Biomedical Informatics [16] [17] |

| Task Attribute Distance (TAD) | Quantifies distance between tasks using predefined or learned attribute representations [18]. | Model-agnostic; has a theoretical connection to generalization error. | Few-Shot Learning, Meta-Learning [18] |

| Online Transfer Parameter (MFEA-II) | Dynamically estimates a pairwise task similarity matrix during evolutionary optimization [19]. | Prevents negative transfer in multi-task optimization by enabling selective knowledge sharing. | Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization, Reliability Redundancy Allocation [19] |

Q2: My online parameter estimates are too noisy and computationally expensive. How can I smooth the estimates and reduce runtime?

Noisy and slow parameter estimates are common challenges, especially with high-dimensional time-series data. The Smooth Online Parameter Estimation (SOPE) method is designed to address both issues simultaneously, particularly for Time-Varying Vector Autoregressive (tv-VAR) models [20].

- The Core Problem: Traditional methods like the Kalman filter can provide noisy estimates and become computationally prohibitive as data dimensions increase [20].

- The SOPE Solution: SOPE uses a penalized least squares criterion, which allows you to control the smoothness of the parameter estimates directly. This smoothness constraint effectively filters out high-frequency noise, leading to more robust and interpretable estimates [20].

- Protocol for Implementation:

- Model Definition: Define your tv-VAR model of order K for a P-dimensional time series.

- Formulate the Cost Function: The SOPE algorithm minimizes a cost function that balances two goals: the goodness-of-fit to the most recent data and a penalty term that enforces smoothness in the parameter evolution over time.

- Real-Time Update: As each new data observation arrives, the SOPE algorithm efficiently updates the parameter estimates, providing a real-time view of the system's dynamics with controlled smoothness [20].

Experiments show that SOPE achieves a mean-squared error comparable to the Kalman filter but with significantly lower computational cost, making it scalable for high-dimensional problems like dynamic brain connectivity analysis [20].

Q3: How can I structure an experiment to validate that my task-grouping strategy is effectively preventing negative transfer?

A rigorous experimental design is crucial for validating your task-grouping strategy.

- Baseline Comparisons: Always compare your multi-task learning (MTL) model against strong baselines.

- Single-Task Learners (STL): Train an individual model for each task.

- Naive MTL: Train one model on all tasks without any grouping strategy.

- Grouping Strategies: Compare your proposed grouping (e.g., using PVI or TAD) against other grouping methods, such as those based on task embeddings or surrogate models [17].

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate on standard metrics for your domain (e.g., accuracy, F1-score for NLP; reliability value for RRAPs). Crucially, monitor for negative transfer, which is defined as the MTL model performing worse than the single-task model on a given task.

- Quantitative Analysis: Use statistical significance tests (e.g., t-tests) to confirm that the performance improvements of your grouping strategy over the baselines are not due to random chance [17].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Base Model (e.g., BERT, Llama) | Serves as the foundational model for fine-tuning in NLP-based MTL or for calculating PVI [17]. | Choose a model pre-trained on a domain-relevant corpus (e.g., clinical or biomedical text) for best results. |

| Diverse Task Benchmarks | A collection of datasets used to evaluate task-relatedness and MTL performance [17]. | Ensure benchmarks cover a range of difficulties and domains to thoroughly test grouping strategies. |

| Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) Framework | Provides the algorithmic infrastructure (e.g., MFEA-II) for solving multiple optimization problems simultaneously [19]. | Look for frameworks that support dynamic knowledge transfer and online parameter estimation. |

| SOPE Algorithm Implementation | Enables real-time, smooth estimation of parameters in non-stationary time-series models (e.g., tv-VAR) [20]. | Critical for applications requiring real-time tracking of dynamic systems, such as brain connectivity or adaptive control. |

Q4: In practical drug development, what are the key risks when using Closed-System Drug-Transfer Devices (CSTDs) with biologic drugs, and how can they be mitigated?

While CSTDs are used to protect healthcare workers from hazardous drugs, their use with biologic drugs (like monoclonal antibodies) introduces specific product quality risks.

- Key Risks:

- Mitigation Strategies: A phase-appropriate, risk-based assessment is recommended [21].

- Risk Assessment: Evaluate the drug product's sensitivity to stress (e.g., shear, interfacial stress) and the materials of construction (MOC) of the CSTD.

- Compatibility Testing: Conduct in-use studies where the drug product is manipulated with the CSTD. Test for critical quality attributes like sub-visible particles, protein concentration, and aggregates.

- Clear Communication: Provide detailed handling instructions to clinical sites to ensure the compatibility data is reflected in real-world practice [21].

# Workflow Diagrams

PVI-Based Task Grouping Workflow

Online Parameter Estimation with SOPE

## Technical Support Center

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists working on Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization (EMTO). It provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you implement adaptive knowledge transfer mechanisms and overcome the common challenge of negative transfer—where inappropriate knowledge sharing between tasks leads to performance deterioration.

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Negative Transfer

The table below outlines common experimental issues, their diagnostic signals, and recommended solutions based on advanced EMTO research.

| Problem & Symptom | Underlying Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Degradation during Knowledge Transfer• Decline in accuracy or convergence speed when tasks are solved concurrently. | • Macroscopic, task-level similarity measures leading to harmful genetic crossover between dissimilar tasks. | • Implement individual-level transfer control. Use a machine learning model (e.g., a feedforward neural network) to learn and predict the utility of transferring knowledge between specific individual pairs.• Action: Train an online model on historical data of offspring survival status to guide crossover decisions. | [22] |

| Inefficient Parameter Utilization• Model size grows uncontrollably with each new task, yet performance plateaus. | • Dynamic architectures that automatically assign new parameters (e.g., adapters) for every new task, ignoring potential for parameter reuse. | • Employ a reinforcement learning policy for adapter assignment. Use gradient similarity scores between new tasks and existing adapters to decide when to reuse parameters, rewarding positive transfer and penalizing forgetting.• Action: Implement a framework like CABLE to gate the initialization of new parameters. | [23] |

| Slow Convergence & Poor Solution Quality• Algorithm gets stuck in local optima; generated solutions lack diversity. | • Over-reliance on similar individuals (e.g., via SBX crossover) for offspring generation, limiting exploration. | • Adopt a Hybrid Differential Evolution (HDE) strategy. Mix global and local search mutation operators to maintain population diversity and generate higher-quality solutions.• Action: Integrate HDE and a Multiple Search Strategy (MSS) into your EMTO algorithm. | [14] |

| Weak Defense Against Adversarial Attacks• Real-time ML model predictions are easily manipulated, leading to security risks. | • Model vulnerability to small, malicious perturbations in input features, especially in user-facing systems. | • Apply Domain-Adaptive Adversarial Training (DAAT). Generate strong adversarial samples using historical gradient information and train the model to be robust against them while maintaining accuracy on clean data.• Action: Implement a two-stage DAAT process involving Historical Gradient-based Adversarial Attack (HGAA) and domain-adaptive training. | [24] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between basic MFEA and more advanced individual-level transfer methods?

A: The basic Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) uses a single, scalar value (the random mating probability) to control knowledge transfer across all tasks simultaneously. This macroscopic view often leads to negative transfer because it fails to account for the varying degrees of similarity between different task pairs and, more critically, between specific individuals within those tasks. Advanced methods, like MFEA-ML, shift the focus to the individual level. They train an online machine learning model to act as a "doctor" for knowledge transfer, diagnosing whether a crossover between two specific parents from different tasks will likely produce a viable offspring. This allows for a much finer-grained and more effective control of genetic material exchange [22].

Q2: How can I quantitatively measure the risk of negative transfer before it harms my model's performance?

A: You can use gradient similarity as a leading indicator. In adapter-based continual learning systems, you can compute the gradient similarity between a new task and the tasks already learned by an existing adapter. A low similarity score forecasts a high likelihood that learning the new task with this adapter will induce catastrophic forgetting of previous tasks. This metric can be used to train a reinforcement learning policy that decides when to create a new adapter versus when to reuse an existing one, thereby proactively mitigating negative transfer [23].

Q3: My EMTO model suffers from a lack of population diversity. What strategies can I use to improve it?

A: Consider moving away from traditional crossover operators and integrating a Hybrid Differential Evolution (HDE) strategy. Instead of using one differential mutation operator, mix two: one tuned for a global search (to explore new areas and maintain diversity) and another for a local search (to refine solutions and accelerate convergence). This hybrid approach helps the population avoid getting trapped in local optima by generating more diverse and high-quality offspring, which is crucial for solving complex multi-objective problems in EMTO [14].

Q4: In a real-world deployment, how can I make my model more robust against adversarial attacks that aim to manipulate its predictions?

A: For real-time models, robustness is paramount. A recommended approach is Domain-Adaptive Adversarial Training (DAAT). This is a two-stage process:

- Attack Generation (HGAA): Create strong adversarial samples by incorporating historical gradient information into the attack process. This stabilizes the update direction and produces more potent, transferable adversarial examples.

- Robust Training: Train your model using a domain-adaptive framework that treats original samples and adversarial samples as two related domains. The goal is to learn common features from both, enhancing robustness without causing "adversarial overfitting," which would degrade performance on clean data [24].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Individual-Level Transfer with MFEA-ML

This protocol outlines the steps to implement the MFEA-ML algorithm, which uses machine learning to guide knowledge transfer.

- Base Algorithm Setup: Implement a standard MFEA as your foundational framework.

- Training Data Collection: During the evolution process, trace and record the survival status (accepted or rejected) of every offspring generated through inter-task crossover.

- Feature Engineering: For each pair of parent individuals involved in a crossover, extract features that characterize their location in the decision space and their respective task affiliations.

- Model Training & Integration: Train a classifier (e.g., a Feedforward Neural Network) on the collected data to predict the survival success of a candidate crossover. Integrate this model into the MFEA's crossover step: only proceed with crossover and offspring generation if the model predicts a high probability of success [22].

Protocol 2: Adversarial Robustness Enhancement with DAAT

This protocol describes how to apply Domain-Adaptive Adversarial Training to defend against adversarial attacks.

- Proxy Model Construction: As a defender, train a Proxy Soft Sensor (PSS) model that has accuracy similar to your Original Soft Sensor (OSS) model, using the available data.

- Adversarial Sample Generation (HGAA): Generate adversarial samples on the PSS using the Historical Gradient-based Adversarial Attack method. This involves:

- Iteratively perturbing original samples.

- At each iteration, incorporating historical gradient information to compute the current update direction, which stabilizes the process and creates stronger adversarial samples.

- Domain-Adaptive Training: Train your final OSS model using both the original samples and the generated adversarial samples. Employ a domain-adaptive training objective that minimizes the divergence between the feature distributions of the two sample types. This encourages the model to learn common, robust features, balancing high accuracy on clean data with resilience against attacks [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational components and their roles in building adaptive knowledge transfer models.

| Reagent / Component | Function in the Experiment | Key Configuration Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Online ML Model (e.g., FNN) | Acts as an intelligent transfer controller; learns to approve or veto knowledge transfer between individual solution pairs based on historical success data. | The model is trained online during the evolutionary process. Input features must encode individual and task-specific information [22]. |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) Policy | Manages the assignment of dynamic model components (e.g., adapters) to new tasks, deciding between reuse or expansion to maximize positive transfer. | The policy is rewarded for improved model performance and penalized for catastrophic forgetting. Gradient similarity is a key input signal [23]. |

| Hybrid Differential Evolution (HDE) | Generates high-quality and diverse offspring by mixing multiple differential mutation strategies, balancing global exploration and local refinement. | Typically combines a greedier mutation operator (for convergence) with a more random one (for diversity) [14]. |

| Similarity / Affinity Matrix | A dynamic matrix that quantifies pairwise similarity between tasks, replacing the single scalar transfer parameter used in basic MFEA. | Enables more nuanced and controlled knowledge sharing. Can be estimated online from population data [19]. |

| Gradient Similarity Calculator | Computes the alignment between the gradients of a new task and those of existing tasks/adapters to forecast forgetting and guide parameter reuse. | A low similarity score indicates a high risk of negative transfer if parameters are shared, suggesting a new adapter should be created [23]. |

Methodological Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Individual-Level Adaptive Transfer Workflow

This diagram illustrates the core workflow of an EMTO algorithm that uses machine learning for individual-level knowledge transfer control.

Diagram 2: Adapter Reuse Policy with Reinforcement Learning

This diagram shows the decision-making process for reusing existing adapters versus creating new ones in a continual learning setting, using a reinforcement learning policy.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on MDS and PAE for Search Space Alignment

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when applying Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) and Progressive Auto-Encoding (PAE) for search space alignment in Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO), with a focus on detecting and preventing negative transfer.

FAQ 1: How can I detect negative transfer when using domain adaptation in my multi-task experiment?

A: Negative transfer occurs when knowledge from a source task impedes performance on a target task. Detecting it requires monitoring the effects of transferred knowledge.

- Monitor Evolutionary Score: Implement a competitive scoring mechanism to quantify the outcomes of transfer evolution versus self-evolution. A consistently lower score for transfer evolution indicates negative transfer [7].

- Analyze Population Distribution: Use Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) to calculate distribution differences between sub-populations of source and target tasks. A significant distribution mismatch in the transferred sub-population can signal harmful transfer [25].

- Validate with Proper Metrics: Rely on realistic validation criteria that do not use target test labels for hyperparameter optimization. Over-optimism often arises from improper validation practices [26].

Troubleshooting Protocol: If you detect negative transfer, immediately reduce the probability of knowledge transfer and re-evaluate your source task selection. The dislocation transfer strategy can also be applied to increase individual diversity and may help circumvent the issue [7].

FAQ 2: My MDS algorithm is producing high stress values. What steps should I take to improve the low-dimensional representation?

A: High stress values indicate poor preservation of inter-object distances in the lower-dimensional space.

- Check Input Matrix: Ensure your dissimilarity matrix accurately reflects the pairwise distances. High stress can originate from noisy or inaccurate input data [27].

- Re-evaluate Dimensionality: The chosen number of dimensions, N, might be too low. Try increasing N and observe if the stress value drops significantly [27].

- Algorithm Selection: Confirm you are using the correct MDS variant. For non-metric distances, use Non-metric MDS (NMDS), which finds a monotonic relationship between dissimilarities and Euclidean distances, rather than assuming metric distances like Classical MDS [27].

Troubleshooting Protocol: Systematically validate your MDS configuration using the table below:

| Investigation Area | Action Item | Desired Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Input Data | Verify the distance calculation method. | Accurate, meaningful dissimilarities. |

| Stress/Strain | Confirm the loss function (Strain for Classical, Stress for Metric MDS) is appropriate [27]. | Correct optimization procedure. |

| Dimensionality (N) | Experiment with progressively higher N values. | Stress value stabilizes or reaches an acceptable threshold. |

FAQ 3: What is the best way to integrate Progressive Auto-Encoding into an existing multi-population EMTO framework?

A: Integrating PAE involves dynamically updating domain representations throughout the evolutionary process to replace static pre-trained models [28].

- Choose a PAE Strategy: Implement either Segmented PAE or Smooth PAE based on your optimization needs.

- Insert into the Evolutionary Loop: The PAE module should be called continuously during the optimization process, not just at the beginning. This allows the model to adapt to the changing populations [28].

Troubleshooting Protocol: If integration causes instability or performance drops:

- Check Training Data: For Smooth PAE, ensure the pool of eliminated solutions is diverse and representative.

- Adjust Training Frequency: If using Segmented PAE, verify that the stage transitions align with meaningful changes in population convergence.

- Validate Representation: Periodically test if the auto-encoder's latent space produces meaningful cross-task transfers.

FAQ 4: How can I adapt these methods for a "many-task" optimization scenario (more than 3 tasks) where the risk of negative transfer is high?

A: Many-task optimization amplifies the challenge of negative transfer. A robust adaptive strategy is crucial.

- Implement Competitive Scoring (MTCS): This mechanism automatically quantifies the benefit of knowledge transfer for each task pair and adapts the transfer probability accordingly. It seeks a balance between transfer evolution and self-evolution, which is critical in many-task settings [7].

- Leverage Population Distribution: Do not treat entire task populations as monolithic. Divide each population into K sub-populations and use MMD to select the most distributionally similar sub-population from a source task for knowledge transfer. This fine-grained approach is particularly effective for problems with low inter-task relevance [25].

- Prioritize Source Task Selection: Use evolutionary scores to rank potential source tasks, selecting those with the highest positive impact on the target task to minimize the probability of negative transfer [7].

The following workflow integrates these concepts for managing many-task scenarios:

FAQ 5: What are the most realistic validation practices for domain adaptation in a restricted data-sharing environment?

A: A major pitfall in DA research is using target test labels for hyperparameter tuning, which creates over-optimistic results [26]. Realistic practices are essential, especially under data-sharing constraints.

- Use Proper Validation Splits: Never use the test set for validation. Create a separate validation split from the source domain or use a small, labeled subset of the target data if available [26].

- Explore Novel Validation Metrics: In the absence of target labels, leverage recently proposed unsupervised validation criteria that assess transfer quality without ground truth. These provide a more realistic performance estimate [26].

- Adopt a Federated Learning Mindset: In clinical or other sensitive domains, source data is often not shareable. In these cases, focus on methods where the source site shares only a trained model, and the target site adapts it using its local unlabeled data [29].

Troubleshooting Protocol: If your model's real-world performance is worse than validation scores indicated, audit your validation pipeline for the following:

- Data Leakage: Ensure no information from the target test set leaked into the training or validation process.

- Inadequate Metrics: The validation metrics used may not correlate well with true task performance on the target domain. Experiment with different unsupervised metrics [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential conceptual "reagents" and their functions in experiments involving MDS and PAE for EMTO.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Dissimilarity Matrix | A square matrix (D) where entry d_{i,j} represents the computed distance or dissimilarity between objects i and j. It is the primary input for any MDS algorithm [27]. |

| Stress/Strain Function | A loss function that an MDS algorithm minimizes. Stress (used in Metric MDS) measures the residual sum of squares between input distances and output distances. Strain (used in Classical MDS) is derived from a transformation of the input matrix [27]. |

| Auto-Encoder (AE) | A neural network used for unsupervised learning of efficient data codings. In PAE, it learns compact, high-level task representations to facilitate robust knowledge transfer, rather than performing simple dimensional mapping [28]. |

| Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) | A statistical test to determine if two samples come from the same distribution. In EMTO, it is used to measure distribution differences between task populations to guide the selection of beneficial knowledge for transfer [25]. |

| Competitive Score | A quantitative measure to assess the outcome of an evolutionary step. It is calculated based on the ratio of successfully evolved individuals and their degree of improvement, allowing for adaptive knowledge transfer [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating PAE for Domain Adaptation

This protocol outlines the key steps for integrating and evaluating the Progressive Auto-Encoding (PAE) technique within an EMTO algorithm.

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of PAE in improving convergence and solution quality while mitigating negative transfer.

Methodology Details:

- Baseline Setup: Begin with a multi-population evolutionary framework where each task has a dedicated population [28] [7].

- Integration: Incorporate the PAE module into the evolutionary loop. The module should be accessible for continuous updates throughout the optimization process, not just during initialization.

- Strategy Selection & Execution:

- For Segmented PAE, pre-define evolutionary phases (e.g., early, mid, late convergence) and train a dedicated auto-encoder at the start of each phase using current population data [28].

- For Smooth PAE, maintain a repository of recently eliminated solutions. Periodically update the auto-encoder using this repository to facilitate gradual domain refinement [28].

- Knowledge Transfer: When a knowledge transfer operation is triggered for a target task, use the latest auto-encoder to transform individuals from a source task before injecting them into the target population.

- Validation & Analysis: Compare the performance (e.g., convergence speed, final solution quality) against state-of-the-art algorithms on benchmark suites. Crucially, perform hyperparameter optimization using a separate validation set or realistic unsupervised criteria, not the target test set [26].

The logical relationship and data flow between these core components are visualized below:

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: My GSS algorithm is converging very slowly. What could be the cause? A slow convergence rate often indicates an incorrect implementation of the probe point selection. Ensure that the interior points

canddare calculated using the golden ratio constant,invphi ≈ 0.618, and that the interval reduction is happening correctly. Verify your termination condition; a tolerance that is too strict will unnecessarily increase iterations [30].FAQ 2: How can I verify that my GSS implementation is working correctly for a maximum and not a minimum? The GSS algorithm for finding a maximum is identical to that for a minimum, except for the comparison operator when deciding which interval to keep. For a maximum, you should select the sub-interval containing the higher function value. In the provided Python code, the line

if f(c) < f(d):for a minimum becomesif f(c) > f(d):for a maximum [30].FAQ 3: Can the GSS algorithm be applied to functions with multiple local optima within the initial interval? The golden-section search is designed for strictly unimodal functions. If the initial interval

[a, b]contains multiple local extrema, the algorithm will converge to one of them, but it cannot guarantee that it will be the global optimum. For multi-modal functions, alternative global optimization techniques should be considered [30].FAQ 4: In an EMTO context, when should I avoid using a GSS-derived strategy due to the risk of harmful transfer? GSS-derived strategies, such as the shape Knowledge Transfer (KT) strategy, should be avoided when the optimization tasks are highly dissimilar in both their function shape (convergence trend) and their optimal domain (promising search regions). In such scenarios, an intra-task strategy that focuses on independent optimization is safer and more efficient [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Algorithm converges to a boundary point.

- Cause: The true extremum is located outside the specified initial interval

[a, b], or the function is not unimodal on the given interval. - Solution: Widen the initial search interval

[a, b]and verify the unimodality of the function within it. For EMTO, analyze the inter-task scenario features to confirm that the task domains are sufficiently similar for a domain KT strategy to be beneficial [31].

- Cause: The true extremum is located outside the specified initial interval

Problem: Results are unstable when transferring knowledge in EMTO.

- Cause: The transfer strategy is likely harmful because the source and target tasks have dissimilar evolutionary scenarios.

- Solution: Implement a Scenario-based Self-Learning Transfer (SSLT) framework. Use a Deep Q-Network (DQN) to learn the relationship mapping between extracted evolutionary scenario features (states) and the most appropriate scenario-specific strategy (action), such as intra-task, shape KT, domain KT, or bi-KT [31].

Problem: The algorithm fails to find an extremum with sufficient accuracy.

- Cause: The termination tolerance may be too large, or the maximum number of iterations may be too low.

- Solution: Tighten the tolerance value in the termination condition. The required number of iterations to achieve an absolute error of ΔX is approximately

ln(ΔX/ΔX₀) / ln(φ-1), where ΔX₀ is the initial interval width. You can pre-calculate the number of iterations needed to achieve your desired accuracy [30].

GSS Performance and Parameter Reference

Table 1: Key Parameters for the Golden-Section Search Algorithm [30]

| Parameter/Variable | Symbol/Code | Typical Value / Formula | Role in Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Ratio | φ |

( \varphi = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} \approx 1.618 ) | Defines the optimal proportional spacing of points. |

| Its Inverse | invphi |

( \frac{\sqrt{5}-1}{2} \approx 0.618 ) | Used to calculate new interior points within the interval. |

| Interval Reduction Factor | r |

( r = \varphi - 1 \approx 0.618 ) | The factor by which the interval shrinks each iteration. |

| Interior Point | c |

b - (b - a) * invphi |

One of two points evaluated inside the interval [a, b]. |

| Interior Point | d |

a + (b - a) * invphi |

The second point evaluated inside the interval [a, b]. |

| Termination Condition | tolerance |

1e-5 (example) |

Stops iteration when (b - a) < tolerance. |

Table 2: Scenario-Specific Strategies for Multi-Task Optimization [31]

| Evolutionary Scenario | Recommended Strategy | Primary Mechanism | Goal in EMTO Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Only Similar Function Shape | Shape Knowledge Transfer (KT) | Transfers information about the convergence trend from source to target population. | Increase convergence efficiency. |

| Only Similar Optimal Domain | Domain Knowledge Transfer (KT) | Moves the target population to promising search regions using distributional knowledge from source task. | Escape local optima. |

| Similar Shape and Domain | Bi-KT Strategy | Applies both Shape KT and Domain KT simultaneously. | Increase transfer efficiency on both fronts. |

| Dissimilar Shape and Domain | Intra-Task Strategy | Disables knowledge transfer from other tasks. | Prevent harmful transfer and focus on independent search. |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating GSS with an SSLT Framework

This protocol outlines the methodology for incorporating a GSS-inspired strategy into a Scenario-based Self-Learning Transfer framework for Multi-Task Optimization Problems (MTOPs).

1. Objective: To enhance an EMTO algorithm's ability to escape local optima by automatically selecting the most appropriate search and transfer strategy based on the real-time evolutionary scenario.

2. Materials/Reagents:

- Software Platform: A computational environment such as MATLAB or Python is required. The MTO-Platform toolkit for Matlab is recommended for baseline testing [31].

- Backbone Solver: A base optimization algorithm, such as Differential Evolution (DE) or a Genetic Algorithm (GA), which will be enhanced by the framework [31].

- SSLT Framework Components: The code for the Deep Q-Network (DQN) relationship mapping model, the ensemble method for feature extraction, and the four scenario-specific strategies [31].

3. Procedure:

a. Initialization: For each of the K tasks in the MTOP, initialize the population randomly within their search regions Ω_k [31].

b. Knowledge Learning Stage (Early Evolutionary Stages):

i. Feature Extraction: For the current population of each task, use the ensemble method to extract evolutionary scenario features from both intra-task (e.g., population distribution) and inter-task (e.g., similarity of shape and domain with other tasks) perspectives [31].

ii. Random Exploration: Execute a randomly selected scenario-specific strategy (from the set of four) and apply it.

iii. Model Building: Record the state (features), action (strategy), and the resulting evolutionary performance (reward) to build and update the DQN model [31].

c. Knowledge Utilization Stage (Later Evolutionary Stages):

i. State Recognition: Input the current extracted evolutionary scenario features into the trained DQN model.

ii. Strategy Selection: The DQN model outputs the Q-values for each possible strategy. Select the scenario-specific strategy with the highest Q-value [31].

iii. Strategy Execution: Apply the selected strategy (e.g., Domain KT to move populations using GSS principles) to generate the next population.

d. Termination and Analysis: Continue the evolutionary process until a termination condition (e.g., maximum iterations) is met. Analyze the final solutions and the sequence of strategies selected by the DQN to understand the algorithm's behavior.

Workflow and Strategy Logic Visualization

SSLT Framework Operational Workflow

Scenario-Specific Strategy Selection Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Components for SSLT-GSS Experiments [30] [31]