Linkage Disequilibrium Association Studies: A Comprehensive Guide for Genetic Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and applying linkage disequilibrium (LD) in genetic association studies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Linkage Disequilibrium Association Studies: A Comprehensive Guide for Genetic Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and applying linkage disequilibrium (LD) in genetic association studies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It bridges foundational theory with advanced methodology, covering the evolutionary forces shaping LD, practical application in GWAS and fine-mapping, strategies to overcome computational and interpretative challenges, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this guide aims to enhance the design, execution, and interpretation of LD-based analyses to accelerate the discovery of trait-associated genes and therapeutic targets.

The Evolutionary Forces and Fundamental Principles of Linkage Disequilibrium

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between linkage and linkage disequilibrium (LD)? Answer: Linkage refers to the physical proximity of genes or genetic markers on the same chromosome in an individual, influencing how they are inherited together. Linkage Disequilibrium (LD), in contrast, is a population-level concept describing the non-random association of alleles at different loci. Essentially, it indicates whether specific alleles at two different locations are found together on the same chromosome more or less often than would be expected by chance [1] [2]. Even closely linked loci may not show association in a population, and LD can exist between unlinked loci due to factors like population structure [1].

2. When should I use r² versus D' as my LD measure? Answer: The choice depends on your research question. The table below summarizes the key differences:

| Aspect | r² (Squared Correlation) | D' (Standardized D) |

|---|---|---|

| Best For | Tag SNP selection, GWAS power, imputation quality | Inferring historical recombination, haplotype block discovery |

| What it Captures | How well one variant predicts another; variance explained | Whether recombination has likely occurred between the sites |

| Sensitivity to MAF | High; penalizes mismatched minor allele frequencies | Less sensitive; can be high even for rare alleles |

| Interpretation | 0.2=Low, 0.5=Moderate, ≥0.8=Strong (for tagging) | ≥0.9 often indicates "complete" LD given the allele counts [3] |

3. What are the common causes of spurious or unexpected LD signals? Answer: Several experimental and population factors can create misleading LD results:

- Population Stratification: Unaccounted-for population structure or ancestry differences within your sample is a major cause. Always stratify analyses by ancestry or use principal components as covariates [3].

- Genotyping Errors: Systematic errors, batch effects, or poor quality control can mimic LD by creating spurious non-random associations [3].

- Small Sample Size and Rare Variants: Genetic drift in small samples can create strong LD. Similarly, estimates of D' can be inflated and unreliable for rare alleles (low MAF) due to small counts [3] [4].

- Data Quality: Markers with high missingness rates or deviations from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium can distort LD calculations [5].

4. How can I visualize LD to improve the interpretation of my association study results? Answer: Combining association results (e.g., -log10(p-values)) with LD information in a single figure is a powerful method. This can be achieved with heatmaps that display association strength on the diagonal and the expected association due to LD on the off-diagonals. This helps distinguish true association signals from those that are merely correlated with a primary signal, thereby improving the localization of causal variants [6]. Tools like LocusZoom and Haploview can generate such visualizations [3] [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common LD Analysis Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent LD Patterns Between Populations

- Symptoms: LD decay curves have different slopes, or haplotype blocks are structured differently when the same genomic region is analyzed in two distinct populations.

- Background: LD patterns are shaped by population-specific demographic history, including bottlenecks, expansions, admixture, and effective population size [3] [2]. A longer chromosome is generally associated with weaker average LD in a random-mating population (the "Norm I" pattern), but this can be distorted by a population's unique history [4].

- Solution:

Problem 2: Unusually Widespread or Long-Range LD

- Symptoms: Strong LD (high r² or D') persists over hundreds of kilobases or even between different chromosomes, contrary to the typical rapid decay with physical distance.

- Background: While LD typically decays with distance due to recombination, extended LD can be caused by:

- Selection: A selective sweep can "hitchhike" linked variants, creating a region of high LD around the selected allele [3] [2].

- Recent Admixture: Mixing of previously separated populations introduces long-range LD between ancestry-informative markers [3].

- Regions with Low Recombination: Pericentromeric regions or "coldspots" naturally exhibit more extended LD [4] [2].

- Artifacts from Imputed or Rare Variants: Enriched rare or imputed variants can lead to much more extended LD patterns [4].

- Solution:

- Investigate known regions: Check if the signal is in a region known for long-range LD (e.g., the MHC region in humans) and handle it with special rules during clumping [3].

- Check for population structure: Use PCA or other methods to ensure the sample is genetically homogeneous [5].

- Apply filters: Use a Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) filter (e.g., MAF > 0.01 or 0.05) to reduce noise from rare variants, especially for D' [3] [4].

Problem 3: Weak or No LD Between Tightly Linked SNPs

- Symptoms: Two SNPs that are physically close on the chromosome show little to no LD.

- Background: The primary force breaking down LD is recombination. The presence of a recombination hotspot between the two SNPs can rapidly erode LD, even over very short physical distances [3] [2]. According to population genetics theory, LD decreases each generation by a factor of (1-c), where c is the recombination frequency [1].

- Solution:

Essential Workflows & Methodologies

Standard LD Analysis Workflow

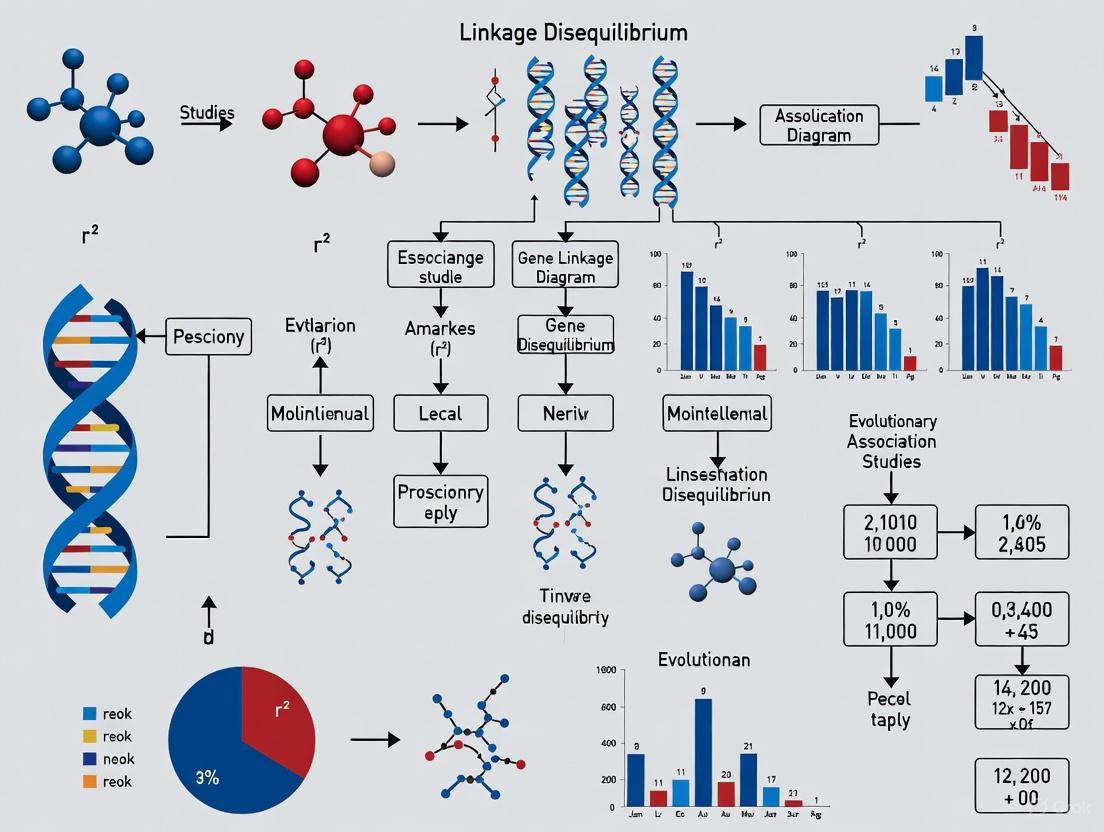

The following diagram outlines the key steps for a robust linkage disequilibrium analysis, from data preparation to interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in LD Analysis | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SNP Arrays (e.g., Axiom) | High-throughput, cost-effective genotyping for population screens. | Established validation; may have ascertainment bias [5]. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Comprehensive variant discovery without ascertainment bias. | Ideal for detecting rare variants and deep ancestry inference [5]. |

| PLINK | A cornerstone tool for processing genotype data, calculating r², pruning, and clumping. | Standard in GWAS workflows; fast for common LD tasks [3] [5]. |

| Haploview | Specialized in visualizing LD patterns and defining haplotype blocks. | Classic for block visualization; has a legacy user interface [3] [5]. |

| LocusZoom | Creates publication-quality locus plots with association statistics and LD information. | Requires summary statistics and an LD reference panel [3] [6]. |

| Reference Panels (e.g., 1000 Genomes, HapMap) | Provide population-specific LD information for imputation and meta-analysis. | Critical for studies without a internal LD reference; must match study population ancestry [7] [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between D, D′, and r² in measuring linkage disequilibrium? D is the raw linkage disequilibrium coefficient, representing the deviation between observed haplotype frequency and the frequency expected under independence [8]. D′ (D-prime) is a normalized version of D, scaled to its maximum possible value given the allele frequencies, making it range from -1 to 1 [8]. In contrast, r² is the square of the correlation coefficient between two loci [9] [8]. A key practical difference is that r² directly relates to statistical power in association studies, as the power to detect association at a marker locus is approximately equal to the power at the true causal locus with a sample size of N*r² [9].

Q2: Why can my r² value never reach 1, even for two seemingly tightly linked SNPs? The maximum possible value of r² is constrained by the allele frequencies at the two loci [9]. For two biallelic loci, r² can only achieve its maximum value of 1 if the allele frequencies at both loci are identical (pA = pB) or exactly complementary (pA = 1 - pB) [9]. If your SNPs have very different minor allele frequencies, the theoretical maximum for r² will be less than 1, explaining why you cannot observe a value of 1.

Q3: When should I use D′ versus r² for reporting LD in my study? The choice depends on your goal. Use D′ if you are interested in the recombination history between loci, as it indicates whether recombination has occurred between two sites [8]. Use r² if your focus is on association mapping, as it directly predicts the power of association studies and is useful for selecting tag SNPs for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [9] [8].

Q4: I am using LD to select tag SNPs. Why is r² the preferred metric for this purpose? r² is preferred for tag SNP selection because it quantifies how well one SNP can serve as a proxy for another [9]. In a disease association context, the power to detect association with a marker locus is approximately equal to the power at the true causal locus with a sample size of N*r² [9]. Therefore, an r² threshold (e.g., r² > 0.8) ensures that the tag SNP retains a high proportion of the power to detect association at the correlated SNP.

Q5: What does a D′ value of 1.0 actually mean, and why should I interpret it with caution? A D′ value of 1.0 indicates that no recombination has been observed between the two loci in the evolutionary history of the sample, or that the sample size is too small to detect it [8]. Caution is needed because D′ can be inflated in small sample sizes or when allele frequencies are low, potentially giving a false impression of strong LD when the evidence is weak.

Troubleshooting Common LD Analysis Issues

Problem: Inflated D′ values in small sample sizes.

- Cause: D′ is sensitive to small sample sizes and can be artificially inflated, especially for rare alleles.

- Solution: Increase sample size where possible. If not feasible, be cautious in interpreting D′ values for low-frequency variants and consider reporting confidence intervals.

Problem: Unexpectedly low r² values between two physically close SNPs.

- Cause: The SNPs may have very different allele frequencies, constraining the maximum possible r² [9]. Alternatively, a recombination hotspot may exist between them.

- Solution: Check the allele frequencies of both SNPs. Calculate the theoretical maximum r² given the frequencies. If the observed r² is still much lower than the maximum, it suggests a historical recombination event.

Problem: Software errors when calculating LD for multi-allelic markers.

- Cause: Standard D, D′, and r² formulas are designed for biallelic loci (like SNPs). Many LD calculation tools do not support multi-allelic markers by default.

- Solution: Recode multi-allelic markers (e.g., microsatellites) into multiple biallelic variables or use specialized software that can handle multi-allelic LD.

Data Presentation: LD Metric Properties

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Primary LD Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Range | Primary Interpretation | Main Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | ( D = p{AB} - pAp_B ) [8] | Frequency-dependent [8] | Raw deviation from independence | Building block for other measures; population genetics |

| D′ | ( D' = D / D_{max} ) [8] | -1 to 1 [8] | Proportion of possible LD achieved; recombination history | Inferring historical recombination; identifying LD blocks |

| r² | ( r^2 = \frac{D^2}{pA(1-pA)pB(1-pB)} ) [8] | 0 to 1 [9] | Correlation between loci; statistical power | Association study power calculation; tag SNP selection |

Table 2: Maximum r² Values Under Different Allele Frequency Constraints [9]

| Condition | Maximum r² Formula | Example: pa=0.3, pb=0.4 |

|---|---|---|

| General maximum | ( r^2{max}(pa, p_b) ) | Varies by frequency combination |

| Allele frequencies equal (pₐ = pᵦ) | 1 | 1 |

| Minor allele frequencies differ | ( \frac{(1-pa)(1-pb)}{papb} ), ( \frac{pa(1-pb)}{(1-pa)pb} ), etc. [9] | ~0.583 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating D, D′, and r² from Haplotype Data

Purpose: To compute fundamental LD metrics from observed haplotype frequencies for two biallelic loci.

Materials:

- Genotype or haplotype data for two SNPs.

- Software: PLINK, Haploview, or statistical programming language (R/Python).

Methodology:

- Estimate Haplotype Frequencies: If using genotype data, use an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm or phasing tool to estimate the frequencies of the four possible haplotypes (AB, Ab, aB, ab).

- Calculate Allele Frequencies:

- ( pA = p{AB} + p{Ab} )

- ( pa = p{aB} + p{ab} )

- ( pB = p{AB} + p{aB} )

- ( pb = p{Ab} + p{ab} ) [8]

- Compute D:

- ( D = p{AB} - pAp_B ) [8]

- This can also be calculated as ( D = p{AB}p{ab} - p{Ab}p{aB} ).

- Compute D′:

- Compute r²:

- ( r^2 = \frac{D^2}{pA(1-pA)pB(1-pB)} ) [8]

Protocol 2: Visualizing LD in a Genomic Region with LocusZoom

Purpose: To create a publication-ready plot displaying association statistics and LD structure in a genomic region.

Materials:

- Summary statistics from a GWAS for the region of interest.

- A reference panel for LD (e.g., from HapMap or 1000 Genomes Project).

Methodology:

- Access LocusZoom: Navigate to the LocusZoom web interface [10].

- Upload Data: Provide your summary statistics file, which should include SNP identifiers (rsIDs or chr:position), P-values, and optionally, effect sizes and sample sizes.

- Specify the Region: Define the genomic region to plot using an index SNP and flanking region size, a gene name, or explicit chromosomal start and stop positions [10].

- Choose LD Reference: Select an appropriate reference population that matches your study's ancestry (e.g., CEU for European) [10].

- Generate Plot: Submit the job. The tool will generate a plot showing association strength (-log10 P-values), local LD structure (usually as r² or D′ with the index SNP), and annotated genes in the region [10].

Visualizing Linkage Disequilibrium Concepts

LD Metric Calculation Workflow

LD Metric Relationships and Uses

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis

| Tool Name | Type/Format | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLINK [8] | Command-line Software | Whole-genome association analysis | Robust LD calculation and pruning/clumping for large datasets. |

| LocusZoom [10] | Web Tool / R Script | Regional visualization of GWAS results | Generates plots integrating association statistics, LD, and gene annotation. |

| LDlink [8] | Web Suite / API | Query LD for specific variants in population groups | Provides population-specific LD information without local computation. |

| LDstore2 [8] | Command-line Software | High-speed LD calculation | Efficiently pre-computes LD for very large reference panels. |

| Haploview | Desktop Application | LD and haplotype analysis | User-friendly GUI for visualizing LD blocks and haplotype estimation. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) and how is it different from genetic linkage?

Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) is the non-random association of alleles at different loci in a population. This means that certain combinations of alleles at different locations on the genome occur together more or less often than would be expected by chance alone. It is quantified as the difference between the observed haplotype frequency and the frequency expected if alleles were independent: D = pAB - pApB [2] [1]. It is crucial to distinguish this from genetic linkage. Genetic linkage refers to the physical proximity of genes on the same chromosome, which reduces the chance of recombination separating them in an individual. LD, however, is a population-level concept describing statistical associations, which can occur even between unlinked loci due to forces like population structure or selection [1].

2. Which LD measure should I use, r² or D', and why?

The choice between r² and D' depends on your research goal, as each measure provides different information. The table below summarizes their core differences [3]:

| Aspect | r² (Squared Correlation) | D' (Standardized Disequilibrium) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Tag SNP selection, GWAS power, imputation quality | Inferring historical recombination, haplotype block discovery |

| What it Captures | How well one variant predicts another; variance explained | Whether recombination has likely occurred between sites; historical decay |

| Sensitivity to MAF | High (penalizes mismatched minor allele frequencies) | Low (can be high even for rare alleles) |

| Interpretation | 0.2: Low; 0.5: Moderate; ≥0.8: Strong for tagging | ≥0.9 often indicates "complete" LD given the sample |

| Key Pitfall | Underestimates linkage for rare variants | Can be inflated by small sample sizes and rare alleles |

3. What are the main evolutionary forces that affect LD patterns?

Linkage disequilibrium is shaped by a balance of several population genetic forces. The following table outlines their primary effects [2] [3] [11]:

| Evolutionary Force | Effect on Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) |

|---|---|

| Recombination | Decreases LD. Crossovers break down non-random associations between loci over time. The rate of decay is proportional to the recombination frequency [2] [12]. |

| Genetic Drift | Increases LD. In small populations, random sampling can cause alleles at different loci to be inherited together by chance, even if they are unlinked [3] [11]. |

| Selective Sweeps | Increases LD. When a beneficial mutation sweeps through a population, it "hitchhikes" linked neutral variants along with it, creating a region of high LD around the selected site [2] [3]. |

| Population Bottlenecks | Increases LD. A drastic reduction in population size reduces genetic diversity and causes genome-wide increases in LD due to enhanced genetic drift [3]. |

| Mutation | Creates new LD. A new mutation arises on a specific haplotype background, initially putting it in complete LD with all surrounding variants [3]. |

| Population Admixture | Creates long-range LD. The mixing of previously separated populations generates associations between alleles across the genome [3]. |

Figure 1: Evolutionary Forces Affecting LD. Forces like selection and drift create or maintain LD, while recombination acts to break it down.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Spurious Associations in Association Studies

Issue: Your genome-wide association study (GWAS) is identifying associations that are statistically significant but are likely false positives due to population structure rather than true biological linkage.

Background: Population structure, such as substructure or admixture, can create long-range LD across the genome. If a trait (e.g., height) is more common in one subpopulation, alleles that are common in that subpopulation will appear associated with the trait, even if they are not causally related [1] [3].

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Detect Population Stratification:

- Method: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on your genotype data.

- Protocol: Use software like PLINK to generate principal components (PCs). Plot the first few PCs against each other. Clusters of individuals indicate potential population subgroups.

- Expected Outcome: Identification of cryptic relatedness and population subgroups within your sample.

Account for Structure in Association Testing:

- Method: Include the top principal components (typically 5-10) as covariates in your association model.

- Protocol: In your association analysis command (e.g., in PLINK using

--logisticor--linear), specify the principal components as covariates. This statistically adjusts for ancestry differences. - Expected Outcome: A quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot of the p-values that shows less deviation from the null expectation, indicating a reduction in false positives.

Validate with LD-aware Methods:

- Method: Use a genetic relationship matrix (GRM) to model relatedness in a mixed model.

- Protocol: Employ tools like GCTA or GEMMA, which use a GRM as a random effect to account for all levels of relatedness, providing a robust control for population structure.

Problem: Inefficient Tagging and Fine-mapping Resolution

Issue: Your SNP array is not efficiently capturing genetic variation, or you are unable to narrow down a causal variant due to extensive LD in a region.

Background: The power of GWAS and the resolution of fine-mapping depend heavily on local LD patterns. If tag SNPs are poorly chosen or if a region has long, uninterrupted LD (haplotype blocks), it can be difficult to pinpoint the true causal variant [2] [3].

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Evaluate and Prune Your Marker Set:

- Method: Use LD-based pruning to create a set of mutually independent SNPs for analysis.

- Protocol: In PLINK, use the command

--indep-pairwise 50 5 0.1. This performs a sliding window analysis (window size 50 SNPs, sliding 5 SNPs at a time), removing one SNP from any pair with an r² > 0.1. This reduces redundancy and is useful for PCA or other analyses.

Define Haplotype Blocks:

- Method: Identify regions of strong LD with minimal historical recombination.

- Protocol: Use software like Haploview with a definition such as the "four-gamete rule" or a confidence interval method to define block boundaries. This helps in selecting tag SNPs that represent the variation within each block [2] [3].

Leverage Trans-ethnic LD Differences:

- Method: Perform meta-analysis across populations with different genetic ancestries.

- Protocol: Harmonize GWAS summary statistics from different populations. Because LD patterns and haplotype block structures differ across populations, a variant that is in high LD with the causal variant in one population may not be in another. This can help break apart correlations and narrow the credible set of putative causal variants [3].

Figure 2: LD Decay via Recombination. Over generations, recombination breaks down ancestral haplotypes, creating shorter segments of LD.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Application in LD Research |

|---|---|---|

| PLINK | Whole-genome association analysis toolset | The industry standard for processing genotype data, calculating LD matrices, and performing LD-based pruning/clumping for QC and analysis [3]. |

| Haploview | Visualization and analysis of LD patterns | Specialized for plotting LD heatmaps (using D' or r²), defining haplotype blocks, and visualizing recombination hotspots [3]. |

| VCFtools | Utilities for working with VCF files | A flexible toolset for processing VCF files, capable of calculating LD statistics in genomic windows directly from variant call data [3]. |

| LocusZoom | Regional visualization of GWAS results | Creates publication-quality plots of association signals in a genomic region, overlayed with LD information (r²) from a reference panel to show correlation with the lead SNP [3]. |

| Scikit-allel (Python) | Python library for genetic data | Provides programmable functions for computing LD matrices and statistics, ideal for custom analyses and integrating LD calculations into larger bioinformatics pipelines [3]. |

| HapMap & 1000 Genomes | Public reference datasets | Provide curated genotype data from multiple populations, serving as the standard reference panels for imputation and for studying population-specific LD patterns [2]. |

Linkage disequilibrium (LD), the nonrandom association of alleles at different loci, serves as a sensitive indicator of the population genetic forces that structure genomes [2]. The patterns of LD decay and haplotype block structure across genomes provide valuable insights into past evolutionary and demographic events, including population bottlenecks, expansions, migrations, and domestication histories [13] [14]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these patterns is essential for designing effective association studies, mapping disease genes, and interpreting the evolutionary history of populations [2] [14]. This technical support center addresses key methodological considerations and troubleshooting guidance for analyzing LD decay and haplotype blocks within the broader context of association studies research.

Understanding LD Decay and Haplotype Blocks

Troubleshooting Guide: Common LD Analysis Challenges

FAQ: Why do my GWAS results feel unstable, with inconsistent signals across analyses? This instability often stems from marker spacing that ignores the true LD decay pattern in your study population. When LD-based pruning is too aggressive or not aggressive enough, it creates collinearity issues that inflate false positives or weaken fine-mapping resolution. To resolve this, calculate the LD decay curve for your specific population and set marker density according to the half-decay distance (H50) [15].

FAQ: How do I determine the appropriate SNP density for genome-wide association studies? The required density depends directly on your population's LD decay pattern. Calculate the half-decay distance (H50) - the point where r² drops to half the short-range plateau value. For populations with:

- Fast decay (H50 ≤ 50 kb): Aim for 1 marker every 20-40 kb

- Moderate decay (H50 ~ 100-250 kb): Space markers 50-100 kb apart

- Slow decay (H50 > 250 kb): Use 1 marker every 50-100 kb as a baseline, but identify and handle long-range LD regions separately [15]

FAQ: Why do haplotype block boundaries differ between studies of the same genomic region? Block boundaries vary due to:

- Different block-defining methods (D′-based, four-gamete rule, LD segmentation)

- Varying threshold parameters (r² or D′ cutoffs)

- Sample characteristics (population structure, sample size)

- Marker properties (SNP density, allele frequency spectra) [15] [14]

Always document your block-defining method, threshold parameters, and MAF filters to ensure reproducibility.

FAQ: How does population history affect LD patterns that I observe in my data? Demographic history strongly influences LD patterns:

- Bottlenecks and founder events increase LD extent (e.g., European vs. Chinese pig breeds)

- Admixture events create long-range LD patterns

- Population expansion decreases overall LD levels

- Selection creates localized regions of high LD around selected alleles [13] [14]

These differences necessitate population-specific study designs and careful interpretation of results.

Quantitative LD Decay Reference Values

Table 1: LD Decay Characteristics Across Species and Populations

| Species/Population | Half-Decay Distance (H50) | Extension Range | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Pig Breeds | ~2 cM | Up to 400 kb | Modern breeding programs, small effective population size [13] |

| Chinese Pig Breeds | ~0.05 cM | Generally <10 kb | Larger ancestral population size [13] |

| European Wild Boar | Intermediate level | Intermediate | Natural population history [13] |

| Human (per Kruglyak simulation) | <3 kb | Limited | Population history under theoretical assumptions [2] |

| Human (empirical observation) | Varies by region | Up to 170 kb | Recombination hotspots, selection, demographic history [14] |

Table 2: Haplotype Block Characteristics and Definition Methods

| Block Definition Method | Key Principle | Best Application Context | Important Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| D′-based (Gabriel criteria) | Groups markers with strong evidence of limited recombination | Populations with clear block-like structure | Sensitive to sample size and allele frequency [15] [14] |

| Four-gamete rule | Detects historical recombination through haplotype diversity | Evolutionary studies, ancestral inference | May overpartition in high-diversity populations [15] |

| LD segmentation/HMM | Models correlation transitions explicitly | Uneven marker density, mixed panels | Computationally intensive but flexible [15] |

| Fixed window approaches | Uses predetermined physical or genetic distances | Initial screening, standardized comparisons | May not reflect biological recombination boundaries [15] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: LD Decay Analysis Workflow

Objective: Calculate and interpret LD decay patterns from genotype data.

Step 1 - Data Quality Control (Essential Preprocessing)

- Sample-level QC: Remove duplicates, exclude samples with low DNA concentration (<10 ng/μL), identify and discard contaminated samples [5]

- Variant-level QC: Filter SNPs with >20% missingness, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p-value < 1×10⁻⁶, and minor allele frequency (MAF) <1-5% depending on sample size [5]

- Batch effect correction: Apply when data generated in multiple batches

Step 2 - LD Calculation with PLINK

Key Parameters:

--maf 0.01: Filters rare variants (adjust based on sample size)--thin 0.1: Randomly retains 10% of sites for computational efficiency--ld-window-kb 1000: Sets maximum distance between SNP pairs for LD calculation-r2 gz: Outputs compressed r² values [16]

Step 3 - Calculate Average LD Across Distance Bins

- Use custom scripts (e.g.,

ld_decay_calc.py) to bin SNP pairs by distance [16] - Calculate mean/median r² for each distance bin (typically 1-100 kb windows)

- Generate LD decay curve: plot distance vs. r² values

Step 4 - Interpretation and Application

- Identify short-range plateau: Height indicates local redundancy

- Determine H50: Distance where r² drops to half of short-range value

- Note tail behavior: Extended tails suggest long-range LD regions needing special handling [15]

Protocol 2: Haplotype Block Definition and Analysis

Objective: Identify and characterize haplotype blocks in genomic data.

Step 1 - Data Preparation and LD Calculation

- Use quality-controlled genotype data

- Calculate pairwise LD (r² or D′) following Protocol 1, but without thinning

- Focus on autosomal chromosomes separately

Step 2 - Block Definition with Haploview

- Input: PLINK format files (.ped and .info)

- Key Parameters:

- Gabriel et al. method: Creates blocks where 95% of pairwise D′ values fall within confidence intervals [14]

- MAF filter: Typically 0.05-0.01 depending on sample size

- Minimum D′: Often set to 0.8 for block boundaries

- Output: Block boundaries, haplotype frequencies, tag SNP suggestions

Step 3 - Block Characterization and Validation

- Calculate block statistics: size distribution, number of haplotypes per block, diversity measures

- Compare blocks across populations or subgroups

- Validate using functional annotations: gene content, regulatory elements

Step 4 - Tag SNP Selection

- Within each block, identify minimal SNP set that captures haplotype diversity

- Aim for r² ≥ 0.8 between tag SNPs and untested variants [15]

- Consider cross-population performance if study will be applied broadly

Visualization Workflow

LD Analysis Workflow Diagram

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for LD Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLINK | LD calculation, basic QC | Fast, memory-efficient, standard format support | Command-line only, limited visualization [16] |

| Haploview | Haplotype block visualization and analysis | Interactive GUI, multiple block definitions, tag SNP selection | Java-dependent, less actively developed [15] [17] |

| PHASE | Haplotype inference accounting for LD decay | Coalescent-based prior, handles recombination | Computationally intensive for large datasets [18] |

| LocusZoom | LD visualization for specific regions | Regional association plots with LD information | Requires specific input formats [5] |

| R/GenABEL | Comprehensive LD analysis in R | Programmatic, reproducible, customizable | Steeper learning curve [5] |

Advanced Considerations for Association Studies

Troubleshooting Guide: Advanced LD Challenges

FAQ: How should I handle long-range LD regions in my analysis? Long-range LD regions (where r² > 0.2 persists beyond 250 kb) require special handling:

- Identify through extended tail in LD decay curve

- Analyze separately from genome-wide background

- Document exceptions thoroughly in methods and results

- Consider biological causes: inversions, structural variants, recombination cold spots, selective sweeps [15]

FAQ: My association study needs to work across multiple populations. How do I design markers for cross-population transfer?

- Anchor design in population with best characterization/power

- Compute cross-ancestry r² coverage for same tag SNP set

- Add ancestry-specific supplements in poorly tagged regions rather than complete redesign

- Validate empirically in each target population before full implementation [15]

FAQ: How do I account for uncertainty in haplotype phase inference?

- Use methods that explicitly account for phase uncertainty (e.g., LAMARC, PHASE) [2] [18]

- Avoid treating inferred haplotypes as observed data in downstream analyses

- Consider likelihood-based approaches that incorporate phase uncertainty directly

- For critical applications, consider molecular haplotyping methods

FAQ: What are the implications of different LD patterns for rare variant association tests? Burden tests for rare variants prioritize:

- Trait-specific genes with limited pleiotropy

- Genes under stronger purifying selection

- Different biological aspects than common variant GWAS [19]

Common variant GWAS can identify more pleiotropic genes, making the approaches complementary rather than contradictory.

Reporting Standards and Quality Assurance

Minimum Reporting Requirements for LD Analysis:

- Population description: sample size, ancestry, collection details

- QC filters: MAF threshold, missingness thresholds, HWE p-value cutoffs

- LD measures: Specify whether using r², D′, or both with justification

- Block definition: Method and all parameters clearly stated

- Visualization details: Color scales, binning methods, reference builds

Critical QC Checks:

- Stratification: Ensure decay and blocks computed within ancestry groups

- Scale consistency: Use same r² scales across all figures

- Marker density effects: Report how density affects block boundaries

- Software versions: Document all tools and versions used [15]

LD decay and haplotype block analysis provide powerful windows into population history and essential frameworks for designing robust association studies. By implementing the troubleshooting guidance, experimental protocols, and analytical workflows presented in this technical support center, researchers can avoid common pitfalls and generate biologically meaningful interpretations of LD patterns. The integration of these approaches within association study frameworks enables more effective gene mapping, better understanding of evolutionary history, and ultimately, more successful translation of genetic discoveries into clinical and agricultural applications.

LD as a Tool for Inferring Demographic Events and Selection Signatures

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My IBD-based inference of effective population size shows spurious oscillations in the very recent past. How can I get more stable estimates?

A1: Spurious oscillations are a known challenge in demographic inference. To address this:

- Use Regularized Methods: Implement algorithms that incorporate a statistical prior favoring models with minimal population size fluctuations. This regularization prevents over-interpretation of noise as demographic events. The HapNe method, for example, uses such a maximum-a-posteriori (MAP) estimator to produce stable and accurate effective population size (Ne) trajectories [20].

- Leverage Linkage Disequilibrium: If phasing quality is a concern, use methods like HapNe-LD that infer Ne(t) from LD patterns without requiring phased data. This approach is robust for analyzing low-coverage or ancient DNA [20].

- Apply a Peeling Technique: For LD-based analyses, adjust the estimated mean LD ((\ell_g)) by subtracting the influence of population structure captured by the top eigenvalues of the genetic relationship matrix (GRM). This helps isolate the demographic signal [4].

Q2: How can I accurately estimate genome-wide linkage disequilibrium for a biobank-scale dataset without facing prohibitive computational costs?

A2: Traditional LD computation scales with (\mathcal{O}(nm^2)), which is infeasible for biobank data. The solution is to use stochastic approximation methods.

- Algorithm: Employ the X-LDR algorithm, which uses Girard-Hutchinson stochastic trace estimation [4].

- Mechanism: This method approximates the trace of the squared GRM ((\text{tr}(\mathbf{K}^2))) without ever forming the complete LD matrix. The core identity used is (\ellg \approx \frac{\text{tr}(\mathbf{K}^2)}{n^2}), where (\ellg) is the averaged LD across all SNP pairs [4].

- Outcome: This reduces computational complexity from (\mathcal{O}(nm^2)) to (\mathcal{O}(nmB)), where (B) is the number of iterations, making genome-wide LD estimation feasible for hundreds of thousands of samples [4].

Q3: What is the most effective way to perform genetic traceability and identify selection signatures in an admixed local breed with an unclear origin?

A3: A multi-faceted genomic approach is required.

- Genetic Traceability: Use a combination of analytical strategies to identify ancestral donor breeds and quantify their genetic contributions. Methods include:

- Genomic similarity analysis (e.g., Identity-By-State Neighbor-Joining trees, Fst trees) [21].

- Outgroup f3 statistics to measure shared genetic drift [21].

- Normalized Identity-By-Descent (nIBD) to quantify recent shared ancestry [21].

- Hybridization detection with tools like HyDe to test for historical admixture [21].

- Selection Signature Detection: Once ancestry components are determined, use them as a novel basis for detecting selection signatures. This can reveal genes associated with local adaptation and unique phenotypes (e.g., polydactyly, meat flavor) within the admixed population [21].

Q4: How can I analyze population genetic data stored as tree sequences with deep learning models?

A4: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) require alignments, but tree sequences are a more efficient data structure. To bridge this gap:

- Model Choice: Use a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN), which is a generalization of CNNs designed to operate directly on graph-like data [22].

- Input: The GCN takes the inferred sequence of marginal genealogies (the tree sequence) as its direct input.

- Application: This approach has been shown to match or even exceed the accuracy of alignment-based CNNs on tasks like recombination rate estimation, selective sweep detection, and introgression detection [22].

Q5: My GWAS suffers from confounding due to population stratification. Are there methods that can handle this while also modeling linkage disequilibrium?

A5: Yes, advanced regularization methods are designed for this specific challenge.

- Method: The Sparse Multitask Group Lasso (SMuGLasso) method is well-suited for stratified populations [23].

- Framework: It formulates the problem using a multitask learning framework where:

- Tasks represent different genetic subpopulations.

- Groups are population-specific Linkage-Disequilibrium (LD) blocks of correlated SNPs [23].

- Advantage: This method incorporates an additional regularization penalty to select for population-specific genetic variants, improving the identification of true associations in the presence of population structure and LD [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Effective Population Size Inference

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable Ne(t) estimates with spurious oscillations. | Lack of model regularization and overfitting to noise in IBD segment data [20]. | Use the HapNe-IBD method with its built-in maximum-a-posteriori (MAP) estimator and bootstrap resampling to obtain confidence intervals [20]. |

| Biased inference in low-coverage or ancient DNA data. | Reliance on accurate phasing and IBD detection, which is difficult with low-quality data [20]. | Switch to an LD-based method like HapNe-LD, which can be applied to unphased data and is robust for low-coverage or ancient DNA, even with heterogeneous sampling times [20]. |

| Inefficient computation of genome-wide LD for large cohorts. | Standard LD computation has (\mathcal{O}(nm^2)) complexity, which is prohibitive for biobank data [4]. | Implement the X-LDR algorithm to stochastically estimate the mean LD ((\ell_g)) with (\mathcal{O}(nmB)) complexity [4]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Inferring Recent Effective Population Size with HapNe-LD

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Compile your genotype data (VCF format). No phasing is required. Ensure you have an appropriate genetic map for the population.

- Step 2: Calculate LD Summary Statistics. Compute the necessary long-range LD statistics from the unphased genotypes across the genome.

- Step 3: Run HapNe-LD.

- Input: LD statistics and the genetic map.

- Process: The tool will optimize a composite likelihood model linking the LD distribution to the effective population size trajectory, using regularization to avoid spurious fluctuations.

- Output: A Maximum-A-Posteriori (MAP) estimate of Ne(t) over the last ~2000 years, with approximate confidence intervals available via bootstrap resampling [20].

- Step 4: Interpret Results. Analyze the Ne(t) trajectory, noting periods of expansion, bottleneck, or stability. Correlate significant changes with historical or ecological records.

Issue 2: Managing Linkage Disequilibrium in Large-Scale Genomics

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to draft a genome-wide LD atlas due to computational limits. | The (\mathcal{O}(nm^2)) scaling of traditional methods [4]. | Use the X-LDR framework to generate high-resolution LD grids efficiently [4]. |

| LD patterns are confounded by population structure. | The genetic relationship matrix (GRM) eigenvalues reflect stratification, inflating LD estimates [4]. | Apply a peeling technique: adjust (\ellg) by subtracting the sum of squared normalized eigenvalues ((\lambdak/n)^2) from the top (q) components of the GRM to correct for structure [4]. |

| Interchromosomal LD is pervasive and complicates analysis. | Underlying population structure creates correlations even between different chromosomes [4]. | Model this using the LD-eReg framework, which identifies that interchromosomal LD is often proportional to the product of the participating chromosomes' eigenvalues (Norm II pattern) [4]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Creating a Genome-Wide LD Atlas with X-LDR

- Step 1: Data Input. Prepare a standardized genotypic matrix (\mathbf{X}) for (n) individuals and (m) SNPs.

- Step 2: Stochastic Trace Estimation. Use the X-LDR algorithm to approximate (\text{tr}(\mathbf{K}^2)), where (\mathbf{K} = \frac{1}{m} \mathbf{X} \mathbf{X}^T) is the GRM. This is done without computing the full (m \times m) LD matrix.

- Step 3: Calculate Mean LD. Compute the average squared correlation ((\ellg)) across the genome using the formula: (\ellg = \frac{\text{tr}(\mathbf{K}^2)-n}{n^2+n}) [4].

- Step 4: Partition and Analyze. Calculate (\ellg) for individual chromosomes ((\elli)) and for pairs of chromosomes ((\ell{ij})). Use LD-dReg to regress (\elli) against the reciprocal of chromosome length ((x_i^{-1})) to assess the Norm I pattern typical of random mating [4].

Workflow: From Genetic Data to Demographic Inference

Issue 3: Detecting Selection and Ancestry in Admixed Populations

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertain genetic origin of a local breed with mixed phenotypes. | Historical admixture and lack of pedigree records obscure ancestry [21]. | Apply a composite genomic framework: combine IBS NJ-trees, Fst trees, Outgroup f3, and nIBD to identify donor breeds without prior history [21]. |

| Difficulty distinguishing selection signals from admixture patterns. | Genomic regions under selection can mimic ancestry tracts [21]. | Use ancestral components identified during traceability analysis as a baseline for selection scans. This controls for the background ancestry and highlights true selection signatures [21]. |

| Identifying genes behind specific traits in a local breed. | Polygenic nature of many traits and small population sizes [21]. | Perform selection signature analysis on defined ancestral components. This can reveal genes associated with unique features like polydactyly, intramuscular fat, or spermatogenesis [21]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Genetic Traceability and Selection Analysis

- Step 1: Population Genotyping. Sequence or genotype the target breed (e.g., Beijing-You chicken) and a wide panel of potential ancestral breeds and outgroups (e.g., junglefowl) [21].

- Step 2: Variant Filtering. Perform stringent quality control (e.g., with PLINK): filter for missingness, minor allele frequency (MAF), and prune for linkage disequilibrium to obtain a high-quality SNP set [21].

- Step 3: Ancestry Deconvolution.

- Step 4: Ancestry-Aware Selection Scan. Using the estimated ancestry proportions, perform selection signature analyses (e.g., for Fst or XP-EHH) within each ancestral genomic component to find regions associated with local adaptation [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and data resources for research in this field.

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in LD/Demographic Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| HapNe [20] | Software Package | Infers recent effective population size (Ne). | Infers Ne(t) over the past ~2000 years from either IBD segments (HapNe-IBD) or LD patterns (HapNe-LD), with regularization for stability. |

| X-LDR [4] | Algorithm | Efficiently estimates genome-wide LD. | Enables the creation of LD atlases for biobank-scale data by reducing computational complexity from (\mathcal{O}(nm^2)) to (\mathcal{O}(nmB)). |

| SMuGLasso [23] | GWAS Method | Handles population stratification in association studies. | Uses a multitask group lasso framework to identify population-specific risk variants while accounting for LD structure. |

| Tree Sequences [22] | Data Structure | Efficiently stores genetic variation and genealogy. | Provides a compact, lossless format for population genetic data, enabling direct analysis with Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs). |

| HyDe [21] | Software Tool | Detects hybridization and gene flow. | Identifies historical admixture events and potential parental populations for a target breed, fundamental for genetic traceability. |

| PLINK [21] | Software Toolset | Performs core genome data management and analysis. | Used for standard quality control (QC), filtering (MAF, missingness), and calculating basic statistics like IBS for population analyses. |

| GCN (Graph Convolutional Network) [22] | Machine Learning Model | Learns directly from graph-structured data. | Applied directly to tree sequences for inference tasks like recombination rate estimation and selection detection, bypassing alignment steps. |

| LD-dReg / LD-eReg [4] | Analytical Framework | Models global LD patterns. | Characterizes fundamental norms of LD, such as its relationship with chromosome length (Norm I) and interchromosomal correlations (Norm II). |

Data Analysis Pathway for Selection and Demography

Applied LD Analytics: From GWAS and Fine-Mapping to Polygenic Risk Scores

LD as the Bedrock of Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

Core Concept FAQs

What is Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) and why is it fundamental to GWAS? Linkage disequilibrium (LD) is the non-random association of alleles at different loci in a population. It is quantified as the difference between the observed haplotype frequency and the frequency expected if alleles were associating independently: D = p~AB~ - p~A~p~B~, where p~AB~ is the observed haplotype frequency and p~A~p~B~ is the product of the individual allele frequencies [1] [8]. In GWAS, LD is the fundamental property that allows researchers to identify trait-associated genomic regions without directly genotyping causal variants. Because genetic variants are correlated within haplotype blocks, a genotyped single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) can "tag" nearby ungenotyped causal variants, making genome-wide scanning feasible and cost-effective [24] [2].

How does LD differ from genetic linkage? Genetic linkage refers to the physical proximity of loci on the same chromosome, which affects their co-inheritance within families. Linkage disequilibrium, in contrast, describes the correlation between alleles at a population level. Linked loci may or may not be in LD, and unlinked loci can occasionally show LD due to population structure [1].

What factors influence LD patterns in a study? LD patterns are not uniform across the genome or across populations. Key influencing factors include:

- Recombination rates: LD is higher in low-recombination regions [25].

- Population history: Bottlenecks and founder effects increase LD; populations of more recent descent (e.g., Finns) typically show larger LD blocks than older populations (e.g., Africans) [25].

- Natural selection: Selective sweeps can create strong, long-range LD around a selected allele [2].

- Genetic drift: Random fluctuations in allele frequencies, especially in small populations, can generate LD [1].

Technical Implementation & Analysis

Key LD Metrics and Their Interpretation

Different normalized measures of LD are used, each with specific properties and interpretations. The most common measures are derived from the core coefficient of linkage disequilibrium, D [26].

Table 1: Common Measures of Linkage Disequilibrium

| Measure | Formula | Interpretation | Primary Use Case | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | ( D = p{AB} - pAp_B ) | Raw deviation from independence; depends on allele frequencies [1]. | Foundational calculation; not for comparisons. | ||||

| D' | ( | D' | = \frac{ | D | }{D_{max}} ) | Normalizes D to its theoretical maximum given the allele frequencies; ranges 0-1 [26] [8]. | Assessing recombination history; values near 1 suggest no historical recombination. |

| r² | ( r^2 = \frac{D^2}{pA(1-pA)pB(1-pB)} ) | Squared correlation coefficient between two loci; ranges 0-1 [1] [26]. | Power calculation for association studies; 1/r² is the sample size multiplier. |

Figure 1: A simplified workflow for a GWAS, highlighting key steps where LD is a critical consideration.

Essential Protocols for LD Handling in GWAS

Protocol: LD Pruning for Population Structure Analysis Purpose: To select a subset of roughly independent SNPs for calculating principal components (PCs) to control for population stratification.

- Software: Use PLINK.

- Method: Apply the

--indep-pairwisecommand. - Typical Parameters: A window size of 50 SNPs, a step size of 5, and an r² threshold of 0.1 to 0.2 [27] [28].

- Rationale: This identifies and removes one SNP from any pair within the sliding window that exceeds the specified r² threshold, reducing multicollinearity.

Protocol: LD Clumping for Result Interpretation Purpose: To identify independent, significant signals from GWAS summary statistics by grouping SNPs in LD.

- Software: Use PLINK or PRSice.

- Method: Clumping retains the most significant SNP (index SNP) in a region and removes all other SNPs in high LD with it.

- Typical Parameters: An r² threshold (e.g., 0.1 to 0.5) and a physical distance threshold (e.g., 250 kb) [28].

- Output: A list of independent lead SNPs, simplifying downstream analysis and interpretation.

Protocol: Tag SNP Selection for Genotyping Arrays Purpose: To maximize genomic coverage while minimizing the number of SNPs that need to be genotyped.

- Data: A reference panel with dense genotype data from a relevant population (e.g., 1000 Genomes Project).

- Method: Within a defined genomic window, select a minimal set of SNPs such that all other SNPs are in high LD (r² > 0.8) with at least one tag SNP [25].

- Outcome: A cost-effective SNP array that captures the majority of common genetic variation.

Troubleshooting Common LD Issues

Problem: Inflated False Positive Rates in GWAS

- Potential Cause: Population stratification, where underlying population structure creates LD between unlinked loci, confounding the association signal [28].

- Solution:

- Pre-analysis: Perform LD pruning to create a set of independent SNPs.

- During Analysis: Calculate principal components (PCs) from the pruned SNP set and include them as covariates in the association model [28].

Problem: Low Power to Detect Association

- Potential Cause: The causal variant is rare or has a low correlation (r²) with any of the genotyped tag SNPs on the array [24] [26].

- Solution:

- Study Design: Ensure the sample size is sufficient. The effective sample size is reduced by a factor of r² between the tag and causal SNP.

- Post-analysis: Use imputation to infer ungenotyped variants based on LD patterns in a reference panel, increasing resolution.

Problem: Difficulty in Fine-Mapping the Causal Variant

- Potential Cause: Extensive LD across a large genomic region means many highly correlated SNPs show similar association signals, making it impossible to pinpoint the true causal variant [25].

- Solution:

- Increase Sample Size: To improve the resolution of association signals.

- Multi-ancestry Meta-analysis: LD patterns differ across populations. Combining data can break down large LD blocks, narrowing the associated region [2].

- Functional Annotation: Integrate functional genomic data (e.g., chromatin states, promoter marks) to prioritize likely causal variants from a list of correlated candidates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for LD-Informed Genetic Research

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLINK [8] [28] | Software Toolset | Performs core GWAS operations, QC, and LD calculations. | Industry standard; includes functions for LD pruning, clumping, and basic association testing. |

| LDlink [25] [8] | Web Suite / R Package | Queries LD patterns in specific human populations from pre-computed databases. | Allows researchers to check LD for their SNPs of interest in multiple populations without handling raw data. |

| International HapMap Project [24] | Reference Database | Catalogued common genetic variants and their LD patterns in initial human populations. | Pioneering resource that enabled the first generation of GWAS. |

| 1000 Genomes Project [28] | Reference Database | Provides a deep catalog of human genetic variation, including rare variants, across diverse populations. | A key reference panel for imputation and tag SNP selection in follow-up studies. |

| LDstore2 [8] | Software | Efficiently calculates and stores massive LD matrices from genotype data. | Designed for high-performance computation of LD for large-scale studies. |

Figure 2: How population structure causes spurious associations and the corrective role of LD-based methods.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Poor Imputation Accuracy in Diverse Cohorts

Problem: Imputation accuracy is significantly lower in non-European or admixed study populations.

- Symptoms: Low imputed r² values, particularly for rare variants (MAF < 1%); inconsistent association results across populations.

- Causes: Reference panel mismatch; differential linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns; tag SNPs selected from inappropriate populations.

Solutions:

- Use Population-Matched Reference Panels

- Action: For African-ancestry populations, incorporate reference panels like the 1000 Genomes YRI (Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria) or AFR super population. For admixed populations, use combined or ancestry-specific panels [29] [30].

- Validation: Check imputation accuracy metrics (e.g., mean r²) via leave-one-out cross-validation within your target population [29].

Implement Multi-Ethnic Tag SNP Selection

- Action: Utilize frameworks like TagIT that select tag SNPs based on multi-population reference panels (e.g., 1000 Genomes 26 populations) rather than single-population LD [29].

- Validation: Prioritize tag SNPs that contribute information across multiple populations simultaneously. This has been shown to improve rare variant imputation accuracy by 0.5-7.1%, depending on array size and population [29].

Optimize LD Thresholds by Population

- Action: For populations with lower LD (e.g., African), use less stringent r² thresholds (0.2) for tag SNP selection. For populations with extended LD (e.g., European, Asian), higher thresholds (0.5-0.8) may be sufficient [29] [3].

- Validation: Evaluate performance via mean imputed r² at untyped sites rather than pairwise LD coverage [29].

Table 1: Recommended r² Thresholds by Population and Variant Frequency

| Population Group | Common Variants (MAF >5%) | Low-Frequency Variants (MAF 1-5%) | Rare Variants (MAF <1%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| African ancestry | r² ≥ 0.2 | r² ≥ 0.2 | r² ≥ 0.2 |

| European ancestry | r² ≥ 0.5 | r² ≥ 0.5 | r² ≥ 0.8 |

| East Asian ancestry | r² ≥ 0.5 | r² ≥ 0.5 | r² ≥ 0.8 |

| Admixed populations | r² ≥ 0.2 | r² ≥ 0.2 | r² ≥ 0.5 |

Guide 2: Computational Challenges in Large-Scale Datasets

Problem: Tag SNP selection and genotype imputation are computationally prohibitive for whole-genome sequencing data or large cohorts.

- Symptoms: Memory allocation errors; processing times of days or weeks; inability to complete analysis.

- Causes: Naïve pairwise LD computation; inefficient algorithms; inadequate computational resources.

Solutions:

- Implement Efficient LD Pruning Algorithms

- Action: Use optimized algorithms like SNPrune for detecting SNPs in high LD. SNPrune identifies pairs of SNPs in complete or high LD by first sorting SNPs by minor allele count, then comparing only those with similar MAF, dramatically reducing computations [31].

- Performance: SNPrune has demonstrated 12-170x faster performance compared to PLINK for large sequence datasets with 10.8 million SNPs [31].

Utilize LD-Based Marker Pruning

- Action: For genomic prediction applications, prune markers based on LD to reduce redundancy. Studies show that a sequencing depth of 0.5× with LD-pruned SNP density of 50K can achieve prediction accuracy comparable to whole sequencing depth [32] [33].

- Validation: Assess impact on genomic prediction accuracy using cross-validation within your study population.

Apply Sliding Window Approaches

- Action: For genome-wide analyses, implement sliding window approaches (typically 200-1000 kb) to compute LD rather than all pairwise combinations [3].

- Validation: Compare results from window-based approaches to full analysis on chromosome subsets to ensure critical associations aren't missed.

Table 2: Computational Performance Comparison of LD Pruning Tools

| Tool | Primary Use | Strengths | Limitations | Typely Processing Time for 10M SNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNPrune | High-LD pruning | Extremely fast; efficient algorithm | Less feature-rich than PLINK | ~21 minutes (10 threads) |

| PLINK | General LD analysis | Comprehensive features; GWAS standard | Slower for genome-wide pruning | ~6 hours (sliding window) |

| VCFtools | LD from VCF files | Simple; VCF-native | Limited pruning capabilities | Varies by dataset size |

| scikit-allel | Programmable LD in Python | Flexible; customizable | Requires Python programming skills | Varies by implementation |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between r² and D' measures of LD, and when should each be used for tag SNP selection?

r² and D' answer different questions in tag SNP selection. Use r² (squared correlation) when evaluating how well one variant predicts another, as it directly impacts GWAS power and imputation accuracy. Use D' (standardized disequilibrium) when investigating historical recombination patterns or defining haplotype block boundaries [3]. For tag SNP selection, r² thresholds are preferred because they reflect predictive utility and are bounded by allele frequencies, preventing overestimation of tagging efficiency for variants with mismatched MAF [34] [3]. Practical implementation typically uses r² thresholds of 0.2-0.5 for pruning, and ≥0.8 for strong tagging in array design [29] [3].

FAQ 2: How does effective population size (Nₑ) impact tag SNP selection strategies across different human populations?

Effective population size profoundly influences LD patterns and thus tag SNP strategies. African-ancestry populations have larger Nₑ, resulting in shorter LD blocks and more rapid LD decay. Consequently, tag SNPs capture approximately 30% fewer other variants than in non-African populations, requiring higher marker densities for equivalent genomic coverage [29]. Conversely, European and Asian populations have smaller Nₑ due to founder effects and bottlenecks, creating longer LD blocks where fewer tag SNPs can capture larger genomic regions [29] [35]. These differences necessitate population-specific tag SNP selection for optimal efficiency.

FAQ 3: What are the advantages of coalescent-based imputation methods compared to standard LD-based approaches in structured populations?

Coalescent-based imputation methods explicitly model the genealogical history of haplotypes rather than relying solely on observed LD patterns. Simulations reveal that in LD-blocks, coalescent-based imputation can achieve higher and less variable accuracy than standard methods like IMPUTE2, particularly for low-frequency variants [36]. This approach naturally accommodates demographic history, including population growth and structure, without requiring external reference panels with matching LD patterns. However, practical implementation requires further methodological development to incorporate recombination and reduce computational burden [36].

FAQ 4: How can researchers evaluate tag SNP performance beyond traditional pairwise linkage disequilibrium metrics?

Moving beyond pairwise LD metrics allows for more realistic assessment of tag SNP performance in actual imputation scenarios. Instead of relying solely on pairwise r² values, evaluate tag SNPs via:

- Empirical imputation accuracy: Use leave-one-out internal validation with standard imputation methods to measure mean imputed r² at untyped sites [29].

- Haplotype diversity accounting: Consider multi-marker haplotypes that better reflect the information used by modern imputation algorithms [29].

- Cross-population utility: Assess how well tag SNPs maintain information across multiple populations, particularly for diverse cohorts [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Tag SNP Selection Using LD Grouping Algorithm

Purpose: To select a minimal set of tag SNPs that efficiently captures genetic variation in a defined genomic region while limiting information loss.

Materials:

- Genotype data (VCF or PLINK format)

- High-performance computing resources

- Software: PLINK, TagIT, or custom scripts implementing LD grouping

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and QC

- Filter samples: Remove cryptic relatives and duplicates

- Filter variants: Apply MAF threshold (typically >5%), Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p > 1×10⁻⁶), and call rate (>95%) [34] [3]

- Stratify by ancestry: Perform PCA to confirm population assignments; analyze populations separately if structure exists [29]

LD Calculation

- Compute pairwise LD: Calculate r² between all SNP pairs within specified genomic windows (typically 200-1000 kb) using PLINK or specialized tools [34]

- Generate LD matrix: Create symmetric matrix of r² values for all variant pairs

LD Group Formation

- For threshold s = 0.0 to 1.0 (in increments of 0.1), group SNPs with r² ≥ s [34]

- For each LD group, infer haplotype classes using haplotype inference software (e.g., SNPHAP) [34]

- Divide SNPs into complete LD subgroups: SNPs in complete LD with respect to common haplotype classes (frequency ≥5%) belong to the same subgroup [34]

Tag SNP Selection

Validation:

- Perform internal cross-validation: Mask known genotypes and impute using selected tag SNPs

- Calculate concordance rate between imputed and true genotypes

- Aim for ≥95% allele concordance for common variants [34]

Protocol 2: Evaluating Imputation Accuracy Across Reference Panels

Purpose: To assess genotype imputation accuracy in diverse populations using different HapMap reference panel combinations.

Materials:

- Study population genotypes (e.g., Human Genome Diversity Project samples)

- Reference panels: HapMap CEU, YRI, CHB+JPT, or 1000 Genomes phased haplotypes

- Software: MACH, IMPUTE2, or Minimac

- Computing cluster for parallel processing

Procedure:

- Data Preparation

Reference Panel Configuration

Imputation Experiment

Accuracy Assessment

Interpretation:

- European populations typically show highest accuracy with CEU panel [30]

- African populations benefit most from YRI-containing panels [30]

- Most populations achieve optimal accuracy with mixed reference panels [30]

- Report optimal panel mixtures for each population group [30]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Tag SNP Selection and Imputation

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 Genomes Phase 3 | Reference Panel | Provides haplotype data from 26 global populations | Imputation reference; tag SNP selection |

| HapMap Project | Reference Panel | LD patterns in multiple populations (CEU, YRI, CHB+JPT) | Cross-population imputation portability |

| PLINK | Software Tool | Genome-wide association analysis; basic LD calculations | QC; initial SNP filtering; pairwise LD |

| TagIT | Software Algorithm | Tag SNP selection using empirical imputation accuracy | Population-aware array design |

| MACH/Minimac | Software Tool | Markov Chain-based genotype imputation | Imputation accuracy assessment |

| SNPrune | Software Algorithm | Efficient LD pruning for large datasets | Preprocessing for genomic prediction |

| IMPUTE2 | Software Tool | Hidden Markov model for imputation | Gold standard imputation method |

| SHAPEIT2 | Software Tool | Haplotype estimation and phasing | Pre-imputation data preparation |

| GenoBaits Platforms | Commercial Solution | Flexible SNP panels for target sequencing | Cost-effective breed-specific genotyping |

Core Concepts: Fine-Mapping and Credible Sets

What is the primary goal of statistical fine-mapping in genetic association studies?

Statistical fine-mapping aims to identify the specific causal variant(s) within a locus associated with a disease or trait, given the initial evidence of association found in a Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS). Its goal is to prioritize from the many correlated trait-associated SNPs in a genetic region those that are most likely to have a direct biological effect [37] [38].

What is a Credible Set and how is it constructed?

A credible set is a minimum set of variants that contains all causal SNPs with a specified probability (e.g., 95%) [37]. Under the assumption of a single causal variant per locus, a credible set is constructed by:

- Ranking all variants in the locus based on their Posterior Inclusion Probabilities (PIPs).

- Summing the PIPs in descending order.

- Including variants until this cumulative sum meets or exceeds the target probability threshold (α, often 95%) [37] [39].

What is the Posterior Inclusion Probability (PIP)?

The Posterior Inclusion Probability (PIP) for a variant indicates the statistical evidence for that SNP having a non-zero effect, meaning it is causal. Formally, it is calculated by summing the posterior probabilities of all models that include the variant as causal [37]. It is a core output of Bayesian fine-mapping methods.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Computational Challenges

Why does my credible set contain an unexpectedly large number of variants?

Large credible sets are often a power issue. The primary causes and solutions are:

- Low Power to Detect the Causal Variant: If the causal variant has a small effect size or a low minor allele frequency, the association signal may be weak. The fine-mapping method cannot confidently distinguish the true causal variant from its correlates in high LD, resulting in a large set of potential candidates [39].

- Solution: Increase sample size to boost power [38].

- High Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) in the Region: In regions with very high LD and low recombination, many SNPs are highly correlated. The data cannot easily determine which one is causal, so all highly correlated SNPs are included in the credible set [3] [38].

- Multiple Causal Variants in the Locus: The single causal variant assumption is violated. If multiple causal variants exist in high LD, it creates a complex association pattern that is difficult to resolve, inflating the credible set size [40].

The lead SNP from my GWAS is not in the credible set. Is this an error?

Not necessarily. This is a known and common occurrence in fine-mapping. Due to the complex correlation structure (LD) between variants, the SNP with the smallest p-value in a GWAS (the lead SNP) is not always the causal variant [38] [39]. The fine-mapping analysis incorporates the LD structure and may determine that another SNP in high LD with the lead SNP has a higher posterior probability of being causal.

Are the coverage probabilities for my credible sets (e.g., "95%") accurate?

Simulation studies have shown that the reported coverage probability for credible sets (e.g., 95%) can be over-conservative in many fine-mapping situations. This occurs because fine-mapping is typically performed only on loci that have passed a genome-wide significance threshold, meaning the data is not a random sample but is conditioned on having a strong signal. This selection bias can inflate the apparent coverage [39].

- Solution: Consider using methods that provide an "adjusted coverage estimate" which re-estimates the credible set's coverage using simulations based on the observed LD structure. This can sometimes allow for the creation of a smaller "adjusted credible set" that still meets the target coverage [39].

Should I use phased haplotypes or unphased genotypes for fine-mapping?

Using true haplotypes provides only a minor gain in fine-mapping efficiency compared to using unphased genotypes, provided an appropriate statistical method that accounts for phase uncertainty is used. A significant loss of efficiency and overconfidence in estimates can occur if you use a two-stage approach where haplotypes are first statistically inferred and then analyzed as if they were true [41].

- Solution: Use fine-mapping software that can directly analyze unphased genotypes and models phase uncertainty within its algorithm (e.g., COLDMAP) [41].

How can I improve fine-mapping resolution for traits with highly polygenic architectures?

Standard single-marker regression (SMR) has poor mapping resolution that worsens with larger sample sizes because it detects all SNPs in LD with the causal variant. Bayesian Variable Selection (BVS) models, which fit multiple SNPs simultaneously, offer superior resolution [40].

- Solution: For biobank-scale data, apply multi-locus BVS methods (e.g., BayesC, SUSIE, FINEMAP) that are computationally optimized for large datasets. These methods can model all SNPs in a locus concurrently, directly accounting for LD and providing better localization of causal signals [40].

Methodological Guide: Key Fine-Mapping Protocols

This protocol outlines the steps for a standard fine-mapping analysis using tools like SUSIE or PAINTOR, which require summary statistics and an LD reference panel [37] [38].

1. Define Loci for Fine-Mapping:

- Identify independent, genome-wide significant loci from your GWAS.

- For each locus, define a genomic window (e.g., ±50-100 kb around the lead SNP) to capture the LD structure [38].

- Extract the summary statistics (e.g., Z-scores, p-values, effect alleles) for all SNPs within each window.

2. Calculate the Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) Matrix:

- Using a reference panel with individual-level genotype data (e.g., 1000 Genomes) that matches the ancestry of your GWAS cohort, calculate the pairwise correlation matrix (r or r²) for all SNPs within each defined locus.

- Software: PLINK is commonly used for this task [37] [38].

3. Execute Fine-Mapping Analysis:

- Input the summary statistics and LD matrix into your chosen fine-mapping tool.

- Software Options:

4. Interpret the Output:

- The primary output is the Posterior Inclusion Probability (PIP) for each SNP.

- Use the PIPs to construct credible sets for each causal signal in the locus.

Workflow: Constructing a Credible Set

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for creating a credible set from fine-mapping results.

Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table: Essential Resources for Fine-Mapping Analysis

| Resource Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLINK [37] [38] | Software Tool | Calculate LD matrices from reference genotype data. | Industry standard; fast and efficient for processing large datasets. |

| SUSIE / SUSIE-RSS [37] [40] | Fine-Mapping Method | Identify multiple causal variants per locus using summary statistics. | Less sensitive to prior effect size misspecification than other methods. |

| FINEMAP [37] [40] | Fine-Mapping Method | Bayesian approach for fine-mapping with summary statistics. | Known for high computational efficiency and accuracy. |

| PAINTOR [38] | Fine-Mapping Method | Bayesian framework that incorporates functional annotations. | Improves prioritization by using functional genomic data as priors. |

| 1000 Genomes Project [38] | Data Resource | Publicly available reference panel for LD estimation. | Ensure the ancestry of the reference panel matches your study cohort. |

| Functional Annotations [38] | Data Resource | Genomic annotations (e.g., coding, promoter, DHS sites). | Informing priors with annotations like those from ENCODE can boost power. |

Data Interpretation & Reporting Standards

How should I report fine-mapping results in a manuscript?

When reporting fine-mapping results, ensure you include the following key details for transparency and reproducibility [3] [39]:

- Fine-mapping Method Used: Specify the software and version (e.g., SUSIE v1.0.7).

- LD Reference Panel: State the source of the LD matrix (e.g., 1000 Genomes Phase 3, EUR population).

- Credible Set Threshold: Report the target coverage for credible sets (e.g., 95%).

- PIP and Credible Set Contents: For each locus, report the top variants, their PIPs, and the composition of the credible set(s).

- Visualization: Use LocusZoom-style plots to display association p-values alongside LD information (r²) from the lead SNP for intuitive interpretation [3].

What is the difference between clumping and fine-mapping for defining associated loci?

These are distinct procedures with different goals [3]:

- Clumping: A post-GWAS procedure that groups association hits by LD around index SNPs. Its purpose is to provide a non-redundant summary of independent GWAS signals without double-counting correlated hits. It does not provide probabilistic statements about causality.

- Fine-Mapping: A detailed, within-locus analysis that uses LD and statistical models to quantify the probability that each variant is causal, resulting in a ranked list of candidates (PIPs) and credible sets.

Constructing and Applying Ancestry-Aware Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS)

Troubleshooting Guide: Common PRS Analysis Issues