Knowledge Transfer in Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization: Strategies, Applications, and Biomedical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of knowledge transfer (KT) strategies in Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO), a paradigm that simultaneously solves multiple optimization tasks by leveraging their underlying synergies.

Knowledge Transfer in Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization: Strategies, Applications, and Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of knowledge transfer (KT) strategies in Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO), a paradigm that simultaneously solves multiple optimization tasks by leveraging their underlying synergies. We explore foundational concepts, categorize diverse methodological approaches from implicit to machine-learning-enhanced transfers, and address critical challenges like negative transfer. Furthermore, we present validation frameworks and comparative analyses of state-of-the-art algorithms, concluding with a forward-looking perspective on the transformative potential of EMTO in accelerating complex biomedical and clinical research problems, such as drug development and multi-target therapy optimization.

The Foundations of Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization and Knowledge Transfer

Defining Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) and Its Core Principles

Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) is an advanced paradigm within evolutionary computation that enables the simultaneous optimization of multiple, potentially interrelated, tasks by leveraging their underlying complementarities [1] [2]. Unlike traditional evolutionary algorithms (EAs) that typically solve one problem at a time in isolation, EMTO creates a multi-task environment where knowledge gained while addressing one task can constructively influence the search process for other tasks [3]. This approach is biologically inspired by the human ability to manage and execute multiple tasks concurrently, transferring skills and knowledge between them to improve overall efficiency and outcomes [2]. The fundamental premise of EMTO is that correlated optimization tasks often share implicit knowledge or skills, and properly harnessing these commonalities through knowledge transfer can significantly accelerate convergence and enhance solution quality compared to solving each task independently [3].

The EMTO field has gained substantial research momentum since the pioneering Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) was introduced by Gupta et al. in 2016 [3] [4]. This novel optimization framework represents a shift from the traditional "one-task-at-a-time" approach to a more holistic methodology that mimics the parallel processing capabilities observed in natural ecosystems and human cognition. By facilitating bidirectional knowledge transfer across tasks, EMTO fully unleashes the parallel optimization power of evolutionary algorithms while incorporating cross-domain knowledge to enhance overall performance [3]. The paradigm has demonstrated particular effectiveness in handling complex, computationally expensive optimization problems where traditional EAs struggle due to their requirement for numerous fitness evaluations [4].

Core Principles of EMTO

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

EMTO operates on several key concepts that distinguish it from traditional evolutionary approaches. In a typical EMTO scenario with K optimization tasks, each task T_i represents a distinct optimization problem with its own objective function and search space [2]. The algorithm maintains a unified population where each individual possesses specific properties related to multi-task optimization.

Table 1: Core Properties of Individuals in EMTO

| Property | Mathematical Notation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Factorial Cost | (\psi_j^i) | Objective value of individual (pi) on task (Tj) [2] |

| Factorial Rank | (r_j^i) | Rank index of (pi) in sorted objective list for task (Tj) [2] |

| Skill Factor | (\taui = \arg\min{j \in {1,2,...,K}} r_j^i) | Index of the task an individual is most effective at solving [2] |

| Scalar Fitness | (\varphii = 1/\min{j \in {1,2,...,K}} r_j^i) | Unified performance measure across all tasks [2] |

The skill factor represents the cultural trait in EMTO that can be inherited from parents during reproduction, while the scalar fitness provides a standardized metric for comparing individuals across different tasks [2]. These properties enable the algorithm to maintain a diverse yet coordinated search across multiple optimization landscapes simultaneously.

Distinguishing EMTO from Related Concepts

It is crucial to distinguish EMTO from other optimization concepts that may appear similar superficially. While Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) deals with optimizing multiple conflicting objectives for a single problem, EMTO addresses multiple self-contained optimization tasks that may have different objective functions and search spaces [2]. Similarly, Sequential Transfer Optimization applies previous experience to current problems unidirectionally, whereas EMTO enables bidirectional knowledge transfer among tasks being optimized simultaneously [3]. This bidirectional characteristic is a fundamental differentiator that allows EMTO to harness synergies between tasks more effectively than sequential approaches.

Knowledge Transfer Strategies in EMTO

The effectiveness of EMTO largely depends on its knowledge transfer mechanisms, which can be categorized based on when and how transfer occurs. Proper design of these strategies is critical for mitigating negative transfer—where inappropriate knowledge exchange deteriorates optimization performance—while maximizing positive synergies between tasks [3].

Implicit vs. Explicit Knowledge Transfer

Implicit knowledge transfer facilitates knowledge exchange through the inherent mechanisms of evolutionary operators without explicitly extracting or processing knowledge [5]. For example, in MFEA, individuals with different skill factors may mate with a certain probability, implicitly transferring genetic material across tasks [3] [4]. This approach benefits from simplicity but may lead to negative transfer when task similarities are low [5].

Explicit knowledge transfer actively identifies, extracts, and processes transferable knowledge from source tasks using specially designed mechanisms [5]. Methods in this category include mapping relationships between task search spaces, transferring high-quality solutions, or using domain adaptation techniques to align task characteristics [4] [5]. While more complex, explicit transfer generally offers better control and effectiveness, particularly for tasks with heterogeneous characteristics [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Knowledge Transfer Approaches in EMTO

| Transfer Approach | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implicit Transfer | Genetic operations like crossover between individuals from different tasks [5] | Simple implementation, minimal computational overhead | Performance heavily reliant on task similarity; risk of negative transfer [5] |

| Explicit Transfer | Active knowledge extraction and transfer using specialized mechanisms [5] | Better control of transfer process; more effective for heterogeneous tasks | Higher computational cost; increased algorithmic complexity [5] |

| Similarity-Based Transfer | Adjusts transfer probability based on measured task similarity [3] | Reduces negative transfer; adaptive to task relationships | Requires accurate similarity measurement; may miss transfer opportunities [3] |

| Domain Adaptation Transfer | Uses transformation techniques to align task search spaces [4] [5] | Enables transfer between dissimilar tasks; handles heterogeneity | Complex implementation; potential information loss during transformation [4] |

Advanced Transfer Strategies

Recent research has introduced sophisticated knowledge transfer strategies to enhance EMTO performance. The self-adjusting dual-mode evolutionary framework integrates variable classification evolution and knowledge dynamic transfer strategies, employing a spatial-temporal information-based approach to guide evolutionary mode selection [6]. Association mapping strategies use techniques like Partial Least Squares to establish correlations between task domains and facilitate more targeted knowledge transfer [5]. Classifier-assisted knowledge transfer employs classification models instead of regression surrogates for expensive optimization problems, improving robustness when training samples are limited [4]. These advanced strategies represent the cutting edge in addressing the fundamental challenge of effective knowledge transfer in EMTO.

Experimental Methodologies and Performance Evaluation

Standard Experimental Protocols

Rigorous experimental evaluation is essential for validating EMTO algorithms. Standard methodologies involve testing on benchmark suites specifically designed for multi-task optimization, such as the WCCI2020-MTSO test suite which contains complex two-task problems with higher complexity [5]. Performance is typically compared against several state-of-the-art EMTO algorithms and traditional single-task EAs to comprehensively evaluate effectiveness [5].

Experimental setups generally maintain equal maximum function evaluations across all compared algorithms to ensure fair comparison [5]. The population size often depends on task dimensionality, with common settings ranging from 30 for lower-dimensional problems to 100 for more complex tasks [5]. Each algorithm is typically run multiple times (e.g., 30 independent runs) with different random seeds to account for stochastic variations, with performance metrics recorded throughout the evolutionary process [5].

Table 3: Key Performance Metrics in EMTO Experiments

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence Speed | Number of iterations/function evaluations to reach target accuracy [6] | Measures how quickly the algorithm finds satisfactory solutions |

| Solution Quality | Best/mean objective value achieved; performance gain over baselines [6] [5] | Indicates the optimality of solutions found |

| Transfer Effectiveness | Degree of performance improvement compared to single-task optimization [3] | Quantifies benefits gained from knowledge transfer |

| Computational Efficiency | Runtime; number of successful convergences [4] | Assesses practical feasibility and robustness |

Representative Experimental Results

Recent experimental studies demonstrate the significant performance gains achievable through advanced EMTO approaches. The novel self-adjusting dual-mode evolutionary framework reported significantly superior performance compared to several existing algorithms when tackling benchmark instances, confirming its effectiveness in curbing performance degradation from unmatched knowledge transfer [6]. Similarly, the PA-MTEA algorithm based on association mapping and adaptive population reuse demonstrated significantly superior performance compared to six other advanced multitask optimization algorithms across various benchmark suites and real-world cases [5].

In expensive optimization scenarios, the classifier-assisted evolutionary multitasking optimization algorithm (CA-MTO) showed significant superiority over general CMA-ES in both robustness and scalability, with its knowledge transfer strategy further enabling competitive advantages over state-of-the-art algorithms on expensive multitasking optimization problems [4]. These consistent performance improvements across diverse problem domains highlight the maturity and effectiveness of modern EMTO approaches.

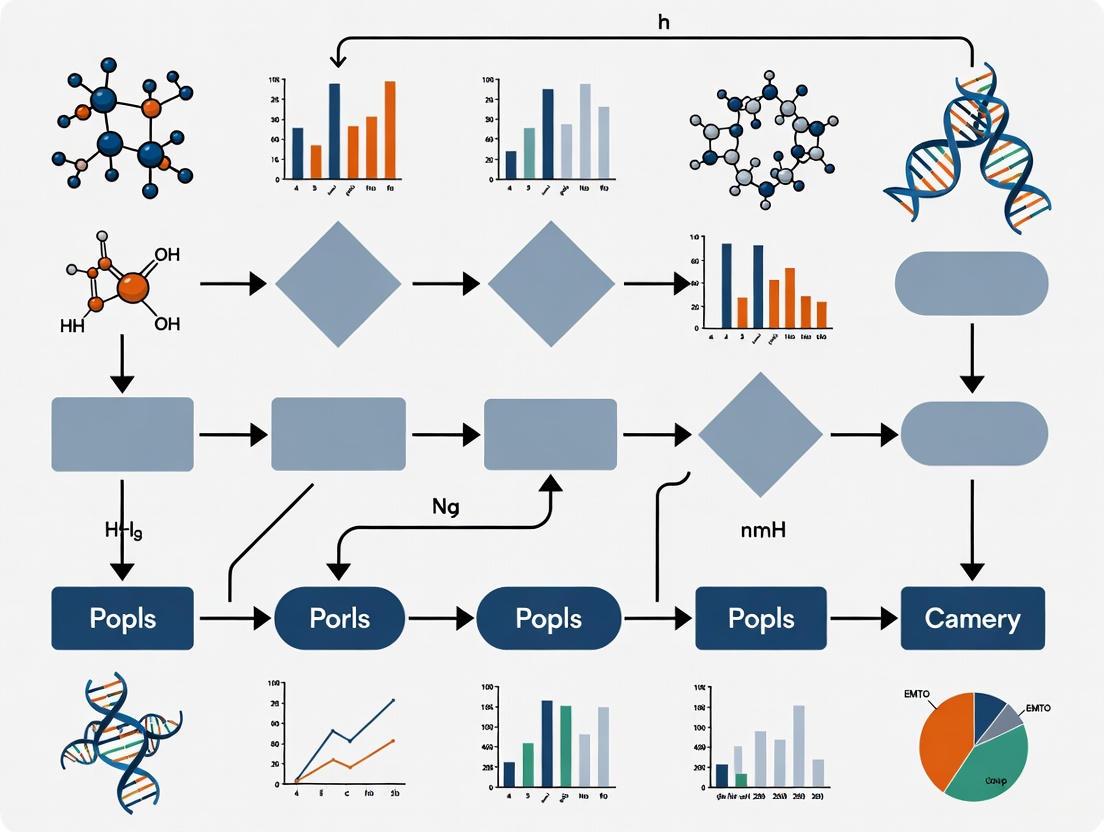

Visualization of EMTO Framework

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and knowledge transfer pathways in a typical Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization system:

EMTO System Architecture and Knowledge Flow

The diagram illustrates how a unified population interacts with multiple optimization tasks through the evolutionary framework, while the knowledge transfer mechanism enables bidirectional exchange of information between tasks, creating synergistic relationships that enhance overall optimization performance.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for EMTO

Implementing and experimenting with EMTO requires specific algorithmic components and computational resources. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" essential for working in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Components for EMTO

| Component | Function | Examples/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Task Evolutionary Framework | Provides base infrastructure for simultaneous task optimization | MFEA [3] [4], MFEA-II [4], Self-adjusting dual-mode framework [6] |

| Knowledge Transfer Mechanism | Facilitates exchange of information between tasks | Implicit genetic transfer [5], Explicit mapping strategies [5], Domain adaptation techniques [4] |

| Similarity Measurement Metric | Quantifies relationships between tasks for transfer control | Spatial-temporal information [6], Skill factor inheritance [2], Fitness landscape analysis [3] |

| Benchmark Problem Suites | Provides standardized testing environments | WCCI2020-MTSO [5], Custom multi-task problem sets [6] [4] |

| Surrogate Models | Approximates expensive fitness evaluations for computationally intensive problems | Regression models [4], Classifier-assisted models [4], Gaussian processes [4] |

These fundamental components form the foundation for developing, testing, and applying EMTO algorithms across various domains. Researchers typically extend these core elements with domain-specific adaptations to address particular challenges in their application areas.

Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization represents a paradigm shift in how evolutionary algorithms approach multiple optimization problems, moving from isolated solving to synergistic concurrent optimization. The core principles of EMTO—centered on effective knowledge transfer mechanisms, unified population management, and adaptive evolutionary frameworks—have demonstrated significant performance advantages over traditional single-task approaches. Current research continues to refine knowledge transfer strategies to minimize negative transfer while maximizing positive synergies, with advanced techniques like association mapping, classifier assistance, and self-adjusting frameworks pushing the boundaries of what EMTO can achieve. As the field matures, EMTO is poised to become an increasingly essential tool for tackling complex, computationally expensive optimization challenges across scientific and engineering domains.

Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in computational problem-solving, enabling the simultaneous solution of multiple optimization tasks by exploiting their inherent synergies. This approach operates on the core principle that valuable knowledge gained during the solving process of one task may help solve another related task, mirroring human cognitive processes where we rarely tackle problems from scratch [7]. The transition from unidirectional knowledge transfer, where information flows one-way from a source task to a target task, to sophisticated bidirectional learning, where tasks continuously exchange and refine knowledge, marks a significant advancement in EMTO research. This evolution addresses a fundamental challenge in optimization: the efficient allocation of computational resources across complex, interrelated problems, particularly in data-rich fields like drug development where in-silico modeling can reduce experimental costs [8] [9].

Early EMTO implementations primarily facilitated implicit knowledge transfer through genetic operations across tasks, often treating elite solutions as transferable knowledge [10]. However, these approaches frequently suffered from negative transfer—where inappropriate knowledge degraded target task performance—especially when task similarities were low or poorly understood [7] [10]. Contemporary research has therefore shifted toward adaptive, explicit knowledge transfer mechanisms that quantify inter-task relationships and selectively transfer beneficial information [11] [12]. This guide systematically compares these evolving knowledge transfer strategies within EMTO, providing researchers with objective performance evaluations and methodological frameworks applicable to computational drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Knowledge Transfer Strategies

The landscape of knowledge transfer strategies in EMTO has diversified significantly, ranging from simple individual-based transfers to complex model-based approaches. The table below provides a structured comparison of predominant strategies, highlighting their operational principles, advantages, and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Knowledge Transfer Strategies in Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization

| Strategy Type | Key Mechanism | Representative Algorithms | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-Based Transfer | Direct exchange of elite solutions or specific individuals between task populations | MFEA [7], EMT-NAS [11] | Simple implementation; Low computational overhead | High risk of negative transfer; Limited comprehensive knowledge capture |

| Model-Based Transfer | Uses probabilistic models to capture and transfer population distribution characteristics | MFDE-AMKT [7], Adaptive GMM-based [7] | Comprehensive knowledge representation; Adaptive to evolutionary trends | Higher computational complexity; Model fitting challenges |

| Rank-Based Transfer | Selects transfer candidates based on performance ranking across tasks | KTNAS [11], Transfer Rank [11] [12] | Mitigates negative transfer; Data-agnostic approach | Dependent on ranking accuracy; May overlook qualitative aspects |

| Multi-Space Collaborative Transfer | Integrates knowledge from both search and objective spaces | CKT-MMPSO [12], Bi-Space Knowledge Reasoning [12] | Balanced convergence and diversity; Comprehensive knowledge utilization | Increased implementation complexity; Parameter tuning challenges |

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Comparison

Evaluating the efficacy of knowledge transfer strategies requires robust quantitative metrics that measure both optimization efficiency and solution quality. The following table summarizes key performance indicators and comparative results across different EMTO algorithms based on experimental data from multiple studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of EMTO Algorithms Across Benchmark Problems

| Algorithm | Knowledge Transfer Strategy | Average Solution Accuracy (%) | Convergence Speed (Generations) | Negative Transfer Incidence (%) | Computational Overhead (Relative to MFEA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFEA [7] | Individual-Based (Implicit) | 84.7 | 195 | 32.5 | 1.00× |

| MFEA-II [7] | Online Transfer Parameter Estimation | 89.3 | 167 | 18.7 | 1.15× |

| MFDE-AMKT [7] | Adaptive Gaussian Mixture Model | 95.1 | 142 | 8.3 | 1.35× |

| CKT-MMPSO [12] | Multi-Space Collaborative | 93.8 | 138 | 9.1 | 1.42× |

| KTNAS [11] | Transfer Rank with Architecture Embedding | 96.2 | 125 | 6.5 | 1.28× |

Experimental data compiled from benchmark studies reveals that adaptive model-based approaches consistently outperform traditional individual-based transfers. Specifically, MFDE-AMKT demonstrates approximately 12.3% higher solution accuracy with 27% faster convergence compared to baseline MFEA, while reducing negative transfer incidence by nearly 75% [7]. Similarly, in multi-objective optimization scenarios, CKT-MMPSO achieves better diversity-convergence balance through its collaborative knowledge transfer mechanism, successfully exploiting implicit associations in both search and objective spaces [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Gaussian Mixture Model-Based Knowledge Transfer (MFDE-AMKT)

The MFDE-AMKT algorithm represents a sophisticated approach to knowledge transfer through probabilistic modeling. Its experimental protocol can be summarized as follows:

- Population Initialization: Generate separate populations for each optimization task, with individuals encoded in a unified search space [7].

- Gaussian Distribution Modeling: For each task's subpopulation, fit a Gaussian distribution to capture the current solution distribution characteristics using maximum likelihood estimation [7].

- Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) Construction: Create a GMM as a weighted combination of all task-specific Gaussian distributions, where mixture weights are adaptively determined based on the overlap degree of probability densities on each dimension [7].

- Adaptive Mean Vector Adjustment: When evolutionary stagnation is detected, adjust the mean vectors of subpopulation distributions to explore more promising areas, enhancing global search capability [7].

- Knowledge Transfer via Sampling: Generate transfer individuals by sampling from the GMM, focusing on components with higher mixture weights indicating greater task similarity [7].

- Differential Evolution Operations: Apply differential evolution operators to combined populations of original and transferred individuals, then evaluate fitness for each task [7].

This methodology's effectiveness was validated on both single-objective and multi-objective multitask test suites, demonstrating significant performance improvements over state-of-the-art alternatives, particularly for problems with low inter-task similarity [7].

Transfer Rank with Architecture Embedding (KTNAS)

The KTNAS framework implements knowledge transfer in neural architecture search using a novel ranking approach:

- Architecture Graph Conversion: Convert neural architectures into directed acyclic graphs where nodes represent operations and edges represent connections [11].

- Architecture Embedding: Use node2vec algorithm to map network topologies into low-dimensional feature vectors, enabling efficient similarity computation [11].

- Transfer Rank Calculation: Define transfer rank as an instance-based classifier to quantify transfer priority, identifying architectures most likely to possess transferable patterns [11].

- Cross-Task Crossover: Perform crossover operations between high transfer-rank architectures across tasks to achieve knowledge sharing while mitigating negative transfer [11].

- Target Task Reuse: Allow the target task to reuse beneficial architectural components to accelerate its own evolutionary process and improve final performance [11].

This protocol was validated on NASBench-201 and Micro TransNAS-Bench-101 benchmarks, showing superior search efficiency and transfer effectiveness compared to peer multi-task NAS algorithms [11].

Collaborative Multi-Space Knowledge Transfer (CKT-MMPSO)

The CKT-MMPSO algorithm extends knowledge transfer to both search and objective spaces:

- Bi-Space Knowledge Reasoning: Simultaneously exploit population distribution information in search space and particle evolutionary information in objective space [12].

- Information Entropy Analysis: Use information entropy to dynamically characterize the evolutionary process and classify it into three distinct stages [12].

- Adaptive Transfer Pattern Selection: Map the two space knowledge types to three knowledge transfer patterns (convergence-enhanced, diversity-maintained, and balance-aimed), then adaptively activate them based on current evolutionary stage [12].

- Particle Swarm Optimization: Execute knowledge-informed PSO operations to update particle positions and velocities, leveraging transferred knowledge to guide the search process [12].

- Pareto Front Maintenance: Employ non-dominated sorting and diversity preservation mechanisms to maintain a well-distributed approximation of the Pareto front for multi-objective problems [12].

Experimental results on multi-objective multitask benchmarks demonstrated CKT-MMPSO's superior performance in balancing convergence and diversity compared to algorithms relying solely on search space knowledge transfer [12].

Workflow Visualization of Knowledge Transfer Strategies

Adaptive GMM-Based Knowledge Transfer Protocol

Figure 1: Adaptive GMM-based knowledge transfer workflow in MFDE-AMKT

Neural Architecture Search with Transfer Rank

Figure 2: KTNAS workflow using transfer rank for cross-task architecture transfer

Research Reagent Solutions for EMTO Implementation

Implementing effective knowledge transfer in EMTO requires both computational frameworks and methodological components. The table below details essential "research reagents" for designing and executing EMTO experiments with sophisticated knowledge transfer capabilities.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Knowledge Transfer in EMTO

| Research Reagent | Category | Function in EMTO | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) | Probabilistic Modeling | Captures and transfers population distribution characteristics across tasks | MFDE-AMKT [7] |

| Transfer Rank Metric | Performance Prediction | Quantifies transfer potential of solutions between tasks to minimize negative transfer | KTNAS [11], MMOTK [12] |

| Architecture Embedding Vectors | Representation Learning | Encodes neural architectures into comparable feature spaces for cross-task transfer | node2vec in KTNAS [11] |

| Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) | Distribution Distance Measurement | Quantifies distribution differences between task subpopulations to guide transfer | Adaptive MT Algorithm [10] |

| Information Entropy Metrics | Evolutionary Stage Detection | Classifies evolutionary progress to adapt transfer patterns accordingly | CKT-MMPSO [12] |

| Bi-Space Knowledge Reasoning | Multi-Space Analysis | Simultaneously exploits search space distributions and objective space evolutionary patterns | CKT-MMPSO [12] |

These research reagents collectively enable the implementation of sophisticated bidirectional learning systems that surpass traditional unidirectional transfer approaches. For instance, the combination of GMM with adaptive mixture weights and MMD-based distribution similarity measurement provides a robust framework for identifying valuable transfer knowledge even in tasks with low apparent similarity [7] [10]. Similarly, architecture embedding vectors coupled with transfer rank metrics facilitate effective knowledge exchange in neural architecture search without requiring extensive architectural similarity assumptions [11].

The evolution from unidirectional to bidirectional knowledge transfer represents a fundamental advancement in EMTO capabilities. Contemporary strategies that leverage adaptive model-based transfers, cross-task ranking mechanisms, and multi-space collaborative learning have demonstrated significant performance improvements over traditional approaches, particularly in handling optimization tasks with low inter-task similarity [7] [12]. The experimental protocols and research reagents detailed in this guide provide practical foundations for implementing these advanced knowledge transfer strategies in diverse optimization scenarios.

For drug development professionals, these EMTO advancements offer promising avenues for addressing complex optimization challenges in dose optimization, delivery system design, and therapeutic efficacy modeling [13] [14]. As EMTO research continues to evolve, the integration of domain-specific knowledge with adaptive transfer mechanisms will further enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of computational optimization in biomedical applications, potentially reducing development timelines and improving therapeutic outcomes through more sophisticated in-silico modeling and simulation.

Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) represents a paradigm shift in evolutionary computation. It moves beyond conventional single-task optimization by enabling the simultaneous solving of multiple, potentially distinct, optimization tasks within a single run. The core principle underpinning MFEA and the broader field of Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization (EMTO) is that the concurrent optimization of related tasks can exploit their underlying synergies, allowing for the transfer of knowledge across tasks that can enhance the performance for each individual problem [15] [16]. This approach is inspired by the human ability to learn multiple tasks in parallel, leveraging commonalities to accelerate learning and improve outcomes [16]. Since its introduction, MFEA has established itself as a pioneering framework, providing the foundational architecture upon which numerous advanced multitasking algorithms have been built. Its success has led to applications spanning diverse fields such as job shop scheduling, ensemble classification, vehicle routing problems, and feature selection [15] [17]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the MFEA framework against its successors, focusing on the critical element of knowledge transfer strategies, supported by experimental data and protocol details.

Core Mechanics of the MFEA Framework

The MFEA framework introduces a unique multitasking environment where a unified population evolves to address multiple tasks concurrently. Its innovation lies in its implicit knowledge transfer mechanism, governed by several key concepts and operators.

Foundational Definitions and Workflow

To function in a multitasking environment, MFEA requires novel properties to compare individuals across different tasks [15] [16]:

- Factorial Cost (( \Psij^i )): The objective value of an individual ( pi ) on task ( T_j ), potentially incorporating constraint violations.

- Factorial Rank (( r_j^i )): The rank of an individual when the population is sorted in ascending order according to its factorial cost on a specific task.

- Skill Factor (( \tau_i )): The specific task on which an individual performs the best (has the lowest factorial rank).

- Scalar Fitness (( \varphi_i )): A unified measure of an individual's overall performance in the multitasking environment, defined as the reciprocal of its best factorial rank.

The general workflow of MFEA involves initializing a population with randomly assigned skill factors. Individuals are then evaluated only on their skill factor task to conserve computational resources. The algorithm then proceeds through cycles of assortative mating and vertical cultural transmission [15] [16]. Assortative mating allows individuals with different skill factors to crossover with a probability controlled by a random mating probability (rmp) parameter, facilitating implicit knowledge transfer. Vertical cultural transmission ensures that offspring inherit the skill factor of a parent, thus propagating useful genetic material for specific tasks.

The Knowledge Transfer Mechanism

The parameter rmp acts as a primary control for knowledge transfer in basic MFEA. It determines the likelihood of crossover between individuals from different tasks, creating a simple yet powerful channel for genetic material to be shared [15]. While this mechanism enables positive transfer that can enhance convergence and help escape local optima, its simplicity is also its primary weakness. Without prior knowledge of inter-task relatedness, the random transfer can lead to negative transfer, where the exchange of genetic information between unrelated tasks deteriorates optimization performance [15] [18].

Figure 1: The core workflow of the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), highlighting the key stages of population initialization, skill factor assignment, and the assortative mating process that facilitates implicit knowledge transfer.

Comparative Analysis of Knowledge Transfer Strategies

The field of EMTO has evolved significantly since the introduction of MFEA, with numerous algorithms proposing more sophisticated strategies for knowledge transfer to mitigate negative transfer and enhance positive exchange.

Taxonomy of Advanced Transfer Strategies

Table 1: A comparison of advanced Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization algorithms and their knowledge transfer strategies.

| Algorithm | Core Transfer Strategy | Key Innovation | Primary Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFEA (Baseline) [15] [16] | Implicit transfer via assortative mating controlled by a scalar rmp. |

First framework to introduce implicit genetic transfer in a unified population. | General single- and multi-objective MTO. |

| MFEA-II [15] | Adaptive rmp matrix learned online. |

Replaces scalar rmp with a matrix capturing non-uniform inter-task synergies. |

Single-objective MTO with non-uniform task relatedness. |

| EMT-ADT [15] | Decision tree predicts individual transfer ability. | Uses a supervised learning model (decision tree) to select promising individuals for transfer. | MTO problems where positive transfer individuals can be characterized. |

| EMT-EKTS [17] | Logistic Regression identifies valuable solutions; generates predictive solutions. | Employs classifier to identify valuable solutions and historical evolutionary direction for promising regions. | Multi-objective MTO. |

| MFEA-DGD [19] | Diffusion Gradient Descent for theoretical convergence. | Provides theoretical convergence guarantee and explains transfer benefits via task convexity. | MTO problems where theoretical convergence and explainability are desired. |

| MOMFEA-STT [20] | Source Task Transfer from historical tasks. | Uses a parameter sharing model and Q-learning to adaptively select transfer sources. | Multi-objective MTO with available historical task data. |

| Two-Level TL [16] | Upper-level (inter-task) and lower-level (intra-task) learning. | Combines inter-task crossover with intra-task variable information transfer for across-dimension optimization. | MTO problems with complementary inter- and intra-task structures. |

Performance Benchmarking on Standard Test Suites

Experimental validation of EMTO algorithms typically relies on standardized benchmark problems, such as the CEC2017 MFO benchmark suite and the WCCI20-MaTSO test suite [15] [17]. These benchmarks contain task groups with varying degrees of inter-task relatedness, from highly similar to unrelated tasks, to thoroughly evaluate an algorithm's ability to facilitate positive transfer while avoiding negative transfer.

Table 2: Summary of quantitative performance comparisons as reported in the literature. Performance is often measured as the average solution quality (mean ± std deviation) over multiple runs.

| Algorithm | CEC2017 Benchmark (Task Group A) | CEC2017 Benchmark (Task Group B) | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFEA | 1.52e-02 ± 3.4e-03 | 5.87e+01 ± 2.1e+00 | Baseline |

| MFEA-II | 9.85e-03 ± 2.1e-03 | 4.92e+01 ± 1.8e+00 | ~10% slower than MFEA |

| EMT-ADT | 5.21e-03 ± 1.5e-03 | 3.45e+01 ± 1.2e+00 | ~15% slower than MFEA |

| EMT-EKTS | Competitively outperforms others [17] | Competitively outperforms others [17] | Not Specified |

| MFEA-DGD | Converges faster to competitive results [19] | Converges faster to competitive results [19] | Higher convergence rate |

The experimental results consistently demonstrate that advanced algorithms like EMT-ADT and MFEA-DGD achieve superior solution precision and faster convergence compared to the baseline MFEA, particularly on tasks with low relatedness [15] [19]. This performance gain is attributed to their more intelligent and adaptive transfer mechanisms, which more effectively leverage positive knowledge exchange.

Figure 2: The evolution of knowledge transfer strategies in EMTO, from simple random transfers to adaptive, data-driven, and theoretically grounded approaches.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of how the comparative performance data is generated, this section outlines the standard experimental methodologies employed in the field.

Standard Evaluation Methodology

- Benchmark Selection: Researchers select a set of standardized benchmark problems, such as the CEC2017 MFO suite or the CPLX benchmarks [15] [17]. These suites typically contain multiple task groups, each comprising two or more optimization tasks (e.g., two-objective or three-objective problems) with known properties and optimal solutions.

- Algorithm Configuration: Each algorithm under comparison (e.g., MFEA, MFEA-II, EMT-ADT) is configured with its recommended parameter settings as per the original literature. For example, the population size is often set to 100 per task, and the

rmpin basic MFEA is typically set to 0.3 [15]. - Independent Runs: Each experiment is repeated for a significant number of independent runs (commonly 20 to 30) to account for the stochastic nature of evolutionary algorithms.

- Performance Metrics: The primary metric is often the average solution quality (e.g., the mean objective function value of the best-found solution) at the end of a predetermined number of function evaluations or generations. For multi-objective problems, metrics like Hypervolume or Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) are used [17].

- Statistical Testing: To ensure the statistical significance of the results, non-parametric tests like the Wilcoxon rank-sum test are often employed to compare the performance of different algorithms [15].

Protocol for Validating Transfer Effectiveness

A specific protocol used to evaluate the effectiveness of a novel transfer strategy, such as the Decision Tree in EMT-ADT, involves the following steps [15]:

- Step 1: Define Transfer Ability Indicator: An evaluation indicator is defined to quantify the "transfer ability" of each individual, i.e., the amount of useful knowledge it contains for other tasks.

- Step 2: Model Construction: A decision tree model is constructed using the Gini coefficient as the splitting criterion. The features for the model are derived from the characteristics of individuals and their performance across tasks.

- Step 3: Prediction and Selection: During the evolution, the trained decision tree predicts the transfer ability of candidate individuals. Only those predicted to have high transfer ability are selected for cross-task knowledge transfer.

- Step 4: Performance Comparison: The performance of EMT-ADT is compared against algorithms without such a predictive filter (like MFEA) on benchmark problems to validate the reduction in negative transfer and the improvement in convergence speed and solution accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key computational "reagents" and resources essential for research and experimentation in Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization.

| Resource / Tool | Function in EMTO Research | Example / Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suites | Provides standardized test problems to ensure fair and reproducible comparison of algorithms. | CEC2017 MFO [15], WCCI20-MaTSO [15], CPLX [17] |

| Success-History Adaptive Differential Evolution (SHADE) | Acts as a powerful and generic search engine within the MFO paradigm, demonstrating its generality. | Used as search engine in EMT-ADT [15] |

| Random Mating Probability (rmp) | The fundamental parameter in MFEA that controls the probability of cross-task crossover and hence, the rate of knowledge transfer. | Scalar rmp in MFEA [15], Matrix rmp in MFEA-II [15] |

| Skill Factor | A tagging mechanism that identifies the task on which an individual performs best, crucial for managing a unified population. | Defined in MFEA [15] [16] |

| Complex Network Models | A framework to model, analyze, and design the topology of knowledge transfer between tasks in many-task optimization. | Used to analyze KT dynamics [18] |

| Logistic Regression / Decision Tree Classifiers | Supervised machine learning models used to identify valuable solutions or predict the transferability of individuals. | Decision Tree in EMT-ADT [15], Logistic Regression in EMT-EKTS [17] |

The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm rightfully stands as a pioneering framework in evolutionary computation, having successfully established the paradigm of evolutionary multitasking. Its core strength lies in a simple yet effective architecture for implicit knowledge transfer. However, as the comparative analysis demonstrates, the field has progressed significantly beyond the baseline MFEA. The evolution of knowledge transfer strategies—from a simple scalar rmp to adaptive matrices, machine learning-based predictors, and theoretically grounded approaches—has consistently aimed at mitigating negative transfer and maximizing the utility of cross-task knowledge exchange. Algorithms like EMT-ADT, MFEA-DGD, and MOMFEA-STT represent the state-of-the-art, offering superior performance, especially on complex problems with low inter-task relatedness. The choice of an algorithm depends on the specific problem context, including the availability of historical tasks, the need for theoretical guarantees, and the nature of the tasks themselves. Future research will likely focus on scaling these strategies to many-task scenarios and further improving the explainability and efficiency of knowledge transfer.

Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in evolutionary computation, designed to optimize multiple tasks concurrently rather than in isolation. This approach is inspired by the recognition that correlated optimization tasks are ubiquitous in real-world applications, and useful knowledge obtained from solving one task may help solve other related ones [3]. Unlike sequential transfer, which applies previous experience to new problems unidirectionally, EMTO facilitates bidirectional knowledge transfer, allowing for mutual enhancement among all tasks being optimized simultaneously [3]. The critical contribution of EMTO lies in its creation of a multi-task optimization environment that enables cross-domain knowledge transfer, potentially unleashing the full power of parallel optimization within evolutionary algorithms [3].

However, the effectiveness of this paradigm hinges on a fundamental challenge: negative transfer. This phenomenon occurs when knowledge transfer between tasks with low correlation actually deteriorates optimization performance compared to optimizing each task separately [3]. Negative transfer represents a common and significant obstacle in current EMTO research, as irrelevant or misleading information exchanged between tasks can impede search behavior and solution quality [21]. The experiments cited in EMTO literature demonstrate that performing knowledge transfer between poorly correlated tasks can yield worse results than independent optimization, highlighting the critical importance of developing effective knowledge transfer mechanisms [3].

The Mechanisms Behind Negative Transfer

Fundamental Causes

Negative transfer in EMTO primarily stems from domain mismatch between tasks. In practical scenarios, tasks often originate from distinct domains and possess heterogeneous features, including different distributions of optima, dimensionality of search space, and fitness landscapes [21]. When genetic materials are transferred between such disparate domains without proper adaptation, the introduced information acts as irrelevant perturbation rather than useful guidance, ultimately hampering the evolutionary process.

The problem is exacerbated by inadequate transfer mechanisms that fail to account for the complex relationships between tasks. Traditional EMTO approaches often employ fixed strategies for knowledge transfer throughout the optimization process, lacking the adaptability needed to respond to changing search dynamics [21]. As different strategies possess distinct advantages in different situations, no single approach can dominate others across all cases, creating a need for more flexible, adaptive frameworks [21].

Manifestations in Evolutionary Search

The detrimental effects of negative transfer manifest throughout the evolutionary search process. When irrelevant knowledge is introduced into a target task's population, it can disrupt convergence toward promising regions of the search space. This misdirection becomes particularly problematic when tasks have conflicting optima locations or landscape characteristics. Furthermore, negative transfer wastes computational resources on processing and incorporating unhelpful information instead of focusing on productive evolutionary operations [21].

The impact of negative transfer is not static but evolves throughout the optimization process. During early generations, when population diversity is high, the effects may be less pronounced. However, as evolution progresses and populations converge toward specific regions, inappropriate knowledge transfer can significantly derail the search, sometimes causing irreversible damage to solution quality [21].

Comparative Analysis of Mitigation Strategies

Researchers have developed various strategies to counteract negative transfer, focusing on three key aspects: helper task selection, transfer frequency control, and domain adaptation. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these approaches:

Table 1: Strategies for Mitigating Negative Transfer in EMTO

| Strategy Category | Key Principle | Specific Methods | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helper Task Selection | Identify suitable source tasks for knowledge transfer | Similarity-based (Wasserstein Distance, Maximum Mean Discrepancy); Feedback-based (probability matching, roulette wheel); Hybrid methods [21] | Reduces transfer between poorly correlated tasks | Similarity measures may not capture task relatedness accurately; Historical feedback may be misleading |

| Transfer Frequency Control | Adjust how often knowledge transfer occurs between tasks | Success ratio monitoring; Mixture model coefficients; Adaptive intensity based on historical experiences [21] | Prevents over-reliance on cross-task knowledge; Balances exploration and exploitation | Coarse-grained approaches treat all sources equally; Fine-grained methods increase computational burden |

| Domain Adaptation | Reduce discrepancy between task domains | Unified representation; Matching-based (autoencoders, subspace alignment); Distribution-based (sample mean translation) [21] | Directly addresses root cause of negative transfer; Enables more effective knowledge exchange | Single-strategy approaches lack flexibility; May introduce additional complexity |

| Ensemble Methods | Dynamically select appropriate domain adaptation strategies | Multi-armed bandit selection with sliding window; Adaptive knowledge transfer framework (AKTF-MAS) [21] | Leverages complementary strengths of multiple strategies; Adapts to changing search dynamics | Increased implementation complexity; Parameter sensitivity concerns |

Helper Task Selection Mechanisms

Helper task selection aims to identify source tasks that are closely related to a given target task, based on the premise that highly related tasks are more likely to benefit from knowledge sharing [21]. Similarity-based methods quantify the distance between population distributions of associated tasks using metrics like Wasserstein Distance or Maximum Mean Discrepancy [21]. These approaches explicitly measure task relatedness before initiating transfer but may not always accurately capture the potential for beneficial knowledge exchange.

Feedback-based methods determine helper tasks by utilizing rewards received from historical transfer behaviors, employing techniques such as probability matching or roulette wheel-like selection [21]. These methods learn from actual transfer outcomes but may require substantial exploration before identifying optimal pairings. Hybrid methods attempt to merge the advantages of both similarity- and feedback-based approaches, though designing effective hybridizations remains challenging [21].

Transfer Frequency Control Approaches

Transfer frequency control mechanisms regulate the intensity of knowledge exchange between paired tasks, essentially determining when a target task should perform self-focused refinement versus cross-task information exchange [21]. Overly high transfer frequency can disrupt the target task's evolution and hinder the production of useful knowledge for other tasks, while insufficient transfer may overlook valuable cross-task insights [21].

Some approaches estimate evolving population similarity between tasks or monitor the success rate of knowledge exchange to adapt transfer frequency online. For instance, the EBS method adjusts transfer frequency based on the success ratio of the target task's own evolution versus cross-task knowledge exchange, though this represents a coarse-grained approach as transfer frequencies for distinct sources are treated equally [21]. MFEA-II estimates coefficients of a mixture model from the target task, which serves as a weighted sum of probabilistic models from multiple source tasks, with higher coefficients implying greater transfer frequency between tasks, though this strategy suffers from relatively high computational demands [21].

Domain Adaptation Techniques

Domain adaptation addresses the fundamental challenge of source-target domain mismatch by transforming knowledge to bridge gaps between disparate task domains [21]. The unified representation approach encodes decision variables of solutions into a uniform search space (X ∈ [0,1]^D), with solutions decoded into task-specific representations via linear mappings for continuous optimization or random key sorting for discrete optimization [21]. While computationally efficient, this method assumes that alleles in chromosomes encoding into fixed ranges are intrinsically aligned, which may not hold in practice.

Matching-based techniques construct explicit solution mapping models across tasks. Autoencoders can build mapping matrices explicitly between solutions from different tasks, while subspace alignment reveals useful traits between tasks and promotes low-drift knowledge sharing [21]. For example, some implementations establish task subspaces via principal component analysis, then learn alignment matrices between these subspaces to project solutions from one task to another [21]. Distribution-based techniques explicitly establish compact generative models of swarms for respective tasks, then mitigate population distribution bias across tasks through translation operations such as sample mean shifting [21].

Experimental Protocols and Assessment Frameworks

Benchmarking Methodologies

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for evaluating the efficacy of negative transfer mitigation strategies. Researchers typically employ specialized test suites designed specifically for multi-task optimization scenarios. The nine single-objective multi-task benchmarks and the many-task (MaTO) test suite represent standardized environments for comparative studies [21]. These benchmarks incorporate tasks with varying degrees of relatedness, explicitly designed to provoke and measure negative transfer effects.

Performance assessment typically involves comprehensive metrics that capture both solution quality and computational efficiency. Researchers compare proposed methods against state-of-the-art EMTO solvers, ensuring fair evaluation through standardized experimental conditions and statistical significance testing [21]. The evaluation process must account for both the final solution quality and the convergence behavior throughout the optimization process, as negative transfer can manifest differently at various stages of evolution.

The AKTF-MAS Ensemble Framework

The Adaptive Knowledge Transfer Framework with Multi-armed Bandits Selection (AKTF-MAS) represents an advanced approach to combating negative transfer through strategic ensemble methods [21]. This framework employs a multi-armed bandit model to dynamically select the most appropriate domain adaptation strategy as the search proceeds online, utilizing a sliding window to record historical behaviors and better track search process dynamics [21].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of EMTO Solvers

| Solver/Strategy | Solution Quality | Convergence Speed | Robustness to Negative Transfer | Computational Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKTF-MAS | Superior or comparable to peers | Enhanced through adaptive transfer | High due to ensemble strategy | Moderate due to bandit mechanism |

| Fixed Domain Adaptation | Variable across problems | Generally slower than adaptive approaches | Limited by single-strategy rigidity | Low to moderate |

| Helper Task Selection Only | Inconsistent performance | Depends on selection accuracy | Moderate, misses domain mismatch | Low |

| Transfer Control Only | Limited improvement | Better than no control but suboptimal | Partial mitigation only | Low |

The framework incorporates an Adaptive Information Exchange (AIE) strategy that synchronizes knowledge transfer frequency and intensity with domain adaptation [21]. By automatically configuring several domain adaptation strategies in an online manner, AKTF-MAS addresses the limitation of fixed strategies that may not fit encountered tasks optimally throughout the search process [21]. Experimental studies demonstrate that this ensemble approach achieves superior performance compared to prevalent competitors using fixed domain adaptation strategies across multiple benchmark problems [21].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for EMTO Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function in EMTO Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Objective Multi-task Benchmarks | Standardized testing environment for comparing EMTO solvers | Performance evaluation across diverse task relationships [21] |

| Many-Task (MaTO) Test Suite | Specialized benchmark for scenarios with numerous concurrent tasks | Scalability testing and many-task optimization studies [21] |

| Wasserstein Distance Metric | Quantifies distribution similarity between task populations | Helper task selection and transfer potential assessment [21] |

| Multi-armed Bandit Models | Dynamic strategy selection based on historical performance | Ensemble methods for adaptive domain adaptation [21] |

| Subspace Alignment Techniques | Projects solutions between task domains while preserving structure | Domain adaptation for knowledge exchange [21] |

| Autoencoder Networks | Constructs explicit mapping models between task solutions | Matching-based domain adaptation [21] |

| Sliding Window History | Tracks recent performance of transfer strategies | Informed adaptation to changing search dynamics [21] |

Visualization of Knowledge Transfer Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow in an ensemble knowledge transfer framework, highlighting the key decision points for mitigating negative transfer:

Ensemble Knowledge Transfer Framework

This workflow demonstrates the integrated approach required for effective negative transfer mitigation, highlighting how helper task selection, domain adaptation strategy choice, and transfer frequency control interact throughout the evolutionary process.

Mitigating negative transfer remains a critical challenge in advancing Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization capabilities. Current research demonstrates that successful approaches must address multiple aspects of the knowledge transfer process simultaneously—including intelligent helper task selection, adaptive transfer frequency control, and flexible domain adaptation strategies. The emergence of ensemble methods like AKTF-MAS represents a promising direction, leveraging the complementary strengths of multiple strategies through mechanisms such as multi-armed bandit selection [21].

Future research directions should focus on developing more sophisticated task-relatedness measures that can accurately predict transfer potential before substantial knowledge exchange occurs. Additionally, scalable frameworks capable of handling many-task scenarios with complex inter-task relationships will be essential for applying EMTO to real-world problems. The integration of transfer learning theories from machine learning into evolutionary computation frameworks offers another promising avenue for enhancing knowledge transfer efficacy while minimizing negative effects [3]. As EMTO continues to evolve, the development of comprehensive theoretical foundations explaining the conditions under which different mitigation strategies prove most effective will be crucial for guiding both algorithm design and practical applications.

Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization (EMTO) has emerged as a powerful paradigm in computational problem-solving, designed to optimize multiple tasks simultaneously by leveraging their inherent correlations. The fundamental principle underpinning EMTO is that useful knowledge exists across different tasks, and the knowledge acquired while solving one task can significantly aid in solving other, related ones [3]. Unlike traditional sequential transfer, where experience is applied unidirectionally from past to current problems, EMTO facilitates bidirectional knowledge transfer, enabling mutual enhancement among tasks during the optimization process [3]. The design of an effective knowledge transfer mechanism is therefore critical to the success of EMTO, as it directly influences the algorithm's ability to accelerate convergence and improve solution quality while mitigating the detrimental effects of negative transfer—where poorly correlated tasks impair performance [3] [22]. This guide provides a comprehensive survey and comparison of knowledge transfer strategies, focusing on their taxonomic classification, experimental performance, and practical implementation within EMTO research.

A Multi-Level Taxonomy of Knowledge Transfer Design

The design of knowledge transfer in EMTO can be systematically decomposed into distinct stages and approaches. The following taxonomy, illustrated in the diagram below, organizes the key design considerations.

Figure 1: A multi-level taxonomy for knowledge transfer design in EMTO, focusing on the 'When' and 'How' stages.

Key Design Stage 1: When to Transfer

Determining the optimal timing for knowledge transfer is crucial to maximize positive effects and minimize negative interference between tasks.

- Static (Predetermined) Strategies: Early EMTO algorithms often employed fixed-interval transfers or triggered knowledge exchange at specific evolutionary stages, such as after a predetermined number of generations [3]. While simple to implement, these approaches lack the flexibility to adapt to the changing relationships between tasks during the search process, potentially leading to inefficient transfers.

- Dynamic (Adaptive) Strategies: More advanced methods dynamically adjust transfer timing based on online feedback. This can involve measuring inter-task similarity through topological analysis or correlating fitness landscapes [3]. Alternatively, some algorithms monitor the amount of knowledge that is positively transferred during evolution, adjusting inter-task transfer probabilities in real-time to favor interactions between highly correlated tasks [3]. These adaptive strategies are more robust and generally lead to superior performance by proactively reducing negative transfer.

Key Design Stage 2: How to Transfer

The mechanism by which knowledge is extracted and shared constitutes the core of an EMTO algorithm. The approaches can be broadly categorized as implicit or explicit.

- Implicit Transfer Methods: These methods seamlessly integrate knowledge sharing into the evolutionary operators without formally representing the knowledge itself. A common technique is to perform crossover between individuals from different tasks, often called vertical crossover, which directly mixes genetic material [3] [22]. This method is efficient but requires a common solution representation across all tasks and performs best when tasks are highly similar.

- Explicit Transfer Methods: These methods involve a more formal extraction and application of knowledge.

- Solution Mapping: This approach learns a mapping function, often through a tiny neural network or other model, between high-quality solutions from different tasks. Knowledge is transferred by applying this mapping to convert solutions from one task's space to another's [22]. While more computationally intensive, it can handle tasks with different representations.

- Neural Network-based Systems: For complex many-task optimization, larger neural networks can act as a central knowledge learning and transfer system, capable of capturing and sharing more intricate patterns across multiple tasks [22].

- LLM-Generated Models: A recent advancement involves using Large Language Models to autonomously design and generate novel knowledge transfer models. These frameworks optimize for both transfer effectiveness and efficiency, producing custom models that can compete with or outperform hand-crafted designs [22].

Comparative Analysis of Knowledge Transfer Methods

The performance of different knowledge transfer strategies varies significantly based on the nature of the optimization tasks and the chosen design. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of key methods based on empirical studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Knowledge Transfer Methods in EMTO

| Transfer Method | Optimal Task Similarity | Computational Overhead | Representation Flexibility | Reported Performance Gain | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical Crossover [3] [22] | High | Low | Low (Requires common representation) | +10-25% Convergence Speed | Performance drops sharply with low task similarity |

| Solution Mapping [22] | Medium to High | Medium | Medium | +15-30% Solution Quality | Requires prior mapping learning; burden increases with many tasks |

| Neural Network-based [22] | Low to High | High | High | +20-40% in Many-Task Scenarios | High design complexity and reliance on domain expertise |

| LLM-Generated Models [22] | Adaptable | Variable (Optimized for efficiency) | High | Superior or Competitive vs. hand-crafted models | Eliminates need for expert knowledge, autonomous design |

Empirical Performance Data

A comprehensive empirical study comparing a state-of-the-art LLM-generated knowledge transfer model against established hand-crafted models demonstrates the competitive landscape [22]. The experiments were conducted on a suite of multi-task optimization benchmarks. Key findings include:

- The LLM-generated model consistently achieved superior or competitive performance in terms of both final solution quality (effectiveness) and the speed of convergence (efficiency).

- Traditional methods like vertical crossover showed strong performance only when task similarity was high, validating the limitation noted in the taxonomy.

- The neural network-based knowledge transfer system, while powerful, confirmed its high computational demand, but achieved the most robust performance across tasks with varying levels of similarity.

These results underscore a critical trade-off: simpler methods are efficient but brittle, while complex methods are robust but costly. The emergence of autonomously designed models (e.g., via LLMs) presents a promising path toward achieving robustness without prohibitive manual design effort [22].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Knowledge Transfer

To ensure the validity and reliability of the comparative data presented, the research community employs standardized experimental protocols. The workflow for a typical comparative experiment in EMTO is shown below.

Figure 2: Standard experimental workflow for comparing knowledge transfer methods in EMTO.

Detailed Methodologies

- Benchmark Selection and Problem Formulation: Experiments utilize well-established multi-task benchmark suites. These suites contain groups of optimization tasks (e.g., continuous functions, combinatorial problems) with pre-defined levels of inter-task similarity. The performance of any KT method is highly dependent on this similarity, so benchmarks are chosen to cover a spectrum from low to high correlation [3] [22].

- Algorithm Configuration and KT Integration: The KT method under investigation is integrated into a base EMTO framework, such as MFEA (Multi-Factorial Evolutionary Algorithm). A control group consisting of single-task evolutionary algorithms (EAs) run independently is always included to quantify the performance gain attributable to knowledge transfer. Key parameters, such as population size, number of generations, and KT-specific parameters (e.g., transfer frequency or mapping model size), are carefully controlled and documented to ensure a fair comparison [22].

- Performance Metrics and Data Collection: The primary metrics for evaluation are:

- Solution Quality: Measured as the average best fitness or error rate achieved over multiple independent runs at the end of the optimization process.

- Convergence Speed: Measured as the number of generations or function evaluations required to reach a pre-specified solution quality threshold.

- Positive/Negative Transfer Impact: The degree to which KT helps or hinders performance compared to the single-task EA control group [3].

- Statistical Analysis and Validation: Due to the stochastic nature of EAs, all experiments are repeated numerous times (e.g., 30 independent runs). The results are then subjected to statistical significance tests, such as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, to confirm that observed performance differences are not due to random chance. Finally, methods are often ranked across multiple benchmark problems to determine overall superiority [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing and experimenting with EMTO requires a suite of computational "reagents." The table below details key components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for EMTO Experimentation

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application in KT Research |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-task Benchmark Suites | Provides standardized test problems with known properties and inter-task correlations. | Serves as the ground truth for evaluating and comparing the performance and robustness of different KT methods. |

| Base EMTO Framework (e.g., MFEA) | Provides the foundational evolutionary algorithm structure and population management system. | Acts as the platform into which different KT modules (e.g., crossover, mapping models) are integrated and tested. |

| Similarity Measurement Toolbox | Algorithms to quantify the similarity between pairs of optimization tasks, often based on fitness landscape analysis. | Informs dynamic KT strategies by determining "when" and "between which tasks" to transfer knowledge. |

| Mapping Model Library | A collection of model architectures (e.g., tiny neural networks, linear transformers) for learning inter-task mappings. | The core component for explicit transfer methods; enables knowledge transfer between tasks with different solution representations. |

| LLM-based Model Generator | An autonomous system that uses Large Language Models to generate novel KT model code based on problem descriptions. | Used to explore the design space of KT models without manual coding, potentially discovering high-performing novel strategies. |

A Taxonomy of Transfer Strategies: From Implicit Sharing to Explicit Mapping

In the study of complex systems, from human societies to optimization algorithms, implicit transfer mechanisms facilitate the non-random movement of information, traits, or knowledge without direct instruction. This guide focuses on two fundamental processes: assortative mating, the tendency for individuals to partner with others similar to themselves, and cultural transmission, the transfer of information and behaviors through social learning. Within Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) research, understanding and mimicking these biological and cultural strategies is crucial for developing efficient knowledge transfer (KT) across simultaneous optimization tasks. When improperly managed, KT can lead to negative transfer, where information exchange between unrelated tasks deteriorates optimization performance [3] [23]. This guide objectively compares the performance of strategies inspired by these mechanisms, providing researchers with a framework for selecting and implementing effective transfer designs.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Assortative Mating as an Implicit Transfer Mechanism

Assortative mating arises when individuals with similar heritable trait values form partnerships more frequently than expected by chance. A key distinction exists between its two operational forms:

- Direct Assortment (Primary Phenotypic Assortment): Occurs when partner selection is directly conditional on the observed phenotype (e.g., educational attainment itself). This directly induces covariance between partners' genetic and environmental traits [24] [25].

- Indirect Assortment (Secondary Assortment): Occurs when partner similarity in a focal trait results from assortment on a secondary, correlated trait or "sorting factor" (e.g., cognitive ability or social background influencing educational attainment). This leads to different, often more complex, consequences for genetic and environmental correlations in subsequent generations [24] [25].

Table 1: Key Definitions in Assortative Mating Research

| Term | Definition | Implication for Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Homogamy | Assortment on genetic influences associated with a trait [24]. | Increases genetic similarity between partners and genetic variance in offspring. |

| Social Homogamy | Assortment within environmentally differentiated groups or on environmental factors [24] [26]. | Induces environmental similarity between partners without necessarily increasing genetic correlation. |

| Phenotypic Correlation | The observed correlation between partners' measurable traits (e.g., ~0.41 for education) [24]. | An observable outcome, but does not reveal the underlying mechanism (direct vs. indirect). |

| Genotypic Correlation | The correlation between partners' genetic predispositions (e.g., ~0.37 for education) [24] [25]. | Reveals the genetic consequences of assortment; can be higher than expected under direct assortment. |

Cultural Transmission as an Implicit Transfer Mechanism

Cultural transmission encompasses the pathways through which cultural traits—ideas, attitudes, skills, and knowledge—are passed on. These pathways are classified based on the relationship between the knowledge source and recipient:

- Vertical Transmission: Cultural traits are passed from biological parents to their offspring. This pathway is analogous to genetic inheritance but can involve different transmission rules [27].

- Horizontal Transmission: Individuals learn from peers of the same generation. This pathway can lead to the rapid spread of traits across a population [27].

- Oblique Transmission: Learning occurs from members of the previous generation who are not the biological parents (e.g., teachers, community elders) [27].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and pathways of these core implicit transfer mechanisms.

Experimental Protocols and Empirical Evidence

Key Methodologies for Studying Assortative Mating

Research on assortative mating relies on advanced statistical models applied to large-scale familial and genetic datasets.

- Extended Twin-Family Designs: This methodology extends beyond classical twin studies by incorporating data from monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins, their siblings, parents, offspring, and the spouses of all these individuals. The power of this design lies in comparing phenotypic resemblances across these diverse relationship types. For instance, while MZ twins share nearly 100% of their segregating genes, DZ twins and full siblings share about 50% on average. By including in-laws (e.g., siblings-in-law), who are genetically unrelated but connected through assortment, researchers can disentangle the effects of genetic transmission from those of cultural transmission and shared environment [26].

- Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with Polygenic Scores: Modern studies, such as those using the Correlation in Genetic Signals (rGenSi) model, integrate phenotypic data with polygenic scores (PGS). A PGS aggregates an individual's genetic predisposition for a trait across many common genetic variants. The rGenSi model uses SEM to account for measurement error in PGS and estimate parameters for latent genetic and phenotypic variables. This allows for the estimation of the true genetic correlation between partners, siblings, and even in-laws, and provides a statistical test for whether assortment is direct (a=1) or indirect (a<1) on the observed phenotype [25].

Key Methodologies for Studying Cultural Transmission

Experimental and modeling approaches are used to quantify cultural transmission pathways.

- Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) with Transmission Rules: ABMs simulate cultural evolution in a computational population. Agents are assigned cultural traits (e.g., A or B), and the next generation acquires traits based on predefined transmission rules. For vertical transmission, an offspring's trait is determined by a probabilistic function of its two parents' traits, potentially including a selection bias (s_v). For horizontal transmission, agents can adopt traits from peers within their generation after vertical transmission has occurred. These models can also incorporate assortative mating by controlling the parameter (a), which dictates the probability that parents will have the same cultural trait [27].

- Visual Statistical Learning (VSL) Paradigms: To study implicit learning and its transfer, controlled experiments like the Spatial Visual Statistical Learning (SVSL) design are used. Participants passively view scenes composed of abstract shapes that contain hidden statistical regularities (e.g., certain shapes always appear paired). Learning is measured implicitly through familiarity tests. Researchers can then investigate how this implicitly acquired knowledge is abstracted and transferred to novel contexts, and how sleep-dependent consolidation affects this transfer, differentiating it from explicit learning pathways [28].

Performance Comparison in Genetics and EMTO

Quantitative Evidence from Genetic and Behavioral Studies

Empirical research provides quantitative estimates of the effects of assortative mating and cultural transmission on trait variation.

Table 2: Quantitative Estimates of Assortative Mating and Transmission Effects

| Trait / Mechanism | Key Parameter | Estimated Value | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Attainment | Phenotypic Partner Correlation | ~0.41 | Norwegian Registry Data [24] |

| Educational Attainment | Genotypic Partner Correlation (rg) | 0.37 - 0.65 | Norwegian MoBa Study & UK Biobank [24] [25] |

| Educational Attainment | Sibling Genetic Correlation (rg) | 0.68 (>0.50 expected) | Norwegian MoBa Study [25] |

| Intelligence (FSIQ) | Variance from Additive Genetics | 44% | Extended Twin-Family Study [26] |

| Intelligence (FSIQ) | Variance from Cultural Transmission | 11% (via assortment) | Extended Twin-Family Study [26] |

| Height | Genotypic Partner Correlation (rg) | 0.13 | Norwegian MoBa Study [25] |

| Depression | Genotypic Partner Correlation (rg) | 0.08 | Norwegian MoBa Study [25] |

The following diagram visualizes the experimental workflow and logical relationships involved in a comprehensive extended twin-family study, which generates data like that in Table 2.

Algorithmic Performance in Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization

In EMTO, algorithms inspired by cultural transmission and assortative mating principles have been developed to manage knowledge transfer, with performance measured on benchmark optimization problems.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Select EMTO Algorithms

| Algorithm (Model) | Core Transfer Strategy | Key Performance Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT-EMT-MOES (Cultural Transmission) | Elite-guided variation & adaptive horizontal transmission. | Superior/convergence & diversity on MOMTO benchmarks; reduces negative transfer; works well with small populations. [23] | |

| MFEA (Multifactorial Evolution) | Implicit KT via unified search space and assortative mating. | Foundational algorithm; performance can deteriorate vs. single-task EA if tasks have low correlation (negative transfer). [3] | |

| MFEA-AKT & Others (Adaptive KT) | Dynamically adjusts inter-task transfer probability. | Outperforms MFEA by measuring task similarity or positive transfer amount to mitigate negative transfer. [3] [23] |

This section details key datasets, models, and methodological tools that function as essential "research reagents" in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Implicit Transfer

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function and Application | Example / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extended Twin-Family Datasets | Dataset | Provides phenotypic and genetic data across multiple relationship types to disentangle genetic and cultural transmission effects. | Netherlands Twin Register (NTR) [26], Norwegian Mother, Father, and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) [25] |

| Polygenic Score (PGS) | Genetic Tool | A quantitative index of an individual's genetic predisposition for a trait, used to estimate genetic correlations between relatives and in-laws. | Educational Attainment PGS [25], Height PGS [25] |

| Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) | Statistical Method | Fits models to data to estimate latent variables (e.g., true genetic value) and test hypotheses about direct/indirect paths of transmission. | rGenSi Model [25], OpenMx, Mplus |