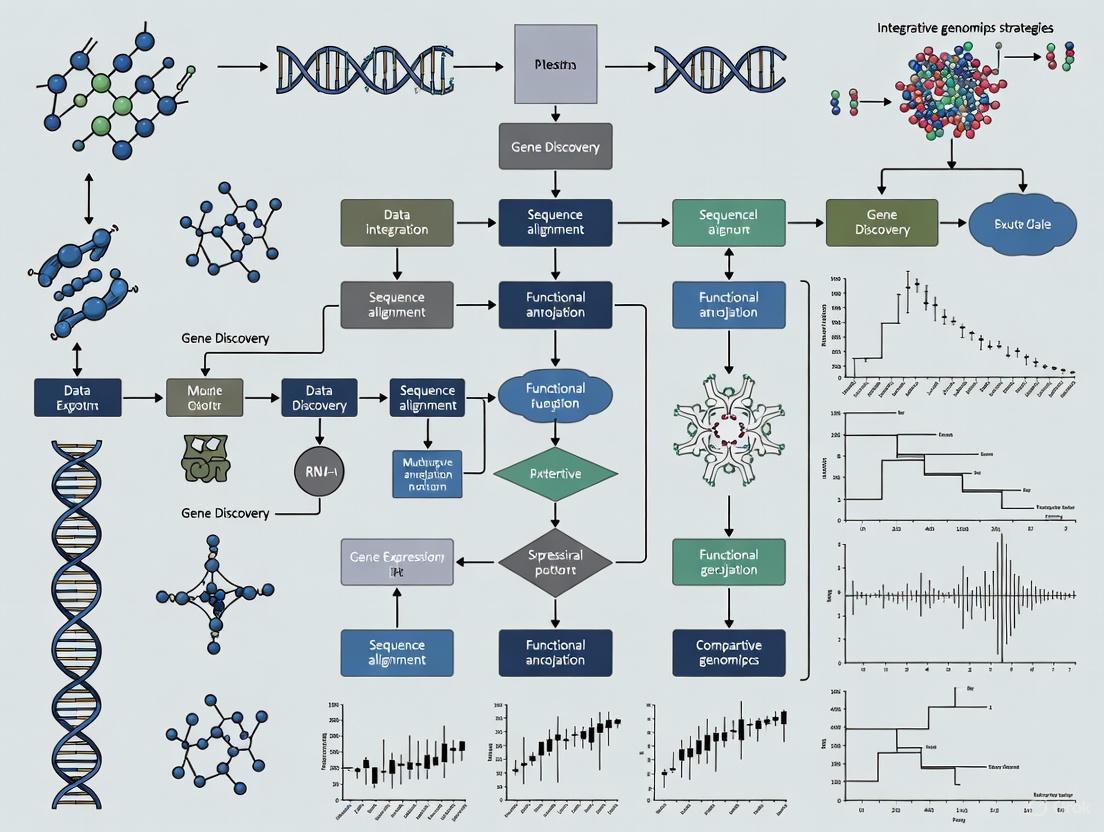

Integrative Genomics Strategies for Gene Discovery: From Data to Therapies

Integrative genomics represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving beyond single-modality analyses to combine genomic, transcriptomic, and other molecular data for comprehensive gene discovery.

Integrative Genomics Strategies for Gene Discovery: From Data to Therapies

Abstract

Integrative genomics represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving beyond single-modality analyses to combine genomic, transcriptomic, and other molecular data for comprehensive gene discovery. This approach leverages high-throughput sequencing, artificial intelligence, and sophisticated computational frameworks to identify disease-causing genes, elucidate biological networks, and accelerate therapeutic development. By intersecting genotypic data with molecular profiling and clinical phenotypes, researchers can establish causal relationships between genetic variants and complex diseases with unprecedented precision. This article explores the foundational concepts, methodological applications, optimization strategies, and validation frameworks that underpin successful integrative genomics, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a roadmap for harnessing these powerful strategies in their work.

The Systems Biology Revolution: Foundations of Integrative Genomics

The field of gene discovery has undergone a fundamental transformation, shifting from a reductionist model to a systems biology framework. Traditional reductionist approaches operated on a "one-gene, one-disease" principle, focusing on single molecular targets and linear receptor-ligand mechanisms. While effective for monogenic or infectious diseases, this paradigm demonstrated significant limitations when addressing complex, multifactorial disorders like cancer, neurodegenerative conditions, and metabolic syndromes [1]. These diseases involve intricate networks of molecular interactions with redundant pathways that diminish the efficacy of single-target approaches.

Modern integrative genomics strategies now embrace biological complexity through holistic modeling of gene, protein, and pathway networks. This systems-based paradigm leverages artificial intelligence (AI), multi-omics data integration, and network analysis to identify disease modules and multi-target therapeutic strategies [2] [1]. The clinical impact of this shift is substantial, with network-aware approaches demonstrating potential to reduce clinical trial failure rates from 60-70% associated with traditional methods to more sustainable levels through pre-network analysis and improved target validation [1].

Comparative Analysis: Paradigm Evolution in Gene Discovery

Table 1: Key Distinctions Between Traditional and Systems Biology Approaches in Gene Discovery

| Feature | Traditional Reductionist Approach | Systems Biology Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting Strategy | Single-target | Multi-target / network-level [1] |

| Disease Suitability | Monogenic or infectious diseases | Complex, multifactorial disorders [1] |

| Model of Action | Linear (receptor–ligand) | Systems/network-based [1] |

| Risk of Side Effects | Higher (off-target effects) | Lower (network-aware prediction) [1] |

| Failure in Clinical Trials | Higher (60–70%) | Lower due to pre-network analysis [1] |

| Primary Technological Tools | Molecular biology, pharmacokinetics | Omics data, bioinformatics, graph theory, AI [1] |

| Personalized Therapy Potential | Limited | High potential (precision medicine) [1] |

| Data Utilization | Hypothesis-driven, structured datasets | Hypothesis-agnostic, multimodal data integration [2] |

Application Note: Implementing Integrative Genomics for Novel Gene-Disease Association Discovery

Protocol: Gene Burden Analytical Framework for Rare Diseases

The following protocol outlines the application of a systems biology approach to identify novel gene-disease associations in rare diseases, based on the geneBurdenRD framework applied in the 100,000 Genomes Project (100KGP) [3].

Purpose: To systematically identify novel gene-disease associations through rare variant burden testing in large-scale genomic cohorts.

Primary Applications:

- Discovery of novel disease-gene associations for Mendelian diseases

- Prioritization of candidate genes for functional validation

- Molecular diagnosis for rare disease patients undiagnosed after standard genomic sequencing

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedures:

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Curation

- Obtain whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing data from 34,851 cases and family members (recommended cohort size) [3]

- Collect comprehensive phenotypic data using standardized ontologies (e.g., HPO)

- Utilize Exomiser variant prioritization tool for initial variant annotation and filtering [3]

Step 2: Variant Quality Control and Filtering

- Filter to rare protein-coding variants (allele frequency <0.1% in population databases)

- Remove possible false positive variant calls through quality thresholding

- Apply inheritance pattern considerations for variant prioritization [3]

Step 3: Case-Control Definition and Statistical Analysis

- Define cases by recruited disease category with specific inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Assign controls from within the cohort using family members or other disease categories

- Perform gene-based burden testing using the geneBurdenRD R framework [3]

- Apply statistical models tailored for Mendelian diseases and unbalanced case-control studies [3]

Step 4: In Silico Triage and Prioritization

- Evaluate genetic evidence strength (p-values, effect sizes)

- Assess functional genomic evidence (protein impact, conservation)

- Integrate independent experimental evidence from literature and databases [3]

Step 5: Clinical Expert Review

- Multidisciplinary review of prioritized associations

- Correlation with patient phenotypes

- Assessment of biological plausibility

Expected Outcomes: In the 100KGP application, this framework identified 141 new gene-disease associations, with 69 prioritized after expert review and 30 linked to existing experimental evidence [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Databases for Integrative Genomics

| Category | Tool/Database | Primary Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Prioritization | Exomiser [3] | Annotation and prioritization of rare variants | Initial processing of WGS/WES data |

| Statistical Framework | geneBurdenRD [3] | R package for gene burden testing in rare diseases | Core statistical analysis |

| Gene-Disease Associations | OMIM [1] | Catalog of human genes and genetic disorders | Validation and comparison of novel associations |

| Protein-Protein Interactions | STRING [1] | Database of protein-protein interactions | Network analysis of candidate genes |

| Pathway Analysis | KEGG [1] | Collection of pathway maps | Functional contextualization of findings |

| Drug-Target Interactions | DrugBank [1] | Comprehensive drug-target database | Therapeutic implications of discoveries |

| Genomic Data | 100,000 Genomes Project [3] | Large-scale whole-genome sequencing database | Primary data source for analysis |

Application Note: AI-Driven Platform for Holistic Target Discovery and Drug Development

Protocol: Multi-Modal AI Platform for Target Identification and Validation

Purpose: To leverage artificial intelligence for systems-level target identification and therapeutic candidate optimization through holistic biology modeling.

Primary Applications:

- Identification of novel therapeutic targets for complex diseases

- Design of novel drug-like molecules with optimized properties

- Prediction of clinical trial outcomes and patient selection criteria

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedures:

Step 1: Multi-Modal Data Integration and Knowledge Graph Construction

- Integrate 1.9 trillion data points from 10+ million biological samples (RNA sequencing, proteomics) [2]

- Process 40+ million documents (patents, clinical trials, literature) using Natural Language Processing (NLP) [2]

- Construct biological knowledge graphs embedding gene-disease, gene-compound, and compound-target interactions [2]

- Apply transformer-based architectures to focus on biologically relevant subgraphs [2]

Step 2: Target Identification and Prioritization

- Leverage PandaOmics module for target discovery [2]

- Analyze multimodal data (phenotype, omics, patient data, chemical structures, texts, images) [2]

- Prioritize targets based on novelty, druggability, and network centrality

- Use attention-based neural architectures for hypothesis refinement [2]

Step 3: Generative Molecular Design

- Employ Chemistry42 module with deep learning (GANs, reinforcement learning) [2]

- Design novel drug-like molecules with multi-objective optimization (potency, metabolic stability, bioavailability) [2]

- Apply policy-gradient-based reinforcement learning for parameter balancing [2]

- Generate synthetically accessible small molecules constrained by automated chemistry infrastructure [2]

Step 4: Preclinical Validation and Clinical Translation

- Predict human pharmacokinetics and clinical outcomes using multi-modal transformer architectures [2]

- Utilize inClinico module for trial outcome prediction using historical and ongoing trial data [2]

- Optimize patient selection and endpoint selection through AI-driven insights [2]

- Implement continuous active learning with iterative feedback from experimental data [2]

Expected Outcomes: This integrated approach has demonstrated the capability to identify novel targets and develop clinical-grade drug candidates with accelerated timelines. For example, Insilico Medicine reported the discovery and validation of a small-molecule TNIK inhibitor targeting fibrosis in both preclinical and clinical models within an accelerated timeframe [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: AI Platform Components

Table 3: Core AI Technologies for Systems Biology Drug Discovery

| Platform Component | Technology | Function | Data Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Discovery | PandaOmics [2] | Identifies and prioritizes novel therapeutic targets | 1.9T data points, 10M+ biological samples, 40M+ documents |

| Molecule Design | Chemistry42 [2] | Designs novel drug-like molecules with optimized properties | Generative AI, reinforcement learning, multi-objective optimization |

| Trial Prediction | inClinico [2] | Predicts clinical trial outcomes and optimizes design | Historical and ongoing trial data, patient data |

| Phenotypic Screening | Recursion OS [2] | Maps trillions of biological relationships using phenotypic data | ~65 petabytes of proprietary data, cellular imaging |

| Knowledge Integration | Biological Knowledge Graphs [2] | Encodes biological relationships into vector spaces | Gene-disease, gene-compound, compound-target interactions |

| Validation Workflow | CONVERGE Platform [2] | Closed-loop ML system integrating human-derived data | 60+ terabytes of human gene expression data, clinical samples |

Signaling Pathways and Network Pharmacology in Systems Biology

The systems biology approach recognizes that most complex diseases involve dysregulation of multiple interconnected pathways rather than isolated molecular defects. Network pharmacology leverages this understanding to develop therapeutic strategies that modulate entire disease networks.

Key Network Analysis Methodologies:

- Topological Analysis: Identification of hub nodes and bottleneck proteins using graph-theoretical measures (degree centrality, betweenness, closeness) [1]

- Module Detection: Application of community detection algorithms (MCODE, Louvain) to identify functional modules in biological networks [1]

- Multi-Omics Integration: Fusion of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to create comprehensive patient-specific models [1]

- Machine Learning Integration: Use of support vector machines (SVM), random forests, and graph neural networks (GNN) to predict novel drug-target interactions [1]

This paradigm has demonstrated particular success in explaining the mechanisms of traditional medicine systems where multi-component formulations act on multiple targets simultaneously, and in drug repurposing efforts such as the application of metformin as an anticancer agent [1].

Integrative genomics represents a paradigm shift in gene discovery research, moving beyond single-omics approaches to combine multiple layers of biological information. The availability of complete genome sequences and the wealth of large-scale biological data sets now provide an unprecedented opportunity to elucidate the genetic basis of rare and common human diseases [4]. This integration is particularly crucial in precision oncology, where cancer's staggering molecular heterogeneity demands innovative approaches beyond traditional single-omics methods [5]. The integration of multi-omics data, spanning genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics and radiomics, significantly improves diagnostic and prognostic accuracy when accompanied by rigorous preprocessing and external validation [5].

The fundamental challenge in modern biomedical research lies in the biological complexity that arises from dynamic interactions across genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolomic strata, where alterations at one level propagate cascading effects throughout the cellular hierarchy [5]. Traditional reductionist approaches, reliant on single-omics snapshots or histopathological assessment alone, fail to capture this interconnectedness, often yielding incomplete mechanistic insights and suboptimal clinical predictions [5]. This protocol details the methodologies for systematic integration of genomic, transcriptomic, and clinical data to enable more faithful descriptions of gene function and facilitate the discovery of genes underlying Mendelian disorders and complex diseases [4].

Core Data Types and Their Characteristics

Molecular Data Components

The integration framework relies on three primary data layers, each providing orthogonal yet interconnected biological insights that collectively construct a comprehensive molecular atlas of health and disease [5]. The table below summarizes the core data types, their descriptions, and key technologies.

Table 1: Core Data Types in Integrative Genomics

| Data Type | Biological Significance | Key Components Analyzed | Primary Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Identifies DNA-level alterations that drive disease [5] | Single nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variations (CNVs), structural rearrangements [5] | Whole genome sequencing (WGS), SNP arrays [6] [7] |

| Transcriptomics | Reveals active transcriptional programs and regulatory networks [5] | mRNA expression, gene fusion transcripts, non-coding RNAs [5] | RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) [5] |

| Clinical Data | Provides phenotypic context and health outcomes [6] | Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms, imaging data, laboratory results, environmental factors [6] | EHR systems, standardized questionnaires, imaging platforms [6] |

Data Standards and Ontologies

Standardized notation for metadata using controlled vocabularies or ontologies is essential to enable the harmonization of datasets for secondary research analyses [7]. For clinical and phenotypic data, the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) provides a standardized vocabulary for describing phenotypic abnormalities [6]. The use of existing data standards and ontologies that are generally endorsed by the research community is strongly encouraged to facilitate comparison across similar studies [7]. For genomic data, the NIH Genomic Data Sharing (GDS) Policy applies to single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array data, genome sequence data, transcriptomic data, epigenomic data, and other molecular data produced by array-based or high-throughput sequencing technologies [7].

Experimental Design and Patient Recruitment Protocols

Patient Selection Criteria

Standardized protocols must be designed and developed specifically for clinical information collection and obtaining trio genomic information from affected individuals and their parents [6]. For studies focusing on congenital anomalies, the target population typically includes neonatal patients with major multiple congenital anomalies who were negative for all items based on existing conventional test results [6]. These tests should include complete blood count, clinical chemical tests, blood gas analysis, urinalysis, newborn screening for congenital metabolic disorders, chromosomal analysis, and microarray analysis [6].

In rapidly advancing medical environments, there has been an increasing trend of performing targeted single gene testing or gene panel testing based on the phenotype expressed by the patient when there is clinical suspicion of involvement of specific genetic regions [6]. Therefore, participation in comprehensive integration studies should be limited to cases where the results of single gene testing or gene panel testing were negative or inconclusive in explaining the patient's phenotypes from a medical perspective [6]. The final decision regarding suitability should involve multiple specialists discussing potential participation, with a research manager or officer making the ultimate determination [6].

Informed Consent and Ethical Considerations

A robust consent system for the collection and utilization of human biological materials and related information must be established [6]. The key elements of the consent form should include voluntary participation, purpose/methods/procedures of the study, anticipated risks and discomfort, anticipated benefits, and personal information protection [6]. For studies that generate genomic data from human specimens and cell lines, NHGRI strongly encourages obtaining participant consent either for general research use through controlled access or for unrestricted access [7].

Explicit consent for future research use and broad data sharing should be documented for all human data generated by research [7]. Consent language should avoid both restrictions on the types of users who may access the data and restrictions that add additional requirements to the access request process [7]. Informed consent documents for prospective data collection should state what data types will be shared and for what purposes, and whether sharing will occur through open or controlled-access databases [7].

Data Generation and Collection Methodologies

Biospecimen Collection and Processing

Blood samples should be collected from study participants and their parents in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-treated tubes [6]. Parents may also provide urine samples [6]. These samples should be processed to create research resources, including plasma, genomic DNA, and urine, which should be stored in a −80 °C freezer for preservation [6]. A total of 138 human biological resources, including plasma, genomic DNA, and urine samples, were obtained in a referenced study, as well as 138 sets of whole-genome sequencing data [6].

Genomic and Transcriptomic Data Generation

Whole genome sequencing should be performed using blood samples from target individuals and their parents [6]. The library can be prepared using the TruSeq Nano DNA Kit, with massively parallel sequencing performed using a NovaSeq6000 with paired-end reads of 150 bp [6]. FASTQ data should be aligned to the human reference genome using Burrows–Wheeler Alignment, with data preprocessing and variant calling performed using the Haplotype Caller Genome Analysis Toolkit [6]. Variants should be annotated using ANNOVAR [6]. The samples should have a mean depth of at least 30×, with more than 95% coverage of the human reference genome at more than 10×, and at least 85% of the databases should achieve a quality score of Q30 or higher [6].

Clinical and Epidemiological Data Collection

Demographic and clinical data from patients and their parents should be collected using standardized protocols [6]. Phenotype information according to the Human Phenotype Ontology term and major test findings should be recorded [6]. To gather information on environmental factors associated with disease occurrence, a questionnaire and a case record form should be developed, assessing exposure during and prior to pregnancy [6]. Key items on this questionnaire should include occupational history, exposure to hazardous substances in residential areas, medication intake, smoking, alcohol consumption, radiation exposure, increased body temperature, and cell phone use [6]. For assessing exposure to fine particulate matter, modeling should be utilized when an address is available [6].

Data Processing and Integration Workflows

Computational Preprocessing Pipelines

The computational workflow for data integration involves multiple preprocessing steps to ensure data quality and compatibility. The diagram below illustrates the core workflow for multi-omics data integration.

Data Harmonization and Quality Control

Data normalization and harmonization represent the first hurdle in integration [8]. Different labs and platforms generate data with unique technical characteristics that can mask true biological signals [8]. RNA-seq data requires normalization to compare gene expression across samples, while proteomics data needs intensity normalization [8]. Batch effects from different technicians, reagents, sequencing machines, or even the time of day a sample was processed can create systematic noise that obscures real biological variation [8]. Careful experimental design and statistical correction methods like ComBat are required to remove these effects [8].

Missing data is a constant challenge in biomedical research [8]. A patient might have genomic data but be missing transcriptomic measurements [8]. Incomplete datasets can seriously bias analysis if not handled with robust imputation methods, such as k-nearest neighbors or matrix factorization, which estimate missing values based on existing data [8]. The samples should have a mean depth of at least 30×, with more than 95% coverage of the human reference genome at more than 10× [6].

Integration Strategies and Computational Approaches

AI-Powered Integration Frameworks

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning and deep learning, has emerged as the essential scaffold bridging multi-omics data to clinical decisions [5]. Unlike traditional statistics, AI excels at identifying non-linear patterns across high-dimensional spaces, making it uniquely suited for multi-omics integration [5]. The table below compares the primary integration strategies used in multi-omics research.

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

| Integration Strategy | Timing of Integration | Key Advantages | Common Algorithms | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Before analysis [8] | Captures all cross-omics interactions; preserves raw information [8] | Simple concatenation, autoencoders [8] | Extremely high dimensionality; computationally intensive [8] |

| Intermediate Integration | During analysis [8] | Reduces complexity; incorporates biological context through networks [8] | Similarity Network Fusion, matrix factorization [8] | Requires domain knowledge; may lose some raw information [8] |

| Late Integration | After individual analysis [8] | Handles missing data well; computationally efficient [8] | Ensemble methods, weighted averaging [8] | May miss subtle cross-omics interactions [8] |

Advanced Machine Learning Techniques

Multiple advanced machine learning techniques have been developed specifically for multi-omics integration:

Autoencoders and Variational Autoencoders: Unsupervised neural networks that compress high-dimensional omics data into a dense, lower-dimensional "latent space" [8]. This dimensionality reduction makes integration computationally feasible while preserving key biological patterns [8].

Graph Convolutional Networks: Designed for network-structured data where genes and proteins represent nodes and their interactions represent edges [8]. GCNs learn from this structure, aggregating information from a node's neighbors to make predictions [8].

Similarity Network Fusion: Creates a patient-similarity network from each omics layer and then iteratively fuses them into a single comprehensive network [8]. This process strengthens strong similarities and removes weak ones, enabling more accurate disease subtyping [8].

Transformers: Originally from language processing, transformers adapt to biological data through self-attention mechanisms that weigh the importance of different features and data types [8]. This allows them to identify critical biomarkers from a sea of noisy data [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful integration of genomic, transcriptomic, and clinical data requires both wet-lab reagents and sophisticated computational tools. The table below details the essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item/Technology | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | TruSeq Nano DNA Kit | Library preparation for sequencing [6] | Whole genome sequencing library prep |

| NovaSeq6000 | Massively parallel sequencing platform [6] | High-throughput sequencing | |

| EDTA-treated blood collection tubes | Prevents coagulation for DNA analysis [6] | Biospecimen collection and preservation | |

| Computational Tools | Burrows–Wheeler Alignment | Alignment to reference genome [6] | Sequence alignment (hg19) |

| Genome Analysis Toolkit | Variant discovery and calling [6] | Preprocessing and variant calling | |

| ANNOVAR | Functional annotation of genetic variants [6] | Variant annotation and prioritization | |

| ComBat | Statistical method for batch effect correction [8] | Data harmonization across batches | |

| Data Resources | Human Phenotype Ontology | Standardized vocabulary for phenotypic abnormalities [6] | Clinical data annotation |

| dbGaP | Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes for controlled access data [7] | Data sharing and dissemination |

Data Sharing and Repository Submission

Data Management and Sharing Protocols

Broad data sharing promotes maximum public benefit from federally funded research, as well as rigor and reproducibility [7]. For studies involving humans, responsible data sharing is important for maximizing the contributions of research participants and promoting trust [7]. NHGRI supports the broadest appropriate data sharing with timely data release through widely accessible data repositories [7]. These repositories may be open access or controlled access [7]. NHGRI is also committed to ensuring that publicly shared datasets are comprehensive and Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable [7].

When determining where to submit data, investigators should first determine whether the Notice of Funding Opportunity includes specific repository expectations [7]. If not, AnVIL serves as the primary repository for NHGRI-funded data, metadata and associated documentation [7]. AnVIL supports submission of a variety of data types and accepts both controlled-access and unrestricted data [7]. Study registration in dbGaP is required for large-scale human genomic studies, including those submitting data to AnVIL [7].

Timelines and Metadata Requirements

NHGRI follows the NIH's expectation for submission and release of scientific data, with the exception that for genomic data, NHGRI expects non-human genomic data that are subject to the NIH GDS Policy to be submitted and released on the same timeline as human genomic data [7]. NHGRI-funded and supported researchers are expected to share the metadata and phenotypic data associated with the study, use standardized data collection protocols and survey instruments for capturing data, and use standardized notation for metadata to enable the harmonization of datasets for secondary research analyses [7].

Validation and Interpretation Frameworks

Biological Validation Strategies

The validation of findings from integrated data requires multiple orthogonal approaches. The diagram below illustrates the key relationships in biological validation of integrated genomic findings.

Interpretation in Clinical Context

The integration of multi-omics data with insights from electronic health records marks a paradigm shift in biomedical research, offering holistic views into health that single data types cannot provide [8]. This approach enables comprehensive disease understanding by revealing how genes, proteins, and metabolites interact to drive disease [8]. It facilitates personalized treatment by matching patients to therapies based on their unique molecular profile [8]. Furthermore, it allows for early disease detection by finding novel biomarkers for diagnosis before symptoms appear [8].

Updating and recording of clinical symptoms and genetic information that have been newly added or changed over time are significant for long-term tracking of patient outcomes [6]. Protocols should enable long-term tracking by including the growth and development status that reflect the important characteristics of patients [6]. Using these clinical and genetic information collection protocols, an essential platform for early genetic diagnosis and diagnostic research can be established, and new genetic diagnostic guidelines can be presented in the near future [6].

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research, bringing a paradigm shift in how scientists investigate genetic information. These high-throughput technologies provide unparalleled capabilities for analyzing DNA and RNA molecules, enabling comprehensive insights into genome structure, genetic variations, and gene expression profiles [9]. For gene discovery research, integrative genomics strategies leverage multiple sequencing approaches to build a complete molecular portrait of biological systems. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) captures the entire genetic blueprint, Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) focuses on protein-coding regions where most known disease-causing variants reside, and RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) reveals the dynamic transcriptional landscape [10] [11]. The power of integrative genomics emerges from combining these complementary datasets, allowing researchers to correlate genetic variants with their functional consequences, thereby accelerating the identification of disease-associated genes and pathways.

The evolution of NGS technologies has been remarkable, progressing from first-generation Sanger sequencing to second-generation short-read platforms like Illumina, and more recently to third-generation long-read technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore [9] [12]. This rapid advancement has dramatically reduced sequencing costs while exponentially increasing throughput, making large-scale genomic studies feasible. Contemporary NGS platforms can simultaneously sequence millions to billions of DNA fragments, providing the scale necessary for comprehensive genomic analyses [9]. The versatility of these technologies has expanded their applications across diverse research domains, including rare genetic disease investigation, cancer genomics, microbiome analysis, infectious disease surveillance, and population genetics [9] [13]. As these technologies continue to mature, they form an essential foundation for gene discovery research by enabling an integrative approach to understanding the complex relationships between genotype and phenotype.

Technology Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

Technology Platforms and Principles

High-throughput sequencing encompasses multiple technology generations, each with distinct biochemical approaches and performance characteristics. Second-generation platforms, predominantly represented by Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis technology, utilize fluorescently labeled reversible terminator nucleotides to enable parallel sequencing of millions of DNA clusters on a flow cell [9] [12]. This approach generates massive amounts of short-read data (typically 75-300 base pairs) with high accuracy (error rates typically 0.1-0.6%) [12]. Alternative second-generation methods include Ion Torrent's semiconductor sequencing that detects hydrogen ions released during DNA polymerization, and SOLiD sequencing that employs a ligation-based approach [9].

Third-generation sequencing technologies have emerged to address limitations of short-read platforms, particularly for resolving complex genomic regions and detecting structural variations. Pacific Biosciences' Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing immobilizes individual DNA polymerase molecules within nanoscale wells called zero-mode waveguides, monitoring nucleotide incorporation in real-time without amplification [9]. This technology produces long reads (averaging 10,000-25,000 base pairs) that effectively span repetitive elements and structural variants. Similarly, Oxford Nanopore Technologies sequences individual DNA or RNA molecules by measuring electrical current changes as nucleic acids pass through protein nanopores [9] [12]. Nanopore sequencing can generate extremely long reads (averaging 10,000-30,000 base pairs) and enables real-time data analysis, though with higher error rates (up to 15%) that can be mitigated through increased coverage [9].

Comparative Performance of WGS, WES, and RNA-seq

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Sequencing Approaches

| Feature | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Target | Entire genome, including coding and non-coding regions [10] | Protein-coding exons (1-2% of genome) [14] [10] | Transcriptome (all expressed genes) [11] |

| Target Size | ~3.2 billion base pairs (human) | ~30-60 million base pairs (varies by capture kit) [14] | Varies by tissue type and condition |

| Data Volume per Sample | Large (~100-150 GB) [10] | Moderate (~5-15 GB) [10] | Moderate (~5-20 GB, depends on depth) |

| Primary Applications | Discovery of novel variants, structural variants, non-coding regulatory elements, comprehensive variant detection [10] [15] | Identification of coding variants, Mendelian disease gene discovery, clinical diagnostics [14] | Gene expression quantification, differential expression, splicing analysis, fusion detection [11] |

| Detectable Variants | SNVs, CNVs, InDels, SVs, regulatory elements [10] | SNVs, small InDels, CNVs in coding regions [14] [10] | Expression outliers, splicing variants, gene fusions, allele-specific expression [11] |

| Cost Considerations | Higher per sample [10] | More cost-effective for large cohorts [14] [10] | Moderate cost, depends on sequencing depth |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | High (large data volumes, complex structural variant calling) [10] | Moderate (focused analysis, established pipelines) | Moderate to high (complex transcriptome assembly, isoform resolution) |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Commercial Exome Capture Kits (Based on Systematic Evaluation)

| Exome Capture Kit | Manufacturer | Target Size (bp) | Coverage of CCDS | Coverage of CCDS ±25 bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twist Human Comprehensive Exome | Twist Biosciences | 36,510,191 | 0.9991 | 0.7783 |

| SureSelect Human All Exon V7 | Agilent | 35,718,732 | 1 | 0.7792 |

| SureSelect Human All Exon V8 | Agilent | 35,131,620 | 1 | 0.8214 |

| KAPA HyperExome V1 | Roche | 42,988,611 | 0.9786 | 0.8734 |

| Twist Custom Exome | Twist Biosciences | 34,883,866 | 0.9943 | 0.7717 |

| DNA Prep with Exome 2.5 | Illumina | 37,453,133 | 0.9949 | 0.7813 |

| xGen Exome Hybridization Panel V1 | IDT | 38,997,831 | 0.9871 | 0.772 |

| SureSelect Human All Exon V6 | Agilent | 60,507,855 | 0.9178 | 0.8773 |

| ExomeMax V2 | MedGenome | 62,436,679 | 0.9951 | 0.9061 |

| Easy Exome Capture V5 | MGI | 69,335,731 | 0.996 | 0.8741 |

| SureSelect Human All Exon V5 | Agilent | 50,446,305 | 0.885 | 0.8387 |

Systematic evaluations of commercial WES platforms reveal significant differences in capture efficiency and target coverage. Recent analyses demonstrate that Twist Biosciences' Human Comprehensive Exome and Custom Exome kits, along with Roche's KAPA HyperExome V1, perform particularly well at capturing their target regions at both 10X and 20X coverage depths, achieving the highest capture efficiency for Consensus Coding Sequence (CCDS) regions [14]. The CCDS project identifies a core set of human protein-coding regions that are consistently annotated and of high quality, making them a critical benchmark for exome capture efficiency [14]. Notably, target size does not directly correlate with comprehensive coverage, as some smaller target designs (approximately 37Mb) demonstrate superior performance in covering clinically relevant regions [14]. When selecting an exome platform, researchers must consider both the uniformity of coverage and efficiency in capturing specific regions of interest, particularly for clinical applications where missed coverage could impact variant detection.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Whole Genome Sequencing Protocol

The WGS workflow begins with quality control of genomic DNA, requiring high-molecular-weight DNA with minimal degradation. The Tohoku Medical Megabank Project, which completed WGS for 100,000 participants, established rigorous quality control measures using fluorescence dye-based quantification (e.g., Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit) and visual assessment of DNA integrity [15].

Library Preparation Steps:

- DNA Fragmentation: Genomic DNA is diluted to 10-20 ng/μL and fragmented using focused-ultrasonication (e.g., Covaris LE220) to an average target size of 550 bp [15].

- Library Construction: For Illumina platforms, use TruSeq DNA PCR-free HT sample prep kit with IDT for Illumina TruSeq DNA Unique Dual indexes for 96 samples. For MGI platforms, use MGIEasy PCR-Free DNA Library Prep Set [15].

- Automation: Implement automated liquid handling systems (e.g., Agilent Bravo for Illumina libraries, MGI SP-960 for MGI platforms) to ensure reproducibility and throughput [15].

- Library QC: Measure concentration with Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit and analyze size distribution using Fragment Analyzer or TapeStation system with RNA ScreenTape [15].

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries on appropriate platforms (Illumina NovaSeq series or MGI DNBSEQ-T7) following manufacturers' protocols. For population-scale projects, aim for ~30x coverage for confident variant calling [15].

Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Adhere to GATK Best Practices pipeline: align FASTQ files to reference genome (GRCh38) using BWA or BWA-mem2 [15].

- Perform base quality score recalibration before variant calling with GATK HaplotypeCaller [15].

- Execute multi-sample joint calling using GATK GnarlyGenotyper followed by variant filtration with GATK VariantQualityScoreRecalibration [15].

WGS Experimental and Computational Workflow

Whole Exome Sequencing Protocol

WES utilizes hybrid capture technology to enrich protein-coding regions before sequencing, providing a cost-effective alternative to WGS for focused analysis of exonic variants. The core principle involves biotinylated DNA or RNA oligonucleotide probes complementary to target exonic regions, which hybridize to genomic DNA fragments followed by magnetic bead-based capture and enrichment [14].

Library Preparation and Target Enrichment:

- Library Preparation: Fragment 50-200ng genomic DNA to 100-700bp fragments using ultrasonication (e.g., Covaris E210) [16]. Perform end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation using library preparation kits compatible with downstream capture systems.

- Pre-capture Pooling: For multiplexed processing, pool multiple libraries (e.g., 8-plex hybridization) with 250ng per library for a total of 2000ng input per capture reaction [16].

- Hybridization and Capture: Hybridize with exome capture probes (e.g., Twist, IDT, Agilent, or Roche kits) for recommended duration (typically 16-24 hours). Use appropriate hybridization buffers and conditions specified by manufacturer [14] [16].

- Post-capture Amplification: Amplify captured libraries with 12 cycles of PCR using primers compatible with your sequencing platform [16].

- Quality Control: Assess capture efficiency by calculating the percentage of on-target reads, coverage uniformity, and depth across target regions.

Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Process raw sequencing data through similar alignment steps as WGS (BWA alignment, duplicate marking, base quality recalibration) [14].

- Calculate sequencing metrics using tools like Picard CollectHsMetrics to assess capture efficiency, coverage depth, and uniformity [14].

- Perform variant calling with GATK HaplotypeCaller or similar tools, focusing on target regions defined in the capture kit BED file [14].

RNA Sequencing Protocol

RNA-seq enables transcriptome-wide analysis of gene expression, alternative splicing, and fusion events. In cancer research, combining RNA-seq with WES substantially improves detection of clinically relevant alterations, including gene fusions and expression changes associated with somatic variants [11].

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- RNA Extraction and QC: Isolate total RNA using appropriate kits (e.g., AllPrep DNA/RNA kits for simultaneous DNA/RNA isolation). Assess RNA quality using RIN (RNA Integrity Number) scores on TapeStation or Bioanalyzer [11].

- Library Preparation: For fresh frozen tissue, use TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina) to select for polyadenylated transcripts. For FFPE samples, use capture-based methods like SureSelect XTHS2 RNA kit (Agilent) [11].

- Sequencing: Sequence on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 or similar platforms, aiming for 50-100 million reads per sample depending on experimental goals [11].

Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Align RNA-seq reads to reference genome (hg38) using STAR aligner with default parameters [11].

- Quantify gene expression using Kallisto or similar tools aligned to human transcriptome [11].

- Detect fusion genes using specialized fusion detection algorithms (e.g., Arriba, STAR-Fusion).

- Call variants from RNA-seq data using RNA-aware tools like Pisces to identify expressed somatic variants [11].

RNA-seq Computational Analysis Workflow

Integrated DNA-RNA Sequencing Protocol

Combining WES with RNA-seq from the same sample significantly enhances the detection of clinically relevant alterations in cancer and genetic disease research. This integrated approach enables direct correlation of somatic alterations with gene expression consequences, recovery of variants missed by DNA-only testing, and improved detection of gene fusions [11].

Simultaneous DNA/RNA Extraction:

- Use AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) for coordinated isolation of both nucleic acids from the same tissue specimen [11].

- For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, use AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit with appropriate modifications for degraded material [11].

- Assess DNA and RNA quality and quantity using Qubit, NanoDrop, and TapeStation systems before library preparation [11].

Parallel Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Process DNA and RNA libraries separately using optimized protocols for each nucleic acid type [11].

- For DNA: Use WES capture kits (e.g., SureSelect Human All Exon V7) following standard hybridization protocols [11].

- For RNA: Use either mRNA enrichment (TruSeq stranded mRNA kit) or exome capture-based RNA sequencing (SureSelect XTHS2 RNA kit) [11].

- Sequence both libraries on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 or similar high-throughput platforms [11].

Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Process DNA and RNA data through separate but parallel bioinformatics pipelines [11].

- Perform quality control metrics specific to each data type: for WES, assess coverage uniformity and on-target rates; for RNA-seq, evaluate sequencing saturation and strand specificity [11].

- Integrate findings by correlating somatic variants with allele-specific expression, validating splice-altering variants with RNA splicing patterns, and confirming fusion genes with both DNA and RNA evidence [11].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for High-Throughput Sequencing

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen), Autopure LS (Qiagen) [15] [11] | Simultaneous DNA/RNA isolation, automated high-throughput processing, high molecular weight DNA preservation |

| RNA Extraction Kits | AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen) [11] | Coordinated DNA/RNA extraction, optimized for FFPE samples, maintains RNA integrity |

| WES Capture Kits | Twist Human Comprehensive Exome, Roche KAPA HyperExome V1, Agilent SureSelect V7/V8, IDT xGen Exome Hyb Panel [14] | High CCDS coverage, uniform coverage, efficient capture of coding regions, compatibility with automation |

| Library Prep Kits | TruSeq DNA PCR-free HT (Illumina), MGIEasy PCR-Free DNA Library Prep Set (MGI), TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina) [15] [11] | PCR-free options reduce bias, strand-specific RNA sequencing, compatibility with automation systems |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq X, NovaSeq 6000, MGI DNBSEQ-T7, PacBio Sequel/Revio, Oxford Nanopore [9] [13] [15] | High-throughput short-read, long-read technologies, real-time sequencing, structural variant detection |

| Automation Systems | Agilent Bravo, MGI SP-960, Biomek NXp, MGISP-960 [15] | High-throughput library preparation, reduced human error, improved reproducibility |

| QC Instruments | Qubit Fluorometer, Fragment Analyzer, TapeStation, Bioanalyzer [15] [11] | Accurate nucleic acid quantification, size distribution analysis, RNA quality assessment (RIN) |

Integrative Genomics Applications in Gene Discovery

The true power of high-throughput sequencing emerges when multiple technologies are integrated to build a comprehensive molecular profile. Integrative genomics combines WGS, WES, and RNA-seq data to uncover novel disease genes and mechanisms that would remain hidden when using any single approach in isolation.

In cancer genomics, combined RNA and DNA exome sequencing applied to 2,230 clinical tumor samples demonstrated significantly improved detection of clinically actionable alterations compared to DNA-only testing [11]. This integrated approach enabled direct correlation of somatic variants with allele-specific expression changes, recovery of variants missed by traditional DNA analysis, and enhanced detection of gene fusions and complex genomic rearrangements [11]. The combined assay identified clinically actionable alterations in 98% of cases, highlighting the utility of multi-modal genomic profiling for personalized cancer treatment strategies [11].

For rare genetic disease research, WES has become a first-tier diagnostic test that delivers higher coverage of coding regions than WGS at lower cost and data management requirements [14]. However, integrative approaches that combine WES with RNA-seq from clinically relevant tissues can identify splicing defects and expression outliers that explain cases where WES alone fails to provide a diagnosis [11]. This is particularly important given that approximately 10% of exonic variants analyzed in rare disease studies alter splicing [14]. Adding a ±25 bp padding to exonic targets during capture and analysis further improves detection of these splice-altering variants located near exon boundaries [14].

Functional genomics has been revolutionized by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which enables transcriptomic profiling at individual cell resolution [17]. This technology reveals cellular heterogeneity, maps differentiation pathways, and identifies rare cell populations that are masked in bulk tissue analyses [17]. In cancer research, scRNA-seq dissects tumor microenvironment complexity and identifies resistant subclones within tumors [13] [17]. In developmental biology, it traces cellular trajectories during embryogenesis, and in neurological diseases, it maps gene expression patterns in affected brain regions [13] [17]. The integration of scRNA-seq with genomic data from the same samples provides unprecedented resolution for connecting genetic variants to their cellular context and functional consequences.

High-throughput sequencing technologies have fundamentally transformed gene discovery research, with WGS, WES, and RNA-seq each offering complementary strengths for comprehensive genomic characterization. WGS provides the most complete variant detection across coding and non-coding regions, WES offers a cost-effective focused approach for coding variant discovery, and RNA-seq reveals the functional transcriptional consequences of genetic variation [10] [11]. The integration of these technologies creates a powerful framework for integrative genomics, enabling researchers to move beyond simple variant identification to understanding the functional mechanisms underlying genetic diseases.

As sequencing technologies continue to advance, several emerging trends are poised to further enhance their utility for gene discovery. Third-generation long-read sequencing is improving genome assembly and structural variant detection [9] [12]. Single-cell multi-omics approaches are enabling correlated analysis of genomic variation, gene expression, and epigenetic states within individual cells [17]. Spatial transcriptomics technologies are adding geographical context to gene expression patterns within tissues [13] [12]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms are increasingly being deployed to extract meaningful patterns from complex multi-omics datasets [13]. These advances, combined with decreasing costs and improved analytical methods, promise to accelerate the pace of gene discovery and deepen our understanding of the genetic architecture of human disease.

For researchers embarking on gene discovery projects, the selection of appropriate sequencing technologies should be guided by specific research questions, sample availability, and analytical resources. WES remains the most cost-effective approach for focused coding region analysis in large cohorts, while WGS provides comprehensive variant detection for discovery-oriented research. RNA-seq adds crucial functional dimension to both approaches, particularly for identifying splicing defects and expression outliers. By strategically combining these technologies within an integrative genomics framework, researchers can maximize their potential to uncover novel disease genes and mechanisms, ultimately advancing our understanding of human biology and disease.

The conventional single-gene model has proven insufficient for unraveling the complex etiology of most heritable traits. Complex traits are governed by polygenic influences, environmental factors, and intricate interactions between them, constituting a highly multivariate genetic architecture. Integrative genomics strategies that simultaneously analyze multiple layers of genomic information are crucial for gene discovery in this context. This Application Note details a protocol for discovering and fine-mapping genetic variants influencing multivariate latent factors derived from high-dimensional molecular traits, moving beyond univariate genome-wide association study (GWAS) approaches to capture shared underlying biology [18].

Key Concepts and Quantitative Rationale

High-dimensional molecular phenotypes, such as blood cell counts or transcriptomic data, often exhibit strong correlations because they are driven by shared, underlying biological processes. Traditional univariate GWAS on each trait separately ignores these relationships, reducing statistical power and biological interpretability. This protocol uses the flashfmZero software to identify and analyze latent factors that capture the variation in observed traits generated by these shared mechanisms [18]. The following table summarizes the quantitative advantages of this multivariate approach as demonstrated in a foundational study.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Multivariate Latent Factor Analysis in the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) and Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) [18]

| Analysis Type | Number Identified | Key Statistical Threshold | Replication Rate in WHI | Notable Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis-irQTLs (isoform ratio QTLs) | Over 1.1 million (across 4,971 genes) | ( P < 5 \times 10^{-8} ) | 72% (( P < 1 \times 10^{-4} )) | 20% were specific to isoform regulation with no significant gene-level association. |

| Sentinel cis-irQTLs | 11,425 | - | 72% (( P < 1 \times 10^{-4} )) | - |

| trans-irQTLs | 1,870 sentinel variants (for 1,084 isoforms across 590 genes) | ( P < 1.5 \times 10^{-13} ) | 61% | Highlights distal regulatory effects. |

| Rare cis-irQTLs | 2,327 (for 2,467 isoforms of 1,428 genes) | ( 0.003 < MAF < 0.01 ) | 41% | Extends discovery to low-frequency variants. |

Experimental Protocol: irQTL Mapping and Fine-Mapping

This protocol outlines the steps for performing genetic discovery and fine-mapping of multivariate latent factors from high-dimensional traits, as detailed by Astle et al. [18].

Prerequisites and Data Preparation

- Input Data: Requires individual-level or summary-level GWAS data for a panel of high-dimensional, correlated observed traits (e.g., RNA-seq data for transcript isoforms, proteomic data, blood cell parameters).

- Genotype Data: Whole-genome or high-density genotyping data for the same cohort.

- Software Installation: Install the

flashfmZerosoftware and its dependencies as per the official documentation.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Calculate GWAS Summary Statistics for Latent Factors

- Objective: Derive GWAS summary statistics that represent genetic associations with the underlying latent factors, not the raw observed traits.

- Procedure:

- a. From the matrix of observed high-dimensional traits, use

flashfmZeroto infer the latent factor structure. This generates a set of latent factors that explain the co-variance among the observed traits. - b. For each inferred latent factor, the software computes GWAS summary statistics, executing a form of multivariate GWAS. The protocol is designed to handle datasets with missing measurements in the trait data.

- a. From the matrix of observed high-dimensional traits, use

Identify Isoform Ratio QTLs (irQTLs)

- Objective: Discover genetic variants that significantly influence the splicing ratio of transcript isoforms.

- Procedure:

- a. Using the GWAS summary statistics from Step 1, conduct a genome-wide scan for variants associated with the isoform-to-gene expression ratio.

- b. Apply a standard genome-wide significance threshold (e.g., ( P < 5 \times 10^{-8} )) to define significant

cis-irQTLs(within ±1 Mb of the transcript). - c. For

trans-irQTLanalysis, use a more stringent threshold (e.g., ( P < 1.5 \times 10^{-13} )) to account for the larger search space and reduce false positives.

Select Sentinel Variants and Conduct Replication

- Objective: Identify the lead independent genetic signals and validate them in an independent cohort.

- Procedure:

- a. For each locus with a significant irQTL, identify the sentinel variant—the variant with the strongest association signal, often after linkage disequilibrium (LD) clumping.

- b. Test these sentinel irQTLs for replication in an independent dataset (e.g., WHI). A ( P < 1 \times 10^{-4} ) can be used as a replication significance threshold.

Joint Fine-Mapping of Multiple Latent Factors

- Objective: Determine the likely causal variants at associated loci by accounting for shared information across multiple related latent factors.

- Procedure:

- a. Using the

flashfmZeroframework, perform joint fine-mapping of associations from multiple latent factors. This step integrates association signals across traits to improve causal variant identification's resolution and accuracy compared to fine-mapping each trait independently. - b. The output provides a posterior probability for each variant within a locus, indicating the probability that it is the causal driver of the association signal across the multivariate phenotype.

- a. Using the

downstream Functional Validation

- Mendelian Randomization: Apply Mendelian randomization techniques to the fine-mapped irQTLs to investigate causal relationships between the identified isoform shift and complex clinical traits (e.g., diastolic blood pressure) [18].

- Enrichment Analysis: Test for enrichment of the identified irQTLs in functional genomic annotations (e.g., splice donor/acceptor sites) and against known GWAS loci from public repositories to prioritize variants with potential clinical relevance [18].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: irQTL Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for irQTL Mapping and Analysis

| Resource Name / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

flashfmZero Software |

Software Package | Core analytical tool for performing multivariate GWAS on latent factors and joint fine-mapping [18]. |

| GWAS Catalog | Database | Public repository of published GWAS results for enrichment analysis and validation of identified loci [19]. |

| GENCODE | Database | Reference annotation for the human genome; provides the definitive set of gene and transcript models used to define isoforms [19]. |

| dbGaP | Data Repository | Primary database for requesting controlled-access genomic and phenotypic data from studies like FHS and WHI, as used in this protocol [18]. |

| MR-Base Platform | Software Platform | A platform that supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome using Mendelian randomization, a key downstream validation step [19]. |

In the field of integrative genomics, distinguishing causal genetic factors from mere associations is fundamental to understanding disease etiology and developing effective therapeutic interventions. While Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and other associational approaches have successfully identified thousands of genetic variants linked to diseases, they often fall short of establishing causality due to confounding factors, linkage disequilibrium, and pleiotropy [20]. The discovery of causal relationships enables researchers to move beyond correlation to understand the mechanistic underpinnings of disease, which is critical for drug target validation and precision medicine [4].

The limitations of association studies are well-documented. For instance, variants identified through GWAS often explain only a small fraction of the estimated heritability of complex traits, and high pleiotropy complicates the identification of true causal genes [20]. Furthermore, observational correlations can be misleading, as demonstrated by the historical example of hormone replacement therapy, where initial observational studies suggested reduced heart disease risk, but randomized controlled trials later showed increased risk [20]. These challenges highlight the critical need for robust causal inference frameworks in gene-disease discovery.

Foundational Frameworks and Key Concepts

Core Causal Inference Frameworks

Two primary frameworks form the theoretical foundation for causal inference in genetics: Rubin's Causal Model (RCM), also known as the potential outcomes framework, and Pearl's Causal Model (PCM) utilizing directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) and structural causal models [20]. RCM defines causality through the comparison of potential outcomes under different treatment states, while PCM provides a graphical representation of causal assumptions and relationships. These frameworks enable researchers to formally articulate causal questions and specify the assumptions required for valid causal conclusions from observational data [20].

Genetic Specific Concepts and Challenges

Several genetic-specific concepts are crucial for causal inference. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) complicates the identification of causal variants from GWAS signals, as multiple correlated variants may appear associated with a trait [20]. Pleiotropy, where a single genetic variant influences multiple traits, can lead to spurious conclusions if not properly accounted for [20]. Colocalization analysis addresses some limitations of GWAS by testing whether the same causal variant is responsible for association signals in both molecular traits (e.g., gene expression) and disease traits, providing stronger evidence for causality [20].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Genetic Causal Inference

| Concept | Description | Challenge for Causal Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage Disequilibrium | Non-random association of alleles at different loci | Makes it difficult to identify the true causal variant among correlated signals |

| Pleiotropy | Single genetic variant affecting multiple traits | Can create confounding if the variant influences the disease through multiple pathways |

| Genetic Heterogeneity | Different genetic variants causing the same disease | Complicates the identification of consistent causal factors across populations |

| Collider Bias | Selection bias induced by conditioning on a common effect | Can create spurious associations between two unrelated genetic factors |

Methodological Approaches for Causal Gene Discovery

Mendelian Randomization

Mendelian randomization (MR) uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to infer causal relationships between modifiable exposures or biomarkers and disease outcomes [21]. This approach leverages the random assortment of alleles during meiosis, which reduces confounding, making it analogous to a randomized controlled trial. MR has been successfully applied to evaluate potential causal biomarkers for common diseases, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [21].

The Causal Pivot Framework

The Causal Pivot (CP) is a novel structural causal model specifically designed to address genetic heterogeneity in complex diseases [21]. This method leverages established causal factors, such as polygenic risk scores (PRS), to detect the contribution of additional suspected causes, including rare variants. The CP framework incorporates outcome-induced association by conditioning on disease status and includes a likelihood ratio test (CP-LRT) to detect causal signals [21].

The CP framework exploits the collider bias phenomenon, where conditioning on a common effect (disease status) induces a correlation between independent causes (e.g., PRS and rare variants). Rather than treating this as a source of bias, the CP uses this induced correlation as a source of signal to test causal relationships [21]. Applied to UK Biobank data, the CP-LRT has successfully detected causal signals for hypercholesterolemia, breast cancer, and Parkinson's disease [21].

Integrative Genomic Approaches

Integrative approaches combine multiple data types to strengthen causal inference. Methods such as Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies (TWAS) examine associations at the transcript level, while Proteome-Wide Association Studies (PWAS) assess the effect of variants on protein biochemical functions [20]. These approaches operate under the assumption that variants in gene regulatory regions can drive alterations in phenotypes and diseases, providing intermediate molecular evidence for causal relationships.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Causal Inference Methods in Genetics

| Method | Underlying Principle | Data Requirements | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mendelian Randomization | Uses genetic variants as instrumental variables | GWAS summary statistics for exposure and outcome | Inferring causal effects of biomarkers on disease risk |

| Causal Pivot | Models collider bias from conditioning on disease status | Individual-level genetic data, PRS, rare variant calls | Detecting rare variant contributions conditional on polygenic risk |

| Colocalization | Tests shared causal variants across molecular and disease traits | GWAS and molecular QTL data (eQTL, pQTL) | Prioritizing candidate causal genes and biological pathways |

| TWAS/PWAS | Integrates transcriptomic/proteomic data with genetic associations | Gene expression/protein data, reference panels | Identifying causal genes through molecular intermediate traits |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Causal Pivot Analysis for Case-Only Design

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing the Causal Pivot framework using a cases-only design to detect rare variant contributions to complex diseases.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Causal Pivot Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Data | Individual-level genotype data (e.g., array or sequencing) | Primary input for generating genetic predictors |

| Polygenic Risk Scores | Pre-calculated or derived from relevant GWAS summary statistics | Represents common variant contribution to disease liability |

| Rare Variant Calls | Annotated rare variants (MAF < 0.01) from sequencing data | Candidate causal factors for testing |

| Phenotypic Data | Disease status, covariates (age, sex, ancestry PCs) | Outcome measurement and confounding adjustment |

| Statistical Software | R or Python with specialized packages (e.g., CP-LRT implementation) | Implementation of causal inference algorithms |

Procedure

Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Perform standard genotype quality control: exclude variants with call rate < 95%, individuals with excessive missingness, and genetic outliers

- Calculate principal components to account for population stratification

- Annotate rare variants (MAF < 0.01) in disease-relevant genes

Polygenic Risk Score Calculation

- Obtain GWAS summary statistics for the target disease from a large independent study

- Clump SNPs to remove those in linkage disequilibrium (r² > 0.1 within 250kb window)

- Calculate PRS for each individual using PRSice2 or similar tools

Causal Pivot Likelihood Ratio Test Implementation

- For cases only, model the relationship between rare variant status (G) and PRS (X)

- Estimate parameters using conditional maximum likelihood procedure

- Compute test statistic under the null hypothesis of no rare variant effect

Ancestry Confounding Adjustment

- Apply matching, inverse probability weighting, or doubly robust methods to address ancestry confounding

- Validate results across different adjustment approaches

Interpretation and Validation

- Significant CP-LRT signals indicate causal contribution of rare variants conditional on PRS

- Perform cross-disease and synonymous variant analyses as negative controls

Protocol 2: Colocalization Analysis for Causal Variant Fine-Mapping

This protocol describes the steps for performing colocalization analysis to determine if molecular QTL and disease GWAS signals share a common causal variant.

Procedure

Data Collection and Harmonization

- Obtain GWAS summary statistics for the disease of interest

- Acquire molecular QTL data (e.g., eQTL, pQTL) from relevant tissues

- Harmonize effect alleles across datasets and ensure consistent genomic builds

Locus Definition

- Define genomic regions based on LD blocks surrounding GWAS significant hits

- Typically use ±500kb around lead GWAS variants as initial loci

Colocalization Testing

- Apply Bayesian colocalization methods (e.g., COLOC) that assume one causal variant per trait

- Alternatively, use fine-mapping integrated approaches (e.g., eCAVIAR, SuSiE) for multiple causal variants

- Calculate posterior probabilities for shared causal variants

Sensitivity Analysis

- Test robustness of colocalization results to prior specifications

- Evaluate consistency across different molecular QTL datasets

Biological Interpretation

- Prioritize genes with strong colocalization evidence (PP4 > 0.8)

- Integrate with functional genomic annotations to validate findings

Large-scale biobanks have emerged as invaluable resources for causal inference in genetics, providing harmonized repositories of diverse data including genetic, clinical, demographic, and lifestyle information [20]. These resources capture real-world medical events, procedures, treatments, and diagnoses, enabling robust causal investigations.

The NCBI Gene database provides gene-specific connections integrating map, sequence, expression, structure, function, citation, and homology data [22]. It comprises sequences from thousands of distinct taxonomic identifiers and represents chromosomes, organelles, plasmids, viruses, transcripts, and proteins, serving as a fundamental resource for gene-disease relationship discovery.

For gene-disease association extraction, the TBGA dataset provides a large-scale, semi-automatically annotated resource based on the DisGeNET database, consisting of over 200,000 instances and 100,000 gene-disease pairs extracted from more than 700,000 publications [23]. This dataset enables the training and validation of relation extraction models to support causal discovery.

Workflow Visualization

Causal Pivot Analytical Workflow

Causal Gene Discovery Integration Framework

The integration of causal inference frameworks into gene-discovery research represents a paradigm shift from correlation to causation in understanding disease genetics. Methods such as the Causal Pivot, Mendelian randomization, and colocalization analysis provide powerful approaches to address the challenges of genetic heterogeneity, pleiotropy, and confounding. As biobanks continue to grow in scale and diversity, and as computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, causal inference will play an ever more critical role in identifying bona fide therapeutic targets and advancing precision medicine.

Future directions in the field include the development of methods that can integrate across omics layers (transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics) to build comprehensive causal models of disease pathogenesis, and the creation of increasingly sophisticated approaches to address ancestry-related confounding and ensure that discoveries benefit all populations equally.

Methodological Frameworks and Real-World Applications

Integrative genomics represents a paradigm shift in gene discovery research, moving beyond the limitations of single-omics approaches to provide a comprehensive understanding of complex biological systems. By combining data from multiple molecular layers—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics—researchers can now uncover causal genetic mechanisms underlying disease susceptibility and identify high-confidence therapeutic targets with greater precision [24] [25]. This Application Note provides detailed methodologies and protocols for three fundamental pillars of integrative genomics: expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping, transcriptome-wide Mendelian randomization (TWMR), and biological network analysis. These approaches, when applied synergistically, enable the identification of functionally relevant genes and pathways through the strategic integration of genetic variation, gene expression, and phenotypic data within a causal inference framework [26] [27] [28].

The protocols outlined herein are specifically designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in target identification and validation. Emphasis is placed on practical implementation considerations, including computational tools, data resources, and analytical workflows that leverage large-scale genomic datasets such as the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project and genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics [26] [29] [28]. By adopting these multi-omics integration strategies, researchers can accelerate the translation of genetic discoveries into mechanistic insights and ultimately, novel therapeutic interventions.

Integrated Analytical Framework

Table 1: Key Multi-Omics Techniques for Gene Discovery

| Technique | Primary Objective | Data Inputs | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| eQTL Mapping | Identify genetic variants regulating gene expression levels | Genotypes, gene expression data [27] | Variant-gene expression associations, tissue-specific regulatory networks |

| Transcriptome-Wide Mendelian Randomization (TWMR) | Infer causal relationships between gene expression and complex traits | eQTL summary statistics, GWAS data [26] | Causal effect estimates, prioritization of trait-relevant genes |

| Network Analysis | Contextualize findings within biological systems and pathways | Protein-protein interactions, gene co-expression data [30] | Molecular interaction networks, functional modules, key hub genes |

Workflow Integration Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and sequential integration of the three core methodologies within a comprehensive gene discovery pipeline:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: eQTL Mapping for Identification of Regulatory Variants

Background and Principles

Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping serves as a crucial bridge connecting genetic variation to gene expression, enabling the identification of genomic regions where genetic variants significantly influence the expression levels of specific genes [27]. This methodology has become foundational for interpreting GWAS findings and elucidating the functional consequences of disease-associated genetic variants. Modern eQTL mapping approaches must address several methodological challenges, including tissue specificity, multiple testing burden, and the need for appropriate normalization strategies to account for technical artifacts and biological confounders [31] [29].

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Genotype Processing: Perform standard quality control on genotype data, including filtering for call rate (>95%), Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 1×10⁻⁶), and minor allele frequency (>1%). Impute missing genotypes using reference panels (e.g., 1000 Genomes Project) [29].

- Expression Data Normalization: Process RNA-seq data using quantile normalization or relative log expression (RLE) normalization. Apply inverse normal transformation to expression residuals after covariate adjustment to ensure normality assumption validity [29].

- Covariate Adjustment: Calculate principal components from genotype data to account for population stratification. Include known technical covariates (sequencing batch, RIN scores) and biological covariates (age, sex) in the model [26] [29].

Step 2: Cis-eQTL Mapping Implementation

- Statistical Modeling: For each gene, test associations between normalized expression levels and genetic variants within a 1 Mb window of the transcription start site using linear regression or specialized count-based models [31].

- Model Selection: Consider implementing negative binomial generalized linear models with adjusted profile likelihood for dispersion estimation, as implemented in the quasar software, which demonstrates improved power and type 1 error control for RNA-seq data [31].

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply false discovery rate (FDR) control at 5% to identify significant eQTLs, accounting for the number of genes tested [26].

Step 3: Advanced Considerations

- Tissue-Specificity Analysis: Perform eQTL mapping across multiple tissues when data are available, noting that regulatory effects often demonstrate tissue-specific patterns [27] [28].

- Privacy-Preserving Mapping: For multi-center studies with data sharing restrictions, implement privacy-preserving frameworks like privateQTL, which uses secure multi-party computation to enable collaborative eQTL mapping without raw data exchange [29].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for eQTL Mapping

| Tool Name | Statistical Model | Key Features | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| quasar [31] | Linear, Poisson, Negative Binomial (GLMM) | Efficient implementation, adjusted profile likelihood for dispersion | Primary eQTL mapping with count-based RNA-seq data |

| tensorQTL [26] | Linear model | High performance, used by GTEx consortium | Large-scale cis-eQTL mapping |

| privateQTL [29] | Linear model | Privacy-preserving, secure multi-party computation | Multi-center studies with data sharing restrictions |

Protocol 2: Transcriptome-Wide Mendelian Randomization for Causal Inference

Background and Principles

Transcriptome-wide Mendelian randomization (TWMR) extends traditional Mendelian randomization principles to systematically test causal relationships between gene expression levels and complex traits. By leveraging genetic variants as instrumental variables for gene expression, TWMR overcomes confounding and reverse causation limitations inherent in observational studies [26] [28]. This approach integrates eQTL summary statistics with GWAS data to infer whether altered expression of specific genes likely causes changes in disease risk or other phenotypic traits.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Genetic Instrument Selection

- Instrument Strength: Select independent cis-eQTLs (linkage disequilibrium r² < 0.1) significantly associated with target gene expression (P < 5×10⁻⁸) located within ±1 Mb of the transcription start site [26].