Integrating Phylogeography and Species Diversification Patterns: From Genomic Insights to Drug Discovery Applications

This article synthesizes contemporary advances in phylogeography and its critical role in deciphering species diversification patterns.

Integrating Phylogeography and Species Diversification Patterns: From Genomic Insights to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This article synthesizes contemporary advances in phylogeography and its critical role in deciphering species diversification patterns. It explores foundational principles that underpin genetic diversity and population structure across taxa, from birds and plants to reptiles and insects. We detail cutting-edge methodological frameworks that integrate whole-genome sequencing with ecological niche modeling and chemotaxonomy. The discussion addresses troubleshooting for complex data interpretation, including mito-nuclear discordance and genomic localization of adaptive traits. Finally, we examine validation through comparative phylogeography and the direct application of these patterns in biomedical research, particularly in pharmacophylogeny for natural product-based drug discovery. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage evolutionary history for scientific and clinical innovation.

Unraveling the Drivers of Genetic Diversity and Population Structure

Phylogeography serves as a critical discipline bridging the fields of population genetics and macroevolutionary studies, aiming to elucidate the historical processes that shape the geographic distribution of genetic lineages. This whitepaper details three foundational concepts in modern phylogeographic research: genetic diversity, phylogeographic concordance, and glacial refugia. These concepts are indispensable for interpreting species' demographic histories, responses to past climatic oscillations, and future adaptive potential. Understanding these principles provides the framework for investigating diversification patterns across taxa and ecosystems, with significant implications for conservation biology, pharmaceutical resource management, and understanding evolutionary processes.

Core Conceptual Foundations

Genetic Diversity

Genetic diversity represents the sum of genetic characteristics within a species and serves as the foundational substrate for evolutionary change. It provides populations with the potential to adapt to environmental changes, with lower levels of genetic diversity frequently observed in threatened species [1]. This diversity is quantified using several key metrics:

- Haplotype Diversity (Hd): Measures the uniqueness of haplotypes within a population.

- Nucleotide Diversity (π): Quantifies the average number of nucleotide differences per site between two sequences.

- Private Allelic Richness: Counts alleles unique to a specific population or geographic region, often used to identify historical refugia [2] [1].

Spatial patterns of genetic diversity are not random but often form hotspots—geographic regions harboring exceptionally high diversity. Research on the common toad (Bufo bufo) demonstrated that these hotspots frequently result from secondary contact and admixture between previously isolated intraspecific lineages, effectively functioning as genetic "melting-pots" rather than solely as areas of prolonged bioclimatic stability [1].

Phylogeographic Concordance

Phylogeographic concordance describes the phenomenon where multiple, co-distributed species exhibit congruent phylogenetic breaks and geographic distribution patterns of genetic lineages. This congruence suggests that these taxa responded similarly to shared historical biogeographic barriers or climatic events [3] [4].

The concept of refugia within refugia has emerged from observations of phylogeographic concordance, particularly within major southern European peninsulas like Iberia. Rather than acting as a single unified refuge during Pleistocene glaciations, these regions contained multiple isolated refugia, each fostering distinct genetic lineages for a range of flora and fauna [4]. To move beyond qualitative assessments, researchers have developed quantitative methods like Phylogeographic Concordance Factors (PCFs), which statistically evaluate congruence across species, even when ancestral polymorphism has not completely sorted [3]. Studies in systems like the Sarracenia alata pitcher plant and its associated arthropods reveal that the degree of ecological interaction can predict the strength of phylogeographic congruence [3].

Glacial Refugia

In population biology, a refugium (plural: refugia) is a location that supports an isolated or relict population of a once more widespread species, often during periods of unfavorable climatic change such as the Pleistocene glacial maxima [5]. These sanctuaries are critical for species persistence and subsequent re-colonization.

Glacial refugia are not merely passive shelters; they actively shape genetic architecture. Populations confined to isolated refugia undergo allopatric divergence, potentially leading to speciation over time, as exemplified by Haffer's refugia theory for Amazonian birds [5]. During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), 24,000 to 15,000 years ago, temperate species experienced major range contractions, with many persisting in recognized southern refugia such as the Iberian, Italian, and Balkan peninsulas [2] [5]. However, growing evidence also supports the existence of cryptic northern refugia for some species, challenging simpler southern refugia models [2].

Table 1: Genetic Diversity Metrics and Their Interpretation in Phylogeographic Studies

| Metric | Description | Interpretation in Phylogeography |

|---|---|---|

| Haplotype Diversity (Hd) | Probability that two randomly sampled haplotypes are different in a population [1]. | High Hd suggests stable, large populations or admixture; Low Hd suggests recent expansion or bottlenecks. |

| Nucleotide Diversity (π) | Average number of nucleotide differences per site between two sequences [6]. | High π indicates ancient populations; Low π suggests recent founder events or selective sweeps. |

| Private Allelic Richness | Number of alleles unique to a specific geographic region, standardized via rarefaction [2]. | High private allelic richness strongly indicates a region was a glacial refugium [2]. |

| NST vs. GST | Comparison of two measures of population differentiation that incorporate (NST) or ignore (GST) phylogenetic relationships [6]. | NST > GST indicates significant phylogeographic structure (i.e., closely related haplotypes are co-located) [6]. |

Methodological Approaches and Analytical Techniques

Data Generation and Genetic Markers

Phylogeographic inference relies on data from various genetic markers, each with distinct properties and applications.

- Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA): Traditionally the workhorse of phylogeography due to its high mutation rate and maternal, haploid inheritance, which simplifies phylogenetic reconstruction. Studies often sequence genes like Cytochrome b (CytB) and 16s rRNA [7] [1].

- Nuclear DNA (nDNA): Includes sequenced regions like CGNL1, MAP1A, and β-fibint7 [7], and techniques like nuclear microsatellites (nSSR) [6]. These provide independent, biparentially inherited loci critical for detecting mito-nuclear discordance.

- Ancient DNA (aDNA): Allows for direct genetic analysis of past populations, providing a temporal dimension to test phylogeographic hypotheses [2].

Core Analytical Workflows

The modern phylogeographic pipeline integrates multiple analytical steps to reconstruct demographic history.

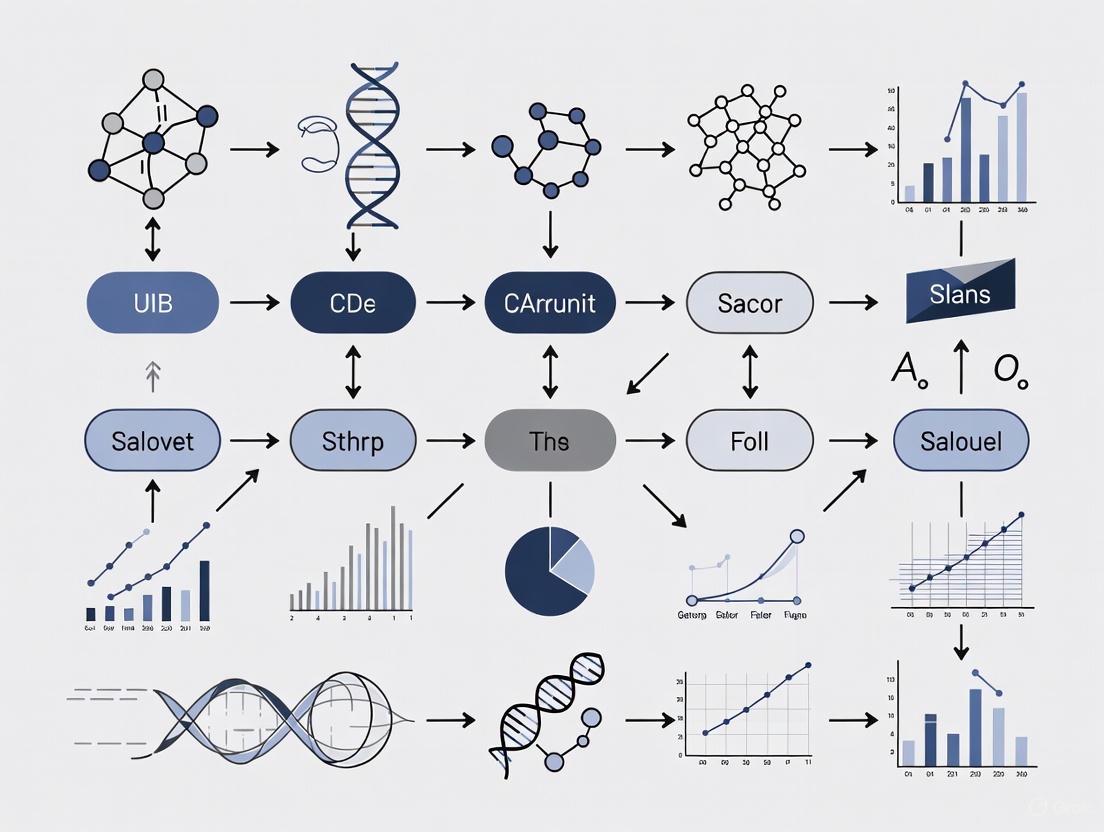

Diagram 1: Phylogeographic analysis workflow.

Testing Phylogeographic Hypotheses

A critical advancement in the field is the shift from descriptive patterns to model-based hypothesis testing.

- Coalescent Theory: Provides the statistical framework for building complex demographic models and estimating parameters like population divergence times, migration rates, and effective population sizes [8].

- Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC): Allows for the evaluation of competing historical scenarios (e.g., isolation vs. migration) and estimation of model parameters even when direct likelihood calculation is intractable [8].

- Phylogeographic Concordance Factors (PCFs): A novel method for quantifying congruence across co-distributed species, helping to distinguish between shared history and species-specific responses [3].

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols in Phylogeography

| Protocol | Key Steps | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial DNA Sequencing | 1. DNA extraction from tissue. 2. PCR amplification of target genes (e.g., CytB, control region). 3. Sanger sequencing. 4. Haplotype identification and alignment [1]. | Reconstructing maternal lineage history and identifying major genetic lineages [7] [1]. |

| Microsatellite (nSSR) Genotyping | 1. DNA extraction. 2. PCR with fluorescently-labeled primers. 3. Fragment analysis via capillary electrophoresis. 4. Genotype scoring and binning [6]. | Assessing contemporary gene flow, fine-scale population structure, and estimating recent demographic parameters [6]. |

| Ecological Niche Modeling (ENM) | 1. Compile contemporary species occurrence data. 2. Obtain bioclimatic variables for present and past (e.g., LGM). 3. Model species-climate relationship. 4. Project model to past climatic conditions to infer potential paleo-distributions [7] [9]. | Identifying potential locations of glacial refugia and inferring past range shifts [7] [1] [9]. |

| Comparative Phylogeographic Meta-Analysis | 1. Literature search and data curation (e.g., mtDNA control region sequences). 2. Standardize genetic diversity metrics (e.g., rarefaction of haplotype richness). 3. Map diversity and private allelic richness geographically. 4. Identify common patterns across taxa [2]. | Inferring general postglacial recolonization routes and identifying common refugia for a regional biota [2]. |

Integrative Case Studies in Phylogeography

Glacial Refugia and Postglacial Recolonization in European Mammals

A 2024 meta-analysis of 23 European mammal species revealed four major patterns of genetic diversity, each indicative of different refugial origins and postglacial colonization routes [2]:

- East-West Decline in Variation: Suggests species that survived the LGM in eastern refugia.

- Western-Central Belt of Highest Diversity: May indicate survival in cryptic northern refugia.

- Southern Richness: Corresponds to classic southern refugia in the Mediterranean peninsulas.

- Homogeneity with No Geographic Pattern: May result from panmixia or admixture from multiple refugia.

Synergistic Effects of Topography and Climate in Arid Asia

A 2025 study on the Central Asian racerunner lizard (Eremias vermiculata) combined mtDNA from 876 individuals with nuclear gene sequencing and ENM. It revealed four distinct mtDNA lineages that diversified approximately 1.18 million years ago, coinciding with major tectonic activity and climatic aridification [7]. The study documented mito-nuclear discordance, highlighting complex evolutionary dynamics where different genomic histories reveal the necessity of fine-scale genomic investigations [7].

Hotspots as Melting Pots in the Common Toad

Research on Bufo bufo in Italy demonstrated that its highest genetic diversity was not located in glacial refugia per se, but in secondary contact zones where differentiated lineages expanded and admixed. Generalized linear models identified genetic admixture as the only significant predictor of population genetic diversity, underscoring the role of admixture in generating biodiversity hotspots [1].

Phalanx Expansion in an Alpine Plant Complex

A study on the alpine Rosa sericea complex supported a phalanx expansion model during cold periods, contrary to the typical temperate species pattern. Environmental Niche Modeling indicated more suitable habitats during the LGM than at present. Neutrality tests and mismatch distribution analyses suggested demographic expansion during the middle to late Pleistocene, consistent with a cold-adapted species that expanded during glaciations and contracted during interglacials [6].

Diagram 2: Species responses to glacial-interglacial cycles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogeographic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroplast & Nuclear Gene Primers | PCR amplification of specific non-recombining genomic regions for phylogenetic analysis. | Primers for chloroplast genes rbcL, matK, trnH-psbA and nuclear ITS2 were used to reconstruct the evolutionary history of Morinda officinalis [9]. |

| Mitochondrial Gene Panel | Amplifying and sequencing mtDNA regions to establish matrilineal genealogies. | A panel of mtDNA genes (e.g., CytB, 16s rRNA) was sequenced in 231 common toads to identify phylogeographic lineages [1]. |

| Microsatellite (nSSR) Marker Set | Genotyping highly variable, codominant nuclear loci for fine-scale population analysis. | A set of 8 nSSR loci revealed three genetic groups within the Rosa sericea complex, independent of morphological taxonomy [6]. |

| Species Distribution Modeling Software | Projecting potential past, present, and future species ranges based on climatic data. | MAXENT or other ENM software was used to model the distribution of Eremias vermiculata during the LGM to infer refugia [7]. |

| Rarefaction Analysis Software (HP-RARE) | Standardizing genetic diversity metrics (like private allelic richness) for unequal sample sizes. | Used in a European mammal meta-analysis to ensure comparable estimates of private haplotype richness across studies [2]. |

The distribution of biodiversity across the planet is profoundly shaped by the interplay of geographic and ecological forces. Phylogeography, which examines the spatial arrangement of genetic lineages, provides a powerful framework for reconstructing how these forces drive speciation and diversification patterns over time [10]. Mountains, climatic shifts, and dispersal barriers represent particularly dynamic drivers in this process, creating complex patterns of organismal diversity through their combined effects [11] [12]. This whitepaper examines the mechanistic roles these forces play in generating biological diversity, with particular emphasis on their applications in comparative phylogeography and understanding diversification patterns across deep and shallow evolutionary timescales.

The conceptual foundation of this field rests on recognizing that geographic isolation (allopatry) and ecological divergence often act in concert to promote speciation [11] [13]. Mountainous regions, in particular, function as natural laboratories for studying these processes due to their exceptional habitat heterogeneity, strong environmental gradients, and complex geological histories [14] [15]. Furthermore, the ongoing effects of anthropogenic climate change make understanding these historical processes increasingly critical for predicting future biological responses [16] [14].

Theoretical Foundations: Speciation Mechanisms and Landscape Influences

Modes of Speciation in Geographic Context

Speciation, the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species, occurs through several geographic modes, each with distinct implications for diversification patterns:

Allopatric speciation: Occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated to an extent that prevents or interferes with gene flow [17]. This is typically subdivided into:

- Vicariance: The splitting of a species' range by the formation of an extrinsic barrier, such as mountain uplift or continental drift [17] [18].

- Peripatric speciation: A special case involving the isolation of a small peripheral population, often subject to strong genetic drift and selection [13] [17].

Parapatric speciation: Occurs with only partial separation of the zones of two diverging populations, with divergence happening along an environmental gradient without complete geographic isolation [13].

Sympatric speciation: The formation of two or more descendant species from a single ancestral species within the same geographic location, often through strong ecological specialization [13].

The relative importance of each mechanism continues to be debated, though evidence suggests allopatric speciation, particularly through vicariance, represents the most common geographic mode [17].

Mountain Systems as Drivers of Diversification

Mountain regions influence diversification through several interconnected mechanisms:

Habitat fragmentation: Geological and climatic events directly cause habitat reduction or fragmentation, creating barriers to gene flow and resulting in allopatric speciation [11]. The Sino-Himalayan region exemplifies this process, where tectonic movement and climatic oscillation since the Miocene have enhanced vascular plant richness and endemism [11].

Ecological divergence: Environmental gradients along elevation slopes provide diverse habitat types and high heterogeneity, enabling populations to adapt to novel ecological niches [11] [14]. This can lead to differentiation along elevation gradients, even without complete geographic isolation.

Sky island formation: Isolated mountain peaks function as "islands" in a "sea" of lowland areas, promoting divergence among populations separated by unsuitable habitat [12]. The Hengduan Mountains exhibit this phenomenon dramatically, with elevation variations ranging from approximately 1,000 meters to 7,556 meters creating distinct habitat zones [12].

Table 1: Mountain Regions as Biodiversity Hotspots

| Mountain Region | Key Diversification Forces | Notable Taxa Studied | Major Evolutionary Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sino-Himalayan Region | Tectonic uplift, monsoonal formation, habitat fragmentation | Megacodon, Beesia, Chamaesium | Combined effect of allopatry and ecological divergence common; late Miocene-Pliocene diversification [11] [12] |

| European Alps | Pleistocene glaciation, climatic oscillations, nunatak refugia | Androsace, Saxifraga, Senecio | Survival in interior Pleistocene refugia; polyploid complex formation [15] |

| Iranian Plateau | Environmental heterogeneity, geographic isolation | Asteraceae family | Priority hotspots for conservation; high endemism at mid-elevations [15] |

Key Analytical Frameworks and Methodologies

Molecular Approaches in Phylogeography

Modern phylogeography relies on multiple molecular marker systems to reconstruct evolutionary histories at various timescales:

Chloroplast genome sequencing: Particularly valuable for plants due to maternal inheritance and lower effective population sizes, providing insight into lineage divergence and historical biogeography [11] [12].

ddRAD-seq (double-digest Restriction-site Associated DNA sequencing): Enables high-resolution population genetics studies by sampling thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome, ideal for detecting fine-scale population structure [11].

Multi-locus sequence typing: Combining nuclear (e.g., ITS - internal transcribed spacer) and chloroplast markers (e.g., rpl16, trnT-trnL, trnQ-rps16) provides complementary perspectives on evolutionary history [12].

Whole genome sequencing: Offers the highest resolution for detecting divergence and gene flow, though still limited to model organisms or systems with substantial resources.

Table 2: Molecular Marker Applications in Phylogeography

| Marker Type | Resolution Level | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroplast sequences | Species to population | Phylogenetic relationships, historical biogeography | Maternal inheritance, haploid nature simplifies analysis | Limited recombination, slower evolution |

| Nuclear sequences (ITS) | Species to population | Phylogenetic relationships, hybridization detection | Biparental inheritance, faster evolution | Concerted evolution, multicopy nature |

| SNPs (ddRAD-seq) | Population to individual | Population structure, gene flow, local adaptation | Genome-wide coverage, high resolution | Complex bioinformatics, reference genome helpful |

| Morphological characters | Species | Taxonomic delimitation, fossil identification | Direct observation, fossil application | Subject to convergence, limited characters |

Bayesian Methods in Phylogenetic Inference

Bayesian methods have revolutionized molecular phylogenetics by enabling sophisticated statistical inference of evolutionary parameters:

Fundamental principle: Bayesian inference uses probability distributions to describe uncertainty in unknown parameters, combining prior knowledge with observed data through Bayes' theorem to generate posterior distributions [19].

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling: The computational workhorse for Bayesian phylogenetics, allowing approximation of complex posterior distributions that cannot be solved analytically [19].

Molecular clock dating: Incorporates fossil calibrations or substitution rates to estimate divergence times, essential for correlating phylogenetic splits with geological events [19] [10].

Ancestral state reconstruction: Infers past geographic distributions or ecological characteristics, enabling hypothesis testing about historical biogeographic patterns [10].

Total-evidence dating: Combines molecular data from extant species with morphological data from fossils in a unified phylogenetic framework, providing more robust estimates of divergence times and ancestral states [18].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for Bayesian phylogeographic analysis:

Ecological Niche Modeling

Ecological niche modeling (ENM) projects species distributions in geographic and environmental space, providing critical insights into range dynamics:

Climate envelope modeling: Correlates known species occurrences with environmental variables to identify suitable habitat conditions [16].

Range shift predictions: Models species responses to climate change by projecting future suitable habitats, often predicting upslope movements for mountain species [14].

Paleodistribution reconstruction: Uses paleoclimatic data to infer past species distributions, testing refugia hypotheses and range fragmentation scenarios [15].

Case Studies in Mountainous Regions

Sino-Himalayan Hotspot: A Comparative Phylogeographic Approach

The Sino-Himalayan region represents a temperate biodiversity hotspot with high levels of species endemism. A comparative study of Megacodon (Gentianaceae) and Beesia (Ranunculaceae) illustrates how ancient allopatry and ecological divergence jointly promote diversity [11]:

Evolutionary timing: Both genera began diverging from the late Miocene onward, coinciding with major orogenic events and climatic changes in the region [11].

Distribution patterns: Species in both genera exhibit fragmented distribution patterns, with narrow-range species or relict populations formed through ancient allopatry at lower elevations [11].

Elevational divergence: Megacodon shows two clades occupying entirely different altitudinal ranges, while Beesia calthifolia exhibits genetic divergence along an elevation gradient accompanied by distinct leaf shapes among elevational groups [11].

Statistical analyses: Mantel tests revealed isolation-by-distance patterns in Beesia and Megacodon stylophorus, indicating limitations to gene flow across geographic distances [11].

Chamaesium in the Himalayan-Hengduan Mountains

Research on Chamaesium (Apiaceae), a genus endemic to the Himalayan-Hengduan Mountains, provides insights into how mountain uplift and climatic oscillations drive species divergence:

Origin and timing: The ancestral group of Chamaesium originated in the southern Himalayan region at the beginning of the Paleogene (approximately 60.85 Ma), with species separating well during the last 25 million years starting in the Miocene [12].

Diversification drivers: The initial split was triggered by climate changes following the collision of the Indian plate with Eurasia during the Eocene, with later divergences induced by intense uplift of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, onset of the monsoon system, and Central Asian aridification [12].

Genetic patterns: High genetic differentiation among populations was observed, related to drastic environmental changes and limited seed/pollen dispersal capacity [12].

Distribution stability: Ecological niche modeling indicated broad-scale distributions remained fairly stable from the Last Interglacial to the present, with predicted stability into the future [12].

Alpine Plants in European Mountain Systems

Studies of European alpine plants reveal how Pleistocene climate fluctuations shaped current diversity patterns:

Nunatak refugia: Some high mountain plants survived Pleistocene glaciations on ice-free mountain tops (nunataks), not just in peripheral refugia, challenging traditional views [15].

Comparative phylogeography: Species with similar ecological requirements show similar phylogeographic patterns regardless of taxonomic affiliation, indicating ecological determinism in response to past climate change [15].

Polyploid complex evolution: Groups like Senecio carniolicus (Asteraceae) comprise multiple species with different ploidy levels, reflecting repeated cycles of isolation and secondary contact [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Phylogeographic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTAB extraction buffer | DNA isolation | Efficient extraction of high-quality DNA from plant tissues, particularly those with secondary compounds | Protocol for Chamaesium leaf tissue [12] |

| Chloroplast primers (e.g., rpl16, trnT-trnL) | Chloroplast sequencing | Amplification of non-coding chloroplast regions with sufficient variation for population-level studies | Population genetics of Chamaesium species [12] |

| Restriction enzymes (e.g., SbfI, MseI) | ddRAD-seq library preparation | Cleavage of genomic DNA at specific sites to generate reduced-representation libraries | Population structure analysis in Beesia and Megacodon [11] |

| Agarose gel matrix | Electrophoresis | Size separation of DNA fragments for quality control and purification | Standard molecular protocol [12] |

| Taq polymerase | PCR amplification | Enzymatic amplification of specific DNA regions for sequencing and genotyping | Standard molecular protocol [12] |

| ModelTest/jModelTest | Substitution model selection | Statistical selection of best-fit nucleotide substitution models | Phylogenetic analysis [19] |

Advanced Analytical Techniques

Hypothesis Testing in Biogeography

Modern biogeography employs sophisticated statistical frameworks to discriminate between competing hypotheses:

Bayesian Stochastic Search Variable Selection (BSSVS): Identifies the most parsimonious description of diffusion processes by allowing exchange rates in the Markov model to be zero with some probability, effectively testing which migration routes are statistically supported [10].

Ancestral range reconstruction: Uses likelihood-based methods to estimate historical geographic distributions while accounting for phylogenetic uncertainty, enabling tests of vicariance versus dispersal scenarios [18] [10].

Niche similarity tests: Quantifies whether observed niche differences between taxa or populations exceed null expectations, testing ecological divergence hypotheses [11] [15].

Total-Evidence Dating and Fossil Integration

The integration of fossil evidence provides critical temporal context for diversification events:

Fossilized Birth-Death (FBD) models: Incorporate fossil information directly as ancestral samples in the phylogeny, providing more accurate estimates of divergence times and speciation rates [18].

Morphological clock models: Apply relaxed clock models to morphological character evolution, enabling fossils to inform divergence time estimation even without molecular data [18].

Paleobiogeographic inference: Uses fossil distributions to constrain ancestral range estimations, revealing biogeographic patterns not apparent from extant taxa alone [18].

The following diagram illustrates the total-evidence phylogenetic approach that combines molecular and morphological data:

Geographic and ecological forces interact in complex ways to drive species diversification, with mountains, climatic shifts, and dispersal barriers creating the template upon which evolutionary processes unfold. The evidence from multiple study systems reveals recurring patterns:

The combined effects of habitat fragmentation and ecological divergence represent a common phenomenon in mountainous regions, with allopatric isolation and adaptive divergence to different elevation zones acting synergistically [11].

Historical contingency plays a critical role, with ancient geological events setting the stage for more recent diversification, as seen in the Sino-Himalayan region where Miocene orogeny created conditions for Pleistocene speciation [11] [12].

Comparative approaches across multiple taxa and mountain systems reveal both general principles and system-specific idiosyncrasies, highlighting the importance of replicated studies across diverse organisms [11] [15] [12].

Methodological advances in DNA sequencing, Bayesian inference, and ecological modeling continue to enhance our ability to discriminate between alternative diversification scenarios, providing increasingly sophisticated tools for unraveling the complex interplay of geographic and ecological forces in generating biological diversity.

Phylogeography examines the historical processes that have shaped the geographic distribution of genetic lineages, with a particular focus on the influence of Quaternary ice ages on patterns of speciation and genetic divergence. A central paradigm in this field is that glacial cycles acted as engines of diversification, repeatedly isolating populations into refugia and facilitating genetic divergence. This case study synthesizes findings from multiple research on boreal-breeding migratory birds to explore the concordant genetic patterns observed across species, specifically between populations associated with the Appalachian region and the broader boreal forests of North America. We examine how the interplay between historical climate fluctuations, migratory behavior, and demographic history has produced a recognizable phylogeographic signal, providing a model system for understanding the general principles of species diversification.

Analytical Framework: Key Concepts and Terminology

To interpret the patterns of genetic divergence in migratory birds, a clear understanding of the following core concepts is essential.

Table 1: Core Phylogeographic Concepts and Definitions

| Concept/Term | Definition | Relevance to Appalachian-Boreal Divergence |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogeography | The study of the historical processes that govern the geographic distribution of genealogical lineages. | Provides the overarching analytical framework for this case study. |

| Genetic Refugium | An area where a species can survive through periods of unfavorable climatic conditions, such as glaciations. | The Appalachian region is hypothesized to have served as a major refugium for boreal species. |

| Concordant Divergence | A pattern where multiple, co-distributed species show similar phylogenetic splits at approximately the same geographic barriers. | Supports the role of a common historical event (e.g., glaciation) in driving population isolation. |

| Migratory Syndrome | A suite of co-adapted traits related to migration, including physiology, morphology, and behavior. | Influences dispersal capability, gene flow, and subsequent genetic structure. |

| Philopatry | The tendency of an individual to return to or stay in its natal area to breed. | High natal philopatry in migrants can restrict gene flow, promoting genetic structure. |

| Demographic Stability | The maintenance of a relatively constant population size over time, avoiding severe bottlenecks. | Linked to the preservation of genetic diversity; a proposed benefit of long-distance migration. |

Comparative Phylogeographic Patterns in Boreal Birds

Evidence from numerous studies reveals that boreal birds exhibit predictable genetic splits, many of which correspond to historical glacial refugia. The following examples illustrate the depth and timing of these divergences.

Table 2: Documented Phylogeographic Divergences in Boreal and Migratory Birds

| Species/Group | Observed Genetic Divergence | Estimated Time of Divergence | Inferred Biogeographic Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arctic Warbler (Phylloscopus borealis) | Three distinct mitochondrial clades: A (Alaska/mainland Eurasia), B (Kamchatka/Sakhalin/Hokkaido), C (Honshu, Japan) [20]. | A/B vs. C: Pliocene-Pleistocene border (~2.5-3.0 MYA); A vs. B: Early-Mid Pleistocene (~1.9-2.3 MYA) [20]. | Survival in multiple unglaciated refugia in the Eastern Palearctic, contrasting with younger divergences in glaciated North America [20]. |

| Black-throated Blue Warbler (Dendroica caerulescens) | Shallow genetic divergence between northern and southern populations, despite differences in plumage and migratory route [21]. | Very recent, post-Pleistocene. Coalescent models indicate a recent common ancestor and no population split [21]. | Recent range expansion from a single refugium, with contemporary adaptive differences (migration, plumage) evolving rapidly. |

| Bee Hummingbirds (Mellisugini) | Multiple independent gains of migratory behavior within the tribe, facilitating the colonization of North America [22]. | Mid-to-late Miocene origin; most crown ages in the early Pliocene, with species splits in the Pleistocene [22]. | Evolution of migration was critical for the North American radiation, with transitions from sedentary to migratory populations. |

| General Boreal-Breeding Birds (35 species comparison) | Longer migration distance is strongly positively correlated with higher genetic diversity within species [23]. | Contemporary/ongoing process. | Long-distance migration to more stable tropical winters promotes demographic stability, preserving genetic diversity. |

A key visualization of the conceptual framework that integrates these findings is presented below.

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

The concordant patterns of divergence are revealed through a suite of sophisticated molecular and analytical techniques. This section details the core protocols used in the studies cited.

Mitochondrial DNA Phylogeography

This classic approach was used in the Arctic Warbler study to uncover deep genetic clades [20].

- Objective: To reconstruct deep phylogenetic splits and estimate divergence times among major geographic populations.

- Sample Collection: Tissue samples (e.g., blood, feathers) are collected from individuals across the species' breeding range. For example, the Arctic Warbler study used 113 individuals from 18 populations [20].

- DNA Extraction and Amplification: Genomic DNA is extracted using standard kits (e.g., Roche High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit). The target gene, typically the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene, is amplified using the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) with gene-specific primers [20] [24].

- Sequencing and Haplotype Identification: The amplified PCR products are sequenced, and the resulting sequences are aligned. Unique haplotypes are identified, and a haplotype network or phylogenetic tree is constructed using methods like Maximum Likelihood or Bayesian Inference (e.g., with software like BEAST or MrBayes) [20].

- Divergence Time Estimation: The phylogenetic tree is time-calibrated using either a fixed molecular clock rate (e.g., 2.1% sequence divergence per million years for cytochrome b) or a relaxed clock model in a Bayesian framework to estimate the timing of splits between clades [20].

- Demographic Analysis: Statistics like haplotype diversity (h) and nucleotide diversity (π) are calculated. Mismatch distributions and tests like Tajima's D are used to infer past population expansions or bottlenecks [20].

Comparative Population Genomics

This modern approach, as applied to 35 boreal bird species, uses genome-wide data to test evolutionary hypotheses [23].

- Objective: To compare population genetic structure and diversity across multiple, co-distributed species to identify common drivers.

- Whole Genome Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing is performed on numerous individuals (e.g., ~1,700 genomes across 35 species) to discover thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [23].

- Genetic Diversity Calculation: Genome-wide heterozygosity is calculated for each species as a measure of genetic diversity.

- Population Structure Analysis: Methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and ADMIXTURE are used to determine if individuals cluster by geographic origin, indicating genetic structure. A key finding is that most long-distance migrants exhibit significant spatial genetic structure despite their mobility [23].

- Correlative Modeling: Statistical models (e.g., phylogenetic generalized least squares) are used to test for a correlation between life-history traits (like migration distance) and genetic metrics (like diversity and structure), while controlling for shared evolutionary history [23].

Candidate Gene Analysis

This method tests the association between specific genes and migratory phenotypes, though with mixed success at broad phylogenetic scales.

- Objective: To determine if genetic variation in specific "candidate genes" is associated with migratory behavior across bird species.

- Gene Selection: Candidate genes are selected from the literature based on their known or hypothesized roles in related traits (e.g., CLOCK and ADCYAP1 for circadian rhythms and migration). One study analyzed 25 such candidate genes [25].

- Data Extraction: Genomic sequences for these genes are extracted from publicly available whole-genome assemblies for many species (e.g., 70 species across all bird orders) [25].

- Sequence Alignment and Phylogeny: Sequences for each gene are aligned across species, and gene trees are constructed.

- Testing for Association: The resulting gene trees are compared to the species tree to see if migratory species group together irrespective of their phylogeny. One major study found no genetic variants in candidate genes that consistently distinguished migrants from non-migrants, with any pattern being explained by phylogenetic relatedness alone [25]. This suggests the genetic basis of migration is complex and not reducible to a few universal genes.

The workflow for generating and analyzing the genetic data central to these findings is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Analytical Tools

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Phylogeographic Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Mist nets (e.g., Ecotone 1016 series), banding supplies, sterile capillary tubes for blood, ethanol for tissue preservation. | Safe and ethical capture of wild birds and preservation of genetic material for long-term storage [24]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Roche High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit, Invitrogen PureLink Genomic DNA Kit. | Isolation of high-quality, PCR-ready genomic DNA from small quantities of blood or tissue [24]. |

| PCR Reagents | Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, primers (e.g., Bird F1/R1 for COI barcoding), thermocycler. | Targeted amplification of specific genetic loci (e.g., mitochondrial cytochrome b, COI) for Sanger sequencing [24]. |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq for whole-genome sequencing; Applied Biosystems sequencers for Sanger sequencing. | Generation of high-throughput genome-wide SNP data or precise sequence data for individual genes [23]. |

| Bioinformatic Software | BEAST/MrBayes (phylogenetic inference), ADMIXTURE/STRUCTURE (population structure), PLINK (genotype analysis), R (statistical computing and graphics). | For analyzing genetic sequences, inferring population history, estimating divergence times, and visualizing genetic structure [20] [23]. |

| Reference Databases | Barcode of Life Database (BOLD), GenBank, BirdTree. | For comparing newly generated sequences to a global repository to identify haplotypes and place results in a broader phylogenetic context [24]. |

Synthesis and Implications for Species Diversification

The concordant Appalachian-Boreal genetic divergence observed across many migratory bird species provides a powerful illustration of how historical climate dynamics interact with species-specific ecology to shape biodiversity. The evidence suggests that Pleistocene glaciations were a primary driver, repeatedly isolating populations in refugia like the Appalachians. However, the subsequent evolutionary trajectories were heavily influenced by the evolution of migratory behavior. Migration facilitated the recolonization of deglaciated territories but, paradoxically, strong natal philopatry in migrants can maintain genetic structure by limiting dispersal between breeding populations [23].

A striking finding from recent comparative genomics is the strong positive correlation between migration distance and genetic diversity [23]. This challenges simpler models and suggests that the primary impact of long-distance migration on genetic evolution may be through the promotion of demographic stability. By wintering in more stable tropical latitudes, long-distance migrants may experience less severe population fluctuations, thereby preserving genetic diversity more effectively than short-distance migrants that winter in more volatile higher-latitude environments. This underscores that life-history strategies can profoundly influence the retention of genetic variation.

Finally, the repeated, independent evolution of migration across different bird lineages—from hummingbirds to warblers—highlights its role as a key innovation that opens new ecological and evolutionary pathways [22]. The failure of candidate gene approaches to find a universal genetic signature for migration [25] further emphasizes that migration is a complex, polygenic trait whose genetic architecture can be uniquely solved in different lineages. In conclusion, the concordant phylogeographic patterns in boreal birds are not the product of a single mechanism, but rather the emergent property of vicariant events, behavioral adaptations, and demographic processes acting in concert over millennia.

Arid Central Asia (ACA) represents the largest mid-latitude arid and semi-arid zone on Earth and has experienced a highly dynamic climate history, including stepwise aridification and complex tectonic activity [26] [27]. This region provides an exceptional experimental setting for investigating how geography and past climate changes have shaped genetic structure and lineage diversification in desert-adapted species [28] [27]. Phylogeographic studies of widespread lizard species reveal consistent patterns of deep genetic divergence associated with mountain ranges, basins, and other topographic features, coupled with demographic responses to Quaternary climatic oscillations [28] [26]. Understanding these synergistic effects is crucial for predicting species responses to ongoing environmental change and for conserving biodiversity in fragile arid ecosystems.

This case study examines the phylogeographic patterns in two widespread lizard genera – Eremias and Phrynocephalus – to elucidate how topography and climate dynamics have synergistically driven diversification in ACA's arid biota. The findings presented herein contribute to a broader thesis on phylogeography and species diversification patterns by demonstrating how historical biogeographic processes repeat across disparate taxa in response to shared environmental drivers.

Material and Methods

Study Systems and Sampling Strategies

Central Asian Racerunner (Eremias vermiculata): This study analyzed 876 individuals from 113 localities across ACA. Mitochondrial DNA sequences were obtained from all individuals, while three nuclear genes (CGNL1, MAP1A, and β-fibint7) were sequenced from subsets of 204, 170, and 138 individuals, respectively [28]. The extensive sampling across the species' range enabled comprehensive assessment of genetic diversity and population structure.

Sunwatcher Toad-headed Agama (Phrynocephalus helioscopus): Researchers collected 300 individuals from 96 sampling sites, with mitochondrial data supplemented from previous studies [26] [27]. For genomic analysis, 51 individuals from 27 localities were selected for genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) to generate genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data [26].

Molecular Methodologies

Table 1: Molecular Markers and Analytical Approaches in Arid Lizard Phylogeography

| Study System | Molecular Markers | Sequencing Methods | Phylogenetic Analyses | Divergence Dating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eremias vermiculata | Mitochondrial DNA; Nuclear genes: CGNL1, MAP1A, β-fibint7 | Sanger sequencing | Maximum Likelihood, Bayesian Inference | Bayesian relaxed clock models with fossil calibrations |

| Phrynocephalus helioscopus | Mitochondrial genes: CO1, ND2; Genome-wide SNPs | Sanger sequencing + Genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) | Coalescent-based species trees, Phylogenetic networks | Multispecies coalescent dating with mutation rate priors |

Ecological Niche Modeling and Statistical Analyses

Ecological niche modeling (ENM) was employed in both study systems to reconstruct past potential distributions and identify climate stability areas. Researchers used MaxEnt or similar algorithms with current occurrence records and paleoclimatic data from the Last Interglacial (LIG), Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), and mid-Holocene periods [28] [26]. Statistical analyses included:

- Population structure analysis: Using STRUCTURE, PCA, and DAPC for genetic clustering

- Demographic history reconstruction: Employing Bayesian skyline plots and extended Bayesian skyline analysis

- Testing isolation-by-distance vs. isolation-by-environment: Applying Mantel tests and redundancy analysis (RDA)

- Ancestral area reconstruction: Utilizing biogeographic models in BioGeoBEARS [26] [27]

Figure 1: Phylogeographic Workflow for Arid Lizard Diversification Studies

Key Findings

Lineage Diversification Patterns

Table 2: Lineage Diversification Characteristics in ACA Lizard Species

| Study System | Genetic Lineages | Divergence Times | Key Geographic Barriers | Mito-nuclear Discordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eremias vermiculata | 4 major mtDNA lineages | ~1.18 million years ago | Tarim Basin topography, mountain ranges | Present, indicating complex evolutionary dynamics |

| Phrynocephalus helioscopus | 8 geographically correlated mtDNA lineages | ~4.47 million years ago (crown age) | Amu Darya River, Zeravshan River, Hissar-Alay uplift | Present in Clade V (P. h. sergeevi) |

Both study systems revealed strong phylogeographic structure corresponding with specific geographic features. In E. vermiculata, the four major mitochondrial lineages showed distinct geographic distributions reflecting the topographic and ecological heterogeneity of ACA [28]. Similarly, P. helioscopus exhibited eight geographically correlated lineages, with ancestral area estimations suggesting an origin in the Fergana Valley followed by dispersal and multiple allopatric divergence events [26] [27].

The initial diversification in E. vermiculata coincided with major tectonic activity and climatic aridification around 1.18 million years ago, promoting allopatric divergence [28]. For P. helioscopus, the intensification of aridification across Central Asia during the Late Pliocene facilitated rapid radiation, with subsequent Pleistocene geologic events triggering progressive diversification [26].

Topographic Influences on Genetic Structure

Mountain ranges and basins functioned as significant drivers of genetic divergence in both lizard groups. In E. vermiculata, lineage diversification within the Tarim Basin suggested that recent environmental shifts promoted genetic divergence [28]. The complex orogenic history and structure of Central Asia created multiple barriers to gene flow, with uplift events such as the Hissar-Alay directly triggering divergence in P. helioscopus [26].

Rivers also served as important biogeographic barriers, with the Amu Darya and Zeravshan Rivers delimiting lineages in P. helioscopus [26]. Similarly, local-scale genetic differentiation in the Ili River Valley and Junggar Basin revealed additional geographic barriers to dispersal [26].

Climate-Driven Demographic Responses

Demographic reconstructions revealed contrasting responses to Pleistocene climate fluctuations. In E. vermiculata, all lineages showed signatures of population expansion or range shifts during the Last Glacial Maximum [28]. P. helioscopus exhibited lineage-specific responses, with Clade VIII (P. h. varius) experiencing rapid population growth coupled with range expansion, while Clade IV (P. h. cameranoi) underwent drastic population expansion associated with range contraction during the LGM [26].

Environmental turnover contributed more to mitochondrial genetic distinctiveness than geographic distance in Clade IV of P. helioscopus, though genome-wide SNPs demonstrated that geographic distance generally played a greater role than environmental distance [26]. This highlights the importance of multi-locus approaches for accurate inference of evolutionary history.

Technical Protocols

Mitochondrial DNA Sequencing Protocol

DNA Extraction and Quantification:

- Tissue samples preserved in silica gel or ethanol

- Extraction using commercial kits (e.g., Plant Genomic DNA Kit DP305)

- Quality assessment via spectrophotometry and gel electrophoresis

PCR Amplification:

- Primers targeting specific mtDNA genes (CO1, ND2, etc.)

- Reaction mix: 10-50 ng template DNA, 10 μM each primer, dNTPs, reaction buffer, Taq polymerase

- Thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 50-60°C for 45s, 72°C for 90s; final extension at 72°C for 10 min

Sequencing and Alignment:

- Purification of PCR products

- Sanger sequencing in both directions

- Sequence alignment using MAFFT or MUSCLE

- Haplotype identification and network construction

Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) Protocol

Library Preparation:

- Genomic DNA digestion with restriction enzymes (e.g., EcoRI, MseI)

- Ligation of barcoded adapters

- Pooling of samples and size selection

- PCR amplification with indexing primers

Sequencing and SNP Calling:

- High-throughput sequencing on Illumina platforms

- Quality control with FastQC

- Demultiplexing and read alignment to reference genome

- SNP calling using GATK or STACKS pipeline

- Filtering for missing data, minor allele frequency, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

Ecological Niche Modeling Protocol

Data Collection:

- Species occurrence records from field sampling and museum collections

- Environmental variables from WorldClim and other databases

- Paleoclimatic data for historical period reconstructions

Model Implementation:

- Correlation analysis to reduce variable collinearity

- Model calibration using current climate data

- Projection to paleoclimatic scenarios

- Model evaluation using AUC and partial ROC metrics

Figure 2: Synergistic Effects of Topography and Climate on Lizard Diversification

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Phylogeographic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Examples | Application in Phylogeography |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Plant Genomic DNA Kit DP305, DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | High-quality DNA extraction from various tissue types |

| Restriction Enzymes | EcoRI-HF, NsiI-HF, MseI | Genotyping-by-sequencing library preparation |

| PCR Reagents | Taq polymerase, dNTPs, buffer systems | Amplification of specific gene regions |

| Sequencing Kits | BigDye Terminator v3.1, Illumina sequencing kits | Sanger and next-generation sequencing |

| Bioinformatics Tools | MITObim, GATK, STACKS, STRUCTURE | Data processing, SNP calling, population structure analysis |

Discussion

Synthesis of Topographic and Climatic Synergies

The synergistic effects of topography and climate dynamics emerge as a central theme driving lizard diversification in Arid Central Asia. Topographic complexity creates the template for diversification by forming physical barriers to gene flow, while climatic oscillations create the timing mechanisms that initiate divergence through range fluctuations and population isolation [28] [26]. This synergy explains the profound phylogeographic structure observed across multiple lizard taxa in ACA despite their ecological differences.

The finding of mito-nuclear discordance in both E. vermiculata and P. helioscopus indicates complex evolutionary dynamics that cannot be explained by simple allopatric models [28] [26]. This discordance may result from sex-biased dispersal, adaptive introgression, or differing evolutionary rates between mitochondrial and nuclear genomes. Future studies employing whole-genome sequencing will be essential for clarifying the mechanisms underlying these patterns.

Implications for Phylogeographic Theory

These case studies contribute significantly to phylogeographic theory by demonstrating how general principles of diversification manifest in aridland environments. The patterns observed mirror those found in other biomes, including sky island systems where topographic complexity similarly promotes lineage diversification [29] [30]. However, the specific drivers in ACA – particularly the dominance of aridification cycles rather than temperature fluctuations – represent distinctive evolutionary selective pressures.

The contrasting demographic responses observed between lineages highlight the importance of species-specific and lineage-specific factors in shaping evolutionary trajectories. While some lineages expanded during glacial periods, others contracted, reflecting differential habitat requirements and physiological tolerances [28] [26]. This complexity underscores the limitation of simple phylogeographic models and supports the development of more nuanced, individual-based approaches.

Conservation Implications and Future Directions

The deep genetic diversification and local endemism revealed in these studies have significant conservation implications. Many of the identified lineages have restricted distributions in topographically complex areas, making them particularly vulnerable to habitat loss and climate change [28] [31]. Conservation planning should prioritize these areas of high phylogenetic diversity and consider evolutionarily significant units in management strategies.

Future research should integrate genomic, ecological, and environmental data to further elucidate the mechanisms of diversification. Specifically, studies identifying genes under selection and their association with environmental variables will enhance our understanding of local adaptation in these heterogeneous landscapes [26]. Additionally, expanding these approaches to other aridland taxa will help determine the generality of the patterns observed in ACA lizards.

The refugia hypothesis and the role of contemporary demographic processes present contrasting frameworks for interpreting genetic diversity and population structure. While the refugia hypothesis has long served as a paradigm for explaining patterns of speciation and endemism, particularly in tropical regions, advanced genomic techniques and sophisticated modeling approaches now reveal a more complex interplay of historical isolation and ongoing demographic expansion. This review synthesizes current understanding of how these competing mechanisms shape genetic architecture, highlighting methodological advances that enable researchers to disentangle their effects. We provide a comprehensive overview of experimental protocols, quantitative comparisons, and visualization tools essential for investigating these evolutionary drivers, with particular relevance for biogeography, conservation genetics, and pharmacogenomics.

The spatial distribution of biodiversity represents one of the most enduring puzzles in evolutionary biology. For decades, the refugia hypothesis—which posits that climatic oscillations during the Pleistocene fragmented formerly continuous habitats into isolated refugia, promoting allopatric speciation—has dominated explanations for high species diversity in regions like the Amazon basin [32]. This concept has proven exceptionally influential across multiple disciplines, from biogeography to anthropology [5].

However, the paradigm has increasingly been challenged by evidence suggesting that contemporary demographic processes, including post-glacial range expansion and ongoing gene flow, may equally explain observed genetic patterns [33]. The central controversy lies in distinguishing whether current genetic structure primarily reflects deep historical isolation or more recent population dynamics—a distinction with profound implications for predicting species responses to environmental change and for understanding the genetic basis of variable drug responses in human populations [34] [35].

This review examines the contrasting predictions of these frameworks, synthesizing evidence from diverse taxonomic groups and outlining the methodological approaches required to test their relative contributions to genetic diversity.

Theoretical Foundations and Contrasting Predictions

The Refugia Hypothesis: Core Principles and Genetic Legacy

In biological terms, a refugium (plural: refugia) represents a location that supports an isolated or relict population of a once more widespread species, often resulting from climatic changes, geographical barriers, or human activities [5]. The concept was notably applied by Jürgen Haffer to explain Amazonian bird diversity, proposing that during dry glacial periods, the extensive forest fragmented into smaller, isolated patches, creating "refuge areas" where populations diverged in allopatry [32] [5].

The refugia hypothesis makes several specific genetic predictions:

- Deep genetic divisions between populations corresponding to historical refuge boundaries

- Higher genetic diversity within putative refugia due to longer population persistence

- Distinct phylogenetic lineages confined to different refuge areas

- Signatures of population stability in refuge areas versus expansion in newly colonized regions

Evidence supporting this model exists across multiple taxa. For example, phylogeographic studies of central African duikers revealed distinct mitochondrial lineages in the Gulf of Guinea refugium, consistent with long-term isolation [36]. Similarly, the Red Knobby Newt in southwestern China exhibits four maternal phylogenetic lineages corresponding to separate Pleistocene refugia [37].

Contemporary Demography: Range Expansion and Genetic Drift

In contrast, models emphasizing contemporary demography highlight how recent population history—including range expansions, serial founder events, and genetic drift—can shape genetic architecture without requiring deep historical isolation [33]. This perspective argues that current genetic structure may primarily reflect post-glacial colonization patterns rather than vicariant events.

Key genetic predictions include:

- Spatial sorting of alleles along expansion routes

- Decreasing genetic diversity with increasing distance from the source population

- Signatures of population expansion in demographic analyses

- Weak correlation between genetic divisions and putative historical barriers

Research on the painted turtle exemplifies this pattern. Spatially-explicit coalescent simulations demonstrated that genetic diversity in this species was most consistent with expansion from a single refugium rather than multiple allopatric refugia, indicating a stronger role for post-glacial range expansion than for isolation in shaping diversity [33].

Table 1: Contrasting Predictions of Refugia vs. Contemporary Demography Models

| Genetic Characteristic | Refugia Hypothesis Predictions | Contemporary Demography Predictions |

|---|---|---|

| Population Structure | Strong divisions corresponding to refuge boundaries | Clinal variation along expansion routes |

| Genetic Diversity | Higher within refugia | Decreasing with distance from source |

| Phylogenetic Pattern | Deep divergences between refugia | Shallow divergences with spatial sorting |

| Demographic History | Stability within refugia, expansion afterward | Signals of recent expansion across range |

| Lineage-Geography Correlation | High | Variable to low |

Methodological Framework for Discrimination

Integrated Phylogenetic and Population Genetic Approaches

Disentangling the effects of refugial isolation from contemporary demography requires sophisticated methodological approaches that combine phylogeographic analysis, demographic modeling, and landscape genetics.

Multilocus DNA sequencing provides the fundamental data for these analyses, with mitochondrial markers offering insights into deep demographic history and nuclear markers reflecting more recent processes [38] [37]. For instance, studies on Synoeca social wasps utilized sequences from both mitochondrial (16S, 12S, COI, COII, CytB) and nuclear (CAD, EF1α) loci to reveal idiosyncratic phylogeographic patterns reflecting different historical processes [38].

Microsatellite genotyping offers higher resolution for contemporary gene flow and population structure analysis. Research on central African duikers employed 12 polymorphic microsatellite loci to assess modern genetic differentiation patterns across environmental gradients [36]. Quality control steps for such analyses include testing for null alleles, linkage disequilibrium, and deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium using tools like MICROCHECKER and GENALEX [33].

Ecological Niche Modeling and Paleodistribution Reconstruction

Ecological Niche Models projected onto historical climate scenarios enable researchers to identify potential refugia and test hypotheses about past distributional changes. The standard protocol involves:

- Compiling contemporary occurrence records

- Extracting bioclimatic variables for occurrence localities

- Building a model relating current distribution to climate

- Projecting the model onto paleoclimate reconstructions

- Identifying stable areas potentially serving as refugia

In painted turtle research, present-day ENMs hindcast to historical climate reconstructions defined scenarios with one, two, or three potential refugia, which were then tested against genetic data [33]. Similarly, studies on the Red Knobby Newt used paleodistribution modeling to identify four separate refugia in southern Yunnan during previous glacial periods [37].

Spatially-Explicit Coalescent Simulation and Model Testing

Approximate Bayesian Computation within a spatially-explicit coalescent framework represents a powerful approach for testing alternative historical scenarios [33]. This method allows researchers to:

- Simulate genetic data under competing demographic models

- Compare empirical data with simulations

- Calculate the relative likelihood of different scenarios

- Estimate demographic parameters under the best-supported model

This approach was effectively used to demonstrate that painted turtle genetics were most consistent with expansion from a single refugium rather than multiple allopatric refugia [33].

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Discriminating Evolutionary Scenarios

| Method | Primary Application | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multilocus Phylogenetics | Deep historical inference | Temporal depth | Limited resolution for recent events |

| Microsatellite Genotyping | Contemporary gene flow | High polymorphism | Limited genomic context |

| Ecological Niche Modeling | Paleodistribution reconstruction | Spatially explicit | Assumes niche conservatism |

| Approximate Bayesian Computation | Model testing & parameter estimation | Compares complex scenarios | Computationally intensive |

| Generalized Dissimilarity Modeling | Landscape genetics | Identifies environmental drivers | Correlation not causation |

Experimental Workflow for Hypothesis Testing

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for testing refugia versus contemporary demographic hypotheses:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for discriminating between refugial isolation and contemporary demographic hypotheses.

Case Studies and Empirical Evidence

Neotropical Diversification: Beyond the Amazonian Paradigm

The Amazon basin has served as the classic setting for testing the refugia hypothesis. While initial studies strongly supported the model for birds, lizards, butterflies, and plants [32], more recent investigations reveal a more complex picture. Research on Synoeca social wasps in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest demonstrated idiosyncratic patterns between mid-montane and lowland species, indicating that neotectonics and refugia played distinct roles in their diversification [38]. This highlights that a single dominant explanation cannot adequately explain diversification within this region.

Temperate Zone Phylogeography: Painted Turtle Dynamics

The painted turtle study provides a compelling example where contemporary demographic processes outweigh refugial effects. Using mitochondrial and microsatellite data coupled with spatially-explicit coalescent simulations, researchers found that genetic patterns were most consistent with expansion from a single refugium [33]. This suggests that post-glacial range expansion, rather than isolation in multiple allopatric refugia, played the dominant role in structuring diversity in this widely distributed species.

African Forest Refugia: Duiker Diversification Patterns

Central African duikers illustrate how both historical and contemporary processes interact to shape genetic diversity. Mitochondrial analyses revealed distinct lineages in the Gulf of Guinea refugium, consistent with Pleistocene isolation [36]. However, generalized dissimilarity models showed that environmental variation explains most contemporary nuclear genetic differentiation, with the forest-savanna transition in central Cameroon showing the highest environmentally-associated genetic turnover [36]. This demonstrates the importance of considering both historical and ongoing processes.

Implications for Human Genetic Diversity and Pharmacogenomics

The concepts of refugia and contemporary demography extend to human genetics, with profound implications for pharmacogenomics. Population differences in drug response are affected by genetic polymorphisms whose frequencies differ among ethnicities, potentially due to historical population dynamics and isolation [34]. Recent analyses of the ExAC dataset comprising 60,706 human exomes reveal that most functional variants in drug-related genes are rare (frequency <0.1%), creating differential drug response risks across populations with different demographic histories [35].

Table 3: Comparative Population Genetics Across Case Studies

| Study System | Genetic Markers | Primary Historical Process | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amazonian Birds [32] | Allozymes, mtDNA | Multiple Pleistocene refugia | Deep divergences concordant with proposed refugia |

| Painted Turtle [33] | mtDNA, microsatellites | Single refugium with expansion | Coalescent simulations favor single source |

| African Duikers [36] | mtDNA, microsatellites | Combined refugia and environmental adaptation | Mitochondrial divergences in refugia; nuclear structure follows environment |

| Human Drug Response [35] | Exome sequences | Complex demographic history | Population-differentiated SNPs affect drug metabolism |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Analytical Solutions

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Example | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | DNA extraction from various samples | Standardized extraction from duiker feces [36] | Critical for non-invasive sampling |

| Mitochondrial Primers | Amplifying conserved mtDNA regions | Phylogeography of social wasps [38] | Variable resolution across taxa |

| Microsatellite Panels | Genotyping hypervariable loci | Population structure in painted turtles [33] | Require species-specific optimization |

| PharmGKB Database | Curated drug-gene interactions | Warfarin response pathway analysis [34] | Essential for pharmacogenomic applications |

| ExAC Database | Catalog of human coding variation | Assessing functional variants in drug targets [35] | Powerful for rare variant discovery |

| MAXENT Software | Ecological niche modeling | Paleodistribution modeling [33] [36] | Standard for species distribution modeling |

| DIYABC Software | Approximate Bayesian Computation | Testing refugial scenarios [33] | User-friendly for complex demographic modeling |

The dichotomy between refugia and contemporary demography represents a false dichotomy; emerging evidence increasingly reveals their interactive effects on genetic diversity. While the refugia hypothesis alone cannot explain the diversification of complex species assemblages [32], it remains valuable for understanding deep phylogenetic structure. Contemporary demographic processes better explain patterns of population expansion and ecological adaptation [33] [36].

Future research should prioritize comparative phylogeographic approaches across co-distributed species with differing ecological characteristics, whole-genome sequencing to capture both coding and regulatory variation, and improved paleoclimate reconstructions for more accurate hindcasting of species distributions. Furthermore, integrating these evolutionary perspectives into pharmacogenomics will enhance our ability to predict population-specific drug responses and adverse reactions [34] [35].

The methodological framework outlined here—combining multilocus genetic data, ecological niche modeling, and statistically rigorous model testing—provides a powerful approach for discriminating between historical and contemporary influences on genetic diversity. As these techniques continue to refine our understanding of diversification processes, they will increasingly inform conservation prioritization, pharmaceutical development, and our fundamental knowledge of evolutionary mechanisms.

Advanced Genomic and Modeling Techniques for Phylogeographic Analysis

Whole-Genome Sequencing for High-Resolution Population Genomics

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) represents a transformative technology that enables researchers to decipher the complete DNA sequence of an organism's genome, providing an unprecedented view of genetic variation within and between populations. In the context of phylogeography and species diversification, WGS has emerged as a crucial methodological foundation, allowing scientists to test hypotheses about evolutionary dynamics, demographic history, and the genetic consequences of historical environmental changes. By sequencing the entire genome of multiple individuals within a species using a known reference genome sequence, researchers can identify various genetic variants including Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), Structural Variations (SVs), Insertions and Deletions (InDels), and Copy Number Variations (CNVs) [39]. This comprehensive genetic data facilitates in-depth exploration of population genetic architecture, enabling the reconstruction of historical population trajectories and the dynamic processes involved in population evolution [40].

The application of WGS in population genomics has been particularly instrumental in resolving complex phylogenetic relationships that have proven difficult to decipher using traditional markers. As demonstrated in cervid phylogenetics, genome-wide SNP data from reduced-representation genome sequencing can robustly separate species into statistically well-supported clades, providing clarity to taxonomic relationships that remained contentious based on morphology, karyotypes, or limited molecular markers alone [41]. The higher resolution afforded by WGS allows researchers to move beyond broad phylogenetic patterns to investigate fine-scale population processes, including gene flow, local adaptation, and demographic fluctuations that have shaped contemporary genetic diversity.

Technical Foundations of Whole-Genome Sequencing

Sequencing Technologies and Methodological Approaches

The evolution of sequencing technologies has progressively enhanced our ability to generate comprehensive genomic data for population studies. First-generation Sanger sequencing offered high accuracy but was limited by low throughput and relatively high costs [39]. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, notably the Illumina platform, revolutionized population genomics through massive parallel sequencing, generating large volumes of data cost-effectively [39]. More recently, third-generation sequencing (TGS) technologies, including single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), provide ultra-long read lengths that more accurately resolve highly repetitive genomic regions and offer improved haplotype construction [39].

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Technology Generations

| Technology Generation | Key Platforms | Advantages | Limitations | Common Applications in Population Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Generation | Sanger sequencing | High accuracy, medium read lengths | Low throughput, high cost | Validation of variants, small-scale targeted sequencing |

| Second-Generation (NGS) | Illumina | High throughput, cost-effective, accurate | Short read lengths | Whole-genome resequencing, variant discovery, population-scale studies |

| Third-Generation (TGS) | PacBio, ONT | Ultra-long reads, direct RNA sequencing | Higher error rates, higher cost | Genome assembly, structural variant discovery, haplotype phasing |

WGS approaches can be categorized based on sequencing depth and strategy. High-depth individual sequencing provides the highest quality data for variant identification but comes with substantial budgetary and data storage requirements. Low-coverage whole-genome sequencing (lcWGR) typically at depths below 1×, offers a cost-effective alternative for large-scale population studies, though it relies heavily on reference genomes for accurate genotyping [39]. Pool-seq involves sequencing DNA pools from multiple individuals, providing cost-effective polymorphism data while sacrificing individual genotype information and haplotype resolution [39].

Quality Control Parameters for WGS Data

The reliability of population genomic inferences depends critically on appropriate quality control throughout the WGS workflow. Several key metrics must be considered when designing and evaluating WGS studies:

- Sequencing depth: Denoted as "X," this refers to the average number of times each base in the genome is sequenced. Higher depth reduces false positives and increases variant calling accuracy, with depths of 10× often achieving effective genome coverage exceeding 99% in mammalian studies [39].

- Coverage: The proportion of the target genome sequenced at least once, expressed as a percentage. This metric reflects the completeness of genome interrogation, with higher coverage reducing the potential for missing biologically important variants [39].

- Mapping rate: The percentage of sequenced bases that successfully align to the reference genome. Higher mapping rates indicate better data quality and compatibility with the reference genome, while low rates may signal poor sample quality, reference genome issues, or problematic repetitive regions [39].

These parameters exhibit important interrelationships; sequencing depth and coverage are positively correlated, with diminishing returns beyond certain depth thresholds. Careful consideration of these metrics during experimental design is essential for balancing data quality with practical constraints in population genomic studies.

Analytical Frameworks for Population Genomic Inference

Core Analytical Methods in Population Genetics

The analysis of WGS data employs a diverse toolkit of statistical methods to infer population history, structure, and evolutionary processes. These methods leverage patterns of genetic variation to make inferences about past demographic events, selective pressures, and evolutionary relationships.

Table 2: Key Population Genetic Analysis Methods

| Method | Purpose | Key Outputs | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Dimensionality reduction for genetic data | Principal components visualizing genetic similarity | Clusters indicate genetically similar individuals; axes represent genetic gradients |

| Population Structure Analysis | Identify genetic subgroups and admixture | Ancestry proportions for individuals; optimal number of populations (K) | Reveals historical divergence and gene flow between populations |