Identifying Co-opted Networks: Methods and Models for Uncovering the Origins of Novel Traits and Diseases

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the methodologies for identifying co-opted gene networks—evolutionarily recycled developmental programs that give rise to novel complex traits...

Identifying Co-opted Networks: Methods and Models for Uncovering the Origins of Novel Traits and Diseases

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the methodologies for identifying co-opted gene networks—evolutionarily recycled developmental programs that give rise to novel complex traits and diseases. We explore foundational concepts like the CRE-DDC model and network interlocking, detail practical approaches from forward genetic screens to modern computational frameworks, and address key troubleshooting challenges in differentiating true co-option from similar phenomena. The content further covers validation strategies through single-cell transcriptomics and electronic health records, concluding with a comparative analysis of how these methods illuminate pathological processes in cancer and offer rapid screening for drug repurposing in emerging diseases.

The Principles of Network Co-option: From Evolutionary Novelties to Disease Mechanisms

Gene co-option (also termed gene recruitment) represents an evolutionary process where existing genes or genetic networks are employed for new biological functions, often in completely different developmental contexts [1]. This process serves as a fundamental mechanism for the evolution of novel traits without requiring the creation of new genetic material de novo [2]. Instead of designing new components from scratch, evolution acts as a 'tinkerer,' repurposing existing genetic toolkits [3] [1].

The molecular basis of co-option frequently involves changes in cis-regulatory elements (CREs) rather than alterations to the protein-coding sequences themselves [4] [1]. Mutations in regulatory regions can cause genes previously expressed in one tissue to be activated in new locations or developmental stages. If this new expression pattern confers an advantage, it can be selected and stabilized through natural selection [2] [3].

Quantitative Analysis of Co-option Events

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Identifying Gene Co-option

| Parameter | Measurement Approach | Interpretation | Example Experimental Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Conservation | RNA in situ hybridization, RNA-seq across tissues/species | Shared expression pattern in novel context indicates potential co-option [4] | Orthologous gene expression in fish cloaca vs. mouse digits [5] |

| Regulatory Landscape Conservation | ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, Hi-C | Same enhancers active in different organs [5] [4] | 5DOM landscape active in mouse digits and zebrafish cloaca [5] |

| Functional Requirement | Gene knockout/knockdown phenotypes | Same genes required for development of different structures [4] | enD enhancer deletion disrupts both spiracle and testis development [4] |

| CRE Sequence Conservation | Genomic alignment, motif analysis | Conserved non-coding elements suggest shared regulation [5] | TTGACT motif bound by PaSTM in S11 MYB promoters [6] |

| Genetic Network Topology | Correlation of expression patterns across multiple genes | Co-expression of network members in novel context [4] | 10-gene spiracle network active in male genitalia [4] |

Table 2: Experimental Readouts for Validating Co-option

| Experimental Manipulation | Expected Result if Co-option Occurred | Control Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Enhancer deletion (e.g., CRISPR) | Loss of function in both ancestral and novel contexts [5] [4] | Tissue-specific expression retained in other domains |

| Enhancer-reporter assay | Reporter expression in both ancestral and novel contexts [4] | Minimal background activity in other tissues |

| Cross-species complementation | Gene/network from one species functions in another [6] | Failure to complement in non-orthologous contexts |

| Cis-regulatory mutation | Disruption of one function while preserving the other [4] | Protein function remains intact |

| Network perturbation | Cascading effects across co-opted gene members [4] | Specific, not pleiotropic, effects observed |

Experimental Protocols for Identifying Co-opted Networks

Protocol: Comparative Expression Analysis Using Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH)

Application: Mapping spatial expression domains across species and tissues to identify potential co-option events [5] [4].

Materials:

- Fixed embryos/tissues from multiple species

- DIG-labeled RNA antisense probes

- Anti-DIG antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase

- NBT/BCIP staining solution

- PBS and PBST buffers

- Proteinase K

Methodology:

- Fixation: Collect and fix tissues in 4% PFA for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Permeabilization: Treat with 10μg/mL Proteinase K for 15 minutes.

- Hybridization: Incubate with gene-specific DIG-labeled probes overnight at 65°C.

- Washing: Stringent washes with SSC-based buffers to remove non-specific binding.

- Antibody Detection: Incubate with anti-DIG-AP antibody (1:5000 dilution) for 2 hours.

- Color Reaction: Develop with NBT/BCIP substrate until desired signal intensity.

- Documentation: Image specimens using stereomicroscope with consistent lighting.

Interpretation: Co-option is supported when expression patterns are shared between non-homologous structures (e.g., posterior spiracles and male genitalia in Drosophila) [4].

Protocol: Enhancer Deletion via CRISPR-Cas9

Application: Functional validation of regulatory landscapes implicated in co-option events [5].

Materials:

- CRISPR-Cas9 reagents (Cas9 protein, sgRNAs)

- Microinjection apparatus

- Embryos at single-cell stage

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR primers flanking target region

- Agarose gel electrophoresis system

Methodology:

- Target Design: Design two sgRNAs flanking the regulatory region of interest (e.g., 5DOM landscape).

- Microinjection: Co-inject Cas9 protein and sgRNAs into zebrafish/mouse embryos.

- Founder Screening: Raise injected embryos (F0) and screen for germline transmission.

- Line Establishment: Outcross F0 fish to establish stable mutant lines (e.g.,

hoxdadel(5DOM)). - Genotypic Validation: Confirm deletion by PCR and sequencing across the junction.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Assess expression changes via WISH and morphological defects.

Interpretation: In zebrafish, deletion of the 5DOM regulatory landscape abolished hoxd13a expression in the cloaca but not fins, revealing its ancestral function was cloacal, not appendage-related [5].

Protocol: Cross-Species Functional Complementation

Application: Testing whether orthologous genes can recapitulate co-opted functions across evolutionary distances [6].

Materials:

- Heterologous expression vector (e.g., 35S promoter)

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain

- Plant transformation materials

- Mutant lines (e.g., Arabidopsis

stm-2) - Tissue culture media and antibiotics

Methodology:

- Cloning: Clone candidate gene (e.g.,

PaSTM) into plant expression vector. - Transformation: Introduce construct into Agrobacterium and transform mutant plants.

- Selection: Select transgenic lines on antibiotic-containing media.

- Phenotypic Rescue: Assess complementation of mutant phenotype (e.g., SAM restoration in

stm-2). - Molecular Analysis: Confirm transgene expression via RT-PCR and protein analysis.

Interpretation: PaSTM from Phalaenopsis orchids restored shoot meristem function in Arabidopsis stm-2 mutants, demonstrating deep functional conservation of this regulatory gene [6].

Visualization of Co-option Concepts and Pathways

Co-option Evolutionary Pathway

Hox Regulatory Co-option in Tetrapods

Drosophila Gene Network Co-option

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Co-option Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, sgRNAs | Regulatory landscape deletion (e.g., 5DOM, 3DOM) [5] |

| Transgenic Systems | GAL4/UAS, CRE-lox, enD-lacZ reporter | Spatiotemporal control of gene expression [4] |

| Antibodies | Anti-Sal, Anti-Engrailed, Anti-En | Protein localization and expression analysis [4] |

| Molecular Cloning | Expression vectors, Gateway system | Cross-species complementation tests [6] |

| Staining Reagents | NBT/BCIP, DIG-labeled RNA probes | Whole-mount in situ hybridization [5] |

| Cell Culture | Plant tissue culture media, antibiotics | Protocorm-like body (PLB) regeneration [6] |

| Sequencing Tools | RNA-seq libraries, ChIP-seq kits | Transcriptome and epigenome profiling [5] |

The CRE-DDC Model (Co-option and Rewiring of Evolutionary - Developmental Gene Regulatory Networks for Drug Discovery and Complexity) provides a novel framework for identifying and validating co-opted biological networks in disease contexts. This model integrates evolutionary biology principles with quantitative functional genomics to accelerate therapeutic development, particularly for complex diseases where traditional target-discovery approaches have proven inadequate. By examining how existing gene networks are repurposed (co-opted) and reconfigured (rewired) throughout evolution, researchers can identify critical regulatory nodes amenable to pharmacological intervention. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding disease mechanisms that exploit conserved developmental pathways, such as oncogenic processes reactivating embryonic signaling networks or neurodegenerative diseases disrupting neuronal maintenance programs. The CRE-DDC model establishes a standardized methodology for quantifying network co-option events and their functional consequences, providing a systematic approach to identifying druggable targets within repurposed biological systems.

Theoretical Framework and Core Principles

The CRE-DDC model operates on several foundational principles derived from evolutionary developmental biology and systems pharmacology. First, it posits that biological innovation often arises not through the evolution of entirely new genes, but through the co-option and rewiring of existing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) for new functions [7]. This repurposing occurs when ancestral gene networks are deployed in new temporal, spatial, or functional contexts, creating novel phenotypes without fundamentally altering the core network architecture. Second, the model emphasizes that network fragility increases at points of evolutionary rewiring, making these interfaces particularly vulnerable to pharmacological intervention and thus rich sources of therapeutic targets.

The CRE-DDC framework specifically addresses the challenge of distinguishing driver co-option events (those causal to disease phenotypes) from passenger events (incidental network activations) through quantitative assessment of network topology and dynamics. This discrimination is essential for prioritizing targets with the greatest potential therapeutic value. The model further proposes that the evolutionary age of co-opted networks correlates with their pleiotropic effects, wherein ancient networks (conserved across species) typically influence multiple physiological processes, while recently evolved networks often display more restricted, tissue-specific functions [8]. This principle guides toxicity predictions by identifying targets whose inhibition might affect multiple biological systems versus those with more limited off-target potential.

Quantitative Data Presentation

The CRE-DDC model utilizes specific quantitative metrics to evaluate potential co-option events. These metrics enable researchers to prioritize networks based on their likelihood of functional significance in disease processes.

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Network Co-option in the CRE-DDC Framework

| Metric | Definition | Measurement Method | Interpretation Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Co-option Index (NCI) | Degree of overlap between disease-associated genes and reference gene networks | Jaccard similarity coefficient calculated between disease gene set and canonical pathways [9] | NCI > 0.3 indicates significant co-option |

| Evolutionary Conservation Score (ECS) | Phylogenetic conservation of the co-opted network | Maximum evolutionary distance across species where network orthology is maintained | ECS > 75% indicates ancient, highly conserved network |

| Topological Significance Value (TSV) | Statistical significance of network connectivity patterns | Hypergeometric test comparing observed versus random connectivity [8] | TSV < 0.05 indicates non-random network assembly |

| Differential Expression Enrichment (DEE) | Magnitude of coordinated expression changes in co-opted network | Mean fold-change of network components between disease and normal states | DEE > 2.0 indicates strong functional activation |

| Pleiotropy Risk Estimate (PRE) | Potential for off-target effects based on network multifunctionality | Number of distinct biological processes associated with network components | PRE > 5 processes suggests high pleiotropy risk |

Table 2: Implementation Outcomes for CRE-DDC Model Validation

| Implementation Outcome | Level of Analysis | Quantitative Measurement Method | Target Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adoption | Individual researcher | Number of labs implementing CRE-DDC protocols | >50 research groups within first year |

| Fidelity | Experimental protocol | Percentage of required steps consistently executed across implementations | >90% protocol adherence |

| Implementation Cost | Institutional | Personnel hours and reagents required for complete analysis | <200 hours and <$5,000 per network analyzed |

| Reach | Scientific community | Number of disease areas applying the framework | Application to >10 distinct disease domains |

| Sustainment | Research programs | Continued use of CRE-DDC beyond initial publication | >80% of early adopters maintaining use after 2 years [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identification of Co-opted Networks

Objective: To systematically identify gene regulatory networks that have been co-opted in disease states using multi-omics data.

Materials:

- RNA-seq or microarray data from disease and matched control tissues

- Reference gene network databases (e.g., KEGG, Reactome, custom networks)

- Computational resources for statistical analysis (R, Python environments)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize expression data using appropriate methods (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, RMA for microarrays). Log2-transform data to stabilize variance [9].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify significantly dysregulated genes (adjusted p-value < 0.05, fold change > 1.5) between disease and control conditions using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., DESeq2 for RNA-seq, limma for microarrays).

- Network Overlap Calculation: For each reference network, calculate the Network Co-option Index using the formula: NCI = |D ∩ N| / |D ∪ N|, where D is the set of differentially expressed genes and N is the set of genes in the reference network.

- Statistical Validation: Determine the significance of observed NCI values by comparing against null distributions generated through 10,000 permutations of random gene sets of equivalent size.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply Benjamini-Hochberg correction to control false discovery rate across all tested networks. Retain networks with FDR < 0.05 for further validation.

Troubleshooting:

- If too few networks show significant co-option, relax the differential expression threshold or include larger reference networks.

- If computational time is excessive for permutation testing, implement parallel processing or utilize pre-computed null distributions.

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Co-opted Networks

Objective: To experimentally validate the functional significance of identified co-opted networks using perturbation approaches.

Materials:

- Relevant cell line or primary cell model for the disease of interest

- siRNA, CRISPR, or small molecule inhibitors for network components

- Functional assays appropriate for disease phenotype (e.g., proliferation, apoptosis, migration assays)

- Equipment for high-content imaging and analysis (if applicable)

Procedure:

- Target Selection: Prioritize 3-5 hub genes within the co-opted network based on betweenness centrality and expression fold-change.

- Perturbation Design: Design and validate targeting reagents (siRNA, sgRNAs, or inhibitors) for selected hub genes. Include appropriate negative controls (non-targeting siRNA, empty vector, vehicle).

- Phenotypic Assessment: Transfert/transduce targeting reagents into disease-relevant cell models and perform functional assays at optimal timepoints post-perturbation (typically 48-96 hours).

- Network Response Monitoring: Assess expression changes in additional network components following hub gene perturbation to confirm network disruption.

- Dose-Response Validation: For pharmacological inhibitors, perform dose-response curves to establish IC50 values and confirm on-target effects through complementary genetic approaches.

Troubleshooting:

- If hub gene perturbation shows no phenotypic effect, consider functional redundancy and target multiple network components simultaneously.

- If off-target effects are suspected, use multiple distinct targeting reagents for the same gene to confirm specificity.

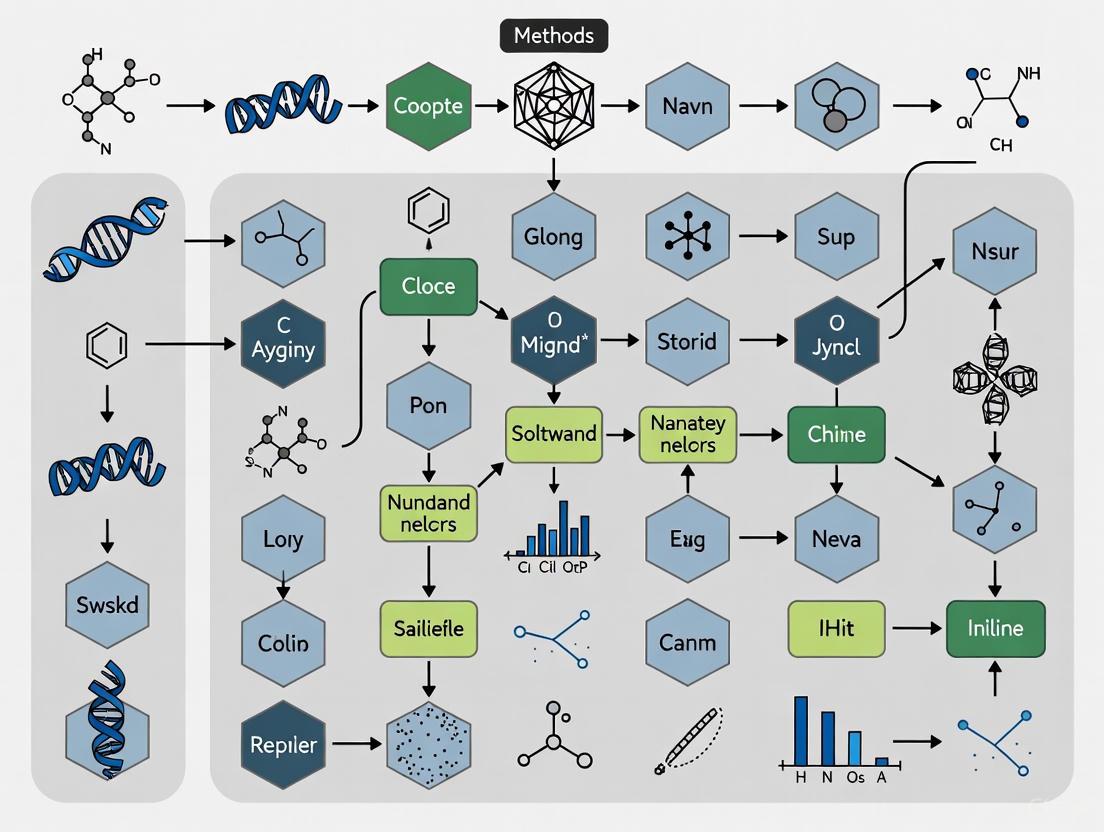

Visualization of CRE-DDC Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete CRE-DDC analytical pipeline from data integration through experimental validation:

CRE-DDC Analytical Pipeline

Signaling Pathways in Network Co-option

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual framework of network co-option, where ancestral networks are repurposed through evolutionary processes to generate novel functions:

Network Co-option Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementation of the CRE-DDC model requires specific reagents and computational tools to successfully identify and validate co-opted networks.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for CRE-DDC Implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Implementation Role |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Screening Libraries | High-throughput gene perturbation | Identification of essential network components through loss-of-function screens |

| Pathway-Specific Inhibitors | Pharmacological network perturbation | Chemical validation of network dependency and therapeutic potential |

| Multi-omics Datasets | Comprehensive molecular profiling | Input data for network co-option analysis across transcriptional, epigenetic, and proteomic dimensions |

| Network Analysis Software | Topological computation | Calculation of network metrics and identification of hub genes [10] |

| Gene Set Enrichment Tools | Statistical pathway analysis | Quantification of network activity changes between conditions |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Phenotypic characterization | Assessment of morphological and functional consequences of network perturbation |

| scRNA-seq Platforms | Single-cell resolution profiling | Identification of cell-type specific network co-option patterns |

Data Management and Analysis Standards

Proper implementation of the CRE-DDC model requires rigorous data management and statistical approaches to ensure reproducible results [9]. All quantitative data should undergo careful checking for errors and missing values before analysis, with appropriate variable definition and coding. Descriptive statistics including measures of central tendency (mean, median) and spread (standard deviation) should be calculated to summarize typical patterns in the data. For inferential analyses, statistical tests should produce p-values accompanied by measures of magnitude (effect sizes) to interpret the practical significance of observed effects, relationships, or differences [9].

Data visualization should follow established principles of clarity and effectiveness [10]. Figures should be labeled with descriptive captions that draw attention to important features, while tables should be organized to help readers grasp the meaning of presented data with ease. Color coding should be used strategically to convey meaning, with consistent application across all model components [11]. For example, specific colors might designate different types of data or analytical outcomes, but the total palette should be limited to 6-8 colors to minimize cognitive load [12].

Core Concepts and Key Evidence

Network interlocking describes a phenomenon where a gene regulatory network (GRN) is co-opted into a new developmental context, causing its components to become developmentally linked across multiple organs. Subsequent evolutionary changes to the network, driven by its function in one organ, are then mirrored in all other organs where it is active, even if these changes provide no selective advantage in those secondary contexts [4].

Key Evidence from Drosophila Posterior Spiracle Network

Research in Drosophila provides a foundational example. The gene network controlling the formation of the larval posterior spiracle has been co-opted into two other distinct contexts: the male genitalia and the testis mesoderm. This represents a case of sequential co-option, where the same core network is reused in multiple novel traits [4].

Table 1: Key Genes in the Co-opted Drosophila Network and Their Functions

| Gene | Gene Product Type | Primary Function in Spiracle | Co-opted Function in Male Genitalia | Co-opted Function in Testis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal-B (Abd-B) | Hox Protein | Master regulator of posterior spiracle organogenesis in A8 segment [4] | Initiates network recruitment [4] | Not Specified |

| Engrailed (En) | Transcription Factor | Posterior compartment determinant; uniquely activated in A8 anterior cells [4] | Required for posterior lobe formation [4] | Required for sperm liberation [4] |

| Spalt (Sal) | Transcription Factor | Activated by Abd-B; activates en in A8 for stigmatophore formation [4] | Part of co-opted network [4] | Part of co-opted network [4] |

| wingless (wg) | Signalling Molecule | Segment polarity; A8-specific patterning modulated by Abd-B [4] | Part of co-opted network [4] | Not Specified |

| Empty spiracles (Ems) | Transcription Factor | Activated by Abd-B; regulates internal spiracular chamber formation [4] | Part of co-opted network [4] | Part of co-opted network [4] |

| Cut (Ct) | Transcription Factor | Activated by Abd-B; regulates internal spiracular chamber formation [4] | Part of co-opted network [4] | Part of co-opted network [4] |

A critical evolutionary novelty arising from this interlocking was the activation of Engrailed (En), a canonical posterior compartment gene, in the anterior compartment of the A8 segment (A8a). This expression pattern is a developmental anomaly not observed in other segments or in more distantly related Diptera like Episyrphus balteatus, which possesses a less protrusive spiracle [4]. Enhancer deletion experiments demonstrated that this novel En expression is not required for spiracle development itself but is essential for its co-opted function in the testis for spermiation. This indicates that the A8a En expression is a pre-adaptive novelty—a developmental change that arose not for its utility in the original organ, but as a consequence of the network's new role in a different tissue [4].

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Identifying a Co-opted and Interlocked Gene Network

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying and validating a co-opted gene network, based on methodologies exemplified in Drosophila research [4].

Workflow Overview: The process begins with comparative transcriptomics and genomics to identify candidate networks, followed by genetic and transgenic experiments to validate the network's function and regulation across different organs, and culminates in evolutionary biology techniques to trace the origin and history of the co-option event.

Detailed Procedure:

Comparative Transcriptomics & Genomics

- Objective: Identify a set of genes expressed in multiple, morphologically unrelated organs.

- Methods:

- Perform RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) or single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) on the developing organs of interest.

- Conduct comparative analysis to identify significantly overlapping gene sets between organs.

- Search for shared cis-regulatory elements (CREs) or enhancers upstream of the candidate genes using ATAC-seq or ChIP-seq data [13].

Functional Genetic Validation

- Objective: Test if the candidate network is necessary for the development of all organs where it is expressed.

- Methods:

- Use CRISPR/Cas9 to generate knockout mutations or RNAi to knock down key transcription factors (e.g., Abd-B, Sal) within the network.

- Assess the phenotypic consequences in each organ (e.g., spiracle formation, posterior lobe morphology, sperm liberation) via microscopy [4].

cis-Regulatory Analysis

- Objective: Determine if the same CREs control gene expression in different organs, confirming co-option rather than independent evolution.

- Methods:

- Clone candidate CREs (e.g., the enD enhancer for engrailed) into reporter constructs (e.g., lacZ, GFP).

- Generate and analyze transgenic organisms. Expression of the reporter in multiple organs indicates shared regulatory control [4].

- Delete specific enhancers in vivo and assess the impact on gene expression and function in each organ [4].

Evolutionary Analysis

- Objective: Trace the evolutionary history of the network's co-option and the emergence of any novel expression patterns.

- Methods:

- Isolate and sequence orthologs of key network genes and their CREs from multiple related species.

- Use antibody staining or in situ hybridization to map the expression patterns of network genes in these species.

- Perform phylogenetic comparative analysis to determine the order in which the network was co-opted into different organs and when novelties (e.g., A8a En expression) arose [4].

Protocol: Validating Network Interlocking via Enhancer Deletion

This protocol details the specific experiment used to demonstrate that the A8a expression of engrailed is an interlocked novelty required in the testis but not the spiracle [4].

Workflow Overview: A targeted deletion of a tissue-specific enhancer is created to isolate the gene's function in one organ system from another. The phenotypic consequences are then quantitatively assessed in both organs to determine the requirement of the gene in each context.

Detailed Procedure:

Targeted Enhancer Deletion:

- Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, create a clean deletion of the enD enhancer (a 439 bp region) from the engrailed-invected locus.

Expression Analysis:

- In the deletion mutant, use antibody staining against the En protein or in situ hybridization for en mRNA to confirm the loss of En expression in the A8 anterior compartment cells surrounding the spiracle. Expression in posterior compartments should remain unaffected.

Phenotypic Assessment in Primary Organ (Spiracle):

- Method: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) or high-resolution brightfield microscopy to image the larval posterior spiracles of mutant and wild-type larvae.

- Quantitative Measures: Measure the length and width of the stigmatophore. Score the overall morphology for defects (e.g., failure to protrude, abnormal cuticle). The key finding is that spiracle development proceeds normally despite the loss of A8a En [4].

Phenotypic Assessment in Co-opted Organ (Testis):

- Method: Dissect adult testes from mutant and wild-type males. Analyze sperm bundles using microscopy (e.g., phase-contrast).

- Quantitative Measures: Score the proportion of testes showing defective "spermiation" – the process of sperm release or liberation. The key finding is a failure in sperm liberation in the mutant, confirming the requirement of the A8a-expressed En for testis function [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Network Interlocking

| Research Reagent | Function and Application in Network Analysis |

|---|---|

| Anti-Engrailed/Invected Antibody (4D9) | Labels En/Inv proteins to visualize expression patterns in embryos, tissues (e.g., spiracle, testis). Critical for identifying novel expression domains [4]. |

| Anti-Spalt (Sal) Antibody | Labels Sal protein; serves as a marker for specific structures like the spiracle stigmatophore and validates network activation [4]. |

| enD-lacZ / enD-GFP Reporter Transgene | A transgenic construct where the enD enhancer drives a reporter gene. Used to visualize enhancer activity, confirm its specificity, and test its regulation [4]. |

| Abd-B Mutant / RNAi Line | Loss-of-function tools to disrupt the master regulator of the network and assess downstream effects on gene expression and morphology [4]. |

| enD Enhancer Deletion Mutant (CRISPR) | A specific mutant line with the enD enhancer deleted. The key tool for dissecting the function of a novel expression pattern from the gene's ancestral function [4]. |

| Cross-Reactive Antibodies (e.g., Anti-Sal) | Antibodies that work across multiple species (e.g., D. melanogaster, D. virilis). Essential for evolutionary comparisons of network deployment [4]. |

Developmental co-option refers to the evolutionary process where existing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) are reused in new developmental contexts to generate novel morphological structures. This mechanism avoids the need to evolve complex genetic programs from scratch and represents a fundamental principle in evolutionary developmental biology. The fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, provides a powerful model system for studying co-option due to its genetic tractability and the recent evolution of several morphological novelties. Research has revealed that co-option operates not through the creation of new genes, but through the redeployment of ancestral GRNs, including their transcription factors, signaling pathways, and cis-regulatory elements, to new developmental locations and times [14].

This application note examines three compelling case studies of co-option in Drosophila: the larval posterior spiracles, the male genital posterior lobe, and the testis. These cases demonstrate both the mechanisms of network reuse and the experimental methodologies used to identify and validate co-opted networks. Understanding these processes is crucial for researchers investigating the origins of evolutionary novelties, as the same principles of network reuse can inform our understanding of disease states and developmental disorders where gene regulatory programs are misappropriated.

Case Study 1: The Posterior Spiracle and its Repeated Co-options

Background and Key Findings

The posterior spiracle is a larval respiratory organ in Drosophila whose development is controlled by a well-defined GRN activated by the Hox protein Abdominal-B (Abd-B) in the eighth abdominal segment (A8) [4]. This network includes key genes such as Unpaired (Upd), Empty spiracles (Ems), Cut (Ct), Spalt (Sal), and engrailed (en), which coordinate to pattern both the internal spiracular chamber and the external protruding stigmatophore [4].

A remarkable discovery shows that this spiracle GRN has been co-opted into two other, phylogenetically younger tissues: the male genitalia (forming the posterior lobe) and the testis mesoderm (where it is required for sperm liberation) [4]. This represents a striking example of sequential co-option, where the same network is reused multiple times, each exposure creating potential for further evolutionary innovation. Associated with one co-option event, an expression novelty appeared: the activation of the posterior compartment determinant Engrailed in the anterior compartment of the A8 segment, a location where it has no ancestral function [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Tracing Evolutionary Origin of Expression Patterns

- Objective: Determine when engrailed anterior compartment expression emerged during evolution.

- Methodology:

- Select dipteran species representing different evolutionary time points (e.g., D. melanogaster, D. virilis, Episyrphus balteatus).

- Perform antibody staining of whole-mount embryos using cross-reactive anti-Sal and anti-En antibodies.

- Analyze and compare expression patterns relative to morphological structures.

- Key Reagents: Cross-reactive anti-Sal antibody, anti-Engrailed antibody, species-specific embryo collection.

- Outcome: Revealed that En expression in A8a is absent in E. balteatus but present in Drosophila species, dating its acquisition to brachiceran diptera [4].

Protocol 2: Identifying Tissue-Specific Enhancer Elements

- Objective: Isolate cis-regulatory elements (CREs) controlling engrailed expression in the posterior spiracle.

- Methodology:

- Utilize available engrailed-invected locus enhancer-reporter library (enH-lacZ, enM-lacZ, enP-lacZ, enX-lacZ, enD-lacZ).

- Test reporter expression patterns in embryonic tissues.

- Fine-map the active enhancer via dissection (deletion analysis) of the enD region.

- Identify a minimal 439 bp enhancer (enD0.4) sufficient for spiracle expression.

- Key Reagents: enD-lacZ, enD-ds-GFP, or enD-0.4-mCherry reporter constructs.

- Outcome: Identified a specific enhancer driving En expression in a ring around the spiracle opening [4].

Protocol 3: Functional Validation of Enhancer Necessity

- Objective: Test whether the identified enhancer is necessary for gene function in different tissues.

- Methodology:

- Delete the enD enhancer in vivo using CRISPR/Cas9.

- Assess phenotypic consequences in the spiracle versus the testis.

- Compare morphological outcomes in both tissues.

- Outcome: Demonstrated that A8 anterior En activation is not required for spiracle development but is necessary in the testis for spermiation [4].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The core posterior spiracle GRN involves multiple coordinated signaling events. Abd-B activation in the dorsal ectoderm initiates the network by triggering expression of the JAK/STAT ligand Unpaired, along with transcription factors Empty spiracles and Cut in A8 anterior compartment cells [4]. Simultaneously, Abd-B activates Spalt in both anterior and posterior A8 cells, which in turn activates engrailed in a unique pattern that breaks the traditional segmental boundary [4]. These primary transcription factors then regulate downstream effectors including cytoskeletal regulators (RhoGAP Cv-c, RhoGEF64C), cell polarity genes (crumbs), and various cadherins, ultimately orchestrating the morphogenesis of this complex organ [4].

Table 1: Quantitative Data Summary from Posterior Spiracle Co-option Study

| Parameter Investigated | Experimental Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| En expression evolution | Present in D. melanogaster and D. virilis (40 MYA divergence); absent in E. balteatus (100 MYA divergence) | Dates En A8a acquisition to brachiceran diptera [4] |

| Minimal spiracle enhancer size | 439 bp (enD0.4) | Sufficient for specific expression in spiracle ring [4] |

| Functional requirement of A8a En | Not required for spiracle development; required for testis spermiation | Pre-adaptive novelty with tissue-specific functions [4] |

| Network components shared | ≥10 genes from spiracle network co-opted to male genitalia | Evidence of full network co-option [4] |

Case Study 2: Co-option to Male Genitalia and the Posterior Lobe

Background and Key Findings

The posterior lobe is a hook-shaped cuticular structure in the male genitalia of D. melanogaster and closely related species that is used to grasp females during mating [14]. This morphological novelty evolved approximately 11.6 million years ago in the melanogaster clade and represents a classic example of a recently evolved structure ideal for studying the origins of novelty [15]. The posterior lobe develops from an ancestral genital tissue called the lateral plate through a localized increase in apical cell height [15].

Research has demonstrated that the posterior lobe employs essentially the same GRN that controls the formation of the larval posterior spiracle [14]. This includes the redeployment of multiple genes, with at least seven cases showing activation by the same cis-regulatory elements in both organs [4]. The core transcription factor Pox neuro (Poxn) is critical for proper posterior lobe formation, and its regulatory elements drive expression in both the posterior spiracle and the posterior lobe [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 4: Enhancer Co-option Validation

- Objective: Test whether the same enhancer controls gene expression in ancestral and novel structures.

- Methodology:

- Clone the putative enhancer region from a gene of interest (e.g., Poxn second exon/intron region).

- Create GFP reporter constructs and generate transgenic flies.

- Analyze expression patterns in both ancestral (spiracle) and novel (genitalia) contexts.

- Compare timing and spatial distribution of reporter expression.

- Key Reagents: Poxn genomic regions from multiple species, GFP reporter vector, transgenic fly generation.

- Outcome: The same Poxn enhancer drives expression in both posterior spiracle and posterior lobe [14].

Protocol 5: Cross-Species Enhancer Function Test

- Objective: Determine if enhancer function predates the morphological novelty.

- Methodology:

- Clone orthologous enhancer regions from non-lobed species (e.g., D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura).

- Test these enhancers in D. melanogaster reporter assays.

- Assess ability to drive expression in the posterior lobe.

- Key Reagents: Orthologous enhancer sequences from multiple species, D. melanogaster host for transgenesis.

- Outcome: Enhancers from non-lobed species drive expression in D. melanogaster posterior lobe, indicating ancestral function [14].

Protocol 6: Signaling Pathway Manipulation

- Objective: Determine the role of specific signaling pathways in novelty formation.

- Methodology:

- Perform RNAi-mediated knockdown of candidate signaling ligands (e.g., Delta) using tissue-specific drivers (e.g., Poxn-GAL4).

- Express constitutively active forms of signaling pathway components (e.g., Notch intracellular domain).

- Quantify morphological changes in the posterior lobe.

- Key Reagents: Delta-shRNA, Poxn-GAL4 driver, UAS-Notch[intra], scanning electron microscopy.

- Outcome: Notch signaling expansion is necessary and sufficient for posterior lobe development [15].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

A key finding in posterior lobe development is the requirement for Notch signaling. In D. melanogaster, the Notch ligand Delta shows spatially expanded expression in a zone adjacent to the developing posterior lobe, preceding and accompanying lobe formation [15]. This expanded pattern is unique to lobe-bearing species; non-lobed species show only limited Delta expression at the base of the claspers and lateral plates [15]. Notch activation, as read out by the expression of the canonical target E(spl)mβ, occurs in cells adjacent to the Delta expression domain, suggesting a signaling center that patterns the developing lobe [15]. The evolutionary expansion of this signaling center, rather than its de novo origin, appears to underlie the formation of this novelty.

Table 2: Notch Signaling Components in Posterior Lobe Development

| Component | Role in Posterior Lobe Development | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Delta ligand | Shows spatially expanded expression adjacent to developing lobe; required for proper lobe formation | RNAi knockdown results in smaller, defective lobes [15] |

| Notch receptor | Receives signal in lobe-forming region; activation sufficient to enlarge lobe | Constitutively active Notch increases lobe size [15] |

| E(spl)mβ | Canonical Notch target; marker of pathway activation | Expressed adjacent to Delta domain in lobe-forming species [15] |

| Regulatory elements | Control species-specific Delta expression pattern | Enhancers drive unique expression in D. melanogaster [15] |

Case Study 3: Co-option to Testis and the Concept of Interlocking

Background and Key Findings

The most recently discovered co-option of the posterior spiracle network is to the testis mesoderm, where it is required for spermiation - the process of sperm release [4]. This finding is significant because it represents co-option across germ layers, from an ectodermal structure (spiracle) to a mesodermal one (testis). This third co-option event created a situation the authors term "network interlocking" [4].

Network interlocking occurs when recently co-opted networks become interconnected such that any change to the network due to its function in one organ will be mirrored by other organs, even if it provides no selective advantage to them [4]. This phenomenon explains the appearance of what the authors call "pre-adaptive developmental novelties" - expression changes that initially have no function but may acquire one in the future. The activation of Engrailed in the anterior compartment of the A8 segment represents one such novelty: while it has no function in the spiracle, it is necessary in the testis, and its presence in the spiracle is a consequence of network interlocking [4].

Advanced Methodologies for Studying Testis Gene Networks

Protocol 7: Single-Nucleus Multi-omics Analysis

- Objective: Map enhancer-driven regulatory networks in complex tissues.

- Methodology:

- Microdissect testis apical tips to enrich for stem cell niche populations.

- Isolate nuclei and perform simultaneous snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq using 10x Genomics Multiome platform.

- Integrate data to link accessible regulatory elements with gene expression.

- Infer enhancer-gene regulons (eRegulons) using SCENIC+.

- Validate predictions through functional experiments.

- Key Reagents: 10x Genomics Multiome platform, microdissection tools, computational analysis pipeline.

- Outcome: Identification of 147 cell type-specific eRegulons in testis, revealing regulatory logic of spermatogenesis [16].

Protocol 8: Functional Validation of Predicted Transcription Factors

- Objective: Test the role of computationally predicted TFs in spermatogenesis.

- Methodology:

- Select candidate TFs identified through multi-omics (e.g., ovo, klumpfuss).

- Perform CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout in whole animals or tissue-specific manner.

- Analyze phenotypic consequences on germline stem cell regulation and differentiation.

- Validate enhancer binding through additional assays.

- Key Reagents: CRISPR/Cas9 system, germline stem cell markers, differentiation markers.

- Outcome: Identification of essential roles for ovo and klumpfuss in germline stem cell regulation [16].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms in Testis Development

Single-nucleus multi-omics of the Drosophila testis has revealed intricate regulatory networks coordinating germline and somatic cell development. The analysis of 10,335 nuclei identified canonical Wnt signaling as a key pathway, with the effector TF Pangolin/Tcf activating lineage-specific targets in germline, soma, and niche cells [16]. The Pan eRegulon links Wnt activity to cell adhesion, intercellular signaling, and germline stem cell maintenance [16]. This comprehensive mapping provides a framework for understanding how co-opted networks integrate with tissue-specific regulatory programs.

The testis environment represents a complex signaling ecosystem where multiple pathways interact. Previous studies have established essential roles for JAK/STAT signaling in CySC self-renewal and GSC adhesion, BMP signaling via Mad in GSC maintenance, and Hedgehog signaling through Cubitus interruptus in CySC identity [16]. The integration of the co-opted spiracle network into this established signaling context demonstrates how novel genetic programs can be incorporated into complex developmental environments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Co-option in Drosophila

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Constructs | enD-lacZ, enD-ds-GFP, enD-0.4-mCherry; Poxn-GFP reporters | Visualize enhancer activity in vivo; test regulatory element function [4] [14] |

| Antibodies for Staining | Anti-Sal, anti-Engrailed, anti-Delta | Detect protein expression patterns across species; analyze tissue morphology [4] [15] |

| Genetic Tools | Poxn-GAL4 driver; UAS-RNAi lines (e.g., Delta-shRNA); UAS-Notch[intra] | Tissue-specific manipulation of gene function; pathway activation/inhibition [15] |

| Genomic Resources | Orthologous enhancer sequences from multiple species; CRISPR/Cas9 for enhancer deletion | Test evolutionary conservation of regulatory function; assess necessity of specific elements [4] [14] |

| Advanced Profiling | 10x Genomics Multiome platform (snRNA-seq + snATAC-seq) | Joint profiling of gene expression and chromatin accessibility; infer regulatory networks [16] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | SCENIC+ for eRegulon inference; pseudotime analysis | Reconstruct enhancer-driven networks; model developmental trajectories [16] |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Network Co-option and Interlocking Concept

Experimental Workflow for Enhancer Analysis

Notch Signaling in Posterior Lobe Development

The case studies presented here demonstrate how co-option operates as a fundamental evolutionary mechanism for generating novelty. The repeated redeployment of the posterior spiracle network to the male genitalia and testis reveals several important principles: (1) co-option can occur sequentially to multiple tissues, (2) networks can become interlocked, creating developmental constraints, and (3) pre-adaptive expression novelties can emerge without immediate function [4].

For researchers studying evolutionary development, these findings provide both methodological frameworks and conceptual advances. The experimental approaches detailed here - from enhancer-reporter assays to single-cell multi-omics - offer powerful tools for identifying and validating co-opted networks in other systems. The concept of network interlocking suggests that developmental systems may accumulate regulatory connections that constrain future evolutionary trajectories, with implications for understanding evolutionary constraint and innovation.

In drug development and disease research, understanding how gene networks are redeployed in different contexts can inform mechanisms of pathology and identify potential therapeutic targets. The principles revealed in these Drosophila studies have broad relevance for understanding how existing genetic programs can be misappropriated in disease states, providing evolutionary insights into developmental disorders and cellular malfunctions.

Distinguishing Co-option from Trait Loss and Expression Changes

In evolutionary biology, the origin of novel complex traits often involves co-option, where existing genes, gene networks, or structures are recruited for new functions [3] [17]. However, distinguishing genuine co-option from other evolutionary changes such as trait loss or simple expression shifts presents significant methodological challenges. This protocol provides a structured framework for identifying and validating co-option events, with particular emphasis on differentiating them from similar evolutionary phenomena.

Co-option describes the process where characters that evolved for one reason change their function at a later time with little to no concurrent structural modification [3]. Francois Jacob aptly noted that "Evolution does not produce novelties from scratch. It works on what already exists," often through co-option of existing systems [17]. Proper identification requires careful analysis of genetic, regulatory, and phenotypic data across multiple species and experimental conditions.

Conceptual Framework and Key Definitions

Core Evolutionary Concepts

Table 1: Key Concepts in Evolutionary Change

| Term | Definition | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Co-option | Recruitment of existing genes, structures, or networks for new functions [3] [17] | Functional shift without structural overhaul; exploits pre-existing capabilities |

| Trait Loss | Complete disappearance of a previously functional character | Elimination of function; often through disruptive mutations |

| Expression Change | Alteration in timing, level, or spatial pattern of gene expression without functional shift [17] | Quantitative or spatial modulation; heterochronic shifts; domain expansions/contractions |

| Exaptation | Replacement term for "preadaptation" to avoid teleological implications [3] | Traits evolved for one purpose later co-opted for new function |

| Cis-regulatory Evolution | Changes in non-coding regulatory DNA sequences affecting gene expression [17] | Tissue-specific effects; modular changes |

Theoretical Foundation

The concept of co-option solves a fundamental problem in evolutionary biology: how complex traits appear to arise rapidly without transitional forms. As Darwin recognized, this process provides "an extremely important means of transition" where organs serving major and minor functions could be modified to emphasize the latter [3]. This framework explains how organisms carry within their genetic and structural makeup the potential for rapid evolutionary change that appears miraculous in retrospect but operates through standard Darwinian mechanisms.

Experimental Protocols for Identification

Comparative Expression Analysis Across Species

Objective: Identify novel expression patterns through cross-species comparison of gene expression in homologous tissues.

Materials:

- RNA extraction kits (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy)

- RNA sequencing library preparation reagents

- In situ hybridization reagents

- Specimens from multiple closely-related species

Procedure:

- Select target species with known phylogenetic relationships and divergence times

- Collect homologous tissues at equivalent developmental stages

- Perform RNA sequencing (bulk or single-cell) on all samples

- Conduct in situ hybridization for spatial localization of candidate genes

- Analyze expression patterns for species-specific features

Data Interpretation:

- Co-option indicator: Novel spatial or temporal expression domain with conserved function in ancestral context

- Trait loss indicator: Absence of expression domain present in outgroup species

- Expression change indicator: Quantitative differences or heterochronic shifts without novel domains

Table 2: Interpreting Expression Pattern Changes

| Observation | Possible Interpretation | Validation Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Novel expression domain in one species | Potential co-option | Cis-regulatory analysis; functional assays |

| Loss of conserved expression domain | Trait loss | Mutation analysis; ancestral state reconstruction |

| Altered timing or level of expression | Expression change | Promoter analysis; transcription factor binding |

| Conserved expression across species | Evolutionary constraint | Functional constraint analysis |

Cis-Regulatory Element Dissection

Objective: Localize genetic changes responsible for novel expression patterns to specific regulatory elements.

Materials:

- PCR cloning reagents

- Reporter vectors (e.g., GFP/lacZ)

- Embryo microinjection apparatus

- Transgenic organism protocols

Procedure:

- Clone candidate cis-regulatory regions from multiple species

- Create reporter constructs with species-specific regulatory elements

- Generate transgenic lines for each construct

- Analyze reporter expression patterns in equivalent genetic backgrounds

- Test minimal elements through deletion analysis

- Introduce point mutations to test specific binding sites

Case Example: In the evolution of Neprilysin-1 (Nep1) gene expression in Drosophila santomea, researchers localized a novel optic lobe enhancer to a specific intronic region that had accumulated mutations, uncovering how co-option exploited cryptic regulatory activities [17].

Co-expression Network Analysis

Objective: Identify changes in gene-gene relationships underlying novel traits.

Materials:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing platform

- Computational resources for network analysis

- Co-expression analysis software (e.g., WGCNA, rho proportionality metrics)

Procedure:

- Generate single-cell RNA-seq data from relevant tissues across species/conditions

- Construct co-expression networks using appropriate association measures

- Identify network modules associated with traits of interest

- Compare network topology between species/conditions

- Validate functional relationships through perturbation experiments

Key Consideration: Single-cell data enables reconstruction of personalized co-expression networks, allowing identification of context-specific regulatory relationships [18]. Use robust association measures like rho proportionality that perform well with sparse single-cell data.

Visualization and Analytical Framework

Decision Framework for Distinguishing Evolutionary Changes

The following workflow provides a systematic approach for classifying evolutionary changes:

Experimental Workflow for Co-option Analysis

The comprehensive experimental approach for identifying co-option events involves multiple validation steps:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Co-option Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Comparative Genomics | BLAST, UCSC Genome Browser, PhyloP | Identify conserved non-coding elements with potential regulatory function |

| Cis-regulatory Analysis | GFP/lacZ reporter vectors, PCR cloning kits, embryo microinjection systems | Test regulatory potential of genomic elements across species |

| Gene Expression Profiling | RNA-seq kits, in situ hybridization reagents, single-cell RNA-seq platforms | Characterize spatial and temporal expression patterns across species |

| Network Analysis | WGCNA, rho proportionality metrics, Gaussian graphical models | Construct and compare gene co-expression networks [19] [18] |

| Functional Validation | CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, RNAi reagents, small molecule inhibitors | Test functional significance of identified regulatory elements |

Data Interpretation Guidelines

Critical Assessment of Co-option Evidence

When evaluating potential co-option events, consider these key criteria:

- Document pre-existing component: Identify the ancestral system that was co-opted, including its original function and context

- Demonstrate functional shift: Provide evidence that the component serves a different biological role in the derived context

- Identify regulatory mechanism: Trace the genetic or regulatory changes that enabled the new function

- Exclude alternative explanations: Rule out trait loss, convergent evolution, or simple expression changes

Quantitative Thresholds and Metrics

Table 4: Key Quantitative Metrics for Classification

| Metric | Co-option Evidence | Trait Loss Evidence | Expression Change Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression domain overlap | Novel spatial/temporal domain with conserved ancestral domains | Complete absence of ancestral domains | Altered boundaries or levels of existing domains |

| Sequence conservation | Accelerated evolution in regulatory regions | Disruptive mutations in coding/regulatory regions | Moderate changes in regulatory regions |

| Network connectivity | Altered gene-gene interactions in novel context [18] | Loss of network connections | Quantitative changes in connection strength |

| Functional assays | Gain-of-function in novel context | Loss-of-function in all contexts | Quantitative changes in functional output |

Troubleshooting and Common Pitfalls

- Misinterpreting trait loss: Use appropriate outgroups for ancestral state reconstruction to distinguish true loss from derived states

- Overlooking cryptic variation: Consider that co-option may exploit standing genetic variation not visible in standard assays

- Confounding with pleiotropy: Distinguish true co-option from cases where a single function operates in multiple contexts

- Technical limitations: Address potential artifacts in expression analysis, particularly with single-cell RNA-seq data sparsity [18]

- Phylogenetic sampling: Ensure adequate taxonomic sampling to properly reconstruct evolutionary sequences

Following these structured protocols and analytical frameworks will enable researchers to robustly distinguish co-option from other evolutionary changes, advancing our understanding of how novel traits originate through the creative redeployment of existing biological components.

A Methodological Toolkit: From Forward Genetics to Network-Based Drug Repurposing

Forward Genetic Screens for Identifying Causative Mutations and Top Regulators

Forward genetic screening represents a powerful, unbiased approach for discovering novel genes essential for specific biological processes or phenotypes. Unlike reverse genetics that studies the phenotype resulting from a known genetic modification, forward genetics begins with an observed phenotype and works to identify the underlying causative mutations [20]. This methodology has been instrumental in elucidating complex biological pathways across model organisms, from Caenorhabditis elegans to zebrafish and mammalian organoid systems.

This protocol is framed within broader research on identifying co-opted developmental gene networks—instances where existing genetic programs are reused in new biological contexts to drive evolutionary novelty. A seminal example is the recruitment of the posterior spiracle gene network to the Drosophila male genitalia, and subsequently to the testis mesoderm, illustrating how sequential co-option can lead to the emergence of new regulatory functions and pre-adaptive novelties [4]. The following sections provide detailed application notes and protocols for executing forward genetic screens, with a focus on identifying key regulatory factors and their causative mutations.

Key Principles and Applications

Core Concept of Forward Genetic Screens

Forward genetic screening involves random mutagenesis of an organism's genome followed by systematic screening of progeny for specific phenotypic deviations. Mutants of interest are then subjected to genetic mapping and molecular identification to link the phenotype to a genotype. This approach is particularly valuable for discovering genes with redundant functions, as selection of weak mutants can help identify genes that might be missed in standard screens [21].

The Phenomenon of Network Co-option

Network co-option refers to the evolutionary recruitment of existing developmental gene networks into new morphological or physiological contexts. Research in Drosophila has demonstrated that the co-option of the posterior spiracle network to the male genitalia and testis mesoderm can lead to regulatory interlocking, wherein changes to the network due to its function in one organ are mirrored in other organs, even if it provides no selective advantage to them [4]. This interlocking effect explains the appearance of evolutionary novelties, such as the expression of the posterior segment determinant Engrailed in the anterior compartment of the A8 segment, where it initially served no function but presented a pre-adaptive opportunity [4].

Experimental Protocols

Mutagenesis and Mutant Isolation

The initial phase involves creating random mutations in a population of organisms and screening for phenotypes of interest.

- Mutagenesis using EMS: Treat populations with chemical mutagens like Ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS), which induces point mutations primarily through G/C to A/T transitions [21] [20]. For C. elegans, synchronize a large population of young adult hermaphrodites and expose them to a defined EMS concentration (e.g., 47 mM) for 4 hours with gentle agitation. After mutagenesis, wash the worms thoroughly to remove EMS residue [21].

- Screening Strategy: Allow the mutagenized generation (P0) to self-reproduce. Collect their progeny (F1) and plate them individually. The F2 generation from these clonal F1 lines is then screened for the phenotype of interest (e.g., developmental defects, metabolic alterations, or behavioral changes). Prioritize and isolate stable mutant lines from the F2 population [21].

- Considerations for Model Organisms:

- Zebrafish: Similar principles apply using mutagens like N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU). A recent screen for modifiers of ApoB-lipoprotein metabolism in zebrafish successfully identified novel alleles in genes like mttp, apobb.1, and mia2 [20].

- CRISPR-based Screening in Organoids: In engineered colorectal cancer organoids, CRISPR/Cas9-based forward genetic screens have been used to identify novel regulators of metastasis, such as CTNNA1 and BCL2L13, by screening for invasion, migration, and metastatic potential in vivo [22].

Backcrossing and Mapping

Once a stable mutant line is established, the causative mutation must be identified through a combination of genetic crossing and genomic analysis.

- Backcrossing: Outcross the isolated mutant to a wild-type strain (preferably with a polymorphic genetic background) for at least two generations. This process reduces the background mutagenic load and separates the causative mutation from unrelated EMS-induced mutations [21] [20].

- Mutation Mapping and Identification: Traditional positional cloning can be time-consuming. The following workflow integrates modern whole-genome sequencing (WGS) for efficiency:

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Extract genomic DNA from a pool of mutant individuals and sequence using next-generation sequencing platforms [21] [20].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Use mapping-by-sequencing algorithms (e.g., WheresWalker) to identify genomic intervals linked to the phenotype. These tools detect low-heterozygosity regions or calculate allelic frequencies to pinpoint candidate regions [20].

- Variant Calling: Within the linked interval, identify all EMS-induced sequence variants (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms or small indels) [21].

- Candidate Gene Validation: Select candidate genes based on the predicted impact of the mutation (e.g., nonsense, missense, or splice-site mutations). Validate the causative gene by recreating the phenotype using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing to introduce the identified mutation into a wild-type background [20].

Targeted Forward Genetics

For a saturating mutational analysis of specific genomic loci, Targeted Forward Genetics (TFG) can be employed. This method uses precise allele replacement via homologous recombination to generate a library of mutants spanning a target locus, followed by phenotypic screening. This approach is particularly useful for dissecting functional elements within a defined genomic region [23].

Data Presentation

Quantitative Comparison of Mutagenesis and Mapping Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Key Forward Genetic Screening Methods

| Method | Mutagen | Organism/System | Key Advantage | Primary Application | Identification Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Mutagenesis [21] [20] | EMS, ENU | C. elegans, Zebrafish | Unbiased, genome-wide coverage | Identifying novel factors in biological processes | Whole-genome sequencing & variant analysis |

| CRISPR-based Screening [22] | CRISPR/Cas9 | Colorectal Cancer Organoids | Targeted, high-throughput | Identifying regulators of complex traits (e.g., metastasis) | Next-generation sequencing of guide RNAs |

| Targeted Forward Genetics (TFG) [23] | Homologous Recombination | Fission Yeast (S. pombe) | Saturates specific target loci | Fine-scale analysis of gene/regulatory element function | Direct sequencing of the targeted locus |

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Forward Genetic Screens

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| EMS (Ethyl methanesulfonate) [21] [20] | Chemical mutagen that induces random point mutations. | Creating mutant populations in C. elegans and zebrafish for phenotypic screening. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System [22] | Enables targeted gene knockouts or edits in a pooled library format. | High-throughput screening for metastasis regulators in engineered cancer organoids. |

| Polymorphic Strain [20] | Wild-type strain with genetic differences from the mutant strain. | Used in backcrossing and for generating mapping populations. |

| WheresWalker Algorithm [20] | Bioinformatic tool for mapping-by-sequencing. | Identifies phenotype-linked genomic regions from whole-genome sequencing data of mutant pools. |

Mandatory Visualization

Forward Genetic Screening Workflow

Gene Network Co-option in Drosophila

Leveraging cis-Regulatory Element (CRE) Analysis and Enhancer Deletion

Cis-regulatory elements are non-coding DNA sequences that control the spatial and temporal expression of genes, acting as critical processors of transcriptional signals to define cellular identity [24] [25]. These elements, which include enhancers, promoters, silencers, and insulators, function by providing platforms for the binding of transcription factors (TFs) [24]. Their importance is highlighted by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) which show that many genetic variants linked to disease susceptibility, including those for pulmonary fibrosis, COPD, and asthma, fall within these non-coding genomic regions [24]. The mechanistic basis for this lies in the ability of CREs to integrate complex signals; they consist of clusters of relatively short transcription factor binding sites (typically 4–10 nucleotides) that can be flexibly arranged, allowing them to evolve rapidly and fine-tune gene expression with remarkable precision [24].

The dynamic nature of CRE activity is central to development and disease. During cell state transitions, such as the exit from naive pluripotency, enhancer landscapes are extensively rewired, with TF complexes like OCT4 and SOX2 binding and activating pluripotency-specific enhancers [25]. Furthermore, certain genomic regions carrying CREs demonstrate profound clinical significance. For instance, the super-enhancer region upstream of the MYC oncogene carries more inherited cancer risk than any other human genomic region and is required for intestinal regeneration after damage, establishing a direct genetic link between tissue repair and tumorigenesis [26]. This connection underscores why precise mapping and functional characterization of CREs is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental prerequisite for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted interventions.

Application Notes: Functional CRE Analysis in Disease Contexts

Discovery of Cell-Type Specific Enhancers for Gene Therapy

The development of gene therapies for monogenic diseases requires precise control of transgene expression, making the discovery of potent, cell-type specific enhancers paramount. A recent large-scale study targeting β-hemoglobinopathies established a direct enhancer discovery pipeline for this purpose [27]. Researchers compiled a library of ~15,000 candidate sequences derived from DNase I Hypersensitive Sites (DHSs) active during human erythropoiesis and cloned them into a lentiviral vector upstream of a minimal β-globin promoter driving GFP expression [27]. This library was transduced at low multiplicity of infection into HUDEP-2 cells (a human erythroid progenitor cell line), and cells were sorted based on GFP intensity (low, medium, high) [27].

Table 1: Key Outcomes from Large-Scale Erythroid Enhancer Screen

| Analysis Metric | Result | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Library Coverage | 97.8% of designed tiles recovered (14,668 fragments) | High-fidelity representation of candidate elements |

| Functional Elements | 897 tiles identified as potential enhancers (top 5% by effect); 6577 with positive effect | Vast functional landscape beyond canonical elements |

| Motif Enrichment | Enhancer tiles enriched for GATA1 and TAL1 motifs (q<1e-03) | Confirms known erythroid transcription factors |

| Silencing Elements | 481 tiles identified as potential silencers; enriched for SP family motifs | Many developmentally active DHSs may function as repressors |

| Epigenetic Validation | Enhancer tiles showed significantly increased H3K27Ac, H3K4me1, GATA1/TAL1 binding (p<2.22e-16) | Biochemical confirmation of regulatory function |

A critical finding was that a substantial number of DHSs activating during erythroid differentiation displayed repressive functions, highlighting the dual regulatory potential of accessible chromatin regions [27]. The compact, potent enhancers discovered through this pipeline successfully replaced the canonical β-globin μLCR in a therapeutic vector for β-thalassemia, correcting the thalassemic phenotype in patient-derived hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) while increasing viral titers and transducibility [27]. This demonstrates a direct therapeutic application for CRE analysis.

Enhancer Deletion and Distance Manipulation for Therapeutic Gene Reactivation

An alternative to gene addition is the therapeutic reactivation of endogenous genes via enhancer deletion or genomic repositioning. The 'delete-to-recruit' approach uses CRISPR-Cas9 to remove the DNA segment separating a gene from its enhancer, effectively bringing them closer together to activate transcription [28]. This method has shown promise for treating sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia by reactivating the fetal globin gene—a "backup engine" that can compensate for the faulty adult globin gene in these patients [28].

This strategy was validated in human blood stem cells from both healthy donors and sickle cell patients, indicating its potential to generate a continuous supply of healthy red blood cells [28]. By editing the genomic distance to an enhancer rather than the gene itself, this method may offer a safer, more cost-effective alternative to existing gene therapies, potentially reducing off-target risks and increasing accessibility [28].

Quantitative Analysis of CRE Transcriptional Activity

Accurately identifying functional CREs among accessible chromatin regions remains challenging. A newly developed method, KAS-ATAC-seq, simultaneously profiles chromatin accessibility and transcriptional activity of CREs by quantitatively measuring single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) levels within ATAC-seq peaks [29]. This integration is crucial because many accessible CREs are transcriptionally poised or inactive.

KAS-ATAC-seq enables the identification of Single-Stranded Transcribing Enhancers, which are highly enriched with nascent RNAs and TF binding sites that define cellular identity [29]. When applied to mouse neural differentiation, this method successfully identified immediate-early activated CREs in response to retinoic acid treatment, revealing the involvement of specific TFs like ETS and YY1 [29]. This provides researchers with a powerful tool to move beyond chromatin accessibility maps toward functional characterization of active regulatory elements in development and disease.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Functional Screening of CRE Libraries

This protocol describes a method for screening thousands of candidate CREs for enhancer activity in a therapeutically relevant chromosomal context, adapted from a study that identified erythroid-specific enhancers [27].

Materials:

- Library of candidate CREs (e.g., tiled DHSs)

- Lentiviral vector backbone with minimal promoter and reporter gene (e.g., GFP)

- HUDEP-2 cells (or other therapeutically relevant cell line)

- Facility for BSL-2 work

- FACS sorter

- High-throughput sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Library Design and Cloning:

- Source candidate sequences from cell-type specific epigenomic atlas (e.g., DNase I Hypersensitive Sites).

- Tile each DHS into overlapping oligos (median size ~200 bp).

- Clone the oligo library into a lentiviral vector upstream of a minimal promoter (e.g., 169 bp β-globin promoter) driving a reporter gene (e.g., GFP).

- Include chromatin insulators in the vector to minimize positional effects.

Cell Culture and Transduction:

- Culture HUDEP-2 cells in erythroid differentiation conditions.

- Transduce cells at a low MOI (e.g., 0.4) to ensure single viral integration per cell.

- Incubate for 5 days to allow transgene expression.

Cell Sorting and Binning:

- Harvest transduced cells and resuspend in FACS buffer.

- Sort transduced cells (GFP-positive) into three equiproportional population bins (e.g., 5% each) across the GFP intensity spectrum: GFP low, medium, and high.

- Include untransduced cells as a negative control.

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Extract genomic DNA from each sorted bin.

- Amplify and sequence the integrated lentiviral cassettes to determine CRE representation in each bin.

- Compute relative enhancer tile frequencies in each GFP bin.

- Use a statistical framework to estimate the latent effect of each sequence on expression by modeling tile frequencies through maximum likelihood.

- Rank each enhancer tile based on its estimated effect value.

Troubleshooting:

- Ensure high library coverage (>800 integrations per element) to overcome positional effect variegation and achieve robust replicate concordance (r > 0.9).

- Validate top-ranking enhancer tiles in secondary functional assays.

Protocol 2: 'Delete-to-Recruit' Enhancer Recruitment for Gene Activation

This protocol describes a CRISPR-Cas9-based method to reactivate endogenous genes by altering their proximity to enhancers, applicable to blood disorders and other diseases with compensatory gene candidates [28].

Materials:

- CRISPR-Cas9 system (Cas9 protein and sgRNA)

- sgRNAs designed to flank the intervening region between enhancer and target gene

- Primary human hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells

- Electroporation system

- Culture media for HSPC maintenance and differentiation

Procedure:

- Target Selection and sgRNA Design:

- Identify a potent enhancer and the target gene to be activated (e.g., fetal globin enhancer and HBG genes).

- Design two sgRNAs that flank the DNA segment separating the gene from its enhancer.

Cell Transfection:

- Isolate HSPCs from donor or patient.

- Electroporate cells with Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes containing the two sgRNAs.

- Include non-targeting sgRNA as a negative control.

Analysis of Editing and Gene Activation:

- 72 hours post-electroporation, extract genomic DNA to confirm deletion efficiency by PCR.

- Culture edited HSPCs in erythroid differentiation conditions for 14-21 days.

- Measure target gene expression (e.g., fetal globin mRNA) by RT-qPCR.

- Assess functional protein levels (e.g., hemoglobin electrophoresis).

- Monitor differentiation efficiency and cell surface markers.

Validation:

- Confirm deletion of the intervening region by Sanger sequencing.

- Verify increased expression of the target gene at both mRNA and protein levels.

- Assess specific phenotypic correction (e.g., sickling assay for sickle cell disease).

Visualizing Workflows and Mechanisms

Enhancer Screening and Validation Workflow

Delete-to-Recruit Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRE Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Profiling | ATAC-seq, DNase-seq, ChIP-seq (H3K27ac, H3K4me1) | Maps accessible chromatin and histone modifications to identify candidate CREs [24] [29] |

| Functional Screening | Lentiviral MPRA vectors, GFP reporter, FACS | High-throughput testing of thousands of candidate CREs for enhancer activity [27] |

| Genome Editing | CRISPR-Cas9, sgRNAs, Electroporation system | Deletion of specific CREs or genomic regions to test function [28] [26] |

| Transcriptional Profiling | KAS-ATAC-seq, RNA-seq, scRNA-seq | Measures transcriptional output and identifies transcribed enhancers [29] |

| Cell Models | HUDEP-2 (erythroid), mESCs, Primary HSPCs | Therapeutically relevant cell types for functional validation [27] [25] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | PRINT, seq2PRINT, Peak callers, Motif analysis | Computational analysis of multi-scale footprints and regulatory logic [30] |

Constructing Multi-Layered Knowledge Networks for Drug Repurposing