Gene Regulatory Networks in EvoDevo: A Practical Framework for Evolutionary Developmental Biology and Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) framework as a powerful tool for evolutionary developmental biology (EvoDevo).

Gene Regulatory Networks in EvoDevo: A Practical Framework for Evolutionary Developmental Biology and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) framework as a powerful tool for evolutionary developmental biology (EvoDevo). We explore how GRNs model developmental programs as networks of regulatory interactions that shape phenotypic diversity and constrain evolutionary trajectories. The content covers foundational concepts, modern methodological approaches using single-cell and functional genomics, troubleshooting for common research challenges, and validation through comparative analyses and functional testing. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource offers practical workflows for studying the molecular basis of phenotypic diversity while highlighting implications for understanding disease mechanisms and evolutionary innovation in biomedical contexts.

Understanding GRN Architecture: From Developmental Programs to Evolutionary Innovation

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) are abstract, computational representations of the complex interactions between genes and their regulators that control developmental processes [1]. In evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), GRNs provide a powerful framework for understanding how changes in regulatory logic drive the emergence of novel morphological structures and phenotypic diversity across species. A GRN model essentially projects the vast complexity of biological regulation into a manageable network where nodes represent biological components (e.g., genes, transcription factors) and edges represent regulatory interactions (e.g., activation, repression) [1]. The core thesis of this research posits that decoding the architecture and dynamics of these networks is fundamental to unraveling the mechanistic basis of development and evolution. By mapping developmental programs onto network models, researchers can transition from descriptive catalogs of gene expression to quantitative, predictive models of cellular fate and function, thereby illuminating the fundamental principles governing biological systems.

Fundamental Concepts of Gene Regulatory Networks

Definition and Biological Significance

A Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) is not a physical entity but a conceptual model that describes the functional interactions between molecular regulators that govern cell-specific gene expression programs [1]. At its core, a GRN encapsulates the logic of cellular regulation, defining how information encoded in the genome is interpreted and executed to direct developmental processes, maintain homeostasis, and mediate environmental responses. The biological significance of GRNs is profound; they represent the functional circuitry of the cell, whose structure and dynamics determine phenotypic outcomes. Disruptions in GRN architecture—such as rewiring of connections or malfunctioning nodes—are implicated in the pathogenesis of complex diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and heart failure, underscoring their critical role in health and disease [1].

Nodes and Edges: The Basic Vocabulary of GRNs

The architecture of a GRN is defined by two fundamental elements: nodes and edges.

- Nodes: In a typical GRN, nodes represent biological entities such as genes, transcription factors, signaling molecules, or non-coding RNAs [1]. The state of a node (e.g., its expression level or activity) is a dynamic property that changes in response to regulatory inputs.

- Edges: Edges represent the causal or physical interactions between nodes. These interactions can be directed (indicating the flow of influence) and signed (positive for activation, negative for repression) [1]. Edges can embody various biological relationships, including transcription factor binding to a gene's promoter, functional association from gene co-expression, or post-translational modification.

Table 1: Types of Nodes and Edges in GRN Models

| Element | Type | Biological Meaning | Example Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node | Gene | A DNA sequence encoding a functional product | RNA-seq, Microarrays [1] |

| Node | Transcription Factor (TF) | A protein that binds DNA to regulate transcription | ChIP-seq, Motif Databases [1] [2] |

| Node | Signaling Molecule | A protein involved in inter-/intra-cellular signaling | Protein-Protein Interaction Data [2] |

| Edge | Transcriptional Regulation | A TF binds to and regulates a target gene's transcription | ChIP-seq, TRN Databases [1] |

| Edge | Functional Association | Genes are co-expressed or participate in the same pathway | Gene Co-expression, KEGG [1] |

Computational Modelling Paradigms for GRNs

Multiple computational paradigms exist for constructing and analyzing GRNs, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and suitable applications. The choice of model depends on the biological question, the type and scale of available data, and the desired level of mechanistic detail [1] [2].

Structural and Graph-Based Models

Graph models represent the GRN as a set of nodes connected by edges, focusing primarily on the topology of interactions [1]. This approach is highly intuitive and leverages the analytical power of graph theory to identify key network properties. Analysis might reveal hub genes (high degree), network motifs (recurring small subgraphs), and assess the overall robustness of the network [1]. These models are often inferred from steady-state gene expression data (e.g., microarrays, RNA-seq) or integrated from existing interaction databases.

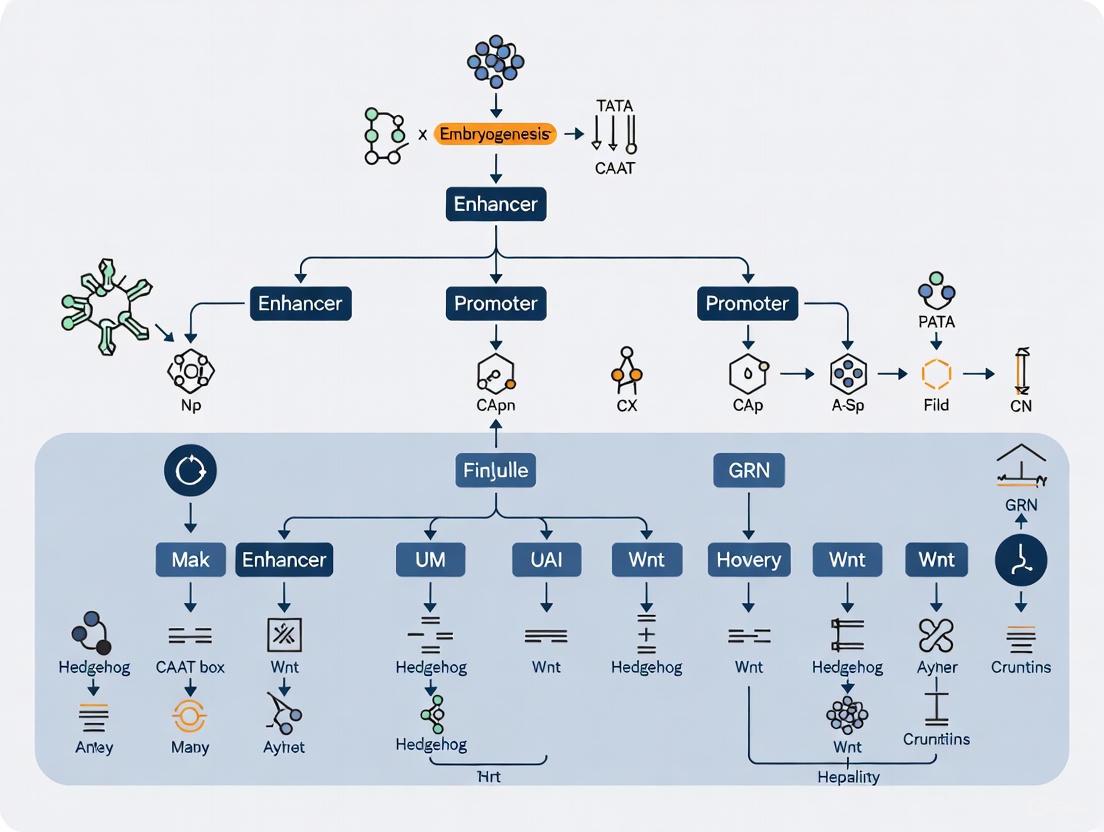

Diagram 1: Simple GRN Structure. This graph shows a hierarchical regulatory structure with a central transcription factor (TF A) acting as a hub.

Dynamic Models

Dynamic models simulate how the state of the network evolves over time, crucial for modeling developmental processes.

- Boolean Networks: A simplification where node states are binary (ON/OFF or 1/0). The state of a node at the next time step is determined by a logical Boolean function of its inputs [1]. While abstract, they can capture the essential logic of a system and are computationally efficient for large networks.

- Differential Equations (ODEs/PDEs): These models use continuous quantities and rates of change to describe the precise concentrations of molecular species [2]. They are highly accurate and mechanistic but require many parameters and are computationally intensive, making them suitable for smaller, well-characterized systems.

- Bayesian Networks (BNs): These are probabilistic graphical models that represent the joint probability distribution over network variables [2]. BNs are powerful for inferring networks from observational data and handling stochasticity and uncertainty, though they often represent statistical dependencies rather than direct causality.

Table 2: Comparison of Common GRN Modelling Paradigms

| Modelling Paradigm | Key Principle | Data Requirements | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Model | Network topology & structure | Steady-state data, interaction databases | Intuitive, scalable, vast theory toolkit | No dynamics, often static representation |

| Boolean Network | Logical (ON/OFF) rules | Prior knowledge of interactions, time-series | Computationally lightweight, captures logic | Oversimplified, lacks quantitative detail |

| Bayesian Network | Probabilistic dependencies | Observational data (e.g., expression) | Handles noise & uncertainty, infers from data | Can infer non-causal links, computationally hard |

| Differential Equations | Continuous kinetics & rates | Quantitative time-series data, parameters | Highly accurate, predictive, mechanistic | Parameter-heavy, not scalable to large networks |

Diagram 2: Core Regulatory Circuit. This diagram illustrates a simple circuit where an extracellular signal activates a transcription factor, which then regulates two target genes using different modeling abstractions: a Boolean rule and an Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE).

Computational Methods for GRN Inference and Reconstruction

The process of inferring a GRN from high-throughput data is a central challenge in computational biology.

Data Types for GRN Inference

Modern GRN inference leverages diverse omics data, often through integrative analysis [2].

- Genomics and Epigenomics: Data from ChIP-seq identifies transcription factor binding sites and histone modifications, providing direct evidence for potential regulatory edges [1]. ATAC-seq reveals chromatin accessibility, indicating regulatory regions.

- Transcriptomics: Data from RNA-seq and microarrays measures gene expression levels across different conditions, time points, or cell types, which is the primary data source for inferring functional relationships [1] [2].

- Proteomics: Data from mass spectrometry can quantify protein abundances and post-translational modifications, adding a crucial layer beyond mRNA expression.

Machine Learning and AI-Based Methods

Machine learning (ML) has dramatically advanced the field of GRN inference [2] [3].

- Supervised Learning: These methods require a training set of known regulator-target pairs. Features are derived from the data (e.g., correlation, sequence motifs), and a classifier is trained to predict new interactions [3].

- Unsupervised Learning: Approaches like clustering group genes with similar expression profiles, potentially identifying co-regulated modules. Correlation networks (e.g., WGCNA) are a common unsupervised technique [2].

- Deep Learning: Modern methods employ deep neural networks, including Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and autoencoders, to learn complex, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data, often leading to superior inference performance [3]. These models can integrate heterogeneous data types and capture hierarchical features.

Diagram 3: GRN Inference Workflow. A generalized pipeline for reconstructing a Gene Regulatory Network from raw data to a validated model.

Experimental Protocols for GRN Mapping

Protocol 1: Inferring a Co-Expression Network from RNA-seq Data

This protocol generates a hypothesis-driven GRN from transcriptomic data.

- RNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing: Extract total RNA from samples across multiple conditions/time points. Prepare sequencing libraries (e.g., using Illumina TruSeq kit) and perform high-throughput sequencing [2].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Align raw sequencing reads to a reference genome using tools like HISAT2 or STAR. Quantify gene expression levels (e.g., counts per gene) using featureCounts or similar software [2].

- Network Inference using GENIE3 (Tree-Based Method)

- Input: Normalized gene expression matrix (genes x samples).

- Procedure: Using the GENIE3 software (or a similar tool like GRNBoost2), for each gene, a tree-based model (e.g., Random Forest) is trained to predict its expression based on the expression of all other potential regulators. The importance of each regulator is computed.

- Output: A ranked list of potential regulatory links for all genes in the network [2].

- Network Construction and Analysis: Select the top-scoring links for each gene based on a chosen precision cutoff to construct the adjacency matrix of the network. Visualize and analyze the network using Cytoscape or custom scripts in R/Python to identify modules and hubs.

Protocol 2: Validating a Regulatory Edge Using CRISPR-Cas9 and qPCR

This protocol functionally validates a predicted interaction between a transcription factor (TF) and its target gene.

- Design and Synthesis of gRNA: Design a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the coding sequence or promoter of the TF gene. Synthesize the sgRNA and complex with Cas9 protein to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

- Cell Transfection and Knockout: Introduce the RNP complex into relevant cell lines using electroporation. Include a control group transfected with a non-targeting sgRNA.

- Confirming Knockout Efficiency: 72 hours post-transfection, harvest cells. Extract genomic DNA and perform a T7 Endonuclease I assay or Sanger sequencing to assess indel formation at the target site. Extract total RNA and synthesize cDNA.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Perform qPCR using SYBR Green chemistry and primers specific to the predicted target gene(s) of the TF. Normalize expression levels to housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB).

- Data Analysis: Use the ∆∆Ct method to calculate the fold-change in expression of the target gene in the TF-knockout group compared to the control. A significant change (e.g., downregulation for an activator) validates the regulatory edge.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for GRN Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in GRN Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted gene knockout or editing for functional validation | Testing necessity of a TF for target gene expression [2] |

| ChIP-seq Kit | Genome-wide mapping of transcription factor binding sites | Providing physical evidence for a regulatory edge [1] |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Preparation of samples for transcriptome sequencing | Generating gene expression data for network inference [2] |

| siRNA/shRNA Library | High-throughput gene knockdown | Systematic perturbation of network nodes [2] |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay | Measuring transcriptional activity of a promoter | Testing if a TF activates/represses a specific target |

Visualization and Analysis of GRN Models

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting complex GRN models. The DOT language from Graphviz is a widely used standard for this purpose. The following script demonstrates how to create a publication-quality GRN diagram, incorporating styling rules for color contrast and layout as specified in the core requirements.

Diagram 4: Detailed GRN with Multiple Interactions. This network incorporates different node types (signal, TFs, genes, miRNA) and edge types (activation, repression, indirect effect, miRNA silencing), styled for clarity.

The mapping of developmental programs onto formal network models of nodes, edges, and regulatory logic represents a paradigm shift in evolutionary developmental biology. GRNs provide a powerful, abstract language to describe the complex, dynamic, and multi-scale processes that govern cellular fate and function. The integration of high-throughput omics data with sophisticated computational methods—ranging from graph theory to modern deep learning—is enabling the reconstruction of increasingly accurate and predictive models. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to deepen our understanding of the fundamental principles of development, the molecular basis of disease, and the evolutionary mechanisms that generate morphological diversity.

The evolution of animal body plans is fundamentally a systems-level process governed by changes in the developmental gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that control embryogenesis. These networks—comprising transcription factors, signaling molecules, and the cis-regulatory elements that control their expression—represent the fundamental computational architecture that transforms genomic information into morphological structures [4] [5]. The hierarchical organization of GRNs imposes specific constraints on evolutionary change while simultaneously creating opportunities for innovation through particular forms of genetic rewiring. Understanding this duality—how GRNs simultaneously constrain and facilitate evolutionary change—provides critical insights into major evolutionary patterns, including hierarchical phylogeny, morphological stasis, and the emergence of evolutionary novelties [4].

The GRN concept has emerged as a powerful unifying framework for evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), offering a mechanistic explanation for the relationship between genotypic and phenotypic variation. As physical entities encoded in the genome, GRNs have a defined structure that determines their function, and alterations to this structure necessarily change developmental processes and their phenotypic outcomes [4] [6]. This perspective enables researchers to move beyond descriptive accounts of evolutionary change to causal explanations rooted in the regulatory logic of developmental systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, this GRN-centered approach provides a predictive framework for understanding how genetic variation translates to phenotypic variation across different biological contexts.

The Hierarchical Structure of Developmental GRNs

Organizational Principles of GRN Architecture

Developmental GRNs exhibit a distinctive hierarchical organization that profoundly influences their evolutionary behavior. At the highest level, GRNs operate through a temporal sequence of regulatory phases that progressively elaborate the body plan from broad domains to specific cell types [4]. This sequential hierarchy begins with the establishment of specific regulatory states in spatial domains of the developing embryo, effectively mapping out the design of the future body plan through differential regulatory potential. Subsequent GRN apparatus then operates at progressively finer scales to further specify regional identity, ultimately culminating in precisely confined regulatory states that direct the deployment of differentiation gene batteries responsible for producing tissue-specific structures and functions [4] [7].

This hierarchical structure creates important evolutionary constraints through what has been described as a "bow-tie" architecture, where diverse upstream inputs converge on highly conserved kernel subcircuits that then diverge to various downstream outputs. The core regulatory kernels—which execute critical patterning functions—exhibit remarkable evolutionary stability, while peripheral elements show greater flexibility [4] [5]. This mosaic architecture explains why certain aspects of development are deeply conserved across vast evolutionary distances while others evolve rapidly. The network topology typically follows a hierarchical scale-free structure characterized by a few highly connected nodes (hubs) and many poorly connected nodes, a configuration that evolves through preferential attachment of duplicated genes to more highly connected genes [5].

Network Motifs as Functional Building Blocks

At the local level, GRNs contain characteristic repetitive sub-networks known as network motifs that perform specific regulatory functions [5]. The most abundant motif in GRNs across species is the feed-forward loop, which consists of three nodes connected in a specific pattern that allows for temporal delay responses, noise filtering, and pulse generation. Other common motifs include feedback loops and bi-fan patterns. These motifs are often considered "optimal designs" for particular regulatory tasks, though debate continues about whether their abundance reflects adaptive optimization or emerges as a byproduct of network growth and evolution [5].

Table: Common Network Motifs in Gene Regulatory Networks and Their Proposed Functions

| Motif Type | Structural Description | Proposed Functional Role | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feed-forward loop | Three nodes where X regulates Y, and X and Y both regulate Z | Creates temporal delays; filters transient noise; enables fold-change detection | Accelerates metabolic transitions; provides resistance to signaling fluctuations |

| Feedback loop | Output affects its own regulation through a chain of interactions | Enables bistability, oscillations, or homeostasis | Stabilizes cell fate decisions; maintains regulatory states |

| Single-input module | Single regulator controls multiple targets | Coordinates expression of gene batteries | Facilitates co-regulation of functionally related genes |

| Dense overlapping regulons | Multiple regulators control multiple targets | Integrates diverse regulatory inputs | Enables complex combinatorial control |

Mechanisms of GRN Evolution: Molecular Drivers of Change

Cis-Regulatory Evolution as a Primary Mechanism

The evolutionary alteration of GRNs occurs predominantly through changes in cis-regulatory modules (CRMs)—the non-coding DNA sequences that control the spatial and temporal expression of genes [4]. These modules contain binding sites for transcription factors that combinatorially determine when and where genes are expressed, effectively hardwiring the functional linkages within GRNs. Cis-regulatory evolution can proceed through multiple molecular mechanisms with distinct functional consequences:

- Internal sequence changes: The appearance or disappearance of transcription factor binding sites within existing cis-regulatory modules can produce qualitative changes in gene expression patterns, potentially co-opting genes into new developmental contexts [4].

- Contextual changes: Genomic rearrangements that alter the physical disposition of entire cis-regulatory modules—including translocations, deletions, or duplications—can dramatically rewire regulatory connections. Transposition of mobile elements carrying cis-regulatory modules may represent a particularly rapid mechanism of GRN evolution [4].

- Module duplication and divergence: Duplication of cis-regulatory modules followed by subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization can create new regulatory capacities while preserving ancestral functions [4].

Notably, cis-regulatory design exhibits considerable flexibility, with comparative studies showing that orthologous modules from distantly related species can produce identical expression patterns despite extreme differences in transcription factor binding site order, number, and spacing [4]. This design flexibility provides a rich substrate for evolutionary change while buffering core regulatory functions.

Case Study: GRN Rewiring in Amphioxus Nodal Signaling

A compelling example of GRN evolution comes from studies of the Nodal signaling pathway in cephalochordate amphioxus, which controls dorsal-ventral and left-right axis patterning [8]. In most deuterostomes, this pathway operates through a conserved GRN orchestrated by Nodal, Gdf1/3, and Lefty. However, amphioxus exhibits a strikingly rewired network architecture resulting from specific genomic events:

- Gene duplication and translocation: The ancestral Gdf1/3 gene underwent tandem duplication in the cephalochordate lineage, with one duplicate (Gdf1/3-like) translocating to the Lefty genomic locus [8].

- Regulatory hijacking: The translocated Gdf1/3-like gene appears to have hijacked enhancer elements from Lefty, resulting in coordinated expression of these two genes.

- Functional redeployment: The Gdf1/3-like gene assumed the axial patterning role of the ancestral Gdf1/3 gene, which lost its embryonic expression and became functionally dispensable for body axis formation [8].

- Compensatory evolution: Nodal evolved maternal expression in amphioxus, compensating for the loss of maternal Gdf1/3 contribution and becoming an indispensable maternal factor [8].

This case illustrates how GRN evolution can proceed through a series of molecular events—duplication, translocation, enhancer hijacking, and compensatory change—that collectively rewire network architecture while preserving overall system function. The co-expression of Gdf1/3-like and Lefty achieved through their shared regulatory region may provide developmental robustness, offering a selection-based hypothesis for this evolutionary trajectory [8].

Experimental Approaches for GRN Analysis

Workflows for GRN Construction

Constructing accurate GRN models requires integrated experimental strategies that combine detailed biological knowledge with systematic molecular profiling and functional validation [7]. A comprehensive workflow for GRN analysis typically includes these critical phases:

- Biological foundation: Detailed understanding of the developmental process, including fate maps, cell lineages, and inductive interactions [7].

- Regulatory state definition: Comprehensive identification of transcription factors, signaling molecules, and their expression patterns at specific developmental stages [7].

- Perturbation analysis: Systematic functional testing through gene knockout, knockdown, or overexpression to establish epistatic relationships [7].

- Cis-regulatory analysis: Identification and characterization of regulatory elements that control gene expression [7].

- Network integration: Synthesis of data into a coherent GRN model with predictive power [7].

The chick embryo has proven particularly valuable for GRN construction due to its accessibility for manipulation, well-characterized development, and phylogenetic position as a non-mammalian amniote [7]. Recent technical advances—including transcriptome analysis from small tissue samples, efficient gene perturbation strategies, and chromatin immunoprecipitation—have made rapid GRN construction feasible in this system [7].

Single-Cell Multi-Omic Methods for GRN Inference

Recent advances in single-cell technologies have revolutionized GRN analysis by enabling the reconstruction of regulatory networks at cellular resolution [9]. The emergence of single-cell multi-omic approaches—which simultaneously profile multiple molecular modalities in the same cell—has been particularly transformative:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq): Measures transcriptome-wide gene expression in individual cells [9].

- Single-cell ATAC-seq (scATAC-seq): Identifies accessible chromatin regions at single-cell resolution [9].

- Single-cell Hi-C (scHi-C): Captures chromatin conformation and three-dimensional genome architecture [9].

- Paired multi-omic methods: Platforms such as SHARE-seq and 10x Multiome simultaneously profile RNA expression and chromatin accessibility in the same cell [9].

These technological advances have spurred development of sophisticated computational methods for GRN inference that leverage different mathematical foundations:

Table: Computational Approaches for GRN Inference from Single-Cell Multi-Omic Data

| Methodological Foundation | Underlying Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based approaches | Identify co-expressed genes using measures of association (Pearson/Spearman correlation, mutual information) | Simple implementation; effective for initial hypothesis generation | Cannot distinguish direct vs. indirect regulation; limited directional information |

| Regression models | Model gene expression as a function of multiple predictor variables (TFs, CREs) | Interpretable coefficients indicate regulatory strength; handles multiple predictors | Unstable with correlated predictors; requires regularization with large predictor sets |

| Probabilistic models | Represent regulatory relationships as graphical models estimating the most probable network | Incorporates uncertainty; enables filtering and prioritization of interactions | Often assumes specific gene expression distributions that may not hold |

| Dynamical systems | Model system behavior over time using differential equations | Captures temporal dynamics and stochasticity; highly interpretable parameters | Complex for large networks; depends on prior knowledge; limited scalability |

| Deep learning models | Use neural networks to learn complex regulatory relationships from data | Highly flexible; can capture nonlinear relationships; versatile architectures | Requires large datasets; computationally intensive; limited interpretability |

Cutting-edge GRN research requires a sophisticated toolkit of research reagents and computational resources. The table below details essential materials and their applications in studying GRN evolution:

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for GRN Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Gene knockout, knock-in, and precise genome editing in model organisms | Enables functional testing of network components; species-specific efficiency variations |

| Morpholino oligonucleotides | Transient gene knockdown by blocking translation or splicing | Rapid screening tool; potential off-target effects require controls |

| scRNA-seq platforms (10x Genomics, SHARE-seq) | Single-cell transcriptome profiling with cellular resolution | Cellular throughput vs. sequencing depth tradeoffs; multi-omic capabilities |

| scATAC-seq reagents | Mapping accessible chromatin regions at single-cell resolution | Identifies potentially active regulatory elements; integration with scRNA-seq recommended |

| ChIP-seq antibodies | Genome-wide mapping of transcription factor binding and histone modifications | Antibody specificity critical; species compatibility limitations |

| Transgenic construct systems | Testing cis-regulatory module activity through reporter assays (e.g., GFP, LacZ) | Minimal promoter choice affects sensitivity; genomic position effects possible |

| PhyloCSF, CONSRAIR | Computational identification of conserved non-coding elements | Evolutionary conservation suggests functional importance |

| DESeq2, EdgeR | Computational tools for differential gene expression analysis | Handles various experimental designs; requires appropriate replicate numbers |

| LINCS, CellNet | Databases of reference gene expression signatures and regulatory networks | Provides comparative framework for network analysis |

Visualization of GRN Structure and Experimental Workflow

Hierarchical Organization of a Developmental GRN

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical structure of a typical developmental GRN, showing the progressive specification from broad territorial identity to terminal differentiation:

Experimental Workflow for GRN Construction

This workflow diagram outlines the key stages in empirical GRN construction, from initial biological characterization to functional validation:

The GRN perspective provides a powerful explanatory framework for understanding both constraints and opportunities in evolutionary trajectories. The hierarchical organization of developmental GRNs explains why certain aspects of morphology exhibit remarkable evolutionary stability while others display striking flexibility. The concentration of evolutionary change in cis-regulatory elements, particularly through mechanisms that alter the genomic context of regulatory modules, reveals how developmental systems can explore phenotypic space without compromising essential functions [4] [8].

For biomedical researchers and drug development professionals, the GRN concept offers valuable insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Many human diseases represent failures of developmental regulation, and understanding the GRN architecture underlying relevant developmental processes can identify critical control points for intervention. The conservation of network kernels across vast evolutionary distances suggests that model organism studies can provide profound insights into human biology, while species-specific network modifications highlight the importance of context in regulatory function.

Future research directions will likely focus on expanding GRN analysis to non-model organisms, integrating single-cell multi-omic data to achieve cellular-resolution networks, and developing more sophisticated computational models that can predict evolutionary outcomes from specific genetic changes. As these capabilities mature, the GRN framework will continue to bridge the gap between evolutionary theory and mechanistic developmental biology, providing a comprehensive understanding of how genetic variation produces phenotypic diversity through the rewiring of developmental programs.

Evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) has long sought to explain how drastic morphological innovations arise without the evolution of entirely new genetic blueprints. Research within the gene regulatory network (GRN) framework reveals that a predominant mechanism is the evolutionary repurposing of deeply conserved gene programs. This whitepaper examines compelling case studies from vertebrate limb development, highlighting how existing regulatory circuits have been spatially, temporally, and contextually co-opted to generate novel structures. We synthesize recent single-cell transcriptomic, functional genomic, and computational evidence to delineate the molecular mechanisms underlying this repurposing, with a focus on the origin of the bat wing. The findings underscore that significant phenotypic evolution is often achieved not through the creation of new genes, but through the innovative reuse of ancient genetic toolkits.

A central paradigm in evolutionary developmental biology is that the genetic programs governing the construction of body plans are deeply conserved across vast phylogenetic distances. This conservation presents a puzzle: how does substantial morphological diversity arise from seemingly similar genetic toolkits? The answer lies in understanding the structure and evolvability of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs)—the complex interplay of transcription factors, signaling pathways, and their cis-regulatory elements that control gene expression in time and space [10].

Evolutionary repurposing, or co-option, occurs when an existing GRN, or a sub-circuit within it, is deployed in a new developmental context, at a different time, or in a novel location to facilitate the emergence of a new trait. The vertebrate limb, with its remarkable diversity of forms—from the human hand and horse hoof to the bat wing and whale flipper—serves as a premier model for studying this process [11]. Its development is governed by a well-characterized GRN, allowing for detailed comparative analyses. This whitepaper explores how the repurposing of conserved proximal limb GRNs in the bat autopod, the alteration of regulatory landscapes in congenital disorders, and the functional shifts of enhancers in limb-reduced lineages provide powerful insights into the mechanisms of evolutionary change.

Core Concepts and Key Mechanisms

The repurposing of gene programs is not a singular event but a process enabled by specific genetic and regulatory architectures. The following mechanisms are particularly salient:

- Spatial Repurposing and Heterotopy: The deployment of a GRN typical of one anatomical region (e.g., the proximal limb) to a different region (e.g., the distal limb), resulting in novel morphology, as seen in bat wing membranes [12].

- Cis-Regulatory Evolution: Mutations in enhancer or promoter sequences that alter the expression pattern of a gene without affecting its core protein function, allowing for precise spatial, temporal, or quantitative shifts in gene activity. This is a key driver of morphological diversification [13] [14].

- Modularity and Sub-circuit Co-option: GRNs are often modular, with discrete sub-circuits controlling specific developmental tasks. These modules can be independently co-opted. The overlap between the limb and phallus GRNs is a prime example, where shared enhancers can be selectively inactivated in one context but retained in another [15].

- Post-Transcriptional Diversification: Alternative splicing dynamically regulates mRNA diversity during limb development, providing an additional layer of control for tweaking gene dosage and protein function in evolving morphologies [16].

Case Study 1: Bat Wing Development and the Repurposing of a Proximal Limb Program

The evolution of powered flight in bats required the transformation of the mammalian forelimb into a wing, characterized by hyper-elongated digits and a connecting wing membrane (chiropatagium). A landmark 2025 single-cell RNA sequencing study by [12] provides a molecular resolution view of this innovation.

Experimental Methodology and Workflow

Objective: To identify the cellular origins and molecular mechanisms underlying chiropatagium formation in the bat (Carollia perspicillata) and compare them to standard mammalian limb development in the mouse.

Key Experimental Steps:

- Tissue Collection and Single-Cell Preparation: Forelimbs (FLs) and hindlimbs (HLs) were collected from bat and mouse embryos at equivalent developmental stages spanning critical periods of digit formation and separation (e.g., mouse E11.5-E13.5; bat CS15-CS17).

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): Dissociated limb cells were subjected to scRNA-seq using a standard platform (e.g., 10x Genomics). An interspecies single-cell transcriptomic limb atlas was generated by integrating the bat and mouse data using the Seurat v3 integration tool.

- Cluster Annotation and Lineage Identification: Cell clusters were identified based on unbiased transcriptomic signatures and annotated using known marker genes for major lineages: lateral plate mesoderm (LPM)-derived cells (e.g., chondrogenic, fibroblastic), ectoderm-derived cells, and muscle cells.

- Micro-dissection and Specialized Sequencing: The chiropatagium was micro-dissected from bat embryos at a later stage (CS18). scRNA-seq was performed on these cells, and their transcriptional identity was traced by label transfer to the reference FL LPM dataset.

- Functional Validation via Transgenesis: The key transcription factors MEIS2 and TBX3 were ectopically expressed in the distal limb of transgenic mouse embryos to test their sufficiency in recapitulating molecular and morphological features of the bat wing.

- Apoptosis Assays: Cell death in bat limb interdigital tissues was assessed using LysoTracker staining and immunofluorescence for cleaved caspase-3.

The following workflow diagram summarizes this experimental pipeline:

Key Findings and Data

Contrary to the long-standing hypothesis that the chiropatagium persists due to suppressed apoptosis, the study revealed that interdigital cell death occurs similarly in both bat and mouse, and in both bat FLs and HLs [12]. Instead, the chiropatagium was found to originate from specific fibroblast populations (clusters 7 FbIr, 8 FbA, 10 FbI1) that are independent of the apoptosis-associated interdigital cells.

Crucially, these distal chiropatagium fibroblasts express a gene program canonically associated with the specification and patterning of the early proximal limb, including high levels of the transcription factors MEIS2 and TBX3 [12]. This represents a clear case of spatial repurposing. Ectopic expression of MEIS2 and TBX3 in the distal mouse limb was sufficient to activate bat wing-related genes and induce phenotypic changes such as digit fusion, confirming the functional role of this co-opted program.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Bat Wing scRNA-seq Study [12]

| Parameter | Finding in Bat vs. Mouse | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Composition | High conservation of major cell clusters (LPM, ectoderm, muscle). | Overall limb development program is deeply conserved. |

| Apoptosis (Cluster 3 RA-Id) | No significant difference in pro-/anti-apoptotic gene expression. | Chiropatagium persistence is not due to inhibited cell death. |

| Chiropatagium Cell Origin | Primarily fibroblast clusters 7 FbIr, 8 FbA, 10 FbI1. | Identifies the specific progenitor population. |

| Key TFs in Chiropatagium | High expression of MEIS2, TBX3 (normally proximal). | Evidence for spatial repurposing of a proximal limb program. |

| Transgenic Mouse Phenotype | Ectopic MEIS2/TBX3 led to digit fusion, gene expression changes. | Functional validation of the repurposed program's sufficiency. |

Case Study 2: Regulatory Landscapes and Congenital Limb Disorders

The repurposing of regulatory elements can also lead to disease when disrupted. Historical "genetic cold cases" of congenital limb disorders in humans and mice have been solved by uncovering mutations in the complex regulatory landscapes controlling limb GRNs [13].

The Ulnaless Mutation and Hoxd Regulation

The Ulnaless (Ul) mutation in mice, a dominant allele causing severe zeugopod (forearm) defects, was mapped to the HoxD gene cluster. Molecular investigation revealed it to be a genomic inversion that repositioned the HoxD cluster within its regulatory landscape [13]. In wild-type limb development, the HoxD cluster is regulated in a bimodal fashion: zeugopod-patterning enhancers are located on one side of the cluster, while autopod (hand/foot)-patterning enhancers are on the other. The Ul inversion disrupted this topology, leading to the ectopic expression of distal Hoxd13 in the zeugopod domain, where it interferes with normal zeugopod development. This case demonstrates how the precise spatial control of GRN components is critical and how its disruption effectively "repurposes" a distal gene in a proximal context with pathological consequences.

Table 2: Analysis of Solved Congenital Limb Disorder "Cold Cases" [13]

| Disorder/Mutation | Gene/Genomic Locus | Molecular Lesion | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ulnaless (Ul) | HoxD cluster | Genomic inversion | Ectopic distal Hoxd13 expression in zeugopod, causing mesomelic dysplasia. |

| Various Mesomelic Dysplasias (Human) | SHH (via ZRS enhancer) | Point mutations/CNVs in ZRS | Altered long-range regulation of SHH, affecting limb patterning. |

| Laurin-Sandrow Syndrome | LMX1B | Point mutations | Altered protein function affecting dorsal-ventral limb patterning. |

Case Study 3: Limb Reduction in Squamates and Enhancer Tinkering

The evolution of limb loss in snakes provides a counterpoint to the bat's gain of a novel structure, demonstrating how the same GRN components can be selectively inactivated.

Limb vs. Phallus Enhancer Conservation

Despite the absence of limbs for over 100 million years, the genomes of snakes show surprising conservation of many ancient tetrapod limb enhancers [15]. This is explained by the discovery of substantial overlap between the GRNs controlling limb and phallus development. Many of these conserved enhancers are bifunctional, also driving gene expression in the developing genital tubercle. Purifying selection has maintained their sequence integrity for their essential role in genital development, even as their limb function became obsolete. A key exception is the ZRS (Zone of Polarizing Activity Regulatory Sequence), an extremely limb-specific enhancer for Sonic hedgehog (Shh). The ZRS is highly diverged in snakes and has lost its function, as shown by its inability to drive limb expression in transgenic mouse assays [15]. This illustrates a principle of evolutionary repurposing: GRN components with pleiotropic functions are constrained, while highly specific ones can be freely lost or co-opted.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

The following table catalogs key reagents and methods critical for research in this field, as derived from the cited studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Gene Program Repurposing

| Reagent / Method | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq) | High-resolution profiling of cell populations and transcriptional states. | Constructing a cross-species limb cell atlas to identify novel populations [12]. |

| Lineage Tracing (Label Transfer) | Computational projection of cell identities from one dataset to a reference. | Identifying the origin of chiropatagium cells in the broader limb dataset [12]. |

| Transgenic Animal Models | Functional validation of gene/enhancer function via ectopic expression or CRISPR/Cas9 knockout. | Testing the role of MEIS2/TBX3 in mouse digit morphology [12]. |

| LysoTracker / Cleaved Caspase-3 IHC | Staining for lysosomal activity and apoptosis, respectively. | Visualizing cell death patterns in developing bat interdigital webbing [12]. |

| ATAC-Seq | Genome-wide profiling of open chromatin to identify active regulatory elements. | Comparing the regulatory genome of mouse and pig limb buds [14]. |

| rMATS Software | Computational tool for detecting differential alternative splicing from RNA-seq data. | Identifying dynamic splicing events in developing mouse and opossum limbs [16]. |

| Evolutionary Rate Calculation (e.g., for Gene Expression) | Statistical models to infer the pace of gene expression evolution. | Determining that fungal spore germination genes evolve rapidly [17]. |

Integrated Discussion: Synthesis and Future Directions

The case studies presented herein converge on a unifying principle: the evolution of form is profoundly shaped by the modularity, deployability, and regulatory complexity of deeply conserved GRNs. The bat wing did not require new genes, but a novel deployment of the proximal limb program (MEIS2, TBX3) in the distal limb. The limbless snake body plan was achieved not by discarding the entire limb GRN, but by selectively degrading a highly specific enhancer (ZRS) while preserving bifunctional ones. Congenital disorders often arise from mutations that corrupt the precise regulatory logic of these networks, leading to the misexpression and effective "mis-repurposing" of genes.

These insights were enabled by technological advances, particularly single-cell omics and functional genomics, which allow us to move from correlative observations to causative mechanisms. Future research will increasingly focus on:

- Multi-omic Integration: Combining scRNA-seq with ATAC-seq (scATAC-seq) and chromatin conformation capture (Hi-C) in the same cells to directly link regulatory element activity to gene expression and higher-order chromatin structure.

- Computational Modeling of GRNs: Using the data from these assays to build predictive mathematical models of limb GRNs, allowing in silico testing of how perturbations lead to novel morphologies [10].

- Exploring Post-Transcriptional Roles: Further investigation into how alternative splicing [16] and other post-transcriptional mechanisms contribute to the fine-tuning of gene dosage and protein diversity in evolving structures.

Visualizing a Repurposed Gene Regulatory Network

The core finding of the bat wing study—the repurposing of a proximal gene program in a distal location—can be summarized in the following GRN diagram. This illustrates the key transcriptional regulators and their shifted spatial context.

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) represent the fundamental architectural blueprint of biological systems, governing cellular differentiation, organismal development, and evolutionary processes. While traditionally studied in animal model systems, GRN analysis is increasingly transcending zoocentric boundaries to reveal conserved and divergent principles across plants, fungi, protists, and bacteria. This technical review provides a comprehensive framework for GRN research across biological kingdoms, integrating comparative evolutionary developmental biology with practical methodological guidance. We present standardized protocols for GRN reconstruction, quantitative comparative analyses of network properties, and visualization of cross-kingdom regulatory principles. By synthesizing current evidence from diverse lineages, this whitepaper establishes GRNs as a universal conceptual framework for understanding the evolution of biological complexity and offers researchers practical tools for its application in both basic science and pharmaceutical development.

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) comprise collections of molecular regulators that interact with each other and with other substances in the cell to govern gene expression levels of mRNA and proteins, thereby determining cellular function and identity [5]. The GRN concept has revolutionized evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) by providing a mechanistic framework for understanding how inherited developmental programs translate genotypic changes into phenotypic consequences [6]. Rather than being blank slates upon which natural selection acts arbitrarily, developmental mechanisms encoded in GRNs play an integral role in shaping phenotypic diversity and determining evolutionary trajectories across all biological kingdoms [6].

Traditional GRN research has predominantly focused on zoological models, but recent advances in genomic technologies and comparative biology have revealed that the fundamental principles of GRN architecture and function extend far beyond the animal kingdom. The core structure of GRNs—comprising genes as "nodes" and their molecular interactions as "edges"—represents a universal biological paradigm [6] [5]. This whitepaper synthesizes current knowledge of GRN biology across the spectrum of life, providing researchers with both theoretical context and practical methodologies for investigating regulatory networks in diverse biological systems.

Theoretical Framework: GRN Architecture and Evolutionary Dynamics

Core GRN Components and Network Theory

At their most fundamental level, GRNs consist of two primary components: nodes (genes and their products) and edges (the regulatory interactions between them) [6]. These networks exhibit a hierarchical scale-free topology characterized by a few highly connected nodes (hubs) and many poorly connected nodes, a structure that appears conserved across biological kingdoms [5]. This organization has profound implications for evolutionary dynamics, as it allows most genes to exhibit limited pleiotropy while operating within specialized regulatory modules [5].

GRNs typically contain repetitive topological patterns known as network motifs that appear more frequently than would be expected in random networks [5]. These motifs include:

- Feed-forward loops: Where node A regulates node B, and both A and B regulate node C

- Feedback loops: Where nodes regulate themselves directly or indirectly, creating cyclic chains

- Single-input modules: Where a single regulator controls multiple target genes

The enrichment of these motifs suggests they may represent "optimal designs" for specific regulatory purposes, though non-adaptive explanations for their abundance also exist [5].

Mechanisms of GRN Evolution

GRNs evolve through two primary mechanisms that can operate simultaneously: changes in network topology (addition or subtraction of nodes or entire modules) and changes in interaction strength between existing nodes [5]. Topological changes occur through gene duplication and divergence, followed by either neofunctionalization or subfunctionalization of regulatory elements. Interaction strength evolves through mutations in cis-regulatory elements or trans-acting factors that alter binding affinity or expression dynamics.

A compelling example of GRN evolution comes from the Nodal signaling pathway in cephalochordate amphioxus, where the ancestral Gdf1/3 gene has been functionally replaced by its duplicate, Gdf1/3-like, through what appears to be an enhancer hijacking event [8]. This rewiring involved the translocation of the Gdf1/3 duplicate to the Lefty locus, creating a new gene pair that enabled co-expression of these developmentally linked genes [8]. Simultaneously, Nodal acquired a novel maternal role to compensate for the loss of maternal Gdf1/3 expression, demonstrating how GRN evolution can involve coordinated changes across multiple network components [8].

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Comparative GRN Analysis Across Biological Kingdoms

| Metric | Typical Range in Animals | Typical Range in Plants | Typical Range in Fungi | Typical Range in Bacteria | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network Density | 0.01-0.05 | 0.008-0.04 | 0.015-0.06 | 0.02-0.08 | Measures sparseness of connections; lower density may indicate higher specialization |

| Average Path Length | 3.2-4.5 | 3.5-5.2 | 2.8-4.1 | 2.1-3.3 | Shorter paths may enable faster response to environmental changes |

| Clustering Coefficient | 0.15-0.35 | 0.12-0.28 | 0.18-0.41 | 0.22-0.52 | Higher values indicate more modular organization with functional subgroups |

| Number of Hub Genes | 3-8% of total nodes | 2-5% of total nodes | 4-9% of total nodes | 5-12% of total nodes | Highly connected genes that often serve essential functions |

| Motif Frequency (Feed-forward loops) | 2.8-4.1× random expectation | 2.3-3.6× random expectation | 2.5-3.9× random expectation | 3.1-4.8× random expectation | May provide noise resistance and response acceleration |

Cross-Kingdom Conservation of GRN Principles

Despite profound differences in morphology and life history, fundamental GRN properties display remarkable conservation across kingdoms. The prevalence of scale-free topology, modular organization, and specific network motifs suggests universal constraints on the evolution of biological regulation [5]. For example, feed-forward loops appear enriched in diverse lineages from bacteria to animals, potentially because they provide optimal designs for noise filtering and response acceleration [5].

Nevertheless, kingdom-specific adaptations in GRN architecture exist. Plants exhibit expanded families of transcription factors not found in other lineages, while fungi display distinctive patterns of metabolic gene regulation. Bacteria often employ operon structures that enable coordinated expression of functionally related genes—a organizational strategy largely absent in eukaryotes [18]. Understanding both the universal principles and lineage-specific adaptations of GRN organization provides crucial insights into the evolution of biological complexity.

Methodological Framework: Experimental and Computational Approaches

GRN Inference from Genomic and Transcriptomic Data

Modern GRN reconstruction leverages diverse "omic" technologies to infer regulatory relationships. Transcriptomics, particularly RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), serves as a foundational approach for identifying co-expressed genes and constructing initial network models [6]. Differential gene expression (DGE) analyses compare normalized transcript abundance between sample groups to identify genes involved in specific biological processes [6]. For example, differential expression of the transcription factor Alx3 in the African striped mouse helped identify candidate genes involved in dorsal stripe patterning [6].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized GRN analysis by enabling the resolution of regulatory relationships at cellular resolution [19]. The inherent variability in single-cell data allows researchers to detect statistical dependencies between genes that indicate putative regulatory relationships using multivariate information measures [19]. Algorithms like PIDC (Partial Information Decomposition and Context) leverage these data to infer functional interactions and reconstruct GRNs underlying cell fate decisions [19].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for GRN Analysis Across Biological Systems

| Method | Key Steps | Applications | Considerations for Non-Animal Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq & DGE Analysis | 1. RNA extraction & quality control2. Library preparation & sequencing3. Read alignment & quantification4. Normalization & differential expression testing5. Network inference using co-expression | Transcriptome-wide identification of co-regulated genes; initial GRN model construction | For plants: address high polysaccharide content; for fungi: consider unique RNA processing; for bacteria: address lack of polyadenylation |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq | 1. Single-cell suspension preparation2. Cell partitioning & barcoding3. Library preparation & sequencing4. Unique molecular identifier counting5. Network inference using tools like PIDC | Resolving cellular heterogeneity; reconstructing differentiation trajectories; cell type-specific GRNs | For plants: address cell wall removal; for microbes: consider small cell size; optimize dissociation protocols to minimize stress responses |

| Mutant Analysis & Functional Validation | 1. Generation of mutant lines (CRISPR/Cas9)2. Phenotypic characterization3. Transcriptomic analysis of mutants4. Identification of dysregulated genes5. Validation of regulatory interactions | Establishing causal relationships; testing predicted regulatory interactions; functional dissection of network motifs | For non-model systems: optimize transformation efficiency; develop species-specific CRISPR protocols; consider pleiotropic effects |

| Chromatin Accessibility Mapping | 1. Tagmentation or digestion of chromatin2. Sequencing library preparation3. Identification of open chromatin regions4. Motif enrichment analysis5. Integration with transcriptomic data | Mapping regulatory elements; linking transcription factors to target genes; identifying cis-regulatory changes | Consider kingdom-specific chromatin organization: plants have unique chromatin modifications; fungi have different nucleosome positioning; bacteria lack nucleosomes |

Functional Validation of GRN Models

Computational inference of GRNs generates hypotheses that require experimental validation. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing has become the method of choice for functional genetic tests across diverse organisms [6] [8]. The amphioxus study provides an exemplary model of GRN validation, where researchers generated mutants for both Gdf1/3 and Gdf1/3-like genes to demonstrate their divergent functions despite common ancestry [8]. This approach revealed that Gdf1/3 had lost its ancestral role in body axis formation, while Gdf1/3-like had acquired this function through regulatory rewiring [8].

Transgenic approaches further enable testing hypotheses about regulatory evolution. In amphioxus, researchers demonstrated that the intergenic region between Gdf1/3-like and Lefty could drive reporter gene expression matching both genes' patterns, suggesting that Gdf1/3-like hijacked Lefty's enhancers [8]. Such functional experiments are essential for moving beyond correlation-based network models to establish causal regulatory relationships.

Cross-Kingdom Analysis: GRN Applications Beyond Animal Systems

Bacterial GRNs: Prokaryotic Regulatory Strategies

Prokaryotes employ distinctive GRN architectures optimized for rapid environmental response. The operon structure, where multiple genes are transcribed as a single unit under control of a shared promoter, represents a fundamental bacterial regulatory strategy [18]. The lac operon in Escherichia coli exemplifies this organization, with a repressor protein controlling coordinated expression of lactose metabolism genes in response to environmental nutrients [18].

Bacterial GRNs typically exhibit shorter average path lengths and higher connectivity compared to eukaryotic networks, reflecting adaptations for rapid transcriptional reprogramming [18]. These networks are predominantly regulated at the transcriptional level, since the absence of a nuclear envelope enables coupled transcription and translation [18]. This architectural simplicity makes bacterial GRNs powerful models for understanding fundamental principles of network dynamics and evolution.

Plant GRNs: Unique Adaptations in Multicellular Photosynthesizers

Plants have evolved distinctive GRN architectures reflecting their sessile lifestyle, photosynthetic metabolism, and unique developmental constraints. The plant-specific transcription factor families (e.g., MADS-box, WRKY, NAC) regulate processes with no animal equivalents, such as photomorphogenesis, secondary metabolism, and cell wall biosynthesis. Plant GRNs also coordinate responses to environmental signals through sophisticated hormonal integration, enabling plastic development without behavioral avoidance mechanisms.

Unlike animals, where germline segregation occurs early in development, plants maintain meristematic tissues that generate gametes throughout their life cycle, creating unique constraints on evolutionary processes. This developmental strategy may influence GRN evolution, potentially explaining differences in network modularity and hub gene distribution between plants and animals.

Fungal GRNs: Regulatory Networks in Multicellular Microbes

Fungi represent a third multicellular kingdom with distinctive GRN organizations reflecting their absorptive heterotrophy and filamentous growth. Fungal networks exhibit particularly high clustering coefficients, suggesting strong modular organization aligned with metabolic specialization. The evolution of complex multicellularity in fungi occurred independently from plants and animals, providing an invaluable comparative system for understanding alternative solutions to coordinating cellular differentiation.

GRNs controlling fungal development, such as mushroom formation in basidiomycetes or conidiation in aspergilli, offer compelling models for studying the evolution of complex morphology. The relatively compact genomes of fungi, combined with sophisticated genetic tools, make them ideal systems for experimental GRN analysis, particularly for elucidating principles that may be obscured by genomic complexity in animal models.

Visualization: Cross-Kingdom GRN Principles

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental components and regulatory logic of Gene Regulatory Networks, highlighting elements conserved across biological kingdoms.

Cross-Kingdom GRN Architecture

The following diagram illustrates a representative experimental workflow for reconstructing and validating Gene Regulatory Networks across diverse biological systems.

GRN Reconstruction Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for GRN Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cross-Kingdom GRN Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in GRN Research | Kingdom-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Kits | Single-cell RNA-seq kits (10x Genomics), ATAC-seq kits, ChIP-seq kits | Generate transcriptomic and epigenomic data for network inference | Plant protocols require specialized nuclei isolation; bacterial kits address lack of polyA tails |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, guide RNA libraries, homology-directed repair templates | Functional validation of predicted regulatory interactions | Species-specific codon optimization; delivery method optimization (particle bombardment for plants) |

| Antibodies | Transcription factor-specific antibodies, histone modification antibodies | Chromatin immunoprecipitation; protein localization and quantification | Limited commercial availability for non-model systems; requires validation for cross-reactivity |

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP), luciferase reporters, in situ hybridization probes | Visualize spatial and temporal expression patterns; test regulatory element activity | Temperature optimization for different growth conditions; substrate availability in different tissues |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Network inference algorithms (PIDC), motif discovery tools (MEME), visualization software (Cytoscape) | Computational reconstruction, analysis, and visualization of GRNs | Algorithm parameter adjustment for kingdom-specific genomic features; custom genome annotations |

Implications for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Research

The application of GRN analysis beyond animal models has profound implications for drug discovery and therapeutic development. Understanding conserved network principles enables identification of essential cellular processes that can be targeted for antimicrobial development. For example, mapping the GRNs controlling fungal virulence or bacterial antibiotic resistance provides new avenues for combating infectious diseases [20].

Comparative GRN analysis also reveals why certain cellular processes are difficult to target therapeutically—highly connected hub genes in essential networks often exhibit pleiotropic effects when disrupted. Network-based drug discovery approaches can identify peripheral nodes or synthetic lethal interactions that provide greater specificity. Additionally, understanding how pathogenic networks evolve in response to therapeutic pressure informs strategies for preventing treatment resistance.

The pharmaceutical industry increasingly utilizes GRN-based approaches for target identification, mechanism of action studies, and toxicology assessment. As single-cell technologies become more accessible, patient-specific network analyses may enable personalized medicine approaches that account for individual variation in regulatory architecture.

Gene Regulatory Networks represent a universal biological paradigm that transcends traditional taxonomic boundaries. The conserved principles of scale-free topology, modular organization, and specific network motifs reveal fundamental constraints on the evolution of biological regulation. Simultaneously, lineage-specific adaptations in GRN architecture reflect diverse ecological strategies and developmental constraints.

Future research directions should include: (1) expanded comparative GRN mapping across underrepresented lineages, particularly non-seed plants, anaerobic fungi, and archaea; (2) integration of single-cell multi-omic approaches to resolve regulatory networks at cellular resolution across diverse species; (3) development of kingdom-specific computational tools that account for distinctive genomic features; and (4) application of synthetic biology to test evolutionary hypotheses by engineering minimal networks in different cellular contexts.

As GRN research continues to move beyond zoocentrism, it will provide increasingly powerful insights into both the universal principles and diverse implementations of biological regulation, with profound implications for basic evolutionary theory and applied biomedical science.

The synthesis of evolutionary biology and developmental biology, once separated by the distinct paradigms of ultimate and proximate causation, has matured into an integrated discipline powered by gene regulatory network (GRN) analysis. This technical guide details how modern evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo) leverages single-cell technologies, computational models, and molecular profiling to connect genetic variation that arises in populations to the developmental mechanisms that generate phenotypic diversity. By framing GRN architecture as the central interface between population-level processes and cellular outcomes, we provide researchers with methodologies to dissect how evolutionary forces shape developmental trajectories and how developmental constraints bias evolutionary paths. This integration enables predictive modeling of phenotypic variation and informs therapeutic strategies that target evolutionary-conserved developmental pathways.

The historical divide between ultimate causation (evolutionary why) and proximate causation (developmental how) has narrowed through the conceptual framework of evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo). This field explicitly connects genetic variation that arises during embryonic development to the emergence of diverse adult forms, establishing developmental mechanisms as agents of evolutionary change [21]. The gene regulatory network (GRN)—comprising interacting transcription factors, signaling pathways, and regulatory DNA—serves as the fundamental computational unit translating genotype to phenotype. Modules within these networks control specific aspects of cell phenotype, establishing the molecular basis for cellular identity and function [21].

Population genetics provides the theoretical foundation for understanding how mutation, selection, drift, and gene flow alter allele frequencies in populations over generations [22] [23]. Meanwhile, developmental biology elucidates the mechanistic pathways through which genetic information executes complex morphogenetic programs. The integration of these domains occurs through analysis of GRN architecture, where population-level processes introduce variation that developmental mechanisms either amplify or constrain. This synthesis enables researchers to trace evolutionary paths from standing genetic variation through developmental execution to adaptive phenotypes.

Theoretical Foundations: Evolutionary Mechanisms and Developmental Constraints

Population Genetic Processes

Evolutionary change requires genetic variation upon which evolutionary forces act. Four primary mechanisms alter trait frequencies in populations:

- Natural Selection: Differential reproduction of individuals based on heritable traits that enhance environmental adaptation [23]. Selection operates on phenotypic variation, with fitness advantages increasing allele frequencies across generations.

- Mutation: The ultimate source of all genetic variation through changes in DNA sequence [23]. Mutations introduce new alleles into populations, though most are selectively neutral or deleterious, with rare beneficial mutations spreading through selection.

- Genetic Drift: Random fluctuations in allele frequencies due to sampling error in finite populations [23]. Drift is potent in small populations and following bottleneck events (sudden population reductions) or founder effects (new populations established by few individuals).

- Gene Flow: Transfer of genetic variation between populations through migration of individuals or gametes [23]. Gene flow can introduce novel alleles or alter frequency distributions, potentially counteracting local adaptation.

Table 1: Fundamental Evolutionary Mechanisms and Their Effects on Genetic Variation

| Mechanism | Effect on Variation | Population Scale Dependency | Role in Evolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Selection | Reduces variation through selective removal; maintains through balancing selection | Effective across all population sizes | Adaptive change; increases fitness |

| Mutation | Increases variation by introducing new alleles | Effect independent of population size | Ultimate source of all genetic novelty |

| Genetic Drift | Reduces variation through random loss of alleles | Stronger in smaller populations | Non-adaptive change; fixation/loss of alleles |

| Gene Flow | Increases variation through migration; can homogenize populations | Effective across distances depending on dispersal | Counteracts divergence; introduces novel variants |

Developmental Program Execution

Development transforms genetic information into multicellular organisms through spatially and temporally coordinated gene expression. Key concepts include:

- Heterochrony: Evolutionary changes in the timing of developmental events, which can alter developmental trajectories and adult morphologies [21]. At the cellular level, heterochrony manifests as altered cell cycle progression or differentiation timing.

- Homeosis: Transformation of one embryonic structure into another, often through mutation in regulatory genes controlling cell identity [21]. This represents the redeployment of existing developmental modules to novel contexts.

- Modularity: Organization of developmental processes into discrete, semi-autonomous units (gene modules) that can be independently modified, co-opted, or duplicated during evolution [21].

- Plasticity: Environmentally contingent development, where a single genotype produces different phenotypes in response to environmental conditions [21].

Technological Framework: Single-Cell Resolution for Evo-Devo Synthesis

Revolutionary technologies now enable direct observation of evolutionary processes operating through developmental mechanisms at unprecedented resolution.

Single-Cell Omics Platforms

Table 2: Single-Cell Technologies for Evolutionary Developmental Analysis

| Technology | Analytical Focus | Application in Evo-Devo | Resolution Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-Seq | Transcriptome profiling | Cell type identification; developmental trajectory mapping | Discriminates cell types based on unique gene expression combinations [21] |

| scATAC-Seq | Chromatin accessibility | Regulatory element activity; transcription factor binding potential | Identifies heterogeneity in regulatory responses [21] |

| scChIP-Seq | Protein-DNA interactions | Epigenetic state mapping; transcription factor binding | Reveals sequence of events in cell state transitions [21] |

| scRibo-Seq | Translated mRNAs | Translation efficiency; protein synthesis rates | Identifies temporal variation in protein abundance [21] |

Perturbation and Lineage Tracing Tools

- CRISPR-Based Genome Editing: Enables precise manipulation of regulatory elements and coding sequences to test GRN architecture hypotheses [21]. Coupled with single-cell readouts, this establishes causal relationships between genetic variation and developmental outcomes.

- Cell Cycle Reporters: Genetically encoded fluorescent proteins that indicate transit time through cell cycle phases [21]. These enable quantification of heterochronic effects at cellular resolution.

- Lineage Tracing Systems: Cre-lox and related systems that permanently mark progenitor cells and their descendants, enabling reconstruction of cell fate decisions across development.

Experimental Protocols: Integrating Evolutionary and Developmental Analysis

Protocol 1: Single-Cell Analysis of Evolutionary Divergence

Objective: Identify conserved and divergent developmental trajectories between related species.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect embryonic tissues at matched developmental stages from multiple species (e.g., different mammalian models).

- Single-Cell Dissociation: Prepare single-cell suspensions using enzymatic digestion with mechanical disruption.

- Multiplexed scRNA-Seq: Process cells through 10X Genomics Chromium platform with cell hashing for sample multiplexing.

- Cross-Species Integration: Align sequencing data using orthologous gene mapping and integrate datasets with Seurat or SCANPY.

- Trajectory Inference: Construct developmental trajectories using PAGA, Monocle3, or Slingshot algorithms.

- GRN Reconstruction: Infer regulatory networks using SCENIC or PIDC from time-course data.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Dissociation Enzymes: Collagenase IV (2mg/mL) + Dispase II (1U/mL) in PBS for 30 minutes at 37°C

- Cell Hashing Antibodies: TotalSeq-C antibodies for sample multiplexing (1:200 dilution)

- Single-Cell Library Prep: 10X Genomics Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3' Reagent Kit v3.1

Protocol 2: Population-Genetic Developmental Screening

Objective: Quantify how natural genetic variation affects developmental GRN performance.

Methodology:

- Founder Population Selection: Establish diverse genetic backgrounds (e.g., Collaborative Cross mice, natural isolates).

- Embryo Collection: Time mating and collect embryos at critical developmental windows.

- Phenotypic Profiling: Image entire embryos with light-sheet microscopy for morphological quantification.

- Single-Cell Index Sorting: Flow-sort specific cell populations with simultaneous index recording.

- scATAC-Seq + scRNA-Seq: Process aliquots for multi-omics profiling.

- QTL Mapping: Integrate phenotypic and molecular data with genome sequences to identify loci affecting developmental variation.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Fixation Buffer: 4% PFA + 0.1% Glutaraldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes (on ice)

- Nuclei Isolation Buffer: 10mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl₂, 0.1% Tween-20, 1% BSA, 1U/μL RNase inhibitor

- Transposition Mix: Illumina Tagmentase TDE1 in TD Buffer (1:10 dilution)

Visualization Framework: GRN Architecture and Evolutionary Modification

The following diagrams model key relationships in evolutionary developmental biology, created using DOT language with specified color palette and contrast requirements.

GRN Integration of Causation

Cellular Heterochrony Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Evo-Devo Synthesis

Table 3: Critical Research Reagents for Evolutionary Developmental Biology

| Reagent/Category | Specific Product Examples | Function in Evo-Devo Research |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Profiling | 10X Genomics Chromium System, Parse Biosciences Split-Pool Kit | Discrimination of cell types based on unique gene expression signatures; comparison of cellular identities across species [21] |

| Cell Cycle Tracking | FUCCI (Fluorescent Ubiquitination-based Cell Cycle Indicator) systems, mVenus-hGem(1/110) | Visualization of how long each cell type spends resting or proliferating; identification of heterochronic variation [21] |

| Genome Editing | CRISPR-Cas9 systems (Streptococcus pyogenes), Base editors, Prime editors | Precise manipulation of regulatory elements to test evolutionary hypotheses about GRN function [21] |

| Lineage Tracing | Cre-lox systems (Confetti, Brainbow), ScarTrace | Reconstruction of cell fate decisions and phylogenetic relationships between cell populations |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10X Visium, MERFISH, Seq-Scope | Mapping gene expression patterns within tissue architecture to understand evolutionary morphology |

| Cross-Species Hybridization | Species-specific antibodies, Orthologous FISH probes | Direct comparison of protein localization and expression patterns across evolutionary distance |

Data Integration and Computational Modeling

The power of the Evo-Devo synthesis emerges from computational frameworks that integrate population genetic parameters with developmental GRN models. Key approaches include:

- Population Genetic Parameters in Developmental Context: Effective population size (Nₑ) calculations inform the expected burden of deleterious mutations in developmental genes. Selection coefficients (s) quantify the fitness consequences of GRN variants.

- PhyloGene Regulatory Analysis: Comparative genomics across multiple species identifies conserved non-coding elements likely serving developmental regulatory functions.