From Genes to Causality: Leveraging Genotypic Data for Causal Inference in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing causal relationships from observational data using genetic tools.

From Genes to Causality: Leveraging Genotypic Data for Causal Inference in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing causal relationships from observational data using genetic tools. It covers the foundational principles of causal inference, explores core methodologies like Mendelian Randomization, addresses key methodological challenges and optimization strategies, and reviews frameworks for validating and comparing causal findings. By synthesizing current methods, computational resources, and applications, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to robustly inform target validation and trial design, thereby enhancing the efficiency and success of therapeutic development.

The Genetic Basis for Causal Inference: Principles, Data, and Discovery

Establishing causality, rather than merely observing correlation, is a fundamental challenge in biomedicine. In genotypic research and drug discovery, the ultimate goal is to identify causal relationships between genetic targets, biological pathways, and disease outcomes [1] [2]. Causal inference provides a structured framework for this pursuit, leveraging human knowledge, data, and machine intelligence to reduce cognitive bias and improve decision-making [1]. The emerging approach of causal artificial intelligence (AI) is now transforming the pharmaceutical business model by improving predictions of clinical efficacy and connecting drug targets directly to disease biology [2]. This article explores the core frameworks and methodologies—particularly counterfactual analysis and causal diagrams—that enable researchers to distinguish causation from correlation in complex biological systems.

Theoretical Foundations of Causal Inference

The Counterfactual Framework

The counterfactual framework, rooted in Rubin's potential outcomes model, provides a formal structure for evaluating causal relationships [3] [4]. According to this framework, a cause (X) of an effect (Y) meets the condition that if "X had not occurred, Y would not have occurred" (at least not when and how it did) [3]. This approach enables researchers to pose critical counterfactual questions in genotypic studies: What would be the gene expression if an individual had not been exposed to a disease? What would be the phenotypic outcome if a specific genetic variant were not present? [4].

In practical terms, for a gene expression study, we define two potential outcomes for each individual (i) and gene (g):

- ( \lambda_{gi}^{(0)} ): The pseudo-bulk expression of gene g if individual i had not been exposed to a disease

- ( \lambda_{gi}^{(1)} ): The pseudo-bulk expression of gene g if individual i had been exposed to a disease [4]

In observational studies, we only observe one of these outcomes for each individual, while the other remains unobserved (the "counterfactual"). The core challenge of causal inference is to impute these missing potential outcomes to estimate the true causal effect [4].

Causal Diagrams and Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs)

Causal diagrams, particularly Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs), provide a powerful visual tool for representing assumed causal relationships between variables [5]. These graphs encode assumptions about the causal structure underlying biological phenomena and help identify potential biases in observational studies [5]. In DAGs, variables are represented as nodes, and causal relationships are represented as directed arrows (→). Critically, these graphs must not contain any directed cycles, preserving temporal precedence where causes must precede effects [5].

Table 1: Key Components of Causal Diagrams

| Component | Description | Role in Causal Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Nodes | Variables in the system (e.g., genotype, disease) | Represent the key elements in the causal system |

| Arrows | Directed edges showing causal influence | Indicate assumed causal relationships between variables |

| Paths | Sequences of connected arrows | Can represent causal or non-causal pathways |

| Confounders | Common causes of exposure and outcome | Create spurious associations that must be controlled |

| Colliders | Common effects of exposure and outcome | Conditioning on them can introduce bias |

| Mediators | Variables on causal pathway between exposure and outcome | Explain the mechanism of causal effect |

The structure of DAGs follows specific terminology: a cause is a variable that influences another variable (ancestor), with direct causes called parents. An effect is a variable influenced by another variable (descendant), with direct effects called children [5]. For example, in a DAG connecting genetic variant (A), biomarker (B), and disease (D), A is a parent of B, and B is a child of A and parent of D.

Causal Inference Methodologies and Protocols

Experimental Protocol for Causal Inference in Single-Cell Genomic Studies

Protocol Title: Causal Differential Expression Analysis in Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data

Purpose: To identify disease-associated causal genes while adjusting for confounding factors without prior knowledge of control variables [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing data from case-control studies

- Computational resources for processing large-scale genomic data

- Quality control metrics for cell and gene filtering

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Generate pseudo-bulk expression profiles by aggregating single-cell expression counts for each individual and cell type [4].

- Model Assumptions: Establish causal assumptions including stable unit treatment value (no interference between individuals) and conditional ignorability (conditional independence of potential outcomes and treatment assignment) [4].

- Counterfactual Imputation: Implement matching algorithms to impute missing counterfactual expressions for each individual [4].

- Effect Estimation: Compare observed and imputed potential outcomes to estimate average treatment effects on gene expression.

- Significance Testing: Apply statistical tests to identify significantly differentially expressed causal genes while controlling false discovery rates.

Validation: Benchmark against traditional differential expression methods and validate findings through experimental perturbation where feasible [4].

Protocol for Causal Diagram Construction and Analysis

Protocol Title: Building Causal Diagrams for Complex Disease Genetics

Purpose: To formally represent and analyze causal assumptions in genetic epidemiology studies [5] [3].

Procedure:

- Variable Identification: Identify all relevant variables including exposures, outcomes, and potential confounders—even if unmeasured [5].

- Relationship Specification: Draw directed arrows from causes to effects based on established biological knowledge and temporal ordering.

- Pathway Classification: Identify all paths between exposure and outcome, classifying them as causal or non-causal.

- Bias Assessment: Apply d-separation rules to identify potential sources of confounding, selection bias, or collider bias [5].

- Adjustment Set Identification: Determine the minimal set of variables that need to be adjusted for in statistical analysis to block all non-causal paths while preserving causal paths.

Application Example: In studying smoking and progression to ESRD, construct DAG including smoking, renal function, inflammation markers, and other potential common causes to identify appropriate adjustment sets [5].

Visualization of Causal Structures

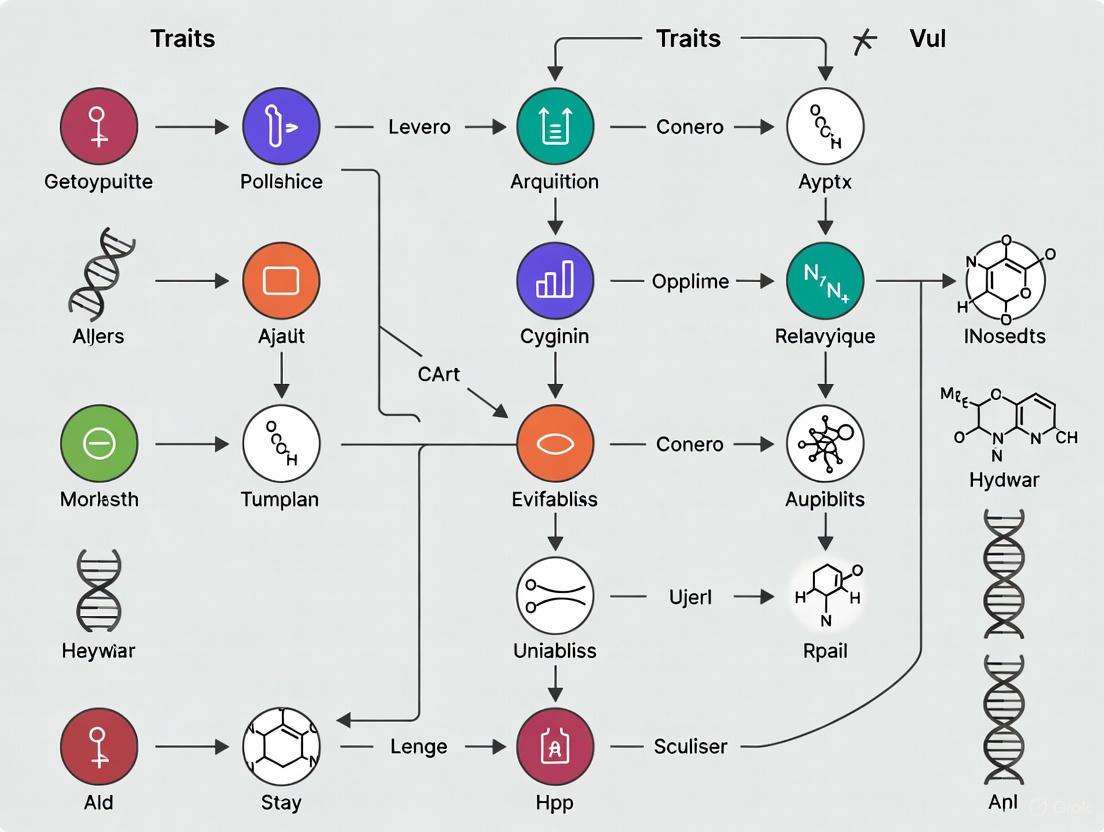

Causal Diagrams for Genetic Studies

Title: Causal diagram for genetic association study

Counterfactual Framework in Practice

Title: Counterfactual framework for causal inference

Research Reagent Solutions for Causal Inference

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Causal Inference

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Causal AI Platforms (e.g., biotx.ai) | Scalable causal inference for target identification | Drug target validation using GWAS data [2] |

| Directed Acyclic Graphs | Visual representation of causal assumptions | Identifying confounding variables and bias sources [5] |

| Potential Outcomes Framework | Formal structure for counterfactual reasoning | Estimating causal effects in observational studies [3] [4] |

| Sufficient Component Cause Model | "Causal pie" diagrams for component causes | Understanding genetic heterogeneity and interaction [3] |

| Structural Equation Modeling | Statistical estimation of causal pathways | Knowledge graph construction for relational transfer learning [6] |

| Counterfactual Imputation Methods | Estimation of unobserved potential outcomes | Single-cell differential expression analysis [4] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Genomic Medicine

The integration of causal inference methodologies is revolutionizing drug discovery. Causal AI platforms are now being used to analyze massive genomic datasets, with one platform curating 9,539 datasets including 22,376,782 cases across 3,303 diseases to identify causal drug targets [2]. This approach has demonstrated practical utility, with genetic support from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) significantly improving phase 2 success rates—two-thirds of FDA-approved drugs in 2021 had such genetic support [2].

In genomic medicine, causal inference methods like CoCoA-diff have been successfully applied to single-cell RNA sequencing data from 70,000 brain cells to identify 215 differentially regulated causal genes in Alzheimer's disease [4]. This approach substantially improves statistical power by properly adjusting for confounders without requiring prior knowledge of control variables, enabling more accurate identification of disease-relevant genes across diverse cell types.

The sufficient component cause model has proven particularly valuable for understanding complex genetic architecture [3]. This model illustrates how multiple genetic and environmental factors can act as component causes that together form sufficient causes for disease, providing a framework for understanding penetrance, phenocopies, genetic heterogeneity, and gene-environment interactions [3].

Causal inference represents a paradigm shift in genotypic research and drug development, moving beyond correlational associations to establish true causal relationships. The counterfactual framework and causal diagrams provide researchers with powerful tools to articulate explicit causal assumptions, identify potential biases, and design appropriate analytical strategies. As these methodologies continue to evolve and integrate with machine learning approaches, they promise to enhance our ability to identify valid therapeutic targets and understand the complex causal architecture of human disease. The protocols and frameworks outlined here provide a foundation for implementing these approaches in ongoing genotypic research.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) represent a foundational approach in genetic epidemiology, serving as a primary discovery engine for identifying statistically significant associations between single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and complex traits or diseases. By systematically scanning genomes of diverse individuals, GWAS has revolutionized our understanding of the genetic architecture of complex diseases, successfully identifying hundreds of thousands of genetic variants associated with thousands of phenotypes [7]. The fundamental principle underlying GWAS is the statistical inference of linkage disequilibrium (LD)—the non-random association of alleles at different loci—primarily caused by genetic linkage but also influenced by mutation, selection, and non-random mating [8]. This methodology leverages historical recombinations accumulated over many generations, resulting in significantly higher mapping resolution compared to traditional family-based linkage studies [8].

The transition from GWAS to causal inference represents a paradigm shift in genetic epidemiology. While association identifies statistical dependencies between genetic variants and traits, causal inference seeks to determine whether genetic variants actively influence disease risk [9]. This distinction is crucial; observed associations may not necessarily indicate causal relationships, and conversely, the absence of association does not preclude causation [9]. As the field advances, integrating GWAS findings with causal inference frameworks has become essential for elucidating the biological mechanisms underlying complex diseases and for identifying genuine therapeutic targets.

Key Methodological Approaches and Statistical Models

Evolution of GWAS Statistical Models

The statistical foundation of GWAS has evolved substantially to address computational and methodological challenges. Early GWAS primarily utilized general linear models (GLM) that incorporated principal components or population structure matrices as covariates to reduce spurious associations [8]. These were implemented in pioneering software packages like PLINK, TASSEL, and GenABEL [8]. However, GLM approaches failed to account for unequal relatedness among individuals within subpopulations, leading to increased false positive rates.

The introduction of mixed linear models (MLM) marked a significant advancement by incorporating kinship matrices derived from genetic markers to model the covariance structure among individuals [8]. This approach substantially improved control for population stratification and familial relatedness. Computational innovations such as EMMA, EMMAx, FaST-LMM, and GEMMA enhanced the feasibility of MLM for large datasets [8]. Further refinements led to the development of compressed MLM (CMLM), enriched CMLM (ECMLM), and SUPER models, which improved statistical power by addressing confounding between testing markers and random individual genetic effects [8].

More recently, multi-locus models have emerged to further enhance power and accuracy. The multiple loci mixed model (MLMM) incorporates associated markers as covariates, while the Fixed and Random Model Circulating Probability Unification (FarmCPU) separately places random individual genetic effects and testing markers in different models [8]. The most advanced approach, Bayesian-information and Linkage-disequilibrium Iteratively Nested Keyway (BLINK), completely removes random genetic effects and uses two GLMs iteratively—one to select associated markers as covariates and another to test markers individually [8]. This innovation retains GLM's computational efficiency while achieving higher statistical power than previous multi-locus models.

Table 1: Evolution of GWAS Statistical Models and Their Characteristics

| Model Category | Representative Models | Key Characteristics | Software Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Linear Models | GLM | Adjusts for population structure using principal components; computationally efficient but prone to spurious associations from unequal relatedness | PLINK, TASSEL, GenABEL |

| Mixed Linear Models | MLM, EMMA, EMMAx, FaST-LMM | Incorporates kinship matrices to account for unequal relatedness; reduces false positives but computationally intensive | EMMA, EMMAx, FaST-LMM, GEMMA, GAPIT |

| Enhanced Mixed Models | CMLM, ECMLM, SUPER | Improves statistical power by addressing confounding between testing markers and random genetic effects | GAPIT, TASSEL |

| Multi-locus Models | MLMM, FarmCPU, BLINK | Incorporates associated markers as covariates or uses iterative model selection; enhances power while maintaining computational efficiency | GAPIT, rMVP, BLINK |

Analytical Pipelines and Workflow

A standard GWAS pipeline encompasses multiple critical stages, from initial quality control to final association testing. The first phase involves rigorous quality control (QC) procedures to ensure data integrity, including checks for per-sample quality, relatedness, replicate discordance, SNP quality control, sex inconsistencies, and chromosomal anomalies [7] [10]. Following QC, population stratification must be addressed using methods such as principal component analysis (PCA) to correct for systematic genetic differences between population subgroups that could generate spurious associations [10] [11].

The core association analysis employs the statistical models detailed in Section 2.1, with model selection dependent on study design, sample structure, and computational resources. Post-association analysis involves multiple testing correction, typically using Bonferroni correction or false discovery rate (FDR) controls, though the Bonferroni method is often over-conservative for GWAS due to LD between markers [8]. For biobank-scale datasets, secure federated GWAS (SF-GWAS) approaches have recently emerged, enabling collaborative analysis across institutions while maintaining data privacy through cryptographic methods like homomorphic encryption and secure multiparty computation [11].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive GWAS Workflow. The analysis pipeline progresses from data preparation through core association testing to downstream causal inference applications.

Post-GWAS Analysis and Causal Inference Methods

Functional Weighting and Annotation

Post-GWAS analysis has emerged as a crucial step for extracting biological meaning from association results and prioritizing variants for functional validation. A comprehensive evaluation of 17 functional weighting methods demonstrated that approaches incorporating expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data and pleiotropy information can nominate novel associations with high positive predictive value (>75%) across multiple traits [12]. However, the study revealed a fundamental trade-off between sensitivity and positive predictive value, with no method achieving both high sensitivity and high PPV simultaneously [12].

Methods such as MTAG leverage genetic correlations across traits to improve power, while Sherlock integrates eQTL and GWAS data to identify genes whose expression levels are associated with trait-related genetic variation [12]. LSMM (Latent Spatial Model Management) demonstrated high sensitivity but lower PPV, highlighting the methodological trade-offs in functional prioritization [12]. The performance of these methods varies substantially across traits, with methods utilizing brain eQTL annotations (e.g., EUGENE and SMR) showing particular utility for neuropsychiatric disorders [12].

Mendelian Randomization and Causal Inference

Mendelian randomization (MR) has become a cornerstone method for causal inference in genetic epidemiology, using genetic variants as instrumental variables to estimate causal effects between modifiable exposures and disease outcomes [13] [14]. The TwoSampleMR package exemplifies the integration of data management, statistical analysis, and access to GWAS summary statistics repositories, streamlining the MR workflow [14]. The typical MR pipeline involves: (1) selecting genetic instruments associated with the exposure; (2) extracting their effects on the outcome; (3) harmonizing effect sizes to ensure consistent allele coding; and (4) performing MR analysis with sensitivity analyses to assess assumption violations [14].

Beyond MR, more comprehensive causal inference frameworks are emerging. Algorithmic information theory offers a novel approach to causal discovery that doesn't rely on traditional probability theory, potentially enabling causal inference from single observations rather than requiring large samples [9]. These methods leverage the Causal Markov Condition, which connects causal structures to conditional independence relationships, allowing researchers to infer causal networks from observational genetic data [9].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Post-GWAS and Causal Inference Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| TwoSampleMR | Mendelian Randomization | Data harmonization, extensive sensitivity analyses, integration with IEU OpenGWAS database | Estimating causal effects between exposures and outcomes using GWAS summary statistics |

| GPA | Functional Prioritization | Integrates GWAS with functional genomics data; improves risk locus identification | Identifying truly associated variants while controlling for false discoveries |

| MTAG | Multi-trait Analysis | Increases power by leveraging genetic correlations across traits | Analyzing multiple related phenotypes simultaneously |

| COLOC | Colocalization Analysis | Determines if two traits share causal genetic variants | Identifying shared genetic mechanisms between traits |

| SMR | Summary-data-based MR | Integrates GWAS and eQTL data to identify trait-associated genes | Inferring causal relationships between gene expression and complex traits |

Practical Protocols and Applications

Protocol for Comprehensive GWAS Analysis

A standardized protocol for GWAS utilizes a minimal set of software tools to perform diverse analyses including file format conversion, missing genotype imputation, association testing, and result interpretation [8]. This protocol employs BEAGLE for genotype imputation, BLINK or FarmCPU for high-power association testing, and GAPIT for data management, analysis, and visualization [8]. The implementation of this protocol using data from the Rice 3000 Genomes Project demonstrates its utility for both plant and human genetic studies [8].

For researchers implementing GWAS, several critical decisions must be addressed. First, experiment-wise significance thresholds must be carefully determined, as overly conservative approaches (e.g., strict Bonferroni correction) can hide true associations, while overly liberal thresholds generate excessive false positives [8]. The number of independent tests, rather than the total number of markers, should guide threshold determination, accounting for LD between variants [8]. Second, population structure must be adequately controlled using PCA or mixed models to prevent spurious associations [8]. Third, quality control should address potential false positives from phenotypic outliers, rare alleles in small samples, and genotyping errors [8].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GWAS

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| GWAS Software Packages | GAPIT, PLINK, TASSEL, GEMMA, BLINK | Implement various statistical models for association testing; provide data management and visualization capabilities |

| Summary Statistics Databases | GWAS Catalog, IEU OpenGWAS, GWAS Atlas, PhenoScanner | Store and provide access to harmonized GWAS summary statistics for thousands of traits |

| Genotype Imputation | BEAGLE, Minimac4 | Estimate missing genotypes using reference haplotypes; increases marker density and analytical power |

| Causal Inference Tools | TwoSampleMR, COLOC, SMR, LD Score Regression | Perform Mendelian randomization, colocalization, and genetic correlation analyses |

| Functional Annotation | ANNOVAR, FUMA, HaploReg, RegulomeDB | Annotate significant variants with functional genomic information (e.g., regulatory elements, chromatin states) |

| Population Reference Panels | 1000 Genomes Project, HapMap, UK Biobank | Provide representative genetic variation data for imputation and population structure assessment |

Diagram 2: From GWAS to Causal Inference. Integration of GWAS summary statistics with various analytical methods and data resources enables robust causal inference.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The application of GWAS has expanded beyond traditional single-trait analysis to sophisticated multi-trait approaches and biobank-scale integrations. Multi-trait analysis methods leverage genetic correlations across phenotypes to enhance discovery power, particularly for traits with limited sample sizes [12]. Polygenic risk scores (PRS) aggregate the effects of numerous genetic variants to predict individual disease susceptibility, with applications in risk stratification and preventive medicine [13]. However, PRS performance varies considerably across ancestral groups, highlighting the critical need for diverse representation in genetic studies [13].

Secure and federated approaches represent the future of collaborative GWAS. SF-GWAS enables institutions to jointly analyze genetic data while preserving confidentiality through cryptographic privacy guarantees [11]. This approach supports standard PCA and linear mixed model pipelines on biobank-scale datasets (e.g., UK Biobank with 410,000 individuals) with practical runtimes, representing an order-of-magnitude improvement over previous methods [11]. SF-GWAS produces results virtually identical to pooled analysis while avoiding the privacy concerns of data sharing, addressing a major limitation in current genetic research [11].

The integration of GWAS with functional genomics data—including transcriptomics, epigenomics, and proteomics—will further advance causal gene identification. Methods such as transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) and colocalization analysis test whether genetic associations with complex traits are mediated through molecular phenotypes like gene expression [15] [12]. These approaches help bridge the gap between statistical association and biological mechanism, ultimately fulfilling the promise of GWAS as a discovery engine for understanding and treating complex diseases.

The integration of large-scale genomic and phenotypic data has revolutionized the capacity to infer causal relationships in complex traits and diseases. For researchers and drug development professionals, public data resources provide unprecedented opportunities for hypothesis generation and validation. These resources—including genome-wide association study (GWAS) catalogs, biobanks, and phenotype databases—offer structured, standardized data that can be mined to identify potential therapeutic targets and understand disease mechanisms. Framed within the broader context of causal inference, these databases provide the foundational evidence needed to progress from statistical associations to evidence of causal relationships, ultimately helping to prioritize targets for clinical intervention [16]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of major public data resources, quantitative comparisons of their contents, detailed experimental protocols for causal analysis, and visualization of key workflows to empower researchers in leveraging these tools effectively.

Several major databases provide structured access to human genetic and phenotypic data for research purposes. The table below summarizes the core features of each resource:

Table 1: Major Public Data Resources for Genetic and Phenotypic Research

| Resource Name | Primary Focus | Data Content | Access Process | Key Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS Catalog [17] [18] [19] | Published genome-wide association studies | Variant-trait associations, summary statistics, study metadata | Open access via web interface, API, and FTP | >45,000 GWAS, >5,000 traits, >40,000 summary statistics datasets [19] |

| UK Biobank [20] | Prospective cohort study | Health record data, imaging, genomic data from 500,000 participants | Application process for researchers via secure cloud platform | 500,000 participants aged 40-69 at recruitment [20] |

| dbGaP [21] | Genotype-phenotype interactions | Study documents, phenotypic datasets, genomic data | Controlled access requiring authorization | 3,000 released studies, 5.1 million study participants [21] |

| DECIPHER [22] | Clinical genomic data | Phenotypic and genotypic data from patients with rare diseases | Free browsing; registration for data sharing | 51,700 patient cases, contributed to >4,000 publications [22] |

Data Volume and Scope Trends

The GWAS Catalog has experienced substantial growth in data volume and complexity. As of 2022, the resource contained approximately 400,000 curated SNP-trait associations from over 45,000 individual GWAS across more than 5,000 human traits [19]. The scope has expanded from standard GWAS to include sequencing-based GWAS (seqGWAS), gene-based analyses, and copy number variation (CNV) studies. Between the first quarter of 2021 and second quarter of 2022, 14% of studies and 5% of publications curated were seqGWAS [19]. The mean number of GWAS per publication has grown significantly from 3 in 2018 to 39 in 2021, reflecting the increase in large-scale analyses of multiple traits in individual publications [19].

Causal Inference Framework and Methodologies

Causal Paradigms in Genetic Epidemiology

Genetic data strengthens causal inference in observational research by providing instrumental variables that are genetically determined and therefore not subject to reverse causation [16]. The integration of genetic data enables researchers to progress beyond confounded statistical associations to evidence of causal relationships, revealing complex pathways underlying traits and diseases. Several genetically informed methods have been developed to strengthen causal inference:

- Mendelian Randomization: Uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to test causal relationships between modifiable risk factors and disease outcomes [16]

- Twin and Family Designs: Leverage genetic relatedness to control for confounding factors [16]

- Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): A regression-based approach to causal modeling that tests different hypothetical causal relationships [23]

- Bayesian Unified Framework (BUF): A flexible approach using Bayesian model comparison and averaging to identify causal partitions [23]

Causal Models for Genotype-Expression-Phenotype Relationships

The relationship between genotype (G), gene expression (GE), and phenotype (P) can be conceptualized through several causal models, each with distinct biological implications:

Figure 1: Causal models for genotype-expression-phenotype relationships. Different causal scenarios illustrate possible relationships between genetic variants, gene expression, and phenotypic outcomes. [23]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Causal Analysis Using Integrated Genotype and Expression Data

This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for inferring causal relationships between genotype, gene expression, and phenotype, based on methodologies applied to the Genetic Analysis Workshop 19 data [23].

Data Quality Control and Preprocessing

Genotype Quality Control: Apply standard QC procedures including:

- Remove individuals with no genotype data or outlying ethnicity

- Exclude SNPs with low frequency (minor allele frequency <1%) and high missingness rates

- Post-QC results: 4 individuals excluded for missing data, 1 for ethnicity, 43,986 SNPs excluded for low frequency, 109 for high missingness [23]

Phenotype Adjustment:

- For continuous phenotypes (e.g., systolic and diastolic blood pressure), adjust for covariates using linear regression

- Include covariates such as age, medication status, smoking status

- Calculate average residuals across multiple time points within individuals as final phenotype

Expression Data Integration:

- Utilize gene expression measurements from the same individuals with GWAS data

- Correct gene expression measurements for technical covariates (e.g., sex)

Filtering Strategy for Causal Analysis

Testing all possible trios of SNP, gene expression, and phenotype is computationally infeasible. Implement a filtering approach:

Expression-Phenotype Association:

- Perform association analysis to identify gene expression probes correlated with phenotypes

- Use linear regression with expression as predictor and phenotype as outcome

- Apply significance threshold (e.g., -log10 p-value >5)

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL) Mapping:

- For expression probes associated with phenotype, conduct genome-wide association with expression as outcome

- Use specialized software (e.g., FaST-LMM) that accounts for relatedness between individuals

- Retain SNPs showing association with expression probes

Trio Selection:

- Proceed with causal analysis only on filtered trios (SNP, expression, phenotype) showing significant associations

Alternative Approach: Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA)

As an alternative filtering strategy, WGCNA clusters genes into modules based on expression correlation:

- Group genes with similar function into a small number of modules

- Capture key functional mechanisms while reducing dimensionality

- Represent each module by an eigengene for downstream causal analysis

- This approach greatly reduces the number of relationships to test in causal modeling [23]

Causal Modeling Methods

Table 2: Comparison of Causal Modeling Approaches

| Method | Framework | Implementation | Model Selection | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) [23] | Regression-based | System of linear equations based on graphical model | Lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) | Tests biologically plausible models where SNP is causal, not affected |

| Bayesian Unified Framework (BUF) [23] | Bayesian model comparison | Partitions variables into subsets relative to SNP | Highest Bayes' factor | Flexible approach allowing model averaging and comparison |

The GWAS Catalog provides extensive summary statistics for downstream analysis. This protocol outlines the process for accessing and utilizing these data.

Data Access Methods

- Graphical User Interface: Browse and search via web interface at www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas

- Programmatic Access: Use RESTful API for high-throughput access (approximately 30 million API requests in 2021) [19]

- Direct Download: Access harmonized summary statistics from FTP site in standardized format

Author Submission System

For researchers generating new GWAS data:

- Submission Portal: Access deposition system at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/deposition

- Data Transfer: Use Globus for secure file transfer

- Validation: Apply Python-based validation tool (ss-validate) to ensure format compliance

- Licensing: Default CC0 license promotes maximal reuse of submitted data

As of July 2022, the Catalog had received 315 submissions comprising >30,000 GWAS, with 74% for unpublished data [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Causal Inference Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS Catalog API [19] | Programmatic data access | High-throughput retrieval of variant-trait associations | RESTful API, >30 million requests in 2021 |

| FaST-LMM [23] | Genome-wide association testing | Accounting for relatedness in eQTL mapping | Factored Spectrally Transformed Linear Mixed Model |

| WGCNA [23] | Gene co-expression network analysis | Dimensionality reduction for expression data | Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis |

| ss-validate [19] | Summary statistics validation | Pre-submission check of GWAS summary statistics | Python package available via PyPI |

| MR-Base [16] | Mendelian randomization platform | Systematic causal inference across phenome | Platform for billions of genetic associations |

Workflow Integration

The integration of multiple data resources and analytical methods enables a comprehensive approach to causal inference, as illustrated in the following workflow:

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for causal inference using public data resources. The pipeline progresses from data acquisition through quality control, filtering, causal modeling, and eventual target identification for therapeutic development.

Theoretical Foundation: The Instrumental Variable Framework in Genetics

Instrumental variable (IV) analysis is a powerful statistical method for causal inference in the presence of unmeasured confounding. In genetic epidemiology, this approach is implemented through Mendelian Randomization (MR), which uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to investigate causal relationships between modifiable exposures and health outcomes [24]. The method leverages Mendel's laws of inheritance—specifically the random segregation and independent assortment of alleles during gamete formation—creating a "natural experiment" that mimics randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [25] [24].

The core strength of MR lies in its ability to address two fundamental limitations of observational studies: unmeasured confounding and reverse causation. Since genetic variants are fixed at conception and cannot be altered by disease processes or environmental factors later in life, they provide a robust instrument that is generally unaffected by the confounding factors that typically plague observational epidemiology [25] [26]. This temporal precedence of genetic assignment helps establish the direction of causality [24].

Table 1: Core Assumptions for Valid Instrumental Variables in Genetic Studies

| Assumption | Description | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Relevance | The genetic variant must be strongly associated with the exposure of interest. | Genetic instruments should be robustly associated with the modifiable risk factor being studied, typically evidenced by genome-wide significance (p < 5×10⁻⁸) [25]. |

| Independence | The genetic variant must be independent of confounders of the exposure-outcome relationship. | Due to random allocation at conception, genetic variants should not be associated with behavioral, social, or environmental confounding factors [25] [24]. |

| Exclusion Restriction | The genetic variant must influence the outcome only through the exposure, not via alternative pathways. | The genetic instrument should affect the outcome exclusively through its effect on the specific exposure, requiring absence of horizontal pleiotropy [27] [25]. |

Figure 1: Causal diagram illustrating the core assumptions of Mendelian Randomization. The dotted red line represents horizontal pleiotropy, which violates the exclusion restriction assumption.

Key Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Basic Two-Sample MR Workflow

The two-sample MR design has become the standard approach in contemporary genetic causal inference, leveraging publicly available summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [24] [26]. This method estimates causal effects using genetic associations with the exposure and outcome derived from separate, non-overlapping samples [26].

Protocol: Two-Sample MR Analysis

Instrument Selection: Identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) robustly associated (p < 5×10⁻⁸) with the exposure from a large-scale GWAS. Clump SNPs to ensure independence (r² < 0.001 within 10,000 kb window) using a reference panel like the 1000 Genomes Project [26].

Data Harmonization: Extract association estimates for selected instruments with both exposure and outcome. Alleles must be aligned to the same forward strand, and palindromic SNPs should be carefully handled or removed [26].

Effect Estimation: Calculate ratio estimates (β̂XY = β̂GY/β̂GX) for each variant, where β̂GY is the genetic association with the outcome and β̂GX is the genetic association with the exposure.

Meta-Analysis: Combine ratio estimates using inverse-variance weighted (IVW) random effects meta-analysis: β̂IVW = (Σβ̂GX²/σ̂GY² × β̂XY) / (Σβ̂GX²/σ̂GY²) [26].

Sensitivity Analyses: Conduct pleiotropy-robust methods (MR-Egger, weighted median, MR-PRESSO) and assess heterogeneity using Cochran's Q statistic [26].

Figure 2: Standard workflow for two-sample Mendelian Randomization analysis using summary statistics from genome-wide association studies.

Advanced MR Methodologies for Addressing Pleiotropy

More sophisticated MR methods have been developed to address the critical challenge of horizontal pleiotropy, wherein genetic variants influence the outcome through pathways independent of the exposure [27] [26]. These methods employ different assumptions and statistical approaches to provide robust causal estimates.

Table 2: Advanced MR Methods for Addressing Invalid Instruments

| Method | Underlying Assumption | Application Protocol | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR-Egger | Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect (InSIDE) | Intercept tests for directional pleiotropy; slope provides causal estimate | Detects and corrects for unbalanced pleiotropy | Lower statistical power; susceptible to outliers |

| Weighted Median | Majority of genetic variants are valid instruments | Provides consistent estimate if >50% of weight comes from valid instruments | Robust to invalid instruments when majority valid | Requires majority valid instruments |

| Contamination Mixture | Plurality of valid instruments | Profile likelihood approach to identify valid instrument clusters | Handles many invalid instruments; identifies mechanisms | Complex computation; requires many instruments |

| MR-PRESSO | Outlier instruments deviate from causal estimate | Identifies and removes outliers; provides corrected estimate | Maintains power while removing outliers | May remove valid instruments with heterogeneous effects |

| RARE Method | Accounts for rare variants and correlated pleiotropy | Multivariable framework incorporating rare variants | Addresses impact of rare variants on causal inference | Requires specialized implementation |

Protocol: Contamination Mixture Method

The contamination mixture method is a robust approach that operates under the "plurality of valid instruments" assumption, meaning the largest group of genetic variants with similar causal estimates represents the valid instruments [26].

Likelihood Specification: For each genetic variant j, specify a two-component mixture model for the causal estimate θ̂j:

- Valid instrument component: θ̂j ~ N(θ, σj²)

- Invalid instrument component: θ̂j ~ N(0, τ² + σj²) where θ is the true causal effect, σj² is the variance of θ̂j, and τ² is the overdispersion parameter [26].

Profile Likelihood Optimization: For candidate values of θ, determine the optimal configuration of valid/invalid instruments by comparing likelihood contributions:

- Variant j classified as valid if: ϕ(θ̂j; θ, σj²) > ϕ(θ̂j; 0, τ² + σj²) where ϕ(·) is the normal density function [26].

Point Estimation: Identify θ̂ that maximizes the profile likelihood function across all candidate values.

Uncertainty Quantification: Construct confidence intervals using likelihood ratio test, which may yield non-contiguous intervals indicating multiple plausible causal mechanisms [26].

Application in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Causal Inference for Exposure-Outcome Relationships

MR has been extensively applied to investigate causal relationships between various exposures and disease outcomes, spanning metabolic traits, lifestyle factors, and molecular phenotypes. A prominent example involves the causal effect of lipids on coronary heart disease (CHD). While observational studies consistently showed associations between HDL cholesterol and reduced CHD risk, MR analyses revealed a more nuanced picture [26].

Key Finding: Application of the contamination mixture method to HDL cholesterol and CHD identified a bimodal distribution of variant-specific estimates, suggesting multiple biological mechanisms. One cluster of 11 variants was associated with increased HDL-cholesterol, decreased triglycerides, and decreased CHD risk, with consistent directions of effects on blood cell traits, suggesting a shared mechanism linking lipids and CHD risk mediated via platelet aggregation [26].

Protocol: Drug-Target Mendelian Randomization

Drug-target MR represents a powerful application for prioritizing molecular targets for pharmaceutical development [25].

Instrument Selection: Select genetic variants within or near the gene encoding the drug target that are associated with the target's expression or protein activity, using data from expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) or protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) studies [25].

Colocalization Analysis: Perform statistical colocalization (e.g., with COLOC, eCAVIAR, or SuSiE) to ensure the same genetic variant is responsible for both the molecular trait (expression/protein) and disease outcome associations [28].

Causal Estimation: Apply two-sample MR to estimate the effect of target perturbation on clinical outcomes.

Side-effect Profiling: Extend MR analyses to potential adverse effects by examining the effect of genetic instruments on multiple health outcomes.

Evidence shows that genetically supported targets have higher success rates in phases II and III clinical trials, making MR an invaluable tool for optimizing resource allocation in drug development [25].

Integration with Multi-omics Data

Modern MR frameworks have expanded to incorporate diverse omics data layers, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, enabling deeper understanding of causal biological pathways [29].

Protocol: Transcriptome-Wide Conditional Variational Autoencoder (TWAVE)

TWAVE represents an innovative integration of generative machine learning with causal inference to identify causal gene sets responsible for complex traits [29].

Data Preparation: Collect transcriptomic data for baseline and variant phenotypes from relevant tissues (e.g., peripheral blood mononuclear cells for allergic asthma, gastrointestinal tissue for inflammatory bowel disease) [29].

Model Training: Train a conditional variational autoencoder (CVAE) with three loss components:

- Reconstruction loss: Measures accuracy of input data reconstruction

- Kullback-Leibler divergence: Regularizes latent space structure

- Classification loss: Ensures latent space distinguishes phenotype classes [29]

Generative Sampling: Generate representative transcriptomic profiles for each phenotype by sampling from the conditional distributions in the latent space.

Causal Optimization: Apply constrained optimization to identify causal gene sets whose perturbation responses best explain phenotypic differences, using experimentally measured transcriptional responses to gene perturbations (knockdowns/overexpressions) [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Instrumental Variable Analysis with Genetic Data

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Summary Data | GWAS Catalog, UK Biobank, FinnGen, Biobank Japan | Source of genetic association estimates for exposures and outcomes | Instrument selection and effect size extraction for two-sample MR |

| Colocalization Methods | COLOC, eCAVIAR, SuSiE, PWCoCo | Statistical determination of shared causal variants across traits | Prioritizing causal genes at associated loci; validating instrument specificity |

| MR Software Packages | TwoSampleMR (R), MR-PRESSO, MendelianRandomization (R) | Implementation of MR methods and sensitivity analyses | Comprehensive MR analysis workflow from data harmonization to causal estimation |

| Pleiotropy-Robust Methods | MR-Egger, weighted median, contamination mixture, mode-based estimation | Causal estimation robust to invalid instruments | Addressing horizontal pleiotropy with different violation patterns |

| Gene Perturbation Databases | CRISPR screens, DepMap, GTEx, UKB-PPP | Data on transcriptional responses to gene perturbations | Inferring causal gene sets and biological mechanisms in advanced MR |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its considerable utility, MR faces several methodological challenges that represent active areas of methodological development. Weak instrument bias remains a concern when genetic variants have small associations with the exposure, potentially leading to biased causal estimates [24]. Horizontal pleiotropy continues to be the most significant threat to MR validity, though numerous robust methods have been developed to address it [27] [26]. Selection bias can affect MR estimates, particularly in biobank-based studies where participation is non-random [30].

Future methodological developments are focusing on several frontiers. Family-based MR designs offer advantages by controlling for population stratification and assortative mating, with recent extensions like MR-DoC2 showing reduced vulnerability to measurement error [27]. Nonlinear MR approaches are being developed to characterize dose-response relationships without imposing linearity assumptions, using methods like stratified MR and quantile average causal effects [30]. Multivariable MR frameworks such as the RARE method are expanding to incorporate rare variants and multiple correlated risk factors simultaneously [31]. Integration with machine learning approaches, as exemplified by TWAVE, represents a promising direction for identifying complex, polygenic causal mechanisms that traditional association studies might miss [29].

As biobanks continue to expand in size and diversity, and as multi-omics technologies become more widespread, MR methodologies will play an increasingly vital role in translating genetic discoveries into causal biological insights and ultimately into effective therapeutic interventions.

Core Methodologies: Mendelian Randomization and Applications in Drug Discovery

Mendelian Randomization (MR) is an epidemiological approach that uses measured genetic variation to investigate the causal effect of modifiable exposures on health and disease outcomes [32] [33]. The method serves as a form of natural experiment, leveraging the random assignment of genetic variants during gamete formation to create studies that are analogous to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) but conducted using observational data [34] [35]. The term "Mendelian Randomization" was coined by Gray and Wheatley, building upon principles first introduced by Katan in 1986 investigating cholesterol and cancer, and formally established in the epidemiological context by Smith and Ebrahim in 2003 [36] [34] [33].

The fundamental motivation for MR stems from repeated failures of conventional observational epidemiology, where numerous exposures (such as beta-carotene for lung cancer, vitamin E supplements for cardiovascular disease, and hormone replacement therapy) showed apparent benefits in observational studies that were not confirmed in subsequent RCTs [36] [35]. These discrepancies largely resulted from unmeasured confounding and reverse causation—limitations that MR aims to overcome through its unique study design [36] [35] [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Study Designs for Causal Inference

| Design Aspect | Observational Studies | Randomized Controlled Trials | Mendelian Randomization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confounding | High susceptibility | Minimal through randomization | Minimal through Mendelian inheritance |

| Reverse Causation | High risk | Low risk | Very low risk (genes fixed at conception) |

| Cost & Feasibility | Moderate | High (expensive, time-consuming) | Low (uses existing data) |

| Ethical Concerns | Minimal | Potentially significant | Minimal |

| Time Depth | Current exposure | Short-term during trial | Lifelong exposure effects |

Theoretical Foundation and Core Principles

Genetic Inheritance as Randomization

MR operates on two fundamental laws of Mendelian inheritance [34] [37]. The law of segregation states that offspring randomly inherit one allele from each parent at every genomic location. The law of independent assortment indicates that alleles at different genetic loci are inherited independently of one another (except for genes in close proximity on the same chromosome) [37]. These principles ensure that, in a well-mixed population, genetic variants are largely unrelated to confounding factors that typically plague observational studies, such as lifestyle, socioeconomic status, or environmental exposures [36] [35].

This random inheritance pattern makes genetic variants suitable instrumental variables (IVs)—a statistical concept pioneered by Wright in the 1920s [37] [33]. When genetic variants associated with a modifiable exposure are used as IVs, they can provide unbiased estimates of causal effects under specific assumptions [32] [35].

Core Assumptions of Mendelian Randomization

For valid MR inference, three core instrumental variable assumptions must be satisfied [37] [35] [38]:

- Relevance: The genetic variants must be robustly associated with the exposure of interest.

- Independence: The genetic variants must not be associated with any confounders of the exposure-outcome relationship.

- Exclusion Restriction: The genetic variants must affect the outcome only through the exposure, not via alternative pathways (no horizontal pleiotropy).

Only the first assumption (relevance) can be directly tested from the data; the other two require scientific reasoning and sensitivity analyses [37] [38]. Violations of these assumptions, particularly the third assumption regarding pleiotropy, represent the most significant challenges to valid MR inference [39] [38].

Table 2: MR Assumptions and Validation Approaches

| Assumption | Description | Validation Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Relevance | Genetic variant strongly associated with exposure | F-statistic >10, GWAS significance |

| Independence | No confounding of genetic variant-outcome relationship | Testing associations with known confounders, sibling designs |

| Exclusion Restriction | No direct effect of variant on outcome (no horizontal pleiotropy | MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO, heterogeneity tests |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

One-Sample vs. Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization

MR analyses can be implemented in either one-sample or two-sample frameworks [37]. In one-sample MR, genetic associations with both the exposure and outcome are estimated within the same dataset. This approach allows researchers to verify that genetic instruments are independent of known confounders and enables specialized analyses like gene-environment interaction MR [37]. The primary limitation is potential weak instrument bias, which tends to bias results toward the observational association [37].

In two-sample MR, genetic associations with the exposure and outcome come from different datasets [37] [38]. This approach has gained popularity with the increasing availability of large-scale GWAS summary statistics, as it often provides greater statistical power and facilitates the investigation of expensive or difficult-to-measure exposures [37] [38]. Weak instrument bias in two-sample MR typically drives results toward the null [37].

Standard Two-Sample MR Workflow

The following protocol outlines the standard workflow for conducting a two-sample MR analysis using publicly available summary statistics:

Step 1: Instrument Selection

- Identify genetic variants robustly associated with the exposure (typically genome-wide significant: p < 5×10^-8) [37] [38]

- Clump variants to ensure independence (r² < 0.001 within 10,000kb window) [37]

- Calculate F-statistic to assess instrument strength (F > 10 indicates sufficient strength) [37]

- Apply Steiger filtering to ensure variants are primarily associated with exposure rather than outcome [37]

Step 2: Data Harmonization

- Align effect alleles across exposure and outcome datasets

- Exclude palindromic SNPs with intermediate allele frequencies if strand orientation is ambiguous [37]

- Ensure all effect estimates correspond to the same allele increasing exposure levels

Step 3: Statistical Analysis

- Perform primary analysis using inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method with random effects [37] [33]

- Conduct sensitivity analyses using robust methods (MR-Egger, weighted median, MR-PRESSO) [37] [39]

- Test for directional pleiotropy via MR-Egger intercept and heterogeneity via Cochran's Q statistic [37]

Step 4: Validation and Interpretation

- Visualize results using scatter plots, forest plots, and funnel plots [37]

- Assess whether causal estimates are driven by invalid instruments via leave-one-out analysis

- Interpret findings in context of biological plausibility and existing evidence [25] [38]

Advanced MR Methodologies

As the field has evolved, several sophisticated MR approaches have been developed to address specific challenges:

cis-MR: This approach focuses on genetic variants within a specific gene region (typically cis-acting variants for molecular traits like protein or gene expression levels) [39]. cis-MR is particularly valuable for drug target validation, as it minimizes pleiotropy by leveraging variants with specific biological mechanisms [39] [25]. Recent methods like cisMR-cML effectively handle linkage disequilibrium and pleiotropy among correlated cis-SNPs [39].

Multivariable MR: This extension allows investigators to assess the direct effect of an exposure while accounting for other related traits, effectively addressing pleiotropy through measured mediators [32].

Non-linear MR: These methods investigate potential non-linear relationships between exposures and outcomes, moving beyond the standard linearity assumption [32].

Applications in Drug Development and Prioritization

MR has emerged as a powerful tool for drug target prioritization and validation in the pharmaceutical development pipeline [25]. By using genetic variants in or near genes encoding drug targets (e.g., proteins) as instruments, researchers can simulate the effects of lifelong modification of these targets on disease outcomes [39] [25].

Notable successes include:

- PCSK9 inhibitors: MR analyses provided early genetic evidence that PCSK9 inhibition would reduce cardiovascular risk, anticipating successful trial results [39] [25]

- IL-6R signaling: Genetically proxied IL-6R inhibition was associated with reduced coronary heart disease risk, supporting the development of therapeutic antibodies [25]

- CRP and cardiovascular disease: MR demonstrated that C-reactive protein is unlikely to be a causal factor in coronary heart disease, suggesting drugs targeting CRP may not be effective for cardiovascular risk reduction [35] [25]

Evidence indicates that drug targets with genetic support have approximately two-fold higher success rates in phases II and III clinical trials compared to those without such support [25]. This makes MR an invaluable approach for de-risking pharmaceutical development and optimizing resource allocation.

Table 3: MR Applications Across Biomedical Research

| Application Domain | Exposure Example | Outcome Example | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic Disease | LDL cholesterol | Coronary artery disease | Causal effect confirmed |

| Inflammation | C-reactive protein | Coronary heart disease | No causal effect |

| Cancer Epidemiology | Body mass index | Various cancers | Causal effect for multiple cancer types |

| Neurological Disorders | Educational attainment | Alzheimer's disease | Protective effect |

| Psychiatric Genetics | Cannabis use | Schizophrenia | Small increased risk |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Resources for Mendelian Randomization Studies

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| GWAS Summary Data | UK Biobank, GIANT, CARDIoGRAM, GWAS Catalog | Source of genetic associations for exposures and outcomes |

| Analysis Software | TwoSampleMR (R), MR-Base, MR-CML, MR-PRESSO | Implementation of MR methods and sensitivity analyses |

| LD Reference Panels | 1000 Genomes, UK Biobank LD reference | Account for linkage disequilibrium between variants |

| Pleiotropy Detection Tools | MR-Egger, HEIDI test, MR-PRESSO | Identify and correct for horizontal pleiotropy |

| Visualization Packages | forestplot, ggplot2 (R), funnel plot | Result presentation and assumption checking |

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

Despite its strengths, MR faces several important methodological challenges that researchers must acknowledge and address:

Horizontal Pleiotropy: When genetic variants influence the outcome through pathways other than the exposure of interest, results can be biased [39] [38]. Robust methods like MR-Egger, weighted median, and MR-cML have been developed to detect and correct for pleiotropy, but complete elimination of this bias is not always possible [39] [38].

Weak Instrument Bias: Genetic variants with weak associations with the exposure can lead to biased estimates, particularly in one-sample MR [32] [37]. Researchers should routinely report F-statistics to quantify instrument strength, with F > 10 indicating sufficient strength [37].

Population Stratification: If genetic variants are differentially distributed across subpopulations with different outcome risks, spurious associations may occur [33] [38]. This can be addressed by using genetic principal components as covariates and validating findings in diverse populations [37].

Time-Varying Effects: MR estimates represent lifelong effects of genetic predisposition, which may differ from effects of interventions later in life [35]. This discrepancy in timing must be considered when interpreting clinical relevance.

Collider Bias: Selection bias can occur when the study sample is conditioned on a common effect of the genetic variant and unmeasured factors [38]. This is particularly relevant in biobanks with low response rates.

A recent benchmarking study evaluating 16 MR methods using real-world genetic data found that no single method performs optimally across all scenarios, highlighting the importance of using multiple complementary approaches and sensitivity analyses [40]. The reliability of MR investigations depends heavily on appropriate instrument selection, thorough interrogation of findings, and careful interpretation within biological and clinical context [38].

The field of MR continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising future directions:

Integration of Multi-Omics Data: Combining genomic data with transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and epigenomic information will enable more comprehensive mapping of causal pathways from genetic variation to disease [25].

Drug Target MR: The application of MR specifically for drug target validation is expanding, with sophisticated methods like cis-MR providing robust evidence for prioritizing therapeutic targets [39] [25].

Population-Specific MR: As genetic studies diversify beyond European populations, MR applications in underrepresented groups will become increasingly important for global health equity [25].

Temporally-Varying MR: New methods are emerging to understand how genetic effects vary across the life course, providing insights into critical periods for intervention [35].

In conclusion, Mendelian randomization represents a powerful approach for causal inference in epidemiology and drug development. By leveraging random genetic assignment as a natural experiment, MR provides insights that complement both observational epidemiology and randomized trials. While methodological challenges remain, ongoing methodological innovations and growing genetic resources continue to expand MR's applications and robustness. When applied thoughtfully with appropriate attention to its core assumptions and limitations, MR serves as an invaluable component of the causal inference toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals.

Cis-Mendelian randomization (cis-MR) is an advanced statistical approach that uses genetic variants in a specific genomic region as instrumental variables (IVs) to investigate causal relationships between molecular traits (such as protein or gene expression levels) and complex diseases or outcomes [39]. Unlike conventional MR that utilizes genetic variants from across the entire genome, cis-MR focuses exclusively on cis-acting variants—typically single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located near the gene encoding the protein or molecular trait of interest [41]. This method has gained significant prominence in drug target validation as it provides a cost-effective path for prioritizing, validating, and repositioning drug targets by establishing causal evidence between target modulation and clinical outcomes [39].

The fundamental principle underlying cis-MR is that genetic variants in the cis-region of a drug target gene are likely to influence its expression or function while being less susceptible to confounding due to their random allocation at conception [42]. When applying cis-MR to drug target validation, a protein (as a potential drug target) or its downstream biomarker serves as the exposure, while corresponding cis-SNPs of the gene encoding the protein function as IVs [39]. This approach leverages the natural randomization of genetic variants to mimic randomized controlled trials, thereby providing evidence for or against the causal role of a drug target in a disease of interest.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Cis-MR in Drug Target Validation

| Feature | Description | Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Instruments | cis-acting variants (e.g., pQTLs) within the genomic region of the target gene | Provides natural genetic proxies for target modulation |

| Causal Inference | Establces directionality from target to disease outcome | Validates therapeutic hypothesis before clinical trials |

| Confounding Control | Reduces confounding through genetic randomization | Minimizes bias from observational associations |

| Study Design | Typically uses two-sample approach with summary statistics | Enables use of publicly available GWAS data resources |

Methodological Foundation and Assumptions

Core Assumptions of Valid Instrumental Variables

For valid causal inference using cis-MR, three fundamental instrumental variable assumptions must be satisfied [39] [41]:

- Relevance Assumption: The genetic variants must be robustly associated with the exposure (e.g., the protein or drug target).

- Independence Assumption: The genetic variants must be independent of any confounders of the exposure-outcome relationship.

- Exclusion Restriction: The genetic variants must affect the outcome only through the exposure, not via alternative pathways (no horizontal pleiotropy).

While the first assumption can be empirically tested, the second and third assumptions are generally untestable and more likely to be violated due to widespread horizontal pleiotropy, even among cis-SNPs in the same gene/protein region [39]. For instance, genetic variation in a transcription factor-binding site may influence binding affinity or efficiency, subsequently affecting the production of associated RNAs and proteins through distinct biological mechanisms [39].

Statistical Framework and Modeling Considerations

Cis-MR operates within the broader framework of Mendelian randomization but addresses specific challenges arising from the use of correlated cis-SNPs. The statistical model can be represented as:

- Exposure Model: ( X = \alpha0 + \alphaG G + \epsilon_X )

- Outcome Model: ( Y = \beta0 + \betaX X + \betaG G + \epsilonY )

Where ( X ) represents the exposure (drug target), ( Y ) the outcome (disease), ( G ) the genetic instruments (cis-SNPs), ( \alphaG ) the effect of SNPs on exposure, ( \betaX ) the causal effect of interest, and ( \beta_G ) the direct effect of SNPs on outcome (violating exclusion restriction if ≠ 0) [39].

A critical advancement in cis-MR methodology is the shift from modeling marginal genetic effects (as directly obtained from GWAS summary data) to modeling conditional/joint SNP effects [39] [41]. This distinction is essential when dealing with correlated SNPs in cis-MR, as failing to do so may introduce additional horizontal pleiotropy and lead to biased causal estimates.

Figure 1: Cis-MR Analysis Workflow for Drug Target Validation

Comparative Analysis of Cis-MR Methods

Available Methods and Their Properties

Several statistical methods have been developed to implement cis-MR analysis, each with distinct approaches to handling the challenges of correlated instruments and potential pleiotropy. The performance of these methods varies significantly under different genetic architectures and violation scenarios of IV assumptions.

Table 2: Comparison of Cis-MR Methods for Drug Target Validation

| Method | Key Features | LD Handling | Pleiotropy Robustness | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cisMR-cML | Constrained maximum likelihood; selects valid IVs | Models conditional effects | Robust to invalid IVs with correlated/uncorrelated pleiotropy | Requires sufficient IVs for selection [39] |

| Generalized IVW | Weighted regression with correlated SNPs | Accounts for LD structure | Assumes all IVs are valid | Biased with invalid IVs [41] |

| Generalized Egger | Extension of MR-Egger with correlated SNPs | Accounts for LD structure | Requires InSIDE assumption | Low power; sensitive to SNP coding [39] |

| LDA-Egger | LD-aware Egger regression | Explicit LD modeling | Requires InSIDE assumption | Sensitivity to outliers [39] |

Performance Benchmarking

Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated MR methods using real-world genetic datasets to provide guidelines for best practices. These comprehensive evaluations assess type I error control in various confounding scenarios (e.g., population stratification, pleiotropy), accuracy of causal effect estimates, replicability, and statistical power across hundreds of exposure-outcome trait pairs [40].

Simulation studies demonstrate that cisMR-cML consistently outperforms existing methods in the presence of invalid instrumental variables across different linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns, including weak (ρ = 0.2), moderate (ρ = 0.6), and strong (ρ = 0.8) correlation structures [39] [41]. The method maintains robust performance even when a proportion of cis-SNPs violate the IV assumptions through horizontal pleiotropic pathways.

Protocol for cisMR-cML Implementation

Stage 1: Data Preparation and Instrument Selection

Step 1: Define Genomic Region of Interest

- Identify the cis-region for the drug target gene, typically defined as ±100-500kb from the transcription start and end sites [39].

- Extract all genetic variants within this region from reference panels (e.g., 1000 Genomes Project).

Step 2: Obtain GWAS Summary Statistics

- Acquire summary statistics for exposure (protein/QTL data) and outcome (disease GWAS) from publicly available resources or consortium data.

- Ensure alignment of effect alleles across datasets and perform necessary quality control (e.g., minor allele frequency, imputation quality).

Step 3: Select Candidate Instrumental Variables

- Implement conditional and joint association analysis using GCTA-COJO to identify variants jointly associated with either exposure or outcome [39] [41].

- Include variants in set ( \mathcal{I}X \cup \mathcal{I}Y ) (associated with exposure or outcome) rather than only exposure-associated SNPs, which helps avoid additional horizontal pleiotropy.

Step 4: Estimate Linkage Disequilibrium Matrix

- Calculate the LD correlation matrix among selected variants using an appropriate reference panel matched to the study population.

- Ensure sufficient sample size in the reference panel to obtain stable LD estimates.

Stage 2: Model Fitting and Inference

Step 5: Convert Marginal to Conditional Effects

- Transform marginal GWAS estimates to conditional effects using the estimated LD matrix.

- This step is crucial for proper modeling of correlated instruments and mitigating unnecessary horizontal pleiotropy.

Step 6: Implement cisMR-cML Algorithm

- Apply the constrained maximum likelihood method under a constraint on the number of invalid IVs.

- Select the number of invalid IVs consistently using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).

- Execute data perturbation to account for uncertainty in model selection.

Step 7: Evaluate Model Assumptions and Sensitivity

- Assess robustness of causal estimates through sensitivity analyses.

- Evaluate potential violation of IV assumptions and their impact on causal estimates.

Figure 2: Causal Diagram for Cis-MR in Drug Target Validation

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of cis-MR for drug target validation requires specific data resources and computational tools. The following table outlines essential research reagents and their applications in the cis-MR workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Cis-MR

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in Cis-MR | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS Summary Data | UK Biobank, GWAS Catalog, FGED | Provides genetic association estimates for exposure and outcome | Large sample sizes, diverse phenotypes, standardized formats |

| Protein QTL Data | pQTL Atlas, SuSiE, Olink | Identifies genetic variants associated with protein abundance | Tissue-specific effects, multiple platforms, normalized values |

| LD Reference Panels | 1000 Genomes, gnomAD, HRC | Estimates correlation structure between cis-SNPs | Population-specific, dense genomic coverage, quality imputed |

| Software Tools | cisMR-cML, TwoSampleMR, MRBase | Implements statistical methods for causal inference | User-friendly interfaces, comprehensive method selection |

| Genome Annotation | ANNOVAR, Ensembl VEP | Functional annotation of significant cis-SNPs | Pathway context, regulatory elements, consequence prediction |

Application in Drug Target Discovery: Coronary Artery Disease Case Study

Proteome-Wide cis-MR Analysis

In a comprehensive drug-target analysis for coronary artery disease (CAD), researchers applied cisMR-cML in a proteome-wide application to identify potential therapeutic targets [39] [41]. The study utilized cis-pQTLs for proteins as exposures and CAD as the outcome, analyzing thousands of protein-disease pairs to systematically evaluate causal relationships.

The analysis identified three high-confidence drug targets for CAD:

- PCSK9: Already a validated target for lipid-lowering therapies, providing proof-of-concept for the approach

- COLEC11: A novel potential target involved in innate immunity and inflammation pathways

- FGFR1: Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1, implicating new biological mechanisms in CAD pathogenesis

Methodological Implementation

The case study exemplified several best practices in cis-MR application:

Instrument Selection: The analysis included conditionally independent cis-SNPs associated with either the protein exposure or CAD outcome, rather than restricting to exposure-associated variants only [41]. This approach enhanced the robustness of causal inference by accounting for potential pleiotropic pathways.

Handling of Correlation: The method properly modeled the conditional effects of correlated cis-SNPs using an estimated LD matrix from reference panels, avoiding the limitations of approaches that use marginal effect estimates [39].

Pleiotropy Robustness: cisMR-cML demonstrated robustness to invalid IVs through its constrained maximum likelihood framework, which consistently selected valid instruments while accounting for horizontal pleiotropy [39].

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Addressing Genetic Architecture Challenges

The implementation of cis-MR for drug target validation must consider several technical aspects of genetic architecture:

LD Structure: The correlation pattern among cis-SNPs significantly influences method performance. It is essential to accurately estimate the LD structure using appropriate reference panels matched to the study population [39].

Variant Selection: Conventional practice of selecting only exposure-associated SNPs may lead to using all invalid IVs when dealing with correlated SNPs. Including outcome-associated SNPs in the candidate IV set enhances robustness to pleiotropy [41].

Ethnogeographic Diversity: Genetic variations show evidence of ethnogeographic localization, with approximately 3-fold enrichment of binding site variation within discrete population groups [43]. The current Eurocentric bias in genetic databases likely underestimates the extent of target variation and its pharmacological implications, particularly for underrepresented ethnic groups.

Interpretation of Results

When interpreting cis-MR results for drug target validation, several considerations are crucial:

Causal Evidence vs. Therapeutic Effect: A significant causal effect supports the target's involvement in disease pathogenesis but does not necessarily predict the direction or magnitude of therapeutic effect from pharmacological intervention.

Target Tractability: Genetic validation does not guarantee druggability. Additional factors including chemical tractability, safety profile, and therapeutic window must be considered in target prioritization.

Biological Mechanisms: Cis-MR estimates represent the lifelong effect of target perturbation, which may differ from late-life pharmacological intervention due to developmental compensation or pathway redundancy.

Future Directions and Integration with Emerging Technologies

The field of cis-MR for drug target validation is rapidly evolving, with several promising directions for methodological advancement and biological integration: