Forecasting the Viral Arms Race: Key Challenges and AI-Driven Solutions in Predicting Viral Evolution

This article examines the formidable challenges in predicting viral evolution, a critical task for proactive vaccine design and pandemic preparedness.

Forecasting the Viral Arms Race: Key Challenges and AI-Driven Solutions in Predicting Viral Evolution

Abstract

This article examines the formidable challenges in predicting viral evolution, a critical task for proactive vaccine design and pandemic preparedness. It explores the fundamental biological constraints, such as epistasis and vast mutational space, that limit predictability. The review then details cutting-edge computational methodologies, including AI-driven language models and biophysical frameworks, that are being developed to overcome these hurdles. We further analyze the limitations of current models and the strategies for their optimization, and present rigorous validation paradigms comparing predictive performance against real-world viral emergence. Synthesizing insights from recent research, this article provides a comprehensive overview for scientists and drug developers on the transition from reactive tracking to proactive forecasting of high-risk viral variants.

The Fundamental Hurdles: Why Predicting Viral Evolution is Inherently Complex

FAQs: Core Concepts and Challenges

FAQ 1: What is the primary challenge in predicting viable viral variants from a vast mutational space? The principal challenge is epistasis—the phenomenon where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence or absence of other mutations in the genetic background. This non-additive interaction means that a mutation beneficial in one genetic context might be neutral or even deleterious in another, making evolutionary trajectories hard to predict. Approximately 49% of functional mutations identified in adaptive enzyme trajectories were neutral or negative on the wild-type background, only becoming beneficial after other "permissive" mutations had first been established [1]. This severely constrains predictability.

FAQ 2: How can we experimentally measure the functional impact of thousands of mutations? Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) is a key high-throughput technique. It involves creating a vast library of mutant genes or genomes, applying a selective pressure (e.g., antiviral treatment, host immune factors, or growth in a specific cell type), and then using next-generation sequencing to quantify the enrichment or depletion of every mutation before and after selection [2]. This links genotype to phenotype on a massive scale, revealing residues critical for viral replication, immune evasion, or drug resistance.

FAQ 3: What experimental strategies can help manage the problem of epistasis? Strategies include:

- Stability-Focused Filtering: When designing mutant libraries, computationally filter out mutations predicted to significantly destabilize the viral protein. This enriches libraries for functional variants, as many deleterious mutations are destabilizing [3].

- Stepwise Traversal: Mimic natural evolution by accumulating mutations step-by-step, re-assessing the fitness of each new mutation on the current genetic background rather than just the wild-type backbone. This can help identify positive epistasis that opens up new adaptive paths [1].

- Recombination: Crossing independently evolved, highly functional variants (that differ by many mutations) can help map the fitness landscape and identify which combinations of mutations are most productive [3].

FAQ 4: What is the mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2, and which mutation type is most common? Recent ultra-sensitive sequencing (CirSeq) of six SARS-CoV-2 variants indicates a mutation rate of approximately ~1.5 × 10⁻⁶ per base per viral passage. The mutation spectrum is heavily biased, dominated by C → U transitions, which occur about four times more frequently than any other base substitution [4].

FAQ 5: Which sequencing methods are best for detecting low-frequency variants in a viral population?

- Single-Genome Amplification (SGA): This method uses limiting-dilution PCR and Sanger sequencing to sequence individual viral templates from a mixed population. It prevents in vitro recombination, excludes Taq polymerase errors, and provides proportional representation of the viral population, offering deep resolution [5].

- Illumina-based Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): This provides ultra-deep analysis of the viral population, capable of identifying minor variants that SGA might miss. It is ideal for quantifying viral barcode lineages, identifying CTL escape sites, and integration site analysis [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low diversity or high proportion of non-functional clones in mutant library.

- Potential Cause 1: The library design included a high number of destabilizing mutations.

- Solution: Incorporate a computational filtering step during library design. Use protein modeling software (e.g., Rosetta) to calculate the predicted change in folding free energy (ΔΔG) for each single-point mutation and exclude those predicted to be highly destabilizing (e.g., ΔΔG below a set threshold). This can exclude up to ~50% of possible mutations without losing beneficial ones [3].

- Potential Cause 2: Inefficient or error-prone library synthesis.

- Solution: Optimize the synthesis protocol. Consider using circular polymerase extension reaction (CPER) or yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) systems for more stable and efficient propagation of viral cDNA, especially for large RNA virus genomes [2].

Problem: Inconsistent fitness measurements for mutations across different experiments.

- Potential Cause: The genetic background of the virus used in the experiment has changed, leading to epistatic interactions.

- Solution: Always sequence the entire backbone of your viral clone before and after experiments to track unintended changes. When reporting results, clearly state the exact genetic background (parent strain and all accumulated mutations) on which the measurements were made [1].

Problem: Difficulty in distinguishing beneficial mutations from neutral "hitchhikers" during directed evolution.

- Potential Cause: Beneficial mutations can be linked to neutral or slightly deleterious mutations on the same genome, causing them to co-enrich.

- Solution: After a selection round, perform clonal isolation and analysis. Isolate individual variants and test their fitness individually. Site-directed mutagenesis can also be used to reintroduce a specific mutation into a "clean" background to confirm its effect [1] [3].

Data Tables

Table 1: Quantifying Mutational Landscapes and Epistasis

| Metric | Value / Finding | Experimental System | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of epistatic functional mutations | ~49% of beneficial mutations were neutral or deleterious on the wild-type background | Analysis of 9 adaptive trajectories in enzymes | [1] |

| SARS-CoV-2 mutation rate | ~1.5 × 10⁻⁶ per base per viral passage | CirSeq of 6 variants (e.g., WA1, Alpha, Delta) in VeroE6 cells | [4] |

| Most common mutation type in SARS-CoV-2 | C → U transitions (~4x more frequent than other substitutions) | CirSeq mutation spectrum analysis | [4] |

| Proportion of predicted destabilizing single mutations | ~49.3% (2,839 of 5,758 possible single-site mutations) | Rosetta ΔΔG calculation on Kemp eliminase HG3 | [3] |

| Preferred sequence context for C→U mutations | 5'-UCG-3' | Nucleotide context analysis of SARS-CoV-2 mutation spectrum | [4] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Mutational Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Genetics System (plasmid/BAC) | Enables stable propagation and manipulation of viral genome as cDNA for mutagenesis. | Essential for constructing mutant libraries; systems with HCMV or T7 promoters allow direct viral RNA production [2]. |

| Circular Polymerase Extension Reaction (CPER) | A bacterium-free method to assemble and rescue infectious viral clones. | Reduces issues with bacterial toxicity and recombination of viral cDNA, improving library diversity [2]. |

| Viriation Tool (with NLP models) | Curates and summarizes functional annotations for viral mutations from literature. | Used in platforms like VIRUS-MVP to provide near-real-time functional insights on mutations [6]. |

| Single-Genome Amplification (SGA) | Provides high-fidelity, linked sequence data from individual viral templates in a quasispecies. | Critical for studying viral evolution, compartmentalization, and characterizing viral reservoirs without in vitro recombination [5]. |

| Barcoded Virus Libraries | Allows highly multiplexed tracking of specific viral lineages during complex infections. | Enables unprecedented identification and quantification of minor variants in plasma and tissues via NGS [5]. |

| VeroE6 Cells | A mammalian cell line highly susceptible to infection for viral culture and passage. | Preferred for COVID-19 research as it supports high viral replication and permits a higher degree of genetic diversity [4]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) for Viral Fitness

Objective: To determine the effect of all possible single-amino-acid substitutions in a viral protein on viral replicative fitness.

Methodology:

- Library Construction:

- Use site-directed mutagenesis or error-prone PCR on the gene of interest cloned within an infectious cDNA clone or a subgenomic plasmid to generate a comprehensive mutant library. Aim for coverage that includes all possible single-amino-acid changes [2].

- Virus Recovery:

- Application of Selective Pressure:

- Propagate the rescued virus library under the desired condition. This could be:

- Passaging in a specific cell type (e.g., human vs. animal cells) to study adaptation.

- Treatment with a neutralizing antibody or antiviral drug to identify escape mutations.

- Growth under innate immune pressure [2].

- Important: Use a low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.1) during passaging to minimize co-infection and complementation, which can mask the effect of deleterious mutations [4].

- Propagate the rescued virus library under the desired condition. This could be:

- Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Extract viral RNA from the virus population both pre- and post-selection.

- Prepare sequencing libraries for the target gene and perform high-depth next-generation sequencing (Illumina NGS is standard) [2] [5].

- Fitness Score Calculation: For each mutation, a fitness score is calculated by comparing its frequency in the post-selection population to its frequency in the pre-selection population (or the plasmid library), often using a log2 ratio. Normalize scores to synonymous mutations, which are generally assumed to be neutral [2].

Protocol 2: Stability-Informed Library Design for Directed Evolution

Objective: To create a "smart" mutant library enriched for functional, well-folded protein variants by excluding predicted destabilizing mutations.

Methodology:

- Saturation List Definition:

- Define the set of residues to saturate based on the experimental goal (e.g., all residues within 6 Å of the active site, all surface residues, or the entire protein) [3].

- In silico Stability Filtering:

- For every residue in the saturation list, calculate the predicted change in folding free energy (ΔΔG) for all 19 possible amino acid substitutions. Use a computational tool like the Cartesian ΔΔG protocol in the Rosetta software suite [3].

- Set a ΔΔG threshold (e.g., -0.5 Rosetta Energy Units) and exclude all mutations predicted to be more destabilizing than this threshold from the final library design.

- Oligo Pool Design and Gene Synthesis:

- Design DNA oligonucleotides (oligos) covering the entire gene, incorporating the filtered set of mutations. This can be done using short oligo fragments (e.g., ~200 bp) that are later assembled into full-length genes via overlap extension PCR [3].

- Library Assembly and Screening:

- Assemble the full-length gene library and clone it into an appropriate expression vector.

- Screen or select the resulting variant library for the desired function (e.g., catalytic activity, binding affinity). The enriched library will have a higher probability of containing improved, stable variants, accelerating the engineering process [3].

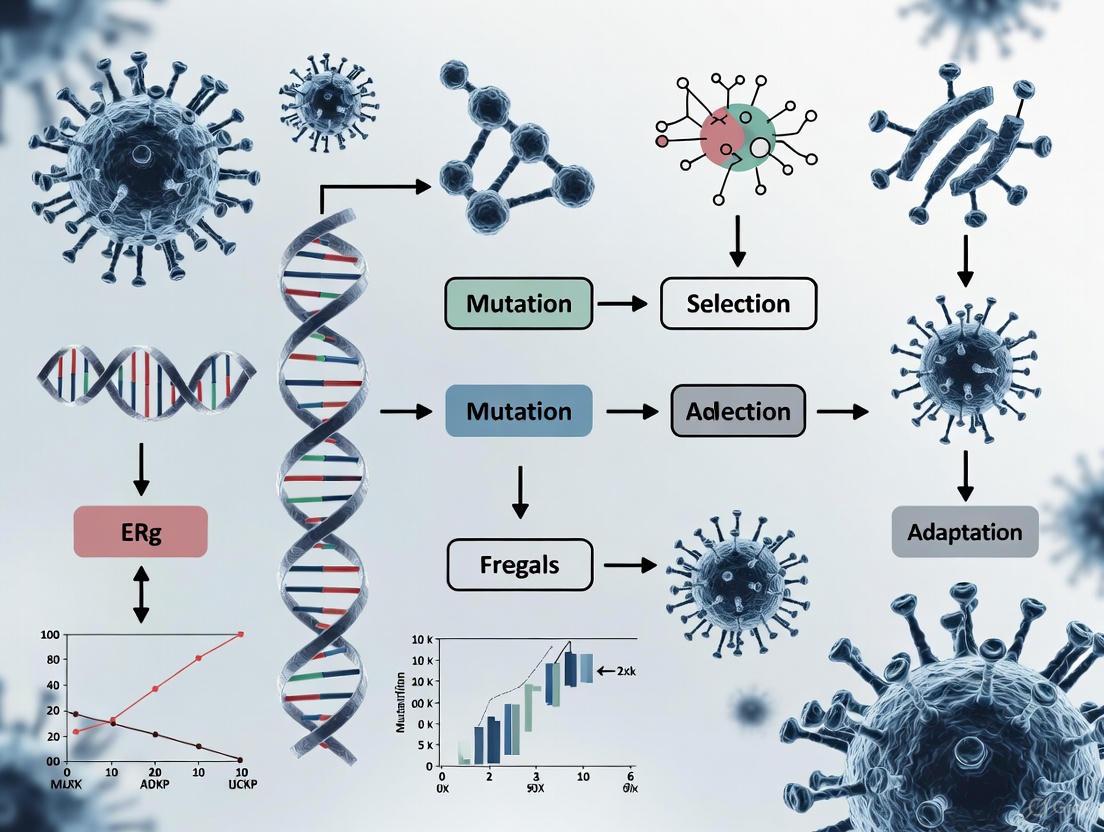

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

DMS Workflow for Viral Fitness

Epistasis in Evolutionary Trajectories

Stability-Informed Library Design

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Fitness Profiling and Sequence Analysis

Q: My fitness profiling experiment identifies functional residues that are not evolutionarily conserved. Are these results valid?

- A: Yes, this is a recognized and biologically significant phenomenon. Conventional sequence conservation analysis can produce both false positives (conserved but functionally silent residues) and false negatives (functional but non-conserved, type-specific residues) [7]. Your results likely highlight type-specific functional residues, which are prevalent but not identifiable through conservation analysis alone. You can validate these findings by coupling the fitness profiling data with computational protein stability predictions to distinguish residues essential for function from those critical for structural stability [7].

Q: How can I experimentally identify functional residues in a viral protein without relying on sequence conservation?

- A: A proven methodology involves coupling high-throughput experimental fitness profiling with computational protein stability prediction [7].

- Create Mutant Libraries: Use a "small library" strategy where you generate a mutant library (e.g., via error-prone PCR) for a region coverable by a single sequencing read. This ensures only one mutation per genome is present, simplifying fitness calculations [7].

- Perform Fitness Selection: Rescue the mutant virus library and passage it in a relevant cell line (e.g., A549 cells for influenza) to apply selective pressure [7].

- Deep Sequencing & Analysis: Sequence the plasmid library (pre-selection) and the viral population post-selection. Identify mutations that change in frequency to calculate fitness effects [7].

- Integrate Stability Data: Use available protein structural information to computationally predict the stability effect of each substitution. This integration helps pinpoint residues under functional constraint, independent of their conservation status [7].

Q: What could explain sudden, rapid evolutionary bursts in a viral population maintained in a constant laboratory environment?

- A: In a constant environment, where external triggers are absent, evolutionary bursts can be caused by endogenous factors [8].

- Primary Cause: Chromosomal rearrangements, particularly segmental duplications, are a major trigger for the strongest bursts, as they can create new genetic material for innovation [8].

- Other Mechanisms: Bursts can also be initiated by fitness valley crossing (where a deleterious mutation is fixed, potentially leading to a fitter genotype) or movement along neutral ridges (neutral mutations that eventually lead to a beneficial one) [8].

- Troubleshooting: If you observe such bursts, analyze your genomic data not just for single-nucleotide substitutions, but also for larger structural variations and duplications.

Predictive Modeling and Variant Forecasting

Q: How can I accurately predict which viral variants will become dominant, given that mutations often interact (epistasis)?

- A: Previous models that did not account for epistasis had limited accuracy. For more robust predictions, use a biophysics-aware model that quantitatively links viral fitness to specific biophysical properties [9].

- Key Parameters: Model the variant's binding affinity to host receptors and its ability to evade neutralizing antibodies [9].

- Incorporating Epistasis: Ensure the model explicitly factors in epistasis—the phenomenon where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of others. This is essential because evolution is non-linear, and epistatic interactions can unlock new adaptive pathways [9].

Q: We have limited experimental capacity. How can we prioritize which variants to test for transmissibility and immune evasion?

- A: Implement an AI-driven active learning framework like VIRAL (Viral Identification via Rapid Active Learning) [9].

- Workflow: This framework combines a biophysical model with artificial intelligence to iteratively select the most promising variant candidates for experimental testing [9].

- Efficiency: This approach can identify high-risk SARS-CoV-2 variants up to five times faster than conventional methods, requiring less than 1% of the experimental screening effort [9].

- Procedure: The AI proposes candidates based on predicted fitness; you test these experimentally and feed the results back into the model to refine subsequent predictions, creating a highly efficient feedback loop.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: High-Throughput Fitness Profiling of a Viral Protein

This protocol is adapted from the "small library" approach used to profile the influenza A virus PA polymerase subunit [7].

Library Design and Construction:

- Amplicon Generation: Use error-prone PCR to introduce random mutations into a 240 bp segment of the target gene.

- Vector Preparation: Generate the corresponding vector backbone via high-fidelity PCR.

- Cloning: Digest both the mutated amplicon and the vector with type IIs restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI/BsmBI) and ligate them to create the plasmid mutant library. Aim for a library of ~50,000 clones for sufficient coverage [7].

Virus Rescue and Selection:

- Transfection: Co-transfect the plasmid mutant library with the remaining wild-type plasmids of the viral reverse genetics system into a packaging cell line (e.g., 293T cells) [7].

- Infection: Harvest the rescued viral mutant library and use it to infect a susceptible cell line (e.g., A549 cells) for 24 hours to apply selective pressure [7].

Sequencing and Fitness Calculation:

- Sample Preparation: Subject the initial plasmid mutant library (DNA control), the post-transfection library, and the post-infection library to deep sequencing [7].

- Variant Frequency Analysis: Map sequencing reads to the reference genome and count the frequency of each mutation in the pre- and post-selection populations.

- Fitness Score: Calculate the relative fitness of a mutation based on the change in its frequency after selection. A mutation that enriches is likely beneficial or functionally important, while one that depletes is likely deleterious.

Protocol: Forecasting High-Risk Variants with VIRAL Framework

This protocol outlines the use of the VIRAL (Viral Identification via Rapid Active Learning) framework for SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [9].

Define the Prediction Goal: Clearly state the objective, such as identifying spike protein mutations that enhance ACE2 binding affinity and/or confer antibody evasion.

Implement the Biophysical Model:

- Develop or use an existing model that computes viral fitness based on biophysical parameters. The model must incorporate epistatic interactions between mutations [9].

Integrate Active Learning Loop:

- The AI proposes a small batch of variant candidates predicted to have the highest fitness.

- These candidates are synthesized and tested experimentally for binding and neutralization.

- The experimental results are fed back into the model to refine its future predictions.

Validation: The process iterates until high-fitness variants are identified with high confidence. The output is a ranked list of variants most likely to become dominant.

Quantitative Data on Viral Evolution

Table 1: Causes of Evolutionary Bursts in Viral Populations in a Constant Environment [8]

| Cause of Burst | Description | Relative Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Segmental Duplication | Duplication of a genomic segment, providing new material for evolution. | Major trigger for the strongest bursts. |

| Fitness Valley Crossing | Fixation of a deleterious mutation that eventually allows access to a fitter genotype. | Occurs occasionally. |

| Neutral Ridge Traveling | Neutral mutations that do not affect fitness until a beneficial mutation is found. | Occurs occasionally. |

Table 2: Performance of Predictive Frameworks for Viral Variants [9]

| Framework / Method | Key Feature | Reported Efficiency Gain |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional Approaches | Often lacks epistasis; tests variants broadly. | Baseline (1x) |

| VIRAL (AI + Biophysical Model) | Incorporates epistasis; focuses experiments via active learning. | Identifies variants 5x faster, using <1% of experimental screening. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Fitness Profiling Workflow

Fitness Landscape and Evolutionary Bursts

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Viral Fitness and Evolutionary Studies

| Tool / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Genetics System | Rescues infectious virus from plasmid DNA; essential for introducing mutant libraries. | 8-plasmid system for Influenza A/WSN/33 [7]. |

| "Small Library" Mutagenesis | Generates mutant libraries with only one mutation per genome, simplifying fitness analysis. | 240 bp amplicon covered by a single sequencing read [7]. |

| Type IIs Restriction Enzymes | Enables seamless, directional cloning of mutated amplicons into the vector backbone. | BsaI or BsmBI [7]. |

| Deep Sequencing Platform | Tracks the frequency of thousands of mutations before and after selection in parallel. | Illumina MiSeq [7]. |

| Biophysical Modeling Software | Predicts how mutations affect viral traits like receptor binding and antibody escape. | Core component of the VIRAL forecasting framework [9]. |

| Evolutionary Simulation Platform | Models long-term viral evolution in silico to test hypotheses and study dynamics. | Aevol platform for simulating virus-like genomes [8]. |

| Software Packaging (Conda/Bioconda) | Manages tool dependencies and installation, ensuring computational reproducibility. | Simplifies use of complex evolutionary bioinformatics tools [10]. |

| Integrative Framework (Galaxy) | Provides a unified web interface for combining multiple analytical tools into workflows. | Offers access to hundreds of tools without command-line installation [10]. |

In the field of viral evolution, a significant challenge complicates predictions: epistasis, the phenomenon where the effect of a genetic mutation depends on the presence of other mutations in the genome [11]. This non-linearity means that the fitness effect of a mutation in one viral variant may be beneficial, but the same mutation could be neutral or even deleterious in the genetic background of a different variant [11] [12]. For researchers forecasting the emergence of high-risk viral strains, this interaction creates a complex, rugged fitness landscape where evolutionary paths are difficult to anticipate. The ability to predict which variants will dominate, such as in influenza or SARS-CoV-2, is therefore substantially hampered by these unpredictable genetic interactions [13] [14]. Understanding and accounting for epistasis is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical step toward improving the accuracy of evolutionary forecasts and developing more resilient therapeutic strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is epistasis, and why is it a "challenge" in my viral variant research? Epistasis refers to genetic interactions where the effect of one mutation is dependent on the genetic background of other mutations [11]. It is a challenge because it violates the assumption of additivity that underpins many simple predictive models. When epistasis occurs, you cannot simply add up the individual effects of mutations to know a variant's overall fitness. This non-linearity makes it difficult to forecast which viral genotypes will emerge and become dominant, complicating tasks like vaccine selection and drug development [13] [15].

Q2: Are there predictable patterns of epistasis, or are all interactions completely idiosyncratic? Research shows that while specific interactions can be unique, global patterns often emerge. The most commonly observed pattern is "diminishing-returns" epistasis, where a beneficial mutation has a smaller fitness advantage in already-fit genetic backgrounds compared to less-fit backgrounds [11]. Conversely, "increasing-costs" epistasis describes deleterious mutations becoming more harmful in fitter backgrounds [11]. However, the shape and strength of these global patterns can themselves be altered by environmental factors like drug concentration [15].

Q3: How does the environment influence epistasis in my experiments? The environment can powerfully modulate epistatic interactions. For example, a study on P. falciparum showed that the same set of drug-resistance mutations exhibited diminishing-returns epistasis at low drug concentrations but switched to increasing-returns epistasis at high concentrations [15]. This means that the genetic interactions you map in one environmental condition (e.g., a specific drug dose) may not hold true in another. Your experimental conditions are not just a backdrop; they are an active participant in shaping the fitness landscape.

Q4: What is the difference between global epistasis and idiosyncratic epistasis?

- Global Epistasis describes a consistent, predictable relationship between the fitness effect of a mutation and the fitness of its genetic background. It can often be captured by a simple mathematical function, making it somewhat predictable [11] [15].

- Idiosyncratic Epistasis describes interactions that are highly specific to particular combinations of mutations and cannot be predicted from general rules like background fitness. These require detailed, case-by-case experimental mapping [15].

The balance between global and idiosyncratic epistasis for a given set of mutations can be visualized on a "map of epistasis," and this position can shift with environmental change [15].

Q5: Can we still predict evolution despite widespread epistasis? Yes, but with limitations. Short-term predictions in controlled environments are most feasible [13]. Approaches include:

- Leveraging patterns of global epistasis to model the distribution of fitness effects [11].

- Using high-throughput deep mutational scanning to empirically measure interactions in a focal gene [11] [16].

- Applying co-occurrence analysis of mutation hotspots in sequence data to flag potential high-risk variants [14]. However, long-term prediction remains challenging due to environmental fluctuations and the accumulation of complex, higher-order genetic interactions [13] [16].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem 1: Unpredictable Fitness Measurements in Different Genetic Backgrounds

Symptoms: A mutation known to be beneficial in one viral strain shows neutral or deleterious effects when introduced into a new strain. Your fitness predictions fail when crossing genetic backgrounds.

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of idiosyncratic epistasis [11] [15]. The effect of your focal mutation is being modified by specific, unaccounted-for genetic variants in the new background.

Solutions:

- Map the Interaction: Systematically measure the fitness of the focal mutation across a panel of isogenic strains that differ at the other suspect loci.

- Quantify Epistasis: Calculate epistasis (ε) using the formula:

ε = log(f~12~/f~0~) - [log(f~1~/f~0~) + log(f~2~/f~0~)] where f~0~ is the ancestral genotype fitness, f~1~ and f~2~ are single mutant fitnesses, and f~12~ is the double mutant fitness [12].

- Account for Environment: Re-run your assays across a range of relevant environmental conditions (e.g., drug concentrations, host cell types) to see if the interaction is stable or context-dependent [15].

Problem 2: Inconsistent Evolutionary Trajectories in Replicate Populations

Symptoms: In experimental evolution studies, replicate populations started from the same genotype evolve along different genetic paths, leading to different adaptive outcomes.

Diagnosis: Epistasis can create a rugged fitness landscape with multiple peaks. Small, stochastic events early on (e.g., which beneficial mutation arises first) can send populations down different, inaccessible paths due to negative epistatic interactions between mutations [11].

Solutions:

- Increase Replication: Use a large number of replicate lines to fully capture the distribution of possible evolutionary outcomes.

- Deep Sequencing: Perform high-temporal-resolution whole-genome sequencing to identify the order and identity of fixed mutations.

- Reconstruct Histories: Genetically reconstruct the evolutionary histories in different orders to test for historically contingent effects, where the effect of a late mutation depends on earlier mutations that paved the way [11].

Problem 3: Poor Performance of Models Trained on Data from a Single Environment

Symptoms: A predictive model for variant fitness, trained on data from one environment (e.g., a specific drug dose), performs poorly when applied to data from a different environment.

Diagnosis: Gene-by-Environment (GxE) interactions are modulating the underlying epistatic interactions, effectively changing the topography of the fitness landscape [15].

Solutions:

- Incorporate Environmental Variance: Train your models on fitness data collected across a gradient of environmental conditions relevant to your forecasting goals.

- Use a "Map of Epistasis": For key mutations, quantify how the strength (variance of fitness effects) and nature (R² of global epistasis model) of epistasis change across environments, as shown in the table below [15].

- Model Underlying Traits: Consider if a non-linear mapping from an unobserved biophysical trait (e.g., protein stability) to fitness can explain the changing patterns across environments [11].

Table: How Drug Dose Modulates Global Epistasis for Different Mutations in P. falciparum DHFR [15]

| Mutation | Low Drug Dose Pattern | High Drug Dose Pattern | Change in Epistasis Strength | Change in Globalness (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C59R | Diminishing Returns | Increasing Returns | Constant (var ~1) | Decreases |

| I164L | Diminishing Returns | Diminishing Returns | Constant (var ~1) | Increases |

| N51I | Idiosyncratic | Weak Epistasis | Decreases | Variable |

| S108N | Partly Global | Highly Idiosyncratic | Constant | Decreases |

Key Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Epistasis

Protocol 1: Deep Mutational Scanning to Map a Local Fitness Landscape

Objective: To empirically measure the fitness effects of all single mutants and many double mutants within a viral gene of interest (e.g., the Spike protein) in a single, high-throughput experiment [11] [17].

Methodology:

- Library Construction: Use site-directed mutagenesis or synthetic gene synthesis to create a comprehensive library of viral gene variants, encompassing all single amino acid changes and a selected set of double mutants.

- Selection Experiment: Package the variant library into pseudoviruses and subject them to a selective pressure (e.g., convalescent serum, a monoclonal antibody, or a host cell line). The workflow for this process is outlined below.

- Deep Sequencing: Sequence the variant library before and after selection using high-throughput sequencing to quantify the frequency of each variant.

- Fitness Calculation: Calculate the relative fitness of each variant as the log~2~ ratio of its frequency after selection to its frequency before selection.

- Epistasis Calculation: Identify epistatic pairs by comparing the measured fitness of double mutants to the expected fitness under an additive or multiplicative model [12].

Protocol 2: Measuring Global Epistasis Across Genetic Backgrounds

Objective: To determine how the fitness effect of a focal mutation changes as a function of the fitness of its genetic background [11] [15].

Methodology:

- Background Selection: Select a diverse set of 10-15 genetically distinct variants (e.g., natural isolates or engineered strains) that span a wide range of fitness values. These will serve as your genetic backgrounds.

- Generate Isogenic Lines: Use reverse genetics to introduce the precise focal mutation into each of the selected genetic backgrounds, creating a matched set of mutant strains.

- Fitness Assays: In a controlled environment, perform head-to-head competition assays between each mutant strain and its respective parental background. Alternatively, measure growth rates or viral titers for each strain individually.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the fitness effect (Δf) of the focal mutation in each background as the fitness difference between the mutant and its parent. Plot Δf against the fitness of the parental background (f(B)).

- Model Fitting: Fit a linear (or other) regression model to the data. The slope and R² of this model describe the pattern and "globalness" of epistasis, respectively [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Epistasis Research in Viral Variants

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Mutant Library | Provides the genetic diversity to screen for interactions. | Can be generated for a single gene (e.g., Spike) via oligo synthesis [17]. |

| Pseudotyped Virus System | Safely study entry of variants for high-risk pathogens. | Allows testing of spike mutations without full BSL-3 constraints [14]. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies / Convalescent Sera | Provides selective pressure to map antibody escape. | Critical for defining the antigenic landscape [14]. |

| Susceptible Cell Lines | Host for viral replication and competition assays. | e.g., A549 cells expressing hACE2 for SARS-CoV-2 entry assays [14]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Quantify variant frequency pre- and post-selection. | Essential for Deep Mutational Scanning [11] [17]. |

| Reverse Genetics System | Engineer specific mutations into desired genetic backgrounds. | Key for testing causal effects and generating isogenic lines [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do my stochastic models of viral evolution become computationally prohibitive when simulating large population sizes, and how can I overcome this?

Answer: This is a common challenge when modeling viral populations where large wild-type populations coexist with small, stochastically emerging mutant sub-populations. Traditional fully stochastic algorithms, like Gillespie's method, become computationally expensive because the average time step decreases as the total population size increases [18] [19].

A recommended solution is to implement a hybrid stochastic-deterministic algorithm. This approach treats large sub-populations (e.g., established wild-type virus) with deterministic ordinary differential equations (ODEs), while simulating small, evolutionarily important sub-populations (e.g., nascent mutants) with stochastic rules. This method approximates the full stochastic dynamics with sufficient accuracy at a fraction of the computational time and allows for the quantification of key evolutionary endpoints that pure ODEs cannot capture, such as the probability of mutant existence at a given infected cell population size [18] [19].

FAQ 2: My analysis of viral sequence data fails to detect recombination events that I know are present. What are the primary technical challenges in recombination detection?

Answer: The accurate detection of recombination is methodologically challenging. A major hurdle is distinguishing genuine recombination from other evolutionary signals, particularly when the genomic lineage evolution is driven by a limited number of single nucleotide polymorphisms or when sequences are highly similar [20]. Furthermore, the statistical power to detect recombination is low when the same genomic variants arise independently in different lineages (convergent evolution) [21].

To improve detection, ensure you are using multiple analytical procedures specifically designed for this purpose. Methods vary and include those based on phylogenetic incompatibility, compatibility matrices, and statistical tests for the breakdown of linkage disequilibrium. Always use a combination of these tools, not just one, and be aware that next-generation sequencing technologies, while offering new opportunities, also present serious analytical challenges that must be considered [21].

FAQ 3: In the context of HIV, under what conditions does recombination significantly accelerate the evolution of drug resistance?

Answer: The impact of recombination is not constant and depends critically on the effective viral population size (Ne) within a patient. Stochastic models show that for small effective population sizes (e.g., around 1,000), recombination has only a minor effect, as beneficial mutations typically fix sequentially. However, for intermediate population sizes (104 to 105), recombination can accelerate the evolution of drug resistance by up to 25% by bringing together beneficial mutations [22].

The fitness interactions (epistasis) between mutations also determine the outcome. If resistance mutations interact synergistically (positive epistasis), recombination can actually break down these favorable combinations and slow down evolution. The predominance of positive epistasis in HIV-1 in the absence of drugs suggests recombination may not facilitate the pre-existence of drug-resistant virus prior to therapy [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Projection of Variant Emergence

Problem: Models fail to forecast the emergence of high-risk viral variants that combine multiple mutations.

Solution:

- Incorporate Epistasis: Update your fitness models to account for non-linear interactions between mutations. "Evolution isn't linear — mutations interact, sometimes unlocking new pathways for adaptation" [9]. Factoring in these relationships is key to forecasting the emergence of dominant variants.

- Implement Advanced Forecasting Frameworks: Adopt computational frameworks like VIRAL (Viral Identification via Rapid Active Learning), which combines biophysical models (e.g., spike protein binding affinity and antibody evasion capacity) with artificial intelligence. This framework can identify high-risk SARS-CoV-2 variants up to five times faster than conventional approaches, focusing experimental validation on the most concerning candidates [9].

- Validate with Multiscale Data: Use a multiscale model that quantitatively links biophysical features of viral proteins (like binding affinity) to a variant's likelihood of surging in global populations. Cross-reference model predictions with epidemiological data on variant frequency [9].

Issue 2: Modeling the Impact of Multiple Infection and Cell-to-Cell Transmission

Problem: The evolutionary consequences of multiple infection of cells, particularly via virological synapses, are neglected or oversimplified in the model.

Solution:

- Model Structure: Formulate your model to track cells infected with

icopies of the virus, whereiranges from 0 to a maximum N. Include separate transmission terms for free-virus infection (typically adding one virus genome) and synaptic transmission (which can addSviruses at once) [18] [19]. - Account for Intracellular Interactions: Within multiply infected cells, model key interactions:

- Complementation: Where a defective mutant is rescued by a functional virus co-infecting the same cell.

- Interference: Where an advantageous mutant has its fitness reduced by competition with co-infecting viruses.

- Use a Hybrid Algorithm: Apply a hybrid stochastic-deterministic approach to efficiently simulate this system, where the large population of singly infected cells is modeled deterministically, and the smaller sub-populations of multiply infected cells are modeled stochastically [18] [19]. This is crucial, as synaptic transmission can promote the co-transmission of distinct virus strains, enhancing the effects of complementation and interference, and thereby promoting viral evolvability.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Estimated Effective Population Size (Ne) of HIV from Various Studies

This parameter is critical for determining the stochastic versus deterministic dynamics of mutation and recombination [22].

| Study | Patient Group | Population Sampled | Gene(s) | Estimated Ne |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leigh Brown [22] | Untreated | Free virus | env | 1,000 - 2,100 |

| Nijhuis et al. [22] | Before & During Therapy | Free virus | env | 450 - 16,000 |

| Rodrigo et al. [22] | Before & During Therapy | Provirus | env | 925 - 1,800 |

| Rouzine and Coffin [22] | Untreated & On Therapy | Free virus/Provirus | pro | 100,000 |

| Seo et al. [22] | Untreated & On Therapy | Free virus/Provirus | env | 1,500 - 5,500 |

| Achaz et al. [22] | Untreated | Free virus | gag-pol | 1,000 - 10,000 |

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Approaches for Simulating Viral Evolution

A guide to selecting the appropriate modeling framework for your research question [18] [19].

| Method | Best Use Case | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Stochastic (e.g., Gillespie) | Small, well-mixed populations where all sub-populations are subject to stochasticity. | Precisely captures random fluctuations and extinction probabilities. | Computationally prohibitive for large population sizes. |

| Deterministic (ODEs) | Modeling the average behavior of very large populations where stochastic effects are minimal. | Computationally efficient; provides a single, clear trajectory for the system. | Cannot model the emergence of new mutants from zero; cannot compute distributions or probabilities of rare events. |

| Hybrid Stochastic-Deterministic | Large populations containing both large and very small sub-populations (e.g., acute HIV infection). | Balances accuracy and efficiency; allows calculation of evolutionary endpoints like mutant distributions. | More complex implementation than pure ODEs. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying the Impact of Recombination on Drug Resistance In Silico

This protocol outlines a stochastic population genetic model to simulate the emergence of drug resistance in HIV, incorporating mutation and recombination [22].

1. Model Formulation:

- Genome: Represent a viral genome as two loci with two alleles each (e.g., a/A and b/B), where lowercase denotes drug-sensitive wild-type and uppercase denotes drug-resistant mutants.

- Population: Model a finite population of N infected cells, each carrying one or two proviruses. The frequency of doubly infected cells is

f, making the total number of proviruses (1 + f)N. - Life Cycle: Simulate discrete generations with these stochastic steps:

- Infection: Target cells are infected by virions, which can be homozygous or heterozygous.

- Reverse Transcription: During this process, template switching between the two genomic RNA strands in heterozygous virions occurs at a defined recombination rate.

- Selection: Newly infected cells (now proviruses) undergo selection based on their genotype fitness in the presence of drug therapy.

2. Key Parameters:

- Mutation Rate (μ): Use ( 3.4 \times 10^{-5} ) per base pair per replication cycle [22].

- Effective Population Size (Ne): varied between 103 and 105 based on empirical estimates [22].

- Fitness Values: Assign fitness to different genotypes (ab, Ab, aB, AB) based on empirical data, exploring both additive and synergistic (epistatic) interactions.

- Recombination Rate: Define the probability of template switching per replication cycle.

3. Simulation and Output:

- Run multiple stochastic simulations to account for random drift.

- Primary output: The number of generations or the probability for the double mutant (AB) to reach fixation in the population under different recombination rates and population sizes.

Protocol 2: A Hybrid Stochastic-Deterministic Algorithm for Simulating Mutant Evolution in Acute HIV Infection

This protocol details a method to overcome computational bottlenecks when simulating viral evolution in large populations with rare mutants [18] [19].

1. Define the Mathematical Model:

- Use a compartmental model that includes both free-virus transmission and direct cell-to-cell synaptic transmission.

- Define compartments for uninfected cells (x0) and cells infected with

icopies of the virus (xi), whereiranges from 1 to N. - Incorporate parameters for infection rates, viral production, cell death, and the number of viruses transferred per synaptic event (S).

2. Implement the Hybrid Algorithm:

- Set a Threshold: Choose a population threshold (e.g., 100 cells). Sub-populations below this threshold are modeled stochastically.

- Algorithm Flow:

- At each time step, calculate the propensities of all possible events (infection, death, etc.).

- For sub-populations below the threshold, use a stochastic method (e.g., tau-leaping) to update their numbers.

- For sub-populations above the threshold, update their numbers deterministically using ODEs derived from the model's reaction rates.

- Ensure conservation rules are maintained when moving cells between stochastically and deterministically modeled compartments.

3. Application:

- Use this algorithm to study how multiple infection and intracellular complementation facilitate the spread of otherwise disadvantageous mutants, a process heavily promoted by virological synapses [18] [19].

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Workflow of a Hybrid Stochastic-Deterministic Model for Viral Evolution

Hybrid Model Logic Flow

Diagram 2: Recombination and Mutant Formation in a Heterozygous Virion

Viral Recombination Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Population Genetic Model (Stochastic) | To simulate the evolution of drug-resistant viral strains in finite populations, incorporating the interplay of mutation, recombination, genetic drift, and selection [22]. |

| Hybrid Stochastic-Deterministic Algorithm | A computational method to efficiently simulate mutant evolution in large viral populations (e.g., acute HIV) where very large (wild-type) and very small (mutant) sub-populations coexist [18] [19]. |

| Bioinformatic Recombination Detection Pipelines | Software tools for detecting, characterizing, and quantifying recombination events in viral sequence data, often leveraging high-throughput sequencing data [21]. |

| Multiscale Biophysical Model | A model that links quantitative biophysical features (e.g., protein binding affinity, antibody evasion) to viral fitness and variant spread in populations, often incorporating epistasis [9]. |

| VIRAL (Viral Identification via Rapid Active Learning) | A computational framework combining biophysical models with AI to accelerate the identification of high-risk viral variants that enhance transmissibility and immune escape [9]. |

The Predictive Toolkit: AI, Biophysical Models, and Integrative Frameworks

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Errors and Solutions

Problem: Model Fails to Converge During Training

- Symptoms: Training loss fluctuates wildly or plateaus at a high value; model generates nonsensical sequence predictions.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Data Preprocessing. Viral sequences may contain artifacts or mis-annotations.

- Solution: Implement a rigorous quality control pipeline. Use multiple sequence alignment (MSA) tools to verify sequence integrity and filter out outliers.

- Cause 2: Incorrect Hyperparameter Tuning. The learning rate may be too high, or the model architecture may be too complex for the available data.

- Solution: Perform a systematic hyperparameter sweep. Start with known values from similar studies (e.g., using a smaller transformer model) and use a validation set for guidance.

- Cause 3: Data Imbalance. The training set may overrepresent certain viral clades, causing the model to perform poorly on underrepresented variants.

- Solution: Apply data augmentation techniques or weighted loss functions to balance the influence of different sequence groups.

- Cause 1: Inadequate Data Preprocessing. Viral sequences may contain artifacts or mis-annotations.

Problem: Poor Generalization to Unseen Viral Variants

- Symptoms: Model performs well on training data but fails to accurately predict the fitness or properties of novel variants.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Epistatic Interactions Not Captured. The model may focus on single-point mutations and miss complex, interdependent mutations.

- Solution: Incorporate probabilistic graphical models or attention mechanisms that explicitly model interactions between distant sites in the sequence.

- Cause 2: Lack of Structural or Functional Context. The model is trained solely on sequence data without biological constraints.

- Solution: Integrate protein structure prediction tools (e.g., AlphaFold2) into the pipeline. Use the predicted structures as additional input features to ground the language model's predictions in biophysical reality.

- Cause 1: Epistatic Interactions Not Captured. The model may focus on single-point mutations and miss complex, interdependent mutations.

Technical Implementation Issues

Problem: Memory Overflow with Large Language Models

- Symptoms: Training runs crash with "out of memory" errors, especially with long sequence lengths.

- Solution:

- Reduce the batch size during training.

- Use gradient accumulation to simulate a larger batch size.

- Employ model parallelism or use libraries optimized for memory efficiency (e.g., DeepSpeed).

- Consider using a model with a more efficient attention mechanism, such as Longformer or Performer, for very long viral genomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What type of language model is best suited for analyzing viral sequences? A: While standard Transformer-based models (like BERT or GPT) are a good starting point, models tailored for biological sequences often perform better. Architectures like CNN-LSTM hybrids or models employing attention mechanisms trained on millions of diverse protein sequences (e.g., ESM, ProtTrans) have shown great promise as they inherently capture biophysical properties.

Q2: How much data is required to train a effective model for a specific virus? A: The amount of data required is highly variable. For well-studied viruses like Influenza or SARS-CoV-2, thousands of sequences may be sufficient for fine-tuning a pre-trained model. For emerging viruses with limited data, techniques like few-shot learning or transfer learning from models trained on broad viral families are essential. The quality and diversity of the data are often more critical than the sheer volume.

Q3: How can I validate that my model has learned biologically meaningful rules and is not just overfitting? A: Use a rigorous, multi-faceted validation approach:

- Hold-out Validation: Reserve a temporally recent set of variants (ones that emerged after your training data was collected) to test predictive accuracy.

- Wet-lab Collaboration: Collaborate with experimentalists to synthesize a few model-predicted high-fitness variants and test their viability in the lab (e.g., using pseudovirus assays). This is the gold standard.

- In-silico Mutagenesis: Systematically introduce mutations and check if the model's predictions align with known deleterious or advantageous mutations from literature.

Q4: What are the key computational resources needed for this research? A: A typical setup involves:

- Hardware: Access to high-performance computing (HPC) clusters or cloud computing platforms (AWS, GCP, Azure) is almost mandatory. Training large models requires multiple GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA A100 or V100) with substantial VRAM.

- Software: Python is the primary language, using deep learning frameworks like PyTorch or TensorFlow. Domain-specific libraries like Biopython are essential for sequence handling.

Experimental Protocol: Decoding Viral Grammar with a Transformer Model

Objective

To train a transformer-based language model to predict viable future viral variants by learning the evolutionary "grammar" from a curated dataset of historical viral genome sequences.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Data Curation & Preprocessing

- Source: Download all available nucleotide or amino acid sequences for your target virus (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein) from public databases like GISAID or NCBI Virus.

- Alignment: Perform a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) using tools like MAFFT or ClustalOmega to ensure all sequences are positionally homologous.

- Filtering: Remove sequences with excessive ambiguity (e.g., too many 'X' or 'N' characters) and deduplicate the dataset.

- Split: Split the data chronologically: e.g., sequences up to a certain date for training/validation, and sequences after that date for testing temporal generalization.

Model Architecture & Training

- Architecture: Implement a decoder-only Transformer model (GPT-style) or an encoder model (BERT-style). The input is the aligned sequence, tokenized at the amino acid or codon level.

- Training Objective: Use a masked language modeling (MLM) objective, where the model learns to predict randomly masked tokens in the sequence. This forces it to learn the contextual constraints of the sequence.

- Hyperparameters:

- Optimizer: AdamW

- Learning Rate: 1e-4 to 1e-5 (with a warmup schedule)

- Batch Size: As large as GPU memory allows (32, 64, 128).

- Training Epochs: Until validation loss plateaus (monitor closely to avoid overfitting).

Variant Prediction & Analysis

- Fitness Scoring: For a given wild-type sequence, generate in-silico all possible single-point mutants. The model's log-likelihood or perplexity score for each mutant can be used as a proxy for its predicted fitness (lower perplexity = higher fitness).

- Evolutionary Tracing: Use the attention weights from the model to identify which parts of the sequence the model deems most critical when making predictions. These "important" positions can be mapped onto 3D protein structures to suggest functional hotspots.

Experimental Validation (Collaboration)

- Design: Select a shortlist of model-predicted high-fitness and low-fitness variants for synthesis.

- Testing: Partner with a BSL-2/3 lab to test these variants for functionality (e.g., binding affinity, replication rate) using appropriate assays.

The workflow for this protocol is as follows:

Data Presentation

| Model Architecture | Training Data Size (Sequences) | Perplexity (↓) | Top-10 Accuracy (%) (↑) | Temporal Generalization Score* (↑) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 50,000 | 4.5 | 62 | 0.55 |

| Transformer (Base) | 50,000 | 3.1 | 78 | 0.71 |

| ESM-1b (Fine-tuned) | 50,000 | 2.4 | 85 | 0.82 |

| CNN-LSTM Hybrid | 50,000 | 3.8 | 70 | 0.63 |

*The Temporal Generalization Score is defined as the Pearson correlation between the model's predicted fitness score and the actual observed frequency of novel variants in the held-out test set over a 3-month period.

Table 2: In-silico Prediction vs. Experimental Validation for Selected Model-Predicted SARS-CoV-2 Variants

| Predicted Variant (Spike Protein) | Model Fitness Score (Perplexity) | Predicted Category | Experimental Binding Affinity (nM) (↓) | Experimental Replication Rate (Relative to WT) (↑) | Model-Experiment Concordance? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N501Y | 2.1 | High Fitness | 0.8 | 1.4 | Yes |

| E484K | 2.3 | High Fitness | 1.1 | 1.3 | Yes |

| A570D | 5.7 | Low Fitness | 12.5 | 0.7 | Yes |

| P681H | 2.9 | Neutral | 2.5 | 1.0 | Partial |

| K417T | 6.1 | Low Fitness | 15.2 | 0.6 | Yes |

Visualization of Core Concepts

Viral Grammar Decoding Workflow

Model Architecture Schematic

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Grammar Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Product / Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Protein Language Model (pLM) | Provides a strong foundational understanding of general protein sequence-structure relationships, enabling effective transfer learning for specific viruses. | ESM-2, ProtTrans |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Tool | Aligns homologous viral sequences to ensure positional correspondence, which is critical for accurate model training and analysis. | MAFFT, ClustalOmega |

| Deep Learning Framework | Provides the core software environment for building, training, and evaluating complex neural network models. | PyTorch, TensorFlow |

| Gradient Checkpointing Library | A software technique that reduces GPU memory consumption during training, allowing for the use of larger models or batch sizes on limited hardware. | torch.utils.checkpoint |

| Pseudovirus Assay System | A safe (BSL-2) experimental system to functionally validate model predictions by measuring the infectivity of predicted viral variants without handling live, high-containment viruses. | Commercial lentiviral pseudotype kits (e.g., for SARS-CoV-2) |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the necessary computational power (multiple GPUs, high RAM) to train large language models on millions of sequence data points in a feasible timeframe. | In-house cluster or Cloud (AWS, GCP) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a fitness model in the context of viral evolution, and why is it important? A fitness model is a computational framework that predicts the evolutionary success of a viral variant. It integrates quantitative traits like binding affinity (how strongly the virus attaches to a host cell receptor) and immune evasion (its ability to escape neutralization by antibodies) into a single fitness score. These models are crucial because they move beyond simply counting mutations; they help researchers anticipate which viral variants are likely to dominate, guiding the development of future vaccines and therapeutics [23] [13].

Q2: Our predictions of high-risk variants are often inaccurate. What key factors might we be missing? A primary challenge in evolutionary prediction is the reliance on incomplete data. Common missing factors include:

- Neoantigen Quality and Expression: It's not just the number of mutations, but their quality (strength of binding to MHC and T-cell receptors) and expression level that determine immune recognition. Down-regulation of highly immunogenic neoantigens is a key immune escape mechanism [24].

- Eco-evolutionary Feedback Loops: Viral evolution is shaped by its environment, including the host immune response. This creates feedback loops where the environment changes as the virus evolves, making long-term predictions challenging [13].

- Spatiotemporal Scales: Evolutionary rates and selective pressures differ between within-host and between-host dynamics. Integrating these scales is a significant hurdle [23].

Q3: How can AI help in designing vaccines against future viral variants? AI and computational biophysics enable a proactive approach to vaccine design. Methods like EVE-Vax can generate a panel of synthetic viral spike proteins designed to foreshadow potential future immune escape variants. This allows researchers to evaluate and optimize vaccines and therapeutics against predicted future strains, rather than only reacting to those that have already emerged [25].

Q4: What is the difference between a fitness model and a simple binding affinity measurement? While binding affinity is a critical component of fitness, a comprehensive fitness model incorporates a broader set of parameters. The table below outlines the key differences:

Table 1: Fitness Model vs. Binding Affinity

| Aspect | Fitness Model | Binding Affinity Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Holistic; integrates multiple selective pressures (e.g., infectivity, immune evasion, stability) | Narrow; focuses solely on virus-receptor interaction strength |

| Output | A predictive score for viral variant success and prevalence | A physical binding constant (e.g., KD) |

| Evolutionary Context | Dynamic; considers trade-offs and co-occurrence of mutations in a population | Static; a snapshot of one molecular property |

| Primary Use | Forecasting variant spread, guiding vaccine updates | Informing drug design, understanding entry mechanisms |

Q5: Our experimental evolution in cell culture does not match observations from patient samples. How can we improve our laboratory systems? Traditional monolayer cell cultures often provide an unnaturally permissive environment. To better mimic in vivo conditions, consider:

- Using Advanced Cell Models: Transition to non-tumoral cells, 3D cultures, or organoids. These systems better reflect selective pressures like the innate immune response [23].

- Incorporating Immune Components: Co-culture viruses with immune cells to simulate immune pressure and study immunoediting.

- Validating with Field Data: Constantly contrast findings from laboratory systems with sequencing and clinical data from natural infections to identify discrepancies and refine your models [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Predictive Power in Variant Fitness Models

Problem: Your computational model fails to accurately rank the fitness of emerging viral variants.

Solution: Follow this systematic troubleshooting protocol to identify and rectify the issue.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Predictive Power in Fitness Models

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Audit | Verify the quantitative data integrated into your model. Are you using only binding affinity (e.g., from docking) and ignoring immune evasion metrics? | A checklist of all parameters in your current model, identifying key gaps. |

| 2. Integrate Immune Evasion | Incorporate a neoantigen fitness cost metric. This measures the immunogenic strength of mutations based on MHC binding and T-cell receptor recognition potential, not just mutation count [24]. | Improved correlation between your model's predictions and observed variant prevalence in epidemiological data. |

| 3. Check for Trade-offs | Analyze if high binding affinity variants show a trade-off with other traits, like reduced viral stability or replication rate. Use multivariate analysis. | Identification of evolutionary constraints that prevent certain high-fitness genotypes from emerging. |

| 4. Validate Experimentally | Synthesize top-predicted variants and test them using pseudotyped virus entry assays in the presence of convalescent sera to measure functional immune escape [14]. | Experimental confirmation of your model's predictions, building confidence in its accuracy. |

Experimental Protocol: Pseudotyped Virus Entry Assay for Variant Validation

This protocol is used to functionally validate the infectivity and immune evasion capabilities of predicted high-risk variants.

- Plasmid Construction: Synthesize genes for viral spike proteins (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 Spike) encoding the wild-type and predicted high-risk variant sequences (e.g., S494P, V503I) [14].

- Virus Production: Co-transfect HEK-293T cells with:

- A spike protein plasmid (wild-type or variant).

- A packaging plasmid (e.g., psPAX2).

- A reporter plasmid (e.g., pLV with luciferase or GFP).

- Harvest and Titration: Collect pseudotyped virus supernatants at 48-72 hours post-transfection. Concentrate and quantify viral titer via p24 ELISA or RT-qPCR.

- Infection Assay: Infect target cells expressing the relevant viral receptor (e.g., A549-ACE2) with normalized amounts of pseudotyped viruses.

- Immune Evasion Test: Pre-incubate viruses with serial dilutions of neutralizing antibodies or convalescent patient serum before adding to cells.

- Quantification: Measure reporter signal (e.g., luciferase activity) 48-72 hours post-infection. Normalized luciferase activity is a proxy for viral entry efficiency. Compare variant entry efficiency and antibody resistance to the wild-type control.

Issue 2: Inconsistent Evolutionary Rates Across Timescales

Problem: The evolutionary rate you infer from recent outbreak data is much higher than the rate calculated from long-term archival sequences, leading to unreliable molecular dating.

Solution: This is a known challenge where short-term rates are systematically higher. Your analysis should account for this time-dependent rate phenomenon.

- Model Selection: Use phylogenetic software (e.g., BEAST2) that allows you to apply relaxed molecular clock models. These models do not assume a constant evolutionary rate across all branches of the phylogenetic tree.

- Incorporate Older Sequences: Integrate data from older isolates, permafrost samples, or archival specimens to calibrate your tree over longer timescales [23].

- Separate Analyses: Clearly state the timescale of your data. Avoid extrapolating a short-term rate to make predictions about long-term evolution.

Issue 3: Computational Strain in Binding Affinity Simulations

Problem: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations or mutational scanning of viral proteins (like the spike) are computationally expensive and slow, limiting the number of variants you can test.

Solution: Implement a hybrid AI-biophysics pipeline to improve efficiency.

- Initial Coarse Screening: Use a fast, statistical co-occurrence analysis of mutation hotspots in viral sequence databases to identify a shortlist of potentially high-risk variants [14].

- Focused Energetic Analysis: Apply rigorous computational methods only to the shortlisted variants. This includes:

- AI-Powered Prediction: Train a machine learning model on the results from step 2. The model can learn to predict binding affinity and fitness from sequence alone, allowing for rapid screening of millions of virtual variants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Fitness Modeling and Validation

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| EVE-Vax Computational Method [25] | AI-based method for designing viral antigens that foreshadow future immune escape variants for proactive vaccine evaluation. |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) & Sequencing Primers | For amplifying and sequencing viral genomes from clinical or environmental samples to track diversity. |

| HEK-293T Cell Line | A standard workhorse cell line for producing pseudotyped viruses for safe viral entry assays. |

| ACE2-Expressing Cell Line (e.g., A549-ACE2) | Target cell line for viruses that use the ACE2 receptor (e.g., SARS-CoV-2); essential for functional entry assays. |

| Luciferase Reporter Gene Plasmid | A standard reporter system packaged into pseudotyped viruses; luminescence upon infection quantifies viral entry efficiency. |

| Convalescent Sera or Monoclonal Antibodies | Used in neutralization assays to quantify the immune evasion capability of a viral variant. |

| Structure Prediction Software (e.g., AlphaFold2) | To generate 3D protein structures for viral variants when experimental structures are unavailable, for use in docking/MD simulations. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock Vina) | For initial, rapid in silico screening of binding affinity between viral proteins and host receptors or antibodies. |

| GISAID Database [23] | A global repository of influenza and coronavirus sequence data, essential for tracking real-world viral evolution and validating models. |

A primary challenge in modern virology and pandemic preparedness is the reactive nature of public health responses. By the time a new, high-risk viral variant is detected, it is often too late to adjust public policy or vaccine strategies effectively [9]. The field of viral evolutionary prediction aims to shift this paradigm from reactive tracking to proactive forecasting, allowing scientists to anticipate viral leaps before they threaten public health [9]. This endeavor is fraught with intrinsic challenges, including the non-linear nature of viral evolution, where the effect of one mutation can depend on the presence of others, a phenomenon known as epistasis [9]. Furthermore, the vast mutational space makes it practically impossible to test every possible variant experimentally [9].

Unified deep learning frameworks are emerging as a transformative solution to these challenges. These platforms are designed to handle multiple viruses and predict diverse phenotypic outcomes, such as transmissibility, immune evasion, and host interactions. They leverage artificial intelligence (AI) to integrate genomic, epidemiologic, immunologic, and fundamental biophysical information, creating models that can forecast the course of viral evolution [27] [28]. The core objective is to look at a viral genetic sequence and predict its evolutionary fate and functional consequences, a capability considered the holy grail of pandemic preparedness [28]. This technical support document outlines the specific issues, solutions, and experimental protocols for researchers employing these sophisticated frameworks.

FAQs: Core Concepts for Researchers

FAQ 1: What does "unified" mean in the context of these frameworks, and how does it differ from traditional models? A unified framework is designed to be broadly applicable across multiple viral species, rather than being built for a single specific virus like SARS-CoV-2. While many initial models were developed using COVID-19 data due to its extensive dataset availability, their architectures are intentionally designed for adaptability across RNA viruses [27]. This is achieved by focusing on fundamental biological and physical principles, such as binding affinity to human receptors and antibody evasion potential, which are common constraints shaping the evolution of many viruses [9].

FAQ 2: What types of multi-phenotype predictions can these frameworks perform? These frameworks move beyond single-trait prediction. They can be trained to jointly forecast multiple clinical and biological endpoints critical for risk assessment. For a respiratory virus, this could include simultaneous predictions for:

- Viral Fitness: Including transmissibility and binding affinity to host receptors [9].

- Immune Evasion: The ability to escape neutralizing antibodies from prior infection or vaccination [9] [27].

- Clinical Severity: Associations with patient outcomes such as overall survival or progression-free survival [29]. This multi-endpoint modeling provides a comprehensive profile of a variant's potential threat.

FAQ 3: My data is heterogeneous, combining genomic sequences, protein structures, and clinical outcomes. How can a unified framework handle this? This is a key strength of multimodal deep learning. These frameworks use specialized fusion techniques to integrate diverse data types. For instance, protein language models—AI models trained on millions of protein sequences—can convert raw viral and human protein sequences into meaningful numerical representations that capture evolutionary constraints [30]. These representations can then be combined with other data layers, such as biophysical properties or immune response data, within a single model to improve prediction accuracy for tasks like identifying human-virus protein-protein interactions [30].

FAQ 4: A major challenge is the "black box" nature of AI. How interpretable are these predictions for guiding experimental validation? Interpretability is a critical focus for newer frameworks. While complex models like neural networks can be opaque, there is a significant push towards developing interpretable AI. For example, some frameworks use decision-tree architectures that are powered by machine learning for optimization but result in a clear, visual model that clinicians and researchers can understand [29]. This allows users to see the specific molecular rules the model used to assign a variant to a high-risk category, thereby building trust and providing actionable insights for lab experiments.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Poor Model Generalization to Novel Viruses

- Symptoms: Your model, trained on SARS-CoV-2, performs poorly when making predictions for an unrelated virus like Influenza.

- Solutions:

- Leverage Transfer Learning: Start with a model pre-trained on a broad dataset (e.g., many RNA viruses or general protein sequences) and fine-tune it on a smaller, target-virus-specific dataset [27] [28].

- Incorporate Biophysical Grounding: Ensure your model incorporates fundamental biophysical features (e.g., binding affinity, structural stability) that are universal constraints on viral evolution, rather than relying solely on virus-specific genomic patterns [9].

- Benchmark Rigorously: Use standardized benchmark datasets, like those proposed in systematic reviews, to evaluate your model's performance across different viral contexts and identify specific weaknesses [31].

Problem: Handling Epistasis (Non-Linear Mutation Interactions)

- Symptoms: The model accurately predicts the effect of single mutations but fails when combinations of mutations arise, as their combined effect is non-linear.

- Solutions:

- Choose Architectures that Capture Interactions: Utilize deep learning models like transformers or recurrent neural networks that are inherently designed to model complex, long-range dependencies within sequence data [9] [28].

- Include Epistasis in Training: Explicitly train your model using data that includes paired or multiple mutations, not just single mutants. The VIRAL framework, for instance, overcame this limitation by factoring in these mutational relationships [9].

- Active Learning Cycles: Implement an active learning loop where the model's most uncertain predictions about mutation combinations are prioritized for experimental testing, creating a virtuous cycle of data improvement and model refinement [9].

Problem: Integrating and Managing Multi-Omics Data

- Symptoms: Model performance degrades or becomes unstable when trying to integrate disparate data types (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics).

- Solutions:

- Employ Multimodal Fusion Techniques: Adopt a framework specifically designed for multimodal data. These frameworks process each data type through a dedicated sub-model (encoder) and then fuse the representations in a later stage [30] [32].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply techniques like PCA or autoencoders to each high-dimensional omics layer before fusion to reduce noise and computational complexity [32].

- Address Data Distribution Shifts: Be aware that different omics data have different scales and distributions. Normalize and preprocess each data type appropriately to avoid having one domain dominate the model's learning process [32].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Forecasting Variant Dominance Using Biophysical AI

This protocol is based on the approach detailed by Harvard's Shakhnovich lab for forecasting which viral variants are likely to become dominant in populations [9].

1. Principle: Link quantitative biophysical features of viral proteins to viral fitness and use AI to rapidly screen mutational space.

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Data: Curated sequences of viral variants (e.g., spike protein sequences for SARS-CoV-2) and associated epidemiological data on variant frequency.

- Software: Computational biology tools for predicting protein binding affinity (e.g., molecular docking software) and immune evasion.

- Compute: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or cloud computing resources for running AI models.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Feature Calculation. For each variant sequence in your training set, compute key biophysical features. These include:

- Binding Affinity: The calculated binding strength between the viral protein (e.g., spike) and the host receptor (e.g., ACE2).

- Structural Stability: The estimated folding stability of the viral protein.

- Antibody Evasion Score: A metric predicting the variant's ability to escape a panel of known neutralizing antibodies.

- Step 2: Model Training. Train a machine learning model (e.g., a gradient boosting machine or neural network) to predict a variant's likelihood of becoming epidemiologically dominant based on the calculated biophysical features. The training label is typically a measure of variant frequency over time.

- Step 3: Incorporate Epistasis. Ensure the model architecture or training data can account for epistasis, where the effect of one mutation depends on other mutations present in the sequence [9].

- Step 4: In-silico Saturation Mutagenesis. Use the trained model to predict the fitness of all possible single-point mutations (and potentially combinations) in the viral protein of interest.

- Step 5: Active Learning Loop. Identify the mutations or variants for which the model is most uncertain. Prioritize these for in vitro experimental validation (e.g., pseudovirus neutralization assays). Feed the experimental results back into the model to retrain and improve its accuracy [9].

4. Analysis and Interpretation:

- The model outputs a ranked list of high-risk mutations/variants.