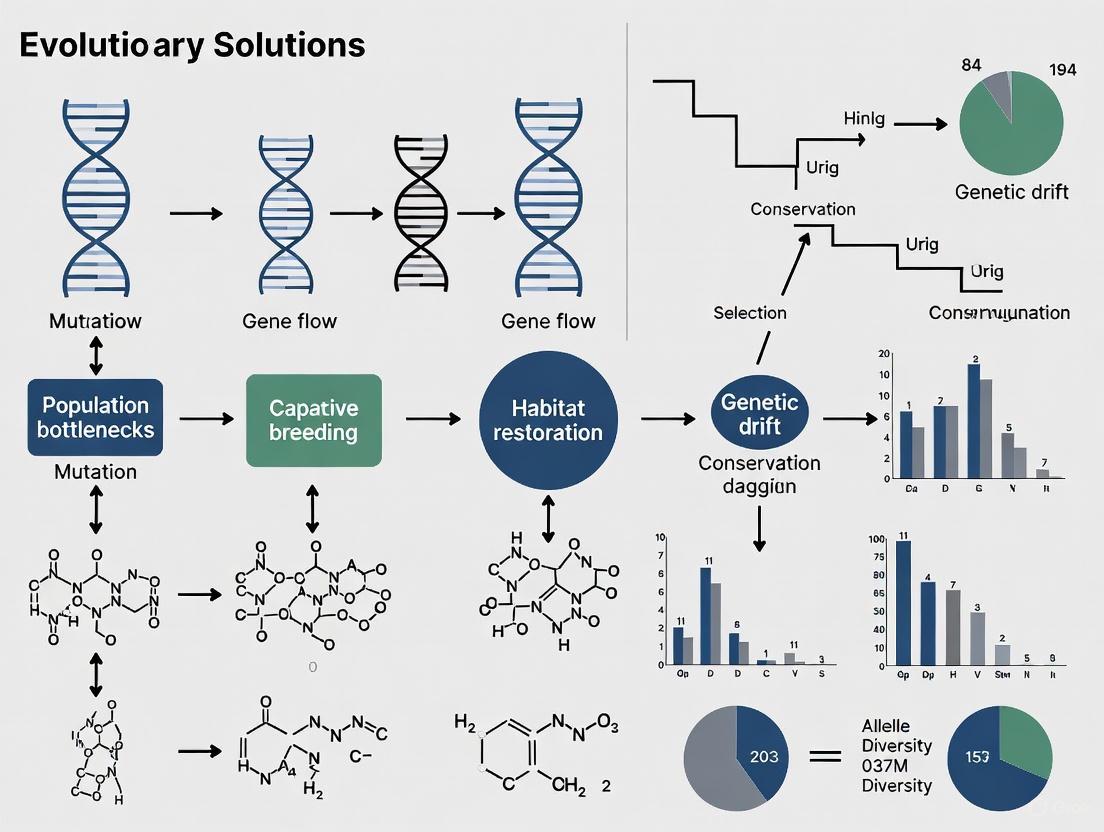

Evolutionary Solutions in Conservation Genetics: From Genomic Tools to Drug Target Discovery

This article synthesizes the latest advancements in evolutionary genetics and their critical applications in conservation science and biomedicine.

Evolutionary Solutions in Conservation Genetics: From Genomic Tools to Drug Target Discovery

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advancements in evolutionary genetics and their critical applications in conservation science and biomedicine. It explores the foundational principles linking genetic diversity to population viability, detailing methodological breakthroughs in genomic sequencing, genetic rescue, and gene editing. The content addresses key challenges in implementation, including technical limitations and ethical considerations, while validating approaches through comparative case studies like the Florida panther and pink pigeon. For researchers and drug development professionals, it highlights the crucial intersection between conserving adaptive potential in endangered species and understanding evolutionary constraints on human drug targets, offering a forward-looking perspective on how conservation genetics informs biomedical innovation.

The Genetic Basis of Conservation: Why Evolutionary Potential Matters

FAQs: Core Concepts and Applications

What is the primary goal of conservation genetics? Conservation genetics aims to preserve biodiversity by applying genetic principles and methodologies to combat species extinction. It uses tools from population genetics, molecular ecology, and evolutionary biology to understand genetic diversity, population structure, and evolutionary processes to inform conservation strategies [1].

How can gene editing specifically help endangered species? Gene editing offers three transformative applications for species conservation: restoring lost genetic variation using historical DNA from museum specimens; facilitating adaptation by introducing beneficial genes from related species; and reducing the load of harmful mutations that accumulate in small populations [2] [3].

What is genomic erosion and why is it problematic? Genomic erosion occurs when populations rebound from a severe crash but remain genetically compromised with diminished genetic variation and high loads of harmful mutations. This reduces resilience to future threats like disease or climate change, as seen in the pink pigeon of Mauritius, which remains at risk of extinction despite population recovery [2] [3].

Which genetic markers are appropriate for population structure studies? According to journal guidelines, papers using only dominant markers like RAPDs or ISSRs are generally not sent for review for population structure studies in sexual species due to interpretation problems. These markers may be acceptable for clonal species but require rigorous assessment of genotype repeatability [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

How can I address low genetic diversity in a study population? When low diversity threatens study validity, consider expanding sampling to include historical specimens from museum collections or biobanks, or utilize gene editing to reintroduce lost variants. The pink pigeon case study demonstrates how genomic erosion can persist even after population recovery, requiring advanced interventions [2].

What are the key considerations for transporting DNA samples internationally? Researchers must comply with CITES restrictions and other international policies governing sample transport. Consultation with relevant authorities is essential, as specific permits may be required for endangered species or samples crossing international borders [5].

How can I validate the functional role of candidate genes in non-model organisms? The gymnosperm study provides a methodology: employ a two-pronged analysis combining evolutionary history with gene expression data, then conduct in-plant experiments to confirm expression patterns. In yew plants, this approach verified genes expressed in unique aril structures important for seed dispersal [6].

Genetic Diversity Monitoring Framework

The following table summarizes the IUCN Guidelines for selecting species and populations for genetic diversity monitoring, providing a structured approach to conservation prioritization [7].

Table: IUCN Guidelines for Genetic Diversity Monitoring Priorities

| Selection Criterion | Application Example | Monitoring Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Species of high conservation concern | Species with documented genomic erosion (e.g., pink pigeon) | Regular assessment of heterozygosity and deleterious mutation load |

| Ecologically pivotal species | Keystone species critical to ecosystem function | Long-term tracking of adaptive genetic variation |

| Species indicative of broader trends | Representatives of threatened habitats | Systematic sampling across populations and time points |

| Species with practical monitoring feasibility | Well-studied species with existing baselines | Repeated genetic analysis integrated with conservation management |

Experimental Protocols in Conservation Genomics

Protocol 1: Population Genomic Analysis Using Next-Generation Sequencing

This protocol outlines the bioinformatics pipeline for analyzing genetic diversity and population structure, as taught in the ConGen2025 course [5].

Materials Required:

- High-quality DNA extracts from multiple individuals across populations

- Reference genome or de novo assembly capabilities

- High-performance computing cluster with adequate storage

- Bioinformatics software stack (e.g., for variant calling, structure analysis)

Methodology:

- Study Design: Determine appropriate sample size and geographic distribution to adequately represent population genetic diversity.

- Sequencing: Utilize next-generation sequencing platforms appropriate for the research question (whole genome, reduced representation, or targeted sequencing).

- Quality Control: Process raw sequencing data through quality control pipelines to remove adapters and low-quality reads.

- Variant Discovery: Map reads to reference genome and identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using standardized variant calling parameters.

- Population Structure Analysis: Employ algorithms like PCA, ADMIXTURE, or similar methods to identify genetic clusters and assign individuals to populations.

- Genetic Diversity Metrics: Calculate heterozygosity, allele frequencies, and inbreeding coefficients across populations.

- Demographic History: Implement coalescent-based methods to infer historical population size changes and divergence times.

Protocol 2: Gene Editing for Genetic Rescue in Endangered Species

This protocol describes the conceptual framework for applying gene editing technologies to restore genetic diversity, based on recent research by van Oosterhout et al. [2] [3].

Materials Required:

- CRISPR-Cas9 or similar gene editing system

- Historical DNA sequences from museum specimens or biobanks

- Cell lines or reproductive tissues from target endangered species

- Surrogate species or assisted reproductive technologies

Methodology:

- Target Identification: Identify specific genetic variants for restoration through comparative genomics of historical and contemporary samples.

- Guide RNA Design: Design specific guide RNAs targeting genomic regions where diversity will be introduced.

- Vector Construction: Assemble editing constructs containing desired genetic variants with appropriate regulatory elements.

- Delivery System: Optimize delivery method (viral vectors, electroporation, microinjection) for the target species' cells or embryos.

- Validation Screening: Genotype edited individuals to confirm precise incorporation of target variants and assess off-target effects.

- Phased Trials: Implement small-scale trials with rigorous monitoring of fitness consequences and ecological impacts.

- Long-term Monitoring: Track edited individuals and their descendants to assess evolutionary outcomes and population-level effects.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Conservation Genetics

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Next-generation sequencing platforms | Generate genome-scale data for diversity assessment | Population genomic analysis of endangered species [5] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Precisely edit genomes to restore genetic diversity | Introducing lost immune gene variants in pink pigeons [2] |

| Museum specimen DNA extracts | Provide historical genetic baseline | Comparing historical and contemporary genetic diversity [2] |

| SNP arrays & genotyping panels | Efficiently screen genetic variation across many individuals | Monitoring genetic diversity in managed populations [8] |

| Bioinformatics pipelines | Analyze large genomic datasets | Variant calling, demographic inference, population structure [5] |

| Transcriptome assemblies | Study gene expression and functional genomics | Identifying genes involved in seed development in gymnosperms [6] |

Workflow Visualizations

Genetic Rescue Implementation Workflow

Conservation Genetic Analysis Pipeline

FAQs: Genetic Diversity in Conservation Genetics

1. What is genetic diversity, and why is it critical for adaptation? Genetic diversity refers to the variety of genes and alleles within a species or population [9]. It is the raw material for adaptation because it provides the heritable variation upon which natural selection acts [10] [11]. When the environment changes, a population with high genetic diversity is more likely to contain individuals with pre-existing advantageous traits—such as heat tolerance or disease resistance—enabling the population to adapt and survive [10] [9]. Populations with low genetic diversity have a smaller "toolkit" and are more vulnerable to extinction, as they may lack the genetic variants necessary to cope with new selective pressures like climate change or novel pathogens [10] [2].

2. What is the difference between standing genetic variation and new mutations? Standing genetic variation is the store of alleles already present in a population, while new mutations are novel genetic changes that occur de novo [12]. Adaptation from standing variation is typically faster because beneficial alleles are immediately available and can start at higher frequencies than new mutations [12]. By contrast, populations may have to wait for a beneficial new mutation to arise. Standing variation alleles are also older and may have been "pre-tested" in past environments, which can increase the probability of parallel evolution [12].

3. How do cis- and trans-regulatory variations contribute to gene expression evolution? Both are sources of regulatory variation, but they differ in mechanism and evolutionary impact [13].

- cis-regulatory variants affect the expression of a gene located on the same chromosome, typically through changes to promoter or enhancer sequences. They tend to have more modular, gene-specific effects [13].

- trans-regulatory variants affect gene expression through diffusible molecules like transcription factors and can be located anywhere in the genome. They often have a larger mutational target size and can regulate multiple genes, making them potentially more pleiotropic [13]. Within species, trans-regulatory variants often contribute more to expression variation. However, as species diverge, the relative contribution of cis-regulatory variants often increases, possibly because they are less likely to have deleterious pleiotropic effects [13].

4. What are the signatures of selection for adaptations from standing variation versus new mutations? The molecular signature of a selective sweep differs based on its source [12]. A "hard sweep" from a single, new beneficial mutation results in a strong reduction of genetic diversity in a large genomic region around the selected allele. In contrast, a "soft sweep" from standing variation may leave a different signature, as the selected allele may be present on multiple genetic backgrounds, preserving more of the surrounding genetic diversity and making the footprint of selection harder to detect [12].

5. How can genome engineering help conserve genetic diversity? For endangered species with severely depleted genetic diversity, traditional conservation may not be enough. Genome engineering offers potential solutions [2]:

- Restoring Lost Variation: Retrieving lost alleles from historical DNA (e.g., from museum specimens) and reintroducing them into the gene pool.

- Facilitated Adaptation: Introducing specific, beneficial genes (e.g., for disease resistance or climate tolerance) from closely related, better-adapted species.

- Reducing Harmful Mutations: Using targeted gene editing to replace fixed, deleterious mutations with healthy variants, potentially improving population health and fitness [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Adaptive Potential in a Conservation Population

1. Identify the Problem A managed population (e.g., in a captive breeding program or a small, isolated wild population) shows signs of low adaptive potential: poor fitness in response to a new disease, rapid environmental shift, or consistent evidence of inbreeding depression [9].

2. List All Possible Explanations

- Small Population Size: Leading to the loss of genetic diversity through genetic drift and inbreeding [10] [9].

- Genetic Bottleneck: A past severe reduction in population size has eroded allelic diversity [10] [2].

- Fragmentation and Isolation: Preventing gene flow, which would otherwise introduce new alleles [10].

- High Genetic Load: An accumulation of deleterious mutations that have become fixed by chance in a small population [2].

3. Collect the Data & 4. Eliminate Explanations Follow this experimental and analytical workflow to diagnose the cause.

5. Check with Experimentation & 6. Identify the Cause Based on the diagnosis from the workflow above, confirm the cause with targeted experiments or deeper analysis.

- For Low Standing Variation, analyze the number of alleles per locus (allelic richness) and expected heterozygosity. Compare to a historical or healthier population [14] [11].

- For High Genetic Load, use genomic data to estimate the number and frequency of deleterious homozygous genotypes [2].

- For Isolation, use landscape genetics approaches to correlate genetic differentiation with geographic barriers [10].

Problem: Differentiating cis- and trans-Regulatory Contributions to an Adaptive Trait

1. Identify the Problem You have identified a gene with expression levels correlated with an adaptive trait (e.g., heat tolerance), but you need to determine whether its expression is controlled by cis- or trans-regulatory variation to understand its evolutionary potential [13].

2. List All Possible Explanations

- Variation is primarily due to cis-regulatory changes.

- Variation is primarily due to trans-regulatory changes.

- Variation is due to a combination of both.

3. Collect the Data & 4. Eliminate Explanations The gold-standard experiment for partitioning this variation is an allele-specific expression (ASE) assay in F1 hybrids [13]. The workflow below outlines the core methodology.

Experimental Protocol: Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) in F1 Hybrids

- Cross Parental Lines: Cross two divergent parental populations (P1 and P2) that differ in the trait and expression of your target gene to generate F1 hybrids.

- RNA Sequencing: Sequence the transcriptomes (RNA-Seq) of the parental lines and the F1 hybrids. High-depth sequencing is critical.

- Map RNA-Seq Reads: Map the sequencing reads to a reference genome. It is crucial to identify SNPs that distinguish the P1 and P2 alleles within the coding sequence of your target gene.

- Quantify Allelic Expression: In the F1 hybrid data, count the number of reads that map to each parental allele (P1 and P2) for the target gene.

- Statistical Analysis: Test for a deviation from a 1:1 ratio of parental alleles in the F1 hybrid's mRNA. A significant deviation indicates cis-regulatory variation. Compare the relative expression of P1 to P2 in the parent vs. the F1 to infer trans-effects [13].

5. Check with Experimentation & 6. Identify the Cause Interpret your ASE results using the following decision matrix:

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Diversity Metrics and Their Implications for Adaptation

This table summarizes quantitative measures used to assess genetic diversity and their relevance to a population's adaptive potential [14] [11].

| Metric | Description | Measurement Method | Interpretation for Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Heterozygosity (He) | The probability that two randomly chosen alleles in a population are different. | Calculated from genotype frequencies derived from SNP arrays or sequencing data. | High He indicates greater diversity for short-term adaptation and is correlated with quantitative genetic variance [14]. |

| Allelic Richness (AR) | The average number of alleles per locus, often rarefied to account for sample size. | Direct count from genetic data (e.g., the number of different alleles at a microsatellite locus or SNP). | A better predictor of long-term adaptation potential, as it reflects the reservoir of variation available for future selection [14]. |

| Inbreeding Coefficient (F) | Measures the reduction in heterozygosity due to non-random mating. | Derived from deviations from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium expectations. | High F indicates inbreeding, which can reduce adaptive potential by increasing the expression of deleterious recessive alleles (inbreeding depression) [9]. |

| Fixation Index (FST) | Measures genetic differentiation between subpopulations. | Computed from variance in allele frequencies among subpopulations. | High FST suggests limited gene flow and independent evolution. Allelic differentiation metrics (e.g., AST) may be more relevant for long-term adaptation between populations [14]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Conservation Genomics

This table details essential materials and tools for conducting research in conservation and evolutionary genetics.

| Item | Function/Description | Application in Conservation Genetics |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Sequencing Kits | Provide all reagents for preparing sequencing libraries from high-quality or degraded DNA (e.g., from museum specimens). | Used for comprehensive genotyping, detecting deleterious mutations, and estimating genome-wide diversity and inbreeding [2]. |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep Kits | Reagents for converting extracted RNA into sequencing libraries to profile gene expression. | Used in allele-specific expression (ASE) assays to partition cis- and trans-regulatory variation in hybrids or for studying the genetic basis of adaptive traits [13]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Genome editing tools comprising a Cas nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA) for targeted DNA modification. | Experimental tool for facilitated adaptation (introducing beneficial alleles) or for reducing genetic load by correcting deleterious mutations in conservation populations [2]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase & PCR Reagents | Enzymes and master mixes for amplifying specific DNA regions via the polymerase chain reaction. | Fundamental for genotyping specific loci (e.g., microsatellites), sex determination, and preparing samples for high-throughput sequencing. |

| Bioinformatics Software (e.g., ANGSD, PLINK, VCFtools) | Computational tools for analyzing next-generation sequencing data, estimating population genetics parameters, and performing association studies. | Essential for calculating diversity metrics (He, FST), identifying regions under selection (selective sweeps), and managing genomic datasets [14] [12]. |

Conceptual Foundations & FAQs

What is inbreeding in a conservation genetics context?

Inbreeding broadly refers to the mating between individuals that share a common ancestor. In small populations, mating with relatives becomes more probable, which can lead to inbreeding depression—the reduced fitness of offspring. This is a primary genetic factor driving the decline and extinction of small populations in conservation biology [15]. The term is used in several distinct ways, which can create confusion:

- Inbreeding as non-random mating: Quantified by the FIS coefficient, it measures deviations from Hardy-Weinberg expectations within a population.

- Inbreeding due to population subdivision: Arises when a population is divided into smaller demes, making individuals within a deme more genetically similar. This is captured by F-statistics like FST.

- Individual inbreeding: Estimates the proportion of an individual's genome that is identical by descent (IBD) [15].

How does genetic drift threaten small populations?

Genetic drift is the chance fluctuation of allele frequencies from one generation to the next. Its power is inversely related to population size, making it a potent force in small populations. It leads to the irreversible loss of genetic variation, reducing the raw material necessary for future adaptation to environmental change [15] [16]. The effective population size (Ne), which is almost always smaller than the census size, determines the strength of genetic drift. A small Ne means faster loss of diversity and an increased risk of fixation of deleterious alleles [17].

What is mutation accumulation and how does it affect small populations?

Mutation accumulation (MA) refers to the process by which deleterious mutations, which are not efficiently removed by natural selection, build up in a population over generations [18]. In small populations, the effectiveness of purifying selection is reduced, allowing mildly deleterious mutations to persist and accumulate through a process known as Muller's ratchet [19] [18]. This leads to a gradual increase in genetic load, which can compromise population fitness and viability, especially when combined with the effects of inbreeding and drift [19].

Can populations be "purged" of inbreeding depression?

In some cases, yes. Purging is the process by which inbreeding depression is reduced because sustained inbreeding exposes recessive deleterious mutations to selection, allowing them to be removed from the population [19]. This purging mainly involves lethals or detrimentals of large effect [19]. However, fitness can still decrease with inbreeding due to the increased homozygosity and fixation of mildly deleterious mutants, which are harder for selection to remove in small populations [19]. Some populations like the vaquita or Island foxes persist at high inbreeding levels, likely due to a complex history of selection and demography [15].

How can we measure inbreeding and genetic drift in wild populations?

Quantifying these threats is a key objective. The following table summarizes common metrics [15] [16]:

| Metric | Description | Application & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Pedigree Inbreeding (FPED) | Estimates the probability of IBD based on a known pedigree. | Requires detailed multigenerational data; limited by depth and completeness of pedigree. |

| Genomic Inbreeding (FROH) | Measures the proportion of the genome in Runs of Homozygosity (ROH). | Identifies tracts of recent shared ancestry; longer ROHs indicate recent inbreeding and are more strongly associated with fitness declines. |

| Effective Population Size (Ne) | The size of an idealized population that would experience the same genetic drift. | A crucial parameter for conservation; small Ne indicates high drift and rapid diversity loss. Can be estimated from genetic data. |

| Genetic Load | The cumulative burden of deleterious mutations in a genome. | Can be approximated by summing predicted harmful effects of deleterious mutations; challenging to estimate in natural populations. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Assessing Inbreeding Depression with Genomic Data

This protocol outlines a modern approach to correlate genomic inbreeding with fitness-related traits.

- Sample Collection & DNA Sequencing: Collect tissue or blood samples from a study population. Extract DNA and perform whole-genome sequencing or genotype using a high-density SNP array.

- Genotype Calling & Quality Control: Use bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., GATK, PLINK) to call genetic variants. Apply strict filters for call rate, minor allele frequency, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

- Calculate Genomic Inbreeding Coefficients:

- FROH: Identify ROHs across the genome. FROH is calculated as the total length of all ROHs in an individual divided by the total length of the genome assayed [15].

- FUNI: Based on the correlation between uniting gametes, it compares observed homozygosity to expected homozygosity under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [15].

- Estimate Genetic Load (Optional): Use genomic annotations to identify putatively deleterious mutations (e.g., those in conserved elements or that disrupt coding sequences). Sum these across an individual's genome to approximate genetic load [15].

- Collect Fitness Data: In a coordinated study, gather empirical fitness data such as juvenile survival, lifetime reproductive success, annual breeding success, or per capita population growth rate [15].

- Statistical Analysis: Use a linear or mixed model to test for a correlation between the genomic inbreeding coefficient (FROH) and the fitness metric, while accounting for confounding factors like age, sex, and environmental variation [15] [20].

Protocol 2: Monitoring Genetic and Demographic Parameters

This integrated approach, as applied to the San Francisco gartersnake, combines genetic and field methods to inform conservation [16].

- Field Surveys & Capture-Mark-Recapture (CMR): Conduct systematic surveys of the target population across multiple seasons/years. Captured individuals are marked (e.g., PIT tags, scale clips) and released.

- Sample Collection: Take a non-invasive tissue sample (e.g., blood, buccal swab, tail clip) from each captured individual for genetic analysis.

- Demographic Analysis: Use CMR data in models (e.g., in program MARK) to estimate key demographic parameters: population abundance (Na), survival probabilities, and recruitment rates [16].

- Genetic Sequencing & SNP Discovery: Extract DNA and use a genome-wide technique like ddRADseq to discover and genotype thousands of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) across all sampled individuals [16].

- Genetic Data Analysis:

- Population Structure: Use algorithms like PCA or ADMIXTURE to visualize and quantify genetic clustering.

- Genetic Diversity: Calculate observed and expected heterozygosity, allelic richness, etc.

- Effective Population Size (Ne): Estimate contemporary Ne using genetic data and methods based on linkage disequilibrium [16].

- Data Integration: Compare estimates of Ne and Na (Ne/N ratio) to understand demographic influences on genetic drift. Use temporal genetic data to examine changes in genetic differentiation and diversity over time [16].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Inbreeding Depression on Fitness-Related Traits

Table summarizing empirical evidence of inbreeding depression across species.

| Species / System | Trait Measured | Impact of Inbreeding | Key Finding / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy Cattle [20] | Milk Yield | Significant inbreeding depression | Inbreeding effects were significantly enriched in promoter, UTR, and GERP constrained genomic regions (Enrichment Ratios: 20.1, 58.0, 35.9). |

| Dairy Cattle [20] | Protein Yield | Significant inbreeding depression | Similar enrichment in functional genomic regions (Enrichment Ratios: 15.3, 46.4, 32.7). |

| Dairy Cattle [20] | Fat Yield | Significant inbreeding depression | Enrichment of inbreeding effects in UTR and GERP regions (Enrichment Ratios: 40.2, 28.7). |

| Wild Populations [15] | Various (Survival, Reproduction) | Generally reduced | Inbreeding depression is consistently shown to reduce offspring survival and reproductive success, though linking it directly in wild populations is complex. |

Table 2: Genetic and Demographic Parameters in an Endangered Snake

Data from a combined study on the San Francisco gartersnake (Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia) [16].

| Population / Site | Regional Cluster | Effective Size (Ne) | Population Abundance (Na) | Genetic Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacifica | Northern | Low (≤100) | Low (≤100) | Decreased genetic diversity over time. |

| Skyline | Northern | Low (≤100) | Low (≤100) | Information from source. |

| Crystal Springs | Northern | Low (≤100) | Low (≤100) | Information from source. |

| San Bruno | Northern | Low (≤100) | Low (≤100) | Information from source. |

| Mindego | Southern | Variable | Variable | Information from source. |

| Other Southern Sites | Southern | Generally higher than northern | Generally higher than northern | Northern and southern clusters show moderate genetic structure. |

Threat Interactions and Conservation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected threats small populations face and the core conservation genetics workflow used to diagnose and mitigate them.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Conservation Genetics |

|---|---|

| High-Density SNP Arrays | Genotyping platforms for simultaneously assaying hundreds of thousands to millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms across the genome, used for estimating inbreeding (FROH), Ne, and population structure [16]. |

| ddRADseq (double-digest RADseq) | A reduced-representation genome sequencing method for discovering and genotyping thousands of SNPs across many individuals without a reference genome, ideal for non-model organisms [16]. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Provides complete genomic data, enabling the most precise estimation of ROH, direct identification of deleterious mutations, and comprehensive assessment of genetic load [15] [20]. |

| PCR-based Markers (e.g., Microsatellites) | Traditional but still useful multi-allelic codominant markers for studies of parentage, relatedness, and population genetics when budget is a constraint. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines (e.g., GATK, PLINK) | Software suites for processing raw sequencing data, performing quality control, calling genetic variants, and conducting basic population genetic analyses [16]. |

| Program MARK / Related Software | Software for analyzing capture-mark-recapture data to estimate vital demographic parameters like population abundance (Na) and survival [16]. |

FAQs: Understanding Genomic Erosion

Q1: What is genomic erosion and why is it a critical concern for endangered species? Genomic erosion refers to the gradual loss of genetic health in a population following demographic decline. It encompasses several key processes: the loss of genome-wide genetic diversity, increased inbreeding (often measured by runs of homozygosity), and the accumulation of harmful genetic mutations (genetic load) [21] [22]. These factors collectively reduce a population's fitness and its potential to adapt to changing environments, creating a negative feedback loop known as the "extinction vortex" [21] [22]. This is critical because even after population numbers crash, genetic decline can continue, threatening long-term species survival even if conservation actions stabilize demographic numbers [23] [24].

Q2: We have documented a severe population crash in our study species, yet standard genetic diversity metrics appear relatively stable. Is this possible? Yes, this phenomenon, known as a time lag or genetic drift debt, is a key challenge in conservation genomics [23] [24]. A population's genetic diversity does not disappear instantly when its numbers drop. The regent honeyeater, for example, experienced a >99% population decline over 100 years, yet modern individuals showed only a 9% reduction in genome-wide heterozygosity compared to historical specimens [23] [24]. This lag means that populations can appear genetically healthy by traditional metrics while already being on a trajectory toward future genomic erosion, obscuring the true extinction risk [23] [25].

Q3: What are the most informative metrics to quantify genomic erosion, beyond simple heterozygosity? A comprehensive assessment of genomic erosion should move beyond overall heterozygosity to include a suite of complementary metrics, which are best interpreted by comparing modern data to pre-decline historical baselines [21] [25] [22].

- Runs of Homozygosity (ROH): Long stretches of homozygous DNA that signal recent inbreeding [21] [22].

- Genetic Load: The accumulation and potential expression of deleterious, harmful mutations in the genome [21] [26].

- Effective Population Size (Ne): An estimate of the number of breeding individuals, which directly influences the rate of genetic drift [23] [27].

- Inbreeding Coefficients (F): Quantifies the probability that two alleles are identical by descent [26].

Q4: What is the minimum recommended genome-wide sequencing coverage for reliable genomic erosion analysis? For statistical power sufficient to confidently call heterozygous sites, an average genome-wide depth of coverage of at least 6X per sample is recommended [25]. However, for more robust analyses, including the assessment of genetic load, higher coverage (e.g., 10X-20X) is advisable. For historical or ancient DNA, which is highly fragmented, dedicated processing pipelines and specialized mapping parameters are required to make data comparable to modern samples [23] [25].

Troubleshooting Experimental Guides

Issue 1: Discrepancy Between Population Census Size and Genetic Health Indicators

Problem: A species with a known recent population bottleneck does not show the expected signals of low genetic diversity or high inbreeding in initial genetic screens.

Solution:

- Investigate Time-Lag Effects: Employ forward-in-time genomic simulations to model how genetic diversity is predicted to change following the documented bottleneck. This can reveal hidden future risks [23] [24].

- Establish a Historical Baseline: Sequence DNA from historical museum specimens to quantify the pre-decline genetic state. This allows for direct measurement of change (ΔEBVs) rather than a single-point assessment [23] [25] [26].

- Analyze Leading Indicators: Look beyond overall heterozygosity. Calculate runs of homozygosity (ROH) to detect recent inbreeding even when genome-wide diversity is still high, and model the genetic load to assess the burden of deleterious mutations [21] [22].

Issue 2: Processing and Integrating Data from Historical/Degraded Samples

Problem: DNA from museum specimens (e.g., toe pads, skins) is fragmented, contaminated, and exhibits post-mortem damage, making it difficult to combine with modern high-quality sequences for analysis.

Solution: Implement a dedicated bioinformatics pipeline, such as GenErode, designed for this exact purpose [25].

Table: Key Steps for Processing Historical and Modern DNA Data

| Step | Modern Samples | Historical/Degraded Samples |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Standard kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit) [23] | Ultra-clean lab facilities; protocols optimized for short fragments, often with additional bleaching washes [23] [26] |

| Library Preparation | Standard protocols for WGS | Specific protocols for ancient/historical DNA (e.g., BEST protocol); use of UDG treatment to reduce damage-derived errors [23] [25] |

| Sequencing | Standard PE-150 on platforms like DNBSEQ-G400 | Often higher depth to compensate for low endogenous DNA; may use PE-100 [23] |

| Read Trimming & Mapping | Adapter/quality trimming with fastp; mapping with BWA mem [25] | Adapter/quality trimming with read merging for short fragments; mapping with BWA aln with parameters for aDNA (e.g., -l 16500 -n 0.01 -o 2) [23] [25] |

| Duplicate Removal | Mark duplicates using Picard MarkDuplicates [25] | Remove duplicates using both start and end mapping coordinates (custom scripts) to account for fragmentation [25] |

| Genotype Calling | Standard variant callers | Use genotype likelihood-based approaches in tools like ANGSD to account for low coverage and DNA damage [23] |

Temporal Genomics Data Integration Workflow

Issue 3: Weak Correlation Between Conservation Status and Genomic Erosion Metrics

Problem: When analyzing multiple species, there is no clear correlation between their IUCN Red List status and standard metrics of genetic diversity or inbreeding.

Solution:

- Focus on Intraspecific Temporal Comparisons: Genomic erosion is most meaningful when measured as change within a species over time, not by comparing absolute diversity values across different species [27]. A 10% loss of diversity in one species may be more critical than a naturally lower level of diversity in another.

- Integrate Ecological and Genetic Models: Combine Species Distribution Models (SDMs) that project habitat suitability with genomic simulations. This reveals how future environmental degradation might interact with ongoing, but lagging, genetic erosion [23].

- Consider Life History: Long-lived, highly mobile species with large historical population sizes are more prone to significant time lags, which can decouple their current genetic status from their demographic reality [23].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Whole-Genome Resequencing for Temporal Genomics

Objective: To generate comparable whole-genome data from both modern and historical specimens to directly quantify genomic erosion.

Key Steps:

- Sample Selection: Select modern (e.g., blood, tissue) and historical (e.g., museum toe pads, skins) samples spanning the known geographic range and temporal window of interest [23] [26].

- DNA Extraction & Library Prep:

- Modern Samples: Use standard kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy). Prepare libraries with standard protocols for 150bp paired-end sequencing [23].

- Historical Samples: Perform extraction in a dedicated ancient DNA clean lab. Use specialized library prep protocols (e.g., BEST protocol) with BGISEQ-specific adapters. Include steps to minimize contamination [23] [26].

- Sequencing: Sequence modern samples to a target coverage of >10X and historical samples as deeply as possible (often >4X average, but highly variable) on an appropriate platform (e.g., DNBSEQ-G400) [23].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Use a standardized pipeline like GenErode [25]:

- Mapping: Map reads to a high-quality reference genome. Mask repetitive regions.

- Variant Calling: For consistent calling across data types, use genotype likelihood-based approaches (e.g., ANGSD) with strict filters [-rmTrans 1, -uniqueOnly 1, -minMapQ 20, -minQ 20] [23].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Genomic Erosion Indices

Objective: To calculate a standardized set of metrics that define genomic erosion from whole-genome resequencing data.

Key Steps:

- Genetic Diversity (π, Heterozygosity): Calculate genome-wide nucleotide diversity (π) and individual heterozygosity from the called variants. A significant decline in modern vs. historical samples indicates erosion [23] [26].

- Runs of Homozygosity (ROH): Use software like

PLINKorNGSRelateto identify ROH. An increase in the number and total length of ROH in modern samples indicates elevated inbreeding [21] [22]. - Genetic Load Estimation:

- Effective Population Size (Ne) Reconstruction: Use methods like

StairwayPlotto infer historical Ne trajectories from the Site Frequency Spectrum, andGONEorNeEstimatorfor recent Ne estimates [23].

Table: Quantitative Case Studies of Genomic Erosion

| Species | Conservation Status | Documented Population Decline | Measured Genetic Change | Key Genomic Erosion Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regent Honeyeater [23] [24] | Critically Endangered | >99% over 100 years (to ~250 birds) | -9% genome-wide heterozygosity | Time-lag effect: Drastic demographic collapse not yet fully reflected in genetic diversity, but simulations predict future erosion. |

| Southern White Rhinoceros [26] | Near Threatened | ~1,000,000 to 200 (now recovered to ~18,000) | -36% genome-wide heterozygosity; +39% inbreeding coefficient | Demonstrated significant genomic erosion despite successful demographic recovery. |

| Northern White Rhinoceros [26] | Functionally Extinct | ~2000 to 2 | -10% genome-wide heterozygosity; +11% inbreeding coefficient | Quantified erosion in a nearly extinct subspecies. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Tools for Genomic Erosion Research

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Historical Specimens | Provides pre-decline genetic baseline for direct comparison. | Museum collections (skin, toe pads, bones); critical for calculating ΔEBVs [23] [24]. |

| UDG Treatment | Enzymatically removes common post-mortem DNA damage (cytosine deamination), reducing errors in historical data. | An optional step in library prep; reduces errors but also shortens molecules [25]. |

| Reference Genome | Essential scaffold for read mapping and variant calling. | Use a chromosome-level assembly from a closely related species to reduce reference bias [23]. |

| GenErode Pipeline | A standardized, reproducible Snakemake pipeline for processing modern and historical WGS data in parallel. | Ensures comparability of results; uses Conda/Singularity for reproducibility [25]. |

| ANGSD Software | Analyzes next-generation sequencing data without calling genotypes, ideal for low-coverage historical data. | Uses genotype likelihoods to avoid biases from low-coverage samples [23]. |

| Forward-in-Time Simulations (e.g., SLiM) | Individual-based simulations to project future genetic diversity and load based on current data and demographic models. | Used to reveal hidden risks and "genetic drift debt" [23] [24]. |

The Extinction Vortex Mechanism

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Effective Population Size (Ne) and why is it fundamentally different from a simple census count?

A1: Effective population size (Ne) is defined as the size of an idealized population that would experience the same rate of genetic drift or inbreeding as the real population under study [28] [29]. An idealized population assumes random mating, equal sex ratios, and constant population size. In contrast, the census size (Nc) is simply the total number of individuals in a population. Ne is the evolutionary analog to Nc; while ecological consequences depend on Nc, evolutionary consequences like the rate of loss of genetic diversity depend on Ne [29]. For conservation, Ne is a more valuable metric because it directly correlates with a population's long-term survival capacity and its ability to maintain genetic variation [30].

Q2: My Ne estimate is much lower than the census count. Is this an error?

A2: No, this is a common and expected finding. In natural populations, the effective population size is almost always smaller than the census size [28] [31]. A survey of 102 wildlife species found that the ratio of Ne to Nc (Ne/N) averages about 0.34, and can be as low as 0.10-0.11 when accounting for population fluctuations and unequal family size [28]. This discrepancy arises from real-world complexities that violate the ideal population model, such as unequal sex ratios, variance in reproductive success among individuals, and fluctuations in population size over time [28] [32].

Q3: What is the difference between "contemporary" and "historical" Ne, and which should I use for conservation monitoring?

A3: The distinction is temporal and is critical for interpreting your results.

- Contemporary Ne reflects the effective size of the current generation or the last few generations. It indicates the rate of genetic drift expected in the immediate future, making it highly relevant for ongoing population monitoring and conservation management [30].

- Historical Ne is a long-term average over many generations, sometimes hundreds or thousands. It explains the current genetic makeup of a population but is difficult to link to recent management actions or environmental changes [30]. For conservation purposes, particularly for reporting under frameworks like the UN's Convention on Biological Diversity, contemporary Ne is often the more actionable metric [30].

Q4: I've sampled a seemingly continuous population. Could my sampling strategy itself affect the Ne estimate?

A4: Yes, sampling design is a critical and often overlooked factor. The spatial scale of your sampling relative to the biological population directly influences what your Ne estimate represents [30]. If you sample from a portion of a larger, continuous population that exhibits isolation-by-distance, you might be estimating the Ne of a local subpopulation rather than the entire metapopulation. It is essential to define the spatial scale of your population of interest before sampling and to interpret your Ne estimate within that context to avoid misleading conservation decisions [30].

Troubleshooting Guide for Ne Estimation

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when estimating Ne from genetic data.

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Highly variable Ne estimates across different genes or genomic regions. | Selection at linked sites (background selection, genetic hitchhiking). Regions of low recombination have a lower local Ne [28] [31]. | This is an expected biological signal. Use many neutral, unlinked markers spread across the genome. Avoid regions under known strong selection for Ne estimation [28]. |

| Ne estimate is implausibly low or high. | Violation of method assumptions (e.g., population is not isolated, has unsampled sub-structure, or is not at mutation-drift equilibrium) [30]. | Test for and report population structure (e.g., with FST). Use estimation methods designed for connected populations [30]. Clearly state the assumptions of your chosen method. |

| Inconsistent estimates when using different statistical methods (e.g., LD-based vs. temporal method). | Different methods measure different types of Ne (e.g., variance, inbreeding, coalescent Ne) over different timescales [30]. | This is common in real-world populations. Do not expect different methods to yield identical results. Choose the method that best aligns with your biological question (e.g., LD-based for contemporary Ne) [33]. |

| Uncertainty about optimal sample size. | Small sample sizes can lead to imprecise estimates, while very large samples may be cost-prohibitive for conservation projects. | A sample size of 50 individuals has been shown to be a reasonable compromise for obtaining an unbiased approximation of the true Ne in livestock populations, and may serve as a useful rule of thumb [33]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Estimating Contemporary Ne using Linkage Disequilibrium (LD)

Principle: This method estimates contemporary Ne from the observed pattern of linkage disequilibrium (the non-random association of alleles between loci) in a single population sample. LD accumulates as populations get smaller due to genetic drift [33].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Collection & DNA Extraction: Collect tissue or blood samples from a representative set of individuals from the target population. The recommended sample size is at least 50 individuals [33]. Extract high-quality genomic DNA.

- Genotyping: Genotype all individuals using a high-density SNP array or through whole-genome sequencing to obtain a genome-wide set of neutral genetic markers [33].

- Data Quality Control (QC): Use software like PLINK for QC.

- Filter individuals and markers for high call rates (e.g., >95%).

- Remove markers with low minor allele frequency (MAF) (e.g., <0.01-0.05) to avoid bias.

- Prune markers in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) to ensure they are unlinked, using a threshold like r2 < 0.5 [33].

- Ne Estimation: Input the quality-controlled genotype data into specialized software such as NeEstimator v.2, which implements the LD method [33]. The software will calculate Ne based on the formula linking the expected LD (E(r²)) to Ne:

E(r²) ≈ 1 / (1 + 4Nec), wherecis the genetic distance in Morgans [31]. - Interpretation: The output is an estimate of contemporary Ne (typically for the last ~2-3 generations). Report the estimate alongside the 95% confidence intervals, which the software usually provides.

Workflow Diagram: From Sampling to Ne Estimation

The diagram below visualizes the core workflow for estimating contemporary effective population size, highlighting key decision points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and their functions in Ne estimation studies.

| Item / Reagent | Function in Ne Estimation |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5) | Used for preparing sequencing libraries. Provides high accuracy to minimize sequence errors during whole-genome sequencing, which could bias downstream analyses [34]. |

| SNP Genotyping Array (e.g., Goat SNP50K) | A cost-effective method for generating genome-wide genotype data from many individuals. Provides the neutral marker set required for LD-based Ne estimation [33]. |

| DNA Cleanup Kits (e.g., Monarch) | For purifying DNA samples post-extraction or post-PCR. Removes inhibitors that can interfere with genotyping or sequencing reactions, ensuring high-quality data [34]. |

| PLINK Software | A core bioinformatics tool for processing and quality-controlling genotype data before Ne estimation. Used for filtering samples/markers, pruning LD, and calculating basic statistics [33]. |

| NeEstimator v.2 Software | A widely used, stand-alone software that implements several methods for estimating Ne, including the linkage disequilibrium method, making it accessible for conservation practitioners [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is an Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) and why is it important for conservation? An Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) is a population of organisms considered distinct for conservation purposes [35]. It represents a fundamental concept in conservation biology that helps prioritize populations for protection based on their unique evolutionary heritage and ecological roles. ESUs are crucial because they preserve genetic diversity essential for long-term species survival and adaptability, maintain evolutionary potential, and guide conservation priorities by highlighting irreplaceable unique evolutionary lineages [35] [36].

Q2: What are the primary criteria for designating an ESU? The designation typically relies on two key criteria [35]:

- Reproductive Isolation: The population must be substantially reproductively isolated from other conspecific populations, evidenced by genetic data showing significant differentiation at neutral markers or through current geographic separation [35] [36].

- Evolutionary Legacy: The population must represent an important component in the evolutionary legacy of the species, indicated by unique adaptations to local environments, distinctive ecological roles, or specialized behaviors not found in other populations [35] [36].

Q3: What are common pitfalls when identifying ESUs using primarily genetic data? Over-reliance on genetic data alone presents several challenges [35] [37]:

- Drift vs. Adaptation: Neutral genetic markers may show differentiation caused primarily by genetic drift in small, fragmented populations rather than adaptive evolutionary change. This can lead to managing populations separately that are not truly adaptively unique, potentially increasing extinction risk [37].

- Arbitrary Thresholds: Genetic differentiation forms a continuum, making clear dichotomous classification (ESU vs. non-ESU) challenging without somewhat arbitrary thresholds [35] [36].

- Overlooked Ecological Adaptation: Gene flow can be sufficient to reduce differentiation at neutral markers while local adaptation persists. For example, Cryan's buckmoth is indistinguishable from relatives at tested genetic markers but has 100% survivorship on its specific host plant, where close relatives all die [36].

Q4: How can researchers integrate ecological and behavioral factors to improve ESU designations? A more robust, holistic approach combines multiple data sources [35] [36] [38]:

- Reciprocal Transplantation Experiments: These tests can reveal genetic differentiation in phenotypic traits and local adaptations even when neutral genetic markers show little differentiation [36].

- Functional Trait Analysis: Assess ecological roles through specific functional traits (e.g., feeding strategies, habitat use) to determine if populations occupy unique ecological niches [38].

- Behavioral Studies: Document distinctive foraging strategies, social structures, or other behaviors that indicate ecological specialization, as seen in different orca populations [35].

Q5: What conservation conflicts can arise when managing multiple ESUs within a species? Designating multiple ESUs creates complex management scenarios [35]:

- Resource Allocation: Limited conservation resources must be divided between distinct ESUs, potentially forcing difficult prioritization decisions.

- Conflicting Management Needs: Different ESUs may require distinct, sometimes conflicting, habitat management strategies, especially when they occupy overlapping or adjacent areas.

- Genetic Diversity Trade-offs: Strictly managing isolated populations to preserve perceived uniqueness can reduce genetic diversity and adaptive potential, potentially increasing extinction risk for the species overall [37]. In such cases, carefully managed gene flow through translocation may be beneficial [37].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge: Determining if genetic uniqueness represents adaptive differentiation or genetic drift. Background: Researchers often encounter populations with significant genetic differentiation but lack evidence whether this represents meaningful adaptive divergence or random drift in small populations [37].

Solution:

- Compare Genetic Diversity vs. Uniqueness: Plot measures of genetic diversity (e.g., expected heterozygosity, allelic richness) against population-specific FST estimates. A strong negative relationship suggests drift is the primary driver of uniqueness [37].

- Conduct Common Garden Experiments: Raise individuals from different populations under controlled conditions to identify genetically-based phenotypic differences indicating local adaptation [36].

- Analyze Functional Traits: Assess traits linked to fitness and ecological function. The FUSE INS framework combines functional uniqueness and specialization with extinction risk to identify populations critical for conserving functional diversity [38].

Expected Outcome: This multi-pronged approach distinguishes populations with historically significant adaptive differences from those whose uniqueness results primarily from recent population fragmentation and drift [37].

Challenge: Integrating functional ecology into conservation prioritization of populations. Background: Traditional ESU designation often overemphasizes neutral genetic markers, potentially overlooking ecologically significant populations [35] [38].

Solution: Implement the Functionally Unique, Specialized, and Endangered (FUSE) framework:

- Quantify Functional Uniqueness: Calculate functional distinctiveness of each population/species in multivariate trait space.

- Assess Functional Specialization: Measure the degree of ecological specialization.

- Combine with Threat Assessment: Integrate functional irreplaceability with population-specific extinction risk, particularly from threats like invasive species [38].

Expected Outcome: Identifies populations that represent large amounts of functional diversity and are at high extinction risk, enabling prioritization of conservation efforts toward ecologically irreplaceable units [38].

Challenge: Managing small, isolated populations with apparent uniqueness but low genetic diversity. Background: Many threatened species exist as small, fragmented populations exhibiting genetic uniqueness but suffering from low genetic diversity and potential inbreeding depression [37].

Solution:

- Evaluate Evolutionary Significance: Determine if uniqueness reflects long-term evolutionary divergence (via mutation) or recent drift by testing if genetic differentiation exceeds expectations under a pure drift model [37].

- Consider Genetic Rescue: If uniqueness is primarily drift-driven and populations show signs of inbreeding depression, consider carefully managed gene flow through translocation from other populations to increase genetic diversity and adaptive potential [37].

- Monitor Adaptive Potential: Track both neutral and adaptive genetic variation following management interventions.

Expected Outcome: Balanced approach that preserves genuinely adaptive differences while addressing genetic constraints that increase extinction risk in small populations [37].

Experimental Protocols for ESU Identification

Protocol 1: Comprehensive ESU Assessment Integrating Genetic and Ecological Data

Purpose: Systematically evaluate populations for ESU designation using complementary genetic and ecological criteria.

Materials:

- Tissue samples for genetic analysis

- Environmental data for sampling locations

- Equipment for morphological/behavioral measurements

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect representative samples from multiple populations, ensuring adequate sample sizes (typically >15 individuals per population) [37].

- Genetic Analysis:

- Genotype individuals using appropriate markers (e.g., microsatellites, SNPs)

- Calculate genetic diversity indices (expected heterozygosity, allelic richness)

- Estimate population differentiation (FST, population-specific FST)

- Test for signatures of selection at candidate loci [37]

- Ecological Assessment:

- Measure relevant environmental variables across populations

- Quantify morphological, physiological, or behavioral traits linked to fitness

- Conduct common garden or reciprocal transplant experiments where feasible [36]

- Data Integration:

- Correlate genetic differentiation with ecological distance

- Test for isolation-by-adaptation patterns

- Assess whether ecological differences exceed neutral genetic expectations

Analysis: Populations exhibiting both significant genetic differentiation and evidence of local adaptation represent strong ESU candidates. Populations showing genetic differentiation primarily driven by drift without ecological differentiation may benefit from genetic rescue rather than strict separate management [37].

Protocol 2: Functional Uniqueness Assessment Using the FUSE INS Framework

Purpose: Identify populations that are both functionally irreplaceable and threatened by invasive species.

Materials:

- Species trait data (morphological, ecological, behavioral)

- Threat assessment data (IUCN Red List categories)

- Geographic distribution data

Procedure:

- Trait Matrix Construction:

- Compile comprehensive functional trait data for all species in the taxonomic group

- Include traits related to resource use, habitat requirements, and ecosystem function

- Functional Space Calculation:

- Build a multidimensional functional space using principal coordinates analysis

- Position all species within this functional space [38]

- Irreplaceability Metrics:

- Calculate functional uniqueness (FUn) as the distance of a species from others in functional space

- Calculate functional specialization (FSp) as the distance of a species from the centroid of functional space [38]

- Threat Integration:

- Determine extinction probability due to invasive species (PINS) based on IUCN assessments

- Compute FUSE INS score: ln(1 + PINS × FSp + PINS × FUn) [38]

Analysis: Populations with high FUSE INS scores represent conservation priorities as they possess unique functional traits and face significant threat from invasive species. This approach helps allocate resources to conserve both taxonomic and functional diversity [38].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ESU Designation Criteria Across Taxonomic Groups

| Species Example | Primary Designation Basis | Key Evidence for Uniqueness | Conservation Management Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific Salmon [35] | Genetic & ecological differentiation | Adaptations to specific river systems | Managed as separate ESUs to preserve unique run timing & reproductive traits |

| Orca Populations [35] | Genetic, behavioral, ecological | Distinct hunting strategies, social structures | Separate management of ecotypes with different dietary specializations |

| Giant Panda [35] | Genetic & ecological differentiation | Local adaptations to different mountain ranges | Separate management of populations with habitat corridors consideration |

| Australian Mammals [37] | Genetic differentiation (microsatellites) | Population-specific FST; often drift-driven | Consideration of genetic rescue instead of strict separate management |

| Cryan's Buckmoth [36] | Ecological adaptation | 100% survivorship on specific host plant | Management recognizing ecological uniqueness despite genetic similarity |

Table 2: Metrics for Assessing Different Components of Conservation Value in Populations

| Metric | What It Measures | Calculation Method | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population-specific FST [37] | Genetic uniqueness of a population | Derived from genetic differentiation indices | High values indicate genetic distinctness; should be correlated with genetic diversity to assess drift effect |

| Functional Uniqueness (FUn) [38] | Rareness of a species' functional traits | Distance from other species in multidimensional functional space | High values indicate species with unique functional roles in ecosystem |

| Functional Specialization (FSp) [38] | Degree of ecological specialization | Distance from centroid of functional space | High values indicate specialized species with narrow ecological niches |

| Area-controlled surplus of species [39] | Deviation from species-area relationship | Residuals from SAR regression | Positive values indicate PAs with more species than expected for their size |

| Rarity-weighted richness [39] | Concentration of rare species in an area | Sum of inverse range sizes of present species | High values indicate areas with many geographically restricted species |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for ESU and Adaptive Uniqueness Studies

| Research Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Microsatellite Markers [37] | Assessment of neutral genetic variation and population structure | Initial screening of genetic diversity and differentiation between populations |

| SNP Chips/Genotyping-by-Sequencing | Genome-wide assessment of genetic variation | Detection of neutral and adaptive genetic differentiation; landscape genomics studies |

| Functional Trait Databases [38] | Compilation of ecological, morphological, behavioral traits | Quantification of functional diversity and uniqueness across populations |

| Common Garden Experiment Materials [36] | Controlled environment growth facilities | Separation of genetic and environmental components of phenotypic variation |

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) Sampling Kits [40] | Non-invasive species detection and monitoring | Population monitoring without direct capture or disturbance |

| IUCN Red List Assessment Data [38] | Standardized extinction risk evaluation | Integration of threat status with genetic and functional diversity metrics |

Workflow Visualization

ESU Designation Decision Workflow

Functional Uniqueness Assessment Workflow

The Conservation Geneticist's Toolkit: From Genomics to Intervention

The field of conservation genetics applies genetic principles to preserve biodiversity, where understanding genetic variation is imperative for populations to adapt to environmental changes [41]. For decades, microsatellite markers were the primary tool for studying this variation. However, the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the field, enabling a transition to single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) [42]. This paradigm shift provides unprecedented resolution for analyzing genome structure, genetic variations, and evolutionary relationships, offering powerful new solutions for evolutionary studies in conservation [42] [41].

Technology Comparison: From Microsatellites to Whole Genomes

Key Genomic Technologies

| Technology | Marker Type | Throughput | Information Content | Primary Applications in Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microsatellites | Short tandem repeats (STRs) | Low | Moderate (10s of loci) | Population structure, kinship, pedigree analysis [43] |

| SNP Genotyping Arrays | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms | Medium | High (100s to 1,000,000s of loci) | Population genomics, phylogenetics, GWAS [43] |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Genome-wide SNPs & structural variants | High | Comprehensive (entire genome) | De novo assembly, variant discovery, structural variant detection [44] [45] |

| Low-Pass WGS | Genome-wide SNPs | Medium | High with imputation | Cost-effective SNP discovery, copy number variant detection [45] |

| Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing | Methylated cytosines | High | Comprehensive methylome | Epigenetic studies, gene regulation [45] |

Sequencing Platform Specifications

| Platform | Sequencing Technology | Read Length | Key Advantages | Common Conservation Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing by Synthesis | Short (36-300 bp) | High accuracy (>99.9%), cost-effective [42] [45] | Resequencing, variant detection (SNPs/Indels), population studies [44] |

| PacBio SMRT | Single-molecule real-time | Long (avg. 10,000-25,000 bp) | Long reads, detects epigenetic modifications | De novo assembly, resolving complex regions, haplotyping [42] [44] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Electrical impedance detection | Long (avg. 10,000-30,000 bp) | Ultra-long reads (>4 Mb), portable | De novo assembly, structural variant detection, field sequencing [42] [44] |

Experimental Protocols for Conservation Genomics

Protocol 1: Developing a Custom SNP Panel for Population Genomics

This protocol, derived from lion conservation genomics, outlines the steps for discovering and validating a custom SNP panel to study population structure and evolutionary lineages [43].

Step 1: Sample Selection and Whole-Genome Sequencing

- Select individuals that represent the geographic range and putative populations of the target species.

- Perform low-coverage (~3-5x) whole-genome sequencing on a representative subset of samples (e.g., n=10) using platforms like Illumina to discover genome-wide variants [43].

Step 2: Variant Discovery and Calling

- Align sequencing reads to a reference genome. If no reference exists, a de novo assembly from long-read data (PacBio/Oxford Nanopore) is required [44].

- Use variant callers like GATK to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome. One study identified >150,000 SNPs in this manner [43].

- Filter SNPs for quality, coverage (e.g., ≥3x), and missing data to create a high-confidence variant set.

Step 3: SNP Panel Design and Validation

- Select a subset of informative SNPs (e.g., 125 autosomal SNPs) that represent major population clusters identified in phylogenetic analyses [43].

- Include additional markers if needed, such as mitochondrial SNPs for matrilineal history.

- Validate the panel by genotyping a large set of samples (e.g., n>200) from across the species' range.

Step 4: Data Analysis and Assignment

- Use genotyping data to assign individuals to major evolutionary clades.

- Analyze population structure, genetic diversity, and admixture to inform conservation plans and translocation strategies [43].

Protocol 2: Whole-Genome Sequencing forDe NovoAssembly and Variant Detection

This protocol provides a framework for applying WGS to non-model organisms where a reference genome may not be available [44] [45].

Step 1: Project Design and Sample Preparation

- Define Goal: Choose between resequencing (if a reference genome exists) or de novo sequencing and assembly (if no reference is available) [44].

- Extract High-Molecular-Weight (HMW) DNA: This is critical for long-read sequencing. Follow best practices for extraction to avoid DNA shearing [44].

- Choose Platform: Select based on project goals. Use Illumina for high-accuracy variant calling. Use PacBio or Oxford Nanopore for de novo assembly of complex genomes or to span large repetitive regions [44].

Step 2: Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Fragment DNA and construct sequencing libraries by adding platform-specific adapters.

- For Illumina, bridge PCR amplifies clusters on a flow cell [42].

- For PacBio, libraries are loaded into SMRT cells containing zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) for real-time sequencing [42].

- Sequence to an appropriate coverage (see Table 3.2.1).

Step 3: Data Analysis, Assembly, and Annotation

- Quality Control: Filter raw data (FASTQ files) to remove low-quality sequences and adapters [44] [45].

- Genome Assembly: For de novo projects, use assemblers to piece reads into contigs and scaffolds. Long reads are invaluable for this step [44].

- Variant Calling: For resequencing projects, align reads to a reference genome to identify SNPs, insertions/deletions (indels), and structural variants [45].

- Genome Annotation: Identify genes, regulatory elements, and other functional features in the assembled genome.

Coverage Recommendations for Whole-Genome Sequencing

| Application | Recommended Coverage (Short-Read) | Recommended Coverage (Long-Read) |

|---|---|---|

| Germline / Frequent Variant Analysis | 20-50x [44] | 20-50x [44] |

| Somatic / Rare Variant Detection | 100-1000x [44] | - |

| De novo Assembly | 100-1000x [44] | 50-100x [44] |

| Large Structural Variant Detection | - | 10x [44] |

| Gap Filling & Scaffolding | - | 10x [44] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

SNP Genotyping Troubleshooting

Q: My SNP assay is not amplifying. What could be the cause? A: Several factors can lead to no amplification:

- Inaccurate DNA Quantitation: Use fluorometric methods for accurate DNA concentration measurement.

- Degraded DNA: Assess DNA integrity. Degraded samples may not amplify.

- PCR Inhibitors: Purify the DNA sample to remove inhibitors.

- Error in Reaction Setup: Verify reagent concentrations and cycling conditions [46].

Q: My allelic discrimination plot shows trailing or diffuse clusters. How can I resolve this? A: Trailing clusters are often due to inconsistent DNA quality or concentration across samples [46]. To fix this:

- Standardize DNA Quality: Use DNA extracted and purified with consistent methods.

- Accurately Quantitate DNA: Ensure uniform concentration across all samples.

- Check for Hidden SNPs: Search databases like dbSNP for secondary polymorphisms under the primer or probe binding sites; redesign the assay if necessary [46].

Q: The genotyping software is not making automatic calls (autocalling) for my data. What should I do? A:

- Use Specialized Software: Try software with improved clustering algorithms, such as TaqMan Genotyper Software, which can call clusters that standard instrument software misses [46].

- Adjust Cycle Number: Depending on the assay, increasing or decreasing the number of PCR cycles may improve cluster separation.

- Manually Review Traces: If supported by your instrument software, collect real-time data and visually inspect the amplification traces [46].

Whole-Genome Sequencing Troubleshooting

Q: What is the difference between WGS and Whole Exome Sequencing (WES)? A:

- WGS sequences the entire genome, including both coding and non-coding regions (e.g., introns, regulatory regions). It provides a comprehensive view, allows identification of pathogenic variants in non-coding regions, and offers better coverage for structural variants [45].

- WES targets only the protein-coding regions of the genome (exons), which constitute about 1-2% of the genome. It is a more cost-effective approach when the primary interest is in coding variants but can miss important non-coding and structural variations [45].

Q: When should I use long-read vs. short-read sequencing? A:

- Choose Short-Read (Illumina) for applications requiring high base-level accuracy and cost-effectiveness, such as variant detection (SNPs, small indels) in population studies or resequencing projects with a reference genome [44].

- Choose Long-Read (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) for applications that benefit from long, continuous sequences, such as de novo genome assembly, resolving complex, repetitive regions, detecting large structural variants, and achieving haplotype-phased genomes [44].

Q: How much coverage do I need for my WGS project? A: Coverage requirements depend on the organism and experimental goal. See Table 3.2.1 for detailed recommendations. As a general guideline:

- For human germline variant detection, 30-50x coverage is standard.

- For de novo assembly of larger genomes, 50-100x with long reads is recommended [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA Extraction Kit | To isolate long, intact DNA strands crucial for long-read sequencing. | Preparing samples for PacBio or Nanopore sequencing to achieve high-quality de novo assemblies [44]. |

| DNA Library Preparation Kit | To fragment DNA and add platform-specific adapters for sequencing. | Constructing Illumina sequencing libraries from gDNA for whole-genome resequencing [45]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | To convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils for epigenetic studies. | Preparing samples for Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) to map DNA methylation [45]. |

| SNP Genotyping Assay | To genotype specific single nucleotide polymorphisms. | Using a validated SNP panel to assign individuals to evolutionary lineages for conservation management [43]. |

| Fragment Analyzer / Bioanalyzer | To assess DNA/RNA integrity and library size distribution. | Performing quality control on extracted gDNA or prepared libraries before sequencing [44]. |

| Qubit Assay / Fluorometer | To accurately quantify nucleic acid concentration. | Quantifying DNA sample concentration prior to library preparation to ensure input requirements are met [44]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Genomic Technology Evolution Workflow

This diagram illustrates the progressive transition and complementary relationship between different genomic technologies used in conservation genetics, from the initial use of microsatellites to the advanced application of long-read whole-genome sequencing.

Conservation Genomics Experimental Pipeline

This workflow outlines the key steps in a conservation genomics project, from sample collection in the field to the application of insights for species conservation management.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Technical Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the primary challenges when working with historical DNA, and how can I mitigate them? Historical DNA from museum specimens or biobanks is often degraded and fragmented. To mitigate this:

- Use specialized extraction kits designed for ancient or degraded DNA to maximize yield.

- Implement ultra-clean laboratory protocols and dedicated pre-PCR spaces to prevent contamination from modern DNA [47].

- Sequence with high depth to account for damage and ensure variant calls are accurate.

FAQ 2: How can I ensure the quality of my genomic data throughout the analysis pipeline? The "Garbage In, Garbage Out" principle is critical. Implement quality control (QC) at every stage [47]:

- Sequencing QC: Use tools like FastQC to monitor metrics like Phred scores (Q30), read length distributions, and GC content.

- Alignment QC: Use tools like SAMtools to assess alignment rates and coverage depth.

- Variant Calling QC: Apply quality filters based on scores from tools like the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) to distinguish true variants from sequencing errors [47].

FAQ 3: Our population has recovered in number but shows signs of inbreeding depression. What genetic rescue options exist? Gene editing offers a transformative solution to restore genetic diversity [2] [48] [49]. Key applications include:

- Restoring Lost Variation: Using historical DNA from museum specimens to reintroduce lost gene variants into the modern population's gene pool.

- Reducing Harmful Mutations: Replacing fixed, deleterious mutations with healthy variants from historical genomes to improve overall health and fertility.

FAQ 4: What are the critical ethical considerations for using gene editing in conservation? Genetic interventions must be pursued with caution and as a complement to traditional conservation like habitat protection [2] [49].