Evolutionary Optimization Algorithms: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review explores evolutionary optimization algorithms (EOAs) and their transformative potential in solving complex, multi-objective problems in drug development and biomedical research.

Evolutionary Optimization Algorithms: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores evolutionary optimization algorithms (EOAs) and their transformative potential in solving complex, multi-objective problems in drug development and biomedical research. We examine the foundational principles of key algorithms including Genetic Algorithms, Particle Swarm Optimization, and Differential Evolution, highlighting their distinct search mechanisms and theoretical underpinnings. The article systematically analyzes methodological adaptations for handling high-dimensional biomedical optimization challenges, from small-molecule design to clinical trial optimization. Practical guidance addresses parameter tuning, computational constraints, and convergence acceleration strategies specifically for resource-intensive biomedical applications. Finally, we establish rigorous validation frameworks using benchmark functions and domain-specific case studies, while exploring emerging paradigms like LLM-EOA hybrid systems that are reshaping computational drug discovery pipelines.

The Biological Blueprint: Understanding Evolutionary Algorithm Fundamentals and Natural Inspirations

Evolutionary computation represents a family of optimization algorithms inspired by the principles of natural selection and genetics. These algorithms simulate the process of natural evolution to solve complex optimization problems that challenge traditional methods. By employing mechanisms such as selection, mutation, and recombination, evolutionary algorithms progressively refine a population of potential solutions over generations, ultimately converging toward optimal or near-optimal solutions. The robustness and versatility of these approaches have led to their successful application across diverse fields including engineering design, financial modeling, drug discovery, and bioinformatics [1] [2].

This article explores the core principles of evolutionary algorithms, from their biological foundations to their implementation as computational optimization tools. Framed within broader research on evolutionary optimization for complex problems, we provide detailed application notes and experimental protocols tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage these powerful algorithms in their work.

Fundamental Biological Principles

Natural Selection and Evolutionary Dynamics

At the heart of evolutionary algorithms lies the concept of natural selection, a process first formally described by Charles Darwin. In nature, organisms compete for scarce resources, with individuals possessing advantageous traits being more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass these traits to offspring [3]. This "survival of the fittest" mechanism gradually improves a population's adaptation to its environment over successive generations.

The computational analog of this process operates on a population of potential solutions to a given problem. Each solution is evaluated according to a fitness function that quantifies its performance. Superior solutions receive higher fitness scores and are preferentially selected to contribute genetic material to subsequent generations, mirroring the selective pressures observed in biological evolution [4] [3].

Genetic Inheritance Mechanisms

Biological evolution depends on genetic mechanisms that enable trait inheritance and variation. In nature, chromosomes composed of genes encode an organism's traits, with sexual reproduction combining genetic material from both parents through recombination [3].

Evolutionary algorithms implement similar concepts through:

- Representation: Potential solutions are encoded as strings (chromosomes) comprising individual elements (genes) [3]

- Crossover: Parent solutions exchange genetic information to produce offspring with combined characteristics [4] [1]

- Mutation: Random alterations to genetic material introduce novel traits not present in the parent population [3]

These mechanisms collectively maintain diversity while exploiting promising solution features, enabling the algorithm to explore complex search spaces effectively.

Algorithmic Framework and Workflow

Core Components of Evolutionary Algorithms

The implementation of evolutionary algorithms involves several key components, each corresponding to elements of biological evolution:

- Population: A set of potential solutions (individuals) representing points in the search space [4] [2]

- Representation: An encoding scheme that defines how solutions are structured as data structures (e.g., binary strings, real-valued vectors, parse trees) [3] [1]

- Fitness Function: A problem-specific evaluation metric that quantifies solution quality [3] [2]

- Selection Mechanism: A strategy for choosing parents based on fitness (e.g., roulette wheel, tournament selection) [3] [1]

- Genetic Operators: Functions that modify solutions, primarily crossover (recombination) and mutation [4] [3]

- Replacement Strategy: A method for determining how offspring replace existing individuals in the population [1]

The Evolutionary Cycle

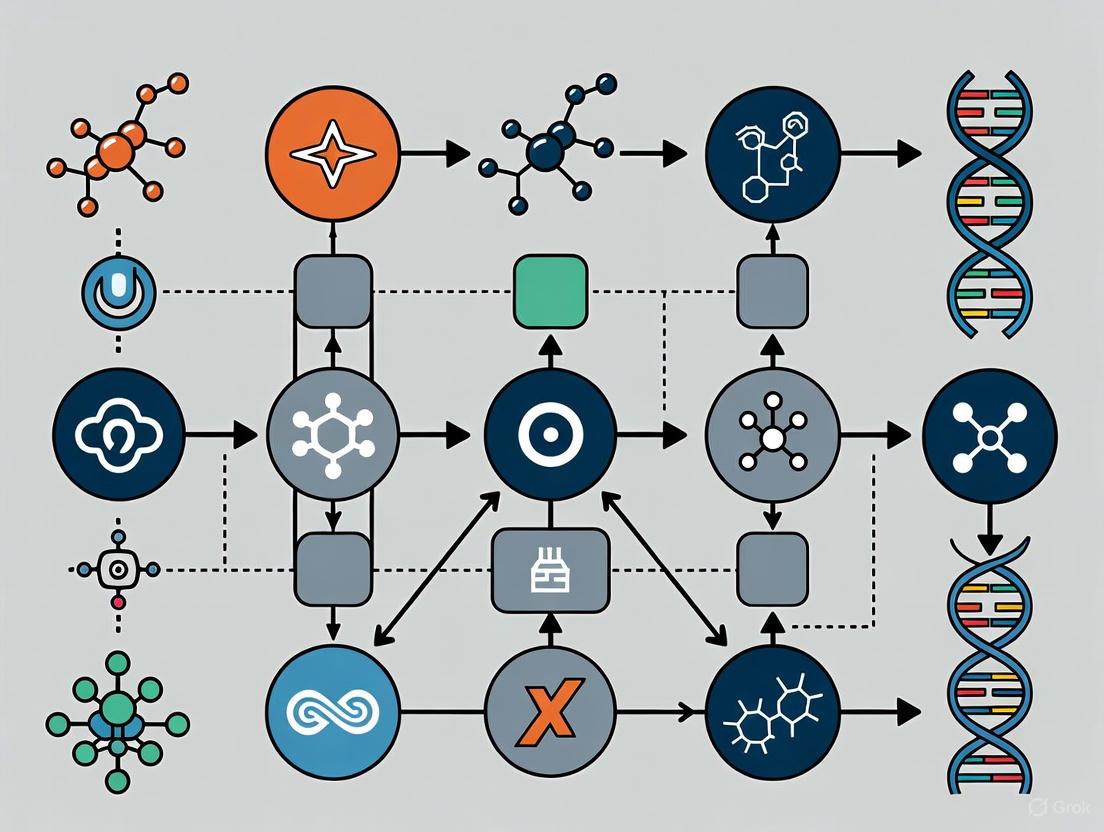

The standard evolutionary algorithm follows an iterative process that mirrors biological evolution. The diagram below illustrates this workflow:

Figure 1: Evolutionary algorithm workflow demonstrating the iterative process of population evolution

The process begins with population initialization, where an initial set of candidate solutions is generated, typically at random. This initial population should exhibit sufficient diversity to explore various regions of the search space [4] [2]. Each individual then undergoes fitness evaluation, where its performance is quantified according to the problem's objectives [1].

If termination criteria (e.g., satisfactory solution quality, maximum generations) are not met, the algorithm selects parents based on their fitness, with better solutions having higher selection probability [3]. Selected parents then undergo recombination (crossover), where genetic information is exchanged to produce offspring [4]. Subsequent mutation introduces random changes to maintain population diversity and explore new regions of the search space [3].

Newly created offspring are evaluated, and the population is updated through a replacement strategy. This generational cycle continues until termination criteria are satisfied, at which point the best solution(s) identified during the search are returned [1].

Current Advances in Evolutionary Optimization

Adaptive Multi-Objective Frameworks

Recent research has focused on developing adaptive optimization frameworks that combine multiple algorithms to handle complex multi-objective optimization challenges. One advanced approach utilizes a reinforcement learning-based agent that selects evolutionary operators during the optimization process based on real-time feedback [5]. This framework incorporates five single-objective evolutionary algorithm operators transformed for multi-objective optimization using the R2 indicator, which serves both to render the algorithm multi-objective and to evaluate each algorithm's performance in each generation [5].

Experimental evaluation of this adaptive framework using benchmark problems (CEC09 functions) with performance measures including inverted generational distance (IGD) and spacing (SP) demonstrated that it outperformed traditional methods with statistical significance (p<0.05) [5]. The reinforcement learning agent exhibited insightful selection patterns, initially favoring evolution strategies for exploration, then transitioning to genetic algorithms and teaching-learning-based optimization for balanced exploration and exploitation, and finally preferring exploitation-focused algorithms like equilibrium optimizer and whale optimization algorithm in later stages [5].

Large-Scale Multi-Objective Optimization

As optimization problems grow in complexity and scale, researchers have developed specialized algorithms for handling numerous decision variables alongside multiple objectives. The Collaborative Large-scale Multi-objective Optimization Algorithm with Adaptive Strategies (CLMOAS) addresses these challenges through innovative variable categorization and dominance relations [6].

CLMOAS employs k-means clustering to partition decision variables into convergence-related and diversity-related groups, applying distinct optimization strategies to each category [6]. This approach effectively balances convergence speed and solution diversity, critical aspects in large-scale optimization. Additionally, the algorithm incorporates an enhanced angle-based dominance relationship to reduce dominance resistance during optimization [6].

Experimental results on standard test sets (DTLZ and UF problems) demonstrated that CLMOAS achieves smaller inverted generational distance (IGD) values compared to mainstream algorithms like MOEA/D and LMEA, indicating superior performance in both convergence and diversity maintenance [6].

Robust Optimization Under Uncertainty

Real-world optimization problems often involve uncertainties that traditional evolutionary algorithms struggle to handle. A novel robust multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on surviving rate (RMOEA-SuR) addresses this challenge by explicitly considering both robustness and convergence as equally important objectives [7].

This approach introduces the concept of "surviving rate" as a robustness measure and reformulates the robust multi-objective optimization problem by adding robustness as a new objective [7]. The method employs precise sampling through multiple smaller perturbations around solutions after initial noise introduction, providing more accurate performance evaluation under practical noisy conditions [7].

Validation on nine test problems and one real-world application demonstrated the algorithm's superiority in both convergence and robustness compared to existing approaches under noisy conditions [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Implementing Adaptive Multi-Objective Optimization

Purpose: To implement a reinforcement learning-enhanced adaptive multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for complex optimization problems.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computing hardware: Multi-core processor (≥8 cores), 16GB+ RAM

- Software: Python 3.8+ with libraries: NumPy, SciPy, TensorFlow/PyTorch for RL component

- Benchmark datasets: CEC09 test functions

- Performance metrics: Inverted Generational Distance (IGD), Spacing (SP)

Procedure:

- Initialize Population:

- Set population size N (typically 100-500)

- Initialize population randomly within problem bounds

- Define maximum generations G (typically 200-1000)

Configure Algorithm Pool:

- Implement five diverse evolutionary operators:

- Genetic Algorithm (GA) with simulated binary crossover and polynomial mutation

- Evolution Strategies (ES) with self-adaptive mutation

- Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO)

- Equilibrium Optimizer (EO)

- Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA)

- Implement five diverse evolutionary operators:

Set Up Reinforcement Learning Agent:

- Implement Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) with:

- State space: Current population distribution characteristics

- Action space: Selection of evolutionary operator

- Reward function: Improvement in R2 indicator value

- Implement Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) with:

Evolutionary Process:

- For each generation g = 1 to G: a. Evaluate current population using R2 indicator b. RL agent selects operator based on current state c. Apply selected operator to generate offspring d. Evaluate offspring fitness e. Select survivors for next generation f. Update RL agent based on performance improvement

Termination and Analysis:

- Terminate when maximum generations reached or convergence stagnation detected

- Compute performance metrics (IGD, SP) on final population

- Compare against baseline non-adaptive algorithms

Validation: Statistical testing (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to confirm significance of performance improvements over traditional methods [5].

Protocol: Large-Scale Multi-Objective Optimization with CLMOAS

Purpose: To solve optimization problems with numerous decision variables and multiple objectives using clustering-based variable classification.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computing platform: PlatEMO framework or equivalent

- Test problems: DTLZ and UF benchmark suites

- Performance metrics: Inverted Generational Distance (IGD), Hypervolume

Procedure:

- Problem Initialization:

- Define problem dimensions: number of variables (100+), objectives (2-5)

- Set population size based on problem complexity

- Initialize population with uniform random sampling

Variable Classification:

- Apply k-means clustering to decision variables using angular similarity

- Determine optimal cluster count using elbow method

- Partition variables into convergence-related and diversity-related groups

Specialized Optimization:

- Apply convergence-focused strategies to convergence-related variables:

- Differential evolution with current-to-best mutation

- Neighborhood-based local search

- Apply diversity-maintaining strategies to diversity-related variables:

- Simulated binary crossover with large distribution index

- Polynomial mutation with higher probability

- Apply convergence-focused strategies to convergence-related variables:

Enhanced Dominance Application:

- Implement angle-based dominance relationship

- Calculate niche radius based on population distribution

- Adjust selection pressure dynamically based on evolutionary progress

Performance Evaluation:

- Compute IGD values every 50 generations

- Compare against MOEA/D, LMEA, and NSGA-III

- Statistical analysis of results over 30 independent runs

Validation: Performance superiority confirmed when CLMOAS achieves statistically smaller IGD values across multiple test problems [6].

Protocol: Robust Optimization Under Input Uncertainty

Purpose: To identify solutions that maintain performance despite input perturbations using surviving rate concepts.

Materials and Reagents:

- Test problems with known input perturbation characteristics

- Noisy evaluation environments simulating real-world conditions

- Performance metrics combining convergence and robustness

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation:

- Define nominal optimization problem with M objectives

- Specify input perturbation ranges for each variable

- Formulate robust counterpart problem with surviving rate objective

Two-Stage Optimization:

Stage 1: Evolutionary Optimization a. Initialize population with random solutions b. For each solution, apply precise sampling:

- Apply initial noise perturbation

- Apply multiple smaller perturbations around noisy solution

- Calculate average objective values across samples c. Calculate surviving rate for each solution d. Perform non-dominated sorting considering original objectives plus surviving rate e. Apply random grouping mechanism to maintain diversity

Stage 2: Robust Optimal Front Construction a. Evaluate solutions using combined convergence-robustness measure b. L0 norm average value represents convergence performance c. Surviving rate represents robustness d. Select solutions maximizing the product of convergence and robustness measures

Performance Assessment:

- Compare solutions against nominal optimal solutions

- Evaluate performance degradation under perturbations

- Measure robustness as performance variation across multiple noisy evaluations

Validation: Solutions demonstrate less than 5% performance degradation under specified input perturbations while maintaining proximity to Pareto optimal front [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational tools and frameworks for evolutionary algorithm research

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| R2 Indicator | Quality metric for solution sets considering convergence and distribution | Multi-objective optimization performance assessment [5] |

| Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) | Reinforcement learning agent for algorithm selection | Adaptive operator selection in meta-algorithms [5] |

| k-means Clustering | Partitioning method for decision variables | Variable classification in large-scale optimization [6] |

| Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) | Performance metric measuring proximity to reference set | Algorithm performance comparison and validation [6] |

| Surviving Rate Metric | Robustness measure evaluating performance under perturbation | Robust optimization in noisy environments [7] |

| Precise Sampling Mechanism | Multiple evaluation strategy around perturbed solutions | Accurate fitness assessment under uncertainty [7] |

| Non-dominated Sorting | Selection method for multi-objective optimization | Identifying Pareto-efficient solutions [5] |

Advanced Methodologies and Visualization

Multi-Objective Optimization Framework

Complex optimization problems often involve multiple conflicting objectives that must be simultaneously considered. The diagram below illustrates the structure of a modern multi-objective evolutionary algorithm:

Figure 2: Multi-objective evolutionary algorithm framework emphasizing Pareto optimality and diversity maintenance

Application in Drug Discovery

Evolutionary algorithms have demonstrated particular success in drug discovery applications, where they help navigate complex chemical spaces to identify promising candidate molecules. In one documented case, genetic algorithms were employed to search vast chemical spaces for drug-like molecules that effectively bind to target proteins [4]. This approach identified potential drug candidates for various diseases, significantly accelerating the discovery process compared to traditional methods.

The optimization process in drug discovery typically involves:

- Representation: Molecular structures encoded as strings or graphs

- Fitness Function: Binding affinity predictions combined with pharmacological properties

- Operators: Specialized crossover and mutation that maintain molecular validity

- Selection: Preference for molecules with optimal binding and safety profiles

This application demonstrates the power of evolutionary approaches to tackle high-dimensional problems with complex constraints, a common challenge in pharmaceutical development.

Evolutionary optimization algorithms represent a powerful approach for solving complex problems across diverse domains, from engineering design to drug discovery. By emulating principles of natural selection and genetics, these algorithms efficiently explore large, complex search spaces to identify optimal or near-optimal solutions.

Recent advances in adaptive frameworks, large-scale optimization, and robust algorithms under uncertainty have significantly enhanced the applicability of evolutionary approaches to real-world problems. The experimental protocols and methodologies presented here provide researchers with practical guidance for implementing these advanced techniques in their own work.

As optimization challenges continue to grow in scale and complexity, further research in evolutionary computation will likely focus on hybrid approaches combining evolutionary algorithms with other computational intelligence paradigms, improved adaptive mechanisms for algorithm selection, and enhanced methods for handling uncertainty and dynamic environments.

Swarm Intelligence and Collective Behavior in Particle Swarm Optimization

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a population-based metaheuristic algorithm belonging to the broader category of swarm intelligence, which is itself a subset of evolutionary computation techniques for complex problem optimization. Inspired by the collective social behavior of biological systems such as bird flocking and fish schooling, PSO was first introduced by Kennedy and Eberhart in 1995 and has since evolved into a powerful optimization tool for handling complex, multidimensional problem landscapes [8] [9]. The fundamental premise of PSO revolves around the concept that collective intelligence emerges from the relatively simple interactions of multiple individuals within a population, enabling the discovery of optimal solutions in challenging search spaces that often confound traditional optimization methods [10].

Within the context of evolutionary optimization algorithms, PSO distinguishes itself through its unique balance of individual (cognitive) and social (collective) learning components. Unlike genetic algorithms that rely on genetic operators of selection, crossover, and mutation, PSO maintains a population of candidate solutions that "fly" through the search space, dynamically adjusting their trajectories based on both personal experience and neighborhood knowledge [8] [11]. This approach has demonstrated particular efficacy in addressing the "5-M" challenges prevalent in complex continuous optimization problems: Many-dimensions, Many-changes, Many-optima, Many-constraints, and Many-costs [11]. The algorithm's simplicity of implementation, derivative-free mechanism, and efficient global search capabilities have contributed to its widespread adoption across diverse domains, including pharmaceutical research, where it has been applied to molecular drug-design evolution through platforms like AIDD [12].

Fundamental Principles and Algorithmic Mechanics

Core Algorithmic Components

The PSO framework operates through the coordinated movement of multiple particles within a defined search space, where each particle represents a potential solution to the optimization problem at hand. The algorithm's efficacy stems from the intricate balance and interaction of several key components that govern particle dynamics and collective behavior [8] [9]:

- Position (x_i): A vector in n-dimensional space representing the current candidate solution encoded by particle i

- Velocity (v_i): A vector determining the direction and magnitude of movement for particle i in the subsequent iteration

- Personal Best (pbest_i): The best solution (position with highest fitness) encountered by particle i throughout its search history

- Global Best (gbest): The best solution discovered by any particle within the entire swarm or a defined neighborhood

- Inertia Weight (w): A crucial parameter controlling the balance between exploration and exploitation by determining the influence of previous velocity on current movement

- Cognitive Coefficient (c1): A weighting factor determining the attraction of a particle toward its personal best position

- Social Coefficient (c2): A weighting factor determining the attraction of a particle toward the global best position discovered by the swarm

The dynamic interplay between these components creates the emergent intelligence characteristic of PSO, enabling the swarm to efficiently explore complex search spaces while effectively exploiting promising regions discovered during the optimization process.

Mathematical Formulation

The PSO algorithm operates through two fundamental equations that update particle velocity and position at each iteration. The velocity update equation incorporates three distinct components that contribute to a particle's movement trajectory [8] [9]:

Velocity Update Equation: vi(t+1) = w × vi(t) + c1 × r1 × (pbesti - xi(t)) + c2 × r2 × (gbest - x_i(t))

Position Update Equation: xi(t+1) = xi(t) + v_i(t+1)

Where r1 and r2 represent uniformly distributed random numbers in the range [0,1], introducing stochastic elements to the search process. The inertial component (w × vi(t)) maintains momentum from previous movements, the cognitive component (c1 × r1 × (pbesti - xi(t))) directs the particle toward its historical best position, and the social component (c2 × r2 × (gbest - xi(t))) attracts the particle toward the swarm's collective best discovery. This tripartite structure enables the algorithm to maintain diversity while efficiently converging toward promising regions of the search space [13] [9].

Operational Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard PSO workflow, depicting the sequential process from initialization through termination, highlighting key decision points and iterative refinement mechanisms:

Figure 1: Standard Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Workflow

Advanced Theoretical Developments (2015-2025)

Adaptive Parameter Control Strategies

Recent theoretical advancements in PSO have primarily focused on developing sophisticated parameter adaptation mechanisms to enhance algorithmic performance across diverse problem landscapes. The inertia weight parameter (w), which critically balances exploration and exploitation, has received particular attention, with numerous adaptation strategies emerging [13]:

- Time-Varying Schedules: Linear and nonlinear (exponential, logarithmic) decrease of w from high to low values over iterations, facilitating a smooth transition from global exploration to local refinement

- Randomized and Chaotic Inertia: Stochastic sampling of w from predefined distributions or chaotic sequences to prevent coordinated stagnation and enhance escape capabilities from local optima

- Feedback-Driven Adaptation: Dynamic adjustment of w based on real-time swarm characteristics including diversity metrics, velocity dispersion, and fitness improvement rates

- Compound Parameter Adaptation: Simultaneous adaptation of inertia weight and acceleration coefficients (c1, c2) using sophisticated control mechanisms including fuzzy logic, Bayesian inference, and machine learning techniques

Research by Sekyere et al. (2024) demonstrates that integrated adaptive dynamic inertia weight with adaptive acceleration coefficients (ADIWAC) significantly outperforms standard PSO variants on complex benchmark functions, highlighting the importance of coordinated parameter control [13].

Topological Variations and Population Dynamics

The social network structure governing information flow within the swarm represents another significant area of theoretical advancement, with research confirming that topology profoundly influences convergence characteristics and solution quality [13]:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of PSO Neighborhood Topologies

| Topology Type | Information Flow | Convergence Speed | Solution Quality | Best Suited Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Star (gbest) | Global: all particles connected | Fast | Risk of premature convergence | Unimodal, simple landscapes |

| Ring (lbest) | Local: immediate neighbors only | Slow | High diversity maintained | Multimodal, complex landscapes |

| Von Neumann | Grid: lattice connections | Moderate | Excellent balance | General-purpose optimization |

| Dynamic | Adaptive: changes during run | Variable | Enhanced global search | Dynamic, noisy environments |

The development of heterogeneous swarms, where particles employ different update strategies or parameter settings based on their performance characteristics, represents another significant innovation. For instance, Heterogeneous Cognitive Learning PSO (HCLPSO) partitions the population into superior and ordinary particles, with each category employing distinct learning strategies to maintain diversity while accelerating convergence [13].

Experimental Protocols and Application Guidelines

Standardized Experimental Setup

For rigorous evaluation and comparison of PSO variants, researchers should implement the following standardized experimental protocol, which has been widely adopted in the evolutionary computation community:

Phase 1: Algorithm Configuration

- Initialize swarm size to 30-50 particles for most applications, increasing to 100+ for high-dimensional problems (>500 dimensions) [11]

- Set acceleration coefficients c1 and c2 to 2.0 unless employing adaptive mechanisms, maintaining c1 + c2 ≤ 4.0 for stability

- Implement linearly decreasing inertia weight from 0.9 to 0.4 over the course of iterations as a baseline strategy

- Define neighborhood topology appropriate to problem characteristics (see Table 1)

Phase 2: Termination Criteria Definition

- Set maximum function evaluations to 10,000 × D, where D represents problem dimensionality [11]

- Implement precision-based stopping (ε < 10^-8) for convergence detection

- Include stagnation detection (no improvement over 500 consecutive iterations)

Phase 3: Performance Assessment

- Execute 30-50 independent runs with different random seeds to ensure statistical significance

- Employ comprehensive metrics including mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile ranges of best-found fitness values

- Conduct non-parametric statistical tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank) to validate performance differences

Benchmarking and Validation Framework

Comprehensive evaluation requires implementation of diverse benchmark suites to assess algorithmic performance across various problem characteristics:

Table 2: Standard Benchmark Functions for PSO Performance Evaluation

| Function Category | Representative Functions | Key Characteristics | PSO Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unimodal | Sphere, Schwefel 2.22 | Single optimum, convex | Convergence rate analysis |

| Multimodal | Rastrigin, Ackley | Many local optima | Premature convergence avoidance |

| Composite | CEC benchmark suite | Hybrid, rotated functions | Balance of exploration/exploitation |

| Real-World | Molecular docking, Neural network training | Noisy, expensive evaluations | Computational efficiency |

For drug discovery applications, researchers should incorporate specialized benchmarks including molecular docking simulations, quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, and pharmacokinetic parameter optimization to validate practical utility [12].

Application Notes for Pharmaceutical Research

Drug Discovery and Development Protocols

PSO has demonstrated significant utility in pharmaceutical research, particularly in molecular drug-design evolution platforms such as AIDD [12]. The following application protocol outlines the implementation of PSO for drug discovery optimization:

Protocol 1: Molecular Docking Optimization

Objective: Identify ligand configurations that minimize binding energy to target protein Parameter Mapping:

- Particle position: 3D coordinates and orientation angles of ligand molecule

- Velocity: Incremental changes in positional and rotational parameters

- Fitness function: Negative of binding affinity (to frame as minimization)

- Constraints: Bond lengths, angles, and torsions within chemically feasible ranges

Implementation:

- Initialize swarm with diverse ligand conformations within protein binding site

- Evaluate binding energies using scoring functions (AutoDock, Gold, Glide)

- Update particle trajectories toward personal and global best configurations

- Implement domain-specific mutation operators to maintain chemical feasibility

- Terminate when convergence criteria met or maximum evaluations reached

Protocol 2: QSAR Model Parameter Optimization

Objective: Optimize parameters in quantitative structure-activity relationship models to maximize predictive accuracy Parameter Mapping:

- Particle position: Coefficient values in QSAR regression equations

- Fitness function: Cross-validated R² or RMSE of predictive model

- Constraints: Coefficient ranges based on molecular descriptor significance

Implementation:

- Encode QSAR model parameters as particle positions

- Evaluate predictive performance using k-fold cross-validation

- Employ multi-objective PSO variants to balance model accuracy and complexity

- Implement feature selection through binary PSO for descriptor subset optimization

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and resources for implementing PSO in pharmaceutical research contexts:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PSO Implementation in Drug Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO Frameworks | FADSE 2.0, PlatEMO, JMetal | Algorithm implementation & testing | General optimization pipeline development |

| Drug Discovery Platforms | AIDD, ChemMORT | Domain-specific optimization | Molecular design, metabolism analysis |

| Benchmark Suites | CEC competitions, BBOB | Performance validation | Algorithm comparison & selection |

| Visualization Tools | VOSviewer, Matplotlib | Result analysis & clustering | Research trend mapping & reporting |

Advanced Methodologies for Complex Pharmaceutical Problems

Multi-Objective Optimization in Drug Development

Pharmaceutical optimization problems frequently involve multiple competing objectives, necessitating specialized multi-objective PSO (MOPSO) approaches. Key advancements include:

- Pareto Dominance Mechanisms: Implementation of non-dominated sorting and crowding distance metrics to maintain diverse approximation of Pareto front

- External Archive Management: Elite preservation strategies with density-based selection to prevent convergence to suboptimal regions

- Specialized Mutation Operators: Turbulence and neighborhood mutation to enhance exploration capabilities in objective space

For drug development applications, common multi-objective scenarios include simultaneously optimizing efficacy, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties while minimizing toxicity and synthesis complexity [12].

Constrained Handling Techniques

Pharmaceutical optimization problems typically incorporate numerous constraints derived from chemical feasibility, biological activity, and ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity) properties. Effective constraint handling strategies include:

- Penalty Function Methods: Transforming constrained problems into unconstrained formulations through adaptive penalty coefficients

- Feasibility Preference Rules: Prioritizing feasible solutions over infeasible ones while maintaining diversity at constraint boundaries

- Multi-population Approaches: Segregating populations to simultaneously explore feasible and infeasible regions

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive PSO workflow for drug discovery applications, integrating multi-objective optimization and constraint handling mechanisms:

Figure 2: Multi-objective PSO Workflow for Drug Discovery Applications

Performance Analysis and Validation Metrics

Quantitative Assessment Framework

Rigorous performance evaluation requires implementation of comprehensive metrics tailored to specific application domains:

Table 4: Performance Metrics for PSO Algorithm Validation

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Calculation Method | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solution Quality | Best Fitness, Mean Fitness | Statistical analysis over multiple runs | Lower values indicate better performance for minimization |

| Convergence Behavior | Success Rate, Convergence Generations | Proportion of successful runs meeting precision target | Higher success rates indicate greater reliability |

| Computational Efficiency | Function Evaluations, Execution Time | Count until convergence or maximum allowed | Fewer evaluations indicate higher efficiency |

| Diversity Metrics | Swarm Diversity, Position Entropy | Average distance from swarm centroid | Higher diversity reduces premature convergence risk |

| Multi-objective Performance | Hypervolume, Spread, Spacing | Volume of objective space dominated by solutions | Comprehensive assessment of Pareto front quality |

For pharmaceutical applications, domain-specific validation including synthetic accessibility scores, drug-likeness metrics (Lipinski's Rule of Five), and clinical endpoint predictions should supplement standard performance measures [12].

Particle Swarm Optimization represents a powerful paradigm within evolutionary computation, with demonstrated efficacy across diverse pharmaceutical optimization challenges. The continuous theoretical advancements in parameter adaptation, topological structures, and constraint handling mechanisms have significantly enhanced its applicability to complex drug discovery problems characterized by high dimensionality, multiple objectives, and expensive evaluations.

Future research directions should focus on enhancing PSO's capabilities for addressing emerging challenges in pharmaceutical research, including:

- Integration with deep learning architectures for enhanced predictive modeling

- Development of transfer learning mechanisms to leverage historical optimization data

- Implementation of automated algorithm configuration techniques for domain-specific adaptation

- Advancement of quantum-inspired PSO variants for molecular simulation acceleration

- Expansion of multi-fidelity optimization approaches balancing computational cost and model accuracy

As swarm intelligence continues to evolve, PSO is positioned to play an increasingly significant role in addressing the complex optimization challenges inherent in modern drug development pipelines, particularly through its ability to efficiently navigate high-dimensional, multi-modal search spaces while balancing multiple competing objectives.

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are powerful evolutionary optimization techniques inspired by natural selection, providing robust solutions to complex problems across diverse fields including drug discovery, engineering, and artificial intelligence [14]. These algorithms maintain a population of candidate solutions that undergo iterative improvement through the application of selection, crossover, and mutation operators [15]. This cyclic process of evaluation and variation allows GAs to effectively explore vast, complex search spaces where traditional optimization methods may fail [14]. Within evolutionary optimization research for complex problems, these mechanisms work synergistically to balance the exploration of new solution regions with the exploitation of known promising areas [16]. The strategic implementation of these operators is particularly valuable for multi-objective problems with conflicting criteria, such as optimizing drug therapies for both efficacy and safety, or engineering designs that must balance multiple performance metrics [17] [18].

Selection Mechanisms

Selection operators drive the evolutionary process toward improved solutions by determining which individuals from the current population are chosen to reproduce based on their fitness [16]. This process creates a crucial balance between exploitation (selecting the best-performing individuals) and exploration (maintaining sufficient diversity within the population) [16]. The selection pressure applied by these operators significantly impacts the algorithm's convergence rate and ultimate solution quality. If selection pressure is too high, the population may converge prematurely to suboptimal solutions; if too low, the search process may become inefficient [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Selection Mechanisms

| Selection Operator | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tournament Selection | Randomly selects a subset of individuals (tournament size k) and chooses the fittest among them [16] | Computationally efficient, tunable selection pressure via tournament size, less sensitive to fitness scaling [16] | May require parameter tuning for optimal tournament size | Large populations, problems with noisy fitness evaluations [16] |

| Roulette Wheel Selection | Assigns selection probabilities proportional to individual fitness values [16] | Maintains direct relationship between fitness and selection probability | Sensitive to extreme fitness values, may lead to premature convergence [16] | Well-scaled fitness functions with moderate variance |

| Rank-Based Selection | Selects individuals based on their fitness rank rather than absolute values [16] | Reduces dominance of super-individuals, maintains consistent selection pressure | Requires sorting population by fitness each generation | Populations with high fitness variance or stagnation issues |

| Elitism | Directly copies a small percentage of the fittest individuals to the next generation [16] | Preserves best solutions found, guarantees non-decreasing performance | May reduce diversity if overused | Most GA implementations as a supplementary strategy |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Selection Operators

Objective: To quantitatively compare the performance of different selection operators on a specific optimization problem.

Materials: Standard GA framework, benchmark problem (e.g., 0/1 Knapsack Problem or Bit Counting Problem [19]), computing infrastructure.

Methodology:

- Initialization: Generate an initial population of candidate solutions randomly. Population size should be set appropriately for the problem domain [20].

- Parameter Setup: Configure identical parameters across experiments: population size (e.g., 100-500), crossover rate (e.g., 0.7-0.9), mutation rate (e.g., 0.01-0.001), and termination condition (e.g., number of generations or fitness threshold) [15].

- Experimental Groups: Implement multiple GA variants differing only in selection operators (Tournament, Roulette Wheel, Rank-Based).

- Evaluation Metrics: Track multiple performance indicators throughout generations:

- Best and average fitness

- Convergence generation

- Population diversity metrics

- Computational time per generation

- Statistical Analysis: Execute multiple independent runs (30+ recommended) for each configuration and perform statistical comparison (e.g., ANOVA) to determine significant performance differences [19].

Diagram 1: Selection operator experimental workflow.

Crossover Operators

Types and Mechanisms

Crossover (recombination) operators combine genetic information from two or more parent solutions to create novel offspring, facilitating the exploitation of beneficial genetic patterns [15] [20]. By exchanging and recombining genetic material, crossover operators preserve and propagate "building blocks" - beneficial combinations of genes that contribute to solution quality [16]. The crossover rate parameter determines the probability of applying crossover to selected parent solutions, with higher rates typically set at 0.7-0.9 to promote greater exploration of solution combinations [15].

Table 2: Crossover Operator Types and Characteristics

| Crossover Type | Mechanism | Representation | Properties | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Point | Selects one random crossover point; swaps all data beyond that point between parents [20] | Binary, Integer | Simple, fast, may disrupt good building blocks | Basic GA implementations, simple representations [20] |

| Two-Point | Selects two random points; swaps genetic material between them [16] | Binary, Integer | Better building block preservation | Problems where genes are interdependent |

| Uniform | Each gene is independently swapped between parents with a fixed probability (e.g., 0.5) [16] | Binary, Integer, Real-valued | High exploration, maximum disruption | Maintaining diversity, highly multimodal problems |

| Arithmetic | Creates offspring as weighted average of parent values [16] | Real-valued | Produces intermediate solutions, smooth search | Continuous parameter optimization, numerical problems |

| Order (OX) | Preserves relative order of genes from parents [16] | Permutation | Maintains permutation validity | Scheduling, routing (TSP), ordering problems |

| Partially Mapped (PMX) | Maps segments between parents to ensure validity [16] | Permutation | Complex but highly effective for permutations | Complex combinatorial problems |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Crossover Effectiveness

Objective: To evaluate the performance of different crossover operators on a specific problem domain.

Materials: GA framework with modular operator implementation, fitness evaluation function, data logging system.

Methodology:

- Problem Encoding: Design appropriate chromosomal representation for the target problem (binary, real-valued, or permutation) [20].

- Operator Implementation: Implement multiple crossover operators appropriate for the representation.

- Control Variables: Maintain consistent selection (e.g., tournament selection) and mutation operators across experiments.

- Performance Tracking: Monitor:

- Solution quality improvement rate

- Building block preservation (problem-specific)

- Diversity maintenance throughout evolution

- Convergence behavior analysis

- Advanced Analysis: For permutation problems, implement specialized crossover operators (OX, PMX) and measure constraint satisfaction and solution feasibility rates [16].

Mutation Operators

Types and Mechanisms

Mutation operators introduce random changes to individual solutions, serving as a primary mechanism for exploration and diversity maintenance in genetic algorithms [16] [20]. By making small, stochastic alterations to chromosomal content, mutation helps prevent premature convergence to local optima and ensures the continued exploration of the search space [15]. The mutation rate parameter typically remains low (0.001-0.01) to avoid degrading the population toward random search, though adaptive mutation schemes can dynamically adjust this rate based on population diversity metrics [15] [16].

Table 3: Mutation Operator Specifications

| Mutation Operator | Mechanism | Representation | Parameters | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bit-Flip | Randomly flips bits from 0 to 1 or vice versa with probability p [20] | Binary | Mutation rate (p) | Basic binary-coded problems, Knapsack problems [19] |

| Gaussian | Adds random noise drawn from Gaussian distribution to gene values [16] | Real-valued | Mutation rate, Standard deviation (σ) | Continuous optimization, fine-tuning solutions |

| Uniform | Replaces gene with random value from specified range [16] | Real-valued, Integer | Mutation rate, Value range | Broad exploration, escaping local optima |

| Swap | Randomly selects two genes and exchanges their positions [16] | Permutation | Mutation rate | Order-based problems, scheduling |

| Inversion | Reverses the order of genes between two randomly chosen points [16] | Permutation | Mutation rate | Combinatorial problems, enhancing diversity |

| Scramble | Randomly reorders a subset of selected genes [16] | Permutation | Mutation rate, Segment size | Complex permutation problems |

Experimental Protocol: Mutation Rate Optimization

Objective: To determine optimal mutation rates for a specific problem domain and analyze the exploration-exploitation trade-off.

Materials: GA implementation, problem instance, parameter tuning framework.

Methodology:

- Parameter Range Identification: Establish a range of mutation rates to test (e.g., 0.001 to 0.1).

- Experimental Design: Execute multiple GA runs with different mutation rates while keeping other parameters constant.

- Data Collection: Record:

- Generations to convergence

- Final solution quality

- Population diversity throughout run

- Number of fitness evaluations

- Analysis: Identify mutation rates that provide the best balance between solution quality and convergence speed. Analyze the relationship between mutation rate and population diversity metrics.

Diagram 2: Crossover and mutation operation flow.

Parameter Tuning and Balance

Probability Optimization Guidelines

The performance of genetic algorithms depends critically on the appropriate balance between crossover and mutation probabilities, which directly controls the trade-off between exploration and exploitation [15]. Optimal parameter settings are often problem-dependent and require empirical determination, though general guidelines exist based on problem characteristics and population dynamics [15].

Table 4: Probability Tuning Guidelines Based on Problem Characteristics

| Problem Characteristic | Crossover Probability | Mutation Probability | Rationale | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Search Space | Low (0.6-0.7) | Low (0.001-0.01) | Reduced need for exploration | Focus on exploitation, smaller populations sufficient |

| Large/Complex Search Space | High (0.8-0.95) | Moderate (0.01-0.05) | Enhanced exploration capability | Maintain diversity, prevent premature convergence [15] |

| Multimodal Fitness Landscape | Moderate (0.7-0.85) | High (0.05-0.1) | Escape local optima, explore multiple regions | May require niching techniques with selection |

| Real-Valued Representation | High (0.8-0.9) | Low (0.001-0.02) | Blend crossover effective for real values | Gaussian mutation with adaptive step sizes [16] |

| Permutation Problems | Moderate (0.7-0.8) | Moderate (0.02-0.08) | Specialized operators maintain feasibility | Often uses higher mutation than binary representations |

Advanced Tuning Strategies

For complex optimization scenarios, particularly in multi-objective problems, advanced parameter control strategies often outperform fixed probabilities. Adaptive parameter control automatically adjusts probabilities based on population diversity metrics or performance feedback [16]. Self-adaptive parameters encode operator probabilities within chromosomes, allowing them to evolve alongside solutions [15]. In multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (MOEAs), parameter tuning must balance convergence toward the Pareto front with maintenance of diverse solution coverage [17].

Application Protocol: Drug Discovery Optimization

Case Study: Multi-Objective Drug Therapy Optimization

Background: Drug development requires simultaneous optimization of multiple conflicting objectives: efficacy, safety, toxicity, and production cost [18]. Multi-objective genetic algorithms (MOGAs) effectively address these challenges by generating diverse Pareto-optimal solutions representing trade-offs between objectives [18].

Experimental Protocol:

Problem Formulation:

- Decision Variables: Molecular descriptors, structural features, dosage parameters

- Objectives: Maximize efficacy, minimize toxicity, reduce cost

- Constraints: Pharmacokinetic properties, synthetic feasibility

Chromosome Encoding: Represent drug candidate as a real-valued vector of molecular descriptors or a binary string representing structural fragments [18].

Multi-Objective GA Configuration:

- Selection: Tournament selection based on Pareto dominance and crowding distance

- Crossover: Blend crossover (α=0.5) for real-valued representations

- Mutation: Gaussian mutation with adaptive step sizes

- Elitism: Preserve non-dominated solutions between generations

Evaluation Metrics:

- Hypervolume indicator measuring dominated space

- Spacing metric assessing distribution along Pareto front

- Number of non-dominated solutions

Validation: Experimental validation of top Pareto-optimal candidates through in vitro testing [18].

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for GA Applications in Drug Discovery

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA Frameworks | DEAP, TPOT, Optuna [14] | Provide modular implementations of GA operators | Rapid prototyping, experimental comparisons |

| Multi-Objective Algorithms | NSGA-II, NSGA-III, SPEA2 [17] | Handle multiple conflicting objectives | Drug therapy optimization, engineering design [18] |

| Fitness Evaluation | Molecular docking simulations, QSAR models [18] | Estimate drug efficacy and binding affinity | In silico drug candidate screening |

| Visualization Tools | Search trajectory networks, Pareto front plots [19] | Analyze algorithm performance and solution quality | Algorithm debugging, result presentation |

| Statistical Analysis | Linear mixed models, ANOVA [21] | Validate significance of results | Experimental analysis, parameter tuning |

The strategic implementation of selection, crossover, and mutation mechanisms forms the foundation of effective genetic algorithms for complex problem optimization. By understanding the properties and interactions of these operators, researchers can design more efficient evolutionary algorithms tailored to specific problem characteristics. The experimental protocols and guidelines presented here provide a structured approach for investigating these operators across various domains, particularly in computationally intensive fields like drug discovery where multi-objective optimization is essential. As genetic algorithms continue to evolve through integration with machine learning and other computational intelligence paradigms [14] [17], these core evolutionary operators remain central to their effectiveness in solving complex real-world problems.

Application Note: Theoretical Analysis in Evolutionary Optimization

Core Conceptual Framework

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) have established themselves as a cornerstone methodology for solving complex, high-dimensional, and nonlinear optimization problems across numerous scientific and engineering disciplines [22]. The theoretical underpinnings of EAs, particularly convergence analysis and stability frameworks, provide critical insights into their long-term behavior, reliability, and performance guarantees. These foundations are not merely academic exercises; they inform the design of more robust and efficient algorithms capable of tackling real-world challenges, such as those encountered in computational drug design [22] [23].

Convergence analysis investigates the conditions under which an algorithm can be expected to approach the true optimal solution, while stability frameworks examine the sensitivity and robustness of the algorithm to perturbations in parameters, problem landscapes, or initial conditions. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these theoretical aspects is vital for selecting, configuring, and trusting these algorithms with expensive, real-world problems like molecular docking and in silico drug screening [23].

Quantitative Foundations of Convergence

The table below summarizes key quantitative measures and criteria central to the theoretical analysis of optimization algorithms, derived from foundational research.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Convergence and Stability Analysis

| Metric / Criterion | Theoretical Definition | Interpretation in EA Context |

|---|---|---|

| Regret Bound | A performance metric comparing the cumulative loss of the online algorithm to that of the best fixed decision in hindsight [24]. | Evaluates how well an EA performs over time compared to a hypothetical optimal strategy, guiding the choice of optimizer for a given dataset and loss function [24]. |

| Convexity Assumption | The loss function is convex, and its gradient is Lipschitz continuous [24]. | A common simplifying assumption that facilitates theoretical analysis of algorithm convergence, though many real-world problems are non-convex. |

| Lipschitz Continuity | There exists a constant L such that ||∇f(x) - ∇f(y)|| ≤ L ||x - y|| for all x, y [24]. | Ensures the gradient of the loss function does not change arbitrarily quickly, which is crucial for guaranteeing stable and convergent behavior. |

| Contrast Ratio (Visualization) | A measure of luminance difference between two colors, expressed as a ratio from 1:1 to 21:1 [25]. | While related to accessibility, the principle of measurable, sufficient contrast is analogous to ensuring algorithmic states are sufficiently distinguishable for analysis. |

The regret bound is one of the basic criteria for evaluating optimizer performance, and analyzing the differences between the bounds of traditional and adaptive algorithms can guide the choice of optimizer with respect to a given dataset and loss function [24].

Experimental Protocols for Convergence and Stability Analysis

Protocol: Benchmarking Convergence Performance

1. Objective: To empirically evaluate and compare the convergence properties of different evolutionary algorithms on a set of benchmark problems.

2. Materials and Reagents (The Scientist's Toolkit):

Table 2: Essential Computational Reagents for Convergence Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Benchmark Problem Suite | Provides standardized, well-understood fitness landscapes (e.g., convex, multi-modal, ill-conditioned) to test algorithm performance. |

| Exploratory Landscape Analysis (ELA) Features | A set of numerical features (e.g., fitness, meta-black-box optimization) that characterize the geometry of the optimization landscape and algorithm state [26]. |

| Surrogate Model (e.g., TabPFN) | An efficient, approximate model of the expensive true objective function, used to reduce computational cost during search while providing uncertainty estimates [26]. |

| Performance Metrics Logger | Software to track iteration count, best fitness, population diversity, and computational time at fixed intervals. |

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Initialization. For each algorithm (e.g., Genetic Algorithm, Differential Evolution, DB-SAEA), initialize multiple independent runs with different random seeds. Define a maximum number of function evaluations (budget).

- Step 2: Iterative Evaluation and State Capture. Run each algorithm. At predetermined intervals (e.g., every 100 evaluations), record the current best solution, its fitness value, and the current population distribution.

- Step 3: State Representation (for MetaBBO). In advanced frameworks like DB-SAEA, construct a bi-space landscape representation. This involves capturing the population from both the true evaluation space, ( \mathcal{P}{\text{true}} = { (\bm{x}i, \bm{y}i) | \bm{y}i = \bm{f}(\bm{x}i) } ), and the surrogate evaluation space, ( \mathcal{P}{\text{sur}} = { (\bm{x}i, \hat{\bm{y}}i, \hat{\bm{\sigma}}i) | \hat{\bm{y}}i = \hat{\bm{f}}(\bm{x}i) } ), where ( \hat{\bm{\sigma}}i ) is the predictive uncertainty [26].

- Step 4: Termination and Analysis. Terminate runs upon convergence (stagnation of fitness improvement) or when the evaluation budget is exhausted. Plot average convergence curves (fitness vs. evaluation count) across all runs for each algorithm. Statistically compare final fitness values and convergence speed.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this benchmarking protocol, integrating the bi-space analysis from the DB-SAEA framework.

Protocol: Analyzing Stability via Parameter Sensitivity

1. Objective: To assess the stability and robustness of an evolutionary algorithm by evaluating its performance sensitivity to variations in its control parameters.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- The algorithm under test (e.g., a Surrogate-Assisted EA).

- A design-of-experiments (DoE) setup for parameter perturbation.

- Statistical analysis software (e.g., for ANOVA or regression analysis).

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Parameter Selection. Identify key algorithm parameters to study (e.g., mutation rate, crossover probability, population size, infill criterion selection weight in a meta-policy).

- Step 2: Experimental Design. Define a range of values for each parameter using a full-factorial or fractional-factorial design.

- Step 3: Execution. For each parameter combination in the DoE, execute multiple runs of the algorithm on a fixed set of benchmark problems.

- Step 4: Stability Metric Calculation. For each set of runs, calculate performance metrics (e.g., mean best fitness, standard deviation of best fitness, success rate). The standard deviation of performance across runs for a single parameter set is a direct measure of its inherent stability.

- Step 5: Sensitivity Analysis. Perform analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine which parameters have the most significant impact on performance variability. This identifies parameters that require careful tuning for stable performance.

The logical relationship between parameter perturbation and stability assessment is shown below.

Application in Drug Design: A Case Study Protocol

Protocol: De Novo Molecular Design using Evolutionary Algorithms

1. Objective: To employ an evolutionary algorithm for the de novo design of novel drug-like molecules with high predicted activity against a specific biological target.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Ligand-Receptor Docking Software: To evaluate the binding affinity of generated molecules (e.g., AutoDock).

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Model: A surrogate model to predict bioactivity or other physicochemical properties (e.g., permeability, toxicity) [23].

- Chemical Rule Set: A set of constraints (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) to ensure generated molecules are drug-like.

- Molecular Representation: A encoding for the genome of a molecule (e.g., SMILES string, graph representation, molecular fingerprint).

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Problem Formulation. Define the multi-objective fitness function. This typically includes maximizing predicted binding affinity (from the QSAR/docking surrogate), minimizing synthetic complexity, and optimizing Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties [23].

- Step 2: Algorithm Configuration. Implement a multi-objective EA (e.g., NSGA-II, MOEA/D) or a meta-algorithm like DB-SAEA. The genome represents a molecule, and operators include mutation (e.g., atom substitution, bond change) and crossover (fragment swapping).

- Step 3: Meta-Optimization Loop. In a framework like DB-SAEA, the meta-policy uses the bi-space ELA—analyzing both the true property space (from expensive docking) and the surrogate-predicted space—to dynamically control the infill criterion. It decides whether to run a costly true docking evaluation or to rely on the surrogate's prediction for a given candidate molecule [26].

- Step 4: Iteration and Selection. The algorithm iterates, generating new molecules, evaluating them via the fitness function, and selecting the best for reproduction. The process continues until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., a molecule with sufficiently high fitness is found, or the computational budget is exhausted).

- Step 5: Output and Validation. The output is a Pareto front of non-dominated candidate molecules. Top candidates from this front are then recommended for in vitro synthesis and biological validation.

The following diagram maps this complex, adaptive workflow for drug discovery.

Multi-objective Optimization and Pareto Optimality Concepts

Multi-objective optimization (MOO) represents a fundamental class of problems in multiple-criteria decision-making where multiple objective functions must be optimized simultaneously [27]. In scientific and engineering contexts, problems frequently involve numerous, often conflicting, objectives that must be balanced against one another. Unlike single-objective optimization, MOO does not typically yield a single optimal solution but rather a set of solutions representing different trade-offs among the objectives [28].

The mathematical formulation of a multi-objective optimization problem can be expressed as minimizing a vector of objective functions: min┬x∈X(f₁(x), f₂(x),…,fₖ(x)) where the integer k ≥ 2 represents the number of objective functions, X denotes the feasible decision space, and f(x) maps to the objective vector in R^k [27]. This framework is particularly relevant to evolutionary optimization algorithms, which are well-suited for exploring complex solution spaces and approximating the set of Pareto optimal solutions through population-based search mechanisms [29].

In drug discovery and development, success depends on the simultaneous control of numerous, often conflicting, molecular and pharmacological properties [30]. This field presents a classic multi-objective optimization challenge where researchers must balance competing criteria such as binding affinity, solubility, toxicity, and metabolic stability [31]. The application of MOO strategies enables the systematic exploration of these trade-offs, capturing the occurrence of varying optimal solutions based on compromises among the objectives under consideration [30].

Fundamental Concepts of Pareto Optimality

Pareto Dominance and Efficiency

The concept of Pareto optimality provides the theoretical foundation for comparing solutions in multi-objective optimization. A solution x¹ ∈ X is said to dominate another solution x² ∈ X (denoted as x¹ ≺ x²) if two conditions are satisfied [28]:

- ∀ i ∈ {1,…,k}, fi(x¹) ≤ fi(x²) - The solution

x¹is no worse thanx²in all objectives - ∃ j ∈ {1,…,k}, fj(x¹) < fj(x²) - The solution

x¹is strictly better thanx²in at least one objective

A solution is classified as Pareto optimal or non-dominated if no other feasible solution dominates it [27]. The collection of all Pareto optimal solutions constitutes the Pareto set, while the corresponding objective vectors form the Pareto front [27]. In practical applications, the Pareto front represents the set of optimal trade-offs where no objective can be improved without degrading at least one other objective.

Ideal and Nadir Vectors

The objective space in MOO is bounded by two significant reference points:

- Ideal vector:

z^ideal = (inf┬x*∈X* f₁(x*), …, inf┬x*∈X* f_k(x*))representing the best theoretically achievable values for each objective individually [27] - Nadir vector:

z^nadir = (sup┬x*∈X* f₁(x*), …, sup┬x*∈X* f_k(x*))representing the worst objective values among the Pareto optimal solutions [27]

These vectors define the bounds of the Pareto front and provide critical reference points for decision-making and optimization algorithms.

Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms

Algorithmic Approaches and Classification

Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEAs) have significantly advanced the domain of MOO by providing effective mechanisms for solving complex problems with multiple conflicting objectives [29]. These algorithms can be broadly categorized into three main classes:

- Pareto-based methods: Utilize Pareto dominance relations to guide the selection process

- Decomposition-based methods: Break the MOO problem into multiple single-objective subproblems

- Indicator-based methods: Use performance indicators to drive the search process

The historical development of MOEAs has seen substantial progress in both theoretical foundations and practical applications, with ongoing research addressing challenges such as high-dimensional objective spaces and computationally expensive function evaluations [29].

Dominance-Based Algorithms

NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm-II) represents one of the most widely used Pareto-based MOEAs [28]. Its operational workflow involves several key steps as illustrated below:

The algorithm employs non-dominated sorting to classify solutions into different Pareto fronts and uses crowding distance estimation to preserve diversity within the population [28]. This combination enables NSGA-II to maintain a well-distributed approximation of the true Pareto front across generations.

Decomposition-Based Algorithms

MOEA/D (Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Decomposition) adopts a fundamentally different approach by decomposing the multi-objective problem into multiple single-objective optimization subproblems [28]. The algorithm solves these subproblems simultaneously using an evolutionary approach while leveraging neighborhood information to enhance efficiency. This decomposition strategy allows MOEA/D to effectively handle problems with complex Pareto fronts and has demonstrated competitive performance across various application domains.

Application in Drug Discovery and Development

Multi-Objective Challenges in Pharmaceutical Research

Drug discovery represents a quintessential multi-objective optimization problem where success depends on simultaneously satisfying numerous pharmaceutical criteria [31]. The process is characterized by vast, complex solution spaces further complicated by the presence of conflicting objectives [31]. Key objectives typically include:

- Binding affinity towards the target protein

- Selectivity against off-target interactions

- Solubility and pharmacokinetic properties

- Metabolic stability and low toxicity

- Synthetic accessibility and cost considerations

The conflicting nature of these objectives creates significant challenges; for example, structural modifications that enhance binding affinity often adversely affect solubility or increase toxicity [32]. This necessitates careful trade-off analysis throughout the optimization process.

MOO Methods in Drug Design

Multi-objective optimization techniques have been successfully applied across various stages of drug discovery, including quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, molecular docking, de novo design, and compound library design [31]. The table below summarizes key application areas and their respective optimization challenges:

Table 1: Multi-Objective Optimization Applications in Drug Discovery

| Application Area | Primary Objectives | Key Challenges | Common MOO Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Design | Diversity, Drug-likeness, Structural Complexity | Balancing exploration vs. exploitation | Pareto-based ranking, Desirability functions |

| QSAR Modeling | Predictive Accuracy, Interpretability, Robustness | Handling noisy data, Feature selection | NSGA-II, MOEA/D, Hybrid algorithms |

| Molecular Docking | Binding Affinity, Specificity, Pose Accuracy | Scoring function conflicts | Multi-objective Bayesian optimization |

| De Novo Design | Potency, Synthesizability, ADMET properties | Navigating vast chemical space | Evolutionary algorithms with preference learning |

| Hit-to-Lead | Efficacy, Selectivity, Pharmacokinetics | Resource-intensive experimental validation | Preference-based MOO, Human-in-the-loop |

The widespread adoption of these multi-objective techniques has created new opportunities in medicinal chemistry, with applications emerging in both academic research and pharmaceutical industry workflows [30].

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Preferential Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization for Virtual Screening

Recent advancements have integrated human expertise directly into the optimization loop through preferential multi-objective Bayesian optimization. The CheapVS framework exemplifies this approach by allowing chemists to guide ligand selection through pairwise comparisons of trade-offs between drug properties [33] [32].

Experimental Protocol 1: Expert-Guided Virtual Screening

- Initialization: Begin with a diverse subset of ligands (typically 0.5-1% of the screening library

ℒ = {ℓ₁,…,ℓ_N}) [32] - Property Evaluation: Measure molecular property vector

x_ℓfor each ligand in the initial set, including binding affinity, solubility, and toxicity proxies [32] - Surrogate Modeling: Train a Bayesian model on the initial data to predict properties across the chemical space [32]

- Preference Elicitation: Present chemists with pairwise comparisons of candidate ligands representing different property trade-offs [33]

- Acquisition Function Optimization: Use preferential multi-objective Bayesian optimization to select the next batch of ligands for evaluation based on expected utility improvement [32]

- Iterative Refinement: Repeat steps 2-5 until computational budget is exhausted or convergence criteria are met [33]

This protocol was validated on a library of 100,000 chemical candidates targeting EGFR and DRD2, successfully recovering 16/37 EGFR and 37/58 DRD2 known drugs while screening only 6% of the library [33].

Reaction Prediction and Molecular Optimization for Hit-to-Lead Progression

An integrated medicinal chemistry workflow demonstrates the application of MOO in accelerating hit-to-lead optimization [34]. The methodology combines high-throughput experimentation with multi-objective molecular optimization:

Experimental Protocol 2: Hit-to-Lead Multi-Objective Optimization

- Reaction Dataset Generation: Employ high-throughput experimentation to generate comprehensive reaction data (e.g., 13,490 Minisci-type C-H alkylation reactions) [34]

- Predictive Model Training: Train deep graph neural networks to accurately predict reaction outcomes [34]

- Virtual Library Enumeration: Perform scaffold-based enumeration of potential reaction products from starting compounds (e.g., generating 26,375 virtual molecules from moderate MAGL inhibitors) [34]

- Multi-Objective Evaluation: Assess the virtual library using reaction prediction, physicochemical property assessment, and structure-based scoring [34]

- Compound Selection and Synthesis: Identify top candidates balancing multiple objectives and synthesize selected compounds for experimental validation [34]

- Structural Analysis: Conduct co-crystallization studies to verify binding poses and extract structural insights [34]

This protocol achieved a potency improvement of up to 4,500 times over the original hit compound, with 14 synthesized ligands exhibiting subnanomolar activity and favorable pharmacological profiles [34].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

The implementation of multi-objective optimization in drug discovery requires specialized computational tools and methodological approaches. The table below outlines key components of the researcher's toolkit for MOO applications:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Objective Optimization in Drug Discovery

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithms | NSGA-II, MOEA/D, MEMS | Population-based global optimization | Pareto front approximation, High-dimensional problems |

| Bayesian Optimization | Preferential MOBO, CheapVS | Sequential decision-making with uncertainty | Expensive function evaluation, Human preference integration |

| Constraint Handling | Penalty functions, Feasibility rules, ε-constraint | Managing feasibility boundaries | Engineering design, Property-constrained molecular optimization |

| Decomposition Methods | Weighted sum, Tchebycheff approach, Boundary intersection | Problem simplification | Many-objective optimization, Preference incorporation |

| Hybrid Algorithms | Memetic algorithms, Co-evolutionary strategies | Combining global and local search | Complex Pareto fronts, Multimodal problems |

| Preference Learning | Pairwise comparison, Utility models, Desirability functions | Capturing domain knowledge | Decision support, Hit prioritization |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Constraint Handling Techniques

Real-world optimization problems invariably include constraints that must be satisfied for solutions to be feasible. Constrained optimization problems (COPs) can be formulated as minimizing f(x) subject to g_j(x) ≤ 0 for inequality constraints and h_j(x) = 0 for equality constraints [35]. The constraint violation degree for a solution x is computed as G(x) = ∑_(j=1)^m G_j(x), where G_j(x) represents the violation of the j-th constraint [35].

Evolutionary algorithms employ various constraint-handling techniques, which can be categorized into four main approaches [35]:

- Penalty Function Methods: Transform constrained problems into unconstrained ones by adding penalty terms to the objective function based on constraint violations [35]

- Feasibility Preference Methods: Prioritize feasible solutions over infeasible ones using feasibility rules or stochastic ranking [35]

- Multi-Objective Methods: Treat constraints as additional objectives to be optimized [35]

- Hybrid Techniques: Combine multiple constraint-handling strategies based on population characteristics [35]

The effectiveness of these methods depends on problem characteristics such as the size of the feasible region, the topology of constraints, and the location of optimal solutions relative to constraint boundaries.

Memetic and Hybrid Algorithms

Memetic algorithms represent a class of optimization strategies that combine evolutionary algorithms with local search techniques [28]. These hybrid approaches leverage the global exploration capabilities of population-based evolutionary methods while incorporating local exploitation through problem-specific refinement.

The synergy between global and local search enables memetic algorithms to achieve improved solution quality and convergence speed compared to standard evolutionary approaches, particularly for complex optimization landscapes with numerous local optima [28].