Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization for Discrete Problems: A Research Guide for Biomedical Applications

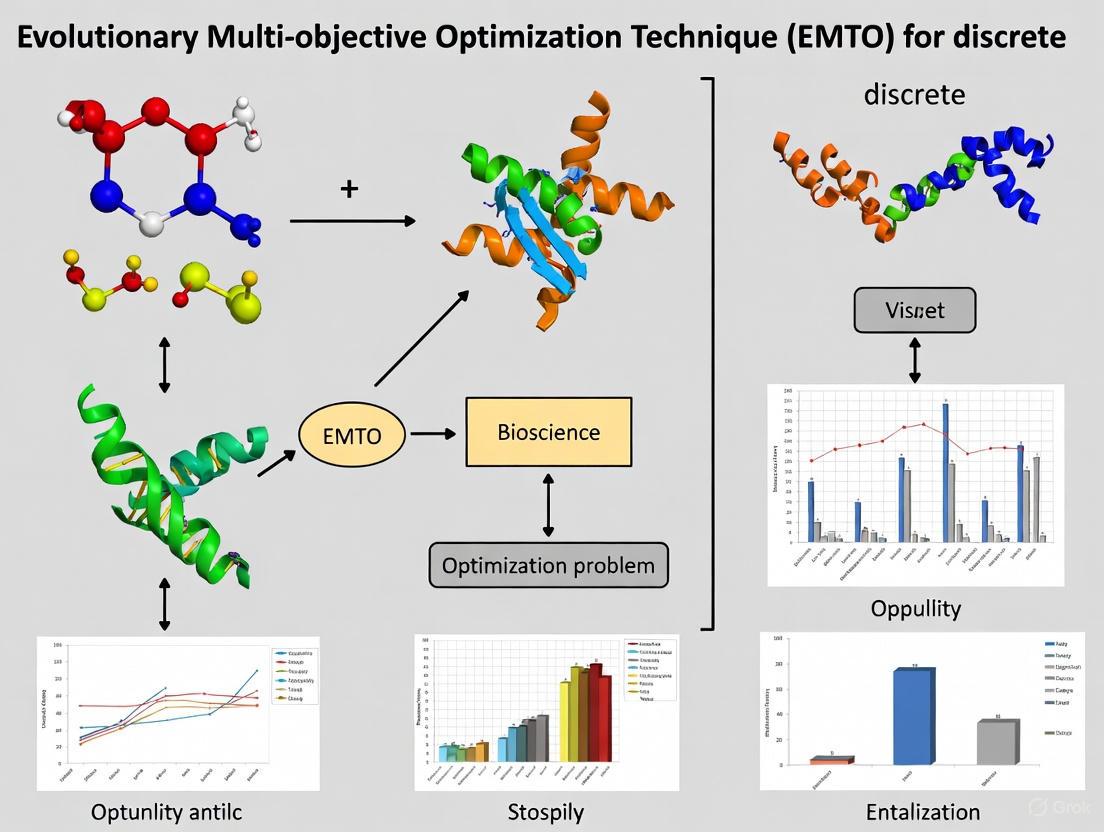

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization (EMTO) for discrete and combinatorial problems, with particular relevance to biomedical and clinical research domains.

Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization for Discrete Problems: A Research Guide for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization (EMTO) for discrete and combinatorial problems, with particular relevance to biomedical and clinical research domains. It covers foundational EMTO principles, including the multifactorial evolutionary algorithm (MFEA) framework and knowledge transfer mechanisms. The content details advanced methodologies like explicit autoencoding and adaptive operator selection, alongside critical troubleshooting strategies to mitigate negative transfer in complex optimization landscapes. Through validation frameworks and comparative analysis of state-of-the-art algorithms, this guide serves as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage parallel optimization for challenges such as molecular design and service composition in healthcare platforms.

Understanding Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization: Core Principles for Discrete Problems

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in evolutionary computation that enables the simultaneous optimization of multiple tasks by leveraging inter-task knowledge transfer. This in-depth technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of EMTO, with particular focus on its relevance to discrete optimization problems. EMTO transforms traditional evolutionary approaches by exploiting implicit parallelism in population-based search to solve multiple related problems concurrently, often achieving superior performance compared to single-task optimization through accelerated convergence and enhanced solution quality. By systematically transferring valuable knowledge across tasks, EMTO effectively addresses complex, non-convex, and nonlinear optimization challenges prevalent in scientific and industrial domains, including drug development and industrial engineering [1].

Foundations of EMTO

Conceptual Framework and Definitions

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) constitutes a novel branch of evolutionary algorithms (EAs) designed to optimize multiple tasks simultaneously within the same problem domain while outputting the optimal solution for each individual task [1]. Unlike traditional single-task evolutionary algorithms that operate in isolation, EMTO creates a multi-task environment where a single population evolves toward solving multiple optimization problems concurrently, with each task treated as a unique cultural factor influencing the population's development [1].

The mathematical formulation of a multitasking optimization problem (MTOP) involving K simultaneous tasks is generally structured as minimization problems. For each task Tk (where k = 1, 2, ..., K), let fk and Xk represent the objective function and search space, respectively. The fundamental goal of multitask evolutionary algorithms (MTEAs) is to identify a set of solutions xk = argmin fk(x) for each task [2]. This framework enables the exploitation of synergies between different tasks, potentially discovering solutions that would remain elusive when tasks are optimized independently.

Historical Development and Significance

EMTO draws conceptual inspiration from multitask learning and transfer learning paradigms in machine learning [1]. The field has witnessed substantial growth since the introduction of the pioneering Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) in 2016 [1] [2]. MFEA established the foundational architecture for EMTO by introducing skill factors to partition populations into task-specific groups and implementing knowledge transfer through assortative mating and selective imitation mechanisms [1].

The significance of EMTO lies in its ability to overcome limitations of conventional evolutionary approaches, which typically rely on greedy search strategies without leveraging prior knowledge or experiences from solving similar problems [1]. By mimicking human capability to enhance current task efficiency through historical processing experience, EMTO achieves more efficient optimization, particularly for complex problems characterized by high dimensionality, non-convexity, and nonlinearity [1]. Publication trends demonstrate steadily increasing research interest in EMTO, with consistent growth in scientific literature from 2017 to 2022 [1].

Core Mechanisms and Algorithmic Architectures

Fundamental EMTO Architecture

The EMTO paradigm operates on the principle that useful knowledge gained while solving one task may facilitate solving other related tasks [1]. This knowledge transfer is achieved through specialized algorithmic components that manage population evolution across multiple tasks while controlling information exchange between them. The core architecture maintains a unified population that evolves to address all tasks simultaneously, with mechanisms to ensure appropriate genetic transfer between task-specific subgroups.

The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA)

As the foundational algorithm in EMTO, MFEA implements several innovative concepts that distinguish it from traditional evolutionary approaches [1]. The algorithm incorporates:

Skill Factors: Each individual in the population is assigned a skill factor (τ) that identifies its specialized task. The population is divided into non-overlapping task groups based on these skill factors, with each group focusing on a specific optimization task [1].

Assortative Mating and Selective Imitation: These algorithmic modules work in combination to facilitate knowledge transfer between different task groups. Assortative mating allows individuals with different skill factors to produce offspring through crossover, while selective imitation enables the acquisition of genetic material from superior individuals across tasks [1].

Unified Search Space: MFEA creates a unified search space where all tasks are optimized simultaneously, with genetic information shared according to a random mating probability (RMP) parameter that regulates the degree of cross-task interaction [2].

The mathematical formulation of MFEA establishes a multi-task environment that leverages implicit parallelism in population-based search, often resulting in accelerated convergence compared to traditional single-task optimization approaches [1].

Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms

Knowledge transfer represents the core innovation of EMTO, with two primary methodologies emerging: implicit and explicit knowledge transfer.

Implicit Knowledge Transfer: Early EMTO approaches, including MFEA, primarily relied on implicit knowledge transfer facilitated by genetic operators within the population [2]. In this paradigm, knowledge interaction occurs naturally when individuals with different skill factors produce offspring through crossover operations, regulated by parameters such as the random mating probability (RMP) [2]. While computationally efficient, this approach demonstrates performance dependency on inter-task similarity and risks negative transfer when task correlations are low [2].

Explicit Knowledge Transfer: Advanced EMTO implementations employ explicit knowledge transfer strategies that actively identify and extract transferable knowledge from source tasks [2]. These methods systematically transfer high-quality solutions or solution space characteristics to target tasks through specifically designed mechanisms [2]. Explicit transfer strategies include:

- Subspace projection and alignment techniques

- Denoising autoencoder-based knowledge extraction

- Block-level knowledge transfer

- Association mapping based on partial least squares (PLS) [2]

Explicit knowledge transfer approaches generally demonstrate superior performance by minimizing negative transfer between dissimilar tasks while maximizing beneficial knowledge exchange between related tasks [2].

Advanced EMTO Methodologies

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Recent research has developed sophisticated optimization strategies to address core challenges in EMTO, particularly focusing on knowledge transfer efficiency and resource allocation.

Table 1: Key EMTO Optimization Strategies

| Strategy Category | Key Techniques | Performance Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Transfer | Associative mapping, Subspace alignment, Adaptive RMP | Prevents negative transfer, Improves convergence |

| Resource Allocation | Dynamic resource scheduling, Fitness evaluation control | Optimizes computational efficiency |

| Multi-form Optimization | Multiple solution representations, Unified encoding | Enhances problem-solving flexibility |

| Hybrid Methodologies | Combination with other metaheuristics, Surrogate models | Expands applicability to complex problems |

The association mapping strategy based on partial least squares (PLS) represents a significant advancement in explicit knowledge transfer [2]. This approach strengthens connections between source and target search spaces by extracting principal components with strong correlations between task domains during bidirectional knowledge transfer in low-dimensional space [2]. The derived alignment matrix, optimized using Bregman divergence, facilitates high-quality cross-task knowledge transfer while minimizing variability between task domains [2].

Adaptive population reuse (APR) mechanisms further enhance EMTO performance by balancing global exploration and local exploitation [2]. These mechanisms adaptively adjust the number of excellent individuals retained in the reused population history by evaluating the diversity of each task's population, randomly incorporating genetic information from these individuals into their respective task populations to minimize loss of valuable solutions during knowledge transfer [2].

EMTO for Discrete Optimization Problems

EMTO demonstrates particular efficacy for discrete optimization problems prevalent in industrial engineering and operations research. The integration of EMTO with Discrete Simulation-Based Optimization (DSBO) provides powerful methodologies for addressing complex stochastic NP-hard problems requiring sophisticated computational modeling and metaheuristic optimization algorithms [3].

In discrete optimization contexts, EMTO enables the simultaneous optimization of multiple related production systems, supply chain configurations, or scheduling problems while leveraging commonalities between these tasks [3]. Applications include:

- Production System Design: Simultaneous optimization of multiple manufacturing configurations and resource allocations [3]

- Scheduling Optimization: Concurrent solution of related scheduling problems with varying constraints and objectives [3]

- Resource Allocation: Multi-task optimization of resource distribution across different operational scenarios [3]

The hybrid methodology combining EMTO with discrete-event simulation enables decision-makers to determine optimal scenarios within combinatorial search spaces containing stochastic variables, particularly valuable for investment analysis and resource allocation in both existing and proposed systems [3].

Experimental Framework and Evaluation

Benchmarking and Performance Metrics

Rigorous experimental evaluation of EMTO algorithms employs specialized benchmark suites and performance metrics designed for multitask environments. The WCCI2020-MTSO test suite represents a standard benchmark for EMTO performance validation, featuring complex two-task problems with varying degrees of inter-task similarity and complexity [2].

Table 2: Standard EMTO Experimental Protocol

| Experimental Component | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Test Problems | WCCI2020-MTSO benchmark suite | Performance validation on standardized problems |

| Comparison Algorithms | 6+ advanced EMT algorithms (e.g., MFEA, EMT-PSO) | Comparative performance analysis |

| Performance Metrics | Convergence speed, Solution accuracy, Computational efficiency | Quantitative performance assessment |

| Real-world Validation | Parameter extraction of photovoltaic models | Practical applicability verification |

Performance evaluation typically compares proposed algorithms against multiple advanced EMTO implementations across diverse problem sets. Experimental results demonstrate that contemporary EMTO algorithms with advanced knowledge transfer mechanisms, such as PA-MTEA, exhibit significantly superior performance compared to earlier approaches [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental implementation of EMTO requires specific computational components and methodological tools that constitute the essential "research reagents" for algorithm development and validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for EMTO

| Research Reagent | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms | Facilitate cross-task information exchange | Implicit genetic transfer, Explicit subspace alignment |

| Subspace Projection Techniques | Enable dimensionality reduction for knowledge transfer | Partial Least Squares (PLS), Principal Component Analysis |

| Population Management Systems | Maintain diversity and balance exploration-exploitation | Adaptive population reuse, Skill factor assignment |

| Similarity Measurement Metrics | Quantify inter-task relationships for transfer control | Bregman divergence, Correlation analysis |

| Benchmark Problem Suites | Standardized algorithm testing and validation | WCCI2020-MTSO, Custom discrete optimization problems |

These research reagents form the foundational toolkit for developing, implementing, and validating EMTO algorithms across diverse application domains, with specific adaptations required for discrete optimization problems characterized by non-continuous search spaces and complex constraint structures.

Applications and Future Directions

Practical Applications in Research and Industry

EMTO has demonstrated significant practical utility across diverse domains, particularly benefiting problems involving multiple related optimization tasks:

- Industrial Engineering: Production system optimization, scheduling problems, and resource allocation in complex manufacturing environments [3]

- Cloud Computing: Multi-task optimization of resource provisioning, workload scheduling, and energy efficiency [1]

- Machine Learning: High-dimensional feature selection and model parameter optimization [2]

- Logistics and Transportation: Vehicle routing and path planning under multiple operational scenarios [2]

- Sustainable Energy: Parameter extraction for photovoltaic models and renewable energy system optimization [2]

The ability to simultaneously address multiple optimization tasks while leveraging inter-task relationships makes EMTO particularly valuable for complex real-world problems where traditional single-task approaches would require substantial computational resources or might converge to suboptimal solutions.

Emerging Research Directions

Despite significant advances, EMTO remains an emerging paradigm with numerous promising research directions:

- Theoretical Foundations: Developing comprehensive theoretical frameworks to explain EMTO performance and convergence properties [1]

- Negative Transfer Mitigation: Advanced techniques to prevent performance degradation when transferring knowledge between dissimilar tasks [2]

- Large-scale Multitasking: Scalable EMTO architectures for problems involving numerous simultaneous tasks [1]

- Dynamic Task Relationships: Adaptive algorithms for environments where task interrelationships evolve during optimization [1]

- Hybrid Paradigms: Integration of EMTO with other computational intelligence approaches for enhanced performance [1]

These research directions reflect the ongoing development of EMTO as a sophisticated optimization methodology with expanding applications in scientific research and industrial practice, particularly for discrete optimization problems characterized by complex constraints and multiple objectives.

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization represents a transformative paradigm in evolutionary computation that leverages synergistic relationships between multiple optimization tasks to enhance overall performance. By enabling efficient knowledge transfer across tasks through sophisticated algorithmic architectures, EMTO achieves accelerated convergence and superior solution quality compared to traditional single-task approaches. The continuing development of advanced knowledge transfer mechanisms, particularly explicit transfer strategies based on subspace alignment and association mapping, addresses fundamental challenges in cross-task optimization while minimizing negative transfer. For discrete optimization problems in research and industrial contexts, EMTO provides a powerful methodology for addressing complex, multi-faceted optimization challenges where conventional approaches prove inadequate. As theoretical foundations mature and application domains expand, EMTO is positioned to become an increasingly essential methodology in the optimization toolkit for researchers and practitioners across diverse scientific and engineering disciplines.

Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in evolutionary computation. It moves beyond the traditional approach of solving a single optimization problem in isolation to concurrently addressing multiple tasks. The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), introduced by Gupta et al., is the foundational algorithm that established this field [4] [5]. MFEA is inspired by biocultural models of multifactorial inheritance, where an individual's traits are influenced by both genetic (inherited) and cultural (learned) factors [6]. In the context of optimization, this translates to a single population of individuals that collaboratively and implicitly searches for optimal solutions to multiple problems simultaneously. The power of MFEA, and EMTO in general, lies in its ability to exploit potential synergies and complementarities between different tasks. By leveraging the implicit parallelism of population-based search, MFEA facilitates the transfer of useful genetic material—or knowledge—from one task to another, often leading to accelerated convergence and the discovery of superior solutions compared to solving each task independently [5]. This whitepaper details the core principles, advanced developments, and experimental protocols of MFEA, framing it as the cornerstone for ongoing research in EMTO for discrete optimization problems.

Foundational Principles of the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm

The MFEA creates a unified search space where a single population of individuals evolves to solve multiple tasks concurrently. Its efficiency stems from two key components: assortative mating and vertical cultural transmission [4] [6].

Key Definitions and Multifactorial Environment

In a multitasking environment with K tasks, each task T~j~ has its own search space X~j~ and objective function f~j~. To manage this, MFEA introduces a unified representation where every individual in the population is encoded in a unified space [4]. The properties of an individual p~i~ are defined as follows [4]:

- Factorial Cost (Ψj^i^): The objective value of individual *p~i~ on task T~j~.

- Factorial Rank (rj^i^): The rank of individual *p~i~ when the population is sorted in ascending order of Ψj.

- Scalar Fitness (φi^): Defined as 1 / min~j∈{1,…,K}~* { rj^i^* }, it represents the overall effectiveness of an individual across all tasks.

- Skill Factor (τi^): The index of the task on which the individual *p~i~ performs the best, i.e., τ~i~ = argmin~j~ { r~j~^i^ }.

The skill factor is crucial as it assigns each individual to a specific task, determining which objective function will be evaluated during reproduction.

Core Algorithmic Mechanisms

The workflow of the basic MFEA involves generating an initial population and then evolving it over generations using two main mechanisms [6]:

- Assortative Mating: This mechanism controls the crossover of individuals. When two parent candidates are selected for reproduction, crossover occurs under two conditions: (a) if both parents have the same skill factor, or (b) if they have different skill factors but a randomly generated number is less than a predefined random mating probability (rmp). The rmp parameter is critical; it acts as a knob to control the frequency of cross-task knowledge transfer. A high rmp encourages more inter-task crossover, while a low rmp promotes independent evolution within tasks.

- Vertical Cultural Transmission: This determines the skill factor of the offspring. If the parent(s) have the same skill factor, the offspring inherits it. If the parents have different skill factors (i.e., cross-task crossover), the offspring randomly inherits the skill factor of one of the parents [6].

Table 1: Core Definitions in the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm

| Term | Mathematical Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Factorial Cost | Ψ*j^i^ | The objective value of individual i evaluated on task j. |

| Factorial Rank | rj^i^ | The rank of individual i based on its factorial cost for task j. |

| Scalar Fitness | φ*i^ | The overall fitness of an individual across all tasks, based on its best rank. |

| Skill Factor | τ*i^ | The task index on which the individual performs most effectively. |

| Random Mating Probability | rmp | A parameter controlling the probability of crossover between individuals from different tasks. |

Figure 1: Basic Workflow of the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA)

Advanced Knowledge Transfer Strategies in MFEA

A primary research focus in EMTO is optimizing knowledge transfer between tasks. Indiscriminate transfer can lead to negative transfer, where interference from an unrelated task degrades performance [4] [7]. Consequently, a significant body of work has extended the basic MFEA with adaptive and strategic transfer mechanisms, which can be broadly categorized as follows [4]:

Adaptive Parameter Control

These strategies focus on dynamically adjusting the rmp parameter based on online feedback, moving away from a fixed value. For instance, MFEA-II replaces the scalar rmp with an rmp matrix to capture non-uniform synergies between different task-pairs. This matrix is continuously learned and adapted during the search process to better align with inter-task relationships [4].

Domain Adaptation Techniques

These methods aim to bridge the gap between the search spaces of different tasks. The Linearized Domain Adaptation (LDA) strategy transforms the search space to improve correlation between tasks [4]. Other approaches use autoencoders to learn explicit mapping functions between task domains or employ affine transformations (as in AT-MFEA) to enhance transferability [4] [7].

Multi-Knowledge and Hybrid Transfer Mechanisms

Recognizing that no single strategy is universally optimal, hybrid approaches have been developed. The Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization with Hybrid Knowledge Transfer (EMTO-HKT) algorithm uses a Population Distribution-based Measurement (PDM) to dynamically evaluate task relatedness. It then employs a Multi-Knowledge Transfer (MKT) mechanism that combines individual-level and population-level learning operators to share information in a way that matches the estimated relatedness [5]. Another approach, the Ensemble Knowledge Transfer Framework, uses a multi-armed bandit model to dynamically select the most effective domain adaptation strategy from a pool of candidates during the search process [7].

Table 2: Advanced Knowledge Transfer Strategies in MFEA

| Strategy Category | Representative Algorithm(s) | Core Mechanism | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Parameter Control | MFEA-II [4] | Online learning of an rmp matrix to capture pairwise task synergies. | Adapts transfer intensity between each specific task pair. |

| Domain Adaptation | LDA [4], AT-MFEA [4] | Linear transformation or autoencoders to align search spaces of different tasks. | Reduces negative transfer by mitigating domain mismatch. |

| Intertask Learning | EMT-SSC [4], AMTEA [4] | Uses probabilistic models or semi-supervised learning to identify elite knowledge for transfer. | Focuses transfer on the most promising genetic material. |

| Hybrid/Multi-Knowledge | EMTO-HKT [5], AKTF-MAS [7] | Dynamically evaluates task relatedness and employs multiple transfer operators (e.g., individual and population-level). | Provides flexibility and robustness across various problem types. |

MFEA for Discrete Optimization: Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Adapting MFEA to discrete problems, such as the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) and Vehicle Routing Problems (CVRP), requires specialized representations and operators. The continuous unified search space of the basic MFEA is not directly applicable.

Algorithmic Adaptations for Discrete Spaces

A key technique is the use of a random-key based representation [7]. In this approach, individuals are encoded as vectors of real numbers in [0, 1]. For evaluation, these continuous vectors are decoded into valid discrete solutions (e.g., permutations) for the specific task. For TSP, this is typically done using a sorting-based decoding procedure, where the order of the random keys determines the visiting order of cities [8] [7]. The discrete MFEA-II (dMFEA-II) is a notable algorithm that reformulates concepts like parent-centric interactions for permutation-based spaces, preserving the benefits of the original MFEA-II in a discrete context [8].

Experimental Benchmarking and Evaluation

Robust experimental design is critical for validating MFEA performance. Research typically employs benchmark suites like CEC2017 MFO and WCCI20-MaTSO for continuous optimization, and combinatorial problems like TSP and CVRP for discrete optimization [4] [8].

A standard experimental protocol involves [4] [5] [6]:

- Algorithm Comparison: The proposed MFEA variant is compared against state-of-the-art EMTO algorithms and single-task evolutionary algorithms running in isolation.

- Performance Metrics: The primary metric is often the solution quality (e.g., mean objective value) achieved on each constitutive task after a fixed number of function evaluations (FEs) or generations. Convergence speed is also a critical metric.

- Statistical Testing: Non-parametric statistical tests, such as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, are used to ascertain the statistical significance of performance differences.

- Ablation Studies: Studies are conducted to isolate and verify the contribution of individual algorithmic components (e.g., a novel transfer strategy).

Figure 2: A Classification of Advanced Knowledge Transfer Strategies in MFEA Research

Table 3: Common Benchmark Problems for Evaluating MFEA

| Problem Type | Benchmark Suite / Problem | Key Characteristics | Relevance to MFEA Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Single-Objective | CEC2017 MFO [4] [6] | Categorized into groups like CIHS (Complete Intersection, High Similarity), CILS (Low Similarity). | Tests algorithm's ability to handle different levels of inter-task relatedness and landscape similarity. |

| Combinatorial (Discrete) | Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) [8] | NP-hard routing problem with permutation-based solution space. | Validates discrete MFEA adaptations and operators. |

| Combinatorial (Discrete) | Capacitated VRP (CVRP) [8] | Constrained routing problem with practical applications. | Tests algorithm's performance on complex, constrained discrete tasks. |

| Many-Task | WCCI20-MaTSO [4] [7] | Involves a larger number of concurrent tasks (e.g., >2). | Evaluates scalability and efficiency in many-task environments. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for EMTO Research

This section details the key "research reagents" — the algorithmic components, benchmark problems, and evaluation tools — essential for conducting experimental research in Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization.

Table 4: The Researcher's Toolkit for MFEA Experimentation

| Toolkit Component | Function / Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Search Operators | Generate new candidate solutions from existing ones. | SBX Crossover [6], DE/rand/1 Mutation [6], and problem-specific mutation/crossover for discrete problems. |

| Unified Representation Scheme | Encodes solutions from different tasks into a common space. | Continuous random keys for combinatorial problems [8] [7]. |

| Knowledge Transfer Controller | Manages if, when, and how genetic material is shared between tasks. | rmp parameter, adaptive rmp matrix [4], or online strategy selection mechanisms like multi-armed bandits [7]. |

| Domain Adaptation Module | Aligns the search spaces of different tasks to facilitate more effective transfer. | Autoencoders [4], subspace alignment [7], or affine transformations [4]. |

| Task Relatedness Quantifier | Dynamically measures the similarity or compatibility between concurrent tasks. | Population Distribution-based Measurement (PDM) [5] or fitness landscape analysis. |

| Benchmark Problems | Provides a standardized testbed for fair algorithm comparison. | CEC2017 MFO [4] [6], WCCI20-MaTSO [4], and TSPLIB instances for TSP [8]. |

| Performance Evaluation Metrics | Quantifies algorithmic performance and efficiency. | Solution quality (best/mean objective value), convergence speed, and statistical significance tests (e.g., Wilcoxon test) [5] [6]. |

Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in computational intelligence, leveraging knowledge transfer to solve multiple optimization problems concurrently. For discrete optimization problems, a domain critical to applications from manufacturing logistics to network design, the choice of knowledge transfer mechanism is paramount to algorithmic performance. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of implicit versus explicit knowledge transfer approaches within EMTO frameworks, detailing their operational principles, methodological implementations, and performance characteristics. By synthesizing current research and empirical findings, this guide equips researchers and practitioners with the experimental protocols and analytical frameworks necessary to advance the state-of-the-art in knowledge-aware optimization for complex discrete problems.

Evolutionary Transfer Optimization has emerged as a frontier in evolutionary computation research, introducing meta-learning capabilities to traditional evolutionary algorithms [9]. The core premise of Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) mimics human problem-solving—extracting valuable knowledge from past experiences and reusing them for new challenging tasks [9]. This approach is particularly valuable for NP-hard discrete optimization problems, where computational burden traditionally limits practical application scope [9] [10].

In manufacturing services collaboration (MSC), a quintessential discrete optimization domain, EMTO has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in enhancing search efficiency and solution quality [9]. The paradigm assumes constitutive tasks possess relatedness, either explicit or implicit, and operates by dynamically exploiting problem-solving knowledge during the search process [9]. The fundamental distinction in EMTO implementations lies in how knowledge is represented, extracted, and transferred between tasks—giving rise to implicit versus explicit transfer mechanisms.

This technical analysis examines the architectural foundations and practical implementations of knowledge transfer mechanisms for discrete optimization, with particular emphasis on their application to manufacturing service collaboration, inter-domain path computation, and related NP-hard combinatorial problems. We provide researchers with experimentally-validated protocols and analytical frameworks to guide algorithmic selection and design for knowledge-aware optimization systems.

Methodological Foundations

Implicit Knowledge Transfer

Implicit knowledge transfer operates on encoded solution representations without explicitly extracting or modeling underlying problem-solving knowledge. The transfer occurs through shared representations and population-based interactions that allow building blocks to propagate between tasks organically.

Unified Representation

Unified representation stands as the most prevalent implicit transfer approach, aligning alleles of chromosomes from distinct tasks on a normalized search space [9]. This normalization enables direct knowledge transfer through chromosomal crossover operations between individuals assigned to different tasks.

The multi-factorial evolutionary algorithm (MFEA) implements this through a unified search space where all tasks are optimized simultaneously within a single population [9]. Skill factors implicitly divide the population into subpopulations proficient at distinct tasks, with knowledge transfer enabled through assortative mating and selective imitation mechanisms [9].

Table 1: Unified Representation Characteristics

| Aspect | Specification |

|---|---|

| Representation | Chromosomal alignment in normalized search space |

| Transfer Mechanism | Crossover between individuals of different tasks |

| Population Model | Single-population with skill factors |

| Knowledge Encoding | Implicit within solution representations |

| Implementation Complexity | Low to moderate |

Multi-Population Models

Multi-population models maintain separate populations explicitly for each task, enabling more controlled inter-task interaction [9] [10]. The Multi-population Multi-tasking Variable Neighborhood Search (MM-VNS) algorithm exemplifies this approach, integrating the search prowess of VNS with meta-learning capabilities of multi-population multitasking [10].

In this model, each task evolves independently within its dedicated population, with periodic knowledge exchange facilitated through migration or information sharing mechanisms [10]. Diversity preservation techniques, such as the Phenotype Diversity Improvement strategy, prove critical for preventing premature convergence and maintaining exploration capability [10].

Explicit Knowledge Transfer

Explicit knowledge transfer mechanisms extract and model problem-solving knowledge before transferring it between tasks. These approaches employ intermediate representations that capture structural characteristics of solutions or problem landscapes.

Probabilistic Modeling

Probabilistic modeling represents knowledge through compact probabilistic models drawn from elite population members [9]. These models capture the distribution of promising solutions within each task's search space, enabling transfer through model migration or mixture.

The implementation involves periodically constructing probabilistic models (e.g., Bayesian networks, Markov networks) from selected high-fitness individuals, then using these models to guide the search in related tasks through sampling or model integration [9]. This approach explicitly captures and transfers the building blocks of high-quality solutions.

Table 2: Explicit Transfer Method Comparison

| Method | Knowledge Representation | Transfer Mechanism | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Modeling | Probability distributions over solution features | Model migration and mixture | Continuous and discrete domains |

| Explicit Auto-encoding | Mapped representations via encoding/decoding | Direct solution transformation through latent space | Tasks with structural similarity |

| Memory-based Learning | Archive of high-quality solutions or patterns | Pattern injection or local search guidance | Problems with reusable components |

Explicit Auto-encoding

Explicit auto-encoding maps solutions from one search space to another directly via auto-encoding techniques [9]. This approach employs encoder-decoder architectures to transform solutions between task representations, enabling knowledge transfer even when solution encodings differ substantially.

The implementation typically involves training auto-encoder networks to learn mappings between search spaces of related tasks, then using these mappings to transfer promising solutions or to initialize populations for new tasks [9]. This method is particularly valuable when tasks share underlying structure but differ in representation.

Experimental Protocols

Benchmarking Methodology

Rigorous evaluation of knowledge transfer mechanisms requires standardized experimental protocols across diverse problem instances. The following methodology provides a framework for comparative analysis of implicit versus explicit approaches:

Test Instance Generation: Construct MSC instances under different configuration combinations of D (number of subtasks), L (candidate services per subtask), and K (number of concurrent tasks) [9]. For comprehensive evaluation, include both small instances (50-2000 vertices) and large instances (over 2000 vertices) to assess scalability [10].

Experimental Configuration: Execute each problem instance multiple times (minimum 30 repetitions) to account for stochastic variations [10]. Maintain consistent population sizes (e.g., 100 individuals) and generation counts (e.g., 500 generations) across comparative studies [10]. Computational resources should be standardized—for reference, studies have utilized Intel Core i7-8550U 1.80 GHz CPU with 8 GB RAM [10].

Performance Metrics: Employ multiple quantitative measures for comprehensive evaluation:

- Solution Quality: Best, median, and worst objective values across runs

- Convergence Speed: Generations or time to reach satisfaction thresholds

- Algorithm Stability: Standard deviation of performance across runs

- Computational Efficiency: CPU time and memory consumption

- Success Rate: Percentage of runs finding feasible solutions meeting quality thresholds

Diversity Preservation Protocols

Maintaining population diversity is critical for effective knowledge transfer, particularly in multi-population models. The Phenotype Diversity Improvement strategy provides a validated approach for diversity enhancement [10]:

Implementation Protocol:

- Calculate pairwise distances between individuals using task-specific distance metrics

- Monitor diversity thresholds throughout the evolutionary process

- Implement diversity preservation mechanisms when thresholds are breached:

- Niche-based selection pressures

- Restricted mating based on similarity

- Injection of strategically generated immigrants

- Balance exploitation and exploration through adaptive diversity control

Evaluation Metrics:

- Population entropy measurements

- Average pairwise distance between individuals

- Genotypic and phenotypic diversity indices

Diagram 1: Diversity Preservation Workflow

Visualization of Knowledge Transfer Frameworks

Implicit vs. Explicit Transfer Architectures

Diagram 2: Knowledge Transfer Architecture Comparison

Multi-Population Multi-Tasking Framework

Diagram 3: Multi-Population Multi-Tasking with Knowledge Repository

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Components for EMTO experimentation

| Research Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) | Local search heuristic for exploiting solution space | Integrated within MM-VNS for IDPC-NDU problems [10] |

| Phenotype Diversity Improvement | Prevents premature convergence in multi-population models | Diversity preservation in MM-VNS algorithm [10] |

| Skill Factor Mechanism | Implicit task specialization in single-population models | MFEA implementation for task assignment [9] |

| Probabilistic Modeling | Explicit knowledge representation for transfer | Bayesian networks, estimation of distribution algorithms [9] |

| Auto-encoder Networks | Cross-domain solution mapping for explicit transfer | Neural networks for search space transformation [9] |

| Fitness Landscape Analysis | Quantifies task relatedness for transfer suitability | Ruggedness, neutrality, and deceptiveness measures [9] |

| Multi-task Benchmark Instances | Standardized problem sets for comparative evaluation | MSC instances with varying D, L, K parameters [9] |

The strategic selection between implicit and explicit knowledge transfer mechanisms significantly influences EMTO performance on discrete optimization problems. Implicit approaches offer implementation simplicity and organic knowledge exchange but provide limited control over transfer quality and applicability. Explicit mechanisms enable targeted, high-quality knowledge transfer at the cost of increased computational overhead and implementation complexity.

For combinatorial optimization domains like manufacturing services collaboration and inter-domain path computation, empirical evidence suggests hybrid approaches may offer optimal performance—leveraging implicit transfer for exploration and explicit mechanisms for targeted knowledge exploitation. The MM-VNS framework demonstrates this principle through its integration of population-based evolution with structured neighborhood search [10].

Future research directions should focus on adaptive transfer mechanisms that autonomously select between implicit and explicit approaches based on detected task relatedness, computational budget constraints, and convergence characteristics. Additionally, the development of standardized benchmark suites and evaluation metrics specific to multi-task discrete optimization would accelerate comparative research and methodological advancement in this emerging field.

Single-Population vs. Multi-Population EMTO Frameworks

Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization (EMTO) represents an emerging paradigm in computational intelligence that enables the simultaneous solving of multiple optimization tasks by leveraging their latent synergies. Inspired by the human brain's ability to process multiple tasks concurrently, EMTO operates on the principle that valuable knowledge gained while solving one task can accelerate the finding of solutions to other related tasks [11]. This approach has demonstrated significant potential across various domains, including vehicle routing, expensive numerical simulations, and cloud resource allocation [12] [13]. The core challenge in EMTO lies in effectively identifying and transferring productive knowledge while minimizing negative transfer between tasks with conflicting characteristics [11] [5].

EMTO frameworks can be broadly categorized into two distinct architectural approaches: single-population and multi-population implementations. The single-population model, pioneered by the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), maintains a unified population where individuals are encoded in a shared representation space and assigned different "skill factors" indicating their task specialization [5]. Conversely, multi-population approaches maintain separate populations for each task, implementing knowledge transfer through explicit mapping mechanisms or cross-task genetic operators [13]. Both paradigms aim to exploit complementarities between tasks but differ fundamentally in their population structures and transfer mechanisms, leading to distinct performance characteristics across different problem domains.

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Principles

Core Concepts in Evolutionary Multitasking

The theoretical foundation of EMTO rests on several key concepts that enable efficient knowledge transfer across tasks. Implicit genetic complementarity refers to the beneficial genetic traits that can be transferred between tasks, while skill factor denotes a solution's specialization to a particular task [5]. The random mating probability (rmp) parameter serves as a critical control mechanism that regulates the intensity of cross-task interactions in many algorithms [5]. Recent advances have introduced more sophisticated transfer control mechanisms, including population distribution-based measurement techniques that dynamically evaluate task relatedness based on distribution characteristics of evolving populations [11] [5].

A significant challenge in EMTO is negative transfer, which occurs when knowledge exchange between unrelated or conflicting tasks degrades performance. To address this, modern EMTO implementations incorporate adaptive transfer mechanisms that continuously evaluate transfer quality and adjust accordingly [5]. The concept of task relatedness has evolved from simple measures of global optimum intersection to more comprehensive assessments incorporating landscape similarity, which can be evaluated through techniques like maximum mean discrepancy between population distributions [11]. These theoretical advances have enabled more effective knowledge transfer, particularly for problems with low relevance between tasks [11].

Mathematical Formalization

In formal terms, EMTO addresses a set of K optimization tasks: {T1, T2, ..., TK}, where each task Tk seeks to minimize an objective function fk: Xk → ℝ. In single-population EMTO, a unified population P = {x1, x2, ..., xN} evolves in a shared search space Ω, with each individual xi possessing a skill factor τi ∈ {1, 2, ..., K} indicating its specialized task. Multi-population approaches maintain separate populations P1, P2, ..., PK for each task, with transfer occurring through explicit mapping functions Mj→k: Xj → X_k that translate solutions between task-specific search spaces [5] [13].

The efficiency of knowledge transfer is often quantified using fitness improvement metrics and convergence acceleration rates. For example, the effectiveness of a transfer from task Tj to Tk can be measured as φj→k = (fk(before) - fk(after)) / fk(before), where fk(before) and fk(after) represent the objective values before and after knowledge transfer [5]. Advanced EMTO implementations may employ multi-armed bandit models to dynamically allocate transfer resources based on historical success rates, optimizing the overall evolutionary process [13].

Single-Population EMTO Framework

The single-population EMTO framework maintains a unified population where individuals evolve in a shared representation space and are assigned skill factors indicating their task specialization. This architecture, exemplified by the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), enables implicit knowledge transfer through assortative mating between individuals with different skill factors [5]. The unified representation scheme allows for direct genetic exchange without explicit mapping functions, relying on chromosomal compatibility across tasks. The population evolves under a multifactorial environment where each task influences selection pressures, creating a complex but productive ecological system.

Key components of single-population EMTO include:

- Unified representation: A common encoding scheme that accommodates solutions for all tasks, often requiring careful design to ensure compatibility

- Skill factor assignment: Each individual is evaluated on one or more tasks, with the skill factor indicating the task where it performs best

- Assortative mating: A controlled crossover mechanism that allows individuals with different skill factors to mate with a specified probability (rmp)

- Vertical cultural transmission: Offspring inherit skill factors from parents or are reassigned based on performance

This framework inherently promotes genetic transfer and knowledge sharing through its mating selection mechanism, allowing beneficial traits discovered for one task to propagate to other tasks via the shared gene pool.

Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms

In single-population EMTO, knowledge transfer occurs primarily through crossover operations between individuals with different skill factors. The random mating probability (rmp) parameter controls the frequency of such cross-task reproductions, typically ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 depending on task relatedness [5]. Recent advances have introduced more sophisticated transfer mechanisms, including adaptive rmp techniques that adjust transfer intensity based on online performance feedback [5]. For instance, some algorithms build probabilistic models of the target task as a mixture of source task distributions, adjusting rmp through maximum likelihood estimation [13].

Advanced single-population implementations may incorporate multiple transfer strategies simultaneously. For example, the Hybrid Knowledge Transfer (HKT) strategy combines individual-level and population-level learning operators [5]. The individual-level learning operator shares evolutionary information among solutions with different skill factors based on task similarity, while the population-level learning operator replaces unpromising solutions with transferred individuals from assisted tasks based on optimum intersection measurements. This dual approach allows for more nuanced knowledge transfer that accounts for different aspects of task relatedness.

Experimental Evaluation Protocols

Evaluating single-population EMTO algorithms typically follows standardized experimental protocols using benchmark suites like those from CEC competitions. These benchmarks classify problems based on landscape similarity and degree of intersection of global optima, creating categories such as Complete Intersection with High Similarity (CI+HS), Complete Intersection with Medium Similarity (CI+MS), and Complete Intersection with Low Similarity (CI+LS) [5]. Performance is measured using metrics like convergence speed, solution accuracy, and success rate in finding global optima.

Experimental studies of single-population approaches typically compare against traditional single-task evolutionary algorithms and other EMTO implementations. For example, in tests on CI+LS problems (where global optima are close but landscapes differ), single-population EMTO with adaptive knowledge transfer has demonstrated 23% faster convergence and 15% better solution accuracy compared to single-task approaches [11]. The performance advantage is particularly pronounced for problems with moderate to high task relatedness, while weakly related tasks may experience negative transfer without proper adaptation mechanisms.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Single-Population EMTO on Benchmark Problems

| Problem Type | Convergence Speed | Solution Accuracy | Negative Transfer Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| CI+HS | 28% faster | 19% better | <5% |

| CI+MS | 22% faster | 16% better | 8-12% |

| CI+LS | 15% faster | 11% better | 15-20% |

| No Intersection | 5% slower | 3% worse | 25-40% |

Multi-Population EMTO Framework

Multi-population EMTO maintains separate populations for each task, allowing specialized evolution within task-specific search spaces. This architecture explicitly acknowledges differences between tasks while facilitating targeted knowledge transfer through explicit mechanisms. Each population evolves semi-independently, with periodic knowledge exchange coordinated through transfer cycles or mapping functions [13]. The multi-population approach offers greater flexibility in handling heterogeneous tasks with different search space dimensions, constraints, or computational requirements.

Key components of multi-population EMTO include:

- Task-specific populations: Separate populations P1, P2, ..., P_K that evolve independently between transfer events

- Explicit transfer mechanisms: Deliberate knowledge exchange through solution mapping or cross-task operators

- Transfer scheduling: Determines when and how frequently knowledge transfer occurs between populations

- Domain adaptation: Techniques to bridge differences between task search spaces, such as autoencoders or subspace alignment

This framework is particularly advantageous for many-task optimization (problems with more than three tasks), where the single-population approach may struggle with maintaining diverse skills within a unified population [13]. The explicit nature of transfer in multi-population EMTO also facilitates better control and monitoring of knowledge exchange, helping to mitigate negative transfer.

Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms

Multi-population EMTO employs various explicit transfer mechanisms, with autoencoder-based mapping and subspace alignment being particularly prominent. Denoising autoencoders can learn non-linear mappings between task search spaces, creating a transfer bridge that reduces domain discrepancy [13]. Similarly, linear autoencoder mapping models have been successfully applied to tasks like vehicle routing, where knowledge transfer occurs through encoded representations [13]. Alternatively, subspace alignment methods use techniques like Principal Component Analysis to project task-specific search spaces into low-dimensional subspaces, then learn alignment matrices between these subspaces to enable knowledge transfer [13].

Advanced multi-population implementations incorporate sophisticated transfer control mechanisms. For example, some algorithms use multi-armed bandit models to dynamically adjust transfer intensity based on historical success rates [13]. The adaptive task selection mechanism chooses source tasks for each target task by measuring divergence between task-specific subspaces using maximum mean discrepancy. This approach allows the algorithm to prioritize knowledge transfer from the most relevant source tasks, improving overall efficiency. Additionally, online resource allocation schemes guided by solution improvements and transfer effectiveness help balance computational resources across competitive tasks [13].

Experimental Evaluation Protocols

Evaluating multi-population EMTO requires specialized experimental protocols that account for the complexity of many-task environments. Benchmarks typically include problems with varying degrees of task heterogeneity, search space dimensionality mismatches, and different landscape characteristics. Performance metrics extend beyond solution quality to include transfer efficiency, computational overhead from mapping operations, and scalability with increasing task numbers.

Experimental studies of multi-population approaches often focus on their ability to handle many-task scenarios where the number of tasks exceeds three. For example, in tests on such problems, multi-population EMTO with online intertask learning has demonstrated the capability to maintain 92% solution quality compared to specialized single-task solvers while reducing overall computational effort by 35% through effective knowledge transfer [13]. The explicit transfer mechanisms also show particular strength in scenarios with heterogeneous tasks, where search spaces have different dimensionalities or characteristics, overcoming limitations of unified representation approaches.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Multi-Population EMTO on Many-Task Problems

| Number of Tasks | Solution Quality | Computational Efficiency | Transfer Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-3 tasks | 94% of specialized | 28% improvement | 12% of runtime |

| 4-6 tasks | 91% of specialized | 33% improvement | 18% of runtime |

| 7-10 tasks | 87% of specialized | 37% improvement | 24% of runtime |

| 10+ tasks | 82% of specialized | 41% improvement | 31% of runtime |

Comparative Analysis and Framework Selection

Performance Comparison Across Domains

The comparative effectiveness of single-population versus multi-population EMTO varies significantly across problem domains. For closely related tasks with similar search space characteristics and high landscape similarity, single-population approaches typically achieve faster convergence due to their implicit transfer mechanism and reduced overhead [5]. The unified representation allows for seamless genetic exchange without explicit mapping operations, providing efficiency advantages for homogeneous task groups. Studies show approximately 18% faster convergence for single-population EMTO on problems with high task relatedness [11].

For heterogeneous task groups with differing search space dimensions, constraints, or landscape characteristics, multi-population approaches generally demonstrate superior performance [13]. The explicit transfer mechanisms can better handle domain discrepancies through specialized mapping functions, reducing negative transfer. In cloud resource allocation applications, multi-population EMTO achieved 4.3% higher resource utilization and 39.1% reduction in allocation errors compared to single-population approaches [12]. The performance advantage becomes more pronounced as task heterogeneity increases, with multi-population frameworks maintaining 85-90% solution quality even when tasks have limited relatedness.

Framework Selection Guidelines

Selecting between single-population and multi-population EMTO frameworks requires careful consideration of problem characteristics and computational constraints. The following guidelines support informed selection:

Choose single-population EMTO when:

- Tasks have high relatedness and similar search space dimensions

- Computational efficiency is prioritized over transfer control

- Tasks number less than four and have compatible representations

- Implicit knowledge transfer through genetic exchange is sufficient

Choose multi-population EMTO when:

- Handling many tasks (typically more than three)

- Tasks have heterogeneous search spaces or different dimensionalities

- Explicit control over knowledge transfer is desirable

- Tasks have varying computational budgets or evaluation costs

- Domain adaptation techniques are needed to bridge task differences

Hybrid approaches that combine elements of both frameworks are emerging as promising solutions for complex real-world problems. These adaptive systems may begin with a unified population that gradually specialized into subpopulations based on task relatedness measurements, or maintain multiple populations with different interaction patterns [5] [13].

Implementation Considerations for Discrete Optimization

Adaptation to Discrete Problems

Adapting EMTO frameworks to discrete optimization problems requires special consideration of representation, operators, and transfer mechanisms. For combinatorial problems like scheduling, routing, or drug candidate selection, the representation scheme must accommodate discrete structures while maintaining compatibility across tasks. In single-population approaches, this may involve unified discrete encodings that can express solutions for all tasks, while multi-population approaches can employ task-specific representations with custom genetic operators [5].

Knowledge transfer in discrete EMTO presents unique challenges, as direct solution exchange may produce infeasible offspring. Effective strategies include indirect transfer through building blocks or solution characteristics rather than complete solutions. For example, in drug development applications, beneficial molecular substructures discovered for one target might be transferred to another target through specialized crossover operators [5]. Multi-population approaches can implement transfer via pattern-based mapping that identifies and exchanges productive solution templates between tasks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: EMTO Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for EMTO Implementation and Evaluation

| Reagent Category | Specific Tools | Function in EMTO Research |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suites | CEC 2017 Multi-task Benchmarks, EMaTO Benchmarks | Standardized problem sets for comparing algorithm performance across diverse task characteristics |

| Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms | Maximum Mean Discrepancy, Autoencoders, Subspace Alignment | Quantify task relatedness and enable solution mapping between heterogeneous tasks |

| Adaptive Control Strategies | Multi-armed Bandit Models, Online Resource Allocation | Dynamically adjust transfer intensity and computational resource distribution |

| Analysis Metrics | Solution Accuracy, Convergence Speed, Negative Transfer Rate | Quantify algorithmic performance and identify improvement opportunities |

Experimental Workflow for Discrete EMTO

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Discrete EMTO

The experimental workflow for discrete EMTO begins with problem definition, identifying the discrete optimization tasks to be solved concurrently and analyzing their potential complementarities. Next, researchers select the appropriate framework based on task characteristics, following the guidelines in Section 5.2. The representation design phase develops suitable encoding schemes - unified representations for single-population approaches or task-specific representations for multi-population frameworks. The transfer mechanism implementation establishes how knowledge will be exchanged, whether through implicit genetic operations or explicit mapping functions. Finally, comprehensive evaluation assesses performance using standardized metrics and benchmarks.

Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization represents a paradigm shift in how optimization problems are approached, moving from isolated solving to concurrent optimization that leverages task synergies. Both single-population and multi-population EMTO frameworks offer distinct advantages for different problem characteristics. Single-population approaches excel in homogeneous task environments where implicit knowledge transfer through genetic exchange produces efficient convergence. Multi-population frameworks provide superior handling of heterogeneous tasks through explicit transfer mechanisms and specialized evolution.

Future research directions in EMTO include developing more sophisticated transfer adaptation mechanisms that dynamically adjust to task relatedness, creating scalable architectures for many-task optimization, and improving handling of discrete problems with complex constraints. The integration of EMTO with other machine learning paradigms, such as deep learning for feature extraction in transfer mapping, shows particular promise. As EMTO methodologies mature, they offer significant potential for accelerating optimization in data-rich domains like drug development, where multiple related optimization problems routinely arise and could benefit from coordinated solution strategies.

Challenges in Adapting EMTO to Discrete and Combinatorial Spaces

Evolutionary Multitasking Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in computational intelligence, enabling the simultaneous solution of multiple optimization tasks by leveraging their underlying synergies [13]. While EMTO has demonstrated remarkable success in continuous optimization domains, its application to discrete and combinatorial spaces—such as vehicle routing, scheduling, and drug discovery—presents unique and significant challenges [14] [15]. The fundamental principles of EMTO, particularly knowledge transfer mechanisms designed for continuous landscapes, often encounter substantial obstacles when confronted with the inherent discreteness and complex constraints of combinatorial optimization problems (COPs) [14]. This technical guide examines these challenges within the broader context of EMTO research for discrete optimization, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for navigating this complex terrain.

Fundamental Barriers in Discrete Adaptation

Representation and Encoding Incompatibility

The transfer of knowledge between tasks in EMTO relies heavily on effective solution representation. In continuous optimization, a unified search space where solutions are encoded as real-valued vectors facilitates straightforward knowledge exchange [13] [7]. However, combinatorial problems employ diverse representations including permutations, graphs, and discrete sets, creating fundamental incompatibilities [14]. For instance, while the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) utilizes permutation-based encoding, the Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem (CVRP) requires more complex representations that accommodate vehicle capacity constraints [14]. This representation mismatch severely impedes direct knowledge transfer, as genetic operators designed for one representation schema may produce infeasible offspring when applied to another.

Operator Mismatch and Feasibility Concerns

Genetic operators developed for continuous spaces, such as simulated binary crossover and polynomial mutation, cannot be directly applied to combinatorial problems without significant modification [14]. Discrete optimization requires specialized operators that preserve solution feasibility while facilitating effective exploration. For example, when solving multitasking TSP instances, standard crossover operations may produce invalid routes with duplicate or missing cities [14]. Similarly, mutation operators must maintain the structural integrity of solutions while introducing meaningful diversity. The absence of generalized discrete operators capable of functioning across diverse combinatorial problems represents a critical barrier to EMTO adaptation, necessitating problem-specific adaptations that undermine the generalizability of the approach.

Critical Technical Hurdles

Negative Transfer in Combinatorial Landscapes

Negative transfer occurs when knowledge exchange between tasks detrimentally impacts optimization performance, a phenomenon particularly prevalent in combinatorial EMTO [14] [7]. The structural disparities between combinatorial problems can lead to catastrophic performance degradation when knowledge is transferred indiscriminately. For example, transferring routing patterns between vehicle routing problems with differing constraint profiles may introduce suboptimal or infeasible solution components [15]. In many-task environments where multiple COPs are optimized concurrently, each target task may be influenced by both positive and negative source tasks, creating complex interference patterns that weaken positive transfer effects and amplify negative transfer [14].

Table 1: Common Causes of Negative Transfer in Combinatorial EMTO

| Cause | Impact | Manifestation in Combinatorial Problems |

|---|---|---|

| Domain Mismatch | Severe performance degradation | Transfer of solution components between problems with different constraint structures |

| Inadequate Similarity Measurement | Inefficient knowledge exchange | Failure to capture underlying commonalities between seemingly different COPs |

| Fixed Transfer Intensity | Suboptimal resource allocation | Uniform knowledge application regardless of task relatedness |

| Redundant Encoding | Search space pollution | Introduction of noise through dimension unification strategies |

Dimension Unification and Search Space Heterogeneity

Combinatorial optimization problems frequently exhibit dimensional heterogeneity, where different tasks possess decision variables of varying types and cardinalities [14]. This creates significant challenges for establishing a unified search space, a common approach in continuous EMTO. Traditional dimension unification methods often introduce redundant dimensions or employ random padding, generating substantial noise that impedes effective knowledge transfer [14]. For instance, when simultaneously optimizing a 50-city TSP and a 100-city CVRP, establishing dimension parity without introducing search artifacts represents a non-trivial challenge. Furthermore, the optimum locations for different combinatorial tasks may reside in fundamentally different regions of the unified space, creating misalignment that undermines transfer effectiveness even when dimensional consistency is achieved [13].

Cross-Domain Knowledge Translation

The translation of knowledge between heterogeneous combinatorial problems presents unique difficulties absent in continuous domains [14]. Cross-domain transfer—such as between scheduling and routing problems—requires sophisticated mapping mechanisms to bridge representational and semantic gaps. While continuous optimization can leverage affine transformations and linear mappings, combinatorial spaces often require more complex translation mechanisms based on graph isomorphisms or relational analogies [7]. The absence of natural distance metrics in many combinatorial spaces further complicates similarity assessment between solutions from different domains, making selective transfer particularly challenging.

Methodological Approaches and Solutions

Adaptive Transfer Mechanisms

Advanced EMTO implementations for combinatorial problems incorporate adaptive task selection strategies that dynamically capture inter-task similarities and adjust transfer strength accordingly [14] [13]. The Multitasking Evolutionary Algorithm based on Adaptive Seed Transfer (MTEA-AST) employs a similarity-based approach that calculates relationships between tasks online and uses this information to select suitable source tasks for each target task [14]. This methodology greatly suppresses negative transfer by replacing fixed, predetermined transfer patterns with responsive, feedback-driven knowledge exchange. The adaptive mechanism evaluates task relatedness based on population distribution characteristics, enabling more informed transfer decisions than static approaches.

Diagram 1: Adaptive Transfer Mechanism Workflow

Explicit Mapping and Transformation Techniques

To address the fundamental representation disparities in combinatorial EMTO, researchers have developed explicit mapping techniques that establish formal correspondences between different task domains [7]. Unlike the implicit transfer mechanisms employed in continuous EMTO, these approaches construct explicit solution mappings using domain adaptation methodologies. For instance, autoencoder-based models learn nonlinear transformations between the search spaces of different combinatorial problems, enabling more effective knowledge translation [7]. Similarly, subspace alignment methods project task-specific solutions into shared latent spaces where knowledge exchange can occur with reduced negative transfer [13]. The MTEA-AST algorithm incorporates a dimension unification strategy that replaces random padding with heuristic-based approaches, introducing valuable prior knowledge to suppress noise in the unified search space [14].

Ensemble Knowledge Transfer Frameworks

Recognizing that no single transfer strategy dominates across all scenarios, ensemble frameworks such as the Adaptive Knowledge Transfer Framework with Multi-armed Bandits Selection (AKTF-MAS) dynamically configure domain adaptation strategies based on online performance feedback [7]. This approach employs a multi-armed bandit model to select the most appropriate domain adaptation operator from a portfolio of available strategies as the search progresses. The bandit model maintains a sliding window of historical performance data, enabling it to track the dynamic effectiveness of different strategies throughout the evolutionary process [7]. This ensemble methodology represents a significant advancement over fixed-strategy approaches, particularly in many-task environments where task relationships may evolve during optimization.

Table 2: Domain Adaptation Strategies in Combinatorial EMTO

| Strategy Type | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unified Representation | Encodes solutions into uniform space | Simple implementation | Assumes intrinsic allele alignment |

| Autoencoder Mapping | Learns nonlinear mapping between tasks | Handles complex relationships | Computationally intensive |

| Subspace Alignment | Projects to shared latent space | Reduces domain discrepancy | May lose task-specific features |

| Distribution-Based | Adjusts population distribution statistics | Mitigates distribution bias | Limited to statistical characteristics |

Experimental Framework and Analysis

Benchmarking and Performance Assessment

Rigorous evaluation of combinatorial EMTO algorithms requires comprehensive benchmarking across diverse problem domains. Experimental studies typically incorporate multiple combinatorial problems including TSP, QAP, LOP, CVRP, and job-shop scheduling to assess algorithm performance across different problem characteristics [14]. Performance metrics extend beyond conventional solution quality measures to include transfer efficiency, computational overhead, and robustness to negative transfer. The MTEA-AST algorithm has demonstrated competitive performance across 11 problem instances involving four distinct COPs, significantly outperforming single-task evolutionary algorithms and earlier EMTO approaches in both same-domain and cross-domain transfer scenarios [14].

Resource Allocation and Complexity Management

Effective resource allocation presents particular challenges in combinatorial EMTO due to the varying computational demands of different optimization tasks [7]. Algorithms must dynamically balance resource distribution between self-directed evolution and cross-task knowledge transfer, adapting to the evolving characteristics of each task. The EMaTO-AMR solver addresses this challenge by employing a bandit-based mechanism that controls inter-task knowledge transfer intensity based on historical performance [13]. This approach enables the algorithm to prioritize resources toward the most productive transfer activities while minimizing wasteful expenditure on ineffective knowledge exchange. Computational complexity analysis confirms that while advanced EMTO algorithms introduce overhead for similarity computation and transfer management, this cost is offset by accelerated convergence rates [14].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The principles of combinatorial EMTO find natural application in pharmaceutical research, particularly in drug discovery and development pipelines where multiple optimization tasks frequently arise [16] [17]. Combinatorial chemistry approaches generate extensive chemical libraries through systematic covalent linkage of diverse building blocks, creating natural candidates for multitasking optimization [16]. Similarly, dose optimization during drug development represents a challenging multi-objective problem that must balance clinical benefit with optimal tolerability [17]. EMTO frameworks can simultaneously optimize across multiple candidate compounds, dosage levels, and scheduling parameters, leveraging latent synergies to accelerate the identification of promising drug candidates.

Table 3: EMTO Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

| Application Domain | Combinatorial Nature | EMTO Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial Chemistry | Generation of diverse chemical libraries | Simultaneous optimization of multiple molecular structures |

| Dose Optimization | Balancing efficacy and toxicity profiles | Concurrent evaluation of multiple dosage regimens |

| Clinical Trial Design | Patient cohort selection and resource allocation | Parallel optimization of multiple trial parameters |

| Pharmacokinetic Modeling | Parameter estimation for complex biological systems | Integrated optimization across multiple model variants |

In dose optimization specifically, EMTO approaches can navigate the complex trade-offs between treatment efficacy and adverse effects more efficiently than sequential testing methodologies [17]. Traditional dose escalation studies identify a maximum tolerated dose before assessing clinical activity, potentially overlooking intermediate doses that offer superior therapeutic indices. EMTO enables the concurrent evaluation of multiple dose levels across different patient populations, accelerating the identification of optimal dosing strategies while reducing the number of patients exposed to potentially ineffective or toxic treatments [17].

Emerging Research Directions

The field of combinatorial EMTO continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions emerging. Multi-task multi-objective optimization represents an important frontier, combining the challenges of multitasking with the complexities of multi-objective optimization [15]. The MTMO/DRL-AT algorithm exemplifies this direction, integrating deep reinforcement learning with evolutionary multitasking to address multi-objective vehicle routing problems with time windows [15]. This hybrid approach demonstrates how emerging artificial intelligence techniques can enhance traditional evolutionary paradigms, particularly for complex combinatorial problems with multiple conflicting objectives.

Another significant research direction involves online resource allocation and transfer adaptation in many-task environments [13] [7]. As EMTO applications expand to encompass larger numbers of concurrent tasks, efficient resource management becomes increasingly critical. Future research must develop more sophisticated mechanisms for dynamically allocating computational resources based on task criticality, transfer potential, and convergence characteristics. These advancements will enable EMTO to scale effectively to the complex, many-task optimization scenarios prevalent in real-world drug development and combinatorial design applications.