Evolutionary Multitasking Genetic Algorithms for High-Dimensional Feature Selection in Biomedical Research

This article explores the cutting-edge methodology of Evolutionary Multitasking (EMT) enhanced Genetic Algorithms (GAs) for feature selection, a critical preprocessing step in analyzing high-dimensional biomedical data.

Evolutionary Multitasking Genetic Algorithms for High-Dimensional Feature Selection in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the cutting-edge methodology of Evolutionary Multitasking (EMT) enhanced Genetic Algorithms (GAs) for feature selection, a critical preprocessing step in analyzing high-dimensional biomedical data. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination from foundational concepts to practical applications. The content covers the underlying principles of EMT and its synergy with GAs, details innovative algorithmic frameworks and their use in domains like cancer classification from microarray data, addresses key optimization challenges such as negative knowledge transfer, and validates the performance of these methods against state-of-the-art alternatives. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to leverage these powerful algorithms for enhancing model accuracy, interpretability, and efficiency in complex biomedical data analysis.

The Foundations of Evolutionary Multitasking and Genetic Algorithms for Feature Selection

In the fields of biomedical research and drug development, high-throughput technologies often generate data where the number of features (e.g., genes, proteins, biomarkers) vastly exceeds the number of samples. This scenario, known as high-dimensional data, presents a significant challenge referred to as the "curse of dimensionality" [1] [2]. The exponentially growing search space, increased computational complexity, and heightened risk of model overfitting are direct consequences of this phenomenon, making feature selection (FS) a critical preprocessing step in the analysis pipeline [1] [3].

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs), particularly multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (MOEAs), have emerged as powerful wrapper methods for feature selection due to their population-based global search capabilities [4]. However, traditional MOEAs often face limitations with high-dimensional datasets, including low search efficiency, premature convergence, and poor solution diversity [1]. To address these challenges, researchers have turned to Evolutionary Multitasking (EMT), a paradigm that optimizes multiple related tasks simultaneously by exploiting inter-task correlations and facilitating knowledge transfer [5]. This application note explores these advanced methodologies within the context of a broader thesis on multitasking genetic algorithms for feature selection, providing detailed protocols and analyses for researchers and scientists in biomedical domains.

Key Algorithms and Comparative Performance

Advanced Feature Selection Algorithms

Recent research has produced several innovative algorithms designed specifically to tackle high-dimensional feature selection. These can be broadly categorized into dimensionality reduction-based approaches, evolutionary multitasking methods, and hybrid AI-driven frameworks.

The DR-RPMODE algorithm employs a two-phase approach, beginning with fast dimensionality reduction (DR) using novel freezing and activation operators to remove irrelevant and redundant features [1]. Subsequently, the RPMODE phase continues the search on reduced datasets, incorporating redundant handling to filter duplicated solutions and preference handling to prioritize classification performance [1]. This algorithm demonstrates particular effectiveness on datasets with feature dimensions ranging from 166 to 24,482, showing improved performance as data dimensionality increases [1].

For evolutionary multitasking, the EMTRE method introduces a novel multi-task generation strategy based on feature weights evaluated by the Relief-F algorithm [5]. It defines a unique metric for task relevance, transforming optimal subtask selection into a solvable heaviest k-subgraph problem, and employs an enhanced knowledge transfer strategy using guiding vectors to improve search capability and convergence speed [5].

Hybrid approaches like TMGWO, ISSA, and BBPSO incorporate nature-inspired optimization techniques. TMGWO (Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimization) introduces a two-phase mutation strategy that enhances the balance between exploration and exploitation [2]. ISSA (Improved Salp Swarm Algorithm) incorporates adaptive inertia weights, elite salps, and local search techniques to boost convergence accuracy [2]. BBPSO (Binary Black Particle Swarm Optimization) streamlines the PSO framework through a velocity-free mechanism while preserving global search efficiency [2].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Feature Selection Algorithms on High-Dimensional Biomedical Datasets

| Algorithm | Core Mechanism | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantages | Tested Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR-RPMODE [1] | Fast dimensionality reduction + multi-objective differential evolution | Outperformed 7 comparison algorithms on most of 16 datasets | Superior scalability with increasing dimensionality; effective redundant solution filtering | 16 UCI datasets (166-24,482 features) |

| EMTRE [5] | Task relevance evaluation + guided knowledge transfer | Outperformed various state-of-the-art FS methods on 21 datasets | Optimal task crossover ratio (~0.25); enhanced convergence through task similarity | 21 high-dimensional datasets |

| TMGWO-SVM [2] | Two-phase mutation Grey Wolf Optimization + SVM | 96% accuracy (Breast Cancer dataset) | Balance between exploration and exploitation; uses only 4 features | Breast Cancer Wisconsin dataset |

| Boruta-LightGBM [3] | All-relevant feature selection + gradient boosting | 85.16% accuracy, 85.41% F1-score (Diabetes) | 54.96% reduction in training time; high feature interpretability | Pima Indian Diabetes Dataset |

| AIMEA [4] | Adaptive initialization + dynamic multitasking | Significantly better on most of 20 datasets per Wilcoxon's Test | Self-adaptive parameters; better convergence-diversity balance | 20 classification datasets |

Table 2: Statistical Test-Based Feature Selection for Breast Cancer Gene Expression Data

| Feature Selection Method | Classifier | Average Accuracy (%) | Key Findings | Data Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-test [6] | Naïve Bayes | Highest accuracy among tested combinations | Most informative genes identified from 24,188 total genes | 97 patients (46 cancer, 51 control) |

| t-test [6] | Adaboost | Reported | Integrated approach improves generalization | 70% training, 30% test, 1000 repetitions |

| t-test [6] | ANN | Reported | Feature selection increases learning effectiveness | Microarray gene expression data |

| Wilcoxon signed rank sum test [6] | KNN | Reported | Removing irrelevant features improves accuracy | Benchmark dataset from Kent Ridge Repository |

| Wilcoxon signed rank sum test [6] | Random Forest | Reported | Selecting pertinent features enhances classification |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Implementation of Evolutionary Multitasking for Feature Selection

The following protocol outlines the experimental procedure for implementing an evolutionary multitasking approach for high-dimensional feature selection, based on the EMTRE methodology [5].

3.1.1 Preprocessing and Initialization

- Begin with data normalization to prevent bias in feature weighting.

- Apply the Relief-F algorithm to evaluate feature weights and rank features by importance.

- Utilize the Algorithm with a Reservoir (A-Res) to sample feature selection subtasks from the original high-dimensional task.

- Define the average crossover ratio metric to evaluate relevance between different subtasks.

- Formulate optimal subtask selection as the heaviest k-subgraph problem and solve using branch and bound methods.

3.1.2 Multi-Task Optimization

- Initialize multiple subpopulations corresponding to different feature selection subtasks.

- Implement a knowledge transfer strategy based on guiding vectors to facilitate information sharing between related tasks.

- Employ a convergence factor that dynamically adapts throughout the optimization process to balance exploration and exploitation.

- Maintain a task crossover ratio of approximately 0.25, which has been experimentally determined as optimal [5].

- Continue optimization until convergence criteria are met, typically measured by stabilization of classification performance across generations.

3.1.3 Validation and Evaluation

- Apply k-fold cross-validation (typically k=10) to assess generalization performance.

- Evaluate results using multiple metrics: accuracy, F1-score, area under the curve (AUC).

- Compare performance against baseline classifiers without feature selection.

- Perform SHAP analysis or similar interpretability techniques to validate feature importance.

Protocol: Dimensionality Reduction with DR-RPMODE

This protocol details the implementation of the DR-RPMODE algorithm, which combines fast dimensionality reduction with multi-objective differential evolution [1].

3.2.1 Dimensionality Reduction Phase

- Apply the freezing operator to identify and remove irrelevant features based on their correlation with classification outcomes.

- Implement the activation operator to refine the feature subset by re-selecting features that may contribute to classification performance.

- Set the maximum feature reduction ratio (FRmax) to 0.3, which has been shown to yield the highest Hypervolume (HV) scores across most datasets [1].

- Validate that the reduced feature set maintains essential information for classification.

3.2.2 Multi-Objective Optimization Phase

- Initialize population with solutions representing feature subsets.

- Apply differential evolution framework with modified mutation and crossover operations.

- Implement redundant handling to identify and filter duplicated solutions, maintaining population diversity.

- Incorporate preference handling to prioritize solutions with better classification performance, using Macro F1 score as a constraint.

- Optimize the two conflicting objectives simultaneously: minimizing number of features and maximizing classification performance.

3.2.3 Performance Evaluation

- Compare obtained solutions using Hypervolume (HV) and Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) metrics.

- Validate on testing sets not used during the optimization process.

- Compare convergence and diversity against state-of-the-art MOEAs like NSGA-II, MOEA/D.

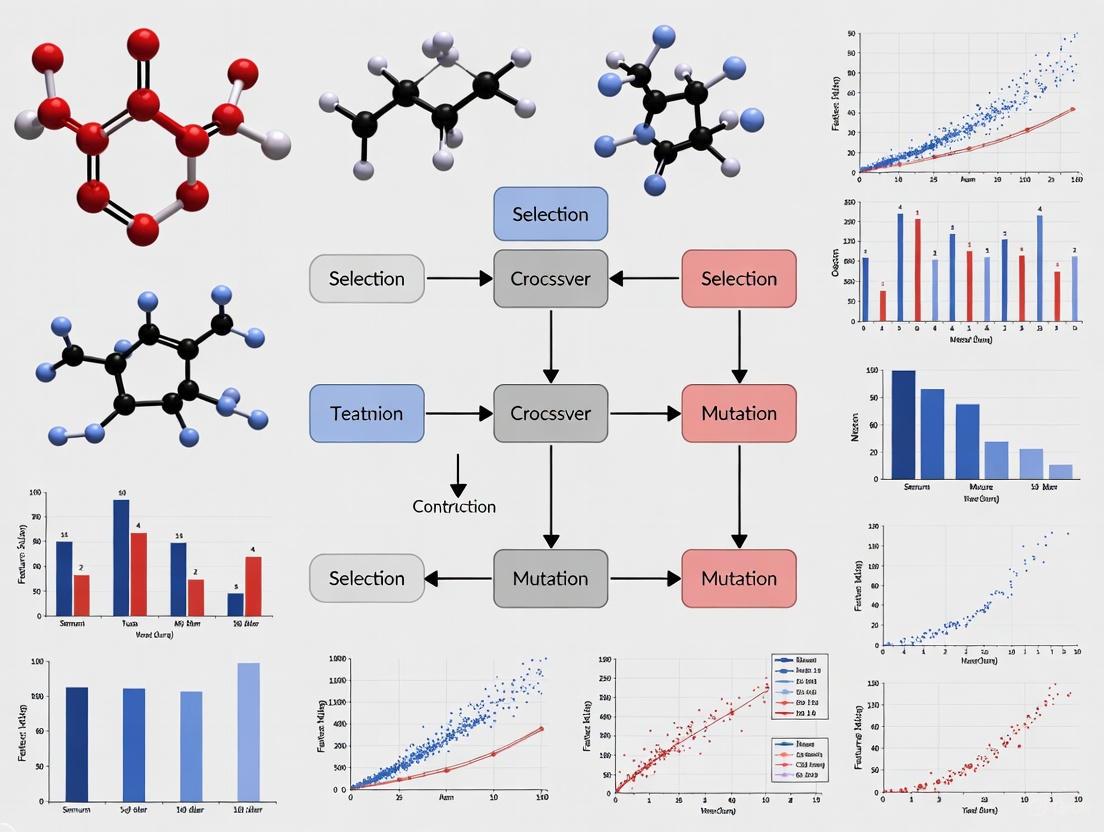

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Workflow Diagram: Evolutionary Multitasking for Feature Selection

Architecture Diagram: DR-RPMODE for High-Dimensional Feature Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Feature Selection Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCI Machine Learning Repository [1] | Data Resource | Provides benchmark datasets for algorithm validation | Testing FS algorithms on standardized biomedical datasets |

| Scikit-feature Feature Selection Repository [1] | Python Library | Offers implementations of filter-based FS methods | Comparative analysis and baseline performance evaluation |

| Kent Ridge Biomedical Data Repository [6] | Biomedical Data | Provides gene expression datasets for cancer research | Testing FS algorithms on high-dimensional genomic data |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [3] | Interpretability Tool | Explains feature importance in complex models | Validating clinical relevance of selected features |

| Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) [2] | Data Balancing | Addresses class imbalance in biomedical datasets | Preprocessing step before feature selection |

| Binary Black Particle Swarm Optimization (BBPSO) [2] | Optimization Algorithm | Efficiently searches feature subspace for optimal subsets | High-dimensional feature selection with reduced computation |

| Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEAs) [4] | Optimization Framework | Solves conflicting objectives in feature selection | Simultaneously minimizing features while maximizing accuracy |

| Wilcoxon Signed Rank Sum Test [6] | Statistical Test | Identifies significant features based on distribution | Filter-based feature selection for non-normal data |

Core Principles of Evolutionary Multitasking

Evolutionary Multitasking (EMT) is an emerging paradigm in evolutionary computation that enables the simultaneous solving of multiple optimization tasks within a single, unified search process. It leverages the implicit parallelism of population-based search to exploit potential synergies and complementarities between tasks [7]. The fundamental principle is to transfer valuable genetic material or knowledge across different but potentially related optimization problems, thereby accelerating convergence, enhancing the quality of solutions, and improving the robustness of the search algorithm [8] [7].

In contrast to traditional Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) that handle one task at a time, EMT treats multiple tasks as a single multifactorial optimization problem. A pioneering realization of EMT is the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), which employs a single population to optimize multiple tasks in a unified space [7]. Each individual in the population is assigned a skill factor indicating the task it is associated with. Knowledge transfer is facilitated through two key mechanisms: assortative mating, which allows individuals from different tasks to produce offspring with a certain random mating probability (rmp), and vertical cultural transmission, which assigns offspring to one of their parents' tasks [7]. This framework allows for the efficient sharing of discovered building blocks and evolutionary trends, turning the optimization of one task into a stepping stone for others.

EMT for High-Dimensional Feature Selection: Application Notes

Feature selection (FS) is a critical preprocessing step in machine learning and data mining, aimed at identifying the most informative and non-redundant subset of features from high-dimensional data. FS inherently involves two conflicting objectives: minimizing the number of selected features and maximizing classification accuracy, making it a natural candidate for multi-objective optimization [9]. High-dimensional feature spaces pose significant challenges, including the "curse of dimensionality," complex feature interactions, and high computational costs [10] [11] [9].

EMT has been successfully applied to create robust frameworks for multi-objective, high-dimensional feature selection. These methods typically construct multiple, complementary tasks from the original feature selection problem. For instance, one task might operate on the full feature space for global exploration, while an auxiliary task works on a reduced subset for focused local exploitation [10] [9]. This multi-task formulation, coupled with inter-task knowledge transfer, allows EMT-based FS algorithms to achieve superior performance compared to state-of-the-art single-task methods [12] [10].

Table 1: Representative EMT Frameworks for Feature Selection

| Framework Name | Core Innovation | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|

| MO-FSEMT [12] | Multi-solver-based optimization with task-specific knowledge transfer. | Superior overall performance on 26 datasets compared to state-of-the-art FS methods. |

| DMLC-MTO [10] | Dynamic multi-indicator task construction and hierarchical elite competition learning. | Achieved highest accuracy on 11/13 datasets and fewest features on 8/13; average accuracy of 87.24%, average dimensionality reduction of 96.2%. |

| DREA-FS [9] | Dual-perspective dimensionality reduction and a dual-archive multitask optimization mechanism. | Outperformed state-of-the-art multi-objective algorithms on 21 datasets and can identify diverse, equivalent feature subsets. |

Experimental Protocols for EMT-based Feature Selection

Protocol 1: Dual-Task Optimization with Knowledge Transfer

This protocol outlines the procedure for the DMLC-MTO framework, which implements a dynamic dual-task learning paradigm [10].

Aim: To efficiently perform feature selection on high-dimensional data by co-optimizing a global task and a dynamically constructed auxiliary task.

Materials:

- High-dimensional dataset (e.g., gene expression data, SNP data).

- Computational resources for running evolutionary algorithms and evaluating classifiers.

Method:

- Task Construction:

- Global Task (T~G~): Define the original feature selection problem using the complete set of

Dfeatures. - Auxiliary Task (T~A~): Construct a reduced feature subset using a multi-criteria strategy.

- Calculate feature relevance scores using multiple filter indicators (e.g., Relief-F, Fisher Score).

- Resolve potential conflicts between indicators and apply adaptive thresholding to select a subset of the most informative features.

- Global Task (T~G~): Define the original feature selection problem using the complete set of

- Population Initialization & Skill Factoring:

- Initialize a unified population of individuals, where each individual encodes a potential feature subset.

- Assign each individual a skill factor (τ), randomly designating it to either T~G~ or T~A~.

- Evolutionary Optimization with Competitive Learning:

- For each generation, evaluate individuals on their assigned task using a multi-objective evaluation function (e.g., minimizing feature count and classification error rate).

- Implement a competitive particle swarm optimization (PSO) mechanism enhanced with hierarchical elite learning.

- Within each task, particles learn from both the global best solution and elite individuals to avoid premature convergence.

- Probabilistic Inter-Task Knowledge Transfer:

- With a defined probability, allow particles from one task to learn from elite solutions in the other task's population.

- This transfer leverages the global perspective of T~G~ and the focused, reduced-noise search of T~A~.

- Termination and Output:

- Repeat steps 3-4 until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., maximum generations).

- Output the set of non-dominated feature subsets from the final population.

Protocol 2: Multi-Objective FS with Dual-Archive Strategy

This protocol is based on the DREA-FS algorithm, designed for identifying multiple high-performing feature subsets [9].

Aim: To solve multi-objective feature selection while also discovering distinct feature subsets with equivalent performance (multimodal solutions).

Materials:

- High-dimensional classification dataset.

- Access to filter-based and group-based feature reduction methods.

Method:

- Dual-Perspective Task Formulation:

- Construct two simplified and complementary tasks from the original high-dimensional problem.

- Task A: Use an improved filter-based method to generate a reduced feature space based on statistical properties.

- Task B: Use a group-based method (e.g., clustering) to group correlated features and select representatives, creating a different reduced search space.

- Dual-Archive Optimization:

- Employ a multi-population EMT approach, with a separate population for each task.

- Maintain two shared archives:

- Elite Archive: Preserves solutions with the best convergence (i.e., Pareto-optimal solutions).

- Diversity Archive: Specifically maintains feature subsets that have equivalent objective values (similar accuracy and size) but consist of different features, thus preserving multimodal solutions.

- Inter-Task Knowledge Transfer:

- Facilitate genetic exchange between the two tasks based on their complementarity.

- The elite archive provides convergence guidance, while the diversity archive injects variation into the populations.

- Output:

- Upon termination, the algorithm outputs a Pareto front of non-dominated feature subsets.

- Additionally, for points on the Pareto front, the diversity archive provides alternative feature subsets, offering diverse options for decision-makers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for an EMT-FS Research Pipeline

| Item / Solution | Function / Role in EMT-FS |

|---|---|

| Filter Methods (e.g., Relief-F, Fisher Score) [10] | Used for constructing auxiliary tasks by evaluating and ranking features based on statistical properties, independent of a classifier. |

| Evolutionary Solvers (e.g., PSO, GA, DE) [12] [10] | Core optimization engines for exploring the feature subset space. Different solvers can be assigned to different tasks for a multi-solver approach. |

| Classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) [10] [9] | Used in wrapper-based evaluation to assess the classification performance of a selected feature subset, forming one of the optimization objectives. |

| Knowledge Transfer Mechanism (e.g., rmp, SETA) [12] [7] | The core of EMT, governing how genetic material or search trends are shared between tasks to accelerate convergence and improve solutions. |

| Performance Metrics (e.g., Accuracy, AUC, Feature Count) [10] | Quantitative measures used to evaluate the performance of feature subsets and guide the multi-objective evolutionary search. |

| Domain Adaptation Technique (e.g., SETA) [7] | For complex, heterogeneous tasks; aligns the evolutionary trends of subpopulations to enable more precise and positive knowledge transfer. |

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Diagram 1: High-level workflow of an Evolutionary Multitasking pipeline for feature selection, illustrating the parallel evolution of tasks and knowledge transfer.

Diagram 2: The Subdomain Evolutionary Trend Alignment (SETA) process for precise knowledge transfer between complex tasks.

The analysis of high-dimensional data, particularly in fields like genomics and drug development, presents a significant challenge due to the curse of dimensionality. Feature selection (FS) has become an indispensable preprocessing step for enhancing model interpretability, improving classification accuracy, and reducing computational costs [10] [13]. Traditional wrapper-based feature selection methods using evolutionary algorithms often encounter limitations, including premature convergence and high computational expenditure, when dealing with complex, high-dimensional datasets such as microarray data for disease diagnosis [13].

To address these challenges, Evolutionary Multitasking (EMT) has emerged as an innovative optimization approach that enables the simultaneous solution of multiple related tasks by facilitating knowledge transfer across them [13]. When combined with the robust search capabilities of Genetic Algorithms (GAs), EMT creates a powerful framework that leverages genetic operators—crossover, mutation, and selection—to enhance search efficiency and solution quality [10]. This synergy allows for the exploitation of complementarities between different feature selection tasks, leading to accelerated convergence and improved feature subset selection for applications in precision medicine and drug development [10] [13].

This article explores the theoretical foundations and practical implementation of combining EMT with GAs for feature selection, with particular emphasis on how genetic operators can be adapted and optimized within a multitasking environment. We provide detailed protocols and application notes tailored for researchers and scientists working in bioinformatics and pharmaceutical development.

Theoretical Foundation

Genetic Algorithms: Core Components and Operators

Genetic Algorithms are population-based optimization techniques inspired by natural selection and genetics. The core components of a GA include:

- Initialization: Generating an initial population of possible solutions (chromosomes), typically randomly within defined parameter bounds [14].

- Selection: Identifying the fittest individuals based on a fitness function to produce offspring for the next generation [15] [14].

- Crossover: Combining genetic information from two parents to create new offspring, exploiting existing genetic material [15] [16].

- Mutation: Introducing random changes to individual genes to maintain genetic diversity and explore new regions of the search space [15] [16].

The balance between exploration (via mutation) and exploitation (via crossover) is critical to GA performance [16]. The probabilities of crossover and mutation significantly impact the algorithm's ability to find optimal solutions without premature convergence or excessive computational overhead [16].

Evolutionary Multitasking: Concepts and Frameworks

Evolutionary Multitasking is an emerging optimization paradigm that enables the simultaneous solution of multiple optimization tasks while facilitating knowledge transfer between them [13]. EMT frameworks are generally classified into two categories:

- Multifactorial-based Methods: These employ a single population to solve multiple tasks simultaneously, with each individual evaluated across different tasks and knowledge transfer occurring implicitly during evolution [13].

- Multi-population Methods: These assign separate populations to different tasks, allowing independent evolution with controlled interactions for explicit knowledge transfer [13].

In the context of feature selection, EMT has demonstrated significant potential for handling high-dimensional datasets by constructing multiple complementary tasks from the same dataset and leveraging their latent synergies [10]. For instance, one task might involve selecting features from the entire feature space, while another focuses on a reduced subset generated using filter methods like Relief-F or Fisher Score [10] [13].

Synergistic Integration: How EMT Enhances Genetic Algorithms

The integration of EMT with GAs creates a synergistic relationship that addresses fundamental limitations of traditional evolutionary approaches for feature selection:

- Enhanced Knowledge Transfer: Through carefully designed crossover operations between individuals from different tasks, beneficial genetic material can be shared across task boundaries, potentially accelerating convergence for all tasks [10].

- Dynamic Balance of Exploration and Exploitation: EMT naturally maintains population diversity through its multiple task structure, while GA operators provide the mechanism for both local refinement and global search [10] [4].

- Avoidance of Premature Convergence: The multitasking framework reduces the likelihood of getting trapped in local optima by allowing transfer of genetic material from populations exploring different regions of the solution space [13].

Table 1: Benefits of Integrating EMT with Genetic Algorithms for Feature Selection

| Aspect | Traditional GA | EMT-Enhanced GA | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convergence Speed | Standard convergence rate | Accelerated convergence | Leverages knowledge transfer between tasks [10] |

| Population Diversity | Limited by single task focus | Enhanced through multiple tasks | Reduces premature convergence risk [13] |

| Solution Quality | May stagnate at local optima | Improved global search capability | Exploits complementarity between tasks [10] |

| Computational Efficiency | Higher costs for complex problems | Better resource utilization | Shares evaluations across related tasks [4] |

Application Notes: EMT-GA for Feature Selection

Task Formulation and Design Strategies

Effective task design is crucial for successful EMT-GA implementation in feature selection. The following strategies have proven effective:

- Dual-Task Generation: Create two complementary tasks from the same dataset—one preserving the global feature space and another operating on a reduced subset identified by filter methods like Relief-F or Fisher Score [10]. This approach provides both global comprehensiveness and local focus.

- Multi-Indicator Integration: Combine multiple feature relevance indicators (e.g., Relief-F and Fisher Score) with adaptive thresholding to resolve conflicts between different criteria and select truly informative features [10].

- Dynamic Task Construction: Implement mechanisms for dynamically constructing tasks based on ongoing evaluation of feature relevance, allowing the algorithm to adapt to emerging patterns in high-dimensional data [10].

For genomic data analysis, particularly in drug development contexts, these task formulation strategies enable researchers to leverage domain knowledge while maintaining the exploratory power of evolutionary computation.

Adaptation of Genetic Operators for EMT

The genetic operators in EMT require specific adaptations to facilitate effective knowledge transfer:

- Crossover Operations: Implement specialized crossover mechanisms that enable productive information exchange between solutions from different tasks. The scattered crossover approach, where a random binary vector determines the parent source for each gene, has shown particular promise in EMT environments [15].

- Mutation Strategies: Incorporate adaptive mutation operators that adjust mutation rates based on both individual fitness and task performance. Elite individuals may undergo fewer mutations to preserve valuable genetic material, while poorer performers receive more substantial modifications [15].

- Selection Mechanisms: Utilize selection techniques that consider both within-task performance and cross-task potential. Tournament selection with appropriate sizing can effectively balance these considerations while maintaining selection pressure [15].

Table 2: Genetic Operator Adaptations for EMT Feature Selection

| Operator | Standard Implementation | EMT Adaptation | Benefit in Feature Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crossover | Single-point or two-point | Scattered or uniform crossover | Enables flexible knowledge transfer between different feature subsets [15] |

| Mutation | Fixed probability | Adaptive mutation based on fitness and task | Preserves useful feature combinations while exploring new ones [15] |

| Selection | Roulette wheel or rank-based | Tournament selection with elite retention | Maintains diversity while ensuring cross-task knowledge preservation [15] [14] |

| Initialization | Random population generation | Task-specific initialization using filter methods | Provides promising starting points for different aspects of feature space [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dual-Task Multitasking with Competitive Elites

This protocol implements a dynamic multitask learning framework that integrates competitive learning and knowledge transfer for high-dimensional feature selection [10].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for EMT-GA Feature Selection

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-dimensional genomic dataset (e.g., microarray data) | Primary data for feature selection analysis | Typically 1000+ features with 50-500 samples [13] |

| Relief-F algorithm | Filter method for auxiliary task construction | Identifies features relevant to class distinction [10] [13] |

| Fisher Score algorithm | Additional filter method for multi-indicator integration | Provides complementary feature relevance assessment [10] |

| Competitive Particle Swarm Optimization | Alternative optimization core for comparison studies | Benchmark against GA-based approaches [10] |

| Classification evaluator (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) | Wrapper method for subset evaluation | Assesses quality of selected feature subsets [10] |

Procedure

Task Generation:

- Generate two complementary tasks using a multi-criteria strategy that combines Relief-F and Fisher Score with adaptive thresholding.

- The first task (global) retains the complete feature space.

- The second task (focused) operates on a reduced subset containing features identified as relevant by the filter methods.

Population Initialization:

- Initialize separate populations for each task using task-specific strategies.

- For the global task, initialize with diverse random feature subsets.

- For the focused task, prioritize features with high relevance scores.

Optimization Loop:

- Perform the following steps for a predetermined number of generations or until convergence criteria are met: a. Evaluate individuals in both populations using the appropriate fitness function (e.g., classification accuracy with feature count penalty). b. Apply competitive selection within each population using tournament selection. c. Implement hierarchical elite learning, where particles learn from both winners and elite individuals. d. Execute probabilistic elite-based knowledge transfer, allowing individuals to selectively learn from elite solutions across tasks. e. Apply crossover with probability Pc (typically 0.6-0.8) and mutation with probability Pm (typically 0.01-0.1).

Solution Extraction:

- Combine elite solutions from both tasks.

- Apply final refinement through local search if necessary.

- Select the best overall solution based on dominance and diversity criteria.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this protocol:

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Calculate performance metrics including classification accuracy, number of selected features, and computational time.

- Compare results against single-task GA implementations and other state-of-the-art feature selection methods.

- Perform statistical significance testing (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to validate performance improvements.

Protocol 2: Adaptive Initialization and Multitasking for Bi-objective Feature Selection

This protocol addresses bi-objective feature selection problems aiming to simultaneously minimize classification error and the number of selected features, particularly for large-scale datasets [4].

Procedure

Adaptive Initialization:

- Generate multiple subpopulations with different initialization strategies distributed across promising regions of the objective space.

- Analyze initial subpopulations and reserve only those with promising exploration values.

- Assign different task numbers to each reserved subpopulation to create a hybrid initial population.

Dynamic Multitask Framework:

- Implement a flexible multitask merging mechanism that analyzes the current population state to determine when to merge subpopulations.

- Maintain separate subpopulations initially to preserve diversity.

- Gradually merge subpopulations as convergence progresses to enhance exploitation.

Hybrid Reproduction:

- Implement reproduction operations that can function in both multitask and single-task modes based on the current population structure.

- Adaptively set crossover rates between solutions from different tasks based on their task numbers and performance characteristics.

- Utilize an adaptive mutation strategy that adjusts mutation probability based on individual fitness and population diversity.

Termination and Solution Selection:

- Terminate when maximum generations are reached or improvement stagnates.

- Extract non-dominated solutions from the final population.

- Present the Pareto front of solutions representing different trade-offs between classification accuracy and feature set size.

The following diagram illustrates the adaptive initialization process:

Results and Discussion

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

The EMT-GA framework has demonstrated superior performance in high-dimensional feature selection tasks compared to traditional approaches. Experimental results on 13 high-dimensional benchmark datasets show that the proposed method achieves the highest accuracy on 11 out of 13 datasets and the fewest selected features on eight out of 13, with an average accuracy of 87.24% and an average dimensionality reduction of 96.2% [10].

In bi-objective feature selection, the adaptive initialization and multitasking approach (AIMEA) shows significantly better performances on most datasets in terms of widely-used performance indicators, along with generally less computational time and better solution distributions compared to seven existing algorithms [4].

Parameter Configuration and Optimization

Optimal parameter configuration is crucial for EMT-GA performance:

- Crossover Probability: Typically ranges between 0.6-0.8 for effective knowledge transfer without excessive disruption of good solutions [16].

- Mutation Probability: Generally maintained at lower values (0.01-0.1) to preserve useful genetic material while maintaining diversity [16].

- Population Size: Varies based on problem complexity, with larger populations (100-200) beneficial for high-dimensional problems [10].

- Selection Pressure: Tournament sizes of 3-5 provide effective selection pressure without excessive elitism [15].

Applications in Drug Development and Precision Medicine

The EMT-GA framework offers particular promise for drug development applications:

- Biomarker Discovery: Identification of minimal gene sets with maximal diagnostic or prognostic value from high-dimensional genomic data [13].

- Drug Response Prediction: Selection of relevant features for predicting patient response to specific therapeutics.

- Toxicity Assessment: Identification of key features associated with adverse drug reactions.

The multitasking approach allows researchers to simultaneously address multiple related objectives, such as identifying biomarkers for both efficacy and safety assessment.

The synergy between Evolutionary Multitasking and Genetic Algorithms represents a significant advancement in feature selection methodology, particularly for high-dimensional data analysis in drug development and precision medicine. By leveraging adapted crossover, mutation, and selection operators within a multitasking framework, researchers can achieve superior performance in identifying relevant feature subsets while reducing computational costs.

The protocols and application notes provided in this article offer practical guidance for implementing EMT-GA approaches in research settings. As the field evolves, further refinements in knowledge transfer mechanisms and adaptive operator design will continue to enhance the capabilities of these methods for addressing the complex challenges of high-dimensional data analysis in biomedical research.

Evolutionary Multitasking for Feature Selection (EMT-FS) represents a paradigm shift in how evolutionary computation addresses the complex, high-dimensional challenges inherent in feature selection for domains such as bioinformatics and drug development. Traditional evolutionary algorithms typically solve a single optimization task in isolation, operating under a zero-prior knowledge assumption and often struggling with the "curse of dimensionality" presented by modern datasets [17]. In contrast, EMT-FS introduces a novel optimization framework that simultaneously addresses multiple self-contained feature selection tasks, enabling implicit or explicit knowledge transfer across related tasks to accelerate convergence and improve solution quality [17]. This approach mirrors human cognitive capabilities in managing and executing multiple tasks concurrently, leveraging complementarities between tasks to enhance overall optimization efficacy.

The fundamental motivation for EMT-FS stems from the recognition that real-world feature selection problems seldom exist in isolation. Particularly in genomic data classification and drug development applications, researchers often face multiple related datasets or varying analytical perspectives on the same biological problem [18]. The multifactorial evolution (MFE) framework formalizes this approach by enabling a single population of individuals to simultaneously optimize multiple tasks, with each individual being evaluated based on a specific task determined by its "skill factor" [17]. This intrinsic multitasking capability allows promising genetic material discovered for one task to be transferred to others, potentially revealing synergistic relationships that accelerate the discovery of optimal feature subsets across related problems.

Complementing the MFE approach, multi-population methods (MPM) employ explicit population partitioning to address different aspects of the feature selection problem through specialized subpopulations. These co-evolving populations maintain their own evolutionary trajectories while engaging in controlled information exchange, creating a collaborative optimization environment that preserves diversity while enhancing convergence [4] [18]. The integration of MFE and MPM frameworks has demonstrated remarkable success in tackling high-dimensional feature selection, particularly for genomic data characterized by small sample sizes and thousands of features [18]. This article provides a comprehensive technical examination of these core EMT-FS frameworks, detailing their theoretical foundations, methodological implementations, and practical applications in biomedical research.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Formal Problem Definition

In the context of feature selection, multi-task optimization aims to find optimal solutions for K self-contained feature selection tasks within a single run of an evolutionary algorithm. For a K-task minimization problem, this can be mathematically represented as follows [17]:

where $Ti$ represents the i-th feature selection task and $xi^*$ is the optimal solution for that task. Each task $T_i$ itself can be formulated as a single-objective or multi-objective optimization problem, though feature selection typically involves balancing two conflicting objectives: minimizing the number of selected features while maximizing classification accuracy [9] [4].

Key Properties in Multifactorial Evolution

The multifactorial evolution framework introduces several key properties for evaluating individuals in a multitasking environment [17]:

- Factorial Cost: For an individual $pi$ evaluated on task $Tj$, the factorial cost $Ψj^i$ represents the objective value of $pi$ as a potential solution to $T_j$.

- Factorial Rank: The factorial rank $rj^i$ is the position of $pi$ in a list of all individuals sorted in ascending order of their factorial cost for task $T_j$.

- Skill Factor: The skill factor $τi$ of an individual $pi$ is the index of the task on which the individual performs most effectively, formally defined as $τi = \arg \min{j∈{1,2,...,K}} r_j^i$.

- Scalar Fitness: The scalar fitness $φi$ of an individual $pi$ provides a unified performance measure across all tasks, calculated as $φi = 1 / \min{j∈{1,2,...,K}} r_j^i$.

These properties enable the evolutionary algorithm to effectively manage and select individuals across multiple concurrent feature selection tasks, facilitating implicit genetic transfer while maintaining appropriate selection pressure toward optimal solutions for each task.

Complementary Multi-Population Formulations

Multi-population methods employ distinct formalisms to coordinate specialized subpopulations. Each subpopulation $P_k$ (where $k = 1, 2, ..., M$) typically focuses on a specific region of the objective space or employs a unique search strategy [4]. The adaptive initialization mechanism in approaches like AIMEA generates strategically distributed subpopulations that collectively cover promising areas of the objective space, enabling rapid exploration of non-conflicting regions before focusing on areas where objectives conflict [4]. This formulation acknowledges that in feature selection, the relationship between minimizing selected features and maximizing classification accuracy may not be uniformly conflicting across the entire search space, allowing for more efficient optimization through population specialization.

Table 1: Core Definitions in Multifactorial Evolution for Feature Selection

| Term | Mathematical Representation | Interpretation in Feature Selection Context |

|---|---|---|

| Factorial Cost | $Ψ_j^i$ | Classification error rate achieved by feature subset $pi$ when evaluated on task $Tj$ |

| Factorial Rank | $r_j^i$ | Competitive ranking of feature subset $pi$ against other subsets specifically for task $Tj$ |

| Skill Factor | $τi = \arg \minj r_j^i$ | Index identifying which feature selection task (e.g., filter-based or group-based) the subset $p_i$ solves most effectively |

| Scalar Fitness | $φi = 1 / \minj r_j^i$ | Unified quality measure enabling comparison of feature subsets across different tasks |

Core Framework 1: Multifactorial Evolution

Fundamental Mechanisms

The multifactorial evolution framework operates through several integrated mechanisms that enable concurrent optimization of multiple feature selection tasks. At its core, this approach maintains a unified population of individuals where each individual possesses a skill factor indicating its specialized task [17]. The evolutionary process incorporates both intra-task and inter-task reproduction operations, with the latter facilitating knowledge transfer between related feature selection problems. This transfer occurs through crossover operations between parents with different skill factors, allowing beneficial feature combinations discovered for one task to be applied to another task. The selection process utilizes scalar fitness as a unified metric to compare individuals across tasks, ensuring that high-performing individuals for any task have preservation opportunities regardless of their specialized function.

Skill factor inheritance represents a crucial mechanism in multifactorial evolution. During reproduction, offspring typically inherit their skill factor from parent solutions, maintaining cultural traits across generations while allowing for occasional exploration through random reassignment [17]. This inheritance mechanism ensures that valuable task-specific genetic material continues to propagate within appropriate contexts while still permitting cross-task innovation. The resulting evolutionary system naturally balances exploitation of task-specific knowledge with exploration of transferable patterns across tasks, making it particularly effective for related feature selection problems that share underlying biological structures, such as different genomic datasets for similar disease conditions.

Implementation in DREA-FS

The DREA-FS algorithm exemplifies advanced multifactorial evolution through its dual-perspective dimensionality reduction strategy and dual-archive optimization mechanism [9]. This approach constructs two complementary feature selection tasks using distinct dimensionality reduction methodologies: an improved filter-based method and a group-based method. The filter-based task prioritizes individual feature relevance using statistical measures, while the group-based task emphasizes feature interactions and complementarities. These simplified tasks facilitate rapid identification of promising regions in the high-dimensional feature space, with knowledge transfer between tasks enabling comprehensive exploration of feature interactions that might be overlooked in single-task optimization.

DREA-FS incorporates a sophisticated dual-archive mechanism to manage the balance between convergence and diversity [9]. The elite archive maintains pressure toward Pareto-optimal solutions for the primary feature selection objectives, while the diversity archive preserves feature subsets with equivalent classification performance but different feature compositions. This dual-archive approach specifically addresses the multimodal nature of feature selection, where distinct feature subsets can yield identical classification performance due to redundant or correlated features. For drug development professionals, this capability provides diverse biomarker options with equivalent predictive power but potentially different clinical measurement costs or biological interpretations.

Table 2: Multifactorial Evolution Components in DREA-FS

| Component | Implementation in DREA-FS | Benefit for Feature Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Task Formulation | Dual tasks: filter-based and group-based dimensionality reduction | Complementary perspectives on feature relevance and interactions |

| Knowledge Transfer | Implicit genetic transfer through cross-task crossover | Leverages patterns discovered in one task to enhance another |

| Diversity Management | Dual-archive strategy (elite archive + diversity archive) | Preserves multimodal solutions with equivalent performance |

| Skill Factor Assignment | Based on factorial rank across both tasks | Automatically specializes individuals to appropriate tasks |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow of the multifactorial evolution framework as implemented in DREA-FS, showing the interaction between its core components:

Core Framework 2: Multi-Population Methods

Architectural Principles

Multi-population methods in EMT-FS employ explicit population partitioning to address different aspects of the feature selection problem through specialized subpopulations with coordinated search strategies. Unlike the unified population approach of multifactorial evolution, multi-population frameworks maintain distinct subpopulations that may focus on different regions of the objective space, employ varied search operators, or tackle transformed versions of the original optimization problem [4] [18]. The fundamental architectural principle involves decomposing the complex high-dimensional feature selection challenge into more manageable subtasks distributed across specialized subpopulations, with controlled migration mechanisms facilitating knowledge exchange between populations.

The adaptive initialization mechanism in algorithms like AIMEA exemplifies the strategic approach to subpopulation management in multi-population methods [4]. This approach generates multiple initially distributed subpopulations that collectively cover promising regions of the objective space, particularly focusing on areas where the two primary feature selection objectives (minimizing feature count and maximizing classification accuracy) may not be in direct conflict. By rapidly converging through non-conflicting regions before tackling areas with stronger objective conflicts, this method achieves more efficient optimization compared to unified approaches that must simultaneously address all regions of the objective space. The dynamic multitask framework in AIMEA further enhances this approach by adaptively merging subpopulations based on their evolutionary state, maintaining an appropriate balance between diversity preservation and convergence acceleration throughout the optimization process.

Implementation in AIMEA and EMT-IGWO

The AIMEA algorithm implements a sophisticated multi-population approach through its adaptive initialization and dynamic multitasking framework [4]. The algorithm begins by generating multiple task-related subpopulations distributed across different regions of the feature selection objective space. Each subpopulation receives a task number corresponding to its specialized search focus, creating a multitask environment that accelerates convergence through complementary exploration. As evolution progresses, the algorithm continuously monitors population states and dynamically merges subpopulations when appropriate, eventually transitioning to a unified population approach for refinement. This adaptive structure enables the algorithm to leverage the benefits of population specialization during early exploration while avoiding excessive fragmentation during later exploitation phases.

EMT-IGWO employs a multi-population co-evolution strategy specifically designed for high-dimensional genomic data classification [18]. This approach utilizes multiple searching modes operating concurrently as distinct feature selection tasks within an evolutionary multitasking framework. The algorithm enhances the standard Gray Wolf Optimization method with improved global search capabilities and mechanisms to help stagnant individuals escape local optima. By maintaining multiple co-evolving populations with specialized search characteristics and information-sharing mechanisms, EMT-IGWO achieves both enhanced population diversity and improved global search capability, crucial for addressing the high-dimensionality and small sample sizes characteristic of genomic data.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the dynamic workflow of multi-population methods as implemented in AIMEA, highlighting the adaptive population management and task coordination:

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Multi-Population EMT-FS Approaches

| Characteristic | AIMEA Approach | EMT-IGWO Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Initialization | Adaptive task-related subpopulations based on objective space analysis | Multi-population with different searching modes |

| Task Coordination | Dynamic merging of subpopulations based on evolutionary state | Fixed multi-population with information sharing |

| Reproduction Mechanism | Hybrid reproduction with adaptive cross-task crossover rates | Enhanced Gray Wolf Optimization with co-evolution |

| Specialization Focus | Regions of objective space with different conflict characteristics | Complementary search strategies and patterns |

| Termination State | Typically unified single population | Maintains multiple coordinated populations |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Standardized Evaluation Methodology

Comprehensive evaluation of EMT-FS frameworks requires rigorous experimental protocols to assess both optimization performance and practical utility in biomedical applications. The established methodology involves testing across multiple real-world datasets with varying dimensionality characteristics, comparative analysis against state-of-the-art alternative algorithms, and assessment using multiple performance metrics that capture different aspects of algorithm effectiveness [9] [4] [18]. Standard practice employs 20-21 classification datasets spanning different domains and dimensionality ranges to ensure robust evaluation, with genomic datasets being particularly relevant for drug development applications [9] [4] [18].

Performance assessment typically employs three complementary categories of metrics: convergence quality metrics measuring how closely solutions approximate the true Pareto front, diversity metrics assessing the distribution and spread of solutions along the Pareto approximation, and statistical significance tests validating performance differences [9] [4]. For feature selection specifically, additional practical metrics include computational efficiency, stability of selected feature subsets, and biological relevance of discovered features in domain-specific contexts. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Friedman test are commonly employed for statistical validation of performance differences across multiple datasets [4].

Detailed Protocol for EMT-FS Evaluation

Dataset Preparation and Partitioning:

- Collect 20+ benchmark datasets with varying dimensionality (500-10,000+ features) and sample sizes, ensuring representation of different problem characteristics [9] [4].

- For genomic data applications, include 8+ public gene expression datasets with typical high-dimensional characteristics (thousands of features, small sample sizes) [18].

- Apply standard preprocessing: normalize features, handle missing values, and encode categorical variables appropriately.

- Implement stratified train-test splits (typically 70-30 or 80-20) to maintain class distribution, with further cross-validation within training folds for model assessment.

Algorithm Configuration and Parameter Settings:

- Implement EMT-FS algorithms with population sizes of 100-200 individuals, scaled appropriately for problem dimensionality.

- Configure evolutionary operators: crossover rate (0.8-0.9), mutation rate (1/D, where D is dimensionality), and generation count (100-500).

- Set task-specific parameters: for DREA-FS, configure filter and group-based reduction parameters; for AIMEA, initialize 4-6 task-related subpopulations [9] [4].

- Employ standard classification models (e.g., k-NN, SVM, decision trees) for wrapper-based evaluation with consistent hyperparameters across comparisons.

Performance Assessment and Statistical Testing:

- Execute 30 independent runs of each algorithm to account for stochastic variations.

- Calculate hypervolume indicator, inverted generational distance, and spread metrics for solution set quality assessment.

- Record computational time and function evaluations for efficiency comparisons.

- Apply Wilcoxon signed-rank test at α=0.05 significance level for pairwise comparisons and Friedman test with post-hoc analysis for multiple algorithm rankings.

Essential Research Reagents for EMT-FS Experimental Validation

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for EMT-FS Implementation and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in EMT-FS Research |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | UCI Repository datasets, Microarray gene expression data (e.g., Leukemia, Colon Tumor), RNA-seq datasets | Standardized testing and performance comparison across diverse problem characteristics [9] [18] |

| Software Frameworks | MATLAB, Python (scikit-learn, DEAP), Java-based evolutionary computation platforms | Algorithm implementation, experimental automation, and results analysis |

| Performance Metrics | Hypervolume, Inverted Generational Distance, Spread, Classification Accuracy, Feature Subset Size | Quantitative assessment of solution quality, diversity, and practical effectiveness [9] [4] |

| Statistical Tests | Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Friedman test with post-hoc analysis | Statistical validation of performance differences and algorithm rankings [4] |

| Reference Algorithms | NSGA-II, MOEA/D, SPEA2, traditional wrapper approaches | Baseline comparisons and established performance benchmarks [9] [4] |

Protocol for Genomic Data Application

For drug development professionals applying EMT-FS to genomic data classification, the following specialized protocol is recommended:

Data Preprocessing and Feature Pruning:

- Obtain raw genomic data (microarray or RNA-seq) from public repositories (GEO, TCGA) or proprietary sources.

- Apply log-transformation to normalize skewed expression distributions in microarray data.

- Perform quality control: remove probes with excessive missing values, low expression, or minimal variance.

- Implement moderate filter-based prescreening to reduce extreme dimensionality (e.g., remove 50-70% of features with lowest variance or correlation to outcome).

- Address class imbalance through appropriate sampling techniques if necessary.

EMT-FS Configuration for Genomic Applications:

- Select multitasking framework appropriate for data characteristics: DREA-FS for discovering equivalent biomarker sets, EMT-IGWO for very high-dimensional data [9] [18].

- Configure objective functions: classification error rate (using 5-fold cross-validation) and feature subset size.

- Set population size to 100-150 individuals with generation count of 200-400 based on computational constraints.

- Implement knowledge transfer mechanisms with controlled intensity to prevent negative transfer between potentially heterogeneous tasks.

Validation and Interpretation:

- Perform external validation on held-out test sets with strict separation from training data.

- Conduct biological validation through pathway enrichment analysis of frequently selected features.

- Compare with clinical gold standards and existing biomarkers for practical relevance assessment.

- Analyze robustness through stability measures across multiple runs and data perturbations.

The core EMT-FS frameworks of multifactorial evolution and multi-population methods represent significant advancements in addressing the formidable challenges of high-dimensional feature selection for biomedical applications. Multifactorial evolution approaches like DREA-FS leverage implicit knowledge transfer between complementary task formulations to accelerate convergence while maintaining diversity through sophisticated archive management [9]. Multi-population methods such as AIMEA and EMT-IGWO employ explicit population partitioning and dynamic task coordination to specialize search efforts while enabling constructive information exchange [4] [18]. Both frameworks demonstrate superior performance compared to traditional single-task evolutionary approaches, particularly for the high-dimensional, small-sample-size scenarios prevalent in genomic research and drug development.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these EMT-FS frameworks offer practical solutions to critical feature selection challenges. The ability to identify multiple equivalent feature subsets with comparable classification performance but different biological compositions provides valuable flexibility in biomarker selection, considering factors such as measurement cost, clinical practicality, and biological interpretability [9]. The structured experimental protocols and comprehensive evaluation methodologies outlined in this article provide a rigorous foundation for implementing and validating these approaches in both research and practical applications. As EMT-FS methodologies continue to evolve, their integration with deep learning architectures, transfer learning paradigms, and multi-omics data integration represents promising directions for enhancing their capabilities in addressing the increasingly complex feature selection challenges of modern biomedical research.

In the field of machine learning, particularly for high-dimensional data in critical areas like drug development, feature selection is a crucial preprocessing step. It aims to identify the most relevant subset of features, improving model performance, reducing computational costs, and enhancing interpretability [10] [5]. However, this process is an NP-hard problem where the search space grows exponentially with dimensionality, making efficient optimization a significant challenge [10] [9].

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) have shown promise in addressing this complex combinatorial problem. The emerging paradigm of Evolutionary Multitasking (EMT) tackles multiple optimization tasks simultaneously, leveraging latent synergies and complementary information between tasks. Knowledge transfer is the core mechanism that enables this synergy, allowing algorithms to share and utilize information across tasks, thereby accelerating convergence speed and improving the quality of solutions [5] [19]. For the pharmaceutical industry, where high-dimensional biological data is common, these advanced algorithms can significantly streamline the identification of biomarkers and predictive features, directly impacting the efficiency of drug discovery pipelines [20] [21].

This application note details the methodology and experimental protocols for implementing and evaluating knowledge transfer within a multitasking genetic algorithm framework for feature selection. It is structured to provide researchers and drug development professionals with practical tools to integrate these advanced techniques into their workflows.

Key Concepts and Definitions

- Evolutionary Multitasking (EMT): An optimization paradigm that solves multiple tasks concurrently within a single evolutionary run. It operates on a unified search space or population where individuals can potentially contribute to solving any of the defined tasks [19].

- Knowledge Transfer: The process of sharing and reusing genetic material or learned information between different optimization tasks within an EMT framework. This is the key mechanism for improving convergence and search efficiency [10] [5].

- Negative Transfer: A detrimental phenomenon where the transfer of knowledge between two unrelated or poorly-matched tasks leads to performance degradation instead of improvement [5].

- Task Relatedness: A measure of the similarity or compatibility between tasks, which determines the potential benefit of knowledge transfer. High task relatedness promotes positive transfer [5].

- Feature Selection: The process of selecting a subset of relevant features from a high-dimensional original set for use in model construction. In a multitasking context, multiple feature selection tasks derived from the same dataset can be solved together [10] [9].

Quantitative Performance of Multitasking FS Algorithms

The effectiveness of Evolutionary Multitasking for feature selection is demonstrated by its performance on high-dimensional benchmark datasets. The following tables summarize key quantitative results from recent state-of-the-art studies.

Table 1: Performance Summary of DMLC-MTO on 13 High-Dimensional Datasets [10] [22]

| Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|

| Average Classification Accuracy | 87.24% |

| Average Dimensionality Reduction | 96.2% |

| Median Number of Selected Features | 200 |

| Number of Datasets with Highest Accuracy | 11 out of 13 |

| Number of Datasets with Fewest Features | 8 out of 13 |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Advanced EMT-based FS Methods [10] [5] [9]

| Algorithm | Key Strength | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| DMLC-MTO [10] | Balanced exploration and exploitation via elite competition | Superior accuracy and feature reduction on 13 benchmarks |

| EMTRE [5] | Task relevance evaluation and guided knowledge transfer | Outperformed various state-of-the-art FS methods on 21 datasets |

| DREA-FS [9] | Multi-objective optimization with dual-perspective reduction | Outperformed state-of-the-art multi-objective algorithms on 21 datasets; capable of identifying equivalent feature subsets |

Experimental Protocols for EMT-based Feature Selection

Protocol 1: Dynamic Multi-Task Construction and Optimization

This protocol outlines the procedure for the DMLC-MTO framework, which generates complementary tasks for efficient knowledge transfer [10].

Application Note: This protocol is particularly suited for very high-dimensional datasets (e.g., gene expression data) where a global search is computationally expensive. The auxiliary task provides a focused, efficient search space.

Step 1: Task Construction

- Input: High-dimensional dataset ( D ) with feature set ( F ).

- Procedure:

- Define Global Task (( Tg )): The original feature selection problem using the full feature set ( F ) [10].

- Define Auxiliary Task (( Ta )):

- Output: Two tasks, ( Tg ) and ( Ta ).

Step 2: Population Initialization

- Procedure: Initialize a unified population ( P ). Each individual is encoded as a binary vector representing a feature subset and is assigned a skill factor (a random task identifier) [10].

Step 3: Competitive Optimization with Hierarchical Elite Learning

- Procedure: For each generation:

- Intra-task Competition: Within each task, particles are randomly paired for competition. The losers (worse fitness) update their positions by learning from the winners and from an archive of elite individuals [10].

- Knowledge Transfer: Implement a probabilistic elite-based transfer mechanism. Allow particles from one task to selectively learn from elite solutions in the other task [10].

- Procedure: For each generation:

Step 4: Termination and Output

- Condition: Terminate after a predefined number of generations or convergence is reached.

- Output: The best feature subset found for the global task ( T_g ) [10].

Protocol 2: Task Relevance Evaluation and Guided Transfer (EMTRE)

This protocol focuses on ensuring beneficial knowledge transfer by quantitatively evaluating task relatedness before transfer occurs [5].

Application Note: Use this protocol when dealing with multiple subtasks (more than two) to prevent negative transfer. It is computationally more intensive but leads to more stable and effective optimization.

Step 1: Multi-Task Generation via Feature Weighting

Step 2: Task Relevance Evaluation and Selection

- Procedure:

- Define a metric for task relevance, such as the average crossover ratio, which measures the overlap and complementarity between feature subsets of different tasks [5].

- Model the selection of the most relevant ( k ) tasks as the heaviest k-subgraph problem.

- Use a branch-and-bound method to solve this problem and select the optimal set of subtasks for the multitasking environment [5].

- Procedure:

Step 3: Optimization with Guided Knowledge Transfer

- Procedure:

- Initialize a population for the multitasking system.

- During evolution, facilitate knowledge transfer using guiding vectors. These vectors are derived from high-quality solutions and are adapted over time using a convergence factor to balance exploration and exploitation [5].

- Procedure:

Step 4: Final Output

- Output: The optimal feature subsets for each of the selected, related tasks.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key components of a dynamic multitasking evolutionary algorithm for feature selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Algorithms for EMT Feature Selection

| Item Name | Function / Role in Experiment | Exemplars / Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Evaluate feature relevance independently of a classifier to construct auxiliary tasks or pre-filter features. | Relief-F, Fisher Score [10] [5] |

| Evolutionary Algorithms | Core search engine for finding optimal feature subsets within the multitasking framework. | Competitive Particle Swarm Optimization (CSO), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [10] [5] |

| Task Relatedness Metric | Quantifies similarity between tasks to guide and improve the safety of knowledge transfer. | Average Crossover Ratio [5] |

| Knowledge Transfer Strategy | The mechanism that allows different tasks to share information, improving overall convergence. | Probabilistic Elite Transfer [10], Guiding Vector-based Transfer [5] |

| Performance Evaluation Metrics | Used to assess the quality of the selected feature subsets and the efficiency of the algorithm. | Classification Accuracy, Number of Selected Features, Dimensionality Reduction Rate [10] [9] |

The integration of knowledge transfer within multitasking genetic algorithms represents a significant advancement for tackling high-dimensional feature selection problems. The structured protocols and performance data provided here demonstrate that these methods consistently achieve superior classification accuracy with significant feature reduction. For the drug development sector, adopting these protocols can enhance the analysis of complex omics data, improve biomarker discovery, and ultimately contribute to more efficient therapeutic development pipelines. Future work will focus on automating task-relatedness detection and developing more robust transfer strategies to further minimize the risk of negative transfer.

Implementing Multitasking GA Frameworks: Strategies and Biomedical Applications

In high-dimensional feature selection, particularly within domains such as drug response prediction and genetic analysis, the curse of dimensionality presents a significant challenge to developing accurate and interpretable models [10] [23]. Evolutionary multitasking has emerged as a powerful optimization paradigm that addresses this challenge by solving multiple related tasks simultaneously, thereby leveraging knowledge transfer to accelerate search efficiency and improve solution quality [10]. Central to the success of evolutionary multitasking is the creation of complementary tasks that capture different aspects of the feature selection problem. Among various approaches, filter methods like Relief-F have demonstrated exceptional utility in constructing these dual-task frameworks, enabling algorithms to balance global exploration and local exploitation effectively [10] [13].

The Relief-F algorithm and its extensions belong to the family of attribute weighting algorithms that efficiently identify feature associations with class variables, even when features exhibit nonlinear interactions without significant main effects [24]. This capability makes Relief-F particularly valuable for genetic analysis where epistatic interactions are common [24] [25]. When integrated into dual-task generation strategies, Relief-F provides a mechanism for creating reduced feature subspaces that guide evolutionary search toward promising regions of the solution space, complementing tasks that operate on the full feature set [10] [13].

This application note outlines detailed protocols for implementing dual-task generation strategies using Relief-F and related filter methods within evolutionary multitasking frameworks. We provide comprehensive experimental methodologies, performance benchmarks, and practical implementation guidelines to enable researchers to effectively apply these techniques to high-dimensional feature selection problems in drug development and genetic analysis.

Theoretical Foundation

Relief-F Algorithm and Variants

The Relief algorithm, initially described by Kira and Rendell, is a simple, fast, and effective approach to attribute weighting that outputs a weight between -1 and 1 for each feature, with more positive weights indicating higher predictive strength [24]. The core intuition behind Relief is that feature value changes accompanied by class changes should be upweighted, while feature value changes with no class change should be downweighted [24].

The algorithm operates by selecting random samples from the data, finding their nearest neighbors from the same class (nearest hits) and opposite class (nearest misses), and updating feature weights based on value differences [24]. Relief-F extends this approach to handle noisy, incomplete datasets with multiple classes by using k nearest hits and k nearest misses, averaging their contributions to update attribute weights [24].

More recent variations include:

- SURF (Spatially Uniform ReliefF): Uses all neighbors within a certain distance threshold rather than a fixed number k [24]

- SURF*: Utilizes both nearby and distant neighbors for weight updates [24]

- SWRF*: Employs a soft neighbor weighting kernel through a sigmoid function [24]

- sReliefF: Adapted for survival data with censoring, introducing reclassification and weighting schemes [25]

For genetic data analysis, these algorithms demonstrate strong robustness to noise and ability to identify interacting genetic variants, making them particularly suitable for preliminary feature screening in high-dimensional domains [24] [25].

Evolutionary Multitasking in Feature Selection

Evolutionary Multitasking (EMT) represents an innovative optimization approach that enables simultaneous resolution of multiple related tasks through knowledge transfer [13]. In the context of feature selection, EMT frameworks typically generate multiple tasks from the same dataset, each focusing on different aspects of the feature space [10] [13]. The fundamental advantage of this approach lies in its ability to share evolutionary information between tasks, allowing promising feature subsets discovered in one task to influence the search process in another [13].

Multi-population EMT methods, where each task is assigned a separate population that evolves independently but with controlled interactions for knowledge transfer, have demonstrated particular success in feature selection applications [13]. These methods maintain task-specific evolution while enabling flexible and targeted knowledge sharing between populations [13].

Dual-Task Generation Methodologies

Multi-Indicator Task Construction

Advanced dual-task generation employs a multi-criteria strategy that combines multiple feature relevance indicators to create complementary tasks [10]. This approach typically generates two distinct tasks:

Global Task: Utilizes the complete feature space to maintain comprehensive search capabilities and prevent premature exclusion of potentially relevant features [10]

Auxiliary Task: Employs a reduced feature subset identified through filter methods like Relief-F, often enhanced by integrating multiple feature relevance indicators such as Fisher Score [10]

The integration of multiple indicators helps resolve conflicts that may arise when different filter criteria prioritize different feature subsets, ensuring the auxiliary task captures a robust set of features with strong predictive power [10]. Adaptive thresholding mechanisms further refine this process by dynamically determining the optimal feature subset size based on dataset characteristics [10].

Table 1: Feature Relevance Indicators for Dual-Task Construction

| Indicator | Computational Basis | Strengths | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relief-F | Instance-based learning using nearest neighbors | Identifies nonlinear interactions; robust to noise | Genetic datasets with epistatic interactions [24] [25] |

| Fisher Score | Distance-based metric between class means | Computational efficiency; no distribution assumptions | Continuous data with approximately normal distributions [10] |