Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization in Practice: Accelerating Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

This article explores the transformative potential of Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) in real-world biomedical optimization, with a specific focus on drug discovery.

Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization in Practice: Accelerating Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) in real-world biomedical optimization, with a specific focus on drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive guide from foundational principles to advanced applications. The content delves into the core mechanisms of knowledge transfer, showcases practical methodologies for solving complex, related optimization tasks simultaneously, and addresses critical challenges like negative transfer. It further validates EMTO's performance against traditional single-task optimization through empirical studies and real-world case studies, concluding with future directions that integrate cutting-edge technologies like Large Language Models (LLMs) for autonomous algorithm design, positioning EMTO as a key enabler for the next generation of efficient and precise pharmaceutical research.

The Foundations of Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization: Principles and Pharmaceutical Promise

Defining Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) and Its Core Paradigm

Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) represents an emerging paradigm in computational intelligence that addresses multiple optimization problems simultaneously through a single search process [1]. The fundamental premise of EMTO lies in exploiting the synergies and complementarities between different tasks, allowing knowledge gained from optimizing one problem to enhance the search for solutions to other related problems [2] [1]. This approach marks a significant departure from traditional evolutionary algorithms that typically focus on solving one optimization problem at a time in isolation.

The conceptual foundations of EMTO are built upon the observed capability of evolutionary algorithms to implicitly transfer valuable knowledge between tasks during the optimization process [2]. Through what is termed "implicit parallelism," EMTO algorithms can generate more promising individuals during evolution that potentially jump out of local optima, thereby addressing key limitations of conventional evolutionary approaches that often struggle with local convergence and generalization issues [2]. The paradigm has gained substantial attention from the Evolutionary Computation community in recent years, particularly due to its potential for solving complex real-world optimization scenarios where multiple related problems coexist [3].

Core Paradigms and Methodological Approaches

Fundamental Principles

EMTO operates on the principle that concurrently solving multiple optimization tasks can be more efficient than handling them separately when the tasks share underlying commonalities [4]. The mathematical formulation of a multi-task environment comprises K optimization tasks {T₁, T₂, ..., Tₖ} defined over corresponding search spaces {Ω₁, Ω₂, ..., Ωₖ} [3]. For the k-th task with Mₖ objective functions (where Mₖ > 1), the goal is to find optimal solution sets {xₖ} such that:

{xₖ} = argmin Fₖ(xₖ | xₖ ∈ Ωₖ), for k = 1, 2, 3, ..., K [4]

The efficiency gains in EMTO are achieved through knowledge transfer mechanisms that allow information exchange between tasks, potentially accelerating convergence and improving solution quality across all problems being optimized simultaneously [1] [4].

Primary Algorithmic Paradigms

The EMTO landscape encompasses several distinct methodological approaches, each with characteristic mechanisms for knowledge transfer and population management.

Table 1: Core Paradigms in Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization

| Paradigm | Key Mechanism | Representative Algorithms | Knowledge Transfer Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multifactorial Optimization | Single unified search space with skill factors | Multi-Objective Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MO-MFEA) [5] [4] | Implicit transfer through shared chromosomal representation |

| Multi-Population Approach | Separate populations for different tasks | Incremental Learning Methods [4], Autoencoder-based Transfer [4] | Explicit migration of promising individuals between populations |

| Multi-Criteria Formulation | Treats multiple tasks as evaluation criteria | Multi-Objective Multi-Criteria Evolutionary Algorithm (MO-MCEA) [4] | Adaptive criterion selection for environmental selection |

The multifactorial-based approach typically employs a single population evolving in a unified search space, where individuals are assigned skill factors to indicate their proficiency on different tasks [4]. In contrast, non-multifactorial approaches maintain multiple populations dedicated to specific tasks, with carefully designed knowledge transfer mechanisms to exchange information between these populations [4]. A more recent innovation formulates multitask optimization as a multi-criteria optimization problem, where fitness evaluation functions for different tasks are treated as distinct criteria within a unified evolutionary process [4].

Experimental Protocols and Assessment Methodologies

Standard Experimental Framework

Robust experimental design is crucial for validating EMTO algorithms and demonstrating their efficacy compared to single-task optimization approaches. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive methodology for empirical evaluation:

Phase 1: Benchmark Selection and Preparation

- Select established multi-task benchmark suites that encompass problems with known inter-task relationships

- Include real-world optimization scenarios where task relatedness can be empirically justified [3]

- Define performance metrics including convergence speed, solution quality, and computational efficiency

Phase 2: Algorithm Implementation

- Implement the EMTO algorithm with carefully designed knowledge transfer mechanisms

- Configure population size and representation according to problem dimensionality and characteristics

- Set control parameters for evolutionary operators (crossover, mutation) and knowledge transfer rates

Phase 3: Comparative Analysis

- Execute comparative trials against single-task evolutionary algorithms and state-of-the-art EMTO approaches

- Employ statistical significance testing to validate performance differences

- Conduct sensitivity analysis on key algorithm parameters

Phase 4: Knowledge Transfer Assessment

- Quantify the efficacy and efficiency of knowledge transfer between tasks [3]

- Analyze negative transfer instances and implement mitigation strategies

- Evaluate computational overhead compared to single-task optimization

A critical aspect of experimental validation involves demonstrating that the multitasking approach provides tangible benefits compared to solving problems in isolation with competitive single-task optimization algorithms [3].

Performance Metrics and Evaluation

Comprehensive assessment of EMTO algorithms requires multiple quantitative metrics to capture different aspects of performance:

Table 2: Essential Metrics for EMTO Performance Evaluation

| Metric Category | Specific Measures | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Quality | Hypervolume, Inverted Generational Distance, Pareto Front Coverage | Measures convergence to true Pareto optimal solutions |

| Convergence Speed | Function Evaluations to Target Precision, Generations to Convergence | Quantifies acceleration through knowledge transfer |

| Computational Efficiency | Runtime, Memory Usage, Complexity Analysis | Assesses practical implementation overhead |

| Transfer Effectiveness | Success Rate of Transferred Solutions, Negative Transfer Impact | Evaluates knowledge exchange quality |

Recent research emphasizes the importance of not only measuring fitness improvements but also accounting for computational effort when claiming performance advantages of EMTO approaches [3].

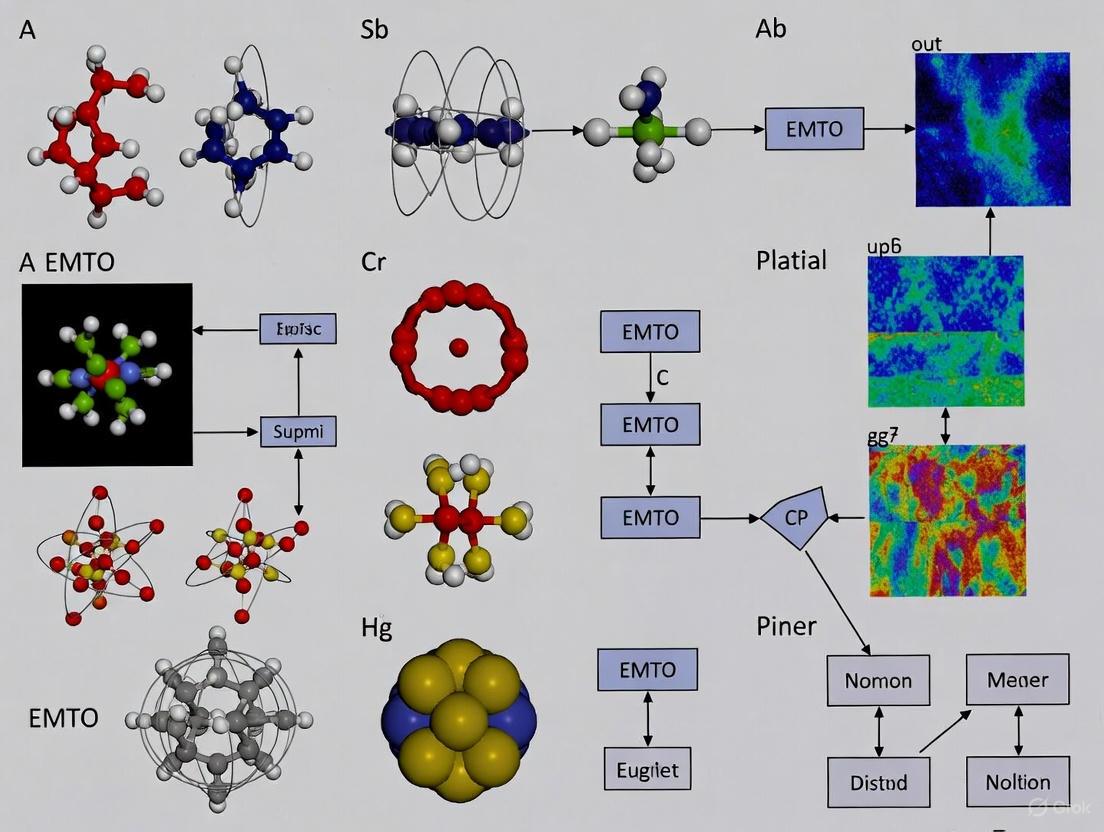

Visualization of EMTO Framework

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and knowledge flow in a typical Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization system:

EMTO System Architecture illustrates the fundamental components and interactions in an Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization framework. Multiple optimization tasks are simultaneously addressed by a unified population that evolves through standard evolutionary operators. The key differentiator is the knowledge transfer mechanism that enables implicit exchange of valuable genetic material between tasks, potentially enhancing convergence across all problems.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Algorithmic Components

The development and implementation of effective EMTO systems requires specific algorithmic components that function as essential "research reagents" for constructing viable solutions.

Table 3: Essential Components for EMTO Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Unified Representation | Encodes solutions for multiple tasks in a shared search space | Chromosomal design must accommodate different problem domains and dimensionalities |

| Skill Factor Allocation | Identifies individual proficiency on different tasks | Determines how solutions evaluate across tasks and participate in knowledge transfer |

| Knowledge Transfer Mechanism | Facilitates exchange of genetic material between tasks | Must balance exploration and exploitation while minimizing negative transfer |

| Cultural Exchange Operators | Specialized crossover and mutation for multi-task context | Designed to preserve and transfer building blocks across task boundaries |

| Adaptive Parameter Control | Dynamically adjusts algorithm parameters during evolution | Responds to changing complementarities between tasks throughout search process |

The skill factor implementation is particularly critical, as it enables the algorithm to identify which individuals are most valuable for different tasks and how they should participate in the evolutionary process [4]. Similarly, the design of knowledge transfer mechanisms requires careful consideration to maximize positive transfer while minimizing the potential negative impact of transferring information between unrelated problems [3].

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite significant advances in EMTO methodologies, several challenges remain unresolved and represent promising avenues for future research. A primary concern involves the plausibility and practical applicability of the paradigm, with questions about whether real-world optimization scenarios naturally accommodate simultaneous processing of multiple related problems [3]. The community must direct efforts toward identifying and formalizing genuine use cases where multitasking provides unequivocal benefits over single-task approaches.

The novelty of algorithmic contributions represents another critical consideration. Researchers should ensure that proposed EMTO methods constitute genuine advancements beyond straightforward adaptations of existing evolutionary algorithms [3]. This requires rigorous conceptual development and avoidance of terminology ambiguities that might obscure the actual scientific contributions.

Methodologies for evaluating performance of multitasking algorithms need refinement beyond current practices. Future research should develop more comprehensive assessment frameworks that account not only for solution quality but also computational efficiency, robustness to negative transfer, and scalability to problems with varying degrees of inter-task relatedness [3]. Benchmark construction should move beyond problems with artificially engineered correlations toward real-world inspired test suites.

Promising research directions include developing more sophisticated knowledge transfer mechanisms that autonomously learn inter-task relationships during evolution, adaptive resource allocation strategies that dynamically balance computational effort between tasks, and theoretical foundations that explain when and why multitasking provides optimization advantages. Integration with other machine learning paradigms such as transfer learning and domain adaptation also represents a valuable frontier for EMTO research [3].

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in computational problem-solving, moving beyond traditional single-task evolutionary algorithms by enabling the simultaneous optimization of multiple tasks. This emerging field capitalizes on the fundamental principle that valuable knowledge exists across different optimization tasks, and that the transfer of this knowledge can significantly enhance performance in solving each task independently [6]. The critical innovation lies in creating a multi-task environment where implicit parallelism and cross-domain knowledge work synergistically to improve optimization efficiency, convergence speed, and solution quality [6] [2].

The concept of knowledge transfer (KT) serves as the cornerstone of EMTO, distinguishing it from conventional evolutionary approaches. While traditional evolutionary algorithms must solve each optimization problem in isolation, EMTO frameworks facilitate bidirectional knowledge exchange between tasks, allowing them to learn from each other's search experiences [6]. This capability is particularly valuable in real-world applications where correlated optimization tasks are ubiquitous, from drug discovery pipelines to complex engineering design problems [2]. The multifactorial evolutionary algorithm (MFEA), pioneered by Gupta et al., established the foundational framework for this approach by evolving a single population to solve multiple tasks while implicitly transferring knowledge through chromosomal crossover between individuals from different tasks [6] [7].

However, the effectiveness of EMTO heavily depends on the design of its knowledge transfer mechanisms. The field grapples with the persistent challenge of negative transfer—where knowledge from one task detrimentally impacts performance on another—particularly when optimizing tasks with low correlation or differing dimensionalities [6] [7]. Recent advances have focused on developing more sophisticated transfer strategies that can dynamically adapt to evolutionary scenarios, align latent task representations, and leverage machine learning techniques to optimize the transfer process itself [8] [7]. This article explores these developments through structured protocols, quantitative comparisons, and practical frameworks to guide researchers in implementing effective knowledge transfer strategies for complex optimization challenges.

Fundamental Concepts and Taxonomy of Knowledge Transfer

Key Principles and Definitions

Knowledge transfer in EMTO operates on the premise that optimization tasks often possess underlying commonalities that can be exploited to accelerate search processes. The mathematical formulation of a multi-task optimization problem encompassing K tasks typically follows the structure below, where each task Ti aims to minimize an objective function fi over a search space X_i [7]:

The efficacy of knowledge transfer hinges on two fundamental questions: "when to transfer" and "how to transfer" knowledge between tasks [6] [8]. The "when" question addresses the timing and intensity of transfer, seeking to identify opportune moments and appropriate tasks for knowledge exchange. The "how" question focuses on the mechanisms and representations used for transferring knowledge, which can range from direct solution migration to sophisticated subspace alignment techniques [6]. Contemporary EMTO research has developed a multi-level taxonomy to systematically categorize knowledge transfer methods based on their approaches to addressing these core questions, facilitating a structured understanding of the field's diversity [6].

Knowledge Transfer Taxonomy

The design space of knowledge transfer mechanisms in EMTO can be decomposed into several interconnected dimensions. At the highest level, transfers can be categorized as implicit or explicit based on their methodology [7]. Implicit transfer mechanisms, exemplified by MFEA, operate through unified search spaces and genetic operations like crossover between individuals from different tasks, leveraging skill factors to denote task competency [7]. In contrast, explicit transfer mechanisms employ dedicated operations to directly transfer knowledge, often using mapping functions or specialized representations to bridge disparate task domains [7] [9].

A more granular taxonomy further distinguishes knowledge transfer approaches based on their handling of the "when" and "how" questions [6]. For determining when to transfer, methods may utilize similarity measurement techniques (e.g., MMD, KLD) to assess task relatedness, adaptive probability mechanisms that dynamically adjust transfer rates based on historical effectiveness, or learning-based approaches that use reinforcement learning to optimize transfer timing [6] [8] [10]. For determining how to transfer, strategies include direct solution transfer, subspace alignment methods that project tasks into shared latent spaces, population distribution transfer, and meta-knowledge transfer that extracts higher-level search characteristics [7] [9] [10].

Quantitative Analysis of Knowledge Transfer Methods

Performance Comparison of EMTO Algorithms

Table 1: Comparative Performance of EMTO Algorithms on Benchmark Problems

| Algorithm | Knowledge Transfer Mechanism | Convergence Speed | Solution Accuracy | Negative Transfer Resistance | Computational Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFEA [7] | Implicit (chromosomal crossover) | Medium | Medium | Low | Low |

| MFEA-MDSGSS [7] | MDS-based subspace alignment + GSS | High | High | High | Medium |

| SSLT [8] | Self-learning via Deep Q-Network | High | High | High | High |

| CKT-MMPSO [9] | Bi-space knowledge reasoning | Medium | High | Medium | Medium |

| KSP-EA [11] | Knowledge structure preserving | Medium | High | High | Medium |

| Population Distribution-based [10] | MMD-based distribution similarity | Medium | Medium | High | Low |

Knowledge Transfer Efficiency Across Scenarios

Table 2: Transfer Efficiency Across Different Evolutionary Scenarios

| Evolutionary Scenario | Recommended KT Strategy | Expected Convergence Improvement | Diversity Maintenance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only similar shape [8] | Shape KT strategy | 25-40% | Medium | Tasks with similar fitness landscape morphology |

| Only similar optimal domain [8] | Domain KT strategy | 20-35% | High | Tasks sharing promising search regions |

| Similar shape and domain [8] | Bi-KT strategy | 35-50% | Medium | Highly correlated tasks |

| Dissimilar shape and domain [8] | Intra-task strategy | 0-10% | High | Unrelated or competing tasks |

| High-dimensional tasks [7] | Subspace alignment | 15-30% | Medium | Tasks with differing dimensionalities |

| Multi-objective tasks [9] | Collaborative KT | 20-45% | High | Problems with conflicting objectives |

The quantitative comparison reveals several important patterns in knowledge transfer effectiveness. Algorithms incorporating adaptive mechanisms (SSLT, MFEA-MDSGSS) generally demonstrate superior performance across diverse problem types, particularly in resisting negative transfer [8] [7]. The scenario-specific analysis underscores that no single transfer strategy dominates all situations, highlighting the importance of matching transfer mechanisms to problem characteristics [8]. For multi-objective optimization problems, approaches that leverage knowledge from both search and objective spaces (CKT-MMPSO) show notable advantages in maintaining diversity while accelerating convergence [9].

Application Protocols for Knowledge Transfer Implementation

Protocol 1: MDS-Based Subspace Alignment for High-Dimensional Transfer

Purpose: To enable effective knowledge transfer between tasks with differing dimensionalities while minimizing negative transfer.

Background: Direct knowledge transfer between high-dimensional tasks often fails due to the curse of dimensionality and difficulty learning robust mappings from limited population data [7]. This protocol uses multidimensional scaling (MDS) to establish low-dimensional subspaces where effective transfer can occur.

Materials/Resources:

- Population data from each optimization task

- MDS implementation for dimensionality reduction

- Linear domain adaptation algorithm for subspace alignment

- Golden section search mechanism for local optimization

Procedure:

- Subspace Construction: For each task Ti, apply MDS to population data to construct a low-dimensional subspace Si that preserves pairwise distances between individuals.

- Alignment Matrix Learning: For each task pair (Ti, Tj), employ linear domain adaptation to learn a mapping matrix Mij that aligns subspace Si to S_j.

- Knowledge Transfer: When transferring knowledge from Ti to Tj: a. Project source solution xi from Ti to its subspace Si b. Apply mapping matrix: x{i→j} = Mij · xi c. Project x{i→j} to target task Tj's search space

- Local Refinement: Apply golden section search to refine transferred solutions in promising regions.

- Adaptive Probability Update: Adjust inter-task transfer probabilities based on historical success rates.

Validation Metrics:

- Convergence speed improvement compared to single-task optimization

- Success rate of transferred solutions (proportion leading to fitness improvement)

- Final solution quality across all tasks

Troubleshooting:

- If negative transfer occurs frequently, increase subspace dimensionality or strengthen similarity thresholds for transfer

- If alignment quality is poor, increase population size to provide more data for mapping learning

Protocol 2: Scenario-Based Self-Learning Transfer Framework

Purpose: To automatically select and adapt knowledge transfer strategies based on evolutionary scenarios using reinforcement learning.

Background: Fixed transfer strategies often underperform when faced with diverse and dynamically changing evolutionary scenarios [8]. This protocol uses a Deep Q-Network to learn the optimal mapping between scenario characteristics and transfer strategies.

Materials/Resources:

- Feature extraction methods for intra-task and inter-task scenario characterization

- Deep Q-Network implementation with experience replay

- Scenario-specific strategies: intra-task, shape KT, domain KT, bi-KT

- Evolutionary solver (DE, GA, or PSO) as backbone optimizer

Procedure:

- Scenario Characterization: For each generation, extract features capturing: a. Intra-task characteristics: population diversity, convergence degree b. Inter-task characteristics: fitness landscape similarity, optimal domain overlap

- Strategy Portfolio Definition: Maintain four scenario-specific strategies: a. Intra-task strategy: independent evolution for dissimilar tasks b. Shape KT: transfer convergence trends for tasks with similar fitness landscapes c. Domain KT: transfer distribution knowledge for tasks with similar optimal regions d. Bi-KT: combined approach for tasks similar in both shape and domain

- Reinforcement Learning Setup: a. State: extracted scenario features b. Actions: available transfer strategies c. Reward: fitness improvement normalized by computational cost

- Training Phase: Execute random strategies initially to build experience replay memory

- Deployment Phase: Use trained DQN to select optimal strategy based on current state

- Continuous Learning: Periodically update DQN with new experiences

Validation Metrics:

- Cumulative reward across generations

- Strategy selection patterns across different scenarios

- Performance compared to fixed-strategy baselines

Troubleshooting:

- If learning is unstable, adjust reward function or increase experience replay memory size

- If feature extraction is computationally expensive, implement sampling approaches

Protocol 3: Bi-Space Knowledge Reasoning for Multi-Objective Problems

Purpose: To improve knowledge transfer quality in multi-objective optimization by leveraging information from both search and objective spaces.

Background: Traditional EMTO primarily utilizes search space information, potentially overlooking valuable patterns evident in the objective space [9]. This protocol systematically reasons about knowledge from both spaces to enhance transfer effectiveness.

Materials/Resources:

- Multi-objective evolutionary algorithm (e.g., NSGA-II, MOEA/D)

- Similarity metrics for both search and objective spaces

- Information entropy calculations for evolutionary stage detection

- Adaptive transfer pattern selector

Procedure:

- Bi-Space Knowledge Extraction: a. Search space knowledge: population distribution models, gradient approximations b. Objective space knowledge: Pareto front characteristics, diversity metrics

- Knowledge Reasoning: a. Identify complementary knowledge between spaces b. Resolve conflicts when search and objective space suggestions disagree

- Evolutionary Stage Detection: a. Use information entropy to classify stage: early (exploration), middle (balance), late (exploitation)

- Adaptive Transfer Pattern Selection: a. Early stage: Favor diversity-oriented transfer from objective space b. Middle stage: Balance convergence and diversity using both spaces c. Late stage: Favor convergence-oriented transfer from search space

- Solution Generation: Create new solutions by combining transferred knowledge with local search

- Effectiveness Monitoring: Track success rates of different transfer patterns per stage

Validation Metrics:

- Hypervolume improvement per function evaluation

- Pareto front diversity and convergence metrics

- Pattern effectiveness by evolutionary stage

Troubleshooting:

- If objective space knowledge dominates excessively, adjust weighting factors

- If stage detection is inaccurate, incorporate additional convergence indicators

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for EMTO Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity Metrics | MMD [10], KLD [12], SISM [12] | Quantify task relatedness to guide transfer decisions | MMD effective for distribution-based similarity; SISM suitable for landscape characteristics |

| Subspace Methods | MDS [7], Autoencoders [12], LDA [7] | Project tasks to shared latent spaces for aligned transfer | MDS preserves distance relationships; autoencoders handle nonlinear mappings |

| Transfer Strategies | Shape KT, Domain KT [8], Bi-KT [8] | Scenario-specific transfer mechanisms | Shape KT transfers convergence trends; Domain KT transfers promising regions |

| Adaptation Mechanisms | Deep Q-Network [8], Randomized rmp [10], Entropy-based [9] | Dynamically adjust transfer parameters and strategies | DQN suitable for complex scenarios; entropy-based simpler to implement |

| Optimization Backbones | DE, GA, PSO [8] [9] | Base optimizers for each task | DE effective for continuous problems; PSO suitable for multi-objective scenarios |

| Performance Metrics | Convergence speed, Solution accuracy, Hypervolume [9] | Evaluate algorithm effectiveness | Hypervolume particularly important for multi-objective problems |

Advanced Visualization of Knowledge Transfer Relationships

The visualization illustrates the comprehensive knowledge transfer workflow, emphasizing the critical decision points and adaptive feedback mechanisms. The process begins with scenario analysis to characterize task relationships, followed by strategy selection based on scenario classification [8]. The implementation phase incorporates similarity assessment to validate transfer decisions, with performance evaluations feeding back into strategy adaptation [10]. This cyclic process enables continuous improvement of transfer effectiveness throughout the optimization process.

Knowledge transfer represents both the fundamental strength and most significant challenge in evolutionary multitask optimization. The protocols and frameworks presented here demonstrate that effective transfer requires careful attention to both "when" and "how" questions, with scenario-adaptive approaches generally outperforming fixed strategies [6] [8]. The emerging trend toward self-learning systems that automatically discover effective transfer patterns through reinforcement learning and meta-learning offers particular promise for handling the complexity of real-world optimization problems [8] [13].

For researchers implementing EMTO in domains like drug development where evaluation costs are high, the resistance to negative transfer must be a primary consideration [7] [10]. Protocols incorporating subspace alignment, distribution-based similarity metrics, and bi-space reasoning provide robust foundations for such applications [7] [9] [10]. As EMTO continues to evolve, the integration of transfer learning principles from machine learning with evolutionary computation represents a fertile ground for innovation, potentially enabling more efficient knowledge extraction and utilization across increasingly complex task networks [6] [12].

The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks provided here offer practical starting points for researchers exploring knowledge transfer in evolutionary computation. By systematically addressing transfer timing, mechanism selection, and adaptation strategies, these approaches can significantly enhance optimization performance across diverse application domains, from pharmaceutical development to complex engineering design.

Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) is a paradigm in evolutionary computation that optimizes multiple tasks simultaneously by leveraging implicit or explicit knowledge transfer (KT) between them [6]. The core idea is that synergies exist between related tasks; thus, knowledge gained while solving one task can accelerate convergence or improve solution quality for another [6] [2]. This paradigm is particularly valuable in real-world scenarios where multiple correlated optimization problems must be solved, as it can significantly enhance optimization efficiency compared to traditional methods that handle tasks in isolation [2].

Two principal algorithmic frameworks have emerged for implementing EMTO: the Multi-Factorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) and the Multi-Population Framework. The distinction between them primarily lies in their population structure and the mechanisms they employ for knowledge transfer. This article provides a detailed comparison of these frameworks, supported by quantitative data, structured protocols for implementation, and a discussion of their applications in real-world optimization research, including drug development.

Core Framework Analysis and Comparison

Multi-Factorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA)

The MFEA, introduced as a pioneering EMTO algorithm, uses a unified population to solve all tasks [14] [6]. In this framework, every individual in the single population is encoded in a unified search space and possesses a skill factor that identifies the task on which it is a specialist [6] [7]. Knowledge transfer occurs implicitly when individuals specializing in different tasks undergo crossover, allowing genetic material to be exchanged [7] [15]. This framework enables straightforward and frequent genetic information exchange, which can be highly effective when the optimized tasks are similar [14].

Multi-Population Framework

In contrast, the multi-population framework maintains separate populations for each task [14]. Knowledge transfer between these populations is explicit, often requiring dedicated mechanisms to map and transfer information, such as high-quality solutions or search distribution characteristics, from a source task population to a target task population [14] [10]. This approach offers greater control over the transfer process and is generally preferred when the number of tasks is large or when task similarity is limited, as it tends to produce less destructive negative transfer [14].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Multi-Factorial and Multi-Population EMTO Frameworks

| Feature | Multi-Factorial (MFEA) | Multi-Population |

|---|---|---|

| Population Structure | Single, unified population [6] | Multiple, separate populations [14] |

| Knowledge Transfer Type | Implicit (e.g., crossover) [7] | Explicit (e.g., mapping) [14] |

| Transfer Mechanism | Vertical crossover based on skill factor [15] | Dedicated mapping function or model [10] |

| Primary Advantage | Straightforward, frequent KT [14] | Controlled KT, less negative transfer [14] |

| Primary Challenge | Negative transfer for dissimilar tasks [14] [7] | Designing an effective mapping/transfer mechanism [10] |

| Ideal Use Case | Tasks with high similarity [14] | Many tasks or tasks with low similarity [14] |

Diagram 1: Architectural overview of Multi-Factorial and Multi-Population EMTO frameworks, highlighting differences in population structure and knowledge transfer mechanisms.

Advanced Knowledge Transfer Strategies

A critical challenge in both frameworks is negative transfer, which occurs when knowledge from one task hinders the optimization progress of another [6] [7]. To mitigate this, advanced knowledge transfer strategies have been developed.

Domain Adaptation techniques, such as Linear Domain Adaptation (LDA) and Progressive Auto-Encoding (PAE), aim to align the search spaces of different tasks to facilitate more effective knowledge transfer [14] [7]. For instance, the MFEA-MDSGSS algorithm uses multidimensional scaling (MDS) to create low-dimensional subspaces for each task and then employs LDA to learn linear mappings between them, enabling robust KT even for tasks with differing dimensionalities [7]. The PAE technique introduces continuous domain adaptation throughout the evolutionary process, using strategies like Segmented PAE (staged training) and Smooth PAE (using eliminated solutions) to dynamically update domain representations [14].

Population Distribution-Based strategies select transfer knowledge based on the distribution of solutions in the search space. One method involves partitioning a task population into sub-populations and using the Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) metric to identify the source sub-population most similar to the sub-population containing the best solution of the target task [10]. This approach helps select useful transfer individuals that may not be elite solutions in their own task but are relevant to the target task's current search region [10].

Diversified Knowledge Transfer strategies aim to capture and utilize not only knowledge related to convergence (finding optimal solutions) but also knowledge associated with population diversity [16]. This dual focus helps prevent premature convergence and allows for a more comprehensive exploration of the search space [16].

Table 2: Advanced Knowledge Transfer Strategies in EMTO

| Strategy | Core Principle | Representative Algorithm(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Domain Adaptation | Aligns search spaces of different tasks to enable effective KT [14] [7] | MFEA-MDSGSS [7], MTEA-PAE [14] |

| Population Distribution-Based | Uses distributional similarity between populations/sub-populations to guide KT [10] | Adaptive MTEA [10] |

| Diversified Knowledge Transfer | Transfers knowledge related to both convergence and diversity [16] | DKT-MTPSO [16] |

| Large Language Model (LLM) Based | Automatically designs novel KT models using LLMs [15] | LLM-generated KT models [15] |

Experimental Protocols for EMTO

To ensure reproducible and rigorous evaluation of EMTO algorithms, researchers can follow structured experimental protocols. The following protocols detail the implementation of a classic MFEA and a population distribution-based multi-population algorithm.

Protocol 1: Implementing a Multi-Factorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA)

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing a standard MFEA with implicit knowledge transfer via vertical crossover [6] [7].

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for MFEA Implementation

| Component/Parameter | Description & Function |

|---|---|

| Unified Representation | A chromosome encoding (e.g., random-key, floating-point vector) that is applicable across all tasks [6]. |

| Skill Factor (ρ) | A scalar assigned to each individual, identifying its specialized task for evaluation and selection [6]. |

| Factorial Cost | A vector storing the performance of an individual on every task. For the specialist task (skill factor), it is the objective value; for others, it is often penalized [6]. |

| Scalar Fitness | A single fitness value derived from the factorial cost, enabling cross-task comparison (e.g., based on rank) [6]. |

| Vertical Crossover | The knowledge transfer operator: a crossover (e.g., simulated binary crossover) applied between parents with different skill factors [7] [15]. |

| Random Mating Probability (rmp) | A key parameter controlling the probability that crossover occurs between parents with different skill factors [7]. |

4.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Initialization: Generate a single population of individuals. Encode each individual using the unified representation.

- Skill Factor Assignment & Evaluation:

- For each individual, assign a skill factor (a specific task it will be evaluated on).

- Evaluate each individual on its assigned task and record its objective value.

- Calculate the factorial cost for all individuals and subsequently their scalar fitness.

- Selection & Reproduction: Select parents for reproduction based on their scalar fitness.

- Knowledge Transfer via Vertical Crossover:

- For each pair of parents, with a probability defined by the

rmpparameter, perform crossover even if their skill factors differ. - If the skill factors differ, this vertical crossover facilitates implicit knowledge transfer.

- Apply mutation to the offspring.

- For each pair of parents, with a probability defined by the

- Offspring Evaluation: Assign skill factors to the offspring (typically inheriting from a parent or assigned based on evaluation) and evaluate them.

- Population Update: Create the next generation by selecting the best individuals from the combined parent and offspring populations based on scalar fitness.

- Termination Check: Repeat steps 2-6 until a termination criterion (e.g., maximum generations) is met.

Diagram 2: MFEA experimental workflow, illustrating the cyclic process of skill factor assignment, vertical crossover, and selection.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Population Distribution-Based Multi-Population Algorithm

This protocol describes a multi-population EMTO algorithm that uses population distribution and the MMD metric for explicit knowledge transfer [10].

4.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Components for Population Distribution-Based EMTO

| Component/Parameter | Description & Function |

|---|---|

| Task-Specific Populations | Separate populations maintained and evolved for each optimization task [10]. |

| Sub-Population Partition | A method to divide a population into K clusters/groups based on fitness or position in the search space [10]. |

| Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) | A statistical metric used to measure the distribution difference between two sub-populations; a smaller MMD indicates higher similarity [10]. |

| Adaptive Interaction Probability | A dynamically adjusted parameter that controls the frequency of knowledge transfer between tasks based on evolutionary state [10]. |

4.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Initialization: Initialize a separate population for each task.

- Sub-Population Partitioning: For each task's population, partition the individuals into K sub-populations based on their fitness values or decision variable values.

- Intra-Task Evolution: For each population, perform a standard evolutionary cycle (selection, crossover, mutation) to generate offspring. Evaluate and select to form the new population for that task.

- Explicit Knowledge Transfer (Periodic):

- Source Selection: For a target task, identify its best sub-population (e.g., the one containing the global best solution). For a source task, calculate the MMD between each of its sub-populations and the target's best sub-population.

- Knowledge Extraction: Select the source sub-population with the smallest MMD value.

- Transfer: Use individuals from this selected source sub-population to create new candidate solutions in the target task population (e.g., via crossover or as immigrants).

- Parameter Adaptation: Dynamically update the inter-task interaction probability based on the success rate of recent knowledge transfers.

- Termination Check: Repeat steps 2-5 until a termination criterion is met.

Application in Real-World Optimization and Drug Development

EMTO has demonstrated significant potential across various real-world domains, including production scheduling, energy management, and evolutionary machine learning [14]. The principles of multi-task optimization are particularly relevant to computational drug development, where several related optimization problems often arise.

Potential application scenarios include:

- Multi-Objective Molecular Design: Simultaneously optimizing a molecule for multiple properties, such as binding affinity, synthetic accessibility, and low toxicity, treating each property as a separate but related task [2].

- Pharmacokinetic (PK) Parameter Optimization: Calibrating complex PK/PD models for different but related compound series or patient populations, where knowledge about parameter sensitivities can be transferred to accelerate the overall optimization process.

- Clinical Trial Planning: Optimizing multiple aspects of trial design, such as patient recruitment strategies, dosing schedules, and endpoint analysis, as interconnected tasks within an EMTO framework.

The choice between multi-factorial and multi-population frameworks in these contexts depends on the specific problem structure. A multi-factorial approach (MFEA) may be suitable for highly similar tasks, like optimizing analogous scaffolds in molecular design. In contrast, a multi-population approach is preferable for more disparate tasks, such as jointly optimizing a compound's binding affinity and its synthetic pathway, where controlled, explicit knowledge transfer is crucial to avoid negative interference.

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) presents a transformative paradigm for addressing the complex, interrelated optimization challenges inherent in modern drug discovery. The drug development pipeline, from target identification to lead optimization, is characterized by multiple related but distinct tasks that operate on similar underlying biological and chemical principles. This paper explores the theoretical and practical synergy between EMTO frameworks and drug discovery, arguing that the field's high computational costs, significant failure rates, and interrelated optimization tasks make it a prime candidate for EMTO applications. We present specific application notes, experimental protocols, and visualization tools to facilitate the adoption of EMTO methodologies within pharmaceutical research and development.

Drug discovery represents a class of complex optimization problems characterized by high-dimensional search spaces, expensive fitness evaluations, and multiple interrelated objectives. The conventional single-task optimization paradigm often treats each stage of drug development in isolation, potentially overlooking valuable latent relationships between tasks. Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) emerges as a powerful alternative, enabling the simultaneous optimization of multiple related tasks through implicit or explicit knowledge transfer [7] [8].

The fundamental premise of EMTO aligns perfectly with the drug discovery pipeline, where optimizing a lead compound involves balancing multiple objectives—potency, selectivity, pharmacokinetics, and safety profiles—that often share underlying structure in their chemical and biological domains. The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), first proposed by Gupta et al., provides the foundational framework for such multitask optimization by maintaining a unified population of individuals encoded in a unified search space, with each individual evaluated on a specific task based on its skill factor [7] [17]. Knowledge transfer occurs through crossover operations between individuals assigned to different tasks, controlled by parameters such as random mating probability (rmp).

Recent advances in EMTO directly address key limitations that have historically hindered applications in drug discovery. The proposed MFEA-MDSGSS algorithm, for instance, integrates multidimensional scaling (MDS) with linear domain adaptation (LDA) to create robust mappings between tasks of differing dimensionalities, significantly mitigating the problem of negative transfer where knowledge from one task detrimentally impacts another [7]. This is particularly relevant in drug discovery, where optimizing for different target classes or therapeutic indications may involve related but distinct structure-activity landscapes.

Current Drug Discovery Landscape and Optimization Challenges

The contemporary drug discovery process is characterized by several distinct trends that collectively increase both its computational complexity and the potential value of advanced optimization techniques like EMTO.

Key Innovation Areas in Drug Discovery

Table 1: Key Modern Drug Discovery Approaches and Their Optimization Challenges

| Innovation Area | Description | Primary Optimization Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| AI-Driven Discovery | Using machine learning for target prediction, compound prioritization, and property estimation [18]. | High-dimensional feature spaces, integration of heterogeneous data types, limited labeled data. |

| PROTACs & Protein Degradation | Small molecules that drive protein degradation by recruiting E3 ligases [19]. | Optimizing ternary complex formation, balancing degradation efficiency with physicochemical properties. |

| Radiopharmaceutical Conjugates | Combining targeting molecules with radioactive isotopes for imaging or therapy [19]. | Simultaneous optimization of targeting specificity, payload delivery, and clearance kinetics. |

| Cell & Gene Therapies | CAR-T treatments and personalized CRISPR therapies [19] [20]. | Multi-objective optimization of efficacy, safety, and manufacturability across biological systems. |

| Host-Directed Antivirals | Targeting human proteins rather than viral components [19]. | Understanding host-pathogen interaction networks, minimizing disruption to normal physiology. |

The Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) Framework

The pharmaceutical industry increasingly relies on Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), which uses quantitative modeling and simulation to support drug development and regulatory decision-making [21]. MIDD employs various modeling approaches throughout the five-stage drug development process:

- Discovery: Target identification and lead compound optimization using QSAR and AI/ML

- Preclinical Research: PBPK modeling and FIH dose prediction

- Clinical Research: Population PK/PD, exposure-response, and adaptive trial design

- Regulatory Review: Model-based meta-analysis and comparative effectiveness

- Post-Market Monitoring: Real-world evidence generation and lifecycle management [21]

This model-rich environment naturally aligns with EMTO approaches, as each modeling stage represents a related optimization task that could benefit from knowledge transfer.

EMTO Methodologies for Drug Discovery Applications

Core EMTO Algorithms and Their Adaptations

Several EMTO architectures show particular promise for drug discovery applications:

MFEA-MDSGSS: This algorithm enhances the basic MFEA framework by integrating multidimensional scaling (MDS) and golden section search (GSS). The MDS-based linear domain adaptation method establishes low-dimensional subspaces for each task and learns linear mapping relationships between them, facilitating knowledge transfer even between tasks with differing dimensionalities [7]. This is particularly valuable in drug discovery when optimizing across different chemical series or target classes.

Competitive Scoring Mechanisms (MTCS): This approach introduces a competitive scoring mechanism that quantifies the effects of transfer evolution versus self-evolution, then adaptively sets the probability of knowledge transfer and selects source tasks [22]. The dislocation transfer strategy rearranges decision variable sequences to increase diversity, with leading individuals selected from different leadership groups to guide transfer evolution.

Scenario-Based Self-Learning Transfer (SSLT): This framework categorizes evolutionary scenarios into four situations and designs corresponding scenario-specific strategies [8]. It uses a deep Q-network (DQN) as a relationship mapping model to learn the relationship between evolutionary scenario features and optimal strategies, enabling automatic adaptation to changing optimization landscapes.

Knowledge Transfer Strategies for Drug Discovery

Effective knowledge transfer in drug discovery EMTO requires specialized strategies:

Similarity-Based Transfer: The Adaptive Similarity Estimation (ASE) strategy mines population distribution information to evaluate task similarity and adjust transfer frequency accordingly [17]. This prevents negative transfer when optimizing unrelated targets or chemical series.

Auxiliary Population Methods: Auxiliary-population-based KT (APKT) maps the global best solution from a source task to a target task using an auxiliary population, offering more useful transferred information than direct individual transfer [17].

Block-Level Transfer: BLKT-DE splits individuals into small blocks and applies evolutionary operations among these blocks, enabling effective knowledge transfer even when tasks have differently encoded decision variables [17].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Target-to-Lead Optimization Using MFEA-MDSGSS

Objective: Simultaneously optimize multiple related chemical series for a single protein target.

Materials:

- Target protein structure (experimental or predicted)

- Compound libraries for multiple chemical series

- High-performance computing cluster

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock, Schrodinger, etc.)

- ADMET prediction platform (SwissADME, etc.)

Workflow:

- Task Definition: Encode each chemical series as a separate optimization task with shared objective functions (binding affinity, synthetic accessibility, ligand efficiency).

- Population Initialization: Create unified population with individuals encoded in normalized search space [0,1]^D where D = max(dimensions across all series).

- Fitness Evaluation: Decode individuals to task-specific representation; evaluate binding affinity via molecular docking and ADMET properties via QSAR models.

- Knowledge Transfer: Apply MDS-based LDA to identify latent subspaces; transfer knowledge between tasks using learned mappings.

- Selection & Variation: Employ GSS-based linear mapping to explore promising regions; select individuals for next generation based on multifactorial fitness.

- Termination: Continue for fixed number of generations or until convergence criteria met.

Evaluation Metrics:

- Multi-task improvement ratio (MIR)

- Negative transfer frequency

- Computational efficiency gain versus sequential optimization

Diagram 1: MFEA-MDSGSS Drug Optimization Workflow

Protocol 2: Multi-Indication Lead Optimization Using Competitive Scoring

Objective: Optimize a single lead compound for multiple therapeutic indications or target proteins.

Materials:

- Structures of related target proteins

- Lead compound scaffold

- Assay data for primary and secondary indications

- MTCS optimization framework

Workflow:

- Task Setup: Define each indication/target combination as a separate optimization task with task-specific objective functions.

- Dual Evolution: Implement both transfer evolution (between tasks) and self-evolution (within tasks) components.

- Competitive Scoring: Calculate scores for each evolution type based on improvement ratios and successful evolution rates.

- Adaptive Transfer: Dynamically adjust transfer probability and source task selection based on competitive scores.

- Dislocation Transfer: Apply variable rearrangement to increase diversity when transferring between tasks.

- Validation: Experimentally test optimized compounds for each indication.

Diagram 2: Multi-Indication Optimization Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EMTO in Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in EMTO Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Target Engagement Assays | CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) [18] | Provides quantitative validation of direct drug-target engagement in intact cells, serving as fitness evaluation for optimization tasks. |

| AI/ML Prediction Platforms | Deep graph networks, QSAR models, generative AI [18] [19] | Accelerates virtual screening and property prediction, reducing expensive experimental fitness evaluations. |

| Molecular Modeling Suites | AutoDock, SwissADME, molecular dynamics simulations [18] | Enables computational assessment of binding affinity and drug-like properties for fitness evaluation. |

| High-Throughput Screening | Automated compound handling, miniaturized assays [18] | Provides experimental fitness data for multiple compounds in parallel, supporting population-based optimization. |

| E3 Ligase Toolbox | Cereblon, VHL, MDM2, IAP, and novel ligases [19] | Enables PROTAC optimization with multiple E3 ligase recruitment options as distinct but related tasks. |

| CAR-T Design Platforms | Allogeneic, dual-target, and armored CAR-T systems [19] | Provides multiple engineering approaches for cell therapy optimization as related tasks with knowledge transfer potential. |

Implementation Considerations and Future Directions

Successful implementation of EMTO in drug discovery requires addressing several practical considerations. Data quality and standardization across tasks is paramount, as knowledge transfer depends on consistent representation and evaluation of potential solutions. The curse of dimensionality remains a challenge, particularly when optimizing across diverse chemical spaces or biological targets, though techniques like MDS-based subspace alignment show promise in addressing this limitation [7].

The regulatory landscape for model-informed drug development continues to evolve, with recent ICH M15 guidance providing standardization for MIDD practices across regions [21]. Incorporating EMTO approaches within this established framework will facilitate regulatory acceptance and streamline implementation.

Future research directions should focus on real-world validation of EMTO approaches in industrial drug discovery settings, development of domain-specific knowledge transfer operators for chemical and biological spaces, and integration of EMTO with emerging AI methodologies such as foundation models for chemistry and biology. As noted by industry leaders, AI is already transforming clinical trials and regulatory documentation [20]; the natural extension is its integration with sophisticated optimization paradigms like EMTO.

The convergence of EMTO with personalized medicine approaches represents another promising frontier. The recent demonstration of personalized CRISPR therapy developed in just six months [19] highlights the movement toward rapid, individualized treatments that could benefit from multitask optimization frameworks capable of leveraging knowledge across patient-specific optimization challenges.

Drug discovery embodies the characteristics of an ideal application domain for Evolutionary Multitask Optimization: multiple related optimization tasks, expensive fitness evaluations, shared underlying structure across problems, and significant practical importance. The emerging EMTO algorithms with adaptive knowledge transfer, negative transfer mitigation, and scenario-aware optimization strategies offer tangible solutions to persistent challenges in pharmaceutical research and development. By implementing the protocols, workflows, and methodologies outlined in this paper, researchers can leverage the synergistic potential of simultaneous optimization across related drug discovery tasks, potentially accelerating the delivery of novel therapies to patients.

The convergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and personalized medicine is creating a new paradigm in healthcare, characterized by complex, multi-faceted optimization challenges. Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) emerges as a powerful computational framework to address these challenges simultaneously. EMTO leverages the implicit parallelism of tasks and knowledge transfer between them to generate promising solutions that can escape local optima, enhancing convergence speed and solution quality in complex search spaces [2]. This document details protocols and application notes for applying EMTO to key problems in AI-driven personalized medicine, providing researchers and drug development professionals with practical methodologies for real-world optimization research.

Current Trends and Quantitative Landscape

The integration of AI into healthcare, particularly personalized medicine, is accelerating. The following tables summarize key quantitative data points that define the current research and market landscape, highlighting areas where EMTO can have significant impact.

Table 1: Market Size and Growth Projections for Personalized Medicine and AI

| Market Segment | 2024/2025 Value | Projected Value | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision Medicine Market [23] | USD 118.52 Bn (2025) | USD 463.11 Bn (2034) | 16.35% (2025-2034) | Genomics, AI integration, chronic disease prevalence |

| AI in Precision Medicine Market [23] | USD 2.74 Bn (2024) | USD 26.66 Bn (2034) | 25.54% (2024-2034) | Demand for personalized healthcare, rising cancer rates |

| Hyper-Personalized Medicine Market [24] | USD 3.18 Tn (2025) | USD 5.49 Tn (2029) | 14.6% (2025-2029) | Genomic technologies, targeted therapies, big data analytics |

Table 2: Key AI Technology Trends Influencing Healthcare Optimization (2025)

| AI Trend | Core Capability | Relevance to Personalized Medicine & EMTO |

|---|---|---|

| Reasoning-Centric Models [25] [26] | Solves complex problems with logical, multi-step reasoning. | Enhances analysis of genetic, clinical, and lifestyle data for treatment prediction; improves EMTO's logical decision-making. |

| Agentic AI & Autonomous Workflows [25] [26] | Executes multi-step tasks autonomously based on a high-level goal. | Orchestrates complex research workflows (e.g., from genomic analysis to therapy suggestion); can manage EMTO processes. |

| Multimodal AI Models [25] | Understands and combines different data types (text, image, audio). | Fuses diverse patient data (EHRs, genomics, medical imaging) for a holistic view, creating rich, multi-modal optimization tasks. |

EMTO Application Notes in Personalized Medicine

The following applications demonstrate how EMTO can be deployed to solve specific optimization problems in personalized medicine.

Application Note 1: Multi-Objective Drug Synergy Prediction

1. Research Context: In oncology, combination therapies are standard, but identifying synergistic drug pairs with optimal efficacy and minimal toxicity from thousands of possibilities is a massive combinatorial challenge. This constitutes a natural Multi-task Optimization Problem (MTOP), where each task involves optimizing for a specific cancer cell line or patient-derived model.

2. EMTO Alignment: An EMTO framework can solve multiple optimization tasks (e.g., for different cancer subtypes) concurrently. Knowledge Transfer (KT) allows the algorithm to share learned patterns about promising drug interaction features across tasks, significantly accelerating the discovery of effective combinations for rare cancers where data is scarce [8].

3. Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preprocessing: Collect drug response data (e.g., from GDSC or CTRP databases). Normalize viability scores and calculate synergy scores (e.g., using ZIP or Loewe models). Featurize drugs (molecular descriptors, fingerprints) and cell lines (genomic mutations, expression profiles).

- Task Definition: Define each task as the prediction of synergy scores for a specific cell line.

- Objective Function: Maximize the correlation between predicted and observed synergy scores.

- EMTO Workflow: Implement a population-based algorithm (e.g., Genetic Algorithm) where each individual represents a potential predictive model. Utilize a Scenario-based Self-Learning Transfer (SSLT) framework to automatically select the best KT strategy (e.g., shape KT, domain KT) based on the similarity between tasks [8].

- Validation: Validate top-predicted synergistic pairs using in vitro assays in relevant cell lines.

Diagram 1: Drug synergy prediction workflow.

Application Note 2: Dynamic Treatment Regimen Optimization

1. Research Context: Personalized medicine requires treatment plans that adapt to individual patient responses over time, considering genetic makeup, disease progression, and side effects. Optimizing this temporal, patient-specific pathway is a dynamic and complex problem.

2. EMTO Alignment: The problem can be framed as a series of interconnected optimization tasks across different time points or patient cohorts. EMTO can leverage inter-task knowledge from a population of simulated or historical patients to rapidly personalize and adjust therapy for a new patient, effectively transferring knowledge about "what worked" in similar scenarios [2].

3. Experimental Protocol:

- Patient Modeling: Create a simulated or real-world dataset of patient trajectories, including baseline genetics, longitudinal biomarker data, treatment actions, and outcomes.

- Task Definition: Define each task as finding the optimal sequence of treatment actions for a single patient or a clinically similar patient subgroup.

- Objective Function: A multi-objective function maximizing long-term therapeutic efficacy while minimizing toxicity and treatment burden.

- EMTO Workflow: Use an EMTO algorithm with a memory mechanism to track successful strategies across tasks (patient models). Reinforcement learning techniques, such as Deep Q-Networks (DQN), can be integrated to learn the mapping between patient state (evolutionary scenario) and the optimal treatment adjustment (scenario-specific strategy) [8] [26].

- Validation: Use in-silico clinical trials or digital twins for initial validation, followed by pilot studies in specific patient populations.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Template for EMTO in Personalized Medicine

This protocol provides a generalized template for setting up an EMTO experiment for a healthcare optimization problem, such as feature selection for a diagnostic AI model.

Protocol Title: EMTO for Multi-Task Feature Selection in Multi-Omics Disease Classification

1. Problem Definition:

- Goal: Identify a minimal, highly predictive set of features (e.g., SNPs, gene expressions, proteomic markers) for disease subtyping across multiple related conditions (e.g., autoimmune diseases like RA, SLE, MS).

- MTOP Formulation: Each disease is a separate task. The goal is to simultaneously find the optimal feature subset for each disease's classification model.

2. Materials and Data Preparation:

- Data Sources: Public multi-omics databases (TCGA, GTEx) or in-house genomic and clinical datasets.

- Preprocessing: Perform standard normalization, missing value imputation, and batch effect correction. Split data into training, validation, and test sets for each task.

3. EMTO Algorithm Configuration:

- Backbone Solver: Genetic Algorithm (GA) or Differential Evolution (DE).

- Representation: An individual is a binary vector of length D (total features across all tasks), where '1' indicates feature selection and '0' indicates exclusion. Alternatively, use a multi-population approach.

- Objective Function (Fitness): For each task, fitness is a weighted sum of:

Fitness_k = α * (Classification Accuracy on validation set) + β * (1 - (Feature Subset Size / D))

- Knowledge Transfer Mechanism:

- When to transfer: Use a SSLT framework to dynamically decide based on inter-task similarity metrics (e.g., similarity in top-performing features or model structures) [8].

- How to transfer: Implement multiple KT strategies:

- Bi-KT Strategy: For tasks with high similarity, exchange both high-quality solutions (shape) and information about promising search regions (domain).

- Intra-task Strategy: For dissimilar tasks, focus on independent evolution to avoid negative transfer.

4. Execution Parameters:

- Population size: 100 per task

- Number of generations: 1000

- Crossover rate: 0.8

- Mutation rate: 0.05

- Stopping criterion: Convergence of fitness or maximum generations reached.

5. Evaluation and Analysis:

- Performance: Compare final classification accuracy and feature set size against single-task optimization and traditional feature selection methods (e.g., LASSO) on the held-out test set.

- Knowledge Transfer Analysis: Analyze the frequency and type of KT events to understand which strategies were most beneficial and which tasks benefited from inter-task learning.

Diagram 2: EMTO for multi-task feature selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines key computational and data "reagents" required for implementing EMTO in personalized medicine research.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for EMTO in Personalized Medicine

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function in EMTO Workflow | Exemplars / Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Omics Data | Data | Provides the foundational input for defining optimization tasks (e.g., classifying disease subtypes). | Genomic sequencing (Illumina [23]), proteomics, transcriptomics data from biobanks. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Infrastructure | Provides the computational power for running population-based evolutionary algorithms across multiple tasks. | Cloud-based (Azure ML, AWS SageMaker) or on-premise HPC clusters. |

| EMTO Software Platform | Software | The core framework for implementing and executing EMTO algorithms. | MTO-Platform toolkit [8], custom implementations in Python/Matlab. |

| Backbone Solver | Algorithm | The base evolutionary algorithm used for search and optimization within each task. | Differential Evolution (DE), Genetic Algorithm (GA) [8]. |

| Knowledge Transfer Model | Algorithm | The model that governs when and how knowledge is shared between tasks. | Deep Q-Network (DQN) for learning optimal KT policies [8]. |

| Clinical Validation Dataset | Data | A held-out, real-world dataset used to validate the generalizability and clinical relevance of the optimized solution. | Retrospective electronic health records (EHRs), prospective pilot study data. |

Implementing EMTO in Biomedical Research: Strategies and Real-World Applications

Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization (EMTO) presents a powerful paradigm for solving multiple optimization tasks concurrently by leveraging implicit parallelism and shared knowledge. The core principle of EMTO is that simultaneously optimized tasks often contain complementary knowledge, which, when transferred effectively, can significantly accelerate convergence and improve solution quality for individual tasks [6]. The design of knowledge transfer (KT) mechanisms—specifically, the mapping of solutions between task domains and the adaptive control of transfer—is therefore critical to the success of EMTO and forms the focus of these application notes. Within the broader context of a thesis on real-world EMTO applications, this document provides detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for implementing and evaluating robust knowledge transfer systems, with particular relevance to complex domains like computational drug development.

Knowledge Transfer in EMTO: Core Concepts and Taxonomy

In EMTO, knowledge transfer involves exchanging genetic or behavioral information between distinct but potentially related optimization tasks. A systematic taxonomy of KT methods is essential for selecting an appropriate mechanism. These methods primarily address two fundamental questions: when to transfer and how to transfer knowledge [6].

Table 1: Taxonomy of Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms in EMTO

| Categorization Axis | Category | Key Characteristics | Representative Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Timing | Online Adaptive | Transfer parameters are updated continuously based on population dynamics. | MTEA-PAE [14] |

| Periodic Re-matched | Transfer models are retrained at fixed intervals. | Traditional DA-based Methods [14] | |

| Static Pre-trained | Uses a fixed, pre-defined transfer model. | Pre-trained Auto-encoders [14] | |

| Transfer Method | Implicit Transfer | Leverages unified representation and crossover. | MFEA, MFEA-AKT [7] |

| Explicit Transfer | Employs dedicated mapping functions. | EMT with Autoencoding, G-MFEA [7] | |

| Knowledge Source | Intra-Population | Transfers knowledge among current task populations. | Most MFEAs [6] |

| External Archive | Utilizes eliminated solutions for gradual refinement. | Smooth PAE [14] | |

| Domain Alignment | Search Space Focus | Aligns solutions in the original decision space. | Vertical Crossover [15] |

| Latent Space Focus | Aligns tasks in a learned lower-dimensional subspace. | MFEA-MDSGSS, PAE [14] [7] |

A key challenge in KT is negative transfer, which occurs when knowledge from a dissimilar or misaligned task degrades the performance of a target task. This is often caused by premature convergence or unstable mappings between high-dimensional tasks [7]. Effective KT mechanisms must therefore incorporate similarity assessment and transfer adaptation to mitigate this risk [6].

Quantitative Analysis of Knowledge Transfer Performance

Evaluating KT mechanisms requires robust quantitative metrics. The following data, synthesized from multiple benchmark studies, provides a comparative overview of state-of-the-art algorithms.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of EMTO Algorithms on Benchmark Problems

| Algorithm | Key Transfer Mechanism | Avg. Convergence Rate (↑) | Solution Quality (Hypervolume ↑) | Negative Transfer Incidence (↓) | Reported Best Suited Task Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTEA-PAE [14] | Progressive Auto-Encoding | 1.28x | 0.89 | 5% | Single- & Multi-Objective, Dissimilar Tasks |

| MFEA-MDSGSS [7] | MDS-based Domain Adaptation & GSS | 1.35x | 0.91 | 4% | High-Dimensional Tasks, Mixed Similarity |

| CKT-MMPSO [9] | Bi-Space Knowledge Reasoning | 1.31x | 0.90 | 3% | Multi-Objective MTO Problems |

| DKT-MTPSO [16] | Diversified Knowledge Transfer | 1.22x | 0.87 | 6% | Tasks Requiring High Diversity |

| MFEA [7] | Implicit Genetic Transfer | 1.00x (Baseline) | 0.82 | 15% | Simple, Highly Similar Tasks |

| LLM-Generated Model [15] | Autonomous Model Generation | 1.25x | 0.88 | 7% | General-Purpose, Low-Human-Input |

Note: Performance metrics are normalized where possible for cross-study comparison. "Avg. Convergence Rate" is relative to the baseline MFEA. "Solution Quality" is measured by Hypervolume for multi-objective problems, normalized to a [0,1] scale. "Negative Transfer Incidence" is the frequency of performance degradation due to KT.

Application Notes and Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing and evaluating advanced KT mechanisms.

Protocol 1: Implementing Progressive Auto-Encoding (PAE) for Dynamic Adaptation

The PAE technique addresses the limitation of static transfer models by enabling continuous domain adaptation throughout the evolutionary process [14].

Workflow Overview:

Procedure:

- Initialization: For

Ktasks, initialize separate populationsP_1, P_2, ..., P_K. Set the generation countert = 0. - Segmented PAE Phase (Stage-wise Alignment):

- Divide the total number of generations,

G, intoSsegments. - At the beginning of each segment, train an auto-encoder for each task using the current population data to learn a latent representation.

- Map parent solutions from a source task to the latent space of a target task using the respective encoders and decoders to create transfer offspring.

- Execute this training and transfer at the start of generations

g = 0, G/S, 2G/S, ....

- Divide the total number of generations,

- Smooth PAE Phase (Continuous Refinement):

- In every generation, utilize the

Eeliminated solutions from the environmental selection. - Use these solutions to perform incremental, online updates to the auto-encoder models, facilitating gradual domain refinement.

- In every generation, utilize the

- Evolutionary Operations: For each task, generate additional offspring using standard evolutionary operators (e.g., crossover, mutation).

- Evaluation and Selection: Evaluate all offspring (both normally generated and transferred) on their respective tasks. Perform environmental selection to choose survivors for the next generation.

- Termination Check: If

t < G, sett = t + 1and go to Step 2. Otherwise, output the final solutions.

Protocol 2: Multi-Dimensional Scaling for Latent Space Alignment (MFEA-MDSGSS)

This protocol is designed for tasks with differing or high-dimensional search spaces, where direct transfer is prone to failure [7].

Workflow Overview:

Procedure:

- Subspace Construction: For each task

T_i, sample a set of high-performing solutions from its population. Apply Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) to these samples to construct a low-dimensional subspaceS_ithat preserves the pairwise distances of the original data. The dimensionality ofS_ican be user-defined or determined by an eigenvalue threshold. - Linear Mapping Learning: For a pair of tasks

T_i(source) andT_j(target), use Linear Domain Adaptation (LDA). The goal is to learn a linear transformation matrixWthat minimizes the distribution discrepancy between the aligned subspacesS_iandS_j. - Solution Transfer:

- Select a high-quality solution

x_ifromT_i. - Project

x_iinto its latent subspace:z_i = Encoder_i(x_i). - Map the latent vector to the target subspace:

z_j' = W * z_i. - Reconstruct the solution in the target task's decision space:

x_j' = Decoder_j(z_j').

- Select a high-quality solution

- Golden Section Search (GSS) Refinement: To prevent premature convergence, the mapped solution

x_j'is not directly injected. Instead, a GSS-based linear mapping is applied betweenx_j'and an existing solution fromT_jto explore a more promising region, generating the final transfer offspring. - Integration: The generated offspring is evaluated on

T_jand enters its population for subsequent selection.

Protocol 3: Collaborative Bi-Space Knowledge Transfer for Multi-Objective Problems

This protocol, based on CKT-MMPSO, explicitly leverages knowledge from both search and objective spaces, which is critical for balancing convergence and diversity in multi-objective optimization [9].

Procedure:

- Bi-Space Knowledge Reasoning (bi-SKR):

- Search Space Knowledge (

K_s): For a target particle, identify its nearest neighbors in the search space from both its own task and other tasks.K_scaptures the distribution information of high-fitness regions. - Objective Space Knowledge (

K_o): Analyze the historical flight trajectories (evolutionary paths) of particles.K_oencapsulates successful convergence behaviors and diversity maintenance patterns.

- Search Space Knowledge (

- Information Entropy-based Stage Division (IECKT):

- Calculate the information entropy of the population's distribution in the objective space.

- Divide the evolutionary process into three stages based on entropy:

- High Entropy (Early Stage): Population is dispersed. Prioritize

K_oto strengthen convergence. - Medium Entropy (Middle Stage): Balance the use of

K_sandK_o. - Low Entropy (Late Stage): Population is concentrated. Prioritize

K_sto introduce diversity and escape local optima.

- High Entropy (Early Stage): Population is dispersed. Prioritize

- Adaptive Knowledge Transfer: Based on the identified stage, adaptively select and combine

K_sandK_oto generate guiding exemplars for the particle swarm's velocity update. This results in three distinct transfer patterns applied collaboratively across the optimization run.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Algorithmic Components and Their Functions

| Tool/Component | Type/Class | Primary Function in KT | Key Configuration Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|