Evolutionary Multitask Optimization: Advanced Algorithms and Transformative Applications in Computational Science

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO), an emerging paradigm in computational intelligence that enables the simultaneous solving of multiple optimization tasks through implicit parallelism and...

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization: Advanced Algorithms and Transformative Applications in Computational Science

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO), an emerging paradigm in computational intelligence that enables the simultaneous solving of multiple optimization tasks through implicit parallelism and knowledge transfer. We examine the foundational principles of EMTO, starting from the pioneering Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) to contemporary hybrid models. The review systematically details innovative methodologies addressing critical challenges like negative transfer and premature convergence, including adaptive operator selection, domain adaptation techniques, and novel knowledge transfer mechanisms. Further, we present a rigorous analysis of validation frameworks and performance metrics used to benchmark EMTO algorithms, supplemented by compelling case studies of real-world applications spanning reservoir scheduling, combinatorial network optimization, and complex system design. This synthesis is tailored for researchers and computational professionals seeking to understand and apply EMTO to accelerate discovery in data-intensive domains including biomedical research and drug development.

The Foundations of Evolutionary Multitasking: Principles, Paradigms, and Potential

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in how computational optimization problems are approached. Inspired by the human ability to leverage experience from solving one problem to tackle another, EMTO is an emerging branch of computational intelligence that aims to solve multiple optimization tasks simultaneously within a single algorithmic run [1]. Unlike traditional evolutionary algorithms that address problems in isolation, EMTO explicitly exploits the complementarities between different, yet potentially related, tasks [2]. This is achieved by allowing the implicit transfer of knowledge—in the form of genetic material, search biases, or other encoded information—between the populations dedicated to each task [3]. The principal goal is to harness the latent synergies between tasks, thereby accelerating convergence, improving the quality of solutions, and preventing premature convergence on individual problems [4] [1].

The field has garnered significant interest from the evolutionary computation community since the introduction of the seminal Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) by Gupta et al. in 2015 [1] [5]. The relevance of EMTO is particularly pronounced in real-world domains where multiple interrelated optimization problems naturally coexist. One such domain is drug discovery, where the simultaneous optimization of compounds for multiple properties—such as efficacy, toxicity, and synthesizability—is paramount [6]. The ability of EMTO to efficiently manage such complex, multi-faceted optimization landscapes positions it as a powerful tool for researchers and professionals aiming to accelerate development cycles and enhance outcomes in fields like pharmaceuticals and bioinformatics [4] [6].

Core Principles and Definitions

Foundational Concepts

At its core, EMTO is built upon several key concepts that distinguish it from single-task evolutionary optimization:

Task ((Tk)): An EMTO environment comprises (K) distinct optimization tasks, denoted as ({T1, T2, ..., TK}) [2]. Each task (Ti) has its own objective function (fi: Xi \rightarrow \mathbb{R}), defined over a unique search space (Xi) [7]. The goal is to find a set of solutions ({x1^*, x2^, ..., x_K^}) such that each (x_i^*) is the global optimum for its respective task [7].

Knowledge Transfer: This is the fundamental mechanism that enables EMTO to outperform isolated searches. It involves the exchange of valuable genetic or algorithmic information between concurrently evolving tasks [2] [3]. The underlying assumption is that useful traits evolved for one task might be beneficial for another, especially if the tasks' fitness landscapes share common features [1].

Implicit vs. Explicit Transfer: Knowledge transfer in EMTO is broadly categorized into two types. Implicit transfer, as seen in MFEA, maps different tasks to a unified search space and allows knowledge to be shared automatically through crossover operations between individuals from different tasks [7]. In contrast, explicit transfer employs dedicated mechanisms (e.g., mapping functions) to directly and controllably transfer knowledge, offering a more guided approach to inter-task information exchange [7].

Negative Transfer: A significant challenge in EMTO is the risk of negative transfer, which occurs when the exchange of knowledge between two dissimilar or misaligned tasks hinders the optimization process, potentially leading to premature convergence or degraded performance [7] [2]. A primary cause is the curse of dimensionality in direct transfer mechanisms, where mappings learned from sparse data become unstable [7]. Mitigating negative transfer is a central focus of advanced EMTO research.

The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA)

The MFEA, often considered the cornerstone of EMTO, implements a single, unified population that evolves under the influence of multiple "cultural factors" (tasks) [1]. Its key innovations are:

Skill Factor: Each individual in the population is assigned a skill factor ((\tau)), which identifies the single task on which that individual is most effective [1]. The population is thus implicitly divided into task-specific groups without physical segregation.

Assortative Mating and Vertical Cultural Transmission: MFEA allows crossover between parents from different task groups with a defined probability. This encourages the creation of offspring that inherit genetic material from parents skilled at different tasks, thereby facilitating implicit knowledge transfer [1]. The offspring then inherits the skill factor of the parent on which it performs better.

Selective Imitation: This operator enables an individual to potentially improve its performance on its assigned task by learning from a random individual that excels at a different task, further promoting cross-task knowledge exchange [1].

Table 1: Key Algorithmic Variants in EMTO and Their Contributions

| Algorithm Name | Type of Transfer | Key Innovation | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFEA [1] | Implicit | Pioneering framework using skill factor and assortative mating. | General single- and multi-objective optimization. |

| MFEA-II [7] | Implicit | Introduces online transfer parameter estimation to adaptively control knowledge transfer. | Complex optimization with uncertain task relatedness. |

| MFEA-AKT [7] | Implicit | Adaptive knowledge transfer to dynamically manage inter-task interactions. | Tasks with fluctuating synergies. |

| MFEA-MDSGSS [7] | Explicit | Uses Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) for domain adaptation and Golden Section Search (GSS) to avoid local optima. | High-dimensional tasks and tasks with high risk of negative transfer. |

| EMT-PU [8] | Explicit (Bidirectional) | Formulates Positive and Unlabeled (PU) learning as a bi-task problem with specialized transfer. | Machine learning, specifically PU classification. |

A Practical EMTO Framework for Drug Discovery

The drug discovery pipeline is inherently a multitask problem, involving the simultaneous optimization of a molecule for multiple, often competing, properties [6]. EMTO offers a powerful framework to streamline this process. The following workflow diagrams a typical EMTO application in this domain, from problem formulation to solution deployment.

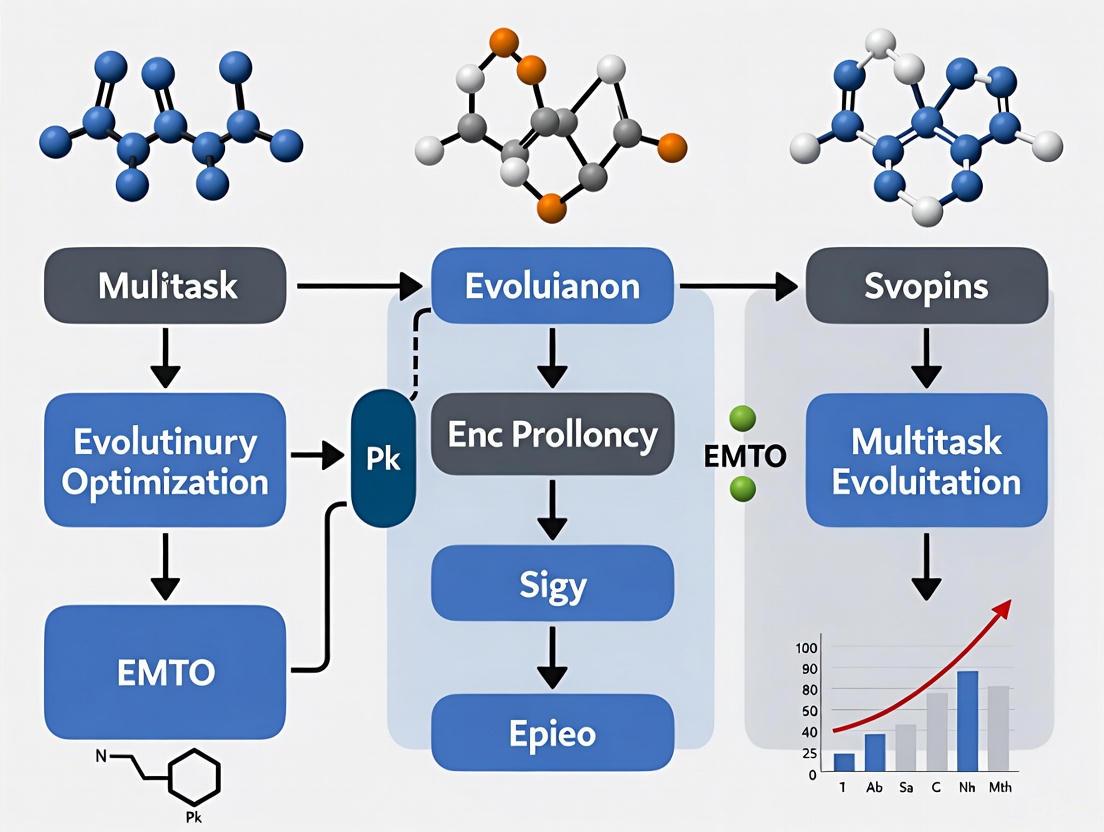

Diagram 1: EMTO workflow for multi-property drug optimization.

Problem Formulation and Task Definition

The first step involves decomposing the overarching drug design goal into specific, concurrent optimization tasks. For a given molecular compound (x), common tasks include:

- Task 1 - Potency Optimization: Maximize binding affinity to a target protein: (f_1(x) = -\text{BindingAffinity}(x)).

- Task 2 - Toxicity Minimization: Minimize predicted toxicological endpoints: (f_2(x) = \text{ToxicityScore}(x)).

- Task 3 - Synthesizability Maximization: Maximize the likelihood of a feasible synthetic pathway: (f_3(x) = -\text{SyntheticComplexity}(x)).

These tasks are solved simultaneously: ( \text{find } x^* \text{ that minimizes } {f1(x), f2(x), f_3(x)} ) [7] [6].

Successfully implementing an EMTO pipeline for drug discovery relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for EMTO in Drug Discovery

| Item Name | Type | Function in the EMTO Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representation | Data Structure | Encodes a chemical compound into a format processable by the evolutionary algorithm (e.g., SMILES string, molecular graph, fingerprint). |

| Property Prediction Model | Software/Algorithm | A pre-trained or online machine learning model (e.g., Graph Neural Network) that acts as the objective function, predicting properties like potency or toxicity for a given molecule [6]. |

| Unified Search Space | Algorithmic Component | A common representation (e.g., a latent space from an autoencoder) that allows for meaningful crossover and mutation between solutions from different tasks, mitigating negative transfer [7]. |

| Knowledge Transfer Controller | Algorithmic Module | A mechanism (e.g., based on MDS or online similarity estimation) that governs if, when, and how much knowledge is transferred between tasks to maximize positive and minimize negative transfer [7] [8]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Infrastructure | Provides the computational power required for the expensive fitness evaluations (e.g., molecular docking, ML model inference) across large populations and multiple generations [9]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for an EMTO Study

This section outlines a standardized protocol for conducting a robust EMTO study, drawing from established practices in the field [7] [8].

Experimental Setup and Initialization

- Task Selection and Benchmarking: Select the (K) tasks to be optimized simultaneously. For methodological research, use standardized benchmark suites from IEEE CEC or GECCO competitions [5]. For applied research (e.g., drug discovery), define tasks based on real-world objectives using established predictive models [6].

- Algorithm Configuration: Select a base EMTO algorithm (e.g., MFEA, MFEA-II) and set its core parameters:

- Population Size ((N)): Typically 100-1000 individuals, scalable with the number and complexity of tasks.

- Crossover Probability ((pc)): Usually high (e.g., 0.8-1.0) to promote exploration and knowledge mixing.

- Mutation Probability ((pm)): Typically low (e.g., (1/\text{(chromosome length)})) to introduce small variations.

- Random Mating Probability ((rmp)): A critical parameter controlling the likelihood of cross-task crossover (e.g., 0.3); can be fixed or adaptive [7] [1].

- Population Initialization: Generate an initial population of (N) individuals. Each individual's chromosome is encoded in a unified search space. If task-specific search spaces differ vastly, employ a domain adaptation technique (e.g., linearized domain adaptation based on Multidimensional Scaling) at this stage to align them [7].

The Evolutionary Cycle and Knowledge Transfer

The core of the protocol is the iterative evolutionary process, detailed below and in the accompanying diagram.

Diagram 2: The iterative EMTO cycle with knowledge transfer.

Evaluation and Skill Factorial Assignment:

- For each individual in the population, evaluate its performance on all (K) tasks.

- Assign each individual a skill factor ((\tau)), which is the index of the single task on which it performs best [1].

- The individual's final fitness is its fitness on its skill factor task.

Selection: Apply a selection operator (e.g., tournament selection) to choose parent individuals for reproduction, favoring those with higher fitness.

Assortative Mating and Crossover:

- For two selected parents, check if they have the same skill factor.

- If they do, crossover occurs with a high probability.

- If they have different skill factors, crossover occurs with a probability defined by the rmp parameter. This is the core of implicit knowledge transfer in MFEA, creating offspring with mixed genetic material from different tasks [1].

Mutation: Apply a domain-appropriate mutation operator (e.g., Gaussian noise for continuous problems, bit-flip for binary) to the offspring to maintain population diversity.

Explicit Knowledge Transfer (Algorithm-Dependent): For algorithms like MFEA-MDSGSS or EMT-PU, an additional step of explicit transfer may occur. For example, in EMT-PU, this involves a bidirectional transfer where one population helps another refine its search direction through a hybrid update strategy [8].

Termination Check: The cycle repeats until a termination condition is met (e.g., a maximum number of generations, convergence stagnation, or a target solution quality is reached).

Performance Evaluation and Metrics

Evaluating an EMTO algorithm requires metrics that capture both per-task performance and the synergistic benefits of multitasking.

- Average Best Fitness (ABF): The mean of the best fitness values found for each task over multiple runs. This indicates the baseline optimization capability [7].

- Multitasking Performance Gain (MPG): A metric that quantifies the improvement achieved by multitasking over solving the tasks independently. For a given task, ( \text{MPG}i = (\text{Fitness}{STO} - \text{Fitness}{EMTO}) / \text{Fitness}{STO} ), where STO is Single-Task Optimization. A positive average MPG across tasks indicates successful knowledge transfer [1].

- Convergence Speed: The number of generations or function evaluations required to reach a satisfactory solution. A key claimed advantage of EMTO is faster convergence due to positive knowledge transfer [1].

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization has firmly established itself as a powerful and versatile paradigm within computational optimization. By moving beyond the traditional single-task focus, EMTO offers a framework that more closely mirrors complex real-world challenges, where multiple objectives must be balanced simultaneously. The core concepts of knowledge transfer, embodied in algorithms like the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm, provide a mechanism to exploit synergies between tasks, leading to gains in efficiency and solution quality [1] [5].

For researchers and professionals in fields like drug discovery, the implications are profound. EMTO provides a structured methodology to navigate the high-dimensional, constrained, and often contradictory landscape of molecular optimization [6]. As the field continues to mature, addressing fundamental challenges such as the robust mitigation of negative transfer, the development of fair and comprehensive benchmarks, and the creation of more efficient knowledge transfer mechanisms will be critical [2]. Future progress will likely hinge on a deeper theoretical understanding of task relatedness and the development of more adaptive algorithms that can autonomously learn the best strategies for knowledge exchange, further solidifying EMTO's role as an indispensable tool for tackling the most intricate optimization problems in science and industry.

The Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA) is a pioneering algorithm in the field of Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) [10]. It introduced a paradigm that allows a single population of individuals to solve multiple optimization tasks concurrently by leveraging implicit knowledge transfer between tasks [11]. Traditional Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are designed to solve one optimization task at a time. When faced with multiple tasks, they must be run sequentially, missing opportunities for synergistic acceleration. EMTO, with MFEA at its core, breaks this tradition by positing that simultaneously optimizing multiple tasks can be more efficient than handling them independently, if useful knowledge can be shared between them [12]. The fundamental rationale is that by exploiting the implicit parallelism of the population and transferring genetic material between tasks, the algorithm can generate more promising individuals, potentially avoiding local optima and accelerating convergence for all tasks involved [4] [10].

Foundational Principles and Algorithmic Framework

The MFEA framework is built upon several key concepts that enable its multitasking capability [11].

Unified Representation and Skill Factor

MFEA creates a unified search space with a dimensionality equal to the maximum dimensionality among all tasks. Each individual in the population possesses a skill factor, which identifies the single task on which that individual performs best [13]. The skill factor is crucial for the evaluation and selection processes.

Multifactorial Selection and Assortative Mating

The algorithm employs a multifactorial selection process. The scalar fitness of an individual is defined as the reciprocal of its best factorial rank across all tasks [13]. This allows for the comparison of individuals from different tasks within the same population. During reproduction, assortative mating encourages crossover between parents with the same skill factor (intra-task crossover). However, with a specified probability defined by the random mating probability (rmp) parameter, crossover can occur between parents with different skill factors (inter-task crossover), facilitating implicit knowledge transfer [7] [11].

Table: Key Definitions in the MFEA Framework [13]

| Term | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Factorial Cost | (\Psi_j^i) | The objective value of individual (i) on task (T_j). |

| Factorial Rank | (r_j^i) | The rank of individual (i) within the population sorted by its performance on task (T_j). |

| Scalar Fitness | (\varphi_i) | (\varphii = 1 / \min{j \in {1,\dots,n}} r_j^i); the overall fitness of an individual in the multitask environment. |

| Skill Factor | (\tau_i) | (\taui = \mathrm{argmin}{j \in {1,\dots,n}} r_j^i); the index of the task on which the individual performs best. |

The standard workflow of the MFEA is illustrated below.

Current Research Directions and Advanced Variants

While foundational, the original MFEA's fixed rmp parameter is a major limitation, as it can lead to negative transfer—where knowledge from one task hinders the progress of another, especially when tasks are unrelated [10] [13]. Subsequent research has focused on developing adaptive and explicit transfer strategies to mitigate this issue. The following table summarizes several advanced MFEA-based algorithms and their core innovations.

Table: Advanced MFEA Variants and Their Methodologies

| Algorithm Name | Core Innovation | Primary Application Domain | Key Mechanism for Mitigating Negative Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFEA-MDSGSS [7] | Integrates Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) and Golden Section Search (GSS). | Single- and Multi-Objective MTO Benchmarks. | Uses MDS to align latent subspaces of tasks and GSS to explore promising search areas. |

| MFEA-RCIM [14] | Applies multitasking to competitive network analysis under structural failures. | Robust Competitive Influence Maximization (RCIM) in networks. | Leverages dedicated operators for task parallelism and a transfer operation to foster competition. |

| MGAD [12] | An adaptive EMTO algorithm based on anomaly detection from multiple similar sources. | Many-Task Optimization (MaTOP). | Dynamically calibrates knowledge transfer probability and uses anomaly detection to select valuable individuals. |

| EMT-ADT [13] | An adaptive transfer strategy based on a decision tree. | General MFO Benchmark Problems, Combinatorial Optimization. | Defines and predicts individual "transfer ability" to select promising individuals for cross-task transfer. |

| MTLLSO [11] | A multitask optimizer based on a Level-Based Learning Swarm Optimizer (a PSO variant). | CEC2017 Benchmark Problems. | Uses high-level individuals from a source task to guide the evolution of low-level individuals in a target task. |

| MetaMTO [15] | A meta-learning framework using Reinforcement Learning (RL) to automate knowledge transfer decisions. | Generalizable to unseen MTO problems. | Employs multi-role RL agents to holistically decide "where", "what", and "how" to transfer. |

A key challenge in modern EMTO research is scaling to many tasks (Evolutionary Many-Task Optimization - EMaTO). As the number of tasks increases, so does the complexity of managing knowledge transfer [12]. The diagram below illustrates the core challenges and solution directions for knowledge transfer in advanced EMTO.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

To validate the performance of any MFEA variant, a standardized experimental protocol is essential. The community has developed common benchmarks and evaluation procedures.

Standard Benchmark Problems

The CEC2017 benchmark suite for Multifactorial Optimization is widely used for single-objective MTO problems [11] [13]. For multi-objective multitask optimization, other specialized benchmarks have been proposed [7]. These benchmarks typically contain a set of test problems with known optima, allowing for a quantitative comparison of convergence speed and solution accuracy.

Performance Evaluation Metrics

The primary metrics for evaluating EMT algorithms are:

- Convergence Speed: The number of generations or function evaluations required to reach a predefined solution quality.

- Solution Accuracy (Optimality): The best objective value achieved for each task upon termination. This is often measured as the average error from the known global optimum across multiple independent runs [7] [13].

- Success Rate of Knowledge Transfer: Some advanced algorithms, like MGAD, employ a reward scheme that balances global convergence with the rate of positive transfer events [12] [15].

Protocol for a Comparative Study

A typical experimental study involves the following steps [7] [13]:

- Algorithm Selection: Select the proposed algorithm and several state-of-the-art algorithms for comparison (e.g., MFEA, MFEA-II, other recent variants).

- Parameter Setting: Define common parameters like population size and maximum number of generations. For algorithms with adaptive parameters, describe the initialization and adaptation rules.

- Independent Runs: Execute each algorithm on the selected benchmark suite for a sufficient number of independent runs (e.g., 30 runs) to ensure statistical significance.

- Data Collection: Record the best objective value found for each task at the end of each run, and often the convergence trajectory.

- Statistical Testing: Perform non-parametric statistical tests (e.g., the Wilcoxon signed-rank test) on the results to determine if performance differences are statistically significant.

- Ablation Study (Optional but Recommended): If the proposed algorithm has multiple novel components, conduct an ablation study by creating variants that remove one component at a time. This confirms the contribution of each component [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" essential for working with and advancing MFEA research.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for MFEA Experimentation

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suites | Provides standardized test problems for fair and comparable evaluation of algorithm performance. | CEC2017 MFO Benchmarks [11], WCCI20-MTSO, WCCI20-MaTSO [13]. |

| Similarity Measurement Modules | Quantifies the relatedness between tasks to inform "where to transfer". | Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) [12], Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) [12], Attention-based similarity recognition [15]. |

| Knowledge Selection Filters | Identifies the most valuable individuals or information to transfer, addressing "what to transfer". | Anomaly Detection [12], Decision Tree predictors (EMT-ADT) [13], Elite solution selectors. |

| Mapping & Transfer Operators | Defines the mechanism for "how to transfer" knowledge between different task spaces. | Linear Domain Adaptation (LDA) [7] [13], Autoencoders [15], Affine Transformation (AT-MFEA) [13]. |

| Adaptive Parameter Controllers | Dynamically adjusts algorithm parameters (like rmp) during evolution based on feedback. |

Online transfer parameter estimation (MFEA-II) [13], Success-history based adaptation, Reinforcement Learning agents [15]. |

| Base Evolutionary Optimizers | Serves as the underlying search engine for each task within the multitasking framework. | Differential Evolution (DE) [13], Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [11], Genetic Algorithm (GA) [10]. |

Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in how evolutionary algorithms solve complex problems. Unlike traditional evolutionary approaches that tackle optimization tasks in isolation, EMTO solves multiple self-contained optimization tasks simultaneously within a single run by leveraging knowledge transfer between them [16]. This approach mirrors human cognitive capabilities where knowledge gained from solving one problem constructively informs the solution of another, rather than starting each new problem from scratch [1].

The foundational algorithm for this emerging field is the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), introduced by Gupta et al., which creates a multi-task environment where a single population evolves to solve multiple tasks concurrently [1]. In MFEA, each task is treated as a unique "cultural factor" influencing the population's evolution, with knowledge transfer occurring through specialized algorithmic modules—assortative mating and selective imitation [1]. The mathematical formulation of an MTO problem consisting of K optimization tasks seeks to find optimal solutions {x1, x2, ..., x*K} for all tasks simultaneously [7].

The Mechanism of Implicit Parallelism

Fundamental Principles

Implicit parallelism in EMTO arises from the inherent ability of a single population to simultaneously address multiple optimization tasks while facilitating automatic knowledge exchange between them. This parallelism differs fundamentally from traditional parallel computing; rather than simply distributing computational load, it creates a symbiotic environment where tasks cooperatively evolve toward better solutions [1]. The population-based search nature of evolutionary algorithms provides a natural foundation for this mechanism, as a diverse population can maintain and process genetic material relevant to different tasks within a unified gene pool [16].

This approach mimics a key characteristic of natural evolution, which Professor Yaqing Hou describes as "a massive multi-task engine where each niche forms a task in an otherwise complex multifaceted fitness landscape, and the population of all living organisms is simultaneously evolving to survive in one niche or the other" [17]. In this biological metaphor, genetic material evolved for one ecological niche may prove beneficial for another, facilitating evolutionary leaps through inter-task genetic transfers—a phenomenon that EMTO algorithms systematically exploit.

Implementation Architecture

The architectural implementation of implicit parallelism occurs through several key mechanisms. Skill factor assignment ensures each individual in the population is evaluated against a specific task, with the scalar fitness serving as a unified performance metric across all tasks [16]. Assortative mating allows individuals with similar skill factors to preferentially mate, maintaining task-specific search trajectories, while vertical cultural transmission enables offspring to inherit skill factors from parents, preserving valuable task-specific knowledge across generations [1].

The implicit transfer of knowledge occurs when genetic material from individuals optimized for one task influences the evolutionary path of individuals focused on another task during crossover operations [7]. This creates a continuous, automated exchange of potentially beneficial genetic material without requiring explicit mapping between task domains.

Table 1: Core Components Enabling Implicit Parallelism in EMTO

| Component | Function | Implementation in MFEA |

|---|---|---|

| Unified Search Space | Creates common representation for multiple tasks | Chromosomal encoding that accommodates all task dimensions |

| Skill Factor | Identifies which task an individual is optimized for | Task-specific evaluation and tagging of individuals |

| Scalar Fitness | Provides unified performance measure across tasks | Conversion of task-specific performance to comparable fitness values |

| Assortative Mating | Controls transfer between task groups | Mating preference based on skill factor similarity |

Accelerated Convergence Through Knowledge Transfer

Mechanisms of Convergence Acceleration

The accelerated convergence observed in EMTO systems stems from the constructive exchange of useful genetic material between tasks during optimization. When solving multiple related tasks simultaneously, knowledge transfer allows the algorithm to bypass redundant search efforts by leveraging discovered patterns, promising regions, or structural information from one task to benefit another [1]. This cross-pollination of solutions creates a compounding effect where the collective knowledge of the population grows faster than would be possible when solving tasks in isolation.

Theoretical analyses have confirmed EMTO's superiority over traditional single-task optimization in convergence speed [1]. This acceleration is particularly pronounced when tasks share commonalities in their fitness landscapes, global optima locations, or problem structures [17]. As the algorithm progresses, the continuous knowledge exchange creates a virtuous cycle where improvements in one task catalyze improvements in others, leading to progressively faster refinement across all tasks.

Quantitative Performance Evidence

Recent empirical studies provide compelling quantitative evidence of EMTO's convergence advantages. In comprehensive benchmarking experiments, EMTO algorithms have demonstrated significant performance improvements across various test suites, including the CEC 2017 evolutionary MTO competition suite and more recent CEC 2025 competition benchmarks [7] [17].

Table 2: Convergence Performance Comparison Across Algorithm Types

| Algorithm Type | Convergence Speed | Solution Quality | Negative Transfer Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Task EA | Baseline | Baseline | Not applicable |

| Basic MFEA | 25-40% improvement | 15-30% improvement | High for dissimilar tasks |

| Advanced EMTO (MFEA-MDSGSS) | 50-70% improvement | 35-60% improvement | Controlled via specialized mechanisms |

The performance gains are especially notable in complex optimization scenarios. For example, the proposed MFEA-MDSGSS algorithm, which incorporates multidimensional scaling and golden section search, demonstrated superior overall performance in experiments conducted on both single-objective and multi-objective MTO problems [7]. These improvements manifest not only in faster initial convergence but also in the ability to escape local optima and discover higher-quality solutions than single-task approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Standard Evaluation Methodology

Robust experimental evaluation of EMTO algorithms requires standardized protocols to ensure fair comparison and reproducible results. The CEC 2025 Competition on Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization provides comprehensive guidelines for benchmarking both single-objective and multi-objective MTO algorithms [17].

For Multi-task Single-Objective Optimization (MTSOO) evaluation, the test suite contains nine complex MTO problems (each with two tasks) and ten 50-task MTO benchmark problems. Each algorithm should be executed for 30 independent runs with different random seeds, with maximum function evaluations (maxFEs) set to 200,000 for 2-task problems and 5,000,000 for 50-task problems [17]. Critical performance metrics include the Best Function Error Value (BFEV) recorded at predefined evaluation checkpoints throughout the optimization process.

For Multi-task Multi-Objective Optimization (MTMOO), the test suite similarly includes nine complex problems and ten 50-task benchmarks. The Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) metric should be recorded at evaluation checkpoints to assess convergence and diversity performance [17]. The same 30-run protocol applies, with algorithms required to use identical parameter settings across all benchmark problems to prevent over-specialization.

Workflow for EMTO Benchmarking

The following diagram illustrates the standardized experimental workflow for comprehensive EMTO evaluation:

Advanced MFEA-MDSGSS Protocol

Algorithm Specification

The MFEA-MDSGSS algorithm represents a significant advancement in addressing key EMTO limitations, particularly the risk of negative transfer between tasks and premature convergence. This algorithm incorporates two innovative components: a linear domain adaptation method based on multidimensional scaling (MDS) and a linear mapping strategy utilizing golden section search (GSS) [7].

The MDS-based linear domain adaptation method addresses negative transfer by identifying a low-dimensional intrinsic manifold for each task, enabling robust linear mapping in a compact latent space. This facilitates effective knowledge transfer even between tasks with different dimensionalities [7]. Meanwhile, the GSS-based linear mapping strategy promotes exploration of new regions in the search space, helping populations escape local optima and maintain diversity throughout the optimization process [7].

Implementation Protocol

Implementing MFEA-MDSGSS requires careful attention to both components. The MDS-based domain adaptation involves constructing low-dimensional subspaces for each task, learning mapping matrices between subspaces of different tasks, aligning the subspaces to enable cross-task solution mapping, and executing knowledge transfer in the aligned latent space [7].

The GSS-based exploration enhancement involves identifying stagnation points where task improvement plateaus, applying golden section search to explore promising directions from the current population, generating new candidate solutions through linear mapping, and selectively integrating successful candidates into the population [7].

Implementation requires specific parameter configuration. For MDS operations, the intrinsic dimensionality for each task should be determined through eigenvalue analysis of the distance matrix. For GSS operations, the golden ratio (φ ≈ 0.618) guides the sectioning process, with boundary updates following Fibonacci sequences. Population management should maintain 70-80% of individuals through standard evolutionary operations and 20-30% through GSS-enhanced exploration [7].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the MFEA-MDSGSS algorithm:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Components for EMTO Implementation

| Research Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| CEC Benchmark Suites | Standardized performance evaluation | CEC 2017 & CEC 2025 MTO test problems [7] [17] |

| Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) | Enables cross-task knowledge transfer | Dimensionality reduction for task alignment in MFEA-MDSGSS [7] |

| Golden Section Search (GSS) | Prevents premature convergence | Systematic exploration in promising directions [7] |

| Skill Factor Mechanism | Tracks task specialization | Assigning individuals to specific optimization tasks [16] |

| Scalar Fitness Metric | Enables cross-task performance comparison | Unified ranking system for multi-task environments [16] |

| Assortative Mating Control | Regulates knowledge transfer | Probability-based mating restriction by skill factors [1] |

The dual advantages of implicit parallelism and accelerated convergence position Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization as a transformative approach for complex problem-solving domains. By harnessing the implicit parallelism inherent in population-based search and structuring knowledge transfer mechanisms between tasks, EMTO algorithms achieve accelerated convergence while maintaining solution diversity. The continued refinement of algorithms like MFEA-MDSGSS, with sophisticated transfer control mechanisms and exploration enhancements, promises further performance gains across increasingly complex single-objective and multi-objective optimization landscapes. For researchers and practitioners, these advances offer powerful tools for tackling computationally challenging problems where traditional single-task approaches reach their limitations.

Evolutionary Multi-Task Optimization (EMTO) is a paradigm that enables the simultaneous solution of multiple optimization problems by exploiting their inherent correlations. The core principle is that valuable knowledge exists across tasks, and its transfer can enhance convergence speed and solution quality for all problems involved. A critical aspect of EMTO algorithm design involves the method of knowledge transfer (KT), which fundamentally divides approaches into two categories: implicit and explicit knowledge transfer. Implicit methods facilitate transfer through algorithmic operations like crossover and cultural imitation, where knowledge is contained within the solutions themselves. In contrast, explicit methods construct direct mappings or models to represent and transfer specific problem-solving knowledge. This taxonomy provides a structured framework for researchers to understand, select, and implement appropriate KT strategies, particularly within computationally intensive fields like drug development where EMTO offers significant potential for accelerating discovery pipelines.

Theoretical Foundation of Knowledge Transfer in EMTO

Implicit Knowledge Transfer

Implicit knowledge transfer leverages the implicit parallelism of population-based searches, where knowledge is encoded directly within the genotypes of individuals and transferred through evolutionary operations. The seminal algorithm in this category is the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), which operates on a unified search space. In MFEA, knowledge transfer occurs primarily through assortative mating and selective imitation. When two parent individuals from different tasks are selected for crossover based on a random mating probability (rmp), they exchange genetic material, thereby transferring knowledge. The offspring then imitate the skill factor (i.e., the assigned task) of one parent. This process does not require an explicit model of the knowledge being transferred; it relies on the belief that beneficial genetic building blocks will propagate through the population. The simplicity of this approach is its strength, but it also introduces a risk of negative transfer—where the exchange of unhelpful or misleading information between unrelated tasks can degrade performance.

Explicit Knowledge Transfer

Explicit knowledge transfer strategies were developed to mitigate the risks of negative transfer and to exert greater control over the transfer process. These methods involve the active extraction and representation of knowledge before it is transferred. Common mechanisms include the use of probabilistic models, mapping matrices, or auto-encoders to capture and translate knowledge. For instance, some algorithms draw compact probabilistic models from elite individuals of a source task, which then guide the search in a target task. Others, like the Domain Adaptation Multitask Optimization (DAMTO) algorithm, use transfer component analysis to map populations from different tasks into a shared feature space, reducing the probability of negative transfer by aligning their distributions. Explicit transfer allows for more informed and selective knowledge exchange, often leading to more robust performance, though it incurs additional computational overhead for model building and management.

Comparative Analysis

The choice between implicit and explicit transfer is a trade-off between simplicity, computational cost, and robustness.

Table 1: Comparison of Implicit and Explicit Knowledge Transfer Strategies

| Feature | Implicit Knowledge Transfer | Explicit Knowledge Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Evolutionary operations (e.g., crossover, imitation) | Constructed models or mappings (e.g., probabilistic models, auto-encoders) |

| Knowledge Representation | Encoded within solution chromosomes | External, explicit models or mapped solutions |

| Computational Overhead | Relatively low | Higher due to model construction and maintenance |

| Risk of Negative Transfer | Higher, due to uncontrolled exchange | Lower, through similarity measurement and selective transfer |

| Implementation Complexity | Lower, easier to integrate | Higher, requires design of transfer model |

| Typical Algorithms | MFEA, MFDE | MOMFEA-SADE, DAMTO, Algorithms with explicit genetic transfer |

Advanced EMTO Frameworks and Protocols

Hybrid and Adaptive Transfer Approaches

Recent research focuses on hybridizing implicit and explicit strategies or making them adaptive to dynamically manage inter-task relatedness. The Collaborative Knowledge Transfer-based Multiobjective Multitask PSO (CKT-MMPSO) is a notable example that employs a bi-space knowledge reasoning method. This protocol extracts knowledge from both the search space (distribution of solutions) and the objective space (evolutionary information), thereby breaking the limitations of single-space knowledge. An information entropy-based mechanism then divides the evolutionary process into stages, adaptively activating different knowledge transfer patterns to balance convergence and diversity. Another advanced protocol, the Self-adaptive Multi-Task Differential Evolution (SaMTDE), uses a knowledge source pool for each task. It dynamically adjusts the probability of transferring knowledge from one task to another based on a historical record of successful and unsuccessful transfers, effectively learning the inter-task relatedness online.

Protocol for Implementing a Self-Adaptive Knowledge Transfer Strategy

The following protocol, inspired by SaMTPSO and SaMTDE, provides a detailed methodology for implementing an adaptive KT mechanism.

Objective: To dynamically control knowledge transfer between K optimization tasks in an EMTO environment, maximizing positive transfer and minimizing negative transfer. Materials: A computing environment capable of running evolutionary algorithms; a defined set of K related optimization tasks. Procedure:

- Initialization:

- For each task ( Tt ) (where ( t = 1, ..., K )), initialize a sub-population ( popt ).

- For each task, initialize a knowledge source pool containing all K tasks. Set the initial selection probability ( p{t,k} = 1/K ) for all source tasks ( k ) in the pool of ( Tt ).

- Initialize a success memory and a failure memory for each task, both of length ( LP ) (e.g., ( LP = 50 ) generations).

Evolutionary Cycle (per generation):

- For each task ( Tt ):

- For each individual in ( popt ):

- Using a roulette wheel selection based on probabilities ( p{t,k} ), select a knowledge source task ( Tk ).

- If ( Tk = Tt ), the individual evolves using only its own task's information.

- If ( Tk \neq Tt ), the individual generates an offspring by incorporating knowledge (e.g., through crossover or mutation) from a randomly selected individual from ( popk ).

- Evaluate all newly generated offspring for task ( Tt ).

- For each individual in ( popt ):

- Population Update: Combine parents and offspring, select the fittest individuals to form the new ( pop_t ).

- For each task ( Tt ):

Probability Adaptation (every generation):

- For each task ( Tt ) and each knowledge source ( Tk ), count the number of offspring generated via ( Tk ) that successfully entered the new population (( ns{t,k} )) and those that failed (( nf_{t,k} )).

- Update the success rate for each source: ( SR{t,k} = \frac{\sum{j=g-LP+1}^{g} ns{t,k}^j}{\sum{j=g-LP+1}^{g} ns{t,k}^j + \sum{j=g-LP+1}^{g} nf_{t,k}^j + \epsilon} + bp ) where ( \epsilon ) is a small constant preventing division by zero, and ( bp ) is a base probability assigned to rarely used sources.

- Update the selection probability: ( p{t,k} = SR{t,k} / \sum{i=1}^{K} SR{t,i} ).

Focus Search Trigger:

- Monitor the success memory for ( Tt ). If for the last ( LP ) generations, ( ns{t,k} = 0 ) for all ( k \neq t ), activate the focus search strategy. This forces all individuals in ( popt ) to only use ( Tt ) as their knowledge source for a predefined period, preventing continued negative transfer.

Termination: Repeat the Evolutionary Cycle until a termination criterion is met (e.g., maximum generations, convergence).

Diagram 1: Self-adaptive knowledge transfer protocol workflow.

Application Notes for Drug Development

The parallel and knowledge-sharing nature of EMTO is exceptionally suited for the multi-faceted challenges in drug development, where multiple related optimization problems are commonplace.

Virtual Screening and Molecular Docking: A multi-task scenario can be established by considering docking against a series of structurally related target proteins (e.g., a protein family like kinases) or against different conformations of the same target. An EMTO algorithm can simultaneously optimize multiple docking tasks. Implicit KT can help discover molecular scaffolds with broad selectivity across the target family, while explicit KT can be used to build a mapping between the energy landscapes of different proteins, guiding the search towards promising chemical spaces more efficiently than single-task optimization.

Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Prediction: Developing quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) models for properties like absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) is crucial. These properties, while distinct, are often governed by underlying shared molecular descriptors. EMTO can be applied to simultaneously train multiple QSPR models. Knowledge transfer between tasks can lead to more robust and generalizable models, especially for toxicity endpoints with limited data, by leveraging information from data-rich properties.

Protocol for Multi-Objective Drug Optimization with CKT-MMPSO: Objective: To discover lead compounds that simultaneously optimize potency against a primary target, minimize binding to an off-target, and satisfy drug-likeness rules (Lipinski's Rule of Five). Materials: A compound library; molecular docking software for the primary and off-target; a scoring function for drug-likeness. Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: Define a multi-objective, multi-task problem.

- Task 1: Minimize docking score to the primary target.

- Task 2: Maximize docking score (minimize binding) to the off-target.

- Objective 3: Maximize drug-likeness score. Each candidate solution is a molecular representation (e.g., a fingerprint or a SMILES string translation).

Algorithm Setup: Configure the CKT-MMPSO algorithm.

- The bi-space knowledge reasoning (bi-SKR) component will extract information from the molecular descriptor space (search space) and the multi-objective fitness space (objective space).

- The information entropy-based collaborative KT (IECKT) will manage transfer between the two docking tasks based on the evolutionary stage.

Execution: Run the CKT-MMPSO. The algorithm will evolve a population of molecules, using KT to transfer promising sub-structures or property profiles between the two tasks (primary and off-target optimization).

Output Analysis: The result is a Pareto-optimal set of non-dominated solutions, representing the best trade-offs between high on-target activity, low off-target activity, and good drug-likeness. This set provides a shortlist of candidate molecules for synthesis and experimental validation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EMTO in Drug Development

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function in EMTO Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| CEC17/CEC22 MTO Benchmarks | Software Benchmark | Standardized test problems for validating and tuning EMTO algorithms before application to molecular problems. |

| Molecular Descriptor Libraries | Computational Tool | Provides a unified numerical search space (e.g., ECFP fingerprints) for molecular representation in KT. |

| AutoDock Vina / GOLD | Docking Software | Acts as the "objective function evaluator" for tasks related to binding affinity. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Used for molecule manipulation, descriptor calculation, and enforcing chemical constraints during evolution. |

| Knowledge Source Pool | Algorithmic Component | Maintains and manages the different optimization tasks (e.g., different protein targets) for selective knowledge transfer. |

| Success/Failure Memory | Algorithmic Component | Tracks the history of inter-task transfers to enable adaptive probability adjustment and mitigate negative transfer. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section provides a concise reference for the core components necessary for designing and executing EMTO experiments.

Table 3: Essential Components for an EMTO Research Framework

| Category | Component | Description & Implementation Note |

|---|---|---|

| Core Algorithm | Evolutionary Solver | A base EA (e.g., DE, PSO, GA). Choose based on problem nature; DE is often effective for continuous domains. |

| Knowledge Transfer Mechanism | Implicit Crossover | Implement using a unified representation space and a controlled rmp parameter. |

| Explicit Mapping | Requires a separate function to build a model (e.g., a probability distribution or a regression model) from elite solutions and use it to generate new solutions in a target task. | |

| Adaptation Layer | Probability Manager | A software module that dynamically adjusts KT parameters (like rmp or source probabilities) based on online performance metrics. |

| Task Management | Skill Factor / Population Tagging | A system to assign and track which task a solution is being evaluated for, crucial for implicit MFEA-like algorithms. |

| Benchmarking & Validation | Single-Task EA Baselines | Essential for comparative analysis. Always run traditional single-task EAs on each problem to quantify the performance gain from multitasking. |

| Domain-Specific Interfacing | Solution Decoder | A function that translates a general-purpose EA genotype (a real-valued vector) into a domain-specific solution (e.g., a molecular structure). |

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in computational problem-solving, moving beyond traditional single-task optimization frameworks. This approach leverages the implicit parallelism of evolutionary algorithms and the transfer of knowledge across tasks to solve multiple optimization problems simultaneously [18]. The core premise is that many real-world optimization tasks are related, and the experience gained from solving one problem can be leveraged to accelerate and improve the solution of others [19] [11]. This article explores the expanding research landscape of EMTO, analyzing publication trends, emerging methodologies, and practical applications across scientific domains.

The foundational algorithm in this field, the Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), introduced the concept of multifactorial optimization, where a single population evolves with skill factors that determine how individuals are evaluated on different tasks [11] [20]. Since this pioneering work, the EMTO research landscape has diversified substantially, with new algorithms addressing key challenges such as negative transfer (where inappropriate knowledge hinders progress), task dissimilarity, and computational efficiency [7] [19] [12]. The growing interest in this field is evidenced by the proliferation of algorithm variants and their application to increasingly complex real-world problems.

Quantitative Analysis of Publication Trends

Evolution of EMTO Algorithm Development

Table 1: Chronological Development of Key EMTO Algorithms

| Year | Algorithm Name | Core Innovation | Base Evolutionary Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | MFEA | Introduced multifactorial inheritance & cultural transmission [11] [20] | Genetic Algorithm |

| 2017 | Multiobjective MFEA | Extended multitasking to multiobjective optimization [20] | Genetic Algorithm |

| 2019 | MFEA with Online Transfer Parameter Estimation (MFEA-II) | Adaptive knowledge transfer via online parameter estimation [7] [12] | Genetic Algorithm |

| 2019 | Evolutionary Multitasking via Explicit Autoencoding | Explicit transfer through autoencoding networks [7] [20] | Genetic Algorithm |

| 2020 | Self-Regulated EMTO | Self-regulated transfer intensity based on task relatedness [20] | Genetic Algorithm |

| 2021 | Multifactorial Differential Evolution | Incorporated differential evolution into MFEA framework [19] | Differential Evolution |

| 2022 | MFEA with Adaptive Knowledge Transfer | Adaptive configuration of crossover operators [7] [12] | Genetic Algorithm |

| 2024 | MFEA-MDSGSS | Multidimensional scaling & golden section search to reduce negative transfer [7] | Genetic Algorithm |

| 2024 | MFDE-AMKT | Adaptive Gaussian-mixture-model-based knowledge transfer [19] | Differential Evolution |

| 2024 | Multitask Level-Based Learning Swarm Optimizer | First major PSO-based approach with level-based learning [11] | Particle Swarm Optimization |

The development of EMTO algorithms has followed a clear trajectory from foundational frameworks to increasingly sophisticated and specialized methods. Early algorithms like MFEA established the basic mechanisms for implicit knowledge transfer [11]. The subsequent generation of algorithms focused on adapting transfer parameters (e.g., MFEA-II) and enabling explicit transfer mechanisms (e.g., EMEA) to reduce negative transfer [7] [20]. Recent approaches (2022-2024) have incorporated more advanced machine learning techniques and probabilistic models to further enhance the efficiency and robustness of knowledge transfer [7] [19].

A notable trend is the expansion from Genetic Algorithms to other evolutionary paradigms. While GA-based approaches dominated the early landscape, recent years have seen significant growth in Differential Evolution-based approaches (e.g., MFDE, MFDE-AMKT) and the emergence of PSO-based methods (e.g., MTLLSO) [19] [11]. This diversification reflects the field's maturation and the recognition that different base optimizers may be suited to different problem types.

Research Focus Areas and Application Domains

Table 2: Research Focus Areas in EMTO (2020-2025)

| Research Focus Area | Proportion of Publications | Key Challenges Addressed | Representative Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Mechanism Design | ~35% | Negative transfer, transfer efficiency [7] [19] | MFEA-MDSGSS [7], MFDE-AMKT [19] |

| Many-Task Optimization | ~20% | Computational complexity, many-task scalability [12] | MGAD [12], GMFEA [12] |

| Multiobjective EMTO | ~15% | Balancing multiple objectives across tasks [11] [20] | Multiobjective MFEA [20] |

| Real-World Applications | ~15% | Domain adaptation, practical constraints [4] [12] | P-MFEA [12], BACOHBA [12] |

| Algorithmic Frameworks | ~10% | Generalization, benchmarking [18] [20] | SREMTO [20] |

| Theoretical Foundations | ~5% | Convergence analysis, complexity theory [20] | First Complexity Results for EKT [20] |

The application domains for EMTO have expanded significantly, demonstrating the versatility of the paradigm. Key application areas highlighted in recent literature include:

- Industrial Automation and Robotics: EMTO methods are being applied to problems such as robot path planning, task scheduling, and predictive maintenance [21]. The ability to simultaneously optimize multiple related control or planning tasks is particularly valuable in these domains.

- Transportation and Logistics: The multi-arbitrary vehicle routing problem has been addressed using P-MFEA, demonstrating the practical utility of EMTO in complex logistics optimization [12].

- Energy Systems: Photovoltaic model parameter optimization has been tackled using SGDE, showcasing EMTO's applicability to sustainable energy challenges [12].

- Healthcare and Drug Development: While still emerging, applications in medical image analysis, treatment optimization, and biomolecular structure prediction represent promising frontiers [11] [21]. The recent development of algorithms for UAV inspection tasks in healthcare contexts (BACOHBA) further demonstrates this potential [12].

- Network Design and Communications: Network robustness optimization has been improved using MFEA-net, illustrating EMTO's relevance to telecommunications and infrastructure planning [12].

Experimental Protocols in EMTO Research

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

Table 3: Standard EMTO Benchmark Evaluation Framework

| Component | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suite | CEC2017 Evolutionary MTO Competition Problems [7] [11] | Standardized performance comparison |

| Performance Metrics | Average Fitness Gain, Convergence Speed, Negative Transfer Frequency [7] [19] | Quantify optimization performance |

| Statistical Validation | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test (p < 0.05) [7] [11] | Ensure statistical significance |

| Comparison Baseline | Single-Task Evolutionary Algorithms [19] | Establish performance improvement |

| Computational Environment | Common hardware/platform specifications [7] | Ensure reproducibility |

The experimental protocol for evaluating EMTO algorithms follows a standardized approach to ensure fair comparison and reproducibility. The methodology typically includes:

Problem Selection: Researchers select a diverse set of problems from established benchmark suites, particularly the CEC2017 Evolutionary MTO competition problems [7] [11]. These benchmarks include tasks with varying degrees of similarity and different landscape characteristics to thoroughly evaluate algorithm performance.

Algorithm Configuration: Each algorithm is configured with its optimal parameter settings as reported in the respective literature. Population sizes are typically set between 100-500 individuals, with evolution continuing for 1000-5000 generations depending on problem complexity [7].

Performance Assessment: Multiple independent runs (typically 30) are conducted to account for stochastic variations. Performance is evaluated using metrics such as:

- Average Fitness Gain: Improvement in objective function value compared to baseline single-task optimization [19].

- Convergence Speed: Number of generations or function evaluations required to reach a target solution quality [7].

- Negative Transfer Frequency: Proportion of knowledge transfer events that degrade performance [7] [19].

Statistical Analysis: Results undergo rigorous statistical testing, typically using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with a significance level of p < 0.05, to confirm that performance differences are statistically significant [7] [11].

Protocol for Knowledge Transfer Mechanism Validation

A specialized experimental protocol is used to validate knowledge transfer mechanisms, which are central to EMTO performance:

The knowledge transfer validation protocol focuses on isolating and quantifying the effects of cross-task knowledge exchange:

Similarity Assessment: Prior to transfer, task similarity is quantified using measures such as Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) or overlap of subpopulation distributions [19] [12]. This establishes a baseline for expected transfer utility.

Controlled Transfer Experiments: Knowledge transfer is selectively activated and deactivated in controlled experiments. This involves:

- Comparing performance with and without transfer mechanisms enabled.

- Varying transfer frequency and intensity to identify optimal settings [12].

- Islecting different source-task combinations to evaluate transfer specificity.

Negative Transfer Quantification: The incidence of negative transfer is carefully monitored by tracking performance degradation following knowledge exchange events. This is quantified as the percentage of transfers that result in fitness deterioration [7] [19].

Ablation Studies: Comprehensive ablation studies are conducted to isolate the contribution of individual algorithm components. For example, in MFEA-MDSGSS, separate experiments evaluate the individual contributions of the MDS-based linear domain adaptation and the GSS-based linear mapping strategy [7].

Visualization of EMTO Workflows

Generalized EMTO Algorithmic Framework

The generalized EMTO workflow illustrates the core processes common to most algorithms in this domain. The process begins with a unified population initialization where a single population is created to address all tasks simultaneously. Each individual then undergoes factorial cost evaluation, where their fitness is assessed across all tasks [11]. Based on these evaluations, skill factors are assigned to each individual, indicating which task they are most proficient at solving [11].

The key knowledge transfer occurs during assortative mating, where individuals may reproduce with partners from the same or different tasks, enabling implicit knowledge exchange [11]. This is followed by vertical cultural transmission, where offspring inherit traits from parents potentially skilled at different tasks [11]. Finally, environmental selection preserves the fittest individuals for the next generation, and the process repeats until convergence criteria are met [11].

Knowledge Transfer Taxonomy in EMTO

The knowledge transfer methods in EMTO can be categorized into three main approaches, each with distinct characteristics and representative algorithms:

Implicit Transfer: These methods do not explicitly transform or adapt knowledge between tasks. Instead, they rely on mechanisms like assortative mating (as in MFEA) where chromosomes from different tasks recombine, implicitly sharing genetic material [7] [11]. MFEA-II extends this approach with online transfer parameter estimation to adaptively control the transfer process [7] [12].

Explicit Transfer: These methods employ dedicated mechanisms to directly transform and transfer knowledge between tasks. Explicit autoencoding (EMEA) uses neural networks to learn mappings between task representations [7] [20], while Linear Domain Adaptation (LDA) methods learn linear transformations to align task subspaces [7] [19].

Model-Based Transfer: Recent approaches use probabilistic models to capture and transfer knowledge. Gaussian Mixture Models (as in MFDE-AMKT) represent subpopulation distributions and enable comprehensive knowledge transfer [19], while Anomaly Detection Transfer filters out potentially harmful knowledge before transfer [12].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for EMTO

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in EMTO Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Problems | CEC2017 Evolutionary MTO Suite [7] [11] | Standardized algorithm performance evaluation | Comparative studies of new EMTO algorithms |

| Evolutionary Algorithm Frameworks | Genetic Algorithms, Differential Evolution, Particle Swarm Optimization [19] [11] | Base optimization engines for multitask extension | MFEA (GA-based), MFDE (DE-based), MTLLSO (PSO-based) |

| Similarity Measurement Tools | Maximum Mean Discrepancy, Kullback-Leibler Divergence, Grey Relational Analysis [12] | Quantify inter-task relationships for transfer guidance | Source task selection in MGTS strategy [12] |

| Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms | Linear/Nonlinear Mapping, Model-Based Transfer, Anomaly Detection [7] [19] [12] | Enable cross-task knowledge exchange | MDS-based LDA in MFEA-MDSGSS [7] |

| Programming Environments | Python, MATLAB, C++ with CUDA for GPU acceleration [21] [20] | Algorithm implementation and experimentation | High-performance EMTO implementation [20] |

| Performance Metrics | Average Fitness Gain, Convergence Speed, Negative Transfer Frequency [7] [19] | Quantitative algorithm evaluation | Statistical comparison of EMTO variants |

The experimental toolkit for EMTO research comprises several essential components that enable comprehensive investigation and development:

Benchmarking Resources: The CEC2017 Evolutionary MTO competition problems serve as the standard benchmark for comparing algorithm performance [7] [11]. These include diverse problem types with varying degrees of inter-task similarity to thoroughly evaluate algorithm robustness.

Similarity Assessment Tools: Accurate measurement of task relationships is crucial for effective knowledge transfer. Maximum Mean Discrepancy provides a non-parametric measure of distribution similarity [12], while Grey Relational Analysis captures dynamic evolutionary trends [12]. These tools help predict transfer potential and reduce negative transfer.

Transfer Mechanisms: The core innovations in EMTO often reside in novel transfer mechanisms. Multidimensional Scaling enables dimensionality reduction and subspace alignment for tasks with different dimensionalities [7]. Gaussian Mixture Models provide probabilistic representations of population distributions for comprehensive knowledge capture [19].

Computational Infrastructure: As EMTO problems grow in scale and complexity, GPU-accelerated computing frameworks have become essential for handling thousands of tasks efficiently [20]. These platforms significantly reduce search time and enable research on many-task optimization problems.

The research landscape for Evolutionary Multitask Optimization has expanded dramatically since its inception, evolving from a niche concept to a robust paradigm with diverse methodologies and applications. The publication trends reveal a field in rapid maturation, with growing theoretical foundations, increasingly sophisticated algorithms, and expanding real-world applications. The emergence of specialized approaches for handling negative transfer, many-task scenarios, and diverse problem domains indicates the field's responsiveness to fundamental challenges.

Future research directions appear to be focusing on several key areas: scaling EMTO to handle very large numbers of tasks (many-task optimization), improving theoretical understanding of convergence and complexity, enhancing adaptability to dynamic environments, and expanding applications in critical domains such as healthcare, sustainable energy, and complex systems design. As EMTO continues to evolve, its integration with other advanced machine learning techniques and computational frameworks will likely open new frontiers in efficient, knowledge-sharing optimization systems.

Algorithmic Innovations and Real-World Deployment of EMTO

Evolutionary Multitask Optimization (EMTO) represents a paradigm shift in computational optimization, enabling the simultaneous solution of multiple, potentially interrelated, optimization tasks. The foundational Multifactorial Evolutionary Algorithm (MFEA), inspired by biocultural models of multifactorial inheritance, introduced a robust framework for such concurrent problem-solving by evolving a single population of individuals, each associated with a specific task through a skill factor [10]. However, a significant limitation of many early EMTO algorithms, including the canonical MFEA, is their reliance on a single type of evolutionary search operator (ESO), such as a specific genetic algorithm (GA) crossover and mutation scheme, throughout the entire search process [22].

The core challenge is that no single ESO is universally superior for all types of optimization problems. Different problems, characterized by varying fitness landscapes—such as those that are multimodal, deceptive, or high-dimensional—respond differently to the exploration and exploitation properties of various operators [23]. Using a single, fixed ESO for multiple diverse tasks can hinder performance, as the operator may be well-suited to one task but poorly matched to another, ultimately restricting the algorithm's adaptability and convergence precision [22].

This application note explores the frontier of EMTO research that moves beyond this single-operator constraint. We detail the theory, application, and protocol design for leveraging a spectrum of evolutionary search operators—including Genetic Algorithms (GA), Differential Evolution (DE), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)—within a single multitasking environment. By systematically integrating and adaptively controlling these operators, researchers can achieve a more effective balance between global exploration and local exploitation across diverse tasks, leading to enhanced optimization performance and more robust solutions for complex scientific challenges, such as those encountered in drug development.

A Spectrum of Evolutionary Search Operators

The effectiveness of an EMTO algorithm is heavily influenced by the search dynamics of its constituent operators. The integration of a diverse portfolio of ESOs allows the algorithm to leverage the unique strengths of each, adapting to the distinct characteristics of different tasks. The following table summarizes the core mechanisms, strengths, and ideal use cases for three primary operators.

Table 1: Key Evolutionary Search Operators and Their Characteristics in EMTO

| Operator | Core Mechanism | Key Strengths | Ideal for Task Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Simulates natural selection using crossover (e.g., Simulated Binary Crossover - SBX) and mutation (e.g., Polynomial Mutation - PM) [24]. | Strong exploration capabilities; effective at discovering diverse regions of the search space [22]. | Tasks with complex, multi-modal fitness landscapes requiring broad exploration [22]. |

| Differential Evolution (DE) | Utilizes vector differences for mutation (e.g., DE/rand/1: ( vi = x{r1} + F \cdot (x{r2} - x{r3}) )) and a crossover operation to generate trial vectors [22]. | Strong exploitation and reliable local search; often demonstrates fast convergence [22]. | Tasks with smoother, uni-modal landscapes or when fine-tuning solutions near a promising region is critical [22]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Models social behavior; particles update their positions based on their own experience and the experience of neighboring particles [25]. | Efficiently handles high-dimensional problems; effective balance between personal and social influence [25]. | High-dimensional expensive problems (e.g., gene selection) where surrogate models may be employed [25] [26]. |

The selection of ESOs for an EMTO platform is not arbitrary. Empirical studies on benchmark problems like CEC17 have quantitatively demonstrated that the performance of ESOs is task-dependent. For instance, the DE/rand/1 operator has been shown to outperform GA-based operators on the CIHS and CIMS problems, whereas GA operators are more effective on the CILS problem [22]. This evidence underscores the necessity of moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach.

Advanced Multi-Operator EMTO Frameworks and Protocols

Building on the understanding of individual operator strengths, researchers have developed sophisticated EMTO frameworks that manage multiple ESOs. These frameworks can be broadly categorized into fixed, random, and adaptive strategies, with the latter being the most advanced.

The Hybrid Operator-based MFEA (HOMFEA)

Concept: The HOMFEA framework innovates by integrating multiple advanced ESOs directly into the MFEA's evolutionary fabric. It employs a hybrid operator (HO) algorithm that combines the exploitation power of DE Mutation with the exploration capabilities of Simulated Binary Crossover (SBX) and Polynomial Mutation (PM) [24]. This creates a multi-layer search strategy within a single population.

Key Protocol: The core of HOMFEA lies in its memetic algorithm theory, where the hybrid operator is applied to generate offspring. This is coupled with a Vertical Cultural Transmission (VCT) algorithm, which governs the inheritance of skill factors from parents to offspring, thereby managing implicit knowledge transfer between tasks [24].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for HOMFEA-based Inverse Design of Soft Network Materials

| Step | Procedure | Parameters & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Problem Formulation | Define the inverse-engineering design task: Reproduce a target J-shaped stress-strain curve of a biological tissue using a soft network material (SNM). | The objective function is the error between the target curve and the curve produced by a candidate SNM structure [24]. |

| 2. Population Initialization | Randomly generate an initial population of SNM designs. Use two distinct modeling methods (Mode-1, Mode-2) to increase diversity [24]. | Population size (N) is typically set between 100-500 individuals. The two modes prevent premature convergence to a local optimum [24]. |

| 3. HOMFEA Execution | For each generation, create offspring using the Hybrid Operator (HO). Assign skill factors via Vertical Cultural Transmission (VCT). Evaluate fitness using finite element analysis (FEA) [24]. | HO: Applies DE mutation, SBX, and PM. VCT: Uses assortative mating with a random mating probability (rmp) to control cross-task reproduction [24]. |

| 4. Model Validation | Validate the final optimal SNM design by comparing its FEA-simulated stress-strain curve against the target curve. | The HOMFEA-generated design should achieve higher accuracy than designs from semi-rational strategies [24]. |

The Adaptive Bi-Operator MFEA (BOMTEA)

Concept: BOMTEA represents a significant advancement in adaptive control. It maintains two ESOs—GA and DE—and dynamically adjusts their selection probability based on real-time performance feedback [22]. This allows the algorithm to automatically identify and favor the operator best suited for the current state of each task.

Key Protocol: BOMTEA's innovation is its performance-based adaptive strategy. The algorithm tracks the number of improved offspring generated by each ESO over a window of generations. The selection probability for an operator is then proportional to its recent success rate, creating a competitive environment that drives efficiency [22].

Diagram 1: BOMTEA Adaptive Operator Selection Workflow (Title: Adaptive ESO Control in BOMTEA)

Multi-Swarm and Surrogate-Assisted Approaches

Concept: For high-dimensional expensive problems (e.g., gene selection for tumor identification), a multi-swarm approach using PSO and DE in tandem, assisted by surrogate models, has proven effective [25] [26]. This framework often employs a hierarchical or cooperative structure.

Key Protocol: The Multi-Surrogate Assisted Multi-Tasking (MSAMT) algorithm first uses a space-partitioning strategy to divide the search space. Local surrogate models (e.g., Radial Basis Functions) are built for each region to guide global exploration. Near the current best solution, an ensemble surrogate is used for intensive local exploitation. The Generalized MFEA (G-MFEA) then optimizes these multiple surrogate models as related tasks [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Operator EMTO

Implementing and testing advanced multi-operator EMTO algorithms requires a suite of computational tools and benchmark problems.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Operator EMTO

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| CEC17 & CEC22 MTO Benchmarks | Standardized sets of multitask benchmark functions. Used to quantitatively compare and validate the performance of new EMTO algorithms against state-of-the-art methods [22]. | Testing BOMTEA's adaptive operator selection against fixed-operator MFEAs [22]. |

| Python with DEAP, PyGMO, or PlatypUS | Open-source libraries for evolutionary computation. Provide pre-implemented ESOs (GA, DE, PSO) and tools for building custom EMTO frameworks [24]. | Prototyping a new hybrid operator combining DE mutation and SBX crossover [24]. |

| ABAQUS with Python API | Finite Element Analysis (FEA) software. Used for high-fidelity fitness evaluation in engineering design problems (e.g., simulating stress-strain curves of soft network materials) [24]. | Validating the mechanical performance of an SNM design generated by HOMFEA [24]. |

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) / Kriging Surrogates | Machine learning models used as inexpensive approximations of costly objective functions. Critical for making high-dimensional expensive problems tractable [25]. | Building local and global surrogates in the MSAMT algorithm to reduce computational cost [25]. |

| Random Mating Probability (rmp) | A key cultural transmission parameter in MFEA-based frameworks. Controls the frequency of knowledge transfer (crossover) between individuals of different tasks [10]. | Tuning the balance between cross-task knowledge transfer and independent task optimization to mitigate negative transfer [10]. |