Evolutionary Modeling in Cancer Therapy: Overcoming Resistance through Darwinian Dynamics and Computational Approaches

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of evolutionary modeling as a transformative framework for understanding and overcoming cancer therapy resistance.

Evolutionary Modeling in Cancer Therapy: Overcoming Resistance through Darwinian Dynamics and Computational Approaches

Abstract

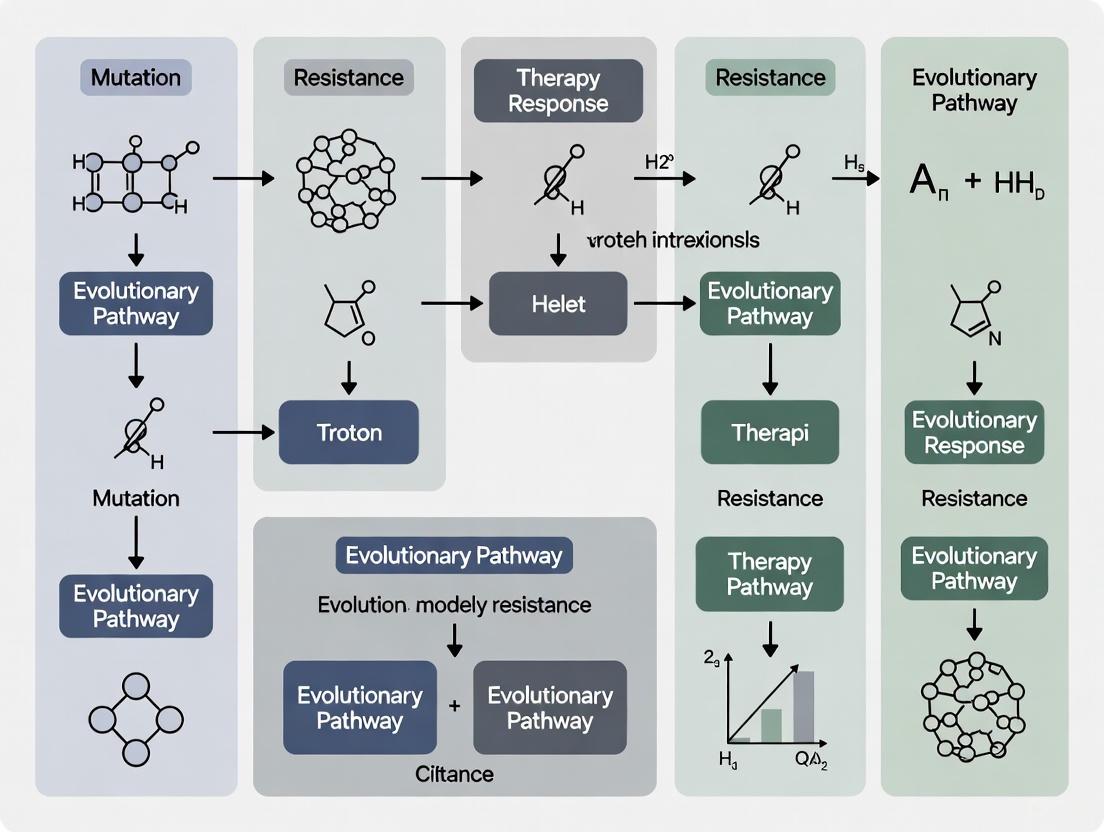

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of evolutionary modeling as a transformative framework for understanding and overcoming cancer therapy resistance. It explores the foundational principles of cancer as an eco-evolutionary process, where resistance develops through Darwinian selection pressures. The content examines cutting-edge methodological approaches, including adaptive therapy, evolutionary steering, and double-bind strategies that exploit fitness trade-offs. It addresses critical implementation challenges in clinical translation and validates these approaches through preclinical models and emerging clinical trial data. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this synthesis bridges theoretical models with practical therapeutic applications, offering a paradigm shift from maximum cell kill to evolution-informed resistance management.

The Evolutionary Arms Race: Understanding Cancer as a Complex Adaptive System

Despite continuous deployment of new treatment strategies and agents over many decades, most disseminated cancers remain fatal. Cancer cells, through their access to the vast information of the human genome, have a remarkable capacity to deploy adaptive strategies for even the most effective treatments [1]. The clinical manifestation of treatment resistance requires two critical steps: first, the deployment of a resistance mechanism, and second, the proliferation of resistant cells to a population large enough to allow tumor progression [1]. While the emergence of resistance mechanisms is virtually inevitable due to the diversity of adaptive strategies available, the proliferation of resistant phenotypes is not—it depends on complex Darwinian dynamics governed by the costs and benefits of resistance mechanisms in the context of the local environment and competing populations [1].

The dynamic cancer ecosystem is extraordinarily robust to therapeutic perturbations due to cellular diversity, spatial and temporal heterogeneity in the tumor environment, and complex interactions with host cells [1]. Traditional maximum tolerated dose (MTD) strategies, while intuitively appealing, accelerate competitive release—a phenomenon wherein eliminating sensitive cells removes competition for resources, allowing resistant populations to expand rapidly [1]. This review explores the evolutionary principles underlying treatment failure and outlines novel therapeutic strategies that exploit Darwinian dynamics to delay or prevent resistance.

Theoretical Foundations: Evolutionary Dynamics in Cancer

Competitive Release and Its Therapeutic Implications

Competitive release occurs when intense Darwinian selection for resistant clones combined with elimination of all competing populations accelerates proliferation of resistant populations [1]. This evolutionary phenomenon is well-documented in pest management, where high-dose pesticide application promotes rapid emergence of uncontrollable, resistant strains [1]. Similarly, in oncology, MTD therapy imposes intense selection for resistant phenotypes while eliminating potential competitors.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional MTD vs. Evolution-Informed Strategies

| Parameter | Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) | Adaptive Therapy | Extinction Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selection Pressure | High, continuous | Dynamic, responsive | Sequential, timed |

| Effect on Sensitive Cells | Complete elimination | Maintained at low levels | Initial reduction then strike |

| Effect on Resistant Cells | Competitive release | Suppressed by competition | Targeted at population nadir |

| Tumor Control Strategy | Maximum cell kill | Stable coexistence | Population extinction |

| Clinical Evidence | Standard of care for many cancers | Phase 2 trials in prostate cancer, melanoma [2] | Preclinical and theoretical models [3] [4] |

Evolutionary Rescue in Cancer Populations

Evolutionary rescue occurs when a population being driven toward extinction by environmental change adapts through beneficial alleles that permit recovery [4]. In cancer, the therapy represents the selective force driving extinction, while resistance mutations serve as the beneficial alleles. The hallmark of evolutionary rescue is a U-shaped trajectory of population size: initial rapid decline to a nadir, followed by renewed expansion [4]. The probability of evolutionary rescue depends on population size at treatment onset, therapy kill rate, and mutation rate for resistance alleles [4].

Diagram Title: Evolutionary Rescue vs. Extinction Pathways

Quantitative Models of Evolutionary Dynamics

Mathematical Framework for Evolutionary Rescue

The probability of tumor extinction under therapy can be modeled using evolutionary rescue theory. For a two-strike extinction therapy approach, the extinction probability PE(τ) is the product of probabilities of no evolutionary rescue due to standing genetic variation (PESGV) and de-novo mutations (PEDN) [3]:

PE(τ) = PESGV(τ) × PEDN(τ)

Where PESGV(τ) = exp[-πeR₂(τ)] represents rescue from pre-existing resistant cells, and PEDN(τ) = exp[-πe(∫₀τμ₂R₁(t)dt + ∫₀τμ₁R₂(t)dt) - πeμ₂(∫τ∞S(t)dt + ∫τ∞R₁(t)dt)] represents rescue from de-novo mutations arising during treatment [3].

Table 2: Key Parameters in Evolutionary Rescue Models

| Parameter | Symbol | Default Value | Biological Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrying capacity | K | N(0) | Maximum population size supported by environment |

| Birth rate | b | 1.0 | Per capita birth rate of sensitive cells |

| Death rate | d | 0.1 | Per capita death rate of all cell types |

| Cost of resistance | c | 0.5 | Fitness cost of resistance mechanism in untreated environment |

| Mutation rate | μ₁, μ₂ | 2.5 × 10⁻⁶ | Rate of acquiring resistance to treatment 1 or 2 |

| Treatment-induced death | δ₁, δ₂ | 2.0 | Additional death rate due to treatment 1 or 2 [3] |

G-Function Framework for Evolutionary Dynamics

The G-function approach in evolutionary game theory provides a unified framework for modeling population and strategy dynamics simultaneously [5]. The fitness-generating function G(v,u,x)∣ᵥ=ᵤᵢ describes the per capita growth rate of individuals with strategy v=uᵢ, where u represents the strategy vector of all populations and x represents their densities [5]. Darwinian dynamics then follow:

dxᵢ/dt = xᵢ × G(v,u,x)∣ᵥ=ᵤᵢ

duᵢ/dt = σᵢ² × ∂G(v,u,x)/∂v∣ᵥ=ᵤᵢ

Where σᵢ² represents the variance of strategic traits in population i, driving evolutionary change [5].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Silico Evaluation of Extinction Therapy Timing

Purpose: To determine the optimal switching time from first-line to second-line treatment in a two-strike extinction therapy protocol [3] [4].

Background: Evolutionary rescue theory suggests that small populations are vulnerable to stochastic extinction and less capable of adapting to environmental changes. The "second strike" should be delivered when the tumor population is at or near its minimum size, which may occur when the tumor is undetectable by conventional imaging [3].

Diagram Title: Extinction Therapy Simulation Workflow

Procedure:

Model Setup:

- Initialize a population of 10⁶ treatment-sensitive cells (S) with small subpopulations (∼100 cells each) of variants resistant to treatment 1 (R₁) and treatment 2 (R₂) [3].

- Set mutation rates for acquiring resistance (default μ₁ = μ₂ = 2.5×10⁻⁶) [3].

- Define fitness costs of resistance (default c = 0.5) and treatment-induced death rates (default δ₁ = δ₂ = 2.0) [3].

Simulation Execution:

- Apply first treatment (strike 1) and simulate population dynamics using either differential equations or stochastic agent-based models.

- Calculate extinction probability PE(τ) for potential switching times τ using evolutionary rescue theory.

- Identify optimal switching time τ* that maximizes PE(τ).

- Apply second treatment (strike 2) at time τ* and continue simulation until extinction, persistence, or progression occurs.

Outcome Assessment:

- Record time to extinction for successful simulations.

- For failures, record whether rescue occurred through standing genetic variation or de-novo mutation.

- Perform sensitivity analysis on key parameters (mutation rates, fitness costs, carrying capacity).

Validation: Compare model predictions with in vitro experiments using cancer cell lines with engineered resistance markers [6].

Protocol: Adaptive Therapy Dose Modulation Based on Evolutionary Game Theory

Purpose: To maintain stable tumor burden by dynamically adjusting treatment doses to preserve treatment-sensitive cells that suppress growth of resistant populations [1] [2].

Background: Adaptive therapy exploits competitive interactions between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cells. By maintaining a population of sensitive cells, resistant cells remain suppressed due to competition for resources [1].

Procedure:

Therapeutic Monitoring:

Dose Modulation Algorithm:

- When tumor burden decreases by 50% from baseline, pause treatment [2].

- Monitor tumor burden regularly (frequency depends on cancer type and biomarker kinetics).

- When tumor burden returns to baseline, reinitiate treatment.

- For dose modulation (alternative to on/off cycling), adjust dose to maintain tumor burden within a stable window (e.g., ±25% of target burden).

Long-term Management:

- Continuously monitor for signs of escape (rapid growth despite treatment).

- If escape occurs, consider switching to alternative therapeutic strategy.

Clinical Validation: In a clinical trial of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer, adaptive therapy based on this protocol increased median time to progression from 16.5 to 27 months while reducing cumulative drug dose to 47% of standard dosing [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evolutionary Therapy Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Beyondcell [6] | Computational method for identifying tumor cell subpopulations with distinct drug responses in single-cell RNA-seq data | Detecting therapeutic clusters in heterogeneous tumors; predicting drug sensitivity patterns |

| SLiM 4.0 [4] | Agent-based evolutionary simulation platform | Modeling clonal evolution and resistance emergence with minimal mathematical assumptions |

| Drug Perturbation Signature Collection (PSC) [6] | Collection of drug-induced expression signatures from LINCS database | Predicting transcriptional responses to treatments; identifying signature reversals |

| Drug Sensitivity Signature Collection (SSC) [6] | Collection of sensitivity signatures from CCLE, GDSC, CTRP | Predicting innate drug sensitivity based on pre-treatment transcriptional state |

| bollito pipeline [6] | Automated scRNA-seq processing pipeline | Cell filtering, normalization, integration, and differential expression analysis |

| Evolutionary Game Theory G-Function Framework [5] | Mathematical framework for coupled ecological and evolutionary dynamics | Modeling population and strategy dynamics of sensitive and resistant cell populations |

Discussion: Clinical Translation and Future Directions

While evolutionary-based therapy approaches show promise, clinical implementation faces several challenges. These include communication barriers between modelers and clinicians, limited trust in mathematical models, increased requirements for disease monitoring, and cultural resistance to outsider ideas in the medical field [2]. However, ongoing clinical trials in prostate cancer, melanoma, and other solid tumors are generating crucial validation data [2].

Future research directions should focus on:

- Developing better biomarkers for real-time monitoring of tumor evolutionary dynamics

- Creating standardized computational platforms for translating evolutionary models into clinical decision support

- Designing clinical trials that incorporate evolutionary principles into combination therapy sequencing

- Integrating single-cell technologies with evolutionary models to predict and prevent resistance

The Darwinian dynamics of treatment failure—from competitive release to evolutionary rescue—provide both an explanation for past therapeutic failures and a roadmap for designing more evolutionarily informed treatment strategies that delay or prevent resistance by working with, rather than against, evolutionary principles.

This application note addresses a fundamental limitation in cancer therapy resistance research: the traditional focus on molecular mechanisms fails to distinguish between the emergence of resistant clones and their subsequent proliferation. We posit that overcoming this limitation requires integrating evolutionary biology principles with advanced single-cell technologies. The protocols herein provide a framework for tracking resistance dynamics and quantifying evolutionary bottlenecks, enabling researchers to design therapeutic strategies that suppress the expansion of resistant populations, not just target their molecular machinery.

Table 1: Key Concepts in Evolutionary Therapy Resistance

| Concept | Traditional Molecular View | Evolutionary Dynamics View |

|---|---|---|

| Resistance Origin | Primarily acquired through new mutations during treatment [8] | Pre-existing in heterogeneous tumors due to intratumoral diversity [9] [10] |

| Therapeutic Goal | Block specific resistance pathways (e.g., efflux pumps, bypass signaling) [8] | Control the eco-evolutionary dynamics of the entire tumor population to suppress resistant clone proliferation [10] |

| Tumor Model | A homogeneous entity with uniform response | A diverse ecosystem of competing and cooperating subclones [9] [11] |

| Primary Challenge | Bypass molecular redundancy | Anticipate and steer evolutionary trajectories [10] |

Cancer drug resistance is estimated to account for approximately 90% of cancer-related deaths [11]. While molecular biology has successfully identified a vast array of resistance mechanisms—including drug efflux, evasion of apoptosis, and DNA damage repair [8]—clinical strategies designed to directly inhibit these mechanisms have seen limited success. A key reason is that cancer is not a static disease but an evolutionary system. In large, diverse cancer cell populations, the emergence of resistant phenotypes is virtually inevitable [10]. Therefore, the critical clinical event is not the initial appearance of a resistant cell, but its ability to proliferate and dominate the tumor ecosystem.

The advent of single-cell transcriptomics (SCT) has starkly revealed the limitations of bulk analysis, which averages gene expression and obscures rare, therapy-resistant subpopulations such as cancer stem-like cells and drug-tolerant persisters [9]. This note provides practical protocols to leverage SCT and evolutionary modeling, moving beyond cataloging mechanisms to actively managing the dynamics of resistance.

Quantitative Foundations: Mapping the Resistance Landscape

A quantitative understanding of resistance is the first step toward controlling it. The following table synthesizes key resistance data across cancer types and therapies, highlighting the pervasiveness of the challenge.

Table 2: Quantitative Landscape of Therapy Resistance

| Cancer Type / Therapy | Resistance Metric | Key Findings / Mechanisms | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced HCC (Sorafenib) | ~60-70% innate resistance; 30-40% acquire resistance within 6 months | Dysregulated drug transporters, metabolic reprogramming, TME interactions [12] | |

| Lung Cancer (PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors) | >60% develop acquired resistance | Tumor microenvironment (TME), autophagy, ferroptosis, T-cell exhaustion [13] | |

| Metastatic Breast Cancer | 30% of early-stage cases progress to metastatic disease | Transcriptional reprogramming, survival of drug-tolerant subpopulations, immune evasion [9] | |

| Pan-Cancer Analysis | Resistance causes ~90% of cancer deaths | Multifactorial: tumor heterogeneity, phenotypic plasticity, apoptotic evasion [8] [11] |

Core Protocol: Tracking Resistant Clone Dynamics with scRNA-seq

This protocol details the use of single-cell RNA sequencing to decouple the emergence of resistant cells from their proliferation over the course of therapy.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq

| Item | Function | Example Product(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Viability Stain | Distinguish live cells for sequencing | Propidium Iodide, DAPI |

| Single-Cell Suspension Kit | Dissociate tumor tissue into viable single cells | Miltenyi Biotec Tumor Dissociation Kits |

| scRNA-seq Platform | High-throughput single-cell capture and barcoding | 10x Genomics Chromium |

| Cell Hashtag Antibodies | Multiplex samples by tagging cells with sample-specific barcoded antibodies | BioLegend TotalSeq-A |

| RT-PCR Reagents | Amplify cDNA from single cells | SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Data processing, clustering, and trajectory inference | CellRanger, Seurat, Monocle |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Experimental Design & Sample Collection:

- Cohort: Establish a murine model or patient-derived xenograft (PDX) for the cancer type of interest.

- Time Points: Collect tumor biopsies or dissociated tumors at critical time points:

- T0: Baseline, pre-treatment.

- T1: Early on-treatment (e.g., after first cycle).

- T2: At minimal residual disease (MRD).

- T3: Upon clinical/radiographic progression.

- Sample Multiplexing: Label cells from different time points with unique Cell Hashtag Antibodies to pool samples for a single library preparation, reducing batch effects.

Single-Cell Library Preparation & Sequencing:

- Tissue Dissociation: Process tumor samples into high-viability (>90%) single-cell suspensions using a gentle, optimized Single-Cell Suspension Kit.

- Cell Capture & Barcoding: Load the cell suspension onto a 10x Genomics Chromium platform to partition individual cells into nanoliter-scale droplets with barcoded beads.

- Library Construction: Perform reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and library construction according to the manufacturer's protocol. Sequence libraries on an appropriate Illumina platform to a minimum depth of 50,000 reads per cell.

Bioinformatic Analysis of Resistance Trajectories:

- Primary Processing: Use CellRanger to align reads, generate feature-barcode matrices, and perform initial quality control.

- Dimensionality Reduction & Clustering: In R/Python, use Seurat to normalize data, identify highly variable genes, perform PCA, and cluster cells using a graph-based algorithm (e.g., Louvain). Visualize clusters in 2D using UMAP.

- Differential Expression & Phenotyping: Identify marker genes for each cluster. Annotate cell types (e.g., malignant, T-cell, fibroblast) and, within the malignant cluster, identify subpopulations expressing resistance signatures (e.g., EMT, stemness, oxidative phosphorylation).

- Trajectory Inference: Utilize Monocle 3 or Slingshot to reconstruct the lineage relationships between cell states. This will infer the potential evolutionary paths from treatment-sensitive to resistant states.

Supporting Protocol: Modeling Evolutionary Bottlenecks

Mathematical modeling is required to translate single-cell data into testable evolutionary hypotheses.

Materials and Computational Tools

- Software: R or Python programming environment.

- Key Packages:

ape(R) for phylogenetics,deSolve(R) for solving differential equations, or custom stochastic simulation code. - Input Data: The cellular lineage and abundance data generated from Protocol 1, Section 4.2.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Construct a Clonal Phylogeny:

- Use the trajectory inference results from Monocle 3 as a scaffold. Alternatively, infer a phylogenetic tree from the single-cell genotyping data (if available) using tools like

ape.

- Use the trajectory inference results from Monocle 3 as a scaffold. Alternatively, infer a phylogenetic tree from the single-cell genotyping data (if available) using tools like

Parameterize a Population Dynamics Model:

- Model the tumor as a system of ordinary differential equations where each compartment represents a distinct subclone (e.g., Sensitive, Drug-Tolerant Persister, Fully Resistant).

dS/dt = r_S * S * (1 - (S + D + R)/K) - d_S * S - δ * SdD/dt = r_D * D * (1 - (S + D + R)/K) + δ * S - d_D * D - ε * DdR/dt = r_R * R * (1 - (S + D + R)/K) + ε * D - d_R * R- Where S, D, R are population sizes of Sensitive, Drug-Tolerant Persister, and Resistant clones; r is growth rate; d is death rate (therapy-induced); K is carrying capacity; and δ, ε are transition rates.

Identify and Target the Bottleneck:

- Fit the model parameters to your time-course scRNA-seq data. The goal is to identify the critical bottleneck in the expansion of the resistant population—is it the initial transition to a persister state (δ) or the subsequent acquisition of full resistance (ε)?

- Design a combination therapy where a second agent specifically targets this bottleneck, for example, by increasing the death rate of the persister population (d_D).

Data Interpretation and Integration

The power of this approach lies in synthesizing data from both protocols.

- Correlate Molecular State with Fitness: The scRNA-seq data (Protocol 1) reveals the molecular identity of the resistant persister and fully resistant clones. The evolutionary model (Protocol 2) quantifies their fitness (growth and death rates) under therapeutic pressure.

- Predict and Intervene: Use the parameterized model to simulate the effects of different combination therapy schedules in silico before moving to in vivo validation. The goal is to identify strategies, such as adaptive therapy, which cycles or modulates drug doses to maintain a population of sensitive cells that can outcompete resistant clones [10].

Application Note

This document provides a structured experimental framework for investigating non-genetic cancer therapy resistance. It outlines defined protocols to dissect the contributions of epigenetic plasticity and the tumor microenvironment (TME) in fostering drug-tolerant persister (DTP) states and sanctuary niches, supporting the development of evolutionary-driven therapeutic models.

Acquired therapeutic resistance remains the primary cause of treatment failure in advanced cancers. While genetic evolution provides a foundational mechanism, non-genetic adaptation—driven by dynamic epigenetic reprogramming and protective microenvironmental niches—confers a rapid, adaptive survival advantage [14] [15]. This application note details methodologies to profile and target these landscapes, focusing on the spatial-epigenetic axis where specific TME niches impose selective pressures that reshape the epigenetic state of resident cancer cells, and vice versa [16].

Key Mechanistic Insights and Associated Quantitative Data

The following table summarizes core epigenetic resistance mechanisms operational within distinct tumor niches, as identified in recent preclinical and clinical studies (2019-2024) [16].

Table 1: Niche-Specific Epigenetic Resistance Mechanisms

| Tumor Niche | Key Epigenetic Axis | Functional Outcome | Quantitative Effect on Resistance | Potential Therapeutic Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxic Core | HIF-1α–SIRT1 | Quiescence, reduced apoptosis | 50-70% reduction in pro-apoptotic gene (e.g., p21, BAX) expression; 2.3-fold reduction in apoptosis under hypoxia [16]. | SIRT1 inhibitors (e.g., EX-527); HIF-1α inhibitors (e.g., PX-478) |

| Invasive Edge | EZH2–H3K27me3 | Proneural-to-Mesenchymal Transition (PMT), plasticity & motility | 2.3-fold higher EZH2 expression; 1.9-fold higher H3K27me3 levels at differentiation gene promoters [16]. | EZH2 inhibitors (e.g., GSK126) |

| Perivascular Niche (PVN) | BRD4–Super-Enhancer (SE); HDAC–DNA Repair | Stemness maintenance, pro-survival transcription | Specific quantitative data not provided in search results, but mechanisms are noted as critical for sustaining GIC populations [16]. | BET inhibitors (e.g., JQ1); HDAC inhibitors |

Experimental Protocols for Deconvolving Resistance Mechanisms

Protocol 1: Spatial Profiling of Epigenetic and Transcriptomic States

Objective: To map epigenetic and gene expression heterogeneity across defined tumor microenvironments (hypoxic core, invasive edge, perivascular niche) from patient-derived samples.

Materials:

- Fresh or optimally preserved frozen GBM tissue sections.

- Spatial transcriptomics platform (e.g., 10x Visium).

- Antibodies for immunohistochemistry (IHC) against niche markers (e.g., CA9 for hypoxia, CD93 for PVN).

- Epigenetic analysis kits (e.g., CUT&Tag for H3K27me3, DNA methylation arrays).

Workflow Diagram: Spatial Multi-omics Profiling

Method Steps:

- Tissue Preparation: Section tissue onto slides compatible with IHC, laser capture microdissection (LCM), and spatial transcriptomics.

- Niche Identification: Perform IHC staining for established niche markers (e.g., hypoxia, vasculature) to guide region selection.

- Region-Specific Isolation:

- Use LCM to isolate cells from specific niches (hypoxic core, invasive edge, PVN) identified in step 2.

- Extract DNA and RNA from these isolated populations for bulk analysis.

- Genome-Wide Profiling:

- Subject DNA to genome-wide methylation analysis (e.g., Illumina EPIC array).

- Subject RNA to bulk RNA-seq or single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) for transcriptomic clustering and trajectory inference [9].

- Spatial Validation: Perform spatial transcriptomics on serial sections to validate and spatially resolve the identified expression patterns.

- Data Integration: Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., CellPhoneDB, NicheNet) to integrate DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility, transcriptomic data, and spatial coordinates to define niche-specific epigenetic signatures [16] [9].

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Epigenetic Targets Using Patient-Derived Models

Objective: To test the efficacy of niche-specific epigenetic inhibitors as radiosensitizers in patient-derived glioblastoma organoids (GBOs).

Materials:

- Patient-derived glioma-initiating cells (GICs).

- Organoid culture media and matrices.

- Epigenetic inhibitors: EX-527 (SIRT1i), GSK126 (EZH2i), JQ1 (BETi).

- Irradiator.

- Viability assay kits (e.g., CellTiter-Glo).

- Flow cytometry antibodies for apoptosis and cell cycle analysis.

Workflow Diagram: Functional Validation in GBOs

Method Steps:

- GBO Generation: Culture and expand GICs in a 3D extracellular matrix to form GBOs that recapitulate tumor heterogeneity [14] [15].

- Epigenetic Pre-treatment: Treat GBOs with a niche-targeting epigenetic inhibitor (e.g., SIRT1i for hypoxic core) for 24-48 hours. Include vehicle control.

- Therapy Challenge: Subject pre-treated and control GBOs to a clinically relevant dose of radiation (e.g., 2-6 Gy).

- Phenotypic Readout:

- Viability: Quantify cell viability 72-96 hours post-radiation using a luminescent ATP-based assay.

- Apoptosis and Cell Cycle: Dissociate GBOs and analyze by flow cytometry for Annexin V/PI staining and DNA content.

- Stemness and Differentiation: Analyze the expression of key markers (e.g., SOX2, OLIG2, MES markers) via qRT-PCR or immunofluorescence.

- Data Analysis: Compare viability, apoptosis, and marker expression between inhibitor+radiation and radiation-only groups to determine the degree of radiosensitization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Epigenetic Plasticity

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Product/Code | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIRT1 Inhibitor | Pharmacological inhibition of SIRT1 deacetylase activity | EX-527 (Selisistat) | Target quiescence and radioresistance in hypoxic core niches [16]. |

| EZH2 Inhibitor | Pharmacological inhibition of EZH2 methyltransferase activity | GSK126, Tazemetostat | Suppress proneural-to-mesenchymal transition (PMT) at invasive edges [16]. |

| BET Inhibitor | Displacement of BRD4 from super-enhancers | JQ1, I-BET151 | Target stemness and pro-survival programs in perivascular niches [16]. |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq Kit | High-throughput transcriptomic profiling of individual cells | 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3' Kit | Deconvolve tumor heterogeneity, identify rare subpopulations, and infer lineage trajectories [9]. |

| Patient-Derived Organoids | Physiologically relevant 3D ex vivo tumor models | N/A (Established in-house from patient samples) | Functional validation of targets and combination therapy testing in a preserved TME context [14]. |

| Cell-Cell Communication Tools | Bioinformatics inference of ligand-receptor interactions | CellPhoneDB, NicheNet | Analyze signaling between tumor niches and stromal/immune cells from transcriptomic data [9]. |

Visualization of Core Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key niche-specific epigenetic axes that drive therapy resistance in glioblastoma, as detailed in Table 1.

Pathway Diagram: Epigenetic Resistance Axes in GBM Niches

The evolution of therapy resistance is the primary cause of treatment failure in advanced cancers, yet the emergence of resistant cells does not automatically lead to clinical progression. Resistance mechanisms impose fitness costs on cancer cells—metabolic burdens and functional compromises that reduce competitiveness in the absence of therapeutic pressure [1]. These inherent trade-offs create critical evolutionary vulnerabilities that can be exploited through novel treatment paradigms. While conventional maximum tolerated dose (MTD) chemotherapy accelerates competitive release of resistant populations by eliminating sensitive competitors, evolutionary-inspired approaches aim to control tumor burden by maintaining a stable population of therapy-sensitive cells that can suppress the expansion of less-fit resistant variants [1] [17].

Understanding these fitness trade-offs requires examining the molecular machinery of resistance, including the synthesis and operation of drug efflux pumps, enhanced DNA repair systems, and alternative signaling pathways. Each mechanism diverts finite cellular resources from proliferation and survival functions, creating quantifiable deficits in growth kinetics and competitive fitness [1]. This application note provides experimental frameworks for quantifying these costs and implementing evolution-informed treatment protocols that transform resistance management in cancer therapy.

Quantitative Profiling of Resistance Costs

Metabolic and Proliferation Costs of Common Resistance Mechanisms

Table 1: Experimentally Measured Fitness Costs of Resistance Mechanisms

| Resistance Mechanism | Experimental Model | Proliferation Rate Reduction | Metabolic Cost | Key Measurable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-glycoprotein (P-gp) Overexpression | MCF-7 breast cancer cells | 15-25% in drug-free medium [18] | Increased ATP consumption from drug efflux [18] | Growth rate, intracellular ATP levels, glucose uptake |

| Enhanced DNA Repair Capacity | Colorectal cancer models with Dicer upregulation | 10-20% under non-stress conditions [18] | Upregulation of repair enzyme synthesis [18] | NHEJ efficiency, ROS sensitivity, replication speed |

| Androgen-Independent Signaling | Prostate cancer LNCaP cells | 30-40% in androgen-rich environments [17] | Alternative pathway maintenance [17] | PSA production rate, testosterone dependence |

| CYP17A1 Overexpression | mCRPC models | 20-30% in low-androgen conditions [17] | De novo androgen synthesis [17] | Testosterone production, growth in castrate conditions |

The fitness costs quantified in Table 1 demonstrate that resistance mechanisms impose substantial burdens on cancer cells, which can be measured through specific experimental approaches. For P-glycoprotein overexpression, the continuous ATP consumption required for drug efflux reduces the energy available for proliferation and biomass production [18]. Similarly, cells with enhanced DNA repair capacity must allocate resources to the synthesis and maintenance of repair complexes, creating a metabolic drain that becomes particularly evident in nutrient-limited conditions [18]. The costs of alternative signaling pathway activation, such as androgen-independent progression in prostate cancer, manifest as reduced growth rates when the original signaling ligand is abundant [17].

Figure 1: Fitness Cost Dynamics in Resistance. This diagram illustrates the causal pathway through which resistance mechanisms impose metabolic costs that lead to competitive disadvantages, particularly during treatment holidays when therapy-sensitive cells can expand.

Protocol: Measuring Competitive Fitness in Co-culture Models

Objective: Quantify the fitness differences between therapy-sensitive and resistant cell populations in drug-free conditions using fluorescent tracking and growth kinetics.

Materials:

- Fluorescently tagged cell lines: GFP-labeled sensitive cells and RFP-labeled resistant variants

- Flow cytometry system: For precise quantification of population ratios

- Time-lapse imaging: IncuCyte or similar system for kinetic growth monitoring

- Metabolic assay kits: ATP quantification, glucose consumption measurements

Procedure:

- Establish co-cultures at defined ratios (start with 1:1, 1:9, and 9:1 sensitive:resistant mixtures)

- Maintain in drug-free medium for 14 days with regular passaging to prevent confluence

- Sample every 48-72 hours for flow cytometry analysis to determine population proportions

- Measure metabolic parameters at days 0, 7, and 14 (ATP levels, glucose consumption, lactate production)

- Calculate competitive fitness index using the formula: Fitness = ln(Rf/Ri) / ln(Sf/Si) Where Rf and Ri are final and initial resistant populations, Sf and Si are final and initial sensitive populations

Data Interpretation: A fitness index <1 indicates resistant cells are less fit than sensitive counterparts. Significant differences in metabolic parameters help explain the mechanistic basis for observed fitness differences.

Evolutionary Therapy Protocols

Adaptive Therapy Scheduling Based on Tumor Dynamics

Table 2: Adaptive Therapy Protocol Parameters from Clinical Evidence

| Parameter | Standard MTD Approach | Evolutionary Adaptive Therapy | Biological Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dosing Strategy | Continuous at maximum tolerated dose | Drug holidays/interruptions based on tumor marker thresholds [17] | Maintains population of sensitive cells to suppress resistant expansion |

| Treatment Trigger | Fixed schedule | PSA or other biomarker increase to predetermined level (e.g., 50% above nadir) [17] | Allows controlled tumor growth while preventing resistant takeover |

| Dose Adjustment | Fixed dose based on BSA | Variable dose based on tumor response dynamics [1] | Minimizes selection pressure while maintaining control |

| Cycle Duration | Fixed intervals | Patient-specific based on tumor growth kinetics [17] | Accommodates inter-patient heterogeneity in evolutionary dynamics |

| Cumulative Drug Exposure | 100% of standard dosing | 47% average reduction reported in clinical trial [17] | Reduces toxicity and treatment costs while maintaining efficacy |

The adaptive therapy approach outlined in Table 2 represents a fundamental shift from conventional cancer treatment paradigms. Rather than attempting to eradicate all cancer cells—an approach that inevitably selects for resistant populations—evolutionary therapy aims for stable tumor control by leveraging the fitness costs of resistance [1]. Clinical trials in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer have demonstrated that this approach can extend time to progression from 16.5 months with standard care to at least 27 months while reducing cumulative drug exposure by 53% [17]. Similar principles have shown promise in preclinical models of breast and ovarian cancers [1].

Figure 2: Adaptive Therapy Workflow. This diagram outlines the decision-making process in evolutionary-informed adaptive therapy, showing how treatment cycles are guided by biomarker monitoring to maintain competitive suppression of resistant cells.

Protocol: Implementing Adaptive Therapy in Preclinical Models

Objective: Establish and validate evolutionary therapy protocols in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models that mimic the clinical adaptive therapy approach.

Materials:

- PDX models: Characterized for therapy sensitivity and resistance markers

- Bioluminescence imaging: For non-invasive tumor burden monitoring

- Drug formulations: Clinical-grade chemotherapeutic or targeted agents

- Statistical software: For modeling tumor growth dynamics and determining treatment thresholds

Procedure:

- Establish baseline growth kinetics: Monitor untreated tumor growth for 14 days to establish doubling time and growth patterns

- Initiate treatment at standard doses until 50% reduction in tumor burden (or biomarker level) is achieved

- Withhold treatment and monitor tumor regrowth, measuring growth rate acceleration

- Reinitiate treatment when tumor burden reaches 75-90% of initial pretreatment volume

- Continue cycles of treatment and holidays, adjusting thresholds based on observed dynamics

- Compare outcomes against continuous MTD treatment in control cohorts

Endpoint Analysis:

- Time to progression: Defined as tumor volume exceeding predetermined threshold despite treatment

- Cumulative drug exposure: Total dose administered across treatment period

- Resistant subpopulation quantification: IHC or flow cytometry for resistance markers at endpoint

- Survival analysis: Progression-free and overall survival compared between strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fitness Cost Investigation

| Reagent/Cell Line | Manufacturer/Model | Research Application | Key Functional Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDR1-GFP Reporter Cells | ATCC MDR1-MDCK-II | P-gp expression and function quantification | Drug efflux capacity, ATP consumption during transport |

| Isogenic Sensitive/Resistant Pairs | NCI-60 resistant variants | Controlled comparison of fitness costs | Growth kinetics, metabolic profiling in matched genetic backgrounds |

| CSC Marker Antibody Panels | BD Biosciences CSC Detection Kit | Cancer stem cell population tracking | ALDH1, CD44, CD133 expression in resistant vs. sensitive cells |

| Seahorse XF Analyzer Kits | Agilent Technologies | Real-time metabolic phenotyping | Glycolytic stress tests, mitochondrial function assays |

| PSA/LDH ELISA Kits | Roche Diagnostics | Tumor burden and cytotoxicity monitoring | Biomarker tracking for adaptive therapy decision points |

| IncuCyte Live-Cell Analysis | Sartorius IncuCyte S3 | Kinetic growth and competition assays | Long-term co-culture monitoring without manual sampling |

The strategic exploitation of fitness trade-offs represents a paradigm shift in cancer therapy that moves beyond direct cytotoxic approaches to encompass evolutionary control strategies. The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks presented here provide researchers with standardized methods to quantify resistance costs and implement evolutionary therapy approaches across different cancer models. By focusing on the dynamic equilibrium between sensitive and resistant populations rather than maximal cell kill, these approaches transform resistance management from reactive to proactive. Clinical validation in prostate cancer demonstrates that evolutionary therapies can simultaneously improve disease control while reducing treatment exposure [17], establishing a compelling framework for broader application across cancer types. The research tools and experimental protocols outlined provide a foundation for expanding this approach to breast, ovarian, and other malignancies where resistance drives mortality.

Cancer therapy, much like traditional pest management, is fundamentally an evolutionary challenge. The prevailing paradigm in oncology has long been the application of maximum tolerated doses (MTD) of cytotoxic agents to achieve maximal cell kill [1]. However, this approach virtually always fails in metastatic disease due to the inevitable emergence of treatment-resistant populations [1] [19]. This failure mirrors historical experiences in agriculture, where high-dose pesticide applications initially achieved impressive pest reduction but ultimately led to rapid evolution of resistant strains that became uncontrollable [1]. The parallel is not merely metaphorical; the Darwinian dynamics governing pest resistance and cancer treatment resistance share fundamental principles that can be leveraged to develop more sustainable therapeutic approaches.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) emerged as an ecological solution to this agricultural challenge, shifting focus from eradication to sustainable management through a combination of biological understanding, controlled intervention, and environmental modification [1]. Similarly, eco-oncology applies ecological and evolutionary principles to understand and manage cancer as a complex, adaptive system [20] [21]. Tumors exhibit remarkable spatial and temporal heterogeneity, continually interact with their microenvironment, and evolve through natural selection to increase cellular fitness [20]. Viewing cancers through this ecological lens provides a framework for developing evolutionarily informed treatment strategies that delay or prevent resistance by managing, rather than attempting to eradicate, the cancer ecosystem.

Table 1: Core Parallels Between Agricultural IPM and Cancer Therapy

| Integrated Pest Management Principle | Oncology Analogue | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Avoid high-dose eradication strategies | Move beyond maximum tolerated dose | Prevent competitive release of resistant subclones |

| Maintain susceptible populations | Preserve treatment-sensitive cells | Utilize adaptive therapy to maintain competition |

| Combine multiple control strategies | Implement combination therapies | Target multiple vulnerabilities simultaneously |

| Modify environment to disfavor pests | Alter tumor microenvironment | Disrupt ecological niches supporting resistance |

| Monitor populations and adapt strategies | Track tumor evolution longitudinally | Employ treatment switching based on resistance detection |

Theoretical Foundation: Ecological Principles Applied to Cancer

The Competitive Release Phenomenon in Cancer Ecosystems

In ecology, competitive release occurs when intense selection pressure eliminates competing populations, allowing a previously suppressed species to expand rapidly [1]. The precise same phenomenon occurs in cancer treatment when MTD chemotherapy eliminates drug-sensitive cells, thereby removing competition and creating ecological space for resistant subclones to proliferate [1]. This dynamic explains why tumors often regrow more aggressively after an initial response to therapy, with resistant populations now dominating the cancer ecosystem.

The clinical manifestation of competitive release is treatment failure due to acquired resistance. Studies tracking the evolution of metastatic breast cancer through serial sampling have demonstrated that as therapy-sensitive cells are eliminated, resistant subclones undergo population bottlenecks followed by expansion to become the dominant populations [22]. This evolutionary trajectory follows a predictable pattern across cancer types, with resistant phenotypes relying on common signaling pathways despite heterogeneous genetic backgrounds [22].

Fitness Costs and Therapeutic Opportunities

A critical insight from ecology is that resistance mechanisms typically incur fitness costs—metabolic burdens or functional trade-offs that reduce competitive ability in the absence of the selective pressure [1]. In cancer, resistance mechanisms such as upregulated drug efflux pumps or enhanced DNA repair capacity consume cellular resources that would otherwise be allocated to proliferation. These fitness costs create therapeutic opportunities to manage, rather than eradicate, cancer populations by maintaining sensitive cells that can outcompete resistant variants in drug-free intervals or under modified selective pressures.

The eco-evolutionary perspective suggests that although emergence of resistance mechanisms to every current therapy is inevitable, proliferation of the resistant phenotypes is not inevitable and can be delayed or prevented with sufficient understanding of the underlying eco-evolutionary dynamics [1]. This represents a fundamental shift from the traditional "kill as many cancer cells as possible" approach to a more nuanced strategy of controlling tumor evolution.

IPM-Inspired Therapeutic Protocols

Adaptive Therapy Dosing Protocol

Theoretical Basis: Adaptive therapy applies ecological principles by maintaining a stable population of therapy-sensitive cells that can suppress the growth of resistant subpopulations through competition for resources and space [1]. This approach leverages the fitness cost of resistance by cycling drug pressure to maintain sensitivity within the tumor ecosystem.

Experimental Methodology:

- Baseline Assessment: Obtain tumor biopsy for single-cell RNA sequencing to characterize subclone heterogeneity and identify dominant signaling pathways [22].

- Initial Dose Determination: Begin treatment at 50% of MTD rather than maximum dose to preserve sensitive populations.

- Monitoring Schedule: Assess tumor burden monthly using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and imaging; track subclone dynamics via serial liquid biopsies.

- Dose Adjustment Algorithm:

- If tumor burden decreases >20%: reduce dose by 25% or implement treatment holiday

- If tumor burden stable (±20%): maintain current dose

- If tumor burden increases >20%: increase dose by 25% or switch to alternative agent

- Resistance Monitoring: Perform monthly analysis of ABC transporter expression and resistance mutation tracking via digital PCR.

Implementation Data: Preliminary clinical data from prostate cancer trials demonstrate that adaptive therapy can maintain stable disease for extended periods with significantly reduced cumulative drug exposure compared to continuous MTD regimens.

Table 2: Adaptive Therapy Monitoring Parameters and Technologies

| Parameter | Assessment Method | Frequency | Decision Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor burden | CT/MRI imaging | 8-12 weeks | ±20% from baseline |

| Subclone dynamics | ctDNA sequencing | 4 weeks | Resistant clone >5% |

| ABC transporter expression | RNA-seq from liquid biopsy | 8 weeks | >2-fold increase |

| Resistance mutations | Digital PCR panel | 4 weeks | Variant allele frequency >1% |

| Patient symptoms | Quality of life questionnaires | 4 weeks | Significant deterioration |

Combination Therapy with Ecological Synergy

Theoretical Basis: Ecological systems respond to single perturbations through compensatory mechanisms, but combined strategic interventions can create stable new equilibria. Similarly, cancer ecosystems can be directed toward more treatable states through carefully timed combination therapies that target both cancer cells and their microenvironmental support systems [20] [19].

Experimental Methodology:

- Ecosystem Mapping: Characterize the tumor ecosystem using spatial transcriptomics and multiplex immunohistochemistry to map cancer cell subtypes, immune populations, stromal components, and vascular networks.

- Target Selection: Identify complementary targets including:

- Proliferation pathways in dominant sensitive clones

- Resistance mechanisms in minor resistant subclones

- Microenvironmental support cells (cancer-associated fibroblasts, tumor-associated macrophages)

- Angiogenic and immunomodulatory factors

- Dosing Sequence Optimization: Implement rational scheduling:

- Week 1-2: Microenvironment disruption (e.g., angiogenesis normalization)

- Week 3-6: Primary cytotoxic or targeted therapy

- Week 7-8: Treatment holiday to allow competitive suppression

- Repeat cycle with monitoring

Implementation Considerations: This approach requires sophisticated diagnostics and frequent monitoring but has the potential to transform advanced cancers into chronic, manageable conditions rather than rapidly lethal diseases.

Experimental Models and Assessment Tools

Preclinical Evolutionary Modeling Systems

3D Ecosystem Co-culture Model: This system models competitive interactions between sensitive and resistant subclones in a microenvironment context.

Protocol Details:

- Cell Line Engineering: Label drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cell lines with different fluorescent markers (eGFP vs mCherry).

- Matrix Preparation: Create 3D extracellular matrix environments with varying stiffness and composition to mimic tissue-specific microenvironments.

- Co-culture Establishment: Plate cells in defined ratios (typically 90:10 sensitive:resistant) in the 3D matrix system.

- Treatment Application: Apply therapeutic agents in continuous, intermittent, or adaptive schedules.

- Population Tracking: Monitor population dynamics via fluorescence imaging and flow cytometry over 4-8 weeks.

- Microenvironment Analysis: Assess cytokine profiles, metabolic gradients, and cell-cell interaction changes.

Data Interpretation: This model allows quantification of competitive indices, fitness costs of resistance, and ecosystem-level responses to different treatment strategies before clinical implementation.

Longitudinal Molecular Monitoring Workflow

Liquid Biopsy Ecosystem Analysis: This protocol enables non-invasive tracking of tumor evolution during therapy.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect blood samples at baseline and every 2-4 weeks during therapy.

- Plasma Separation: Process within 2 hours of collection to prevent nucleic acid degradation.

- ctDNA Isolation: Extract cell-free DNA using silica-membrane technology.

- Library Preparation: Create sequencing libraries with unique molecular identifiers to reduce errors.

- Targeted Sequencing: Use hybrid capture panels covering 500+ cancer-associated genes.

- Clone Deconvolution: Apply computational methods to reconstruct subclonal architecture from variant allele frequencies.

- Phenotype Inference: Use RNA expression signatures from circulating tumor cells to infer pathway activation.

Analytical Outputs: This workflow generates temporal data on subclone dynamics, emerging resistance mechanisms, and ecosystem evolution in response to therapeutic pressure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Eco-Evolutionary Cancer Therapy Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Cell Labels | eGFP, mCherry, CellTracker dyes | Competitive co-culture assays | Visual tracking of sensitive vs resistant populations |

| 3D Culture Matrices | Matrigel, collagen hydrogels, synthetic scaffolds | Tumor ecosystem modeling | Recreation of tumor microenvironment complexity |

| Single-Cell Analysis Platforms | 10X Genomics, Fluidigm C1 | Tumor heterogeneity characterization | Resolution of subclonal architecture and phenotypes |

| ctDNA Isolation Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, MagMAX Cell-Free DNA | Liquid biopsy processing | Non-invasive tumor monitoring and clone tracking |

| Targeted Sequencing Panels | Illumina TruSight Oncology, ArcherDx | Resistance mutation detection | Comprehensive profiling of evolving resistance mechanisms |

| Pathway Inhibitors | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, epigenetic modulators | Combination therapy testing | Targeting of phenotype-specific vulnerabilities |

Discussion and Future Directions

The application of Integrated Pest Management principles to cancer therapy represents a paradigm shift from eradication to evolutionary control. This approach acknowledges that cancer is not a static enemy to be defeated but a dynamic, evolving ecosystem that must be managed through sophisticated understanding of ecological and evolutionary principles [20] [1] [21]. The protocols outlined here provide a framework for implementing this ecological perspective in both preclinical models and clinical practice.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: improved evolutionary monitoring technologies, sophisticated mathematical modeling of cancer ecosystem dynamics, rational combination therapy design, and personalized adaptive therapy algorithms. As noted by researchers, "If the acquisition of drug resistance that leads to treatment failure and to patient death can be substantially delayed, then cancer could become a chronic condition" [19]. This vision of transforming lethal cancers into manageable chronic diseases represents the ultimate promise of applying ecological principles to oncology.

The eco-evolutionary approach to cancer therapy requires interdisciplinary collaboration between oncologists, ecologists, evolutionary biologists, and computational scientists. By learning from centuries of ecological management experience and applying these principles to cancer ecosystems, we can develop more sustainable and effective strategies for managing advanced cancers, ultimately turning one of humanity's most formidable foes into a controllable chronic condition.

Computational Strategies and Therapeutic Applications: From Models to Clinical Protocols

The persistence and evolution of therapeutic resistance remain the primary causes of treatment failure in oncology. Confronting this challenge requires a paradigm shift from traditional maximum cell-kill approaches to strategies that explicitly account for cancer's evolutionary dynamics [23]. Quantitative modeling provides the essential theoretical framework to understand, predict, and disrupt the evolutionary trajectories of resistant cancer cell populations. By formalizing the complex ecological interactions within tumors, these models enable the design of evolutionarily-informed treatment protocols that can delay or prevent the emergence of resistance [24] [23].

This article details the four dominant quantitative frameworks—Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs), Partial Differential Equations (PDEs), Agent-Based Models (ABMs), and Game-Theoretic Frameworks—applied to cancer therapy resistance research. We present structured comparisons, experimental protocols, and implementation workflows to equip researchers with practical methodologies for developing and applying these models in preclinical and clinical settings.

Model Frameworks and Comparative Analysis

Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Models

ODE models describe the dynamics of cell populations over time using equations that depend only on time as an independent variable. They are particularly effective for modeling the competition between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cell subpopulations at the whole-tumor level, ignoring spatial heterogeneity.

Core Application: Modeling population dynamics of sensitive and resistant cells under therapeutic pressure. Key Components:

- State variables (e.g., population sizes of sensitive cells ( S(t) ) and resistant cells ( R(t) ))

- Parameters (e.g., growth rates, conversion rates, drug kill rates)

- System of differential equations

A foundational ODE model for induced drug resistance is given by [25]: [ \begin{aligned} \frac{dx1}{dt} &= (1 - (x1 + x2))x1 - (\epsilon + \alpha u(t))x1 - du(t)x1 \ \frac{dx2}{dt} &= pr(1 - (x1 + x2))x2 + (\epsilon + \alpha u(t))x1 \end{aligned} ] where ( x1 ) and ( x2 ) represent sensitive and resistant cell populations, ( \epsilon ) is the spontaneous resistance rate, ( \alpha ) is the drug-induced resistance rate, ( d ) is drug cytotoxicity, ( p_r ) is the relative growth rate of resistant cells, and ( u(t) ) is the time-dependent drug concentration.

Partial Differential Equation (PDE) Models

PDE models extend population dynamics to include spatial dimensions, enabling the study of how spatial heterogeneity and tissue architecture influence the emergence and spread of resistance.

Core Application: Modeling spatiotemporal dynamics of tumor invasion and treatment response. Key Components:

- State variables dependent on both time and space (e.g., ( c(x,t) ))

- Diffusion terms modeling cell migration

- Reaction terms modeling proliferation and death

- Boundary conditions

A proliferation-invasion PDE model takes the form [26] [27]: [ \frac{\partial c(x,t)}{\partial t} = D\nabla^2c(x,t) + \rho c(x,t)(1 - \frac{c(x,t)}{K}) - kd(x,t)c(x,t) ] where ( c(x,t) ) is the cancer cell density at location ( x ) and time ( t ), ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient modeling cell motility, ( \rho ) is the proliferation rate, ( K ) is the carrying capacity, and ( kd(x,t) ) is the therapy-induced death rate.

Agent-Based Models (ABMs)

ABMs simulate the behavior and interactions of individual cells (agents) within a defined environment, generating emergent population-level dynamics from simple individual-level rules.

Core Application: Modeling intratumor heterogeneity and complex cellular interactions driving resistance. Key Components:

- Agents representing individual cells

- Rule sets governing agent behavior

- Environment representing tissue space and resources

- Stochastic elements

ABMs are particularly valuable when analytic solutions are intractable, such as in models with complex interactions and finite population sizes [28]. They can incorporate rules for cell division, death, mutation, movement, and resource consumption based on local microenvironmental conditions.

Evolutionary Game-Theoretic Frameworks

Evolutionary game theory models cancer as an ecosystem where different cell types (strategies) compete according to fitness payoffs, with treatment acting as a modifier of the evolutionary landscape.

Core Application: Designing adaptive therapy protocols that control tumor evolution. Key Components:

- Player types (sensitive cells, resistant cells, immune cells)

- Strategy sets (cooperate/defect phenotypes)

- Payoff matrices representing fitness interactions

- Population dynamics governed by evolutionary stability

In this framework, cancer cells act as "defectors" in a population dynamics game, while healthy cells act as "cooperators," with the immune system serving as a dynamic regulator [29]. Treatment becomes an evolutionary "game" where the objective shifts from maximum cell kill to controlling the competitive balance between sensitive and resistant populations.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Quantitative Modeling Approaches

| Model Type | Mathematical Formulation | Spatial Resolution | Key Strengths | Primary Applications in Resistance Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ODE Models | System of differential equations: ( \frac{d\vec{x}}{dt} = f(\vec{x}, t, \vec{p}) ) | No | Mathematical tractability, parameter identifiability, well-suited for optimal control | Modeling population dynamics of sensitive/resistant cells; predicting resistance evolution under different dosing schedules [25] [26] |

| PDE Models | Partial differential equations: ( \frac{\partial c}{\partial t} = D\nabla^2c + R(c) ) | Yes | Captures spatial heterogeneity, invasion fronts, and microenvironmental gradients | Studying geography of resistance emergence; impact of tumor architecture on treatment efficacy [26] [27] |

| Agent-Based Models | Rule-based systems with stochastic elements | Yes (discrete) | Models individual cell variability and complex local interactions; emergent phenomena | Investigating intratumor heterogeneity; role of rare cell subpopulations in resistance [28] [2] |

| Game-Theoretic Frameworks | Payoff matrices + population dynamics: ( \frac{dxi}{dt} = xi[(A\vec{x})_i - \vec{x}^TA\vec{x}] ) | Optional | Explains paradoxical behaviors; designs evolutionarily stable treatments | Adaptive therapy design; exploiting cost of resistance; maintaining treatment-sensitive populations [29] [23] |

Table 2: Dominant Resistance Mechanisms and Corresponding Modeling Approaches

| Resistance Mechanism | Most Suitable Model Types | Key Model Parameters | Expected Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-existing genetic mutations | ODE, Game Theory | Mutation rate (ε), relative fitness of resistant cells (pr) | Initial decline then relapse due to resistant population expansion [25] |

| Drug-induced resistance | ODE, ABM | Induction rate (α), selection pressure | Accelerated resistance development with continuous therapy [25] |

| Spatial heterogeneity in drug penetration | PDE, ABM | Diffusion coefficient (D), nutrient/oxygen gradients | Resistance emergence in sanctuary sites with subtherapeutic drug levels [26] |

| Metabolic cooperation and competition | Game Theory, ABM | Resource availability, cost of resistance | Stable coexistence of sensitive/resistant cells under resource limitation [29] [23] |

| Epigenetic plasticity | ABM, ODE with phenotype switching | Switching rates between phenotypes | Rapid adaptive resistance without genetic changes [25] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: ODE Model Development and Calibration for Resistance Forecasting

Objective: Develop a predictive ODE model for resistance evolution under specific therapeutic regimens.

Materials and Reagents:

- In vitro or in vivo time-course data on tumor volume/cell count

- Drug concentration-response data

- Genomic or functional data on resistance marker prevalence

Procedure:

- System Specification: Define state variables (e.g., sensitive cells S, resistant cells R) and their interactions

- Parameter Estimation: Use maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods to estimate parameters from pretreatment data

- Model Validation: Compare model predictions with observed treatment response data not used in calibration

- Therapy Optimization: Apply optimal control theory to identify dosing schedules that maximize time to progression [25]

Data Analysis:

- Structural identifiability analysis to determine which parameters can be uniquely estimated

- Sensitivity analysis to identify most influential parameters

- Bayesian calibration to quantify parameter uncertainty and model predictions

Protocol 2: Implementing Adaptive Therapy Based on Evolutionary Games

Objective: Design and execute an evolution-based adaptive therapy protocol in preclinical models.

Materials and Reagents:

- Syngeneic or patient-derived xenograft models

- Biomarkers for tumor burden (e.g., PSA, imaging)

- Drugs with known resistance mechanisms

Procedure:

- Model Initialization: Calibrate game-theoretic model with baseline tumor composition data

- Treatment Strategy: Implement adaptive algorithm:

- Administer therapy until tumor burden decreases by predetermined percentage (e.g., 50%)

- pause treatment until tumor regrows to initial size

- Resume treatment [2]

- Monitoring: Track tumor burden and resistant subpopulation frequently

- Model Refinement: Update model parameters based on observed response

Validation Metrics:

- Time to progression compared to standard continuous therapy

- Cumulative drug dose

- Resistant subpopulation fraction at progression

Figure 1: Adaptive Therapy Decision Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Evolutionary Therapy Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Resistance Research | Compatible Model Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical Models | Patient-derived xenografts (PDX), Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) | Provide in vivo systems for validating model predictions and testing therapeutic strategies | All model types |

| Cell Line Repositories | Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), NCI-60 panel | Enable high-throughput drug screening and resistance mechanism identification | ODE, Game Theory |

| Omic Technologies | Whole-exome sequencing, RNA-seq, Single-cell sequencing | Characterize molecular evolution of resistance and tumor heterogeneity | ABM, PDE, ODE |

| Mathematical Software | MATLAB, R, Python (SciPy), COPASI | Implement and numerically solve mathematical models | All model types |

| Clinical Data Resources | TCGA, GENIE, Adaptive therapy trial data | Provide real-world data for model calibration and validation | All model types |

Integration and Visualization of Model Dynamics

Figure 2: Multi-Model Integration Workflow for Clinical Translation

The integration of ODE, PDE, agent-based, and game-theoretic modeling approaches provides a powerful multidisciplinary framework to address the critical challenge of therapy resistance in oncology. Each approach offers complementary insights: ODEs for population-level dynamics, PDEs for spatial heterogeneity, ABMs for cellular complexity, and game theory for evolutionary strategies. The future of cancer therapy resistance research lies in combining these quantitative approaches with experimental and clinical data to design evolutionarily-informed treatment strategies that can outmaneuver cancer's adaptive capabilities. As these models become increasingly refined and validated, they hold the promise of transforming cancer from a lethal disease to a controllable chronic condition.

Adaptive Therapy (AT) is an evolution-based approach to cancer treatment that updates treatment decisions in dynamic response to evolving tumor dynamics. This strategy represents a fundamental shift from the traditional maximum tolerated dose (MTD) paradigm. Unlike MTD, which aims to kill the maximum number of tumor cells and often accelerates the proliferation of resistant populations, adaptive therapy maintains tolerably high levels of tumor burden to exploit the competitive suppression of treatment-resistant subpopulations by treatment-sensitive subpopulations [1] [30].

The conceptual foundation of adaptive therapy rests on core evolutionary principles. While the emergence of resistant cancer cells to current therapies is virtually inevitable, the proliferation of these resistant phenotypes is not inevitable and can be delayed or prevented with sufficient understanding of underlying eco-evolutionary dynamics [1]. Adaptive therapy capitalizes on the Darwinian interactions between sensitive and resistant cell populations, leveraging the fitness cost of resistance mechanisms that often impair cellular proliferation in treatment-free environments [30].

Theoretical Framework and Evolutionary Principles

Evolutionary Dynamics of Cancer Therapy

Cancer ecosystems demonstrate remarkable robustness to therapeutic perturbations due to cellular diversity, spatial heterogeneity in genotypic and phenotypic properties, and variations in the tumor microenvironment [1]. Traditional MTD approaches accelerate competitive release—an evolutionary phenomenon where eliminating sensitive cell populations removes natural competitors for resistant cells, allowing their rapid expansion [1]. This explains why MTD often produces initial tumor shrinkage followed by aggressive, treatment-resistant relapse.

Adaptive therapy applies principles derived from successful pest management strategies, where controlled application of pesticides prevents emergence of resistance while maintaining acceptable damage levels [1]. Similarly, AT maintains a stable tumor volume by strategically balancing treatment-sensitive and-resistant populations through dynamic treatment modulation.

Key Requirements for Adaptive Therapy Success

Research indicates that adaptive therapy success depends on three critical characteristics of the cancer ecosystem [30]:

- Cost of Resistance: Resistance mechanisms must impose a fitness cost that reduces proliferative advantage in untreated environments

- Competitive Suppression: Resistant cells must be suppressible through competition with sensitive cells

- Therapy Sensitivity: Treatment must effectively reduce the population of sensitive cells

When these conditions are met, mathematical models demonstrate a trade-off curve between time for resistant cells to emerge and mean cancer burden, which guides protocol optimization [30].

Table 1: Comparison of Cancer Treatment Paradigms

| Parameter | MTD | Intermittent Therapy | Adaptive Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Goal | Maximum cell kill | Periodic high-dose killing | Stable tumor burden |

| Dosing Schedule | Continuous high dose | Fixed periodic holidays | Dynamic, response-driven |

| Selection Pressure | High for resistance | Intermediate | Low for resistance |

| Competitive Release | Maximized | Moderate | Minimized |

| Cumulative Dose | High | Moderate | Variable, often lower |

Protocol Classifications and Algorithmic Structures

Dose-Skipping Protocols

Dose-skipping approaches administer high-dose treatment until a specific tumor response threshold is achieved, followed by a treatment holiday until a predetermined upper threshold is reached [30]. The first adaptive therapy clinical trial for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) employed a dose-skipping protocol where abiraterone was withdrawn until prostate-specific antigen (PSA) returned to 50% of baseline levels, then restarted [30]. This 50% rule created patient-specific treatment holidays that varied considerably between individuals, with holidays typically shortening in later treatment cycles as PSA dynamics accelerated.

Dose-Modulation Protocols

Dose-modulation approaches adjust drug dosage at regular intervals based on tumor response metrics rather than implementing complete treatment holidays [30]. While both dose skipping and dose modulation have demonstrated efficacy in experimental models, only dose skipping has been translated to clinical practice thus far [30]. Dose modulation offers potential advantages in maintaining more stable tumor control through finer adjustments to therapeutic pressure.

Quantitative Framework and Mathematical Modeling

Mathematical Foundations

Adaptive therapy protocols are fundamentally guided by mathematical models that simulate tumor dynamics under treatment pressure. The core modeling approach typically incorporates distinct sensitive and resistant cancer cell populations, with extensions including healthy cells, immune cells, resource dynamics (e.g., hormones), Allee effects, and phenotypic plasticity [30]. Simple models often demonstrate robustness across most extensions except for Allee effects and cell plasticity, which require specialized modeling approaches [30].

Table 2: Key Mathematical Models in Adaptive Therapy

| Model Type | Key Components | Clinical Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lotka-Volterra Competition | Sensitive-resistant cell competition | Prostate cancer, melanoma | [30] |

| Gompertzian Growth | Carrying capacity, growth decay | Theoretical optimization | [30] |

| Consumer-Resource | Androgen dynamics in prostate cancer | mCRPC with abiraterone | [30] |

| Hybrid Cellular Automaton | Spatial competition, cost of resistance | CDK inhibitor applications | [30] |

Optimal Treatment Timing Framework

Recent research has established a general framework for deriving optimal treatment protocols that account for discrete clinical monitoring intervals [31]. This approach addresses the significant limitation of previous models that ignored practical constraints of clinical appointments where tumor burden is measured and treatment schedules reevaluated. The framework identifies a critical trade-off between monitoring frequency and time to progression, proposing that a subset of patients with qualitatively different dynamics require novel protocols with thresholds that change over the treatment course [31].

The mathematical optimization reveals that tumor dynamics between patients vary significantly, resulting in substantial heterogeneity in outcomes that necessitates personalization of adaptive protocols [31]. This personalized approach moves beyond the one-size-fits-all application of the same threshold rules to all patients.

Clinical Workflow and Experimental Protocol

Clinical Implementation Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocol for mCRPC

Background: This protocol adapts the approach from the first adaptive therapy clinical trial in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer, which demonstrated prolonged progression-free survival and lower cumulative drug dose compared to standard of care [30].

Inclusion Criteria:

- Histologically confirmed metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer

- Minimum 50% drop in PSA level under abiraterone administration

- Adequate organ function and performance status

- Willingness to comply with frequent monitoring schedule

Materials and Reagents:

- Abiraterone acetate (Zytiga)

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) assay kits

- Imaging equipment (CT, MRI, or bone scan)

- Data collection forms for symptom tracking

Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment: Obtain baseline PSA level, perform staging imaging, document disease-related symptoms

- Initial Treatment Phase: Administer abiraterone at standard dose (1000mg daily) with prednisone

- Monitoring Schedule: Measure PSA levels at 2-week intervals initially, extend to 4-week intervals once stability established

- Treatment Decision Points:

- Continue abiraterone until PSA declines to 50% of baseline value (treatment response)

- Withdraw abiraterone until PSA returns to baseline level (treatment holiday)

- Reinitiate abiraterone at previous dose level

- Response Evaluation:

- Record PSA doubling time during treatment holidays

- Monitor for symptomatic progression

- Perform imaging every 12 weeks or as clinically indicated

- Protocol Adaptation:

- Shorten treatment holidays if PSA acceleration observed in subsequent cycles

- Consider dose modification for toxicity management

- Document cumulative drug exposure

Quality Control:

- Standardize PSA measurement techniques across all assessments

- Establish threshold for significant PSA progression (typically 50% above nadir)

- Implement centralized review of imaging studies

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Adaptive Therapy Investigations

| Research Tool | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Modeling Software | Simulate tumor dynamics under treatment | Protocol optimization, patient-specific forecasting |

| PSA Assay Kits | Quantify prostate-specific antigen | Monitoring tumor burden in prostate cancer trials |

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Analysis | Detect resistance mutations | Early identification of resistant subclones |

| Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Models | In vivo testing of adaptive protocols | Preclinical validation of dosing strategies |

| Lotka-Volterra Competition Models | Quantify competitive interactions | Predicting sensitive-resistant cell dynamics |

| Hormone Level Assays | Measure resource dynamics | Androgen monitoring in prostate cancer |

Clinical Translation and Trial Design Considerations

Adaptive therapy has been integrated into several ongoing or planned clinical trials, including treatments for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, and BRAF-mutant melanoma [31] [30]. The initial clinical results from the mCRPC trial demonstrated significant extensions in time to progression over standard of care, generating interest in designing new adaptive treatment protocols across multiple cancer types [30].

Critical considerations for clinical translation include:

- Biomarker Selection: Identifying reliable, responsive biomarkers of tumor burden (e.g., PSA in prostate cancer) that can guide treatment decisions

- Monitoring Frequency: Balancing practical constraints with optimal assessment intervals to detect significant changes before progression

- Threshold Determination: Establishing patient-specific versus population-based thresholds for treatment adaptation

- Trial Design: Implementing novel clinical trial structures like Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized (SMAR) trials that can efficiently compare adaptive strategies [32]

The planned ANZadapt trial (NCT05393791) in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer represents a larger, randomized study that will provide more robust evidence regarding adaptive therapy efficacy [30].