Evolutionary Mismatch and Human Disease: A Genomic Framework for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

This article synthesizes the evolutionary mismatch hypothesis to explore the rising global burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

Evolutionary Mismatch and Human Disease: A Genomic Framework for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes the evolutionary mismatch hypothesis to explore the rising global burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). It posits that a discrepancy between our ancestral human biology and modern industrialized environments underlies susceptibility to conditions like obesity, type 2 diabetes, and autoimmune disorders. We outline a foundational evolutionary framework, detail methodological approaches for identifying genotype-by-environment (GxE) interactions, address challenges in validating mismatch hypotheses, and compare evidence across diverse populations. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review advocates for integrating evolutionary principles with genomic medicine to refine disease etiologies, identify novel therapeutic targets, and advance the goals of personalized, precision medicine.

The Evolutionary Roots of Modern Disease: Defining Mismatch and Its Core Mechanisms

The evolutionary mismatch hypothesis provides a powerful framework for understanding the rising global burden of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). This technical guide delineates the core concepts of mismatch theory, where traits that evolved as adaptations in ancestral environments (E1) become maladaptive in rapidly altered novel environments (E2). We synthesize current research to detail the phenotypic and genetic mechanisms underpinning this phenomenon, with particular emphasis on human health applications. The document provides structured quantitative data, experimental methodologies for identifying genotype-by-environment (GxE) interactions, and visual tools to aid researchers and drug development professionals in mapping this conceptual model onto modern biomedical challenges.

Core Conceptual Framework of Evolutionary Mismatch

Evolutionary mismatch describes a state of disequilibrium whereby an organism, having evolved in a specific ancestral environment (E1), develops a phenotype that is harmful to its fitness or well-being in a novel environment (E2) [1] [2]. This occurs because the rate of cultural and environmental change often far exceeds the pace of genetic adaptation [3]. The concept is integral to evolution in changing environments and is increasingly prevalent for all species in human-altered habitats, including humans themselves [2].

The formal analysis of a mismatch requires clarifying three central components:

- The Ancestral Environment (E1): The selective environment in which a trait (T) evolved and was likely maintained by natural selection. For humans, this typically refers to the pre-agricultural, hunter-gatherer lifestyle [1] [4].

- The Novel Environment (E2): The current, significantly altered environment to which the organism is imperfectly adapted. For humans, this is the post-industrial, modern environment characterized by processed foods, sedentary behavior, and improved hygiene [1] [3].

- The Trait (T): The specific phenotypic characteristic—whether physiological, morphological, or behavioral—that is expressed in both E1 and E2 but with divergent fitness consequences [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Ancestral (E1) and Novel (E2) Human Environments

| Environmental Component | Ancestral Environment (E1) | Novel Environment (E2) |

|---|---|---|

| Diet | Variable, unprocessed, high-fiber, low in simple sugars | Constant access, ultra-processed, high in refined sugars and fats |

| Physical Activity | High levels of daily locomotion | Sedentary lifestyles, prolonged sitting |

| Pathogen Exposure | High diversity, including helminths and microbiota | Low diversity, minimized by hygiene and antibiotics |

| Social Structure | Small, egalitarian bands | Large, complex, hierarchical societies |

| Psychosocial Stressors | Immediate, physical threats (e.g., predators) | Chronic, abstract threats (e.g., work deadlines, social media) |

Quantitative Evidence: Phenotypic Manifestations in Human Health

The transition to modernity has reshaped environments, yet the slower rate of biological evolution limits phenotypic change, resulting in mismatch conditions that are more common or severe in E2 [4] [5]. The following data summarizes key NCDs linked to the mismatch framework.

Table 2: Public Health Burden of Select Evolutionary Mismatch Conditions

| Mismatch Condition | Proposed E1 Adaptive Value | E2 Maladaptive Consequence | Prevalence & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity & Type 2 Diabetes | "Thrifty genotype" favored efficient energy extraction and storage during feast-or-famine conditions [1] [3]. | Energy-dense diets and low physical activity promote chronic positive energy balance [1] [3]. | Obesity is rampant in developed countries and rapidly increasing in developing nations [3]; NCDs are leading causes of death worldwide [4]. |

| Osteoporosis | High peak bone mass from lifelong high levels of physical activity [1]. | Sedentary lifestyles lead to lower peak bone mass, increasing fracture risk with aging [1]. | Fossil evidence suggests osteoporosis was less common in elderly hunter-gatherers than in modern Western populations [1]. |

| Autoimmune & Allergic Diseases | Immune systems co-evolved with and were regulated by a high burden of parasites and pathogens (e.g., helminths) [3]. | Hygiene and medical advances eradicate these organisms, leading to immune dysregulation [1] [3]. | The rise of multiple sclerosis and irritable bowel disease in industrialized settings is linked to the loss of "old friends" like helminths [3]. |

| Anxiety & Addiction | Anxiety promoted immediate survival; reward systems reinforced behaviors beneficial for survival (e.g., finding food) [1]. | In delayed-return environments, anxiety becomes chronic; reward systems are exploited by drugs, gambling, and hyper-palatable food [1]. | Behavioral mismatches contribute to modern mental health crises and addictive disorders [1]. |

Methodological Toolkit: Identifying Genetic and Physiological Mechanisms

To move beyond correlation and establish causation within the mismatch framework, a rigorous, multi-level methodological approach is required. The following section outlines key experimental protocols and analytical strategies.

Protocol for Establishing a Mismatch

According to current research, confirming an evolutionary mismatch requires satisfying three core criteria [4] [5]:

- Phenotypic Prevalence Gradient: The mismatch condition must be demonstrably more common or severe in the novel environment (E2) compared to the ancestral proxy environment. This is typically established through cross-population comparisons between industrialized and subsistence-level societies [4].

- Environmental Causation: The condition must be tied to specific environmental variables that differ systematically between E1 and E2 (e.g., diet quality, physical activity level, microbial exposure) [4] [5].

- Mechanistic Explanation: A molecular or physiological mechanism must be established that explains how the environmental shift generates the mismatch condition. At the genetic level, this manifests as Genotype-by-Environment (GxE) interactions [4] [6].

Genomic Workflow for Detecting GxE Interactions

A powerful strategy for identifying GxE interactions involves partnering with small-scale, subsistence-level populations undergoing rapid lifestyle change. These groups provide a quasi-natural experiment with extreme environmental variation within a shared genetic background [4] [5]. The workflow below details this approach.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully executing the genomic workflow requires a suite of specialized reagents and methodological tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mismatch Studies

| Research Component | Specific Examples & Functions |

|---|---|

| Genomic Analysis | Whole-genome sequencing kits: For comprehensive variant discovery. Genotyping arrays: For cost-effective screening of known SNPs in large cohorts. Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) algorithms: To calculate aggregate genetic risk for NCDs and test for GxE interactions [4]. |

| Environmental Exposure Assessment | Food frequency questionnaires & dietary biomarkers: To quantitatively assess nutritional intake. Accelerometers: To objectively measure physical activity levels. Microbiome sequencing kits (16S rRNA, metagenomics): To characterize gut microbiota composition and diversity [4]. |

| Phenotypic & Clinical Measurement | ELISA kits: For quantifying biomarkers (e.g., insulin, inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6). DEXA scanners: For precise measurement of body composition and bone density. Blood pressure monitors & clinical chemistry analyzers: For standard cardiometabolic profiles [1] [4]. |

| Functional Validation | Cell culture systems (e.g., hepatocytes, adipocytes): For in vitro testing of candidate gene function in metabolic pathways. Animal models (e.g., mice, zebrafish): For in vivo studies of gene function in a whole-organism context. Helminthic therapy agents: For experimental testing of the "hygiene hypothesis" and biome reconstitution [3]. |

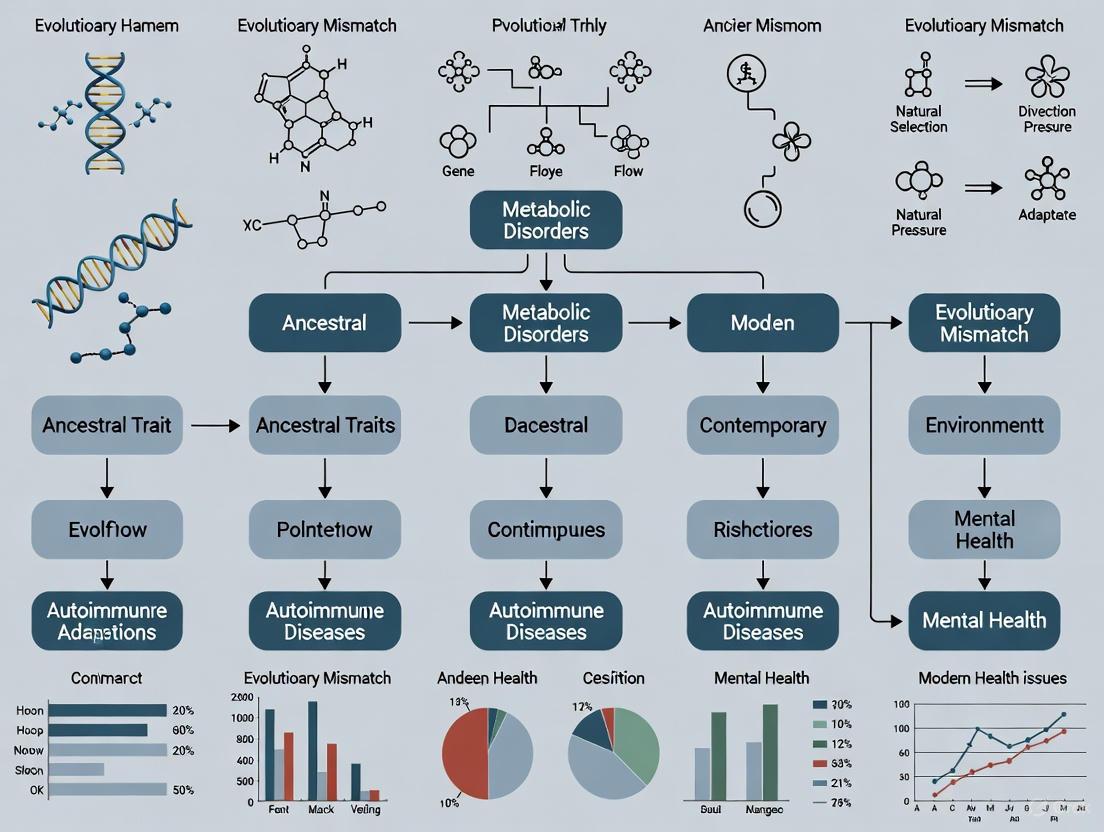

Visualizing the Core Mismatch Logic and Genetic Models

The following diagrams encapsulate the fundamental logical relationships of the mismatch hypothesis and its genetic underpinnings.

The Mismatch Logic Pathway

This diagram illustrates the causal pathway from environmental change to the manifestation of disease, highlighting key decision points for validation.

Genetic Models of Evolutionary Mismatch

At the genetic level, the core prediction of the mismatch hypothesis is the GxE interaction. This diagram models how the fitness or health effect of an allele flips between the ancestral and novel environments.

The interplay between genetic evolution and cultural and technological change represents a fundamental dynamic in human history, with profound implications for modern health. Genetic evolution operates on timescales of generations through changes in allele frequencies, driven by mechanisms such as natural selection, genetic drift, mutation, and gene flow [7]. In contrast, cultural and technological revolution represents periods of rapid technological progress characterized by innovations whose rapid application and diffusion cause abrupt changes in society [8]. This whitepaper examines the differential paces of these change processes and explores the emerging field of evolutionary mismatch theory, which posits that discrepancies between our evolved biology and modern environments created by rapid technological change contribute to contemporary health challenges. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these dynamics opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention by identifying the specific mechanisms through which our ancestral biology maladaptively interacts with modern environments.

Genetic Evolution: Mechanisms and Timescales

Core Mechanisms of Genetic Change

Genetic evolution in human populations follows established principles of population genetics, with several key mechanisms driving changes in allele frequencies over time:

Natural Selection: The process by which populations adapt to their environment through differential survival and reproduction based on heritable traits. This operates on three main principles: variation in the population, heritability of traits, and differential reproduction based on those traits [7]. Selection can be directional (favoring one extreme), stabilizing (favoring average traits), or disruptive (favoring both extremes) [7].

Genetic Drift: Random changes in gene frequency over time, particularly impactful in small populations. This includes the bottleneck effect (significant population reduction leading to loss of genetic variation) and founder effect (establishment of new population by small group) [7]. Genetic drift can lead to loss of genetic variation, fixation of alleles, and genetic divergence between populations [7].

Mutation and Gene Flow: Mutation generates new genetic variants at a rate typically measured as mutations per generation, while gene flow introduces genetic variation through movement of individuals between populations [7]. The change in allele frequency due to mutation can be represented by the equation: Δp = μ(1-p) - νp, where Δp is the change in allele frequency, μ is the mutation rate from wild-type to mutant allele, ν is the mutation rate from mutant to wild-type allele, and p is the frequency of the wild-type allele [7].

Timescales of Human Genetic Evolution

Human genetic evolution operates on extended timescales, with evidence indicating that all humans share a common ancestor who lived approximately 200,000 years ago in Eastern Africa [9]. Much of the genetic variation observed in human populations today developed within the past 50,000 to 70,000 years, after the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa [9]. As a long-lived species with generation times of approximately 20 years, observable intergenerational genetic change in humans is minimal—only two reproductive generations have passed since the discovery of DNA's structure [9].

Table 1: Timescales of Key Evolutionary Processes in Humans

| Evolutionary Process | Typical Timescale | Key Characteristics | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allele Frequency Shifts | Centuries to millennia | Slow, incremental change in response to environmental pressures | Light skin pigmentation alleles in Europeans [10] |

| Polygenic Adaptation | Millennia | Selection acting on many genetic loci with small effects | Standing height evolution in ancient populations [10] |

| Major Genetic Innovations | Tens to hundreds of thousands of years | Rare mutations that confer significant advantages | Evolution of lactose persistence in pastoral societies |

| Physiological Adaptations | Generations to centuries | Two-tiered defence: behavioural flexibility and physiological mechanisms [9] | High-altitude adaptations in Tibetan populations |

Cultural and Technological Revolution: Accelerated Change

Characteristics of Technological Revolutions

Cultural and technological revolutions represent periods of accelerated change that differ fundamentally from genetic evolution in pace and mechanism. A technological revolution is defined as "a period in which one or more technologies is replaced by another new technology in a short amount of time" [8]. These revolutions are characterized by:

- Strong interconnectedness and interdependence of participating systems in their technologies and markets

- Capacity to greatly affect the rest of the economy and eventually society

- Progress that is not linear but undulatory [8]

Technological revolutions historically focus on cost reduction through new cheap inputs, new products, and new processes [8]. The expansion of the internet, for instance, was facilitated by inexpensive microelectronics that enabled widespread computer development [8].

Historical and Contemporary Technological Revolutions

The modern era has witnessed several universal technological revolutions that have transformed human societies:

- Industrial Revolution (1760-1840): Transition to new manufacturing processes

- Technical Revolution/Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1920): Expansion of electricity, telecommunications, and transportation systems

- Scientific-Technical Revolution (1940-1970): Advances in computing, nuclear technology, and space exploration

- Information and Telecommunications Revolution (1975-2021): Digital transformation through computing and connectivity [8]

We are currently experiencing what many term the Fourth Industrial Revolution, characterized by technologies that combine hardware, software, and biology (cyber-physical systems), with breakthroughs in robotics, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, quantum computing, biotechnology, Internet of Things, and 3D printing [8].

Table 2: Comparative Pace of Change: Genetic vs. Technological Evolution

| Parameter | Genetic Evolution | Cultural/Technological Revolution |

|---|---|---|

| Rate of Change | Generational (20+ years per cycle) | Rapid (years to decades) |

| Transmission Mechanism | Biological inheritance | Learning, imitation, education |

| Directionality | Undirected (random mutation) | Directed (intentional innovation) |

| Reversibility | Essentially irreversible | Potentially reversible |

| Environmental Buffering | Requires genetic adaptation | Uses technology and cultural practices [9] |

| Key Examples | Skin pigmentation changes over millennia [10] | Digital revolution over decades [8] |

Evolutionary Mismatch and Modern Human Health

Theoretical Framework of Evolutionary Mismatch

Evolutionary mismatch occurs when traits that were evolved in one environment become maladaptive in another [11]. This framework is particularly relevant for understanding modern human health challenges, as many diseases of civilization represent mismatches between our Paleolithic biology and contemporary environments. Humans have developed extensive dependence on culture and technology that has allowed occupation of extreme environments worldwide, but this very capacity creates novel disease patterns [9].

The concept of culture can be defined as "shared, learned social behavior, or a non-biological means of adaptation that extends beyond the body" [9]. While this cultural adaptation has been spectacularly successful in allowing global colonization, it has also created environments dramatically different from those in which our species evolved.

Digital Evolutionary Mismatch

Recent research has identified computer-mediated communication (CMC) as a potential evolutionary mismatch, though with complex effects on mental health [11]. Theoretical efforts to explain mixed evidence linking CMC to mental health have lacked critical insights from anthropology and evolutionary medicine, which contextualize human health problems in relation to the discrepancy between features of human ancestral environments and contemporary industrialized lifestyles [11].

This relationship is complicated by: (a) failure to contextualize negative mental health effects of CMC against broader societal factors (e.g., family nuclearization) which are plausible preexisting evolutionary mismatches themselves; and (b) ignoring positive effects of CMC in mitigating these mismatches [11]. This perspective serves as an antidote to overpathologization of novel behaviors facilitated by CMC [11].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Ancient DNA Analysis for Tracking Genetic Evolution

The advent of ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis has revolutionized our ability to track genetic evolution directly across time. This methodology allows researchers to observe changes in allele frequencies in past populations and test hypotheses about natural selection.

Protocol 1: Ancient DNA Extraction and Sequencing for Trait Analysis

- Sample Collection: Obtain archaeological remains (teeth, petrous bone) under controlled conditions to minimize contamination

- DNA Extraction: Perform extraction in dedicated aDNA facilities with physical isolation, UV irradiation, and bleach decontamination

- Library Preparation: Build sequencing libraries with dual-indexing to track individual samples

- Target Enrichment: Use in-solution hybridization capture to enrich for trait-associated SNPs identified through GWAS

- Sequencing: Perform shallow genome sequencing (0.1-1x coverage) on high-throughput platforms

- Authentication: Assess aDNA authenticity through damage patterns, fragment length, and mitochondrial DNA analysis

- Genotype Calling: Use probabilistic methods to account for low coverage and damage

- Trait Prediction: Apply polygenic risk scores to estimate phenotypic traits in ancient individuals [10]

Limitations and Considerations: Predictions are most accurate for populations closely related to the original GWAS cohort and can vary within populations due to age, sex, and socioeconomic status [10]. For pigmentation, which is among the least polygenic complex traits, predictions are more reliable than for highly polygenic traits like height [10].

Detecting Selection in Ancient and Modern Genomes

Protocol 2: Testing for Polygenic Adaptation

- GWAS Summary Statistics: Obtain effect sizes and frequencies for trait-associated SNPs from large biobanks

- Ancient Genotype Data: Compile genotype data from ancient individuals spanning different time periods

- Polygenic Score Calculation: Compute polygenic scores for ancient individuals: PGS = Σ(βi * Gi), where βi is the effect size of SNP i and Gi is the genotype

- Temporal Analysis: Compare PGS across time periods to identify directional changes

- Selection Tests: Apply tests like the singleton density score (SDS) or time-series tests to detect selection signatures

- Validation: Where possible, compare genetic predictions with skeletal or archaeological evidence (e.g., femur length for stature) [10]

Application Example: This approach has revealed that ancient West Eurasian populations were more highly differentiated for height than present-day populations, and more so than predicted from genetic drift alone [10]. Cox et al. (2021) found that polygenic scores for height predict 6.8% of the observed variance in femur length in ancient skeletons, approximately one quarter of the predictive accuracy in present-day populations [10].

Assessing Technological Impact on Biology

Protocol 3: Measuring Evolutionary Mismatch in Modern Populations

- Identify Potential Mismatch: Select a trait with known evolutionary history that may be maladaptive in modern environments (e.g., reward pathways in digital environments)

- Physiological Measurement: Quantify biological responses to modern stimuli (cortisol levels, inflammatory markers, neural activity via fMRI)

- Comparative Baseline: Establish ancestral baseline through anthropological study of contemporary hunter-gatherer populations or historical records

- Health Outcome Correlation: Measure association between trait expression and health outcomes in modern environments

- Intervention Testing: Develop and test interventions to mitigate mismatch effects

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evolutionary Mismatch Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of DNA from archaeological specimens | Modified silica-based protocols with uracil-DNA-glycosylase treatment to remove damage | Analysis of selection in ancient populations [10] |

| Whole-Genome Capture Arrays | Enrichment of ancient DNA libraries for human genomic content | Custom-designed biotinylated RNA baits covering entire genome | Efficient sequencing of degraded samples [10] |

| Polygenic Risk Score Calculators | Estimation of genetic predisposition for complex traits | Software implementing PRS = Σ(βi * Gi) with clumping and thresholding | Tracking trait evolution over time [10] |

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) Protocols | Recovery of genetic material from sediments | Calcium phosphate precipitation for enhanced recovery | Contextualizing human evolution in past ecosystems |

| Digital Phenotyping Tools | Passive measurement of human behavior in digital environments | Smartphone sensors, keyboard dynamics, usage patterns | Quantifying technology-behavior interactions [11] |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Innovation

Understanding the pace differential between genetic evolution and technological change provides critical insights for modern drug development. The evolutionary mismatch framework suggests several strategic approaches:

- Target Identification: Mismatch theories can identify novel therapeutic targets by highlighting physiological systems maladapted to modern environments (e.g., stress response systems in constant digital connectivity) [11]

- Clinical Trial Design: Incorporate evolutionary perspectives in participant selection and outcome measures, considering how genetic backgrounds shaped by different ancestral environments may respond differently to interventions

- Prevention Strategies: Develop interventions that mitigate mismatch effects rather than merely treating symptoms, including digital therapeutics that address technology-induced stress

- Personalized Medicine: Apply ancient DNA insights to understand population-specific disease risks and treatment responses, moving beyond European-centric genetic databases [10]

The rapid pace of technological change suggests that drug development must account for continuously evolving environmental contexts, particularly in mental health where digital technologies create novel cognitive demands and stress patterns [11]. By recognizing that human biology evolves slowly while our environment changes rapidly, researchers can better anticipate future health challenges and develop proactive therapeutic strategies.

Evolutionary mismatch provides a powerful unifying framework for understanding the high prevalence of certain non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in modern, industrialized environments [12] [4]. This concept posits that human biology, shaped by millennia of evolution in contexts vastly different from our modern world, is often inadequately adapted to contemporary lifestyles, leading to disease [13] [14]. This whitepaper examines three key phenotypic examples—the Thrifty Genotype, the Hygiene Hypothesis, and sedentary lifestyles—that illustrate this mismatch. We detail the underlying evolutionary principles, synthesize current research findings into actionable data, and provide methodologies for investigating these phenomena. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mismatches is critical for identifying novel therapeutic targets, developing more physiologically relevant animal models, and designing effective, evolutionarily-informed public health interventions. The evidence underscores that many modern NCDs, including cardiometabolic and immune-dysregulatory conditions, are not merely products of modern life but represent a fundamental discordance between our ancestral biology and our current environment [12] [4].

The Evolutionary Mismatch Framework

The evolutionary mismatch hypothesis states that a condition becomes more common or severe because an organism is imperfectly adapted to a novel environment [4]. For humans, this "novel environment" is the post-industrial lifestyle, characterized by abundant processed food, low physical activity, and decreased exposure to a diverse microbiota [13] [14]. This contrasts sharply with the conditions under which the human lineage evolved.

To rigorously test for an evolutionary mismatch, three criteria must be established [4]:

- Disease Differential: The condition must be more common or severe in the novel environment compared to a proxy for the "ancestral" environment.

- Environmental Driver: The phenotype must be linked to a specific, measurable environmental variable that differs between ancestral and modern contexts.

- Mechanistic Pathway: A clear biological mechanism must connect the environmental shift to the disease-related phenotype.

A powerful approach to studying mismatch involves partnerships with subsistence-level populations undergoing rapid lifestyle change [12] [4] [15]. These groups provide a quasi-natural experiment, allowing for direct comparisons between individuals living more traditional ("matched") lifestyles and those living more modern ("mismatched") lifestyles within a shared genetic and cultural background. Studies with the Orang Asli of Malaysia and the Turkana are prime examples of this methodology [12] [4] [15].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow from ancestral to modern environments and the resulting phenotypic consequences that constitute an evolutionary mismatch.

The Thrifty Genotype Hypothesis

Core Concept and Evolution

The Thrifty Genotype Hypothesis (TGH), proposed by James Neel in 1962, was one of the first formal evolutionary explanations for a modern NCD [12]. It posits that genetic variants promoting efficient fat storage and energy conservation ("thrifty" alleles) were historically advantageous. Individuals carrying these alleles would have had a survival and reproductive advantage during frequent periods of famine or resource scarcity. However, in modern environments with constant caloric abundance and low energy expenditure, these once-beneficial alleles now predispose individuals to obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes [12] [15]. This represents a classic genotype-by-environment (GxE) interaction, where the health effect of a genotype depends entirely on the environment.

While highly influential, the TGH has faced critiques and updates. Some researchers question whether famines were a strong enough selective force in human evolution, suggesting that the observed thriftiness may be a byproduct of other human-specific traits, such as large, energetically costly brains [12]. This has led to the development of related hypotheses, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Alternative and Related Evolutionary Hypotheses for Metabolic Disease

| Hypothesis | Proposed Mechanism | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Thrifty Genotype [12] | Positive selection for energy-efficient alleles in feast-famine cycles. | High heritability of T2D; genetic loci linked to energy metabolism. |

| Drifty Genotype [12] | Neutral genetic drift in the absence of selection against obesity after loss of predation pressure. | Modeling of selective pressures; inconsistent evidence for famine as a major driver. |

| Thrifty Phenotype [12] | Developmental plasticity in response to early-life undernutrition, increasing disease risk in later life. | Strong epidemiological link between low birth weight and adult metabolic syndrome. |

| Evolutionary Mismatch [12] [4] | Broad mismatch between evolved biology and modern lifestyle (diet, activity), not limited to specific genotypes. | Rapid rise in NCDs with urbanization; studies of subsistence populations. |

Quantitative Data from Transitioning Populations

Research with transitioning populations provides critical phenotypic data supporting the mismatch concept. The Orang Asli Health and Lifeways Project (OA HeLP) has documented a gradient of lifestyle change correlated with health outcomes [15]. Key findings are synthesized in the table below.

Table 2: Lifestyle and Health Indicators Across a Gradient of Modernization (Orang Asli Example)

| Lifestyle Metric | Traditional (Matched) | Transitional | Urbanized (Mismatched) | Measured Health Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Meat Intake | High (e.g., >60% of diet) | Decreasing rapidly | Very Low | Correlated with lower body fat and waist circumference [15]. |

| Sugar Intake | Very Low | Increasing | High | Associated with increased risk of obesity and T2D [15]. |

| Physical Activity | High (foraging, hunting) | Variable | Low (sedentary wage labor) | Directly linked to cardiometabolic risk factors [4]. |

| Visits to Urban Centers | Rare/Few | Occasional | Frequent | Serves as a proxy for market integration and lifestyle change [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Genotype-by-Environment (GxE) Interaction Mapping

Objective: To identify genetic loci associated with cardiometabolic traits that show interaction effects with a "modernity" index in a transitioning population.

Methodology:

- Cohort Establishment: Partner with a subsistence-level population experiencing lifestyle variation (e.g., Orang Asli, Turkana) [12] [4]. Obtain informed consent and ethical approval.

- Phenotypic Data Collection:

- Cardiometabolic Traits: Measure BMI, waist circumference, body fat percentage, fasting blood glucose, insulin, HbA1c, and lipid profiles.

- Lifestyle "Modernity" Index: Construct a continuous index based on dietary recalls (e.g., % calories from market foods), physical activity monitors, and survey data (e.g., formal education, urban exposure) [15].

- Genotyping: Perform genome-wide sequencing or SNP array genotyping on all participants.

- Statistical Analysis:

- GxE Scan: Employ a linear mixed model for each SNP:

Trait ~ SNP + Modernity_Index + SNP*Modernity_Index + Covariates + (Relatedness Matrix). Covariates include age, sex. - Significance Threshold: Apply a genome-wide significance threshold (e.g., p < 5x10^-8) for the interaction term.

- Validation: Replicate significant GxE interactions in an independent cohort, if available.

- GxE Scan: Employ a linear mixed model for each SNP:

Expected Outcome: Identification of specific genetic variants where the effect on cardiometabolic health is significantly stronger in individuals with a more modern lifestyle, providing molecular evidence for the thrifty genotype and mismatch hypotheses [4].

The Hygiene Hypothesis and Immune Function

From Hygiene to "Old Friends"

The original Hygiene Hypothesis, proposed by Strachan in 1989, observed an inverse relationship between family size (and presumed microbial exposure) and the incidence of hay fever [16] [17]. It suggested that a lack of early childhood infections could lead to improper immune system development and a higher risk of allergic disease [16].

This hypothesis has since been refined into the "Old Friends" Hypothesis (or microflora hypothesis) [16] [18]. This updated theory posits that it is not childhood infections per se, but rather the lack of exposure to harmless microorganisms and macroorganisms with which humans co-evolved throughout history that is critical. These "old friends" include:

- Environmental saprophytes (e.g., mycobacteria in soil and water) [18].

- Commensal microbiota that colonize the gut, skin, and respiratory tracts [16] [19].

- Chronic infections and parasites, such as helminths, that established a state of commensalism or carrier state [16] [18].

The "Old Friends" are thought to have been essential for the proper development of immunoregulatory pathways. Their relative absence in modern, hygienic environments is hypothesized to lead to a failure to adequately control inflammatory responses, thereby increasing susceptibility to allergic, autoimmune, and other inflammatory disorders [16] [17] [18].

Molecular Mechanisms and Recent Findings

The immunological mechanism has evolved from a simple T-helper 1 (Th1) versus Th2 balance to a more complex model involving regulatory T cells (Tregs) and their cytokines, particularly IL-10 and TGF-β [16] [17]. The "Old Friends" are proposed to stimulate immunoregulatory circuits, which suppress inappropriate inflammation directed against harmless allergens (allergy) or self-tissues (autoimmunity) [17].

Recent groundbreaking research has identified a specific molecular pathway that may underlie the protective effects of helminth infection. The pathway, triggered by the cytokine IL-25, leads to long-lasting mucosal immunity and improved metabolic outcomes [20].

Source: Adapted from Cortez et al. (2025) [20].

Experimental Protocol: Helminth-Induced Immunomodulation

Objective: To evaluate the therapeutic potential of a defined helminth excretory/secretory (ES) product in a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation.

Methodology:

- Animal Model: Use 6-8 week old female C57BL/6 mice. House under specific pathogen-free conditions.

- Helminth Product: Purify ES products from the nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus (H. polygyrus) culture.

- Sensitization & Treatment:

- Group 1 (Treatment): Sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin (OVA) or house dust mite (HDM) extract. Receive intraperitoneal injection of H. polygyrus ES (e.g., 10μg) at sensitization and/or challenge phases [16].

- Group 2 (Disease Control): Sensitized and challenged with OVA/HDM. Receive vehicle control (PBS).

- Group 3 (Naive Control): Receive PBS only.

- Outcome Measures (24-48 hrs post-final challenge):

- Airway Hyperreactivity: Measure using invasive plethysmography in response to methacholine.

- Cellular Influx: Perform bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and conduct differential cell counts (eosinophils, neutrophils, lymphocytes).

- Cytokine Profile: Analyze BAL fluid and restimulated lung cell culture supernatants for Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13) and immunoregulatory cytokines (IL-10) via ELISA.

- Lung Histopathology: Score sections stained with H&E for peribronchial and perivascular inflammation, and PAS for goblet cell hyperplasia.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare groups using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests (e.g., Tukey's). Significance at p < 0.05.

Expected Outcome: The group treated with helminth ES products is expected to show significant reductions in airway hyperreactivity, eosinophilic inflammation, Th2 cytokines, and lung pathology compared to the disease control group, demonstrating the anti-inflammatory capacity of defined parasitic molecules [16].

Sedentary Lifestyles as a Mismatch

Quantifying the Mismatch and Its Health Impacts

Prolonged physical inactivity represents a profound deviation from the high-activity lifestyles that were the norm throughout human evolution. To operationalize this concept for research, the Evolutionary Mismatched Lifestyle Scale (EMLS) has been developed [13]. This 36-item questionnaire assesses an individual's deviation from ancestral lifestyle norms across seven domains, including Physical Activity and Diet.

Studies using this and similar tools have consistently linked higher mismatch scores to poorer health outcomes [13] [14]. Individuals with higher EMLS scores are more likely to report:

- Poorer subjective physical health.

- More sleep problems and chronic illnesses.

- Poorer mental well-being, including higher levels of depression and anxiety [13].

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic and Inflammation Studies

The following table details key reagents and models for investigating the biology of sedentary behavior and metabolic health.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Sedentary Lifestyle Biology

| Reagent / Model | Function/Description | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| IL-25 Cytokine [20] | A tuft-cell derived cytokine that activates ILC2s and confers multi-tissue immune and metabolic benefits. | Studying the immune-metabolism axis; potential therapeutic for obesity and infection resistance [20]. |

| Mouse Model of Diet-Induced Obesity (DIO) | C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat, high-sugar diet to mimic Western diets. | Standard model for studying obesity, insulin resistance, and NAFLD. |

| Forced/Voluntary Exercise Wheels | In-cage running wheels for rodents to allow controlled or voluntary exercise. | Comparing effects of exercise vs. sedentarism on physiology and brain function in controlled settings. |

| Human Myotube Cell Culture | Differentiated skeletal muscle cells from human biopsies. | In vitro study of muscle metabolism, insulin signaling, and the effects of exercise-mimetic compounds. |

| Activity Monitors (Accelerometers) | Wearable devices to objectively measure physical activity and sedentary time in human studies. | Quantifying the "activity" component of the EMLS in epidemiological and intervention studies [13]. |

| "Old Friends" Mimetics | Defined molecules from commensals or parasites (e.g., helminth ES products, probiotic lysates). | Experimental tools to recapitulate the immunoregulatory effects of missing microbial exposures [16] [17]. |

The phenotypic examples of the Thrifty Genotype, the Hygiene/"Old Friends" Hypothesis, and sedentary lifestyles collectively provide compelling evidence for the overarching framework of evolutionary mismatch. They illustrate how genetic adaptations, immune development, and daily activity patterns honed in our past are now interacting maladaptively with modern environments, driving the global burden of NCDs.

For the field to advance, future research must:

- Prioritize GxE Mapping: Intensify efforts to identify specific genetic variants that interact with modern lifestyle factors, using well-designed studies in transitioning populations [12] [4].

- Embrace Mechanism: Move beyond correlation to define precise molecular pathways, such as the IL-25/ILC2 axis, that mediate the health benefits of "matched" lifestyles [20].

- Develop "Mimetic" Therapeutics: Translate mechanistic insights into novel therapeutic strategies, such as defined "Old Friends" molecules or exercise mimetics, that can safely recapitulate the protective effects of ancestral exposures [16] [14] [20].

- Refine Public Health Strategies: Integrate the evolutionary mismatch narrative into patient education and public health messaging to provide a compelling "why" that may improve adherence to lifestyle interventions [14].

By adopting an evolutionary perspective, researchers and drug developers can fundamentally re-frame their approach to modern diseases, leading to more predictive models, more effective treatments, and ultimately, a more profound understanding of human health.

The concept of evolutionary mismatch provides a critical framework for understanding many contemporary health challenges. This theory posits that human biology, shaped over millennia by natural selection to thrive in specific ancestral environments, is now operating in modern conditions that are profoundly different from those for which it was adapted [21]. This mismatch between our evolved physiology and contemporary lifestyles is now recognized as a significant contributor to the rising prevalence of chronic diseases [22]. This whitepaper examines three fundamental pillars of this mismatch: dietary composition, physical activity patterns, and microbial exposures. Through a systematic analysis of contrasts between ancestral and modern environments, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive biological context for understanding disease etiology and identifying novel therapeutic targets. The evidence presented underscores that many modern health pathologies, from inflammatory diseases to metabolic disorders, may stem from these discontinuities with our evolutionary past.

Dietary Shifts: From Whole Foods to Ultra-Processed Diets

Quantitative Comparison of Nutritional Profiles

The transition from ancestral to modern diets represents one of the most dramatic environmental shifts in human history. Ancestral diets were characterized by whole, unprocessed foods, while modern industrialized diets are dominated by ultra-processed foods (UPFs), which have become the primary calorie source for many populations [23]. The table below summarizes the key nutritional differences:

Table 1: Nutritional Comparison of Ancestral versus Modern Diets

| Nutrient/Component | Ancestral Diet | Modern Diet | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Fiber | High (>70g/day) [24] | Low (<15g/day in Western diets) [24] | Reduced gut microbial diversity; impaired SCFA production |

| Added Sugars | Minimal [25] | High (~13% of total calories) [25] | Promotes inflammation, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome |

| Saturated Fats | Moderate, from wild sources [25] | High, from processed and industrialized sources [25] | Alters lipid metabolism; promotes chronic inflammation |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | High (EPA/DHA) [23] | Low [25] | Reduced anti-inflammatory capacity; impaired brain function |

| Phytonutrients | High diversity (>8,000 compounds) [23] | Limited diversity [23] | Diminished antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protection |

| Protein Diversity | Varied sources [23] | Limited sources [23] | Reduced amino acid spectrum; potential micronutrient gaps |

Impact on the Human Metabolome

The reduction in dietary complexity has profound implications for the human metabolome. Current research indicates the human metabolome consists of approximately 248,097 metabolites, with approximately 32,366 (13%) being food-derived compounds [23]. This makes diet the largest exogenous contributor to the metabolome, far exceeding drugs and their metabolites at 1.3%. The shift to UPFs has substantially diminished the magnitude and diversity of the modern metabolome compared to our evolutionary metabolome, potentially contributing to the rise in chronic diseases [23]. The evolutionary diet contributed to a more diverse metabolome that supported optimal gene expression and metabolic function, aspects that are compromised in modern dietary patterns.

Experimental Protocols for Dietary Mismatch Research

Protocol 1: Metabolomic Profiling of Ancestral vs. Modern Diets

- Sample Collection: Obtain fecal and plasma samples from controlled feeding studies comparing whole food diets versus ultra-processed diets.

- Metabolite Extraction: Use methanol:water (4:1) extraction for broad-spectrum metabolite recovery.

- LC-MS Analysis: Perform liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with reverse-phase and HILIC chromatography for comprehensive coverage.

- Data Processing: Utilize XCMS or MZmine for peak detection, alignment, and identification against databases (HMDB, MetLin).

- Statistical Analysis: Apply multivariate statistics (PCA, OPLS-DA) to identify differentially abundant metabolites.

Protocol 2: Gut Barrier Function Assessment

- Intestinal Permeability: Administer lactulose/mannitol sugar test and measure urinary excretion ratios.

- Tight Junction Protein Expression: Analyze occludin, ZO-1, and claudin protein levels in intestinal biopsy samples via Western blot.

- Inflammatory Markers: Measure plasma LPS, LBP, and IL-6 levels via ELISA.

- Microbiome Correlation: Perform 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal samples to correlate bacterial taxa with permeability measures.

Evolutionary Activity Patterns vs. Modern Sedentism

Human physiology evolved under conditions requiring substantial daily physical exertion for survival. Hunter-gatherer populations typically engaged in 4-6 hours of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily, with males expending approximately 2,600-3,000 kcal/day and females 1,900-2,200 kcal/day [26]. This activity was characterized by varied movement patterns including walking, running, carrying, digging, and climbing, performed in natural environments with seasonal fluctuations in intensity [26]. In stark contrast, modern industrialized populations average <30 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity daily, with many individuals classified as completely sedentary [27]. This represents a fundamental mismatch with our evolved activity requirements.

Biological Consequences of Activity Mismatch

The transition to sedentary lifestyles has profound physiological consequences, primarily mediated through inflammatory pathways. Regular physical activity is a potent regulator of systemic low-grade chronic inflammation (SLGCI), with sedentary behavior promoting a pro-inflammatory state [27]. The mechanisms include:

- Reduced anti-inflammatory myokine production (e.g., IL-6, IL-10, IL-1ra) from muscle

- Accumulation of visceral adipose tissue, a significant source of pro-inflammatory cytokines

- Dysregulation of the HPA axis and increased stress reactivity

- Impaired mitochondrial function and increased oxidative stress

Evidence indicates that the relationship between physical activity and mental health follows an inverted U-shaped curve, with both sedentary behavior and excessive exercise associated with increased inflammatory markers and depressive symptoms [27]. This highlights the importance of activity patterns that align with our evolutionary template.

Visualization of Activity-Inflammation Pathways

Figure 1: Biological Pathways Linking Physical Activity Patterns to Inflammatory States

Microbial Exposures: The Disappearing Microbiome

Comparative Microbiome Analysis

The human microbiome represents a critical interface between environment and biology, having co-evolved with humans over millennia. Contemporary research reveals significant differences between ancestral and modern microbiomes, supporting the "disappearing microbiome" hypothesis [24]. Western industrialized populations show 15-30% reduced microbial species richness compared to non-Western populations following traditional subsistence lifestyles [24]. Key compositional differences include the loss of specific taxa such as Treponema, Prevotella, Catenibacterium, Succinivibrio, and Methanobrevibacter in Westernized populations [28] [24].

Table 2: Microbial Taxa Differences Between Ancestral and Modern Populations

| Taxon/Parameter | Ancestral/Traditional | Modern/Westernized | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species Richness | High [24] | 15-30% lower [24] | Reduced metabolic capacity; diminished ecosystem resilience |

| Treponema | Present in diverse populations [24] | Largely absent [24] | Loss of fiber degradation specialists |

| Prevotella | Higher abundance [28] | Reduced abundance [28] | Reduced complex carbohydrate metabolism |

| Bacteroides | Lower relative abundance [24] | Higher relative abundance [24] | Shift toward mucin degradation in fiber-deprived environment |

| Bifidobacterium | Robust presence, especially in infants [28] | Variable, often reduced [28] | Impaired HMO metabolism; early immune dysregulation |

| Microbial Gene Diversity | High [28] | Reduced [28] | Narrowed functional repertoire for metabolite production |

Mechanisms of Microbial Loss and Functional Consequences

The disappearance of ancestral microbial lineages is driven by multiple factors in modern environments: dietary changes (reduced fiber, increased processing), hygiene and sanitation, antibiotic usage, reduced contact with natural environments, and declining maternal microbial transmission [28] [24]. The functional consequences are profound, as the gut microbiome plays essential roles in nutrient synthesis, xenobiotic metabolism, immune system development, and mucosal barrier maintenance [28].

Of particular concern is the impact on immune function. Microbial exposures in ancestral environments promoted appropriate immune development, while modern reduced exposures are associated with increased inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. The microbiome also modulates brain function and behavior through the gut-brain axis, with implications for psychiatric disorders including depression [27].

Experimental Protocols for Microbiome Research

Protocol 1: Multi-omics Microbiome Analysis

- Sample Collection: Collect fecal samples in DNA/RNA stabilizing buffer, immediately freeze at -80°C.

- DNA Extraction: Use bead-beating enhanced extraction (e.g., MoBio PowerSoil kit) for comprehensive lysis.

- 16S rRNA Sequencing: Amplify V4 region with dual-indexing, sequence on Illumina platform, process with QIIME2 or mothur.

- Shotgun Metagenomics: Perform library preparation with Nextera XT, sequence on Illumina NovaSeq, analyze with HUMAnN2 and MetaPhlAn.

- Metabolomic Profiling: Conduct LC-MS on fecal water and plasma; integrate with microbial data.

Protocol 2: Gut-on-a-Chip Barrier Function Assay

- Device Setup: Use Emulate or similar microfluidic system with human intestinal epithelial cells.

- Microbial Conditioning: Introduce ancestral vs. modern microbial communities in luminal channel.

- Permeability Measurement: Apply FITC-dextran and measure transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER).

- Cytokine Profiling: Collect effluent from basal channel for multiplex cytokine analysis.

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Recover cells for RNA sequencing to evaluate barrier and immune function genes.

Research Reagents and Methodological Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evolutionary Mismatch Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolomics Standards | HMDB quantitative standards; Cayman Chemical metabolite panels | Metabolite identification and quantification | Use isotope-labeled internal standards for precise quantification |

| Microbiome Standards | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standards; BEI Resources strains | Method validation and cross-study comparison | Include both mock communities and defined consortia |

| Cell Culture Models | Caco-2 intestinal barrier model; HuMiX gut-on-a-chip systems | Host-microbe interaction studies | Primary cells preferred over immortalized lines when possible |

| Immunoassays | Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) multi-array cytokine panels; ELISA kits for LPS, LBP, sCD14 | Inflammatory pathway assessment | MSD provides superior dynamic range for cytokine measurement |

| DNA Sequencing Kits | Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation; KAPA HyperPlus for shotgun metagenomics | Microbiome composition and function | Preserve sample integrity with immediate freezing or stabilization |

| Gnotobiotic Systems | Germ-free mice; humanized microbiome mouse models | Causal mechanism testing | Allow adequate acclimation period after microbial transplantation |

| Physical Activity Monitoring | ActiGraph wGT3X-BT; activPAL; heart rate variability monitors | Objective activity measurement | Combine accelerometry with physiological monitoring when possible |

The evidence for evolutionary mismatch across dietary patterns, physical activity, and microbial exposures provides a powerful framework for understanding modern disease etiology. The contrasts between ancestral and modern environments reveal fundamental discontinuities that contribute to the rising burden of chronic inflammatory, metabolic, and psychiatric disorders [23] [27] [24]. For drug development professionals and researchers, this evolutionary perspective offers critical insights for identifying novel therapeutic targets and developing more effective intervention strategies.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies that track the transition from traditional to modern lifestyles, mechanistic investigations using gnotobiotic and organoid systems, and clinical trials that test evolutionary medicine-informed interventions. Particularly promising areas include targeting the gut-brain axis for psychiatric disorders, manipulating microbial communities to restore ancestral functions, and developing exercise-mimetic therapies for those unable to engage in physical activity. By integrating evolutionary principles with modern biomedical research, we can advance toward a more comprehensive understanding of human health and disease.

Evolutionary Mismatch as a Unifying Framework for Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs)

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) represent one of the most significant global health challenges of the 21st century. According to World Health Organization estimates, NCDs were responsible for 41 million deaths annually—accounting for 71% of all global deaths [29]. The four major NCD categories—cardiovascular diseases (17.9 million deaths), cancers (9.0 million), chronic respiratory diseases (3.8 million), and diabetes (1.6 million)—drive both substantial mortality and healthcare costs worldwide [29]. Perhaps most alarmingly, NCDs are increasingly responsible for premature mortality, with 75% of deaths among adults aged 30-69 years attributable to these conditions [29].

The evolutionary mismatch hypothesis provides a powerful unifying framework for understanding this pandemic. This hypothesis posits that humans evolved in environments that radically differ from those we currently experience; consequently, traits that were once advantageous may now be "mismatched" and disease-causing [6] [4]. This review synthesizes current research on evolutionary mismatch as it relates to NCD etiology, presents methodological approaches for its study, and explores its implications for therapeutic development.

Theoretical Foundations of Evolutionary Mismatch

Core Principles and Definitions

The evolutionary mismatch framework explains disease susceptibility through a fundamental discordance between our evolved biology and modern environments. At the genetic level, this hypothesis predicts that loci with a history of selection will exhibit "genotype by environment" (GxE) interactions, with different health effects in "ancestral" versus "modern" environments [6]. Three criteria must be satisfied to establish an evolutionary mismatch:

- Disease differential: The condition must be more common or severe in novel versus ancestral environments

- Environmental correlation: The disease must be tied to environmental variables that differ between these contexts

- Mechanistic pathway: A molecular or physiological mechanism must link the environmental shift to the disease condition [4]

Extended Evolutionary Synthesis and Cultural Evolution

Contemporary evolutionary medicine incorporates insights from the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis, which expands beyond the gene-centric focus of the Modern Synthesis to include cultural evolution and inclusive inheritance [29]. Unlike biological evolution driven by genetic mutation and natural selection, cultural evolution operates through transmission of information via learning, imitation, and social interaction [29]. This cultural inheritance can occur both horizontally within generations and vertically across generations.

Table: Comparing Biological and Cultural Evolution

| Characteristic | Biological Evolution | Cultural Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Primary mechanism | Genetic mutation and natural selection | Learning, imitation, social transmission |

| Inheritance system | Genetic | Cultural (ideas, behaviors, traditions) |

| Time scale | Thousands to millions of years | Rapid (within generations) |

| Selection criteria | Survival and reproduction | Human-defined goals (social, economic, technological) |

| Adaptive outcome | Biological fitness | Cultural acceptability/benefit |

Cultural evolution generates particularly potent mismatches because it operates orders of magnitude faster than genetic evolution, creating environments that diverge dramatically from those in which our physiological systems evolved [29]. Human culture in today's socio-technical world often has little in common with adaptation in the biological evolutionary sense, frequently producing unavoidable maladaptations [29].

Mechanisms Linking Mismatch to Disease

Genetic and Molecular Pathways

At the genetic level, evolutionary mismatch manifests through GxE interactions where genetic variants that were neutral or beneficial in ancestral environments become disease-predisposing in modern contexts [6] [4]. This occurs through several distinct mechanisms:

- Previously selected alleles: Variants with a history of positive selection that provided health benefits in ancestral environments but confer health detriments in modern environments

- Stabilizing selection disruptions: Intermediate alleles with similar fitness in ancestral environments where one allele becomes associated with health detriments following environmental change

- Decanalization: The unmasking of phenotypic variation when environmental shifts move populations away from evolutionary-familiar conditions [5]

These genetic mechanisms help explain the "missing heritability" problem in complex diseases, where identified genetic variants account for only a fraction of heritability, suggesting that environmental context is essential for expressing genetic risk [4].

Developmental Mismatch and Early Life Adversity

Early life represents a critical period for evolutionary mismatches with lifelong consequences. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) framework posits that early experiences program biological systems in ways that can increase susceptibility to chronic diseases later in life [30]. Early life adversity (ELA) initiates a developmental cascade through several interconnected biological systems:

Developmental Cascade Linking Early Adversity to NCD Risk

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis represents a core system affected by ELA. Chronic HPA axis hyperactivity can result in glucocorticoid resistance, where cells become less sensitive to cortisol's anti-inflammatory effects, leading to upregulated pro-inflammatory gene transcription and elevated inflammatory activity [30]. This inflammatory state, in turn, drives metabolic dysregulations that underlie many NCDs.

Methodological Approaches for Studying Evolutionary Mismatch

Study Designs for Identifying GxE Interactions

Research on evolutionary mismatch requires innovative methodological approaches that can capture GxE interactions. Traditional genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in industrialized populations have limited power to detect these interactions because environmental risk factors show minimal variability within these populations [4]. The following experimental approaches address this limitation:

Studies of subsistence-level populations undergoing rapid lifestyle change provide particularly powerful natural experiments for identifying mismatch mechanisms [4]. These populations experience extreme variation in diet, physical activity, pathogen exposure, and social conditions, creating a "matched-to-mismatched" spectrum within genetically similar groups.

Table: Key Research Initiatives Studying Evolutionary Mismatch in Transitioning Populations

| Research Project | Population | Primary Research Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Turkana Health and Genomics Project | Turkana people (Kenya) | Genomic adaptations to rapid urbanization |

| Orang Asli Health and Lifeways Project | Orang Asli (Malaysia) | Metabolic transitions with lifestyle change |

| Tsimane Health and Life History Project | Tsimane (Bolivia) | Cardiovascular aging in a high-pathogen environment |

| Shuar Health and Life History Project | Shuar (Ecuador) | Stress physiology and market integration |

| Madagascar Health and Environmental Research | Malagasy communities | Nutritional ecology and health transitions |

These studies combine long-term anthropological fieldwork with cutting-edge genomic and biomedical assessments, enabling researchers to correlate environmental changes with physiological and genetic measures [4].

Evolutionary Patterning for Drug Target Identification

Evolutionary principles can be directly applied to therapeutic development through evolutionary patterning, which identifies drug targets that minimize resistance development [31]. This approach uses the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (ω) to identify codons under the most intense purifying selection (ω≤0.1). Residues under extreme evolutionary constraint are unlikely to develop resistance mutations, making them attractive chemotherapeutic targets [31].

The evolutionary patterning workflow involves:

- Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of orthologous genes

- Selection pressure analysis to identify residues under purifying selection

- Structural modeling to evaluate functional importance and accessibility

- Experimental validation of target sites

This approach was validated by demonstrating that none of the residues providing pyrimethamine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase were under extreme purifying selection [31].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol for Evolutionary Patterning Analysis

Objective: Identify evolutionarily constrained residues in potential drug targets to minimize resistance development.

Step 1: Sequence compilation and alignment

- Retrieve orthologous sequences from genomic databases using BLAST with strict E-value cutoff (e.g., 1e-20)

- Perform multiple sequence alignment using MAFFT (algorithm G-INS-i) with BLOSUM62 matrix

- Verify alignment accuracy with HoT test

- Generate corresponding codon alignment using protein alignment as template

Step 2: Selection pressure analysis

- Perform phylogenetic analysis using maximum likelihood methods (e.g., RAxML)

- Test models of molecular evolution using ModelTest

- Calculate ω (dN/dS) ratios using codon-based models in PAML

- Identify sites under purifying selection (ω≤0.1) using Bayes Empirical Bayes analysis

Step 3: Structural analysis

- Model protein structure using homology modeling or available crystal structures

- Map evolutionarily constrained residues to structural model

- Assess solvent accessibility and functional significance of constrained regions

- Identify potential binding sites that incorporate constrained residues

Step 4: Experimental validation

- Express and purify recombinant protein for functional assays

- Test essentiality of constrained residues through site-directed mutagenesis

- Develop inhibitors targeting constrained regions

- Assess resistance development potential through experimental evolution

Protocol for Collateral Sensitivity Profiling

Objective: Identify evolutionary trade-offs where resistance to one drug confers hypersensitivity to another.

Step 1: Experimental evolution of resistance

- Establish replicate bacterial populations in laboratory media

- Expose to increasing concentrations of primary antibiotic over serial passages

- Continue evolution until significant resistance develops (typically 4-8 weeks)

- Freeze resistant strains at -80°C with glycerol preservation

Step 2: Cross-resistance profiling

- Measure minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for resistant strains against panel of 20+ antibiotics

- Include diverse drug classes: β-lactams, quinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, etc.

- Identify collateral sensitivities (hypersensitivity in resistant strains)

- Validate findings through dose-response curves

Step 3: Mechanistic studies

- Perform whole-genome sequencing of resistant strains

- Identify mutations through comparison to ancestral genotypes

- Validate causal mutations through genetic complementation

- Elucidate physiological mechanisms underlying collateral sensitivity

Step 4: Treatment strategy design

- Develop drug cycling protocols that exploit collateral sensitivity networks

- Test combination therapies that select against resistance

- Validate efficacy in animal infection models

- Optimize dosing schedules to prevent resistance emergence

Research Tools and Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Evolutionary Mismatch Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Analysis | Whole genome sequencing kits, GTEx database, UK Biobank data | Identifying GxE interactions and selection signatures |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary hepatocytes, adipocytes, immune cells | Studying metabolic and inflammatory pathways in vitro |

| Animal Models | Wild-derived mice, humanized mice, non-human primates | Modeling human physiological responses in controlled settings |

| Biomarker Assays | Multiplex cytokine panels, cortisol ELISA, metabolomic profiles | Quantifying physiological dysregulation in human studies |

| Microbiome Analysis | 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomic sequencing, gnotobiotic mice | Investigating host-microbe interactions in mismatch conditions |

Visualization of Research Workflows

Subsistence Population Research Workflow

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Clinical Practice

Drug Discovery Applications

Evolutionary principles inform several innovative approaches to drug discovery:

Collateral sensitivity networks represent a promising strategy for combating antibiotic resistance. This approach exploits the evolutionary trade-off where resistance to one drug confers hypersensitivity to another [32]. For example, evolution of resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics often produces hypersensitivity to β-lactam antibiotics [32]. These networks can inform drug cycling protocols that actively select against resistant pathogens.

Targeted protein degradation technologies, such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), represent another evolutionarily-informed therapeutic strategy [33]. These molecules harness natural degradation pathways to remove disease-causing proteins, potentially targeting proteins that have been difficult to address with conventional inhibitors.

Clinical Translation and Patient Education

An evolutionary perspective can enhance clinical practice through mismatch education that improves patient adherence to lifestyle interventions [14]. Explaining the ultimate causes of disease provides a cohesive narrative that helps patients understand why certain lifestyle recommendations are effective. This approach aligns with cognitive behavior therapy models that emphasize changing thought patterns to influence behaviors [14].

Clinical applications of evolutionary mismatch include:

- Dietary interventions based on evolutionary principles rather than temporary restrictions

- Physical activity prescriptions that acknowledge our evolutionary history as active hunter-gatherers

- Stress management techniques that address mismatches between modern stressors and ancient stress response systems

- Sleep hygiene recommendations grounded in evolutionary perspectives on natural light-dark cycles

The evolutionary mismatch framework provides a powerful unifying paradigm for understanding and addressing the growing burden of non-communicable diseases. By integrating insights from evolutionary biology, genomics, anthropology, and experimental medicine, this approach offers novel perspectives on disease etiology and therapeutic development.

Future research directions should include:

- Longitudinal studies of transitioning populations to capture dynamic GxE interactions

- Integration of multi-omics data to elucidate pathways from genetic variation to physiological dysfunction

- Development of evolutionarily-informed interventions that address mismatch at both individual and societal levels

- Refined evolutionary patterning approaches for identifying drug targets with minimal resistance potential

As the field progresses, evolutionary medicine promises to transform our approach to NCD prevention and treatment by addressing the fundamental causes of these conditions rather than merely their symptomatic manifestations.

Mapping Mismatch to Mechanisms: Genomic Tools and Partnership-Based Research Models

Studying Subsistence-Level Populations as Natural Experiments for Lifestyle Transition

The evolutionary mismatch hypothesis posits that many non-communicable diseases (NCDs) prevalent in modern societies result from a disconnect between our rapidly changed environments and the human biology shaped by millennia of evolution [4]. Under this framework, traits that were once advantageous in ancestral environments may now be "mismatched" and disease-causing in contemporary post-industrial contexts [4]. This hypothesis provides a powerful lens through which to investigate the complex genotype-by-environment (GxE) interactions underlying NCD risk, which have been notoriously difficult to map in studies confined to post-industrial populations [4].

Subsistence-level populations undergoing rapid lifestyle transition represent invaluable natural experiments for studying these mechanisms. These groups experience extreme gradients of environmental change—from traditional, subsistence-based lifestyles to fully market-integrated, urbanized living—within compressed timeframes and often within shared genetic backgrounds [34] [4]. This creates a quasi-experimental setting where researchers can compare individuals falling on opposite extremes of the "matched" to "mismatched" spectrum, thereby increasing statistical power to detect GxE interactions that would be obscured in more environmentally homogeneous populations [4]. Research partnerships with these communities are thus uniquely positioned to reveal how specific facets of lifestyle transition (e.g., diet, built environment, physical activity) interact with human biology to shape health outcomes.

Key Research Findings from Transitioning Populations

Cardiometabolic Health and the Built Environment

Comparative studies of transitioning Indigenous populations reveal surprising patterns about the drivers of cardiometabolic disease. Research with the Turkana pastoralists of northwest Kenya (n=3,692) and Orang Asli mixed subsistence groups of Peninsular Malaysia (n=688) demonstrated that cardiometabolic health was best predicted by measures quantifying urban infrastructure and market-derived material wealth rather than more proximate factors like diet or acculturation [34]. These results were highly consistent across both populations and sexes, suggesting a generalized phenomenon wherein the built environment serves as a proxy for the duration and intensity of market integration and impacts unmeasured proximate drivers like physical activity, stress, and broader access to market goods [34].

Factor analysis in these populations further revealed that lifestyle variation decomposes into two distinct axes—the built environment and diet—which change at different paces and exhibit different relationships with health [34]. This finding challenges simplistic models of lifestyle transition and underscores the need to disentangle these dimensions methodologically.

Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure Patterns

Quantitative data from subsistence-level populations reveals significantly different patterns of energy expenditure compared to industrialized populations. As shown in Table 1, despite lower average body weights, adults in subsistence-level societies maintain higher physical activity levels (PALs) and total daily energy expenditure than their counterparts in industrialized societies [35].

Table 1: Comparative Energy Expenditure in Subsistence-Level and Industrialized Populations

| Group | Sex | Average Weight (kg) | Average TDEE (kcal/day) | Average PAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrialized Populations | M | 77.5 | 2859 | 1.67 |

| F | 63.1 | 2146 | 1.63 | |

| Subsistence Populations | M | 57.2 | 2897 | 1.90 |

| F | 50.6 | 2227 | 1.78 |

Data compiled from [35]. TDEE = Total Daily Energy Expenditure; PAL = Physical Activity Level (TDEE/BMR).

Regression analyses indicate that at the same body weight, adults in industrialized societies have daily energy needs that are 600 to 1000 kilocalories lower than those of people living in subsistence-level societies [35]. This divergence in energy expenditure patterns represents a crucial physiological pathway through which lifestyle transitions may impact NCD risk.

Cognitive and Behavioral Adaptations

Subsistence transitions also shape fundamental cognitive processes. Experimental research with the Nyangatom, a single-ethnic group in Ethiopia whose members practice pastoralism, horticulture, or wage labor, revealed striking differences in social learning strategies [36]. Highly interdependent pastoralists based 80% of their decisions on social information, while more independent horticulturalists relied predominantly on individual payoffs (36% social information use) [36]. Urban dwellers fell between these extremes (62% social information use) [36]. These findings suggest that everyday socioeconomic practices can mold cognitive strategies, with potential implications for how communities adapt to novel environmental challenges.

Methodological Framework and Experimental Protocols

Core Methodological Principles

Research with subsistence-level populations requires specialized methodological approaches that respect both scientific rigor and community context:

- Verbal Administration: Minimize literacy-dependent tasks by verbally administering all study components, including consent forms and questionnaires, to all participants regardless of literacy level [37].

- Longitudinal Engagement: Build research programs with a long-term perspective, similar to ethnographic research, to establish trust and facilitate more complex experimental designs over time [37].

- Contextualized Measurement: Develop lifestyle scales that capture population-specific transition dimensions while maintaining cross-population comparability through factor-analytic approaches [34].

Integrated Data Collection Protocol

The most successful research programs implement comprehensive, integrated data collection spanning multiple domains, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Core Data Collection Domains for Lifestyle Transition Research

| Domain | Specific Measures | Collection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic Phenotypes | Waist circumference, body fat %, BMI, blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL/LDL, triglycerides, glucose [34] | Physical examination, blood collection via point-of-care analyzers |

| Lifestyle & Environment | Urban infrastructure, market integration, dietary patterns, material wealth, acculturation [34] | Structured surveys, direct observation, geographic mapping |

| Socioeconomic Factors | Social networks, subsistence interdependence, educational access, occupational history [36] | Ethnographic interviews, social network mapping, resource tracking |

| Genetic Material | DNA for genomic analyses of GxE interactions [4] | Saliva or blood samples with appropriate consent protocols |

Research Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for conducting genomic studies of evolutionary mismatch in transitioning populations:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions