Evolutionary Arms Race: Strategic Approaches to Outmaneuver Pesticide Resistance

This article synthesizes contemporary research and emerging strategies for managing pesticide resistance through an evolutionary lens.

Evolutionary Arms Race: Strategic Approaches to Outmaneuver Pesticide Resistance

Abstract

This article synthesizes contemporary research and emerging strategies for managing pesticide resistance through an evolutionary lens. It explores the foundational understanding of resistance as a complex, socio-ecological 'wicked problem' that demands transdisciplinary solutions. We examine cutting-edge methodological tools, from computational models and transgenic technologies to social science frameworks, that are being applied to anticipate and counteract resistance evolution. The content further addresses the critical challenges in optimizing these strategies and validates new approaches through experimental and field-based evidence. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive roadmap for developing more durable and sustainable pest management systems in agriculture and public health.

Decoding the Evolutionary Engine: Why Pesticide Resistance is a Wicked Problem

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is pesticide resistance often considered inevitable in field populations? Resistance is considered inevitable due to the strong and continuous selection pressure exerted by pesticides. When a pesticide is applied, it creates an environment where susceptible individuals die, while those with any inherent genetic resistance survive and reproduce. Field populations are typically large and genetically diverse, providing a vast pool of genetic variation upon which selection can act. This allows for rapid selection of resistant individuals, often through multiple genetic pathways, making the emergence of resistance a highly probable outcome of intensive pesticide use [1] [2].

FAQ 2: What is the difference between laboratory-selected and field-evolved resistance, and why does it matter for management? The genetic basis of resistance observed in laboratory-selected strains often does not reflect what occurs in field populations. Laboratory selection typically uses smaller populations and constant selection pressure, which may favor the accumulation of multiple mutations with small effects. In contrast, field populations are larger and more heterogeneous, frequently leading to resistance through major-effect alleles that arise from standing genetic variation or recurrent de novo mutations. Relying solely on laboratory models can therefore lead to an incomplete understanding of resistance and ineffective management strategies [1] [2].

FAQ 3: How rapidly can high-level resistance emerge and spread in field populations? Documented cases show that high-level resistance can emerge and become widespread in as little as three to four years after a pesticide's introduction. For example, resistance to the acaricide cyetpyrafen in two-spotted spider mites and to the insecticide chlorantraniliprole in the striped rice stem borer in China evolved from susceptibility to high-level, field-failure resistance within this short timeframe [3] [1] [2].

FAQ 4: What are the primary genetic mechanisms driving the rapid evolution of resistance? Resistance can evolve through two primary genetic mechanisms:

- Standing Genetic Variation: Pre-existing, rare resistance alleles in a population before pesticide application.

- De Novo Mutations: New mutations that arise after the selection pressure is applied. Recent studies highlight the role of an unprecedented number of recurrent mutations, where the same resistance-conferring mutation appears independently in different geographic populations. This parallel evolution significantly increases the speed and likelihood of resistance becoming widespread [1] [2].

FAQ 5: What are the key social and ecological challenges to managing resistance at a landscape level? Pesticide resistance is a common pool resource problem; susceptibility is a shared resource depleted by individual actions. Key management challenges include:

- Lack of Coordinated Action: Individual farmers' decisions impact entire regions, but landscape-scale coordination is difficult to achieve.

- Low Social Capital: Community-based management often struggles with weak social networks, lack of trust, and a sense of isolation or fatalism among stakeholders.

- Adoption of Integrated Pest Management (IPM): Adoption of IPM remains minimal and often reactive, rather than proactive [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Research Challenges

Challenge 1: Discrepancy between laboratory resistance studies and field observations.

- Problem: Resistance mechanisms identified in controlled lab experiments do not match those found in field-resistant populations.

- Solution:

- Implement Experimental Evolution: Use laboratory selection experiments with large, genetically diverse populations to better mimic field conditions [1] [2].

- Conduct Longitudinal Field Monitoring: Regularly collect field populations for phenotypic (bioassay) and genotypic (genomic sequencing) analysis to track resistance in real-time [3] [1].

- Utilize Historical Specimens: Compare modern resistant populations with preserved, historical specimens (when available) to determine if resistance alleles were pre-existing or arose de novo [1] [2].

Challenge 2: Difficulty in predicting resistance evolution for new pesticide chemistries.

- Problem: It is challenging to forecast how quickly resistance will evolve and which genetic mechanisms will be used.

- Solution:

- Develop Predictive Models: Combine in silico population genetics models with in vivo validation. The use of model organisms like C. elegans provides a scalable system for testing predictions due to its short generation time and ease of genetic manipulation [5].

- Screen for Mutational Options: Identify all possible target-site mutations that can confer resistance through functional genomics. Understanding the full spectrum of potential changes helps anticipate field evolution [1] [2].

Challenge 3: Failure to engage farming communities in collective resistance management.

- Problem: Community-based management programs fail to launch or lose momentum despite initial interest.

- Solution:

- Build Entrepreneurial Social Infrastructure: Focus on developing three key components:

- Legitimization of Alternatives: Community networks that support and validate new management approaches.

- Resource Mobilization: Ability to gather necessary materials, funding, and expertise.

- Broad-Based Networks: Diverse, inclusive stakeholder groups that extend beyond a single leader [4].

- Strengthen Social Capital: Foster trust, shared norms, and robust communication networks among farmers, researchers, extension agents, and industry stakeholders [4].

- Build Entrepreneurial Social Infrastructure: Focus on developing three key components:

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standardized Bioassay for Resistance Phenotype Monitoring

This protocol is used to quantify the level of resistance in a collected field population [3].

- 1. Sample Collection: Collect target pest organisms from multiple field locations. Ensure samples are representative and properly preserved for transport to the laboratory.

- 2. Preparation of Test Subjects: Use a uniform life stage (e.g., third-instar larvae) to reduce variability.

- 3. Dose Response Setup: Prepare a series of pesticide concentrations. A common method is the seedling dip method: rice stems or leaves are dipped in pesticide solutions and then exposed to the pest [3].

- 4. Exposure and Incubation: Expose the test subjects to the treated medium and hold under controlled environmental conditions for a specified period (e.g., 24-72 hours).

- 5. Data Recording and Analysis: Record mortality counts. Use probit analysis to calculate the Lethal Dose 50 (LD50) or Lethal Concentration 50 (LC50)—the dose or concentration that kills 50% of the test population [3].

- 6. Resistance Factor (RF) Calculation: Calculate the Resistance Factor by dividing the LD50 of the field population by the LD50 of a known susceptible reference strain.

RF = LD50(field population) / LD50(susceptible strain)[3].

Protocol 2: Genomic Monitoring for Resistance Genotypes

This protocol identifies the specific genetic mutations responsible for resistance [1] [2].

- 1. DNA/RNA Extraction: Extract high-quality genetic material from resistant and susceptible individuals.

- 2. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) or Target-Gene Sequencing: Sequence the entire genome or focus on candidate genes (e.g., the pesticide target protein). For cytochrome P450s or other metabolic resistance genes, RNA-Seq can be used to identify overexpression.

- 3. Genome Scan and Association Analysis: Compare genomes of resistant and susceptible phenotypes to identify genetic variants (SNPs, indels) strongly associated with the resistance trait.

- 4. Functional Validation: Use techniques like CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce the candidate mutation into a susceptible background or express the mutant gene in a heterologous system to confirm it confers resistance.

Protocol 3: Experimental Evolution in a Model System (C. elegans)

This protocol uses the nematode C. elegans as a model to study resistance evolution dynamics in a controlled, scalable laboratory setting [5].

- 1. Strain Preparation: Start with a genetically diverse population or a mixture of susceptible and known resistant strains.

- 2. Compound Selection: Choose a pesticide with a well-defined mode of action.

- 3. Selection Regime: Expose large populations of C. elegans to sub-lethal concentrations of the pesticide over multiple generations. Include control populations reared without pesticide.

- 4. Fitness and Phenotyping: Periodically assess the populations for changes in resistance levels (via bioassays) and life-history traits (fecundity, development time) to measure potential fitness costs.

- 5. Genetic Analysis: Sequence individuals or pools from evolved populations to identify selected alleles and pathways.

- 6. Model Comparison: Compare the experimental results with predictions from in silico population genetics models to validate and refine the models [5].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Resistance Evolution

Table 1: Documented Cases of Rapid Pesticide Resistance Evolution in Field Populations

| Pest Species | Pesticide | Time to Widespread High Resistance | Key Genetic Mechanism(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae) | Cyetpyrafen | ~3 years | 15 recurrent mutations across 8 residues of the target sdhB/sdhD genes; primarily de novo or from very rare standing variation [1] [2]. | [1] [2] |

| Striped rice stem borer (Chilo suppressalis) | Chlorantraniliprole | Rapid evolution post-2008 registration | Multiple major target-site mutations in the ryanodine receptor; parallel evolution across lepidopteran pests [3]. | [3] |

Table 2: Comparison of Laboratory vs. Field-Evolved Resistance Profiles

| Factor | Laboratory-Selected Resistance | Field-Evolved Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Population Size | Small, limited diversity [1] [2] | Large, high genetic diversity [1] [2] |

| Common Genetic Basis | Often polygenic (multiple small-effect loci) or a limited set of large-effect alleles [1] [2] | Often monogenic, driven by major-effect alleles from a wide array of recurrent mutations [1] [2] |

| Selection Pressure | Constant, predictable [1] | Heterogeneous, influenced by farmer practices, weather, and landscape [4] |

| Primary Utility | Identifying potential mechanisms, fitness cost assessment [5] | Understanding real-world evolutionary dynamics, informing management strategies [3] [1] |

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

Selection Pressure to Control Failure

Resistance Monitoring Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pesticide Resistance Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Insecticide | Used in bioassays to establish baseline susceptibility and calculate Resistance Factors (RF). | High-purity analytical standards of the pesticide under study (e.g., chlorantraniliprole, cyetpyrafen) [3] [1]. |

| Susceptible Strain | A genetically uniform strain with no known resistance alleles, serving as a control in experiments. | Lab-reared reference strain (e.g., C. elegans N2 wild-type for model studies; susceptible pest strains) [5]. |

| Bioassay Kits | Standardized materials for conducting dose-response mortality tests. | Materials for seedling dip, topical application, or diet incorporation assays [3]. |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | High-quality nucleic acid isolation for downstream genomic and transcriptomic analyses. | Kits suitable for the specific pest organism (e.g., for small arthropods like spider mites). |

| Whole Genome Sequencing Kit | For comprehensive genome-wide identification of resistance mutations and polymorphisms. | Library prep kits for short-read (Illumina) or long-read (PacBio, Nanopore) sequencing [1] [2]. |

| qPCR Reagents | To quantify gene expression levels of potential detoxification genes (e.g., P450s). | SYBR Green or TaqMan probes, primers for target and housekeeping genes. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | For functional validation of candidate resistance mutations by genome editing. | Cas9 protein/gRNA, homology-directed repair template for introducing specific SNPs [1]. |

| LC-MS/MS System | To quantify pesticide residues and metabolites in plant or insect tissues. | Systems like the SCIEX Triple Quad 6500+ for high-sensitivity quantification [6]. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is a transdisciplinary approach necessary for managing pesticide resistance?

Pesticide resistance is a "wicked problem," characterized by complex interplays between social, economic, and bio-ecological factors that resist simple solutions [7]. A focus solely on biological models ignores crucial elements such as farmer decision-making, economic pressures, social norms, and regulatory environments. Effective management requires integrating insights from social sciences (like psychology, sociology, and economics) with biophysical research to develop context-specific solutions [7].

FAQ 2: Our lab studies resistance evolution, but our insect populations are difficult to maintain at a large scale. Are there suitable model organisms?

Yes. Pest insect species are often unsuitable for large-scale laboratory evolution due to long generation times and difficulties in maintaining large populations. The nematode C. elegans presents a viable model organism for such studies [5]. It has a short 3-4 day lifecycle, can be cultured in large populations (tens of thousands), and is highly amenable to genetic manipulation. Importantly, it has sufficient biological homology to insects to provide pharmacologically relevant insights, with resistance mechanisms identified in C. elegans later being observed in field pest populations [5].

FAQ 3: What does a "knowledge deficit" approach mean, and why is it insufficient?

The "knowledge deficit" approach is the assumption that farmers develop resistance problems primarily because they lack knowledge of best practices, and that providing this information through brochures or field days will solve the issue [7]. However, this is often insufficient, as many farmers are already aware of resistance issues. The gap between knowledge and action is influenced by a wider set of factors, including economic constraints, social networks, values, and societal trends [7]. Effective interventions must address these broader contexts.

FAQ 4: How can I make complex research diagrams, like flowcharts of resistance evolution, accessible to colleagues with visual impairments?

For complex flowcharts, relying solely on the visual element is not accessible. The recommended practice is to provide both the visual and a text-based version [8].

- For the visual: Create a single, high-quality image of the entire flowchart with sufficient color contrast. Provide a concise alt-text that summarizes the chart's overall purpose and relationship, much like you would describe it over the phone [8].

- Text Version: Publish a text version using nested lists or a heading structure to communicate the same logical flow and relationships [8]. For example, use an ordered list with "If X, then go to Y" language for branching decision points [8].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Research Challenges

Problem 1: Rapid Evolution of High Resistance in Controlled Selection Experiments

- Symptoms: A rapid, exponential increase in resistance allele frequency and phenotypic resistance is observed over few generations in laboratory populations, mirroring field reports of swift control failure [3].

- Investigation & Root Cause: This is often driven by strong selection pressure from a single compound, leading to the fixation of major target-site mutations. Prior field data on diamide insecticides showed resistance factors (RF) could escalate from susceptible (RF=1) to high-level (RF > 1000) within 5-8 years of product registration, primarily due to the spread of specific ryanodine receptor mutations [3].

- Resolution Protocol:

- Implement Rotations: Switch between insecticides with different, unrelated modes of action (e.g., Group 28 and Group 5) after a set number of generations to reduce selection for a single resistance mechanism [5].

- Use Mixtures: Where feasible, use a balanced mixture of insecticides with different targets from the start of the experiment, making it harder for a single resistance mechanism to confer survival [5].

- Monitor Genotypes: Do not rely on phenotype alone. Use genotyping (e.g., PCR) to track the frequency of known major resistance alleles in your population throughout the experiment [3].

Problem 2: Inability to Predict Resistance Evolution from Theoretical Models

- Symptoms: Discrepancies exist between in-silico population genetics model predictions and empirical results from laboratory or field observations.

- Investigation & Root Cause: Theoretical models often incorporate simplified assumptions that may not capture the full complexity of real-world systems, including pleiotropic costs of resistance, population structure, and the presence of multiple resistance mechanisms.

- Resolution Protocol:

- Adopt an Integrated Framework: Develop a proof-of-concept model that integrates in-silico modelling with in-vivo experimental validation. C. elegans is a suitable organism for this due to its scalability and well-characterized genetics [5].

- Parameterize with Real Data: Feed your models with empirical data on resistance allele fitness costs, dominance, and initial frequency derived from laboratory experiments [5].

- Iterate and Validate: Use the laboratory evolution experiments to test the predictions of your theoretical model, then refine the model based on the experimental outcomes to improve its predictive power [5].

Problem 3: Failure to Translate Lab Findings to Field Management Recommendations

- Symptoms: A management strategy that is highly effective in controlled laboratory settings fails to deliver expected results in agricultural fields.

- Investigation & Root Cause: The laboratory environment does not replicate the social and economic constraints faced by farmers, such as cost pressures, equipment availability, and advice from peer networks [7].

- Resolution Protocol:

- Conduct Social Science Research: Engage with social scientists to conduct surveys, interviews, or focus groups with farmers and agricultural advisors to understand the barriers to adopting recommended practices [7].

- Co-Develop Strategies: Involve end-users (farmers, advisors) early in the research process to jointly frame the problem and develop management strategies that are not only biologically sound but also practically feasible and economically viable [7].

- Leverage Social Networks: Identify and work with influential actors within farming communities to disseminate information and promote the adoption of resistance management practices, as people are more likely to accept advice from those they trust [7].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Resistance Monitoring Protocol

This protocol outlines the standardized bioassay method for estimating the dose response curve and calculating the Resistance Factor (RF) in field-sampled pest populations [3].

- Method: Seedling dip bioassay. Rice stems are dipped in a range of pesticide doses before being exposed to the pest larvae [3].

- Key Measurement: Lethal Dose 50 (LD50) - the dose required to kill 50% of the test population.

- Calculation: Resistance Factor (RF) = LD50 of field population / LD50 of susceptible reference strain

- Baseline: A baseline LD50 must be established from a known susceptible population prior to insecticide deployment. For Chilo suppressalis and chlorantraniliprole, a reference baseline LD50 is 1.333 mg/larva [3].

Exemplar Quantitative Data: Diamide Resistance inChilo suppressalis

The table below collates data from resistance monitoring studies in China, demonstrating the rapid evolution of resistance to the diamide insecticide chlorantraniliprole [3].

| Year(s) Sampled | Location in China | Resistance Factor (RF) | Key Genetic Mechanism(s) Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 (Baseline) | Multiple | 1 (Susceptible) | None (pre-registration baseline) [3] |

| 2010-2012 | Various counties | 5 - 50 (Low to Moderate) | Initial detection of target-site mutations (e.g., G4946E) [3] |

| 2013-2015 | Central & Eastern China | 100 - 500 (High) | Spread of multiple ryanodine receptor mutations (e.g., I4790M, Y4667D) [3] |

| 2016-2018 | Widespread | > 1000 (Very High) | Fixation and combination of major mutations, leading to control failure [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Resistance Research |

|---|---|

| C. elegans Strains | Model organism for large-scale, rapid experimental evolution studies due to short lifecycle and ease of culturing [5]. |

| Ryanodine Receptor Modulators (e.g., Diamides) | Insecticides used to apply selection pressure in experiments; key for studying target-site resistance mechanisms in Group 28 [3]. |

| PCR & Genotyping Assays | Essential for identifying and tracking the frequency of known resistance-conferring alleles (e.g., G4946E, I4790M) in population samples [3]. |

| Standardized Bioassay Kits | Used for phenotypic resistance monitoring through dose-response curves, allowing for calculation of LD50 and Resistance Factors (RF) [3]. |

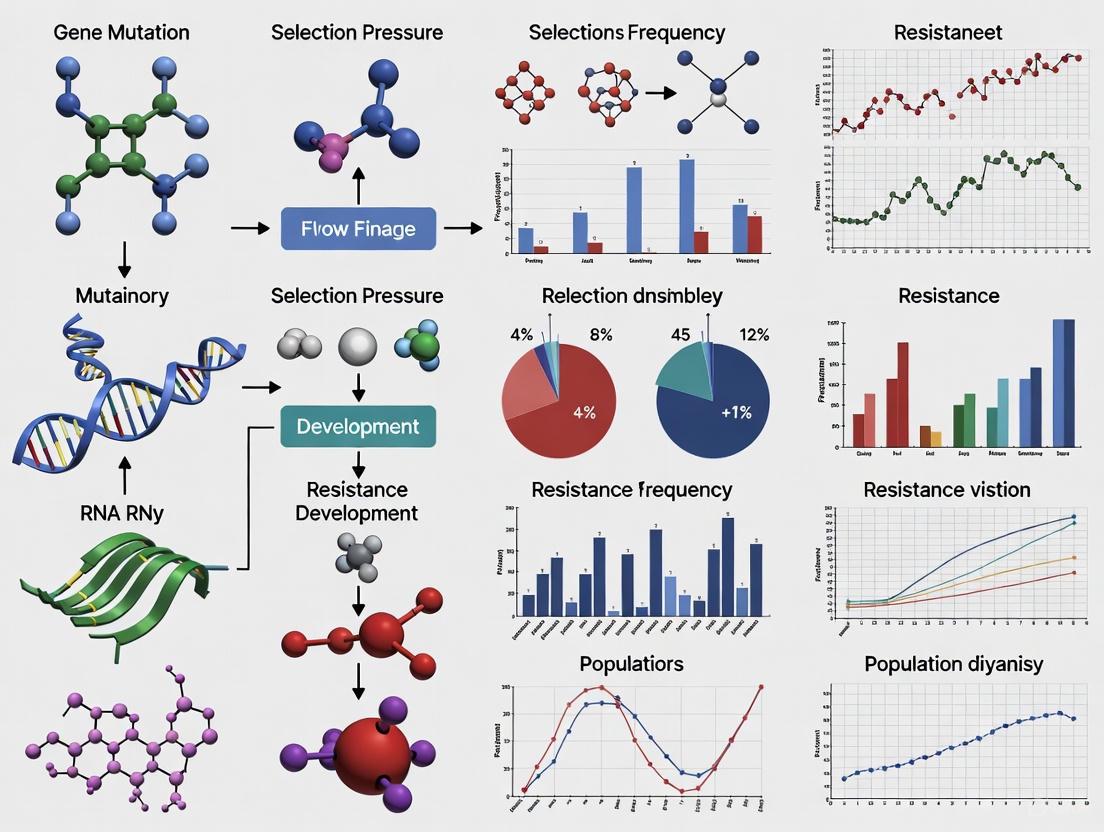

Research Visualization

Diagram 1: Transdisciplinary Research Workflow

Diagram 2: Resistance Monitoring Protocol

Resistance to chemical controls, whether in agricultural pests or microbial pathogens, represents a compelling example of rapid evolution in action. Understanding the diverse mechanisms underlying this resistance is crucial for developing sustainable management strategies. This technical resource center provides researchers and scientists with experimental protocols, troubleshooting guides, and key resources for investigating the genetic, physiological, and behavioral mechanisms that drive resistance evolution.

Core Resistance Mechanisms: A Framework for Investigation

Resistance mechanisms can be broadly categorized into several types, each with distinct genetic and phenotypic manifestations. The table below summarizes the primary mechanisms and their characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanisms of Resistance

| Mechanism Type | Genetic Basis | Key Functional Change | Example Pests/Pathogens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target-Site Mutation | Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes encoding target proteins [9] | Altered target site reduces binding efficiency of the pesticide/drug [9] | Rice stem-borer (Chilo suppressalis) resistance to diamides [3] |

| Metabolic Resistance | Overexpression or mutation of detoxification enzymes (e.g., P450 monooxygenases) | Enhanced degradation or sequestration of the toxic compound [9] | Pathogens resistant to benomyl fungicide [10] |

| Behavioral Resistance | Heritable changes in sensory or neural systems [11] | Avoidance behavior upon contact with sub-lethal doses of insecticide [12] | German cockroach and house fly aversion [12] |

| Reduced Permeability | Mutations in transport systems or cell envelope structures [9] | Decreased uptake or increased efflux of the toxic compound [9] | Bacterial resistance to aminoglycosides [9] |

Essential Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments in resistance research.

Protocol 1: Monitoring Phenotypic Resistance in Insect Populations

This standardized bioassay is used to estimate dose-response curves and calculate resistance factors (RF) in field-sampled populations [3].

Key Materials:

- Insect rearing facilities

- Pure active ingredient of the insecticide

- Solvent and control solution

- Rice seedlings or other host plants

- Precision applicator (e.g., micro-syringe)

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect target pest insects (e.g., Chilo suppressalis larvae) from multiple field locations.

- Dose Preparation: Prepare a dilution series of the insecticide, typically 5-7 concentrations.

- Bioassay: Use the seedling dip method. Dip rice stems in the insecticide solutions for 10 seconds and allow to dry [3].

- Exposure: Place individual larvae on the treated seedlings. For each concentration, use at least 30 insects to ensure statistical power.

- Data Collection: Record mortality after 24, 48, and 72 hours. Correct for control group mortality using Abbott's formula if necessary.

- Data Analysis: Use probit analysis to calculate the lethal dose (LD₅₀) or lethal concentration (LC₅₀) for the population [3]. The Resistance Factor (RF) is calculated as: RF = LD₅₀ (field population) / LD₅₀ (susceptible reference strain).

Protocol 2: Investigating Ryanodine Receptor Target-Site Mutations

Diamide insecticides target the ryanodine receptor (RyR) in insect muscles. This protocol details how to identify mutations associated with resistance [3].

Key Materials:

- DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents (primers, polymerase, dNTPs)

- Gel electrophoresis equipment

- Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing facilities

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from resistant and susceptible insect strains.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers to amplify the region of the RyR gene known to harbor resistance mutations (e.g., the transmembrane domain). Perform PCR to amplify the target fragment.

- Sequencing: Purify PCR products and submit for Sanger sequencing.

- Variant Analysis: Align DNA sequences from resistant and susceptible insects. Identify non-synonymous SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) that result in amino acid changes (e.g., G4946E, I4790M in C. suppressalis) [3].

- Validation: Use site-directed mutagenesis and functional assays in heterologous expression systems (e.g., cell lines) to confirm that the identified mutation confers resistance.

Protocol 3: Experimental Evolution with a C. elegans Model System

The nematode C. elegans serves as a scalable model for studying resistance evolution in the laboratory [5].

Key Materials:

- Wild-type and mutant C. elegans strains (e.g., resistant alleles available from the C. elegans Genetics Center)

- Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) plates

- Chemical compounds for selection (e.g., insecticides)

- Bleach solution (for synchronization)

Methodology:

- Strain Preparation: Start with a genetically diverse population or a mixture of susceptible and resistant strains.

- Experimental Design: Establish multiple replicate lines. Apply different selection regimes (e.g., constant dose, rotating insecticides, or mixtures) [5] [13].

- Selection Passages: Culture populations on NGM plates containing a selective concentration of the pesticide. The concentration should be high enough to exert selection pressure but allow some resistant individuals to survive.

- Population Maintenance: Every 3-4 days (one generation), synchronize populations using the bleaching technique to collect eggs for the next passage [5].

- Phenotyping: Periodically (e.g., every 10 generations), assess resistance levels in each line using dose-response bioassays.

- Genotyping: Sequence pooled populations or individual worms at different time points to track allele frequency changes at resistance loci.

Diagram 1: C. elegans Experimental Evolution Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Researchers

Q: Our bioassay results show high variability in mortality between replicates. What could be the cause? A: High variability often stems from inconsistent insect age, size, or physiological state. Standardize your insect colony by using individuals of the same developmental stage (e.g., early 3rd instar larvae) and ensure uniform rearing conditions. Also, verify the accuracy of your serial dilutions and the even application of the pesticide to the test substrate [3].

Q: We have identified a genetic mutation in a suspected target gene. How can we definitively prove it confers resistance? A: Genetic association alone is not proof of causation. A robust validation requires:

- Correlation: The mutation must be consistently present in resistant phenotypes and absent (or rare) in susceptible ones across multiple populations.

- Functional Expression: Introduce the mutation into a susceptible model organism (e.g., via CRISPR/Cas9) and demonstrate a significant increase in the resistance phenotype [5].

- Biochemical Assay: Show altered binding of the pesticide to the mutated target protein in vitro [9].

Q: How can we distinguish true behavioral resistance from simple repellency or learned aversion? A: True behavioral resistance must be a heritable trait. Design a multi-generation selection experiment:

- Continuously expose a population to a sub-lethal dose of the insecticide that allows for a behavioral response (e.g., in a choice-test arena).

- Select and breed only those individuals that exhibit the avoidance behavior.

- If the propensity to avoid the insecticide increases over generations in the selected line compared to an unselected control line, this provides evidence for a heritable, behavioral resistance mechanism [11].

Q: What is the most effective strategy for deploying multiple pesticides to delay resistance: mixtures or rotations? A: Theoretical models and simulations often favor the mixture strategy when there is no cross-resistance. The mixture strategy ensures that individuals resistant to one toxin are killed by the other, making the inheritance of double resistance functionally recessive [13]. However, rotation can be superior under specific conditions, such as when insecticide efficacy is very high, dominance of resistance is low, and there is significant premating dispersal between treated and untreated areas [13]. The optimal choice depends on the pest's life history, the insecticides' properties, and the landscape context.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Resources for Resistance Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Susceptible Strains | Baseline for calculating Resistance Factors (RF) in bioassays. | Comparing LD₅₀ values of field populations to a lab-maintained susceptible strain [3]. |

| C. elegans Wild-type (N2) & Mutant Strains | Model organism for experimental evolution and genetic studies of resistance. | Studying the dynamics of known resistance alleles under different selection regimes [5]. |

| Ryanodine Receptor (RyR) Primers | PCR amplification of target-site regions for sequencing. | Identifying G4946E mutation in diamide-resistant lepidopteran pests [3]. |

| Cell-based NF-κB Reporter Assay | Functional validation of pathway activation in disease models. | Confirming that mutations in TNFRSF17 (BCMA) constitutively activate NF-κB signaling in multiple myeloma [14]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Kit | Accurate amplification of DNA fragments for sequencing and cloning. | Minimizing errors during amplification of resistance gene candidates prior to sequencing. |

Visualizing Key Resistance Pathways

Understanding the molecular targets of pesticides and drugs is fundamental. The following diagram illustrates the mechanism of diamide insecticides and a common resistance mutation.

Diagram 2: Diamide Insecticide Target and Resistance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: Our bioassays show a sudden, dramatic loss of cyetpyrafen efficacy in field-collected spider mite populations. What is the most likely genetic mechanism?

A: The failure is likely due to target-site mutations in the genes encoding succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), particularly the SdhB and SdhD subunits. Unlike resistance driven by a single mutation, your population may possess one of at least 15 different identified amino acid substitutions across these subunits. An unprecedented case documented five different substitutions at a single residue [15] [1]. This high number of mutational options means resistance can emerge from multiple independent genetic events rather than the spread of one pre-existing mutation.

Q2: How can I confirm if metabolic resistance mechanisms (like GSTs) are involved in my resistant strain?

A: You can perform the following investigative steps:

- Synergism Bioassays: Pre-treat mites with a synergist like diethyl maleate (DEM), which inhibits Glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity. If the mites subsequently show significantly increased susceptibility to cyetpyrafen in bioassays, it indicates GSTs are likely involved in detoxification [16].

- Enzyme Activity Assay: Directly measure GST enzyme activity in resistant and susceptible strains. A statistically significant elevation in activity in the resistant strain provides strong evidence for this mechanism [16].

- Gene Expression Analysis: Use qPCR to quantify the expression levels of GST genes. Significant overexpression in the resistant strain, especially across multiple life stages (eggs, nymphs, adults), points to a metabolic resistance role [16].

Q3: Our lab-selected resistant strain shows a different genetic basis for resistance compared to field-evolved strains. Why is this, and which is more relevant?

A: This discrepancy is common and expected. Field populations are larger and more genetically diverse, allowing the selection of multiple rare, large-effect mutations. In contrast, lab selection in smaller populations often favors the accumulation of multiple small-effect changes or a limited set of large-effect alleles not representative of the field [17] [1]. For designing real-world resistance management strategies, data from field-evolved resistance is more relevant, as it captures the true spectrum of genetic options available to the pest.

Q4: We detected a known resistance mutation, but it is absent in our historical collections. What does this imply?

A: This strongly suggests the mutation arose de novo (as a new substitution) after the introduction of cyetpyrafen selection pressure, or from an extremely rare pre-existing mutation that was undetectable in your screening method. This finding rules out the standing genetic variation as the primary source and highlights the capacity for rapid, recurrent evolution in response to strong selection [15] [1].

Q5: How can we improve the application of cyetpyrafen in the field to delay resistance and enhance efficacy?

A: Optimizing application technology is key. Research shows:

- Increase Spray Volume: Increasing the spray volume from 900 L/ha to 1050 L/ha significantly improved the control of T. urticae on strawberries, ensuring better coverage [18].

- Use Ozone Spray Technology: Field trials demonstrated that ozone spray applications resulted in significantly higher control effects on T. urticae*1 and 3 days after treatment compared to conventional and electrostatic sprays [18].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent research on cyetpyrafen resistance.

Table 1: Laboratory Toxicity of Various Acaricides Against Tetranychus urticae [18]

| Acaricide | Mode of Action Group | LC50 for Adults (mg/L) | LC50 for Eggs (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyetpyrafen | METI II | 0.226 | 0.082 |

| Cyenopyrafen | METI II | 0.240 | 0.097 |

| Cyflumetofen | METI II | 0.415 | 0.931 |

| Bifenazate | METI III | 3.583 | 18.56 |

| Abamectin | Avermectin | 5.531 | 25.52 |

| Etoxazole | Inhibitor of chitin synthesis | 267.7 | 0.040 |

Table 2: Characteristics of a Laboratory-Selected Cyetpyrafen-Resistant Strain [19]

| Property | Finding in Cyet-R Strain |

|---|---|

| Resistance Level | > 2,000-fold |

| Cross-Resistance | Cyenopyrafen (>2,500-fold), Cyflumetofen (~190-fold) |

| Mode of Inheritance | Autosomal, Incomplete Dominance |

| Number of Genes | Polygenic (Multigenic) |

| Fitness Cost | Fitness advantage observed (shorter development time, increased fecundity) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Monitoring Resistance Evolution in Field Populations

Objective: To track the emergence and spread of cyetpyrafen resistance in Tetranychus urticae field populations over time and space [15] [17] [1].

Materials:

- Field-collected mite populations from multiple geographical regions

- Susceptible reference mite strain

- Technical grade cyetpyrafen

- Solvent (e.g., acetone) and surfactant (e.g., Tween-80)

- Leaf discs (e.g., bean, strawberry)

- Potter spray tower or similar precise application equipment

- Controlled environment chambers (25±1°C, 60% RH, 16:8 L:D)

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Systematically collect mite samples from a wide geographic area before the introduction of a new acaricide (if possible) and for several years after its commercial release.

- Bioassay: Use a standardized leaf-disc spray method. Serially dilute cyetpyrafen in a solvent-water-surfactant solution.

- Application: Use a Potter spray tower to apply a precise volume (e.g., 1.5 mg/cm²) of each dilution onto leaf discs. Include solvent-only treatments as controls.

- Exposure: Transfer adult female mites onto the treated leaf discs. Maintain in controlled environment chambers.

- Assessment: Record mortality after a set period (e.g., 24 or 48 hours). Mites are considered dead if they show no movement after gentle probing.

- Data Analysis: Use probit analysis to calculate the median lethal concentration (LC50) for each population and time point. Plot the geographical and temporal spread of resistance.

Protocol 2: Identification of Target-Site Mutations via Population Genomics

Objective: To identify and characterize mutations in the target-site genes (sdhB, sdhC, sdhD) associated with resistance [15] [1].

Materials:

- Resistant and susceptible mite populations (fresh or preserved)

- DNA/RNA extraction kits

- PCR thermocycler and reagents

- Next-generation sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina)

- Bioinformatics software for genome assembly and variant calling

Methodology:

- DNA/RNA Sequencing: Perform whole-genome or transcriptome sequencing on pooled or individual mites from resistant and susceptible populations.

- Variant Calling: Map sequencing reads to a reference genome (e.g., Tetranychus urticae) and call genetic variants (SNPs, indels).

- Selective Sweep Scan: Perform genome-wide scans for signatures of selective sweeps (e.g., reduced nucleotide diversity, skewed allele frequency spectra) in resistant populations compared to susceptible ones.

- Candidate Gene Analysis: Focus analysis on genes in the significantly differentiated genomic regions, particularly the known target genes (sdhB, sdhC, sdhD).

- Validation: Validate candidate mutations using Sanger sequencing or targeted amplicon sequencing in additional resistant and historical samples to confirm the association and determine if mutations are de novo or from standing variation.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cyetpyrafen Resistance Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Grade Cyetpyrafen | Standard for bioassays and selection experiments | Ensure high purity for accurate LC50 determination. |

| Synergists (e.g., DEM, PBO) | To identify metabolic resistance mechanisms | DEM inhibits GSTs; PBO inhibits P450s [16]. |

| Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDH) Enzyme Assay Kit | Functional validation of target-site mutations | Measures enzyme activity to confirm if mutations impair inhibitor binding. |

| cDNA Synthesis & qPCR Kits | Gene expression analysis of detoxification genes | Quantify overexpression of genes like PcGSTO1 [16]. |

| PCR Reagents & Sanger Sequencing | Genotyping and validation of target-site mutations | Confirm the presence of specific sdhB and sdhD mutations. |

| Strawberry or Bean Plants | Host plants for mite rearing and bioassays | Ensure use of a consistent, susceptible plant variety. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Cyetpyrafen Resistance Mechanisms

Resistance Research Workflow

The Modern Resistance Management Toolkit: From Computational Models to Field Applications

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary genetic sources of pesticide resistance, and how do they influence computational modeling? Resistance can originate from de novo mutations (new mutations appearing after pesticide application) or be selected from standing genetic variation (pre-existing polymorphisms in the population) [20]. The source significantly impacts forecasting: resistance from standing variation typically emerges faster and is more repeatable across populations, while de novo mutation can lead to more unpredictable, unique genetic solutions [20]. Models must account for these origins to accurately project resistance evolution and inform anti-resistance strategies like pesticide rotation.

FAQ 2: How can dynamic programming principles be applied to manage pesticide resistance? Dynamic optimization problems, where the training data or environment changes over time, are a key application area [21]. In resistance management, this translates to treating successive pest generations as a changing dataset. Open-ended evolutionary algorithms, like the Age-Layered Population Structure (ALPS), can run continuously, adapting management strategies by leveraging past population data instead of restarting from scratch each season, thus mimicking dynamic programming for more efficient long-term planning [21].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between single-step and multi-step pesticide resistance?

- Single-step resistance arises suddenly from a single genetic change, causing a rapid population shift from susceptible to resistant after just one or two pesticide applications. Examples include resistance to streptomycin and benomyl [10].

- Multi-step resistance develops gradually over many years through the accumulation of multiple genes, each conferring a small increase in tolerance. The population shows a continuous range of sensitivity, with control eroding slowly, as seen with sterol inhibitor (SI) fungicides [10].

FAQ 4: Why are population genetics models vital for forecasting resistance? The gene pool of a pest population naturally contains variation [10]. Pesticide application applies strong artificial selection, increasing the frequency of resistant individuals in each generation [10]. Population genetics models simulate this process of selection on genetic variation, allowing researchers to forecast the rate of resistance development under different management scenarios, such as varying application frequencies or using mixtures of pesticides [20] [10].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Model Failure to Predict Rapid Resistance Emergence

Problem: Your computational model consistently underestimates the speed at which resistance develops in a pest population.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect resistance origin assumption | Review genetic data from pre-treatment and early-resistance populations for evidence of multiple resistant alleles, suggesting standing variation [20]. | Recalibrate the model to account for selection from standing genetic variation rather than waiting for de novo mutations. |

| Overlooking pleiotropic co-option | Investigate if pre-existing adaptations (e.g., for detoxifying plant compounds) are being co-opted for pesticide resistance [20]. | Include known detoxification pathways and efflux systems as potential pre-adaptations in the model's genotype-to-phenotype map. |

| Insufficient selection pressure | Audit the simulation's fitness function to ensure it accurately reflects the high mortality rate imposed by the pesticide. | Adjust fitness penalties to ensure a strong selective advantage for resistant genotypes. |

Issue 2: Inaccurate Parameter Estimation in Genetic Algorithms

Problem: The genetic algorithm (GA) for optimizing symbolic regression models fails to converge on meaningful parameters or becomes trapped in poor solutions.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Premature convergence | Monitor population diversity metrics (e.g., unique variable frequencies). A rapid drop indicates a lack of genetic diversity [21]. | Increase the mutation rate to reintroduce variation [21] or implement an Age-Layered Population Structure (ALPS) to automatically reseed the population with new individuals. |

| Ineffective fitness function | Test if the fitness function (e.g., mean squared error) is sufficiently sensitive to small, meaningful improvements in the model. | Incorporate multi-objective optimization that balances model accuracy with complexity (parsimony pressure) to avoid overfitting. |

| Poor initial population | Analyze the distribution of initial solutions. A narrow distribution may start the search in a non-optimal region. | Use techniques like ramped half-and-half for generating a diverse initial population of symbolic models. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Modeling Resistance Evolution Using Population Genetics and Dynamic Programming

Objective: To simulate the evolution of pesticide resistance in a pest population under different management strategies and forecast resistance emergence.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Environment: A programming environment suitable for evolutionary algorithms (e.g., Python with DEAP or R).

- Initial Genetic Parameters: Data on initial allele frequencies for resistance genes, if available from field monitoring.

- Fitness Functions: Defined selection coefficients representing the fitness advantage of resistant vs. susceptible genotypes under pesticide application.

Methodology:

- Population Initialization:

- Define a population of

Nindividuals, each with a genotype representing one or more loci involved in resistance. - Set the initial frequency of resistance alleles based on empirical data or a low default value (e.g., 0.001) for de novo scenarios, or a higher, polymorphic frequency for standing variation scenarios [20].

- Define a population of

Selection Cycle (One Generation):

- Apply Selection: Expose the virtual population to a "pesticide application." Calculate the fitness of each genotype based on its resistance profile and the pesticide's efficacy. Resistant individuals have a higher probability of survival and reproduction.

- Reproduction: Selected individuals reproduce to form the next generation. Use a mating algorithm that includes recombination (crossover) and mutation. A standard mutation rate (e.g., 10^-5 to 10^-6 per locus per generation) is often sufficient, but monitor for diversity loss [21].

Dynamic Management Intervention (Decision Point):

- At defined intervals (e.g., every 5 generations), execute the dynamic programming logic. Based on the current state of the population (e.g., resistance allele frequency), choose an action from the set

{Apply Pesticide A, Apply Pesticide B, Apply Mixture, No Spray}. - The choice is made to maximize a long-term reward, such as maintaining control for the maximum number of generations or minimizing total pesticide use.

- At defined intervals (e.g., every 5 generations), execute the dynamic programming logic. Based on the current state of the population (e.g., resistance allele frequency), choose an action from the set

Data Recording and Iteration:

- Track key metrics each generation: resistance allele frequency, population size, and management action taken.

- Repeat steps 2-4 for hundreds or thousands of generations to project long-term resistance dynamics.

Validation:

- Compare model outputs, such as the predicted time to resistance failure, against historical field data if available.

Protocol 2: Ensemble Genetic Programming for Forecasting Resistance Spread

Objective: To improve the accuracy of predicting future resistance levels by combining multiple optimization models into a single, robust forecast.

Materials and Reagents:

- Historical Data: Time-series data on resistance prevalence, pesticide use history, and environmental factors.

- Base Models: Implementations of a Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Simulated Annealing (SA) [22].

Methodology:

- First-Stage Forecasting:

- Use the historical data to train multiple base models (e.g., GA, PSO, SA) to find the parameters of regression models (e.g., linear, quadratic) that best fit the observed resistance trends [22].

- Each model produces a preliminary forecast of future resistance levels.

Ensemble Integration via Genetic Programming (GP):

- Use the forecasts from the best-performing first-stage models (e.g., GAQuadratic, PSOQuadratic) as input variables for a second-stage GP [22].

- The GP evolves symbolic expressions (mathematical formulas) that non-linearly combine the initial forecasts to produce a final, refined prediction.

Validation and Projection:

- Validate the ensemble model's performance on a held-out portion of historical data using metrics like Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) [22].

- Use the validated model to project future resistance levels under different pesticide usage scenarios.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Optimizes parameters for symbolic regression models that describe resistance dynamics [21] [22]. | Population-based, uses selection, crossover, and mutation; prone to premature convergence without high mutation or diversity mechanisms [21]. |

| Age-Layered Population Structure (ALPS) | An open-ended evolutionary algorithm for dynamic environments that prevents population stagnation [21]. | Uses age layers to reseed populations, making it less sensitive to mutation rates and effective for continuous adaptation [21]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | An alternative optimization method for model calibration, inspired by social behavior [22]. | Often effective for quadratic models; can be used as a base learner in ensemble forecasting methods [22]. |

| Standing Genetic Variation | The pre-existing polymorphisms in a population that serve as the raw material for rapid resistance evolution [20]. | Leads to faster, more repeatable resistance compared to de novo mutation; critical for accurate risk assessment. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Genetic Programming for Dynamic Symbolic Regression

Population Genetics of Resistance

FAQs: Gene Drive Mechanisms and Design

1. What is a gene drive and how does it differ from traditional Mendelian inheritance? A gene drive is a self-propagating genetic mechanism that biases its own inheritance, allowing it to spread through a population faster than traditional Mendelian inheritance. In standard Mendelian inheritance, an allele has a 50% chance of being passed to offspring. Gene drives "rig" this competition, enabling desired genetic variants to spread rapidly, even if they confer disadvantageous traits to the organism [23].

2. What are the main types of gene drives? There are two primary categories: natural and synthetic gene drives. Natural gene drives (like transposable elements or Homing Endonuclease Genes) occur in nature. Synthetic gene drives are engineered in the lab to achieve specific outcomes. Furthermore, engineered drives are often classified by their intended effect: suppression drives aim to reduce population size, while modification/replacement drives aim to alter a population's traits [23] [24].

3. How does CRISPR-Cas9 improve gene drive technology? CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized gene drive development by providing a precise, easy-to-use, and efficient genome-editing tool. Its key advantages over previous technologies (like ZFNs and TALENs) include higher precision, lower off-target editing, a wider range of genomic targets, and greater ease of engineering, which has accelerated research and expanded potential applications [23] [25].

4. What is a "self-eliminating" or "self-limiting" gene drive? A self-limiting gene drive is designed to spread a genetic modification and then disappear from the population. For example, the "e-Drive" (self-eliminating allelic drive) system is programmed to convert insecticide-resistant genes back to their natural, susceptible form. Because the drive cassette imposes a fitness cost (e.g., reduced male mating success), it is rapidly eliminated from the population after its task is complete, offering a controlled, temporary intervention [26].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Low Inheritance Bias (Homing Efficiency)

Problem: The gene drive is not spreading through the target population at the expected super-Mendelian rate.

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Inefficient gRNA design: The guide RNA has low cleavage efficiency or off-target effects. | Re-design gRNA to ensure optimal sequence specificity and efficiency; use validated bioinformatics tools for design and in vitro validation. |

| "Leaky" expression: Cas9 is expressed at low levels or in the wrong tissue. | Utilize a stronger or more specific germline promoter (e.g., the vasa2 promoter) to ensure robust Cas9 expression in the germline [25] [27]. |

| Resistance alleles: The formation of mutations at the cut site that block further cleavage. | Target highly conserved, essential genomic regions to reduce the likelihood of functional resistance alleles; use multiple gRNAs [25]. |

Challenge 2: Formation of Resistance Alleles

Problem: Cutting the target chromosome leads to mutations that block the drive, rather than the desired copying via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR).

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Dominance of NHEJ repair: The cell repairs the Cas9-induced break via error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining. | Favor HDR by optimizing the timing of Cas9 expression to coincide with the cell cycle stage when HDR is most active [25]. |

| Inefficient repair template: The homologous DNA template is not available or accessible. | Ensure the homologous "donor" template is present on the drive allele and is of sufficient length; optimize the design of the HDR cassette [23] [25]. |

| Unviable target site: The target gene can tolerate disruptive mutations. | Target a haplo-sufficient gene where disruptive mutations are non-viable or confer a severe fitness cost, thus preventing their spread [25]. |

Challenge 3: Unintended Fitness Costs and Somatic Effects

Problem: The gene drive construct reduces the organism's viability or fertility, hindering its ability to spread.

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Somatic Cas9 activity: Cas9 expression in non-germline tissues causes damaging cuts. | Use a germline-specific promoter to restrict Cas9 expression. Note that some somatic "leakiness" can be harnessed for specific effects, as in the MDFS system [27]. |

| Insertional mutagenesis: The drive insertion disrupts the function of the target gene or a nearby gene. | Carefully characterize the insertion site and the phenotype of homozygous and heterozygous individuals to assess any disruptive effects [25]. |

| Energetic cost of expression: The metabolic burden of expressing Cas9 and gRNAs. | Investigate the use of naturally occurring, "minimized" Cas9 variants that impose a lower fitness burden on the host [25]. |

Challenge 4: Confinement and Safety in Laboratory Studies

Problem: Ensuring the gene drive is safely studied in the lab without unintended environmental release.

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Potential for escape: Accidental release of gene drive organisms from the lab. | Implement strict physical containment (e.g., double-door entry, filtered ventilation) and ecological confinement (e.g., studying non-local species) [24]. |

| Lack of molecular confinement: The drive is fully functional and could spread if released. | Develop and use "split-drive" systems where the Cas9 and gRNA components are separated. The drive only functions when both are present, enhancing control [25]. |

| Insufficient oversight: Inadequate review of experimental plans. | Follow a phased pathway from laboratory research to potential release, with continuous risk assessment and oversight at each stage [24]. |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Laboratory Testing of a Suppression Drive

This protocol outlines the testing of a suppression drive, such as one targeting the doublesex gene for female sterility in mosquitoes [27].

Workflow:

- Stable Line Generation: Microinject the gene drive construct (e.g., Cas9 under a germline promoter + dsx-targeting gRNA) into embryos of the target species to create stable transgenic lines.

- Crossing Scheme: Cross heterozygous gene drive males with wild-type females.

- Inheritance Rate Calculation: Genotype the offspring to determine the transmission rate of the drive allele. A rate significantly above 50% indicates successful homing.

- Phenotypic Screening: Screen for the expected phenotypic outcome (e.g., intersexuality and sterility in homozygous dsx mutant females).

- Population Cage Trials: Introduce a defined number of gene drive-bearing individuals into caged wild-type populations. Monitor the population size and drive allele frequency over multiple generations to assess suppression efficacy [27].

Protocol 2: Testing a Self-Eliminating Drive (e-Drive)

This protocol is for testing a drive designed to reverse insecticide resistance and then disappear, as demonstrated in fruit flies [26].

Workflow:

- Construct Design: Engineer a drive cassette that targets a mutant, insecticide-resistant allele (e.g., in the vgsc gene) and replaces it with the wild-type, susceptible version. Include a fitness cost mechanism (e.g., on the X-chromosome to reduce male fertility).

- Initial Cross: Cross e-Drive males with resistant females.

- Frequency Monitoring: Track the frequency of the e-Drive cassette and the wild-type allele in the population over each generation.

- Observe Decline: Confirm that the e-Drive cassette frequency peaks and then declines as the population is converted back to insecticide susceptibility.

- Verification: After the cassette disappears, verify that the population is homozygous for the restored wild-type gene and susceptible to the insecticide [26].

Table 1: Efficacy of Selected Gene Drive Systems in Laboratory Studies

| Gene Drive System | Target Species | Target Gene / Trait | Key Efficacy Metric | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Homing Suppression Drive | Anopheles gambiae | doublesex (female sterility) | Population elimination in cages after a single 12.5% release of transgenic males [27]. | Nature Comm. 2025 |

| Self-Eliminating e-Drive | Drosophila melanogaster | vgsc (insecticide resistance reversal) | 100% of offspring converted to wild-type allele in 8-10 generations [26]. | Nature Comm. 2022 |

| Male-Drive Female-Sterile (MDFS) | Anopheles gambiae | doublesex (dominant female sterility) | Population elimination in cages after repeated releases; super-Mendelian inheritance [27]. | Nature Comm. 2025 |

Table 2: Common Molecular Reagents for Gene Drive Construction

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates a double-strand break in the DNA at a location specified by the guide RNA. The "scissors" for genome editing. | Core component of all CRISPR-based homing gene drives [23] [25]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | A short RNA sequence that directs the Cas9 protein to a specific genomic target site. | Determines the specificity of the gene drive; designed to target essential genes [23]. |

| Germline-Specific Promoter | A DNA sequence that drives the expression of Cas9 specifically in the germline cells. | Restricts drive activity to the gametes, reducing somatic effects (e.g., vasa2 promoter) [25] [27]. |

| Homology Arms | DNA sequences flanking the drive construct that are identical to the target site; facilitate Homology-Directed Repair. | Enables the copying of the drive allele into the wild-type chromosome [23] [25]. |

| Fluorescent Marker (e.g., eCFP) | A visual reporter gene used to easily identify transgenic individuals under a microscope. | Screening for successful integration and inheritance of the drive construct [27]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our field monitoring shows resistance to a new pesticide evolved much faster than our models predicted. What could be the cause?

A: Rapid resistance evolution is often driven by the recurrent emergence of multiple, independent target-site mutations in field populations [1]. This is different from the slow spread of a single pre-existing mutation.

- Diagnosis Checklist:

- Sequence the target gene: Check for multiple amino acid substitutions at the target site, especially at different residue positions. The presence of several distinct mutations indicates recurrent de novo evolution [1].

- Analyze genetic backgrounds: If identical mutations appear on different genetic backgrounds, it confirms independent evolutionary events rather than the spread of one resistant lineage [1].

- Review usage history: Intensive, repetitive use of a single mode of action creates strong homogenous selection that favors these rapid adaptations [28] [3].

Q2: We implemented a pesticide mixture strategy, but now observe cross-resistance to unrelated chemistries. Why did this happen?

A: This is a potential trade-off where mixtures select for generalist resistance mechanisms instead of specialist ones [29]. Your strategy may have successfully reduced selection for specific target-site mutations (specialist resistance) but inadvertently favored non-target-site resistance (NTSR) mechanisms [29].

- Diagnosis Checklist:

- Measure generalist resistance biomarkers: Quantify the expression levels of detoxification enzymes, such as glutathione-S-transferases (e.g., AmGSTF1 in blackgrass). An increase is indicative of an enhanced metabolic NTSR mechanism [29].

- Conduct dose-response assays: Test population survival against pesticides with different modes of action. Simultaneous resistance to multiple, unrelated classes strongly suggests a generalist NTSR mechanism is at play [29].

- Audit pesticide history: Compare fields with and without a history of mixture use. Epidemiological data can show a correlation between mixture intensity and the level of NTSR [29].

Q3: Our laboratory selection experiments are not replicating the resistance patterns seen in the field. What is a major limitation of our experimental system?

A: A key limitation is the small effective population size (Ne) and low genetic diversity of typical laboratory populations. This restricts the available mutational options for resistance to evolve compared to large, heterogeneous field populations [5] [1].

- Diagnosis Checklist:

- Compare resistance alleles: Identify the resistance mutations in your field samples. If these alleles are absent from your lab-selected strains, your starting lab population lacked the necessary genetic diversity [1].

- Evaluate population size: Laboratory populations often number in the hundreds or low thousands, which severely limits the pool of rare, large-effect mutations available for selection. Field populations are orders of magnitude larger [5] [1].

- Consider a model system: If working with large insect populations is infeasible, explore surrogate organisms like C. elegans that can be cultured in large numbers (tens of thousands) for evolutionary experiments, provided their pharmacology is relevant to your research [5].

Q4: We are designing a resistance management strategy. Should we prioritize mixtures or rotations?

A: The optimal choice is highly system-specific and there is no universal best strategy [28]. The success depends on underlying resistance genetics and the mechanisms present in your pest population.

- Diagnosis & Strategy Selection Table:

| Strategy | Best Suited For | Key Prerequisites for Success | Major Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixtures | Systems where resistance alleles are rare and fully recessive [28]. | Co-formulation is possible; both components remain highly effective; redundant killing is achieved [28]. | Selects for generalist NTSR mechanisms [29]. Can rapidly select for double-resistant genotypes if resistance is not recessive [28]. |

| Rotations | Situations where using a single mode of action for a defined period is feasible. | Resistance alleles to each insecticide have associated fitness costs that reduce their frequency when the selective pressure is removed [28]. | Requires strict discipline and monitoring. Less effective if resistance alleles have no fitness cost or if NTSR is present [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Monitoring Quantitative Resistance Phenotypes in Field Populations [3]

- Objective: To estimate the resistance factor (RF) in a field-collected pest population.

- Materials: Field-collected pest specimens, susceptible reference strain, pesticide of interest, bioassay equipment (e.g., vials, pots), solvent.

- Methodology:

- Standardized Bioassay: Expose the test population to a series of doses of the pesticide using a standard method like the seedling dip assay for stem-borers or leaf dip for other pests [3].

- Dose-Response Curve: Record mortality at each dose after a set exposure period. Use probit analysis to calculate the lethal dose that kills 50% of the population (LD~50~) [3].

- Resistance Factor (RF) Calculation: Calculate the RF by dividing the LD~50~ of the field population by the LD~50~ of a susceptible reference strain (baseline measurement) [3].

- Key Formula:

RF = LD50 (field population) / LD50 (susceptible baseline)

Protocol 2: An Experimental-Theoretical Framework for Predicting Resistance Evolution [5]

- Objective: To validate in silico models of resistance evolution with laboratory selection experiments.

- Materials: C. elegans strains (including strains with known resistance-conferring alleles), pesticides with defined modes of action, NGM plates, bleach solution for synchronization, population genetics modelling software.

- Methodology:

- In Silico Modelling: Develop a population genetics model simulating the selection of known resistance alleles in a population with defined starting frequency, fitness costs, and selection pressure [5].

- Laboratory Selection: Expose large, replicate populations of C. elegans to the pesticide over multiple discrete generations (achieved through bleaching synchronization). Maintain a known selection pressure [5].

- Phenotypic Monitoring: Periodically sample populations and use bioassays to measure the change in resistance over generations [5].

- Genotypic Validation: Sequence target genes from sampled populations to track allele frequency changes [5].

- Model Validation: Compare the experimentally observed resistance dynamics (both phenotypic and genotypic) to the predictions of the in silico model [5].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Dynamics of Chlorantraniliprole Resistance in Chilo suppressalis in China [3]

| Year | Sample Location (County) | Resistance Factor (RF) | Primary Resistance Mechanism Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-2008 | Various (Baseline) | 1.0 (by definition) | Susceptible |

| ~2010 | Multiple | 5 - 50 | Emerging target-site mutations |

| ~2015 | Widespread | 100 - >1000 | Multiple, prevalent target-site mutations (e.g., in ryanodine receptor) |

Table 2: Epidemiological Link Between Herbicide Mixtures and Resistance Mechanism Selection in Blackgrass [29]

| Historical Herbicide Use Pattern | Impact on Specialist Target-Site Resistance (TSR) | Impact on Generalist Non-Target-Site Resistance (NTSR) | Net Effect on Phenotypic Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low mixture use / Single MOA | Increased frequency | No significant change or decrease | Increased resistance, primarily driven by TSR |

| High mixture use | Decreased frequency | Increased level (e.g., higher AmGSTF1) | Variable; trade-off between reduced TSR and increased NTSR |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Resistance Evolution Pathways

Diagram 2: Experimental-Theoretical Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Resistance Evolution Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Susceptible Reference Strain | Provides a baseline LD~50~ for calculating Resistance Factors (RF) in bioassays [3]. | Used in all phenotypic resistance monitoring. |

| Strains with Known Resistance Alleles | Enable the study of specific resistance mechanisms and their dynamics during selection [5]. | Tracking allele frequency in experimental evolution; testing cross-resistance patterns. |

| Model Organism (C. elegans) | A scalable surrogate system for studying resistance evolution with discrete generations and genetic tools [5]. | Proof-of-concept experimental-theoretical studies on resistance management strategies [5]. |

| Biomarker for NTSR (e.g., AmGSTF1) | A protein whose concentration serves as a quantitative indicator of a generalist metabolic resistance mechanism [29]. | Epidemiological studies linking management practices (e.g., mixtures) to NTSR selection [29]. |

| Population Genetics Model | A computational framework to simulate and predict the changes in resistance allele frequencies under different management strategies [5]. | In silico testing of rotation vs. mixture strategies before costly field implementation [28] [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the relevance of social science and community engagement to pesticide resistance management? Pesticide resistance is an evolutionary process driven by selection pressure [3]. Area-wide management seeks to reduce this pressure across a landscape. Social science and community engagement are critical because resistance management is ultimately a human behavioral challenge; its success depends on the collective actions of multiple stakeholders, such as farmers adopting uniform pest control strategies. Behavioral theories provide frameworks for encouraging these necessary behavior changes [30] [31].

FAQ 2: How can a "small wins" approach help a long-term resistance management program? The "small wins" approach involves breaking down large, complex problems like area-wide resistance into smaller, more manageable components [31]. Successfully changing a specific, observable behavior (e.g., achieving farmer agreement on a restricted pesticide list in one small district) provides positive reinforcement. This documented success can build momentum, sustain engagement, and demonstrate the feasibility of the larger program to a broader audience [31].

FAQ 3: What does "resident control" mean in the context of community engagement, and why does it matter? Resident control refers to the level of decision-making power and active involvement that community members have in planning and implementing change activities, as opposed to simply participating in an externally led program [30]. Research shows that higher levels of resident control are associated with stronger development of social capital and collective behavioral action, which are key drivers for sustainable, community-led resistance management [30].

FAQ 4: My resistance monitoring shows a rapid increase in resistance alleles. Is this due to evolutionary selection or genetic drift? In large, stable populations, a rapid and consistent increase in the frequency of a specific resistance allele is a strong indicator of positive selection [3] [5]. Genetic drift typically causes random fluctuations in allele frequencies and has a more pronounced effect in small populations. To confirm selection, you should:

- Establish a Null Hypothesis: Frame the null hypothesis that the observed allele frequency change is due to chance alone (drift) [32].

- Use a Model System: Laboratory selection experiments with model organisms like C. elegans can be used to test if a specific pesticide application regime produces a similar rapid rise in resistance, helping to validate field observations [5].

- Statistical Testing: Compare the observed changes in allele frequency against what is expected under a null model of random genetic drift.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Lack of stakeholder adherence to a coordinated pesticide application schedule.

- Potential Cause: Low perceived benefits, high complexity, or insufficient social reinforcement for compliant behavior.

- Solution: Apply principles of Applied Behavior Analysis to shape and sustain the desired behavior [31].

- Simplify the Action (Shaping): Break down the protocol into smaller steps and reinforce completion of each step.

- Implement Positive Reinforcement: Establish a system of immediate, positive consequences for adherence. This could be social recognition, small financial incentives, or access to aggregated data showing the program's success.

- Use Stimulus Control: Provide clear, simple cues. This could include synchronized text message reminders before application dates or colored flags distributed to participating farms to signal participation.

Problem: Experimental evolution in the lab does not recapitulate field-observed resistance dynamics.

- Potential Cause: The laboratory population size may be too small, leading to strong genetic drift that overwhelms the signal of selection [5].

- Solution:

- Scale Up Population Size: Use a model organism like C. elegans, which allows for the maintenance of large population sizes (tens of thousands) to minimize the effects of drift and make selection the dominant evolutionary force [5].

- Validate with Modeling: Develop an in-silico population genetics model using your known parameters (population size, selection coefficient, initial allele frequency). If the laboratory results deviate significantly from the model's predictions, genetic drift is a likely cause, confirming the need for a larger experimental population [5].

Problem: Failure to detect a fitness cost associated with a resistance allele in a laboratory setting.

- Potential Cause: The environmental conditions in the lab may not expose the fitness cost, which might only be apparent under specific field-relevant stresses (e.g., resource limitation, competition, climate fluctuations).

- Solution:

- Refine the Null Hypothesis: The intrinsic null hypothesis is that resistance alleles are selectively neutral in the absence of the pesticide. Your alternative hypothesis is that they carry a cost [32].

- Diversify Assay Conditions: Measure fitness components (e.g., fecundity, development rate, competitive ability) under a wider range of environmental conditions that more closely mimic the field environment.

- Benchmark Against a Model: Compare your results to a mathematical model that explicitly includes a fitness cost. If your data consistently shows no deviation from the model without a cost, this strengthens the null hypothesis for your specific laboratory conditions [32].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Community-Engaged CPTED for Building Collective Efficacy

This protocol adapts Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) to build the social foundation necessary for area-wide management by engaging residents in physical improvements [30].

- Community Identification: Partner with a community organization to identify a neighborhood for the intervention.

- Baseline Assessment: Conduct interviews and surveys to measure baseline levels of sense of community, social cohesion, and collective efficacy [30].