Evolutionary Algorithms for Parameter Optimization: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of evolutionary algorithms (EAs) for parameter optimization, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Evolutionary Algorithms for Parameter Optimization: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of evolutionary algorithms (EAs) for parameter optimization, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers foundational principles, explores cutting-edge methodologies and their real-world applications in tackling complex biomedical problems, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance performance, and offers a rigorous validation framework for comparing EA variants. By synthesizing the latest research and case studies, this guide serves as a strategic resource for leveraging EAs to accelerate and improve outcomes in computational chemistry and clinical-stage drug discovery.

The Principles of Evolutionary Optimization: From Natural Selection to Algorithmic Problem-Solving

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) are a class of optimization techniques inspired by the principles of natural evolution and genetics, designed to solve complex problems where traditional optimization methods may be inadequate [1] [2]. These algorithms operate on a population of candidate solutions, applying iterative processes of selection, variation, and replacement to evolve increasingly optimal solutions over generations. The core mechanisms driving this process—selection, crossover, and mutation operators—work in concert to balance the exploration of new regions in the search space with the exploitation of known promising areas [3]. In parameter optimization research, particularly for drug development, EAs provide powerful tools for navigating high-dimensional, non-linear search spaces common in molecular design and biological modeling, enabling researchers to discover solutions that might otherwise remain elusive through deterministic methods alone [1] [4].

Core Operator Mechanisms

Selection Operators

Selection operators determine which individuals in a population are chosen as parents to produce offspring for the next generation, creating evolutionary pressure toward better solutions [3]. These operators work with fitness values or rankings rather than directly manipulating genetic representations, and their careful implementation is crucial for maintaining an appropriate balance between selecting the most promising individuals (exploitation) and preserving population diversity (exploration) [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Selection Operators

| Operator Type | Mechanism | Selection Pressure | Computational Efficiency | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tournament Selection | Randomly selects a subset of individuals (tournament size k) and chooses the fittest among them [2] [3]. | Adjustable via tournament size (larger k increases pressure) [3]. | High, especially for large populations [3]. | Problems requiring tunable selection pressure; large-scale optimization [3]. |

| Roulette Wheel Selection | Assigns selection probabilities proportional to individuals' fitness values [2] [3]. | Directly proportional to fitness differences; can be high with significant fitness variance [3]. | Moderate to low, particularly for large populations [3]. | Well-scaled fitness functions with moderate variance [3]. |

| Rank-Based Selection | Selects based on relative ranking rather than absolute fitness values [3]. | More consistent than fitness-proportional methods [3]. | Moderate (requires sorting population by fitness) [3]. | Problems with poorly-scaled fitness functions or significant fitness outliers [3]. |

| Elitism | Directly copies a small percentage of the fittest individuals to the next generation [3]. | Very high for selected individuals. | High. | Ensuring preservation of known good solutions; preventing performance regression [3]. |

The selection pressure exerted by these operators significantly impacts algorithm performance. Excessive pressure can lead to premature convergence, where the population stagnates at a local optimum, while insufficient pressure may result in slow convergence or random search behavior [3]. Tournament selection's popularity stems from its efficiency and tunable pressure, while roulette wheel selection maintains a closer relationship between fitness and selection probability but can be sensitive to extreme fitness values [3].

Crossover Operators

Crossover (or recombination) operators combine genetic information from two or more parent solutions to create one or more offspring, exploiting beneficial building blocks from existing solutions [1] [3]. These operators are typically applied with a specified probability (crossover rate), and the choice of operator depends heavily on the problem representation (binary, real-valued, permutation) [3].

Table 2: Crossover Operator Types and Characteristics

| Operator Type | Mechanism | Representation Compatibility | Building Block Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Point | Selects one random crossover point and swaps subsequent genetic material between parents [2] [3]. | Binary, Integer | Moderate |

| Multi-Point | Selects multiple crossover points and alternates genetic material segments between parents [3]. | Binary, Integer | Variable |

| Uniform | Each gene in the offspring is created by randomly copying the corresponding gene from either parent according to a mixing ratio [3]. | Binary, Real-valued, Integer | Low |

| Arithmetic | Creates offspring genes as a weighted average of corresponding parent genes [3]. | Real-valued | High |

| Order Crossover (OX) | Preserves relative order of genes by copying a segment from one parent and filling remaining positions in order from the other parent [3]. | Permutation | High for ordering |

| Partially Mapped Crossover (PMX) | Ensures offspring validity by swapping a segment between parents and mapping relationships to resolve duplicates [3]. | Permutation | High for adjacency |

In drug design applications, crossover enables the combination of promising molecular substructures or pharmacophoric patterns from different parent compounds, potentially generating novel molecules with enhanced biological activity or improved pharmacokinetic properties [4]. The crossover rate significantly influences evolutionary dynamics, with higher rates promoting greater exploration of solution combinations while potentially disrupting beneficial building blocks [3].

Mutation Operators

Mutation operators introduce random changes to individual solutions, serving as a primary mechanism for exploration and diversity maintenance in evolutionary algorithms [1] [3]. By periodically altering genetic material, mutation helps populations escape local optima and discover new regions of the search space that might not be reachable through crossover alone [3]. The application frequency of mutation is controlled by the mutation rate, while the magnitude of changes is determined by operator-specific parameters [3].

Table 3: Mutation Operator Classification by Representation Type

| Representation | Operator Type | Mechanism | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binary | Bit-Flip Mutation | Randomly inverts bits (0→1, 1→0) with probability equal to mutation rate [2] [3]. | Mutation rate |

| Real-Valued | Gaussian Mutation | Adds random noise drawn from a Gaussian distribution to gene values [2] [3]. | Mutation rate, Standard deviation |

| Uniform Mutation | Replaces gene values with random values uniformly selected from a specified range [3]. | Mutation rate, Value range | |

| Creep Mutation | Makes small incremental adjustments to gene values (increasing or decreasing) [3]. | Mutation rate, Step size | |

| Permutation | Swap Mutation | Randomly selects two positions and exchanges their values [3]. | Mutation rate |

| Inversion Mutation | Reverses the order of genes between two randomly selected positions [3]. | Mutation rate | |

| Scramble Mutation | Randomly reorders the values within a randomly selected subset [3]. | Mutation rate, Subset size |

In pharmaceutical applications, mutation operators enable the exploration of novel chemical space by introducing structural variations to molecular representations, such as modifying functional groups, altering ring structures, or changing side chain properties [4]. Adaptive mutation schemes, which dynamically adjust mutation rates based on population diversity or convergence metrics, can enhance optimization performance in complex drug design landscapes [3].

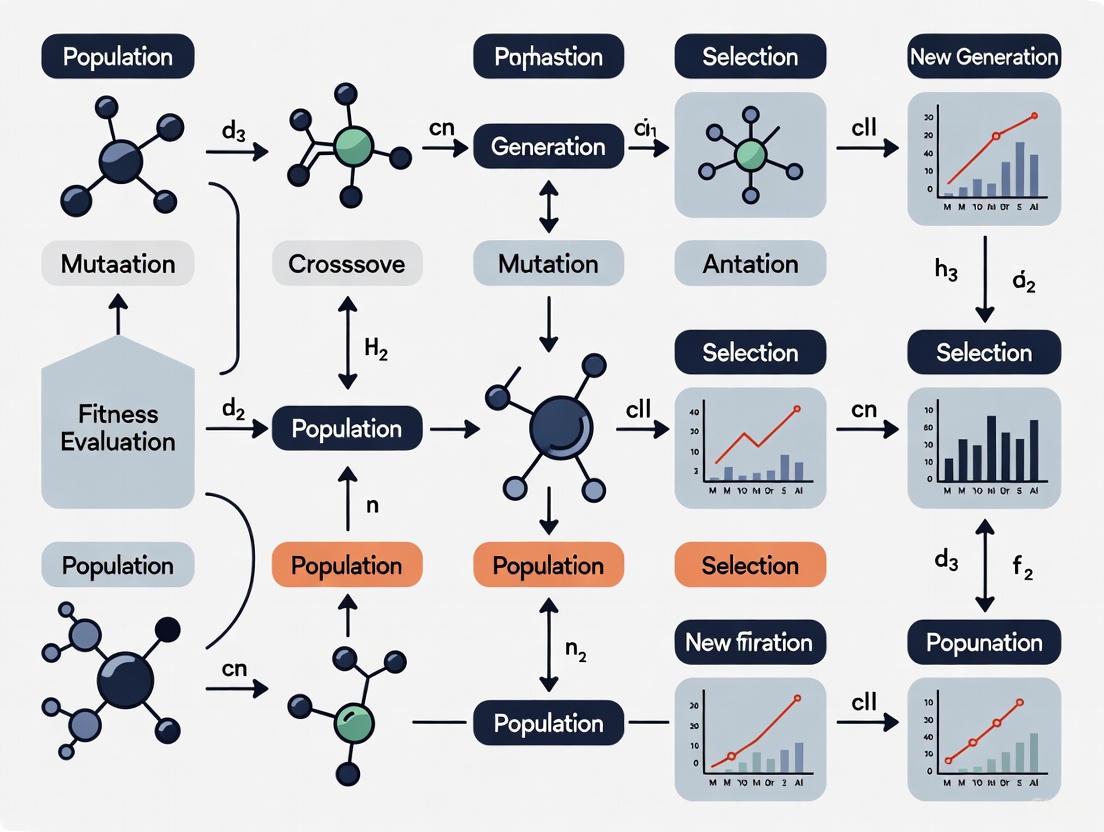

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow of an evolutionary algorithm, highlighting the integration and interaction between selection, crossover, and mutation operators within the complete optimization cycle:

Experimental Protocol for Drug Design Optimization

This protocol details the application of evolutionary algorithms for optimizing quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models in pharmaceutical research, specifically for predicting biological activity of compound libraries.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Compound Library | Diverse collection of molecular structures with associated biological activity data [4]. | Provides training and validation data for QSAR model development. |

| Molecular Descriptors | Quantitative representations of molecular properties (e.g., logP, molar refractivity, topological indices) [4]. | Serves as feature set for evolutionary algorithm optimization. |

| Evolutionary Algorithm Framework | Software implementation of EA operators (e.g., thefittest, DEAP) [5]. | Provides optimization engine for feature selection and model parameter tuning. |

| Fitness Function | Objective function measuring model performance (e.g., predictive accuracy, complexity) [1] [4]. | Guides evolutionary search toward optimal solutions. |

| Validation Dataset | Hold-out set of compounds not used during model training [4]. | Enables unbiased assessment of optimized model performance. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Problem Formulation and Representation

- Objective: Develop a QSAR model with maximum predictive accuracy for target biological activity

- Representation: Encode solution candidates as real-valued vectors representing feature subsets and model parameters [4] [5]

- Fitness Function: Define a composite fitness metric balancing model accuracy (R², classification rate) with complexity (number of features) [4]

Algorithm Initialization

- Set population size to 100-500 individuals based on problem complexity [5]

- Initialize population with random feature subsets and parameter values within predefined bounds [1] [2]

- Configure evolutionary operators: tournament selection (size=3), uniform crossover (rate=0.8), Gaussian mutation (rate=0.1, std=0.05) [3] [5]

Evolutionary Optimization Cycle

- Fitness Evaluation: For each individual, train a predictive model (e.g., partial least squares regression, random forest) using the selected feature subset and evaluate on validation data [4]

- Selection: Apply tournament selection to identify parents for recombination [3]

- Variation: Generate offspring through crossover and mutation operations [3]

- Replacement: Implement elitist replacement strategy, preserving top 5% of individuals unchanged between generations [3]

- Termination Check: Continue iterations until fitness plateaus (no improvement for 50 generations) or maximum generations (500-1000) reached [5]

Validation and Analysis

- Apply the best-evolved feature subset and model parameters to independent test set

- Analyze selected molecular descriptors for biochemical interpretability [4]

- Compare evolved model performance against baseline methods (e.g., full feature set, stepwise selection)

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Evolutionary algorithms have demonstrated significant utility across multiple domains in drug discovery and development, leveraging their core mechanisms to address complex optimization challenges.

Multi-Objective Compound Optimization

In lead optimization, researchers often face competing objectives such as maximizing potency while minimizing toxicity and synthetic complexity [6] [4]. Multi-criterion evolutionary optimization approaches enable the discovery of Pareto-optimal solutions representing different trade-offs between these objectives. The selection operator balances exploration across the Pareto front with convergence toward non-dominated solutions, while crossover and mutation operators facilitate the discovery of novel chemical structures satisfying multiple constraints [6].

Autonomous Protein Engineering

Recent advances integrate evolutionary algorithms with automated laboratory systems for programmable protein evolution [7]. In these platforms, selection operators implement growth-coupled selection pressure where protein functionality directly influences cellular fitness, crossover enables recombination of beneficial protein domains, and mutation introduces sequence diversity through error-prone replication [7]. These systems can operate autonomously for extended periods (e.g., one month), executing continuous evolutionary optimization of target proteins such as enzymes, biosensors, and therapeutic proteins [7].

Hybrid Quantum-Evolutionary Approaches

Emerging research explores the integration of quantum computing principles with evolutionary algorithms for enhanced optimization in pharmaceutical applications [8]. Quantum-inspired evolutionary algorithms leverage superposition and entanglement concepts to maintain more diverse populations, potentially improving exploration of complex molecular search spaces [8]. These hybrid approaches may offer computational advantages for specific problem classes in drug design, such as molecular docking simulations and protein folding predictions [8].

Performance Optimization Guidelines

Successful application of evolutionary algorithms for parameter optimization requires careful tuning of operator parameters and implementation strategies.

Operator Parameter Tuning

- Selection Pressure: Balance exploitation and exploration by adjusting tournament size or using adaptive selection methods that respond to population diversity metrics [3]

- Crossover Rate: Typically set between 0.7-0.9 to encourage sufficient mixing of genetic material without excessive disruption of building blocks [3]

- Mutation Rate: Employ lower rates (0.01-0.1) to maintain diversity without devolving into random search; consider adaptive schemes that increase mutation when diversity decreases [3]

- Elitism: Preserve 1-5% of top performers to ensure monotonic improvement while preventing premature convergence [3]

Problem-Specific Operator Selection

- Real-valued parameter optimization: Prefer blend crossover (BLX) or simulated binary crossover (SBX) with Gaussian or polynomial mutation [3] [5]

- Combinatorial problems: Employ order-based representations with order crossover (OX) or partially mapped crossover (PMX) and swap or inversion mutation [3]

- Feature selection: Use binary representations with uniform or multi-point crossover and bit-flip mutation [4]

Performance Enhancement Techniques

- Fitness Scaling: Implement linear or exponential scaling to maintain appropriate selection pressure throughout the evolutionary process [1]

- Constraint Handling: Apply penalty functions, repair mechanisms, or specialized operators to ensure solution feasibility in constrained optimization problems [4]

- Parallelization: Leverage population-based parallelism to evaluate multiple solutions simultaneously, significantly reducing computation time for fitness evaluation [5]

The core mechanisms of mutation, crossover, and selection operators provide a powerful foundation for addressing complex parameter optimization challenges in pharmaceutical research. By understanding the theoretical principles, practical implementation details, and domain-specific applications of these operators, researchers can effectively harness evolutionary algorithms to accelerate drug discovery and development efforts.

In the realm of parameter optimization research, evolutionary algorithms (EAs) are a class of population-based metaheuristics inspired by biological evolution and collective swarm intelligence [9]. The efficacy of these algorithms is profoundly dependent on the precise formulation of the optimization problem, which is encapsulated by its search space. Defining this space—through decision variables, constraints, and objective functions—is a critical first step that dictates the algorithm's ability to navigate the solution landscape efficiently. This is especially true in complex, real-world domains like drug development, where problems often involve high-dimensional, constrained, and multi-faceted objectives [10] [11]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for researchers and scientists to define these core components effectively within the context of evolutionary algorithms for parameter optimization.

Core Components of a Search Space

The search space in an optimization problem is defined by three fundamental components. The interplay between these components guides the evolutionary search process.

Decision Variables

Decision variables represent the adjustable parameters of the system to be optimized. The choice of variable type directly influences the algorithm's design and operator selection. Supported variable types in evolutionary computation frameworks are diverse [12] [13].

Table 1: Types of Decision Variables and Their Applications

| Variable Type | Description | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Real/Continuous | Real-valued parameters within bounds [12]. | Optimizing neural network weights, chemical compound concentrations [14]. |

| Integer | Discrete, integer-valued parameters [12]. | Determining the number of nodes in a network, generalized knapsack problems. |

| Binary | Variables restricted to 0 or 1 [12]. | Feature selection, standard knapsack problems. |

| Permutation | An ordered sequence of items [12]. | Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), scheduling tasks. |

| Selection | A fixed-length subset of items [12]. | Selecting a set of molecular descriptors or key features from a dataset. |

Constraints

Constraints define the feasible region of the search space by imposing conditions that solutions must satisfy. They represent real-world limitations. In EAs, constraints are often handled using penalty functions, where infeasible solutions have their fitness degraded by an amount proportional to the constraint violation [13]. For a solution vector x, constraints can be:

- Inequality constraints: ( g_j(x) \leq 0 ), for ( j = 1, 2, ..., J ) [10]

- Equality constraints: ( h_p(x) = 0 ), for ( p = 1, 2, ..., P ) [10]

- Bound constraints: ( xi^l \leq xi \leq x_i^u ), for ( i = 1, 2, ..., n ) [10]

Objective Function

The objective function (or fitness function) quantitatively evaluates the quality of any candidate solution. In a single-objective optimization problem, the goal is to find the solution that minimizes or maximizes this single function [10]. In a multi-objective optimization problem (MultiOOP), two or three conflicting objectives are optimized simultaneously [10]. A many-objective optimization problem (ManyOOP) involves more than three objectives, which is common in drug design where properties like potency, novelty, toxicity, and synthetic cost must be balanced [10] [11].

Workflow for Search Space Definition

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision process for defining the core components of a search space.

Application in Drug Discovery: Experimental Protocols

Drug discovery presents a canonical example of complex many-objective optimization. The following protocol details the application of an EA for a de novo drug design task.

Protocol: Setting up a Many-Objective Molecular Optimization

Objective: To identify novel molecular structures that simultaneously optimize multiple pharmacological properties.

Materials and Reagents:

- Molecular Datasets: Source from public repositories like DrugBank or Swiss-Prot [14].

- Property Prediction Tools: Software for calculating ADMET properties, molecular docking scores, quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), and synthetic accessibility score (SAS) [11].

- Computational Framework: A flexible evolutionary computation toolkit such as DEAP in Python [13] or YPEA in MATLAB [12].

Procedure:

- Variable Definition:

- Represent a molecule using a real-valued latent vector from a generative model (e.g., a Transformer autoencoder like ReLSO or FragNet) [11]. Alternatively, use a string representation (SMILES/SELFIES) or a graph-based representation.

- For a latent vector representation, the decision variables are the continuous values of the vector (e.g., 128 dimensions). Bounds are typically defined by the latent space distribution [11].

Objective Function Formulation:

- Define four or more objective functions to be optimized. The following table summarizes common objectives in drug design [10] [11].

- Table 2: Example Objectives for Many-Objective Drug Design

Objective Goal Typical Measure Potency/Efficacy Maximize Negative of binding affinity (docking score) from molecular docking [11]. Toxicity Minimize Predicted toxicity probability from an ADMET model [11]. Drug-Likeness Maximize Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED) score [11]. Synthetic Accessibility Maximize Negative of Synthetic Accessibility Score (SAS) [11]. Pharmacokinetics Optimize Predictions for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion (ADMET) [11].

Constraint Definition:

- Chemical Validity: Enforce via the molecular representation (e.g., using SELFIES) or by incorporating a validity check as a hard constraint [11].

- Structural Constraints: Impose limits on molecular weight (e.g., ≤ 500 g/mol) or the number of rotatable bonds.

- Potency Threshold: Define a minimum required binding affinity (e.g., docking score < -7.0 kcal/mol) as an inequality constraint.

Algorithm Execution:

- Select a many-objective evolutionary algorithm (e.g., MOEA/D, NSGA-III) [10] [11].

- Initialize a population of random latent vectors or molecules.

- In each generation (iteration): a. Decode latent vectors to molecules [11]. b. Evaluate each molecule by calculating all objective functions from Table 2. c. Apply penalty functions to molecules that violate defined constraints [13]. d. Select parent solutions based on their fitness and non-domination rank. e. Create offspring via crossover and mutation operators in the latent space [11].

- Repeat for a predetermined number of generations or until performance converges.

Output Analysis:

- The algorithm returns a Pareto front, a set of non-dominated solutions representing optimal trade-offs between the conflicting objectives [10].

- Analyze the chemical structures and property profiles of the molecules on the Pareto front for further investigation.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| DEAP Framework | A Python library for rapid prototyping of Evolutionary Algorithms, supporting various variable types and genetic operators [13]. | DEAP Documentation |

| YPEA Toolbox | A MATLAB toolbox for solving optimization problems using EAs and metaheuristics, with built-in support for real, integer, binary, and permutation variables [12]. | YPEA on Yarpiz |

| ADMET Prediction Models | AI models used to predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties of a molecule in silico [11]. | Integrated in frameworks like [11] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Computational tools to predict the binding orientation and affinity of a small molecule (ligand) to a protein target [11]. | Used for objective evaluation in [11] |

| Generative Latent Models | Transformer-based autoencoders (e.g., ReLSO, FragNet) that encode molecules into a continuous latent space for optimization [11]. | ReLSO model [11] |

The Strength of Population-Based Search in Rugged Landscapes

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) represent a class of powerful optimization techniques inspired by natural selection, playing an increasingly vital role in complex parameter optimization challenges across scientific domains, including computational biology and drug development. The performance and efficiency of EAs are critically dependent on appropriate population sizing, a parameter traditionally determined through empirical means rather than theoretical grounding [15]. Rugged fitness landscapes, characterized by numerous local optima and deceptive pathways, present particularly challenging environments for optimization algorithms. In such landscapes, the interplay between exploration (searching new regions) and exploitation (refining existing solutions) becomes paramount. Population-based search strategies offer distinct advantages in these contexts through their inherent parallelism and diversity maintenance mechanisms. This application note examines the theoretical foundations of population sizing in rugged landscapes, provides detailed experimental protocols for researchers, and presents a structured framework for evaluating population-based search performance in challenging optimization scenarios, with specific relevance to computational drug discovery.

Theoretical Framework: Population Sizing and Landscape Ruggedness

The theoretical justification for population-based approaches in rugged landscapes stems from two primary considerations: fitness landscape analysis and Probably Approximately Correct (PAC) learning theory. Research indicates that population sizing should be informed by fitness landscapes' ruggedness to ensure effective search performance [15]. Landscape ruggedness, quantitatively described by metrics such as fitness distance correlation and autocorrelation measures, directly influences the difficulty of optimization problems. Rugged landscapes with high epistasis (gene interactions) and numerous local optima require larger population sizes to maintain sufficient genetic diversity to avoid premature convergence.

The PAC learning framework provides theoretical bounds on population size required to achieve satisfactory solutions with high probability [15]. This approach formalizes the relationship between solution quality, computational resources, and problem difficulty, offering researchers principled estimates for population parameters rather than relying solely on empirical tuning. For rugged landscapes, the population must be sufficiently large to sample multiple promising regions simultaneously while withstanding deceptive fitness signals that might lead search algorithms toward local optima rather than global solutions.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Landscape Ruggedness

| Metric | Description | Interpretation in Rugged Landscapes | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fitness Distance Correlation | Measures correlation between fitness and distance to global optimum | Values near 0 indicate difficult, rugged landscapes; negative values suggest deceptive landscapes | Pearson correlation between fitness and distance to nearest global optimum |

| Autocorrelation Length | Measures how fitness changes with increasing distance in search space | Shorter length indicates more rugged landscape with frequent fitness changes | Random walk analysis with fitness evaluation at each step |

| Epistasis Index | Quantifies degree of gene interaction effects | Higher values indicate more complex gene interactions contributing to ruggedness | Analysis of variance in fitness contributions |

| Number of Local Optima | Count of locally optimal solutions | Higher counts directly indicate increased ruggedness | Adaptive search with basin identification |

Population-Based Search in Uncertain Environments

Recent advances in population-based search methodologies have addressed the critical challenge of optimization under uncertainty, particularly relevant to real-world scientific applications where measurement noise and parameter uncertainty are inherent. Traditional robust multi-objective optimization methods typically prioritize convergence while treating robustness as a secondary consideration, which can yield solutions that are not genuinely robust under noise-affected scenarios [16]. The innovative Uncertainty-related Pareto Front (UPF) framework represents a paradigm shift by balancing robustness and convergence as equal priorities during the optimization process [16].

This approach is particularly valuable for drug development applications where experimental conditions, binding affinities, and pharmacokinetic parameters exhibit natural variability. Unlike traditional methods that evaluate robustness of individual solutions post-optimization, the UPF framework directly optimizes a non-dominated front that inherently embeds robustness guarantees for the entire population [16]. For rugged landscape optimization, this approach enables maintenance of diverse solution populations that collectively navigate multiple promising regions while accounting for uncertainty in fitness evaluations—a common challenge in high-throughput screening and molecular dynamics simulations.

Experimental Protocols for Rugged Landscape Optimization

Protocol 1: Population Sizing for Rugged Landscape Exploration

Purpose: To determine the minimum population size required to reliably locate global optima in rugged fitness landscapes.

Materials:

- Computational environment with evolutionary algorithm framework

- Fitness landscape generator with adjustable ruggedness parameters

- Statistical analysis software

Procedure:

- Landscape Characterization: Quantify baseline ruggedness using fitness distance correlation and autocorrelation analysis [15]. Perform 100 random walks of 10,000 steps each, recording fitness at each step.

- Initial Population Setup: Initialize populations of sizes [50, 100, 200, 500, 1000] with identical random number seeds for comparative analysis.

- Evolutionary Run: Execute 500 generations of evolutionary search using tournament selection (size=3), uniform crossover (probability=0.8), and point mutation (probability=0.01).

- Performance Monitoring: Record best fitness, average fitness, and population diversity at generations 10, 50, 100, 250, and 500.

- Success Criterion Definition: Define successful optimization as locating a solution within 1% of known global optimum fitness.

- Statistical Validation: Repeat entire procedure 30 times with different random seeds to establish significance.

Data Analysis: Calculate success rates for each population size, plotting relationship between population size and optimization success. Fit logarithmic model to determine point of diminishing returns for population increases.

Protocol 2: UPF-Based Robust Optimization in Noisy Environments

Purpose: To implement Uncertainty-related Pareto Front optimization for maintaining solution diversity and robustness in rugged landscapes with noisy fitness evaluations.

Materials:

- RMOEA-UPF algorithm implementation [16]

- Noise injection module for simulating parameter uncertainty

- Multi-objective performance assessment metrics

Procedure:

- Uncertainty Modeling: Define noise distribution for fitness evaluations based on application context (Gaussian noise with μ=0, σ=0.05 recommended for initial trials).

- Archive Initialization: Establish elite archive with capacity for 100 non-dominated solutions using uncertainty-aware dominance criteria [16].

- Parent Selection: Generate parents directly from elite archive using crowding distance selection to maintain diversity.

- Offspring Generation: Apply simulated binary crossover and polynomial mutation to create 100 offspring solutions.

- Fitness Evaluation with Perturbation: Evaluate each solution under 10 different noise perturbations to estimate robustness [16].

- Archive Update: Incorporate new solutions into archive using non-dominated sorting with dual criteria of convergence and robustness.

- Termination Check: Continue for 500 generations or until Pareto front stabilization (less than 1% improvement for 50 generations).

Data Analysis: Compute hypervolume and inverted generational distance metrics to quantify performance. Compare solution diversity and robustness against traditional MOEA approaches.

Visualization Framework

Figure 1: Population-based search workflow with uncertainty handling. The diagram illustrates the integration of robustness assessment within the evolutionary cycle, highlighting the UPF update process for maintaining solutions that perform well under uncertainty.

Figure 2: Population sizing strategy matrix for different landscape types. The diagram illustrates optimal population size selection based on landscape ruggedness, demonstrating that larger populations are essential for success in highly rugged environments while smaller populations suffice for smooth landscapes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Rugged Landscape Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Ruggedness Analyzer | Quantifies fitness landscape characteristics using autocorrelation and fitness distance correlation | Preliminary problem analysis to determine appropriate population size | Requires significant sampling (≥10,000 evaluations) for accurate assessment |

| RMOEA-UPF Algorithm | Maintains diverse population of robust solutions under uncertainty | Optimization problems with noisy evaluations or parameter uncertainty | Archive size should be 50-100% of main population for effective diversity maintenance |

| Noise Injection Module | Introduces controlled perturbations to simulate real-world uncertainty | Testing algorithm robustness before deployment in experimental settings | Perturbation magnitude should reflect domain-specific uncertainty levels |

| Population Diversity Tracker | Monitors genotypic and phenotypic diversity throughout evolution | Preventing premature convergence in multimodal landscapes | Combine multiple metrics (Hamming distance, fitness variance, niche count) |

| Multi-objective Performance Assessor | Computes hypervolume, spread, and spacing metrics | Comparing algorithm performance across different rugged landscapes | Requires reference point selection appropriate to problem domain |

Population-based search strategies offer distinct advantages for navigating rugged optimization landscapes common in scientific and industrial applications. The integration of landscape-aware population sizing with robust optimization frameworks like UPF enables researchers to tackle increasingly complex parameter optimization challenges in domains ranging from drug discovery to materials science. The protocols and frameworks presented herein provide a structured approach for implementing these methods in research settings, with specific consideration for the uncertainty inherent in experimental sciences. Future directions include adaptive population sizing techniques and domain-specific implementations for pharmaceutical applications such as protein folding optimization and compound screening.

Why EAs Excel at Avoiding Local Optima in Complex Systems

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are a class of population-based, stochastic search methodologies inspired by the principles of natural evolution and genetics. Their fundamental strength in navigating complex, multi-modal search spaces and avoiding premature convergence on sub-optimal solutions stems from their core operational principles. Unlike gradient-based or local search methods that can become trapped in local optima—sub-optimal peaks in the fitness landscape—EAs maintain a diverse population of candidate solutions and employ biologically-inspired operators to explore and exploit the search space simultaneously [17]. This capability is paramount for solving real-world optimization problems in domains such as drug development, where the relationship between model parameters and objective functions is often non-convex, discontinuous, or poorly understood.

The inherent parallelism of EAs, evaluating multiple points in the search space at once, provides a statistical advantage against local optima. As summarized in Table 1, this, combined with their lack of dependency on gradient information and their explicit maintenance of diversity, forms the foundational reasons for their robustness. The following sections detail the architectural and operational mechanisms underpinning this capability, supported by application notes and detailed protocols for researcher implementation.

Table 1: Core Mechanisms in EAs for Avoiding Local Optima

| Mechanism | Principle | Effect on Local Optima |

|---|---|---|

| Population-Based Search | Evaluates many solutions simultaneously, exploring multiple regions of the search space. | Reduces the risk of the entire search process being captured by a single local optimum. |

| Stochastic Operators | Uses probabilistic operations (crossover, mutation) for exploration. | Allows random exploration that can escape the basin of attraction of a local optimum. |

| Diversity Preservation | Mechanisms like fitness sharing or crowding to maintain solution variety. | Prevents population convergence on a single peak, allowing other peaks to be explored. |

| Lack of Gradient Dependency | Relies on fitness evaluations, not gradient information, to guide the search. | Can traverse flat regions and jump across discontinuities where gradient-based methods fail. |

Architectural Framework and Operational Principles

The Self-Optimization EA Architecture

The ability to avoid local optima is embedded within the architecture of a self-optimizing EA. A generalized structure involves a main EA that, at a decision point ("time now"), initiates an optimization manager [18]. This manager interacts with an optimization algorithm (AO) to generate and test parameter sets.

- Manager Function: The manager requests a "set" of parameters from the optimization algorithm (AO) [18].

- Virtual Strategy (EA Virt): The manager passes this set to a virtual, fully functional copy of the trading strategy. This virtual EA runs on historical data from a defined "past" point up to the "time now" point, simulating performance without real-world execution [18].

- Fitness Evaluation (ff result): The virtual run produces a result based on a user-defined fitness function (e.g., profit factor, mathematical expectation). This result is returned to the manager [18].

- Iterative Optimization: The manager passes the fitness result back to the optimization algorithm. This cycle repeats—generating new parameter sets, testing them virtually, and evaluating results—until a stopping condition is met (e.g., a number of iterations or a fitness threshold). The best-found parameter set is then passed back to the main EA for live trading until the next re-optimization point [18].

This structure separates the exploration and evaluation phases, allowing for aggressive, risk-free exploration of the parameter space. The following DOT script visualizes this workflow and its data flows.

Key Evolutionary Operators for Global Exploration

The effectiveness of the architecture above depends on the algorithms (AO) it employs. Evolutionary Algorithms use specific operators to drive exploration and avoid local optima.

Table 2: Key Evolutionary Operators and Their Functions

| Operator | Function | Role in Avoiding Local Optima |

|---|---|---|

| Selection | Chooses fitter individuals from the population to be parents for the next generation. | Guides the search towards promising regions, exploiting current knowledge. |

| Crossover (Recombination) | Combines genetic information from two or more parents to create one or more offspring. | Explores new regions by recombining building blocks (schemata) from different solutions. |

| Mutation | Randomly alters one or more genes in an offspring's chromosome with a low probability. | Introduces new genetic material, enabling the search to reach entirely new points in the space and escape local optima. |

| Elitism | Directly copies a small proportion of the fittest individuals to the next generation. | Guarantees that the best solution found is not lost, ensuring monotonic improvement. |

Experimental Protocols for EA Evaluation

Protocol: Benchmarking EA Performance on Test Functions

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate and compare the performance of different EA configurations in avoiding local optima and finding the global optimum on known multi-modal test functions.

Materials:

- Software: Optimization software platform (e.g., MATLAB, Python with DEAP or PyGMO libraries).

- Hardware: Standard research computer.

- Test Functions: A suite of standard global optimization benchmark functions with known local and global optima (e.g., Rastrigin function, Ackley function, Schwefel function).

Procedure:

- EA Initialization:

- Select an EA variant (e.g., Genetic Algorithm, Differential Evolution).

- Define the population size (e.g., 50-100 individuals), crossover probability (e.g., 0.8-0.9), mutation probability (e.g., 1/chromosome_length), and selection strategy (e.g., tournament selection).

- Set the termination criterion (e.g., maximum number of generations, convergence threshold).

- Experimental Run:

- For each test function and each EA configuration, execute a minimum of 30 independent runs to account for stochasticity.

- In each run, initialize the population with random values within the defined search space.

- Data Collection:

- Record for each run: (a) the best fitness value found, (b) the number of function evaluations to reach the global optimum (or a close vicinity), and (c) the final population diversity.

- Track the best-so-far fitness curve over generations for a qualitative assessment of convergence behavior.

Analysis:

- Calculate the success rate (number of runs where the global optimum was found within a specified tolerance).

- Compare the mean and standard deviation of the best fitness and the number of function evaluations across different EA configurations using statistical tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney U test).

- Visually compare convergence plots to identify configurations that exhibit premature convergence versus those that maintain exploration.

Protocol: Implementing a Virtual Strategy for Parameter Optimization

Objective: To adapt the self-optimization architecture from Figure 1 for optimizing parameters of a computational model, such as a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model.

Materials:

- Target Model: The model to be optimized (e.g., a system of differential equations representing a PK/PD system).

- Dataset: Historical or synthetic dataset for the virtual evaluation of the model.

- Computational Environment: Python/R/MATLAB environment with the model implemented and an EA library.

Procedure:

- Setup:

- Implement the main EA manager script that will control the optimization loop.

- Encapsulate the target model as the "EA Virt" component, which can be called with a parameter set and return a fitness score (e.g., Root Mean Square Error between model output and dataset).

- Select and configure the optimization algorithm (AO), such as a Differential Evolution algorithm.

- Optimization Cycle:

- The manager initiates optimization at a defined point, passing the optimization parameters (ranges for each model parameter) to the AO.

- The AO provides a population of parameter sets.

- For each set, the manager calls the virtual model ("EA Virt"), runs the simulation on the dataset, and calculates the fitness.

- The fitness results are fed back to the AO.

- The cycle continues until the stopping condition is met.

- Validation:

- The best parameter set from the optimization is validated on a hold-out dataset not used during the optimization process.

Troubleshooting:

- Poor Convergence: Increase population size or adjust operator probabilities to enhance exploration.

- High Computational Cost: Reduce the population size or the complexity of the virtual model, if possible. Consider using a fitness approximation (surrogate model).

- Constraint Violation: Ensure the EA or the virtual model includes constraint-handling techniques (e.g., penalty functions) to manage parameter boundaries and model constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for EA Implementation

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Algorithm (AO) | The core engine that performs the evolutionary search for optimal parameters [18]. | Differential Evolution (DE), Genetic Algorithm (GA), Evolution Strategies (ES) [17]. |

| Virtual Strategy (EA Virt) | A virtual copy of the system or model being optimized; it tests parameter sets risk-free on historical or synthetic data [18]. | A computational model (e.g., a PK/PD simulation, a trading strategy back-testing engine). |

| Fitness Function (ff) | A user-defined metric that quantifies the performance of a parameter set, guiding the optimization process [18]. | Can be a single objective (e.g., minimization of error) or a complex, multi-objective criterion. |

| Historical/Synthetic Dataset | The data upon which the virtual strategy is evaluated. It must be representative of the system's behavior to ensure optimized parameters are valid [18]. | Clinical trial data, protein folding simulation outputs, historical financial data. |

| Visualization & Analysis Suite | Software tools for tracking algorithm performance, population diversity, and convergence behavior. | Python with Matplotlib/Seaborn, R with ggplot2, proprietary software. |

Advanced Hybridization and Error Correction

More advanced EA implementations incorporate hybrid and error-correction mechanisms to further bolster robustness. Hybrid approaches combine the global exploration of EAs with the local refinement of other methods (e.g., combining an EA with a gradient-based local search) [17]. This creates a powerful synergy where the EA finds the promising region, and the local search efficiently locates the precise local optimum within that region.

Furthermore, recognizing the potential for infeasible solutions to be generated by stochastic operators, integrated error-correction mechanisms can be deployed. These mechanisms use precisely tailored rules or prompts (especially in emerging LLM-EA hybrids) to "repair" generated solutions that violate problem constraints, ensuring all evaluated solutions are valid and saving computational resources [19]. The following diagram illustrates the population dynamics in a hybrid EA system.

Advanced EA Strategies and Their Transformative Applications in Drug Discovery

Differential Evolution (DE) is a population-based stochastic optimization algorithm widely recognized for its simplicity, robustness, and effectiveness in solving complex global optimization problems in continuous space [20] [21]. Since its introduction by Storn and Price in 1996, DE has become a cornerstone in the field of evolutionary algorithms, particularly for real-valued parameter optimization [21]. Its significance is highlighted by the continuous emergence of improved variants, many of which are benchmarked in prestigious annual competitions like the Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) [21]. Within research on evolutionary algorithms for parameter optimization, DE stands out for its performance on continuous problems, which are defined over a domain where solution quantities are assumed to be fields, often governed by differential equations or integral operations [22]. These characteristics make DE particularly valuable for researchers and scientists tackling challenging optimization problems in fields like drug development, where modeling complex, continuous systems is paramount [23].

Core Mechanisms of Differential Evolution

The DE algorithm operates on a population of candidate solutions, iteratively improving them through cycles of mutation, crossover, and selection. The following sections detail these core mechanisms.

Population Initialization and Dynamics

DE initializes a population of (Np) individuals, where each individual is represented as a vector (x{i,g}) in a D-dimensional continuous space. The index (i) denotes the individual's position in the population, and (g) represents the generation number. The initial population is typically generated uniformly at random within the specified lower and upper bounds for each variable [21]. The population size (N_p) is a critical parameter; a larger size promotes a more diverse exploration of the search space but at an increased computational cost [20]. The dynamics of this population throughout the generations drive the algorithm's convergence toward an optimal solution.

Mutation Strategies

Mutation is the primary mechanism for generating diversity in DE. It produces a mutant vector (v_{i,g+1}) for each target vector in the population by combining existing vectors. Several mutation strategies exist, each with distinct characteristics influencing the algorithm's explorative and exploitative behavior [20].

Common mutation strategies include:

- DE/rand/1: ( \vec{v}i = \vec{x}{r1} + F \times (\vec{x}{r2} - \vec{x}{r3}) ) - An explorative strategy that relies on randomly selected vectors.

- DE/best/1: ( \vec{v}i = \vec{x}{best} + F \times (\vec{x}{r1} - \vec{x}{r2}) ) - An exploitative strategy that leverages the best solution found so far to direct the search.

- DE/current-to-best/1: ( \vec{v}i = \vec{x}i + F \times (\vec{x}{best} - \vec{x}i) + F \times (\vec{x}{r1} - \vec{x}{r2}) ) - A balanced strategy that incorporates information from both the current individual and the best individual.

In all equations, (r1), (r2), and (r3) are randomly selected, mutually distinct indices different from (i), and (F) is the scaling factor controlling the magnitude of the differential variation [20] [21].

Table 1: Characteristics of Common DE Mutation Strategies

| Mutation Strategy | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| DE/rand/1 | Explorative, simple, maintains diversity |

| DE/best/1 | Exploitative, fast convergence, can stagnate |

| DE/current-to-best/1 | Balanced exploration and exploitation |

Crossover and Selection

Following mutation, a crossover operation generates a trial vector (u{i,g+1}) by mixing components from the target vector (x{i,g}) and the mutant vector (v{i,g+1}). The most common method is binomial crossover, defined as: [ u{ji,g+1} = \begin{cases} v{ji,g+1} & \text{if } rand(j) \leq Cr \text{ or } j = rn(i) \ x{ji,g} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} ] Here, (Cr) is the crossover rate, (rand(j)) is a uniform random number from [0,1], and (rn(i)) is a randomly chosen index ensuring the trial vector gets at least one component from the mutant vector [21].

Finally, a greedy selection mechanism determines whether the target vector or the trial vector survives to the next generation. The selection is based on the fitness function, typically for minimization: [ x{i,g+1} = \begin{cases} u{i,g+1} & \text{if } f(u{i,g+1}) \leq f(x{i,g}) \ x_{i,g} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} ] This selection pressure ensures the population's average fitness improves over generations [20] [21].

Modern Variants and Advanced Topics

Recent research has focused on enhancing DE's effectiveness and efficiency through adaptive mechanisms, hybridization, and specialized procedures for complex problem classes.

Adaptive and Self-Adaptive DE

A significant advancement in DE is the development of adaptive and self-adaptive variants that dynamically adjust control parameters like the scaling factor (F) and crossover rate (Cr) during the optimization process. This self-tuning capability improves robustness and eliminates the need for tedious manual parameter tuning for each new problem. These methods work by using feedback from the optimization process or embedding the parameters within the individual's representation so they evolve alongside the solutions [20].

Hybrid Differential Evolution

Hybridizing DE with other algorithms is a promising approach to overcome its limitations. Common hybrids include:

- DE with Local Search: Combining DE with gradient-based methods or the Nelder-Mead simplex improves local exploitation, refining solutions and accelerating convergence [20].

- DE with other Population-based Algorithms: Integrating DE with algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) or Genetic Algorithms (GA) can enhance global exploration capabilities and population diversity [20].

Multi-Objective Optimization

DE has been successfully extended to multi-objective optimization (MOO) problems, where multiple conflicting objectives must be optimized simultaneously. Popular DE variants for MOO use Pareto-based approaches to select and maintain a set of non-dominated solutions or decomposition methods that break the MOO problem into multiple single-objective subproblems [20].

Local Minima Escape Procedure

A key challenge for DE is premature convergence to local minima. A recent innovation, the Local Minima Escape Procedure (LMEP), directly addresses this issue [24]. LMEP detects when a population is trapped and executes a "parameter shake-up" to disrupt the stagnant state, allowing the algorithm to explore new regions of the search space. When integrated with classical DE strategies, LMEP has been shown to improve convergence by 25% to 100% on challenging benchmark functions and real-world problems like optimizing quantum simulations of photosynthetic complexes [24].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Analysis

Robust experimental design and statistical analysis are essential for validating the performance of DE algorithms, especially when comparing modern variants.

Benchmarking and Statistical Comparison

Performance evaluation of DE variants typically relies on standardized benchmark suites, such as those defined for the CEC special sessions on single-objective real-parameter numerical optimization. These suites contain various function types, including unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions, tested at different dimensions (e.g., 10D, 30D, 50D, and 100D) [21].

Since DE is stochastic, algorithms are run multiple times on each benchmark. Statistical tests are then used to draw reliable conclusions from the resulting data. Non-parametric tests are preferred because they do not assume a normal distribution of the results [21].

Table 2: Statistical Tests for Comparing DE Algorithm Performance

| Statistical Test | Purpose | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test | Pairwise comparison of two algorithms | Considers the magnitude of differences in performance ranks; used for paired samples (same problems). |

| Friedman Test | Multiple comparison of several algorithms | Ranks algorithms for each problem; detects significant differences in median performance across multiple algorithms. |

| Mann-Whitney U-score Test | Pairwise comparison of two algorithms | Ranks all results from both algorithms; designed for independent samples. |

Protocol: Conducting a Performance Comparison Study

- Problem Selection: Select a benchmark suite (e.g., CEC 2024) and define the problem dimensions for testing [21].

- Algorithm Configuration: Implement the DE variants to be compared, ensuring consistent coding environment and hardware.

- Data Collection: Execute each algorithm over multiple independent runs (e.g., 30-51 runs are common) for each benchmark function. Record the final objective function value or the error from the known optimum for each run.

- Statistical Testing:

- Perform the Friedman test to determine if there are statistically significant differences among all algorithms. If the result is significant, conduct a post-hoc Nemenyi test to identify which specific pairs differ [21].

- For focused comparisons, use the Wilcoxon signed-rank test on the average performance from multiple runs for each benchmark to compare two algorithms [21].

- Alternatively, apply the Mann-Whitney U-score test on the collected results to compare two algorithms across different trials [21].

- Reporting: Report the p-values and test statistics. A p-value below the significance level (e.g., α=0.05) allows rejection of the null hypothesis, indicating a statistically significant performance difference.

Protocol: Implementing the Local Minima Escape Procedure

The following protocol details the integration of LMEP into a standard DE routine, based on the method described by Chesalin et al. (2025) [24].

Objective: To enhance the convergence rate of a standard DE algorithm by enabling it to detect and escape from local minima. Materials: A functioning DE codebase (e.g., in Python, MATLAB, C++). Procedure:

- Define LMEP Parameters: Set the trigger condition for LMEP (e.g., no improvement in the best fitness over a consecutive number of generations, (G_{stag})) and the magnitude of the "shake-up" (e.g., a perturbation factor).

- Incorporate Detection: Within the main DE loop, after the selection step in each generation, monitor the best solution in the population for improvement.

- Trigger and Execute LMEP: If the stagnation criterion (G_{stag}) is met: a. Detection: Flag the current best solution as a potential local minimum. b. Shake-up: Apply a perturbation to the entire current population or a subset of individuals. This could involve: - Re-initializing a percentage of the population randomly within the bounds. - Applying a strong mutation to all individuals except the current best. - Randomly shifting all individuals by a random vector. c. Resume DE: Continue the standard DE operations (mutation, crossover, selection) with the perturbed population.

- Termination: Continue the process until a global termination criterion is met (e.g., maximum number of generations or function evaluations, or a desired fitness threshold).

Validation: Test the performance of DE with and without LMEP on benchmark functions with many local minima, such as Rastrigin and Griewank. Compare the convergence curves and the success rate in locating the global optimum over multiple runs [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section provides key resources for researchers implementing and applying Differential Evolution.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a DE Implementation

| Component / "Reagent" | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Population Vector ((x_{i,g})) | The fundamental unit representing a candidate solution in the D-dimensional search space. |

| Scaling Factor ((F)) | Controls the magnitude of the differential variation during mutation, impacting the algorithm's step size. |

| Crossover Rate ((Cr)) | Determines the probability of incorporating a component from the mutant vector into the trial vector, balancing old and new genetic information. |

| Mutation Strategy (e.g., DE/rand/1) | The "recipe" for generating mutant vectors, defining the algorithm's explorative/exploitative character. |

| Fitness Function ((f(x))) | The objective function that evaluates the quality of a solution, guiding the selection process. |

| Benchmark Suite (e.g., CEC2024) | A standardized set of test problems for validating algorithm performance and conducting fair comparisons. |

Visualization of Algorithm Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow of a standard DE algorithm and the enhanced version with the Local Minima Escape Procedure.

DE Algorithm Basic Workflow

DE Enhanced with Local Minima Escape

Application in Pharmaceutical Process Development

Optimization is critical in pharmaceutical process development, impacting areas from drug substance manufacturing to final product formulation. DE is applied to optimize Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), process performance (yield, material demand), economic objectives (capital, operational expenditures), and environmental metrics (energy demand, waste) [23]. A specific application involves using machine learning-based optimization frameworks, which can be coupled with DE, to optimize multi-step ion exchange chromatography for complex ternary protein separations, ensuring compliance with operational and quality constraints [23]. The robustness of DE in handling complex, constrained, continuous problems makes it a valuable tool for improving the efficiency and sustainability of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Optimization of chemical systems and processes has been profoundly enhanced by the development of sophisticated algorithms. While numerous methods exist to systematically investigate how variables correlate with outcomes, many require substantial experimentation to accurately model these relationships. As chemical systems grow in complexity, there is a pressing need for algorithms that can propose efficient experiments to optimize objectives while avoiding convergence on local minima [25]. Evolutionary optimization algorithms, inspired by biological evolution, represent a powerful class of such methods. They use a starting set of potential solutions (seeds) that are evaluated using an objective function to iteratively evolve a population of solution vectors toward optimal solutions [25] [26].

The Paddy field algorithm (PFA), implemented as the Paddy software package, is a recently developed evolutionary optimization algorithm that demonstrates particular promise for chemical applications. As a biologically inspired method, Paddy propagates parameters without direct inference of the underlying objective function, making it particularly valuable when the functional relationship between variables is unknown [25] [27]. Benchmarked against established optimization approaches including Bayesian methods and other evolutionary algorithms, Paddy maintains strong performance across diverse optimization challenges while offering markedly lower runtime [25].

This case study examines Paddy's implementation, performance, and practical applications in chemical optimization tasks, with particular emphasis on its value for researchers in chemical sciences and drug development.

Algorithmic Fundamentals and Mechanism of Action

Core Principles and Biological Inspiration

The Paddy field algorithm is inspired by the reproductive behavior of plants in agricultural settings, specifically how plant propagation correlates with soil quality and pollination efficiency. This biological metaphor translates to optimization as follows: parameters are treated as seeds, their fitness scores represent plant quality, and the density of successful solutions drives a pollination mechanism that guides further exploration [25].

Unlike traditional evolutionary algorithms that rely heavily on crossover operations, Paddy employs a density-based reinforcement mechanism where solution vectors (plants) produce offspring based on both their fitness scores and their spatial distribution within the parameter space. This approach allows Paddy to effectively balance exploration (searching new areas) and exploitation (refining promising solutions) [25].

The Five-Phase Process

Paddy implements optimization through five distinct phases:

Sowing: The algorithm initializes with a random set of user-defined parameters as starting seeds. The exhaustiveness of this initial step significantly influences downstream propagation, with larger seed sets providing better starting points at the cost of computational resources [25].

Selection: The fitness function evaluates the seed parameters, converting seeds to plants. A user-defined threshold parameter then selects the top-performing plants based on sorted fitness values. Notably, Paddy can incorporate evaluations from previous iterations, enabling cumulative learning [25].

Seeding: Selected plants produce seeds proportionally to their fitness scores, with the number of seeds determined as a fraction of a user-defined maximum. This fitness-proportional reproduction ensures promising regions of parameter space receive more attention [25].

Pollination: A density-based calculation influences offspring production, with higher concentrations of successful plants resulting in more intensive sampling of surrounding regions. This unique mechanism mimics how plants in dense clusters benefit from increased pollination [25].

Propagation: Parameter values for the next generation are created by applying Gaussian mutation to selected plants, introducing controlled randomness to explore adjacent parameter space [25].

The table below summarizes Paddy's comparative performance against other optimization methods:

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Paddy Against Other Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Optimization Approach | Key Strengths | Chemical Applications Demonstrated | Runtime Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paddy | Evolutionary with density-based pollination | Robust versatility, avoids local minima, excellent runtime | Molecule generation, hyperparameter tuning, experimental planning | Excellent |

| Bayesian Optimization (Gaussian Process) | Probabilistic model with acquisition function | Sample efficiency with minimal evaluations | Neural network optimization, generative sampling | Computational cost increases with complexity |

| Tree-structured Parzen Estimator | Sequential model-based optimization | Handles complex search spaces | Hyperparameter optimization [25] | Moderate to high |

| Genetic Algorithm | Evolutionary with crossover and mutation | Well-established, diverse solution generation | Various engineering and chemical applications [26] | Varies with implementation |

| Differential Evolution | Evolutionary with vector differences | Effective for continuous optimization, prevents local minima | Function optimization in continuous space [26] | Generally good |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the five-phase iterative workflow of the Paddy algorithm:

Paddy Algorithm Five-Phase Workflow

Experimental Applications in Chemical Optimization

Molecular Optimization for Drug Discovery

Paddy demonstrates particular strength in targeted molecule generation, a crucial task in drug discovery. Researchers have employed Paddy to optimize input vectors for a junction-tree variational autoencoder (JT-VAE), a generative model for molecular structures [25] [28]. In this application, Paddy efficiently navigates the complex latent space of the decoder network to generate molecules with optimized properties.

The algorithm's ability to avoid local optima proves valuable when searching for molecular structures with specific pharmaceutical characteristics. Unlike some Bayesian methods that may prematurely converge on suboptimal regions of chemical space, Paddy's density-based pollination mechanism maintains diverse exploration, increasing the probability of discovering novel scaffolds with desired properties [25].

Hyperparameter Optimization for Chemical AI Models

Artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) models have become indispensable in chemical sciences for tasks ranging from retrosynthesis planning to reaction condition prediction [25]. The performance of these models heavily depends on proper hyperparameter tuning.

Paddy has been successfully benchmarked for hyperparameter optimization of artificial neural networks tasked with classifying solvents for reaction components [25] [27]. In these experiments, Paddy efficiently navigated the hyperparameter space to identify configurations that maximized classification accuracy. The algorithm's robust performance across different problem types—from mathematical functions to chemical classification—highlights its versatility as an optimization tool [25].

Autonomous Experimental Planning and Closed-Loop Optimization

A promising application of Paddy lies in autonomous experimentation, where the algorithm can propose optimal experimental conditions with minimal human intervention. This capability is particularly valuable for high-throughput experimentation in pharmaceutical and materials science [25] [28].

Paddy has demonstrated effectiveness in sampling discrete experimental space for optimal experimental planning [25]. When integrated with robotic laboratory systems, Paddy can function as the decision-making engine in closed-loop optimization systems, similar to implementations using Bayesian optimization [29]. The algorithm's lower runtime compared to Bayesian methods makes it particularly suitable for time-sensitive applications where rapid iteration between proposal and experimentation is valuable [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Implementation for Targeted Molecule Generation

This protocol describes the application of Paddy for targeted molecule generation using a pre-trained junction-tree variational autoencoder (JT-VAE), based on methodologies reported in benchmark studies [25].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Specification/Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Paddy Software Package | Python library (v1.0+) | Core optimization algorithm implementation |

| JT-VAE Model | Pre-trained generative model | Molecular structure decoding from latent vectors |

| Chemical Property Predictor | QSAR model or computational function | Evaluates desired molecular properties (fitness function) |

| Molecular Descriptors | Tanimoto similarity, logP, etc. | Quantifies chemical similarity and properties |

| Python Environment | 3.7+ with NumPy/SciPy | Experimental execution and data analysis |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Initialization and Parameter Definition

- Install the Paddy package via PyPI (

pip install paddy-optimizer) or from GitHub repository. - Define the parameter space for latent vectors, specifying bounds for each dimension based on the JT-VAE's latent space characteristics.

- Set Paddy parameters: population size (default: 50-100), maximum number of seeds (s_max), selection threshold (H), and Gaussian mutation radius.

- Install the Paddy package via PyPI (

Fitness Function Formulation

- Develop a fitness function that incorporates desired molecular properties (e.g., drug-likeness, target affinity, synthetic accessibility).

- The function should: decode latent vectors to molecular structures using JT-VAE, calculate chemical properties, and return a composite fitness score.

- Example function structure:

Algorithm Execution

- Initialize Paddy with random latent vectors within defined bounds.

- Run the optimization for predetermined iterations or until convergence criteria are met.

- Monitor progress through fitness scores of best candidates each generation.

Result Analysis and Validation

- Extract top-performing latent vectors and decode to molecular structures.

- Validate chemical properties using independent assessment methods.

- Analyze chemical diversity of generated molecules to evaluate exploration effectiveness.

Protocol for Hyperparameter Optimization of Neural Networks

This protocol applies Paddy to tune hyperparameters of neural networks for chemical classification tasks, such as solvent classification based on molecular features [25].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Search Space Definition

- Identify critical neural network hyperparameters: learning rate, hidden layer dimensions, dropout rate, batch size, etc.

- Define valid ranges for each parameter (continuous or discrete).

Fitness Function Implementation

- Implement function that: instantiates neural network with proposed hyperparameters, trains on chemical dataset, evaluates on validation set, returns performance metric (accuracy, F1-score, etc.).

- Incorporate computational efficiency constraints if needed.

Paddy Configuration

- Adjust selection threshold to maintain population diversity and prevent premature convergence.

- Set appropriate Gaussian mutation ranges for each parameter type.

Parallelization Strategy

- Leverage Paddy's capability to propose parallel evaluations when computational resources allow.

- Execute multiple neural network training sessions concurrently to accelerate optimization.

Technical Advantages and Implementation Considerations

Comparative Strengths for Chemical Applications

Paddy's performance across chemical optimization benchmarks reveals several distinct advantages:

Resistance to Local Minima: The density-based pollination mechanism prevents premature convergence, a critical feature when optimizing complex chemical systems with multiple suboptimal regions [25].

Runtime Efficiency: Studies report "markedly lower runtime" compared to Bayesian optimization approaches, making Paddy suitable for computationally expensive fitness functions [25] [27].

Versatility Across Problem Types: Paddy maintains robust performance across diverse optimization challenges, from mathematical functions to chemical latent space navigation and experimental planning [25].

Minimal Functional Assumptions: Unlike Bayesian methods that build probabilistic models of the objective function, Paddy operates without direct inference of underlying relationships, advantageous when these relationships are complex or unknown [25].

Practical Implementation Guidelines

Successful implementation of Paddy requires careful consideration of several factors:

Parameter Tuning: While Paddy has fewer hyperparameters than some alternatives, appropriate setting of population size, selection threshold, and mutation radius significantly impacts performance.

Constraint Handling: For chemical applications with practical constraints, implement boundary checks in the fitness function or parameter encoding.

Categorical Parameters: Future developments could enhance Paddy's handling of categorical variables (e.g., catalyst types, solvent classes), potentially drawing inspiration from approaches used in Bayesian optimization [29].

The Paddy algorithm represents a valuable addition to the computational chemist's toolkit, particularly for optimization challenges where traditional methods struggle with complex landscapes or excessive computational demands. Its biological inspiration translates to practical advantages in chemical optimization tasks, from molecular design to experimental planning.

As chemical systems grow in complexity and high-throughput experimentation becomes increasingly automated, algorithms like Paddy that efficiently navigate parameter spaces without premature convergence will play a crucial role in accelerating discovery. The continued development and application of evolutionary optimization methods, including Paddy, promises to enhance our ability to solve challenging optimization problems across chemical sciences and drug development.

Paddy's open-source availability, documented performance benchmarks, and modular implementation make it well-suited for adoption by research teams seeking robust optimization solutions for chemical applications [25] [28].

The advent of ultra-large, make-on-demand compound libraries, such as the Enamine REAL space, which contains billions of readily synthesizable molecules, presents a transformative opportunity for in-silico drug discovery [30] [31]. However, the computational cost of exhaustively screening these vast libraries using flexible protein-ligand docking protocols has been a significant bottleneck. The REvoLd (RosettaEvolutionaryLigand) algorithm directly addresses this challenge by implementing an evolutionary algorithm to efficiently navigate combinatorial make-on-demand chemical spaces without the need to enumerate all possible molecules [30] [31]. By exploiting the inherent combinatorial structure of these libraries—defined by lists of substrates and chemical reactions—REvoLd achieves extraordinary efficiency, benchmarking on five drug targets showed improvements in hit rates by factors between 869 and 1,622 compared to random selection [30] [32] [31]. This capability frames REvoLd as a critical methodological advancement within the broader thesis of evolutionary algorithms for parameter optimization, demonstrating their power to solve complex, high-dimensional search problems in structural biology and drug discovery.

Algorithmic Framework and Workflow

Core Evolutionary Mechanics

REvoLd operationalizes Darwinian principles of evolution within the context of computational molecular design. The algorithm begins with a population of randomly generated molecules and applies selective pressure based on a fitness function, which is typically the protein-ligand interface energy calculated through RosettaLigand's flexible docking protocol [33] [34]. Individuals with higher fitness (lower binding energy) are preferentially selected to "reproduce" for the next generation. Reproduction occurs through genetic operators tailored for combinatorial chemistry spaces, including: