Evo-Devo Synthesis: From Developmental Mechanisms to Biomedical Innovation

This article synthesizes the transformative impact of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) on modern biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

Evo-Devo Synthesis: From Developmental Mechanisms to Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article synthesizes the transformative impact of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) on modern biomedical research and therapeutic discovery. It explores the foundational principles of eco-evo-devo that integrate environmental, developmental, and evolutionary processes, examines cutting-edge methodological approaches using model organisms like zebrafish, addresses key challenges in translating developmental insights into clinical applications, and validates evo-devo's utility through comparative physiological and regenerative studies. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this comprehensive analysis demonstrates how developmental mechanisms underlying evolutionary diversity are revolutionizing our approach to disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine.

Beyond Genes: The Conceptual Framework of Eco-Evo-Devo

In evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo), the reaction norm—describing the phenotypic expression of a genotype across an environmental gradient—has emerged as a central concept for understanding how organisms respond to environmental variation [1]. Rather than serving as mere statistical descriptors, reaction norms represent the mechanistic bridge through which ecological contexts influence developmental processes to generate phenotypic diversity [2] [3]. The emerging field of Ecological Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Eco-Evo-Devo) aims to transform our understanding of reaction norms from phenomenological correlations to causal mechanisms that explain how these environmental responses arise during development and evolve over time [2] [3].

This paradigm shift moves beyond classic approaches that primarily established correlations between environmental and phenotypic changes. Instead, it seeks to uncover the developmental genetic pathways, environmental sensing mechanisms, and epigenetic processes that generate specific reaction norm shapes [2]. This deeper understanding is increasingly crucial as researchers investigate how organisms respond and evolve in relation to rapidly changing environments, with significant implications for predicting adaptive responses to climate change, improving crop resilience, and understanding disease mechanisms [2] [4].

The Conceptual Framework: From Description to Causation

Defining Reaction Norms in Developmental Context

A reaction norm describes the sensitivity of an organism, or a set of organisms sharing the same genotype, to specific environmental variables [1]. It quantitatively captures phenotypic change—or lack thereof—across an environmental gradient, representing a fundamental property of the phenotype that is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors during development [1]. The contemporary Eco-Evo-Devo framework challenges the classic view that privileges genetics as the sole central factor in shaping phenotypic evolution, instead providing a more comprehensive approach to understanding complex interactions between environment, ontogeny, and inheritance in diversification [2] [3].

Table 1: Key Properties of Reaction Norms in Developmental Context

| Property | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Slope | Degree of phenotypic change per unit environmental change | Quantifies plasticity; zero slope indicates environmental insensitivity |

| Shape | Linear, quadratic, threshold, or other nonlinear forms | Reveals complex genotype-environment interactions |

| Intercept | Baseline phenotypic value in a reference environment | Represents genotypic mean independent of plasticity |

| Variation | Differences in reaction norms among genotypes | Provides raw material for evolution of plasticity |

Causal Flows in Reaction Norm Development

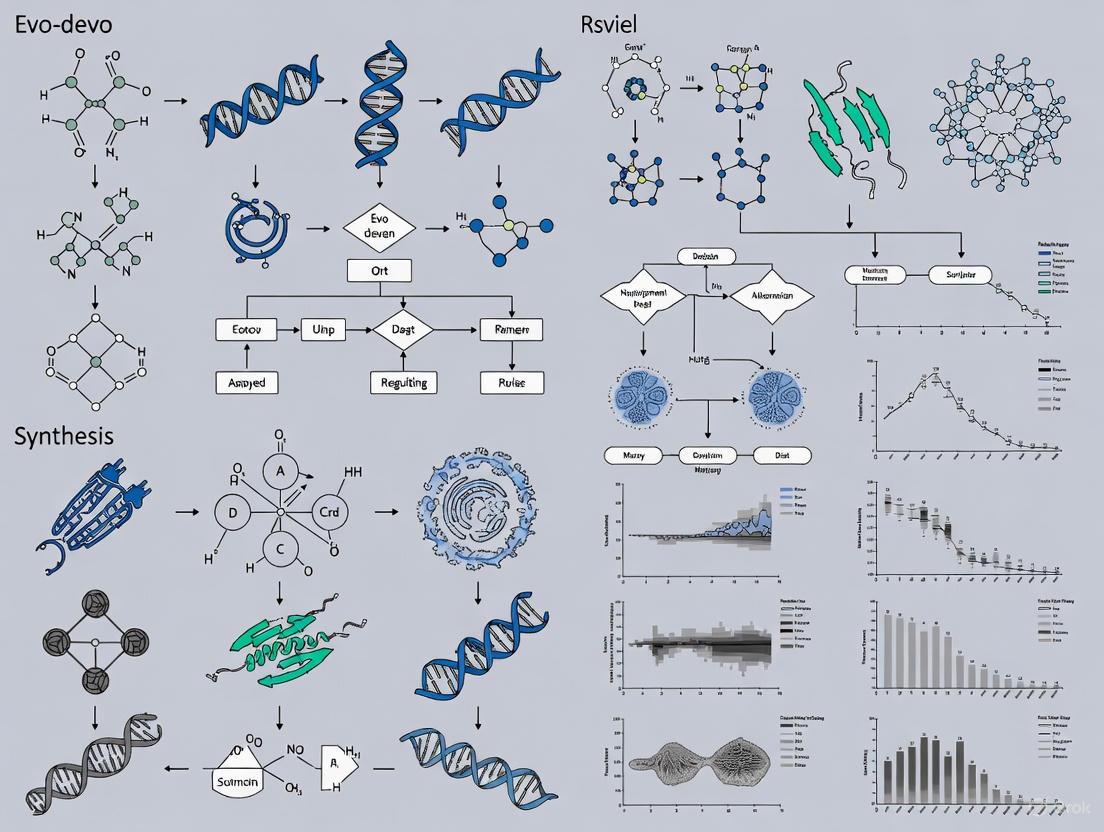

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework through which causal mechanisms, rather than mere correlations, generate reaction norms within the Eco-Evo-Devo paradigm:

Quantitative Genetic Architecture of Reaction Norms

Variance Partitioning Framework

Understanding the evolution of reaction norms requires precise quantification of their genetic and environmental components. A recently developed partitioning framework distinguishes several sources of variation [5]:

- Average Reaction Norm: Phenotypic variance arising from the average reaction norm across genotypes

- Genetic Variation in Reaction Norms: Additive and non-additive genetic components underlying plasticity

- Residual Variance: Unexplained variation not predicted from genotype and environment

This approach employs the reaction norm gradient to decompose additive genetic components according to the relative contributions from each parameter, providing a general framework applicable from character-state to curve-parameter approaches, including polynomial functions and arbitrary non-linear models [5].

Table 2: Variance Components in Reaction Norm Analysis

| Variance Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Variance (Vg) | σ²g | Variation due to genotype differences in reference environment |

| Environmental Variance (Ve) | σ²e | Variation due to environmental differences |

| Plasticity Variance (Vp) | σ²p | Variation due to differences in slope of reaction norms |

| G×E Interaction Variance | σ²g×e | Non-additive effects of genotype and environment |

| Developmental Noise | σ²ε | Unexplained residual variance |

Case Study: Genetic Architecture of Flowering Time in Sorghum

A comprehensive study on sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) demonstrated the power of combining reaction norm analysis with genomic approaches. Researchers evaluated a diverse panel of 306 sorghum lines across 14 natural field environments to investigate the phenotypic plasticity of flowering time and plant height [4].

The environmental index identification revealed that growing degree days (GDD) during early development served as the primary environmental cue shaping flowering time reaction norms, while diurnal temperature range (DTR) predominantly influenced plant height plasticity [4]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) conducted on reaction norm parameters (intercept and slope) detected distinct genetic loci:

- 10 novel genomic regions associated with plasticity parameters

- Known maturity genes (Ma1) and dwarfing genes (Dw1-Dw4, qHT7.1)

- Separate genetic architectures for mean trait value (intercept) versus plasticity (slope)

This genetic dissection revealed that different sets of loci control the average phenotype versus environmental responsiveness, demonstrating the complex genetic architecture underlying reaction norms [4].

Experimental Approaches: From Phenotype to Mechanism

Protocol: Reaction Norm Quantification in Controlled Environments

Objective: To characterize reaction norms for a developmental trait across an environmental gradient and partition phenotypic variance into genetic and environmental components.

Materials:

- Multiple genotypes (inbred lines, clones, or genotypes with known relatedness)

- Environmental chambers or gradient facilities

- Trait-specific measurement equipment

- Environmental monitoring sensors

Procedure:

- Experimental Design:

- Establish multiple replicates of each genotype across each environmental level

- Randomize positions to control for micro-environmental variation

- Include sufficient replication for statistical power (≥5 replicates per genotype per environment)

Environmental Gradient Establishment:

- Define relevant environmental axis (temperature, nutrient, light, etc.)

- Establish at least 5 distinct levels spanning the ecologically relevant range

- Maintain other environmental factors constant or randomized

Phenotypic Measurement:

- Measure developmental traits at appropriate ontogenetic stages

- Record multiple traits to assess trait integration

- Document developmental timing and rates

Data Analysis:

- Fit reaction norms for each genotype using appropriate models (linear, quadratic, etc.)

- Calculate reaction norm parameters (intercept, slope, curvature)

- Estimate variance components using mixed models

- Quantify G×E interactions using ANOVA or factor analytic models

Statistical Analysis: The mixed model for reaction norm analysis takes the form: y = μ + G + E + G×E + ε Where y is the phenotypic value, μ is the overall mean, G is the genotype effect, E is the environmental effect, G×E is the genotype-by-environment interaction, and ε is the residual error [5].

Protocol: GWAS of Plasticity Parameters

Objective: To identify genetic loci associated with reaction norm parameters (intercept and slope).

Procedure:

- Phenotype Collection: Measure traits of interest across multiple environments as described in Protocol 4.1.

Environmental Index Calculation:

- Calculate environmental means for each environment

- Identify critical environmental regressor using CERIS algorithm or similar approach

- Center environmental index to make intercept biologically meaningful

Reaction Norm Parameter Estimation:

- For each genotype, regress phenotypic values on environmental index

- Extract intercept (average phenotypic value) and slope (plasticity)

- Assess goodness-of-fit and consider non-linear models if appropriate

Genome-Wide Association:

- Perform GWAS on intercept and slope parameters separately

- Use appropriate population structure controls

- Apply multiple testing corrections

- Validate associations in independent populations

This approach successfully identified distinct genetic architectures for mean flowering time versus flowering time plasticity in sorghum, with the slope parameter (plasticity) capturing loci that would be missed in single-environment studies [4].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Reaction Norm Analysis

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Common Garden Experiments | Controls environmental variation to isolate genetic effects | Quantifying genetic differences in plasticity among populations |

| Environmental Chamber Arrays | Precisely controls environmental conditions | Establishing temperature or photoperiod reaction norms |

| Genetic Recombinant Lines | Provides replication of specific genotypes | Partitioning genetic and environmental variance components |

| Environmental Sensors (T, RH, Light) | Quantifies micro-environmental conditions | Characterizing actual environments experienced by organisms |

| CERIS Algorithm | Identifies critical environmental regressors | Determining which environmental factor shapes plasticity |

| Reacnorm R Package | Implements variance partitioning framework | Quantifying genetic and environmental variance components |

| Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) | Extracts interpretable features from complex data | Analyzing high-dimensional phenotypic data |

Causal Mechanisms: Developmental Pathways Underlying Plasticity

Signaling Pathways in Environmental Response

The following diagram illustrates the integrated signaling pathways through which environmental cues are transduced into developmental responses, generating reaction norms across environmental gradients:

Case Study: Thermal Reaction Norms in Antarctic Bivalve

Research on the Antarctic bivalve Laternula elliptica provides a detailed example of causal mechanism investigation [1]. Scientists characterized the thermal reaction norm by identifying optimal, pejus (transitional), critical, and lethal temperature thresholds through integrated physiological measurements:

- Oxygen consumption rates tracked aerobic capacity across temperatures

- Heart rate measured cardiovascular performance

- Intracellular pH indicated acid-base balance

- Citrate synthase activity reflected mitochondrial function

- Adenylate concentrations quantified cellular energy status

- Succinate accumulation marked anaerobic metabolism

This multi-level approach revealed that the upper thermal limits emerged when temperature-dependent increases in oxygen demand could not be matched by oxygen delivery systems, causing a decline in aerobic scope and transition to anaerobic metabolism [1]. Experimental manipulation of oxygen availability (hypoxia, normoxia, hyperoxia) confirmed that oxygen limitation constituted the causal mechanism setting thermal boundaries, with hyperoxia increasing upper thermal limits by 1-1.5°C [1].

Evolutionary Implications: Development, Plasticity, and Adaptation

The reaction norm concept has fundamentally reshaped understanding of evolutionary processes by revealing how developmental mechanisms influence evolutionary trajectories. The emerging Eco-Evo-Devo synthesis emphasizes several key evolutionary implications:

Developmental Bias and Constraints

Developmental processes do not produce isotropic variation—some phenotypic changes are more likely than others due to the structure of developmental systems [2] [3]. This developmental bias shapes evolutionary diversification by making certain trajectories more accessible than others [6]. Rather than viewing development solely as a constraint, the reaction norm perspective highlights how developmental processes can facilitate adaptation by generating coordinated phenotypic responses to environmental challenges [3].

Plasticity-Led Evolution

Reaction norms can precede and guide genetic evolution through a process termed plasticity-led evolution [6]. When developmental systems produce adaptive phenotypes in new environments, subsequent genetic changes can stabilize these phenotypes through genetic assimilation. This mechanism provides a pathway for rapid adaptation to environmental change that does not rely solely on de novo mutations.

Niche Construction and Reciprocal Causation

Organisms actively modify their environments through nice construction, creating feedback loops between developmental processes and selective environments [6]. The reaction norms of one generation can shape the environmental conditions experienced by subsequent generations, creating reciprocal causation between development and evolution. This perspective emphasizes organisms as active agents in evolutionary processes rather than passive objects of selection [6].

Future Directions: Integrating Reaction Norms Across Biological Scales

The transformation from correlative to causal understanding of reaction norm development requires integration across biological scales—from molecular mechanisms to evolutionary patterns. Promising research directions include:

Mechanistic Studies of Developmental-Environmental Interactions: Uncovering the specific sensors, signal transducers, and gene regulatory networks that convert environmental variation into developmental responses [2].

Symbiotic Development: Expanding beyond genetic determinism to understand how microbial partners and holobiont systems contribute to reaction norm development [2] [3].

Integrative Modeling: Developing models that connect molecular mechanisms to phenotypic outcomes across environmental gradients, enabling prediction of responses to novel environments [5] [4].

Cross-Taxa Comparative Approaches: Identifying conserved and divergent mechanisms of reaction norm development across the tree of life [2].

As the Eco-Evo-Devo framework continues to mature, the reaction norm concept provides a powerful integrator for understanding how environmental cues, developmental mechanisms, and evolutionary processes interact to generate the breathtaking diversity of life [2] [3]. This integrated perspective is essential for addressing fundamental biological questions and developing predictive frameworks for how organisms will respond to rapid environmental change.

Developmental bias and constraint represent fundamental concepts within the evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) synthesis, describing how the structure and dynamics of developmental processes systematically channel phenotypic variation along specific paths. These mechanisms generate non-random phenotypic distributions that influence both the tempo and direction of evolutionary change. The distinction between bias and constraint is primarily one of emphasis: where developmental constraint traditionally highlights how developmental processes limit certain phenotypic possibilities, developmental bias stresses how these same processes facilitate and promote others [6]. This conceptual framework moves beyond the gene-centric view of evolution that dominated 20th-century biology, which primarily conceptualized evolution as changes in gene frequencies, often assuming reasonably stable gene effects across generations [6].

The contemporary evo-devo perspective recognizes that developmental processes themselves evolve, creating reciprocal relationships between development and evolution. As Lala and colleagues argue in "Evolution Evolving," this reoriented perspective necessitates a re-conception of what evolution is, not merely a demonstration of development's relevance to evolutionary biology [6]. This viewpoint embraces a pluralistic explanatory approach, recognizing that both structuralist insights (emphasizing internal organization) and adaptationist insights (emphasizing ecological optimization) contribute to understanding evolutionary patterns [6]. Within this framework, developmental bias and constraint emerge as central explanatory concepts that help resolve apparent paradoxes in evolutionary biology, such as why certain morphological patterns remain stable across deep evolutionary timescales while others display remarkable diversification [7].

Mechanistic Foundations of Developmental Bias

Instructional and Self-Organizing Patterning Strategies

The mechanistic basis of developmental bias operates primarily through two patterning strategies that often combine in space and time: instructional patterning and self-organization [7]. Instructional patterning follows Wolpert's "French flag model," where cells acquire positional information from external sources such as morphogen gradients. These gradients create distinct developmental compartments through differentiation thresholds, establishing the fundamental axes and fields that guide subsequent pattern formation [7]. This strategy provides directionality and orientation to many periodic patterns along body axes, with positional signals often emanating from early axial structures like the neural tube or somites [7].

In contrast, self-organization generates pattern through intrinsic instabilities within initially homogeneous tissues. The Turing reaction-diffusion model represents the paradigmatic example, wherein short-range activators and long-range inhibitors spontaneously create periodic patterns without external guidance [7]. This mechanism excels at generating repetitive structures and explains how minimal parameter variations can produce significant pattern differences, contributing to evolutionary diversification [7]. Rather than operating exclusively, these strategies typically integrate during development, with instructional processes establishing broad positional coordinates that self-organizing processes then refine into specific patterns.

Table 1: Core Patterning Mechanisms in Developmental Evolution

| Mechanism | Fundamental Principle | Evolutionary Implication | Exemplary System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructional Patterning | Positional information from morphogen gradients establishes compartments | Constrains pattern orientation to body axes; provides developmental stability | Antero-posterior patterning in Drosophila by Bicoid gradient [7] |

| Self-Organization | Local activation and long-range inhibition spontaneously generate periodicity | Enables rapid evolutionary change through parameter modification; explains pattern diversity | Pigment stripe formation in zebrafish [7] |

| Integrated Patterning | Instructional cues seed self-organizing processes | Balances developmental stability with evolutionary flexibility | Somite segmentation in vertebrates [7] |

The Evo-Devo-Numerical Synthesis

Recent advances in evo-devo research have embraced what has been termed a "numerical evo-devo" synthesis, bridging developmental biology with mathematical modeling to understand pattern establishment [7]. This approach requires that mathematical models reproduce not only final pattern states but also the dynamics of their emergence and interspecies variation through minimal parameter changes [7]. This integrative methodology has been particularly fruitful in studies of pigment patterning, where Turing-type models successfully predict stripe orientation when incorporating initial axial information or tissue anisotropy [7].

The power of this synthetic approach lies in its ability to distinguish core developmental events from evolutionarily malleable parameters. For instance, research on poultry birds reveals that longitudinal bands of agouti expression foreshadowing dorsal stripes combine early instructive signals from somites (controlling absolute position) with later self-organization of pigment cells (controlling stripe width) [7]. Such findings demonstrate how developmental bias operates through hierarchical interactions across different temporal and spatial scales, with early instructional constraints biasing subsequent self-organizing processes toward specific evolutionary outcomes.

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Quantifying Developmental Bias Through Comparative Studies

Empirical investigation of developmental bias employs comparative approaches across multiple biological scales. At the genetic level, comparative transcriptomics identifies genes with differential expression patterns across species, revealing how developmental regulation evolves. For example, phylogenomic analysis of 20 plant species, including 14 gymnosperms, identified candidate ovule genes whose differential tissue expression patterns most influenced major evolutionary splits of seed plants [8]. Similarly, single-cell analyses of placental transcriptomes across species reveal the evolutionary divergence and crosstalk of maternal and fetal cell types during early mammalian evolution [8].

At the morphological level, statistical analyses of phenotypic covariation can reveal developmental biases that channel evolutionary change. Studies of limb proportions across hundreds of bird and bat species demonstrated that bird wing and leg proportions evolve independently, accommodating divergent ecological tasks, while bat limbs evolve in unison, potentially constraining their evolutionary capacity [8]. This contrast reflects the common development and function of bat forelimbs and hindlimbs within the membranous wing, creating a developmental bias that influences ecological adaptation [8].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Investigating Developmental Bias

| Methodology | Application | Technical Considerations | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenomic Analysis | Identifying genes with differential expression across taxa | Requires multiple sequenced genomes and transcriptomes; functional validation challenging | Developmentally regulated genes drive major evolutionary splits in seed plants [8] |

| Single-Cell Transcriptomics | Mapping cell-type evolution across species | Computational integration of datasets; identification of homologous cell populations | Conservation of striatal interneuron classes across placental mammals [8] |

| Mathematical Modeling | Testing patterning theories through in silico simulation | Multiple models may reproduce same pattern; parameters must reflect biological reality | Reaction-diffusion models recapitulate natural patterns with minimal parameter changes [7] |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Transcriptomic Profiling Tools: RNA sequencing, particularly single-cell RNA-seq, enables comprehensive characterization of gene expression patterns across species and developmental stages, allowing researchers to identify conserved and diverged regulatory programs [8]. These tools function to connect phylogenetic differences to developmental mechanisms.

CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing: Gene knockout and knock-in technologies permit functional testing of candidate genes in diverse organisms, including non-model species [9]. For example, CRISPR-mediated gene knock-in has been established in the hard coral Astrangia poculata, enabling direct tests of gene function in novel taxa [9].

Computational Modeling Platforms: Mathematical simulation environments (e.g., for implementing partial differential equations) allow researchers to test whether hypothesized mechanisms can generate observed biological patterns [7]. These platforms function to bridge theoretical predictions with empirical observations.

Tissue Clearing and 3D Imaging: Protocols like See-Star enable visualization of morphology and gene expression in opaque specimens by rendering tissues transparent while maintaining structural integrity [9]. These methods function to preserve three-dimensional relationships during developmental analysis.

Case Study: Developmental Constraints in Hominin Brain Evolution

A compelling illustration of developmental constraint operating in evolution comes from modeling of hominin brain expansion. Despite the brain's tripling in size over four million years of hominin evolution, mathematical modeling suggests this expansion may not have resulted primarily from direct selection for brain size itself [10]. Instead, the brain expansion appears to have been driven by its genetic correlation with developmentally late preovulatory ovarian follicles, which directly impact fertility [10].

This evolutionary outcome requires specific ecological conditions. The model indicates that hominin brain expansion occurs only when individuals experience both a challenging ecology (where brain-supported skills are needed to obtain energy) and seemingly cumulative culture (where learning has weakly diminishing returns) [10]. Under these conditions, brain size and follicle count become "mechanistically socio-genetically" correlated over development, creating a developmental constraint that diverts selection [10]. This case demonstrates how adaptive traits may evolve not through direct selection but through developmental constraints that channel evolutionary responses to selection on other traits.

The evo-devo dynamics framework used in this analysis separates the effects of selection and constraint for long-term evolution, showing that brain metabolic costs primarily affect mechanistic socio-genetic covariation rather than acting as direct fitness costs [10]. This approach provides a mathematical foundation for understanding how developmental constraints shape evolutionary trajectories across deep timescales.

Emerging Frontiers: Eco-Evo-Devo Integration

The field of evolutionary developmental biology is increasingly expanding into eco-evo-devo (ecological evolutionary developmental biology), which aims to understand how environmental cues, developmental mechanisms, and evolutionary processes interact across multiple scales [2]. This integrative framework explores causal relationships among developmental, ecological, and evolutionary levels, recognizing that environmental factors play instructive roles in shaping development and evolutionary potential [2].

Eco-evo-devo challenges the classic view that privileges genetics as the unique central factor in phenotypic evolution, instead emphasizing how developmental plasticity mediates environmental and evolutionary dynamics [2]. For example, experimental evolution studies in Drosophila melanogaster demonstrate that selection for cold tolerance reduces the plasticity of life-history traits under thermal stress, showing that development generates complex associations between environmental cues and phenotypic traits that themselves can evolve [2]. Similarly, studies of ontogenetic plasticity in the neotropical fish Astyanax lacustris reveal how temperature modulates developmental responses to different water flow regimes [2].

This ecological perspective reveals how environmental factors can modulate developmental biases, creating new evolutionary possibilities. The emerging eco-evo-devo synthesis thus provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding how developmental bias and constraint operate within ecological contexts to shape evolutionary trajectories across timescales.

Eco-Evo-Devo Causal Framework [2]

Developmental bias and constraint represent fundamental mechanisms shaping evolutionary trajectories by channeling phenotypic variation along non-random paths. The evo-devo synthesis has demonstrated that developmental processes not only constrain evolutionary possibilities but also actively facilitate adaptive evolution through modularity, integration, and the generation of covariation structures [6]. The emerging eco-evo-devo framework further expands this perspective by incorporating environmental factors as instructive agents in developmental and evolutionary processes [2].

Future research in this field will likely focus on several key frontiers: first, mechanistic studies of developmental-environmental interactions that reveal how environmental cues get incorporated into developmental programs; second, broadened focus on symbiotic development, recognizing that many developmental processes involve interactions with microbial partners; and third, integrative modeling across biological scales and taxa to identify general principles of evolvable developmental systems [2]. These approaches will continue to illuminate how developmental biases and constraints direct the course of evolution, ultimately contributing to a more comprehensive theory of biological innovation that integrates developmental, ecological, and evolutionary perspectives.

Evo-Devo Research Methodology [7]

Symbiosis and Inter-kingdom Communication in Development

Ecological Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Eco-Evo-Devo) has emerged as an integrative discipline that seeks to understand how environmental cues, developmental mechanisms, and evolutionary processes interact to shape phenotypes and biodiversity across multiple scales [3]. Within this framework, a fundamental paradigm shift has occurred: the recognition that multicellular organisms are not biological individuals but holobionts—consortia of a host organism plus numerous species of other symbiotic organisms [11]. The developing organism is now understood as a multi-genomic entity, whose anatomy, physiology, immunity, and evolution are performed in concert with symbiotic partners [11]. This perspective reframes development as a sympoietic process (the creation of an entity through the interactions of other entities) based on multigenomic interactions between zygote-derived cells and symbiotic microbes [11]. Rather than being the read-out of a single genome, development involves continuous communication and metabolic integration across kingdoms of life, facilitating the formation of organs, biofilms, and entire organisms through collaborative interactions where each domain acts as the environment for the other [11].

Table: Key Concepts in Symbiotic Development

| Concept | Definition | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Holobiont | An integrated consortium of a host organism plus numerous species of symbiotic organisms | Reframes the "individual" as a multi-species collective; challenges traditional biological individualism [11] |

| Sympoiesis | The development of symbiotic relationships that form holobionts; creation through interaction | Explains how organs and biofilms form through collaborative interactions across life domains [11] |

| Developmental Symbiosis | The process whereby symbionts are necessary for normal host development | Generates selectable variation, provides mechanisms for reproductive isolation, facilitates evolutionary transitions [12] |

| Co-metabolism | Metabolic pathways shared between host and symbionts where products of one are substrates for the other | Creates entangled metabolism; food and signals are processed through both host and microbial enzymes [11] |

Mechanisms of Inter-kingdom Communication in Development

Molecular Dialogues in Symbiotic Systems

Inter-kingdom communication is predicated on the ability of cells from different kingdoms of life (e.g., bacteria and animals) to communicate through chemical signals that are interpreted in a manner that facilitates development [11]. These molecular dialogues often involve the recognition of microbial products by host receptors, leading to developmental outcomes. For instance, in mammals, gut microbes convert dietary tryptophan into indole, which circulates through the blood and enters the hippocampus, where it activates aryl hydrocarbon receptors on neural stem cells [11]. This activation converts the receptor into a functional transcription factor that activates genes responsible for generating neurons essential for memory and learning [11]. Similarly, bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids that induce intestinal cells to synthesize and secrete the hormone serotonin, which promotes the maturation of immature neurons in the esophagus and allows efficient peristalsis [11].

The evolutionary origins of these communication systems are deep. Mukherjee and Moroz traced the evolution of G-type lysozymes across Metazoa, revealing how these enzymes have been spread by horizontal gene transfer across kingdoms and repeatedly adapted for immune and digestive functions in response to ecological contexts [3]. This demonstrates how communication molecules can be repurposed across evolutionary timescales to facilitate new developmental partnerships.

Table: Quantified Effects of Microbial Disruption on Developmental Outcomes

| Experimental Model | Intervention | Developmental Deficit | Molecular Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murine model | Depletion of gut microbiota | Reduced neurogenesis in hippocampus; impaired memory and learning | Decreased conversion of tryptophan to indole, leading to reduced aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation [11] |

| Mouse neonates | Germ-free conditions | Immature gut neurons; impaired peristalsis | Reduced bacterial production of short-chain fatty acids, leading to decreased serotonin synthesis [11] |

| Drosophila melanogaster | Removal of Wolbachia symbionts | Increased viral susceptibility; reduced fecundity | Loss of bacterial-mediated immune priming; altered oocyte development [12] [11] |

Signaling Pathways in Developmental Symbiosis

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathway in bacterial-mediated neurogenesis:

Figure 1. Bacterial-mediated neurogenesis pathway in mammals. This pathway demonstrates inter-kingdom communication where gut microbial metabolism influences brain development through circulating metabolites.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Inter-kingdom Communication

Approaches for Identifying and Characterizing Symbiotic Partnerships

Research in developmental symbiosis employs integrated methodologies to identify symbiotic partners, characterize communication mechanisms, and manipulate associations to determine functional outcomes. The following experimental workflow outlines a comprehensive approach:

Figure 2. Experimental workflow for identifying and characterizing developmental symbionts. This integrated approach identifies symbiotic partners and determines their functional roles across host development.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Developmental Symbiosis

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Systems | Maintenance of organisms with known microbial compositions | Determining necessity of specific symbionts for normal development; identifying developmental phenotypes in germ-free animals [11] |

| Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) | Visualizing spatial localization of specific microbial taxa within host tissues | Tracking transmission of symbionts during embryonic development; determining tissue-specific colonization patterns [11] |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing | Taxonomic profiling of microbial communities across host developmental stages | Identifying which symbionts are present at specific developmental timepoints; correlating community shifts with developmental transitions [3] |

| Metabolomic Profiling | Comprehensive identification of small molecules in host-symbiont systems | Discovering signaling molecules (e.g., indole, short-chain fatty acids) that mediate inter-kingdom communication [11] |

| GFP-tagged Bacterial Strains | Visualizing and tracking specific bacterial lineages in vivo | Studying transmission routes (e.g., maternal transmission to offspring); quantifying bacterial proliferation during host development [11] |

Evolutionary and Therapeutic Implications

Evolutionary Consequences of Developmental Symbiosis

From an evolutionary developmental biology perspective, symbiotic relationships generate selectable variation and influence evolutionary trajectories through multiple mechanisms. Developmental symbiosis can generate particular organs, produce selectable genetic variation, provide mechanisms for reproductive isolation, and facilitate major evolutionary transitions [12]. The transmission of symbionts across generations occurs through several mechanisms: (1) intra-organismal transmission (via vegetative reproduction, oocytes, or embryos); (2) intimate neighborhood transmission (where parents provide symbionts as resources at birth); and (3) horizontal transmission (where offspring inherit means to select symbionts from the environment) [11]. For example, in Drosophila, Wolbachia bacteria become concentrated in the posterior pole of the embryo and are transported into the oocyte, ensuring transmission to the next generation [11].

These symbiotic relationships can evolve into obligate dependencies, as illustrated by the complex metabolic integration in the mealy bug Planococcus:

Figure 3. Metabolic integration in Planococcus holobiont. This illustrates the sympoietic production of essential amino acids through multi-species metabolic collaboration.

Implications for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

The holobiont model has profound implications for biomedical research and drug development. Understanding that physiological systems are shaped by microbial partners suggests novel therapeutic approaches that target these symbiotic relationships rather than just human pathways [11]. For drug development professionals, this perspective highlights that:

Pharmacomicrobiomics: The microbiome significantly influences drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity, necessitating consideration of microbial communities in therapeutic development.

Microbiota-Based Interventions: Developmental disorders with previously unknown etiology may involve disrupted symbiotic relationships, suggesting potential for microbiota-targeted therapies.

Personalized Medicine: Inter-individual variation in symbiotic communities may explain differential treatment responses and suggest personalized approaches based on microbiome profiling.

The eco-evo-devo framework emphasizes that many diseases may result from discordance between our evolved holobiont biology and modern environmental conditions that disrupt essential symbiotic relationships [3] [11]. This provides an integrative approach for investigating dynamic host-microbe interactions throughout development and their implications for health and disease.

The Developmental Origins of Evolutionary Novelty and Innovation

The explanation of evolutionary novelty—the emergence of new, adaptive structures and functions that expand an organism's ecological opportunities—represents a core objective of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo). A successful explanatory framework requires the integration of different biological disciplines, yet the relationships between developmental biology and standard evolutionary biology remain contested, as does the precise definition of novelty itself [13]. Evolutionary novelty is not merely the modification of existing traits but often involves the origin of qualitatively new characteristics, such as the neural crest in vertebrates or the transformation of the pectoral fin in Panderichthys toward digit formation [13]. Historically, the field of evo-devo emerged from evolutionary embryology, with its roots in the 19th century, but it has now solidified into a distinct discipline with its own research programs, societies, and journals [14].

This whitepaper examines the developmental origins of evolutionary novelty and innovation through the lens of the evo-devo synthesis. We explore the core conceptual frameworks, including the roles of developmental bias, plasticity, and mechanistic patterning theories, and provide a practical toolkit for researchers investigating the genetic, cellular, and biophysical basis of innovation. The integration of evo-devo with ecology (eco-evo-devo) further refines our understanding by considering how environmental cues interact with developmental mechanisms and evolutionary processes across multiple scales [2]. By synthesizing historical perspectives with recent quantitative and modeling approaches, this guide aims to equip scientists with the theoretical foundations and experimental methodologies needed to decipher one of biology's most compelling phenomena.

Conceptual Framework: Mechanisms Generating Novelty

Definitions and Historical Context

Evolutionary novelty has been defined and redefined throughout the history of evolutionary biology. Ernst Mayr, in 1960, considered the emergence of evolutionary novelties as a core challenge, focusing on the origin of new structures. Contemporary workshops continue to debate the precise boundaries of the concept, indicating that a universally accepted definition remains elusive [13]. A central distinction exists between innovation—the initial appearance of a novel trait—and its subsequent radiation into diverse forms through adaptation. This distinction is critical for designing research programs that target origination events rather than later modifications [13].

The intellectual heritage of evo-devo traces back to the late 19th century, when embryology was considered central to understanding evolution. As William Bateson noted, "Morphology was studied because it was the material believed to be the most favorable for the elucidation of the problems of evolution, and we all thought that in embryology the quintessence of morphological truth was most palpatically presented" [14]. The field declined with the rise of Mendelian genetics and population biology in the early 20th century, which treated development as a "black box" between genotype and phenotype. The resurgence began with Stephen J. Gould's 1977 book Ontogeny and Phylogeny, which revived interest in the relationship between development and evolution [14].

Core Mechanistic Theories

Two primary mechanistic theories explain how novel patterns and structures form during development: instructive signaling and self-organization. The instructional patterning paradigm, exemplified by Lewis Wolpert's 1969 "French flag model," posits that cells acquire positional information from external sources, such as morphogen gradients, which dictate cell fate in a concentration-dependent manner [15]. This theory effectively explains pattern orientation along body axes, as seen in the antero-posterior patterning of the Drosophila embryo by Bicoid mRNA gradients [15].

In contrast, self-organization theories, most famously Alan Turing's 1952 reaction-diffusion model, propose that intrinsic instabilities within initially homogeneous tissues spontaneously generate pattern through local activation and long-range inhibition [15]. Turing models are particularly effective at explaining periodic patterns, such as stripes and spots, and their parameters can be easily modified to produce substantial pattern variation, providing a plausible mechanism for rapid evolutionary change [15].

Contemporary research has largely moved beyond the opposition of these theories, recognizing that most complex patterns arise from a combination of instructional cues and self-organizing dynamics in space and time [15]. For example, the longitudinal stripes in juvenile poultry birds are controlled by both early instructive signals from the somite that establish positional information and later self-organization of pigment cells that determines stripe width [15].

Table 1: Core Concepts in the Origins of Evolutionary Novelty

| Concept | Definition | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Novelty | Emergence of new, adaptive structures/functions not present in ancestors | Core challenge in evolutionary biology; requires interdisciplinary explanation [13] |

| Developmental Bias/Constraint | Non-random phenotypic variation generated by developmental systems architecture | Explains why evolution follows certain pathways; influences adaptive radiations [2] |

| Developmental Plasticity | Capacity of a genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to environmental conditions | Provides raw material for genetic assimilation; mediates eco-evo-devo interactions [2] |

| Instructive Patterning | Pattern formation guided by external positional information (e.g., morphogen gradients) | Explains pattern orientation and reproducibility along body axes [15] |

| Self-Organization | Pattern emergence from intrinsic tissue instabilities without external guidance | Explains periodicity and diversity of natural patterns; mathematically tractable [15] |

| Mechanistic Socio-Genetic Covariation | Covariation generated through developmental mechanisms including social interactions | Explains correlated evolution of traits not directly selected for (e.g., brain size) [10] |

Quantitative Evo-Devo: Mathematical Frameworks and Data

Mathematical Integration of Development and Evolution

A significant advancement in evo-devo has been the development of mathematical frameworks that integrate evolutionary and developmental (evo-devo) dynamics. Traditional evolutionary models often assumed equilibrium and treated development as a black box, but recent approaches explicitly model phenotypic construction throughout life [10]. The evo-devo dynamics framework allows for modeling the simultaneous dynamics of evolution and development, assuming clonal reproduction and rare, weak, unbiased mutation [10]. This framework separates the effects of selection from constraint in long-term evolution without assuming negligible genetic evolution, enabling causal analysis of the roles of each.

For example, applying this framework to hominin brain expansion has revealed that the tripling of brain size over four million years may not have been caused primarily by direct selection for brain size itself, but rather by its mechanistic socio-genetic correlation with developmentally late preovulatory ovarian follicles [10]. This correlation emerges over development when individuals experience a challenging ecology and seemingly cumulative culture. The model successfully recovers the evolution of brain and body sizes of seven hominin species and major patterns of human development, demonstrating the power of this integrative approach [10].

Numerical Evo-Devo Synthesis for Pattern Formation

The integration of developmental biology with mathematics has created a powerful "numerical evo-devo" synthesis for identifying pattern-forming factors [15]. This approach combines empirical data from model and non-model organisms with mathematical modeling using partial differential equations (PDEs) that describe spatio-temporal dynamics. The synthesis requires that mathematical models reproduce not only final pattern states but also the developmental dynamics of their emergence and the extent of inter-species variation achievable through minimal parameter changes [15].

This integrative approach helps disentangle molecular, cellular, and mechanical interactions during pattern establishment. For instance, Turing models can recover the longitudinal orientation of fish stripes when simulated with non-homogeneous axial initial conditions or when modulated by production/degradation gradients, effectively combining self-organization with instructional cues [15].

Table 2: Key Parameters in Evo-Devo Dynamics of Hominin Brain Expansion

| Parameter | Role in Model | Effect on Brain Size Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Extraction Time Budget (EETB) | Proportion of different challenge types faced (ecological, cooperative, competitive) | Determines cognitive demands; challenging ecology promotes brain expansion [10] |

| Energy Extraction Efficiency (EEE) Shape | How efficiency changes with skill level (diminishing returns) | Weakly diminishing returns (from cumulative culture) enable human-sized brains [10] |

| Brain Metabolic Costs | Energy requirements of brain tissue per kilogram | Key constraint; empirically estimated; prevents evolution of excessively large brains [10] |

| Mechanistic Socio-Genetic Covariation | Covariation between brain size and follicle count generated through development | Directs selection on follicle count to drive brain expansion as correlated response [10] |

| Social Development | Cooperation/competition for energy extraction affecting development | Affects developmental trajectories and resulting genetic correlations [10] |

Experimental Approaches and Protocols

Methodology for Evo-Devo Pattern Formation Studies

Research in evolutionary novelty employs a diverse methodological toolkit that integrates comparative biology, developmental genetics, and mathematical modeling. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for identifying pattern-forming factors:

Selection of Study System: Choose organisms based on specific criteria:

- Model organisms (e.g., Drosophila, zebrafish) for genetic tractability and established tools [15]

- Non-model organisms with natural pattern variations for comparative studies (e.g., cichlid fish, striped mice) [15]

- Consider technical feasibility for functional tests and relevance to evolutionary questions

Characterization of Pattern Development:

- Document ontogenetic progression using high-resolution imaging

- Quantify pattern attributes: periodicity, orientation, geometry, and stability [15]

- Analyze cellular basis (e.g., pigment cell distribution, skeletal element formation)

Candidate Factor Identification:

- Perform comparative transcriptomics/proteomics between species/variants

- Analyze expression patterns of developmental genes and morphogens [15]

- Use quantitative genetics in natural populations to identify genomic regions

Functional Validation:

- Implement gene manipulation (CRISPR/Cas9, RNAi) in model organisms

- Conduct tissue grafting/transplantation experiments

- Modulate biophysical parameters (e.g., cell density, tissue tension)

Mathematical Modeling:

- Develop PDEs describing spatio-temporal dynamics

- Simulate pattern formation using candidate parameters

- Test model predictions through experimental perturbations [15]

Integration and Iteration:

- Compare empirical results with model predictions

- Refine models based on experimental data

- Identify minimal parameter changes that recapture evolutionary variation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evo-Devo Innovation Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function in Evo-Devo Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing | Targeted genome modification in model and non-model organisms | Testing gene function in pattern formation; creating mutant lines [15] |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) | Transient gene knockdown | Functional testing without stable genetic modification [15] |

| Comparative Transcriptomics | Genome-wide expression profiling across species/tissues | Identifying candidate genes involved in novelty formation [15] |

| Lineage Tracing Markers | Tracking cell fate and migration during development | Neural crest migration studies; cell origin of novel structures [13] |

| Morphogen Gradient Probes | Visualizing concentration gradients of signaling molecules | Testing instructional patterning models; quantifying positional information [15] |

| Partial Differential Equation Modeling | Mathematical simulation of pattern formation dynamics | Testing Turing mechanisms; predicting effects of parameter variation [15] |

| Tissue Recombinants/Explants | Isolating tissue interactions | Separating tissue-autonomous from inductive effects [15] |

Visualization of Evo-Devo Workflows and Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Pattern Formation Analysis

Integrated Patterning Mechanisms

Evo-Devo Dynamics Framework

Future Directions and Research Applications

The integration of evo-devo with ecology (eco-evo-devo) represents one of the most promising frontiers for understanding evolutionary novelty. This expanded framework aims to understand how environmental cues, developmental mechanisms, and evolutionary processes interact to shape phenotypes, morphogenetic patterns, life histories, and biodiversity across multiple scales [2]. Rather than serving as a loose aggregation of diverse research topics, eco-evo-devo seeks to provide a coherent conceptual framework for exploring causal relationships among developmental, ecological, and evolutionary levels [2]. This approach recognizes that developmental processes themselves can be shaped by inter-organismal interactions such as symbiosis and inter-kingdom communication, reframing development as a symbiotic process where organismal identity emerges through interactions with microbial and environmental partners [2].

For biomedical researchers and drug development professionals, the evo-devo perspective offers valuable insights into the developmental origins of disease and potential therapeutic strategies. By understanding how developmental constraints and biases shape evolutionary trajectories, researchers can better predict vulnerability to certain pathological conditions. The mathematical frameworks developed for modeling pattern formation may also inform tissue engineering and regenerative medicine approaches by revealing how to guide self-organizing processes toward functional tissue architectures.

Future research should prioritize multi-scale integration, combining molecular, cellular, tissue, organismal, and population-level analyses with mathematical modeling that captures the essential dynamics of development and evolution. The establishment of more non-model organisms as study systems will be crucial for capturing the full spectrum of evolutionary innovation, while advances in single-cell technologies will enable unprecedented resolution of developmental processes. Through this integrated approach, evo-devo continues to transform our understanding of how novelty emerges in evolution and how we might harness these principles for scientific and medical advancement.

Understanding how genetic variation translates into observable phenotypic diversity represents a fundamental challenge in modern biology. The field of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) has emerged as a synthetic discipline that aims to bridge this gap by examining how developmental processes shape evolutionary change across multiple biological scales. Multi-scale causation refers to the complex causal relationships operating across genetic, cellular, tissue, organismal, and ecological levels that collectively generate biological form and function [16]. Rather than viewing phenotypes as direct products of genetic blueprints, this framework recognizes that phenotypes emerge from dynamic interactions within and between these hierarchical levels, with influences flowing bidirectionally from genes to environment and back again [17].

The eco-evo-devo perspective, which integrates ecological context with evolutionary developmental approaches, provides a coherent conceptual framework for exploring these causal relationships [16]. This integrated viewpoint challenges the classic gene-centric view of evolution by demonstrating how environmental cues actively participate in shaping developmental trajectories and evolutionary outcomes [16]. By examining the mechanistic links between genotype and phenotype across biological hierarchies, researchers can decipher the fundamental principles governing morphological diversity, life history evolution, and adaptive responses to changing environments—knowledge with significant implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development [18] [19].

Theoretical Foundations: From Evo-Devo to Multi-scale Causation

Historical Development and Key Concepts

The conceptual roots of multi-scale causation extend back to early embryological studies, but have been profoundly transformed by molecular genetics and systems biology. Evolutionary developmental biology represents the synthesis of two traditionally separate disciplines: evolutionary biology, concerned with population-level changes over generational timescales, and developmental biology, focused on organismal changes over ontogenetic timescales [20]. This synthesis emerged from the recognition that development serves as the crucial intermediary process that translates genetic variation into phenotypic variation upon which natural selection acts [20].

Key historical milestones include Conrad Waddington's concepts of canalization and genetic assimilation, which described how developmental pathways buffer against perturbations and how environmentally induced phenotypes can become genetically fixed over evolutionary time [20]. Later, Lewis Wolpert's French flag model of positional information illustrated how morphogen gradients could provide instructional cues for pattern formation during development [20]. Most recently, the recognition of developmental plasticity—the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to environmental conditions—has further emphasized the complex, non-linear nature of genotype-phenotype relationships [16] [17].

The Eco-Evo-Devo Synthesis

The contemporary framework of ecological evolutionary developmental biology (eco-evo-devo) expands this paradigm by explicitly incorporating ecological factors as essential components of multi-scale causation [16]. This perspective recognizes that environmental cues not only select for existing variation but actively participate in directing developmental outcomes, thereby shaping the phenotypic variation upon which selection acts [16]. Rather than serving as a passive backdrop for evolution, environments provide instructive signals that influence gene regulatory networks, cellular behavior, and tissue-level organization throughout ontogeny [16] [17].

This integrated framework reveals that organisms are not merely passive products of their genes and environment, but active participants in their own development and evolution through processes of niche construction and developmental plasticity [17]. The resulting multi-scale causal network operates through a complex interplay of top-down, bottom-up, and same-level influences that collectively drive evolutionary innovation and diversification [16].

Biological Mechanisms of Multi-scale Integration

Gene Regulatory Networks and Developmental Programs

At the molecular level, gene regulatory networks (GRNs) represent fundamental architectures that integrate genetic information across biological scales. These networks consist of transcription factors, signaling pathways, and regulatory DNA elements that collectively control spatial and temporal gene expression patterns during development [18]. The structure of GRNs explains how relatively simple genetic changes can produce substantial phenotypic effects through alterations to network architecture or dynamics [18] [15].

Research in zebrafish has revealed that GRNs operate not only during embryonic development but also in adult contexts such as tissue regeneration, demonstrating how conserved regulatory programs can be repurposed across different biological contexts [18]. For example, overlapping GRNs guide both developmental neurogenesis and injury-induced regeneration in the zebrafish retina, illustrating how multi-scale regulatory logic enables complex phenotypic responses [18]. The modular organization of GRNs facilitates evolutionary tinkering, as individual network components can be modified without disrupting overall system functionality, thereby enabling evolutionary innovation while maintaining developmental stability.

Cellular Competency and Agential Materials

A revolutionary insight into multi-scale causation comes from recognizing the problem-solving competencies of cellular systems. Rather than being passive building blocks following genetic instructions, cells exhibit sophisticated collective intelligence derived from their unicellular ancestry [17]. These agential materials possess capabilities for behavioral plasticity, decision-making, and problem-solving that emerge at cellular and tissue levels [17].

This perspective reconceptualizes morphogenesis as a goal-directed process where cellular collectives work to achieve specific anatomical outcomes despite perturbations. Levin describes this as "the collective intelligence of cells during morphogenesis," which significantly influences evolutionary dynamics by providing a responsive substrate upon which selection acts [17]. This cellular agency operates across multiple scales, from individual cell behaviors to tissue-level patterning, and enables robust developmental outcomes through distributed decision-making rather than centralized genetic control [17].

Pattern Formation Mechanisms

The emergence of complex morphological patterns from initially homogeneous tissues illustrates fundamental principles of multi-scale causation. Two primary mechanisms—instructional patterning and self-organization—operate across scales to generate biological form [15].

Instructional patterning, exemplified by Wolpert's French flag model, involves positional information provided by morphogen gradients that instruct cells to adopt specific fates based on their location [15]. This mechanism provides directional cues that orient patterns with respect to body axes. In contrast, self-organization occurs through local interactions between cellular components that spontaneously generate spatial patterns without external guidance. Alan Turing's reaction-diffusion model represents a classic self-organization mechanism, where interacting activators and inhibitors produce periodic patterns [15].

Contemporary research reveals that most biological patterns emerge through integrated deployment of both mechanisms across developmental time [15]. For example, the longitudinal stripes in poultry birds involve early instructional signals from somites that establish general pattern domains, followed by self-organizing processes among pigment cells that refine stripe width and periodicity [15]. This hierarchical integration of patterning mechanisms across temporal and spatial scales exemplifies the principles of multi-scale causation in action.

Table 1: Key Pattern Formation Mechanisms and Their Characteristics

| Mechanism | Key Principles | Representative Models | Biological Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructional Patterning | Positional information, morphogen gradients, threshold responses | French flag model | Drosophila segment polarity, vertebrate limb patterning |

| Self-Organization | Local interactions, reaction-diffusion, emergent patterns | Turing patterns | Zebrafish stripes, hair follicle spacing, digit formation |

| Integrated Systems | Hierarchical control, sequential patterning, multi-scale integration | Progressive boundary formation | Bird plumage patterns, tooth positioning, brain arealization |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Model Organisms in Multi-scale Research

Model organisms provide powerful experimental systems for dissecting multi-scale causal relationships due to their genetic tractability, well-characterized development, and relevance to broader evolutionary questions. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) exemplifies an ideal model for multi-scale research, combining genetic accessibility with optical transparency that enables direct observation of developmental processes in real time [18]. As a teleost fish, zebrafish occupy an informative evolutionary position, sharing over 70% of their genes with humans while exhibiting distinctive morphological features that illuminate vertebrate diversification [18].

Zebrafish offer particular advantages for studying multi-scale causation due to several characteristics. Their external development and embryonic transparency permit direct visualization of tissue patterning, cell migration, and organogenesis without invasive procedures [18]. The whole-genome duplication event in teleost evolution provides unique opportunities to study gene subfunctionalization and the evolution of novel developmental programs [18]. Additionally, their rapid generation time and high fecundity enable large-scale genetic screens and quantitative analysis of phenotypic variation across individuals and populations [18].

Quantitative Imaging and Morphometric Analysis

Advanced imaging technologies enable researchers to capture dynamic developmental processes across spatial and temporal scales. Light-sheet microscopy of zebrafish embryos, for instance, allows continuous observation of morphogenetic movements throughout embryogenesis without phototoxicity [18]. These approaches generate quantitative data on cell behaviors, tissue dynamics, and pattern formation that can be correlated with molecular manipulations.

Computational analysis of resulting image data employs morphometrics—quantitative descriptors of biological form—to characterize phenotypic outcomes across experimental conditions [15]. Geometric morphometrics can capture subtle shape variations, while network analysis approaches can quantify complex pattern features such as periodicity, orientation, and symmetry [15]. These quantitative descriptors facilitate statistical comparison between genotypes, environmental conditions, or evolutionary lineages, thereby linking manipulations across scales to phenotypic outcomes.

Perturbation Experiments Across Scales

A powerful approach for establishing causal relationships in multi-scale systems involves targeted perturbations at one level followed by comprehensive analysis of effects across multiple scales. These experimental strategies include:

- Genetic perturbations: CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, morpholino knockdown, and transgenic approaches that alter specific genetic elements while monitoring effects on molecular networks, cellular behaviors, and tissue-level phenotypes [18].

- Environmental manipulations: Controlled alteration of environmental conditions (temperature, nutrient availability, mechanical stress) to assess effects on developmental plasticity and reaction norm evolution [16].

- Surgical and physical interventions: Microsurgical tissue manipulations, barrier implantation, and mechanical compression to test physical aspects of morphogenesis and regeneration [17].

- Pharmacological treatments: Small molecule inhibitors and activators that target specific signaling pathways to dissect their contributions to multi-scale processes [18].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Studying Multi-scale Causation

| Approach | Methodology | Scale of Intervention | Readouts Across Scales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Screens | Mutagenesis, CRISPR-Cas9, RNAi | Genetic | Molecular: gene expression; Cellular: behaviors; Tissue: morphology; Organismal: viability |

| Experimental Evolution | Controlled selection regimes | Population | Generational changes in developmental trajectories, reaction norms, and molecular networks |

| Transplantation assays | Tissue grafting, cell transplantation | Tissue/Cellular | Cell fate decisions, tissue integration, signaling interactions, pattern remodeling |

| Environmental Manipulation | Controlled environmental variation | Environmental/Organismal | Phenotypic plasticity, gene expression changes, physiological adaptation, fitness consequences |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mediators

Several evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways repeatedly function as key mediators in multi-scale causation, translating between genetic, cellular, and tissue-level information. These pathways include:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling: This pathway regulates numerous developmental processes including cell fate specification, proliferation, and tissue patterning. Research in zebrafish demonstrates how Wnt signaling guides both developmental neurogenesis and injury-induced regeneration, illustrating how conserved pathways operate across different temporal contexts and biological scales [18]. Pharmacological inhibition of Wnt signaling using compounds like Erlotinib disrupts pattern formation and regeneration, confirming its essential role in these multi-scale processes [18].

Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) signaling: FGF pathways mediate epithelial-mesenchymal interactions, tissue growth, and pattern refinement across numerous developmental contexts. Studies of limb development reveal how FGF signaling interacts with Wnt pathways to coordinate growth with cell fate specification, demonstrating how signaling integration across scales generates coordinated morphological outcomes [18].

Notch signaling: This pathway mediates cell-cell communication and fate decisions through lateral inhibition mechanisms. Notch signaling exemplifies how local cellular interactions generate larger-scale patterns through self-organizing principles, particularly in neurogenesis and segmentation processes [18].

Hedgehog signaling: This morphogen pathway contributes to tissue patterning, particularly in neural and skeletal systems. Research on cichlid fish craniofacial diversity demonstrates how Hedgehog signaling variations underlie adaptive morphological differences, showing how evolutionary changes in developmental pathways produce functional phenotypic variation [21].

Signaling Pathway Logic: Conserved molecular pathways translate extracellular signals into transcriptional responses

Research Protocols and Methodological Framework

Protocol: Analyzing Gene Expression Patterns Across Developmental Trajectories

This protocol outlines methods for quantifying gene expression dynamics across developmental stages and relating them to phenotypic outcomes, using zebrafish as a model system.

Materials and Reagents:

- Zebrafish embryos at desired developmental stages

- RNA extraction reagents (TRIzol, chloroform, isopropanol)

- cDNA synthesis kit

- Quantitative PCR reagents and primers

- Whole-mount in situ hybridization reagents (digoxigenin-labeled probes, anti-digoxigenin antibodies, staining substrate)

- Confocal microscopy equipment

- Image analysis software (ImageJ, Fiji, or specialized morphometrics platforms)

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect zebrafish embryos at precise developmental stages (e.g., 6, 12, 24, 48 hours post-fertilization) and stabilize RNA/protein immediately.

- Spatial Expression Analysis: Perform whole-mount in situ hybridization for target genes using digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes to visualize expression patterns.

- Quantitative Expression Analysis: Extract RNA from pooled embryos, synthesize cDNA, and perform quantitative PCR to measure expression levels of target genes across development.

- Imaging and Reconstruction: Capture high-resolution images of stained embryos using confocal microscopy, then reconstruct three-dimensional expression patterns using volume rendering software.

- Pattern Quantification: Use image analysis software to quantify expression domain boundaries, intensity gradients, and spatial relationships to morphological landmarks.

- Correlation with Phenotype: Compare expression patterns across genetic variants or environmental conditions to identify correlations with specific phenotypic outcomes.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For weak in situ signals, increase probe concentration or staining duration

- For quantitative comparisons across stages, include internal reference standards

- For pattern analysis, ensure consistent embryo orientation during imaging

Protocol: Assessing Phenotypic Plasticity Across Environmental Gradients

This protocol describes approaches for quantifying reaction norms—the pattern of phenotypic expression across environmental gradients—to understand multi-scale responses to environmental variation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Genetically defined model organism stocks (Drosophila, zebrafish, or other suitable species)

- Environmental control chambers (temperature, humidity, light cycles)

- Controlled nutrition media

- Morphometric analysis equipment (microscopes, calipers, imaging systems)

- Data analysis software with mixed-effects modeling capabilities

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Establish environmental gradients (e.g., temperature: 18°C, 22°C, 26°C, 30°C) with adequate replication within each genotype.

- Rearing Conditions: Raise individuals from each genetic line across all environmental conditions, controlling for density and randomizing positions within environmental chambers.

- Phenotypic Assessment: Measure target phenotypes (morphological, physiological, life history) at appropriate developmental stages using standardized protocols.

- Data Collection: Record multiple phenotypic traits for each individual along with environmental treatment and genetic identity.

- Reaction Norm Analysis: Fit statistical models (linear mixed effects, polynomial regression) to describe phenotypic responses across environments for each genotype.

- Genetic Variation Analysis: Quantify genetic variation in reaction norm shape (genotype × environment interactions) using variance component analysis.

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Parallel reaction norms indicate no genotype × environment interaction

- Crossing reaction norms indicate genetic variation in environmental sensitivity

- Nonlinear patterns suggest threshold responses or complex environmental modulation

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-scale Causation Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Scale of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms | Zebrafish (Danio rerio), Drosophila (D. melanogaster), Stickleback fish | Comparative developmental studies, genetic screens, evolutionary analyses | Genetic to organismal |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, morpholinos, transgenic reporter lines | Gene function analysis, lineage tracing, live imaging of development | Molecular to tissue |

| Imaging Systems | Confocal microscopy, light-sheet microscopy, micro-CT scanning | Live imaging of development, 3D reconstruction, quantitative morphometrics | Cellular to organismal |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Gene regulatory network modeling, phylogenetic comparative methods | Network analysis, evolutionary inference, pattern quantification | Molecular to evolutionary |

| Environmental Chambers | Temperature-controlled incubators, photoperiod control systems | Reaction norm analysis, developmental plasticity studies | Environmental to phenotypic |

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Mathematical modeling provides essential tools for integrating data across biological scales and testing hypotheses about multi-scale causal relationships. Computational approaches in evo-devo include:

Gene Regulatory Network Modeling: Boolean networks, ordinary differential equations, and stochastic models that simulate the dynamics of genetic interactions and their effects on pattern formation [15]. These models can predict how perturbations to network architecture alter developmental outcomes and evolutionary potential.

Turing Pattern Simulations: Partial differential equation systems that implement reaction-diffusion mechanisms to explore how simple molecular interactions can generate complex biological patterns [15]. Parameters in these models can be systematically varied to determine how evolutionary changes affect pattern characteristics such as periodicity, orientation, and stability.

Mechanical Models: Finite element analysis and vertex models that simulate physical interactions between cells and tissues during morphogenesis [17]. These approaches recognize that mechanical forces represent crucial mediators in multi-scale causation, translating molecular signals into tissue-level deformations and patterns.

Multi-scale Integrative Frameworks: Emerging computational approaches that explicitly link models across biological hierarchies, connecting genetic variation to cellular behaviors to tissue-level phenotypes [15]. These frameworks enable researchers to test how perturbations at one level propagate through the system to produce emergent properties at higher levels.

Experimental Workflow: Iterative approach for investigating multi-scale causation

Applications and Future Directions

Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications