Early Burst vs. Late Burst Models: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Early Burst and Late Burst models, contrasting their theoretical foundations, methodological applications, and relevance in evolutionary biology and drug development.

Early Burst vs. Late Burst Models: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Early Burst and Late Burst models, contrasting their theoretical foundations, methodological applications, and relevance in evolutionary biology and drug development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores how these models explain patterns of rapid evolution and the critical challenge of controlling initial drug release in long-acting injectables. By integrating perspectives from phylogenetic comparative methods and pharmaceutical sciences, the content offers a framework for troubleshooting model fit, optimizing development strategies, and validating findings through comparative analysis to inform both basic research and clinical translation.

Understanding the Core Concepts: From Adaptive Radiation to Drug Release Kinetics

The study of evolutionary and ecological dynamics has long been characterized by debates surrounding the tempo and mode of change. Central to this discourse is the contrast between "early burst" and "late burst" models, which describe fundamentally different patterns of diversification and trait evolution. Early burst models, also known as punctuated equilibrium or saltative branching, propose that evolutionary rates peak early during lineage diversification events followed by exponential decay, rather than remaining constant over time. This framework challenges traditional models of gradualism that assume steady, incremental change and provides a powerful lens for understanding patterns observed across biological systems, from molecular evolution to morphological diversification.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of early burst models against alternative frameworks, examining their theoretical foundations, empirical support, and analytical methodologies. We focus specifically on the phenomenon of exponential rate decay as a unifying principle across biological scales, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to apply these models in evolutionary and ecological research.

Conceptual Framework: Early Burst Versus Late Burst Models

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Early Burst and Late Burst Models

| Feature | Early Burst Models | Late Burst Models | Gradualist Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary tempo | Rapid change followed by exponential decay | Accelerated change late in diversification | Constant, incremental change |

| Peak activity period | Immediately following lineage splitting | Long after lineage establishment | Uniform throughout lineage history |

| Mathematical pattern | Exponential decay of evolutionary rates | Exponential increase of evolutionary rates | Linear or constant rate of change |

| Primary evidence | Molecular phylogenies, fossil records | Molecular phylogenies, fossil records | Molecular phylogenies, fossil records |

| Theoretical foundation | Punctuated equilibrium | Adaptive radiation models | Darwinian gradualism |

| Key proponents | Eldredge & Gould (1972), Douglas et al. | Various researchers | Traditional evolutionary biology |

The Early Burst Paradigm

Early burst models describe evolutionary patterns characterized by intense, rapid phenotypic or genetic change concentrated around lineage-splitting events, followed by exponential decay in evolutionary rates. This framework formalizes the concept of punctuated equilibrium introduced by paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould in 1972, which proposed that species exhibit long periods of morphological stability ("stasis") punctuated by rapid bursts of change during speciation events [1].

A recent mathematical framework developed by Jordan Douglas and colleagues introduces the parameter of evolutionary "spikes" to quantify the amount of change occurring at phylogenetic branching points. Their research demonstrates that evolutionary rates follow an exponential decay pattern following lineage divergence, with the most dramatic changes occurring immediately after splitting events. This "split-and-hit-the-gas" dynamic creates a characteristic pattern where lineages rapidly differentiate early in their history before entering extended periods of relative stability [1].

Alternative Evolutionary Models

In contrast to early burst models, several alternative frameworks offer different explanations for evolutionary patterning:

Late Burst Models: Propose that evolutionary rates accelerate later in a lineage's history, potentially in response to environmental changes, novel ecological opportunities, or adaptive radiation scenarios.

Gradualist Models: Represent the traditional Darwinian view of evolution as a steady, continuous process with changes accumulating incrementally over extended periods.

Neutral Models: Emphasize stochastic processes in evolutionary change, with rates reflecting random fluctuations rather than systematic patterns.

Table 2: Empirical Support for Different Evolutionary Models Across Biological Systems

| Biological System | Early Burst Support | Late Burst Support | Gradualist Support | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cephalopod evolution | Strong (99% of trait evolution) | Limited | Minimal | 99% of morphological evolution occurred in bursts at branching points [1] |

| aaRS enzymes | Strong (30% shorter trees) | Limited | Limited | Evolutionary spikes at branches; 30% shorter phylogenetic trees [1] |

| Indo-European languages | Strong | Limited | Limited | Burst-like changes at language splitting events [1] |

| Drosophila development | Strong (transcriptional bursting) | Limited | Limited | Transcriptional bursts with invariant timing across embryo [2] |

| Population growth | Limited | Limited | Strong (until limits) | Exponential growth until resource constraints [3] [4] |

Quantitative Analysis of Exponential Decay Patterns

Mathematical Formalization of Early Burst Dynamics

The early burst model can be mathematically described as a process of exponential decay in evolutionary rates following lineage divergence. The fundamental equation represents the decay of evolutionary rate over time:

r(t) = r₀e^(-βt)

Where:

- r(t) = evolutionary rate at time t

- r₀ = initial evolutionary rate at branching event

- β = decay coefficient representing how rapidly evolutionary rates decline

- t = time since lineage divergence

This exponential decay pattern creates the characteristic early burst signature, with the most dramatic changes concentrated immediately following lineage splitting. The Douglas study found that incorporating this exponential decay parameter resulted in phylogenetic trees that were 30% shorter with respect to gradual change, suggesting less time had passed between ancestral and descendant lineages than would be expected under gradualist models [1].

Comparative Rate Metrics Across Biological Systems

Table 3: Measured Exponential Decay Parameters Across Biological Systems

| System | Initial Rate (r₀) | Decay Coefficient (β) | Time Scale | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cephalopod morphology | Extremely high | Rapid | 500 million years | Fossil trait analysis [1] |

| aaRS molecular evolution | High | Moderate | 4 billion years | Sequence divergence analysis [1] |

| Transcriptional bursting | High | Limited (homogeneous) | 2-3 hours (NC14) | MS2/MCP live imaging [2] |

| Population decay | Variable | Resource-dependent | Decades-centuries | Resource consumption models [4] |

The analysis of cephalopod evolution revealed a particularly dramatic early burst pattern, with 99% of morphological evolution occurring in spectacular bursts near phylogenetic branching points over 500 million years, with trivial contributions from gradual evolution [1]. Similarly, studies of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) - ancient enzymes essential to protein synthesis - showed rapid evolutionary changes clustered around divergence points in their approximately 4-billion-year history [1].

Experimental Protocols for Identifying Early Burst Patterns

Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

Protocol 1: Testing Early Burst Models in Molecular Evolution

- Objective: Detect signatures of exponential rate decay in protein or DNA sequence evolution

- Data Requirements: Time-calibrated phylogenies with sequence data for multiple lineages

Methodological Steps:

- Reconstruct phylogenetic relationships using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods

- Estimate divergence times using fossil calibrations or molecular clock methods

- Fit alternative evolutionary models (early burst, gradual, late burst) to trait data

- Compare model fit using information criteria (AIC, BIC) or likelihood ratio tests

- Estimate exponential decay parameters (r₀, β) for best-fitting model

Key Analysis: The Douglas team applied this approach to aaRS enzymes, finding that models incorporating early bursts provided significantly better fit to empirical data than gradualist models [1].

Transcriptional Bursting Analysis in Development

Protocol 2: Quantifying Transcriptional Bursting Parameters

- Objective: Characterize bursting dynamics in gene expression during embryonic development

- Experimental System: Drosophila melanogaster embryos (nuclear cycle 14)

Imaging Methodology:

- Generate transgenic constructs with MS2 sequence tags (24x repeats)

- Express MCP-GFP fusion protein to label nascent transcripts

- Capture confocal microscopy images at high temporal resolution (typically 10-30 second intervals)

- Track fluorescence dynamics in individual nuclei over 2-3 hour period

- Segment and quantify fluorescence intensities using automated algorithms

Quantitative Analysis:

- Burst Duration (τON): Time period of active transcription

- Interburst Timing (τOFF): Time between successive bursts

- Loading Rate (λ*): Rate of signal increase during active bursts

- Activity Time: Time from first to last burst in observation period

Key Findings: Research on Drosophila embryonic development revealed that while mean transcription levels exhibit spatial gradients, burst duration and interburst timing remain surprisingly invariant across the embryo. The primary regulatory mechanism for spatial patterning appears to be modulation of "activity time" rather than changes in burst parameters [2].

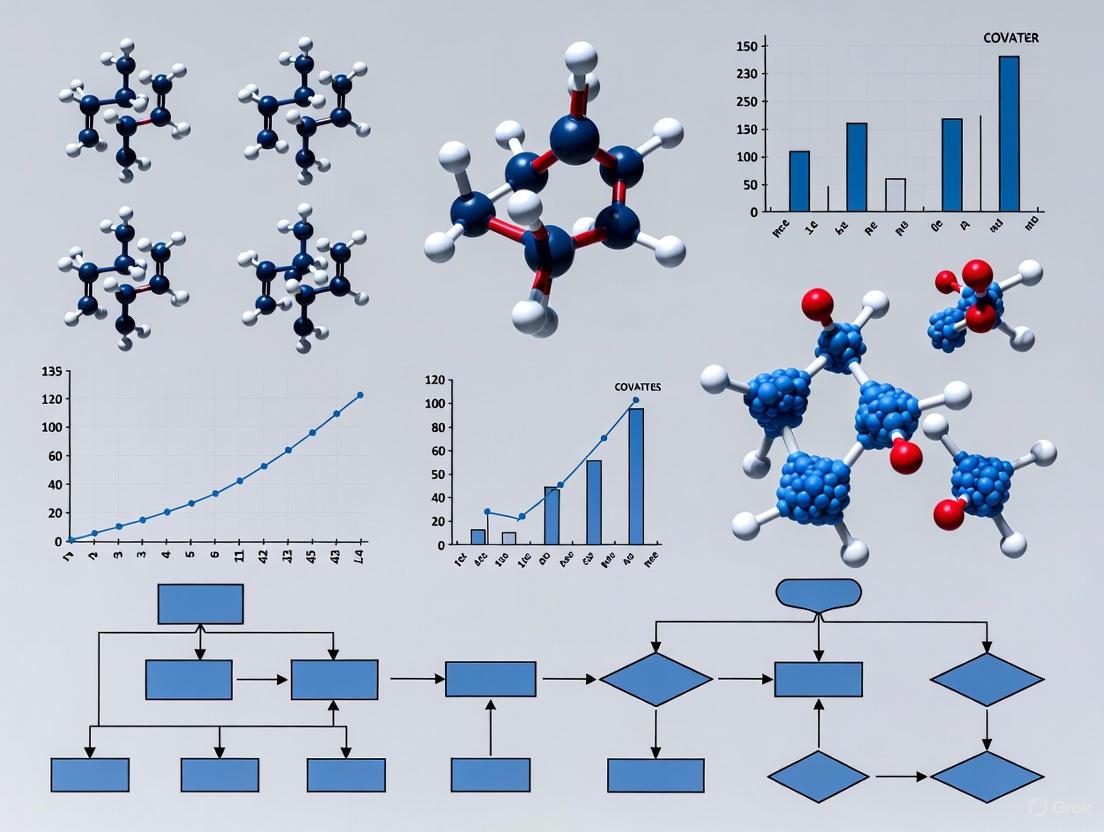

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing transcriptional bursting dynamics in early Drosophila embryo development, combining live imaging and computational approaches [2].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Bursting Dynamics

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| MS2-MCP imaging system | Transcriptional bursting analysis | Labels nascent RNA for live imaging | Tracking single-cell transcription dynamics in Drosophila [2] |

| Phylogenetic software | Evolutionary rate analysis | Models trait evolution across phylogenies | Testing early burst patterns in molecular evolution [1] |

| Fossil calibration datasets | Divergence time estimation | Provides temporal framework for phylogenies | Dating evolutionary spikes in cephalopod evolution [1] |

| Confocal microscopy | Live imaging of embryos | High-resolution spatial-temporal imaging | Capturing transcriptional dynamics in developing embryos [2] |

| Sequence alignment tools | Molecular evolution studies | Aligns homologous sequences across species | Analyzing aaRS enzyme evolution across deep time [1] |

Comparative Performance: Early Burst Versus Alternative Models

Explanatory Power Across Biological Scales

The performance of early burst models varies significantly across different biological contexts and scales of analysis:

Molecular Evolution: In studies of aaRS enzymes, early burst models provided significantly better fit to empirical data than gradualist models, producing phylogenetic trees that were 30% shorter with respect to gradual change [1]. This suggests that molecular evolution in these ancient enzymes occurred more rapidly than previously estimated under gradualist assumptions.

Morphological Evolution: Analysis of cephalopod evolution revealed an extreme early burst pattern, with 99% of morphological evolution occurring in bursts associated with lineage splitting events over 500 million years [1]. This finding challenges gradualist interpretations of morphological diversification.

Developmental Patterning: Research on Drosophila embryogenesis demonstrated that transcriptional bursting parameters (burst duration and interburst timing) remain remarkably constant across spatial expression domains, with "activity time" (the duration of active transcription periods) serving as the primary regulatory mechanism for spatial patterning [2].

Limitations and Boundary Conditions

While early burst models provide powerful explanations for many evolutionary patterns, they exhibit limitations in certain contexts:

Population Dynamics: Ecological studies of population growth typically show exponential growth until resource constraints are reached, followed by potential collapse, rather than early burst patterns [3] [4].

Microevolutionary Timescales: Population genetic processes operating within species may follow different dynamics than macroevolutionary patterns observed across species.

Environmental Context Dependence: The strength of early burst signatures may vary across taxa and environmental contexts, with some systems showing more gradualistic patterns.

Figure 2: Comparative visualization of evolutionary rate patterns under different models, highlighting the exponential decay characteristic of early burst models.

The early burst model with exponential rate decay represents a significant advancement in evolutionary biology, providing a unified mathematical framework for understanding patterns of diversification across biological scales. The evidence from molecular evolution, morphological diversification, and developmental patterning strongly supports the prevalence of exponential decay dynamics following lineage divergence events.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings have important implications:

Evolutionary Analysis: Early burst models provide more accurate estimates of divergence times and evolutionary relationships than traditional gradualist approaches.

Developmental Biology: The discovery of transcriptional bursting with invariant timing but modulated activity periods reveals novel regulatory mechanisms with potential applications in understanding developmental disorders.

Comparative Genomics: Patterns of exponential decay in evolutionary rates can help identify genes under strongest selective constraints or those driving lineage-specific adaptations.

The contrast between early burst and late burst models continues to drive productive research across evolutionary biology, ecology, and developmental biology. As new datasets and analytical methods emerge, our understanding of these fundamental evolutionary tempos will continue to refine, offering increasingly powerful tools for deciphering the patterns and processes of biological diversification.

The concept of a "burst" phenomenon manifests in remarkably diverse scientific fields, from paleobiology to pharmaceutical science. In evolutionary biology, late burst models describe patterns where morphological disparity accumulates rapidly late in evolutionary history, challenging traditional early diversification hypotheses. In drug delivery systems, burst release refers to the rapid initial elution of drug from a delivery matrix before transitioning to sustained release. This comparative analysis examines the parallel frameworks used to study these seemingly disparate phenomena, highlighting convergent methodological approaches in quantifying, modeling, and exploiting burst dynamics across disciplines.

Despite substantial differences in subject matter, researchers in both fields employ similar mathematical frameworks to characterize burst phenomena, including sigmoidal growth models, stochastic processes, and differential equation systems. This interdisciplinary comparison reveals how burst identification, measurement, and interpretation strategies transcend traditional field boundaries, offering potential for methodological cross-pollination between evolutionary biology and pharmaceutical science.

Pharmaceutical Burst Release: Mechanisms and Characterization

Defining Burst Release in Controlled Drug Delivery

In pharmaceutical sciences, burst release describes the rapid initial release of drug from a delivery system, often occurring within hours to days of administration. This phenomenon is particularly significant in matrix-controlled drug delivery systems where the initial rapid release can determine therapeutic success or failure [5]. The burst effect is characterized by a sharp increase in drug concentration, followed by a sustained release phase maintaining therapeutic levels over extended periods.

The importance of burst release in pharmaceutical applications is twofold. When properly controlled, it can provide immediate therapeutic effects following administration, potentially eliminating the need for separate loading doses. However, uncontrolled burst release can be pharmacologically dangerous and economically inefficient, delivering toxic initial doses or depleting the drug too rapidly for sustained activity [5]. This dual nature makes understanding and controlling burst release critical for advanced drug delivery system design.

Quantitative Characterization of Pharmaceutical Burst Release

Table 1: Key Parameters for Quantifying Pharmaceutical Burst Release

| Parameter | Description | Measurement Methods | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burst Strength | Percentage of total drug released during initial burst phase | Cumulative release curves, UV-Vis spectroscopy | 10-60% of total load [5] |

| Burst Duration | Time period over which initial burst occurs | Release kinetics profiling, sampling at intervals | Minutes to 48 hours [6] |

| Release Rate Constant | Kinetic constant describing burst release rate | Mathematical modeling (zero-order, first-order, Higuchi) | Variable by system design |

| Burst Control Factor | Measure of how well burst is regulated | Comparison of designed vs. actual release profiles | Dependent on formulation quality |

The quantitative assessment of burst release relies on release kinetics profiling through in vitro experiments where drug delivery systems are immersed in release media with periodic sampling and analysis. Advanced analytical techniques including UV-Vis spectroscopy, HPLC, and photoacoustic measurement provide precise drug concentration measurements [6]. These data points generate cumulative release curves that visually represent the burst phase as a steep initial slope followed by a more gradual sustained release phase.

Experimental Methodologies in Pharmaceutical Burst Release Research

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Research investigating burst release from polymeric drug delivery systems typically follows standardized experimental protocols. For PLGA-based systems (one of the most extensively studied controlled release platforms), the fundamental methodology involves:

Particle Fabrication and Drug Loading: PLGA micro-/nano-particles are commonly prepared using double emulsion solvent evaporation methods. Briefly, this involves: (1) creating a primary emulsion of drug solution in polymer solution, (2) forming a double emulsion by adding the primary emulsion to an external aqueous phase, and (3) evaporating the organic solvent to solidify the particles [7]. Key parameters controlling burst include polymer molecular weight, lactide:glycolide ratio, drug-polymer ratio, and particle size.

In Vitro Release Studies: The fabricated particles are immersed in release medium (typically phosphate buffered saline at physiological pH 7.4 or other pH values to simulate specific environments). The system is maintained at 37°C with constant agitation to simulate in vivo conditions. Samples are withdrawn at predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours initially, then daily or weekly) and replaced with fresh medium to maintain sink conditions [8].

Analytical Quantification: Withdrawn samples are analyzed to determine drug concentration. For antibiotics like vancomycin, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection is standard. Calibration curves are constructed using drug standards of known concentration [7].

Data Processing: Cumulative drug release percentages are calculated and plotted versus time to generate release profiles. The burst release is quantified as the percentage of total drug released within the first 24 hours [7].

Advanced Methodological Approaches

Recent advances incorporate more sophisticated approaches:

Machine Learning Integration: Experimental data from multiple studies are analyzed using algorithms including linear regression, principal component analysis (PCA), Gaussian process regression (GPR), and artificial neural networks (ANNs) to identify complex relationships between formulation parameters and burst release behavior [8].

Evidence-Based Design-of-Experiments (DoE): This approach extracts historical release data from literature and undergoes meta-analytic regression modeling to optimize drug delivery systems without conducting numerous new experiments. Factors like polymer molecular weight, LA/GA ratio, polymer-to-drug ratio, and particle size are simultaneously varied and correlated to burst release characteristics [7].

Theoretical Modeling and Simulation: Mathematical models based on diffusion equations, polymer degradation kinetics, and mass transfer limitations predict burst release behavior. These models account for phenomena like autocatalytic hydrolysis in PLGA systems where acidic degradation products accelerate further polymer breakdown [9].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for pharmaceutical burst release characterization, showing the standardized protocol from system design to optimization, with the burst release phase highlighted.

Mechanisms Underlying Pharmaceutical Burst Release

Physical and Chemical Mechanisms

The burst release phenomenon in drug delivery systems arises from multiple interconnected mechanisms:

Surface-Located Drug Diffusion: Drug molecules located on or near the surface of the delivery system encounter immediate contact with the release medium, leading to rapid diffusion. This represents the primary mechanism for initial burst and is influenced by matrix porosity, drug-polymer affinity, and surface area to volume ratio [5].

Polymer Swelling and Hydration: As water penetrates the polymer matrix, it creates aqueous pathways for drug diffusion. The rate and extent of hydration significantly impact burst magnitude, with faster hydration typically increasing initial release [9].

Osmotic Pumping: Concentration gradients between the internal and external environments create osmotic pressure that drives drug release, particularly for water-soluble drugs encapsulated in semi-permeable matrices [8].

Polymer Degradation Initiation: In biodegradable systems like PLGA, initial ester bond hydrolysis begins immediately upon hydration, creating additional pores and channels for drug release. The autocatalytic effect of acidic degradation products can accelerate this process in the particle core [9].

Factors Influencing Burst Release Magnitude

Table 2: Key Factors Affecting Pharmaceutical Burst Release and Experimental Control Methods

| Factor Category | Specific Factors | Effect on Burst Release | Experimental Control Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Properties | Molecular weight, Crystallinity, LA:GA ratio, End groups | Lower MW increases burst; more hydrophilic polymers (higher GA) increase burst | Polymer synthesis, Blending, Additives |

| Drug Properties | Solubility, Molecular size, Loading percentage, Drug-polymer interactions | Higher solubility increases burst; smaller molecules increase burst | Prodrug approaches, Salt forms, Co-encapsulation |

| System Morphology | Particle size, Porosity, Surface area, Wall thickness | Smaller particles increase burst; higher porosity increases burst | Fabrication method optimization, Processing parameters |

| Release Conditions | pH, Temperature, Osmolarity, Sink conditions | Acidic pH increases PLGA burst; higher temperature increases burst | Medium selection, Agitation control |

The complex interplay of these factors means that burst release must be optimized rather than eliminated for most therapeutic applications. For instance, in antibiotic treatments for osteomyelitis, an effective initial burst is necessary to prevent biofilm formation during the critical first 24 hours, while subsequent sustained release maintains therapeutic concentrations [7].

Comparative Analysis: Late Burst in Evolutionary Biology

Paleontological Evidence and Methodologies

While this review focuses primarily on pharmaceutical burst release, understanding the comparative framework requires examining key aspects of late burst phenomena in evolutionary biology:

Morphological Disparity Measurements: Evolutionary biologists quantify phenotypic diversity across taxa using morphometric analyses of fossil specimens. Disparity indices capture the extent of morphological differences across species rather than simple taxonomic counts [5].

Temporal Pattern Analysis: By tracing disparity measures through geological time, researchers identify periods of rapid morphological expansion versus relative stasis. Late bursts manifest as significant increases in disparity late in clade evolution rather than early diversification [5].

Comparative Methodologies: Interestingly, evolutionary biologists increasingly employ multivariate statistical analyses, model-fitting approaches, and Bayesian inference methods that share mathematical foundations with pharmaceutical release modeling, despite dramatic differences in subject matter [5].

Convergent Analytical Frameworks

Both fields face similar challenges in distinguishing true burst patterns from sampling artifacts or preservation biases. The analytical convergence includes:

Stochastic Process Modeling: Both fields utilize random walk models, diffusion processes, and branching models to characterize burst dynamics against background variation [5].

Model Selection Approaches: Researchers in both fields employ information-theoretic criteria (e.g., AIC, BIC) to distinguish between alternative models of burst phenomena, whether comparing early versus late burst scenarios in evolution or different release mechanisms in pharmaceuticals [7].

Time-Series Analysis: Techniques for analyzing sequential data points apply to both fossil temporal series and drug release kinetics, requiring similar corrections for autocorrelation and sampling interval effects [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for Burst Release Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Pharmaceutical Burst Release Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA Polymers | Primary matrix material for controlled release | Varying MW (10-100 kDa) and LA:GA ratios (50:50 to 85:15) to modulate degradation and release [9] |

| Polymer Characterization Kits | Analysis of MW, polydispersity, end groups | GPC/SEC systems for quality control; NMR for composition verification [7] |

| Model Drugs | Standard compounds for release studies | Vancomycin (antibiotic), Doxorubicin (anticancer), Dexamethasone (anti-inflammatory) [7] [6] |

| Release Media | Simulating physiological conditions | Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4; customized pH buffers for specific environments [8] |

| Analytical Standards | Quantification of drug release | HPLC-grade reference compounds; validated calibration standards [7] |

| Encapsulation Efficiency Kits | Determining drug loading parameters | Solvent extraction systems; centrifugation filters; spectrophotometric assays [7] |

This comparative analysis reveals striking methodological parallels in how disparate scientific fields identify, quantify, and model burst phenomena. While evolutionary biology examines macroevolutionary patterns across geological timescales and pharmaceutical science investigates molecular release over days to weeks, both employ similar mathematical frameworks and analytical approaches.

The cross-disciplinary comparison suggests potential for methodological exchange. Evolutionary biology's sophisticated approaches to temporal series analysis and model-based inference could enhance pharmaceutical release modeling, while pharmaceutical science's controlled experimentation frameworks and high-resolution quantification might inform new approaches in paleobiology.

Understanding burst phenomena in both contexts requires moving beyond simple descriptive accounts to mechanism-based explanatory frameworks that account for complex systems dynamics. The continued development of these interdisciplinary connections promises to advance both fields through shared analytical innovations and conceptual refinements.

The journey of a drug from initial discovery to market approval represents a fundamental tension between two opposing forces: the ecological opportunity to discover potent new therapeutic agents and the physiological and formulation constraints that dictate their viability in the human body. This dichotomy mirrors evolutionary biology's "early burst" and "late burst" models of diversification, where initial rapid innovation is followed by periods of refinement constrained by environmental factors. In pharmaceutical science, the early burst manifests as the prolific discovery of bioactive compounds from diverse natural sources and synthetic libraries, while the late burst represents the meticulous optimization required to overcome human physiological barriers and formulation challenges.

The high attrition rate in drug development underscores the critical nature of this balance. Current estimates indicate that approximately 90% of drug candidates fail to progress through clinical trials to market approval, with unexpected toxicity and lack of efficacy representing significant contributing factors [10]. Furthermore, the drug development process remains extraordinarily resource-intensive, requiring an average of 12 years and $2.4 billion to bring a single drug to market [11]. Understanding the theoretical framework governing the interplay between opportunity and constraint is thus essential for advancing pharmaceutical research and development.

Ecological Opportunity: The Drug Discovery Landscape

Conceptual Framework and Historical Foundations

Ecological opportunity in drug discovery refers to the vast, untapped potential of chemical space from which novel therapeutic entities can be sourced. This encompasses natural products derived from plants, marine organisms, and microbes, along with synthetically generated compound libraries. The concept draws from evolutionary biology's adaptive radiation model, where species rapidly diversify to fill ecological niches when new opportunities arise. Similarly, when new disease targets or biological pathways are identified, they create "opportunity spaces" that researchers rapidly explore with diverse chemical entities.

Historically, natural products have made monumental contributions to pharmacotherapy, particularly in oncology and infectious diseases [12]. These complex molecules have evolved to interact with biological systems, providing valuable starting points for drug development. The historical dominance of natural products is evidenced by analysis showing that they represent a significant proportion of all small molecule drugs approved between 1981 and 2014 [12]. This rich chemical diversity represents an ecological landscape ripe for exploration, with technological advances continuously expanding the accessible territory.

Modern Approaches and Technological Enablers

Contemporary drug discovery has developed sophisticated methodologies to capitalize on ecological opportunity:

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD): This approach identifies compounds based on their effects on cells or whole organisms without requiring prior knowledge of specific molecular targets [13]. PDD does not rely on hypotheses about specific drug targets, instead focusing on modifying disease phenotypes, which has led to its resurgence in identifying first-in-class medicines.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS): The development of HTS and combinatorial chemistry in the 1990s enabled researchers to rapidly test thousands to millions of compounds against biological targets, creating unprecedented access to potential drug candidates [14].

Advanced Analytical Technologies: Modern techniques including improved analytical tools, genome mining, and engineering strategies are revitalizing natural product research [12]. Technologies such as ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy have dramatically accelerated metabolite identification and dereplication processes [12].

Artificial Intelligence in Discovery: AI and machine learning approaches are increasingly deployed to navigate chemical space, predict compound bioactivity, and optimize molecular structures [10]. These computational methods can integrate vast datasets encompassing drug structures, target proteins, and toxicity profiles, enabling more efficient identification of promising candidates.

Table 1: Technologies Expanding Ecological Opportunity in Drug Discovery

| Technology | Application | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening | Rapid testing of compound libraries against biological targets | Enabled evaluation of millions of compounds, identifying hits that would be missed with smaller screens |

| Genome Mining | Identification of natural product biosynthetic gene clusters | Unlocks cryptic metabolic pathways and previously inaccessible natural products |

| Metabolomics | Comprehensive analysis of metabolites in biological systems | Accelerates dereplication and identification of novel bioactive compounds from complex mixtures |

| AI-Powered De Novo Design | Generation of novel molecular structures with desired properties | Expands accessible chemical space beyond existing compound libraries |

Physiological and Formulation Constraints: The Optimization Imperative

The Framework of Pharmaceutical Constraints

While ecological opportunity provides a wealth of potential drug candidates, physiological and formulation constraints create formidable barriers that must be overcome for successful therapeutic development. These constraints operate as selective pressures that determine which discovered compounds will ultimately succeed as viable medicines. The principal constraint categories include:

Pharmacokinetic Barriers: A drug must be efficiently absorbed, distributed to its site of action, metabolized appropriately, and excreted without generating toxic byproducts (the ADME profile). Many promising compounds fail due to poor pharmacokinetic properties, including inadequate bioavailability, rapid clearance, or problematic metabolism.

Biopharmaceutical Limitations: According to the Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS), drugs are categorized based on solubility and permeability characteristics [14]. There has been a notable rise in poorly soluble BCS Class II drugs under development, creating significant formulation challenges [14].

Toxicity and Safety Concerns: Approximately 20%–40% of drug candidates fail due to safety issues or toxicities discovered during development [11]. Even after market approval, about 8% of drugs are subsequently withdrawn due to unacceptable side effects [11].

Physiological Variability: Individual differences in physiology due to factors such as age, sex, disease state, and genetic polymorphisms create additional layers of complexity for drug development [14].

Key Experimental Models for Evaluating Constraints

Researchers employ various experimental systems to evaluate how drug candidates will behave under physiological constraints:

Diagram 1: Constraint evaluation workflow for drug candidates

Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

Protocol Overview: PBPK modeling represents a "middle-out" approach that integrates physiological information with drug-specific physicochemical data to simulate a compound's in vivo behavior [14]. The model structure consists of organ and tissue compartments connected by circulating blood, with each compartment described by differential equations containing physiological parameters.

Key Parameters:

- Drug-dependent parameters: Molecular weight, diffusion coefficient, solubility across physiological pH range, ionization constants, and formulation factors.

- System-dependent parameters: Gastric emptying rate, gastrointestinal fluid pH, intestinal transit time, blood flow rates, and organ volumes [14].

Application in Constraint Assessment: PBPK modeling is particularly valuable for predicting complex clinical scenarios, including drug-drug interactions, food effects, and pharmacokinetics in special populations [14]. This approach helps researchers understand how physiological constraints will impact drug behavior before conducting extensive clinical trials.

Microphysiological Systems (MPS)

Protocol Overview: MPS (also known as organs-on-chips) are biomimetic devices that emulate human organ-level physiology [15]. These systems typically incorporate human cells in three-dimensional architectures under physiologically relevant fluid flow and mechanical forces.

Key Features:

- 3D tissue architecture rather than 2D cell layers

- Multiple cell types to recapitulate tissue complexity

- Incorporation of biomechanical forces (e.g., stretch, shear stress) [15]

Application in Constraint Assessment: MPS platforms have demonstrated superior ability to replicate human-specific drug responses compared to traditional animal models. For example, a human kidney proximal tubule MPS model successfully replicated cisplatin toxicities that were not detected in animal studies due to species-specific differences in transporter expression [15]. These systems are particularly valuable for predicting human-specific toxicity and metabolism constraints.

Artificial Intelligence for Toxicity Prediction

Protocol Overview: AI and machine learning approaches predict drug toxicity by analyzing chemical structures, target interactions, and existing toxicity data [10]. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling combined with AI has proven highly effective in categorizing compounds across multiple hazard categories.

Application in Constraint Assessment: Computational models can predict various toxicity endpoints, including acute toxicity, sensitization, carcinogenicity, and reproductive toxicity [10]. These approaches have demonstrated classification success rates exceeding those of conventional in vivo tests in some cases, providing an efficient means of identifying toxicity constraints early in development.

Comparative Analysis: Opportunity Versus Constraint

Quantitative Comparison of Discovery and Development Phases

Table 2: Drug Discovery and Development Pipeline - Opportunity vs. Constraint Focus

| Development Stage | Ecological Opportunity Emphasis | Physiological/Formulation Constraint Emphasis | Primary Screening/Evaluation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Novel biological pathways, unmet medical needs | Druggability of target, therapeutic window | Genomic/proteomic analysis, CRISPR screening |

| Lead Discovery | Diverse compound libraries, natural product sources | Preliminary ADME assessment, chemical tractability | High-throughput screening, phenotypic screening |

| Lead Optimization | Structural diversity, potency enhancement | Comprehensive ADMET profiling, early formulation | Medicinal chemistry, in vitro ADME assays |

| Preclinical Development | Mechanism of action confirmation | Safety pharmacology, formulation development | Animal models, MPS, PBPK modeling |

| Clinical Trials | Proof of concept in humans | Human pharmacokinetics, therapeutic index | Clinical pharmacology, therapeutic monitoring |

Experimental Data Comparison Across Model Systems

Table 3: Predictive Performance Across Experimental Models for Constraint Assessment

| Model System | Key Measurable Parameters | Human Predictivity Limitations | Resource Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Cell Culture | IC50, EC50, cellular toxicity | Lacks tissue-level complexity and systemic effects | Low cost, high throughput |

| Animal Models | In vivo efficacy, pharmacokinetics, toxicity | Species differences in metabolism, immune response | High cost, moderate throughput, ethical concerns |

| Microphysiological Systems | Organ-level functionality, human-specific toxicity | Limited multi-organ interaction in single systems | Moderate cost and throughput, increasing availability |

| PBPK Modeling | Predicted human pharmacokinetics, drug-drug interactions | Dependent on quality of input parameters | Low cost once established, high throughput in silico |

| AI Toxicity Prediction | Multiple toxicity endpoints, ADMET properties | Limited by training data quality and breadth | Low cost, very high throughput |

Integration and Future Directions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Opportunity and Constraint Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC-derived Cells | Provide human-specific cell types for screening and toxicity assessment | Creates physiologically relevant human cells for MPS and in vitro studies |

| 3D Extracellular Matrices | Mimic tissue-specific microenvironment for 3D cell culture | Enables development of physiologically relevant MPS models |

| LC-HRMS Systems | Identify and characterize novel compounds from complex mixtures | Facilitates dereplication and metabolite identification in natural product studies |

| PBPK Software Platforms | Simulate drug pharmacokinetics in virtual human populations | Predicts human pharmacokinetics and dosage regimens prior to clinical trials |

| AI/QSAR Prediction Tools | Forecast toxicity and ADMET properties from chemical structure | Enables early triaging of compounds with likely toxicity issues |

Strategic Integration Framework

The most successful drug development programs strategically integrate ecological opportunity with constraint assessment throughout the research pipeline. The following workflow illustrates this integrated approach:

Diagram 2: Integrated drug discovery and optimization workflow

This integrated approach enables researchers to:

- Apply constraint-based filters early in the discovery process to focus resources on chemically tractable compounds with favorable physicochemical properties

- Iteratively optimize lead compounds based on constraint assessment feedback

- Utilize human-relevant systems like MPS and PBPK modeling to derisk candidates before advancing to clinical trials

- Balance the pursuit of novel therapeutic mechanisms (opportunity) with practical development considerations (constraints)

The evolving toolkit for navigating drug development—including MPS, PBPK modeling, and AI-powered prediction—is progressively enhancing our ability to balance ecological opportunity with physiological and formulation constraints. This balanced approach promises to improve the efficiency of pharmaceutical development, potentially reducing the current high attrition rates and enabling more effective therapies to reach patients in need.

The concept of evolutionary "bursts," wherein lineages experience rapid morphological diversification, represents a central paradigm in evolutionary biology. This framework challenges strictly gradualist views of evolution, proposing instead that periods of relative stasis are punctuated by episodes of accelerated change. G.G. Simpson's seminal work, Tempo and Mode in Evolution (1944), introduced the foundational concept of adaptive zones—broad niches defined by particular environmental parameters and functional demands—and proposed quantum evolution as a hypothetical mechanism for rapid transition between them [16]. Simpson theorized that lineages could enter new adaptive zones through three primary pathways: the extinction of competitors, dispersal to new geographic areas, or the evolution of a key innovation [17].

The modern reformulation paradigm has translated Simpson's macroevolutionary concepts into rigorous, quantitative models tested with phylogenetic and morphological data. Contemporary research focuses on distinguishing the tempo and mode of these evolutionary bursts, primarily contrasting the "early burst" model—predicting rapid morphological divergence early in a radiation that slows as ecological space fills—with various "late burst" or alternative models [18] [19]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of these competing models against empirical data from diverse biological systems, providing researchers with a clear analysis of their strengths, limitations, and applicable contexts.

Experimental Protocols for Identifying Evolutionary Bursts

Phylogenomic Divergence Time Estimation

Purpose: To establish a robust, time-calibrated phylogenetic framework essential for testing hypotheses about the timing of evolutionary bursts.

Detailed Methodology:

- Gene Capture and Sequencing: Isolate and sequence hundreds to thousands of conserved nuclear loci across representative species within the clade of interest. For example, the Tiliquini skink study utilized ~400 nuclear markers [20].

- Sequence Alignment and Concatenation: Align sequences using multiple sequence alignment algorithms (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE) and assess congruence between individual gene trees.

- Species Tree Inference: Employ coalescent-based methods (e.g., ASTRAL, SVDquartets) or Bayesian concatenation (e.g., ExaBayes, MrBayes) to infer the species tree from the multi-locus dataset.

- Time Calibration: Integrate fossil data or known geological events as calibration points to estimate node ages using Bayesian relaxed-clock methods implemented in software such as BEAST2 or MCMCTree. This provides the absolute timescale necessary for rate analyses.

Morphometric Landmarking and Disparity Analysis

Purpose: To quantify phenotypic diversity and track its accumulation through time.

Detailed Methodology:

- Trait Selection and Measurement: Select quantitative morphological traits with clear functional and adaptive significance. The Anolis lizard studies, for instance, measured 10 morphological traits including limb dimensions, body size, and toepad characteristics [18].

- Morphospace Construction: Use Principal Components Analysis (PCA) on the correlation matrix of log-transformed measurements to create a multidimensional morphospace. The resulting principal components represent major axes of morphological variation.

- Disparity Calculation: Compute morphological disparity for clades and time slices, typically as the sum of variances across the major principal component axes or the average Euclidean distance between species in morphospace.

- Trait Evolution Modeling: Fit different evolutionary models to the trait data mapped onto the time-calibrated phylogeny using maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference in packages like

geiger(R) or BayesTraits.- Brownian Motion (BM): Assumes a constant rate of random drift.

- Early Burst (EB): Tests for exponentially decreasing rates of evolution.

- Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU): Tests for constrained evolution around adaptive peaks.

- Multi-Rate (BMS): Allows for different rates of evolution on different branches.

Diversification Rate Analysis

Purpose: To determine the timing and rate of lineage splitting, testing for correlations between speciation and morphological evolution.

Detailed Methodology:

- Lineage-Through-Time (LTT) Plots: Generate semi-log plots of cumulative lineages against time to visualize changes in net diversification rates.

- Rate-Shift Analysis: Apply model-based methods (e.g., BAMM, DDD) to identify significant shifts in speciation and extinction rates across the phylogeny. For example, analyses of mainland anole radiations (M2) incorporated BAMM, HiSSE, and Pulled Diversification Rate (PDR) approaches [18].

- Model Selection: Use statistical criteria (e.g., AICc, Bayes Factors) to compare the fit of different diversification models (e.g., constant-rate, density-dependent, rate-shift) to the observed phylogenetic branching pattern.

Table 1: Key Analytical Methods for Detecting Evolutionary Bursts

| Method Category | Specific Analytical Tool | Primary Output | Data Input Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Divergence Time Estimation | BEAST2, MCMCTree | Time-calibrated phylogeny | Molecular sequences, fossil calibrations |

| Trait Evolution Modeling | geiger (R), mvMORPH (R), BayesTraits |

Model fit statistics (AICc, Bayes Factors), rate parameters | Time-calibrated phylogeny, trait measurements |

| Diversification Rate Analysis | BAMM, RPANDA, DDD | Speciation & extinction rate estimates through time, rate-shift locations | Time-calibrated phylogeny |

| Morphological Disparity Analysis | Custom scripts in R, geomorph |

Disparity-through-time plots, morphospace visualizations | Trait measurements, time-calibrated phylogeny |

Comparative Performance Data: Evolutionary Models vs. Empirical Evidence

Testing Simpsonian hypotheses with modern data reveals that evolutionary bursts are common, but their specific patterns—the "tempo and mode"—vary significantly across clades and ecosystems.

Performance in Island vs. Mainland Adaptive Radiations

The adaptive radiation of Anolis lizards provides a powerful natural experiment for comparing evolutionary models, having produced two independent mainland radiations (M1, M2) and the classic island radiation of the Greater Antilles (GA) [18].

Table 2: Performance of Evolutionary Burst Models in Anolis Lizards

| Radiating Clade | Diversification Mode | Morphological Evolution Mode | Key Supporting Evidence | Model Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Antilles (GA) - Island | No consistent early burst signal in species diversification [18]. | Early Burst (EB) / Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU): High initial rates of phenotypic evolution, slowing over time [18]. | Evolution of stereotyped ecomorphs; high morphological disparity [18] [17]. | Strong fit for early burst/OU in morphology, but not lineage diversification. |

| Mainland 1 (M1) - Incumbent | Weak/conflicting support for early burst (only 1 of 3 methods supported it) [18]. | Early Burst (EB) / Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU): Pattern of rapid early phenotypic evolution [18]. | Achieved high ecological amplitude and morphological disparity [18]. | Moderate fit for early burst in morphology. |

| Mainland 2 (M2) - Island-Derived | Pronounced Early Burst: Significantly elevated lineage diversification rates early in the radiation, followed by slowdown [18]. | Brownian Motion (BM): Consistently low rates of morphological evolution throughout history [18]. | Achieved ~88% of M1's disparity via high species proliferation, not high per-lineage change [18]. | Strong fit for early burst in lineage diversification; poor fit for EB in morphology. |

The data reveals two distinct paths to adaptive radiation: one via rapid phenotypic evolution (GA, M1) and another via rapid lineage diversification without concurrent high morphological divergence (M2) [18]. This indicates that the Early Burst model is not a monolithic pattern but can manifest differently in different contexts.

Performance in Explaining Complex Morphological Novelties

Studies of morphological trait evolution in Tiliquini skinks (bluetongues and relatives) further refine our understanding of evolutionary bursts. Research shows that most individual traits evolve under a conservative, gradual process. However, infrequent evolutionary bursts along specific branches result in morphological novelty. This pattern, termed "punctuated gradualism," is inconsistent with both pure gradualism and classic punctuated equilibrium. Instead, it involves rapid rate increases along individual branches, leading to the rapid evolution of distinct forms like "blue-tongued giants" and "armored dwarves" [20]. This suggests that the Early Burst model, when applied at the whole-organism level, may mask a more complex heterogeneity in the tempo and mode of evolution across individual traits.

Model Performance in a Macroevolutionary Context

From a broader perspective, analyses of fossil and phylogenetic data often treat the Early Burst (EB*) model as a special case of Brownian diffusion with an exponentially decelerating rate. When modeled over macroevolutionary timescales (e.g., millions of generations), even standard Brownian and Ornstein-Uhlenbeck models predict the most rapid accumulation of disparity early in a clade's history [19]. This suggests that an "early burst" of phenotypic disparity may be a common, even expected, feature of evolutionary radiations, explaining its frequent identification in empirical studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Evolutionary Burst Studies

| Reagent / Tool Name | Function / Application | Field of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Exon-Capture Assay Kits | Target enrichment for sequencing hundreds to thousands of conserved nuclear loci from tissue or degraded samples. | Phylogenomics |

| BEAST2 Software Package | Bayesian phylogenetic analysis for inferring time-calibrated evolutionary trees from molecular sequence data. | Divergence Time Estimation |

| geiger R Package | A primary tool for fitting and comparing evolutionary models (BM, EB, OU) to phenotypic trait data on phylogenies. | Trait Evolution Modeling |

| BAMM Software | Bayesian Analysis of Macroevolutionary Mixtures; identifies and characterizes complex shifts in speciation and extinction rates. | Diversification Analysis |

| MS2/MCP Live Imaging System | Labels nascent mRNA transcripts with a fluorescent marker (MCP-GFP) to visualize transcriptional bursting in real-time. | Gene Regulation |

| Morphometric Landmarking Software | Digitize and analyze coordinate-based landmarks from specimen images to quantify morphological shape and variation. | Morphometrics |

Conceptual Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated conceptual workflow for testing hypotheses about evolutionary bursts, from data collection to model selection and interpretation.

Conceptual Workflow for Testing Evolutionary Burst Models

The following diagram illustrates a generalized signaling pathway representing the regulation of gene expression patterns involved in the development of novel morphological structures, a potential mechanism underlying evolutionary bursts.

Gene Regulation Pathway in Morphological Evolution

The modern reformulation of Simpson's adaptive zones has transformed his qualitative concepts into a dynamic, quantitative field. Empirical evidence from diverse systems like anoles and skinks demonstrates that evolutionary bursts are a real and important feature of life's history, yet no single model universally captures their complexity. The performance of Early Burst versus alternative models is highly context-dependent, varying between island and mainland settings, between lineage diversification and morphological evolution, and even between different trait modules within the same organism.

The prevailing view is one of heterogeneity. Evolutionary bursts are not monolithic; they represent a suite of phenomena driven by different mechanisms (e.g., key innovations, ecological opportunity, colonization) and expressed in different patterns (e.g., early bursts of morphology, early bursts of lineage diversification, or punctuated gradualism). The most productive path forward for researchers lies in moving beyond simple model comparisons toward developing more complex, integrated models that can account for this observed heterogeneity. Future research will likely focus on linking microevolutionary processes—such as the transcriptional bursting in gene regulation that creates phenotypic variability [2]—to these macroevolutionary patterns, finally closing the loop between the genotype and the grand tapestry of adaptive radiation.

Quantitative Frameworks and Real-World Applications Across Disciplines

Phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) provide the essential statistical framework for testing evolutionary hypotheses by analyzing trait data across species within their phylogenetic context. These methods primarily rely on mathematical models that describe how traits evolve along the branches of phylogenetic trees. For continuous data, such as morphological measurements or gene expression levels, three cornerstone models form the foundation of most analyses: Brownian Motion (BM), Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU), and Early-Burst (EB) models. Each embodies a distinct evolutionary process, from random drift to stabilizing selection to adaptive radiation. The performance and interpretation of these models are central to a broader thesis contrasting early burst and late burst models in evolutionary biology, which seek to explain the timing and pace of phenotypic divergence. As comparative datasets grow—encompassing not only traditional morphological traits but also molecular phenotypes like gene expression—understanding the implementation, strengths, and limitations of these models becomes increasingly critical for researchers in evolutionary biology, systematics, and even drug development where evolutionary principles inform target selection [21].

Core Evolutionary Models: Theory and Assumptions

Brownian Motion (BM)

Brownian Motion serves as a fundamental null model in evolutionary biology. It conceptualizes trait evolution as a random walk, where changes in each time step are random, independent, and drawn from a distribution with a mean of zero and a constant variance (σ²). This variance represents the evolutionary rate under the model. The expected trait value remains constant over time (lacking any directional trend), but the variance among lineages increases linearly with time. BM is often interpreted as mimicking the outcome of genetic drift or fluctuating selection in an unchanging environment [22] [23]. Its simplicity and mathematical tractability make it a baseline for comparing more complex models.

Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU)

The Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model extends BM by incorporating a centralizing force that pulls the trait toward a specific optimum or adaptive peak (θ). This force, characterized by the selection strength parameter (α), represents stabilizing selection. The further a trait is from its optimum, the stronger the pull back toward it. Unlike BM, under which variance can increase indefinitely, the OU model predicts that trait variance among lineages will reach a stable equilibrium, thereby eroding phylogenetic signal over deep timescales [22] [23]. The model can be complexified into the Hansen model, which allows for different selective regimes (multiple θ values) across the branches of a phylogeny, corresponding to shifts in ecology or adaptation [23].

Early-Burst (EB)

The Early-Burst model, also known as the ACDC (Accelerating-Decelerating) model, describes a scenario where the rate of evolution is highest early in a clade's history and slows down exponentially thereafter. This pattern is characteristic of models of adaptive radiation, where ecological opportunities are abundant following an invasion or innovation, but become filled over time, slowing the pace of divergence. The EB model thus directly tests predictions about the timing of phenotypic diversification [22] [24].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and key characteristics of these core models and their extensions.

Quantitative Model Comparison

The following table summarizes the key parameters, evolutionary interpretations, and typical use cases for the BM, OU, and EB models, providing a structured comparison for researchers.

Table 1: Core Parameters and Interpretations of Evolutionary Models

| Model | Key Parameters | Biological Interpretation | Expected Pattern | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brownian Motion (BM) | σ² (rate), z₀ (root value) | Genetic drift or random walk in a neutral landscape [22] | Variance increases linearly with time [22] | Null model; phylogenetic regression [22] |

| Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) | α (strength), θ (optimum), σ² (rate) | Stabilizing selection toward an optimum [22] [23] | Variance reaches an equilibrium; phylogenetic signal decays [23] | Testing for stabilizing selection; adaptive regimes [23] |

| Early-Burst (EB) | r (rate decay), σ² (initial rate), z₀ (root value) | Adaptive radiation with declining ecological opportunity [22] [24] | High early disparity, slowing rate over time [24] | Identifying adaptive radiations [24] |

Recent empirical studies testing these models on large datasets have revealed interesting patterns. A 2022 study analyzing body size evolution across 2,859 mammalian species found that both directional changes (β) and evolvability changes (υ) made substantial, often independent, contributions to explaining macroevolutionary patterns. This "Fabric model" showed that watershed moments of increased evolvability were common, outnumbering reductions, and that large phenotypic shifts could be explained as biased random walks without requiring special jump mechanisms [24]. In a different context, a 2024 phylogenomic study of Tiliquini skinks found that most morphological traits evolved conservatively, but infrequent evolutionary bursts resulted in morphological novelty. This "punctuated gradualism" was inconsistent with both pure gradualism and classic punctuated equilibrium, demonstrating the heterogeneity of evolutionary tempo and mode [20].

Experimental Protocols for Model Implementation

Data Preparation and Phylogenetic Alignment

The initial step involves preparing the trait data and phylogeny. The trait data (e.g., body size, gene expression level) must be a continuous numerical vector, and the tip labels in the phylogenetic tree must exactly match the names in the trait data. The R function treedata from the geiger package is commonly used to automatically match and prune the tree and data to a common set of species, ensuring they are aligned for analysis [22].

Model Fitting withfitContinuous

A standard tool for fitting these models in R is the fitContinuous function within the geiger package. The basic syntax for fitting the three core models is consistent [22]:

- Inputs:

phy(the phylogenetic tree) anddat(the trait data vector). - Model Specification: The

modelargument is set to"BM","OU", or"EB". - Output: The function returns a model object containing parameter estimates, the log-likelihood, and AIC/AICc values.

Example code for fitting a Brownian Motion model:

Model Comparison and Selection

After fitting multiple models to the same dataset, statistical model comparison is used to identify the best-fitting model. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or its small-sample correction (AICc) are standard metrics. A lower AIC value indicates a better balance of model fit and complexity. A difference in AIC (ΔAIC) of >2-4 is often considered substantial evidence in favor of the model with the lower value. The log-likelihood values can also be used for formal Likelihood Ratio Tests (LRTs) when models are nested (e.g., BM is a special case of OU when α = 0) [22] [21].

Performance Assessment witharbutus

It is critical to assess the absolute performance of a model, not just its relative performance. A model selected via AIC may still be a poor description of the data. The R package arbutus provides tools for this assessment using parametric bootstrapping. The procedure involves [21]:

- Simulating new datasets using the parameter estimates from the fitted model.

- Calculating a suite of test statistics (e.g., C-statistic, slope of a morphological disparity plot) on both the observed and simulated data.

- Comparing the observed statistics to their distribution under the simulated data. A good-fitting model will have observed statistics that fall within the distribution of the simulated statistics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Software and Analytical Tools for Evolutionary Modeling

| Tool Name | Environment/Package | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

fitContinuous |

R / geiger |

Fits BM, OU, EB, and other models to a tree and trait data [22] | Maximum likelihood estimation; returns AIC for comparison |

arbutus |

R / arbutus |

Assesses absolute goodness-of-fit for phylogenetic models [21] | Uses parametric bootstrapping and multiple test statistics |

OUwie |

R / OUwie |

Fits multi-optima OU models (Hansen model) [22] | Allows different selective regimes on different branches |

phytools |

R / phytools |

Suite for phylogenetic analysis & visualization [22] | Includes contMap for visualizing trait evolution on trees |

| Bayesian MCMC | bayou, POUMM, RevBayes |

Bayesian inference of complex evolutionary models [23] | Allows incorporation of prior knowledge; useful for parameter-rich models |

Emerging Frontiers and Model Extensions

The field of phylogenetic comparative methods is rapidly advancing beyond the three core models. New frameworks are being developed to better capture the complex fabric of macroevolution. The Fabric model, for instance, separately identifies directional changes (β) that shift the mean phenotype and evolvability changes (υ) that alter a clade's ability to explore trait-space, without a priori linking them [24]. This approach can explain large phenotypic shifts as biased random walks, recasting macroevolution in terms of gradualist microevolutionary processes.

Another significant frontier is the account of saltative branching or punctuated equilibrium. A 2025 study analyzing cephalopods, enzymes, and languages found that 99% of evolutionary change can cluster predictably at the nodes (branching points) of trees. This challenges the assumption of gradual, independent evolution post-split and introduces "spikes" of change and "phantom bursts" from extinct lineages into evolutionary models [1]. Furthermore, the move toward Bayesian inference for OU models addresses issues of parameter identifiability and allows the incorporation of prior knowledge, though it requires careful consideration of prior distributions to avoid unintended influences on the posterior estimates [23]. As these models are increasingly applied to new data types like comparative gene expression, rigorous assessment of model performance will be essential for reliable biological inference [21].

The "early burst" model of evolution hypothesizes that rates of morphological change are highest early in a clade's history, followed by a slowdown as ecological niches are filled. This pattern is a key prediction of adaptive radiation theory, where species rapidly diversify to exploit ecological opportunity [25]. Conversely, "late burst" or multi-rate models suggest that evolutionary rates are more variable, with peaks possible at any time due to continuing environmental changes or niche shifts.

This guide objectively compares research methodologies and findings from two distinct fields within amniote evolution: squamate color brightness and amniote body size. By comparing the experimental data and analytical protocols, we provide a framework for researchers evaluating evolutionary tempo and mode in their own systems.

Experimental Data Comparison: Squamate Color vs. Amniote Body Size

Table 1: Summary of Key Comparative Findings

| Feature | Squamate Color Brightness Evolution | Amniote Body Size Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Analytical Model | Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) [26] | Nested Early Burst (EB) & Brownian Motion (BM) [25] |

| Best-Fitting Model | Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) [26] | Models allowing multiple BM or OU shifts [25] |

| Support for Early Burst | Limited (OU > EB) [26] | Prevalent in subclades, but not the best overall model [25] |

| Key Driving Factor | Habitat openness [26] | Ecological opportunity at clade origins [25] |

| Phylogenetic Signal | Strong (Pagel's lambda = 0.75) [26] | Not explicitly reported |

| Data Type | Continuous (Brightness %) [26] | Continuous (Log body size) [25] |

Table 2: Methodological and Data Scope Comparison

| Aspect | Squamate Color Study | Amniote Body Size Study |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Scope | 1249 squamate species (global) [26] | Mammals, squamates, and birds (amniotes) [25] |

| Trait Metric | Dorsal brightness quantified as a percentage [26] | Body size (mass or linear dimension) [25] |

| Key Environmental Variables | Habitat openness, latitude, altitude, body mass [26] | Clade structure and age [25] |

| Evolutionary Rate Correlation | With foraminiferal δ18O (paleotemperature proxy) [26] | Not analyzed |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Testing Evolutionary Models in Squamate Color Brightness

This protocol outlines the methodology for analyzing the evolutionary drivers of color brightness, as employed in the global squamate study [26].

- Trait Quantification: Dorsal color brightness is measured from specimen photographs and expressed as a percentage, where 0% is pure black and 100% is pure white.

- Data Compilation: Compile a global species-level dataset integrating:

- Brightness values.

- Ecological data: habitat openness (categorical: open, closed, subterranean), latitudinal and altitudinal distribution, body mass, and circadian rhythm.

- A time-calibrated phylogeny of the studied species.

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Estimate the ancestral states of color brightness across the phylogeny using the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) model. Compare the model fit against Brownian motion (BM) and Early Burst (EB) models using metrics like the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

- Phylogenetic Signal Calculation: Compute Pagel's lambda (λ) to determine the strength of the phylogenetic signal for brightness across the entire tree and within major clades.

- Bayesian Phylogenetic Modeling: Use phylogenetic comparative methods within a Bayesian framework to evaluate the relationship between brightness and eco-environmental variables. Run models at both the order-wide and family level.

- Evolutionary Rate Analysis: Corrogate rates of brightness evolution with paleoclimatic data, specifically foraminiferal δ18O values, to test for a link between evolutionary tempo and global climate change.

Protocol 2: Detecting Nested Early Bursts in Amniote Body Size

This protocol is derived from research testing for early bursts of body size evolution within subclades of major amniote groups [25].

- Data Collection: Gather body size data (e.g., mass, snout-vent length) for a large number of species within a major clade (e.g., Mammalia, Aves, Squamata). Obtain a robust, time-calibrated phylogeny for these species.

- Model Implementation and Comparison: Fit and compare a suite of evolutionary models to the body size data and phylogeny:

- Simple Models: Brownian Motion (BM), Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU), and Early Burst (EB) applied to the entire phylogeny.

- Nested Models: Extend models to allow for a shift in the evolutionary process within a single, nested monophyletic subclade against a background BM process. Key nested models include:

- Nested Early Burst (EB)

- Nested EB with a rate scalar

- Nested OU

- Nested BM (rate shift)

- Likelihood Calculation: For the nested EB model, the variance-covariance matrix is modified so that branch lengths within the subclade are transformed by the parameter r, causing rates to decrease exponentially from the clade's origin [25]. The likelihood of the traits given the phylogeny is then calculated.

- Model Selection: Compare the fit of all models using the small-sample Akaike Information Criterion (AICc). The model with the lowest AICc is considered the best fit.

- Multi-Rate Model Testing: Compare the best-fitting single-shift models against more complex models that allow for multiple shifts in BM or OU processes across the phylogeny.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Analytical Workflow for Evolutionary Model Testing

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for testing competing evolutionary models, as applied in both case studies.

Conceptual Framework of an Early Burst Model

This diagram visualizes the core structure of a nested Early Burst model, where the evolutionary process shifts within a subclade.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Evolutionary Tempo/Mode Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Field of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Time-Calibrated Phylogeny | The essential scaffold for all analyses, providing evolutionary relationships and divergence times. | Universal |

Comparative Methods Software (e.g., R packages: geiger, phytools) |

Implements statistical models (BM, OU, EB) for analyzing trait evolution on phylogenetic trees. | Universal |

| Molecular Evolutionary Software (PAML, CODEML) | Estimates non-synonymous/synonymous substitution rates (dN/dS) to detect molecular selection pressures on genes. | Genomic Analysis [27] |

| Morphological Dataset (e.g., from fossils) | Allows for the calculation of morphological disparity (morphospace occupation) and evolutionary rates in deep time. | Paleobiology [28] |

| Paleoclimatic Proxies (e.g., δ18O data) | Serves as an independent variable to test correlations between evolutionary rates and past climatic shifts. | Macroevolution [26] |

| Genomic Databases (e.g., NCBI, Ensembl) | Sources for obtaining genomic and protein sequence data for molecular evolutionary analyses. | Genomic Analysis [27] |

A critical challenge in developing long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations is the initial burst release, a phenomenon where a significant dose of the drug is rapidly released shortly after administration [29]. This uncontrolled release can lead to local toxicity, adverse side effects from peak serum exposure, and a subsequent reduction in the long-term bioavailability of the therapeutic agent, compromising the efficacy of the entire treatment regimen [30] [31]. Burst release is particularly problematic for potent drugs, such as corticosteroids, where initial overdosing can induce significant adverse events [30].

The overarching goal of LAI formulations is to achieve sustained, controlled drug release over weeks or months, improving therapeutic efficacy, safety, and patient adherence compared to traditional daily injections [32] [33]. The presence of a substantial burst phase directly counteracts these objectives. Consequently, developing robust strategies to minimize burst is not merely a formulation refinement but a fundamental requirement for the successful clinical application of many long-acting controlled-release systems [30] [34]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various formulation strategies aimed at mitigating burst release, providing experimental data and protocols to inform research and development efforts.

Mechanisms and Challenges of Burst Release

Burst release from injectable depots, particularly those based on poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), is a complex process governed by several mechanisms. A primary cause is the rapid dissolution and diffusion of drug molecules situated on or near the surface of the delivery system, such as microspheres or implants [29]. Upon contact with the aqueous physiological environment, this surface-associated drug is released almost immediately.

The physic-chemical properties of the drug and polymer play a significant role. Unfavorable drug-polymer interactions can lead to phase separation, where the drug is not molecularly dispersed within the polymer matrix but exists as discrete crystalline domains. This incompatibility exacerbates burst release [30]. Furthermore, the inherent large surface-to-volume ratio of advanced delivery systems like electrospun fibers, while beneficial for high drug loading, can intensify the burst effect if not properly managed [30].

Finally, the hydration and erosion dynamics of the biodegradable polymer set the stage for the release profile. PLGA-based systems often exhibit complex, multiphasic release profiles, typically starting with the burst phase, potentially followed by a lag phase with minimal release, and concluding with an active erosion phase where the polymer breaks down and releases the remaining drug [34] [29]. Overcoming this initial burst is a key step toward achieving continuous, zero-order release kinetics.

Comparative Analysis of Formulation Strategies and Performance Data

Researchers have developed multiple formulation strategies to combat burst release. The following section compares key approaches, highlighting their mechanisms, experimental findings, and relative performance.

Polymer Blending Strategies