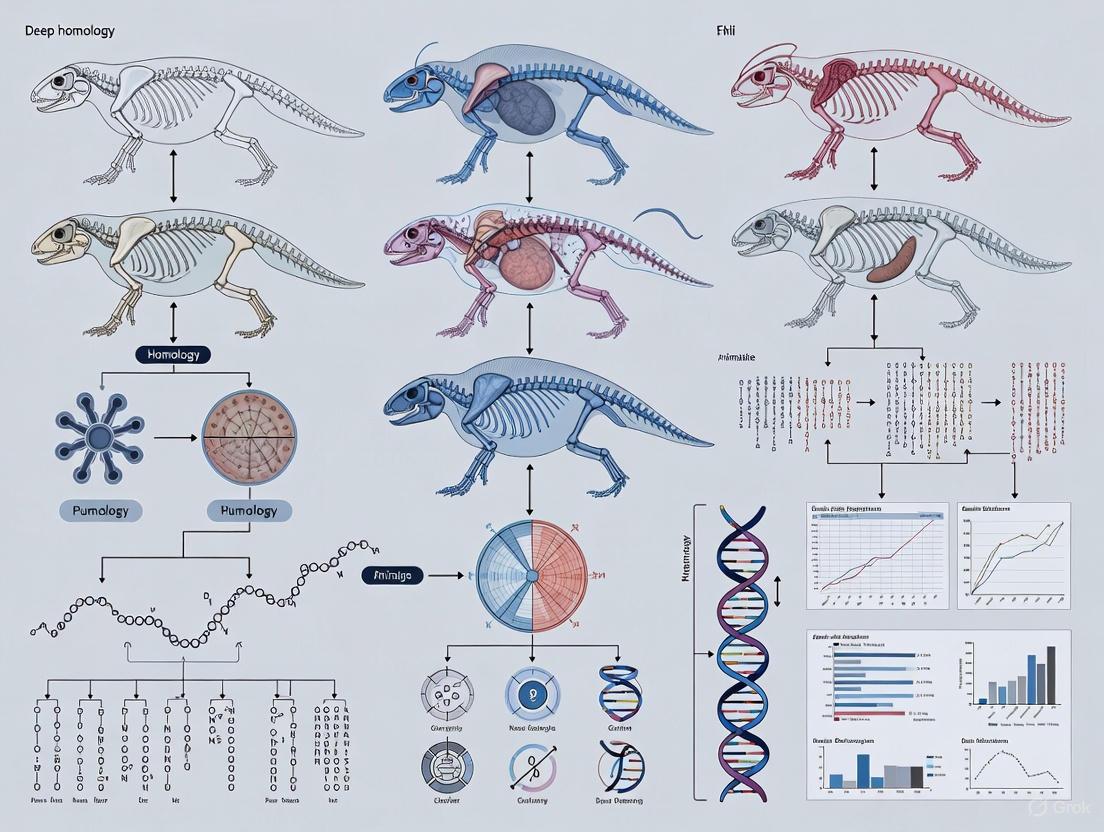

Deep Homology in Animal Design: From Evolutionary Concepts to Drug Discovery Applications

This article explores the concept of deep homology—the remarkable conservation of genetic regulatory circuits across distantly related animal species—and its profound implications for biomedical research.

Deep Homology in Animal Design: From Evolutionary Concepts to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This article explores the concept of deep homology—the remarkable conservation of genetic regulatory circuits across distantly related animal species—and its profound implications for biomedical research. We first establish the foundational principles of deep homology, tracing its origins in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) and its distinction from traditional homology. The discussion then progresses to methodological advances, including next-generation sequencing and protein language models like DHR, that enable the detection of deeply homologous systems. For the practicing researcher, we address common challenges in translating these concepts, such as animal model selection and statistical validation, providing optimization strategies. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of how deep homology informs target prioritization and structure-based drug design, validating its utility across pharmaceutical applications. This synthesis provides drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for leveraging evolutionary conservation in therapeutic innovation.

The Evolutionary Blueprint: Uncovering Deep Homology in Animal Design

Deep homology represents a foundational concept in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), describing the phenomenon where distantly related organisms share genetic regulatory apparatus used to build morphologically distinct and phylogenetically separate anatomical features. This conceptual framework has transformed our understanding of how evolutionary novelty is generated, revealing that conserved genetic toolkits are redeployed across deep evolutionary time. The intellectual journey of deep homology stretches from nineteenth-century anatomical theories to contemporary molecular genetics, creating a continuous thread in biological thought.

The significance of deep homology extends beyond academic evolutionary biology into practical biomedical applications. By revealing deeply conserved genetic pathways, it provides models for understanding human development and disease. For drug development professionals, these conserved pathways offer potential therapeutic targets and model systems for investigating disease mechanisms. This technical guide explores the conceptual, historical, and methodological evolution of deep homology, providing researchers with both theoretical framework and practical experimental approaches for contemporary investigations.

Historical Foundations: From Owen's Archetype to Darwinian Evolution

Richard Owen and the Vertebral Archetype

The intellectual precursor to deep homology emerged in the work of Victorian anatomist Sir Richard Owen (1804-1892), who introduced the concept of the archetype—a fundamental structural plan underlying anatomical diversity. In his 1848 work On the Archetype and Homologies of the Vertebrate Skeleton, Owen defined two critical anatomical relationships that would inform future homology concepts [1]:

- Homologue: "The same organ in different animals under every variety of form and function"

- Analogue: "A part or organ in one animal having the same function as another part or organ in a different animal"

Owen's vertebrate archetype represented an idealized primitive pattern—a generalized segmental design—from which all vertebrate skeletons could be derived. This Platonic conception viewed the archetype as an abstract blueprint existing in nature, with actual vertebrate skeletons representing variations on this theme [1]. His theory constituted a comprehensive synthesis of paleontology, comparative anatomy, and Christian Platonism, representing the culmination of typological thinking in biology.

Conceptual Transition to Evolutionary Homology

Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection transformed Owen's archetype from an abstract ideal to a historical ancestor—with the archetype reconceptualized as the common ancestor of the vertebrate lineage. This Darwinian reinterpretation maintained the concept of structural unity but provided a mechanistic, historical explanation rather than an idealist one.

The late 20th century saw the emergence of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), which integrated comparative embryology, molecular genetics, and evolutionary theory. This synthesis set the stage for the modern conception of deep homology by focusing on the evolutionary modifications of developmental processes [2].

Table 1: Key Historical Concepts in the Development of Deep Homology

| Concept | Key Proponent | Time Period | Core Idea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archetype | Richard Owen | 1840s | Ideal structural plan underlying anatomical diversity |

| Homology vs. Analogy | Owen | 1840s | Distinction between structural equivalence versus functional similarity |

| Descent with Modification | Charles Darwin | 1859 | Evolutionary transformation of ancestral structures |

| Genetic Toolkit | Evo-devo researchers | 1990s | Conserved genes regulating development across phylogeny |

| Deep Homology | Neil Shubin et al. | 2000s | Shared genetic regulatory apparatus underlying analogous features |

Modern Conceptual Framework: Principles and Mechanisms

Defining Deep Homology in Contemporary Terms

Deep homology extends beyond traditional morphological homology by revealing that distantly related lineages share genetic regulatory mechanisms that control the development of analogous structures. Unlike standard homology (which describes structures inherited from a common ancestor) or convergence (similar features arising independently), deep homology represents the independent co-option of homologous genetic circuits to build what become anatomically distinct features [3].

The core principle recognizes that while the morphological structures themselves may not be homologous (in the traditional sense of shared ancestry), the genetic regulatory networks that pattern their development are homologous and have been conserved over vast evolutionary time [3]. This represents a paradigm shift from comparing anatomical structures to comparing the genetic and developmental processes that generate those structures.

Mechanisms of Deep Homology

Several evolutionary mechanisms enable the conservation and redeployment of genetic toolkits across deep evolutionary distances:

- Conserved transcription factors: Regulatory proteins like Pax6, FoxP2, and Hox genes maintain their regulatory functions across animal phylogeny, despite extensive sequence divergence in target genes [3]

- Heterotopy: Spatial changes in gene expression patterns allow homologous genes to be deployed in novel developmental contexts

- Heterochrony: Temporal shifts in gene expression timing enable the modification of developmental trajectories

- Network co-option: Entire genetic modules are recruited for new developmental functions while maintaining their core regulatory logic

The molecular analysis of behavioral traits, including the role of FoxP2 in vocal learning across humans and songbirds, exemplifies how deep homology extends beyond morphology to complex behaviors [3].

Case Studies in Deep Homology: Empirical Evidence

Limb Development in Vertebrates and Insects

One of the most compelling examples of deep homology comes from the genetic regulation of appendage development across phyla. The Distal-less (Dll/Dlx) gene family, which patterns limb outgrowth in both vertebrates and insects, demonstrates how conserved genetic toolkits regulate the development of phylogenetically separate structures [3]. Despite the independent evolutionary origins of vertebrate and arthropod limbs, they share fundamental genetic patterning mechanisms.

Eye Development Across Metazoa

The Pax6 gene and its orthologs control eye development across an extraordinary phylogenetic range, from molluscs and insects to vertebrates [3]. This transcription factor operates as a master regulator of eye development, and its ectopic expression can induce eye formation in unusual body locations. The conservation of Pax6 function across 500 million years of evolution represents a classic example of deep homology, demonstrating that the genetic circuitry for complex organ systems can be maintained over immense evolutionary timescales.

FoxP2 and Vocal Learning Systems

The FoxP2 transcription factor provides a striking example of deep homology extending to neural circuits underlying behavior. FoxP2 plays crucial roles in vocal learning across humans, songbirds, and bats, shaping neural plasticity in cortico-basal ganglia circuits that underlie sensory-guided motor learning [3]. This conservation of genetic regulation for complex behavior demonstrates how deep homology operates beyond morphological structures to include neural systems and cognitive traits.

Table 2: Key Examples of Deep Homology Across Phylogeny

| Genetic Element | Taxonomic Range | Developmental Role | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pax6 | Mammals, insects, molluscs, cnidarians | Eye development | Master control of eye formation across metazoa |

| Distal-less (Dll/Dlx) | Vertebrates, insects | Limb outgrowth | Patterning of appendages despite independent origins |

| FoxP2 | Humans, songbirds, bats | Vocal learning circuits | Conservation of neural mechanisms for learned behavior |

| Hox genes | Bilaterian animals | Anterior-posterior patterning | Conserved body plan organization across animals |

| Toll-like receptors | Mammals, insects, plants | Innate immunity | Ancient pathogen recognition system |

Methodological Approaches: Experimental and Computational Tools

Experimental Protocols for Deep Homology Research

Spatial Transcriptomics and Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing Protocol

Modern investigations of deep homology employ advanced molecular profiling techniques to map conserved genetic programs. A recent study on the teleost telencephalon exemplifies this approach [4]:

- Tissue Preparation: Dissect telencephala and prepare representative 10μm coronal sections along the rostrocaudal axis

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Capture spatially resolved gene expression profiles using 10x Genomics Visium platform

- Sequence Alignment: Align RNA reads to reference genome (e.g., cichlid Maylandia zebra genome)

- Cell-Type Deconvolution: Map cell populations using algorithms like cell2location to predict anatomical distribution of cell-types identified by snRNA-seq

- Cross-Species Comparison: Compare cell-types and anatomical regions across evolutionary lineages (fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals)

This integrated approach revealed striking transcriptional similarities between cell-types in the fish telencephalon and subpallial, hippocampal, and cortical cell-types in tetrapods, providing evidence for conserved forebrain organization [4].

Computational Approaches for Detecting Deep Homology

Protein Remote Homology Detection

Advanced computational methods now enable detection of structural and functional homology even when sequence similarity is minimal:

- TM-Vec Framework: A twin neural network model that predicts structural similarity (TM-scores) directly from protein sequences, enabling identification of remote homologs based on structural conservation [5]

- DeepBLAST: A differentiable sequence alignment algorithm that performs structural alignments using protein language models, outperforming traditional sequence alignment methods for remote homology detection [5]

- Dense Homolog Retriever (DHR): An alignment-free method using protein language models and dense retrieval techniques, achieving >10% increase in sensitivity for detecting remote homologs compared to traditional methods [6]

These computational approaches are particularly valuable for annotating proteins of unknown function in metagenomic datasets, where they can identify structural homologs that would be missed by sequence-based methods alone [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Deep Homology

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Visium | Spatial transcriptomics platform | Spatially resolved gene expression profiling | Mapping conserved brain regions across species [4] |

| ProtT5 | Protein language model | Protein sequence embedding and representation | Remote homology detection and structural similarity prediction [7] |

| cell2location | Computational algorithm | Cell-type deconvolution in spatial transcriptomics data | Mapping snRNA-seq cell types to spatial locations [4] |

| TM-align | Structural alignment algorithm | Protein structure comparison and TM-score calculation | Ground truth for training deep learning models [7] |

| CATH Database | Curated protein structure database | Training and benchmarking homology detection methods | Provides structural classifications for model training [7] |

| DHR (Dense Homolog Retriever) | Retrieval framework | Ultra-fast protein homolog detection | Sensitive identification of remote homologs in large databases [6] |

| FoxP2 antibodies | Immunological reagents | Tracking protein expression across species | Comparing neural expression in vocal learning circuits [3] |

Implications and Future Directions

Implications for Biomedical Research

The principles of deep homology have significant implications for drug development and disease modeling. Conserved genetic pathways across species validate the use of model organisms for investigating human disease mechanisms. For example:

- Studies of FoxP2 in songbird vocal learning circuits provide insights into human speech disorders and autism spectrum disorders [3]

- Deep homology in brain organization, as demonstrated by conserved cell-types in the vertebrate forebrain, supports the use of fish models for investigating human neurological and psychiatric conditions [4]

- Conservation of innate immunity pathways (e.g., Toll-like receptors) across animals enables therapeutic development based on model organism studies

Technological Frontiers and Emerging Approaches

Future research in deep homology will be driven by advances in several technological domains:

- Single-cell multi-omics: Simultaneous measurement of gene expression, chromatin accessibility, and protein expression in individual cells across species

- Protein language model advancements: Improved sensitivity for detecting remote homology through models like DHR and Rprot-Vec [6] [7]

- In situ genome editing: CRISPR-based approaches to test functional conservation of regulatory elements in developing embryos across species

- Integration of paleontology and genomics: Combining fossil evidence with molecular data to reconstruct the evolutionary history of genetic toolkits

These approaches will further illuminate how evolution co-opts and modifies conserved genetic toolkits to generate both diversity and novelty in biological systems.

The concept of deep homology has undergone a substantial transformation from Owen's original conception of an abstract archetype to the modern molecular understanding of conserved genetic regulatory networks. This evolutionary developmental framework reveals that despite the remarkable diversity of biological form, a limited set of genetic tools is repeatedly redeployed throughout evolution. For researchers and drug development professionals, this principle provides both practical models for investigating human biology and a profound theoretical framework for understanding the evolutionary constraints and opportunities that shape biological systems. The continuing integration of comparative genomics, single-cell technologies, and computational methods promises to further unravel the deep homologies that underlie biological diversity.

The classical concept of homology, centered on the historical continuity of morphological structures, has been fundamentally transformed by the rise of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo). This whitepaper examines how modern frameworks—including gene regulatory network kernels, character identity networks (ChINs), and developmental constraints—provide deeper mechanistic understanding of evolutionary processes. By integrating high-throughput sequencing data and comparative transcriptomics, researchers can now identify deeply conserved genetic circuits that underlie the development of seemingly non-homologous structures across distantly related taxa. These advances reveal that "deep homology" manifests through the conservation of core developmental mechanisms rather than morphological similarity, offering new insights for evolutionary biology and novel approaches for biomedical research.

Homology, originally defined by Sir Richard Owen as "the same organ in different animals under every variety of form and function," has served as a central principle in comparative biology since the pre-Darwinian era [8]. With the advent of evolutionary theory, homology became linked to historical continuity and common descent. However, the distinction between homologous and non-homologous structures has blurred as modern evo-devo has demonstrated that novel features often arise from modification of pre-existing developmental modules rather than emerging completely de novo [8].

The recognition that distantly related species utilize remarkably conserved genetic toolkits during embryogenesis—particularly for patterning fundamental body axes—inspired a reframing of homology with focus on developmental constraints [8]. This conceptual shift led to the formulation of "deep homology," which describes remarkably conserved gene expression during the development of anatomical structures that would not be considered homologous by strict historical definitions [8]. At its core, deep homology helps conceptualize deeper layers of ontogenetic conservation for anatomical features lacking clear phylogenetic continuity.

This whitepaper explores how the integration of next-generation sequencing with conceptual frameworks of kernels, character identity networks, and developmental constraints has revolutionized our understanding of homology in the context of animal design. We examine quantitative evidence, experimental methodologies, and practical research applications that enable researchers to decipher the deep homologies shaping evolutionary trajectories.

Conceptual Frameworks: From Kernels to Character Identity

Gene Regulatory Network Kernels

The kernel concept represents a fundamental principle in the hierarchical organization of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) governing embryogenesis [8]. Kernels constitute sub-units of GRNs that occupy the top of regulatory hierarchies and exhibit specific characteristics:

- Deep evolutionary conservation: Kernels are evolutionarily ancient, often tracing back to phylum or sub-phylum levels

- Functional criticality: They are central to body plan patterning and exhibit resistance to regulatory rewiring

- Stability: Their static nature underlies the remarkable stability observed across animal body plans since the Cambrian explosion

Notable examples of kernel-like GRN conservation include endomesoderm specification in echinoderms, hindbrain regionalization in chordates, and heart development specification in arthropods and chordates [8]. Despite the structural differences between arthropod and chordate hearts, a core set of regulatory interactions directs heart development in both phyla, suggesting a common regulatory blueprint tracing back to a primitive circulatory organ at the base of the Bilateria [8].

Character Identity Networks (ChINs)

Character Identity Networks represent a slightly more flexible approach than kernels for understanding homology [9]. Introduced by Günter Wagner, ChINs refer to the historical continuity of gene regulatory networks that define character identity during development [9]. Unlike kernels, ChINs do not need to be evolutionarily ancient—they can operate at various phylogenetic levels, from phylum down to species.

Central to the ChIN concept is the inherent modularity of developmental systems, where different body parts and organs develop in a semi-autonomous fashion [8]. ChINs underlie this modularity by providing repetitive re-deployment during embryogenesis across generations, while modifications to their output result in varying character states across species [8]. This framework helps resolve conflicts between different lines of evidence, such as embryology versus paleontology, when establishing homologies between morphological characters.

A compelling application of ChIN-based approaches appears in the assessment of digit identity in avian wings. Despite reduction from a pentadactyl ground state to a three-digit formula, comparative RNA-sequencing revealed a strong transcriptional signature uniting the most anterior digits of forelimbs and hindlimbs [8]. This suggests that at the ChIN level, the most anterior digit of the avian wing shares a common developmental blueprint with its hindlimb counterpart, regardless of anatomical position.

Deep Homology and Its Implications

The term "deep homology" was originally coined to describe the repeated use of highly conserved genetic circuits in the development of anatomical features that do not share homology in a strict historical or developmental sense [8]. For example, despite evolutionary separation since the Cambrian and significant morphological divergence, the development of insect and vertebrate appendages shares striking similarities in specifying their embryonic axes [8].

Deep homology extends beyond morphological structures to behavioral traits. Research on FoxP2, a transcription factor relevant for human language, demonstrates its role in shaping neural plasticity in cortico-basal ganglia circuits underlying sensory-guided motor learning across diverse species including humans, mice, and songbirds [3]. This suggests that FoxP2 and its regulatory network may constitute part of a molecular toolkit essential for learned vocal communication, representing a case of deep homology in behavioral systems [3].

Table 1: Key Conceptual Frameworks in Modern Homology Research

| Framework | Key Characteristics | Phylogenetic Scope | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical Homology | Based on historical continuity and common descent | All levels | Vertebrate forelimbs; mammalian middle ear bones |

| Kernels | Top-level GRN components; deep conservation; refractory to rewiring | Phylum/sub-phylum level | Heart development (arthropods & chordates); endomesoderm specification |

| Character Identity Networks | Define character identity; developmental modularity; historical continuity | Phylum to species level | Digit identity in avian wings; treehopper helmets |

| Deep Homology | Conserved genetic circuits for non-homologous structures | Distantly related phyla | Appendage development (insects & vertebrates); vocal learning circuits |

Developmental Constraints and Biases

Defining Developmental Constraints

Developmental constraints represent "biases imposed on the distribution of phenotypic variation arising from the structure, character, composition or dynamics of the developmental system" [10]. These constraints collectively restrict the phenotypes that can be produced and influence the directions in which evolutionary change can more easily occur [11]. They can be categorized into three major classes:

- Physical constraints: Limitations imposed by laws of physics (diffusion, hydraulics, physical support) and structural parameters of tissues [11]

- Morphogenetic constraints: Restrictions involving morphogenetic construction rules and self-organizing mechanisms [11]

- Phyletic constraints: Historical restrictions based on the genetics of an organism's development and the need for global induction sequences [11]

A critical reappraisal of developmental constraints argues that the concept should be reframed positively—not as limitations on variation, but as the process determining which directions of morphological variation are possible [10]. From this perspective, development actively "proposes" possible morphological variants in each generation, while natural selection "disposes" of them [10].

The Developmental Hourglass Model

Evidence suggests that constraints are not uniformly distributed throughout development. The earliest developmental stages exhibit remarkable plasticity, while later stages demonstrate extensive diversification [11]. However, during the phylotypic stage—often corresponding to the period of organogenesis—a developmental "bottleneck" occurs where interactions are global and overlapping [11]. This "hourglass" model posits that:

- Early development can accommodate significant changes in morphogen distributions or cleavage planes

- Mid-development features simultaneous, global inductive events that constrain evolutionary change

- Late development consists of compartmentalized, discrete organ-forming systems that can evolve independently

This constrained middle phase of development helps explain why body plans remain stable within phyla despite variations in early and late developmental processes [11].

Table 2: Categories of Developmental Constraints with Examples

| Constraint Type | Basis | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Constraints | Laws of physics; tissue properties | No vertebrates with wheeled appendages (circulation limitations); size limitations in insects (diffusion constraints) |

| Morphogenetic Constraints | Self-organizing mechanisms; construction rules | Limited digit morphologies in vertebrate limbs (reaction-diffusion mechanisms); forbidden morphologies in salamander limbs |

| Phyletic Constraints | Historical developmental patterns; inductive sequences | Conservation of phylotypic stage across vertebrates; transient notochord requirement in vertebrate embryos |

Quantitative Analysis and Data Visualization

Transcriptomic Evidence for Deep Homology

Next-generation sequencing has revolutionized the detection of deep homology by enabling transcriptome-wide comparisons across species. Spatial transcriptomics and single-nucleus RNA-sequencing provide particularly powerful approaches for identifying conserved cell types and regulatory programs.

Research on the teleost telencephalon demonstrates how these techniques can resolve long-standing questions about evolutionary relationships. Despite the unique "everted" morphology of the teleost telencephalon, comparative analysis of cell-types across fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals uncovered striking transcriptional similarities between cell-types in the fish telencephalon and subpallial, hippocampal, and cortical cell-types in tetrapods [4]. This supports partial eversion of the teleost telencephalon and reveals deep homology in vertebrate forebrain organization.

Quantitative analysis of these datasets involves:

- Cross-species alignment of single-cell transcriptomic profiles

- Identification of orthologous cell-type markers

- Spatial mapping of conserved cell populations

- Phylogenetic comparison of gene expression patterns

Comparative Tables of Quantitative Data

Table 3: Representative Evidence for Deep Homology Across Biological Systems

| Biological System | Conserved Elements | Divergent Taxa | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Development | NKX2-5/Tinman, TBX5/20, BMP signaling | Arthropods and chordates | Gene expression patterns; knockout phenotypes; regulatory interactions [8] |

| Appendage Patterning | distal-less, homothorax, decapentaplegic/BMP | Insects and vertebrates | Gene expression during limb bud development; functional experiments [8] |

| Vocal Learning Circuits | FoxP2, cortico-basal ganglia circuitry | Humans, songbirds, bats | Gene expression patterns; RNAi knockdown; electrophysiology [3] |

| Forebrain Organization | Pallial, subpallial, hippocampal cell-types | Teleost fish and tetrapods | Single-nucleus RNA-seq; spatial transcriptomics; marker gene analysis [4] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Transcriptomic Workflows for Deep Homology Detection

The experimental detection of kernels, ChINs, and deep homology relies heavily on modern genomic and transcriptomic approaches. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for identifying deep homology through comparative transcriptomics:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for transcriptomic analysis of deep homology

Spatial Transcriptomics for Brain Evolution Studies

A specific application of these methodologies appears in research on vertebrate brain evolution. The following diagram details the integrated approach using single-nucleus RNA-sequencing and spatial transcriptomics to resolve conserved brain cell-types:

Diagram 2: Integrated spatial transcriptomics workflow for brain evolution studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Deep Homology Research

| Reagent/Platform | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Visium | Spatial transcriptomics with morphological context | Mapping cell-type distributions in everted teleost telencephalon; regional annotation of brain areas [4] |

| Single-Nucleus RNA-Seq | High-resolution cell-type classification | Identification of conserved neuronal subtypes across vertebrates; character identity network definition [4] |

| Cell2Location | Bayesian deconvolution of spatial transcriptomics | Mapping snRNA-seq cell-types to spatial coordinates; determining anatomical distributions [4] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Gene knockout and genome editing | Functional validation of kernel components; testing necessity of regulatory elements [8] |

| RNAscope/HCR | Multiplexed fluorescence in situ hybridization | Spatial validation of gene expression patterns; co-localization of network components [8] |

| Phylogenetic Footprinting | Comparative genomics for regulatory elements | Identification of conserved non-coding elements; enhancer discovery [8] |

The conceptual transition from historical homology to kernels, character identity networks, and developmental constraints represents a fundamental transformation in evolutionary biology. These frameworks recognize that deep conservation operates primarily at the level of gene regulatory networks and developmental mechanisms rather than morphological structures. The integration of next-generation sequencing technologies with comparative approaches has enabled researchers to decipher these deep homologies across diverse taxa and biological systems.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances offer new perspectives on the conservation of biological mechanisms across species. The recognition of deep homology in neural circuits, for example, validates certain animal models for studying human disorders and suggests conserved therapeutic targets. Similarly, understanding developmental constraints provides insight into the permissible versus forbidden morphological variations—knowledge with potential applications in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering.

As single-cell and spatial genomics technologies continue to advance, they will undoubtedly reveal additional examples of deep homology and provide more comprehensive understanding of the kernels and character identity networks that shape evolutionary possibilities. These insights will further bridge the gap between evolutionary theory and biomedical application, demonstrating the enduring utility of homology concepts in contemporary biological research.

The evolution of complex animal body plans is underpinned by a conserved toolkit of intercellular signaling pathways. Among these, Notch, Hedgehog (Hh), and Wnt represent foundational genetic circuits that exhibit remarkable evolutionary conservation from basal metazoans to mammals. These pathways function as central regulators of development, governing processes including cell fate determination, proliferation, and tissue patterning. Recent genomic analyses across diverse taxa have revealed that these signaling systems originated deep in metazoan evolution, with some components predating the emergence of animals altogether. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the architecture, evolutionary history, and experimental methodologies for studying these deeply homologous signaling systems, with particular relevance for researchers investigating evolutionary developmental biology and therapeutic target discovery.

The concept of deep homology describes the phenomenon whereby ancient genetic regulatory circuits are redeployed across vast evolutionary distances to build morphologically distinct structures [3]. Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt signaling pathways exemplify this principle, exhibiting conserved core architectures across the animal phylogeny despite their involvement in the development of divergent anatomical structures.

Molecular analyses reveal that these pathways likely originated before the divergence of major metazoan lineages. Surprisingly, genomic studies of choanoflagellates—the closest living relatives of animals—have identified Notch/Delta pathway components in these unicellular organisms, suggesting that some elements of these signaling systems predate animal multicellularity itself [12]. Similarly, examinations of early-branching metazoans including cnidarians, placozoans, and poriferans have revealed conserved pathway components, shedding light on the ancestral functions of these critical developmental regulators.

The Notch Signaling Pathway

Pathway Architecture and Mechanism

The Notch pathway operates via a relatively simple canonical signaling mechanism that lacks enzymatic amplification steps, making it uniquely sensitive to gene dosage effects [13]. The core signaling mechanism involves proteolytic cleavage of the Notch receptor following ligand binding, leading to translocation of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) into the nucleus where it regulates transcription of target genes.

Table 1: Core Components of the Notch Signaling Pathway

| Component Type | Mammalian Representatives | D. melanogaster Homologs | Conservation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receptors | NOTCH1, NOTCH2, NOTCH3, NOTCH4 | Notch | Conserved from cnidarians to bilaterians [14] |

| DSL Ligands | DLL1, DLL3, DLL4, JAG1, JAG2 | Delta, Serrate | Broadly conserved; Delta ligands show early diversification [14] |

| Nuclear Effector | RBPJ | Su(H) | Universally conserved |

| Co-activator | MAML | Mastermind | Lost in some lineages including myxozoans [14] |

The ligand-receptor interaction represents a critical regulatory point in Notch signaling. Notch receptors are transmembrane proteins containing multiple epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) repeats in their extracellular domain, while ligands belong to either the Delta-like (DLL) or Jagged (JAG) families [15]. A key regulatory mechanism involves cis-inhibitory interactions, where ligands and receptors expressed on the same cell membrane engage in interactions that render the receptor refractory to trans-activation from neighboring cells [13].

(Diagram 1: Core Notch signaling mechanism)

Evolutionary Conservation Across Metazoa

Comparative genomic analyses of 58 metazoan species reveal broad conservation of core Notch components, with notable losses in certain lineages including ctenophores, placozoans, and some parasitic cnidarians [14]. The canonical Notch pathway likely evolved in the common ancestor of cnidarians and bilaterians, with different lineages exhibiting distinct signaling modes.

Table 2: Notch Pathway Conservation Across Metazoan Lineages

| Lineage | Representative Organisms | Notch Receptor | Ligands | Key Pathway Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cnidaria | Nematostella vectensis, Hydra vulgaris | Present | Delta, Jagged | Non-canonical (Hes-independent) and canonical signaling modes [14] |

| Porifera | Amphimedon queenslandica | Present | Five Delta ligands | Gene duplications; role in diverse cell types [14] |

| Myxozoa | Sphaerospora molnari | Present | Reduced set | Loss of 14/28 canonical components; extreme genomic reduction [14] |

| Ctenophora | Mnemiopsis leidyi | Present | Absent | Questionable pathway functionality [14] |

In parasitic cnidarians (Myxozoa), extreme genomic reduction has resulted in the loss of approximately 50% of canonical Notch pathway components, including key elements such as MAML, Hes/Hey, and DVL [14]. Despite this reduction, the Notch receptor itself is retained and has been detected in proliferative stages of Sphaerospora molnari, suggesting maintained functionality in cellular proliferation.

Experimental Protocols for Notch Pathway Analysis

Protocol 1: Notch Signaling Inhibition Using Gamma-Secretase Inhibitors

- Compound Preparation: Prepare 100 mM DAPT (N-[N-(3,5-Difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester) stock solution in DMSO. Aliquot and store at -20°C.

- Treatment Conditions: Apply DAPT at concentrations ranging from 10-100 μM to cultured cells or embryonic specimens. Include DMSO-only controls.

- Exposure Duration: Incubate for 12-48 hours depending on model system and developmental stage.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Assess for Notch-related phenotypes including altered cell differentiation patterns, proliferation defects, or disrupted tissue boundaries.

- Validation: Confirm pathway inhibition through Western blot analysis of NICD levels or qRT-PCR of Notch target genes (Hes/Hey family).

This approach has been successfully applied in diverse systems including cnidarians (Nematostella vectensis, Hydra vulgaris), revealing conserved roles in balancing cell proliferation and differentiation [14].

Protocol 2: Immunohistochemical Localization of Notch Receptors

- Sample Fixation: Fix tissues or whole organisms in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 4-24 hours at 4°C.

- Permeabilization: Treat with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 minutes to 2 hours.

- Blocking: Incubate in blocking solution (5% normal serum, 1% BSA in PBS) for 1-2 hours.

- Primary Antibody: Apply Notch receptor-specific antibodies at empirically determined dilutions (typically 1:100-1:1000) overnight at 4°C.

- Secondary Detection: Use fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for visualization.

- Counterstaining: Include nuclear counterstains (DAPI, Hoechst) and cytoskeletal markers for context.

This protocol has been adapted for use in non-traditional model systems including myxozoans, demonstrating Notch receptor presence in proliferative cells [14].

The Hedgehog Signaling Pathway

Pathway Architecture and Evolutionary Origin

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway features a unique mechanism involving autoprocessing of the Hh precursor protein and sterol modification of the active ligand. The Hh protein is synthesized as a precursor that undergoes autocatalytic cleavage to yield an N-terminal signaling domain (hedge) and a C-terminal autoprocessing domain (hog) with intein-like properties [16].

The evolutionary origin of Hh proteins appears to involve domain shuffling early in metazoan evolution. Evidence from sponges and cnidarians reveals the existence of Hedgling—a transmembrane protein containing the Hh N-terminal signaling domain fused to cadherin, EGF, and immunoglobulin domains [17]. This finding suggests that contemporary Hh proteins likely evolved through capture of a hedge-domain by the more ancient hog-domain.

Bacterial homologs of key Hh pathway components provide clues to its deep evolutionary history. Patched (Ptc), the Hh receptor, shows homology to bacterial resistance-nodulation division (RND) transporters [18]. Specifically, a subfamily of RND transporters termed hpnN is associated with hopanoid biosynthesis in bacteria, suggesting an evolutionary connection between sterol transport and Hh signaling.

(Diagram 2: Hedgehog signaling pathway)

Evolutionary Conservation Across Metazoa

Hedgehog signaling components show a complex evolutionary pattern with multiple instances of gene loss and modification. While Drosophila contains a single Hh gene, mammalian genomes possess three paralogs (Shh, Ihh, Dhh) resulting from gene duplication events, with zebrafish exhibiting five Hh genes due to an additional genome duplication in the ray-finned fish lineage [16].

In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, a bona-fide Hh gene is absent, replaced by a series of hh-related genes (quahog, warthog, groundhog, and ground-like) that share the Hint/Hog domain but have distinct N-termini [16]. Similar hh-related genes are found in other nematodes including Brugia malayi, suggesting this represents a lineage-specific innovation.

Genomic analyses of the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis reveal six genes with relationship to Hh, including two true Hh genes and additional genes containing Hint/Hog domains with novel N-termini [16]. This diversity suggests that the evolution of hh genes occurred in parallel with the evolution of other Hog domain-containing genes in early metazoan lineages.

Experimental Protocols for Hedgehog Pathway Analysis

Protocol 1: Detection of Hh-Related Genes in Non-Model Organisms

- Sequence Retrieval: Use tblastn and blastp searches with selected Hh, WRT, QUA, GRD, and GRL protein sequences as queries against target genomes or transcriptomes.

- ORF Prediction: Correct predicted ORFs based on conserved domain structure and motif analysis, inspecting genomic sequences for additional exons or alternative splice sites.

- Domain Architecture Analysis: Identify N-terminal signal peptides, Hint/Hog domains, and associated domains using Pfam and SMART databases.

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Perform multiple sequence alignments of protein domains followed by phylogenetic analysis using Neighbor Joining and Maximum Likelihood methods.

- Functional Prediction: Analyze sequence motifs within the Hog domain (including motifs J, K, and L) to predict autoprocessing capability and potential cholesterol modification.

This approach has been successfully applied to identify hh and hh-related genes in diverse nematodes and cnidarians [16].

The Wnt Signaling Pathway

Pathway Architecture and Evolutionary Conservation

The Wnt signaling pathway represents one of the most ancient metazoan patterning systems, with evidence of a nearly complete pathway in the simplest free-living animals, placozoans [19]. Sponges, representing one of the earliest branches of metazoa, contain several Wnts and conserved pathway components including Frizzleds, Dickkopf, and Dishevelled [19].

Comparative analyses reveal striking conservation of the chromosomal order of Wnt genes across diverse phyla including cnidarians and bilaterians [19]. The cnidarian Nematostella vectensis possesses an unexpected complexity of Wnt genes, containing almost all subfamilies found in bilaterians, with these genes expressed in patterned domains along the primary body axis during embryonic development [19].

Beta-catenin, the central transcriptional effector of canonical Wnt signaling, shows deeply conserved functions. In sea anemones, beta-catenin is differentially stabilized along the oral-aboral axis, translocates into nuclei at the site of gastrulation, and specifies endoderm, indicating an evolutionarily ancient role in early pattern formation [19].

(Diagram 3: Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway)

Wnt Pathway Components Across Metazoa

Table 3: Wnt Pathway Conservation Across Metazoan Lineages

| Lineage | Representative Organisms | Wnt Genes | Conserved Components | Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placozoa | Trichoplax adhaerens | Present | Complete pathway | Pattern formation |

| Porifera | Sponges | Several Wnts | Frizzled, Dickkopf, Dishevelled | Organizational function [19] |

| Cnidaria | Nematostella vectensis | Most subfamilies | Beta-catenin, TCF | Oral-aboral axis patterning [19] |

| Cnidaria | Hydra | Multiple | Frizzled, beta-catenin, TCF, Dickkopf | Head formation, regeneration |

| Planarians | Girardia tigrina | Present | Conserved pathway | Regeneration polarity [19] |

While Wnt signaling components are conserved throughout animals, some taxa exhibit notable absences. The slime mold Dictyostelium contains Wnt pathway components including a beta-catenin homolog (aardvark) and GSK3, but lacks true Wnt genes themselves [19]. This pattern suggests that the core signaling machinery predates the evolution of the specific Wnt ligands.

Comparative Analysis of Pathway Evolution

The comparative analysis of Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt signaling pathways reveals both shared and distinct evolutionary patterns. All three pathways originated deep in metazoan history, with some components potentially predating animal multicellularity itself.

Table 4: Comparative Evolutionary Analysis of Signaling Pathways

| Feature | Notch | Hedgehog | Wnt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earliest Evidence | Choanoflagellates [12] | Cnidarians, sponges [16] [17] | Placozoans, sponges [19] |

| Pre-metazoan Ancestors | Notch/Delta in choanoflagellates [12] | Patched homologs in bacteria [18] | Beta-catenin/GSK3 in slime molds [19] |

| Key Evolutionary Mechanism | Gene duplication in vertebrates | Domain shuffling | Gene family expansion |

| Lineage-Specific Innovations | Cis-inhibitory interactions [13] | hh-related genes in nematodes [16] | Multiple losses in nematodes |

| Developmental Pleiotropy | High (cell fate decisions) [13] | High (patterning, growth) | High (axis patterning) |

A striking pattern across all three pathways is their modular evolution, with components being lost, duplicated, or co-opted in different lineages. For example, while most animals possess a functional Notch pathway, the parasitic cnidarian Myxozoa has lost approximately 50% of its core components [14]. Similarly, nematodes have lost bona-fide Hh genes while evolving novel hh-related genes with distinct N-terminal domains [16].

These pathways also exhibit varying degrees of crosstalk and integration. For instance, the Dishevelled (DVL) protein mediates Wnt-Notch crosstalk, while the gamma-secretase complex cleaves both Notch and other transmembrane proteins including amyloid precursor protein [14]. This molecular crosstalk likely reflects coordinated evolution of these regulatory systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Conserved Signaling Pathways

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Inhibitors | DAPT (gamma-secretase inhibitor), Cyclopamine (Smo inhibitor), IWP-2 (Wnt inhibitor) | Acute pathway inhibition; functional testing | Dose optimization required; potential off-target effects |

| Genetic Models | Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, Nematostella vectensis, Hydra vulgaris | Evolutionary comparisons; functional genetics | Varying genetic tractability; specialized husbandry needs |

| Genomic Resources | Transcriptomes across diverse taxa; genome sequencing databases | Phylogenetic analysis; component identification | Data quality variable; assembly completeness concerns |

| Antibodies | Notch intracellular domain, Patched, Beta-catenin, conserved pathway components | Protein localization; expression analysis | Species cross-reactivity variable; validation required |

| Transgenic Systems | GAL4/UAS (Drosophila), Cre/loxP (mammals), CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Cell-type specific manipulation; gene function analysis | Delivery method optimization; efficiency variation |

The comparative analysis of Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt signaling pathways reveals the deep evolutionary conservation of developmental genetic circuits across animal phylogeny. These pathways exemplify the principle of deep homology, whereby ancient genetic regulatory circuits are repurposed for novel developmental functions across diverse lineages.

Future research directions should include expanded genomic sampling of early-branching metazoans, particularly understudied lineages such as ctenophores and placozoans, to further resolve the ancestral state of these signaling systems. Functional studies in non-model organisms will be essential for understanding how these conserved pathways have been modified to produce diverse developmental outcomes. Additionally, the exploration of non-canonical signaling modes and pathway crosstalk in basal metazoans may reveal ancestral functions that have been obscured in more derived model systems.

From a therapeutic perspective, the deep conservation of these pathways underscores their fundamental importance in cellular regulation while also highlighting potential challenges for targeted interventions due to pleiotropic effects. Understanding the evolutionary context of pathway modifications may inform the development of more specific therapeutic approaches that target lineage-specific innovations while sparing conserved core functions.

The independent evolution of complex anatomical structures in distantly related species, such as limbs in insects and vertebrates or hearts in arthropods and chordates, has long intrigued evolutionary and developmental biologists. The concept of deep homology provides a powerful explanatory framework for these phenomena. Deep homology refers to the sharing of ancestral genetic regulatory circuits that are used to build morphologically and phylogenetically disparate structures [20]. This principle posits that new anatomical features do not typically arise de novo but rather evolve from pre-existing genetic regulatory networks established early in metazoan evolution [20] [21]. These conserved developmental kernels provide a shared toolkit that can be co-opted, modified, and elaborated upon in different lineages to generate evolutionary novelty.

This whitepaper examines two paradigmatic case studies through the lens of deep homology: limb development and heart specification. The analysis reveals that despite vast phylogenetic distances and fundamentally different anatomical organizations, insects and vertebrates utilize conserved molecular machinery for patterning their appendages. Similarly, the genetic programs underlying heart development in arthropods and chordates share common evolutionary origins. For research scientists and drug development professionals, understanding these deeply conserved mechanisms provides valuable insights into congenital disorders and reveals potential therapeutic targets that operate across multiple tissue types and organ systems.

Case Study 1: Limb Development from Insects to Vertebrates

Conserved Genetic Circuitry in Limb Patterning

Limb development proceeds through four principal phases: (1) initiation of the limb bud, (2) specification of limb pattern, (3) differentiation of tissues, and (4) shaping of the limb and its growth to adult size [22]. Remarkably, the core genetic pathways governing these processes exhibit profound conservation between insects and vertebrates, representing a classic example of deep homology.

The limb system serves as a model for pattern formation within the vertebrate body plan, with the same molecular toolkits deployed at different times and places in vertebrate embryos [22]. Genetic studies have revealed that the Hox gene family, which specifies positional identity along the anterior-posterior axis, is utilized in patterning both insect legs and vertebrate limbs. Similarly, the Distal-less (Dll) gene, first identified for its role in distal limb development in Drosophila, plays a conserved role in specifying distal structures in vertebrate appendages. The Notch signaling pathway, which regulates cell fate decisions through local cell interactions, is another deeply conserved component that patterns the joints of both arthropod and vertebrate limbs [21].

The conservation extends beyond single genes to encompass entire regulatory circuits. As Shubin and colleagues noted, animal limbs of every kind—from whale flippers and fish fins to bat wings and human arms—are "organized by a similar genetic regulatory system that may have been established in a common ancestor" [21]. This shared genetic architecture facilitates the independent evolution of diverse limb morphologies through modifications to the regulation, timing, and combinatorial use of a common developmental toolkit.

Evolutionary Dynamics and Limb Evolvability

While limbs are serially homologous structures that share a common genetic architecture, they can evolve independently when selective pressures differ between forelimbs and hindlimbs. This evolutionary independence is particularly evident in humans, whose distinctive limb proportions (long legs and short arms) represent adaptations for bipedalism [23].

Quantitative analyses of limb integration in anthropoid primates reveal how developmental constraints have been modified throughout evolution. Humans and apes exhibit significantly reduced integration between limbs (34-38% reduced) compared to quadrupedal monkeys, enabling greater independent evolvability of limb proportions [23]. This reduction in integration reflects alterations to the pleiotropic effects of genes that normally constrain limb development, allowing for the mosaic pattern of evolution observed in the hominin fossil record.

Table 1: Limb Integration Patterns in Anthropoid Primates

| Species Category | Limb Integration Strength | Homologous Element Correlation | Evolutionary Disparity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrupedal Monkeys | High | Strong (Fisher-z: 1.22-1.50) | Lower |

| Apes | Reduced (34-38% less than monkeys) | Moderate (Fisher-z: 1.00-1.08) | Intermediate |

| Humans | Reduced (34-38% less than monkeys) | Moderate (Fisher-z: 0.93) | Higher |

This evolutionary perspective has practical implications for biomedical research. The modular nature of limb development means that genetic variants or chemical perturbations can affect different limbs differently. Understanding the mechanisms that both integrate and dissociate limb development provides insights into congenital conditions that affect specific appendages while sparing others.

Experimental Approaches for Limb Development Research

The study of limb development employs sophisticated molecular, genetic, and genomic techniques. Below are key methodological approaches for investigating the deep homology of limb patterning mechanisms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Limb Development Studies

| Research Reagent | Application in Limb Development | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis | Gene knockout and functional analysis | Tissue-specific mutagenesis of Pax3/7 in neuronal development [24] |

| Electroporation | Introduction of plasmids into specific tissues | Ectopic overexpression of transcription factors [24] |

| Cis-regulatory reporter analysis | Identification of regulatory elements | Studying transcriptional regulation in neuronal networks [24] |

| Lineage tracing (e.g., Cre-Lox) | Cell fate mapping and lineage analysis | Tracing neural crest contributions [25] |

| Transcriptome analysis | Gene expression profiling | Microarray-based transcriptome of isolated neurons [24] |

Limb Patterning Conservation Across Species

Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9 Mutagenesis for Functional Gene Analysis

- sgRNA Design: Identify target sequences in genes of interest (e.g., Pax3/7) using specialized software [24].

- Electroporation: Introduce CRISPR/Cas9 constructs into dechorionated fertilized zygotes using square-wave electroporation (e.g., 6-12V, 5-10 ms pulse length) [24].

- Screening: Assess mutagenesis efficiency via PCR and sequencing of target loci.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Examine limb phenotypes using morphological assessment and molecular markers.

- Validation: Confirm specificity through rescue experiments and off-target effect assessment.

This approach enables researchers to functionally test the role of deeply conserved genes in limb development and assess whether their functions are maintained across evolutionary distant species.

Case Study 2: Heart Specification in Arthropods and Chordates

Evolutionary Origins of Cardiac Structures

The cardiovascular system has undergone substantial evolutionary modification from its origins in primitive contractile cells to the complex multi-chambered hearts of birds and mammals. The earliest contractile proteins appeared approximately 2 billion years ago during the Paleoproterozoic Era, with contractile cells eventually organizing into primitive tubes that moved fluid via peristaltic-like contractions [26]. This primitive tubular pumping structure in chordates represents the evolutionary blueprint for cardiac circulatory systems in both invertebrates and vertebrates through conserved homologies [26].

In the transition from water to land, vertebrates evolved increasingly complex cardiac structures to support higher metabolic demands. Teleost fish possess a four-chambered heart in series (sinus venosus, atrium, ventricle, and bulbus arteriosus) that supports a single circulation system [26]. With the emergence of air-breathing vertebrates, circulatory systems separated into pulmonary and systemic circuits, culminating in the fully septated, four-chambered hearts of birds and mammals that allow complete separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood [26].

Table 3: Evolutionary progression of heart structures across vertebrates

| Species Group | Heart Structure | Circulation Type | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teleost Fish | Four chambers in series | Single circulation | Sinus venosus, atrium, ventricle, bulbus arteriosus |

| Non-crocodilian Reptiles | Two atria, one partially divided ventricle | Partial separation | Blood mixing capability; shunting ability |

| Crocodilians | Two atria, two ventricles | Dual circulation with shunting | Two aortic outlets; diving adaptations |

| Birds and Mammals | Two atria, two ventricles | Complete dual circulation | Full septation; high-pressure systemic circuit |

Despite this structural diversity, the genetic and developmental foundations of heart specification reveal deep homologies between arthropods and chordates. The Tinman/Nkx2-5 gene family, first identified for its essential role in Drosophila heart development, has orthologs that play conserved roles in vertebrate cardiogenesis. Similarly, core signaling pathways including BMP, Wnt, and Notch regulate heart development across bilaterians, reflecting their ancestral roles in patterning the contractile vasculature.

Gene Regulatory Networks in Heart Development

Cardiac development is governed by evolutionarily conserved gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that exhibit modular organization. Studies in tunicates (Ciona robusta), as the sister group to vertebrates, have revealed conserved GRNs for specifying particular cardiac cell types [24]. The combinatorial and modular logic of these networks allows for a diversity of cardiac morphologies through the redeployment of conserved regulatory modules.

The GRN controlling the specification of putative Mauthner cell homologs in tunicates illustrates this modular principle. The transcription factor Pax3/7 sits atop a regulatory hierarchy that controls neuronal specification and differentiation, operating through downstream factors including Pou4, Lhx1/5, and Dmbx that regulate distinct branches of the network dedicated to different developmental tasks [24]. Homologs of these transcription factors are similarly essential for cranial neural crest specification in vertebrates, indicating deep conservation of this regulatory circuitry [24].

The modular organization of cardiac GRNs has important implications for evolutionary innovation and medical genetics. Mutations in deeply conserved components often cause severe congenital heart defects, while modifications to regulatory linkages between modules can drive evolutionary changes in heart structure without compromising core cardiac functions.

Neural Crest Contributions and Cardiac Evolution

A pivotal innovation in vertebrate heart evolution was the contribution of the cardiac neural crest, an ectodermal cell population that migrates into the pharyngeal arches and contributes to the aortic arch arteries and arterial pole of the heart [25]. First demonstrated in avian embryos through neural crest ablation experiments, this cell population gives rise to the smooth muscle of the great arteries and plays essential roles in outflow tract septation and arch artery remodeling [25].

The molecular regulation of cardiac neural crest development involves a conserved genetic program including Tbx1, haploinsufficiency of which causes DiGeorge syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome) with characteristic cardiovascular malformations [25]. The deep homology of this genetic program is evident from its conservation across vertebrates and its relationship to more primitive cell migration programs in invertebrate chordates.

Heart Development Evolutionary Pathway

Protocol: Neural Crest Lineage Tracing and Ablation

- Lineage Labeling: Use Cre-Lox technology (e.g., Wnt1-Cre or Pax3-Cre mice) to lineage label neural crest cells [25].

- Ablation Studies: Perform bilateral ablation of neural crest populations (e.g., over somites 1-3 in avian embryos) [25].

- Chimera Generation: Create quail-chick chimeras by grafting quail neural crest into host chick embryos [25].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Assess cardiovascular defects, particularly outflow tract and aortic arch malformations.

- Molecular Characterization: Analyze expression of key regulators (e.g., Tbx1) in manipulated embryos.

These experimental approaches have been instrumental in elucidating the essential contributions of neural crest cells to cardiovascular development and the deep homology of the genetic programs guiding their development.

Research Applications and Future Directions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Core Reagents and Technologies

Contemporary research into deep homology leverages an expanding toolkit of molecular, genomic, and computational technologies. The ongoing technological revolution in developmental biology is accelerating progress through advances in genomics, imaging, engineering, and computational biology [27].

Table 4: Essential research reagents for evolutionary developmental biology

| Technology/Reagent | Application | Utility for Deep Homology Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | Transcriptome profiling | Identifying conserved cell types and states across species |

| CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing | Gene functional analysis | Testing necessity and sufficiency of conserved genes |

| Live imaging and light-sheet microscopy | Dynamic morphogenesis | Comparing developmental processes across species |

| Organoid systems | In vitro modeling | Reconstituting conserved developmental programs |

| Cross-species chromatin profiling | Regulatory element identification | Discovering deeply conserved enhancers |

Implications for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

Understanding deep homology has profound implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development. The conservation of genetic programs across diverse species means that mechanistic insights gained from model organisms often translate to human biology and disease. Furthermore, the modular nature of developmental gene regulatory networks suggests that therapeutic interventions could be designed to target specific network modules without disrupting entire systems.

For drug development professionals, the deep homology concept provides a framework for prioritizing targets with evolutionarily conserved functions, which may offer broader therapeutic windows and fewer off-target effects. Additionally, understanding how developmental processes are conserved enables more predictive toxicology assessments during preclinical development.

The entrance of developmental biology into "a new golden age" driven by powerful technologies [27] promises to further illuminate the deep homologies underlying animal development. As these advances continue, they will undoubtedly reveal new opportunities for therapeutic intervention in congenital disorders and regenerative medicine approaches for damaged tissues and organs.

The concept of homology represents a foundational pillar in comparative biology, representing the relationship among characters due to common descent. Within the context of animal design research, homology operates across multiple hierarchical levels—from molecular and cellular to morphological and developmental—creating a complex framework of "sameness" that illuminates evolutionary relationships. Historically, homology was defined morphologically and explained by reference to ideal archetypes, implying design. Charles Darwin reformulated biology in naturalistic terms, explaining homology as the result of descent with modification from a common ancestor. This phylogenetic definition has since dominated evolutionary biology, though the fundamental challenge remains: how to objectively identify and validate homologies across deep evolutionary divergences where structural similarities become obscured by eons of evolutionary change [28].

The emerging field of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) has revealed that hierarchical homology operates through deeply conserved genetic and developmental pathways, often called "deep homology," where analogous structures in distantly related species share common genetic regulatory apparatus. This whitepaper synthesizes current research and methodologies for identifying homology across biological hierarchies, with particular emphasis on applications in biomedical research and drug discovery. By integrating classical morphological approaches with cutting-edge genomic technologies, researchers can now trace homological relationships across vast evolutionary distances, providing unprecedented insights into animal design principles with practical applications in human health and disease modeling.

Theoretical Foundations: From Morphology to Molecular Regulation

Historical Perspectives and Definitions

The historical development of homology concepts reveals shifting explanatory frameworks. Pre-Darwinian biologists like Richard Owen defined homology strictly morphologically as "the same organ in different animals under every variety of form and function." Darwin's revolutionary contribution was to provide a naturalistic mechanism—descent with modification—to explain these similarities. This subsequently led to a redefinition of homology in phylogenetic terms as features derived from the same feature in a common ancestor [28]. This phylogenetic definition creates a logical circularity if used to prove common ancestry, highlighting the need for independent criteria for establishing homology.

The hierarchical nature of homology becomes apparent when considering the complex relationship between genetic, developmental, and morphological levels. As noted by evolutionary biologist Leigh Van Valen, homologous features are produced during development by information that has been inherited with modification from ancestors, creating a "continuity of information" across generations [28]. This informational perspective bridges the gap between phylogenetic patterns and developmental processes, allowing homology to be traced through inherited developmental programs despite morphological diversification.

The Challenge of Deep Homology

A significant challenge in evolutionary biology involves establishing homology across deep evolutionary divergences where morphological similarities are obscured. The central problem is that high genomic evolvability and the complexity of genomic features that impact gene regulatory networks make it difficult to identify clear shared molecular signatures for homologous cell types or structures between deeply branching animal clades [29]. Complex interplay between regulatory networks during development and the transcription factor logic associated with cell types makes identifying a clear shared set of genes that identify a given cell type challenging for clades separated for hundreds of millions of years.

Table 1: Levels of Hierarchical Homology with Defining Characteristics

| Level | Defining Characteristics | Evolutionary Lability | Evidence Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic | Similar DNA sequences, syntenic relationships | Low (sequence conservation) | Genome sequencing, alignment algorithms [30] |

| Genomic Architecture | Irreversible chromosomal mixing, regulatory entanglements | Very Low (synapomorphic) | Chromosomal-scale genomes, Hi-C, synteny analysis [29] |

| Developmental | Conserved gene regulatory networks, cell lineage | Moderate (developmental system drift) | Single-cell transcriptomics, lineage tracing, CRISPR [29] |

| Cellular | Molecular signatures, ultrastructural features | Moderate-High | ImmunoFISH, proteomics, electron microscopy [31] |

| Morphological | Anatomical position, topological relationships | High (adaptive convergence) | Comparative anatomy, fossil evidence, 3D reconstruction [28] |

Genomic Approaches: Irreversible States as Homology Markers

Irreversible Genomic States as Synapomorphic Characters

A groundbreaking approach to establishing deep homologies leverages the concept of irreversible genomic states. These states occur after chromosomal and sub-chromosomal mixing of genes and regulatory elements, creating configurations that cannot revert to ancestral conditions. Similar to historical definitions of homology based on anatomical unmovable components, these genomic states provide stable reference points for tracing evolutionary relationships [29]. The key insight is that while many genomic changes can be reversed through evolution, certain configurations—particularly those involving complex rearrangements—effectively "lock in" evolutionary histories.

The most characterized form of irreversible genomic change is "fusion-with-mixing"—when two ancestrally conserved chromosomes undergo fusion, followed by intra-chromosomal translocations that mix genes from both original chromosomes. The resulting mixed chromosome cannot be reverted to the original two states comprising the two ancestral gene complements [29]. This chromosomal-scale mixing creates a powerful synapomorphic character that, once established, cannot be reverted and is expected in all descendants of that lineage. This property has been utilized to resolve previously debated phylogenetic positions where morphological or sequence-based approaches yielded conflicting results.

Sub-Chromosomal Regulatory Entanglements

Beyond chromosomal fusions, a parallel process occurs at the sub-chromosomal level through what has been termed "regulatory entanglement." Mixing of enhancer-promoter interactions within topologically associating domains (TADs) or loop structures may create configurations unlikely to be unmixed by random inversions, as these would break functional enhancer-promoter contacts [29]. These constrained genomic neighborhoods result in the retention of unrelated genes and their regulatory regions, creating irreversible genomic states that can be linked to specific cell type identities or developmental processes.

The irreversibility of this evolutionary process enables researchers to screen such states for specific changes in gene expression associated with cell type development or function. Phylogenetic dating of such regulatory entanglements and quantification of their irreversibility can indicate at what evolutionary node a novelty arose and rule out scenarios of re-ancestralization. The methodology for identifying such states is emerging, building on novel interdisciplinary applications including topological theories in macro-evolution [29]. This approach provides a fertile testing ground for deep evolutionary phenotype homology hypotheses that were previously intractable.

Experimental Methodologies for Establishing Homology

Chromosomal Organization Analysis

The investigation of homologous chromosome pairing provides a powerful experimental model for studying genomic organization. In one representative study, researchers employed immunofluorescence and DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (ImmunoFISH) with high-resolution confocal microscopy to visualize chromosomes and centrosomes in human endothelial cells [31]. The experimental workflow followed this detailed protocol:

Cell Culture and Preparation: Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) from individual donors were cultured on flamed/UV-sterilized PTFE glass slides until reaching 70-80% confluency. The specific culture medium consisted of MCDB-131 supplemented with 1% Glutamax, 1% Pen-Strep, and 2% large vessel endothelial supplement [31].

Immunofluorescence Protocol: Slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stored in 70% ethanol for at least 24 hours. After washing in cold PBS, heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed for 10 minutes in sodium citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 6.0) in a steamer. Slides were permeabilized (0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS), blocked with 10% goat serum, and incubated with primary antibody against γ-tubulin (1:1000 dilution) at 4°C overnight in a humidified chamber. Following PBS washes, slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500) for 1 hour at room temperature in darkness [31].

Chromosome Painting: Before DNA counterstaining, slides were incubated with EGS crosslinker solution (25% DMSO, 0.375% Tween-20, 25mM EGS in PBS) for 10 minutes. Whole Chromosome Paints for specific chromosomes in Aqua, Texas red, or FITC were preheated at 80°C for 10 minutes, then incubated at 37°C for 1 hour [31].

Imaging and Analysis: High-resolution confocal microscopy enabled 3D reconstruction of chromosome positions relative to centrosomes. This allowed quantification of homologous chromosome pairing frequencies by determining whether homologs resided on the same or opposite sides of the centrosome axis [31].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Chromosomal Homology Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| HAECs | Lonza Cat. No. CC-2535 (multiple donor ages) | Provides adult endothelial cells for age-related comparison studies [31] |

| γ-tubulin Antibody | abcam ab11317 (Rabbit, 1:1000 dilution) | Labels centrosomes for spatial reference in chromosome positioning [31] |

| Alexa Fluor 647 Secondary | abcam ab150079 (Goat Anti-Rabbit, 1:500) | Fluorescent detection of primary antibody for confocal imaging [31] |

| Whole Chromosome Paints | Applied Spectral Imaging (Aqua, Texas red, FITC) | Fluorescently labels specific chromosomes for visualization [31] |

| EGS Crosslinker | Thermo Scientific #21565 (25mM in PBS) | Crosslinks proteins to maintain structural integrity during FISH [31] |

Homology Modeling in Structural Biology

Homology modeling represents a computational approach to establish structural homology when experimental structures are unavailable. The process involves predicting a protein's 3D structure based on its alignment to related proteins with known structures. This method relies on the principle that structural conformation is more conserved than amino acid sequence, and small-to-medium sequence changes typically result in minimal 3D structure variation [30]. The homology modeling process consists of five key steps: (1) template identification through fold recognition; (2) single or multiple sequence alignment; (3) model building based on template 3D structure; (4) model refinement; and (5) model validation [30].

Template Recognition and Alignment: The initial step uses tools like BLAST to compare the target sequence against the Protein Data Bank (PDB). For sequences with identity below 30%, more sensitive methods like PSI-BLAST, Hidden Markov Models (HMMER, SAM), or profile-profile alignment (FFAS03) are required. Alignment accuracy is critical, as errors become the primary source of deviations in comparative modeling [30].

Model Building and Refinement: After target-template alignment, model building employs methods including rigid-body assembly, segment matching, spatial restraint satisfaction, and artificial evolution. Model refinement uses energy minimization with molecular mechanics force fields, complemented by molecular dynamics, Monte Carlo, or genetic algorithm-based sampling [30]. The accuracy of the resulting model directly correlates with sequence identity between target and template—models with >50% identity are generally accurate enough for drug discovery applications, while those with 25-50% identity may guide mutagenesis experiments [30].

Quantitative Frameworks and Data Visualization

Standards for Homology Assessment

Establishing quantitative thresholds is essential for robust homology assessment across biological hierarchies. The criteria vary significantly depending on the hierarchical level being investigated, with more stringent requirements at molecular levels where homoplasy (convergent evolution) is less likely. Current frameworks distinguish between different strengths of evidence, with genomic architectural features providing the strongest evidence due to their irreversible nature [29].

Table 3: Quantitative Thresholds for Homology Assessment Across Hierarchies

| Homology Level | Strong Evidence Threshold | Moderate Evidence | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Homology | >50% identity (structural) >70% (functional) | 25-50% identity | E-value, Bit score, Alignment coverage [30] |