Decoding Evolutionary Novelty: From Genomic Origins to Clinical Applications

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the origins of novel and complex traits, addressing a foundational challenge in evolutionary biology with profound implications for biomedical research.

Decoding Evolutionary Novelty: From Genomic Origins to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the origins of novel and complex traits, addressing a foundational challenge in evolutionary biology with profound implications for biomedical research. We explore the genetic and developmental mechanisms driving innovation—from gene co-option and regulatory changes to hybridization and constructive evolution. For a target audience of researchers and drug development professionals, the review critically assesses computational models, comparative genomics, and integrative data strategies for pinpointing causal genes. It further evaluates how evolutionary insights validate and prioritize drug targets, demonstrating that genetic evidence can more than double clinical success rates. The analysis provides a framework for troubleshooting research challenges and leveraging evolutionary principles to enhance therapeutic discovery.

What is Evolutionary Novelty? Defining the Spectrum from Repurposing to Construction

The classical concept of 'descent with modification' has provided a robust foundation for evolutionary biology since Darwin's era. However, contemporary research reveals that this framework requires expansion to fully explain the origins of novel and complex traits. While Darwin used "descent with modification" 21 times in the Origin of Species compared to a single metaphorical reference to the "Tree of Life," his focus was primarily on evolutionary mechanisms rather than merely descriptive patterns of relationship [1]. Modern evolutionary biology now integrates genomic technologies, sophisticated analytical methods, and interdisciplinary approaches to uncover principles that transcend gradual modification, including hybridization, regulatory network co-option, and evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) mechanisms.

Recent progress in addressing these fundamental questions has been driven largely by technological developments enabling omics data generation for virtually any species, combined with advanced analytical methods [2]. This technical whitepaper provides a comprehensive framework for investigating the origins of evolutionary novelty, with specific methodological protocols, data presentation standards, and visualization tools tailored for research scientists and drug development professionals. By integrating cutting-edge approaches from genomics, computational biology, and experimental models, we outline a systematic strategy for moving beyond traditional concepts to explain the emergence of biological complexity.

Contemporary Theoretical Frameworks

Beyond the Tree of Life: Rethinking Evolutionary Relationships

The traditional tree-like representation of evolutionary relationships requires substantial refinement to account for the complex mechanisms observed in modern genomics. Darwin himself appeared to have recognized limitations of the tree metaphor, noting in his notebooks that "the Tree of Life should perhaps be called the coral of life, base of branches dead; so that passages cannot be seen" [1]. This prescient observation anticipates contemporary understanding of non-vertical evolutionary processes, including:

- Lateral Gene Transfer: Widespread in prokaryotes and enriching evolutionary understanding through gene-centered perspectives [1]

- Hybridization and Introgression: Critical roles in adaptation, as demonstrated in mimetic wing patterns in Heliconius butterflies and desert adaptation in North African foxes [2]

- Endosymbiotic Gene Transfer: Major evolutionary events involving organelle genome integration into nuclear genomes

- Chromosomal Rearrangements: Structural variations such as inversions contributing to ecologically relevant traits in sunflowers, Atlantic cod, and zokors [2]

These processes create evolutionary networks characterized by cycles and complex connections that cannot be adequately represented by strictly bifurcating trees, necessitating graph-based theoretical frameworks that accommodate both vertical and horizontal evolutionary processes [1].

The Genomic Basis of Novel Trait Evolution

The emergence of novel traits represents one of the most challenging questions in evolutionary biology. Recent research has revealed multiple genetic mechanisms that generate phenotypic novelty:

- Regulatory Evolution: Changes in gene expression patterns frequently contribute to adaptation and divergence, often without altering protein-coding sequences [2]

- Gene Co-option: Existing genes deployed in new developmental contexts, as evidenced in the evolution of novel cell types in the vertebrate brain [2]

- Protein Domain Rearrangements: Structural recombination of functional protein modules creating new molecular functions

- De Novo Gene Formation: Evolution of new protein-coding genes from previously non-coding sequences

Single-cell sequencing technologies have enabled substantial progress in understanding the stepwise evolution of complex systems, such as neural systems from Placozoa to Cnidaria and Bilateria [2]. These approaches reveal how new cell types and tissues contributed to the evolution of complex organs through a combination of genetic innovation and developmental reorganization.

Table 1: Genomic Mechanisms in Novel Trait Evolution

| Mechanism | Key Example | Technical Approaches | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory evolution | Pigmentation in rock pocket mice | ATAC-seq, RNA-seq, ChIP-seq | Enables rapid phenotypic change without protein sequence alteration |

| Hybridization/introgression | Wing patterns in Heliconius butterflies | Comparative genomics, phylogenetic analysis | Transfers adaptive traits between species |

| Chromosomal rearrangements | Ecological adaptation in sunflowers | Genome assembly, population genomics | Maintains co-adapted gene complexes |

| Gene co-option | Evolution of vertebrate brain | Single-cell sequencing, comparative development | Creates novel structures from existing genetic toolkit |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Enhanced Sequence Homology Detection with Evolutionary Models

Standard homology detection tools like BLAST and profile hidden Markov models (HMMs) utilize fixed evolutionary parameters, limiting their sensitivity for identifying remote homologs. The eHMMER method enhances the widely-used profile HMM tool HMMER by integrating time-dependent evolutionary models [3]. This protocol describes the implementation of this advanced approach for detecting remote homologies that may underlie novel trait evolution.

Experimental Protocol: Enhanced Homology Detection with eHMMER

Profile HMM Construction

- Input: Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of protein or nucleotide sequences

- Build initial profile HMM using

hmmbuildwith default parameters - Calibrate the model with

hmmpressto establish significance thresholds

Evolutionary Time Parameter Optimization

- Implement the "time slider" algorithm to dynamically adjust evolutionary time parameter

- Apply maximum likelihood estimation to optimize branch length parameters within the HMM profile

- For each position in the MSA, calculate position-specific evolutionary rates using empirical Bayesian methods

Database Searching with Adaptive Parameters

- Query the target sequence database using the time-adjusted profile HMM

- Employ the Forward algorithm to calculate the full probability of the sequence given the model

- Compute E-values using extreme value distribution fitting with adjusted parameters

Benchmarking and Validation

- Test sensitivity against known remote homologs from Pfam database

- Compare performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity) against standard HMMER and BLAST

- Apply to Domains of Unknown Function (DUFs) to identify novel annotation candidates

This method has demonstrated enhanced sensitivity in detecting both remote and closely related sequences, successfully identifying novel annotation candidates within DUFs, which constitute nearly 25% of the Pfam protein domain database [3].

Population Genomic Approaches for Detecting Selection

Advanced population genetics methods provide powerful tools for identifying genomic regions under selection, which may contribute to novel adaptations. Recent theoretical advancements enable analytical estimation of the site frequency spectrum (SFS) for rare variants under arbitrary demography while allowing for recurrent mutations [3].

Experimental Protocol: Estimating Gene Constraint from Population Data

Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Input: High-coverage exome or genome sequencing data from diverse populations

- Apply standard variant calling pipeline (GATK best practices)

- Annotate loss-of-function (LoF) variants using LOFTEE or similar tools

- Stratify variants by ancestry using principal component analysis or ADMIXTURE

Demographic Model Reconstruction

- Re-calibrate demographic models for each ancestry label using the joint SFS

- Implement composite likelihood approach to estimate population size changes, migration rates, and divergence times

- Validate models using synonymous variants assumed to be evolving neutrally

Selection Coefficient Estimation

- Apply demography-aware framework to estimate per-gene selection coefficients (s_het) against heterozygous LoF variants

- Incorporate LoF misannotation rates, benefiting from LoF variants present at high frequencies at seemingly constrained genes

- Estimate that ~3% of stop gain LoFs are labeled incorrectly (gene-specific variation)

Integration with Functional Predictions

- Combine large language models trained on phylogenetic data with population genetics approach

- Obtain distribution of fitness effects for missense variants for each gene independently of LoF s_het values

- Identify genes with distorted SFS due to elevated mutation rates at LoF sites

This advanced demography-based methodology improves constraint estimates, facilitates comparison of missense and LoF mutation effects, and can identify genes under positive selection in specific contexts like spermatogonia [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Selection Detection Methods

| Method | Data Input | Statistical Approach | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOEUF (Loss-of-Function Observed/Expected Upper bound fraction) | Presence/absence of segregating variants in functional sites | Empirical percentile ranking | Intuitive metric, widely adopted | Does not use full frequency information |

| Site Frequency Spectrum (SFS) methods | Full distribution of variant frequencies | Composite likelihood, diffusion approximation | Uses more information, better power | Sensitive to demographic assumptions |

| Demography-aware framework | Polymorphisms stratified by ancestry, with calibrated demography | Analytical SFS estimation with recurrent mutation | Improved accuracy, identifies hypermutable genes | Computationally intensive |

| GeneBayes | Variant frequencies with Bayesian framework | Bayesian hierarchical model | Incorporates uncertainty in parameters | May require extensive computation |

Visualization and Computational Tools

Experimental Workflow for Evolutionary Genomics

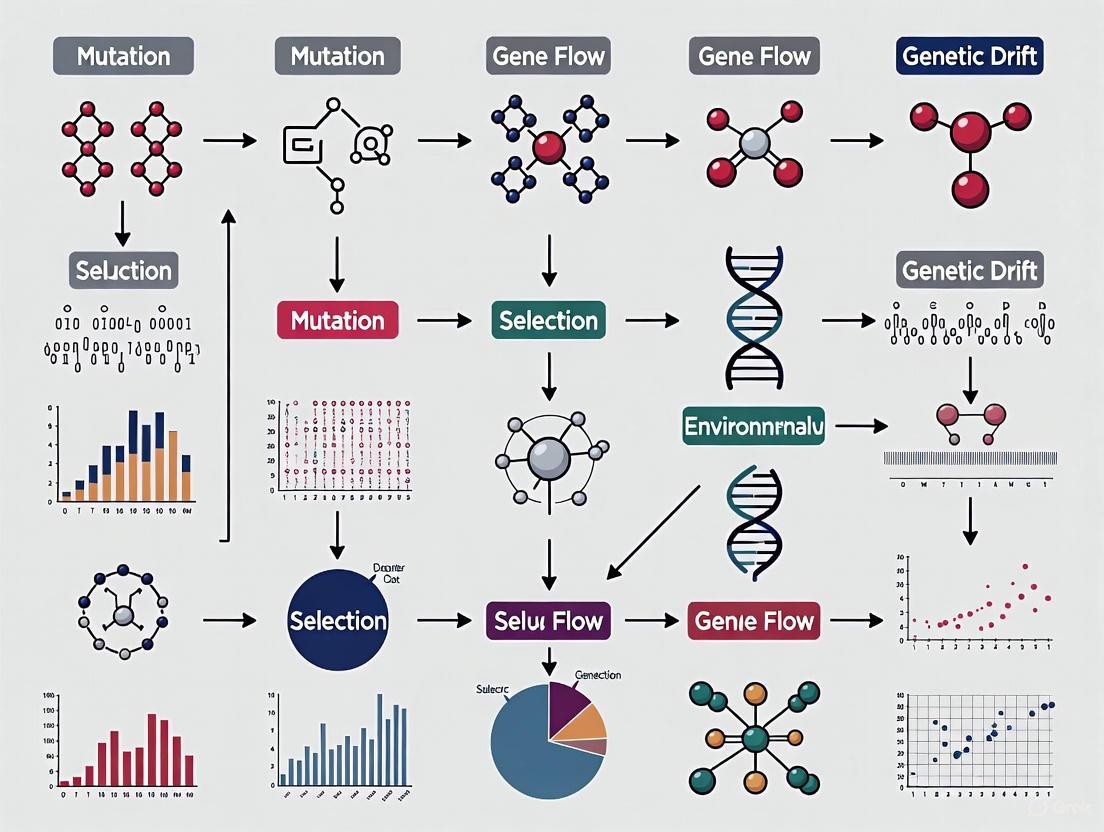

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for evolutionary genomics studies investigating novel trait origins:

Signaling Pathways in Evolutionary Adaptation

The investigation of ancient selection signals integrated with diverse genome-wide association study (GWAS), quantitative trait locus (QTL), functional, and pathway data has revealed adaptive biological processes in West Eurasian populations [3]. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways identified through this approach:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evolutionary Genomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| eHMMER software package | Enhanced homology detection with evolutionary models | Identifying remote homologs for novel traits | Time-dependent evolutionary parameters, "time slider" for branch length adjustment |

| High-coverage genome assemblies | Reference sequences for variant calling | Population genomic analysis of selection | Long-read sequencing (PacBio, Nanopore) for improved continuity |

| gnomAD v4 dataset | Population frequency reference | Constraint metric calculation | 1.46 million haploid exomes across six ancestries |

| LOFTEE (Loss-Of-Function Transcript Effect Estimator) | Annotation of high-confidence LoF variants | Filtering putative functional variants | Integrates with VEP, identifies potentially misinterpreted variants |

| Pfam protein domain database | Curated collection of protein families | Annotation of Domains of Unknown Function (DUFs) | Nearly 25% of database comprises DUFs |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing reagents | Cell-type specific expression profiling | Evolution of novel cell types in complex traits | 10X Genomics, Smart-seq2 protocols |

| Spatial transcriptomics platforms | Tissue organization and gene expression mapping | Gut immune community analysis in adaptation studies | 10X Visium, Slide-seq |

| ATAC-seq reagents | Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with high-throughput sequencing | Regulatory element identification in evolutionary adaptation | Identifies open chromatin regions in specific cell types |

Applications in Biomedical Research

Evolutionary Medicine and Therapeutic Development

Evolutionary principles provide powerful frameworks for addressing pressing biomedical challenges, particularly in infectious disease and oncology. The antibiotic resistance crisis represents fundamentally evolutionary problems, with evolutionary biology offering specific solutions including multidrug treatment approaches and the use of co-evolved phages to delay resistance evolution [2].

In oncology, evolution-informed adaptive therapy applies reduced and intermittent dosing to maintain sensitive cells in tumors rather than selecting exclusively for resistant populations. A recent study demonstrated how this approach can address drug dependence phenomena in tumors [2]. Evolutionary models have also elucidated fundamental dynamics of tumor growth and development, with analytical methodology developed in response to new molecular data [2].

Genomic Adaptation and Autoimmune Trade-offs

Ancient DNA has emerged as a powerful tool for elucidating Holocene human adaptation, with recent studies identifying hundreds of loci with genome-wide significant evidence of selection [3]. Integration of these selection signals with diverse functional genomic data reveals:

- Antagonistic Pleiotropy: Many selection loci colocalize with autoimmune disease loci, where positively-selected alleles increase disease risk [3]

- Gut Immune Adaptation: Selection signals are enriched in digestive tissue variants, particularly immune communities in gut mucosa, with positively-selected alleles associated with increased expression of key gut immune genes like MUC2 (main component of digestive mucus) and GP2 (involved in immune surveillance against bacteria) [3]

- Pathogen-Driven Selection: Multiple lines of evidence indicate selection driven by mycobacterial pathogens, with enrichment in genes causal for Mendelian Susceptibility to Mycobacterial Disease and implication of mononuclear phagocyte system cell types [3]

These findings demonstrate how adaptation to historical pathogens like M. tuberculosis may have increased genetic risk for inflammatory bowel disease during West Eurasian Holocene, illustrating the complex trade-offs in evolutionary processes [3].

Future Directions and Conceptual Challenges

The integration of evolutionary biology with functional genomics presents unprecedented opportunities to understand the origins of novel traits. Emerging approaches include:

- Single-Cell Multiomics: Combining transcriptome, epigenome, and proteome profiling at single-cell resolution to delineate evolutionary trajectories of cell types

- Spatiotemporal Gene Regulation: Mapping how three-dimensional genome architecture influences evolutionary adaptation

- Machine Learning Integration: Combining population genetics with deep learning models to predict functional consequences of genetic variation

- Cross-Species Engineering: Experimental validation of evolutionary hypotheses through genetic engineering in model and non-model organisms

These approaches will further illuminate the conceptual framework beyond 'descent with modification,' revealing the complex interplay of contingency, convergence, and constraint that shapes evolutionary outcomes. As noted in research on cytoplasmic intermediate filaments in Panarthropoda, natural replay experiments—such as ancestral loss followed by independent re-evolution—provide powerful systems for exploring the interplay between historical contingency and evolutionary convergence [3].

The continued development of analytical methods, such as expanded models of gene constraint that improve selection estimates from population data [3], will further enhance our ability to detect signatures of evolutionary processes in genomic data and understand the origins of biological novelty.

This technical guide examines the concept of between-level novelty as a fundamental mechanism for the origin of novel and complex traits in evolutionary research. Unlike traditional evolutionary models that focus on gradual accumulation of variations, between-level novelty involves the evolution of novel developmental mechanisms that dynamically transcode information across different levels of biological organization—from genotype to phenotype. This framework provides researchers and drug development professionals with a sophisticated understanding of how evolutionary processes generate developmental complexity through the repurposing of conserved genetic toolkits and the emergence of new information-processing hierarchies. We present quantitative analyses of model systems, detailed experimental methodologies, and visualizations of core concepts to equip investigators with practical tools for studying these processes in developmental and evolutionary contexts.

The emergence of novel traits represents one of the most significant yet challenging problems in evolutionary biology. Between-level novelty specifically refers to evolutionary innovations that arise through the development of novel mechanisms for transcoding biological information across predetermined levels of organization [4]. In computational models of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), this manifests when a model specifies building blocks at one level (e.g., genetic information) while selection operates at a higher level (e.g., phenotypic traits). The developmental process that maps between these levels can evolve qualitatively new mechanisms not predetermined by the modeler [4]. This perspective resolves a fundamental paradox in evolutionary modeling: how to account for genuine novelty without building predetermined outcomes into the model framework.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Between-Level Novelty

| Characteristic | Description | Evolutionary Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Information Transcoding | Dynamic translation of information between genotype and phenotype | Creates new hierarchical relationships in developmental systems |

| Developmental Scaffolding | Preexisting developmental structures facilitate novel mechanism evolution | Enables historical contingency while exploring new functional spaces |

| Mechanistic Evolution | Qualitative changes in developmental processes rather than just trait values | Explains emergence of entirely new developmental pathways |

| Multi-Level Selection | Selection operates at phenotype level while variation occurs at genotype level | Decouples mechanistic innovation from functional adaptation |

This framework moves beyond gene-centric views of evolution by emphasizing that hereditary information exists in diverse physical forms (DNA, RNA, methylation patterns, symbionts) representing a continuum of evolutionary qualities [5]. The Information Continuum Model of evolution suggests that information may migrate between these physical forms, providing a more comprehensive foundation for understanding how developmental systems generate evolutionary novelties [5].

Core Principles and Definitions

Conceptual Framework of Between-Level Novelty

Between-level novelty represents a specific category of evolutionary innovation characterized by several core principles. First, it involves the evolution of novel developmental mechanisms that effectively generate one or more levels of information transcoding between genotype and a predefined target phenotype [4]. These novel mechanisms are not themselves the direct target of selection but emerge as evolutionary byproducts of selection on higher-level phenotypic traits.

Second, between-level novelty typically involves the repurposing of existing genetic toolkits rather than the evolution of entirely new genetic components. This process of "teaching old genes new tricks" [6] demonstrates how conserved genetic circuitries can be co-opted for novel developmental functions in different contexts. The evolutionary history of gene recruitment shows remarkable flexibility, with different gene combinations being associated with morphologically similar traits across lineages [6].

Third, between-level novelty emerges through developmental scaffolding, where preexisting developmental structures, dynamics, or signaling pathways facilitate the evolution of novel mechanisms [4]. This scaffolding provides the architectural constraints and opportunities that shape the possible evolutionary trajectories of developmental systems.

Contrast with Constructive Novelty

It is essential to distinguish between-level novelty from the related concept of constructive novelty. While between-level novelty operates within predefined organizational levels, constructive novelty generates entirely new levels of biological organization by exploiting lower levels as informational scaffolds [4] [7]. For example, the evolution of multicellularity represents constructive novelty, where cellular interactions create a new organizational level (the multicellular organism) with emergent properties not present at the cellular level.

Table 2: Comparison of Novelty Types in Evolutionary Systems

| Aspect | Between-Level Novelty | Constructive Novelty |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational Levels | Works between predefined levels | Generates new organizational levels |

| Selection Target | Explicit selection on predefined phenotype | Selection on unrelated traits leads to emergence |

| Exemplary Systems | Segmentation mechanisms, pattern formation | Evolution of multicellularity, major transitions |

| Modeling Approach | Fixed genotype-phenotype mapping with evolvable mechanisms | Open-ended evolution with emergent organization |

| Information Flow | Information transcoding across levels | Information restructuring creating new levels |

This distinction is crucial for researchers because these different novelty types operate through distinct mechanistic pathways and have different implications for evolutionary theory and experimental approaches.

Model Systems and Quantitative Analyses

Evolution of Segmentation Mechanisms

The evolution of segmentation mechanisms in bilateral animals provides a compelling model for studying between-level novelty. Computational evo-devo models have demonstrated how selection for segmented body plans can lead to the evolution of diverse novel developmental mechanisms for generating repeated elements [4].

In these models, a segmented phenotype is explicitly selected for, making the segmented trait itself non-novel in the context of the model. The novelty emerges in the developmental mechanisms that evolve to generate these segments. Research has identified multiple distinct mechanistic solutions that can evolve under different developmental constraints:

Table 3: Evolved Segmentation Mechanisms in Computational Models

| Mechanism Type | Key Characteristics | Biological Analogs | Evolutionary Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous Patterning | Hierarchical mechanisms, reaction-diffusion systems, noise-amplifying mechanisms | Drosophila segmentation | Static tissue with non-moving morphogen patterns |

| Sequential Patterning | Clock-and-wavefront mechanisms, timed determination, asymmetric divisions | Vertebrate segmentation, annelid worms | Moving morphogen gradients due to decay or tissue growth |

| Oscillation-Based | Transformation of gene expression oscillations into spatial patterns | Vertebrate "somitogenesis" | Coupling of oscillatory genetic networks with growth dynamics |

These models reveal that the evolution of specific segmentation mechanisms depends largely on predetermined morphogen and growth dynamics that scaffold the evolution of novel mechanisms [4]. Simultaneous segmentation typically evolves when the tissue to be patterned is static, while sequential mechanisms more often evolve with moving morphogen gradients or tissue growth.

Butterfly Eyespots as an Empirical Model

Butterfly eyespots represent an exemplary empirical model for studying between-level novelty. These lineage-restricted traits have evolved through the recruitment of conserved developmental genes into new regulatory contexts [6]. Quantitative analyses of transcription factor expression patterns across multiple species reveal the evolutionary dynamics of gene co-option:

Table 4: Gene Expression Patterns in Butterfly Eyespot Development

| Gene | Protein Function | Expression in Nymphalinae | Expression in Satyrinae | Evolutionary History |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antennapedia (Antp) | Homeobox transcription factor | Absent from eyespot organizers | Present in early organizers | Single origin with clear evolutionary history |

| Distal-less (Dll) | Homeobox transcription factor associated with appendage formation | Variable across species | Variable across species | Multiple independent recruitment events |

| Notch (N) | Transmembrane receptor in signaling pathway | Variable across species | Variable across species | Complex pattern with homoplastic events |

| Spalt (Sal) | Zinc finger transcription factor | Present in some species | Present in some species | Flexible recruitment not correlated with morphology |

Phylogenetic reconstruction of these expression patterns reveals strikingly different evolutionary histories for each gene [6]. While Antp shows a single origin of eyespot-associated expression, the other genes display multiple independent recruitment events across butterfly phylogeny. This demonstrates that between-level novelty can involve both the coordinated recruitment of genetic networks and independent co-option of individual genes with de novo rewiring.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Characterizing Gene Expression in Novel Trait Development

Investigating between-level novelty requires experimental approaches that can identify and characterize the developmental mechanisms that transcode genetic information into novel phenotypic structures. The following protocol, adapted from eyespot development research [6], provides a methodology for tracing the evolutionary recruitment of conserved genes to novel developmental contexts:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for characterizing gene recruitment in novel traits.

Step 1: Species and Trait Selection

Select multiple species across a phylogenetic gradient that display variations of the novel trait of interest. For eyespots, researchers examined 13 butterfly species across three families (Nymphalidae, Pieridae, and Papilionidae) representing diversity in eyespot morphology and position [6]. This taxonomic breadth enables robust evolutionary inferences.

Step 2: Larval Tissue Collection

Collect last-instar larval wing discs at developmental stages preceding the morphological manifestation of the novel trait. For eyespots, this involves dissecting wing imaginal discs from fifth-instar larvae during the stage of prospective eyespot organizer establishment [6].

Step 3: Protein Immunolocalization

Process tissues for whole-mount fluorescent immunolocalization of candidate transcription factors and signaling molecules. Primary antibodies against key conserved proteins (Antp, Dll, N, Sal) are applied, followed by appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies [6]. Confocal microscopy is used to visualize expression patterns.

Step 4: Expression Pattern Documentation

Systematically document the spatial and temporal expression patterns of each protein in relation to developing novel traits. For eyespots, this involves recording which prospective pattern elements show expression of each factor during organizer establishment [6].

Step 5: Phylogenetic Analysis

Map expression patterns onto established species phylogenies using both parsimony and maximum likelihood methods to reconstruct evolutionary histories of gene recruitment [6].

Step 6: Ancestral State Reconstruction

Infer ancestral expression states at key nodes to determine whether gene recruitment events represent shared derived characters or homoplastic acquisitions [6].

Step 7: Mechanism Inference

Interpret expression pattern evolution in the context of developmental mechanism evolution, distinguishing between whole-network co-option versus independent gene recruitment with de novo rewiring.

Computational Modeling of Novelty Evolution

Computational models provide powerful tools for studying between-level novelty because they allow researchers to observe the emergence of novel developmental mechanisms in evolving digital systems:

Figure 2: Computational modeling approach for between-level novelty.

Model Implementation Protocol:

Define Evolutionary Scenario: Identify a target phenotype (e.g., segmented pattern) that will be under direct selection in the model [4].

Implement Genotype-Phenotype Map: Create a developmental model where genetic parameters influence how phenotypes emerge through simulated developmental processes. This often involves gene regulatory networks or reaction-diffusion systems [4].

Specify Selection Criteria: Implement fitness functions that reward individuals based on phenotypic outcomes rather than developmental mechanisms [4].

Run Evolutionary Simulations: Allow populations of digital organisms to evolve over thousands of generations, introducing mutations that alter developmental parameters [4].

Monitor Mechanism Emergence: Track the developmental mechanisms that evolve to produce the selected phenotypes, categorizing them based on their operational principles [4].

Analyze Evolutionary Dynamics: Examine how developmental scaffolds influence the types of mechanisms that evolve and whether certain scaffolds facilitate more evolutionary innovation [4].

Compare to Biological Systems: Compare evolved mechanisms in silico with known biological mechanisms to identify general principles of between-level novelty [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Between-Level Novelty

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies for Immunolocalization | Anti-Antp, Anti-Dll, Anti-Sal, Anti-Notch | Detecting protein expression in developing novel traits | Whole-mount compatibility crucial for 3D tissues |

| Transcriptomic Tools | RNA-seq, in situ hybridization probes, single-cell RNA-seq | Profiling gene expression associated with novel traits | Comparative approach across species enhances evolutionary insights |

| Computational Modeling Platforms | EvolDevo simulations, gene network models, reaction-diffusion systems | Testing hypotheses about mechanism evolution | Balance between biological realism and computational feasibility |

| Phylogenetic Comparative Tools | Ancestral state reconstruction, phylogenetic independent contrasts | Reconstructing evolutionary history of gene recruitment | Dense taxonomic sampling improves reconstruction accuracy |

| Genome Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas9, transgenesis approaches | Functional validation of gene roles in novel traits | Species-specific protocol development often necessary |

Discussion and Research Implications

The between-level novelty framework has significant implications for evolutionary biology, developmental genetics, and translational research. For evolutionary biologists, it provides a mechanistic explanation for how complex traits can emerge through the repurposing of existing genetic components, resolving the apparent paradox of novelty arising from conserved genetic toolkits [6]. The evidence from both computational models and empirical systems demonstrates that between-level novelty represents a distinct category of evolutionary change that cannot be fully explained by gradual accumulation of small-effect mutations [8].

For developmental geneticists, between-level novelty highlights the importance of studying gene regulatory networks and developmental mechanisms rather than focusing exclusively on individual genes. The flexible recruitment of transcription factors like Antp, Dll, and Sal to butterfly eyespots shows that evolutionary innovation often involves rewiring of regulatory connections rather than evolution of new genes [6]. This perspective encourages a more integrated approach to studying gene function in developmental evolution.

For drug development and translational research, understanding between-level novelty provides insights into how biological systems generate functional diversity through mechanism evolution. This knowledge can inform strategies for engineering novel biological functions in therapeutic contexts, such as developing cell-based therapies or tissue engineering approaches that recapitulate evolutionary innovations.

Future research directions should focus on expanding taxonomic sampling in evolutionary developmental studies, developing more sophisticated computational models that capture multiple levels of biological organization, and integrating epigenetic and environmental factors into our understanding of developmental innovation. As the field progresses, we can anticipate discovering general principles that govern the evolution of developmental mechanisms and predict conditions that foster evolutionary innovation across different biological systems.

Constructive novelty represents a paradigm-shifting concept in evolutionary biology, referring to the emergence of entirely new levels of biological organization through evolutionary processes that exploit lower levels as informational scaffolds [4]. This in-depth technical guide examines the mechanisms whereby novel traits and organizational hierarchies arise, focusing particularly on the evolutionary transition to multicellularity as a primary case study. We synthesize recent advances in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) and computational modeling that reveal how constructive novelty emerges through the repurposing of existing functions, differential modification of ancestral components, and the stepwise elaboration of proto-developmental dynamics [4] [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these principles provides powerful insights into the origins of biological complexity and offers novel frameworks for investigating disease systems and therapeutic resistance as evolutionary processes.

Constructive novelty differs fundamentally from gradual adaptation or pre-programmed variation. Rather than representing mere modifications of existing traits, it constitutes the genuine origin of new biological spaces and organizational hierarchies [4]. This phenomenon represents one of the most challenging and foundational questions in evolutionary biology—how evolution produces new and complex traits that subsequently structure entirely new evolutionary possibilities [2].

The conceptual framework distinguishes between two distinct categories of novelty:

Between-level novelty: Occurs when evolution generates novel mechanisms for transcoding biological information across predefined levels of organization, such as the evolution of novel developmental mechanisms for patterning segmented body plans [4].

Constructive novelty: Generates an entirely new level of biological organization by exploiting a lower level as an informational scaffold, thereby opening new spaces of evolutionary possibility [4]. Major evolutionary transitions, such as the evolution of multicellularity, represent quintessential examples.

This technical guide focuses primarily on constructive novelty, providing both theoretical foundations and practical experimental approaches for investigating this phenomenon, with particular relevance for researchers exploring the origins of complex biological systems.

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms

Defining Constructive Novelty

Constructive novelty arises as a side effect of selection on unrelated traits, rather than as a direct response to selective pressures for organization itself [4]. The evolved phenotype is not preconceived in the fitness function but emerges through the emergent organization of a system's basic building blocks. The result is the construction of a novel level of organization that subsequently serves as a context for further innovation [4].

This process resonates with the concept of major evolutionary transitions [4], wherein previously independent biological entities integrate to form new, higher-level individuals. However, constructive novelty extends beyond these recognized transitions to include any trait or property that opens up and structures new spaces of possible evolutionary innovation.

Contrasting Novelty Frameworks

Table 1: Comparative analysis of evolutionary novelty frameworks

| Novelty Type | Definition | Evolutionary Mechanism | Exemplary System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constructive Novelty | Generates new level of organization by exploiting lower level as informational scaffold | Emergent organization from side effects of selection on unrelated traits | Evolution of multicellularity [4] |

| Between-Level Novelty | Dynamically transcodes biological information across predefined organizational levels | Evolution of novel developmental mechanisms between genotype and phenotype | Evolution of segmentation mechanisms [4] |

| Innovation Gradient | Emerges gradually through differential modification of ancestral component parts | Repurposing, fusion, and elaboration of existing structures | Insect wing origins from ancestral structures [9] |

Computational Evo-Devo Models

Computational models of evolutionary development (evo-devo) have proven particularly valuable for studying constructive novelty because they escape a fundamental methodological paradox: if novelty is predefined in a model, then the model cannot be said to genuinely evolve novelty [4]. Evo-devo models overcome this by:

- Making genetic information (genomes, gene regulatory networks, or developmental parameters) evolvable by mutation [4]

- Allowing nonlethal mutations to accumulate and cause qualitative changes in developmental processes [4]

- Enabling these qualitative changes to emerge without being predetermined by the modeler or explicitly included in fitness functions [4]

Experimental Models and Case Studies

The Evolution of Multicellularity

The transition from unicellular to multicellular life represents a foundational example of constructive novelty. Computational models have revealed how simple physical and ecological constraints can drive this transition:

In spatially structured models where cells lived in a toxic environment, populations rapidly evolved various multicellular strategies for protecting reproductive cells by surrounding them with differentiated, toxin-degrading cells [4]. The spatial arrangement of these multicellular structures and the proto-developmental dynamics that generated them constitute constructive novelty, as they form an organizational level higher than that where the modeled fitness operates [4].

Another model examining population of cells searching for resources by chemotaxis demonstrated how cells evolved to adhere to each other, forming multicellular clusters that emerged as a novel level of organization [4]. These clusters exhibited properties not present in their individual components, including division of labor and emergent spatial patterning.

Origins of Insect Wings

The origin of insect wings represents one of the most impactful innovations in animal evolutionary history, providing a compelling case study of how novel complex traits emerge through constructive processes. Seminal work established that wings originated not as entirely new structures, but through the differential modification, fusion, and elaboration of ancestral component parts [9].

This research created "entryways to envision innovation as emerging gradually, not somehow divorced from ancestral homology, but through it" [9]. The study of beetle wings, treehopper helmets, and other structures revealed an innovation gradient connecting ancestral homology with novel traits through a gradual process of modification [9].

Experimental Evolution of Novelty

Table 2: Key experimental systems for studying constructive novelty

| Experimental System | Type of Novelty | Key Findings | Research Reagents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxin-degrading multicellular clusters [4] | Constructive novelty: Multicellularity | Evolved spatial arrangements with differentiated cell types | Spatial structured environment; Toxic compound; Cell division regulators |

| Insect wing origins [9] | Innovation gradient: Serial homology | Modification of existing structures into novel functional complexes | RNAi reagents; CRISPR-Cas9; Immunohistochemistry markers |

| Segmentation mechanisms [4] | Between-level novelty: Patterning | Evolved diverse mechanisms (simultaneous, sequential) for segmentation | Fluorescent reporter genes; Morphogen gradients; Tissue culture systems |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Computational Modeling Approaches

Computational evo-devo models provide powerful methodologies for investigating constructive novelty because they enable researchers to:

- Observe multiple events of evolutionary novelty within controlled systems [4]

- Identify properties that make for "good scaffolds" that facilitate continual novelty [4]

- Study how evolved mechanisms can be co-opted into newly evolving mechanisms in an iterative process [4]

These models typically incorporate processes at multiple spatiotemporal scales, from gene regulation and intracellular dynamics to cell movement, communication, and tissue shaping [4]. The building blocks in these models structure the developmental process, which then results in an emergent phenotype through a genotype-phenotype map [4].

Guidelines for Experimental Design

Proper experimental design is crucial for valid research on evolutionary novelty. Key considerations include:

- Systematic planning: Follow a sequenced protocol with checkpoints to ensure proper experimental design, data management, statistical analyses, and interpretation [10]

- Control of confounding variables: Identify and control for potential confounding factors that might influence results [11]

- Appropriate sample size: Ensure sufficient sample size to achieve statistical power while recognizing practical constraints [11]

- Randomization: Implement random assignment to treatment groups to minimize bias, using completely randomized or randomized block designs as appropriate [11]

Failure to maintain essential communication with statisticians in initial experimental design stages can compromise entire research programs studying evolutionary novelty [10].

Visualization and Data Representation

Effective visualization of biological data requires careful color selection to avoid overwhelming, obscuring, or biasing findings [12]. Key principles include:

- Identify data nature: Classify variables as nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio to guide color scheme selection [12]

- Select appropriate color space: Use perceptually uniform color spaces (CIE Luv, CIE Lab) that align with human color perception [12]

- Consider color blindness: Test visualizations for accessibility to color-blind viewers [13]

- Use color schemes appropriately: Employ qualitative schemes for categorical data, sequential for quantitative data ordered low to high, and diverging for deviations from a mean or zero [13]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research materials for studying constructive novelty

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Long-read sequencing | Sex chromosome discovery; Structural variation analysis | Revealing sex chromosome stability and turnover across taxa [2] |

| Single-cell sequencing | Characterizing stepwise evolution of neural systems | Tracing evolution from Placozoa to Cnidaria and Bilateria [2] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing | Functional validation of candidate genes | Testing role of specific mutations in novel trait formation |

| Phylogenomic comparative methods | Analyzing long-term biodiversity dynamics | Understanding speciation, extinction, and dispersal contributions [2] |

| Evolutionary modeling software | Predicting and understanding variant emergence | Studying vaccine escape and virulence changes in pathogens [2] |

Visualizing Constructive Novelty: Diagrams and Workflows

Conceptual Framework of Constructive Novelty

Experimental Workflow for Studying Novelty

Applications and Future Directions

Medical and Therapeutic Applications

Understanding constructive novelty has profound implications for medical science and drug development:

- Cancer evolution: Evolutionary principles inform adaptive therapy approaches using reduced, intermittent dosing to maintain sensitive cells in tumors rather than selecting for resistant populations [2]

- Antibiotic resistance: Multidrug approaches and co-evolved phages can delay resistance evolution in bacterial pathogens [2]

- Viral evolution: Predictive models of viral evolution inform vaccine development and public health strategies [2]

These applications demonstrate how evolutionary principles developed to explain constructive novelty in natural systems can be applied to manage evolutionary processes in medical contexts.

Emerging Research Frontiers

Future research on constructive novelty will likely focus on:

- Identifying scaffold properties: Determining what makes certain structures or processes effective "scaffolds" for facilitating continual novelty [4]

- Multi-scale modeling: Developing models that simulate multiple events of evolutionary novelty across different organizational levels [4]

- Integration with new technologies: Combining single-cell sequencing, CRISPR screening, and computational modeling to dissect novelty mechanisms [2]

- Predictive framework development: Creating theoretical frameworks that can predict where and how constructive novelty might emerge in evolutionary systems

The field of computational evo-devo is particularly well-positioned to reveal exciting new mechanisms for the evolution of novelty, potentially leading to a broader theory of evolutionary novelty in the near future [4].

Constructive novelty represents a fundamental mechanism whereby evolution generates new levels of biological organization, moving beyond mere adaptation to create entirely new spaces of evolutionary possibility. Through processes such as the repurposing of existing functions, emergent organization from simple interactions, and the stepwise elaboration of ancestral components, evolution constructs novelty that subsequently structures future innovation.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these principles provides powerful frameworks for investigating everything from the origins of biological complexity to the evolutionary dynamics of disease. As research methodologies advance, particularly in computational modeling and high-resolution molecular analysis, our capacity to dissect and understand constructive novelty will continue to grow, offering new insights into one of evolution's most creative processes.

The origin of insect wings represents one of evolutionary biology's most enduring and illuminating puzzles, providing a premier case study for understanding the origins of novel complex traits. For over a century, biologists have debated whether wings emerged as entirely new structures or evolved through modification of existing anatomical features. This question strikes at the heart of how major evolutionary innovations arise—whether through sudden leaps of genetic novelty or via the gradual transformation of ancestral structures. The resolution of this debate, emerging from recent integration of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) and paleontological evidence, offers a powerful framework for conceptualizing the origin of novel traits across metazoans, with potential implications even for understanding disease origins and developmental pathways in biomedical contexts.

This case study examines how insect wings evolved, the methodological approaches that resolved this long-standing question, and the conceptual implications for understanding the emergence of novel biological structures. The evidence demonstrates that evolutionary novelty rarely represents complete breaks from ancestral organization but rather emerges through the co-option and reorganization of existing genetic and developmental toolkits.

Historical Debate: Competing Hypotheses for Wing Origins

The scientific debate over insect wing origins has centered on two primary competing hypotheses, each with distinct predictions about the nature of evolutionary innovation.

The Paranotal Hypothesis: Novel Outgrowths

First formally proposed by Crampton in 1916, the paranotal hypothesis suggests that wings originated as novel outgrowths from the dorsal body wall (tergum) [14]. This theory posits that lateral extensions of the thoracic terga gradually enlarged in ancestral insects, initially serving functions such as thermoregulation or camouflage before being co-opted for aerodynamic purposes. Under this model, wings would represent true evolutionary novelties without direct homologues in ancestral appendages. Supporters pointed to the existence of broad, flattened thoracic paranotal lobes in some fossil insects as potential intermediate stages.

The Appendicular Hypothesis: Modified Leg Segments

In contrast, the appendicular hypothesis proposes that wings evolved from pre-existing appendicular structures, specifically from movable gill plates or lobes present on the basal segments of ancestral arthropod legs [15] [16]. This view, with versions dating back to the late 19th century, suggests that these structures were already present in aquatic arthropod ancestors where they functioned as respiratory organs or swimming paddles [17]. As ancestral hexapods transitioned to terrestrial habitats, these pre-existing lateral leg lobes were incorporated into the body wall and subsequently elaborated into wings. This hypothesis implies deep homology between insect wings and crustacean leg segments.

Molecular Resolution: Genetic Evidence for a Dual Origin

The resolution to this century-old debate began to emerge through the application of modern genetic and developmental techniques, which revealed unexpected complexity in wing origins.

The Role of Wing-Patterning Genes

Critical insights came from investigating the expression and function of key wing-patterning genes in both insects and crustaceans. Seminal work by Averof and Cohen in 1997 demonstrated that crustacean homologues of two genes with wing-specific functions in insects—pdm (nubbin) and apterous—were expressed in developing gill-like branches of crustacean appendages [15] [16]. This finding provided the first molecular evidence supporting the structural homology between insect wings and crustacean gill branches, suggesting that the genetic machinery for wing development predated the origin of insects themselves.

The Dual-Origin Hypothesis

Recent research using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing has revealed a more complex picture. Studies conducted independently by Bruce and Patel and by Tomoyasu and Clark-Hachtel converged on a dual-origin hypothesis—that insect wings derive from both tergal (body wall) and pleural (leg-derived) tissues [18] [19].

Bruce's work with Parhyale crustaceans and red flour beetles demonstrated that the seventh leg segment in crustaceans corresponds to insect pleura, while an eighth leg segment found in ancestral arthropods corresponds to part of the insect tergum [18] [19]. Fluorescent tagging of the wing-development gene vestigial revealed expression in this incorporated eighth leg segment in both crustaceans and insects, suggesting this tergal tissue contributed to wing evolution.

Simultaneously, Tomoyasu's group found that knocking out wing-development genes impaired development of both the crustacean tergal plate and lobed outgrowths on the seventh leg segment (homologous to insect pleura) [18]. This supported the idea that a gene network similar to the insect wing-development network "operates both in the crustacean terga and in the proximal leg segments" [18], indicating multiple tissue contributions.

Table 1: Key Genetic Evidence Supporting the Dual-Origin Hypothesis

| Gene/Technique | Organism | Experimental Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| pdm (nubbin) & apterous | Crustaceans & insects | Expression in crustacean gill branches and insect wings | Shared genetic program supports homology [15] [16] |

| vestigial CRISPR knockout | Parhyale crustaceans & Tribolium beetles | Impaired development of tergal plate and pleural lobes | Both tergal and pleural tissues contribute to wing formation [18] |

| Fluorescent vestigial tagging | Parhyale & Tribolium | Expression in incorporated eighth leg segment (tergum) | Tergal tissue is primary contributor to wing tissue [18] |

| Leg patterning gene analysis | Parhyale & insects | Correspondence of 6 distal leg segments, incorporation of proximal segments | Proximal leg segments incorporated into insect body wall [19] |

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Tracing Evolutionary Origins

Resolving the wing origin debate required innovative experimental approaches that integrated comparative developmental genetics with functional manipulation.

Comparative Gene Expression Analysis

Initial evidence came from comparative gene expression studies that examined the developmental localization of transcripts for key patterning genes across arthropod species. This approach revealed that genes specifically involved in wing development in insects had homologous expression patterns in particular regions of crustacean appendages, suggesting deep evolutionary relationships between these structures.

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

The most definitive insights came from the application of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to systematically disrupt leg-patterning and wing-patterning genes in both crustacean and insect models [18] [19]. By knocking out genes such as vestigial and observing the effects on developing appendages in species like Parhyale hawaiensis and Tribolium castaneum, researchers could test hypotheses about structural homology. This functional approach allowed for direct experimental manipulation rather than relying solely on correlation.

Fossil and Comparative Morphology Integration

Complementary to molecular approaches, analysis of Paleozoic fossils has confirmed the presence of thoracic and abdominal lateral body outgrowths that represent transitional wing precursors, suggesting their possible role as respiratory organs in aquatic or semiaquatic environments before being co-opted for flight [17]. This paleontological evidence provides critical temporal context for the sequence of morphological changes.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for resolving wing origins. The conceptual progression from historical hypotheses to molecular resolution through integrated methodologies.

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Model Systems

Key advances in understanding wing origins relied on a specific set of model organisms and research reagents that enabled comparative evolutionary developmental biology.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Model Systems for Studying Wing Origins

| Reagent/Organism | Type | Key Features & Utility | Experimental Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parhyale hawaiensis | Crustacean model | Genetically tractable crustacean; clearly segmented appendages | CRISPR editing of leg patterning genes; comparative development [18] [19] |

| Tribolium castaneum (red flour beetle) | Insect model | Basal insect with conserved development; amenable to genetic manipulation | Functional tests of wing serial homologs; gene expression analysis [14] [18] |

| Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) | Insect model | Extensive genetic toolkit; well-characterized wing development | Benchmark for wing gene networks; comparison to crustacean patterns [20] |

| Oncopeltus fasciatus (milkweed bug) | Insect model | Hemimetabolous development; more ancestral development pattern | Testing conservation of wing gene networks beyond holometabolous insects [18] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 system | Gene editing tool | Precise genome editing across species | Functional knockout of leg and wing patterning genes [18] [19] |

| vestigial, nubbin, apterous | Genetic markers | Wing-specific patterning genes | Tracing evolutionary homology through expression patterns [15] [16] [18] |

Conceptual Implications: Rethinking Evolutionary Novelty

The resolution of the insect wing origin debate has profound implications for how we conceptualize evolutionary innovation more broadly.

The Innovation Gradient

The dual-origin hypothesis supports the concept of an "innovation gradient" connecting descent with modification to the initiation and elaboration of novel traits [14]. Rather than emerging de novo, wings appear to have arisen through the differential modification, fusion, and elaboration of ancestral component parts. This framework rejects the false dichotomy between purely novel structures and modified homologs, instead proposing a continuum where novelty emerges through the recombination and specialization of existing genetic and developmental resources.

As articulated by Moczek (2025), this perspective suggests that "evo devo would do well to once and for all let go of the notion that morphological novelty must somehow emerge or exist in the absence of ancestral homologies, and that we instead should focus our attention on how ancestral homologies scaffold and bias the exploration of morphological novelty" [14].

Serial Homology and Body Wall Evolution

The recognition that insect wings evolved from both tergal and pleural tissues underscores the importance of serial homology in evolutionary innovation. The same foundational tissues that gave rise to wings on the second and third thoracic segments have been co-opted to produce a diversity of other structures in different body regions, including prothoracic horns in dung beetles, gin traps in red flour beetles, and treehopper helmets [14]. This highlights how the same developmental modules can be repurposed across segments and contexts, providing a flexible substrate for evolutionary diversification.

Diagram 2: Evolutionary transition from aquatic arthropod to flying insect. The sequential steps in the origin of insect wings through incorporation and modification of ancestral structures.

Future Directions and Research Applications

The paradigm established by insect wing origins continues to generate productive research avenues with potential applications across evolutionary biology and beyond.

Unresolved Questions and Emerging Approaches

While the dual-origin hypothesis has gained significant support, important questions remain regarding the relative contributions of different tissue sources and the exact sequence of evolutionary changes. Tomoyasu notes that "there seem to be additional contributions from other tissues" and suggests "there may be three distinct contributors" [18]. Future research integrating more detailed paleontological evidence with comparative genomics across diverse arthropod lineages will help refine our understanding of these contributions.

Implications for Understanding Other Novel Structures

The conceptual framework developed through studying insect wings—that novelty emerges through the recombination and specialization of existing developmental resources—provides a powerful lens for investigating other evolutionary innovations. Similar approaches are being applied to understand the origin of eyes, placenta, and other complex traits [9], with potential implications for understanding the assembly of biological complexity more generally.

For biomedical researchers, this paradigm offers insights into how novel pathological structures or disease states might emerge through the reorganization of existing developmental pathways. The principles of how ancestral components can be repurposed for new functions has parallels in understanding disease mechanisms and evolutionary constraints on pathological development.

The evolutionary origin of insect wings provides a compelling case study of how major innovations emerge not through sudden breaks with ancestral organization, but through the gradual modification, recombination, and specialization of existing structures and genetic toolkits. The resolution of this long-standing debate through integrated molecular, developmental, and paleontological approaches demonstrates the power of interdisciplinary research for addressing fundamental biological questions.

The emerging paradigm suggests that evolutionary novelty operates along an "innovation gradient" [14], where truly new capabilities emerge through the transformation of ancestral homologies rather than their abandonment. This framework has implications not only for understanding the history of life but also for conceptualizing how new biological functions can emerge from existing components—a principle with relevance from evolutionary biology to biomedical science.

As Patel summarizes, "People get very excited by the idea that something like insect wings may have been a novel innovation of evolution. But one of the stories that is emerging from genomic comparisons is that nothing is brand new; everything came from somewhere. And you can, in fact, figure out from where" [19].

Toolkit for Discovery: Genomic and Modeling Approaches to Decipher Novel Traits

{# The Challenge of Novelty in Evolution}

A central challenge in evolutionary biology is explaining the origins of novel and complex traits. The Modern Synthesis, while powerful, often struggles to fully account for the rapid emergence of such phenotypic innovations. Evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) has illuminated how changes in developmental gene regulation can generate morphological diversity, yet the precise mechanisms enabling biological systems to explore genetic "pre-adaptations" remain a subject of intense research [21].

Computational models are now providing a bridge between these fields by simulating the profound interplay between evolution and development. These models treat a biological design not as a final product, but as a starting point in a lineage of possibilities [22]. This perspective introduces the concept of the evotype—the set of evolutionary dispositions of a designed biosystem that captures its potential for future evolutionary change [22]. By simulating populations across generations, these computational approaches allow researchers to observe the unfolding of evolutionary potential in silico, directly addressing the question of how the unforeseen emerges from pre-existing genetic architectures.

{# Core Principles of the Evotype}

The engineering theory of evolution proposes the "evotype" as a framework for understanding and engineering evolutionary potential [22]. The evotype is composed of three interacting components that determine a system's evolutionary future, summarized in the table below.

| Component | Description | Engineering Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Variation Operator Set [22] | The full set of biochemical and physical processes (e.g., point mutations, algorithmic mutations, recombination) that can generate genetic variation, each with an associated probability. | Design mutation rates and biases to steer exploration toward desired phenotypes. |

| Genotype-Phenotype Map [21] | The regulatory and developmental system that translates a given genotype into its resulting phenotype; modularity and pleiotropy within this map are key. | Engineer networks for robustness or specific evolvability, minimizing deleterious pleiotropic effects. |

| Selection Landscape [22] | The combined action of natural and artificial selection that evaluates phenotypes. The landscape's structure is shaped by the environment and engineering objectives. | Sculpt a fitness landscape where desired functions coincide with high fitness, ensuring evolutionary stability or guiding adaptation. |

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these three core components and the overall evolutionary disposition of a system—its evotype.

Engineers can aim for two primary goals by manipulating these components:

- Evolutionary Stability: Sculpting the evotype so that a system's function changes as little as possible despite ongoing evolution [22].

- Specific Evolvability: Designing the evotype so the system can readily evolve new, pre-specified classes of phenotypes in a reasonable time frame [22].

{# Quantitative Insights from Large-Scale Mapping}

The theoretical principles of the evotype are supported by empirical data from large-scale genetic mapping studies. These studies reveal the molecular-level complexity that computational models must capture.

A high-resolution study in diploid yeast quantified the contributions of 3,394 causal genetic variants (QTNs) to 90 growth traits [23]. The results demonstrate that the potential for trait variation is vast and arises from diverse mechanisms, as shown in the following table.

| Variant Type | Key Molecular Feature | Contribution to Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Missense [23] | Amino acid substitutions with lower BLOSUM62 scores (more perturbative). | Largest average effect sizes, though effect is context-dependent. |

| Synonymous [23] | Single-nucleotide changes in coding sequence that do not alter the amino acid. | Overlapping effect-size distribution with missense variants; can significantly alter phenotype. |

| Extrageneic/Regulatory [23] | Variants in non-coding, regulatory regions of the genome. | Effect sizes comparable to synonymous variants; distinct molecular signature. |

| Highly Pleiotropic [23] | Often alter disordered sequences within signaling hubs. | Effects correlate across environments, suggesting large fitness gains come with concomitant costs. |

These findings challenge the notion that quantitative traits are "omnigenic"—influenced by essentially all genes. Instead, with sufficient statistical power, traits can be resolved into a finite set of genetic determinants, providing a concrete basis for modeling the variation component of the evotype [23].

{# A Workflow for Integrated Analysis}

To connect evo-devo genetics with ecology and translate genotype to fitness, a robust, interdisciplinary workflow is required. The following diagram outlines a generalized protocol for such an integrated analysis, synthesizing principles from successful case studies [21].

Key Phases of the Workflow:

- Field Observation: Identify a trait of interest with a clear ecological context and hypothesized adaptive value (e.g., armor plate reduction in freshwater sticklebacks) [21].

- Genetic Mapping: Use quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping in crosses or genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in wild populations to identify genomic regions associated with the trait. High-resolution mapping can resolve regions to quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs) [21] [23].

- Functional Analysis: Perform molecular biology and developmental genetics experiments (e.g., gene expression analysis, CRISPR-Cas9 editing) to confirm the function of candidate genes and understand their role in the developmental pathway [21].

- Fitness Validation: Conduct manipulative field experiments to test the adaptive significance of the trait and its genetic basis. This is a critical step for confirming the agent of selection [21].

- Computational Integration: Synthesize all data into computational evo-devo models. These models can simulate how the identified genetic variation, processed through development, responds to environmental selection over evolutionary time.

{# The Scientist's Toolkit}

Executing the research workflow requires a suite of specific reagents, data resources, and computational tools. The following table details essential components of the research toolkit.

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Computational Evo-Devo |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Inbred Line (RIL) Panels [24] [23] | A population of genetically distinct, inbred lines derived from two or more parental strains, enabling high-resolution genetic mapping. | Provides the power to detect QTLs of small effect and resolve them to single nucleotides (QTNs), defining the "variation operator set" [23]. |

| High-Throughput Phenotyping [23] | Automated, precise measurement of growth, morphology, or other quantitative traits across multiple environments and time points. | Generates the high-dimensional phenotypic data needed to model complex genotype-phenotype maps and gene-by-environment interactions [23]. |

| Public Data Repositories (e.g., NCBI, EBI, DDBJ) [25] | Centralized databases for depositing and accessing genomic, transcriptomic, and other 'omics data. | Essential for acquiring benchmark datasets, conducting secondary analyses, and building upon community resources for model parameterization and validation [25]. |

| Benchmarking Platforms & Protocols [26] | A standardized framework and set of guidelines for comparing the performance of different computational methods using well-characterized datasets. | Critical for objectively evaluating the performance, robustness, and generalizability of different computational evo-devo models and inference algorithms [26]. |

{# Future Directions and Ethical Considerations}

As computational evo-devo models become more powerful and are applied to engineer biological systems, new frontiers and responsibilities emerge. A primary challenge is the transition from reading to writing evolutionary potential. This involves actively designing biosystems with specified evotypes—for instance, creating genetic circuits with built-in "evolutionary fuses" or biases that make them robust or guide them toward a limited set of useful functions [22].

This power necessitates a parallel focus on ethical foresight. Engineered biological systems, once released into complex environments, continue to evolve in ways that can be difficult to predict fully [22]. A deep, theoretical understanding of how synthetic systems evolve post-deployment is a moral imperative to avoid unintended ecological consequences [22]. The evotype framework provides a structured way to reason about these potential futures, forcing a consideration of a biosystem's long-term evolutionary trajectory, not just its immediate function.

Integrative genomics represents a transformative approach in biomedical research, bridging the gap between genetic variation and organismal phenotypes through the comprehensive analysis of multi-omics data. This paradigm leverages naturally occurring DNA variation alongside high-throughput molecular profiling to dissect the complex architecture of disease and drug response traits [27]. The core premise of integrative genomics is that genetic variants underlying a given phenotype often perturb the expression or function of hundreds of genes in related pathways, creating molecular networks that can be systematically mapped and analyzed [27]. This approach has proven particularly powerful for elucidating the origins of novel and complex traits in evolutionary research, where it provides a mechanistic bridge connecting ancestral homology to evolutionary innovation through the gradual modification and elaboration of ancestral genetic components [9].

The fundamental challenge in evolutionary biology lies in understanding how developmental systems transform to yield novel complex structures such as eyes, limbs, or insect wings [9]. Integrative genomics addresses this challenge by moving beyond simple genotype-phenotype correlations to model the complete causal chain from DNA variation through molecular and cellular networks to organismal traits. By treating molecular phenotypes as intermediate layers between genotype and classical phenotypes, researchers can reconstruct the genetic networks associated with trait variation and identify key drivers of evolutionary innovation [27]. This review examines the methodologies, applications, and tools of integrative genomics, with particular emphasis on its power to reveal how novel complex traits emerge through the differential modification of ancestral genetic programs.

Core Principles and Methodological Framework

Theoretical Foundation: From Genetic Variation to Phenotypic Diversity

Integrative genomics operates on several key principles that distinguish it from traditional genetic approaches. First, it recognizes that complex traits are typically driven by many genes operating in multiple pathways that interact with environmental factors [27]. Second, it acknowledges that DNA sequence variations influence phenotypic variation primarily through their effects on molecular intermediate phenotypes such as gene expression, protein abundance, and metabolite levels [28]. Third, it utilizes the perturbations caused by naturally occurring genetic variation in experimental or human populations to infer causal relationships among genes and between genes and higher-order traits [27].

The approach is fundamentally data-driven, relying on the simultaneous measurement of hundreds of thousands of molecular phenotypes to capture the functional state of biological systems [27]. Studies in model organisms have demonstrated the pervasiveness of phenotypic diversity at the molecular level, with more than 50% of measured transcript, protein, metabolite, and morphological traits showing significant variation across genetically diverse strains [28]. This variation forms a densely connected network structure, with the majority of traits significantly correlated with multiple other phenotypes, revealing the complex interdependencies within biological systems [28].

Key Analytical Strategies

Several analytical strategies form the backbone of integrative genomics research. Expression Quantitative Trait Locus (eQTL) mapping identifies genetic variants that influence gene expression levels, distinguishing between cis-acting variants (located near the gene itself) and trans-acting variants (located elsewhere in the genome) [27]. Genetic correlation network analysis examines the correlation structure among molecular phenotypes to identify coordinated biological processes and pathways [28]. Causal inference methods leverage the natural randomization created by meiotic recombination to determine directional relationships between molecular traits and organismal phenotypes [27]. Systems genetics integrates these approaches to reconstruct comprehensive networks linking genetic variation to clinical endpoints through molecular intermediate phenotypes [27].

Table 1: Key Analytical Methods in Integrative Genomics

| Method | Primary Function | Data Requirements | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| QTL Mapping | Identifies genomic regions associated with trait variation | Genotype data + phenotypic measurements | Loci explaining trait variance |

| eQTL Analysis | Maps genetic variants that regulate gene expression | Genotypes + transcriptome data | cis- and trans-regulatory loci |

| Network Reconstruction | Models relationships between molecular traits | Multiple molecular profiling datasets | Correlation and causal networks |

| Causal Inference | Determines directionality in trait relationships | Genotype + multiple phenotypic datasets | Prioritized candidate drivers |

Experimental Design and Workflow

Study Population Design

Effective integrative genomics requires carefully designed study populations that capture sufficient genetic and phenotypic diversity. Two primary population designs are commonly employed. Genetic reference populations consist of standardized, genetically diverse strains that have been extensively characterized, such as the Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in a seminal phenomics study that measured over 14,000 molecular and morphological traits across 22 genetically diverse isolates [28]. Segregating populations (e.g., F2 crosses, recombinant inbred lines, or advanced intercross lines) introduce additional recombination events that enhance mapping resolution [27].