Decoding Developmental Blueprints: A Guide to Single-Cell Multi-Omics GRN Inference for Evolutionary Insights and Disease

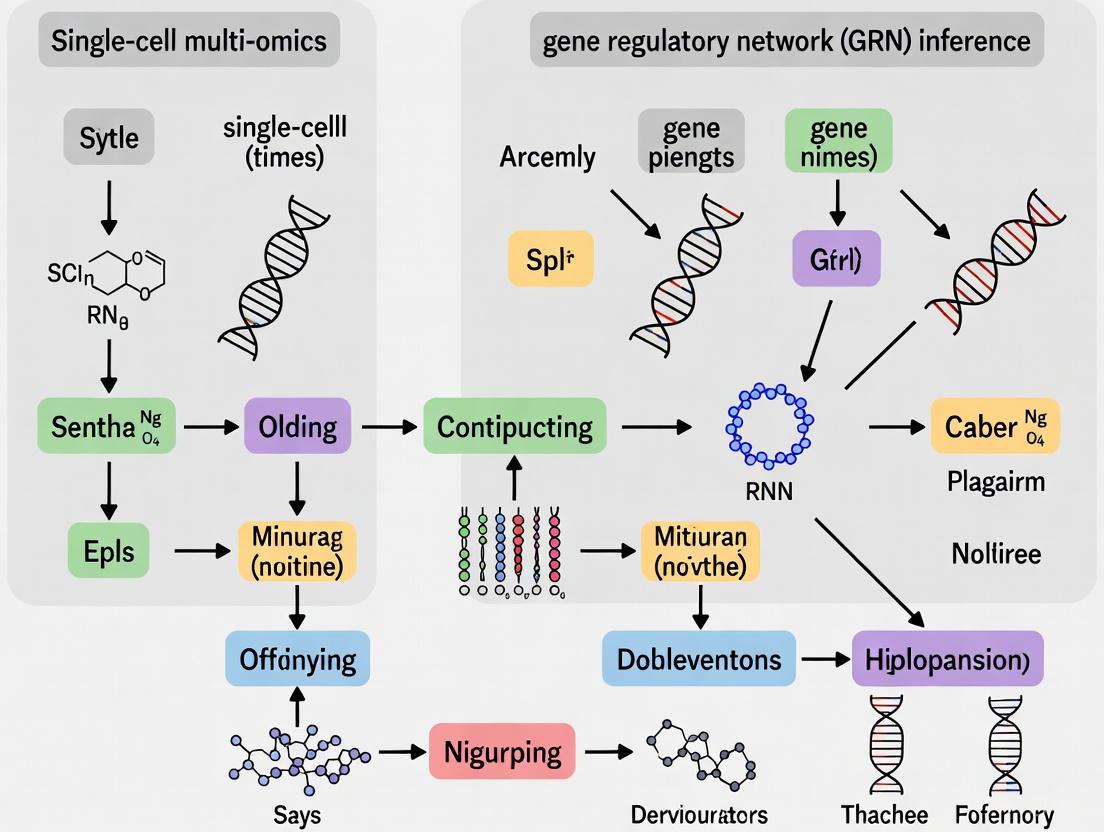

The integration of single-cell multi-omics technologies is revolutionizing our ability to infer gene regulatory networks (GRNs) with unprecedented resolution.

Decoding Developmental Blueprints: A Guide to Single-Cell Multi-Omics GRN Inference for Evolutionary Insights and Disease

Abstract

The integration of single-cell multi-omics technologies is revolutionizing our ability to infer gene regulatory networks (GRNs) with unprecedented resolution. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of GRNs in evolutionary developmental biology. It details state-of-the-art computational methods—from foundational models like scGPT to innovative tools like LINGER and cRegulon—for inferring regulatory interactions from paired transcriptomic and epigenomic data. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for data sparsity and model interpretability, outlines rigorous validation frameworks against resources like ChIP-seq and eQTLs, and synthesizes how these advances are illuminating the regulatory underpinnings of cell fate decisions, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic target discovery.

The Landscape of Gene Regulation: From Cellular Heterogeneity to Foundational Models

A Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) is a collection of molecular regulators that interact with each other and with other substances in the cell to govern the gene expression levels of mRNA and proteins [1]. These networks represent the complex regulatory relationships that control cellular functions, development, and responses to environmental stimuli. GRNs provide a systems-level explanation of biological processes, enabling researchers to understand how genetic information flows through biological systems to determine cell identity, function, and behavior [1] [2]. In the context of single-cell multi-omics research, GRN inference has become crucial for understanding cellular heterogeneity and the mechanisms underlying development and disease [3] [4].

GRNs are mathematically represented as bipartite networks where nodes represent biological entities (genes and their regulators), and edges represent the regulatory interactions between them [1]. Molecular regulators include transcription factors (TFs), RNA-binding proteins, and non-coding RNAs that participate in the control of gene expression. The directionality of these networks is fundamental, as TFs regulate target genes and typically not vice versa [2]. The study of GRNs has been revolutionized by single-cell technologies, which enable the analysis of regulatory relationships at unprecedented resolution across diverse cell types and states [3] [5].

Core Components of GRNs

Nodes: The Biological Entities

Nodes in GRNs represent distinct biological entities involved in gene regulation. The primary node types include:

- Protein-coding genes: Genes that encode transcription factors and other regulatory proteins

- Transcription Factors (TFs): Proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences to activate or repress transcription

- Regulatory Elements (REs): Non-coding DNA sequences such as promoters, enhancers, and silencers that regulate gene expression

- RNA species: Including messenger RNA (mRNA), non-coding RNAs (e.g., microRNAs, lncRNAs) that participate in post-transcriptional regulation [1]

Each node possesses specific properties, including expression levels, activation states, and spatial-temporal localization patterns that influence its regulatory potential.

Edges: The Regulatory Interactions

Edges represent functional relationships between nodes and are characterized by:

- Direction: From regulator to target, indicating the flow of regulatory information

- Type: Activation (positive regulation) or repression (negative regulation)

- Strength: The magnitude of regulatory influence, often quantified using statistical scores

- Evidence: Experimental validation from various data sources [1]

GRN edges can represent different interaction types:

- TF-TG (Transcription Factor-Target Gene): Trans-regulatory relationships

- RE-TG (Regulatory Element-Target Gene): Cis-regulatory relationships

- TF-RE (Transcription Factor-Regulatory Element): Binding relationships [3]

Regulatory Units: Regulons and cRegulons

A regulon is a group of genes regulated as a unit, generally controlled by the same regulatory gene that expresses a protein acting as a repressor or activator [6]. In eukaryotes, this term refers to any group of non-contiguous genes controlled by the same regulatory gene [6]. The concept of core and extended regulons has emerged through comparative genomics, where core regulons contain functions directly related to the primary regulatory signal, while extended regulons reflect specific adaptations to environmental niches [7].

cRegulons (cellular regulons) represent the set of regulatory relationships active in specific cellular contexts, often inferred through computational approaches like SCENIC (Single-Cell Regulatory Network Inference and Clustering) [8]. These context-specific regulatory units enable the identification of transcription factors driving particular cell states in development and disease.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Units in Gene Regulatory Networks

| Regulatory Unit | Definition | Characteristics | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulon | Group of genes regulated by a common transcription factor | Genes may be non-contiguous; coordinated expression response | Enables coordinated cellular responses to stimuli [6] |

| Core Regulon | Subset of regulon conserved across species | Functions directly related to TF-inducing signal | Maintains essential, evolutionarily conserved functions [7] |

| Extended Regulon | Condition-specific portion of regulon | Contains adaptive functions for specific niches | Facilitates rapid adaptation to environmental changes [7] |

| cRegulon | Context-specific regulon activity | Inferred from single-cell data using tools like SCENIC | Identifies drivers of cell identity and state transitions [8] |

| Modulon | Set of regulons collectively regulated | Responds to overall conditions or stresses | Coordinates broader cellular programs beyond single TF control [6] |

Computational Methods for GRN Inference

Traditional and Modern Approaches

GRN inference methods have evolved from correlation-based approaches to sophisticated machine learning models that integrate multiple data types:

Co-expression-based methods such as WGCNA, ARACNe, and GENIE3 infer TF-TG relationships from gene expression data by capturing covariation patterns [1] [3]. While useful, these methods typically produce undirected edges and cannot distinguish causal relationships from correlations [1] [3].

Integrated methods combine multiple data types to improve inference accuracy. For example, PANDA integrates protein-protein interactions, gene expression, and transcription factor binding motifs to reconstruct condition-specific regulatory networks [1]. MONSTER estimates phenotypic-specific regulatory networks using gene expression and TF binding motif data, then computes TF involvement in state transitions [1].

Single-cell multi-omics methods represent the cutting edge in GRN inference. LINGER uses lifelong neural networks to infer GRNs from single-cell multiome data, incorporating atlas-scale external bulk data and TF motif knowledge as manifold regularization [3]. PRISM-GRN employs a Bayesian model that incorporates known GRNs along with scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data in a probabilistic framework [4]. GAEDGRN utilizes gravity-inspired graph autoencoders to capture directed network topology in GRN inference [9].

Table 2: Comparison of GRN Inference Methods and Their Applications

| Method | Approach | Data Requirements | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LINGER [3] | Lifelong neural network | scMultiome data + external bulk atlas | Manifold regularization using TF motifs | 4-7x relative increase in accuracy over existing methods |

| PRISM-GRN [4] | Bayesian model | scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq ± prior GRN | Biologically interpretable architecture; works with unpaired data | Superior precision in sparse regulatory scenarios |

| GAEDGRN [9] | Graph autoencoder | scRNA-seq + prior GRN | Captures directed network topology; gene importance scoring | High accuracy and reduced training time on 7 cell types |

| MONSTER [1] | Regression-based | Gene expression + TF motifs | Identifies TF drivers of cell state transitions at network level | Reveals regulatory changes in phenotype transitions |

| SCENIC [8] | Regulatory inference | scRNA-seq | Identifies regulons and cellular activity states | Enables cell clustering based on regulatory states |

Validation Frameworks

Validating inferred GRNs requires comparison with experimentally determined ground truth data. Common validation approaches include:

- ChIP-seq data: Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing provides direct evidence of TF binding to genomic regions [3]

- eQTL studies: Expression quantitative trait loci link genetic variants to gene expression changes, validating cis-regulatory relationships [3]

- Perturbation studies: CRISPR-based TF knockout followed by expression profiling tests causal relationships [10]

Performance metrics such as Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) ratio provide quantitative assessment of inference accuracy [3].

Experimental Protocols for GRN Analysis

Protocol 1: GRN Inference with LINGER from Single-Cell Multiome Data

Principle: LINGER leverages lifelong learning to incorporate knowledge from external bulk data while refining predictions on single-cell multiome data, using neural networks with manifold regularization [3].

Workflow:

Input Data Preparation

- Obtain single-cell multiome data (paired gene expression and chromatin accessibility)

- Perform quality control: Filter cells based on mitochondrial percentage, unique molecular counts, and doublet detection

- Normalize expression and accessibility counts using standard pipelines

- Annotate cell types using marker genes and reference datasets

External Data Integration

- Download bulk RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data from reference databases (ENCODE)

- Preprocess external data using consistent genomic coordinates and gene annotations

- Align feature spaces between single-cell and bulk datasets

Model Pre-training

- Initialize neural network with three layers: Input (TFs + REs), hidden (regulatory modules), output (target gene expression)

- Pre-train model on external bulk data to learn general regulatory principles

- Apply manifold regularization to enrich TF motifs binding to REs in the same regulatory module

Model Refinement

- Apply Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC) loss to retain knowledge from bulk data while adapting to single-cell data

- Use Fisher information to determine parameter deviation magnitude

- Train until convergence on validation set

GRN Extraction

- Calculate Shapley values to estimate regulatory strength of TF-TG and RE-TG interactions

- Compute TF-RE binding strength through correlation of parameters in the hidden layer

- Construct cell population, cell type-specific, and cell-level GRNs

Protocol 2: cRegulon Analysis with SCENIC

Principle: SCENIC (Single-Cell Regulatory Network Inference and Clustering) identifies regulons and their activity in single-cell RNA-seq data by combining gene co-expression with transcription factor binding motif analysis [8].

Workflow:

Data Preprocessing

- Load single-cell RNA-seq count matrix

- Normalize and scale data using standard methods (e.g., Seurat or Scanpy)

- Identify highly variable genes for downstream analysis

Co-expression Module Identification

- Run GENIE3 or GRNBoost2 to identify potential TF-target associations

- Create gene co-expression modules for each transcription factor

Regulon Formation

- Perform cis-regulatory motif analysis using RcisTarget

- Retain direct targets with enriched motif occurrence in regulatory regions

- Define regulons as TF plus its confident direct targets

Cellular Regulon Activity Scoring

- Calculate regulon activity per cell using AUCell

- Binarize activity to identify cells with active regulons

- Cluster cells based on regulon activity rather than gene expression

Differential Regulon Analysis

- Identify regulons with differential activity between conditions

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on target genes of differential regulons

- Visualize results using t-SNE or UMAP projections colored by regulon activity

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GRN Analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | 10x Genomics Single-Cell Multiome | Simultaneous measurement of gene expression and chromatin accessibility | LINGER input data generation [3] |

| Bulk Reference Data | ENCODE RNA-seq/ATAC-seq | Provides external regulatory context across diverse cellular contexts | Training data for LINGER pre-training [3] |

| Motif Databases | JASPAR, CIS-BP | Transcription factor binding specificity profiles | Regulon definition in SCENIC and PRISM-GRN [3] [8] |

| Validation Resources | ChIP-seq datasets | Ground truth for TF-binding events | Validation of trans-regulatory predictions [3] |

| Validation Resources | eQTL datasets (GTEx, eQTLGen) | Links genomic variants to expression changes | Cis-regulatory relationship validation [3] |

| Software Tools | LINGER, PRISM-GRN, SCENIC | GRN inference from single-cell data | Cell type-specific regulatory network reconstruction [3] [4] [8] |

| Perturbation Tools | CRISPR-based editors | Functional validation of regulatory relationships | Causal testing of TF-target relationships [10] |

Analysis and Interpretation of GRN Data

Network Topology and Architecture

GRN analysis extends beyond edge identification to network topology characterization. Key topological features include:

- Node degree: The number of relationships in which a node engages, with in-degree (number of TFs regulating a gene) and out-degree (number of genes regulated by a TF) providing distinct biological insights [2]

- Hub identification: TF hubs regulate many target genes, while gene hubs are regulated by many TFs, indicating central positions in regulatory hierarchies [2]

- Betweenness centrality: Identifies nodes that connect different network modules and may control information flow [2]

- Flux capacity: The product of in-degree and out-degree for regulator nodes, indicating their potential influence on information propagation [2]

Network motifs—recurring regulatory patterns—provide insights into functional circuit design. Common motifs include feed-forward loops, feedback loops, and single-input modules that generate specific dynamic behaviors.

Evolutionary and Developmental Perspectives

GRNs evolve through changes in network architecture, with important implications for evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo) [10]. Core regulons—containing functions directly related to the TF-inducing signal—tend to be conserved across species, while extended regulons evolve rapidly to reflect species-specific adaptations [7]. Heterochrony (changes in timing) and homeosis (changes in identity) at the single-cell level can drive the emergence of novel cell types through alterations in GRN architecture [10].

In mammalian hematopoietic stem cells, sequence heterochrony—changing the order in which transcription factors C/EBPα and GATA become active—switches daughter cell identity from eosinophils to basophils [10]. This demonstrates how temporal rewiring of GRNs can generate cellular diversity without changes in gene content.

Disease Applications

GRN analysis provides insights into disease mechanisms by identifying dysregulated regulatory programs. In glioblastoma, SCENIC analysis identified IRF and STAT family transcription factors as specific regulators of a unique tumor cell subset that creates an immunomodulatory microenvironment [8]. In chlorine-induced acute lung injury, regulatory network analysis revealed Ets1, Elf1, and Elk3 as key upregulated transcription factors in T cells following exposure [8].

Hypertension research using GRN approaches has demonstrated that genes with differential expression have interactive effects, highlighting the importance of network-level understanding beyond single gene analyses [8]. These applications underscore the translational potential of GRN research in identifying therapeutic targets and biomarkers.

The emergence of single-cell multi-omics technologies represents a paradigm shift in our ability to decipher the complex regulatory logic governing evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo). These technologies enable the simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular layers—transcriptomics, epigenomics, and spatial context—within individual cells, providing unprecedented resolution for deconstructing cellular heterogeneity and lineage relationships [11]. For the first time, researchers can systematically infer Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) that underlie cell fate decisions, tissue patterning, and phylogenetic constraints across species.

In evo-devo research, GRNs serve as the fundamental computational framework encoding the developmental program of an organism. Traditional bulk sequencing methods obscured cell-to-cell variation, masking rare transitional states and regulatory dynamics critical for understanding evolutionary processes. The integration of single-cell transcriptomics with epigenomic profiling and spatial information now permits the reconstruction of combinatorial regulatory modules that drive cellular differentiation and evolutionary adaptation [12] [11]. This technological revolution is powered by concurrent advances in both experimental methods and computational frameworks, particularly foundation models pretrained on millions of cells that enable zero-shot transfer learning across biological contexts and species [11].

Technological Foundations and Current Methodologies

Multi-Omic Profiling Platforms

Single-cell multi-omics technologies have evolved from single-modality measurements to integrated platforms that capture complementary molecular features from the same cell. The current landscape encompasses diverse methodological approaches targeting different combinations of omics layers.

Table 1: Single-Cell Multi-Omics Technologies and Applications

| Technology Type | Measured Modalities | Key Applications in Evo-Devo | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| scEpi2-seq | DNA methylation + Histone modifications (H3K9me3, H3K27me3, H3K36me3) | Epigenetic memory during cell type specification; Dynamics of heterochromatin formation | [13] |

| scGPT (Foundation Model) | Cross-modal integration (transcriptomics + epigenomics) | Zero-shot cell annotation; In silico perturbation modeling; Cross-species comparison | [11] |

| cRegulon Framework | TF combinatorics + chromatin accessibility + gene expression | Identification of conserved regulatory modules across species; Cell type attractor states | [12] |

| Spatial Molecular Imaging (CosMx SMI) | Whole transcriptome + protein markers + spatial context | Tissue organization principles; Stem cell niche characterization; Morphogenetic gradients | [14] |

The scEpi2-seq method exemplifies cutting-edge innovation in epigenetic profiling, achieving simultaneous detection of histone modifications and DNA methylation at single-cell resolution. This technique leverages TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) instead of bisulfite conversion, preserving adapter sequences for more efficient library preparation. Application of scEpi2-seq to mouse intestinal development revealed how H3K27me3 and DNA methylation interact during cell type specification, demonstrating that differentially methylated regions can exhibit independent regulation alongside histone modification control [13].

Computational Frameworks for GRN Inference

The complexity of single-cell multi-omics data has driven the development of sophisticated machine learning approaches for GRN inference. These methods have evolved from classical statistical models to deep learning architectures capable of capturing nonlinear regulatory relationships.

Table 2: Machine Learning Methods for GRN Inference from Single-Cell Data

| Algorithm | Learning Type | Key Technology | Compatible Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| cRegulon | Unsupervised | Matrix factorization + mixture modeling | scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq |

| GRNFormer | Supervised | Graph Transformer | Single-cell transcriptomics |

| DeepMAPS | Unsupervised | Heterogeneous graph transformer | scATAC-seq + Multi-omic |

| GCLink | Contrastive learning | Graph contrastive link prediction | Single-cell multi-omics |

| scGPT | Foundation model | Transformer + masked gene modeling | Cross-modal integration |

The cRegulon algorithm represents a significant conceptual advance by modeling combinatorial regulation of transcription factors based on diverse GRNs derived from single-cell multi-omics data [12]. Unlike earlier methods that considered single TFs (Regulons) or TF-enhancer units (eRegulons), cRegulon identifies modules of cooperating TFs that collectively regulate common target genes. This approach more accurately reflects the biological reality of developmental regulation, where master transcription factors often act in complexes to determine cell fate. Through benchmarking and applications to real datasets, cRegulon has demonstrated superior performance in identifying TF combinatorial modules as fundamental regulatory units underlying Waddington's epigenetic landscape [12].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: scEpi2-seq for Simultaneous Histone Modification and DNA Methylation Profiling

Principle: scEpi2-seq enables joint profiling of histone modifications and DNA methylation in single cells by combining antibody-directed chromatin tagging with TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing [13].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Protein A-micrococcal nuclease (pA-MNase) fusion protein

- validated antibodies for specific histone modifications (e.g., H3K9me3, H3K27me3, H3K36me3)

- TAPS conversion reagents

- Single-cell barcoded adapters with UMI, T7 promoter, and Illumina handles

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) system

- 384-well plates

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Cell Preparation and Permeabilization: Isolate single cells and permeabilize to enable antibody access while maintaining viability.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate with histone modification-specific antibodies in appropriate buffer conditions.

- pA-MNase Tethering: Add pA-MNase fusion protein to bind antibody-targeted nucleosomes.

- Single-Cell Sorting: Sort individual cells into 384-well plates containing reaction buffer using FACS.

- MNase Digestion: Initiate targeted chromatin cleavage by adding Ca2+ to activate MNase.

- Fragment Processing: Repair DNA ends and add poly-A tails to MNase-generated fragments.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate barcoded adapters containing cell-specific barcodes, UMIs, and promoter sequences.

- TAPS Conversion: Pool material and perform TET-assisted pyridine borane conversion to detect methylated cytosines.

- Library Preparation: Conduct in vitro transcription, reverse transcription, and PCR amplification.

- Sequencing: Perform paired-end sequencing on Illumina platforms.

Quality Control Metrics:

- Minimum of 50,000 CpGs detected per cell

- Fraction of reads in peaks (FRiP) >0.7

- C-to-T conversion efficiency >95%

- Correlation with ENCODE reference data >0.8

Protocol: cRegulon Analysis for Combinatorial TF Module Identification

Principle: cRegulon infers regulatory modules by modeling combinatorial regulation of transcription factors across multiple cell types/states using single-cell multi-omics data [12].

Input Data Requirements:

- Paired or unpaired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data

- Cell type annotations or clustering results

- Transcription factor binding motif database

Computational Steps:

- Data Preprocessing: Quality control, normalization, and batch correction for both modalities.

- GRN Construction: Infer cluster-specific gene regulatory networks using established methods.

- Combinatorial Effect Calculation: For each cluster-specific GRN, compute pairwise TF combinatorial effects considering co-regulation and activity specificity.

- Matrix Factorization: Model the combinatorial effect matrix as a mixture of rank-1 matrices corresponding to regulatory modules.

- Module Extraction: Identify TF modules, associated regulatory elements, and target genes through optimization.

- Cell Type Annotation: Annotate cell types based on cRegulon activities and validate with known markers.

Implementation Considerations:

- The method accommodates both paired and unpaired multi-omics data

- Key parameters include the number of modules and sparsity constraints

- Output includes TF modules, REs, TGs, and their associations across cell types

Successful implementation of single-cell multi-omics approaches requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources optimized for evo-devo GRN inference.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Multi-Omics

| Resource Category | Specific Product/Platform | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Profiling | CosMx Spatial Molecular Imager (Bruker) | High-plex single-cell imaging of RNA and protein in tissue context |

| Epigenetic Profiling | scEpi2-seq Reagent System | Simultaneous detection of histone modifications and DNA methylation |

| Single-Cell Partitioning | 10x Genomics Chromium System | High-throughput single-cell partitioning and barcoding |

| Multi-omic Assay | NEBNext Single-Cell Multi-Omics Kit | Simultaneous profiling of transcriptome and epigenome from same cell |

| Foundation Models | scGPT, scPlantFormer, Nicheformer | Pretrained models for cross-species annotation and perturbation modeling |

| GRN Inference | cRegulon Software Package | Identification of TF combinatorial modules from multi-omics data |

| Data Integration | BioLLM Framework | Standardized benchmarking and integration of single-cell foundation models |

Bruker's CosMx Spatial Molecular Imager enables whole transcriptome imaging at single-cell resolution within intact tissue sections, providing critical spatial context for GRN inference in developing organisms [14]. For computational analysis, foundation models like scGPT—pretrained on over 33 million cells—demonstrate exceptional performance in zero-shot cell type annotation and in silico perturbation modeling, significantly accelerating comparative analyses across species [11].

Integrated Analysis and Visualization Framework

The interpretation of single-cell multi-omics data requires specialized visualization strategies that represent the interconnected nature of transcriptional and epigenetic regulation across spatial contexts.

This integrated framework highlights how different data modalities converge to reconstruct evolutionarily informed GRNs. The modularity of GRNs enables reduction of complexity while preserving biological meaning, with regulatory modules serving as fundamental units that can be compared across species to infer evolutionary trajectories [12] [11]. Tools like cRegulon specifically exploit this modularity to identify conserved and divergent regulatory programs underlying homologous developmental processes.

The single-cell multi-omics revolution has fundamentally transformed our approach to GRN inference in evolutionary developmental biology. By simultaneously profiling transcriptomic, epigenomic, and spatial information from individual cells, researchers can now reconstruct regulatory networks with unprecedented resolution and context specificity. The development of specialized technologies like scEpi2-seq for epigenetic profiling and computational frameworks like cRegulon for identifying combinatorial TF modules represents significant milestones in this rapidly advancing field.

Looking forward, several emerging trends promise to further accelerate discovery. Foundation models pretrained on massive single-cell datasets will enable increasingly accurate cross-species predictions and in silico perturbation studies [11]. The integration of spatial context with multi-omic measurements will illuminate how tissue microenvironment influences regulatory dynamics [14] [15]. Finally, the development of standardized benchmarking platforms like BioLLM will promote reproducibility and collaborative model development across the scientific community [11]. As these technologies mature, they will continue to provide deeper insights into the evolutionary principles that shape developmental gene regulatory networks across the tree of life.

The integration of single-cell multi-omics into evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo) has revolutionized our capacity to decipher the gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that orchestrate cell fate, shape developmental trajectories, and underlie disease mechanisms. GRNs are mathematical representations of the complex interactions between transcription factors (TFs), cis-regulatory elements (CREs), and their target genes that collectively control cellular identity and function [16] [17]. The emerging field of ecological evolutionary developmental biology (Eco-Evo-Devo) emphasizes that these developmental processes are not isolated but are shaped by environmental cues and evolutionary pressures [18]. Rather than being a loose aggregation of research topics, Eco-Evo-Devo provides a coherent conceptual framework for exploring the causal relationships among developmental, ecological, and evolutionary levels, positioning GRN analysis as a central tool for understanding phenotypic diversification [18].

The advent of single-cell technologies has been pivotal, enabling researchers to move beyond bulk tissue analysis and capture the cellular heterogeneity that underpins developmental and evolutionary processes. While bulk sequencing averages signals across thousands of cells, single-cell sequencing (SCS) reveals cell-to-cell variability, identifies rare populations, and allows for the reconstruction of evolutionary relationships [19]. This is particularly powerful in Evo-Devo research, where understanding the emergence of novel cell types and the divergence of developmental pathways across species is paramount. Modern single-cell multi-omics platforms can now simultaneously profile multiple molecular layers—such as the transcriptome and epigenome—from the same cell, providing an unprecedented, matched view of the regulatory state [3] [16]. This technological leap addresses the central biological question of how genomic sequence and environmental interaction give rise to organismal form and function through the mechanism of GRN activity.

Application Note: Inferring GRNs from Single-Cell Multiome Data

Inferring GRNs from single-cell multiome data (e.g., simultaneously measured scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq) requires computational methods that can integrate these disparate data types to predict regulatory interactions. The underlying methodological foundations are diverse, each with distinct strengths and limitations for specific biological questions [16].

Table: Methodological Foundations for GRN Inference

| Approach | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based | Measures co-expression or association (e.g., Pearson's correlation, mutual information) between TFs and potential target genes [16]. | Simple, intuitive, and computationally efficient. | Cannot distinguish direct from indirect regulation; infers undirected networks [16]. |

| Regression models | Models a target gene's expression as a function of multiple predictor TFs and CREs, using techniques like linear or penalized regression (LASSO) [16]. | Provides interpretable coefficients indicating regulatory strength and direction. | Can be unstable with highly correlated predictors; may overfit without regularization [16]. |

| Probabilistic models | Uses graphical models to represent the probabilistic dependence between variables like TFs and their targets [16]. | Allows for filtering and prioritization of interactions based on probability. | Often relies on distributional assumptions that may not fit all gene expression data [16]. |

| Deep learning models | Employs neural networks (e.g., multi-layer perceptrons, autoencoders) to learn complex, non-linear regulatory relationships from the data [16]. | Highly versatile and can model complex, non-linear mechanisms. | Requires large amounts of data; less interpretable ("black box"); computationally intensive [16]. |

Protocol: GRN Inference with LINGER and scTFBridge

This protocol details the use of two state-of-the-art deep learning methods, LINGER and scTFBridge, which are designed to leverage single-cell multiome data and external knowledge for robust GRN inference.

I. Experimental Design and Data Preparation

- Single-Cell Multiome Sequencing: Perform single-cell multiome sequencing (e.g., using the 10x Genomics Multiome platform) on your sample of interest to obtain paired gene expression and chromatin accessibility data from the same cells [3] [19].

- Data Preprocessing:

- Gene Expression Matrix: Process raw sequencing data through a standard scRNA-seq pipeline (e.g., Cell Ranger). Output a cell-by-gene count matrix. Perform quality control to remove low-quality cells and doublets, followed by normalization and log-transformation [3] [17].

- Chromatin Accessibility Matrix: Process scATAC-seq data to identify accessible peaks. Output a cell-by-peak count matrix. Quality control is essential to remove low-quality cells [3] [17].

- Cell Type Annotation: Annotate cell types by integrating the data with existing references or by performing unsupervised clustering and marker gene identification [3].

- External Data and Prior Knowledge Curation:

- For LINGER, download a large-scale external bulk dataset, such as the ENCODE project data, which contains hundreds of samples across diverse cellular contexts [3].

- For scTFBridge, and to enhance LINGER, compile a database of TF-motif binding information from resources like JASPAR or Cistrome [20] [21].

II. Computational GRN Inference Procedure

Workflow Title: GRN Inference with Lifelong Learning & Disentanglement

LINGER Workflow (Lifelong neural network for gene regulation) [3]:

- Pre-training on External Bulk Data: Initialize a neural network model (

BulkNN) designed to predict target gene (TG) expression using TF expression and regulatory element (RE) accessibility as input. Pre-train this model on the large-scale external bulk data (e.g., from ENCODE) to learn a general regulatory profile. - Lifelong Learning Refinement: Refine the pre-trained model on the single-cell multiome data using elastic weight consolidation (EWC). This regularization technique uses the Fisher information to control how much model parameters can deviate from the bulk-data prior, preventing catastrophic forgetting and ensuring stable adaptation to the new data.

- Regulatory Strength Calculation: After training, compute the regulatory strength of TF-TG and RE-TG interactions using Shapley values from cooperative game theory. Shapley values provide a unified measure of each feature's (TF or RE) contribution to the prediction of each target gene's expression, offering an interpretable measure of regulatory influence.

- TF-RE Binding Inference: Generate TF-RE binding strength by calculating the correlation between TF and RE parameters learned in the model's second layer, which is guided by the incorporated motif information.

scTFBridge Workflow [20]:

- Model Training: Train a disentangled deep generative model (

scTFBridge) on the single-cell multiome data. The model is designed to separate (disentangle) the latent data representation into components that are shared across the transcriptomic and epigenomic layers and components that are specific to each layer. - Integration of Motif Binding: Inform the model's shared latent space with known TF-motif binding information. This step aligns the shared embeddings with specific TF regulatory activities, enhancing the biological interpretability of the model.

- Explainable GRN Inference: Use explainability methods to compute regulatory scores for REs and TFs. These scores enable robust inference of the GRN, identifying key regulators and their target genes.

III. Downstream Analysis and Validation

- GRN Analysis: Analyze the inferred cell-type-specific GRNs to identify key driver TFs, autoregulatory loops, and core regulatory modules.

- Trajectory Inference: Project the GRN dynamics onto developmental trajectories to understand how regulatory programs shift during cell state transitions [17].

- Functional Enrichment: Perform gene ontology (GO) or pathway enrichment analysis on modules of co-regulated genes to understand the biological processes controlled by specific TFs.

- Experimental Validation: Prioritize key inferred regulatory interactions for experimental validation using techniques such as CRISPR perturbation [3] or ChIP-seq [16] to confirm the causal role of identified TFs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Single-Cell Multi-omics GRN Studies

| Reagent / Platform | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression | Simultaneous profiling of chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) and gene expression (RNA-seq) in the same single cell [3] [19]. | Provides a paired view of the epigenomic and transcriptomic state; high-throughput; commercial standard. |

| Fluidigm C1 System | Plate-based microfluidics platform for single-cell isolation and library preparation [19]. | Suitable for processing hundreds of cells with high sensitivity; ideal for full-length transcriptome protocols like Smart-seq3. |

| Mission Bio Tapestri | Targeted scDNA-seq platform for high-throughput genotyping of thousands of cells [19]. | Enables linking of clonal genetic architecture to transcriptional phenotypes; focuses on pre-defined genomic regions. |

| Bioskryb ResolveDNA | Whole-genome amplification platform for single-cell whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing [19]. | Provides broader genomic coverage for analyzing single-nucleotide variants and copy number alterations at lower throughput. |

| JASPAR / Cistrome Databases | Curated databases of transcription factor binding motifs and chromatin profiles [20] [21]. | Provides essential prior knowledge for linking accessible chromatin regions to potential TF binding. |

| ChIP-seq / CUT&Tag | Genome-wide profiling of protein-DNA interactions for specific transcription factors [17]. | Gold-standard experimental method for validating TF binding sites inferred from GRN models. |

Application in Evolutionary and Developmental Biology

Case Study: Deciphering the Neural Crest GRN

The neural crest is a vertebrate-specific cell population that gives rise to diverse structures, including parts of the craniofacial skeleton, peripheral nervous system, and pigment cells. Its evolution is considered a key event in vertebrate diversification. A core objective in Evo-Devo is to reconstruct the GRN underlying neural crest development and to understand how it evolved.

Experimental Diagram Title: Reconstructing the Neural Crest GRN Across Species

- Sample Collection: Collect embryos from a model vertebrate (e.g., chick or mouse) at key developmental time points encompassing neural crest specification, migration, and differentiation. For evolutionary contrast, include embryos from a non-vertebrate deuterostome relative, such as the ascidian Ciona intestinalis, where a cell population with properties similar to neural crest has been identified [22].

- Single-Cell Multiome Sequencing: Dissect tissue containing neural crest precursors and their derivatives. Use the 10x Genomics Multiome platform to generate paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq libraries for thousands of cells from each species.

- Cross-Species GRN Inference: Process the data for each species separately through the LINGER or scTFBridge pipeline. The prior knowledge of TF motifs should be derived from databases like JASPAR to facilitate cross-species comparison.

- Comparative GRN Analysis: Compare the inferred GRNs to identify:

- The Conserved Kernel: A set of TFs (e.g., SoxE, FoxD, Tfap2) and their regulatory interactions that are present in both the vertebrate and non-vertebrate GRNs, representing an ancient, core regulatory module [22] [18].

- Vertebrate-Specific Innovations: New TFs incorporated into the network, novel regulatory interactions, or the co-option of existing modules, which likely contributed to the evolutionary elaboration of the neural crest.

This integrated approach moves beyond simple gene expression comparisons to reveal the precise architectural changes in the underlying GRN that facilitated the evolution of this key developmental cell type.

Application Note: Eco-Evo-Devo of Skeletal Morphology

A central tenet of Eco-Evo-Devo is that environmental factors can influence development to generate phenotypic variation that is subject to evolutionary selection. This protocol outlines how to use single-cell multi-omics to study the interaction between environment and GRNs in shaping skeletal morphology, a classic Evo-Devo model [18] [24].

Protocol:

- Environmental Perturbation: Subject model organisms (e.g., stickleback fish or mice from different ecological niches) to controlled environmental variables, such as diet, temperature, or mechanical stress, known to affect skeletal development [18].

- Time-Course Sampling: Collect developing skeletal tissue (e.g., limb bud) from experimental and control groups across multiple developmental stages.

- Multiomic Profiling: Perform single-cell multiome sequencing on all samples. Use sample multiplexing techniques (e.g., cell hashing) to pool samples for sequencing, reducing batch effects [19].

- GRN Inference and Integration: Infer GRNs for each condition and time point. Use a tool like scMKL [21] to classify cells based on environmental treatment and identify the key transcriptomic and epigenomic features (pathways, TF activities) that are responsive to the environmental cue.

- Linking Mechanism to Phenotype: Correlate changes in GRN architecture (e.g., rewiring of a specific TF module) with quantitative morphological measurements of the resulting skeletal phenotype. This directly links an environmental input, through a developmental GRN, to an evolved adaptive output.

The emergence of foundation models represents a paradigm shift in single-cell multi-omics analysis, enabling the learning of universal cellular representations that transform our ability to decipher gene regulatory networks (GRNs). These models, pre-trained on massive datasets comprising millions of cells, capture fundamental biological principles that transfer across diverse downstream tasks. This application note examines two pioneering frameworks—scGPT and scPlantFormer—detailing their architectural innovations, training methodologies, and experimental protocols for GRN inference in evolutionary developmental biology research. We provide comprehensive benchmarking data, implementation workflows, and reagent solutions to equip researchers with practical tools for leveraging these transformative technologies in drug development and basic research.

Foundation models are large-scale neural networks pre-trained on extensive datasets that learn generalizable representations transferable to various downstream tasks [11]. In single-cell biology, these models have emerged as powerful tools for deciphering cellular heterogeneity, gene regulation, and developmental processes. The conceptual parallel between natural language and cellular biology—where genes correspond to words and cells to documents—has enabled the successful adaptation of transformer architectures to biological data [25] [26].

Universal representation learning in single-cell biology involves capturing fundamental principles of gene expression, regulation, and cellular identity that remain consistent across tissues, species, and experimental conditions. scGPT and scPlantFormer exemplify this approach, demonstrating exceptional capability in cross-species annotation, perturbation modeling, and gene regulatory network inference [11] [26]. Their performance stems from pre-training on datasets of unprecedented scale—33 million cells for scGPT and 1 million plant cell profiles for scPlantFormer—allowing them to distill critical biological insights concerning genes and cells [25] [26].

For evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), these models offer particular promise in uncovering conserved regulatory principles across species and tracing the evolutionary trajectories of cell types. By learning universal representations, foundation models can bridge the gap between model organisms and humans, accelerating the translation of basic research findings into therapeutic insights.

Model Architectures and Technical Specifications

Core Architectural Components

Both scGPT and scPlantFormer build upon the transformer architecture but incorporate distinct modifications tailored to biological data.

scGPT employs a standard transformer decoder architecture similar to GPT models in natural language processing. The model uses gene expressions as input tokens, embedding them into a continuous representation space before processing through multiple transformer blocks with masked self-attention [25] [27]. This design enables scGPT to learn contextual relationships between genes and predict expression values in a self-supervised manner through masked gene modeling.

scPlantFormer implements a transformer encoder architecture with CellMAE (Cell Masked Autoencoding) pretraining, specifically optimized for plant single-cell omics [26]. The model incorporates phylogenetic constraints into its attention mechanism, allowing it to capture evolutionary relationships between species [11]. This design excels at cross-species data integration and resolving batch effects common in plant single-cell datasets.

Key Technical Innovations

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Foundation Models

| Feature | scGPT | scPlantFormer |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture Type | Transformer Decoder | Transformer Encoder with CellMAE |

| Pre-training Data | 33+ million cells [25] | 1 million Arabidopsis thaliana cells [26] |

| Pre-training Objectives | Masked gene modeling, contrastive learning [11] | Mean square error loss, plant-specific optimization [26] |

| Key Innovation | Generative pre-training across diverse cell types | Phylogenetic constraints in attention mechanism |

| Handling Multi-omics | Native support for multi-omic integration [25] | Specialized for plant transcriptomics with cross-species capabilities |

Figure 1: Foundation Model Training Workflow. Both scGPT and scPlantFormer follow this general pipeline, transforming single-cell data into universal representations through self-supervised pre-training.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Protocol 1: Single-Cell Data Preprocessing for Foundation Models

Quality Control Metrics

- Calculate mitochondrial percentage, excluding cells with >20% mitochondrial reads

- Filter cells with unusually high or low total counts (outside 3 median absolute deviations)

- Remove cells with detected genes <200 or >6000 to eliminate doublets and low-quality cells

- Apply Scrublet to identify and remove potential doublets [28]

Normalization Procedure

Batch Effect Considerations

- Identify batch covariates (donor, technology, laboratory)

- For integration tasks, use Harmony or Combat for preliminary batch correction

- Note: Foundation models can address batch effects during fine-tuning [29]

Model Training and Fine-tuning

Protocol 2: Transfer Learning for Downstream Tasks

Task Formulation

- Cell type annotation: Frame as classification problem using reference atlases

- GRN inference: Formulate as edge prediction between TFs and target genes

- Perturbation response: Model as regression from treatment to expression changes

Fine-tuning Procedure for scGPT

Fine-tuning Procedure for scPlantFormer

- Utilize species-specific tokenization for cross-species applications

- Leverage phylogenetic tree information during attention calculation

- Apply label transfer from reference species to query species

- Use data augmentation with random masking for improved generalization [26]

GRN Inference Methodology

Protocol 3: Gene Regulatory Network Inference

Data Requirements

- Single-cell multiome data (paired RNA-seq + ATAC-seq) preferred

- Minimum of 5,000 cells for robust inference

- Cell type annotations at appropriate resolution

- External bulk data for validation (ENCODE, GTEx) [3]

Implementation with LINGER Framework

- Pre-train on external bulk data from ENCODE (400+ samples)

- Refine on single-cell data using elastic weight consolidation

- Extract regulatory strengths using Shapley values

- Construct cell type-specific GRNs from general GRN [3]

Validation Procedures

Performance Benchmarks and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Benchmarking Results Across Downstream Tasks

| Task | Model | Performance Metrics | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Type Annotation | scGPT | 92% accuracy on PBMC datasets [25] | Zero-shot capability to novel cell types |

| scPlantFormer | 92% cross-species accuracy [11] | Effective across plant species | |

| GRN Inference | LINGER | 4-7x relative increase in accuracy vs. baselines [3] | Incorporates atlas-scale external data |

| scGPT | Superior AUPRC in perturbation prediction [25] | Generative modeling of network dynamics | |

| Multi-omic Integration | GLUE | Lowest FOSCTTM error in benchmark [29] | Graph-linked embedding for distinct feature spaces |

| scGPT | Effective integration of transcriptomics and epigenomics [25] | Unified representation space | |

| Cross-species Analysis | scPlantFormer | Accurate annotation between Arabidopsis and rice [26] | Phylogenetic attention mechanism |

Application to Evolutionary Developmental Biology

Foundation models demonstrate particular utility in evo-devo research through their ability to:

Identify Conserved Regulatory Programs

- Detect homologous cell types across divergent species

- Trace evolutionary trajectories of regulatory elements

- Identify lineage-specific regulatory innovations [26]

Model Developmental Processes

Accelerate Translational Applications

- Bridge model organisms to human biology for drug target identification

- Predict conserved toxicity pathways across species

- Identify cell type-specific expression of drug targets [11]

Figure 2: GRN Inference Workflow for Evo-Devo Research. Foundation models integrate multi-omic data with external resources to infer regulatory networks applicable to evolutionary studies.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT Model Zoo | Pre-trained Models | Task-specific fine-tuning starting points | GitHub: bowang-lab/scGPT [27] |

| scPlantFormer | Plant Foundation Model | Cross-species analysis in plants | GitHub Repository [26] |

| LINGER | GRN Inference | Lifelong learning for regulatory networks | Nature Biotechnology [3] |

| GLUE | Multi-omic Integration | Graph-linked unified embedding | Nature Biotechnology [29] |

| CellXGene | Data Repository | 33+ million cells for reference mapping | CZ CELLxGENE Discover [11] |

| BioLLM | Benchmarking Framework | Standardized evaluation of foundation models | [11] |

The integration of foundation models into single-cell multi-omics analysis represents a transformative advancement with profound implications for evolutionary developmental biology and drug development. scGPT and scPlantFormer exemplify how universal representation learning can uncover fundamental principles of gene regulation that transcend species boundaries.

Future developments will likely focus on multimodal integration—combining transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and spatial data within unified foundation models [11]. Additionally, interpretability enhancements will be crucial for translating model predictions into mechanistic biological insights, particularly for identifying key regulatory drivers of development and disease [11] [31].

For drug development professionals, these models offer accelerating pathways from target identification to validation by predicting cell type-specific responses to perturbations and identifying conserved regulatory mechanisms across species. The ability to conduct in silico experiments on universal representations provides an efficient alternative to costly screening approaches while offering insights into fundamental biological processes.

As foundation models continue to evolve, they will increasingly serve as the computational scaffold for understanding the regulatory logic of development, evolution, and disease—ultimately bridging the gap between cellular omics and actionable biological understanding.

The Waddington epigenetic landscape serves as a powerful metaphor for understanding cellular differentiation and fate decisions during development. Originally proposed by Conrad H. Waddington, this conceptual framework depicts a developing cell as a ball rolling down a sloping hillside characterized by valleys and ridges [32]. The path taken by the ball represents a specific developmental trajectory, with branching points corresponding to fate decisions, and the end points of the valleys (the basins) representing the terminally differentiated cell types [33] [32]. In modern systems biology, this metaphorical landscape has been formalized mathematically, where the various cell states are conceptualized as attractors within a high-dimensional state space defined by the activity levels of genes in a gene regulatory network (GRN) [32] [34]. The stability of a cell type is then understood in terms of the depth and size of these attractor basins, with the barriers between basins correlating with the difficulty of transitioning from one cell state to another [32].

This framework has gained renewed importance with the advent of single-cell multi-omics technologies, which enable the simultaneous measurement of gene expression and chromatin accessibility in individual cells [3] [35]. These rich datasets provide an unprecedented opportunity to infer the architecture of GRNs and computationally reconstruct the Waddington landscape for specific biological systems, from embryonic development to disease processes like cancer [33]. The ability to quantify this landscape offers profound insights into the mechanisms underlying cellular heterogeneity, phenotypic plasticity, and the reprogramming of cell identity [32]. This Application Note provides detailed protocols for applying this framework through GRN inference from single-cell multiome data, with specific examples from developmental biology and cancer research.

Theoretical Foundations: From Metaphor to Quantitative Model

The Modern Interpretation of Attractor States

In contemporary quantitative biology, Waddington's metaphorical landscape is formalized through dynamical systems theory. The state of a cell is represented by a vector ( S(t) = (x1, x2, ..., xN) ), where each ( xi ) represents the expression value or cellular concentration of the product of gene ( i ) in an N-gene regulatory network [32]. The probability landscape ( P ) is defined over this N-dimensional state space, where states with locally highest probability (lowest potential, where ( U = -\ln P )) represent the attractor states of the underlying GRN [32]. These attractors correspond to distinct cell phenotypes—including stable differentiated states, progenitor states, and pathological states like cancer subtypes [33] [32].

The stability of these cellular states is quantitatively related to the barrier heights between attractor basins in the landscape. Higher barriers correspond to longer escape times, making transitions between cell types less likely and thus representing more stable cellular states [32]. This quantitative relationship provides crucial insights for understanding differentiation processes and designing cellular reprogramming strategies. The developmental progression from a pluripotent stem cell to differentiated lineages can be visualized as a ball moving from the broad, elevated basin of the undifferentiated state down to deeper, more confined basins representing terminally differentiated cells [32].

Mathematical Formalisms for Landscape Construction

Several mathematical approaches exist for quantifying the Waddington landscape, with Hopfield networks providing one particularly powerful framework [34]. These auto-associative artificial neural networks store patterns as attractors of the network and can recall these patterns from noisy or incomplete inputs, effectively modeling the recall of stable gene expression patterns during differentiation [34]. For a network of N genes, the state of the system is defined by the expression levels of these genes, and the attractors represent the stable expression configurations corresponding to different cell types.

An alternative approach utilizes ordinary differential equations (ODEs) based on known regulatory interactions [33]. For a GRN model, the system can be described by equations of the form ( dx/dt = F(x) ), where ( x ) is a vector of gene expression levels and ( F ) represents the regulatory logic [33] [32]. The epigenetic landscape can then be constructed by performing numerous stochastic simulations from different initial conditions and calculating the probability distribution of the states [33]. For instance, in a study of breast cancer subtypes, 10,000 stochastic simulations were used to map the attractor landscape containing HER2+ and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) basins [33].

Figure 1: The Waddington Landscape Metaphor for Cell Fate Decisions. This diagram visualizes the progressive restriction of cell fate during development, from pluripotent stem cells to various differentiated states through branching valleys on an epigenetic landscape.

Protocol 1: Inferring GRNs from Single-Cell Multiome Data Using LINGER

Background and Principles

The LINGER (Lifelong neural network for gene regulation) framework represents a significant advance in GRN inference from single-cell multiome data, achieving a fourfold to sevenfold relative increase in accuracy over existing methods [3]. Unlike approaches that rely on gene expression data alone, LINGER integrates single-cell paired gene expression and chromatin accessibility data while incorporating atlas-scale external bulk data across diverse cellular contexts [3]. This approach addresses a fundamental challenge in GRN inference: learning complex regulatory mechanisms from limited independent data points. The method incorporates prior knowledge of transcription factor (TF) motifs as a manifold regularization, significantly enhancing prediction accuracy for both cis-regulatory and trans-regulatory interactions [3].

LINGER employs a lifelong learning strategy (also called continuous learning), where knowledge learned from past data (external bulk datasets) helps learn new tasks (single-cell data) with limited data more effectively [3]. The framework constructs GRNs containing three types of interactions: trans-regulation (TF-TG), cis-regulation (RE-TG), and TF-binding (TF-RE), providing a comprehensive view of gene regulatory mechanisms [3]. After initial GRN inference from reference single-cell multiome data, LINGER enables estimation of transcription factor activity solely from bulk or single-cell gene expression data, leveraging abundant gene expression datasets to identify driver regulators in case-control studies [3].

Step-by-Step Protocol

Input Data Requirements and Preprocessing

- Single-cell multiome data: Input data should include count matrices of gene expression and chromatin accessibility along with cell type annotations [3]. The data should be preprocessed using standard single-cell analysis pipelines, including quality control, normalization, and feature selection [35].

- External bulk data: Collect large-scale external bulk data from sources like the ENCODE project, which contains hundreds of samples covering diverse cellular contexts [3]. This data will be used for pre-training.

- Prior knowledge bases: Compile TF motif information from databases such as JASPAR or CIS-BP to inform TF-RE connections [3].

- Validation data: For performance assessment, collect independent validation datasets such as ChIP-seq data for trans-regulatory validation and eQTL data (from GTEx or eQTLGen) for cis-regulatory validation [3].

Model Architecture and Training

Table 1: LINGER Model Components and Their Functions

| Component | Architecture | Function | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| BulkNN | Three-layer neural network | Pre-training using external bulk data | Layer weights and biases |

| scNN | Three-layer neural network | Single-cell data refinement | Regulatory module parameters |

| Manifold Regularization | Motif-based constraint | Enrichment of TF motifs binding to REs in same regulatory module | Regularization strength |

| EWC Loss | Elastic Weight Consolidation | Preservation of knowledge from bulk data during single-cell training | Fisher information matrix |

Pre-training on bulk data: Initialize the neural network model (BulkNN) to predict target gene (TG) expression using TF expression and regulatory element (RE) accessibility as input. Train this model on the external bulk data to learn initial regulatory relationships [3].

Refinement on single-cell data: Apply elastic weight consolidation (EWC) loss to refine the model on single-cell data while preserving knowledge gained from bulk data [3]. The EWC regularization uses the Fisher information to determine the magnitude of parameter deviation, encouraging the posterior distribution to remain close to the prior distribution derived from bulk data [3].

Regulatory strength inference: After training, infer the regulatory strength of TF-TG and RE-TG interactions using Shapley values, which estimate the contribution of each feature for each gene [3]. Calculate TF-RE binding strength from the correlation of TF and RE parameters learned in the second layer of the neural network [3].

Network Construction and Validation

GRN assembly: Construct cell population GRNs, cell type-specific GRNs, and cell-level GRNs based on the general GRN and cell type-specific profiles derived from the model [3].

Performance validation: Validate trans-regulatory inferences against ChIP-seq data by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPR) ratio [3]. For cis-regulatory inferences, assess consistency with eQTL studies by grouping RE-TG pairs by distance and comparing AUC and AUPR ratios across different distance groups [3].

Downstream analysis applications:

Figure 2: LINGER Workflow for GRN Inference. This diagram illustrates the lifelong learning approach that integrates external bulk data and TF motif information with single-cell multiome data to infer gene regulatory networks at multiple resolutions.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Single-Cell Multiome GRN Inference

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Multiome | Simultaneous profiling of gene expression and chromatin accessibility from the same single cell | 10x Genomics |

| ENCODE Consortium Data | Atlas-scale external bulk data for pre-training | ENCODE Project |

| ChIP-seq Validation Data | Ground truth for trans-regulatory interactions | Cistrome Data Browser |

| eQTL Data (GTEx/eQTLGen) | Validation of cis-regulatory predictions | GTEx Portal, eQTLGen |

| TF Motif Databases | Prior knowledge for TF-RE connections | JASPAR, CIS-BP |

Protocol 2: Constructing and Analyzing Attractor Landscapes in Breast Cancer

Background and Biological System

The attractor landscape framework provides particular insight into cancer heterogeneity, where multiple cell states coexist within tumors and contribute to therapy resistance and cancer recurrence [33]. In a recent study of breast cancer subtypes, researchers investigated how NF-κB epigenetic variability contributes to progression of the HER2+ BC subtype toward a more aggressive triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) phenotype [33]. The study focused on a GRN involving NF-κB and key epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) transcription factors TWIST1, SIP1, and SLUG, which constitute a broader regulatory network active across diverse tumor contexts [33].

This GRN exhibits an epigenetic landscape with two attractor basins corresponding to the observed expression profiles of HER2+ and TNBC subtypes, separated by an unstable stationary state [33]. The research demonstrated that stochastic fluctuations in NF-κB levels induce spontaneous irreversible transitions from HER2+ to TNBC attractor basins at different times, contributing to subtype heterogeneity [33]. This system provides an excellent model for studying attractor dynamics in a pathological context and illustrates how the Waddington landscape framework can explain cellular plasticity and fate transitions in cancer.

Step-by-Step Protocol for Landscape Construction

GRN Model Specification

Network definition: Construct a GRN model that includes NF-κB (p65:p50 heterodimer) as a key regulator that activates expression of TWIST1, SNAIL, and SLUG, as well as its own subunits p50 and p65 through positive feedback [33].

Ordinary Differential Equations: Implement ODEs based on the regulatory interactions. For a general GRN with genes ( x1, x2, ..., xn ), the system can be described by: [ \frac{dxi}{dt} = Fi(x1, x2, ..., xn) - \gammai xi ] where ( Fi ) represents the regulatory logic governing production and ( \gammai ) represents degradation [33].

Parameter calibration: Calibrate model parameters using experimentally measured RNA levels of all network components across the cell types of interest (e.g., HER2+ and TNBC subtypes) simultaneously [33]. Fine-tune parameters to reproduce temporal dynamics, such as recovery times after perturbation with NF-κB inhibitor DHMEQ [33].

Landscape Mapping and Analysis

Stationary state identification: Solve the algebraic equations derived from the ODE system (set ( dx/dt = 0 )) to find all stationary states [33]. Characterize the stability of each state by analyzing the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix.

Stochastic simulations: Perform numerous stochastic simulations (e.g., 10,000 simulations) starting from different uniformly distributed initial conditions in the phase space [33]. Use methods like the Gillespie algorithm or Langevin dynamics to incorporate intrinsic noise.

Landscape visualization: Construct the epigenetic landscape by calculating the probability distribution of states from the stochastic simulations [33]. Visualize the landscape in 2D or 3D projections using key genes or factors as axes (e.g., p50 vs p65) [33].

Transition analysis: Simulate long-term single-cell trajectories to observe spontaneous transitions between attractor basins [33]. Analyze the directionality and timing of these transitions, noting that irreversible transitions indicate asymmetry in the landscape topography.

Experimental Validation

Perturbation experiments: Treat cells with pathway-specific inhibitors (e.g., DHMEQ for NF-κB inhibition) and measure recovery dynamics of network components [33]. Compare experimental recovery times with model predictions.

Single-cell analysis: Use single-cell RNAseq to characterize heterogeneity in patient samples and cell lines [33]. Analyze correlation patterns between network components (e.g., p65 and p50) across different subtypes, as more symmetric attractor basins may exhibit lower correlation [33].

Attractor stability assessment: Evaluate how mutations or drugs alter attractor basin sizes and transition probabilities by measuring their effects on gene expression patterns and subtype proportions [33].

Figure 3: GRN Model for Breast Cancer Subtypes. This network diagram shows the key regulatory interactions in the NF-κB-centered GRN that generates two attractor states corresponding to HER2+ and TNBC breast cancer subtypes.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Breast Cancer Attractor Landscape Study

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Cell Lines | Model systems for different subtypes (HCC-1954 for HER2+, MDA-MB-231 for TNBC) | ATCC |

| NF-κB Inhibitor (DHMEQ) | Perturbation agent to test network dynamics and recovery | Commercial suppliers |

| qPCR Reagents | Quantification of NF-κB, TWIST1, SNAIL, and SLUG expression | Various manufacturers |

| Single-cell RNAseq Kits | Characterization of heterogeneity in cell populations | 10x Genomics, Parse Biosciences |

Protocol 3: Quantum Algorithms for Attractor Identification in Boolean GRN Models

Background and Principles

Boolean networks (BNs) provide a powerful, coarse-grained approach to modeling GRNs, where genes are represented as binary agents (ON/OFF) and their interactions are captured through Boolean functions [36]. In this framework, attractors—stable states or cycles of states of the system—are associated with biological phenotypes, making their identification crucial for understanding cellular differentiation and fate decisions [36]. However, traditional computing approaches struggle with the exponential growth of the state space in such models (with ( 2^n ) possible states for n genes), limiting exhaustive simulations to relatively small networks (typically ( n \leq 29 )) [36].

A novel quantum search algorithm has been developed for identifying attractors in synchronous Boolean networks, offering potential advantages for analyzing larger GRNs [36]. This algorithm uses iterative quantum amplitude suppression to systematically identify all attractors of a Boolean network, with each run guaranteed to discover a new attractor [36]. The approach demonstrates strong resilience to noise on current NISQ (noisy intermediate-scale quantum) devices, making it a promising advance toward practical quantum-enhanced biological modeling [36].

Step-by-Step Protocol

Boolean Network Formulation

Gene binarization: Convert gene expression data to binary values (ON/OFF) using appropriate thresholding methods. For single-cell data, this can be based on expression levels relative to cell population distributions.

Boolean function definition: For each gene, define a Boolean function that determines its state based on the states of its regulators. These functions can be derived from known regulatory interactions or inferred from data.

Update scheme specification: Implement a synchronous update scheme where all genes are updated simultaneously at each time step based on the current state of the system [36].

Quantum Algorithm Implementation

Qubit initialization: Initialize the qubit system to a superposition of all possible states using Hadamard gates applied to each qubit [36]. For n genes, this creates a superposition of all ( 2^n ) possible states.

Boolean function application: Implement the Boolean functions as quantum gates that evolve the superposition state [36]. Each possible network state evolves into its corresponding time-evolved state according to the synchronous update rules.

Iterative amplitude suppression:

- Run the algorithm and measure to identify the first attractor.

- Apply quantum amplitude suppression to iteratively suppress known attractor basins, increasing the probability of detecting new ones in subsequent runs [36].

- Repeat until all attractors are identified, with each run guaranteed to find a new attractor [36].

Noise mitigation: Implement error mitigation strategies tailored to the specific quantum hardware being used, as the algorithm has shown robustness to noise on current NISQ devices like the ibm_brisbane processor [36].

Validation and Analysis

Classical verification: For small networks, verify quantum algorithm results using classical methods such as the BoolNet package in R [36].

Biological interpretation: Map identified attractors to known or potential cellular phenotypes based on their gene expression patterns.

Basin analysis: Analyze the size and structure of attractor basins to assess the relative stability of different cellular states.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Computational Resources for Quantum-Enhanced GRN Analysis

| Resource | Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Computing Simulators | Algorithm development and testing without quantum hardware | Qiskit, Cirq, Forest |

| IBM Quantum Processors | Implementation and execution of quantum algorithms | IBM Quantum Experience |

| BoolNet R Package | Classical verification of attractor identification | CRAN Repository |

| Quantum Algorithm Libraries | Pre-built functions for quantum amplitude suppression | Open-source quantum computing libraries |

The Waddington landscape framework provides a powerful conceptual and quantitative approach for understanding cellular differentiation and fate decisions in the context of gene regulatory networks. The protocols outlined here—ranging from GRN inference using cutting-edge machine learning methods like LINGER to attractor landscape construction in specific biological systems and the emerging application of quantum algorithms for attractor identification—provide researchers with practical tools for applying this framework to their specific research questions.

The integration of single-cell multi-omics data with increasingly sophisticated computational methods is transforming the Waddington landscape from a qualitative metaphor to a quantitative, predictive framework [3] [35]. This enables not only deeper understanding of developmental processes and disease mechanisms but also practical applications in drug development and cellular reprogramming. As these methods continue to evolve, particularly with advances in quantum computing and AI-driven modeling, we anticipate increasingly accurate and comprehensive reconstructions of epigenetic landscapes that will further illuminate the fundamental principles governing cellular identity and fate decisions.

A Toolkit for Discovery: Methodological Approaches for GRN Inference from Multi-Omics Data

In evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), understanding the gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that control cellular identity and morphological diversity is a fundamental pursuit. The advent of single-cell multi-omics technologies, which allow for the simultaneous measurement of a cell's transcriptome and epigenome (e.g., via paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq), has provided the data necessary to reconstruct these networks with unprecedented resolution [3] [37]. The computational challenge lies in accurately inferring the causal regulatory relationships between transcription factors (TFs), cis-regulatory elements (CREs), and their target genes from these sparse and noisy data. This has led to the development of diverse computational approaches, each with distinct foundations and assumptions, which are critically assessed in this application note.

Methodological Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Computational methods for GRN inference from single-cell multi-omics data can be broadly categorized into several paradigms. The table below summarizes the core principles, key tools, and specific applications of these foundational approaches.

Table 1: Foundational Computational Approaches for GRN Inference from Single-Cell Multi-omics Data

| Methodological Foundation | Core Principle | Representative Tools | Application in GRN Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation & Association | Identifies co-variation or spatial association between TF expression/activity and target gene expression, or between chromatin accessibility and gene expression. | scSAGRN [37], PCC [3] | Infers TF-gene and peak-gene linkages based on statistical dependencies, often using neighborhood information from integrated data. |

| Regression Models | Models the expression of a target gene as a linear or non-linear function of the expression levels of TFs and the accessibility of CREs. | Elastic Net, LINGER (initial layer) [3] | Directly predicts gene expression from regulator activities, with coefficients interpreted as regulatory strengths. |

| Probabilistic Models | Uses a Bayesian framework to integrate multi-omics data and prior knowledge (e.g., known GRNs, motifs) to infer a posterior probability of regulatory interactions. | PRISM-GRN [4], BREM-SC [38] | Provides robust, interpretable GRN inference with inherent uncertainty quantification, valuable for sparse single-cell data. |