Decoding Complexity: Unraveling the Genetic Architecture of Human Phenotypes for Drug Discovery and Precision Medicine

This article synthesizes current advancements in defining the genetic architecture of complex human phenotypes, a cornerstone for modern therapeutic discovery.

Decoding Complexity: Unraveling the Genetic Architecture of Human Phenotypes for Drug Discovery and Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article synthesizes current advancements in defining the genetic architecture of complex human phenotypes, a cornerstone for modern therapeutic discovery. We explore foundational concepts of polygenicity and heritability, detailing how methodological innovations in GWAS, whole-genome sequencing, and polygenic risk scoring are translating genetic insights into clinical applications. The content addresses critical challenges including population diversity, rare variant interpretation, and data integration, while providing a comparative framework for validating genetic findings across studies and populations. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review highlights how a refined understanding of genetic architecture is revolutionizing target identification, risk prediction, and the development of precision medicine strategies.

Blueprints of Inheritance: Core Principles and Evolutionary Forces Shaping Complex Traits

The term genetic architecture refers to the complete genetic basis underlying a phenotypic trait and encompasses key parameters such as the number of genetic variants involved (polygenicity), their individual effect sizes, their allele frequencies, and the interactions between them [1] [2]. Understanding genetic architecture is not merely an academic exercise; it is fundamental for predicting disease risk, interpreting the functional consequences of genetic variation, and developing targeted therapeutic strategies. For complex phenotypes—those not governed by single-gene Mendelian inheritance—the genetic architecture was historically theorized by R.A. Fisher as being influenced by many loci with small, additive effects. However, contemporary large-scale genomic studies reveal a more nuanced picture, showing that architectures vary widely among traits and are controlled by evolvable principles [2].

This guide synthesizes current research to provide a technical framework for defining and measuring the core components of genetic architecture. We focus specifically on the interrelated concepts of polygenicity, heritability, and effect size distributions, framing this discussion within the broader context of complex phenotype research. The insights herein are critical for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to bridge the gap between statistical genetic associations and biological mechanism.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Polygenicity

Polygenicity describes the number of independent genetic loci that contribute to the variation of a trait. Highly polygenic traits are influenced by thousands of genetic variants spread across the genome. The level of polygenicity is not static but can evolve in response to selection pressures. A foundational population-genetic model suggests a non-monotonic relationship between selection strength and the number of contributing loci: traits under moderate selection tend to be encoded by the greatest number of loci with highly variable effects, whereas those under very strong or weak selection are controlled by relatively fewer loci [2].

Heritability

Heritability quantifies the proportion of total phenotypic variance in a population that is attributable to genetic variation. Two primary definitions are used:

- Broad-sense heritability (H²): Includes all genetic contributions (additive, dominant, epistatic).

- Narrow-sense heritability (h²): Considers only the additive genetic variance, which is the component responsible for the predictable response to selection and is most frequently estimated in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [3].

SNP-based heritability (h²ₛₙₚ), estimated from genome-wide genotype data, reflects the proportion of variance captured by common variants and is a key metric for understanding the missing heritability problem [4] [3].

Effect Size Distributions

The effect size distribution refers to the spectrum of magnitudes with which individual genetic variants influence a trait. Despite the highly polygenic nature of most complex traits, heritability is often unevenly distributed across the genome. It is now well-established that for many traits, a small number of loci with relatively larger effects coexist with a long tail of loci with very small effects [1] [5]. The shape of this distribution has profound implications for the statistical power of GWAS and for predicting the potential yield of therapeutic targets.

Current Research and Quantitative Findings

Recent large-scale studies have begun to reveal unifying principles governing genetic architectures across diverse traits.

Scaling Laws in Genetic Architecture

A 2025 analysis of 95 complex traits from the UK Biobank proposed that simple scaling laws control their genetic architectures. The study found that while traits appear to have widely divergent architectures in terms of significant hits, these differences arise mainly from two scaling parameters: the mutational target size and the heritability per site. When these two factors are accounted for, the underlying architectures of all 95 traits are remarkably similar, implying a shared distribution of selection coefficients across traits [1].

Empirical Evidence from Brain and Metabolite Studies

Table 1: Heritability Estimates from Recent Large-Scale Studies

| Phenotype Category | Specific Traits / Measures | Sample Size | Mean/Reported Heritability (h²) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain White Matter Connectome [4] | Node-level connectivity | 30,810 adults | 18.5% (range: 7.8% - 29.5%) | 90/90 node-level measures were significantly heritable. |

| Edge-level connectivity | 30,810 adults | 9.6% (range: 4.6% - 29.5%) | 851/947 edge-level connections were significantly heritable. | |

| Plasma Metabolome [6] | 249 metabolic measures & 64 ratios | 254,825 individuals | Median: 12.32% | Heritability varied by category; Lipids & Lipoproteins were highest (14.33%). |

| Lipoprotein and Lipid metabolites | 254,825 individuals | 14.33% | Demonstrated high polygenicity and pleiotropy. | |

| Cognitive Ability [7] | Latent common factor (from Genomic SEM) | Multi-trait; up to ~850k | 50-80% (from prior twin studies) | Multivariate GWAS identified 3,842 significant loci. |

- Brain Connectivity: A tractography study of 30,810 UK Biobank participants demonstrated that the structural connectome is a heritable trait. The study found that the number of associated genetic loci for a given connectivity measure was proportional to its heritability estimate, illustrating the link between polygenicity and heritability [4].

- Plasma Metabolome: A GWAS of 249 metabolic measures in 254,825 individuals revealed a complex architecture characterized by extensive polygenicity and pleiotropy. The median heritability was 12.32%, with significant variability across metabolite categories. The TRIB1 gene locus exhibited the most extensive pleiotropy, being associated with 255 traits across 9 categories [6].

- Cognitive Abilities: A multivariate GWAS using Genomic Structural Equation Modeling (Genomic SEM) integrated data from six cognitive-related traits (e.g., intelligence, educational attainment). This approach identified 3,842 genome-wide significant loci, providing evidence for a shared genetic architecture underlying diverse cognitive functions [7].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Accurately defining genetic architecture requires a suite of sophisticated statistical genetic methods.

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

Protocol Overview: GWAS tests for statistical associations between millions of genetic variants (typically SNPs) and a phenotype across a large population.

- Genotyping and Imputation: Participants are genotyped using microarray chips. Genotype imputation is then performed against a reference panel (e.g., 1000 Genomes) to infer ungenotyped variants.

- Quality Control (QC):

- Sample QC: Remove individuals with high missingness, sex discrepancies, abnormal heterozygosity, or non-target ancestry.

- Variant QC: Exclude SNPs with low call rate (e.g., < 95%), low minor allele frequency (e.g., MAF < 1%), or significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

- Association Testing: Each SNP is tested individually for association with the phenotype, using a linear or logistic regression model adjusted for covariates (e.g., age, sex, genetic principal components to control for population stratification).

- Meta-analysis: If data comes from multiple cohorts, summary statistics from each are combined to increase power.

- Significance Thresholding: A genome-wide significance threshold (typically p < 5 × 10⁻⁸) is applied to account for multiple testing.

Heritability and Local Heritability Estimation

- SNP-Based Heritability (h²ₛₙₚ): Commonly estimated using LD Score Regression (LDSC), which leverages the fact that a SNP's GWAS test statistic is inflated by its linkage disequilibrium (LD) with other causal variants. The slope of the regression of χ² statistics on LD scores provides an estimate of h²ₛₙₚ [4] [6].

- Conditional Local Heritability: Advanced methods, such as the Effective Heritability Estimator (EHE), use GWAS p-values to estimate the heritability attributable to a specific gene or small genomic region while conditioning out the effects of nearby genes. This allows for high-resolution mapping of functional genes [5].

Fine-Mapping and Causal Variant Identification

Protocol Overview: Following GWAS, fine-mapping is used to prioritize likely causal variants within an associated locus.

- Define Locus Regions: Identify genomic regions (e.g., ±500 kb around lead GWAS SNPs) containing associated variants in high LD.

- Credible Set Analysis: Use statistical fine-mapping tools like FINEMAP [6] or SuSiE to compute a posterior probability for each variant in the region being the causal driver. A 95% credible set contains the minimal set of variants that have a 95% probability of including the true causal one.

- Functional Annotation: Annotate variants in the credible set using data from resources like ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics, and GTEx to assess their potential regulatory impact (e.g., overlap with promoter marks, enhancers, or protein-binding sites).

Multivariate Genetic Analysis

Protocol Overview: Genomic Structural Equation Modeling (Genomic SEM) [7] This method integrates GWAS summary statistics of multiple correlated traits to model their shared genetic structure.

- Input Data Collection: Gather GWAS summary statistics for related traits (e.g., intelligence, educational attainment, processing speed).

- Genetic Covariance Estimation: Use LDSC to estimate the genetic covariance and variance-covariance matrix (S) between the traits.

- Model Specification: Define a structural equation model that reflects the hypothesized relationships between a latent factor (e.g., "general cognitive ability") and the observed traits.

- Model Fitting: Fit the model to the genetic covariance matrix S to obtain GWAS summary statistics for the latent common factor.

- Post-GWAS Analysis: The resulting factor GWAS can be subjected to the same downstream analyses (fine-mapping, heritability estimation, etc.) as a univariate GWAS.

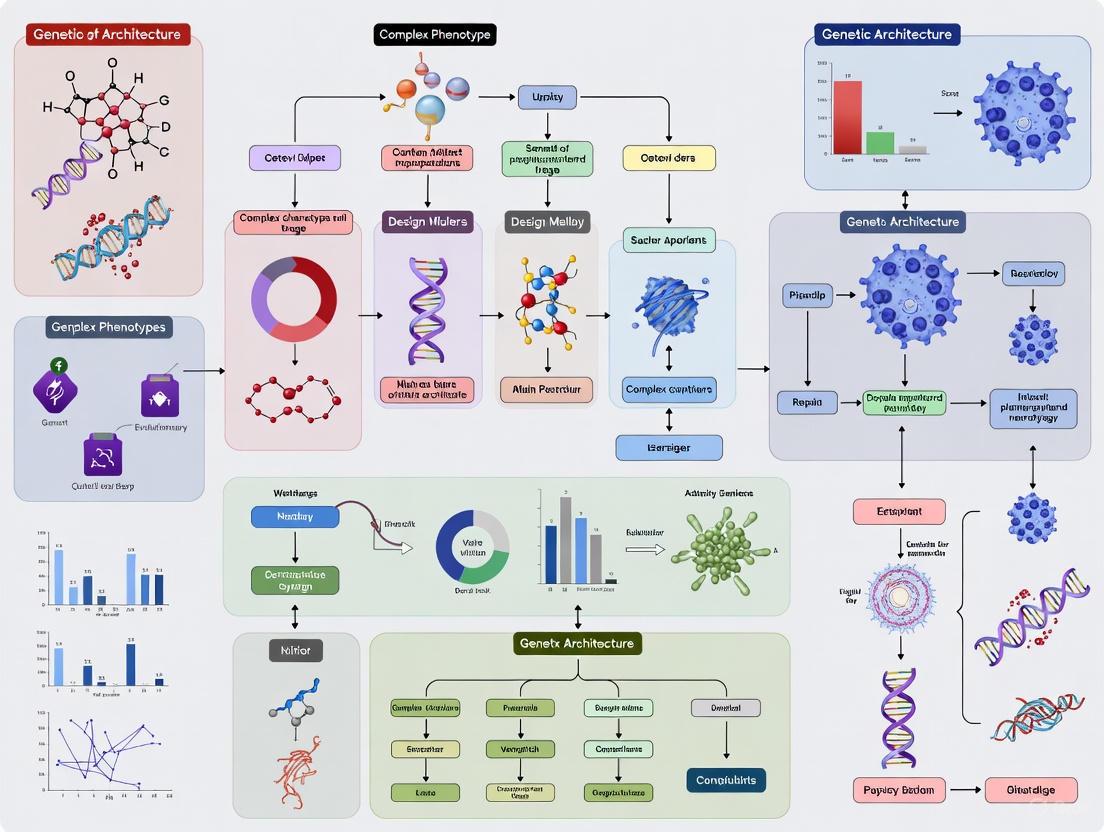

The following workflow diagram illustrates the progression from raw data to the interpretation of genetic architecture.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Genetic Architecture Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Genetic Architecture Research

| Resource / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biobanks & Cohort Data | UK Biobank [4] [6], FinnGen, All of Us | Provide large-scale, deeply phenotyped cohorts with genomic data essential for powerful GWAS and heritability estimation. |

| Genotyping Arrays | Illumina Global Screening Array, UK Biobank Axiom Array | Microarray chips for high-throughput, cost-effective genotyping of common SNPs across the genome. |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing | UK Biobank WES data [6] | Identifies rare coding variants that are typically missed by GWAS but can have significant functional impacts. |

| LD Reference Panels | 1000 Genomes Project [7], UK10K, Haplotype Reference Consortium | Provide population-specific haplotype information crucial for genotype imputation and LDSC. |

| GWAS & QC Software | PLINK, SNPTEST, R | Perform quality control, association testing, and basic statistical analysis of genetic data. |

| Heritability & Genetic Correlation | GCTA [4], LD Score Regression (LDSC) [6], Genomic SEM [7] | Estimate SNP-based heritability and genetic correlations between traits from summary statistics. |

| Fine-Mapping Tools | FINEMAP [6], SuSiE | Statistically prioritize putative causal variants within a GWAS locus. |

| Functional Annotation Databases | GTEx, ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics | Annotate non-coding variants with regulatory genomic information (e.g., eQTLs, chromatin states). |

Visualization of Multivariate Genetic Analysis

The following diagram outlines the specific process of Genomic SEM, a key method for analyzing the shared genetic architecture of correlated traits.

Diagram Title: Genomic SEM Model for Cognitive Traits

The field of complex trait genetics is moving beyond simply cataloging associated loci toward a principled understanding of the scaling laws and evolutionary forces that shape genetic architectures [1] [2]. The core parameters of polygenicity, heritability, and effect size distributions are not independent but are interconnected properties that arise from a trait's mutational target size, its relationship with fitness, and its underlying biological complexity.

Future research will increasingly rely on multivariate methods [7] and the integration of multi-omics data to move from genetic associations to causal genes and biological pathways. This deeper understanding, facilitated by the methodologies and resources detailed in this guide, is the foundational step toward translating genetic discoveries into actionable insights for human health and disease treatment.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the genetic architecture of complex phenotypes. Since the landmark 2005 study on age-related macular degeneration, GWAS has evolved from a novel approach to a cornerstone of genetic epidemiology [8]. This methodology enables the systematic interrogation of hundreds of thousands to millions of genetic variants across the genome to identify associations with diseases and quantitative traits. The GWAS framework rests on the common disease-common variant hypothesis, providing an unbiased discovery platform without prior biological hypotheses about candidate genes.

Over the past two decades, GWAS has matured through technological and methodological advancements. Initial studies utilizing single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-arrays containing a few hundred thousand markers have evolved to leverage imputation techniques that increase effective marker density, improve statistical power, and enable large-scale meta-analyses [9]. More recently, advances in sequencing technologies have allowed GWAS to assess the contribution of low-frequency and rare variants to complex trait architecture [9]. The accumulation of these efforts is embodied in resources like the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog, which serves as a central repository for statistically significant SNP-trait associations [10].

For researchers investigating the genetic architecture of complex phenotypes, GWAS provides an essential starting point for mapping the polygenic foundations of human traits. The field has progressed from discovering individual loci to characterizing entire genetic networks underlying disease susceptibility, with implications for drug target identification, risk prediction, and biological mechanism elucidation.

Current Landscape of GWAS Discoveries

The scale of GWAS discoveries has expanded dramatically since its inception. As of late 2024, the GWAS Catalog contained thousands of publications with full summary statistics available for numerous traits and diseases [10]. While the exact numbers referenced in the title (185,864 associations across 4,554 traits) represent a specific snapshot in time, the Catalog continues to grow as new studies are published. The traits investigated span conventional medical endpoints (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes) to behavioral and physiological measurements [8].

The GWAS Catalog employs the Experimental Factor Ontology (EFO) to standardize trait terminology, facilitating search and comparison across studies [11]. This ontological framework organizes traits hierarchically, with parent categories (e.g., "hypertension") encompassing more specific child terms (e.g., "treatment-resistant hypertension") [11]. This structure enables researchers to navigate related genetic associations across different levels of phenotypic specificity.

Methodological Evolution and Technological Advances

GWAS methodology has undergone significant refinement since its introduction:

- Genotyping Arrays: Early arrays contained approximately 100,000 to 1 million SNPs, while modern arrays include up to 2 million markers with improved genomic coverage [9].

- Imputation: Statistical imputation of untyped SNPs using reference panels (1000 Genomes, TOPMed) has dramatically increased marker density, enabling meta-analyses across platforms and enhancing fine-mapping resolution [9].

- Sequencing-Based GWAS: Declining sequencing costs have facilitated GWAS using whole genome or exome sequencing, allowing assessment of low-frequency (0.5% ≤ MAF < 5%) and rare (MAF < 0.5%) variants [9].

- Multivariate Methods: Approaches like Genomic Structural Equation Modeling (Genomic SEM) enable integrated analysis of multiple correlated traits, uncovering shared genetic architecture [7].

Table 1: Key Technological Developments in GWAS

| Technology | Time Period | Key Advancement | Impact on GWAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNP Arrays | 2005-2010 | Genome-wide coverage with 100K-1M SNPs | Enabled first GWAS discoveries |

| Statistical Imputation | 2010-present | Reference panels (1000G, TOPMed) | Increased effective marker density 10-100x |

| Array Customization | 2015-present | Population-specific content (e.g., H3Africa array) | Improved discovery in diverse populations |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | 2018-present | Direct assay of all variants | Assessment of rare variants (MAF < 0.5%) |

| Advanced Multivariate Methods | 2020-present | Genomic SEM, MTAG | Detection of cross-trait genetic sharing |

Persistent Challenges in Contemporary GWAS

Despite substantial progress, GWAS faces several persistent obstacles that limit its translational potential and scientific impact.

Four Foundational Obstacles

Recent analyses have identified "Four Persistent Obstacles" that continue to hinder GWAS progress [8]:

Technological Inertia: Despite the availability of improved genomic resources (GRCh38, T2T-CHM13, pangenome assemblies), most GWAS summary statistics still rely on the GRCh37 (2009) reference genome. Widely used tools like PLINK and PheWeb utilize restrictive REF/ALT formats that inadequately represent structural variants and pan-genomic diversity [8].

LD Bottleneck: Linkage disequilibrium (LD) continues to complicate post-GWAS analyses. The field lacks standardized LD reference resources, with popular tools (LDSC, LDPred, LDGM) each employing distinct LD reference files and formats. As sequencing resolution improves and diverse populations are studied, reliance on massive LD matrices becomes computationally prohibitive [8].

Prioritizing Heritability Over Actionability: The longstanding focus on "missing heritability" has diverted attention from clinical utility. For example, the identification of >12,000 SNPs for height explains most common SNP-based heritability but offers limited clinical applications for individuals concerned about growth patterns [8].

Inadequate Diversity for Equity: Approximately 80% of GWAS participants have European ancestry, creating major limitations for generalizability and equity. This underrepresentation can lead to false pathogenic classifications and missed population-specific biology [8].

Translational Limitations

The March 2025 bankruptcy of 23andMe serves as a stark reminder of the limited translational value of GWAS to the general public [8]. While polygenic risk scores (PRS) theoretically offer disease prediction potential, their clinical implementation remains limited. Similarly, despite numerous drug targets identified through GWAS (e.g., IL6R for rheumatoid arthritis, CYP2C19 for clopidogrel metabolism), few blockbuster drugs have directly emerged from GWAS findings compared to targets discovered through other approaches (e.g., PCSK9 discovered pre-GWAS) [8].

Methodological Framework: GWAS Workflows and Analytical Approaches

Core GWAS Workflow

The fundamental GWAS workflow involves multiple standardized steps from study design through interpretation. The diagram below outlines this process:

Diagram 1: Standard GWAS workflow showing key stages from study design to functional validation.

Advanced Multivariate Methods

For analyzing shared genetic architecture across traits, Genomic Structural Equation Modeling (Genomic SEM) has emerged as a powerful approach. The methodology applied in a recent cognitive abilities study illustrates this framework [7]:

Input Data Sources: The analysis integrated six cognitive-related trait GWAS:

- Intelligence (n = 110,988)

- Executive Function (n = 266,413)

- Processing Speed (n = 119,671)

- Educational Attainment (n = 848,919)

- Memory Performance (n = 162,335)

- Reaction Time (n = 432,297) [7]

Quality Control Procedures:

- SNP-level filtering (MAF > 0.01, INFO > 0.8)

- Exclusion of MHC region due to complex genetic architecture

- Removal of strand-ambiguous and palindromic SNPs

- Harmonization of effect alleles across studies [7]

Analytical Implementation: The Genomic SEM R package (v.0.0.5) was employed to model latent genetic factors underlying correlated cognitive phenotypes. The method uses LD Score regression to estimate genetic covariance matrices, accounting for sample overlap between constituent GWAS [7]. This approach identified 3,842 genome-wide significant loci, including 275 novel loci for cognitive ability [7].

Mendelian Randomization for Causal Inference

Mendelian Randomization (MR) uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to infer causal relationships between modifiable exposures and health outcomes. A recent MR study investigating gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and extraesophageal diseases exemplifies this approach [12]:

Study Design Principles: MR must satisfy three core assumptions: (1) genetic variants strongly associate with the exposure (GERD); (2) variants influence outcomes only through the exposure; (3) variants are independent of confounders [12].

Instrument Selection:

- SNPs significantly associated with GERD (P < 5 × 10⁻⁸)

- LD clumping (r² < 0.001, window = 10,000 kb)

- Exclusion of palindromic and strand-ambiguous SNPs

- F-statistic > 10 to ensure strong instruments [12]

MR Estimation Methods:

- Inverse-variance weighted (IVW) as primary method

- MR-Egger regression to assess directional pleiotropy

- Weighted median for robustness to invalid instruments

- MR-PRESSO to identify and remove outliers [12]

This GERD analysis demonstrated causal relationships with multiple extraesophageal conditions including chronic rhinitis (OR = 1.482), asthma (OR = 1.539), and throat/chest pain (OR = 1.585) [12].

Post-GWAS Analysis Framework

Advanced Analytical Pathways

Following initial GWAS discovery, numerous post-GWAS analytical methods extract additional biological insights. The relationships between these approaches are illustrated below:

Diagram 2: Post-GWAS analytical framework showing pathways from primary analysis to biological translation.

The analysis of GWAS summary statistics has spawned a specialized software ecosystem. A recent systematic review identified 305 functioning software tools and databases dedicated to GWAS summary statistics analysis [13]. These can be categorized by functionality:

Table 2: Categories of GWAS Summary Statistics Tools

| Category | Subcategory | Example Tools | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Management | Quality Control | GWAS-SSF | Standardize format and quality metrics |

| Imputation | Genotype reconstruction from summary data | ||

| Single-Trait Analysis | Fine-mapping | Identify causal variants from LD blocks | |

| Heritability Estimation | LDSC | Partition genetic variance | |

| Gene-based Tests | Aggregate variant effects to gene level | ||

| Multiple-Trait Analysis | Genetic Correlation | Estimate genetic overlap between traits | |

| Pleiotropy Analysis | Genomic SEM | Detect variants affecting multiple traits | |

| Mendelian Randomization | MR-PRESSO | Infer causal relationships | |

| Colocalization | Test shared causal variants across traits |

Most tools (56.4%) are implemented in R, with smaller proportions in Python (12.5%) and C/C++ (8.2%) [13]. The majority were published after 2015, reflecting rapid methodological development in this domain [13].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GWAS

| Category | Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Arrays | H3Africa Custom Array | Population-specific variant content | Improved discovery in African ancestry cohorts [9] |

| Global Screening Array | Standardized genome-wide content | Large-scale biobank studies | |

| Reference Genomes | GRCh37/hg19 | Legacy reference assembly | Compatibility with existing summary statistics [8] |

| T2T-CHM13 | Complete telomere-to-telomere | Resolution of complex genomic regions [8] | |

| LD Reference Panels | 1000 Genomes Project | Multi-ancestry LD patterns | Imputation and heritability analysis [7] |

| TOPMed | Diverse deeply sequenced panel | Enhanced imputation accuracy [9] | |

| Analysis Software | PLINK | Core GWAS analysis | Quality control and association testing [8] |

| Genomic SEM (R) | Multivariate genetic analysis | Modeling shared genetic architecture [7] | |

| SDPR_admix | Polygenic prediction | Risk scoring in admixed populations [14] | |

| Functional Annotation | eQTL Catalog | Expression quantitative trait loci | Linking variants to gene regulation [9] |

| PhenoScanner | Variant-phenotype database | Pleiotropy and confounding assessment [12] |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence Integration

Artificial intelligence approaches are increasingly being integrated into GWAS pipelines. AI-based methods show particular promise for predicting functional impacts of non-coding variants, integrating multi-omics data, and learning complex LD patterns without explicit enumeration [8]. Tools like GeneMANIA, PhenoScanner, and STRING already incorporate AI elements for functional inference [9]. The unprecedented success of AlphaFold in protein structure prediction suggests similar approaches could revolutionize functional interpretation of non-coding GWAS hits [8].

Improving Diversity and Equity

Addressing the Eurocentric bias in GWAS represents both a scientific and moral imperative. Recent initiatives (H3Africa, TOPMed, All of Us) are expanding genomic research in underrepresented populations [9]. Methodological innovations like SDPR_admix improve polygenic prediction in admixed populations by modeling local ancestry and cross-ancestry genetic architecture [14]. In one application, this approach improved prediction accuracy approximately 5-fold in admixed individuals compared to standard methods [14].

From Association to Biological Mechanism

Future GWAS research must prioritize biological translation alongside statistical discovery. The concept of "trait efficiency locus (TEL)" has been proposed as a complement to quantitative trait locus (QTL) frameworks, emphasizing efficiency as the central metric for evaluating genetic discoveries [8]. Functional validation approaches including reporter assays, genome editing, and animal models remain essential for establishing causal mechanisms [9]. For example, rat models have identified novel IOP-related genes (Ctsc2, Plekhf2) not previously detected in human studies, demonstrating the value of complementary model systems [9].

GWAS has matured from a novel genetic approach to a fundamental tool for dissecting the architecture of complex traits. The cataloging of hundreds of thousands of statistical associations across thousands of traits represents both an extraordinary achievement and a foundation for future discovery. As the field advances, prioritizing biological translation, diversity inclusion, and clinical actionability will be essential for realizing the full potential of the GWAS revolution. The integration of artificial intelligence, advanced multivariate methods, and functional genomics will drive the next generation of discoveries, ultimately fulfilling the promise of genomics to transform our understanding of human biology and disease.

For over a decade, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified thousands of common genetic variants associated with complex diseases and traits. However, these common variants (typically defined as minor allele frequency [MAF] ≥5%) often explain only a fraction of the estimated heritability for most complex phenotypes—a challenge known as the "missing heritability" paradigm [15]. This limitation has driven researchers to investigate the role of genetic variants across the entire allele frequency spectrum, particularly low-frequency (0.5% ≤ MAF < 5%) and rare (MAF < 0.5%) variants, which are thought to contribute significantly to disease risk despite their lower population prevalence [16] [15].

The integration of low-frequency and rare variants into genetic architectural models presents both challenges and opportunities for understanding complex disease etiology. These variants often have larger effect sizes than common variants due to the influence of negative selection, which purges highly deleterious mutations from the population [16] [17]. Furthermore, because rare variants are typically younger than common variants and show greater geographic clustering, they can provide crucial insights into population-specific disease risk and recent evolutionary pressures [15]. For drug development, rare coding variants with large effects offer particularly valuable insights, as they can directly implicate specific genes and biological pathways, facilitating the identification of promising therapeutic targets [18] [15].

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for integrating low-frequency and rare variants into genetic architecture research, with a specific focus on methodological considerations, analytical approaches, and practical applications for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to elucidate the genetic underpinnings of complex phenotypes.

Defining the Variant Frequency Spectrum and Functional Enrichment

Variant Classification and Characteristics

Genetic variants are conventionally categorized based on their population frequency, which correlates with their functional impact and evolutionary history. The table below summarizes the standard classification scheme and key characteristics of variants across the frequency spectrum.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Genetic Variants by Frequency Spectrum

| Variant Category | Frequency Range (MAF) | Typical Effect Sizes | Evolutionary Pressure | Primary Identification Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common | ≥5% | Small to moderate (OR ~1.1-1.5) | Neutral to weak selection | GWAS, Imputation (1000G) |

| Low-Frequency | 0.5% - 5% | Moderate to large (OR ~1.5-3.0) | Moderate negative selection | Large-scale GWAS, Imputation (UK10K/HRC) |

| Rare | <0.5% | Large (OR >3.0) to very large | Strong negative selection | Sequencing, Custom arrays |

Functional Enrichment Across the Frequency Spectrum

The functional contribution of genetic variants differs significantly across the frequency spectrum. Partitioning heritability analyses have revealed that low-frequency and rare variants show distinct enrichment patterns in functional genomic annotations compared to common variants. For instance, non-synonymous coding variants explain approximately 17±1% of low-frequency variant heritability versus only 2.1±0.2% of common variant heritability—an 8.2-fold difference [16]. This enrichment is even more pronounced for variants predicted to be deleterious by functional prediction algorithms such as PolyPhen-2 [16].

Beyond coding regions, cell-type-specific noncoding annotations also show differential enrichment patterns. For brain-related traits, histone modification marks (e.g., H3K4me3) in relevant tissues such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex demonstrate substantially greater enrichment for low-frequency variant heritability (57±12%) compared to common variant heritability (12±2%) for traits like neuroticism [16]. These patterns reflect the action of negative selection, which more strongly constrains functional elements, leading to larger effect sizes for low-frequency and rare variants within these genomic regions.

Methodological Framework for Variant Detection and Analysis

Genomic Technologies for Variant Discovery

Three primary strategies enable comprehensive assessment of low-frequency and rare variants: genotype imputation, custom genotyping arrays, and direct sequencing.

Table 2: Genomic Technologies for Assessing Low-Frequency and Rare Variants

| Technology | Key Features | Representative Resources | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype Imputation | Cost-effective; expands SNP content of arrays using reference haplotypes | 1000 Genomes Project, UK10K, Haplotype Reference Consortium | Large cohort studies with existing array data |

| Custom Genotyping Arrays | Disease-focused; enriches standard panels with curated variants | Immunochip, Exome arrays | Targeted validation of putative associations |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing | Comprehensive; captures all variants in coding/genome | UK Biobank, TOPMed, 100,000 Genomes Project | Discovery phase; identification of novel associations |

Genotype imputation has evolved substantially with increasingly diverse and larger reference panels. The Haplotype Reference Consortium, combining low-coverage whole-genome sequencing data from multiple studies, represents the state-of-the-art, containing 64,976 haplotypes from over 39 million SNVs with minor allele count ≥5, significantly improving imputation accuracy for variants down to 0.1% MAF [15]. Population-specific reference panels (e.g., UK10K for British ancestry, Genome of the Netherlands) provide enhanced imputation accuracy within specific populations by capturing geographically clustered rare variants [15].

Analytical Methods for Rare Variant Association Testing

The statistical challenge of rare variant analysis stems from sparsity (few allele carriers) and the multiple testing burden. Rare variant association testing (RVAT) methods address this by aggregating variants within functional units (typically genes) and leveraging functional annotations to prioritize putatively impactful variants.

Table 3: Analytical Methods for Rare and Low-Frequency Variant Analysis

| Method Category | Representative Approaches | Key Principles | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burden Tests | CAST, CMC, WSS | Collapses rare variants into a single burden score; tests association between aggregate score and trait | Assumes unidirectional effects; sensitive to inclusion of non-causal variants |

| Variance Component Tests | SKAT, SKAT-O | Models variant effects as random; tests for variance component significance | Lower power when most variants in a region are causal and effects are directional |

| Annotation-Integrated Methods | STAAR, DeepRVAT | Incorporates diverse functional annotations to prioritize variants; uses machine learning frameworks | Computational complexity; requires large training datasets for optimal performance |

DeepRVAT represents a recent advancement in RVAT methodology, using a deep set neural network architecture to integrate multiple variant annotations in a data-driven manner [18]. This approach models both additive and nonlinear effects of rare variants on gene function, learning a trait-agnostic gene impairment scoring function from 34 diverse variant annotations, including:

- Variant effect predictions (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, AlphaMissense, CADD)

- Splicing effect predictions (SpliceAI, AbSplice)

- Protein structure effect predictions (PrimateAI)

- Epigenetic annotations (ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics) [18]

Applied to whole-exome sequencing data from the UK Biobank, DeepRVAT identified 272 gene-trait associations across 21 quantitative traits, representing a 75% increase in discovery yield compared to conventional burden/SKAT approaches [18].

Integrated Common and Rare Variant Analysis Frameworks

Comprehensive genetic architecture analysis requires integrated approaches that simultaneously model common, low-frequency, and rare variants. Stratified LD-score regression (S-LDSC) extended for low-frequency variants (baseline-LF model) enables partitioning of heritability across functional annotations and frequency categories [16]. This method uses a reference panel with accurate LD information for low-frequency variants (e.g., UK10K) and incorporates 163 annotations, including MAF bins and LD-related annotations, to produce robust heritability estimates [16].

For complex trait prediction, polygenic risk scores (PRS) increasingly incorporate rare variant information. Studies have demonstrated that PRS integrating rare variants can improve prediction accuracy, particularly for identifying individuals at high genetic risk, and show better cross-population generalizability compared to common-variant-only PRS [18].

Experimental Protocols for Variant Integration

Protocol 1: Extended S-LDSC for Low-Frequency Variants

Purpose: To partition the heritability of low-frequency (0.5%≤MAF<5%) and common (MAF≥5%) variants across functional annotations.

Input Data Requirements:

- GWAS summary statistics for the target trait

- LD reference panel with accurate low-frequency variant information (e.g., UK10K from 3,567 samples)

- Baseline-LF model annotations (33 main binary annotations, MAF bins, LD-related annotations)

Methodological Steps:

- Variant Annotation: Annotate all variants in the summary statistics using the baseline-LF model, including functional categories (e.g., coding, UTR, conserved regions) and frequency bins.

- LD Reference Integration: Calculate LD scores for all variants using the UK10K reference panel to account for LD patterns specific to low-frequency variants.

- Heritability Partitioning: Jointly analyze all annotations using S-LDSC to estimate:

- ( h{lf}^2 ): Heritability explained by all low-frequency variants

- ( h{c}^2 ): Heritability explained by all common variants

- Enrichment Calculation: Compute Low-Frequency Variant Enrichment (LFVE) and Common Variant Enrichment (CVE) for each functional annotation:

- LFVE = (Proportion of ( h{lf}^2 ) in annotation) / (Proportion of low-frequency variants in annotation)

- CVE = (Proportion of ( h{c}^2 ) in annotation) / (Proportion of common variants in annotation)

- Statistical Comparison: Test for significant differences between LFVE and CVE using z-tests with multiple testing correction.

Interpretation: Significant differences between LFVE and CVE indicate annotations under differential selective pressure. For example, the substantially higher LFVE in non-synonymous coding variants reflects stronger negative selection on functional elements [16].

Figure 1: S-LDSC Workflow for Low-Frequency Variants. This workflow details the extended S-LDSC methodology for partitioning heritability across variant frequency categories and functional annotations.

Protocol 2: DeepRVAT for Rare Variant Association Testing

Purpose: To perform powerful rare variant association tests by integrating diverse functional annotations using deep set networks.

Input Data Requirements:

- Whole exome/genome sequencing data with genotype quality filters (INFO score >0.8 for imputed variants)

- 34 variant annotations (MAF, VEP consequences, missense impact scores, conservation, splicing, epigenetic predictions)

- Phenotypic data for seed gene identification

Methodological Steps:

- Seed Gene Identification: Conduct conventional rare variant association tests (burden/SKAT) to identify initial trait-associated genes for model training.

- Data Partitioning: Split data into k-folds (typically k=5) for cross-validation to prevent overfitting.

- Model Architecture Specification:

- Gene Impairment Module: Deep set network that aggregates variant annotations for each gene

- Phenotype Module: Linear models connecting gene impairment scores to traits

- Model Training: Optimize parameters end-to-end using cross-validation with multiple random initializations per fold.

- Association Testing: Apply the trained model to perform genome-wide rare variant association tests using the learned gene impairment scoring function.

- Statistical Calibration: Assess calibration using quantile-quantile plots and compute family-wise error rates (FWER) to control for multiple testing.

Validation: Evaluate replication rates in held-out datasets and compare discovery yield against alternative methods (STAAR, Monti et al.) [18].

Figure 2: DeepRVAT Analytical Framework. This framework illustrates the DeepRVAT workflow for integrating variant annotations using deep set networks to boost rare variant association testing power.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Variant Integration Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Panels | UK10K, Haplotype Reference Consortium, 1000 Genomes Project | Provide linkage disequilibrium information for imputation and heritability estimation | UK10K offers enhanced low-frequency variant coverage in European populations |

| Variant Annotation | VEP, ANNOVAR, CADD, PolyPhen-2, SIFT, AlphaMissense | Functional consequence prediction and variant prioritization | Integrates sequence ontology, conservation, and structural impact |

| Analysis Software | S-LDSC, DeepRVAT, STAAR, REGENIE, PLINK/SEQ | Statistical analysis of low-frequency and rare variants | S-LDSC partitions heritability; DeepRVAT integrates annotations via deep learning |

| Data Repositories | UK Biobank, gnomAD, dbGaP, EGA | Provide population frequency data and summary statistics | gnomAD aggregates exome/genome sequences from diverse populations |

| Visualization Tools | LocusZoom, GEMINI, GenomeBrowse | Visual interpretation of association results and variant context | Integrates association signals with genomic annotations |

Case Studies in Complex Disease Genetics

Liver Cirrhosis: Integrative Common and Rare Variant Analysis

A recent multi-ancestry genome-wide association study on liver cirrhosis demonstrated the power of integrating common and rare variant analyses. The study identified 14 validated risk associations for cirrhosis through a multi-phase approach [19]. Particularly informative was the endophenotype-driven analysis, which used liver enzyme GWAS associations (alanine aminotransferase and γ-glutamyl transferase) from up to 1 million individuals as priors to enhance genomic discovery for cirrhosis [19]. This approach identified 21 ALT-associated variants and 20 GGT-associated variants that were also associated with cirrhosis risk, with 11 reaching genome-wide significance in the primary cirrhosis meta-analysis [19].

Notably, the PNPLA3 p.Ile148Met variant demonstrated significant interactions with alcohol intake, obesity, and diabetes on cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma risk [19]. The study further illustrated how focusing on prioritized genes from common variant analyses can guide rare variant discovery—rare coding variants in GPAM were found to associate with lower ALT levels, supporting GPAM as a potential target for therapeutic inhibition [19].

Rheumatoid Arthritis: Protein-Coding Variants Across the Frequency Spectrum

An in-depth investigation of 25 biological candidate genes from RA GWAS loci revealed contributions from variants across the frequency spectrum [20]. Deep exon sequencing of 500 RA cases and 650 controls identified an accumulation of rare nonsynonymous variants exclusive to RA cases in IL2RA and IL2RB (burden test: p = 0.007 and p = 0.018, respectively) [20]. Subsequent large-scale genotyping in 10,609 RA cases and 35,605 controls demonstrated a strong enrichment of coding variants with nominal association signals (penrichment = 6.4×10−4) after adjusting for the best signal of association at each locus [20].

At the CD2 locus, fine-mapping revealed that a missense variant (rs699738) and a noncoding variant (rs624988) resided on distinct haplotypes and independently contributed to RA risk (p = 4.6×10−6) [20]. This finding highlights the allelic complexity underlying GWAS loci and the importance of comprehensive variant assessment across functional categories and frequency spectra.

Clinical and Therapeutic Applications

Risk Prediction and Stratification

Integrating low-frequency and rare variants into polygenic risk scores enhances their utility for clinical risk prediction. Empirical studies have demonstrated that PRS incorporating rare variants can better identify individuals at high genetic risk for various complex diseases [18]. For liver cirrhosis, a PRS developed from common and rare variant associations significantly predicted progression from cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma, illustrating the clinical potential for monitoring high-risk individuals [19].

Drug Target Identification and Validation

Rare variants with large effect sizes provide particularly valuable insights for drug development, as they often directly implicate specific genes and biological pathways. The discovery of rare coding variants in GPAM associated with lower ALT levels supported its investigation as a potential target for therapeutic inhibition in liver disease [19]. Similarly, genes implicated through rare variant associations in rheumatoid arthritis (e.g., IL2RA, IL2RB) represent promising targets for immunomodulatory therapies [20].

The growing availability of large-scale biobank data with whole exome/genome sequencing enables systematic evaluation of the therapeutic implications of rare variant associations across hundreds of complex traits, accelerating the identification and prioritization of novel drug targets.

Integrating low-frequency and rare variants into genetic architectural models is essential for comprehensively understanding the genetic underpinnings of complex phenotypes. Methodological advances in variant detection, imputation, and association testing have dramatically improved our ability to characterize the contribution of these variants to disease risk. The distinct functional enrichment patterns observed across the allele frequency spectrum reflect the varying selective pressures acting on genomic elements and provide important biological insights into disease mechanisms.

Future efforts in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) increasing diversity in genetic studies to capture population-specific rare variants; (2) developing more sophisticated integrative methods that simultaneously model common, low-frequency, and rare variants while accounting for their interactions; and (3) enhancing functional validation frameworks to accelerate the translation of genetic discoveries into biological insights and therapeutic opportunities. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and biobank resources expand, the integration of variants across the frequency spectrum will become increasingly central to complex disease genetics and personalized medicine.

The genetic architecture of complex phenotypes—the number, frequencies, and effect sizes of causal variants—is not a static biological property but rather a dynamic outcome of evolutionary processes. Negative selection (or purifying selection), which selectively removes deleterious genetic variation from populations, plays a fundamental role in shaping the relationships between three key genetic parameters: minor allele frequency (MAF), linkage disequilibrium (LD), and variant effect sizes. Understanding these relationships is crucial for elucidating disease biology, designing effective genetic association studies, and developing accurate polygenic risk scores for clinical application.

The central premise underlying this relationship is that variants with larger effects on fitness-related traits are subject to stronger negative selection, preventing them from rising to high population frequencies. This evolutionary pressure creates a stratified genetic architecture where causal variants are enriched in specific genomic regions and frequency spectra. This technical guide examines the quantitative evidence, methodological approaches, and practical implications of these relationships for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working within the context of complex phenotype research.

Core Conceptual Framework: The Interplay of Selection, Frequency, and Effect Size

Fundamental Evolutionary Principles

Negative selection acts pervasively on genetic variants associated with human complex traits. Genome-wide analyses of 28 complex traits in the UK Biobank (N = 126,752) have detected significant signatures of natural selection in 23 traits, including reproductive, cardiovascular, anthropometric traits, and educational attainment [21]. These signatures are consistent with a model of negative selection, as confirmed by forward simulations [21]. The mechanism operates through selective constraint: variants that negatively impact fitness (including health, reproduction, or survival) are preferentially kept at low frequencies or removed from the population over generational time.

This evolutionary process creates an inverse relationship between MAF and effect size through two primary mechanisms:

- Direct selection: Variants with large effects on fitness-related traits are removed more efficiently from the population.

- Pleiotropic selection: Variants affecting multiple traits may be selected against due to their effects on fitness-related phenotypes, even if their effect on the disease of interest is neutral.

The resulting genetic architecture demonstrates that lower-frequency SNPs have significantly larger per-allele effect sizes for most complex traits [22]. This frequency-dependent architecture can be quantified using mathematical models described in subsequent sections.

The Impact on Linkage Disequilibrium and Regional Architecture

Beyond MAF-effect size relationships, negative selection also shapes architecture through LD-dependent patterns. Genomic regions with low levels of LD (LLD) or low total LD (TLD) explain significantly more heritability than expected by chance [23]. This pattern occurs because negative selection creates a correlation between functional importance and recombination rates: regions under stronger functional constraint tend to have higher recombination rates, which breaks down LD over evolutionary time. Consequently, SNPs in low-LD regions are more likely to be causal and have larger effects, reflecting the action of negative selection on functionally important genomic regions [23].

Table 1: Key Parameters Shaped by Negative Selection

| Parameter | Relationship with Negative Selection | Interpretation | Primary Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Effect Size | Inversely correlated with MAF | Rare variants have larger per-allele effects | α = -0.38 across 25 UK Biobank traits [24] |

| Causal Probability | Higher in low-LD regions | Negative selection increases causal variant probability in high-recombination regions | LLD/TLD enrichment [23] |

| Population Specificity | Increased for variants under selection | Population-specific private variants contribute substantially to heritability | ~30% of heritability from European-specific variants [25] |

| Polygenicity | Varies with selection strength | Proportion of causal SNPs differs across traits under selection | ~6% of SNPs have nonzero effects on average [21] |

Quantitative Evidence and Empirical Findings

The α Parameter: Quantifying MAF-Effect Size Relationships

The relationship between MAF and effect sizes can be quantified using the α model, a random-effects model in which the per-allele trait effect β of a SNP depends on its MAF p via:

E[β²∣p] = σ²_g,α · [2p(1-p)]^α [22]

In this model, a negative value of α implies that lower-frequency SNPs have larger per-allele effect sizes, whereas α = 0 implies no MAF dependence. The parameter σ²_g,α represents the component of SNP effect variance independent of frequency.

Application of this model to 25 UK Biobank diseases and complex traits (N = 113,851 individuals) revealed that all traits produced negative α estimates, with a best-fit mean of α = -0.38 (s.e. 0.02) across traits [24]. This provides robust, quantitative evidence that rare variants have significantly increased per-allele effect sizes for most traits, with statistically significant heterogeneity across traits (P = 0.0014) [22], consistent with different levels of direct and/or pleiotropic negative selection.

Table 2: α Estimates and Heritability Explanations Across MAF Spectra for Selected Traits

| Trait Category | Mean α Estimate | % Heritability from MAF < 1% | Implication for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric | -0.41 | 3-7% | Moderate negative selection |

| Reproductive | -0.52 | 5-12% | Strong negative selection |

| Cardiovascular | -0.35 | 2-5% | Moderate negative selection |

| Educational | -0.45 | 6-10% | Strong negative selection |

| Metabolic | -0.32 | 2-4% | Moderate negative selection |

Despite larger effect sizes for rare variants, rare variants (MAF < 1%) typically explain less than 10% of total SNP-heritability for most traits analyzed [22] [24]. This indicates that while negative selection increases per-allele effect sizes at rare variants, their overall contribution to heritability remains limited due to their low frequencies in the population.

Population-Specific Genetic Architectures

Negative selection, combined with human demographic history, results in population-specific genetic architectures that directly impact the portability of genetic findings. Analysis of 37 traits and diseases in the UK Biobank revealed that approximately 30% of heritability comes from European-specific variants [25] [26]. This population-specificity arises because:

- Recent explosive population growth has created an excess of new variants that tend to be low frequency and population-specific (private variation)

- Negative selection acts differently on these private variants across populations with distinct demographic histories

- For traits where alleles with the largest effects are under the strongest negative selection, approximately half of the heritability can be accounted for by variants in Europe that are absent from Africa [27]

This architecture directly reduces the accuracy of polygenic scores when applied between populations, creating challenges for equitable implementation of genetic risk prediction across diverse populations [25] [26].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Estimating MAF-Dependent Architectures

Profile Likelihood-Based Mixed Model Method [22] [24]

This method estimates MAF-dependent architectures from genotype and phenotype data using a linear mixed model framework:

- Model Specification: The model likelihood depends on α, σ²_g,α, and environmental variance, with LD-dependent SNP weights incorporated to avoid biases due to LD-dependent architectures.

- Profile Likelihood Computation: Compute the profile likelihood over values of α by maximizing the likelihood with respect to σ²_g,α and environmental variance for a given α.

- Parameter Estimation: The estimate ^α is defined as the mode of the profile likelihood curve, with the curve width used to compute error estimates.

- Heritability Estimation: Use corresponding values of ^σ²g,α to estimate SNP-heritability h²g while accounting for MAF-dependent SNP effects.

The method has been validated through simulations based on imputed UK Biobank genotypes, demonstrating that it provides unbiased estimates of α when LD is correctly modeled, with minimal bias from imputation noise [22].

Extended Gaussian Mixture Model for Effect Size Distributions

An extended Gaussian mixture model incorporates both MAF and LD dependence for the distribution of causal effects [23]:

β(H) ∼ π₁{(1-pc)N(0, σ²b) + pcN(0, σ²cH^S)}

Where:

- π₁ is the polygenicity (proportion of causal SNPs)

- H is the SNP's heterozygosity (H = 2p(1-p))

- S is a selection parameter (negative values indicate larger effects for rarer variants)

- p_c is the prior probability that a SNP's causal component comes from the selection-dependent Gaussian

This model captures how causal effects are distributed with dependence on both total LD and heterozygosity, whereby SNPs with lower total LD and H are more likely to be causal with larger effects—consistent with the influence of negative selection pressure [23].

Stratified Trans-Ethnic Genetic Correlation (S-LDXR)

The S-LDXR method estimates enrichment of stratified squared trans-ethnic genetic correlation across functional categories of SNPs [28]:

Foundation: The product of Z-scores of SNP j in two populations has expectation: E[Z₁jZ₂j] = √(N₁N₂) · ΣC ℓ×(j,C)θC where ℓ×(j,C) is the trans-ethnic LD score of SNP j with respect to annotation C.

Regression: Estimate θ_C for each annotation C using weighted least squares regression.

Stratified Correlation: Estimate squared trans-ethnic genetic correlation for annotation C as: r²g(C) = ρ²g(C) / (h²g₁(C)h²g₂(C))

This approach has revealed that squared trans-ethnic genetic correlation is significantly depleted (0.82×, s.e. 0.01) in the top quintile of background selection statistic, implying more population-specific causal effect sizes in regions impacted by selection [28].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Negative Selection

| Resource | Function/Application | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank Data | Large-scale genotype & phenotype data | 113,851 British-ancestry individuals; 11M SNPs; 25 complex traits | [22] |

| α Model Software | Estimate MAF-dependent architectures | Profile likelihood-based mixed model; LD correction | [24] |

| S-LDXR Method | Stratified trans-ethnic genetic correlation | Estimates population-specific effect sizes across annotations | [28] |

| baseline-LD-X Model | Genomic annotations for stratified analysis | 62 functional annotations defined in EAS and EUR populations | [28] |

| Forward Simulation Tools (SLiM) | Evolutionary modeling of traits | Simulates demographic history + selection; validates models | [25] |

| gnomAD Database | Constraint metric calculation | 141,456 individuals; pLoF variants; gene-level constraint | [29] |

Implications for Drug Development and Clinical Translation

Target Validation and Safety Assessment

The relationship between negative selection and genetic architecture has profound implications for drug target validation. Analysis of loss-of-function (LoF) variation in human populations provides crucial insights for target safety assessment:

- Constraint metrics (obs/exp ratios) quantify how strongly purifying selection has removed pLoF variants from populations, with lower values indicating stronger selection [29].

- Essential genes can be successful drug targets: 19% of drug targets have lower obs/exp values than the average for genes known to cause severe haploinsufficiency diseases, including HMGCR (statin target) and PTGS2 (aspirin target) [29].

- Human knockout identification remains challenging for most genes, with median expected two-hit frequency of just six per billion in outbred populations, necessitating focused recruitment in consanguineous populations [29].

Polygenic Risk Prediction Across Populations

Population-specific genetic architectures resulting from negative selection directly impact the utility of polygenic scores:

- Transferability reduction: Approximately 30% of heritability derives from population-specific variants, creating inherent limitations in cross-population prediction accuracy [25].

- Extreme risk identification: Individuals in the tails of the genetic risk distribution may not be identified via polygenic scores generated in another population [26].

- Study design implications: Genetic association studies need to include more diverse populations to enable equitable utility of phenotype prediction in all populations [25] [27].

Negative selection operates as a fundamental evolutionary force that shapes the genetic architecture of human complex phenotypes by creating structured relationships between MAF, LD, and effect sizes. The empirical evidence—from α estimates of approximately -0.38 across traits to the enrichment of heritability in low-LD regions—consistently supports this model. These relationships have profound implications for study design, analytical method development, drug target validation, and the equitable implementation of genetic risk prediction across diverse populations. Future research expanding into more diverse populations, integrating molecular phenotypes, and developing methods that jointly model evolutionary and architectural parameters will further enhance our understanding of how natural selection has sculpted the genetic landscape of human complex traits.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified thousands of genetic loci associated with complex phenotypes, yet the functional interpretation of these associations remains a central challenge in human genetics. The vast majority of trait-associated variants reside in non-coding regions of the genome, complicating the direct translation of statistical associations into biological mechanisms [30]. These non-coding variants are enriched in regulatory elements such as enhancers and promoters, suggesting they exert their effects by modulating gene expression rather than altering protein structure [31] [32]. The interpretation of non-coding variants is further complicated by linkage disequilibrium (LD), which results in true causal variants being found among numerous statistically correlated variants [30]. This review provides a comprehensive technical framework for progressing from statistical associations to biological mechanisms, with particular emphasis on functional annotation, experimental validation, and therapeutic translation within the context of complex phenotype research.

Computational Annotation and Prioritization of Non-Coding Variants

The initial step in interpreting non-coding variants involves comprehensive functional annotation using computational tools and databases that integrate diverse genomic information. This process aims to prioritize variants for further experimental validation based on their potential functional impact.

Annotation Databases and Platforms

Several specialized databases have been developed to support the interpretation of non-coding variants by aggregating functional genomic data from multiple sources. These resources provide crucial information for assessing the potential regulatory role of non-coding SNPs.

Table 1: Comprehensive Databases for Non-Coding Variant Annotation

| Database | Key Features | Data Sources | Specialized Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCAD | 665 million variants; 12 population frequencies; regulatory elements; interaction details [32] | 96 integrated sources | Clinical diagnosis support; Chinese population data (20,964 individuals) |

| FUMA | Functional mapping; gene prioritization; cell-type specificity prediction [33] | Multiple public repositories | GWAS prioritization; cell-type enrichment analysis |

| GREEN-DB | 2.4 million regulatory elements; tissue-specific annotations; prediction scores [32] | Epigenomic datasets | Regulatory potential ranking; disease gene mapping |

| SNPnexus | Five annotation systems; regulatory element overlaps; structural variations [34] | RefSeq, Ensembl, VEGA, UCSC, AceView | Alternative splicing impact assessment |

| 3DSNP | Non-coding SNPs linked to 3D interacting genes [35] | Chromatin interaction data | Connecting distal regulators to target genes |

These platforms address the critical challenge of data dispersion by integrating population frequency data, functional prediction scores, regulatory element annotations, and chromatin interaction information into unified resources [32]. For instance, the NCAD database specifically focuses on supporting clinical genetic diagnosis by incorporating allele frequency information from 12 diverse populations, with particular emphasis on Chinese genomic data [32]. This comprehensive approach enables researchers to overcome the time-consuming process of searching dispersed datasets and enhances the efficiency of variant prioritization.

Regulatory Element Annotation

Non-coding variants can influence gene regulation through multiple mechanisms, necessitating annotation across different categories of regulatory elements:

Enhancer and Promoter Elements: Variants in these regions can alter transcription factor binding sites or chromatin accessibility, potentially affecting the expression of distal genes through chromatin looping [31] [30]. The BRAIN-MAGNET atlas, for example, functionally characterized 148,198 regulatory regions in neural stem cells, identifying primed non-coding regulatory elements already present in embryonic stem cells [36].

Non-Coding RNAs: Annotation of variants overlapping with microRNAs, long non-coding RNAs, and other non-coding RNA categories provides insights into post-transcriptional regulation and RNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms [32].

Chromatin State and Epigenomic Marks: Integrating data from assays such as H3K27ac ChIP-seq (marking active enhancers) and ATAC-seq (assessing open chromatin) helps identify variants in potentially functional regulatory regions [31]. For central obesity research, this approach successfully prioritized 2,034 SNPs falling within adipocyte enhancer or open chromatin regions for further functional testing [31].

Functional Validation of Non-Coding Variants

Following computational prioritization, experimental validation is essential to confirm the regulatory potential of non-coding variants and elucidate their mechanisms of action.

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs), including Self-Transcribing Active Regulatory Region Sequencing (STARR-seq), enable high-throughput functional characterization of thousands of non-coding variants in a single experiment [31]. These techniques directly test the enhancer activity of DNA sequences by cloning them into reporter constructs and measuring their transcriptional output through high-throughput sequencing.

STARR-seq Protocol for Enhancer Validation:

Library Design: Two primary strategies exist for STARR-seq library construction. Short fragments (≤230 bp) obtained from oligonucleotide synthesis are optimal for fine-mapping enhancer effects of individual variants, while longer fragments (≥500 bp) sourced from sheared whole-genome DNA are better suited for genome-wide screens or enhancer discovery [31]. For allelic enhancer activity assessment of prioritized SNPs, the short fragment strategy (120-bp DNA sequence plus 30-bp adaptor) is recommended as it directly generates fragments containing both reference and alternative alleles.

Vector Construction: Candidate sequences are cloned into a specialized plasmid vector downstream of a minimal promoter, upstream of a reporter gene, and positioned such that active enhancers transcribe themselves [31].

Cell Transfection: The library is transfected into relevant cell types (e.g., adipocytes for obesity research, neural cells for neurological traits) using appropriate methods (electroporation, lipofection) to ensure sufficient representation [31].

Sequencing and Analysis: RNA is harvested and converted to cDNA, and the relative abundance of each sequence in the RNA pool versus the input DNA library is quantified by high-throughput sequencing. Significantly enriched sequences represent active enhancers, while allelic imbalances indicate variant effects on enhancer activity.

In a study of central obesity, STARR-seq analysis of 2,034 prioritized SNPs identified 141 variants with allelic enhancer activity, revealing their potential roles in adipogenesis and fat distribution [31]. Subsequent transcription factor enrichment analysis further prioritized 20 key TFs mediating central-obesity-relevant genetic regulatory networks [31].

Integrating 3D Genome Architecture

Understanding the mechanism by which non-coding variants influence gene expression requires mapping their physical interactions with target gene promoters. Chromatin conformation capture techniques, particularly Hi-C, provide insights into the three-dimensional organization of the genome, enabling the identification of long-range regulatory interactions [30].

Hi-C Methodology for Mapping Chromatin Interactions:

- Crosslinking: Cells are treated with formaldehyde to crosslink protein-DNA and protein-protein complexes, preserving the three-dimensional chromatin architecture.

- Digestion and Labeling: Chromatin is digested with a restriction enzyme, and resulting fragment ends are labeled with biotin.

- Ligation and Purification: Crosslinked fragments are ligated under dilute conditions that favor intramolecular ligation, then purified and sheared.

- Pull-down and Sequencing: Biotin-containing fragments are pulled down with streptavidin beads and prepared for high-throughput sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Sequencing reads are mapped to the genome, and interaction frequencies between genomic loci are quantified to identify statistically significant interactions.

Integration of Hi-C data with GWAS signals enables researchers to connect non-coding variants with their potential target genes, even over megabase-scale distances. This approach was instrumental in elucidating how a BMI-associated signal within an intronic region of FTO regulates the expression of IRX3 and IRX5 through long-range enhancer-promoter interactions [31].

From Associations to Biological Mechanisms

Translating statistically associated non-coding variants into actionable biological insights requires integrating multiple lines of evidence across functional genomics, transcriptomics, and disease biology.

Gene Prioritization and Validation

Establishing causal relationships between non-coding variants and their target genes is essential for understanding disease mechanisms. Several complementary approaches facilitate this process:

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL) Mapping: Identifying associations between genetic variants and gene expression levels provides direct evidence for regulatory effects. Colocalization analysis between GWAS signals and eQTL signals strengthens confidence in shared causal variants [31].

Functional Perturbation Studies: CRISPR-based genome editing techniques enable direct manipulation of candidate regulatory elements to assess their impact on gene expression and cellular phenotypes. For example, in the central obesity study, functional experiments validated the molecular mechanism of rs8079062 in regulating RNF157 expression and demonstrated RNF157's role in adipogenic differentiation [31].

Mendelian Randomization with pQTL: Integration with protein quantitative trait locus (pQTL) data from large cohorts (e.g., Iceland cohort, n = 35,559) helps evaluate the potential of candidate genes to serve as therapeutic targets for complex traits [31].

Artificial Intelligence Approaches

Machine learning methods, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are increasingly employed to predict regulatory activity from DNA sequence composition and prioritize functional non-coding variants [36]. The BRAIN-MAGNET framework represents a functionally validated CNN that identifies nucleotides required for non-coding regulatory element function, enabling fine-mapping of GWAS loci for common neurological traits and prioritizing candidate disease-causing rare non-coding variants in neurogenetic disorders [36]. These AI approaches leverage the growing availability of functional genomics data to develop predictive models that can interpret the regulatory code of the human genome.

Population-Specific Considerations in Non-Coding Variant Interpretation

The transferability of genetic findings across diverse populations remains a significant challenge in genomics. Polygenic risk scores (PRS) developed in European populations often show reduced performance in non-European populations, partly due to differences in allele frequencies and LD patterns in non-coding regions [14].

Recent methodological advances aim to address these limitations by explicitly modeling local ancestry and cross-ancestry genetic architecture. The SDPR_admix method characterizes the joint distribution of effect sizes across ancestries, considering whether they are both zero, ancestry-enriched, or shared with correlation [14]. This approach has demonstrated improved prediction accuracy for real traits in European-African admixed individuals in the UK Biobank when trained on the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) dataset (N = 13,000) [14]. Furthermore, deployment on the All of Us dataset (N = 52,000) increased prediction accuracy approximately 5-fold compared with training on PAGE alone, highlighting the importance of diverse reference populations for accurate genetic prediction [14].

Table 2: Analytical Tools for Non-Coding Variant Interpretation

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Key Applications | Technical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDPR_admix | PRS calculation for admixed individuals [14] | Cross-ancestry genetic prediction | Models joint distribution of effect sizes across ancestries |

| BRAIN-MAGNET | Predicts NCRE activity from DNA sequence [36] | Neurological disorder variant prioritization | Convolutional neural network |

| Genomic SEM | Multivariate GWAS analysis of latent factors [7] | Cognitive ability genetic architecture | Structural equation modeling with GWAS data |

| FINEMAP | Bayesian fine-mapping of causal variants [31] | Identifying probable causal SNPs | Bayesian approach with LD reference |

| PLINK | Whole genome association analysis [37] | Quality control; basic association testing | Toolset for large-scale genotype analysis |

Successful interpretation of non-coding variants requires specialized computational tools, experimental reagents, and data resources. The following table summarizes key solutions for conducting comprehensive functional analyses.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Non-Coding Variant Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Solution | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Annotation | NCAD Database [32] | Comprehensive non-coding variant annotation with population frequencies |

| Reporter Assays | STARR-seq [31] | High-throughput enhancer activity screening |

| Chromatin Interaction | Hi-C [30] | Mapping 3D genome architecture and enhancer-promoter interactions |

| Variant Effect Prediction | BRAIN-MAGNET [36] | AI-based prediction of non-coding regulatory element activity |

| Population Genetics | SDPR_admix [14] | Polygenic risk scoring in admixed populations |

| Statistical Fine-mapping | FINEMAP [31] | Bayesian identification of causal variants in LD regions |

| Multi-trait Integration | Genomic SEM [7] | Multivariate analysis of shared genetic architecture |

| Data Integration | FUMA [33] | Functional mapping and annotation of GWAS results |

The systematic interpretation of non-coding variants represents a critical frontier in understanding the genetic architecture of complex phenotypes. This process requires an integrated approach combining computational annotation, functional validation through high-throughput assays, and careful consideration of population-specific genetic architectures. The development of specialized databases like NCAD, experimental methods such as STARR-seq, and analytical frameworks including BRAIN-MAGNET and SDPR_admix provide powerful tools for translating statistical associations into biological insights. As these resources and methodologies continue to mature, they promise to unravel the regulatory code of the human genome, enabling the identification of novel therapeutic targets and advancing personalized medicine approaches for complex diseases.

From Data to Drugs: Analytical Frameworks and Translational Applications in Genetics