Decoding Cellular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide to Temporal Modeling in Single-Cell Transcriptomics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of temporal modeling in single-cell transcriptomics, a key technology for understanding dynamic biological processes like development, disease progression, and...

Decoding Cellular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide to Temporal Modeling in Single-Cell Transcriptomics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of temporal modeling in single-cell transcriptomics, a key technology for understanding dynamic biological processes like development, disease progression, and drug response. We explore the foundational concepts that move beyond static snapshots to capture cellular trajectories, review cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies for dynamic inference, and address critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges unique to time-series data. A dedicated section on validation and comparative analysis equips researchers with strategies to benchmark model performance and assess biological relevance. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to empower robust temporal analysis and its translation into biomedical insights.

From Snapshots to Movies: Unveiling the Why and How of Temporal scRNA-seq

The Critical Limitation of Snapshot Data and the Need for a Dynamic View

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biology by enabling high-throughput quantification of gene expression at individual cell resolution, revealing unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity [1] [2]. However, standard scRNA-seq methods provide only static cellular snapshots, as cells are destroyed during sequencing, obscuring the dynamic processes that unfold temporally [3] [4]. This fundamental limitation poses significant challenges for interpreting dynamic biological processes such as differentiation, reprogramming, and disease progression, where understanding the transition of a cell from one state to another is central to the biological question [4].

In many biological systems, the dynamic changes represent a continuum of highly variable states rather than discrete, stable entities [5]. When cells are isolated from their local environment and destroyed prior to profiling, these "snapshots" lose crucial contextual information regarding both a cell's spatial environment and its position within a trajectory of dynamic behavior [5]. The resulting data presents researchers with a fundamental challenge: how to reconstruct dynamic processes from static observations that represent individual moments frozen in time.

The Computational Frontier: Inferring Dynamics from Static Snapshots

Pseudotime Reconstruction: Ordering Cellular Transitions

To overcome the limitations of snapshot data, computational biologists have developed pseudotime reconstruction methods that attempt to order cells along differentiation trajectories based on the assumption that developmentally related cells share similarities in gene expression [1] [4]. These methods, including Monocle 3, TSCAN, and Slingshot, assume that cells are replicas of each other and that the 'time' when they are in a biological process is the only variable [1] [4]. The observed distribution of the population is thus treated as representing the states of a single cell along a dynamic process.

The fundamental principle underlying pseudotime analysis is that transcriptome similarity can be used as a proxy for developmental proximity [4]. Each method employs different mathematical approaches—Monocle 3 uses reversed graph embedding, TSCAN utilizes minimum spanning trees, and Slingshot employs smooth curves known as principal curves—but they all share the core assumption that continuous transitions exist between cell states and that these transitions can be reconstructed from population snapshots [1]. While powerful, these approaches represent statistical expectations rather than direct measurements of temporal processes [4].

RNA Velocity: Leveraging Splicing Kinetics

A groundbreaking advancement in dynamic inference came with the introduction of RNA velocity in 2018, which leveraged unspliced pre-mRNA and spliced mRNA information to model instantaneous gene expression change rates and predict future transcriptional states over hour-long timescales [3]. This approach utilizes the ratio of unspliced to spliced mRNA as an indicator of the immediate future state of a cell, effectively adding a directional component to snapshot data [3] [4].

The method has evolved through second-generation computational tools including scVelo, dynamo, and CellRank, which generalize the framework to handle more complex biological scenarios [3]. These tools can reveal novel disease mechanisms in conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, and chronic inflammation by analyzing immune cell differentiation and state transitions [3]. The integration of RNA velocity with spatial and multimodal data represents the current frontier of this approach, further enhancing its predictive power [3].

Optimal Transport: Connecting Unpaired Time Points

Optimal transport (OT) theory has emerged as a powerful mathematical framework for reconstructing dynamic trajectories from multiple unpaired scRNA-seq snapshots [6]. Methods like TIGON (Trajectory Inference with Growth via Optimal transport and Neural network) implement dynamic, unbalanced OT models based on Wasserstein-Fisher-Rao (WFR) distance to simultaneously capture the velocity of gene expression for each cell and the change in cell population over time [6].

TIGON addresses a critical limitation of earlier methods by incorporating both transport and growth terms, recognizing that cell populations may change over time due to cell division and death [6]. The method utilizes a dimensionless formulation based on WFR distance that is solved by neural ordinary differential equations, enabling the reconstruction of dynamic trajectories and population growth simultaneously, along with the underlying gene regulatory network from multiple snapshots [6].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Dynamic Inference Methods

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Key Principle | Temporal Resolution | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudotime Reconstruction | Monocle 3, TSCAN, Slingshot | Orders cells by transcriptome similarity | Relative ordering without real-time scale | Assumes continuous transitions; sensitive to population structure |

| RNA Velocity | Velocyto, scVelo, dynamo | Leverages unspliced/spliced mRNA ratio | Short-term (hours) predictions | Depends on accurate kinetic parameter estimation |

| Optimal Transport | TIGON, Waddington-OT, TrajectoryNet | Matches cell distributions across time points | Multiple measured time points | Computationally intensive; requires multiple snapshots |

| Temporal Pattern Detection | TDEseq | Identifies expression patterns across multiple time points | Requires multi-timepoint design | Limited to predefined expression patterns |

Experimental Protocols for Dynamic Modeling

Protocol: Temporal Gene Expression Pattern Detection with TDEseq

TDEseq is a non-parametric statistical method designed to detect temporal gene expression patterns from multi-sample multi-stage single-cell transcriptomics data [7]. The protocol consists of the following steps:

Data Preprocessing: Normalize raw count data using log-normalization and account for confounding variables (e.g., cell cycle effects, batch effects) [7].

Basis Function Specification: Select appropriate smoothing spline basis functions—I-splines for monotone patterns (growth, recession) or C-splines for quadratic patterns (peak, trough) [7].

Model Fitting: Implement the linear additive mixed model (LAMM) framework with random effects to account for correlated cells within individuals: (y{gji}(t) = \boldsymbol{w}^{\prime}{gji}{\boldsymbol\alpha}g + \sum{k=1}^K sk(t)\beta{gk} + u{gji} + e{gji}) where (y_{gji}(t)) represents the log-normalized gene expression level for gene (g), individual (j) and cell (i) at time point (t) [7].

Hypothesis Testing: Test the null hypothesis (H0: \boldsymbol{\beta}g = 0) using a cone programming projection algorithm to handle nonnegative constraints, with p-values computed using test statistics that follow a mixture of beta distributions [7].

Pattern Classification: Combine p-values for the four patterns (growth, recession, peak, trough) through the Cauchy combination method to identify significant temporal expression genes [7].

Protocol: Dynamic Trajectory Reconstruction with TIGON

TIGON reconstructs growth and dynamic trajectories from single-cell transcriptomics data through the following methodology [6]:

Density Estimation: Convert time-series scRNA-seq data into density functions at discrete time points using a Gaussian mixture model: (\rhoi = \rho(x,ti), i = 1, 2, \cdots, T) [6].

Dimension Reduction: Project high-dimensional gene expression data onto a low-dimensional space using reversible and differentiable methods (PCA or AE) to enable efficient computation [6].

Neural Network Approximation: Approximate velocity (v(x,t)) and growth (g(x,t)) using two separate neural networks: (v(x,t) \approx NN1(x,t)) and (g(x,t) \approx NN2(x,t)) [6].

Dynamic Optimization: Solve the hyperbolic partial differential equation using unbalanced optimal transport by optimizing the WFR cost: ({\partial t}\rho (x,t) + \nabla \cdot (\mathbf{v}(x,t)\rho (x,t)) = g(x,t)\rho (x,t)) with the objective function: ({W{0,T}} = T\int\limits0^T {\int\limits{{\mathbb{R}^d}} {({{|\mathbf{v}(x,t)|}^2} + \alpha {{|g(x,t)|}^2})} } \rho (x,t)\mathrm{d}x\;\mathrm{d}t) [6].

Trajectory and GRN Inference: Track cell dynamics by integrating along the velocity field and construct temporal gene regulatory networks from the Jacobian of velocity (J = \left{ \frac{\partial \mathbf{v}i}{\partial xj} \right}_{i,j=1}^d) to identify regulatory relationships [6].

Visualizing Dynamic Relationships in Single-Cell Data

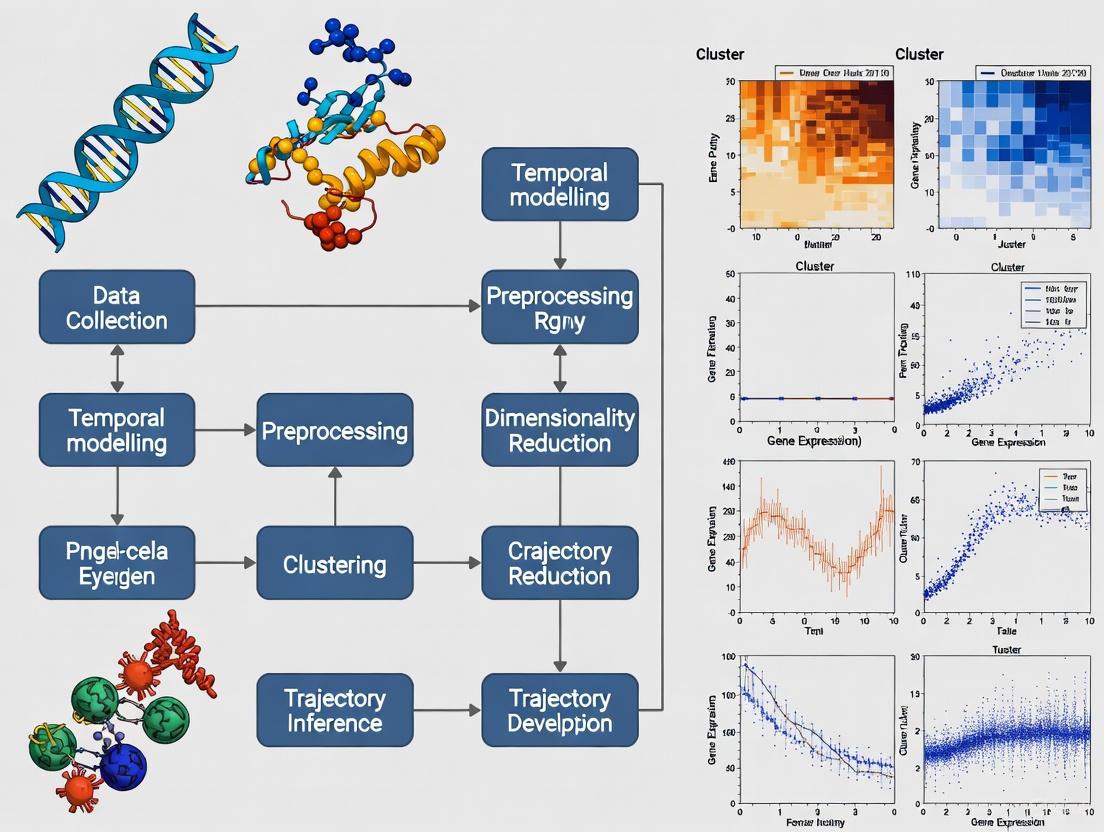

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework and workflow for reconstructing cellular dynamics from snapshot data:

The diagram above illustrates how different computational approaches extract temporal information from static snapshots to reconstruct dynamic trajectories, ultimately leading to insights into biological mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Dynamic Single-Cell Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Platforms (10X Genomics, Smart-seq2) | Experimental Platform | High-throughput gene expression profiling at single-cell resolution | Generating input snapshot data for all dynamic inference methods |

| RNA Metabolic Labeling (SLAM-seq, scNT-seq) | Experimental Method | Tags newly synthesized RNA for direct measurement of transcription kinetics | Ground truth for RNA velocity parameter estimation; studying transcriptional bursts |

| Lineage Tracing (CRISPR-based recording) | Experimental Method | Records ancestral relationships between cells using DNA barcodes | Constraining trajectory inference with clonal relationship information |

| Spatial Transcriptomics (MERFISH, seqFISH) | Experimental Method | Preserves spatial context during transcriptome profiling | Integrating spatial organization with temporal dynamics |

| TDEseq | Computational Tool | Detects temporal expression patterns using spline-based mixed models | Identifying genes with specific dynamic patterns across multiple time points |

| TIGON | Computational Tool | Reconstructs trajectories with growth using unbalanced optimal transport | Modeling developmental processes with cell population changes |

| scVelo | Computational Tool | Infers RNA velocity using dynamical modeling | Predicting short-term future cell states from splicing kinetics |

| CellRank | Computational Tool | Models state transitions using RNA velocity and graph neural networks | Identifying transition probabilities between cell states |

Future Perspectives: Toward a Truly Dynamic Single-Cell Biology

The field of temporal modeling in single-cell transcriptomics is rapidly evolving, with several emerging directions poised to address current limitations. Live-cell transcriptomics methods, such as Live-seq, enable transcriptomic profiling without cell destruction, providing an assumption-free measurement of dynamics [4]. This approach utilizes fluidic force microscopy (FluidFM) to extract cytoplasmic biopsies while preserving cell viability, allowing direct longitudinal monitoring of the same cells over time [4].

The integration of multimodal measurements—combining transcriptomics with epigenomics, proteomics, and spatial information—represents another promising frontier [2]. As the scale of single-cell datasets continues to grow, with experiments now profiling millions of cells, new computational approaches must address challenges in scaling to higher dimensionalities while quantifying uncertainty of measurements and analysis results [2]. Future methods will likely combine the strengths of computational inference with direct temporal measurements through innovative experimental designs, ultimately providing a more complete understanding of cellular dynamics in development, disease, and therapeutic interventions.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances offer the potential to move beyond descriptive cellular taxonomies to predictive models of cell fate decisions, enabling more targeted therapeutic interventions that account for the dynamic nature of cellular responses in complex biological systems.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biology by enabling high-throughput quantification of gene expression at individual cell resolution, allowing researchers to investigate cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution. However, a fundamental challenge persists: standard scRNA-seq provides only static cellular snapshots of gene expression, obscuring dynamic temporal processes such as differentiation, reprogramming, and disease progression [8] [3]. During development and homeostasis, cells undergo continuous transitions, adapting their transcriptional programs to coordinate behavior. To reconstruct these dynamic processes from static snapshots, computational biologists have developed three principal classes of temporal inference methods: pseudotime analysis, RNA velocity, and trajectory inference [8] [9].

These methods computationally order cells along developmental trajectories, allowing the unbiased study of cellular dynamic processes. The overarching goal is to map the developmental or disease history of differentiated cells, a fundamental objective in developmental and stem cell biology with significant impacts for regenerative medicine and cancer biology [8]. Since 2014, more than 70 trajectory inference tools have been developed, creating both opportunities and challenges for researchers seeking to apply these methods [10] [11]. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the core concepts, methodological comparisons, experimental protocols, and recent advances in pseudotime analysis, RNA velocity, and cell trajectory inference, framed within the broader context of temporal modelling in single-cell transcriptomics research.

Core Concepts and Methodological Foundations

Pseudotime Analysis

Pseudotime analysis refers to computational approaches that order individual cells along a hypothetical temporal trajectory based on their transcriptional similarities [8] [12]. The fundamental assumption is that cells with similar gene expression profiles are likely at similar stages of a developmental process. Pseudotime algorithms take a collection of cell states represented in a high-dimensional space and identify a one-dimensional, latent representation of cellular states that corresponds to developmental progression [8].

The technical workflow typically begins with a researcher defining a starting cell population (e.g., progenitor or stem cells) based on prior knowledge of the experimental system [8]. The algorithm then orders the cell state manifold by calculating the transcriptional distance of each cell from this starting point, assigning a pseudotime value to each cell representing its relative progression along the trajectory [8]. Mathematically, pseudotime is defined as the distance along a smooth continuous curve that passes through the cell state manifold, representing the most likely trajectory of cell transitions [8].

A key limitation of pseudotime approaches is their dependence on prior knowledge for setting the starting point, which can introduce bias if this knowledge is inaccurate or incomplete [8]. Additionally, these methods assume that transcriptional similarity directly implies developmental relationships, which may not always hold true [8]. For example, in early mammalian development, primitive and definitive endoderm have similar expression profiles but emerge from different precursors at different developmental stages [8].

RNA Velocity

RNA velocity is a groundbreaking computational method that predicts the future transcriptional state of individual cells by leveraging the ratio of unspliced (pre-mRNA) to spliced (mature mRNA) transcripts [8] [3]. The method is based on the fundamental observation that the timescale of cellular development is comparable to the kinetics of the mRNA life cycle: transcription of precursor mRNA, splicing to produce mature mRNA, followed by mRNA degradation [8].

The core principle states that if the ratio of unspliced to spliced mRNA is in balance, this indicates homeostasis (steady state), while an imbalance indicates future induction or repression in gene expression [8]. By comparing these ratios for each gene across cells, RNA velocity can infer both the direction and speed of gene expression changes along developmental trajectories [8]. This allows researchers to predict differentiation potential, identify fate decisions, and discover key regulators of cell transitions [8].

RNA velocity adds a temporal dimension to single-cell transcriptomics and can improve the accuracy and resolution of trajectory inference. The velocity vectors obtained for each cell can be projected into low-dimensional embeddings (e.g., UMAP or t-SNE) to visualize the directional flow of cells [8]. However, the method relies on several assumptions, including constant, gene-specific splicing rates that may not hold true in all biological contexts, and requires substantial cell numbers and sequencing depth for reliable estimates [8].

Trajectory Inference Methods

Trajectory inference approaches represent a broader class of methods that analyze genome-wide omics data from thousands of single cells to computationally infer the order of these cells along developmental trajectories [10]. These methods aim to reconstruct the underlying cellular dynamics from static snapshots, essentially connecting discrete cell states into continuous processes [9].

The initial methodological development focused on adapting approaches based on clustering or graph traversal, but recent advances have extended the field in multiple directions [9]. Current methods include probabilistic approaches that report uncertainties about their outputs, and methods that incorporate complementary knowledge such as unspliced mRNA, time point information, or other omics data to construct more accurate trajectories [9]. The trajectory models can take various topologies including linear, bifurcating, multifurcating, cyclic, or tree-like structures, reflecting the complexity of biological processes [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Temporal Inference Approaches

| Method Type | Core Data Input | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudotime Analysis | Spliced mRNA counts | Transcriptional similarity from a defined start point | Intuitive ordering; Multiple algorithms available | Requires prior knowledge for start point; Assumes transcriptional similarity reflects developmental relationship |

| RNA Velocity | Both unspliced and spliced mRNA counts | mRNA splicing kinetics | Predicts future states; Does not require start point | Assumes constant splicing rates; Requires high sequencing depth |

| Trajectory Inference | Typically spliced mRNA counts | Graph traversal or probabilistic modeling | Can capture complex topologies; Comprehensive benchmarking available | Model misspecification; Varying performance across topology types |

Comparative Performance and Benchmarking

As the number of trajectory inference methods has grown exponentially, comprehensive benchmarking studies have become essential for guiding methodological selection. A landmark 2019 study in Nature Biotechnology evaluated 45 trajectory inference methods on 110 real and 229 synthetic datasets, assessing performance across multiple metrics including cellular ordering accuracy, network topology correctness, scalability, and usability [10].

The results highlighted the complementarity of existing tools, demonstrating that method performance depends significantly on dataset dimensions and trajectory topology [10]. Some methods, including Slingshot, TSCAN, and Monocle DDRTree, consistently outperformed others in specific trajectory types [10] [12]. The benchmarking analysis indicated that while current methods perform well on simple trajectories, there remains considerable room for improvement, particularly for detecting complex trajectory topologies [10] [12].

This benchmarking effort led to the development of practical guidelines to help researchers select appropriate methods for their specific datasets, available through the dynverse platform [10]. The evaluation pipeline and data remain freely available, supporting continued development of improved tools designed to analyze increasingly large and complex single-cell datasets [10].

Table 2: Performance of Selected Trajectory Inference Methods Across Different Topologies

| Method Name | Linear Trajectories | Bifurcating Trajectories | Multifurcating Trajectories | Cyclic Trajectories | Tree-like Trajectories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slingshot | High accuracy | High accuracy | Moderate accuracy | Not applicable | Low accuracy |

| TSCAN | High accuracy | Moderate accuracy | Low accuracy | Moderate accuracy | Low accuracy |

| Monocle DDRTree | High accuracy | High accuracy | High accuracy | Not applicable | Moderate accuracy |

| PAGA | Moderate accuracy | High accuracy | High accuracy | Low accuracy | High accuracy |

| SCORPIUS | High accuracy | Moderate accuracy | Low accuracy | Not applicable | Low accuracy |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Protocol for RNA Velocity Analysis

A robust protocol for RNA velocity analysis involves multiple stages from experimental design to computational interpretation:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Isolate cells of interest using standard single-cell protocols (FACS, microfluidics, etc.)

- Prepare libraries using scRNA-seq protocols that preserve intronic reads (e.g., 10X Genomics, inDrops)

- Sequence with sufficient depth to capture both spliced and unspliced transcripts (typically >50,000 reads/cell)

Data Preprocessing

- Quality control: Filter cells with low RNA content, high mitochondrial percentage, or outlier gene counts

- Preprocessing: The unspliced and spliced RNA abundances are preprocessed for velocity gene selection and pseudotime initialization [13]

- Dimensionality reduction: Perform PCA, UMAP, or t-SNE to project data into lower-dimensional space

Velocity Estimation

- Employ tools like Velocyto, scVelo, or Dynamo to estimate RNA velocity

- For in situ RNA velocity analysis, nuclear and cytoplasmic mRNA counts can substitute for unspliced and spliced counts [14]

- Visualize velocity vectors projected onto embedding (UMAP/t-SNE) to assess directionality

Trajectory Inference

- Apply trajectory inference methods (Slingshot, PAGA, Monocle) to reconstruct developmental paths

- Validate trajectories using known marker genes and developmental biology knowledge

Downstream Analysis

- Identify key regulator genes along trajectories

- Construct dynamic gene regulatory networks

- Perform differential expression testing across pseudotime

Advanced Protocol: TIGON for Dynamic Trajectory Inference

TIGON represents a recent advanced methodology that uses dynamic, unbalanced optimal transport to reconstruct dynamic trajectories and population growth simultaneously from multiple snapshots [15]. The protocol involves:

Input Data Preparation

- Collect time-series scRNA-seq data at multiple time points

- Estimate density functions at discrete time points using Gaussian mixture models

- Perform dimension reduction (PCA, UMAP, or autoencoder) to project into lower-dimensional space

Model Implementation

- Implement Wasserstein-Fisher-Rao (WFR) distance minimization using neural ODEs

- Approximate velocity v(x,t) and growth g(x,t) using neural networks

- Solve the hyperbolic partial differential equation: ∂tρ(x,t) + ∇·(v(x,t)ρ(x,t)) = g(x,t)ρ(x,t)

Trajectory and Growth Reconstruction

- Track cell dynamics by integrating along the velocity field

- Assess gene contributions to growth from the gradient of growth (∇g)

- Construct gene regulatory networks from the Jacobian of velocity

Validation

- Compare inferred trajectories with known lineage tracing data

- Validate growth predictions using experimental growth measurements

- Assess regulatory networks using known transcription factor-target relationships

Diagram 1: Single-cell trajectory analysis workflow

Recent Methodological Advances

Integration of Multi-Omics Data

Recent trajectory inference methods increasingly incorporate multi-omics data to enhance accuracy and biological relevance. Methods like MultiVelo extend RNA velocity analysis to single-cell ATAC-seq datasets, while protaccel extends it to protein abundance [13]. These integrated approaches recognize that cellular identity and fate decisions are determined through complex interactions between transcriptional, epigenetic, and proteomic layers.

TIGON represents another significant advancement by simultaneously modeling cell velocity and population growth within a unified optimal transport framework [15]. Traditional methods often assume constant cell numbers or neglect proliferation and death effects, potentially misrepresenting true dynamics. TIGON's incorporation of growth terms addresses this limitation, particularly important in developmental contexts with rapid cell division [15].

Deep Learning Approaches

Neural ordinary differential equations (ODEs) have emerged as powerful tools for modeling single-cell dynamics. TSvelo exemplifies this approach, implementing a comprehensive RNA velocity framework that models the cascade of gene regulation, transcription, and splicing using interpretable neural ODEs [13]. Unlike methods that treat genes independently, TSvelo integrates transcriptional regulation information from TF-target databases while maintaining parameter interpretability [13].

Another innovation involves generative models such as VeloVI, veloVAE, and Pyrovelocity, which utilize Bayesian frameworks to estimate RNA velocity with uncertainty quantification [13]. These approaches better account for the sparsity and noise inherent in single-cell data, particularly for genes with low expression levels.

Spatial Trajectory Inference

The integration of spatial information with trajectory inference represents a frontier in single-cell analytics. Methods like STT and SIRV extend RNA velocity analysis to spatial transcriptomics, enabling researchers to reconstruct developmental trajectories while preserving tissue architecture context [13]. For imaging-based spatial transcriptomics methods like MERFISH, RNA velocity can be inferred by distinguishing between nuclear and cytoplasmic mRNAs rather than spliced/unspliced ratios [14].

Diagram 2: Evolution of trajectory inference concepts

Successful implementation of pseudotime, RNA velocity, and trajectory analysis requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources. Below are essential components for designing experiments in this domain:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA-seq Platforms | 10X Genomics, inDrops, SMART-seq2 | Generate single-cell transcriptome data | Protocol choice affects detection of unspliced transcripts |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | MERFISH, Seq-Scope, 10X Visium | Provide spatial context for gene expression | Compatibility with RNA velocity analysis varies |

| Lineage Tracing Systems | CRISPR-based barcoding, fluorescent reporters | Establish ground truth for lineage relationships | May require custom computational integration |

| Reference Databases | ChEA, ENCODE TF-target databases | Provide prior knowledge for regulatory inference | Database selection influences regulatory network predictions |

| Velocity Estimation Tools | Velocyto, scVelo, Dynamo, TSvelo | Calculate RNA velocity from spliced/unspliced counts | Underlying assumptions and model complexity vary |

| Trajectory Inference Software | Slingshot, Monocle, PAGA, TSCAN | Reconstruct developmental trajectories from single-cell data | Performance depends on trajectory topology |

| Benchmarking Platforms | dynverse, BEELINE | Compare method performance and select optimal approaches | Essential for rigorous methodological selection |

| Visualization Tools | scVelo, Scanpy, Seurat | Project trajectories and velocities onto low-dimensional embeddings | Critical for biological interpretation and communication |

The field of temporal modeling in single-cell transcriptomics has evolved dramatically from initial pseudotime approaches to increasingly sophisticated methods that integrate multiple data modalities and leverage advanced computational frameworks. Current methods like TIGON and TSvelo demonstrate the power of combining optimal transport theory with neural ODEs to reconstruct complex developmental trajectories while accounting for population growth and gene regulatory networks [15] [13].

Looking forward, several challenges and opportunities remain. There is a growing need for methods that can better handle complex trajectory topologies, including loops, alternative paths, and cross-differentiation events [8] [10]. The integration of single-cell multi-omics data—including epigenomic, proteomic, and spatial information—will continue to enhance trajectory inference accuracy [9] [13]. Additionally, approaches that provide uncertainty quantification and robust statistical frameworks will be essential for translating trajectory inferences into biologically meaningful insights, particularly for clinical applications [9] [3].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances in temporal modeling offer unprecedented opportunities to map disease progression, identify novel therapeutic targets, and understand drug mechanisms at cellular resolution. As the field continues to mature, we anticipate that trajectory inference methods will become increasingly integral to both basic biological discovery and translational applications across diverse domains including developmental biology, cancer research, and regenerative medicine.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to characterize cellular heterogeneity, but traditional approaches present a fundamental limitation: they require cell lysis, providing only a single snapshot in time and impeding further molecular or functional analyses on the same cells [16] [17]. This destructive sampling creates a critical challenge in understanding how a cell's molecular state influences its response to perturbations, such as inflammatory signals or differentiation stimuli [16]. To address this, the field has developed innovative experimental designs that incorporate a temporal dimension, broadly categorized into computational inference methods and experimental recording techniques. Computational approaches like pseudotime ordering infer continuous trajectories based on transcriptome similarity, while experimental methods such as Live-seq directly record temporal changes by preserving cell viability [17]. This article details these methodologies, their protocols, and applications, providing a comprehensive toolkit for researchers investigating dynamic biological processes.

The table below summarizes the core experimental designs for capturing temporal information in single-cell transcriptomics, highlighting their fundamental principles, outputs, and key considerations.

Table 1: Strategies for Capturing Temporal Dynamics in Single-Cell Transcriptomics

| Strategy | Core Principle | Temporal Output | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live-seq [16] [18] | Cytoplasmic biopsy via FluidFM to extract mRNA while preserving cell viability. | Direct, sequential transcriptome measurements from the same live cell. | Enables direct coupling of a cell's ground state to its downstream phenotypic behavior. | Lower RNA recovery leading to fewer genes detected per cell compared to scRNA-seq. |

| Time-Series scRNA-seq [19] | Destructive sampling of cells from the same population at multiple time points. | A series of population-level snapshots across different time points. | Technically straightforward; uses established scRNA-seq protocols. | Cannot track the same cell over time; relies on population-level inference. |

| Time-Resolved Reporters [20] | Genetically engineered reporter systems (e.g., Gcg-Timer) that label cells based on their activation or differentiation state. | Indirect temporal information by distinguishing early vs. late cell states within a single sample. | Provides high temporal resolution for specific cell lineages without complex computations. | Limited to predefined biological processes and requires genetic modification. |

| Computational Inference (e.g., Pseudotime) [21] [17] | Algorithmic ordering of single-cell snapshots along a reconstructed trajectory based on transcriptome similarity. | Inferred continuous trajectory representing a biological process (e.g., development). | Can be applied to existing scRNA-seq data; no specialized wet-lab protocols needed. | Result is a statistical inference, not an actual timeline; directionality can be ambiguous. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Live-seq for Temporal Transcriptomic Recording

Live-seq transforms scRNA-seq from an end-point to a temporal analysis approach by using fluidic force microscopy (FluidFM) to perform cytoplasmic biopsies, allowing sequential molecular profiling of the same cell [16] [18].

Workflow Diagram: Live-seq

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Probe Preparation: Preload a FluidFM probe (with an aperture of 300-500 nm) with a sampling buffer containing RNase inhibitors. This is critical to immediately stabilize the minimal amount of RNA upon extraction [16].

- Cell Selection and Biopsy: Place the cell culture dish on the stage of an inverted microscope integrated with the FluidFM system. Use image-based cell tracking to identify and position a target cell. Lower the probe onto the cell membrane, apply gentle force and suction to penetrate the membrane and extract approximately 1 picoliter of cytoplasm [16].

- Sample Collection: Retract the probe and release the cytoplasmic extract into a microliter-scale droplet containing a buffer compatible with downstream RNA-seq library construction. Implement a stringent wash protocol for the FluidFM probe (>99% accuracy) between cells to prevent cross-contamination [16].

- Low-Input RNA Sequencing: Convert the extracted mRNA into a sequencing library using an optimized, high-sensitivity version of the Smart-seq2 protocol. This enhanced workflow is capable of reliably detecting as little as 1 picogram of total RNA, a necessity given the minimal input material [16].

- Downstream Phenotypic Monitoring: Following biopsy, the cell remains viable in culture. It can be subjected to various perturbations (e.g., LPS stimulation, differentiation induction) and monitored over time via time-lapse imaging or other functional assays to link its initial transcriptomic state to its subsequent behavior [16] [18].

Protocol 2: Time-Series scRNA-seq with Computational Trajectory Modeling

This design involves sacrificially harvesting cells from a population at multiple time points during a dynamic process, followed by scRNA-seq and computational analysis to reconstruct temporal trajectories [19].

Workflow Diagram: Time-Series scRNA-seq Analysis

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Experimental Time-Series Design: Plan and execute the biological experiment, collecting cells from the population at key time points. For example, collect immune cells before and at several intervals after stimulation, or collect cells at different stages of embryonic development [20] [19].

- Single-Cell Library Preparation and Sequencing: For each time point, prepare a single-cell suspension. Generate barcoded scRNA-seq libraries using a preferred platform (e.g., droplet-based 10x Genomics, or full-length Smart-seq2 for higher sensitivity). Pool and sequence the libraries [22] [23].

- Data Preprocessing and Integration: Process the raw sequencing data to generate a gene expression count matrix for each cell. Use tools like Seurat or Scanpy to perform quality control, normalize data, and integrate cells from different time points to correct for batch effects [23].

- Trajectory Inference: Apply pseudotime inference algorithms such as Slingshot [21], Monocle, or TSCAN. These tools order individual cells along a reconstructed trajectory based on transcriptomic similarity, effectively creating a "pseudotime" axis from the start to the end of the biological process [21] [17] [19].

- Analysis of Dynamic Gene Behavior: Model how gene expression and interactions change along the inferred pseudotime.

- Differential Expression: Use tools like

tradeSeqto identify genes with non-linear expression changes over pseudotime [21]. - Gene Co-Expression Analysis: Employ methods like TIME-CoExpress, a copula-based framework that models non-linear changes in gene-gene co-expression patterns, dynamic zero-inflation rates, and mean expression levels along the temporal trajectory [21].

- Differential Expression: Use tools like

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of temporal single-cell transcriptomics relies on a suite of specialized reagents and platforms. The table below catalogues essential solutions for key methodological steps.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Temporal scRNA-seq

| Category / Reagent | Specific Examples | Function & Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | ||

| - High-Sensitivity Full-Length | Smart-seq2, Smart-seq3 [17] | Optimal for Live-seq and low-input samples; provides full transcript coverage. Smart-seq3 offers improved sensitivity with 5'-UMI counting. |

| - High-Throughput 3' | 10x Genomics Chromium, Parse Biosciences Evercode [22] [24] | For large time-series studies. Parse's combinatorial barcoding can process millions of cells from thousands of samples. |

| Cell Capture & Isolation | ||

| - Microfluidics Platform | 10x Genomics, BD Rhapsody [22] [23] | Encapsulates single cells into droplets or microwells for barcoding. |

| - Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | N/A [23] | Enriches for specific cell populations prior to sequencing (e.g., using fluorescent reporters like Gcg-Timer [20]). |

| Critical Enzymes & Buffers | ||

| - Reverse Transcriptase | Superscript IV (SSRTIV) [17] | Used in FLASH-seq for higher processivity, improving gene detection in full-length protocols. |

| - RNase Inhibitors | N/A [16] | Essential for Live-seq to preserve RNA integrity during and after cytoplasmic extraction. |

| Specialized Systems | ||

| - Fluidic Force Microscopy | FluidFM [16] [18] | The core technology enabling Live-seq, allowing for cytoplasmic extraction with minimal invasiveness. |

Application Notes in Biological Research

Immune Response and Macrophage Polarization

Live-seq has been applied to pre-register the transcriptomes of individual macrophages before stimulating them with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). This enabled the identification of basal gene expression features, such as Nfkbia levels and cell cycle state, which predicted the strength of the subsequent inflammatory response, uncovering determinants of response heterogeneity [16].

Pancreatic Cell Development and Differentiation

Time-resolved reporter systems, such as the Gcg-Timer mouse, allow for the isolation of early versus late α-cells during embryonic development at E17.5. scRNA-seq of these sorted populations revealed transcriptional dynamics, showing that early α-cells express key β-cell genes like Ins1 and Ins2 before maturing into Gcg-high late α-cells, providing insights into endocrine cell differentiation [20].

Drug Discovery and Biomarker Identification

In drug development, time-series scRNA-seq can profile cellular responses to compounds at multiple doses and time points. This identifies cell-type-specific transcriptomic changes, mechanisms of efficacy and resistance, and predictive biomarkers. The ability to stratify patients based on dynamic molecular responses within cell subpopulations is invaluable for personalized medicine [24].

The integration of temporal resolution into single-cell transcriptomics is rapidly advancing our understanding of dynamic biological systems. Experimental designs now range from repeated destructive sampling to the groundbreaking Live-seq technology, which allows direct longitudinal tracking of the same cell. Coupled with sophisticated computational models for analyzing time-series and pseudotime data, these methods provide a powerful means to move beyond static snapshots. As these protocols continue to mature—driving increases in sensitivity, throughput, and analytical depth—they will undoubtedly unlock deeper insights into developmental biology, disease progression, and therapeutic interventions, firmly establishing time as a fundamental dimension in single-cell research.

Key Biological Questions Addressed by Temporal Modeling (e.g., Differentiation, Immune Response)

Biological systems are inherently dynamic, with processes such as cellular differentiation, immune response, and disease progression unfolding over time. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to observe these processes by providing high-resolution views of transcriptomic states at the cellular level. However, conventional scRNA-seq offers only static snapshots, posing significant challenges for understanding temporal sequences and causal relationships [25].

Temporal modeling computational frameworks bridge this gap by ordering cells along pseudotime trajectories, inferring RNA velocity, and integrating multi-omics data to reconstruct dynamic biological pathways. These approaches have become indispensable for addressing fundamental biological questions that involve state transitions and temporal progression [26]. This article explores the key biological questions where temporal modeling provides critical insights, detailing the experimental and computational protocols that enable these discoveries.

Key Biological Questions and Applications

Temporal modeling of single-cell transcriptomic data has been successfully applied to address several fundamental questions in biology and medicine. The table below summarizes the primary biological questions, key findings, and analytical techniques used in recent studies.

Table 1: Key Biological Questions Addressed by Temporal Modeling

| Biological Question | Key Findings | Analytical Techniques | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Differentiation & Development | Ordered lineage commitment, temporal specificity of disorder-risk genes in brain development, pituitary gland embryogenesis | Pseudotime analysis, RNA velocity, trajectory inference, gene co-expression dynamics | [21] [27] |

| Immune Response Dynamics | Rapid activation of intestinal CD8+ T cells and plasma cells during Salmonella infection; "immune clock" in sepsis with defined critical windows | scIVNL-seq for new/old RNA, differential equation models, multi-omics fusion | [28] [29] |

| Disease Progression | Transition from ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) to invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) in breast cancer; identification of T cell subsets and key prognostic genes | Cell-cell communication analysis, pseudotime trajectory of T cells, WGCNA | [30] |

| Therapeutic Intervention Timing | Identification of two intervention windows in sepsis (0-18h and 36-48h) forecasting 2.1-fold and 1.6-fold survival gains, respectively | Dynamic simulations, ordinary differential equations (ODEs), stochastic differential equations (SDEs) | [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Temporal Resolution

Metabolic Labelling for RNA Dynamics

Protocol: scIVNL-seq (Single-cell In Vivo New RNA Labeling Sequencing)

Purpose: To distinguish newly synthesized transcripts from pre-existing RNAs, providing direct measurement of transcriptional activity and degradation in vivo [28].

Workflow Diagram:

Key Reagents and Solutions:

- 4-thiouridine (S4U): Nucleoside analog incorporated into nascent RNA during transcription [28] [26].

- Tail Vein Catheterization Setup: For precise intravenous administration in mouse models.

- Cell Dissociation Kit: Tissue-specific enzymatic mix for single-cell suspension preparation.

- 10x Genomics Chromium System: For droplet-based single-cell encapsulation and barcoding.

- UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) Adapters: For digital counting and accurate transcript quantification.

Multi-Omics Integration for Temporal Networks

Protocol: Multi-Omics Temporal Network Reconstruction in Sepsis

Purpose: To integrate scRNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and CITE-seq data for reconstructing a time-resolved "immune clock" of sepsis progression, identifying critical checkpoints and intervention windows [29].

Workflow Diagram:

Key Reagents and Solutions:

- Cell Hashing Antibodies: For sample multiplexing and demultiplexing in CITE-seq.

- Tn5 Transposase: For tagmentation in ATAC-seq library preparation.

- Feature Barcoding Kit: For simultaneous surface protein detection.

- scMGNN Tool: Computational tool for multi-omics data harmonization [29].

- Palantir: For pseudotime analysis and trajectory construction [27].

Computational Methods for Temporal Modeling

Pseudotime and Trajectory Inference

Protocol: TIME-CoExpress for Dynamic Co-Expression Analysis

Purpose: To model non-linear changes in gene co-expression patterns, zero-inflation rates, and mean expression levels along cellular temporal trajectories [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Methods for Temporal Modeling

| Method | Primary Function | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIME-CoExpress | Models non-linear gene co-expression | Copula-based framework, handles zero-inflation, multi-group comparison | Computationally intensive for large gene sets [21] |

| Slingshot | Pseudotime inference | Unsupervised, robust to noise, multiple lineage inference | Requires predefined clusters [21] |

| Monocle | Pseudotime and trajectory analysis | Orders cells using transcriptome similarity | Infers rather than measures true time [26] |

| RNA Velocity | Predicts future cell states | Based on spliced/unspliced RNA ratio | More applicable to steady-state models [26] |

| scHOT | Detects changing gene interactions | Uses Spearman's correlation along trajectories | Cannot simultaneously analyze multiple groups [21] |

Workflow Diagram:

Signaling Pathway Dynamics Visualization

Protocol: Temporal Analysis of Immune Signaling Pathways

Application: Mapping the dynamics of critical signaling pathways (e.g., NF-κB, PD-1/TIM-3) during immune activation and exhaustion in sepsis and cancer [29] [30].

Workflow Diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Temporal scRNA-seq Studies

| Category | Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Labeling | 4-thiouridine (S4U) | Labels nascent RNA for transcriptional dynamics | scIVNL-seq, scSLAM-seq [28] [26] |

| Metabolic Labeling | TimeLapse Chemistry | Converts S4U to cytosine analogue for droplet-based platforms | scNT-seq [25] |

| Cell Sorting | Fluorescent Reporters (e.g., Neurog3Chrono) | Visualizes temporal progression via fluorescent protein ratios | Cell fate tracing studies [25] |

| Single-Cell Profiling | 10x Genomics Chromium | High-throughput single-cell encapsulation and barcoding | Most large-scale scRNA-seq studies [30] |

| Multi-Omics | CITE-seq Antibodies | Simultaneous measurement of surface proteins | Immune cell phenotyping [29] |

| Multi-Omics | ATAC-seq Reagents | Chromatin accessibility profiling | Regulatory network inference [29] |

| Computational Tools | scVILNL-seq Analysis Pipeline | Quantifies new vs. old RNA and calculates transcription rates | Immune response studies [28] |

| Computational Tools | TIME-CoExpress R/Package | Identifies dynamic gene co-expression patterns | Developmental studies [21] |

The Computational Toolbox: Methods for Inferring and Modeling Cellular Trajectories

Trajectory Inference and Pseudotime Ordering with Tools like Slingshot and Monocle

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biology by allowing researchers to profile transcript abundance at the resolution of individual cells, opening new avenues to study dynamic processes such as cell differentiation, development, and disease progression [31] [32]. However, standard scRNA-seq provides only static cellular snapshots, obscuring temporal processes because the technique is inherently destructive to cells [31] [33]. Trajectory inference (TI) has emerged as a powerful computational approach to overcome this limitation by ordering cells along inferred developmental trajectories based on transcriptional similarities [31]. This ordering produces a "pseudotime" value for each cell, representing its relative progression along a continuous biological process [34]. For example, in differentiation processes, pseudotime can represent the degree of differentiation from a pluripotent stem cell to a fully differentiated terminal state [34].

The core assumption underlying trajectory inference is that cells undergoing transitions between states will create a continuum in gene expression space, and that sufficient sampling will capture cells at various points along these transitions [31]. TI methods aim to connect these cells through their transcriptional similarities, effectively reconstructing the temporal dynamics from static snapshots [31] [32]. These approaches have become indispensable for studying processes where direct temporal monitoring is impossible, allowing researchers to map complex lineage relationships and identify molecular drivers of cellular fate decisions [31] [32]. Within the broader context of temporal modelling in single-cell transcriptomics development research, trajectory inference provides a foundational framework for understanding how gene expression programs unfold over time, offering insights into normal development, disease mechanisms, and potential therapeutic interventions [3].

Theoretical Foundations of Pseudotime and Lineage Inference

Conceptual Framework of Pseudotime

Pseudotime is a computational construct that quantifies the relative progression of individual cells along a biological process [34]. It is important to note that "pseudotime" may not have a linear relationship with real chronological time; rather, it represents transcriptional progression along a continuum [34]. For time-dependent processes like differentiation, pseudotime can serve as a proxy for relative cellular age, but only when directionality can be reliably inferred [34]. In branched trajectories, cells typically receive multiple pseudotime values—one for each path through the trajectory—and these values are generally not comparable across different paths [34].

The mathematical inference of pseudotime relies on the assumption that cells with similar transcriptional profiles occupy similar positions in the developmental continuum [31]. The process begins with dimensionality reduction to address the high-dimensional nature of scRNA-seq data, followed by the inference of global lineage structures, and finally the projection of cells onto these structures to assign pseudotime values [32]. A critical consideration is whether a continuous trajectory actually exists in the dataset, as continua can sometimes be interpreted as series of closely related but distinct subpopulations, while separated clusters might represent endpoints of a trajectory with rare intermediates [34]. This interpretive flexibility requires analysts to choose perspectives based on biological plausibility and utility [34].

Methodological Approaches to Lineage Inference

Multiple computational approaches have been developed for lineage inference, each with distinct theoretical foundations and algorithmic strategies. Cluster-based minimum spanning tree (MST) methods, implemented in tools like TSCAN and the first stage of Slingshot, cluster cells then construct a minimum spanning tree on cluster centroids to identify the most parsimonious connections between cellular states [34] [33]. The MST provides an intuitive representation of transitions between clusters, with paths through the tree representing potential lineages [34]. Principal curves approaches, used in the second stage of Slingshot and similar methods, fit smooth one-dimensional curves that pass through the middle of data in high-dimensional space, providing a nonlinear summary of the data [35] [33]. These curves effectively capture continuous transitions without discrete clustering steps. Graph-based learning methods, employed by Monocle 2 and later versions, use machine learning strategies like reversed graph embedding to learn principal graphs that describe the single-cell dataset while simultaneously mapping points back to the original high-dimensional space [33]. Partition-based graph abstraction, implemented in PAGA, creates graph representations of cellular relationships using a multi-resolution approach that combines clustering and continuous transition models [31].

Each approach presents distinct advantages: cluster-based methods offer computational efficiency and noise resistance [34]; principal curves provide smooth, continuous representations [35]; graph-learning methods capture complex branching patterns [33]; and partition-based approaches handle disconnected clusters and sparse sampling effectively [31]. The choice among these methodologies depends on dataset characteristics, trajectory complexity, and analytical goals.

Comparative Analysis of Slingshot and Monocle

Slingshot represents a modular approach to trajectory inference that combines cluster-based stability with flexible curve-fitting [35]. Its algorithm consists of two distinct stages: first, it identifies global lineage structure using a cluster-based minimum spanning tree (MST), which stably identifies the number of lineages and branching points; second, it fits simultaneous principal curves to these lineages to estimate cell-level pseudotime variables for each lineage [35] [33]. This two-stage approach provides robustness to noise—a critical feature for noisy single-cell data—while accommodating multiple branching lineages [35]. A key advantage of Slingshot is its flexibility regarding upstream preprocessing steps; it does not require specific clustering, normalization, or dimensionality reduction methods, allowing integration into diverse analytical workflows [35].

Monocle exists in several iterations, each with distinct algorithmic approaches. The original Monocle constructed a minimum spanning tree on individual cells using independent component analysis (ICA) and ordered cells via a PQ tree along the longest path [35]. Monocle 2 introduced reversed graph embedding (RGE), specifically using DDRTree (Discriminative Dimensionality Reduction via Learning a Tree), to simultaneously learn a principal graph and map cells onto it [33]. Monocle 3 further evolved this approach by using UMAP for dimensionality reduction, Louvain/Leiden algorithms for clustering, and a variant of SimplePPT algorithm to construct trajectories that can accommodate multiple origins, cycles, and converging states [31] [33]. Unlike Slingshot's two-stage process, Monocle 3 integrates dimensionality reduction, clustering, and graph construction into a more unified framework.

Performance Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Comparative Performance Characteristics of Slingshot and Monocle

| Feature | Slingshot | Monocle 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Core Algorithm | Two-stage: Cluster-based MST + simultaneous principal curves | Unified: UMAP + graph learning + principal graph |

| Lineage Identification | Unsupervised, with optional supervision of terminal states | Unsupervised, with optional root specification |

| Pseudotime Stability | High (robust to subsampling) [35] | Varies with parameters and dataset size |

| Branching Capacity | Multiple branching lineages | Complex topologies (branches, cycles, convergences) [31] |

| Scalability | Moderate to large datasets | Designed for large datasets (millions of cells) [31] |

| Workflow Integration | Highly modular and flexible [35] | More self-contained with prescribed steps |

| Upstream Requirements | Compatible with various clustering/dimensionality reduction methods | Typically uses its own dimensionality reduction and clustering |

Simulation studies have demonstrated that Slingshot infers more accurate pseudotimes than other leading methods and shows particularly high stability when compared to Monocle 1's approach [35]. The cluster-based MST approach of Slingshot provides protection against noise that can destabilize methods working directly with individual cells [35]. Meanwhile, Monocle 2 and 3 have shown improved performance over their predecessor, with Monocle 3 specifically designed to handle the scale and complexity of modern single-cell datasets [31] [33]. Both methods can identify branching trajectories, but they differ in their capacity for handling complex topologies—where Slingshot specializes in multiple branching lineages, Monocle 3 extends to more complex structures including cycles and multiple origins [31].

In practical applications, Slingshot had consistently performing well across different datasets according to benchmarking studies [33], while Monocle 3's integration with modern dimensionality reduction techniques like UMAP makes it suitable for exploring complex cellular relationships in large datasets [31] [33]. The choice between these tools often depends on specific dataset characteristics, analytical needs, and the preferred workflow structure, with Slingshot offering modular flexibility and Monocle 3 providing an integrated solution.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Slingshot Workflow Protocol

Sample Input Preparation The Slingshot workflow begins with properly formatted input data. While Slingshot is flexible regarding upstream steps, it typically operates on reduced-dimensional representations of single-cell data [35]. The essential starting point is a matrix of normalized expression counts, along with cell cluster assignments, which can be generated using various clustering methods deemed appropriate for the specific dataset [35]. For optimal performance, Street et al. recommend using a data analysis pipeline that includes data-adaptive selection of normalization procedures (e.g., using the scone package), dimensionality reduction using methods like zero-inflated negative binomial models (zinbwave package), and resampling-based sequential ensemble clustering (clusterExperiment package) [35].

Step-by-Step Implementation

- Global Lineage Structure Inference: Slingshot first identifies the overall lineage structure by constructing a minimum spanning tree (MST) on cluster centroids [35] [33]. This step determines the number of lineages and where they branch. Users can optionally specify known terminal states to guide the tree construction, particularly useful when prior biological knowledge exists about endpoint cell types [35].

Curve Fitting and Pseudotime Calculation: For each identified lineage, Slingshot fits a principal curve using the simultaneous principal curves method [35] [33]. This approach extends traditional principal curves to handle branching lineages. Cells are then projected onto the closest curve, and pseudotime is calculated as the distance along the curve from a user-specified starting cluster [35].

Output Interpretation: The output includes pseudotime values for each cell along each lineage. These values can be used for downstream analyses such as identifying genes associated with lineage differentiation [33]. The following DOT script visualizes this workflow:

Diagram Title: Slingshot Two-Stage Workflow

Parameter Optimization and Troubleshooting For the cluster-based MST step, Slingshot performance remains relatively stable across different clustering methods and parameters, though performance gradually decreases with very high cluster counts [35]. The principal curves stage requires specification of a starting cluster; biological knowledge should guide this selection when available [35]. If trajectories appear overly complex or capture biologically implausible connections, adjusting cluster granularity or incorporating domain knowledge to specify terminal states can improve results [35].

Monocle 3 Workflow Protocol

Input Data Preparation Monocle 3 requires data in Cell Data Set (CDS) format, which contains three key components: (1) a numeric expression matrix with genes as rows and cells as columns; (2) a data frame of cell metadata with rows corresponding to cells and columns containing cell attributes; and (3) a data frame of gene metadata with rows corresponding to features, including a column named "geneshortname" containing gene symbols [36]. For trajectory inference, users must also specify starting points (root cells), which can be provided as a list of cell names or selected from cell metadata columns [37] [38].

Comprehensive Step-by-Step Protocol

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalization: Monocle 3 offers log-normalization or size-factor normalization options to minimize non-biological variation [37] [38]. Log normalization standardizes data, while size-factor normalization removes technical bias by dividing counts by cell-specific size factors.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensions. For datasets exceeding 5,000 cells, selecting the top 50 principal components is recommended [37]. Scaling before PCA computation is beneficial when dealing with variables in different units.

- Further Reduction: Apply UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) for additional dimensionality reduction. Set UMAP parameters appropriately: lower minimum distance values result in denser clusters, while higher values preserve broad topological structure; lower neighbor values emphasize local structure, while higher values provide a broader view [37].

Clustering and Trajectory Construction:

- Clustering: Cluster cells using Louvain or Leiden algorithms. The resolution parameter controls granularity—higher values generate more, smaller clusters [38]. Monocle 3 can also use cluster labels from previous analyses (e.g., Seurat clusters).

- Trajectory Control: Enable "allow disjoint graph" to merge partitions into a single trajectory or "allow loops" to discover potential cyclic trajectories [37]. Prune branches that don't meet specific length criteria by setting minimum branching length.

Pseudotime Calculation:

- Root Selection: Specify root nodes (starting cells) for trajectory construction, which serve as reference points. These can be progenitor cells, undifferentiated cells, or cells from initial time points [37] [38].

- Ordering: Monocle 3 projects cells onto the learned trajectory and computes pseudotime as the distance from root nodes. In cases of multiple root nodes, pseudotimes are taken as the minimum distance across all roots [31].

The following DOT script illustrates the complete Monocle 3 workflow:

Diagram Title: Monocle 3 Integrated Workflow

Parameter Optimization Guidelines Critical parameters requiring optimization include: (1) PCA dimensions, which significantly impact downstream results—insufficient dimensions may miss important biological signals, while excessive dimensions increase noise [36]; (2) UMAP parameters, particularly minimum distance and number of neighbors, which control trajectory topology [37]; (3) clustering resolution, which affects trajectory granularity [38]; and (4) minimum branch length for pruning, which determines whether minor branches are retained [38]. Systematic parameter testing is essential, as optimal values vary across datasets.

Downstream Analytical Applications

Trajectory-Based Differential Expression Analysis

Once pseudotime values are assigned, a crucial next step is identifying genes that change their expression patterns along trajectories or between lineages. The tradeSeq package provides a powerful generalized additive model (GAM) framework for this purpose, addressing limitations of discrete cluster-based comparisons [32]. tradeSeq fits smooth functions of gene expression along pseudotime for each lineage using negative binomial generalized additive models, then tests biologically meaningful hypotheses about expression patterns [32]. The model can be specified as:

$$\left{\begin{array}{lll}{Y}{gi} \sim NB({\mu }{gi},{\phi }{g})\ {\mathrm{log}}\,({\mu }{gi})={\eta }{gi} \quad \ {\eta }{gi}=\sum {l=1}^{L}{s}{gl}({T}{li}){Z}{li}+{{\bf{U}}}{i}{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}{g}+{\mathrm{log}}\,({N}_{i})\end{array}\right.$$

where $Y{gi}$ represents read counts for gene $g$ across cells $i$, $s{gl}$ are lineage-specific smoothing splines functions of pseudotime $T{li}$, $Z{li}$ assigns cells to lineages, $Ui$ contains cell-level covariates, and $Ni$ accounts for sequencing depth differences [32].

tradeSeq implements several distinct tests for different biological questions: (1) testing whether expression is associated with pseudotime along a specific lineage; (2) detecting genes with different expression patterns between lineages; and (3) identifying genes that show different expression patterns at regions where lineages diverge [32]. This approach provides greater interpretability than earlier methods like GPfates or BEAM, which could not pinpoint specific regions of expression differences between lineages [32].

Analyzing Dynamic Gene Co-expression Patterns

Beyond analyzing individual genes, trajectory inference enables investigation of how gene-gene interactions change along developmental processes. TIME-CoExpress is a recently developed copula-based framework that models non-linear changes in gene co-expression patterns along cellular temporal trajectories [21]. This method addresses limitations of approaches that assume static correlations or linear relationships, providing flexibility to capture complex, non-linear changes in gene co-expression [21].

A unique feature of TIME-CoExpress is its ability to model dynamic gene-level zero-inflation rates along pseudotime, capturing the biological "on-off" characteristics of gene expression [21]. The framework uses an additive distributional regression approach that extends generalized additive models for location, scale, and shape (GAMLSS) to include zero-inflation, allowing multiple parameters of the response distribution to be linked to covariates through additive predictors [21]. TIME-CoExpress also supports multi-group analysis, enabling direct comparison of gene co-expression patterns between experimental conditions (e.g., wild-type vs. mutant) within a unified analytical framework [21].

Application of TIME-CoExpress to a mouse pituitary gland embryological development scRNA-seq dataset identified differentially co-expressed gene pairs along cellular temporal trajectories between $Nxn^{-/-}$ mice and wild-type controls, revealing genes with zero-inflation patterns consistent with known biological processes [21].

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Trajectory Inference and Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Slingshot | Two-stage trajectory inference: cluster-based MST + simultaneous principal curves | R/Bioconductor |

| Monocle 3 | Comprehensive single-cell analysis: trajectory inference with graph learning | R |

| tradeSeq | Trajectory-based differential expression using generalized additive models | R/Bioconductor |

| TIME-CoExpress | Modeling dynamic gene co-expression patterns along trajectories | R |

| Bioconductor | Repository of bioinformatics packages for single-cell analysis | Platform |

| Seurat | Single-cell preprocessing, clustering, and integration | R |

| SCONE | Data-adaptive normalization selection | R/Bioconductor |

| ZINB-WaVE | Zero-inflated negative binomial dimensionality reduction | R/Bioconductor |

| ClusterExperiment | Resampling-based sequential ensemble clustering | R/Bioconductor |

Experimental Design Considerations Successful trajectory inference requires careful experimental design and preprocessing. Critical wet-lab considerations include: (1) ensuring sufficient cell sampling to capture continuous transitions—sparse sampling may create gaps leading to ambiguous trajectories [31]; (2) using appropriate normalization to minimize technical variation [37]; (3) selecting dimensionality reduction methods compatible with trajectory inference tools [35]; and (4) incorporating biological replicates when comparing conditions using multi-group analysis frameworks [21].

For computational implementation, the research reagents table highlights essential tools, but their effective use requires appropriate computational infrastructure. Large-scale single-cell datasets (exceeding 5,000 cells) typically require high-performance computing resources with substantial memory allocation [37]. The modular nature of tools like Slingshot allows integration into customized workflows, while Monocle 3 offers a more integrated solution [35] [31]. Downstream analysis tools like tradeSeq and TIME-CoExpress extend the analytical scope to identify dynamically expressed genes and changing interaction patterns [21] [32].

Trajectory inference methods like Slingshot and Monocle have fundamentally expanded our ability to extract dynamic information from static single-cell transcriptomics snapshots, providing powerful frameworks for modeling temporal processes in development, differentiation, and disease progression. Slingshot's two-stage approach combining cluster-based MST with simultaneous principal curves offers robustness and flexibility, while Monocle 3's integrated graph-learning strategy handles complex trajectory topologies at scale [35] [31]. Both methods enable the inference of pseudotime orderings that serve as foundations for downstream analyses investigating gene expression dynamics and regulatory relationships along biological continua.

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging directions pushing trajectory inference beyond current capabilities. RNA velocity and related concepts that leverage unspliced pre-mRNA information represent a significant advancement, allowing inference of instantaneous gene expression change rates and prediction of future transcriptional states [3]. Second-generation tools like scVelo, dynamo, and CellRank generalize the original RNA velocity concept, offering more sophisticated models of transcriptional dynamics [3]. Integration with spatial transcriptomics data provides another exciting frontier, contextualizing temporal dynamics within tissue architecture [3]. Deep learning approaches are also emerging, potentially offering enhanced scalability and pattern recognition capabilities for complex trajectory inference problems [3].

As these methodological advances continue, trajectory inference will play an increasingly central role in temporal modeling of single-cell transcriptomics, particularly in therapeutic contexts like drug development where understanding cellular transition pathways can identify intervention points for disease modification. The protocols and applications detailed in this document provide a foundation for researchers to implement these powerful analytical approaches, with appropriate tool selection guided by specific biological questions, dataset characteristics, and analytical requirements.

Time-series single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) provides unprecedented snapshots of cellular systems at multiple time points, yet the destructive nature of sequencing means these snapshots remain unconnected, missing the continuous dynamic trajectories of cellular development and gene regulation [6]. TIGON (Trajectory Inference with Growth via Optimal transport and Neural network) represents a significant methodological advancement by introducing a dynamic, unbalanced optimal transport algorithm that simultaneously reconstructs dynamic trajectories and population growth from multiple scRNA-seq snapshots [6]. This capability positions TIGON as a powerful tool for researchers investigating developmental biology, disease progression, and drug response mechanisms, where understanding both cellular movement through gene expression space and population expansion or contraction is critical.

Within the broader context of temporal modelling in single-cell transcriptomics, TIGON addresses a fundamental limitation of previous methods: the inability to simultaneously capture gene expression velocity and cell population growth. While existing approaches like pseudotime ordering and RNA velocity infer cellular transitions, they often assume stationarity or equilibrium and cannot capture temporally evolving dynamics such as development [6] [39]. TIGON's integration of growth dynamics makes it particularly valuable for studying processes like tissue development, cancer evolution, and cell differentiation where proliferation plays a crucial role.

Theoretical Foundation and Algorithmic Innovation

Mathematical Framework

TIGON formulates cellular dynamics using a hyperbolic partial differential equation that describes the evolution of cell density ρ(x,t) in gene expression space over time [6]:

In this equation, the convection term ∇·(v(x,t)ρ(x,t)) describes the transport of cell density through gene expression space, with velocity v(x,t) representing the instantaneous change of gene expression for cells at state x and time t. The growth term g(x,t)ρ(x,t) describes the instantaneous population change due to cell division or death [6]. This formulation effectively decouples the two fundamental dynamics: directional movement in gene expression space (differentiation) and population-scale expansion or contraction (growth).

To solve this high-dimensional problem, TIGON implements an unbalanced optimal transport approach based on the Wasserstein-Fisher-Rao (WFR) distance, which generalizes optimal transport to measures of different masses [6]. The method minimizes the WFR cost:

where α balances the contributions of velocity and growth to the overall dynamics [6]. This formulation simultaneously captures the kinetic energy of cellular movement and the energy associated with population growth.

Computational Implementation

TIGON employs a deep learning approach to tackle the computational challenges of high-dimensional gene expression space. Two neural networks approximate the velocity v(x,t) ≈ NN1(x,t) and growth g(x,t) ≈ NN2(x,t) fields [6]. Through a dimensionless formulation of the WFR-based dynamic unbalanced optimal transport problem, TIGON transforms the partial differential equation into a system of ordinary differential equations solvable by neural ordinary differential equations (ODEs) [6].

For practical application to high-dimensional scRNA-seq data, TIGON first performs dimension reduction using methods like principal component analysis (PCA) or autoencoders (AE), which are reversible and differentiable, allowing direct approximation of the growth gradient and computation of the regulatory matrix [6]. When no prior information about cell population is available, TIGON assumes the cell population is represented by the number of cells collected at each time point [6].

Table 1: Core Mathematical Components of TIGON

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Density | ρ(x,t) | Distribution of cells in gene expression space at time t | ||||

| Velocity Field | v(x,t) | Instantaneous rate and direction of gene expression change | ||||

| Growth Function | g(x,t) | Net rate of cell population change (division - death) | ||||

| WFR Distance | ∫∫( | v(x,t) | ² + α | g(x,t) | ²)ρ(x,t)dxdt | Cost function balancing transport and growth |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the complete TIGON analysis workflow from data input to biological interpretation:

Data Preparation and Preprocessing Protocol

Input Requirements: