Comparative Phylogeography: Decoding Connectivity Patterns from Ecosystems to Drug Discovery

This article explores the power of comparative phylogeography, a discipline that analyzes the geographic distribution of genetic lineages across multiple co-distributed species to infer shared historical processes.

Comparative Phylogeography: Decoding Connectivity Patterns from Ecosystems to Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the power of comparative phylogeography, a discipline that analyzes the geographic distribution of genetic lineages across multiple co-distributed species to infer shared historical processes. We detail its foundational principles, from revealing vicariance events and demographic responses to climatic cycles to its methodological evolution in the genomics era. For our target audience of researchers and drug development professionals, we critically examine applications in forecasting infectious disease spread and bioprospecting for medicinal compounds. The article also addresses key methodological challenges, including distinguishing true vicariance from pseudocongruence and the pitfalls of applying these techniques to non-equilibrium systems like invasive species. Finally, we synthesize how validating patterns across diverse biomes—from neotropical mountains to ocean benthos—provides a robust, process-based framework for conservation planning and understanding the evolutionary drivers of chemical diversity.

The Bedrock of Biotic History: How Comparative Phylogeography Reveals Shared Evolutionary Processes

Abstract Phylogenetics and population genetics represent two foundational pillars of evolutionary biology. Phylogenetics infers the evolutionary relationships among species, while population genetics deciphers the genetic structure and processes within species. Comparative phylogeography emerges as a powerful integrative discipline that bridges this gap, leveraging the strengths of both to unravel the historical biogeographic processes and connectivity patterns that shape biodiversity across space and time. This guide objectively compares the conceptual frameworks, analytical tools, and applications of these interconnected fields, providing a structured overview for researchers in evolutionary biology and drug development.

1. Conceptual Frameworks: A Comparative Overview

The table below summarizes the core objectives, spatial and temporal scales, and key analytical methods that characterize phylogenetics, population genetics, and the bridging field of comparative phylogeography.

Table 1: Comparative Framework of the Three Disciplines

| Feature | Phylogenetics | Population Genetics | Comparative Phylogeography |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Infer evolutionary relationships and divergence times among species or higher taxa [1]. | Understand the distribution and dynamics of genetic variation within and between populations [2]. | Identify shared biogeographic histories and community-level processes across co-distributed species [3] [4] [5]. |

| Typical Scale | Macroevolutionary (species and above); deep time. | Microevolutionary (within species); contemporary to recent history. | Mesoevolutionary (within and between species); from recent history to the Quaternary period [3]. |

| Key Analytical Methods | Construction of phylogenetic trees, estimation of divergence times. | Analysis of allele frequencies, genetic differentiation (FST), effective population size. | Nested clade analysis, population genetic structure analysis, tests for phylogeographic concordance [4] [6] [5]. |

| Genetic Marker Focus | Often uses slowly evolving genes or many genomic loci to resolve deep branches. | Uses highly variable markers (e.g., microsatellites, SNPs) to detect population-level processes. | Primarily uses mitochondrial DNA and nuclear sequences; increasingly uses SNPs from genomic data [3] [4] [7]. |

2. The Bridge: Comparative Phylogeography

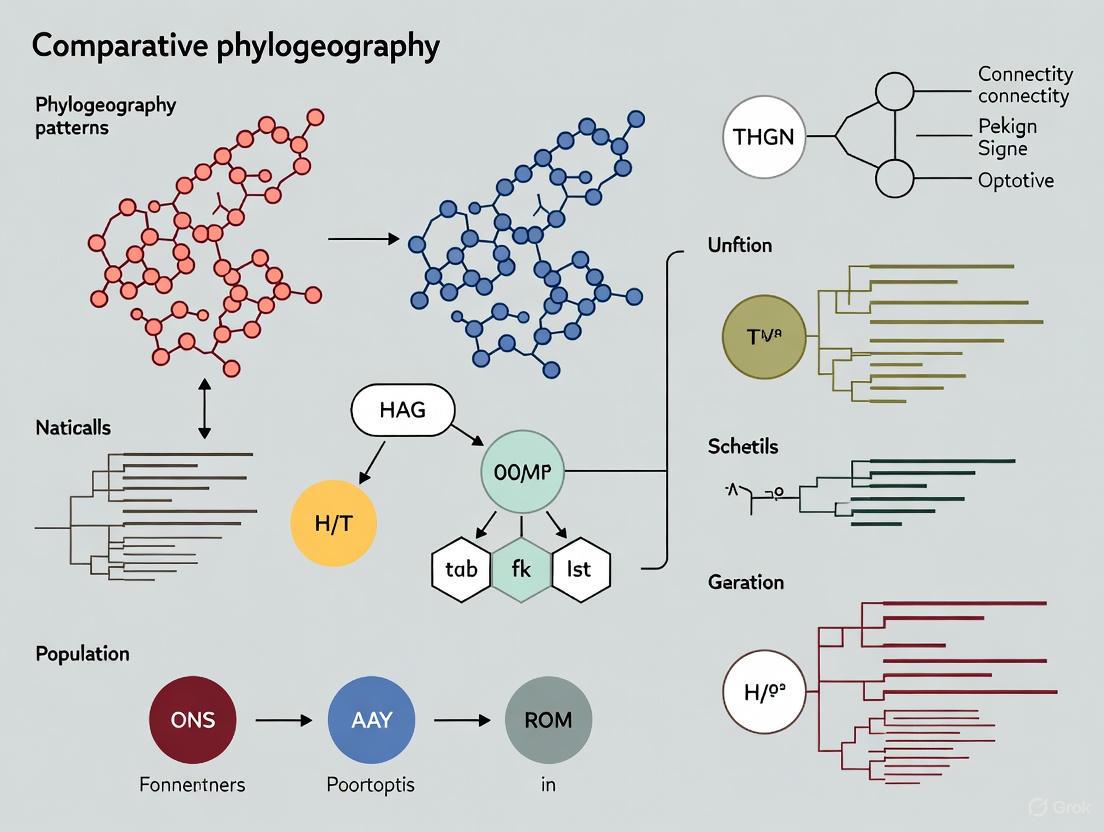

Comparative phylogeography tests hypotheses about the shared historical and ecological factors that influence the distribution of genetic variation across a community of species. The logical workflow for a comparative phylogeographic study, from data collection to inference, is outlined below.

Diagram 1: Workflow for a Comparative Phylogeography Study

3. Experimental Protocols in Practice

3.1. Case Study 1: Connectivity in Marine Copepods This study compared the phylogeography of two sibling species of marine copepod, Clausocalanus arcuicornis (cosmopolitan) and C. lividus (bi-antitropical), to understand the effects of biogeography on population connectivity [4].

- Methodology: A 465-base pair fragment of the mitochondrial Cytochrome Oxidase I (COI) gene was sequenced from 96 individuals of C. arcuicornis and 87 of C. lividus collected across the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans.

- Key Analyses:

- Molecular Diversity: Calculated haplotype diversity (Hd) and nucleotide diversity (π).

- Population Structure: Analyzed using Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) and pairwise FST.

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Gene trees were reconstructed using Maximum Parsimony.

- Results: C. arcuicornis showed a single panmictic population across its global range (low FST, high gene flow), whereas C. lividus exhibited clear genetic differentiation between Atlantic and Pacific populations, consistent with vicariance due to the rise of the Isthmus of Panama [4].

3.2. Case Study 2: Barriers in the Southern Caribbean This research evaluated the impact of two putative biogeographic barriers on three marine species with different Pelagic Larval Duration (PLD) [5].

- Methodology: A set of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) was generated for 15 individuals per species (Cittarium pica, PLD < 6 days; Acanthemblemaria rivasi, PLD < 22 days; Nerita tessellata, PLD > 60 days) across five locations using ddRad-seq.

- Key Analyses:

- Population Structure: Determined using AMOVA (ΦCT statistic) and clustering algorithms (e.g., ADMIXTURE) to identify the number of genetic populations (K).

- Mantel Test: Used to correlate genetic and geographic distance.

- Results: The Magdalena River plume caused a significant phylogeographic break for A. rivasi (ΦCT = 0.420). A second barrier (La Guajira upwelling) affected both A. rivasi (ΦCT = 0.406) and C. pica (ΦCT = 0.224). The species with the longest PLD, N. tessellata, showed no population structure (K=1), demonstrating how dispersal potential and barriers interact to shape connectivity [5].

Table 2: Summary of Key Findings from Case Studies

| Case Study | Biological Model | Key Experimental Factor | Major Finding | Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Copepods [4] | Clausocalanus arcuicornis vs. C. lividus | Species biogeography | Cosmopolitan species is panmictic; antitropical species shows ocean-basin vicariance. | Low FST and non-significant AMOVA for C. arcuicornis; significant Atlantic-Pacific split for C. lividus. |

| Southern Caribbean Marine Species [5] | A. rivasi, C. pica, N. tessellata | Pelagic Larval Duration (PLD) & biogeographic barriers | Phylogeographic breaks are strongest in species with shorter PLD. | Significant ΦCT values for short-PLD species at barriers; panmixia in long-PLD species. |

4. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for research in phylogenetics, population genetics, and phylogeography.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Genetics

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Standardized protocol for high-quality DNA extraction from diverse tissue samples, crucial for consistent downstream sequencing results [4]. |

| ddRAD-seq (Double Digest Restriction-site Associated DNA sequencing) | A reduced-representation genomics technique for discovering and genotyping thousands of SNPs across many individuals, ideal for population and phylogeographic studies [5]. |

| Mitochondrial COI gene | A standard molecular marker for DNA barcoding and phylogeographic studies due to its high mutation rate and utility for distinguishing closely related species and populations [4]. |

| Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) | A region of ribosomal DNA used as a genetic marker for phylogeography and species delimitation, especially in plants, fungi, and some invertebrates [6]. |

| SNP Panels | Genome-wide sets of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms used for high-resolution analysis of population structure, demographic history, and genotype-environment associations [7] [5]. |

| Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMM) | A statistical modeling framework used to analyze complex, nonlinear relationships, such as those between viral sharing probability and host phylogenetic similarity/geographic overlap [8]. |

5. Data Integration and Visualization of Inferred Connectivity

A primary output of phylogeographic analysis is the inference of historical migration routes and connectivity between geographic regions. These patterns can be visualized to summarize the conclusions of a study.

Diagram 2: Example of Inferred Phylogeographic Connectivity

Comparative phylogeography provides a powerful framework for disentangling the relative contributions of vicariance (the fragmentation of populations by emerging barriers) and dispersal (the movement of organisms across existing barriers) in shaping biodiversity patterns. By analyzing the phylogenetic relationships and geographic distributions of multiple, codistributed species, researchers can distinguish between community-wide evolutionary events and species-specific responses. When codistributed species exhibit congruent phylogeographic patterns—such as concordant genetic breaks at the same geographic barriers—this provides strong evidence for vicariance events affecting entire communities [9]. Conversely, incongruent phylogeographic patterns among species occupying the same landscape suggest that intrinsic biological differences, particularly dispersal capabilities and ecological specificity, have driven independent evolutionary trajectories [9] [3].

This methodological approach has transformed our understanding of how landscapes evolve and how species respond to geological and climatic changes. The core premise is straightforward: species with similar ecological requirements and dispersal limitations should show similar phylogeographic patterns if they were affected by the same historical vicariance events. The comparative approach controls for shared biogeographic history while revealing how species-specific traits mediate responses to common environmental changes [9]. This guide examines the experimental designs, analytical methods, and key findings from foundational studies in comparative phylogeography, providing researchers with a framework for investigating vicariance and dispersal in their study systems.

Theoretical Foundation: Vicariance vs. Dispersal Hypotheses

The vicariance-dispersal dichotomy represents a fundamental debate in biogeography. Vicariance biogeography emphasizes the role of emerging barriers—such as mountain uplift, river formation, or sea-level change—in splitting ancestral species distributions and promoting allopatric speciation [10]. In contrast, dispersal biogeography focuses on how organisms overcome preexisting barriers through active movement or passive transport, leading to range expansions and colonization of new territories [11]. In reality, most biogeographic patterns reflect complex interactions between both processes, with their relative importance varying across temporal and spatial scales.

Comparative phylogeography tests predictions derived from these competing hypotheses:

- The vicariance prediction expects codistributed species to exhibit congruent phylogeographic splits dating to approximately the same time period, corresponding to the emergence of a shared geographic barrier [9] [12].

- The dispersal prediction anticipates that phylogeographic patterns will reflect species-specific dispersal abilities and ecological tolerances, with highly vagile species showing weaker genetic structure across barriers than poor dispersers [9] [13].

The analytical power of comparative phylogeography comes from examining species with differing ecological characteristics but shared geographic distributions. This allows researchers to test whether physical barriers alone explain genetic divergence patterns, or whether biological traits modify how species respond to these barriers [9].

Table 1: Predictions of Vicariance vs. Dispersal Hypotheses in Comparative Phylogeography

| Analytical Feature | Vicariance Prediction | Dispersal Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogeographic concordance | High congruence across codistributed species | Incongruent patterns among species |

| Timing of divergence | Synchronous splits across multiple taxa | Variable divergence times |

| Relationship to barriers | Genetic breaks align with geographic features | Genetic patterns reflect dispersal routes |

| Effect of ecological traits | Minimal influence of species-specific traits | Strong trait-dependent patterns |

Experimental Approaches and Methodological Workflows

Research Design and Sampling Strategies

Robust comparative phylogeographic studies require careful research design with explicit a priori criteria for selecting codistributed species. The most informative comparisons involve species with contrasting ecological characteristics but overlapping geographic distributions across the landscape of interest. Ideal study systems include taxa with known differences in habitat specificity, dispersal capability, or degree of ecological association with particular environments [9].

A exemplary research design comes from a study of cave-dwelling springtails in the Salem Plateau of the Ozark Highlands [9]. Researchers selected two codistributed genera (Pygmarrhopalites and Pogonognathellus) with fundamentally different ecological relationships to cave habitats: one troglobiotic (obligate cave-dwellers with limited dispersal capability) and one eutroglophilic (facultative cave-dwellers capable of surface dispersal). This strategic selection of ecologically contrasting but geographically overlapping taxa enabled direct testing of how intrinsic ecological differences affect responses to the same extrinsic geographic barrier—the Mississippi River Valley [9].

Sampling designs should incorporate transects across major biogeographic barriers with sufficient geographic coverage to distinguish between continuous clines (suggesting isolation-by-distance) and discrete genetic breaks (suggesting vicariance). Replicate sampling of multiple individuals per location is essential for estimating population genetic parameters, with sample sizes typically ranging from 5-20 individuals per population depending on genetic diversity levels [9].

Molecular Methods and Genetic Marker Selection

Comparative phylogeography employs a range of molecular techniques, with marker selection dependent on the evolutionary timescale of interest and the genetic resolution required. The transition from Sanger sequencing of individual loci to high-throughput sequencing of complete genomes or reduced-representation libraries has dramatically increased phylogenetic resolution [3].

Table 2: Molecular Markers and Their Applications in Comparative Phylogeography

| Marker Type | Resolution Level | Applications | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial DNA | Population to species | Phylogeographic inference, demographic history | COI, cyt b [9] [14] |

| Nuclear genes | Species to genus | Species delimitation, phylogenetic relationships | 18S, 28S, ITS [14] |

| SNPs from genomic data | Population to subspecies | Fine-scale population structure, gene flow | RADseq, ultraconserved elements [10] |

| Complete organellar genomes | Deep phylogenetic scales | Ancient divergence events, lineage sorting | Chloroplast genomes [10] |

The springtail study employed both mitochondrial (COI, cyt b) and nuclear markers to assess evolutionary history, allowing comparison of locus-specific patterns and detection of potential discordance between gene trees [9]. For the red seaweed Pterocladiella, researchers sequenced two mitochondrial (COI-5P, cob) and three plastid (psaA, psbA, rbcL) markers to generate a robust, multi-locus phylogeny [15]. These complementary marker systems provide both rapidly evolving markers for population-level inferences and more conserved markers for deeper phylogenetic relationships.

Analytical Workflow for Data Interpretation

The analytical pipeline in comparative phylogeography integrates multiple computational approaches to test alternative biogeographic scenarios. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps from data collection to inference:

Diagram 1: Analytical workflow for comparative phylogeography studies

The analytical framework begins with population genetic analyses to quantify genetic structure and diversity, using methods like AMOVA, F-statistics, and clustering algorithms (e.g., STRUCTURE, PCA). These analyses determine how genetic variation is partitioned within and among populations across the potential barrier [9].

Next, phylogenetic reconstruction and divergence time estimation establish the evolutionary relationships and temporal framework for divergence events. Bayesian approaches like BEAST and MrBayes incorporate molecular clock models to estimate node ages, which can be calibrated with fossil evidence or known geological events [10] [14]. For example, in the Fraxinus study, researchers integrated fossil evidence with molecular dating to reconstruct the timing of intercontinental disjunctions [10].

Finally, explicit biogeographic models test alternative scenarios of vicariance versus dispersal. Software such as BioGeoBEARS and RASP implement likelihood-based frameworks for reconstructing ancestral ranges and estimating the relative support for different biogeographic processes [10] [12]. These models can quantify the number and direction of dispersal events and vicariance episodes through time.

Key Case Studies and Experimental Data

Cave Springtails Across the Mississippi River Valley

A seminal comparative study examined two genera of cave-dwelling springtails (Pygmarrhopalites and Pogonognathellus) across the Salem Plateau, a karst region bisected by the Mississippi River Valley [9]. This system provided an ideal natural experiment because the two taxa differed fundamentally in their ecological associations with caves: one was troglobiotic (highly cave-adapted) while the other was eutroglophilic (facultative cave-dweller).

The research employed mitochondrial and nuclear markers to assess population structure and divergence times. Quantitative analyses revealed strikingly different phylogeographic patterns: the troglobiotic Pygmarrhopalites showed deep genetic divergence across the Mississippi River Valley with estimated divergence times of 2.9-4.8 million years, corresponding to late Pliocene/early Pleistocene formation of the valley [9]. In contrast, the eutroglophilic Pogonognathellus exhibited minimal genetic structure across the same barrier, indicating ongoing dispersal capability.

Table 3: Comparative Phylogeographic Results for Cave Springtails [9]

| Parameter | Pygmarrhopalites (troglobiotic) | Pogonognathellus (eutroglophilic) |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic divergence across Mississippi River | Deep divergence (2.9-4.8 Ma) | Minimal genetic structure |

| Population connectivity | Highly structured, isolated populations | Panmictic populations across barrier |

| Primary evolutionary process | Vicariance | Contemporary dispersal |

| Interpretation | Barrier restricted dispersal | Dispersal across barrier maintained gene flow |

This clear contrast between ecologically distinct but codistributed species demonstrated that the same geographic barrier can have dramatically different effects depending on species-specific ecological traits. The study provided robust evidence that obligate cave association restricts dispersal across major barriers, leading to vicariant divergence, while facultative cave association permits ongoing dispersal [9].

Neotropical Forest Vipers and the Diagonal of Open/Dry Landscapes

Research on Neotropical forest vipers of the genus Bothrops investigated how the expansion of South America's "diagonal of open/dry landscapes" (DODL)—comprising the Chaco, Cerrado, and Caatinga ecoregions—influenced diversification [12]. The study tested the hypothesis that this arid corridor fragmented an ancient continuous forest into the modern Amazonian and Atlantic Forests, driving vicariant speciation in forest-adapted organisms.

Using a time-calibrated phylogeny and biogeographic modeling in BioGeoBEARS, researchers reconstructed ancestral ranges and compared alternative models of range evolution. Results supported two independent vicariance events in different Bothrops subclades, both resulting in disjunct Amazonian and Atlantic Forest distributions [12]. Divergence time estimates placed these events after the formation of the DODL, consistent with the vicariance hypothesis.

Dispersal analyses revealed limited movement between the Amazonian and Atlantic Forests, with most dispersal events occurring within each forest block rather than between them. This pattern supports the DODL as a persistent barrier to dispersal for forest vipers. The study exemplifies how comparative phylogeography can test specific geological hypotheses and reveal the historical processes underlying modern distribution patterns [12].

Cryptocercus Woodroaches and the Tectonic History

A global study of Cryptocercus woodroaches combined mitochondrial genomes and nuclear genes to reconstruct the group's biogeographic history across continents [14]. These wingless insects with low vagility exhibit a classic disjunct distribution across eastern and western North America, China, South Korea, and the Russian Far East, making them ideal for testing vicariance versus dispersal scenarios.

Phylogenetic analyses strongly supported six major lineages with clear geographic patterning. Molecular dating with Bayesian methods estimated that the initial divergence between American and Asian lineages occurred approximately 80.5 million years ago, consistent with continental separation through plate tectonics [14]. Statistical dispersal-vicariance analysis identified two key dispersal events and six vicariance events shaping the global distribution pattern.

This research demonstrated how both processes operate at different temporal and spatial scales: deep vicariance events corresponded to continental fragmentation, while more recent dispersal events explained distribution patterns within continents. The study highlighted the value of combining multiple genetic markers with explicit biogeographic modeling to disentangle complex histories [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful comparative phylogeography requires specialized methodological tools and analytical resources. The following table summarizes key solutions and their applications in vicariance and dispersal research:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Phylogeography

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Application in Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Reagents | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | DNA extraction from various tissue types | Efficient purification, minimal inhibitors |

| PCR Master Mix | Amplification of target loci | Consistent performance across taxa | |

| BigDye Terminator v3.1 | Sanger sequencing | High-quality sequence data | |

| Molecular Markers | Mitochondrial primers (COI, cyt b) | Population-level phylogenetics | Universal primers available |

| Nuclear ribosomal primers (18S, 28S) | Higher-level phylogenetics | Conserved across diverse taxa | |

| Ultra-conserved elements | Phylogenomics at multiple scales | Thousands of loci from reduced-representation libraries | |

| Analytical Software | BEAST2 | Bayesian phylogenetic analysis | Molecular dating, demographic history |

| BioGeoBEARS | Biogeographic model testing | Compares multiple dispersal models | |

| STRUCTURE/PCA | Population structure analysis | Identifies genetic clusters | |

| Reference Databases | GenBank | Sequence comparison and verification | Curated repository with global coverage |

| TimeTree | Divergence time priors | Synthesis of molecular time estimates |

Comparative phylogeography has emerged as an indispensable approach for distinguishing vicariance from dispersal in evolutionary biology. The case studies presented here demonstrate that neither process operates exclusively; rather, most systems reflect a complex interplay of both, with their relative importance determined by the interaction between species-specific traits and landscape history [9] [12].

Key insights from this research include:

- Vicariance predominates when major geographic barriers affect species with limited dispersal capabilities, creating congruent phylogeographic patterns across codistributed taxa [9] [12].

- Dispersal processes create more idiosyncratic patterns that reflect species-specific ecological characteristics, particularly dispersal mechanism and habitat specificity [9] [13].

- The timing of divergence events provides critical evidence for correlating genetic splits with known geological or climatic events [9] [10].

- Comparative analysis of ecologically contrasting but geographically overlapping species offers the most powerful design for testing alternative biogeographic scenarios [9].

Future advances in comparative phylogeography will come from genomic-scale datasets that provide finer resolution of population relationships, integrated modeling approaches that jointly estimate demographic and biogeographic history, and expanded temporal perspectives incorporating ancient DNA and paleoenvironmental reconstructions. These methodological innovations will further enhance our ability to reconstruct the historical processes that have shaped modern biodiversity patterns across the tree of life.

The field of comparative phylogeography has undergone a profound transformation with the advent of advanced genomic sequencing technologies. Where studies once relied on short mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) markers such as COI or the control region, researchers can now leverage complete mitochondrial genomes and whole genomic data to unravel connectivity patterns with unprecedented clarity. This revolution in genetic resolution is illuminating previously cryptic species boundaries, fine-scale population structures, and complex evolutionary histories that were undetectable with traditional methods.

Mitochondrial DNA has long been a workhorse for phylogeographic studies due to its maternal inheritance, lack of recombination, and relatively high mutation rate. However, the limited informational content of short mtDNA fragments (typically 400-800 bp) often results in insufficient variation to distinguish recently diverged lineages or resolve fine-scale population structure, particularly in cases where common haplotypes are widespread across geographic regions [16]. The genomic revolution addresses these limitations by providing orders of magnitude more data, enabling researchers to detect subtle genetic differences that inform our understanding of connectivity, dispersal barriers, and demographic history across ecosystems.

Comparative Analysis: Resolution Across Genomic Scales

The enhanced resolution provided by different genomic approaches can be quantitatively compared across multiple performance metrics, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Genetic Approaches for Phylogeographic Connectivity Studies

| Metric | Short mtDNA Markers | Whole mtDNA Genomes | Whole Genomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Sequence Length | 400-800 bp [16] | 16-18 kb (animals) [17] | >1 Gb (varies by species) |

| Informational Sites | Limited (dozens) | Moderate (hundreds) | Extensive (millions) |

| Ability to Detect Cryptic Structure | Low | Moderate to High [16] | Very High |

| Cost per Sample | $ | $$ | $$$ |

| Computational Requirements | Low | Moderate | High |

| Sample Degradation Tolerance | Moderate | Moderate (with MitoCOMON) [17] | Low |

| NUMT Interference Risk | Variable | Manageable with probe selection [18] | Controlled through mapping |

| Representative Applications | Species barcoding, preliminary screening | Fine-scale population structure, mixed stock analysis [16] | Demographic history, selection, local adaptation |

The transition from short markers to complete mitogenomes represents a significant leap in data content. For example, a study on Pacific green turtles (Chelonia mydas) demonstrated that while traditional control region sequencing (770 bp) failed to differentiate between rookeries in Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), whole mitogenome sequencing revealed significant genetic differentiation, enabling more precise conservation management [16]. This case exemplifies how enhanced resolution can transform our understanding of population connectivity.

Methodological Approaches: From Primer Design to Probe Selection

PCR-Based Whole mtDNA Sequencing

The MitoCOMON method addresses key limitations in mitochondrial sequencing by amplifying the entire mitochondrial genome as four overlapping fragments (4-8 kb each), making it applicable to a wide range of species within a taxonomic clade and tolerant of partially degraded DNA [17]. The primer design strategy for this approach involves:

Sequence Collection and Alignment: Downloading complete mtDNA sequences for the target clade (e.g., mammals, birds) from RefSeq and aligning them using MAFFT with default parameters [17].

Conserved Region Identification: Calculating information content across the alignment using a 20 bp sliding window and selecting regions with an average information content higher than 1.80 as candidate primer sites [17].

Primer Specificity Validation: Testing candidate primers against both target and non-target mtDNA sequences using PrimerProspector, selecting primers with a target clade match ratio >0.85 and non-target ratio <0.15 [17].

This method has demonstrated a high success rate for whole mtDNA sequencing across multiple mammal and bird species, even enabling assembly of multiple whole mitochondrial sequences from mixed-species samples without forming chimeric sequences [17].

Capture-Based Enrichment Strategies

Hybridization capture represents an alternative approach for mitochondrial enrichment, particularly valuable for degraded samples or when targeting multiple genomes simultaneously. A systematic comparison of DNA and RNA probes revealed significant performance differences:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of DNA vs. RNA Probes for Capture-Based mtDNA Sequencing

| Parameter | DNA Probes | RNA Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Probe Quantity | 16 ng (tissue), 10 ng (plasma) per 500 ng library [18] | 5 ng (tissue), 6 ng (plasma) per 500 ng library [18] |

| Optimal Hybridization Temperature | 60°C (tissue), 55°C (plasma) [18] | 55°C (tissue), 60°C (plasma) [18] |

| mtDNA Enrichment Efficiency | Moderate (61.79% mapping rate in tissue) [18] | High (92.55% mapping rate in tissue) [18] |

| NUMT Suppression | Superior [18] | Moderate |

| Fragment Size Representation | Standard distribution | Broader distribution, better long fragment retention [18] |

| Best Application | Mutation detection requiring minimal artifacts [18] | High-sensitivity detection, fragmentomic analysis [18] |

The wet laboratory workflow for capture-based mtDNA sequencing follows a standardized protocol:

Library Preparation: Extract genomic DNA from fresh tissue or plasma samples and fragment using focused ultrasonication to 300-500 bp fragments [18].

Library Construction: Prepare whole genome sequencing libraries using standard kits with appropriate adapters [18].

Hybridization Capture: Incubate libraries with custom-designed DNA or RNA probes under optimized temperature and quantity conditions [18].

Post-Capture Amplification: Enrich captured libraries through PCR amplification before sequencing [18].

This approach has been successfully applied to various sample types, including fresh frozen tissue and plasma circulating cell-free DNA, demonstrating its versatility across research and diagnostic applications [18].

Experimental Workflows: From Sample to Analysis

The journey from biological sample to phylogeographic insight involves multiple critical steps, with workflow decisions significantly impacting the final resolution. The following diagram illustrates two primary pathways for obtaining whole mitochondrial genome data:

Diagram 1: Whole mtDNA Sequencing Workflow Comparison

The experimental pathway selection depends on research goals, sample quality, and available resources. The PCR-based approach (e.g., MitoCOMON) offers advantages for wide taxonomic applications without species-specific primer design, while capture methods provide superior performance for fragmented DNA [17] [18].

Case Studies: Enhanced Resolution in Practice

Marine Turtle Conservation Genetics

The power of whole mitogenome sequencing is strikingly demonstrated in marine turtle conservation. Research on Pacific green turtles revealed that traditional control region sequencing (770 bp) failed to differentiate populations in Guam and CNMI, despite their separation by significant geographic distance. Whole mitogenome sequencing, however, detected significant genetic differentiation between these rookeries, enabling more accurate Mixed Stock Analysis (MSA) and revealing previously cryptic population structure [16]. This enhanced resolution directly impacts conservation strategies by allowing managers to identify distinct management units and precisely attribute foraging aggregates to their natal rookeries.

Seaweed Phylogeography and Incipient Speciation

Comparative phylogeography of incipient seaweed species (Sargassum polycystum and S. plagiophyllum) around the Thai-Malay Peninsula illustrates how multi-locus mitochondrial data (cox1, cox3) enhances resolution of recent evolutionary processes. The study revealed that these morphologically distinct species diverged from their most recent common ancestor approximately 0.17 million years ago, followed by demographic expansion around 0.015-0.060 million years ago [19]. Mitochondrial datasets showed much higher phylogeographic diversity in S. polycystum than in S. plagiophyllum, providing insights into how late Quaternary sea-level fluctuations and contemporary oceanic currents shaped population genetic structuring [19]. This level of resolution would be challenging to achieve with single short mtDNA markers.

Population Connectivity of Reef Fishes

Research on the golden hind grouper (Cephalopholis aurantia) in the Spratly Islands employed the mitochondrial COI gene to assess genetic diversity and population connectivity [20]. While this approach revealed high haplotype diversity with low nucleotide diversity—suggesting post-bottleneck demographic expansion—the limited resolution of a single gene fragment constrained precise population structure assessment. The study noted that larval dispersal capabilities and oceanic currents facilitate gene flow, but a whole mitogenome approach would provide finer-scale resolution of connectivity patterns crucial for spatially explicit management of this economically important species [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Mitochondrial Genomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Range PCR Enzyme Mixes | Amplification of large mtDNA fragments (4-8 kb) | Essential for MitoCOMON approach; higher fidelity reduces artifacts [17] |

| Custom DNA/RNA Probes | Target enrichment in capture-based approaches | RNA probes offer higher efficiency; DNA probes better suppress NUMTs [18] |

| Biotin-Streptavidin Magnetic Beads | Recovery of probe-hybridized targets | Critical for post-hybridization purification in capture methods [18] |

| tRNAscan-SE | tRNA gene identification in mtDNA assemblies | Crucial for accurate annotation of mitochondrial genomes [17] |

| MAFFT Software | Multiple sequence alignment | Aligns mtDNA sequences for conserved region identification [17] |

| Primer3 with Custom Modifications | Primer design for conserved regions | Enables design of clade-specific primers [17] |

| Mitochondrial Assembly Pipelines | De novo assembly of mitogenomes | Specialized tools account for repetitive regions and structural variants [17] |

| NUMT Filtering Scripts | Identification and removal of nuclear mtDNA segments | Critical for accurate variant calling in capture-based data [18] |

The genomic revolution has fundamentally transformed our approach to understanding connectivity patterns in comparative phylogeography. While short mtDNA markers remain valuable for initial surveys and species identification, whole mitogenome sequencing provides substantially improved resolution for fine-scale population structure, mixed stock analysis, and understanding recent evolutionary processes. The choice between PCR-based and capture-based approaches depends on specific research questions, sample quality, and resources, with each method offering distinct advantages.

As sequencing technologies continue to advance and computational tools become more sophisticated, the integration of complete mitochondrial genomes with nuclear genomic data will further enhance our ability to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships, elucidate demographic histories, and inform conservation strategies across diverse taxa. This enhanced resolution is particularly crucial in an era of rapid environmental change, where understanding population connectivity and adaptive potential is essential for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management.

The field of comparative phylogeography has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from initial applications of molecular genetics to recognize and conserve endangered species into a sophisticated discipline capable of reconstructing deep-time biogeographic histories and forecasting ecological change. This journey began with the pioneering work of John C. Avise, who in the late 1980s championed the role of molecular genetics in revealing phylogenetic distinctions that morphological traits alone often missed [21]. His insights established that conservation efforts could be misdirected without understanding true biological diversity at the genetic level. Today, this foundation supports global biotic analyses that integrate vast genomic datasets with environmental variables to reveal patterns of diversification, dispersal, and ecological adaptation across continents and evolutionary timescales.

The evolution of this field reflects technological advancement and a conceptual shift toward understanding connectivity patterns across landscapes and through deep time. Modern research has illuminated how the reciprocal relationship between climate space occupancy (niche) and biogeographic distribution (biotope)—known as Hutchinson's duality—enables scientists to infer ancestral climatic tolerances and dispersal routes even through spatial gaps in the fossil record [22]. This review examines key methodological progress from Avise's early work to contemporary global analyses, providing researchers with experimental protocols, visualization frameworks, and reagent solutions essential for advancing comparative phylogeography.

Methodological Evolution: From Allozymes to Whole Genomes

The Pioneering Era: Molecular Genetics in Conservation

Avise's early work demonstrated how molecular markers could correct systematic errors in conservation prioritization. His approach identified two critical types of taxonomic errors: recognizing groups that showed little evolutionary differentiation, and failing to recognize phylogenetically distinct forms [21]. This molecular approach provided an evidence-based framework for protecting biological diversity rather than morphological variants. Early methodologies relied on protein electrophoresis and mitochondrial DNA analysis, which offered initial insights into population structure and species boundaries but limited resolution for fine-scale genetic analysis.

Table 1: Evolution of Molecular Tools in Phylogeography

| Era | Primary Technologies | Typical Genetic Markers | Scale of Analysis | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980s-1990s (Pioneering) | Protein electrophoresis, Mitochondrial DNA restriction analysis, Early PCR | Allozymes, mtDNA RFLPs, microsatellites | Population to species level | Limited genomic coverage, low resolution for recent divergence |

| 2000s-2010s (Expansion) | Sanger sequencing, Fragment analysis, SNP arrays | mtDNA sequences, nDNA sequences, microsatellites, targeted SNPs | Multi-species communities to regional scales | Cost prohibitive for genome-scale data, inconsistent markers across taxa |

| 2010s-Present (Genomic) | Whole genome sequencing, Reduced representation sequencing, HyRAD | Genome-wide SNPs, structural variants, entire organellar genomes | Cross-taxa biogeographic regions to global scales | Computational challenges, data integration across platforms |

Contemporary Genomic Approaches

Modern comparative phylogeography leverages whole genome techniques to evaluate spatial genetic differentiation at unprecedented resolution across co-distributed species [23]. This approach has revealed conserved patterns, such as the genetic distinctness of Appalachian populations from boreal belt populations in 11 of 12 migratory bird species studied, despite high dispersal capability [23]. Current methods utilize hundreds to thousands of genome-wide markers to simultaneously assess neutral structure and adaptive variation, enabling researchers to distinguish between historical demographic processes and contemporary selective pressures.

The scale of modern analyses is exemplified by recent studies sequencing over 900 low-coverage whole genomes to evaluate concordance of genetic structure across multiple species [23]. This computational framework allows for testing hypotheses about shared biogeographic histories versus species-specific responses to environmental barriers. Furthermore, genomic data now facilitates the detection of molecular parallelism—identifying whether the same genomic regions drive genetic differentiation across multiple species, which would suggest parallel adaptation to shared environmental drivers [23].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Contemporary Phylogeography

Landscape-Explicit Phylogeographic Reconstruction

A groundbreaking methodological advancement is the TARDIS (Terrains and Routes Directed in Space-time) framework, which couples Bayesian phylogeographic inference with landscape connectivity analysis [22]. This approach reconstructs dispersal routes between ancestor and descendant locations as least-cost paths through spatially explicit paleogeographic representations. The protocol involves:

Time-Calibrated Phylogenetic Framework: Establish a robust, time-calibrated phylogeny using fossil data and molecular clock methods. For archosauromorph reptiles, this involved resolving previously unstable relationships through Bayesian inference with fossil-derived calibration points [22].

Ancestral Geographic Estimation: Implement the geographic model in BayesTraits or similar software to estimate point-wise ancestral geographic origins using likelihood or Bayesian approaches.

Spatiotemporal Graph Construction: Represent paleogeographic surfaces as flexibly weighted spatiotemporal graphs incorporating changing topography and continental configurations through time.

Least-Cost Pathway Calculation: Estimate dispersal routes between ancestor-descendant locations as least-cost paths through the spatiotemporal graph, weighted to penalize travel through regions with climatic conditions deviating from known ancestral and descendant locations.

Climate Space Occupancy Measurement: Extract environmental conditions along dispersal pathways using paleoclimate models to infer the breadth of climatic conditions lineages must have tolerated during dispersal, including through spatial gaps in the fossil record [22].

This methodology transformed inaccessible portions of biogeographic history into quantifiable climate space occupancy data, revealing previously unknown ecological adaptations in early archosauromorphs.

Comparative Whole Genome Phylogeography

Protocol for multi-species genomic analysis as implemented in contemporary studies [23]:

Comprehensive Tissue Sampling: Collect tissue samples across the target biogeographic regions for all study species. Modern studies typically include sampling spanning entire distribution ranges with particular attention to potential contact zones and peripheral populations.

Whole Genome Sequencing: Perform low-coverage whole genome sequencing (typically 1-5x coverage) sufficient for variant calling while enabling cost-effective processing of hundreds of individuals.

Variant Calling and Filtering: Map reads to reference genomes (when available) or perform de novo assembly followed by SNP calling using standardized pipelines like GATK or SAMtools. Implement quality filters for minimum mapping quality, read depth, and missing data.

Population Genetic Analysis: Conduct hierarchical population structure analysis using ADMIXTURE, fineRADstructure, or similar approaches. Calculate FST and related differentiation metrics between identified populations.

Diversity Assessment: Estimate standard population genetic diversity metrics (π, θw, heterozygosity) within and between populations to test alternative hypotheses about historical demography.

Genomic Differentiation Context: Evaluate whether genetic differentiation is distributed diffusely across the genome (suggesting neutral processes) or shows strong peaks (suggesting local adaptation) using window-based analyses of FST and diversity metrics.

Cross-Species Comparison: Implement generalized linear models or matrix correlation tests to evaluate concordance in spatial genetic patterns across co-distributed species, accounting for phylogenetic non-independence.

This protocol enabled the discovery that Appalachian populations of migratory birds consistently harbor subtly distinct genetic diversity from widespread boreal populations, informing conservation prioritization for these genetically unique populations [23].

Key Analytical Frameworks and Visualization

Signaling Pathways and Analytical Workflows

The transition from localized phylogenetic studies to global biotic analyses requires integrated workflows that connect molecular data with spatial and environmental information. The following diagram illustrates this analytical pathway:

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for comparative phylogeography analysis, showing the convergence of molecular and spatial data streams toward synthetic interpretation.

Landscape Connectivity Analysis Framework

The TARDIS framework for reconstructing deep-time dispersal routes integrates phylogenetic and paleogeographic data through the following logical structure:

Figure 2: Logical framework for landscape-explicit phylogeography, showing how dispersal routes and environmental tolerances are inferred through integration of phylogenetic and paleoenvironmental data.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Contemporary comparative phylogeography requires specialized reagents and computational tools to generate and analyze genome-scale data across multiple species. The following table details essential solutions for implementing the protocols described in this review.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Phylogeography

| Category | Specific Solution | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction & Library Prep | Tissue lysis buffers with proteinase K | Efficient cell lysis and protein digestion for diverse specimen types | Extraction from museum specimens, feathers, non-invasive samples |

| High-fidelity PCR master mixes | Target enrichment and library amplification with minimal errors | Amplification of ultraconserved elements, targeted sequencing | |

| Tagmentation enzymes (Tn5) | Rapid library preparation for whole genome sequencing | Illumina Nextera-based WGS library prep | |

| Sequence Capture | MYbaits custom RNA baits | Target enrichment for phylogenomic markers across divergent taxa | Cross-species capture of UCEs, exons, mitochondrial genomes |

| HyRAD hybridization probes | Genome reduction for degraded DNA from historical specimens | Museomics, inclusion of type specimens in phylogenetic matrices | |

| Bioinformatics | GATK variant callers | SNP and indel discovery across multiple genomes | Population genomic analysis, detection of structural variants |

| IQ-TREE maximum likelihood software | Phylogenetic inference with model selection | Species tree estimation, divergence dating with fossil calibrations | |

| BEAST2 Bayesian framework | Co-estimation of phylogeny and divergence times | Historical biogeographic reconstruction, ancestral state estimation | |

| Geospatial Analysis | PaleoDEM reconstruction tools | Digital elevation models for past land configurations | Landscape-explicit dispersal modeling in frameworks like TARDIS |

| GDAL/OGR geospatial libraries | Processing and transformation of spatial data layers | Conversion between coordinate systems, raster analysis | |

| Visualization | ggplot2 R package | Publication-quality graphics for data visualization | Creating multi-panel figures showing genetic and spatial data |

| QGIS open-source GIS | Spatial data management and map production | Study region maps, sampling locality visualization |

Data Synthesis and Comparative Analysis

Global Diversity Patterns Across Taxa

Modern comparative approaches have revealed fundamental principles governing global diversity patterns. Analysis of 10,213 squamate species demonstrated that large-scale diversity patterns are best explained by deep-time diversification rates and historical occupation rather than recent diversification or climate alone [24]. This research resolved the paradoxical finding that recent diversification rates can be higher in species-poor high-latitude regions, while overall richness patterns reflect accumulation over longer timescales in tropical regions.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Diversity Pattern Drivers Across Major Taxa

| Taxonomic Group | Primary Richness Gradient | Key Historical Driver | Climate Relationship | Deep-time vs. Recent Diversification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squamates (lizards, snakes) | Higher in tropics | Ancient tropical occupation, not current climate | Present but not primary driver | Deep-time rates predict richness; recent rates do not [24] |

| Fabaceae (legumes) | Maximal in seasonally dry tropics | Temperature seasonality, elevation range | Annual mean temperature, precipitation seasonality | Tropical conservatism hypothesis supported [25] |

| Archosauromorphs (fossil reptiles) | Pangaean distribution | Dispersal through climatic barriers | Remarkable climatic adversity tolerance | Early Triassic peak in climatic disparity [22] |

| Boreal Birds | Latitudinal gradient | Historic refugia, not contemporary population size | Secondary to biogeographic history | Appalachian distinctness despite gene flow [23] |

Methodological Comparisons and Best Practices

The evolution of phylogeographic methods has created distinct best practices for different research questions. Early protein electrophoresis provided species-level distinctions but lacked resolution for population-level questions. Contemporary whole-genome approaches enable researchers to distinguish between neutral demographic history and adaptive evolution, providing unprecedented insight into the mechanisms generating and maintaining biodiversity.

Future methodological development should focus on integrating across taxonomic scales, as exemplified by the BMD (Biodiversity Meets Data) project, which aims to create single access points for biodiversity monitoring tools, analyses, and data to support evidence-based conservation [26]. Such initiatives represent the next evolutionary stage in Avise's original vision—transforming biodiversity data into actionable insights through standardized protocols and shared analytical frameworks.

The trajectory from Avise's pioneering advocacy for molecular genetics in conservation to contemporary global biotic analyses represents a paradigm shift in how we understand and document biodiversity. What began as a tool for correcting taxonomic misclassifications has matured into an integrative discipline that bridges genomics, paleontology, climatology, and spatial analysis. This evolution has revealed that global diversity patterns are predominantly shaped by deep-time processes—ancient diversification rates and historical biogeographic occupation—rather than contemporary climate or recent evolutionary dynamics alone [24].

The future of comparative phylogeography lies in further integration across biological scales—from genomes to ecosystems—and temporal ranges—from deep-time fossil records to contemporary environmental responses. Emerging frameworks like the TARDIS model for landscape-explicit historical biogeography [22] and the BMD project for biodiversity data integration [26] point toward increasingly sophisticated approaches that will continue to transform our understanding of biodiversity's origin, distribution, and conservation needs. As the field progresses, it remains grounded in Avise's fundamental insight: accurate recognition of evolutionary diversity is essential for effective conservation and meaningful understanding of life's history.

Comparative Analysis of Phylogeographic Breaks, Refugia, and Demographic History

Experimental Approaches and Molecular Marker Selection

The choice of molecular markers and analytical methods is critical in phylogeographic studies, as it directly influences the detection of genetic breaks, demographic history, and refugia. Different markers, due to their modes of inheritance and rates of evolution, can yield contrasting insights.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Markers Used in Phylogeographic Studies

| Study System | Nuclear Markers (Type & Number) | Organelle Markers (Type & Number) | Key Finding on Marker Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Populus lasiocarpa (Around Sichuan Basin) [27] | 8 nSSRs (Microsatellites) | 3 ptDNA (Plastid) fragments | nSSRs revealed three genetic groups aligned with phylogeographic breaks; ptDNA patterns were blurred, likely due to wind-dispersed seeds [27]. |

| Populus rotundifolia (Hengduan Mountains) [28] | 14 nSSRs (Microsatellites) | 4 cpDNA (Chloroplast) fragments | nSSRs showed admixture and gene flow across breaks; cpDNA provided complementary historical perspectives [28]. |

| Sargassum Seaweeds (Thai-Malay Peninsula) [29] | ITS2 (Nuclear Ribosomal DNA) | cox1 & cox3 (Mitochondrial DNA) | Mitochondrial datasets revealed much higher phylogeographic diversity in S. polycystum than in S. plagiophyllum [29]. |

| Intertidal Mites (Japanese Islands) [30] | --- | COI (Mitochondrial DNA) | Genetic structure indicated long periods of isolation followed by recent expansion and gene flow, showing high dispersal potential [30]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

A summary of the core methodologies employed in the cited studies provides a protocol for conducting comparative phylogeographic analyses.

Population Genetics and Phylogeographic Workflow

The following diagram outlines the general workflow for a phylogeographic study, from data collection to inference.

Key Methodological Steps

- Sample Collection and DNA Sequencing: Studies collected individual samples from multiple populations across the species' range. For Populus lasiocarpa, 265 individuals from 21 populations were sequenced [27]. Total genomic DNA is extracted, and specific markers (e.g., nSSRs, cpDNA, mtDNA) are amplified via PCR and sequenced.

- Genetic Data Analysis:

- Population Structure: Analyzed using programs like STRUCTURE for nSSRs to identify genetic clusters (K) and analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) to partition genetic variation [27] [28].

- Phylogenetic Analysis and Haplotype Networks: Chloroplast and mitochondrial sequences are used to construct haplotype networks (e.g., with TCS) or phylogenetic trees (e.g., with MrBayes, BEAST) to visualize maternal lineages and relationships [29] [30].

- Demographic History: Multiple methods are used.

- Species Distribution Modeling (SDM): Projected onto paleo-climate models to infer potential range shifts since the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) [27] [28].

- DIYABC (Approximate Bayesian Computation): Used to test alternative demographic scenarios (e.g., population expansion vs. contraction) and estimate parameters like divergence times [27] [29].

- Mismatch Distribution Analysis: Assessed whether populations have experienced recent expansion.

- Testing for Phylogeographic Breaks: The spatial distribution of genetic clusters (from nSSRs) and haplotypes (from organelle DNA) are mapped against known geographic barriers (e.g., the Sichuan Basin, Tanaka-Kaiyong Line) to evaluate their strength as gene flow barriers [27] [28].

Quantitative Data on Phylogeographic Patterns

Synthesized data from case studies allows for a direct comparison of how different organisms respond to geographic and climatic forces.

Table 2: Comparative Phylogeographic Patterns Across Taxa and Regions

| Study System & Region | Identified Phylogeographic Break(s) & Refugia | Inferred Demographic History | Major Drivers Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Populus lasiocarpa (Tree, Wind-dispersed) [27] | Breaks: Sichuan Basin, Kaiyong Line, 105°E line.Groups: Eastern, Southern, Western. | Larger potential LGM distribution; severe bottleneck during last interglacial; population contraction/expansion inferred (DIYABC). | Topographic barriers, biological traits (wind dispersal), Quaternary climate oscillations. |

| Sargassum spp. (Seaweeds, Ocean-dispersed) [29] | Refugia: Andaman Sea (S. plagiophyllum), northern Malacca Strait (S. polycystum). | Divergence from common ancestor ~0.17 Mya; demographic expansion ~0.015–0.060 Mya. | Late Quaternary sea-level fluctuations, contemporary oceanic currents. |

| Populus rotundifolia (Tree, Wind-dispersed) [28] | Breaks: Mekong-Salween Divide, Tanaka-Kaiyong Line.Groups: Western, Central, Eastern. | Range expansion since LGM; major population expansion ~600,000 years ago. | Wind patterns, topographic barriers (Hengduan Mountains), niche differentiation. |

| Fortuynia spp. (Mites, Passive-dispersed) [30] | Break: Tokara Strait.Divergence: F. shibai & F. churaumi ~3 Ma. | Long isolation followed by recent expansion and gene flow during Pleistocene low sea levels. | Paleoclimatic events, geological history (island formation), ocean currents. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table details key reagents, software, and databases essential for conducting phylogeographic research, as utilized or implied by the reviewed studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Phylogeography

| Item Name | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Standard Molecular Biology Kits | DNA extraction, purification, and PCR amplification from various tissue types (leaves, algal blades, whole mites). |

| Universal Primers | For amplifying standard phylogenetic markers (e.g., cox1 for animals/seaweeds, trnL-F for plants, ITS for fungi/plants). |

| Fluorescently-Labeled Primers | Essential for genotyping nuclear microsatellite (nSSR) markers using capillary electrophoresis. |

| dNTPs, Taq Polymerase, Buffer | Core components of PCR master mixes for amplifying target DNA regions. |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | For generating high-quality sequence data for phylogenetic and haplotype analysis. |

| BEAST / BEAST2 | Software for Bayesian phylogenetic analysis, molecular dating, and continuous phylogeographic inference [31]. |

| STRUCTURE / fastStructure | Software for inferring population structure and assigning individuals to genetic clusters using multilocus genotype data [27]. |

| DIYABC | Software for Approximate Bayesian Computation to test demographic scenarios and estimate historical parameters [27] [29]. |

| EvoLaps / PhyloScape | Web-based applications for visualizing and editing phylogeographic scenarios and phylogenetic trees [31] [32]. |

| WorldClim Paleo-Climate Data | Database of past climate layers for use in Species Distribution Modeling (SDM) to reconstruct past potential ranges [27] [28]. |

From Theory to Practice: Genomic Tools and Cutting-Edge Applications in Disease and Drug Discovery

This guide objectively compares the performance of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), nuclear markers, and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) in molecular research, with a specific focus on applications in comparative phylogeography and population connectivity studies.

Molecular methods offer distinct advantages and limitations for genotyping, variant detection, and phylogenetic inference.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Molecular Methods

| Feature | mtDNA-Targeted Sequencing | Nuclear Markers | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Maternal lineage tracing, degraded samples, population genetics [33] [34] | Population structure, phylogenetic analysis, gene flow studies [35] | Comprehensive variant discovery, nuclear and mitochondrial genome analysis [36] [37] |

| Variant Detection Scope | Entire mitochondrial genome (16,569 bp) [36] | Selected nuclear loci [35] | Genome-wide nuclear and mitochondrial variants [37] [38] |

| Heteroplasmy Detection | Accurate for >95% and <5% AAF; variable for low-frequency [36] | Not applicable | Calls more heteroplasmies than targeted methods; variable for low-frequency [36] [39] |

| Cost & Throughput | Affordable for large cohorts; lower cost than WGS [36] [39] | Varies by method (singleplex to multiplex) | Higher cost and time-consuming for large sample sizes [36] [37] |

| Typical Read Depth | Very high (e.g., median ~95,000x) [36] | Varies by method | Lower for mtDNA (e.g., median ~1,176x) unless enriched [36] |

| Data Output | ~30 GB raw data (for a human genome) [37] | Varies by method and scale | ~30 GB raw data (for a human genome) [37] |

| Key Advantage | High sensitivity for mtDNA variants; ideal for low-quality DNA [33] | Independent, recombining markers; avoids linked gene history [35] [38] | Single comprehensive test for nuclear and mitochondrial genomes [37] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed methodologies are critical for interpreting performance data and reproducing results.

mtDNA-Targeted Sequencing Protocol

A robust protocol for mtDNA whole-genome sequencing on a DNA nanoball (DNB) platform illustrates a modern targeted approach [33] [34]:

- DNA Preparation: 20 ng DNA is digested with enzymes (e.g., Exonuclease V, DraIII, PshAI, XmaI) at 37°C for 4 hours to enrich for mtDNA.

- Whole Genome Amplification: The mitochondrial genome is amplified using a REPLI-g mitochondrial DNA kit (QIAGEN) for 8 hours or overnight.

- Library Preparation: 2 ng of the mtDNA-enriched sample is used for Nextera XT DNA library preparation with 384-plex dual index barcoding (Illumina).

- Sequencing: Pooled libraries are sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq or DNBSEQ platform with paired-end reads (151 bp).

Whole Genome Sequencing Protocol

A standardized WGS workflow for clinical germline analysis provides a comparison point [37]:

- Library Preparation: DNA (e.g., 500 ng) is prepared using a PCR-free library kit (e.g., Kappa Hyper Library Preparation Kit).

- Sequencing: Libraries are sequenced on a platform like the Illumina HiSeq X with paired-end reads (150 bp).

- Bioinformatics: Raw data is aligned to a reference genome (e.g., rCRS for mtDNA) using BWA. Variants are called using specialized tools (e.g., MitoCaller for mtDNA, GATK for nuclear variants).

Nuclear Marker Selection and Analysis

For phylogenetic studies, nuclear markers are selected based on availability and evolutionary rate [35]:

- Gene Selection: Markers are chosen from databases (e.g., GenBank) based on the number of available sequences and reliable alignment. Example genes include Adora3, Bdnf, and Rag2.

- Sequence Alignment: Nucleotide sequences are aligned based on translated amino acid sequences using ClustalW, with poorly aligned flanking regions removed.

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Trees are reconstructed using multiple methods (Maximum Likelihood, Bayesian Inference, Maximum Parsimony, Neighbor-Joining) with software like PhyML or Mr. Bayes.

Workflow Diagram of Molecular Methods

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflows for the three molecular methods discussed, highlighting key divergences in their processes.

Research Reagent Solutions

Key reagents and kits are essential for implementing these molecular methods.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Kits

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| REPLI-g Mitochondrial DNA Kit (QIAGEN) | Whole genome amplification of mtDNA | Enriches mtDNA from samples prior to targeted sequencing [36] |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) | Prepares sequencing libraries with dual index barcoding | Used in both mtDNA-targeted and WGS protocols for multiplexing [36] [33] |

| KAPA Hyper Library Preparation Kit (Roche) | PCR-free library preparation for WGS | Reduces amplification bias in whole genome sequencing [36] |

| Exonuclease V | Enzymatic digestion of nuclear DNA | Enriches mtDNA by degrading linear nuclear DNA in targeted protocols [36] |

| BWA (Bioinformatics Tool) | Aligns sequencing reads to a reference genome | Standard for mapping reads in both WGS and targeted analyses [36] [38] |

| MitoCaller | Likelihood-based variant caller for mtDNA | Specifically calls heteroplasmies and homoplasmies, accounts for circular mtDNA genome [36] |

Application in Phylogeography and Population Connectivity

The choice of molecular toolkit directly impacts the interpretation of phylogeographic patterns and population connectivity.

- mtDNA in Phylogeography: mtDNA's high mutation rate and maternal inheritance make it ideal for tracing deep evolutionary histories and maternal lineages [38]. However, its non-recombining nature and smaller effective population size can lead to discordance with nuclear data, potentially reflecting sex-biased dispersal rather than overall population connectivity [38].

- Nuclear Markers for Population Structure: Nuclear SNPs provide independent, recombining markers that are less susceptible to the effects of selection on a single locus. They are better suited for detecting fine-scale population structure and recent gene flow [35] [38].

- WGS for Comprehensive Insights: WGS provides the most powerful approach by simultaneously capturing both mitochondrial and nuclear genomic variation [38]. This allows researchers to identify discordant patterns, such as mito-nuclear discordance, which can reveal complex histories of hybridization and introgression during secondary contact between previously isolated lineages [38]. Furthermore, WGS data enables the identification of large, low-recombining haploblocks in the nuclear genome, which can carry ancestral lineage information similar to mtDNA [38].

Integrating data from mitochondrial and nuclear genomes, especially through WGS, provides a versatile and powerful way to address complex phylogeographic dynamics and obtain a more holistic understanding of population connectivity.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three foundational analytical frameworks—Haplotype Networks, Ecological Niche Modelling (ENM), and hierarchical Approximate Bayesian Computation (hABC)—used in comparative phylogeography to decipher the history of connectivity and diversification among populations and species.

Comparative phylogeography seeks to understand how historical processes like climatic fluctuations and geological events have shaped the distribution of genetic diversity across species and regions [40]. The field relies on sophisticated analytical tools that integrate genetic, spatial, and environmental data. This article objectively compares the performance, applications, and experimental protocols of three pivotal frameworks: Haplotype Networks for visualizing genetic lineages, Ecological Niche Modelling (ENM) for predicting species' distributions through time, and hierarchical Approximate Bayesian Computation (hABC) for testing complex demographic models. Together, these methods enable researchers to move beyond simple description to statistically robust inferences about the processes driving phylogeographic patterns [40] [41].

Framework Comparison: Performance and Applications

The table below summarizes the core function, primary applications, and key performance metrics of each framework, highlighting their complementary strengths.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Analytical Frameworks

| Framework | Core Function & Applications | Data Input Requirements | Key Performance Metrics & Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype Networks | Visualizes genealogical relationships among genetic lineages [42]. Applications: Identifying dominant haplotypes, inferring population expansions, and visualizing geographic distribution of genetic lineages [43] [42]. | DNA sequences (e.g., cpDNA, nrDNA) or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs); sample locality information [43] [42]. | Speed: HapNetworkView (using fastHaN) constructs a network for 5,000 samples in ~40 min, significantly faster than tools like PopART or NETWORK [42]. Output: Network graphs showing haplotype relationships, mutation steps, and group composition. |

| Ecological Niche Modelling (ENM) | Predicts species' potential distribution based on occurrence records and environmental data [44] [43]. Applications: Reconstructing paleodistributions, identifying glacial refugia, and predicting range shifts [43] [41]. | Species occurrence localities; bioclimatic variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation); environmental layers for different time periods [43] [41]. | Accuracy: Machine learning-based ENMs can achieve high predictive accuracy (>0.87) [45]. Output: Maps of habitat suitability across different time periods (e.g., LGM, Mid-Holocene) [43]. |

| hierarchical Approximate Bayesian Computation (hABC) | Infers demographic history and tests alternative phylogeographic models without calculating exact likelihoods [40] [41]. Applications: Estimating divergence times, population sizes, and gene flow; testing simultaneous vs. non-simultaneous divergence across taxa [40] [41]. | Genetic data (e.g., SNPs, DNA sequences); prior distributions for model parameters; multiple competing demographic models [41]. | Performance: Effectively compares complex, non-linear models that are otherwise intractable [41]. Output: Posterior probabilities for competing models; parameter estimates (e.g., divergence time) with credibility intervals [40] [41]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A robust phylogeographic study often involves the sequential or integrated application of these frameworks. The diagram below outlines a typical workflow.

Protocol for Haplotype Network Construction and Analysis

This protocol details the steps for analyzing genetic data to construct and visualize haplotype networks, which reveal genealogical relationships.

- Step 1: Data Collection and Sequencing: Collect tissue samples from multiple populations. Amplify and sequence standard genetic markers, such as chloroplast DNA regions (

rbcL,matK,trnH-psbA) for plants or mitochondrial DNA for animals, and nuclear markers like the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS2) [43]. - Step 2: Sequence Alignment and Haplotype Identification: Align sequences using software like MEGA or ClustalW. Identify distinct haplotypes from the aligned sequences and calculate diversity indices (e.g., haplotype diversity

h, nucleotide diversityπ) using tools like DnaSP [43]. - Step 3: Network Construction and Visualization: Input the haplotype data into specialized software. HapNetworkView is recommended for its computational efficiency and interactive visualization features, especially with large sample sizes (e.g., 3,000-5,000 samples) [42]. Use algorithms like Median-Joining (MJN) or Statistical Parsimony (TCS) to construct the network.

- Step 4: Data Exploration: Use the software's interactive features to color-code nodes by geographic population, display mutation steps on edges, and highlight specific haplotypes of interest to explore spatial genetic structure [42].

Protocol for Ecological Niche Modelling (ENM)

This protocol outlines the process of modeling past, present, and future species distributions to infer range shifts.

- Step 1: Data Compilation: Gather species occurrence records from field surveys, herbarium collections, or public databases like GBIF. Obtain contemporary bioclimatic variables from WorldClim. Download paleoclimatic data layers for periods of interest (e.g., Last Glacial Maximum - LGM, Mid-Holocene) from climate model simulations (e.g., MIROC, CCSM) [43] [41].

- Step 2: Model Calibration and Projection: Use the present-day occurrence and climate data to calibrate a model. Algorithms like MaxEnt are widely used [43]. For robust risk prediction, multi-algorithm machine learning ensembles (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines) that use both presence and absence data are highly recommended, as they handle complex, non-linear relationships and show high predictive accuracy (>0.87) [45]. Project the calibrated model onto paleoclimatic layers to reconstruct past suitable habitats.

- Step 3: Model Evaluation and Interpretation: Evaluate model performance using metrics like AUC (Area Under the Curve) through cross-validation. Interpret the resulting maps to identify stable refugia, range expansion corridors, and areas of range contraction through time [43] [41].

Protocol for hierarchical Approximate Bayesian Computation (hABC)

This protocol is for testing complex demographic hypotheses that are difficult to address with traditional statistics.

- Step 1: Define Competing Models and Priors: Formulate a set of alternative demographic models (e.g., simultaneous divergence vs. non-simultaneous divergence; models with and without gene flow) based on initial insights from haplotype networks or ENM. Define biologically realistic prior distributions for parameters like effective population size and divergence time [40] [41].

- Step 2: Simulate and Compare Data: Use software like msBayes to simulate millions of genetic datasets under each competing model. Compare the simulated data to the observed genetic data using a set of summary statistics (e.g., FST, π, Tajima's D) [40].

- Step 3: Model Selection and Parameter Estimation: Calculate the posterior probability for each model to identify the best-supported demographic scenario. For the top model, estimate the posterior distributions of parameters (e.g., divergence times) to obtain values with credibility intervals [41].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and tools required for implementing the described frameworks.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item | Function/Application | Example Tools & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Markers | Used for phylogenetic and population genetic inference. | Chloroplast DNA (rbcL, matK, trnH-psbA); Nuclear DNA (ITS2) [43]. For high-resolution studies, genome-wide SNPs are preferred [41]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | For genetic data processing, analysis, and visualization. | HapNetworkView (haplotype networks) [42], msBayes (hABC) [40], dismo/BIOMOD in R (ENM) [44], fastHaN (efficient network construction) [42]. |

| Climatic Data Layers | Environmental predictors for ENM. | WorldClim (current climate); PaleoClim (paleoclimatic data) [43]. Key variables include isothermality, mean diurnal range, and precipitation seasonality [45]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Manages computationally intensive analyses. | Essential for running ABC simulations and machine learning ENM ensembles, especially with large genomic or spatial datasets [42] [41]. |

The most powerful insights in comparative phylogeography emerge from integrating these frameworks. For instance, a study on the Korean endemic Abeliophyllum distichum used ENM to identify a potential LGM refugium and post-glacial expansion routes, while hABC modeling tested and dated the divergence events among the resulting genetic lineages inferred from SNP data [41]. Similarly, research on Morinda officinalis combined haplotype networks, which revealed two major lineages, with ENM projections to correlate lineage divergence with historical range fluctuations during the Quaternary [43].

In conclusion, no single framework provides a complete picture. Haplotype networks excel at visualizing genealogical relationships, ENM provides a spatial and ecological context for historical processes, and hABC offers a statistically rigorous method for testing explicit demographic hypotheses. Their combined application, supported by the experimental protocols and tools detailed here, allows researchers to robustly reconstruct the complex history of connectivity and isolation that has shaped modern biodiversity.