Comparative Phylogenomics of Species Radiations: Unraveling Evolutionary Patterns with Genomic Tools

This article explores the transformative role of comparative phylogenomics in deciphering the patterns and processes of species radiations.

Comparative Phylogenomics of Species Radiations: Unraveling Evolutionary Patterns with Genomic Tools

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of comparative phylogenomics in deciphering the patterns and processes of species radiations. It covers foundational principles, current methodological advances—including new tools for whole-genome analysis—and strategies for troubleshooting complex phylogenetic challenges. By integrating validation frameworks and case studies from diverse lineages, we highlight how phylogenomic insights can identify evolutionary hotspots and genetic loci underlying rapid phenotypic evolution, with significant implications for understanding adaptation and informing biomedical discovery.

Unraveling Evolutionary Bursts: Core Concepts and Genomic Signals of Radiation

The uneven distribution of biological diversity across lineages and environments represents a central mystery in evolutionary biology. Species radiations, particularly rapid and adaptive ones, are fundamental to understanding how this diversity originates. This guide compares the core concepts of rapid diversification and adaptive radiation within the modern framework of comparative phylogenomics. We define rapid diversification as a lineage exhibiting an exceptionally high net diversification rate (speciation minus extinction) over a specific time period [1]. In contrast, adaptive radiation describes a process where a single ancestral species rapidly diversifies into multiple descendant species that exhibit phenotypic divergence and adapt to a wide range of ecological niches [2] [3]. While all adaptive radiations involve rapid diversification, not all rapid radiations are adaptive, as some may lack significant ecological divergence or may be driven by non-adaptive forces like sexual selection or geographic isolation [4] [1]. Understanding the mechanisms, patterns, and genomic underpinnings of these phenomena is crucial for researchers investigating the origins of biodiversity, with potential applications in identifying evolutionary trajectories and genetic targets relevant to drug discovery.

Conceptual Comparison: Rapid Diversification vs. Adaptive Radiation

The table below summarizes the core defining features, mechanisms, and research approaches for rapid diversification and adaptive radiation.

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts of Species Radiations

| Feature | Rapid Diversification | Adaptive Radiation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Concept | Accelerated lineage splitting, leading to a high number of species in a short time [1]. | Rapid diversification accompanied by ecological adaptation and phenotypic divergence [2]. |

| Primary Driver | Can be ecological opportunity, sexual selection, or non-adaptive processes like allopatric fragmentation [4] [1]. | Ecological opportunity is a key trigger, facilitating niche specialization [2] [3]. |

| Key Axes of Diversity | Primarily focused on species richness [1]. | Integrates species richness, phenotypic disparity, and ecological diversity [2] [4]. |

| Phylogenetic Pattern | Clades in the upper percentiles of net diversification rates contain most of Earth's species richness [1]. | Early burst of speciation and phenotypic evolution, often followed by a slowdown as niches fill [3]. |

| Relation to Selection | May involve frequent adaptive evolution, but can also proceed via neutral processes or drift, especially in small populations [5]. | Driven by natural selection adapting populations to different ecological niches [2] [5]. |

| Research Focus | Quantifying diversification rates and identifying "species pumps" [1]. | Linking genetic changes to ecological roles and phenotypic adaptations [2] [6]. |

The Paradox of Rapid Radiation

A central paradox in this field is that the hallmark rapid burst of speciation and niche diversification contradicts many standard speciation models, which predict decelerating speciation rates over time as niches subdivide and disruptive selection weakens [4]. Resolving this paradox requires mechanisms that enable repeated, rapid speciation events. Emerging theories to explain this include:

- The 'transporter' hypothesis, which involves introgression and the ancient origins of adaptive alleles.

- The 'signal complexity' hypothesis, which concerns the dimensionality of sexual traits.

- The role of fitness landscape connectivity and developmental plasticity ("plasticity first") in opening new evolutionary paths [4].

Quantitative Data on Patterns and Prevalence

Empirical data across the tree of life provides a scale for understanding the prevalence and impact of these radiations.

Table 2: Quantitative Prevalence of Rapid Radiations Across Life

| Clade / Group | Key Finding | Quantitative Measure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Life / Major Clades | Most species richness is contained within rapid radiations. | >80% of known species richness is in clades in the upper 90th percentile for diversification rates. | [1] |

| Frogs | Adaptive radiations contain most species and phenotypic diversity. | ~75% of both species richness and phenotypic diversity is in adaptive radiations. | [1] |

| Angiosperms | Adaptive evolution is more frequent in rapid radiations. | Significant increase in adaptive evolution frequency across 12 radiations (1,377 species). | [5] |

| Evolutionary Radiations | Population size correlates with adaptation frequency. | Significant negative correlation between population size and frequency of adaptive evolution. | [5] |

Experimental Protocols in Comparative Phylogenomics

Research in this field relies on robust methodologies to infer evolutionary history, trait evolution, and genomic signatures of selection.

Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts (PIC) for Correlated Evolution

This method tests for correlated evolutionary changes in two traits (e.g., gene expression in different cell types) across a phylogeny [7].

- Protocol:

- Data Collection: Obtain transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-seq) for the traits of interest from multiple species (e.g., 9+ mammalian species).

- Phylogeny Reconstruction: Build or obtain a time-calibrated molecular phylogeny for the species.

- Calculate Independent Contrasts: For each gene or trait, compute PICs. These estimates represent the amount of evolutionary change along independent branches of the phylogenetic tree, thus accounting for shared ancestry [7].

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate the correlation coefficient between the PICs for one trait (e.g., skin fibroblast gene expression) and the PICs for the other trait (e.g., endometrial stromal fibroblast expression) across all genes.

- Statistical Testing: Assess the significance of the correlations and filter out genes with minimal evolutionary change to avoid artifacts [7].

CALANGO: Phylogeny-Aware Genotype-Phenotype Association

CALANGO is a comparative genomics tool designed to discover quantitative genotype-phenotype associations across species while accounting for phylogenetic non-independence [6].

- Protocol:

- Input Data:

- Genomic Data: Genome annotations (e.g., functional annotations, k-mer counts) for multiple species.

- Phenotypic Data: A matrix of quantitative phenotypic traits for the same species.

- Phylogeny: A phylogenetic tree of the species studied.

- Configuration: Define the analysis parameters in a configuration file, specifying the genomic and phenotypic data, the phylogenetic tree, and the model to be used.

- Model Fitting: CALANGO uses phylogeny-aware linear models to test for associations between genomic features and phenotypes. This step controls for the fact that closely related species are not independent data points [6].

- Output & Interpretation: The tool provides a list of genomic regions or molecular functions significantly associated with the phenotype. Results can include evidence for both homologous regions and molecular functional convergence.

- Input Data:

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Conceptual Relationship and Workflow

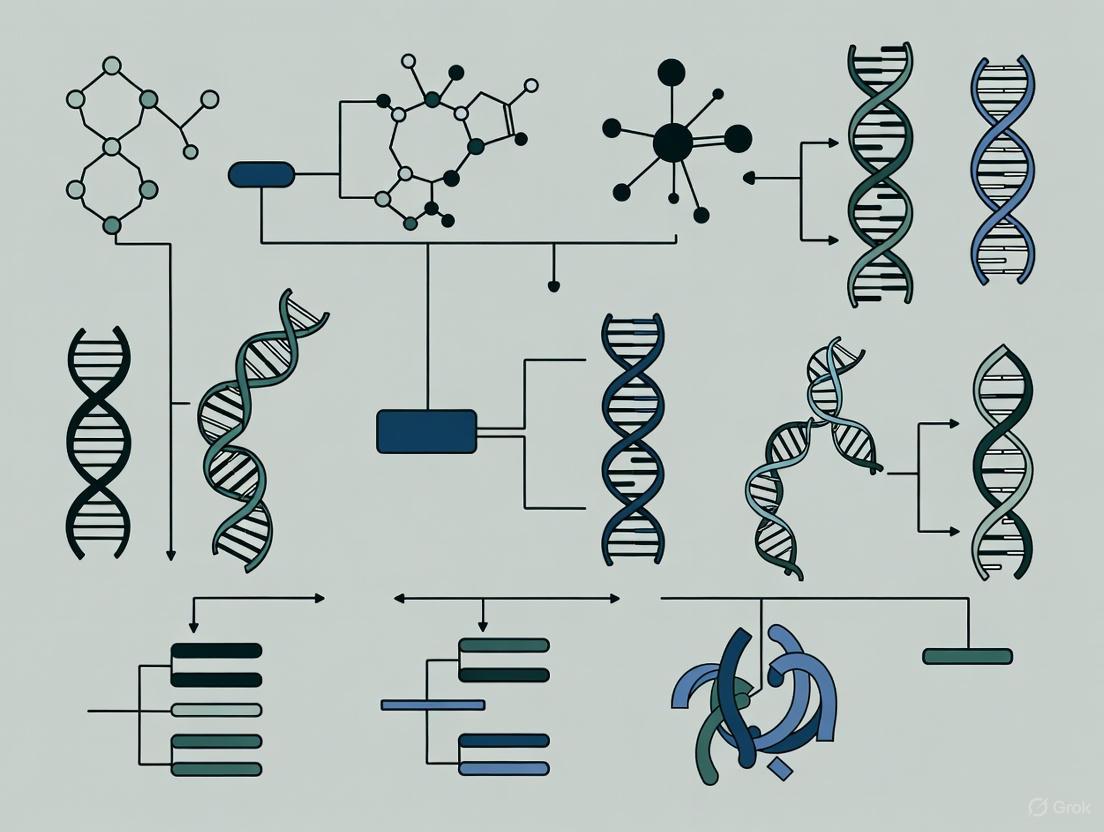

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between rapid diversification and adaptive radiation, and the general workflow for studying them.

Diagram 1: Conceptual relationship and key outcomes of different radiation types.

Phylogenomics Analysis Pipeline

This diagram outlines a standard workflow for phylogenomic analysis of species radiations.

Diagram 2: Standard phylogenomics workflow for analyzing radiations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and computational tools used in research on species radiations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item Name | Type/Format | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Sequencing Data | Raw sequencing reads (FASTQ) or processed counts. | Profiling gene expression across species or tissues to study evolutionary changes, e.g., in fibroblasts [7]. |

| Whole-Genome Assemblies | Assembled genomic sequences (FASTA). | Serving as the foundational reference for comparative genomics, association studies, and phylogenetics [6]. |

| CALANGO Software | R Package / Command-line tool. | Detecting genome-wide, quantitative genotype-phenotype associations across species using phylogeny-aware models [6]. |

| Time-Calibrated Phylogeny | Newick format tree file with divergence times. | Providing the evolutionary framework for testing hypotheses on diversification timing, rates, and trait evolution [7] [6]. |

| Phenotypic Data Matrix | Table of quantitative traits per species. | Representing measurable morphological or ecological traits for association with genomic data [6]. |

| Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts (PIC) | Statistical Method / Algorithm. | Quantifying and comparing evolutionary change in traits while accounting for shared phylogenetic history [7]. |

Evolutionary radiations, periods of rapid species diversification, are responsible for a significant portion of the Earth's biodiversity; over 80% of known species richness is contained within clades exhibiting high net diversification rates [1]. Untangling the evolutionary history of these radiations is a central goal in modern phylogenomics, as the swift succession of speciation events often leaves complex and conflicting genomic signatures. Standard phylogenetic models, which assume a simple branching tree, are frequently inadequate for reconstructing these histories.

This guide focuses on three primary genomic hallmarks—incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), hybridization and introgression, and gene duplication—that are paramount for accurately interpreting species relationships during radiations. We objectively compare the performance of various analytical methods and experimental protocols used to detect these signals, providing a foundational resource for researchers and scientists in evolutionary biology and comparative genomics.

Genomic Hallmarks: Characteristics and Detection

The table below defines the core genomic hallmarks of radiation and their evolutionary implications.

Table 1: Core Genomic Hallmarks of Evolutionary Radiation

| Genomic Hallmark | Definition | Primary Evolutionary Cause | Impact on Phylogeny |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Lineage Sorting (ILS) | The failure of ancestral genetic polymorphisms to coalesce (reach a common ancestor) in the immediate ancestor of a speciation event, causing gene tree discordance [8]. | Rapid successive speciation, large ancestral population size [9] [10]. | Extensive gene tree heterogeneity despite a single species tree; discordance is random and symmetric around a node [11]. |

| Hybridization & Introgression | The transfer of genetic material between two divergent, but not fully reproductively isolated, lineages through hybridization and backcrossing [9]. | Secondary contact between previously isolated populations or species [10]. | Asymmetric gene tree discordance; specific directional signal of gene flow between taxa [9]. |

| Gene Duplication | The duplication of a region of DNA containing a gene, creating new genetic material that can evolve novel functions (neofunctionalization) or partition ancestral functions (subfunctionalization). | Diverse mechanisms including whole-genome duplication, segmental duplication, and unequal crossing over. | Complicates orthology assignment; can be a source of innovation driving adaptive radiation if duplicates acquire new, advantageous functions. |

Visualizing the Core Concepts

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in how ILS and Hybridization generate conflicting gene trees from a single species history.

Methodological Comparison for Detecting Hallmarks

Distinguishing between ILS and introgression, a common challenge, requires specific tree-based and population genetic methods. The table below compares the leading techniques.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Methods for Detecting Introgression vs. ILS

| Method | Underlying Principle | Best For | Key Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-statistics (ABBA-BABA) | Tests for an imbalance in allele sharing patterns between four taxa to detect introgression [8]. | Recent Introgression: Identifying gene flow between sister species or between a species and an outgroup [8]. | Requires a well-defined four-taxon phylogeny ((P1, P2), P3), Outgroup). Sensitive to ancestral population structure. |

| QuIBL (Quantifying Introgression via Branch Lengths) | Uses the distribution of branch lengths across gene trees to distinguish between ILS and introgression models via a Bayesian framework [8] [11]. | Ancient Introgression: Detecting historical hybridization events deeper in time [8]. | Computationally intensive. Provides explicit estimates of introgression rates. Performance depends on accurate branch length estimation. |

| PhyloNet/Network Analysis | Infers phylogenetic networks directly from gene trees or sequence data, explicitly modeling hybridization events as reticulations [11]. | Complex Reticulation: Inferring evolutionary histories with multiple hybridization events [11]. | Highly complex model selection. Can be combined with MSC to account for ILS simultaneously. |

| Site Concordance Factors (sCF) | Measures the percentage of decisive alignment sites supporting a given branch in a reference tree [11]. | Localizing Discordance: Identifying specific branches in a phylogeny with high genealogical disagreement [11]. | Complements tree-based methods. Low sCF values indicate branches prone to ILS or introgression. |

Visualizing the Analytical Workflow

A robust phylogenomic analysis to decipher these signals involves an integrated workflow, from data generation to model selection.

Case Studies in Phylogenomic Analysis

Primate Rapid Radiations

A phylogenomic study of 26 primate species, including three new OWM genomes, revealed high levels of genealogical discordance associated with multiple rapid radiations [9]. The study found that strongly asymmetric patterns of gene tree discordance around specific branches were indicative of ancient introgression between ancestral lineages, while more symmetric discordance was consistent with ILS. This research highlights that rapid radiations and subsequent introgression have been pervasive forces throughout primate evolution, complicating the reconstruction of a single, unambiguous species tree [9].

Rapid Radiation in Diploid Cotton

Research on the Gossypium genus, incorporating four new genome assemblies, uncovered intricate phylogenies driven by both introgression and ILS [8]. A detailed ILS map for a rapidly diverged lineage revealed that regions affected by ILS were non-randomly distributed across the genome. Furthermore, evidence indicated that robust natural selection was acting on specific ILS regions, and a significant proportion of speciation-associated genes overlapped with these ILS signatures [8]. This provides a compelling case for the role of ILS in preserving ancestral adaptive potential during rapid diversification.

Reticulate Evolution in the Tulip Tribe

Transcriptome-based phylogenomics of the Liliaceae tribe Tulipeae (including Tulipa, Amana, and Erythronium) failed to resolve a unambiguous evolutionary history among the genera due to pervasive ILS and reticulate evolution [11]. The study concluded that the phylogenetic signal was likely obscured by deep ILS and hybridization, making it difficult to distinguish the true species tree. This case demonstrates that even with large genomic datasets (2,594 nuclear orthologous genes), evolutionary history can remain unresolved when these processes are extensive [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful phylogenomic research requires a suite of wet-lab and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Phylogenomics

| Category / Reagent | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Illumina Hi-seq, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) long-read sequencing [9]. | Generating high-quality genomic or transcriptomic data. Long-read tech improves assembly continuity (Scaffold N50) [9]. |

| Genome Assembly & Annotation | NCBI Eukaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline, Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) [9]. | Producing and evaluating the completeness and accuracy of genome assemblies and gene annotations. |

| Orthology Assignment | OrthoFinder, Phylogenetically-informed Pipeline for DDD (PPD) [10]. | Identifying groups of genes (orthologs) descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor, critical for accurate tree-building. |

| Phylogenetic Inference (ML) | IQ-TREE, RAxML [11]. | Constructing maximum likelihood gene trees from sequence alignments. |

| Species Tree Inference (Coalescent) | ASTRAL [11]. | Inferring the primary species tree from multiple gene trees while accounting for ILS. |

| Introgression Tests | DFOIL [8], D-statistics (ABBA-BABA) [8], PhyloNet [11]. | Statistically testing for and quantifying signals of hybridization and introgression between lineages. |

| ILS vs. Introgression | QuIBL [8] [11], Site Concordance Factors (sCF) [11]. | Differentiating whether gene tree discordance is caused by ILS or introgression. |

The evolutionary relationships among the major lineages of modern birds (Neoaves) have posed one of the most persistent challenges in phylogenetics. Neoaves, comprising approximately 95% of all avian species, underwent a rapid diversification into at least ten major clades over a relatively short evolutionary timescale [12]. This explosive radiation has resulted in extensive phylogenetic discordance, where different genomic studies have recovered conflicting relationships among deep neoavian lineages despite using genome-scale datasets [12] [13]. Discrepancies have been attributed to multiple factors including diversity of species sampled, phylogenetic methodology, and the choice of genomic regions [12]. The focal point of this case study is to evaluate how the strategic use of intergenic regions—non-coding sequences located between genes—has provided new insights into resolving these deep evolutionary relationships within Neoaves, particularly in the context of their radiation following the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) mass extinction event approximately 66 million years ago.

Experimental Protocols: Genomic Dataset Construction and Phylogenetic Inference

Genome Sequencing and Dataset Assembly

The foundational dataset for this analysis was generated through the Bird 10,000 Genomes (B10K) Project "family phase," which produced genome assemblies for 363 bird species representing 218 taxonomic families (92% of total avian families) [12] [14]. This extensive sampling addressed previous limitations in taxon representation that had hampered earlier phylogenetic efforts. Researchers analyzed nearly 100 billion nucleotides, creating an alignment approximately 50 times larger than previous genome-scale avian datasets [12].

The core experimental approach involved:

- Whole-genome alignment followed by systematic sampling of intergenic regions across 10 kb windows of the genome [12].

- Selection of 1 kb loci within the first 2 kb of each window, balancing phylogenetic informativeness against potential recombination within loci.

- Filtering to obtain purely intergenic regions by removing loci overlapping exonic and intronic regions, resulting in a final set of 63,430 intergenic loci totaling 63.43 megabase pairs [12].

This experimental design specifically targeted intergenic regions due to their theoretical advantage of being under lower selective pressure compared to protein-coding regions, thus potentially reducing systematic errors caused by model misspecification in phylogenetic analyses [12].

Phylogenetic Inference Methodology

The phylogenetic tree reconstruction employed a multi-faceted analytical approach:

- Coalescent-based framework: The main phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using coalescent methods that explicitly account for incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), a well-documented phenomenon in early Neoaves [12].

- Concatenation analysis: For comparative purposes, researchers also performed a concatenated analysis of the same 63,430 intergenic loci [12].

- Statistical support assessment: Branch support was evaluated using posterior probabilities (coalescent analysis) and bootstrap values (concatenation analysis) [12].

The analytical workflow integrated these methods to robustly infer evolutionary relationships while accounting for stochastic and systematic errors that have complicated previous analyses.

Complementary Analytical Approaches

Additional specialized methods were employed to address specific challenges:

- Time calibration: The phylogenetic tree was time-calibrated using empirically generated calibration densities for 34 nodes based on 187 fossil occurrences, applied in a Bayesian sequential-subtree framework [12].

- Discordance quantification: Researchers assessed phylogenetic discordance using quartet scores measured across the genome, identifying regions with exceptional signal [12] [13].

- Evolutionary rate analysis: Rates of molecular evolution were decomposed across lineages and genomic regions to identify key shifts associated with diversification events [15].

Results & Discussion: Performance Comparison of Genomic Partitionitions

Resolving Power of Different Genomic Regions

Table 1: Comparison of Phylogenetic Performance Across Genomic Partitions

| Genomic Region | Number of Loci | Key Supported Relationships | Major Limitations | Concordance with Species Tree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intergenic regions | 63,430 | Mirandornithes as earliest Neoaves; Elementaves clade; Columbaves | Requires extensive filtering | High (reference tree) |

| Exonic regions | Variable by study | Often supports Columbea/Passerea division | High functional constraint; model misspecification | Variable/Conflicting |

| Intronic regions | Variable by study | Intermediate performance | Moderate selective constraints | Moderate |

| UCEs | ~1,000-5,000 | Variable between studies (Columbea/Passerea vs. alternatives) | Strong conservation bias; limited sites | Variable between analyses |

| Mitochondrial DNA | 37 genes | Limited resolution for deep nodes | Single locus; distinct evolutionary history | Often conflicting |

The comparative analysis reveals that intergenic regions provided several key advantages for resolving deep neoavian relationships. Their extensive sampling (63,430 loci) enabled sufficient statistical power to resolve short internal branches characteristic of rapid radiations [12]. Additionally, intergenic regions are theoretically under lower selective pressure than coding sequences, reducing the potential for model misspecification that can introduce systematic error [12]. The performance comparison indicates that sufficient locus sampling was more critical than extensive taxon sampling for resolving difficult nodes, though the combination of both strategies proved most effective [14].

The Impact of an Anomalous Genomic Region

A significant finding from follow-up investigations revealed an exceptional 21-megabase region on chromosome 4 that presented a strong, discordance-free signal for an alternative topology (Columbea/Passerea division) [13]. This region exhibited strikingly different phylogenetic properties compared to the rest of the genome:

- Suppressed recombination: The region showed evidence of an ancient rearrangement that blocked recombination and remained polymorphic for millions of years before fixation [13].

- Exceptional length: The 21-Mb region dramatically exceeds expected sizes of recombination-free windows (typically kilobases, not megabases) for relationships dating to ~65 million years ago [13].

- Potential to mislead: This region was shown to have disproportionately influenced previous phylogenomic studies with limited taxon sampling, potentially explaining earlier conflicts in neoavian phylogenetics [13].

This finding highlights the importance of genome-wide sampling rather than relying on limited genomic regions, as singular anomalous regions can exert disproportionate influence on phylogenetic inference.

Novel Phylogenetic Framework for Neoaves

The analysis of intergenic regions within a coalescent framework produced a well-supported phylogenetic tree with several key features:

Figure 1: Novel Phylogenetic Framework for Neoaves Based on Intergenic Regions

The tree topology confirmed that Neoaves experienced rapid radiation at or near the K-Pg boundary [12]. Within Neoaves, four major clades were resolved, including a novel clade named Elementaves (comprising Aequornithes, Phaethontimorphae, Strisores, Opisthocomiformes, and Cursorimorphae), which represents lineages that diversified into terrestrial, aquatic, and aerial niches [12]. This proposed relationship was supported specifically in coalescent-based analyses of intergenic regions and UCEs, but not by exons, introns, or in concatenated analysis of intergenic regions, highlighting the impact of both data type and analytical method [12].

Temporal Framework of Neoaves Diversification

The time-calibrated phylogenetic analysis produced age estimates with considerably narrower 95% credible intervals than previous studies, providing a more precise temporal framework for neoavian diversification [12]. The results indicated that:

Table 2: Estimated Divergence Times for Major Neoavian Lineages

| Evolutionary Event | Estimated Time (Ma) | 95% Credible Interval | Relationship to K-Pg Boundary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mirandornithes divergence | 67.4 Ma | 66.2–68.9 Ma | Pre-dates boundary |

| Columbaves divergence | 66.5 Ma | 65.2–67.9 Ma | Pre-dates boundary |

| Elementaves-Telluraves split | ~65 Ma | Spans K-Pg boundary | Approximately coincident |

| Crown Elementaves diversification | ~65 Ma | Spans K-Pg boundary | Post-boundary radiation |

Only two neoavian divergences (Mirandornithes and Columbaves) were estimated to have occurred before the K-Pg boundary, with all subsequent divergences postdating the boundary [12]. This evolutionary timeline lends stronger support to a post-K-Pg diversification of Neoaves than previous studies, aligning with the "big bang" scenario of rapid diversification following ecological opportunity created by the mass extinction [12]. These patterns were consistent across alternative dating analyses, highlighting the robustness of the estimated chronology [12].

Integrated Genomic and Phenotypic Evolution

Beyond topological resolution, analyses revealed coordinated shifts in genomic evolutionary patterns and phenotypic traits following the K-Pg transition:

- Sharp increases in effective population size, substitution rates, and relative brain size were detected following the K-Pg extinction event, supporting the hypothesis that emerging ecological opportunities catalyzed the diversification of modern birds [12] [14].

- Molecular evolutionary shifts were closely associated with changes in developmental mode and adult body mass [16]. Specifically, analyses identified 17 molecular model shifts on 12 phylogenetic edges, with 15 shifts occurring very close to the K-Pg boundary [16].

- Life history integration: Random forest analyses identified developmental mode and adult body mass as the most important traits associated with molecular evolutionary shifts, highlighting the integrated nature of genomic and phenotypic evolution during this radiation [16].

These findings suggest that the end-Cretaceous mass extinction triggered integrated patterns of evolution across avian genomes, physiology, and life history near the dawn of the modern bird radiation [16].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Avian Phylogenomics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Primary Function | Application in Current Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina short-read; PacBio long-read | Genome assembly | Generating 363 genome assemblies [12] |

| Genomic Resources | B10K dataset; VGP genomes | Reference sequences | Family-level phylogenetic sampling [12] [17] |

| Phylogenetic Algorithms | ASTRAL; concatenation approaches | Species tree inference | Coalescent-based analysis of intergenic loci [14] |

| Comparative Genomic Tools | Janus; phylogenetic comparative methods | Mode shift detection; trait evolution | Identifying molecular model heterogeneity [16] |

| High-Performance Computing | Expanse supercomputer (SDSC) | Large-scale phylogenetic analysis | Analyzing 60,000+ genomic regions [14] |

The computational methods pioneered for this research, particularly the ASTRAL algorithms, have become standard tools for reconstructing evolutionary trees across various animal groups, demonstrating the broader impact of this methodological innovation [14]. The strategic combination of extensive genomic resources (B10K project) with sophisticated analytical frameworks enabled the resolution of previously intractable phylogenetic questions.

This case study demonstrates that the strategic use of intergenic regions within a coalescent framework successfully resolved key relationships in the deep neoavian radiation that had remained contentious despite previous genome-scale efforts. The resulting phylogenetic estimate offers fresh insights into the rapid radiation of modern birds and provides a taxon-rich backbone tree for future comparative studies [12]. The finding that sufficient loci rather than extensive taxon sampling were more effective in resolving difficult nodes provides valuable guidance for future experimental design in phylogenomics [12] [14].

Remaining recalcitrant nodes involve species that present particular challenges for phylogenetic modeling due to extreme DNA composition, variable substitution rates, incomplete lineage sorting, or complex evolutionary events such as ancient hybridization [12]. Future research directions should include:

- Continued development of phylogenetic methods that better account for heterogeneous evolutionary processes across the genome.

- Expanded taxonomic sampling combined with chromosome-level genome assemblies to improve resolution of persistent problematic nodes.

- Integrated models that simultaneously address incomplete lineage sorting, introgression, and other sources of phylogenetic discordance.

- Functional genomic approaches to link phylogenetic patterns to the phenotypic evolution underlying avian diversification.

The resolution of the deep neoavian relationships using intergenic regions represents a significant advance in our understanding of avian evolutionary history and provides a robust framework for exploring the genomic foundations of avian biodiversity.

The order Fagales, a keystone lineage of woody plants including oaks, beeches, birches, and walnuts, has dominated temperate and subtropical forests since the Late Cretaceous [18]. This ecologically significant group presents an ideal model system for investigating the complex relationships between genomic evolution and phenotypic disparity—the diversity of morphological forms—across geologic timescales [18]. Recent advances in sequencing technologies and analytical methods have enabled unprecedented investigation into how major plant lineages fill morphospace (the theoretical spectrum of possible morphological variation) and whether this diversification couples with genomic events like whole-genome duplications [18]. Research on Fagales demonstrates a compelling case where rapid early phenotypic evolution corresponds with genomic hotspots of duplication and conflict, while species diversification follows a separate trajectory, highlighting the multidimensional nature of evolutionary radiation [18] [19] [20].

Analytical Framework: Methodologies for Integrated Phylogenomic and Phenomic Analysis

Phylogenomic Reconstruction and Divergence Time Estimation

Transcriptomic and Phylogenomic Data Generation: Researchers generated transcriptome data for approximately 160 ingroup Fagales species, representing most extant genera [18]. Phylogenomic analyses employed both maximum-likelihood (ML) and maximum quartet support species tree (MQSST) approaches, yielding highly congruent and well-supported topologies [18]. The Fagales phylogeny resolves previously contentious relationships, confirming Nothofagaceae and Fagaceae as successively sister to the core Fagales, with the remainder comprising a Betulaceae-Ticodendraceae-Casuarinaceae (BTC) clade and a Juglandaceae-Myricaceae (JM) clade [18].

Divergence Time Estimation with Fossil Integration: To establish a robust temporal framework, analyses incorporated 52 extinct Fagales species (36 extinct genera) alongside 156 extant species (32 extant genera) [18]. This integration of rich fossil evidence enabled reliable dating of major divergence events, indicating a Fagales origin in the Early Cretaceous with a stem age of 108.5 million years ago (Ma) and a crown age of 105 Ma [18]. Crown ages for extant families were estimated between 93-67 Ma, confirming a Cretaceous diversification for major lineages [18].

Phenotypic Disparity and Evolutionary Rate Analyses

Multidimensional Phenotypic Dataset: Unlike previous studies focusing on single organ systems, researchers compiled a comprehensive phenotypic dataset comprising 152 characters integrated across multiple major organ systems, including wood anatomy, leaf structure, pollen morphology, and diaspore functional morphology [18]. This approach captured the true morphological diversity of Fagales more effectively than single-system analyses.

Morphospace and Evolutionary Rate Quantification: Scientists quantified phenotypic disparity by measuring morphospace occupation through time and estimated rates of phenotypic evolution using phylogenetic comparative methods [18]. These analyses specifically tested whether Fagales conformed to an "early-burst" model of disparification, characterized by rapid morphospace filling followed by relative stasis [18].

Genomic Conflict and Duplication Detection

Gene Duplication and Whole-Genome Duplication Inference: Phylogenomic datasets were analyzed to identify hotspots of gene duplication (GD) and whole-genome duplication (WGD) using multiple evidence lines, including gene tree discordance, Ks plots (analyzing synonymous substitution rates), and chromosome number comparisons [18]. These methods allowed researchers to pinpoint historical duplication events and assess their retention across descendant lineages.

Mitogenomic and Plastomic Analyses: Comparative analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes across Fagales taxa provided additional insights into genomic evolution, including structural variation, horizontal transfer, and evolutionary rates [21] [22]. These organellar genomes offered complementary perspectives to nuclear genomic data.

Table 1: Key Genomic and Phenotypic Datasets in Fagales Research

| Data Type | Sampling Scope | Analytical Methods | Primary Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomic Data | ~160 species across extant genera | Maximum-likelihood phylogeny; Species tree methods | Resolved contentious relationships; Identified genomic conflict zones |

| Fossil Phenotypic Data | 52 extinct species (36 genera) + 156 extant species | Morphospace analysis; Disparity-through-time | Established early Cenozoic morphospace filling; High initial evolutionary rates |

| Chloroplast Genomes | 256 species representing 32/34 genera | Plastome phylogenomics; Conflict assessment | Revealed hybridization history; Chloroplast capture events |

| Mitochondrial Genomes | 23 species across 5 families | Comparative genomics; Structural analysis | Detected mosaic genomes; Horizontal transfer events |

Results: Decoupling Phenotypic, Genomic, and Species Diversification

Early-Burst Phenotypic Disparification

Analyses of phenotypic evolution in Fagales revealed a pronounced early-burst pattern, with morphospace largely filled by the early Cenozoic [18]. Rates of phenotypic evolution were highest during the initial radiation of the Fagales crown group and its major families in the Cretaceous period, followed by a significant slowdown in disparity accumulation despite continued species diversification [18] [20]. This pattern demonstrates that the fundamental architectural variation within Fagales was established early in the group's evolutionary history, with later diversification occurring within established morphological constraints.

The multidimensional phenotypic dataset revealed considerable variation across organ systems, including wood anatomy, leaf structure, pollen morphology, and diaspore functional morphology, despite relative uniformity in life-history attributes like woody growth form and tendency for unisexual flowers [18]. This finding underscores the importance of integrated multi-trait analyses for capturing true disparity patterns rather than relying on single-system assessments.

Genomic Hotspots: Gene Duplication and Whole-Genome Duplication

Investigations into genomic evolution identified recurrent hotspots of gene duplication and genomic conflict across the Fagales phylogeny [18]. Researchers detected one shared whole-genome duplication event in Juglandaceae and 12 gene duplication hotspots across the order [18]. Specifically:

- Juglandaceae WGD: 636 duplicated genes (5.8% of examined genes) were detected at the crown node of Juglandaceae, with 2,348 duplicated genes (21.3%) retained after the divergence of Rhoiptelea chiliantha [18]. A distinct Ks peak and doubled base chromosome numbers provided additional support for this WGD event [18].

- Major GD Hotspots: 1,534 duplicated genes (13.9%) were identified at the Fagaceae + core Fagales crown node, with 309 (2.8%) at the core Fagales crown node [18]. In Fagaceae specifically, 604 (5.5%) duplicated genes were detected at the Quercoideae crown node [18].

Strikingly, these genomic hotspots often corresponded temporally with peaks in phenotypic evolutionary rates, suggesting a potential relationship between genomic and morphological innovation [18] [20].

Multidimensional Decoupling of Evolutionary Processes

A fundamental finding from Fagales research is the decoupling of three evolutionary dimensions: species diversification, phenotypic evolution, and genomic duplication events [18] [20]. While phenotypic disparification followed an early-burst pattern largely confined to the Cretaceous, species diversification continued throughout the Cenozoic [18]. Similarly, although some gene duplication hotspots corresponded to increased phenotypic evolution, many genomic events did not correlate with either increased disparity or species richness [18]. This multidimensional decoupling challenges simplified narratives of evolutionary radiation and highlights the complexity of macroevolutionary processes in major plant lineages.

Table 2: Major Whole-Genome and Gene Duplication Events in Fagales

| Genomic Event | Phylogenetic Location | Key Evidence | Correlated Phenotypic Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Juglandaceae WGD | Crown node of Juglandaceae | 636 duplicated genes; Distinct Ks peak; Doubled chromosome numbers | Increased phenotypic evolutionary rates |

| Fagaceae + Core Fagales GD | Crown node of Fagaceae + core Fagales | 1,534 duplicated genes (13.9% of analyzed genes) | Elevated phenotypic evolution during early radiation |

| Core Fagales GD | Crown node of core Fagales | 309 duplicated genes (2.8% of analyzed genes) | Corresponded with early morphospace expansion |

| Quercoideae GD | Crown node of Quercoideae | 604 duplicated genes (5.5% of analyzed genes) | Associated with lineage-specific morphological innovation |

Experimental Replication: Key Methodologies for Phylogenomic Analysis

Transcriptome Assembly and Phylogenetic Reconstruction

For transcriptome-based phylogenies, researchers typically follow this workflow:

- RNA Extraction and Sequencing: Extract high-quality RNA from fresh or flash-frozen plant tissues, followed by cDNA library preparation and Illumina sequencing [18].

- Data Processing and Assembly: Process raw reads using quality control tools like Trimmomatic, followed by de novo transcriptome assembly using pipelines such as TRINITY or similar specialized protocols [18].

- Ortholog Identification: Identify orthologous genes across taxa using alignment-based (e.g., BLAST) and phylogenetic (e.g., OrthoFinder) methods [18].

- Phylogenomic Analysis: Conduct concatenated and coalescent-based species tree analyses using maximum likelihood (RAxML, IQ-TREE) and summary methods (ASTRAL) [18].

This methodology generates highly supported phylogenetic hypotheses while simultaneously providing data for gene duplication inference.

Gene Duplication and WGD Inference

Detecting ancient gene duplications and WGD events requires multiple lines of evidence:

- Gene Tree-Species Tree Comparison: Reconstruct individual gene trees and identify duplication events through comparison with the species tree [18].

- Ks Distribution Analysis: Calculate synonymous substitution rates (Ks) between paralogs to identify peaks suggestive of WGD events [18].

- Chromosome Number Comparison: Examine haploid chromosome numbers across lineages for patterns consistent with ancient polyploidy (e.g., doubled numbers) [18].

- Synteny Analysis: Identify conserved gene order across genomes to detect large-scale duplication events [22].

Integrating these approaches provides robust inference of historical duplication events, even in lineages that have experienced substantial diploidization.

Phenotypic Disparity Analysis

Quantifying morphological disparity involves:

- Character Scoring: Compile extensive phenotypic datasets from herbarium specimens, fossil material, and literature sources, capturing variation across multiple organ systems [18].

- Morphospace Construction: Use multivariate statistics (e.g., Principal Coordinates Analysis) to create theoretical morphospaces [18].

- Disparity Metrics: Calculate morphological disparity indices (e.g., sum of variances, mean pairwise distances) for different time bins and lineages [18].

- Evolutionary Rate Estimation: Employ phylogenetic comparative methods (e.g, Bayesian approaches) to estimate rates of phenotypic evolution across the tree [18].

This methodology enables rigorous testing of evolutionary models like the early-burst hypothesis.

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for Phylogenomic and Phenomic Analysis in Fagales Research. The pipeline combines genomic data (yellow/green) with phenotypic data (red) for integrated evolutionary analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Reagents for Phylogenomic Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application in Fagales Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore | Generate genomic, transcriptomic, and organellar genome data [18] [22] |

| Assembly Software | SPAdes, GetOrganelle, TRINITY, Unicycler | De novo assembly of nuclear and organellar genomes from sequencing reads [21] [22] |

| Annotation Tools | GeSeq, CPGAVAS2, Geneious | Structural and functional annotation of organellar and nuclear genomes [22] [23] |

| Phylogenetic Software | RAxML, IQ-TREE, ASTRAL, MrBayes | Phylogenomic tree inference using concatenation and coalescent methods [18] |

| Evolutionary Analysis | BEAST2, RevBayes, PHYLIP | Divergence time estimation, ancestral state reconstruction, rate analysis [18] |

| Comparative Genomics | mVISTA, D-GENIES, SyRI | Genome structure comparisons, synteny analysis, divergence hotspot identification [22] [24] |

The Fagales case study demonstrates that plant diversification follows multidimensional trajectories, with phenotypic, genomic, and species richness patterns largely decoupled across geological timescales [18] [20]. The early-burst model of phenotypic disparification, coupled with corresponding genomic hotspots, suggests that morphological innovation is concentrated in early radiation phases, potentially facilitated by genomic events like WGD [18]. However, the complex relationships between these dimensions resist simplification, highlighting the need for integrated approaches that capture evolutionary complexity.

These findings from Fagales research provide a framework for investigating other major plant radiations, suggesting that similar patterns of decoupled diversification might be widespread across the angiosperm tree of life. The methodologies and insights developed through Fagales studies offer powerful approaches for unraveling the complex interplay between genomic evolution and phenotypic diversity that has shaped the plant world.

The Critical Role of Phylogenetic Trees in Comparative Genomic Analysis

Comparative genomic analysis seeks to understand the evolutionary processes that shape the genomes of organisms. At the heart of this field lies the phylogenetic tree, a diagrammatic hypothesis of the relationships among species or genes. A robust phylogenetic framework is indispensable, as it allows researchers to trace the origin of genetic innovations, understand patterns of selection, and decipher the mechanisms underlying rapid species radiations, which are responsible for a majority of Earth's known biodiversity [1]. This guide compares the performance of different phylogenetic methods and data types, providing a foundation for studies in comparative phylogenomics.

Performance Comparison of Phylogenetic Methods

The choice of phylogenetic method and data type significantly impacts the accuracy and interpretation of evolutionary history. A 2025 study on barnacle mitogenomes provides a direct performance comparison of three common approaches, highlighting their distinct strengths and weaknesses [25].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Three Phylogenetic Methods Based on Mitochondrial Genomes [25]

| Phylogenetic Method | Data Type Used | Monophyletic Preservation Rate | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concatenated Protein-Coding Genes (PCGs) | Nucleotide sequences of 13 mitochondrial PCGs | 78.8% | Highest resolution for deep relationships; most suitable for overall phylogenetic studies. | Requires complete genome data; computationally intensive. |

| Single Marker (COX1) | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene region (658 bp) | 61.3% | Rapid and cost-effective; useful for species identification (DNA barcoding). | Lower phylogenetic resolution; can produce misleading topologies for complex radiations. |

| Gene Order Analysis | Arrangement and orientation of all mitochondrial genes | 50.0% | Provides unique insights into genome evolution and rearrangement hotspots. | Lowest monophyly preservation; not suitable for primary phylogeny reconstruction. |

The study found that trees built from these three methods exhibited significant topological differences, with normalized Robinson-Foulds distances ranging from 0.55 to 0.92, indicating low similarity between the inferred evolutionary histories [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide context for the data in Table 1, below are the detailed methodologies from the key study cited.

This protocol outlines the steps for comparing phylogenetic methods using mitochondrial genomic data.

Step 1: Sample Collection and DNA Sequencing

- Collect biological samples (e.g., barnacles Amphibalanus eburneus, Fistulobalanus kondakovi, and Megabalanus rosa).

- Extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue DNA Kit, Qiagen).

- Prepare a genomic library and sequence using a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq 6000). Perform quality control on raw reads with software like Trim_Galore.

Step 2: Genome Assembly and Annotation

- Assemble the complete mitochondrial genome using a combined de novo and reference-based approach (e.g., using MitoZ v3.5 with the

genetic_code 5andclade Arthropodaparameters). - Polish the assembly with a tool like Polypolish v0.5.0 and annotate the genes using a reference genome. Generate a circular map for visualization with a server like CGView.

- Assemble the complete mitochondrial genome using a combined de novo and reference-based approach (e.g., using MitoZ v3.5 with the

Step 3: Dataset Compilation

- Compile a dataset of multiple complete mitochondrial genomes (e.g., 34 genomes) from public databases (e.g., NCBI GenBank), including appropriate outgroup species.

Step 4: Phylogenetic Tree Construction (Three Methods)

- Gene Order Tree: Use Maximum Likelihood for Gene-Order (MLGO) analysis, considering gene position and strand orientation. Assess branch support with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

- Concatenated PCG Tree: Align nucleotide sequences of the 13 protein-coding genes using CLUSTAL Omega. Construct a maximum likelihood tree (e.g., using raxmlGUI 2.0 with a GTR model) and assess nodes with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

- COX1 Marker Tree: Align only the universal COX1 barcode region. Construct the tree using the same maximum likelihood method and bootstrap parameters as for the concatenated PCGs.

Step 5: Comparative Assessment

- Calculate topological differences between trees using the normalized Robinson-Foulds distance (e.g., with the

phangornpackage in R). - Assess the preservation of established taxonomic groups by calculating the percentage that form monophyletic clades in each tree (e.g., using the

apepackage in R).

- Calculate topological differences between trees using the normalized Robinson-Foulds distance (e.g., with the

This protocol describes a method for investigating the drivers of rapid evolutionary radiations, as exemplified by a study on the plant genus Aspidistra.

Step 1: Phylogenomic Sequencing

- Perform restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (RAD-seq) on a comprehensive set of species (e.g., 123 Aspidistra species) to generate genome-wide data.

Step 2: Phylogenetic Framework and Divergence Time Estimation

- Reconstruct a robust, high-resolution phylogenetic tree from the RAD-seq data.

- Estimate divergence times using a molecular dating method (e.g., BEAST) with fossil calibrations to place the radiation in a temporal context.

Step 3: Diversification Dynamics Analysis

- Analyze diversification rates through time using models (e.g., BAMM) to identify significant rate shifts and quantify speciation rates.

Step 4: Testing Abiotic and Biotic Drivers

- Use multiple statistical models to correlate speciation rates with paleoclimatic data (e.g., paleotemperature), geological events (e.g., monsoon intensification), and biotic factors (e.g., key innovations, pollination mutualisms) to infer the mechanisms driving the radiation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents, software, and databases are essential for conducting modern phylogenomic analyses.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Phylogenomics

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | High-quality genomic DNA extraction from tissue. | DNeasy Blood & Tissue DNA Kit (Qiagen) [25] [26]. |

| Library Prep Kit | Preparing genomic libraries for sequencing. | QIAseq FX Single Cell DNA Library Kit (Qiagen) [25]. |

| NGS Platform | High-throughput sequencing to generate genomic data. | Illumina NovaSeq 6000; Oxford Nanopore GridION [25] [26]. |

| Genome Assembler | De novo assembly of sequencing reads into a genome. | Flye (for long reads) [26]; MitoZ (for mitogenomes) [25]. |

| Genome Annotation Pipeline | Predicting and annotating genes in an assembled genome. | MAKER2 pipeline [26]. |

| Sequence Aligner | Aligning sequencing reads to a reference genome. | BWA [26]; Hisat2 (for RNA-seq) [26]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool | Aligning homologous gene or protein sequences. | CLUSTAL Omega [25]. |

| Phylogenetic Software | Inferring evolutionary trees from sequence data. | raxmlGUI [25]; MLGO (for gene orders) [25]. |

| Tree Visualization Software | Displaying, annotating, and publishing phylogenetic trees. | ggtree (R package) [27]; iTOL [28]. |

| Genomic Database | Repository for published genomic and sequence data. | NCBI GenBank [25] [26]. |

Visualizing Phylogenetic Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams, created using the DOT language, illustrate core concepts and workflows in phylogenomics.

Phylogeny Construction Workflow

Rapid Radiation Drivers

Phylogenetic Tree Layouts

Advanced Phylogenomic Workflows: From Whole Genomes to Trait Mapping

The genomics era has provided researchers with an unprecedented volume of data for reconstructing the evolutionary relationships among species. However, genomes are mosaics of discordant histories; different genomic regions can tell different evolutionary stories due to biological processes like incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), hybridization, and recombination [29] [30]. Traditional phylogenomic methods often struggle with this heterogeneity. While "genome-wide" studies are common, they typically analyze only small, pre-selected fractions of genomes, leaving vast amounts of data unused due to modeling and scalability limitations of existing tools [31]. As high-quality genomes continue to accumulate, there is an urgent need for methods that can directly infer species trees from whole-genome alignments while accounting for these pervasive patterns of discordance. In the context of studying species radiations—rapid diversification events that pose significant challenges for phylogenetic resolution—addressing these limitations is paramount for uncovering the true branching patterns of life.

The CASTER Workflow: A Coalescence-Aware Paradigm

CASTER (Coalescence-Aware Alignment-based Species Tree Estimator) represents a paradigm shift in phylogenomic analysis. It is a site-based method designed to infer species trees directly from a multiple whole-genome alignment without the need to predefine recombination-free loci [29]. This eliminates a significant and often arbitrary step in the phylogenomic pipeline.

The core innovation of CASTER is its use of site patterns—the specific arrangements of nucleotides across species at each position in a genome alignment. By analyzing these patterns directly, CASTER is statistically consistent under models of incomplete lineage sorting, a major source of phylogenetic discordance [30]. The method is computationally scalable, enabling analyses of hundreds of mammalian whole genomes with widely available computational resources [31]. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental logic and workflow of the CASTER method.

Performance Benchmarking: CASTER vs. State-of-the-Art Alternatives

To validate its performance, CASTER has been rigorously tested against other leading methods in both simulated and real biological datasets. The benchmarks evaluate accuracy under various evolutionary scenarios and computational scalability.

Accuracy Under Simulated Evolutionary Conditions

Extensive simulations based on the Hudson model (incorporating a species tree and recombination) were conducted to benchmark CASTER against alternatives. The table below summarizes key quantitative results from these simulations, which tested conditions like varying mutation rates and population sizes [32].

Table 1: Benchmarking Accuracy on Simulated Datasets (SR201)

| Simulation Condition | Number of Taxa | Key Comparative Finding | Notable Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default (Diploid) | 200 ingroup + 1 outgroup | CASTER demonstrated high accuracy in species tree inference [32]. | Robust performance under standard conditions. |

| 0.1X Mutation Rate | 200 ingroup + 1 outgroup | CASTER maintained accuracy where other methods may struggle with reduced signal [32]. | Effective with lower mutation rates. |

| 10X Population Size | 200 ingroup + 1 outgroup | CASTER performed well under conditions amplifying incomplete lineage sorting [32]. | Superior handling of deep coalescence. |

Scalability and Computational Efficiency

A critical advantage of CASTER is its ability to handle datasets of a scale that is prohibitive for many existing methods. The following table compares CASTER's capabilities with other types of phylogenetic tools.

Table 2: Comparative Tool Performance and Scalability

| Tool / Category | Methodological Approach | Typical Data Input | Scalability & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASTER | Site-based, Coalescence-aware | Whole-Genome Alignment | Scalable to hundreds of mammalian genomes; faster and more accurate in tests with recombining genomes [30]. |

| VeryFastTree (VFT4) | Maximum Likelihood (Heuristic) | Gene/Transcript Alignments | Builds a tree from 1 million sequences in ~36 hours; optimized for massive alignments but not whole-genome coalescent modeling [33]. |

| RAxML, IQ-TREE | Maximum Likelihood | Concatenated Loci / Genes | Leading tools for phylogenomics but struggle with convergence on datasets of ~10,000 sequences and are not designed for whole-genome alignments [33]. |

| Alignment-Free (AF) Methods | k-mer statistics, word counts | Unaligned Sequences | Scalable for whole-genome phylogenetics but face challenges with horizontal gene transfer and recombination; accuracy can vary [34]. |

Experimental Protocols for Phylogenomic Benchmarking

The experimental procedures used to validate CASTER provide a template for rigorous phylogenomic tool assessment. The core protocol involves:

- Data Simulation: Using scripts (e.g.,

simulate_SR201_10X_population.py) to generate evolving sequences under a known species tree model with controlled parameters, including mutation rate, population size, and recombination. This creates a ground truth for accuracy measurement [32]. - Alignment Processing: The simulated sequences are formatted into whole-genome alignments, which serve as the primary input for CASTER and other methods in the comparison.

- Tree Inference and Comparison: CASTER and benchmarked tools (e.g., ASTRAL-III, other site-based methods) are run on the alignments. The resulting species trees are compared to the true simulated tree using metrics like Robinson-Foulds distance to quantify topological accuracy [34] [32].

- Biological Dataset Application: To complement simulations, the method is applied to real, well-studied genomic datasets (e.g., from birds and mammals) to verify that it recovers known or biologically plausible relationships [29] [32].

The Researcher's Toolkit for Phylogenomic Analysis

Implementing modern phylogenomic methods like CASTER requires a suite of data and computational resources. The table below details key reagents and tools essential for this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Tools for Phylogenomics

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Relevance to CASTER & Phylogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Whole-Genome Alignment | A computational alignment of orthologous genomic sequences across multiple species. | The primary input data format for the CASTER method [29]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A network of computers providing massive parallel processing capabilities. | Necessary for analyzing datasets comprising hundreds of whole genomes in a feasible time [31]. |

Simulation Scripts (e.g., simulate_SR201.py) |

Computer programs that generate synthetic genomic data under evolutionary models. | Used for benchmarking method performance and accuracy under known conditions [32]. |

| Benchmarking Datasets (e.g., SR201, Avian, Mammal) | Curated genomic alignments, both simulated and biological, with known or well-established phylogenies. | Serve as standards for validating and comparing the performance of phylogenetic tools [32]. |

| ASTRAL-III | A leading method for species tree inference from a set of pre-computed gene trees. | A key alternative to CASTER used in performance comparisons; represents a different "two-step" philosophy [29] [32]. |

Implications for the Study of Species Radiations

The development of CASTER has profound implications for resolving the complex evolutionary histories characteristic of species radiations. Its ability to leverage information from entire genomes, without filtering out regions of discordance, allows it to more accurately capture the true species tree while simultaneously revealing the genomic mosaic of historical recombination and ILS [29]. This provides a powerful tool for testing hypotheses about rapid diversification. The per-site scores generated by CASTER can pinpoint specific genomic regions that deviate from the species tree, offering a window into the micro-evolutionary processes—such as selection, hybridization, and introgression—that drive macro-evolutionary patterns [29] [30]. While future work will aim to incorporate branch lengths and expand model assumptions, CASTER currently stands as a transformative tool, poised to unlock discoveries regarding how evolution has shaped the genomes and relationships of rapidly radiating lineages.

Leveraging Phylogenetic Genotype-to-Phenotype (PhyloG2P) Mapping to Uncover Loci of Repeated Evolution

Phylogenetic Genotype-to-Phenotype (PhyloG2P) mapping represents an emerging paradigm in comparative phylogenomics that leverages evolutionary relationships to decipher the genetic basis of traits across species. These methods utilize phylogenetic trees to link genotypic variation with phenotypic divergence, enabling researchers to investigate traits that vary between species where traditional crossing experiments are impossible [35]. The statistical power of PhyloG2P approaches derives primarily from replicated evolution—the independent evolution of similar phenotypes in phylogenetically distinct lineages in response to common selective pressures [36]. This framework provides natural experiments that allow researchers to distinguish genotype-phenotype correlations from lineage-specific genetic changes unrelated to the trait of interest.

In the context of species radiations research, PhyloG2P methods offer powerful tools for identifying genomic regions associated with adaptive traits that underlie diversification processes. By analyzing multiple independent evolutionary transitions, these approaches can reveal whether similar phenotypic adaptations arise through identical genetic mechanisms or through different genetic pathways—a central question in evolutionary biology [35]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of major PhyloG2P methodologies, their experimental requirements, and their applications in uncovering loci involved in repeated evolution.

Comparative Framework: PhyloG2P Method Categories

PhyloG2P methods can be categorized into three primary approaches based on the type of genetic change they detect: methods identifying specific amino acid substitutions, methods detecting changes in evolutionary rates, and methods analyzing gene duplication and loss patterns. Each approach possesses distinct strengths, limitations, and applicability depending on the biological context and genetic mechanisms underlying trait variation.

Table 1: Comparison of Major PhyloG2P Method Categories

| Method Category | Genetic Mechanism Detected | Data Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Substitutions | Replicated changes at individual codon positions | Genome sequences, codon alignments, phenotype data | High resolution to specific causal variants; Clear biological interpretation | Limited to coding regions; Misses regulatory changes |

| Evolutionary Rate Changes | Shifts in selective pressure in genetic elements | Gene sequences, phenotype data, phylogenetic tree | Can detect selection in non-coding regions; Works with polygenic traits | Does not identify specific variants; Statistical power requires multiple lineages |

| Gene Duplication/Loss | Presence/absence patterns of genetic elements | Genome assemblies, gene annotations, phenotype data | Identifies structural variants; Captures gene family evolution | Limited to detectable structural changes; Misses point mutations |

Methods Based on Replicated Amino Acid Substitutions

Methods focusing on amino acid substitutions identify genotype-phenotype associations by detecting individual codon positions that have undergone repeated changes correlated with phenotypic transitions. These approaches are particularly powerful for identifying specific causal variants when the same amino acid change occurs independently in multiple lineages possessing the trait of interest [37]. The fundamental principle involves scanning aligned coding sequences across a phylogeny to identify sites where non-synonymous substitutions consistently coincide with phenotypic changes.

Experimental Protocol for Amino Acid Substitution Methods:

- Data Collection: Obtain genome sequences and phenotypic data for a minimum of 10-15 species with independent evolutionary origins of the trait of interest, plus appropriate outgroups without the trait [36].

- Sequence Alignment: Perform multiple sequence alignment of coding regions using tools such as ClustalW, BAli-Phy, or Geneious [38].

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Construct a species tree using maximum likelihood (IQ-TREE, RAxML) or Bayesian (BEAST) methods [38].

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Infer ancestral phenotypic states and ancestral amino acid sequences using parsimony, maximum likelihood, or Bayesian approaches.

- Substitution Pattern Analysis: Identify amino acid positions that show statistically significant association between substitution events and phenotypic transitions using specialized software (e.g., Caastools) [37].

- Validation: Test identified variants in experimental systems (e.g., site-directed mutagenesis) when possible to confirm functional effects.

The power of these methods increases with the number of independent evolutionary transitions and the conservation of the affected genomic position across lineages. However, they may miss associations when different mutations within the same gene or regulatory region produce similar phenotypic effects [35].

Methods Detecting Changes in Evolutionary Rates

Rate-based PhyloG2P methods identify genetic elements whose evolutionary rates have shifted in association with phenotypic changes. These approaches operate on the principle that transitions to new phenotypic states may alter selective pressures on genes involved in the trait, resulting in accelerated or decelerated evolutionary rates [39]. Unlike substitution-based methods, rate-based approaches can detect associations even when different specific mutations underlie the phenotypic change across lineages.

Experimental Protocol for Evolutionary Rate Methods:

- Gene Tree Construction: Generate gene trees for all orthologous genes across the study species.

- Evolutionary Rate Estimation: Calculate evolutionary rates for each branch in the species phylogeny using tools like RERconverge [35].

- Phenotype Mapping: Map phenotypic data onto the phylogeny, identifying branches where transitions occurred.

- Correlation Testing: Statistically test for associations between evolutionary rate shifts and phenotypic transitions using phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) or similar methods.

- Background Rate Correction: Account for species-specific variation in evolutionary rates and phylogenetic non-independence.

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Perform pathway analysis on genes showing significant rate-trait associations to identify biological processes.

These methods are particularly valuable for complex traits potentially influenced by many genetic loci and for detecting selection in non-coding regulatory regions [39]. They can identify genes experiencing relaxed constraint or positive selection associated with phenotypic gains or losses.

Methods Analyzing Gene Duplication and Loss

Duplication and loss methods focus on identifying genotype-phenotype associations through patterns of gene presence/absence across species. These approaches are based on the principle that gene gains (through duplication) and losses may underlie important phenotypic innovations and reductions, respectively [37]. This category of methods is particularly relevant for traits influenced by gene dosage effects or the complete absence of gene function.

Experimental Protocol for Gene Duplication/Loss Methods:

- Gene Family Identification: Cluster genes into families using orthology inference tools (OrthoDB, OMA, OrthoLoger) [40].

- Copy Number Profiling: Quantify gene copy numbers across all study species.

- Reconciliation Analysis: Reconcile gene trees with species trees to infer duplication and loss events using tools like NOTUNG.

- Association Testing: Statistically test for correlations between duplication/loss events and phenotypic transitions using phylogenetic comparative methods.

- Dating Events: Estimate the timing of duplication/loss events relative to phenotypic transitions using molecular dating approaches when possible.

These methods can reveal how gene family evolution contributes to phenotypic diversity, such as the expansion of olfactory receptors associated with specialized sensory capabilities [37].

PhyloG2P Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized computational workflow for PhyloG2P analyses, highlighting the parallel processing paths for different data types and the integration points for phylogenetic information:

PhyloG2P Computational Workflow

Successful implementation of PhyloG2P analyses requires specialized computational tools and resources. The table below catalogues essential research reagents and their applications in comparative phylogenomics:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for PhyloG2P

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in PhyloG2P |

|---|---|---|---|

| IQ-TREE [38] | Software | Maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference | Construction of robust species trees from sequence data |

| BEAST [38] | Software | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Dated phylogeny reconstruction and ancestral state inference |

| RERconverge [35] | Software/R package | Evolutionary rate correlation | Identifying branches and genes with rate changes associated with traits |

| Caastools [37] | Software/Toolbox | Convergent amino acid substitution identification | Detecting specific AA changes associated with phenotypic convergence |

| OrthoDB [40] | Database | Ortholog catalog | Defining gene families and orthologous groups across species |

| Geneious [38] | Software platform | Sequence analysis and visualization | Integrated environment for multiple sequence alignment and annotation |

| CoGe [41] | Web platform | Comparative genomics | Genome comparison, synteny analysis, and evolutionary inference |

| Phylo.io [40] | Web tool | Phylogenetic tree visualization | Comparing and visualizing phylogenetic trees and their support |

| Bali-Phy [38] | Software | Simultaneous alignment and tree inference | Joint inference of alignments and trees under evolutionary models |

| MegAlign Pro [38] | Software | Multiple sequence alignment | Creating and editing alignments for phylogenetic analysis |

Critical Methodological Considerations

Trait Definition and Measurement

The definition and measurement of traits fundamentally impact PhyloG2P analysis outcomes. Research demonstrates that treating continuous traits as continuous rather than binary categories increases statistical power [36]. Similarly, expanding categorical definitions (e.g., from carnivore/non-carnivore to herbivore/omnivore/carnivore) enhances detection of genetic associations [35]. Compound traits like "marine adaptation" present particular challenges, as they comprise multiple simpler traits that may not be shared across all lineages exhibiting the compound phenotype [36]. For optimal results, researchers should deconstruct compound traits into their constituent elements when possible.

Phylogenetic Scale and Replication

The phylogenetic scale of analysis significantly influences the detection of genotype-phenotype associations. Studies encompassing appropriate phylogenetic breadth can reveal intermediate phenotypes and prevent oversimplification of trait patterns [35]. The number of independent evolutionary transitions limits statistical power, with most methods requiring a minimum of 3-5 replicated origins for robust inference [39]. Additionally, the genetic basis of replication may vary across phylogenetic scales—identical mutations may underlie phenotypic convergence in closely related species, while different genetic mechanisms may operate in distantly related lineages [36].

Integration of Complementary Data

No single PhyloG2P method can detect all potential genotype-phenotype associations, as different approaches target distinct genetic mechanisms [39]. Substitution methods excel at identifying specific causal variants but miss regulatory changes, while rate-based methods detect selective signatures but not specific mutations. Consequently, applying multiple complementary methods increases the comprehensiveness of detected associations [37]. Future methodological developments will likely integrate population-level variation, epigenetic information, and environmental data to provide more nuanced understanding of evolutionary processes [39].

PhyloG2P methods represent powerful approaches for uncovering genetic loci underlying repeated evolutionary transitions, particularly in the context of species radiations research. Each methodological category offers distinct advantages: amino acid substitution methods provide high resolution to specific causal variants, evolutionary rate methods detect selective signatures across coding and non-coding regions, and duplication/loss methods identify structural variants associated with phenotypic innovation. The most comprehensive insights emerge from applying multiple complementary approaches while carefully considering trait definition, phylogenetic scale, and evolutionary replication. As these methods continue to develop and integrate additional biological data layers, they promise to dramatically expand our understanding of the genetic architecture of adaptation and diversification across the tree of life.

The accurate reconstruction of species evolutionary history from genomic data is a fundamental goal in phylogenomics. This endeavor is particularly challenging during rapid radiations—brief periods of extensive speciation—where short internal branches amplify the discordance between gene trees and the species tree. This incongruence, primarily caused by incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), necessitates sophisticated analytical approaches. The two predominant strategies for species tree inference are coalescent-based methods, which explicitly model ILS, and concatenation, which combines all genetic data into a single supermatrix. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their performance in resolving rapid radiations, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

The multi-species coalescent (MSC) model provides a population-genetic framework for understanding gene tree heterogeneity. It describes the evolution of individual genes within a population-level species tree, modeling the time since ancestral coalescence as a backward-time Markov process. Under the MSC, lineages coalesce within ancestral populations according to a Poisson process, resulting in a probability distribution over all possible gene trees for a given species tree [42]. ILS occurs when the coalescence of gene lineages predates speciation events, leading to gene tree topologies that differ from the species tree topology. In rapid radiations, short successive branches increase the probability of ILS, sometimes placing the most likely gene tree topology in an "anomaly zone" where it differs from the species tree [43] [44].

The Concatenation Approach