Comparative Phylogenetic Analysis Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs), statistical techniques that use evolutionary relationships to test hypotheses about trait evolution and diversification.

Comparative Phylogenetic Analysis Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs), statistical techniques that use evolutionary relationships to test hypotheses about trait evolution and diversification. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts from phylogeny reconstruction to advanced analytical frameworks like Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) and Bayesian inference. The scope addresses core intents: exploring the principles of PCMs, detailing methodological applications, troubleshooting common challenges, and validating analyses through comparative approaches. This guide serves as a critical resource for applying robust evolutionary context to biomedical research, from target identification to understanding disease mechanisms.

Understanding the Evolutionary Framework: Core Principles of Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis

Defining Phylogenetic Comparative Methods (PCMs) and Their Role in Evolutionary Biology

Phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) are a suite of statistical techniques that use information on the historical relationships of lineages (phylogenies) to test evolutionary hypotheses [1]. These methods have revolutionized evolutionary biology by providing a framework to understand how species' traits evolve over time, while accounting for the fact that closely related species share traits not necessarily due to independent evolution but because of common ancestry—a phenomenon known as phylogenetic non-independence [1] [2]. The core realization that species are not independent data points due to their shared evolutionary history inspired the development of explicitly phylogenetic comparative methods, with Joseph Felsenstein's 1985 paper on phylogenetically independent contrasts marking a foundational milestone [1] [2].

PCMs enable researchers to distinguish between similarities resulting from common ancestry versus those arising from independent adaptive evolution [1]. These approaches complement other evolutionary study methods, such as research on natural populations, experimental evolution, and mathematical modeling [1]. By modeling evolutionary processes occurring over extended timescales, PCMs provide critical insights into macroevolutionary questions—once primarily the domain of paleontology—including patterns of diversification, adaptation, and constraint across entire clades [1] [3] [2].

Foundational Principles and Key Methods

Core Statistical Framework

PCMs operate on the principle that trait data from related species cannot be treated as independent observations in statistical analyses. Standard statistical tests assume data independence, but phylogenetic relationships create a covariance structure in trait data—closely related species are expected to have more similar trait values than distantly related species due to their shared evolutionary history [1] [2]. PCMs incorporate this phylogenetic covariance explicitly into statistical models using a variance-covariance matrix derived from the phylogenetic tree, which encodes expected similarities among species based on their evolutionary relationships [1].

Table 1: Key Evolutionary Models Used in PCMs and Their Applications

| Model | Underlying Evolutionary Process | Typical Applications | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brownian Motion | Random walk; genetic drift or unpredictable selection | Trait evolution without clear directional trend; phylogenetic signal estimation | Rate of diffusion (σ²) |

| Ornstein-Uhlenbeck | Stabilizing selection with constraint | Adaptation to specific selective regimes; tracking of optimal trait values | Selection strength (α), optimum (θ), constraint |

| Pagel's λ | Varying degrees of phylogenetic signal | Testing how much trait covariation follows phylogenetic expectations | Scaling parameter (λ) measuring phylogenetic signal |

Essential PCM Techniques

Phylogenetically Independent Contrasts (PIC)

Phylogenetically independent contrasts, developed by Felsenstein in 1985, was the first general statistical method that could use any arbitrary phylogenetic topology and specified branch lengths [1]. The method transforms original species trait data into values that are statistically independent and identically distributed, using phylogenetic information and an assumed Brownian motion model of trait evolution [1]. The algorithm computes differences in trait values between sister taxa or nodes, standardized by their branch lengths, creating "contrasts" that can be analyzed with standard statistical approaches [1] [2]. PIC is particularly valuable for testing relationships between traits while accounting for phylogeny, such as investigating allometric relationships or evolutionary correlations [1].

Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS)

Phylogenetic generalized least squares is currently the most commonly used PCM [1]. This approach extends generalized least squares regression by incorporating the expected phylogenetic covariance structure into the error term [1]. Whereas standard least squares assumes residuals are independent and identically distributed, PGLS assumes they follow a multivariate normal distribution with covariance matrix V, which reflects the phylogenetic relationships and an specified evolutionary model [1]. PGLS can test for relationships between two or more variables while accounting for phylogenetic non-independence, and can incorporate various evolutionary models including Brownian motion, Ornstein-Uhlenbeck, and Pagel's λ [1]. When a Brownian motion model is used, PGLS produces identical results to independent contrasts [1].

Bayesian and Monte Carlo Approaches

Bayesian phylogenetic methods and phylogenetically informed Monte Carlo simulations provide powerful alternatives for comparative analysis [1] [4]. These approaches can incorporate uncertainty in phylogenetic relationships, evolutionary parameters, and trait estimates [5]. Bayesian methods use Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to estimate posterior distributions of parameters, allowing researchers to integrate over uncertainty in phylogeny or model parameters [4]. Monte Carlo simulation approaches, as proposed by Martins and Garland in 1991, generate numerous datasets consistent with the null hypothesis while mimicking evolution along the relevant phylogenetic tree, creating phylogenetically correct null distributions for hypothesis testing [1].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Implementing PGLS Analysis

Objective: To test for a relationship between two continuous traits while accounting for phylogenetic non-independence.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Phylogenetic tree of study taxa in Newick or Nexus format

- Trait dataset with measurements for each taxon

- Statistical software with PCM capabilities (R with packages ape, nlme, phytools, or caper)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Compile trait data into a dataframe with species as rows and traits as columns. Ensure trait data match terminal taxa in the phylogeny.

- Phylogeny Preparation: Import phylogenetic tree and check for ultrametric properties if using Brownian motion or Ornstein-Uhlenbeck models.

- Model Selection: Choose an evolutionary model based on biological understanding and statistical fit:

- Brownian motion for neutral evolution or drift

- Ornstein-Uhlenbeck for constrained evolution

- Pagel's λ for testing phylogenetic signal strength

- PGLS Implementation: Fit the model using phylogenetic generalized least squares:

- Specify the regression formula (e.g., trait1 ~ trait2)

- Define the correlation structure based on the phylogeny

- Estimate parameters using maximum likelihood or restricted maximum likelihood

- Model Diagnostics: Check residuals for phylogenetic signal using Pagel's λ or other tests

- Interpretation: Evaluate significance of regression coefficients while considering phylogenetic structure

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If convergence issues arise, simplify the evolutionary model

- For missing data, consider multiple imputation approaches

- If phylogenetic signal is negligible (λ ≈ 0), standard regression may be appropriate

Protocol 2: Ancestral State Reconstruction

Objective: To infer trait values at internal nodes of a phylogeny, including at the root.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Time-calibrated phylogenetic tree

- Trait data for extant taxa

- Software: R (phytools, ape), BayesTraits, BEAST

Procedure:

- Tree and Data Input: Import ultrametric tree and trait data, ensuring matching taxon names

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate evolutionary model (typically Brownian motion for continuous traits, Markov k-state model for discrete traits)

- Reconstruction Method Selection:

- For maximum likelihood: Use squared-change parsimony or ML estimation

- For Bayesian approaches: Use MCMC methods to sample ancestral states

- Analysis Execution: Run reconstruction algorithm with appropriate parameters

- Uncertainty Assessment: Calculate confidence intervals (ML) or posterior densities (Bayesian) for node estimates

- Visualization: Project reconstructed states onto phylogeny with color coding or branch tracing

Applications:

- Locating evolutionary origins of key traits (e.g., endothermy in mammals) [1]

- Testing hypotheses about evolutionary sequences

- Identifying instances of convergent evolution

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Trees | Framework for comparative analyses; represents evolutionary relationships | Time-calibrated trees from molecular dating; fossil-calibrated phylogenies |

| Trait Datasets | Phenotypic, ecological, or behavioral measurements for analysis | Morphometrics, physiological measurements, ecological preferences |

| Sequence Data | Molecular data for tree construction or evolutionary inference | DNA/RNA sequences for phylogenetic reconstruction |

| Bayesian MCMC Algorithms | Statistical inference incorporating uncertainty | MrBayes, BEAST, BayesTraits for parameter estimation |

| Model Selection Criteria | Choosing among alternative evolutionary models | AIC, BIC, Bayes factors for model comparison |

| PCM Software Packages | Implementing statistical analyses | R packages (ape, phytools, nlme); standalone software (PAUP*) |

Applications in Evolutionary Biology and Beyond

Biological Research Applications

PCMs address diverse evolutionary questions across biological disciplines [1]:

- Allometric Scaling: Investigating how organ size relates to body size across species (e.g., brain mass vs. body mass) [1]

- Clade Comparisons: Testing whether different evolutionary lineages differ in phenotypic traits (e.g., cardiovascular differences between canids and felids) [1]

- Adaptive Hypotheses: Examining whether ecological or behavioral characteristics correlate with phenotypes (e.g., home range size in carnivores vs. herbivores) [1]

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Inferring characteristics of extinct ancestors (e.g., origin of endothermy in mammals) [1]

- Phylogenetic Signal: Quantifying how strongly traits "follow phylogeny" and whether some trait types are more evolutionarily labile [1]

- Life History Evolution: Analyzing trade-offs in life history strategies across the fast-slow continuum [1]

Case Study: Human Brain Evolution

Miller et al. (2019) used PCMs to test hypotheses about human brain evolution, addressing whether the human brain is exceptionally large after accounting for allometric expectations and phylogenetic relationships [6]. Using Bayesian phylogenetic methods with data from both extant primates and fossil hominins, they demonstrated that:

- A distinct shift in brain-body scaling occurred as hominins diverged from other primates

- Another shift occurred as humans and Neanderthals diverged from other hominins

- Hominins showed a pattern of directional and accelerating evolution toward larger brains

- Contrary to widespread assumptions, the human neocortex is not exceptionally large relative to other brain structures—instead, increases occurred across multiple brain components [6]

This study exemplifies how PCMs can test long-standing hypotheses while accounting for phylogenetic relationships and body size scaling, providing insights that contradict prior assumptions based on non-phylogenetic analyses [6].

Cross-Disciplinary Extensions

PCMs have expanded beyond evolutionary biology to inform research in:

- Linguistics: Studying the evolution of color term systems across language families, testing whether languages gain and lose color terms in constrained patterns [4]

- Anthropology: Investigating cultural evolution and transmission of traits across human societies [7]

- Cancer Biology: Analyzing the evolutionary relationships of cancer subtypes and their mutational profiles to understand tumor progression [3]

- Conservation Biology: Informing prioritization strategies based on evolutionary distinctiveness

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Multivariate Comparative Methods

Recent methodological advances have extended PCMs to analyze multiple traits simultaneously [8]. Multivariate phylogenetic comparative methods face unique challenges, including:

- High-Dimensionality: As the number of traits increases, evolutionary covariance matrices become ill-conditioned and model misspecification increases [8]

- Trait Interdependence: Methods assuming independence among trait dimensions exhibit nearly 100% model misspecification rates [8]

- Orientation Dependence: Some multivariate approaches produce different results simply based on data rotation (e.g., principal component analysis) [8]

Current recommendations favor algebraic generalizations of standard phylogenetic comparative approaches that use traces of covariance matrices, as these are insensitive to trait covariation levels, dimensionality, and data orientation [8].

Phylogenetic Tree Uncertainty

Incorporating phylogenetic uncertainty represents a critical consideration in comparative analyses [5]. Two primary approaches address this:

- Bayesian Methods: Sample across tree space and integrate comparative analyses over phylogenetic uncertainty using MCMC algorithms [5] [4]

- Bootstrap Methods: Generate multiple trees through resampling and repeat comparative analyses across these trees [5]

The mathematical framework for incorporating phylogenetic uncertainty in Bayesian methods can be represented as:

[ P(\theta | D) = \int P(\theta | G) P(G | D) dG ]

Where (\theta) represents parameters of interest, (D) is the data, and (G) is the phylogenetic tree [5].

Methodological Limitations and Assumptions

PCMs rely on several important assumptions that researchers must consider:

- Accurate Phylogeny: Results depend on the accuracy of the phylogenetic hypothesis and branch length estimates

- Evolutionary Models: Methods assume the specified model adequately captures the evolutionary process

- Stationarity: Many methods assume constant evolutionary rates or processes across the tree

- Data Quality: Measurement error and within-species variation can impact parameter estimates

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The field of phylogenetic comparative methods continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions:

- Integration with Genomics: Combining PCMs with genomic data to identify genetic bases of macroevolutionary patterns

- Improved Multivariate Methods: Developing robust approaches for high-dimensional trait data [8]

- Complex Evolutionary Models: Creating more realistic models that incorporate heterogeneity in evolutionary processes across lineages

- Integration with Paleontology: Combining neontological and fossil data to create more comprehensive evolutionary narratives [1] [2]

- Machine Learning Applications: Leveraging computational advances for pattern detection in large phylogenetic datasets [5]

As these methodological advances continue, phylogenetic comparative methods will remain essential tools for connecting microevolutionary processes with macroevolutionary patterns, addressing fundamental questions about life's diversity and evolutionary history [2].

Phylogenetic trees are fundamental tools in evolutionary biology, providing a graphical representation of the evolutionary relationships among species, genes, or other biological entities. For researchers and drug development professionals engaged in comparative phylogenetic analysis, a precise understanding of tree anatomy is crucial for accurate interpretation and communication of evolutionary hypotheses. This knowledge forms the basis for investigating pathogen evolution, tracing the origins of drug resistance, and understanding functional divergence in protein families. This application note details the core components and types of phylogenetic trees, providing standardized protocols for their visualization and annotation within a research context.

The Fundamental Anatomical Components

A phylogenetic tree is composed of a branching structure that illustrates the inferred evolutionary relationships. Its basic elements include branches, nodes, and labels, each conveying specific evolutionary information [9] [10].

- Branches: Branches represent the evolutionary lineage connecting ancestors to their descendants. Their length is often proportional to the amount of evolutionary change, which can be the number of substitutions per site (genetic distance) or an estimate of time [9] [11]. Some software, like ggtree, allows branches to be colored or scaled based on numerical variables such as evolutionary rates or dN/dS values, facilitating the integration of diverse data types [9] [11].

- Nodes: Nodes are the points where branches meet or terminate and represent taxonomic units at specific points in evolutionary history. They are categorized as follows [10]:

- Root Node: The most recent common ancestor of all entities represented in the tree. It provides the direction of evolutionary time and is a defining feature of rooted trees [10] [12].

- Internal Nodes: Points where two or more branches meet within the tree. They represent inferred ancestral sequences or species at those branching points [10].

- Terminal Nodes (Tips): The endpoints of the tree, representing the operational taxonomic units (OTUs)—such as the sampled species, sequences, or strains—that were used to construct the phylogeny [10].

- Taxon Labels: The names assigned to the terminal nodes, identifying the biological entities at the tips of the tree [9].

Table 1: Core Components of a Phylogenetic Tree

| Component | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Root Node | The most recent common ancestor of all taxa in the tree. | Provides directionality to evolution; allows for the determination of ancestral/derived states [10] [12]. |

| Internal Node | A hypothetical common ancestor where a lineage splits. | Represents a speciation or duplication event; can be annotated with support values (e.g., bootstrap) [10]. |

| Terminal Node (Tip) | The sampled species, genes, or sequences under study. | Represents the real data used for the phylogenetic inference [10]. |

| Branch | The line connecting nodes, representing a lineage. | Length often signifies the amount of evolutionary change (time or substitutions) [9] [11]. |

Diagram 1: Anatomy of a Rooted Phylogenetic Tree

Rooted vs. Unrooted Trees

A critical distinction in phylogenetic analysis is between rooted and unrooted trees, which dictates the type of evolutionary inferences that can be drawn.

- Rooted Trees: A rooted tree contains a single designated root node, which represents the most recent common ancestor of all the descendants in the tree. The root gives the tree a direction of time, allowing for the interpretation of evolutionary paths from ancestor to descendant. All nodes with descendants represent inferred common ancestors. The root is essential for determining the order of evolutionary events and the direction of character state changes [10] [12].

- Unrooted Trees: An unrooted tree illustrates the branching relationships and topological structure among the taxa but does not define a root or point of origin. It shows the relatedness of the terminal nodes without making assumptions about ancestry. Unrooted trees are valuable for visualizing relationships without an a priori assumption about the direction of evolution and are often used when an outgroup is not available or appropriate [12].

Table 2: Comparison of Rooted and Unrooted Trees

| Feature | Rooted Tree | Unrooted Tree |

|---|---|---|

| Root Node | Present and defined [12]. | Absent [12]. |

| Evolutionary Direction | Implied (from root to tips) [12]. | Not specified [12]. |

| Common Ancestor | Identified for all clades [10]. | Not explicitly identified. |

| Common Use Cases | Inferring evolutionary history, ancestral state reconstruction, dating divergence times. | Modeling evolutionary relationships where the root is unknown; network analysis [13]. |

| Common Layouts | Rectangular, circular, slanted, fan [9] [11]. | Unrooted (equal-angle or equal-daylight algorithms) [9] [14]. |

Diagram 2: Structural Comparison of Rooted and Unrooted Trees

Visualization and Annotation Tools for Research

Modern phylogenetic research requires robust software for visualizing and annotating trees with diverse associated data. Tools such as ggtree (R) and iTOL (web) are specifically designed for this purpose.

- ggtree (R Package): An R package that extends the ggplot2 library, providing a programmable and highly customizable platform for tree visualization and annotation [9] [11]. It supports a grammar of graphics approach, allowing users to build complex annotated figures by freely combining multiple layers of annotation data onto a tree [9]. Its key features include:

- Layouts: Supports rectangular, circular, slanted, fan, and unrooted layouts, among others [9] [11].

- Annotation: Enables mapping of various data types (e.g., evolutionary rates, trait data) to tree features like branch color, node shape, and tip labels through geometric layers (

geom_tippoint,geom_hilight,geom_cladelab) [9]. - Data Integration: Seamlessly integrates with the

treeiopackage to import and combine analysis outputs from diverse software (BEAST, RAxML, etc.) with tree objects [9].

- iTOL (Interactive Tree Of Life): A web-based tool for the display, management, and annotation of phylogenetic trees [14]. It is user-friendly and allows for interactive customization.

- Display Modes: Includes rectangular, circular, slanted, and unrooted (both equal-angle and equal-daylight algorithms) modes [14].

- Annotation: Users can manually or automatically annotate trees with datasets to color branches, highlight clades, and display various data charts (e.g., bar charts, heatmaps) directly on the tree [14].

- Workflow: A typical workflow involves uploading a tree file (e.g., Newick, Nexus), exploring visualization functions, adding annotations, and exporting publication-ready figures [14].

- PhyloView: A specialized web-based tool that automatically retrieves taxonomic information for protein sequences in a tree and allows interactive coloring of branches according to any combination of taxonomic divisions. This is particularly useful for identifying taxonomic patterns or anomalies in protein families [15].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Visualization

| Tool / Resource | Function / Application | Access / Platform |

|---|---|---|

| ggtree [9] [11] | Programmable tree visualization and annotation in R; ideal for complex, data-integrated figures and reproducible research pipelines. | R/Bioconductor |

| iTOL [14] | Online, interactive annotation and management of phylogenetic trees; suitable for rapid visualization and sharing. | Web-based |

| PhyloView [15] | Automated taxonomic coloring of phylogenetic trees based on sequence identifiers. | Web-based |

| Tree File Format (Newick) [14] | Standard text-based format for representing tree topology, branch lengths, and support values. | N/A |

| NHX/MrBayes Metadata [14] | Extended format allowing incorporation of internal node IDs and various metadata for annotation. | N/A |

Experimental Protocols for Tree Handling and Annotation

Protocol 1: Visualizing and Annotating a Tree Using ggtree

This protocol outlines the steps to create and annotate a phylogenetic tree in R using the ggtree package, a powerful tool for reproducible analysis [9] [11].

Data Input and Tree Parsing:

- Import your phylogenetic tree into R. The

treeiopackage can parse various file formats (Newick, Nexus, etc.) and import associated data from software outputs like BEAST or RAxML. - Load the ggtree library.

- Import your phylogenetic tree into R. The

Basic Tree Visualization:

- Use the

ggtree()function to create a basic plot. The tree object is the primary input. - Customize the basic appearance directly within the

ggtree()call.

- Use the

Layering Annotation Data:

- Annotate the tree by adding layers using the

+operator. Key annotation layers include: - Labels: Add tip labels with

geom_tiplab(). - Nodes: Highlight nodes with

geom_nodepoint()orgeom_tippoint(). - Clades: Highlight a clade with

geom_hilight()or annotate it withgeom_cladelab(). - Evolutionary Distance: Display a scale bar with

theme_tree2().

- Annotate the tree by adding layers using the

Advanced Annotation (Color by Branch Length):

- Map variables to aesthetic properties like branch color. This requires using the

aes()function.

- Map variables to aesthetic properties like branch color. This requires using the

Protocol 2: Interactive Annotation and Export Using iTOL

This protocol describes a standard workflow for using the Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) platform to annotate and export trees [14].

Tree Upload:

- Navigate to the iTOL website.

- Upload your tree file (in Newick, Nexus, PhyloXML, or Jplace format) either anonymously or into your user account for management.

Basic Tree Customization:

- In the "Basic" controls tab, select the desired Display Mode (e.g., Rectangular, Circular, Unrooted).

- Adjust basic parameters such as Rotation, Arc (for circular trees), and toggle Branch lengths to display a phylogram or cladogram.

- Use the "Advanced" tab to fine-tune label fonts, branch widths, and colors.

Adding Annotations:

- Use the "Datasets" tab to upload annotation files or utilize the manual annotation tool.

- To interactively highlight a clade, click on a branch to open the node functions menu. From there, you can select options to color the branch or add a colored range to highlight the entire clade.

- For taxonomic coloring or complex datasets, prepare and upload dedicated dataset files as per iTOL's documentation.

Tree Export:

- Once the tree is annotated, use the "Export" tab to generate a publication-quality image.

- Choose the output format (e.g., PNG, PDF, SVG), adjust the resolution and image dimensions, and download the final figure.

Advanced Applications in Comparative Analysis

Understanding tree anatomy enables sophisticated analyses in comparative phylogenetics. For instance, the ColorPhylo algorithm addresses the challenge of visualizing complex taxonomic relationships by automatically generating a color code where color proximity reflects taxonomic proximity [16]. This method uses a dimensionality reduction technique to map taxonomic distances onto a 2D color space, providing an intuitive overlay for any phylogenetic tree and revealing patterns that might be missed with arbitrary color assignment [16]. Furthermore, visualizing phylogenetic trees with associated data—such as geographic location, host species, or genetic variants—is critical for identifying evolutionary patterns in multidisciplinary studies, including those tracking virus evolution or investigating the emergence of drug-resistant strains [9].

Comparative phylogenetic analysis is a cornerstone of modern evolutionary biology, functional genomics, and drug discovery. The pipeline from raw biological sequences to a phylogenetic tree representing evolutionary relationships enables researchers to trace the ancestry of genes, identify functional domains, and understand the evolutionary pressures shaping organisms. This process involves multiple critical steps, each requiring specific computational tools and statistical methods to ensure biological accuracy. The foundational nature of this workflow means that its rigorous application is vital for generating reliable, reproducible results that can inform downstream hypotheses and experimental designs [2].

This protocol details the essential data pipeline, providing a standardized framework for researchers. We outline the procedures for sequence alignment, alignment refinement, phylogenetic tree construction, and subsequent comparative analysis. The methods described here are framed within a macroevolutionary research program, connecting evolutionary processes observable over short timescales to the broad-scale patterns seen in the tree of life [2]. By integrating these steps into a cohesive workflow, scientists can systematically investigate evolutionary relationships, predict gene function, and identify potential drug targets through the analysis of conserved regions and evolutionary signatures.

The Analytical Workflow: From Sequences to Trees

The journey from nucleotide or protein sequences to a phylogenetic tree is a multi-stage process. The logical relationship between these stages is outlined in the workflow below.

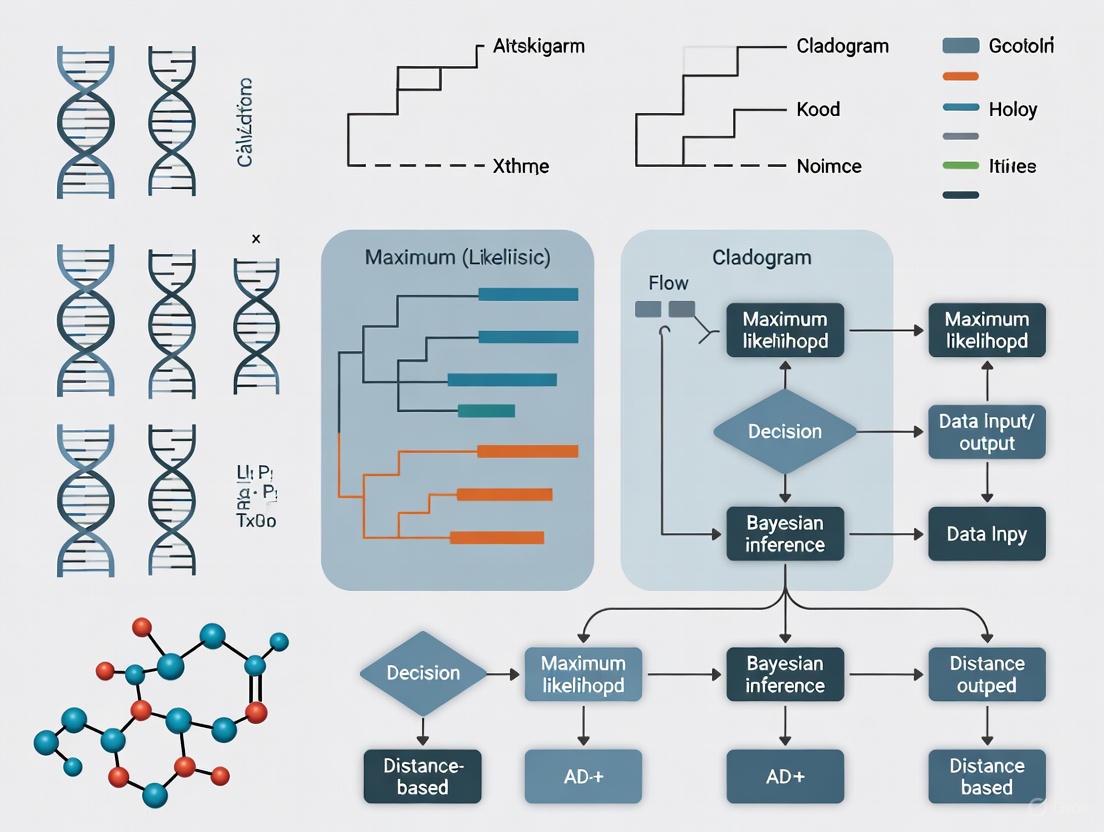

Diagram 1: The essential data pipeline for phylogenetic analysis.

Stage 1: Sequence Alignment and Quality Control

Objective: To compare and arrange biological sequences (DNA, RNA, or protein) to identify regions of similarity and difference. This step is fundamental for inferring structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships [17].

Principles: Sequence alignment works by comparing sequences nucleotide-by-nucleotide or amino acid-by-amino acid. Alignment algorithms use a combination of matches, mismatches, and gaps (representing insertions or deletions) to maximize an alignment score. Determining the degree of similarity between sequences provides a first look at potential homology [17]. For protein-coding sequences, aligning based on the translated amino acid sequence can often be more informative due to the redundancy of the genetic code, as a mutation in the DNA sequence may not change the resultant protein [17].

Protocol: Performing a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) with Clustal Omega

Clustal Omega is recommended for aligning large datasets due to its scalability and accuracy [18].

- Input Preparation: Gather your sequences in FASTA format. Ensure all sequences are in the same orientation (5' to 3' for DNA/RNA).

- Command Execution:

-i: Specifies the input FASTA file.-o: Specifies the output alignment file.--output-fmt=fa: Sets the output format to FASTA (other options includeclustal,msf).--force: Overwrites an existing output file.

- Accuracy Refinement (Optional): For improved accuracy, use the iterative refinement option:

- Quality Assessment: Visually inspect the alignment using software like AliView or MEGA. Check for well-aligned conserved regions and verify that gap placements are biologically plausible.

Stage 2: Alignment Curation and Refinement

Objective: To improve the phylogenetic signal in the alignment by removing or trimming ambiguous regions that may introduce noise into the tree-building process.

Protocol: Manual Curation and Trimming

- Visual Inspection: Open the alignment file from Stage 1 in a viewer like AliView.

- Identify Poorly Aligned Regions: Look for columns with a high density of gaps and sequences with uniquely long insertions.

- Trim the Alignment: Use a tool like TrimAl to automate the removal of poorly aligned positions.

-automated1: Applies a pre-defined trimming strategy suitable for phylogenetic analysis.

Stage 3: Phylogenetic Tree Building

Objective: To infer the evolutionary relationships among the sequences by constructing a phylogenetic tree from the curated multiple sequence alignment.

Principles: Tree-building methods can be broadly classified into distance-based, maximum likelihood (ML), and Bayesian inference methods. For large datasets, approximate maximum likelihood methods like those implemented in FastTree offer a good balance between speed and accuracy [19].

Protocol: Building a Tree with FastTree

FastTree is a widely used tool for rapidly inferring approximate maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees [19].

- Input: Use the trimmed alignment from Stage 2.

- Command Execution for Nucleotide Data:

-nt: Indicates the input is nucleotide data.-gtr: Specifies the generalized time-reversible model of nucleotide evolution.

- Command Execution for Protein Data:

- By default, FastTree uses the JTT+CAT model for protein sequences.

- Output: The resulting tree file in Newick format (

tree.newick) can be used for visualization and further analysis.

Stage 4: Tree Visualization and Comparative Analysis

Objective: To interpret the phylogenetic tree and use it as a framework for testing evolutionary hypotheses using comparative methods.

Principles: Phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) use the historical relationships shown in the phylogeny to test evolutionary hypotheses while accounting for the shared ancestry of species [1]. A common initial step is to assess the phylogenetic signal, which describes the tendency for related species to resemble each other more than they resemble species drawn at random from the tree [1].

Protocol: Basic Tree Visualization with the ETE Toolkit

The Environment for Tree Exploration (ETE) toolkit is a Python library used for analyzing and visualizing trees [19].

- Python Script Example:

- Interpretation: Analyze the tree topology, branch lengths (which represent genetic change or time), and support values (e.g., bootstrap) to assess confidence in the inferred relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

A successful phylogenetic analysis relies on a suite of well-established software tools and resources. The table below catalogs the key reagents for the bioinformatician's toolkit.

Table 1: Essential Software Tools for the Phylogenetic Pipeline

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST [18] | Sequence Alignment | Compare a query sequence against a database to find regions of local similarity. | Fast heuristic algorithm; various types (blastn, blastp) for different data. |

| Clustal Omega [18] | Multiple Sequence Alignment | Generate multiple sequence alignments of large datasets. | Scalable via parallel processing; high accuracy. |

| MUSCLE [18] | Multiple Sequence Alignment | Generate accurate multiple sequence alignments for phylogenetics. | High accuracy with progressive & iterative refinement. |

| MAFFT [20] | Multiple Sequence Alignment | Generate multiple sequence alignments with high accuracy. | Offers many strategies (e.g., L-INS-i) for difficult alignments. |

| TrimAl [20] | Alignment Curation | Automatically trim unreliable regions & gaps from an MSA. | Improves phylogenetic signal-to-noise ratio. |

| FastTree [19] | Tree Building | Infer approximate maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees. | Computational efficiency for large datasets. |

| BAli-Phy [20] | Tree Building | Co-estimate phylogeny & alignment using Bayesian inference. | Joint statistical model of indels and substitutions. |

| ETE Toolkit [19] | Visualization & Analysis | Programmatically manipulate, analyze, and visualize trees. | Integrates with Python for reproducible analysis workflows. |

Advanced Applications and Scaling to Large Datasets

For standard datasets, the workflow above is sufficient. However, advanced applications, particularly those involving thousands of sequences, require specialized strategies. The following diagram and protocol describe the UPP (Ultra-large Phylogenetic Pipeline) method for scaling phylogenetic analysis.

Diagram 2: The UPP strategy for large-scale alignment.

Protocol: UPP for Large-Scale Alignment

The UPP (Ultra-large Phylogenetic Pipeline) method is designed to align datasets containing up to one million sequences, including fragmentary data [20]. Its core innovation is using an ensemble of Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to accurately place new sequences into a pre-computed "backbone" alignment.

- Backbone Selection: A random subset of sequences (e.g., 1,000 sequences) is selected from the full, ultra-large dataset to form a "backbone" [20].

- Backbone Alignment: A high-accuracy alignment method, such as an extension of PASTA that uses BAli-Phy for subset alignment, is run on this backbone subset to produce a reliable base alignment and tree [20].

- HMM Ensemble Construction: The backbone alignment is broken down into many overlapping subsets of sequences. An HMM is built from each of these subsets, creating a diverse ensemble of models [20].

- Query Sequence Alignment: For every remaining sequence in the full dataset (the "query" sequences), the best-fitting HMM from the ensemble is identified. The query sequence is then aligned to the backbone alignment using this best-scoring HMM [20].

- Final Alignment Merge: The alignments of all query sequences to the backbone are merged by transitivity, resulting in a comprehensive multiple sequence alignment for the entire ultra-large dataset [20].

This approach leverages the statistical power of Bayesian methods like BAli-Phy for the critical backbone, while the HMM ensemble makes scaling to thousands of sequences computationally feasible and highly accurate [20].

Integrating Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

Once a reliable tree is established, it serves as a scaffold for evolutionary analysis through Phylogenetic Comparative Methods (PCMs). PCMs are essential for testing hypotheses about adaptation, correlation between traits, and ancestral state reconstruction, while accounting for the non-independence of species due to shared ancestry [1].

Protocol: Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS)

PGLS is one of the most commonly used PCMs to test for a relationship between two or more continuous traits while incorporating the phylogenetic tree [1].

- Data Preparation: You will need:

- A rooted phylogenetic tree with branch lengths in Newick format.

- A dataset of trait values for the species at the tips of the tree.

- Model Selection: Choose an evolutionary model for the residual error structure. Common choices include:

- Brownian Motion (BM): Models random drift over time. When used in PGLS, this model is identical to the method of Independent Contrasts [1].

- Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU): Models trait evolution under stabilizing selection [1].

- Pagel's λ: A multilevel model used to measure and adjust for the phylogenetic signal in the residuals of the regression [1].

- Analysis Execution: PGLS can be performed using statistical software such as R with packages like

caperornlme. The analysis will co-estimate the parameters of the regression (slope, intercept) and the parameters of the evolutionary model (e.g., λ) [1]. - Interpretation: The output provides parameter estimates and p-values for the regression, which indicate whether a significant relationship exists between the traits after controlling for phylogenetic non-independence.

Table 2: Overview of Common Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Method | Primary Function | Data Type | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts (PIC) [1] | Test for correlation between traits. | Continuous | The original PCM; transforms tip data into independent contrasts. |

| Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) [1] | Regression model for trait relationships. | Continuous | The most common PCM; a flexible framework for hypothesis testing. |

| ANCESTRAL STATE RECONSTRUCTION [1] | Infer trait values at ancestral nodes. | Continuous or Discrete | Estimate the phenotype or ecology of extinct ancestors. |

| PHYLOGENETIC SIGNAL MEASUREMENT (e.g., Pagel's λ) [1] | Quantify how trait variation follows a phylogeny. | Continuous | Determine if closely related species are more similar than distant ones. |

In comparative biological studies, researchers often aim to understand evolutionary relationships and processes by analyzing traits across different species. A fundamental challenge in such analyses is that species share evolutionary histories, represented by phylogenetic trees, which makes them non-independent data points. Treating species as independent units violates a core assumption of standard statistical tests like ANOVA and linear regression, which require independent sampling units [21] [22]. This violation increases the risk of Type I errors (false positives) because species with recent common ancestors are more likely to have similar traits due to shared ancestry rather than independent evolution [21] [22]. The method of Phylogenetically Independent Contrasts (PIC), introduced by Felsenstein in 1985, provides a solution by transforming comparative data into independent comparisons, thereby accounting for phylogenetic non-independence [21] [22] [23].

Theoretical Foundation: The Logic of Phylogenetic Independence

The Evolutionary Model Behind Independent Contrasts

Independent contrasts operate under a Brownian motion model of evolution, which assumes that traits evolve randomly through time with changes proportional to branch length [23]. This model implies that the expected covariance between species traits is directly proportional to their shared evolutionary history [23]. The phylogenetic tree provides the foundational structure for estimating these expected covariances and calculating proper contrasts [23].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow for implementing phylogenetic independent contrasts:

Core Assumptions of the Independent Contrasts Method

For valid application of independent contrasts, several key assumptions must be met:

- Accurate Phylogeny: The phylogenetic tree must be well-supported with reliable branch length estimates [23]

- Brownian Motion Evolution: The trait of interest should evolve according to a Brownian motion model or an appropriate transformation should be applied [23]

- Adequate Evolutionary Model: The selected model of evolution should appropriately represent the trait's evolutionary process [23]

- Continuous Traits: The method is designed for continuous, not categorical, traits [23]

Violations of these assumptions can lead to biased or incorrect results. For instance, an incorrect phylogenetic tree can produce misleading contrasts, while non-Brownian motion evolution without appropriate adjustment invalidates the contrast calculations [23].

Computational Implementation: Protocols for Analysis

Step-by-Step Protocol for Calculating Independent Contrasts

The following protocol provides detailed methodology for implementing independent contrasts in comparative analysis:

Phylogenetic Tree Estimation

- Use molecular data (e.g., DNA or protein sequences) to estimate a phylogenetic tree

- Apply appropriate methods (maximum likelihood, Bayesian inference, or parsimony) based on data characteristics [23]

- Ensure branch lengths are estimated, as they represent evolutionary time or change

Trait Data Preparation

Evolutionary Model Selection

Contrast Calculation

- Traverse the phylogenetic tree from tips to root

At each node, calculate contrasts using the formula:

(IC = \frac{Xi - Xj}{\sqrt{vi + vj}})

where (Xi) and (Xj) are trait values for sister taxa, and (vi) and (vj) are their variances [23]

- Standardize contrasts by branch lengths

Statistical Analysis

- Analyze contrasts using standard statistical methods (correlation, regression)

- Force regression lines through the origin when using standardized contrasts [23]

- Validate results with diagnostic plots and residual analysis

Software and Tools for Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts Analysis

| Software/Tool | Primary Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| R packages (ape, phytools) | General phylogenetic analysis & PIC implementation | R programming environment [21] [22] |

| PDAP | Phylogenetic comparative methods including PIC | Standalone package [23] |

| CAIC | Comparative analysis using independent contrasts | Standalone package [23] |

| IQ-TREE | Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree estimation | Command-line/standalone [25] |

| BEAST2 | Bayesian phylogenetic analysis | Standalone application [25] |

Methodological Validation: Testing Key Assumptions

Experimental Framework for Validation

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for validating phylogenetic independence in comparative analyses:

Quantitative Framework for Methodological Evaluation

Table 2: Statistical Tests for Validating Phylogenetic Independent Contrasts Assumptions

| Assumption | Diagnostic Test | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Adequate phylogenetic tree | Bootstrap support, posterior probabilities | Nodes with <70% support may introduce error [23] |

| Brownian motion evolution | Likelihood ratio test, AIC comparison | Significant improvement with alternative models indicates violation [23] |

| Proper standardization | Correlation between absolute contrasts and standard deviations | Non-significant correlation indicates proper standardization [23] |

| Trait normality | Shapiro-Wilk test, Q-Q plots | P < 0.05 indicates deviation from normality requiring transformation [24] |

Advanced Applications: Integrating Independent Contrasts with Modern Comparative Methods

While independent contrasts provide a powerful approach for accounting for phylogenetic non-independence, contemporary comparative biology has developed additional sophisticated methods. Phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) extends the PIC approach by allowing more flexible evolutionary models [24]. Additionally, methods incorporating phylogenetic networks rather than strictly bifurcating trees can account for more complex evolutionary processes such as hybridization and introgression [26].

The field continues to advance with improved computational methods for handling large phylogenomic datasets. Model selection procedures have become more sophisticated, allowing researchers to choose between Brownian motion, Ornstein-Uhlenbeck, early burst, and other evolutionary models based on statistical fit to the data [23]. These developments maintain the core principle of accounting for phylogenetic non-independence while expanding the analytical toolkit for evolutionary biologists.

When applying these methods in drug development research, particularly when using model organisms to understand conserved biological pathways, proper phylogenetic correction ensures that apparent therapeutic targets reflect true functional relationships rather than phylogenetic artifacts. This is particularly crucial when translating findings from model systems to human applications, as shared ancestry rather than functional constraint can create misleading correlations.

In the era of large-scale genomic data, comparative phylogenetic analysis has become a cornerstone for biological discovery, from fundamental evolutionary research to applied drug development. However, the power of these analyses is critically dependent on correctly interpreting evolutionary relationships and avoiding pervasive 'tree-thinking' errors. Species, genomes, and genes cannot be treated as independent data points in statistical analyses because they share histories of common descent [27]. This phylogenetic non-independence, if unaccounted for, produces spurious results and misleading biological conclusions [27] [28]. This Application Note provides researchers with structured protocols to identify and overcome common phylogenetic misconceptions, implement robust comparative methods, and accurately extract evolutionary signals from biological data.

Understanding Evolutionary Trees: Core Concepts and Vocabulary

Fundamental Terminology

- Phylogeny: A hypothesis about the evolutionary relationships among species or genes, representing a branching pattern of descent from common ancestors.

- Clade: A group of organisms consisting of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants, forming a complete branch of the tree of life.

- Lineage: A sequence of ancestral-descendant populations through time, representing the line of descent [29].

- Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA): The most recent node from which two or more taxa have descended [30].

- Tree Thinking: The practice of using evolutionary trees to reason about evolutionary relationships and processes [29].

Tree-Thinking vs. Lineage-Thinking

Proper phylogenetic reasoning requires recognizing two complementary but distinct evolutionary realms [29]:

Table: Two Realms of Evolutionary Analysis

| Feature | Realm of Taxa (Tree-Thinking) | Realm of Lineages (Lineage-Thinking) |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Branching realm of evolutionary products | Linear realm of evolutionary processes |

| Composition | Collateral relatives (e.g., species, populations) | Ancestors and their direct descendants |

| Observability | Directly observable (extant and fossil taxa) | Mostly empirically inaccessible (hypothetical ancestors) |

| Primary Focus | Patterns of relatedness among existing taxa | Processes of evolutionary change along lines of descent |

| Visualization | Cladograms, phylogenetic trees | Anagenetic sequences, linear diagrams |

The cladistic blindfold describes the error of focusing exclusively on the branching realm of taxa while overlooking the linear realm of lineages [29]. This leads to rejecting valid evolutionary concepts including linear imagery where appropriate, anagenetic evolution, and the reality that humans evolved from monkey and ape ancestors [29].

Common Phylogenetic Misconceptions and Correct Interpretations

Research on tree-thinking in educational settings reveals persistent misconceptions among students and professionals alike [31]. The following table summarizes major errors and their corrections:

Table: Common Phylogenetic Misconceptions and Corrections

| Misconception | Error Description | Correct Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Reading as Ladders of Progress | Interpreting trees with a "left-to-right" progression where left is "primitive" and right is "advanced" [32] | Trees show relationships, not progress; all extant taxa are modern products of evolution |

| Node Counting | Assuming taxa with more nodes between them are more distantly related | Relatedness determined by recency of common ancestry, not number of nodes [30] |

| Tip Proximity | Judging relatedness by physical proximity of tips on the tree diagram | Relatedness depends on common ancestry, not spatial arrangement; rotating branches doesn't change relationships [30] |

| Primitive Lineage Fallacy | Considering species-poor "early branching" lineages as "ancestral" [32] | All tips are modern species; none are ancestors to others |

| Anagenesis Rejection | Denying evolutionary change along unbranched lineages [29] | Both branching (cladogenesis) and linear (anagenetic) change are fundamental evolutionary patterns |

| Collateral Ancestors | Misidentifying cousins or sisters as ancestors [29] | Ancestors are always in the direct line of descent, not as collateral relatives |

Diagram 1: Transitioning from common phylogenetic misconceptions to correct interpretations. The diagram shows how various tree-thinking errors (yellow) can be corrected through proper understanding of evolutionary principles (green).

Quantitative Assessment of Tree-Thinking Challenges

Educational research provides measurable insights into phylogenetic misinterpretation patterns. One study assessed 160 introductory biology students' ability to construct phylogenetic trees before and after targeted instruction [31].

Table: Performance Measures in Phylogenetic Tree Construction

| Assessment Category | Pre-Instruction Score | Post-Instruction Score | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Features | Significant improvement observed | Improved | Students showed better understanding of tree connectivity, branch termination, and common ancestry |

| Evolutionary Relationships | Minimal improvement | Remained low | Continued difficulty accurately portraying evolutionary relationships among 20 familiar organisms |

| Rationale Development | Limited sophisticated reasoning | Small effect | Most students used ecological or morphological reasoning rather than evolutionary relationships |

| Tree Reading vs. Building | Independent skills | Independent skills | Tree reading and tree building abilities were largely uncorrelated |

These findings highlight that even structured educational interventions may fail to address core conceptual difficulties, emphasizing the need for more effective approaches that integrate tree thinking with lineage thinking [29] [31].

Phylogenetic Comparative Methods: Addressing Non-Independence

The Statistical Foundation

Phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) provide statistical tools that explicitly account for non-independence due to shared evolutionary history [27]. The core principle recognizes that closely related species tend to be similar because they inherit traits from common ancestors, violating the independence assumption of standard statistical tests [27].

Methodological Approaches

Table: Phylogenetic Comparative Methods and Applications

| Method | Primary Function | Data Type | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Regression (PGLS) | Estimates correlations while controlling for phylogeny | Continuous | R packages: phylolm, ape, caper [27] |

| Phylogenetic Mixed Models | Includes phylogenetic similarity as random effect | Continuous/Discrete | R: MCMCglmm, brms; BayesTraits [27] |

| Independent Contrasts | Tests correlations across closely related pairs | Continuous/Discrete | Equivalent to phylogenetic regression [27] |

| Ancestral State Reconstruction | Infers likely trait values of ancestors | Continuous/Discrete | R: corHMM, MCMCglmm; BayesTraits [27] |

| Correlated Evolution Models | Tests if binary traits evolve independently | Discrete | R: ape, phytools; BayesTraits [27] |

| Phylogenetic Path Analysis | Compases causal hypotheses considering phylogeny | Continuous/Discrete | R: phylopath [27] |

For multivariate data, methods using algebraic generalizations of the standard phylogenetic comparative toolkit that employ the trace of covariance matrices are recommended, as they are robust to levels of trait covariation, dimensionality, and data orientation [8].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Phylogenetically Controlled Comparative Analysis

Protocol: Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) Regression

Purpose: To test the relationship between two or more continuous traits while accounting for phylogenetic non-independence.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- R statistical environment

- Packages:

ape,phylolm,caper - Phylogenetic tree (Newick or Nexus format)

- Trait dataset (CSV format)

Procedure:

Data Preparation

- Format trait data as a dataframe with species as rows and traits as columns

- Import phylogenetic tree and ensure tip labels match species names in trait data

- Check for missing data and species mismatches

Model Specification

- Define the biological hypothesis using standard R formula syntax (e.g., y ~ x)

- Select appropriate evolutionary model (Brownian Motion, Ornstein-Uhlenbeck, etc.)

- Consider whether to include additional fixed or random effects

Model Execution

Model Diagnostics

- Check phylogenetic signal in residuals

- Assess model fit using AIC, log-likelihood

- Validate assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity

Interpretation

- Examine coefficient estimates and p-values

- Visualize the relationship with phylogeny-overlaid plots

- Report effect sizes with confidence intervals

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For highly multivariate data, use trace-based methods to avoid matrix ill-conditioning [8]

- For binary response variables, use phylogenetic logistic regression [27]

- When phylogenetic signal is low, PCMs still protect against spurious results from unknown phylogenetically correlated variables [27]

Protocol: Assessing Phylogenetic Signal

Purpose: To quantify how much of the variation in a trait is explained by phylogenetic relationships.

Procedure:

Calculate Blomberg's K

Interpret Values:

- K = 1: Trait evolution follows Brownian motion

- K < 1: Less phylogenetic signal than Brownian motion

- K > 1: More phylogenetic signal than Brownian motion

Statistical Testing:

- Compare observed K to null distribution via randomization

- Significant p-value indicates non-random phylogenetic structure

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Phylogenetic Analysis

Table: Key Resources for Phylogenetic Comparative Methods

| Resource/Software | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | Software platform | Data analysis and visualization | All comparative analyses |

| ape package | R package | Phylogenetic data handling, tree manipulation | Reading, writing, plotting trees; basic comparative methods |

| phylolm package | R package | Phylogenetic regression | PGLS analyses with various evolutionary models |

| MCMCglmm package | R package | Bayesian mixed models | Complex models with phylogenetic random effects |

| BayesTraits | Standalone software | Bayesian analysis of trait evolution | Correlated evolution, ancestral state reconstruction |

| Phylogenetic tree databases | Data resource | Species relationships | Tree of Life, Open Tree of Life, PhyloTree |

Advanced Applications: Integrating Lineage Thinking in Comparative Genomics

Causal Hypothesis Testing

Phylogenetic path analysis extends comparative methods to test complex causal hypotheses while controlling for phylogeny [27]. This approach allows researchers to compare support for different directional relationships among traits.

Diagram 2: Example phylogenetic path model testing causal hypotheses about genome size evolution. The diagram illustrates how comparative methods can evaluate directional relationships between traits while accounting for shared evolutionary history.

Paleontological Integration

PCMs can be effectively combined with fossil data to investigate evolutionary tempo and mode in deep time [33]. Specialized approaches account for uncertainties in fossil dating and phylogenetic relationships.

Robust comparative analysis requires both proper 'tree thinking' that recognizes branching relationships among taxa and 'lineage thinking' that acknowledges linear descent [29]. By implementing the protocols and principles outlined in this Application Note, researchers can avoid common misinterpretations, account for phylogenetic non-independence, and draw biologically meaningful conclusions from comparative data. The integration of rapidly expanding genomic datasets with phylogenetic comparative methods continues to revolutionize evolutionary inference across biological disciplines.

A Practical Guide to Phylogenetic Methods: From Distance-Based to Model-Based Approaches

Distance-based methods represent a foundational approach in phylogenetic inference, enabling researchers to reconstruct evolutionary histories from molecular data. Among these, Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) are two prominent algorithms with distinct theoretical foundations and practical applications [34]. As phylogenetic datasets expand in scale and complexity, understanding the comparative strengths, limitations, and modern implementations of these methods becomes crucial for researchers across biological disciplines, including drug development where phylogenetic insights inform target identification and venom screening [35].

UPGMA, developed by Sokal and Michener in 1958, employs a simple agglomerative clustering approach that assumes a constant rate of evolution across lineages [36] [37]. In contrast, the Neighbor-Joining algorithm, developed later, relaxes this molecular clock assumption and can handle datasets with variable evolutionary rates, making it more applicable to diverse biological scenarios [34]. Both methods utilize pairwise distance matrices as input but differ significantly in their tree-building mechanics and resultant tree properties.

The escalating scale of contemporary phylogenomic studies, exemplified by initiatives like the Earth BioGenome Project which aims to sequence 1.5 million species, necessitates efficient analytical approaches [38]. Traditional phylogenetic pipelines involving genome assembly, annotation, and all-versus-all sequence comparisons present substantial computational bottlenecks. Innovative methods like Read2Tree now enable direct phylogenetic inference from raw sequencing reads, bypassing these intermediate steps and accelerating analysis by 10-100 times while maintaining accuracy [38]. Such advancements underscore the evolving landscape of phylogenetic methodology and its implications for large-scale biological research.

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Mechanisms

UPGMA: Algorithmic Workflow and Assumptions

The UPGMA algorithm operates through sequential hierarchical clustering, iteratively combining the two closest clusters until a complete rooted tree is formed [36] [37]. The algorithm begins by initializing n clusters, each containing a single taxon. At each step, it identifies clusters i and j with the smallest pairwise distance Dij, creates a new cluster (ij) with size n(ij) = ni + nj, and connects i and j to a new node in the tree with branches of length Dij/2 [39]. The distance between the new cluster and any other cluster k is computed as the weighted average: D(ij)k = (ni × Dik + nj × Djk)/(ni + nj) [36]. This process repeats until only one cluster remains.

A fundamental characteristic of UPGMA is its assumption of a molecular clock, which posits constant evolutionary rates across all lineages [34] [39]. This assumption implies that the evolutionary distances from the root to every leaf are equal, resulting in an ultrametric tree where all present-day species are equally distant from the root [39]. While this property makes UPGMA suitable for datasets with relatively uniform evolutionary rates, it becomes a significant limitation when analyzing sequences with substantially divergent evolutionary rates, potentially yielding misleading topological arrangements [34] [39].

Figure 1: UPGMA algorithm workflow demonstrating the sequential clustering process.

Neighbor-Joining: Algorithmic Workflow and Advantages

The Neighbor-Joining method employs a different approach that does not assume a molecular clock, making it applicable to datasets with varying evolutionary rates across lineages [34]. The algorithm begins with a star-like tree and iteratively finds pairs of taxa that minimize the total tree length. For each taxon i, NJ computes an averaging value ui = Σj≠i Dij/(n-2), then selects the pair (i,j) that minimizes Qij = Dij - ui - uj for joining [40]. This joining criterion helps correct for the stochastic error that some taxa may have accumulated more changes than others.

When taxa i and j are joined, NJ creates a new node u and calculates branch lengths from i and j to u as: δiu = Dij/2 + (ui - uj)/2 and δju = Dij/2 + (uj - ui)/2 [40]. The distance matrix is then updated with distances between the new node u and each remaining taxon k computed as: Dku = (Dik + Djk - Dij)/2. This process repeats until all taxa have been joined, typically producing an unrooted tree that can be rooted using an outgroup [34].

The ability of NJ to accommodate variable evolutionary rates without the ultrametric constraint makes it particularly valuable for real biological datasets where evolutionary rates frequently differ across lineages [34]. This flexibility, combined with its mathematical properties like consistency (converging to the true tree with sufficient data), has established NJ as one of the most widely used distance-based methods in phylogenetics.

Figure 2: Neighbor-Joining algorithm workflow highlighting the iterative pair selection process.

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Attributes

Algorithmic Properties and Performance Metrics

The structural differences between UPGMA and Neighbor-Joining translate to distinct algorithmic properties and performance characteristics. Understanding these distinctions is essential for method selection appropriate to specific research contexts and dataset properties.

Table 1: Comparative attributes of UPGMA and Neighbor-Joining methods

| Attribute | UPGMA | Neighbor-Joining |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Type | Sequential hierarchical clustering | Bottom-up clustering using minimum evolution principle |

| Tree Shape | Produces rooted trees [34] | Can produce unrooted or rooted trees [34] |

| Tree Balance | Produces balanced trees [34] | Can produce balanced or unbalanced trees [34] |

| Molecular Clock Assumption | Assumes constant rate evolution (ultrametric) [34] [39] | Does not assume molecular clock [34] |

| Computational Complexity | O(n³) [34] | O(n³) [34] |

| Accuracy | May produce less accurate trees when molecular clock violated [34] | Can produce more accurate trees across varying rates [34] |

| Long-Branch Attraction | Less prone to long-branch attraction [34] | Sensitive to long-branch attraction [34] |

| Distance Matrix Usage | Uses pairwise distances between taxa [34] | Uses pairwise distances between taxa [34] |

Advantages and Limitations in Phylogenetic Inference

UPGMA offers several practical advantages that maintain its relevance in specific research contexts. The algorithm's simplicity and intuitive clustering approach make it easy to implement and interpret [37]. The production of rooted, ultrametric trees provides direct information about evolutionary timing, which can be valuable for analyses assuming a molecular clock [34]. Additionally, UPGMA is less susceptible to long-branch attraction, where rapidly evolving lineages are erroneously grouped together due to chance similarities [34]. These properties make UPGMA suitable for preliminary analyses, constructing guide trees for multiple sequence alignment, or datasets with strong evidence of rate constancy.

However, UPGMA's limitations are significant when its assumptions are violated. The constant rate assumption frequently fails in biological systems, potentially producing incorrect tree topologies when evolutionary rates substantially differ across lineages [34] [37]. The method is also highly sensitive to errors in the distance matrix, as inaccuracies can propagate through the averaging process [34]. These constraints restrict UPGMA's application in complex evolutionary scenarios.

Neighbor-Joining addresses several key limitations of UPGMA. Its most significant advantage is the ability to handle datasets with varying evolutionary rates without assuming a molecular clock [34]. This flexibility often results in higher accuracy for diverse biological datasets where rate heterogeneity exists. NJ is also relatively robust against random errors in the distance matrix due to its pairwise distance approach [34]. Furthermore, NJ can effectively handle missing data in distance matrices, making it suitable for datasets with incomplete information [34].

NJ does present certain limitations, including sensitivity to long-branch attraction under specific conditions, where distantly related sequences with long branches may be incorrectly grouped [34]. The method also assumes additive evolutionary distances, which may not hold with significant homoplasy or distinct evolutionary models [34]. While NJ's time complexity is O(n³) like UPGMA, the actual computation time is generally longer due to more complex calculations at each step [34].

Protocol for Phylogenetic Analysis Using NJ and UPGMA

Data Preparation and Distance Matrix Computation

Input Requirements: The initial input for both NJ and UPGMA consists of molecular sequence data (DNA, RNA, or protein) in FASTA or similar format. For conventional analysis, sequences should be pre-aligned using multiple sequence alignment tools such as MAFFT [38] or MUSCLE. Alternatively, methods like Read2Tree can process raw sequencing reads directly, aligning them to reference orthologous groups while bypassing genome assembly and annotation [38].

Distance Calculation: Compute pairwise genetic distances between all sequences using appropriate substitution models (e.g., Jukes-Cantor, Kimura 2-parameter, or more complex models selected through model testing). The resulting distance matrix should be symmetrical with zero diagonal elements, representing the estimated evolutionary divergence between each sequence pair.

Table 2: Research reagents and computational tools for phylogenetic analysis

| Resource Type | Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Data Sources | NCBI GenBank, Dryad, FigShare [41] | Raw sequencing reads or assembled sequences; TreeHub provides 135,502 trees from 7,879 articles [41] |

| Alignment Tools | MAFFT [38], MUSCLE, ClustalΩ | Critical for conventional analysis; alignment quality significantly impacts tree accuracy |

| Distance Calculation | MEGA, PHYLIP, Paup* | Implement various substitution models; model selection should match sequence characteristics |

| Tree Construction | MEGA, PHYLIP, MVSP, DendroUPGMA [37] | User-friendly interfaces for both NJ and UPGMA implementations |

| Large-Scale Analysis | Read2Tree [38], SparseNJ [40], FastTree | Read2Tree processes raw reads directly; SparseNJ reduces distance computations [40] |

| Tree Visualization | FigTree, iTOL, Dendroscope | Enable exploration and annotation of resulting phylogenetic trees |

Tree Construction Protocol

UPGMA Implementation:

- Initialization: Begin with n clusters, each containing one taxon. Initialize cluster sizes: ni = 1 for all i.

- Distance Search: Identify the two clusters (i and j) with the smallest distance Dij in the matrix.

- Cluster Merging: Create a new cluster (ij) with n(ij) = ni + nj members.

- Tree Updating: Connect clusters i and j to a new node in the tree. Set branch lengths: δi = Dij/2 and δj = Dij/2.

- Matrix Updating: Compute distances between the new cluster and all other clusters k using the formula: D(ij)k = (ni × Dik + nj × Djk)/(ni + nj).

- Iteration: Remove rows and columns for i and j from the matrix. Add a new row and column for cluster (ij). Repeat steps 2-5 until only one cluster remains.

Neighbor-Joining Implementation:

- Initialization: Start with a star-tree and the complete n × n distance matrix D.

- Averaging Value Calculation: For each taxon i, compute ui = Σj≠i Dij/(n-2).

- Pair Selection: Find the pair (i,j) that minimizes Qij = Dij - ui - uj.

- Node Creation: Create a new node u. Calculate branch lengths: δiu = Dij/2 + (ui - uj)/2 δju = Dij/2 + (uj - ui)/2

- Matrix Updating: Compute distances between the new node u and each remaining taxon k: Dku = (Dik + Djk - Dij)/2.

- Iteration: Remove taxa i and j from the matrix, add the new node u. Repeat steps 2-5 until three taxa remain.

- Final Connection: Connect the last three taxa using their pairwise distances.

Tree Validation and Interpretation

Assessment of Support: For both methods, evaluate topological reliability using bootstrap resampling (typically with 100-1000 replicates). Branches with bootstrap support ≥70% are generally considered well-supported, though this threshold varies across studies.

Tree Interpretation: For UPGMA trees, interpret branch lengths as proportional to time due to the molecular clock assumption. For NJ trees, branch lengths represent amount of evolutionary change, which may not correlate directly with time. Root NJ trees using appropriate outgroup taxa to establish evolutionary directionality.

Advanced Applications and Scalability Solutions

Handling Large-Scale Datasets

The computational complexity of O(n³) for both NJ and UPGMA presents significant challenges for large datasets with thousands of taxa [42] [40]. Several innovative approaches address this scalability bottleneck:

Sparse Neighbor Joining (SNJ) reduces the computational burden by dynamically determining a sparse set of distance matrix entries to compute, decreasing the required calculations to O(n log n) or O(n log² n) in its enhanced version [40]. This approach maintains statistical consistency while significantly improving execution time for large datasets, with a trade-off in accuracy that is often acceptable for initial analyses.

Read2Tree bypasses traditional computational bottlenecks by directly processing raw sequencing reads into groups of corresponding genes, eliminating the need for genome assembly, annotation, and all-versus-all sequence comparisons [38]. This approach achieves 10-100 times faster processing than assembly-based methods while maintaining accuracy, particularly beneficial for large-scale genomic studies like the 435-species yeast tree of life reconstruction [38].

Divide-and-conquer strategies implement disjoint tree mergers (DTMs) that partition species sets into subsets, build trees on each subset, then merge them into a complete phylogeny [40]. These approaches facilitate parallel processing and distributed computing, dramatically improving scalability for datasets with extremely large taxon sampling.

Emerging Applications in Biological Research

Contemporary applications of these phylogenetic methods extend beyond traditional evolutionary studies:

Drug Discovery and Development: Phylogenetics enables identification of medically valuable traits across species, particularly in venom-producing animals used to develop pharmaceuticals like ACE inhibitors and Prialt (Ziconotide) [35]. Phylogenetic trees help screen closely related species for potentially useful biochemical compounds, streamlining the discovery process.

Cancer Research: Phylogenetic analyses reconstruct tumor progression trees, tracing clonal evolution and molecular chronology through treatment regimens [35]. These approaches utilize whole genome sequencing to model how cell populations vary during disease progression, informing therapeutic strategies.

Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Phylogenetic methods track pathogen transmission dynamics, as demonstrated by the application to >10,000 Coronaviridae samples where highly diverse animal samples and near-identical SARS-CoV-2 sequences were accurately classified on a single tree [38].

Forensic Science: Phylogenetic analysis serves as evidence in legal proceedings, particularly in HIV transmission cases where genetic relatedness between samples can establish connections, though limitations exist in determining directionality [35].

UPGMA and Neighbor-Joining represent foundational approaches in distance-based phylogenetic inference with complementary strengths and applications. UPGMA's simplicity and ultrametric assumption make it suitable for datasets with relatively constant evolutionary rates or when a rooted timescaled tree is desired. In contrast, Neighbor-Joining's flexibility in handling variable evolutionary rates provides broader applicability across diverse biological systems where rate heterogeneity exists.

The scalability challenges associated with both methods have prompted innovative computational solutions, including Sparse Neighbor Joining for reducing distance matrix computations and Read2Tree for direct processing of raw sequencing data [38] [40]. These advancements, coupled with growing phylogenetic resources like TreeHub's comprehensive dataset of 135,502 trees [41], continue to expand the applicability of distance-based methods to increasingly large and complex biological questions.

For researchers and drug development professionals, method selection should be guided by dataset characteristics, evolutionary assumptions, and analytical goals. UPGMA remains valuable for preliminary analyses and specific applications assuming a molecular clock, while Neighbor-Joining offers robust performance across diverse evolutionary scenarios. The integration of these classical algorithms with modern computational approaches ensures their continued relevance in the era of large-scale phylogenomics and comparative genomics.