Comparative Methods for Evolutionary Constraint Analysis: From Genomic Signals to Clinical Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern comparative methods for evolutionary constraint analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Methods for Evolutionary Constraint Analysis: From Genomic Signals to Clinical Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern comparative methods for evolutionary constraint analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of how sequence evolution and population variation are shaped by structural and functional constraints. The review details key methodological approaches, including residue-level metrics like the Missense Enrichment Score (MES) and computational frameworks that leverage these signals for predicting protein structure and function. It further addresses common analytical challenges and optimization strategies, and offers a comparative validation of different techniques. By synthesizing insights from evolutionary and population genetics, this article aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to better predict pathogenic variants, identify critical functional residues, and de-risk drug target selection.

The Genomic Footprint of Natural Selection: Uncovering Evolutionary and Population Constraints

Defining Evolutionary and Population Constraint in Protein Domains

The evolution and function of proteins are shaped by selective pressures that leave characteristic signatures in genetic sequences. Two primary sources of data reveal these constraints: evolutionary conservation, which reflects deep evolutionary pressures across species, and population constraint, which captures more recent selective pressures within a single species, such as humans. The integration of these complementary signals provides a powerful framework for identifying structurally and functionally critical regions in proteins, with significant implications for understanding protein structure, predicting pathogenicity of variants, and informing drug development. This guide outlines the core concepts, methodologies, and applications of analyzing evolutionary and population constraint in protein domains, framing them within comparative methods for evolutionary constraint analysis.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Evolutionary Constraint

Evolutionary constraint refers to the reduced rate of sequence change at specific amino acid positions due to selective pressures imposed by protein structure and function. It is typically measured by analyzing sequence conservation across a deep multiple sequence alignment of homologous proteins from diverse species. Key metrics include:

- Shenkin's diversity: A measure of residue-level conservation based on the diversity of amino acids observed at a given alignment column; lower diversity indicates higher evolutionary conservation [1].

Population Constraint

Population constraint reflects the intolerance of specific protein residues to genetic variation within a population, such as humans. It leverages large-scale human population genomic databases to identify residues where missense variants are depleted. A key metric is:

- Missense Enrichment Score (MES): A residue-level metric quantifying the odds ratio of a position's rate of missense variation compared to the rest of the domain. MES < 1 indicates missense-depleted sites (constrained), MES > 1 indicates missense-enriched sites, and MES ≈ 1 indicates missense-neutral sites [1].

The Conservation Plane

Integrating evolutionary conservation and population constraint creates a powerful classification system known as the conservation plane, where residues are categorized based on their combined scores [1]:

- Conserved & Constrained: Critical for folding/core function.

- Diverse & Constrained: Often involved in functional specificity.

- Conserved & Unconstrained: Requires further investigation.

- Diverse & Unconstrained: Under weak selective pressure.

Experimental and Computational Protocols

This section details the primary methodologies for quantifying and analyzing constraints.

Protocol 1: Generating a Residue-Level Map of Population Constraint

Objective: To calculate the Missense Enrichment Score (MES) across protein domain families. This protocol is adapted from the workflow used to map 2.4 million variants to 5885 protein families [1].

Materials & Input Data:

- Protein Domain Families: Curated families from databases such as Pfam [1].

- Population Variant Data: Missense and synonymous variants from large-scale sequencing projects like gnomAD [1].

- Multiple Sequence Alignments: Pre-computed alignments for each protein domain family.

- Computational Tools: Custom scripts for statistical analysis (e.g., R, Python).

Procedure:

- Variant Mapping: Map population missense and synonymous variants (e.g., from gnomAD) to their corresponding positions within the multiple sequence alignments of protein domain families (e.g., from Pfam).

- Variant Aggregation: For each column in the alignment, aggregate the counts of missense variants observed across all human paralogs.

- MES Calculation: For each residue position

iin a domain family:- Construct a 2x2 contingency table:

- Classification: Classify residues based on MES and its p-value:

- Missense-depleted: MES < 1; p < 0.1 (high constraint)

- Missense-enriched: MES > 1; p < 0.1 (low constraint)

- Missense-neutral: p ≥ 0.1

Protocol 2: Structural Validation of Constrained Sites

Objective: To validate the structural and functional relevance of constrained sites identified via MES and evolutionary conservation.

Materials & Input Data:

- Constraint Data: Output from Protocol 1 (MES scores and classifications).

- Protein Structures: Experimentally determined structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Structural Analysis Tools: Software for calculating solvent accessibility and identifying binding sites (e.g., DSSP, PyMOL scripts).

Procedure:

- Structure Mapping: Map the classified constraint sites (e.g., missense-depleted, evolutionarily conserved) onto available high-resolution protein structures.

- Solvent Accessibility Calculation: Calculate the relative solvent accessibility (RSA) for each residue in the structure. Classify residues as buried or exposed based on a predefined RSA threshold.

- Binding Site Annotation: Annotate residues involved in known or predicted small-molecule ligand binding sites and protein-protein interfaces using data from PDB files or external databases.

- Enrichment Analysis: Perform statistical tests (e.g., Chi-squared test) to determine if constrained sites are significantly enriched for specific structural features (e.g., buried residues, binding interfaces) compared to unconstrained sites.

Advanced Integrative Workflow

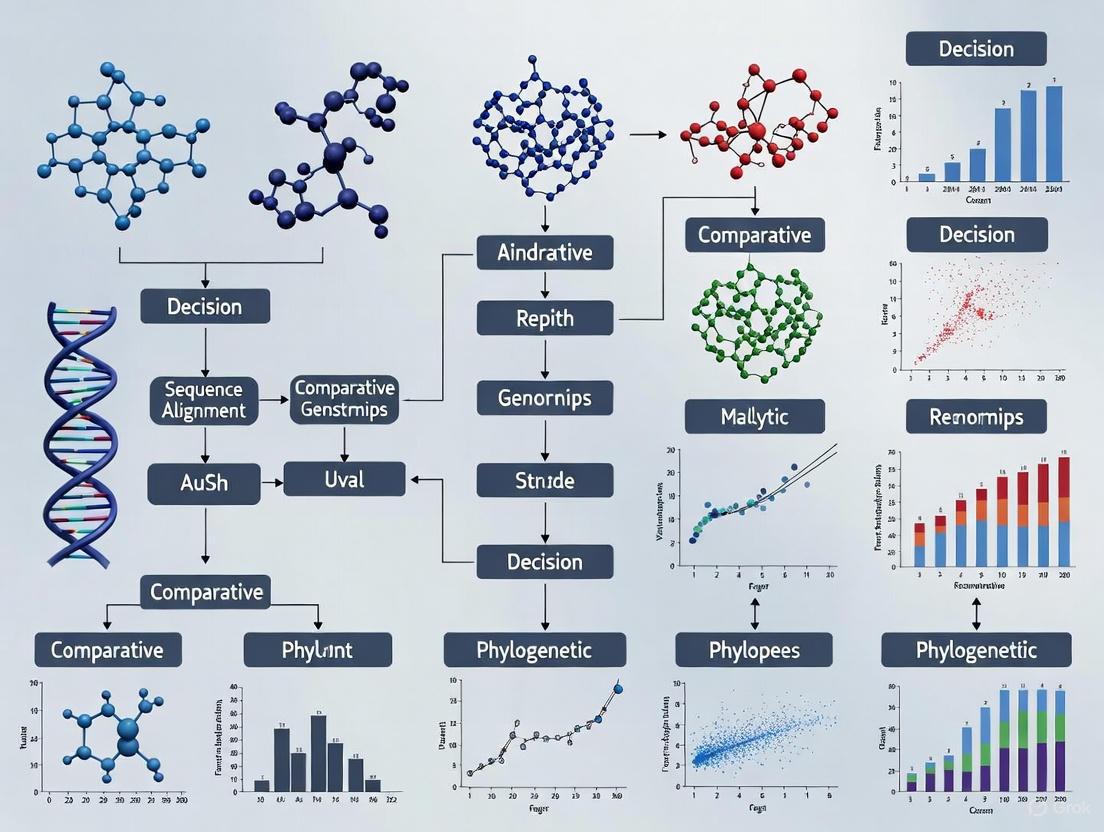

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of an integrated analysis, combining the protocols above with complementary data to derive biological insights.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for analyzing evolutionary and population constraint, from data input to biological insight.

Key Quantitative Findings

The application of these protocols has yielded consistent, quantifiable patterns linking genetic constraint to protein structural biology.

Table 1: Structural Enrichment of Constrained Sites Data derived from analysis of 61,214 PDB structures across 3,661 Pfam domains [1].

| Residue Classification | Enrichment in Buried Residues | Enrichment in Ligand Binding Sites | Enrichment in Protein-Protein Interfaces |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missense-Depleted (MES < 1) | Strongly Enriched | Strongly Enriched | Enriched (especially at surface) |

| Evolutionarily Conserved | Strongly Enriched | Strongly Enriched | Enriched (especially at surface) |

| Missense-Enriched (MES > 1) | Strongly Depleted | Depleted | Depleted |

Table 2: Residue Classification via the Conservation Plane This framework allows for the functional interpretation of different constraint signatures [1].

| Evolutionary Conservation | Population Constraint | Interpretation | Typical Structural Correlate |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | High (Depleted) | Critical for folding or universal function | Protein core, catalytic sites |

| Low | High (Depleted) | Involved in functional specificity; potential for adaptive evolution | Species-specific interaction interfaces |

| High | Low (Enriched/Neutral) | Requires further investigation; potential for technical artifact | Variable |

| Low | Low (Enriched/Neutral) | Under weak selective pressure; tolerant to variation | Protein surface, disordered regions |

Successful constraint analysis relies on a suite of public databases and software tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Constraint Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| gnomAD(Genome Aggregation Database) | Data Repository | Provides a comprehensive catalog of human genetic variation (missense, synonymous, LoF variants) from population sequencing, essential for calculating population constraint [1]. |

| Pfam | Database | Curated collection of protein families and multiple sequence alignments, serving as the scaffold for mapping variants and calculating evolutionary conservation [1]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Data Repository | Archive of experimentally determined 3D protein structures used to validate and interpret the structural context of constrained sites [1]. |

| ClinVar | Data Repository | Public archive of relationships between genetic variants and phenotypic evidence (e.g., pathogenicity), used for validating the clinical relevance of constrained sites [1]. |

| HMMER | Software Tool | Suite for profile hidden Markov model analysis, used for sensitive homology detection and sequence alignment, foundational for building accurate MSA [2]. |

| EvoWeaver | Software Tool | A method that integrates 12 coevolutionary signals to predict functional associations between genes, useful for extending functional insights beyond individual domains [3]. |

Advanced Applications and Integrative Analyses

Insights from Specific Protein Families

- Repeat Proteins (e.g., Ankyrin, TPR): Analysis of tandem repeat families demonstrates that positions critical for structural integrity and protein-substrate interactions show strong constraint in both evolutionary and population data, validating the generalizability of the approach [4].

- Experimental Evolution in E. coli: Adaptive genetics experiments under glucose limitation reveal that high-value targets of selection (e.g., regulatory proteins, LPS export machinery) show strong clustering of mutations at sites involved in protein-protein or protein-RNA interactions, mirroring the constraint patterns observed in natural populations [5].

A Pathway View of Constraint

The integration of constraint data with pathway-level analysis can reveal how selective pressures shape entire functional modules. The following diagram illustrates how a tool like EvoWeaver uses coevolution to connect constrained domains into functional pathways [3].

Diagram 2: Using coevolutionary signals to infer functional associations and pathway membership between constrained protein domains, enabling functional annotation of uncharacterized proteins.

The unified analysis of evolutionary and population constraint provides a robust, multi-faceted lens through which to view protein structure, function, and evolution. The methodologies outlined here—centered on the calculation of the Missense Enrichment Score and its integration with deep evolutionary conservation—enable researchers to move beyond simple sequence analysis to a more predictive, structurally-grounded understanding of proteins. As population genomic datasets continue to grow and methods for detecting coevolution and other forms of constraint improve, this integrated approach will become increasingly critical for prioritizing functional genetic variants in disease research and for informing the development of therapeutics that target constrained, and thus functionally essential, protein regions.

The integration of massive-scale population genetic data from resources like gnomAD with evolutionary protein family information from Pfam represents a transformative approach for analyzing evolutionary constraints. This technical guide details methodologies for mapping millions of variants to protein domains, calculating constraint metrics, and interpreting results within a comparative evolutionary framework. We provide experimental protocols, analytical workflows, and practical resources to enable researchers to identify structurally and functionally critical residues through the combined lens of population genetics and deep evolutionary conservation.

Evolutionary constraint analysis has traditionally relied on comparative sequence analysis across species to identify functionally important genomic regions. The emergence of large-scale human population sequencing datasets, particularly the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), now enables complementary analysis of constraint through recent evolutionary pressures observable within human populations. Simultaneously, protein family databases like Pfam provide evolutionary context through multiple sequence alignments of homologous domains across the tree of life.

Integrating these data sources creates a powerful framework for identifying residues critical for protein structure and function. Evolutionary conservation from Pfam reflects constraints operating over deep evolutionary timescales, while population constraint from gnomAD reveals recent selective pressures within humans. The combination offers unique biological insights: evolutionary-conserved but population-tolerant sites may indicate family-wide structural requirements, while evolutionarily diverse but population-constrained sites might reveal human-specific functional adaptations [1].

This technical guide details methods for large-scale variant mapping and analysis, building on recent research that mapped 2.4 million population missense variants from gnomAD to 5,885 protein domain families from Pfam [1].

Table 1: Core Data Resources for Variant-Protein Family Integration

| Resource | Description | Key Statistics | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| gnomAD [1] | Catalog of human genetic variation from population sequencing | v2: ~125,748 exomes; v4: 1.46 million haploid exomes [2] | Source of population missense variants and allele frequencies |

| Pfam [6] | Database of protein domain families and alignments | 5,885 families covering 5.2 million human proteome residues [1] | Evolutionary context and homologous position mapping |

| ClinVar [7] | Archive of human variant-pathogenicity assertions | Clinical interpretations for variants linked to evidence | Pathogenic variant validation and benchmarking |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] | Repository of 3D protein structures | 61,214 structures spanning 3,661 Pfam domains [1] | Structural feature annotation (solvent accessibility, binding interfaces) |

Quantitative Data Landscape

Table 2: Representative Dataset Scales from Recent Studies

| Data Integration Aspect | Scale | Biological Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| Missense variants mapped to Pfam families | 2.4 million variants [1] | 1.2 million positions across 5,885 domains |

| Structural annotation | 105,385 residues with solvent accessibility data [1] | 40,394 sequences from 3,661 Pfam domains |

| Pathogenic variant analysis | >10,000 ClinVar variants mapped [1] | Clinical validation across multiple disease genes |

| Constraint classification | 5,086 missense-depleted positions (strong constraint) [1] | 365,300 residues in human proteome |

Core Methodologies

Variant Mapping and Annotation Pipeline

Protocol: Mapping gnomAD Variants to Pfam Alignments

Variant Data Acquisition

- Download gnomAD release (v2.1.1 or newer) containing missense variants, allele frequencies, and ancestral allele predictions [7]

- Filter variants to PASS only to remove technical artifacts

- Retain variants with global minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.005 for rare variant analysis

Pfam Domain Annotation

- Download Pfam-A full alignments and HMM profiles (current version)

- Map human proteome (UniProt) to Pfam domains using HMMER3 search

- Extract domain boundaries and multiple sequence alignment positions

Variant-to-Domain Mapping

- Convert gnomAD genomic coordinates (GRCh38) to protein positions using Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) v99 or newer [7]

- Annotate variants falling within Pfam domain boundaries

- Collate variants occurring at homologous positions across human paralogs

Quality Control and Filtering

- Exclude variants in low-complexity regions or segmental duplications [7]

- Remove variants with poor sequence alignment quality or ambiguous mapping

- Verify coordinate conversion accuracy for a subset of manually curated variants

Constraint Metrics Calculation

A. Missense Enrichment Score (MES)

The Missense Enrichment Score quantifies population constraint at individual alignment columns by comparing variant rates across homologous positions [1].

Calculation Protocol:

- For each position i in a Pfam alignment, count:

- $Missensei$: Number of human paralogs with missense variants at position i

- $Totali$: Number of human paralogs covering position i

- Calculate position-specific missense rate: $Ratei = Missensei / Total_i$

- Compute domain-wide background missense rate: $Rate{background} = \sum Missensej / \sum Total_j$ for all positions j in domain

- Calculate MES as odds ratio: $MESi = Ratei / Rate_{background}$

- Assess statistical significance using Fisher's exact test (two-tailed) comparing variant counts at position i versus all other positions

Interpretation:

- Missense-depleted: MES < 1 with p < 0.1 (constrained positions)

- Missense-enriched: MES > 1 with p < 0.1 (tolerant positions)

- Missense-neutral: p ≥ 0.1 (no significant constraint deviation)

B. Evolutionary Conservation Metrics

Protocol: Shenkin Diversity Calculation [1]

- For each Pfam alignment column, compute position-specific scoring matrix

- Calculate Shannon entropy: $Hi = -\sum{aa} f{aa,i} \cdot \log2(f{aa,i})$ where $f{aa,i}$ is frequency of amino acid aa at position i

- Convert to conservation score: $Conservationi = \log2(20) - H_i$ (maximum when completely conserved)

- Normalize by alignment depth to account for sampling bias

Structural and Functional Annotation

Protocol: Structural Feature Mapping

Solvent Accessibility Annotation

- Map Pfam domains to PDB structures using PDBe API

- Calculate relative solvent accessibility (RSA) for each residue using DSSP

- Classify residues as buried (RSA < 20%) or exposed (RSA ≥ 20%)

Binding Interface Identification

- Protein-protein interfaces: Residues with atoms within 5Å of different protein chains

- Ligand-binding sites: Residues with atoms within 4Å of small molecule ligands

- Control for solvent accessibility in interface analyses

Statistical Analysis of Feature Enrichment

- Use χ² tests to assess association between constraint categories and structural features

- Report effect sizes as odds ratios with confidence intervals

- Apply multiple testing correction (Benjamini-Hochberg FDR)

Experimental Protocols

Residue Classification via Conservation Plane

Objective: Classify residues into functional categories based on combined evolutionary and population constraint patterns.

Procedure:

- Calculate both MES and evolutionary conservation for all positions

- Create 2D scatter plot (conservation plane) with evolutionary conservation on x-axis and MES on y-axis

- Divide plane into quadrants using thresholds:

- Evolutionary conservation: Median split or specific cutoff (e.g., Shenkin diversity >2)

- Population constraint: MES = 1 (depleted vs. enriched)

- Characterize structural and functional properties of each quadrant:

- High evolutionary conservation, low MES: Critical structural/functional residues

- High evolutionary conservation, high MES: Possibly misannotated or rapidly evolving

- Low evolutionary conservation, low MES: Human-specific functional constraints

- Low evolutionary conservation, high MES: Neutrally evolving positions

Pathogenic Variant Analysis

Objective: Assess clinical relevance of constraint metrics using known pathogenic variants.

Procedure:

- Obtain pathogenic/likely pathogenic missense variants from ClinVar [7]

- Filter for variants with reviewed assertions and conflict resolution

- Map pathogenic variants to Pfam domain positions

- Calculate enrichment of pathogenic variants in missense-depleted positions

- Fisher's exact test comparing pathogenic variant counts in depleted vs. non-depleted sites

- Assess predictive performance using precision-recall analysis

- Compare with evolutionary conservation alone to evaluate added value of population constraint

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| gnomAD API | Data resource | Programmatic access to population variant data and frequencies | https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org |

| Pfam HMM profiles | Database | Hidden Markov Models for domain detection in protein sequences | https://pfam.xfam.org |

| HMMER3 suite | Software tool | Sequence homology search using profile HMMs | http://hmmer.org |

| Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) | Annotation tool | Genomic coordinate conversion and consequence prediction | https://www.ensembl.org/info/docs/tools/vep |

| PDB API | Structural biology resource | Programmatic access to 3D structural data | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/api |

| ClinVar FTP | Clinical database | Bulk download of clinical variant interpretations | https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/clinvar |

Analysis Workflow Integration

Applications and Interpretation

Structural Biology Insights

Integrated constraint analysis reveals distinct structural patterns:

- Missense-depleted positions show strong enrichment in buried residues (core packing) and ligand-binding sites [1]

- Protein-protein interfaces show constraint primarily at surface-exposed positions

- Combined evolutionary and population constraint improves prediction of functional residues compared to either metric alone

Clinical Variant Interpretation

The integration framework enhances rare variant interpretation:

- Regional constraint patterns within genes improve risk assessment for missense VUS [7]

- Pathogenic variants cluster in segments with both evolutionary conservation and population constraint

- Some clinical variant hotspots occur at missense-enriched positions, suggesting potential compensatory mechanisms or context-dependent effects [1]

Drug Development Applications

- Target Prioritization: Genes under strong constraint may indicate non-tolerable functional disruption

- Functional Site Mapping: Identification of constrained binding interfaces informs targeted therapeutic development

- Safety Assessment: Population constraint patterns may predict dose-limiting toxicity from on-target effects

The relationship between protein sequence, structure, and function represents a fundamental paradigm in molecular biology, with evolutionary pressures creating distinct patterns of residue conservation and diversity. While comparative genomics has long exploited evolutionary conservation to predict structural and functional features, the explosion of human population sequencing data has enabled the investigation of genetic constraint within a single species. The Missense Enrichment Score (MES) emerges as a novel residue-level metric that quantifies this population constraint by analyzing the distribution of missense variants across protein families [8]. This technical guide explores the development, calculation, and application of MES, positioning it within the broader context of comparative methods for evolutionary constraint analysis. For researchers in structural biology and drug discovery, MES provides a complementary perspective to evolutionary conservation, revealing functionally critical residues through human genetic variation and offering insights for pathogenicity prediction and functional annotation [8].

Theoretical Foundation and Calculation of MES

Conceptual Framework

The MES operates on the principle that protein residues essential for structure or function will demonstrate reduced tolerance to genetic variation within human populations. This constraint manifests as a depletion of missense variants at these positions relative to other sites within the same protein domain. The metric was developed specifically to address the challenge of quantifying population constraint at residue-level resolution, which existing gene-level or domain-level constraint scores could not adequately capture [8].

The profound differences between evolutionary and population datasets underscore the unique perspective MES offers. Evolutionary conservation, as catalogued in databases like Pfam, reflects cumulative effects over hundreds of millions of years across diverse species. In contrast, population datasets like gnomAD capture genetic diversity influenced by recent human demographic events, migrations, and drift within a single species [8]. This temporal and species-specific focus allows MES to detect constraint signals potentially masked in deep evolutionary analyses.

Calculation Methodology

The MES quantifies relative population constraint at each alignment column in a protein domain family using the following operational components:

Data Mapping: 2.4 million population missense variants from gnomAD are mapped to 1.2 million positions within 5,885 protein domain families from Pfam, covering 5.2 million residues of the human proteome [8].

Odds Ratio Calculation: For each position in a domain alignment, MES computes the odds ratio of that position's rate of missense variation compared to all other positions within the same domain. This normalization accounts for varying numbers of human paralogs and heterogeneity in overall constraint due to factors like gene essentiality [8].

Statistical Significance: A p-value is calculated using Fisher's exact test to determine the significance of the deviation of MES from 1 (no enrichment or depletion). This non-parametric approach makes no distributional assumptions and performs robustly even for small protein families with low variant counts [8].

Based on the calculated MES and its associated p-value, residues are classified into three constraint categories:

- Missense-depleted: MES < 1 with p < 0.1, indicating significant constraint

- Missense-enriched: MES > 1 with p < 0.1, indicating permissiveness to variation

- Missense-neutral: p ≥ 0.1, showing no significant deviation from expected variation rates

Table 1: MES Residue Classification Criteria

| Category | MES Value | P-value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missense-depleted | < 1 | < 0.1 | Under significant constraint |

| Missense-enriched | > 1 | < 0.1 | Tolerant to variation |

| Missense-neutral | ≈ 1 | ≥ 0.1 | No significant constraint |

Comparative Analysis of Constraint Metrics

MES in Relation to Evolutionary Conservation

The relationship between population constraint (MES) and evolutionary conservation reveals both concordance and divergence in constraint signatures. Initial analyses demonstrated a strong positive correlation between population missense variants and evolutionary diversity measured by Shenkin's conservation metric, with 85% of protein families with >100 human paralogs showing this significant association [8].

This complementary relationship enables a novel classification of residues according to a "conservation plane" defined by both evolutionary conservation and population constraint:

- Evolutionarily conserved AND missense-depleted: Critical for protein folding or core function

- Evolutionarily diverse BUT missense-depleted: Potential species-specific functional adaptations

- Evolutionarily conserved BUT missense-enriched: Possible contrast between lethal and non-lethal pathogenic sites

- Clinical variant hot spots: Located at a subset of missense-enriched positions [8]

Table 2: Comparative Properties of Constraint Metrics

| Metric | Data Source | Evolutionary Timescale | Primary Application | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MES | Human population variants (gnomAD) | Recent human evolution | Pathogenicity prediction, structural inference | Species-specific constraint, clinical variant interpretation |

| Evolutionary Conservation (e.g., Shenkin) | Cross-species homologs | Hundreds of millions of years | Protein structure prediction, functional site identification | Deep evolutionary patterns, structural constraints |

| Combined Approach | Both sources | Multiple timescales | Functional classification, variant interpretation | Discriminatory power for functional residues |

Structural Correlates of MES Constraint

Analysis of 61,214 three-dimensional structures from the PDB spanning 3,661 Pfam domains revealed strong associations between MES constraint categories and structural features:

Solvent Accessibility: Missense-depleted sites are predominantly buried in the protein core (χ² = 1285, df = 4, p ≈ 0, n = 105,385), while missense-enriched sites tend to be surface-exposed [8].

Ligand Binding Sites: Missense-depleted positions show pronounced enrichment at ligand binding sites, particularly at surface-accessible positions where external interactions impose functional constraints [8].

Protein-Protein Interfaces: Significant enrichment of missense-depleted residues occurs at protein-protein interfaces, though this effect is most detectable when controlling for solvent accessibility due to the infrequent interactions of buried residues with other proteins [8].

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Proteome-Scale Constraint Mapping

The foundational protocol for large-scale MES analysis involves systematic processing of population genetic and protein family data:

Variant Annotation: Annotate gnomAD missense variants (v2.4 million) with protein domain coordinates from Pfam (5,885 families) using residue-level mapping [8].

Multiple Sequence Alignment: Generate human-paralog-aware multiple sequence alignments for each Pfam domain to identify homologous positions.

Variant Aggregation: Collate variants occurring at homologous positions across the protein family to enhance signal for residue-level constraint detection.

MES Calculation: Compute odds ratio and statistical significance for each alignment position using Fisher's exact test with implementation in Python/R.

Structural Mapping: Map MES classifications to 3D structures from the PDB using residue indices and structural alignment where necessary.

Functional Classification of Ligand Binding Sites

MES has been integrated into protocols for classifying ligand binding sites by functional importance using data from 37 fragment screening experiments encompassing 1,309 protein structures binding to 1,601 ligands [9]:

Site Definition: Define ligand binding sites based on protein-ligand interaction residues rather than ligand superposition, identifying 293 unique ligand binding sites across the dataset.

Cluster Analysis: Perform unsupervised clustering based on relative solvent accessibility (RSA) profiles, yielding four distinct clusters (C1-C4) with characteristic properties [9].

Constraint Integration: Incorporate MES values and evolutionary conservation (NShenkin) to characterize functional potential of each cluster.

Functional Validation: Assess cluster enrichment with known functional sites, finding C1 (buried, conserved, missense-depleted) sites 28 times more likely to be functional than C4 (accessible, divergent, missense-enriched) sites [9].

Machine Learning Classification: Train multi-layer perceptron and K-nearest neighbors models to predict cluster labels for novel binding sites with 96% and 100% accuracy, respectively [9].

Table 3: Ligand Binding Site Clusters Characterized by MES and Evolutionary Features

| Cluster | Size (residues) | RSA Profile | MES Profile | Evolutionary Conservation | Functional Likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 15 (avg) | Buried (68% RSA<25%) | Depleted (-0.17) | High (58% NShenkin<25) | 28× higher vs C4 |

| C2 | 11 (avg) | Intermediate (47% RSA<25%) | Mildly Depleted (-0.07) | Moderate (45% NShenkin<25) | Intermediate |

| C3 | 8 (avg) | Accessible (30% RSA<25%) | Neutral (-0.02) | Divergent (33% NShenkin<25) | Low |

| C4 | 5 (avg) | Highly Accessible (10% RSA<25%) | Enriched (+0.06) | Highly Divergent (31% NShenkin<25) | Baseline |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for MES Analysis

| Resource | Type | Function in MES Research | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| gnomAD | Population variant database | Source of human missense variants for constraint calculation | https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/ |

| Pfam | Protein family database | Domain definitions and multiple sequence alignments | http://pfam.xfam.org/ |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structural database | 3D structures for structural feature annotation | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| ClinVar | Pathogenic variant database | Validation set for pathogenic variant associations | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/ |

| MES Calculation Code | Computational method | Implementation of MES algorithm | Supplementary materials [8] |

Visualizations

MES Calculation and Classification Workflow

Conservation Plane Analysis

Discussion and Future Directions

The development of MES represents a significant advance in residue-level constraint quantification, providing a human-population-specific complement to deep evolutionary conservation metrics. The integration of these dual perspectives creates a powerful framework for identifying functionally critical residues through the "conservation plane" classification system [8]. This approach successfully discriminates between residue types based on their structural and functional roles, with particular value for identifying functional sites that might be overlooked using evolutionary conservation alone.

In practical applications, MES has demonstrated particular utility in functional binding site classification, where it helps distinguish biologically relevant ligand interactions from potentially spurious binding events [9]. The combination of MES with structural features like solvent accessibility and evolutionary conservation creates a robust predictive framework for identifying functionally important sites, with machine learning models achieving remarkable classification accuracy [9].

For the drug discovery community, MES offers valuable insights for prioritizing target sites and interpreting the potential functional impact of genetic variants. The identification of clinical variant hot spots at missense-enriched positions suggests novel mechanisms of pathogenicity that warrant further investigation [8]. Future applications of MES may expand to include pan-cancer genomics analyses, where mutation enrichment region detection methods like geMER could integrate population constraint metrics to refine driver mutation identification [10].

As population sequencing datasets continue to expand in size and diversity, the resolution and applicability of MES will further improve. Integration with emerging protein language models and structural prediction tools like AlphaFold may create even more powerful frameworks for predicting variant effects and identifying functionally critical residues. The continued development and application of MES promises to enhance our understanding of protein structure-function relationships and accelerate therapeutic development through improved variant interpretation.

Within the framework of comparative methods for evolutionary constraint analysis, a central goal is to understand the selective pressures that shape protein sequences and structures. The patterns of residue conservation and variation observed in multiple sequence alignments are not random; they are direct readouts of structural and functional constraints. This review synthesizes current research on how these evolutionary signatures correlate with key structural features—namely, buried residues and binding sites—and how they inform the interpretation of pathogenic variants. The integration of large-scale population genetics data, such as that from gnomAD, with evolutionary conservation metrics now allows for an unprecedented residue-level analysis of constraint, revealing a complex landscape where selective pressures operate with remarkable consistency across different biological timescales [1].

Evolutionary and Population Constraint: A Unified Framework

Defining Constraint Through Comparative Analysis

Evolutionary constraint refers to the limitation on acceptable amino acid substitutions at a given position in a protein, imposed by the requirement to maintain proper structure and function. The core principle is that residues critical for folding, stability, or interaction are evolutionarily conserved, meaning they show little variation across homologous proteins from different species. This conservation is routinely quantified using metrics like Shenkin's diversity score derived from deep multiple sequence alignments of protein families [1]. Comparative analyses leverage phylogenetic relationships to partition phenotypic variance into heritable phylogenetic components and non-heritable residuals, providing unbiased estimates of evolutionary constraints free from the confounding effects of shared ancestry [11].

The Emergence of Population Constraint

A more recent development is the concept of population constraint, which analyzes the distribution of genetic variants within a single species, such as humans. The underlying hypothesis is that the same structural features that constrain evolutionary variation over deep time should also influence the spectrum of polymorphisms observed in a population. However, systematic confirmation of this relationship required large-scale population sequencing efforts like gnomAD, which provides a catalog of millions of human genetic variants [1]. The distribution of missense variants in humans is strongly influenced by protein structure, with features like core residues, catalytic sites, and interfaces showing clear evidence of constraint in aggregate [1].

The Missense Enrichment Score (MES)

To quantify residue-level population constraint, a novel Missense Enrichment Score (MES) has been developed. This score maps millions of population missense variants to protein domain families and quantifies constraint at each aligned position. The MES has two components: an odds ratio of a position's missense variation rate compared to the rest of the domain, and a p-value indicating the statistical significance of this deviation. Residues are subsequently classified as:

- Missense-depleted: MES < 1; p < 0.1 (under strong constraint)

- Missense-enriched: MES > 1; p < 0.1 (under weak constraint)

- Missense-neutral: p ≥ 0.1 [1]

This approach has identified approximately 5,086 missense-depleted positions across 766 protein families, covering over 365,000 residues in the human proteome, which are considered under strong structural constraint [1].

Structural Features as Determinants of Constraint

Solvent Accessibility and Buried Residues

A fundamental structural determinant of evolutionary constraint is solvent accessibility. Residues buried in the protein core are typically under strong selective pressure because they are critical for maintaining structural integrity through hydrophobic interactions and precise packing. Analyses of thousands of protein structures reveal that missense-depleted sites are overwhelmingly enriched in buried residues, while missense-enriched sites tend to be surface-exposed. The relationship between solvent accessibility and constraint is highly statistically significant (χ² = 1285, df = 4, p ≈ 0, n = 105,385) [1].

Table 1: Association Between Structural Features and Constraint Types

| Structural Feature | Evolutionary Conservation | Population Constraint (MES) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buried Residues | Strongly enriched | Strongly missense-depleted | χ² = 1285, p ≈ 0 [1] |

| Ligand Binding Sites | Strongly enriched | Strongly missense-depleted | High significance [1] |

| Protein-Protein Interfaces | Enriched | Missense-depleted (surface only) | High significance [1] |

| Catalytic Sites | Enriched but may deviate from structural constraints | Not explicitly reported | Functional constraints override structural constraints [12] |

Binding Sites and Molecular Interactions

Beyond the protein core, functional sites involved in molecular interactions show distinct constraint patterns:

Ligand Binding Sites: Residues that coordinate small molecules or ligands are strongly constrained in both evolutionary and population contexts. The effect is particularly pronounced at surface sites, where external interactions represent the primary constraint rather than structural packing requirements [1].

Protein-Protein Interfaces: Analysis of an atomic-resolution interactome network comprising 3,398 interactions between 2,890 proteins reveals that in-frame pathogenic variations are enriched at protein-protein interaction interfaces. These interface residues experience a significant decrease in accessible surface area upon binding and are under strong selective pressure [13].

Catalytic Sites: Interestingly, catalytic residues in enzymes often exhibit constraints that deviate from purely structural considerations. While generally conserved, these sites may contain polar or charged residues in hydrophobic environments, representing cases where functional constraints override structural optimization [12].

Methodological Approaches for Constraint Analysis

Experimental Protocols for Large-Scale Constraint Mapping

Variant Annotation and Mapping: The foundational protocol for residue-level constraint analysis begins with mapping population variants (e.g., from gnomAD) to protein domain families from databases like Pfam. This process involves:

- Annotating variants with Ensembl's Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) to determine affected transcripts, genes, and proteins.

- Mapping variants to multiple sequence alignments of protein domains to identify homologous positions.

- Calculating constraint metrics (e.g., MES) for each aligned position by comparing variant rates within and across domains [1] [14].

Structural Feature Annotation:

- Solvent Accessibility: Calculated using tools like Naccess, which uses a water molecule of diameter 1.4 Å as a probe to determine accessible surface areas. Residues with less than 15% accessibility are typically classified as buried [13].

- Interaction Interfaces: Determined from cocrystal structures by comparing solvent accessibility in bound and unbound states. Residues whose relative accessibility changes by more than 1 Ų upon binding are classified as interface residues [13].

- Binding Sites: Annotated using databases like Catalytic Site Atlas (CSA) for enzymatic residues or through structural analysis of ligand-binding pockets [12].

Computational Framework for Functional Characterization

The FunC-ESMs (Functional Characterisation via Evolutionary Scale Models) framework provides a methodology for classifying loss-of-function variants into mechanistic groups:

- Sequence-based constraint: Uses ESM-1b protein language model to assess evolutionary constraint without multiple sequence alignments.

- Stability impact prediction: Uses ESM-IF (Inverse Folding) model to assess variant effects on protein stability using AlphaFold2-predicted structures.

- Mechanistic classification: Combines these scores to classify variants as:

- 'WT-like' (non-deleterious)

- 'total-loss' (destabilizing, affecting both stability and function)

- 'stable-but-inactive' (affecting function directly without destabilization) [15]

Visualization of Constraint Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships and analytical workflow for studying structural correlates of constraint.

Diagram 1: Structural correlates of constraint analysis framework. This workflow illustrates how structural features shape both evolutionary and population constraints, which collectively inform the interpretation of pathogenic variants. Analytical methods like MES analysis and phylogenetic comparative methods quantify these relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Resources for Constraint Analysis

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| gnomAD [1] | Database | Catalog of human population genetic variation | Serves as foundation for calculating population constraint metrics |

| Pfam [1] | Database | Curated protein domain families | Provides multiple sequence alignments for comparative analysis |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] | Database | Experimentally determined protein structures | Enables mapping of variants to structural features |

| Missense Enrichment Score (MES) [1] | Analytical Metric | Quantifies residue-level population constraint | Identifies missense-depleted/enriched positions in protein domains |

| AlphaFold2 [16] [14] | Computational Tool | Predicts protein 3D structures from sequence | Provides structural models when experimental structures unavailable |

| FunC-ESMs [15] | Computational Framework | Classifies loss-of-function variant mechanisms | Differentiates stability vs. function-disrupting variants |

| FoldX [16] | Computational Tool | Predicts protein stability changes from structure | Calculates ΔΔG values for missense variants |

| Naccess [13] | Computational Tool | Calculates solvent accessibility | Classifies residues as buried or exposed |

| Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) [14] | Database | Catalog of disease-associated variants | Provides pathogenic variants for training and validation |

Pathogenic Variants and Clinical Implications

Contrasting LOF and GOF Mechanisms

Pathogenic variants can cause disease through distinct molecular mechanisms: loss-of-function (LOF) variants diminish or abolish protein activity, while gain-of-function (GOF) variants confer new or enhanced activities. These different mechanisms can produce contrasting phenotypes even within the same gene. Computational tools like LoGoFunc leverage ensemble machine learning on diverse feature sets to discriminate between pathogenic GOF, LOF, and neutral variants genome-wide [14].

Approximately half of all disease-associated missense variants cause loss of function through protein destabilization, reducing protein abundance, while the remainder directly disrupt functional interactions without affecting stability [15]. This distinction has important implications for therapeutic strategies, as stabilizing a misfolded protein requires different approaches than restoring a specific functional interaction.

Structural Biology in Variant Interpretation

Structural biology provides a powerful lens for variant interpretation by offering physical insights into how variants affect protein structure and function. Key considerations include:

- Structure Selection: High-resolution structures from X-ray crystallography are preferred, though AlphaFold2 models now provide adequate alternatives for many applications [16].

- Stability Metrics: Tools like FoldX calculate changes in Gibbs free energy (ΔΔG) to quantify variant effects on stability, incorporating van der Waals, solvation, hydrogen bonding, electrostatics, and entropy effects [16].

- Interface Analysis: Pathogenic variations are enriched at protein-protein interaction interfaces, with the most disruptive variants occurring at "hot-spot" residues critical for binding affinity and specificity [13].

The integration of evolutionary constraint analysis with structural biology has created a powerful framework for understanding how selective pressures shape protein sequences and structures. Buried residues and binding sites emerge as key structural correlates of constraint, with consistent patterns observed across both deep evolutionary timescales and recent human population history. The development of novel metrics like the Missense Enrichment Score and computational frameworks like FunC-ESMs now enables residue-level characterization of constraint, providing mechanistic insights into variant pathogenicity. As structural coverage expands through experimental determination and AI-based prediction, and as population genetic datasets grow increasingly comprehensive, our ability to decipher the structural language of constraint will continue to refine, offering new opportunities for understanding genetic disease and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

The interpretation of genetic variation represents a central challenge in modern genomics, particularly for distinguishing pathogenic mutations from benign polymorphisms. This challenge is inherently framed by two contrasting timescales: deep evolutionary conservation, which reflects billions of years of functional constraint across the tree of life, and recent human population variation, which captures patterns of selection within our species. Evolutionary conservation provides a powerful signal for identifying functionally critical regions in proteins, while population genetics reveals which variations are tolerated in contemporary human populations. The integration of these complementary temporal scales enables researchers to calibrate variant effect predictions across the entire human proteome, addressing a critical limitation in current genomic interpretation methods. This technical guide examines the conceptual framework, methodological approaches, and practical applications for combining these timescales in evolutionary constraint analysis, with particular emphasis on advancing rare disease diagnosis and therapeutic target identification.

Theoretical Framework: Bridging Evolutionary Timescales

The Timescale Dichotomy in Genetic Analysis

The analysis of genetic variation operates across vastly different temporal scales, each providing distinct insights into functional constraint:

Deep Evolutionary Conservation: Patterns of sequence preservation across billions of years of evolutionary history provide information about structural and functional constraints on proteins. Variants at positions that have remained unchanged across diverse lineages are more likely to disrupt protein function when altered [17].

Recent Human Population Variation: The distribution of variants in contemporary human populations, as cataloged in resources such as gnomAD and UK Biobank, reveals which genetic changes have been tolerated in recent human evolutionary history [17]. The absence of certain variants in population databases may indicate strong negative selection against them.

These timescales offer complementary information: deep evolutionary data identifies what mutations are theoretically possible for a protein to maintain function, while human population data reveals which of these possible mutations have been compatible with human health and reproduction.

Integrated Models for Variant Interpretation

Advanced computational models now bridge these timescales by combining evolutionary sequences with human population data. The popEVE model exemplifies this approach, integrating a deep generative model trained on evolutionary sequences (EVE) with a large language model (ESM-1v) and human population frequencies from UK Biobank and gnomAD [17] [18]. This unified framework produces calibrated variant effect scores that enable comparison across different proteins, addressing a critical limitation in variant effect prediction where previous methods excelled within genes but failed to provide proteome-wide comparability [17].

Table 1: Data Sources for Multi-Timescale Evolutionary Analysis

| Data Type | Timescale | Representative Sources | Information Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignments | Deep evolutionary (billions of years) | EVE model [17] | Patterns of amino acid conservation across diverse species |

| Protein Language Models | Deep evolutionary | ESM-1v [17] | Evolutionary constraints learned from amino acid sequences |

| Human Population Databases | Recent evolutionary (thousands of years) | gnomAD, UK Biobank [17] | Frequency and distribution of variants in human populations |

| Clinical Variant Databases | Contemporary | ClinVar [17] | Curated pathogenic and benign variants for validation |

Methodological Approaches

The popEVE Integrated Framework

The popEVE model architecture demonstrates how deep evolutionary and recent population data can be formally integrated:

Evolutionary Component:

- Utilizes EVE, a deep generative model trained on evolutionary sequences across diverse species

- Incorporates ESM-1v, a protein language model that learns evolutionary constraints from amino acid sequences

- Generates initial variant effect predictions based on deep evolutionary patterns [17] [18]

Population Genetics Component:

- Incorporates summary statistics of human variation from UK Biobank (approximately 500,000 individuals) and gnomAD version 2

- Uses a latent Gaussian process prior to transform evolutionary scores to reflect human-specific constraint

- Trains on "seen" versus "not seen" variants in human populations rather than allele frequencies to minimize population structure bias [17]

Integration Methodology:

- Combines evolutionary and population components using a Bayesian framework

- Produces a continuous measure of variant deleteriousness comparable across different proteins

- Maintains missense-resolution within genes while enabling cross-gene comparison [17]

Experimental Protocol for Model Validation

The validation of integrated models requires rigorous testing across multiple dimensions:

Clinical Validation:

- Benchmark against curated clinical variant databases (e.g., ClinVar) for classification accuracy

- Test ability to distinguish pathogenic from benign variants [17]

- Evaluate performance in known disease genes versus genes without previous annotation

Severity Discrimination:

- Assess capability to distinguish variants causing severe childhood-onset disorders from those with adult-onset or milder effects

- Test enrichment of deleterious scores in severe developmental disorder cohorts versus controls [17]

Population Bias Assessment:

- Compare score distributions across different ancestral groups in gnomAD

- Evaluate potential overprediction of deleterious variants in underrepresented populations [17]

Functional Validation:

- Correlate model scores with high-throughput experimental data from deep mutational scanning studies

- Test predictions against functional assays for specific protein classes [17]

Figure 1: Integrated Framework for Evolutionary Constraint Analysis Combining Deep Evolutionary and Recent Human Population Data

Quantitative Results and Performance Metrics

Performance Benchmarks

The popEVE model has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across multiple benchmarking tasks:

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Integrated Evolutionary Constraint Models

| Benchmark Category | Metric | popEVE Performance | Comparison to Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Classification | Separation of pathogenic vs. benign variants in ClinVar | Competitive with leading methods [17] | Comparable to models trained specifically on clinical labels |

| Severity Discrimination | Distinguishing childhood death-associated vs. adult death variants | Significant separation (P < 0.001) [17] | Outperforms allele frequency-tuned and clinically-trained models |

| Cohort Enrichment | Enrichment of deleterious variants in severe developmental disorder (SDD) cases vs. controls | 15-fold enrichment at high-confidence threshold [17] | 5× higher than previously identified in same cohort |

| Novel Gene Discovery | Identification of novel candidate genes in undiagnosed SDD cohort | 123 novel candidates (442 total genes) [17] | 4.4× more than previously identified |

| Population Bias | Distribution similarity across ancestries in gnomAD | Minimal bias observed [17] | Shows less bias than frequency-dependent methods |

Application to Severe Developmental Disorders

In a metacohort of 31,058 patients with severe developmental disorders, the integrated evolutionary constraint approach demonstrated significant clinical utility:

- Analysis of de novo missense variants revealed a pronounced shift toward higher predicted deleteriousness in cases compared to unaffected controls [17]

- The model identified variants in 442 genes associated with severe developmental disorders, including 123 novel candidates not previously linked to these conditions [17]

- These novel candidate genes showed functional similarity to known developmental disease genes, supporting their potential pathogenic role [17]

- Using a label-free two-component Gaussian mixture model, a high-confidence severity threshold was established at -5.056, where variants below this threshold have a 99.99% probability of being highly deleterious [17]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Evolutionary Constraint Analysis

| Resource | Type | Function in Analysis | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| gnomAD (v2.0) | Population database | Provides allele frequency data across diverse human populations | Available at gnomad.broadinstitute.org |

| UK Biobank | Population cohort | Offers deep phenotypic data alongside genetic information | Available to approved researchers via ukbiobank.ac.uk |

| EVE Model | Computational model | Provides evolutionary-based variant effect predictions | Available through original publication or implementation |

| ESM-1v | Protein language model | Delivers unsupervised variant effect predictions | Available through GitHub repository |

| ClinVar | Clinical database | Curated resource for clinical variant interpretation | Available at ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/ |

| ProtVar | Protein database | Integrates popEVE scores for variant interpretation | Available at www.ebi.ac.uk/protvar |

Discussion and Future Directions

Advantages of Integrated Timescale Analysis

The combination of deep evolutionary and recent human population data addresses several critical limitations in variant interpretation:

Proteome-Wide Calibration: By leveraging population data to calibrate evolutionary scores, integrated models enable meaningful comparison of variant deleteriousness across different genes, addressing a fundamental challenge in clinical genomics [17].

Ancestry Bias Mitigation: Using coarse presence/absence measures of variation rather than precise allele frequencies helps minimize the introduction of population structure biases that plague some frequency-dependent methods [17].

Functional Insight: The complementary nature of these timescales provides insight into both molecular function (from evolutionary data) and organismal fitness (from population data), offering a more complete picture of variant impact [17].

Implementation Considerations

Clinical Translation:

- Integrated models show promise for diagnosing rare genetic diseases, particularly in cases without parental sequencing data

- The ability to prioritize likely causal variants using only child exomes expands diagnostic possibilities [17] [18]

- Clinical implementation requires careful validation and consideration of model limitations

Technical Challenges:

- Balancing evolutionary and population signals requires sophisticated statistical frameworks

- Population data availability across diverse ancestries remains limited

- Integration with functional genomic data represents an important future direction

Figure 2: Clinical Variant Interpretation Workflow Leveraging Multiple Evolutionary Timescales

The integration of deep evolutionary conservation data with recent human population variation represents a transformative approach for interpreting genetic variants and understanding evolutionary constraints. By bridging these contrasting timescales, models like popEVE provide calibrated, proteome-wide variant effect predictions that enable more accurate genetic diagnosis, particularly for rare diseases. This integrated framework offers significant advantages over methods relying on single timescales, including improved severity discrimination, reduced ancestry bias, and enhanced discovery of novel disease genes. As genomic data continues to expand across diverse populations and species, further refinement of these integrated approaches will accelerate both clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development, ultimately improving patient outcomes across a spectrum of genetic disorders.

From Theory to Toolbox: Computational Methods and Their Biomedical Applications

Leveraging Evolutionary Signals in AlphaFold2 for Conformational Ensemble Prediction

AlphaFold2 (AF2) has revolutionized structural biology by providing high-accuracy protein structure predictions. However, its native implementation is optimized for predicting single, static conformations, failing to capture the dynamic ensembles essential for biological function. This technical guide explores advanced methodologies that leverage evolutionary constraints to coax AF2 into predicting alternative conformational states. By moving beyond the single-sequence paradigm and strategically manipulating the multiple sequence alignment (MSA)—the primary source of evolutionary information for AF2—researchers can uncover the rich landscape of protein dynamics. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the core principles, compares state-of-the-art techniques with quantitative benchmarks, and offers detailed protocols for implementing these methods, framing them within comparative research on evolutionary constraint analysis.

The groundbreaking performance of AlphaFold2 in CASP14 demonstrated an unprecedented ability to decode the protein folding problem, achieving a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.8 Å between predicted and experimental backbone structures [19]. Despite this remarkable accuracy for single-state prediction, a fundamental limitation persists: proteins are dynamic entities that sample multiple conformational states to perform their biological functions. The default AF2 architecture, particularly its EvoFormer module, is designed to distill evolutionary couplings from the MSA into a single dominant conformation, often corresponding to the most thermodynamically stable state or the one with the strongest co-evolutionary signal [20] [19].

This whitepaper addresses this critical limitation by systematizing methods that exploit the evolutionary information embedded within MSAs to guide AF2 toward predicting conformational ensembles. The core hypothesis unifying these approaches is that AF2 predictions are biased toward conformations with prominent coevolutionary signals in the MSA, rather than necessarily favoring the most thermodynamically stable state. This bias stems from the interplay between competing coevolutionary signals within the alignment, which correspond to distinct structural states and influence the predicted conformation [20]. By strategically manipulating the MSA, researchers can alter the balance of these evolutionary constraints, thereby unlocking predictions of alternative functional states.

Core Methodologies and Quantitative Comparison

Several principled methodologies have been developed to manipulate MSAs for ensemble prediction. The table below summarizes the core mechanisms, advantages, and limitations of the primary approaches.

Table 1: Core Methodologies for Leveraging Evolutionary Signals in AF2

| Method | Core Mechanism | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSA Clustering [20] | Partitions MSA into sub-alignments based on sequence similarity or evolutionary representations, running AF2 on each cluster. | High interpretability; directly links sequence subgroups to structural states; enables Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA). | Computationally intensive (multiple AF2 runs); performance depends on clustering quality and MSA depth. |

| MSA Masking (AFsample2) [21] | Randomly replaces columns in the MSA with a generic token ("X"), deliberately diluting co-evolutionary signals. | No prior knowledge needed; integrated into inference for efficiency; generates a continuum of states including intermediates. | Reduced pLDDT with increased masking; optimal masking level is target-dependent. |

| Paired MSA Construction (DeepSCFold) [22] | For complexes, constructs deep paired MSAs using predicted structural complementarity and interaction probability. | Captures inter-chain co-evolution; improves complex structure prediction where sequence co-evolution is weak. | Primarily applied to complexes; requires sophisticated sequence-based deep learning models. |

| Experimental Guidance (DEERFold) [23] | Fine-tunes AF2 on experimental distance distributions (e.g., from DEER spectroscopy) to incorporate external constraints. | Integrates empirical data; can guide predictions toward specific, biologically relevant states. | Requires experimental data; specialized implementation beyond standard AF2. |

The performance of these methods can be quantified using metrics like Template Modeling (TM)-score and Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) against known experimental structures of different states. The following table summarizes benchmark results from key studies, demonstrating the tangible improvements these methods offer.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Benchmarks of Advanced AF2 Methods

| Method & Study | Test System | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFsample2 (15% masking) [21] | OC23 Dataset (23 open/closed proteins) | TM-score improvement for alternate state | ΔTM > 0.05 for 9/23 cases; some improvements from 0.58 to 0.98 |

| AFsample2 [21] | Membrane Protein Transporters (16 targets) | TM-score improvement for alternate state | 11/16 targets showed substantial improvement |

| AHC Clustering [20] | Fold-switching Proteins (8 targets) | Successful identification of alternative folds | Consistently identified a larger fraction of alternative conformations vs. DBSCAN |

| AHC Clustering [20] | Extended Fold-switching Set (81 proteins) | Successful identification of fold-switching events | Identified 26 vs. 18 events detected by a previous benchmark |

| DeepSCFold [22] | CASP15 Multimer Targets | TM-score improvement vs. AF-Multimer & AF3 | 11.6% and 10.3% improvement, respectively |

| DeepSCFold [22] | SAbDab Antibody-Antigen Complexes | Success rate for binding interface prediction | 24.7% and 12.4% improvement over AF-Multimer and AF3 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC) of MSA

This protocol overcomes the limitations of density-based clustering (e.g., DBSCAN), which often produces a highly fragmented landscape of small clusters, by creating larger, more cohesive clusters suitable for downstream evolutionary analysis [20].

Workflow Overview:

The following diagram illustrates the complete AHC clustering and analysis pipeline.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Begin with a deep multiple sequence alignment (MSA) for the protein of interest. A depth of hundreds to thousands of sequences is typically required for robust clustering.

- Generate Sequence Representations: Transition from raw sequences to a structured, continuous latent space. Use a protein language model like the MSA Transformer to generate per-sequence embeddings. This leverages attention mechanisms to integrate evolutionary information across the alignment, capturing residue-level dependencies [20].

- Perform Clustering: Apply Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC) to the sequence representations. AHC is preferred over density-based methods as it reduces fragmentation and avoids misclassifying sequences as noise, leading to fewer but larger and more coherent clusters [20].

- Cluster Selection and AF2 Execution: Select a manageable number of large, cohesive clusters (e.g., 3-5) representing the major sequence lineages. Use each cluster's sub-alignment as independent input for AlphaFold2 to generate a set of candidate structures.

- Downstream Evolutionary Analysis (Direct Coupling Analysis): The larger clusters generated by AHC provide sufficient sequence data for reliable statistical analysis. Apply Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA) to the MSA of a cluster producing an alternative conformation. DCA identifies pairs of residues (co-evolving pairs) with strong statistical couplings, which often represent intramolecular contacts crucial for stabilizing the alternative state [20].

- Rational Mutation Design: Leverage the identified co-evolving residues to design targeted mutations. The goal is to create mutations that preferentially stabilize a specific conformation by shifting the conformational equilibrium. This can be validated computationally using alchemical free energy calculations from Molecular Dynamics (MD) or experimentally [20].

Protocol 2: AFsample2 with MSA Column Masking

This protocol uses random masking of MSA columns to break co-evolutionary constraints, encouraging AF2 to explore alternative conformational solutions without any prior structural knowledge [21].

Workflow Overview:

The AFsample2 pipeline integrates MSA masking directly into the AF2 inference process.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- MSA Generation: Query standard sequence databases (e.g., with Jackhammer/MMseqs2) to generate a deep MSA for the target protein [21].

- Stochastic Masking: For each model to be generated, create a uniquely masked version of the MSA by randomly replacing a defined fraction of alignment columns with a generic token ("X"). Critically, the first row (the target sequence) is never masked. A masking level of 15% is a robust starting point, but performance can be optimized by testing between 5% and 20% [21].

- Diverse Sampling: Run the AF2 inference process for each uniquely masked MSA. Ensure that dropout layers are activated during inference to further enhance stochasticity and diversity.

- Ensemble Analysis: Generate a large number of models (e.g., 100+). The resulting ensemble will contain a spectrum of conformations. Use clustering (e.g., based on RMSD) and confidence metrics (pLDDT) to identify representative models for major states (e.g., open, closed) and potential intermediate conformations [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of these advanced AF2 protocols relies on a suite of computational tools and resources. The following table catalogs the key components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| MSA Transformer [20] | Protein Language Model | Generates evolutionary-aware sequence representations for improved MSA clustering. |

| Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering [20] | Algorithm | Groups MSA sequences into large, coherent clusters based on sequence or embedding similarity. |

| Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA) [20] | Statistical Framework | Identifies strongly co-evolving residue pairs from an MSA, indicating structural contacts. |

| Alchemical MD Simulations [20] | Validation Method | Computes free energy changes for designed mutations, validating their stabilizing effect. |

| OpenFold [23] | Trainable Framework | Provides a PyTorch-based, trainable reproduction of AF2 for method development (e.g., DEERFold). |

| AlphaFold-Multimer [22] | Software | The base model for predicting protein complex structures, used by methods like DeepSCFold. |

| DEER Spectroscopy [23] | Experimental Method | Provides experimental distance distributions between spin labels to guide structure prediction. |

| DeepSCFold Models (pSS-score, pIA-score) [22] | Deep Learning Model | Predicts structural similarity and interaction probability from sequence to build paired MSAs. |

The methodologies detailed in this guide represent a paradigm shift in the use of AlphaFold2, transforming it from a static structure predictor into a powerful tool for exploring protein dynamics. The strategic manipulation of evolutionary constraints via MSA clustering, masking, and pairing provides a principled and interpretable path to conformational ensembles. The integration of these computational predictions with experimental data and biophysical simulations, as seen in DEERFold and DCA-driven mutation validation, creates a powerful, cyclical workflow for structural biology.

Looking forward, the field is moving toward a more integrated approach. Combining the strengths of different methods—for instance, using MSA clustering to identify major states and MSA masking to sample the pathways between them—holds great promise. Furthermore, the development of unified frameworks that can seamlessly incorporate diverse evolutionary and experimental constraints will be crucial for modeling complex biological phenomena such as allosteric regulation and multi-domain dynamics. By leveraging evolutionary signals not as a path to a single answer but as a map of evolutionary possibilities, researchers can now computationally dissect the structural landscapes that underpin protein function, with profound implications for fundamental biology and rational drug design.

Advanced Clustering Strategies for Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs)

Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) serve as the foundational data for comparative methods in evolutionary biology, enabling researchers to infer homology, phylogenetic relationships, and evolutionary constraints. The accuracy of downstream analyses—including phylogenetic tree estimation, detection of adaptive evolution, and identification of structural constraints—is critically dependent on the quality of the underlying MSA [24]. Errors in homology assignment within MSAs are known to propagate, causing a range of problems from false inference of positive selection to long-branch attraction artifacts in phylogenetic trees [24]. Advanced clustering strategies have emerged as powerful computational techniques to deconvolve complex evolutionary signals embedded within MSAs, thereby mitigating these errors and revealing nuanced biological insights.

The integration of these strategies within a framework of evolutionary constraint analysis allows researchers to move beyond treating the MSA as a fixed, error-free input. Instead, clustering facilitates a more sophisticated interrogation of the alignment, identifying subgroups of sequences or homologies that reflect alternative evolutionary trajectories, conformational states, or structural constraints [25] [24]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to state-of-the-art clustering methodologies for MSAs, detailing their protocols, applications, and implementation for a audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Role of Clustering in MSA Analysis

Clustering in MSA analysis moves beyond traditional filtering by strategically grouping sequences or homologous sites to enhance the biological signal-to-noise ratio. Traditional MSA methods often produce a single, monolithic alignment that may obscure underlying heterogeneity, such as the presence of multiple protein conformations or non-orthologous sequences. Clustering addresses this by segmenting the MSA based on specific criteria, enabling more precise evolutionary and structural analyses.

Key applications of clustering in MSA analysis include:

- Deconvolving Evolutionary Couplings: Identifying subsets of sequences within an MSA that possess distinct sets of co-evolved residues, which can correspond to different conformational substates or functional specificities [25].

- Managing MSA Uncertainty: Replacing the practice of filtering out entire alignment columns with a more nuanced approach that identifies high-confidence clusters of homologous residues within columns, thus preserving more true homologies while removing false positives [24].

- Enhancing Structural Prediction: By providing a curated, coherent set of sequences as input, clustering allows advanced deep-learning tools like AlphaFold2 to predict alternative protein conformations with high confidence, a task often failed when using the full, heterogeneous MSA [25].

- Quantifying Structural Diversity: Clustering predicted secondary structures from an MSA provides a direct measure of structural conservation or diversity among homologous sequences, indicating functional importance or structural liability [26].

Core Clustering Methodologies

AF-Cluster: Predicting Multiple Conformations