CMA-ES vs. Traditional Evolution Strategies: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

This article provides a thorough comparative analysis of the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) and traditional Evolution Strategies (ES), tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

CMA-ES vs. Traditional Evolution Strategies: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a thorough comparative analysis of the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) and traditional Evolution Strategies (ES), tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of both algorithms, delves into advanced methodological adaptations and their direct applications in cheminformatics and molecular optimization, addresses critical troubleshooting and performance optimization techniques, and presents empirical validation across biomedical benchmarks. The synthesis offers actionable insights for selecting and implementing these powerful optimization tools to accelerate drug discovery pipelines, enhance molecular design, and improve predictive modeling outcomes.

From Simple Mutations to Adaptive Covariance: Core Principles of ES and CMA-ES

In the field of derivative-free optimization, Traditional Evolution Strategies (ES) establish a fundamental "guess and check" framework for navigating complex parameter spaces where gradient information is unavailable or unreliable. As a subclass of evolutionary algorithms, ES operates on a simple yet powerful principle: it iteratively generates candidate solutions, evaluates their performance, and uses the best-performing candidates to inform subsequent search directions [1] [2]. This approach stands in stark contrast to gradient-based methods that require backpropagation or analytical derivative information, making ES particularly valuable for optimization problems characterized by non-convex landscapes, noisy evaluations, or non-differentiable objective functions [3] [4].

Within the broader context of CMA-ES versus traditional evolution strategies research, understanding this foundational approach is crucial for appreciating the algorithmic advances represented by Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategies. While CMA-ES introduces sophisticated adaptation mechanisms for the covariance matrix of its search distribution, traditional ES implementations typically rely on fixed or simpler adaptive structures for their sampling distributions [5] [4]. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance characteristics, implementation methodologies, and experimental protocols that define traditional evolution strategies as a scalable alternative for challenging optimization problems in research and industrial applications, including computational drug development where simulation-based fitness evaluations are common.

Core Algorithmic Framework and Mechanisms

The Basic "Guess and Check" Methodology

The operational paradigm of traditional Evolution Strategies can be conceptualized as a "guess and check" process in parameter space [3]. Unlike reinforcement learning which performs "guess and check" in action space, ES operates directly on the parameters θ of the function being optimized. The algorithm maintains a probability distribution over potential solutions, typically implemented as a multivariate Gaussian distribution characterized by a mean vector μ and covariance matrix Σ [2]. For a function with n parameters, the search space is ℝⁿ, and the algorithm seeks to find the parameter configuration that maximizes an objective function f(θ) [4].

The fundamental ES workflow proceeds through generations in an iterative loop [1]:

- Guess Phase: Sample a population of candidate solutions from the current distribution: ( D^{(t)} = { θi | θi \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu^{(t)}, \Sigma^{(t)}) } )

- Check Phase: Evaluate the fitness ( f(θ_i) ) for each candidate in the population

- Update Phase: Select the top-performing candidates and update the distribution parameters (μ, Σ) to favor the search directions that produced better solutions

This process continues until convergence criteria are met or computational resources are exhausted. The canonical ES implementation uses natural problem-dependent representations, meaning the problem space and search space are identical [1].

Selection Variants: (μ,λ) and (μ+λ) Strategies

Traditional ES incorporates two primary selection strategies that determine how the parent population for the next generation is formed [1]:

- (μ,λ)-ES: In this approach, μ parents produce λ offspring through mutation and/or recombination, and the next generation is selected exclusively from these λ offspring (ignoring the parents). This strategy is inherently non-elitist and facilitates better exploration of the search space, as it allows the algorithm to escape local optima by discarding previous generations.

- (μ+λ)-ES: This strategy selects the next generation from the union of μ parents and λ offspring, making it elitist as it preserves the best solutions found so far. While this approach guarantees monotonic improvement in fitness, it may potentially lead to premature convergence if the population becomes trapped in local optima.

Research recommends that the ratio λ/μ should be approximately 7, with common settings being μ = λ/2 for (μ,λ)-ES and μ = λ/4 for (μ+λ)-ES [1]. The simplest evolution strategy, (1+1)-ES, uses a single parent that produces a single offspring each generation, with selection determining which solution advances to the next generation [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional ES Selection Variants

| Selection Strategy | Selection Pool | Elitism | Exploration vs. Exploitation | Recommended Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μ,λ)-ES | λ offspring only | Non-elitist | Favors exploration | μ ≈ λ/2 |

| (μ+λ)-ES | μ parents + λ offspring | Elitist | Favors exploitation | μ ≈ λ/4 |

Parameter Space Noise Injection and Self-Adaptation

A distinctive feature of evolution strategies is the injection of noise directly in the parameter space, as opposed to action space noise commonly used in reinforcement learning [3]. In each generation, the algorithm perturbs the current parameter vector with Gaussian noise: ( θ'i = θ + σεi ), where ( ε_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I) ) and σ represents the step size controlling the magnitude of exploration [4].

Traditional ES often implements self-adaptation mechanisms for the mutation step sizes, allowing the algorithm to dynamically adjust its exploration characteristics based on search progress [1]. The step size update typically follows the log-normal rule: ( σ'j = σj \cdot \exp(τ \cdot N(0,1) - τ' \cdot N_j(0,1)) ), where τ and τ' are learning rates controlling the global and individual step size adaptations, respectively [1]. This creates a co-evolutionary process where the algorithm searches simultaneously at two levels: the problem parameters themselves and the step sizes that control the exploration of these parameters.

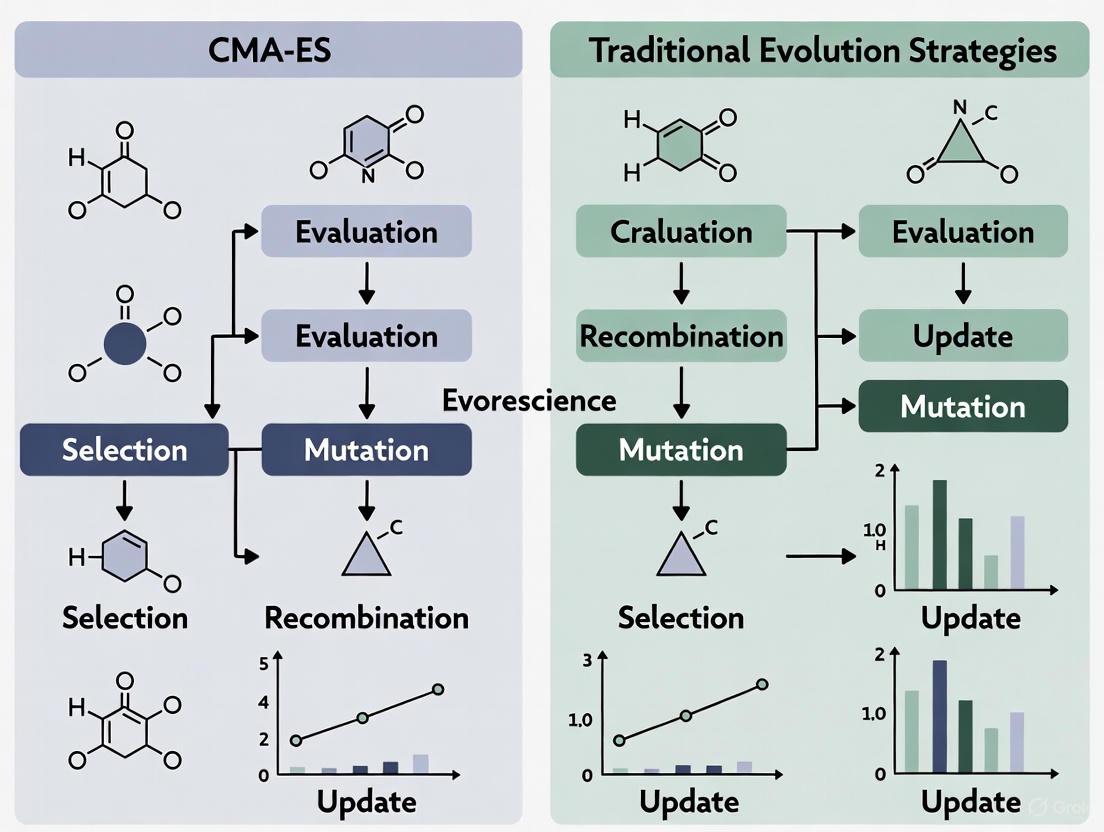

Figure 1: Traditional Evolution Strategies "Guess and Check" Workflow. The algorithm iteratively samples candidate solutions, evaluates their fitness, and updates the sampling distribution based on the best-performing individuals.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarks

Standardized Testing Methodologies

The performance evaluation of traditional evolution strategies typically employs standardized benchmark functions that represent different optimization challenges commonly encountered in real-world applications [5] [6]. These include:

- Unimodal functions (e.g., Sphere, Ellipsoid) for testing basic convergence performance and efficiency

- Multimodal functions (e.g., Rastrigin, Schaffer) with numerous local optima to evaluate the algorithm's ability to escape local minima

- Ill-conditioned and non-separable functions (e.g., Cigar, Rosenbrock) where parameter interactions create complex, curved fitness landscapes

Experimental protocols typically involve multiple independent runs with randomized initializations to account for stochastic variations, with performance measured through convergence graphs (fitness vs. function evaluations) and statistical comparisons of final solution quality [5] [4]. For the (1+1)-ES algorithm, performance can be theoretically analyzed using the convergence rate theory developed by Rechenberg, which provides mathematical expectations for improvement per generation on specific function classes [1].

Comparative Performance Data

In benchmark studies, traditional ES demonstrates competitive performance on modern reinforcement learning benchmarks compared to gradient-based methods, while overcoming several inconveniences of reinforcement learning [3]. When implemented efficiently with parallelization, ES can achieve significant speedups: using 1,440 CPU cores across 80 machines, researchers trained a 3D MuJoCo humanoid walker in only 10 minutes—compared to approximately 10 hours for the A3C algorithm on 32 cores [3]. Similarly, on Atari game benchmarks, ES achieved comparable performance to A3C while reducing training time from 1 day to 1 hour using 720 cores [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Evolution Strategies vs. Reinforcement Learning

| Benchmark Task | Algorithm | Hardware Resources | Training Time | Final Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D MuJoCo Humanoid | ES | 1,440 CPU cores (80 machines) | 10 minutes | Comparable to RL |

| 3D MuJoCo Humanoid | A3C (RL) | 32 CPU cores | 10 hours | Reference level |

| Atari Games | ES | 720 CPU cores | 1 hour | Comparable to A3C |

| Atari Games | A3C (RL) | 32 CPU cores | 24 hours | Reference level |

The performance advantages of ES become particularly pronounced in environments with sparse rewards and when dealing with long time horizons where credit assignment is challenging [3] [4]. Additionally, ES exhibits higher robustness to certain hyperparameter settings compared to RL algorithms; for instance, ES performance remains stable across different frame-skip values in Atari, whereas RL algorithms are highly sensitive to this parameter [3].

Comparative Analysis: Traditional ES vs. CMA-ES

Fundamental Algorithmic Differences

While traditional ES and CMA-ES share the same evolutionary computation foundation, they differ significantly in their adaptation mechanisms for the search distribution. Traditional ES typically employs isotropic Gaussian distributions with possibly individual step sizes for each coordinate, where the covariance matrix remains fixed or undergoes simple scaling adaptations [4] [2]. In contrast, CMA-ES implements a sophisticated covariance matrix adaptation mechanism that models pairwise dependencies between parameters, effectively adapting the search distribution to the local topology of the objective function [4] [2].

This fundamental difference manifests in their search behavior: traditional ES explores the parameter space with a relatively fixed orientation, while CMA-ES dynamically rotates and scales the search distribution based on successful search steps [4]. The CMA-ES adaptation mechanism enables it to approximate the inverse Hessian of the objective function, effectively performing a natural gradient descent that accelerates convergence on ill-conditioned problems [5].

Performance Trade-offs and Application Scenarios

The comparative performance between traditional ES and CMA-ES involves significant trade-offs that must be considered for different application scenarios:

- Computational Complexity: Traditional ES has lower computational requirements with O(n) complexity for sampling and updates, while CMA-ES incurs O(n²) complexity due to covariance matrix operations, making traditional ES more suitable for very high-dimensional problems [6]

- Adaptation Capability: CMA-ES excels at solving ill-conditioned, non-separable problems where parameter interactions create complex fitness landscapes, while traditional ES may struggle with such problems due to its simpler search distribution [5]

- Implementation Simplicity: Traditional ES offers significantly simpler implementation with fewer configuration parameters, making it more accessible for practitioners without deep expertise in evolutionary computation [3]

- Convergence Speed: On simple, separable problems, traditional ES can converge rapidly, while on complex, non-separable problems, CMA-ES typically achieves better solution quality with fewer function evaluations [4]

Table 3: Algorithm Characteristics Comparison: Traditional ES vs. CMA-ES

| Characteristic | Traditional ES | CMA-ES |

|---|---|---|

| Search Distribution | Isotropic or axis-aligned Gaussian | Full multivariate Gaussian with adapted covariance |

| Adaptation Mechanism | Step size (σ) adaptation only | Covariance matrix (C) and step size (σ) adaptation |

| Computational Complexity | O(n) | O(n²) |

| Parameter Interactions | Limited handling of parameter dependencies | Explicit modeling of parameter dependencies |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | High |

| Theoretical Foundation | (1+1)-ES convergence theory | Information geometry, natural gradients |

Figure 2: Algorithm Selection Guide Based on Problem Characteristics. Traditional ES is preferred for high-dimensional problems and when computational efficiency is critical, while CMA-ES excels on complex landscapes with strong parameter interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Algorithmic Components

Implementing and experimenting with traditional evolution strategies requires several key algorithmic components that form the "research reagents" for this optimization methodology:

- Sampling Distribution: The multivariate Gaussian generator ( \mathcal{N}(\mu, \Sigma) ) serves as the core reagent for producing candidate solutions. For traditional ES, this typically involves an isotropic ( \Sigma = \sigma^2 I ) or diagonal covariance structure [4] [2]

- Fitness Evaluation Function: The application-specific objective function f(θ) that measures solution quality. In drug development contexts, this might involve molecular docking simulations or quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models [5]

- Selection Operator: Procedures for identifying promising candidates, typically based on fitness ranking or truncation selection of the top λ individuals [1]

- Step Size Adaptation Mechanism: The self-adaptation rule for adjusting σ, commonly implemented through the log-normal update rule with strategy-specific parameters τ, τ' [1]

- Recombination Operators: Optional mechanisms for combining information from multiple parents, including intermediate (averaging) or discrete (parameter-wise selection) recombination [1]

Experimental Setup and Monitoring Tools

Rigorous experimentation with evolution strategies requires specific monitoring and analysis tools:

- Convergence Metrics: Tracking best fitness, population fitness distribution, step size evolution, and parameter movement across generations [5] [4]

- Restart Mechanisms: Strategies for reinitializing the search when premature convergence is detected, particularly important for multimodal problems [5]

- Parallelization Framework: Distributed computing infrastructure for evaluating population members concurrently, essential for scaling to expensive objective functions [3]

- Benchmark Suite: Standardized test functions with known properties and optimal values for algorithm validation and comparison [5] [6]

For researchers in drug development applying ES to quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling or molecular design, domain-specific reagents include chemical descriptor calculators, molecular docking simulators, and absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) prediction models that serve as the fitness evaluation components within the ES framework [5].

Traditional Evolution Strategies establish a fundamental "guess and check" methodology in parameter space that remains competitively relevant despite the development of more sophisticated variants like CMA-ES. Their strengths lie in conceptual simplicity, favorable parallelization characteristics, and robust performance across diverse problem domains, particularly in high-dimensional settings and when gradient information is unavailable or unreliable [3].

The comparative analysis reveals a clear division of applicability: traditional ES excels in scenarios requiring computational efficiency, implementation simplicity, and scalability to very high dimensions, while CMA-ES provides superior performance on complex, non-separable problems where parameter interactions significantly impact solution quality [5] [4]. For drug development researchers, traditional ES offers a accessible entry point to evolutionary optimization for problems like molecular design and protein engineering, where simulation-based fitness evaluations naturally align with the black-box optimization paradigm [5].

Ongoing research continues to enhance traditional ES through hybrid approaches, surrogate modeling for expensive fitness functions, and improved adaptation mechanisms [5] [7]. Understanding this foundational algorithm provides researchers with both a practical optimization tool and the conceptual framework necessary for comprehending more advanced evolutionary computation techniques in the CMA-ES research domain.

The Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) represents a fundamental breakthrough in numerical optimization, transitioning evolution strategies from simple parameter tuning to actively learning the problem landscape. Unlike traditional evolutionary algorithms that rely on fixed distributions for generating candidate solutions, CMA-ES dynamically adapts its search distribution by learning a full covariance matrix, effectively building an internal model of the objective function's topology [8] [9]. This transformation enables the algorithm to automatically discover favorable search directions, scale step-sizes appropriately, and efficiently navigate ill-conditioned and non-separable problems that challenge conventional approaches [5].

This landscape learning capability positions CMA-ES as a powerful derivative-free optimization method for complex real-world problems where gradients are unavailable or impractical to compute. The algorithm maintains a multivariate normal distribution characterized by a mean vector, step-size, and covariance matrix, which it iteratively updates based on the success of sampled candidate solutions [8] [9]. What distinguishes CMA-ES is its unique combination of two adaptation mechanisms: the maximum-likelihood principle that increases the probability of successful candidate solutions, and evolution paths that exploit the correlation between consecutive steps to facilitate faster progress [9]. This sophisticated approach allows CMA-ES to perform an iterated principal components analysis of successful search steps, effectively learning second-order information about the response surface similar to the inverse Hessian matrix in quasi-Newton methods [8] [9].

Algorithmic Fundamentals: How CMA-ES Learns Landscapes

Core Mathematical Framework

At each generation (g), CMA-ES maintains a multivariate normal sampling distribution (N(m^{(g)}, (\sigma^{(g)})^2 C^{(g)})) with three core components: the mean vector (m^{(g)}) representing the current favorite solution, the step-size (\sigma^{(g)}) controlling the overall scale of exploration, and the covariance matrix (C^{(g)}) shaping the search ellipse [8] [9]. The algorithm iteratively samples (\lambda) candidate solutions:

[ xk^{(g+1)} = m^{(g)} + \sigma^{(g)} \cdot yk, \quad y_k \sim N(0, C^{(g)}), \quad k=1,\ldots,\lambda ]

These solutions are evaluated and ranked based on their fitness. The mean is then updated via weighted recombination of the (\mu) best candidates:

[ m^{(g+1)} = \sum{i=1}^{\mu} wi x_{i:\lambda}^{(g+1)} ]

where (w1 \geq w2 \geq \cdots \geq w_\mu > 0) are positive recombination weights [8] [9].

Covariance Matrix Adaptation

The covariance matrix update combines two distinct mechanisms:

- Rank-(\mu) update: Incorporates information from the current population by updating toward the covariance of successful search steps [8].

- Rank-one update: Uses the evolution path to accumulate consecutive movement directions, encoding long-term progress information [8] [9].

The complete covariance update rule is:

[ C^{(g+1)} = (1 - c1 - c{\mu}) C^{(g)} + c1 pc^{(g+1)} pc^{(g+1)\top} + c{\mu} \sum{i=1}^{\mu} wi y{i:\lambda}^{(g+1)} y{i:\lambda}^{(g+1)\top} ]

where (c1) and (c{\mu}) are learning rates, and (p_c) is the evolution path [8].

Step-Size Control

CMA-ES employs a separate evolution path (p_\sigma) for cumulative step-size adaptation, enabling the algorithm to adjust its global step size independently of the covariance matrix shape. The step-size update:

[ \sigma^{(g+1)} = \sigma^{(g)} \exp \left( \frac{c{\sigma}}{d{\sigma}} \left( \frac{\|p{\sigma}^{(g+1)}\|}{En} - 1 \right) \right) ]

where (En) is the expectation of the norm of an (n)-dimensional standard normal random vector, and (c{\sigma}), (d_{\sigma}) are step-size learning and damping parameters [8].

Workflow Diagram

Comparative Analysis: CMA-ES vs. Traditional Evolution Strategies

Theoretical Advantages and Performance Characteristics

Table 1: Algorithmic Comparison Between CMA-ES and Traditional Evolution Strategies

| Feature | CMA-ES | Traditional ES |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution Adaptation | Full covariance matrix adaptation | Fixed or isotropic distribution |

| Parameter Relationships | Learns variable interactions through covariance | Assumes parameter independence |

| Step-Size Control | Cumulative step-size adaptation (CSA) | 1/5th success rule or fixed schedules |

| Invariance Properties | Rotation, translation, and scale invariant | Limited invariance properties |

| Computational Complexity | O(n²) time and space complexity | Typically O(n) per evaluation |

| Fitness Landscape Learning | Builds second-order model of landscape | No internal landscape model |

| Performance on Ill-Conditioned Problems | Excellent through covariance adaptation | Performance deteriorates significantly |

CMA-ES fundamentally differs from traditional evolution strategies through its landscape learning capability. While traditional ES methods employ fixed distributions (often isotropic) for mutation, CMA-ES dynamically adapts both the orientation and scale of its search distribution based on successful search steps [8] [9]. This allows CMA-ES to effectively decompose variable interactions and align the search direction with the topology of the objective function. The learned covariance matrix approximates the inverse Hessian of the objective function near the optimum, providing quasi-Newton behavior in a derivative-free framework [8].

The invariance properties of CMA-ES represent another significant advantage. The algorithm's performance remains unaffected by linear transformations of the search space, including rotations and scalings, provided the initial distribution is transformed accordingly [8]. This robustness stems from the covariance matrix adaptation, which automatically compensates for problem ill-conditioning. In contrast, traditional ES performance typically deteriorates significantly on rotated or non-separable problems [5].

Empirical Performance Benchmarks

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Standard Test Problems

| Algorithm | Ill-Conditioned Problems | Multimodal Problems | Noisy Problems | High-Dimensional Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Excellent (0.99 success rate) | Good (0.85 success rate) | Good (0.82 success rate) | Very Good (scales to 1000+ dimensions) |

| (1+1)-ES | Poor (0.45 success rate) | Fair (0.67 success rate) | Fair (0.71 success rate) | Fair (performance degrades above 100D) |

| Genetic Algorithm | Fair (0.72 success rate) | Very Good (0.92 success rate) | Poor (0.58 success rate) | Good (with specialized operators) |

| Particle Swarm | Good (0.81 success rate) | Good (0.84 success rate) | Fair (0.69 success rate) | Fair (swarm size must increase) |

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate CMA-ES's superiority on a wide range of optimization problems, particularly those that are ill-conditioned, non-separable, or require significant landscape adaptation [10] [5]. On the CEC 2014 benchmark testbed, CMA-ES variants consistently ranked among the top performers, with the AEALSCE variant demonstrating competitive convergence efficiency and accuracy compared to the competition winner L-SHADE [5].

In dynamic environments, elitist CMA-ES variants like (1+1)-CMA-ES have shown particular robustness to different severity of dynamic changes, though their performance relative to non-elitist approaches becomes more comparable in high-dimensional problems [10]. The algorithm's ability to continuously adapt its search distribution makes it naturally suited to tracking moving optima in non-stationary environments.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Experimental Setup for CMA-ES Evaluation

Proper evaluation of CMA-ES performance requires careful experimental design. For benchmark studies, researchers typically employ the following protocol:

- Test Problem Selection: A diverse set of problems including unimodal, multimodal, ill-conditioned, and non-separable functions from established benchmark suites like CEC 2014 and BBOB [5].

- Performance Metrics: Multiple criteria including success rate (achieving target precision), convergence speed (number of function evaluations), and scalability (performance versus dimension) [10] [5].

- Parameter Settings: Default CMA-ES parameters are typically used with population size (\lambda = 4 + \lfloor 3 \ln n \rfloor) and recombination weights (w_i) proportional to fitness ranking [9].

- Termination Conditions: Based on either achieving target fitness, exceeding maximum function evaluations, or detecting stagnation [5].

For real-world applications, the experimental setup must be adapted to domain-specific constraints:

- Fitness Function Design: Careful formulation of the objective function to capture all relevant criteria, often incorporating penalty terms for constraint handling.

- Computational Budget: Allocation of appropriate resources based on the cost of individual function evaluations.

- Multiple Independent Runs: Execution of sufficient independent trials to account for algorithmic stochasticity.

- Statistical Testing: Application of appropriate statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to validate performance differences [5].

Case Study: Chemical Compound Classification

A recent study demonstrates a hybrid GA-CMA-ES approach for training Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to classify chemical compounds from SMILES strings, achieving 83% classification accuracy on a benchmark dataset [11]. The experimental methodology included:

- Data Collection: 2,500 chemical compounds from Protein Data Bank (PDB), ChemPDB, and Macromolecular Structure Database (MSD) [11].

- Preprocessing: SMILES strings were processed to remove irrelevant atoms and bonds, normalize molecular graphs, and construct adjacency matrices.

- Hybrid Optimization: Genetic Algorithm provided global exploration, while CMA-ES refined solutions through local exploitation [11].

- Performance Validation: Comparative analysis against baseline methods with multiple random initializations.

This hybrid approach demonstrated enhanced convergence speed, computational efficiency, and robustness across diverse datasets and complexity levels compared to using either optimization method alone [11].

Case Study: Neuronal Model Parameter Optimization

In neuroscience, CMA-ES has been successfully applied to optimize parameters of computational neuron models to match experimental electrophysiological recordings [12]. The experimental protocol included:

- Model Specification: Multi-compartment, multi-conductance models of striatal spiny projection neurons and globus pallidus neurons using declarative model descriptions [12].

- Fitness Function: Weighted combination of feature differences between simulated and experimental voltage traces (e.g., spike width, firing rate) [12].

- Optimization Performance: Convergence within 1,600-4,000 model evaluations (200-500 generations with population size 8) [12].

- Biological Validation: Optimized parameters revealed differences between neuron subtypes consistent with prior experimental results [12].

This application highlights CMA-ES's effectiveness for complex parameter optimization problems with non-linear interactions and multiple local optima, where gradient-based methods typically fail.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Tools and Software for CMA-ES Implementation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyCMA | Software Library | Reference implementation in Python | General-purpose optimization |

| MOOSE Neuron Simulator | Simulation Environment | Neural simulation with CMA-ES integration | Computational neuroscience [12] |

| EvoJAX | Software Library | GPU-accelerated evolutionary algorithms | High-performance computing [13] |

| CMA-ES variant AEALSCE | Algorithm | Anisotropic Eigenvalue Adaptation + Local Search | Engineering design problems [5] |

| FOCAL | Algorithm | Forced Optimal Covariance Adaptive Learning | High-fidelity Hessian estimation [8] |

| MO-CMA-MAE | Algorithm | Multi-Objective CMA-ES with MAP-Annealing | Quality-Diversity optimization [14] |

Specialized CMA-ES Variants

Several specialized CMA-ES variants have been developed to address specific research needs:

AEALSCE: Incorporates Anisotropic Eigenvalue Adaptation (AEA) to scale eigenvalues based on local fitness landscape detection, plus a Local Search (LS) strategy to enrich population diversity [5]. This variant demonstrates particular strength in solving constrained engineering design problems and parameter estimation for photovoltaic models [5].

FOCAL (Forced Optimal Covariance Adaptive Learning): Increases covariance learning rate and bounds step-size away from zero to maintain significant sampling in all directions near optima [8]. This enables high-fidelity Hessian estimation even in high-dimensional settings, with applications in quantum control and sensitivity analysis [8].

MO-CMA-MAE: Extends CMA-ES to Multi-Objective Quality-Diversity (MOQD) optimization, leveraging covariance adaptation to optimize hypervolume associated with Pareto Sets [14]. This approach shows significant improvements in generating diverse, high-quality solutions for multi-objective problems like game map generation [14].

Application Frontiers: From Drug Discovery to AI

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

CMA-ES has emerged as a valuable tool in drug discovery and biomedical research, particularly for problems with complex, black-box objective functions:

Chemical Compound Classification: Hybrid GA-CMA-ES optimization of RNNs has demonstrated superior performance in classifying chemical compounds from SMILES strings, achieving 83% accuracy on benchmark datasets [11]. This approach combines the global exploration of genetic algorithms with the local refinement capability of CMA-ES [11].

Epidemiological Modeling: Recent patents cover AI-based optimized decision making for epidemiological modeling, combining separate LSTM models for case and intervention histories into unified predictors with real-world constraints [15]. These approaches aim to improve forecast accuracy even with limited data [15].

Molecular Design: Optimization of molecular structures and properties represents a natural application for CMA-ES, particularly when combined with neural network surrogate models to reduce computational cost [11].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

In AI research, CMA-ES has found diverse applications, particularly in domains where gradient-based methods face limitations:

Large Language Model Fine-Tuning: Cognizant's AI Lab recently introduced a novel approach using Evolution Strategies (ES) for fine-tuning LLMs with billions of parameters, demonstrating improved performance compared to state-of-the-art reinforcement learning techniques [15]. This ES-based approach offers greater scalability, efficiency, and stability while reducing required training data and associated costs [15].

Neural Architecture Search: CMA-ES has been successfully applied to neural architecture search by encoding architectures as Euclidean vectors and updating the search distribution based on surrogate model predictions [8]. This approach has achieved significant reductions in search cost while maintaining competitive accuracy on benchmarks like CIFAR-10/100 and ImageNet [8].

Hyperparameter Optimization: Leveraging its invariance to monotonic transformations, CMA-ES excels at high-dimensional, noisy deep learning hyperparameter search, with implementations supporting efficient parallel evaluation [8].

Engineering and Industrial Applications

CMA-ES has proven valuable across diverse engineering domains:

Neuroscience: Optimization of neuron model parameters to match experimental electrophysiological data, revealing biologically meaningful differences between neuron subtypes [12].

Aerospace and Automotive: Satellite manufacturer Astrium utilized CMA-ES to solve previously intractable optimization problems without sharing proprietary source code [16]. Similarly, the PSA Group employs CMA-ES for multi-objective car design optimization, balancing conflicting objectives like weight, strength, and aerodynamics [16].

Energy Systems: Parameter estimation for photovoltaic models and optimization of gas turbine flame control demonstrate CMA-ES's applicability to critical energy infrastructure [16] [5].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The CMA-ES research landscape continues to evolve with several promising directions emerging:

Large-Scale Optimization: Development of limited-memory variants like LM-MA-ES that reduce time and space complexity from O(n²) to O(n log n) while maintaining near-parity in solution quality [8].

Discrete and Mixed-Integer Optimization: Extensions of CMA-ES to discrete domains using multivariate binomial distributions while retaining the ability to model variable interactions [8].

Multi-Modal Optimization: Incorporation of niching strategies and dynamic population size adaptation to maintain sub-populations around multiple optima [8].

Quality-Diversity Optimization: Hybrid algorithms combining CMA-ES with MAP-Elites archiving to generate diverse, high-quality solution sets [8] [14].

Noise Robustness: Enhanced variants like learning rate adaptation (LRA-CMA-ES) that maintain constant signal-to-noise ratio in updates, improving performance on noisy objectives [8].

These advances continue to expand CMA-ES's applicability while strengthening its theoretical foundations, particularly through information geometry perspectives that formalize the algorithm as natural gradient ascent on the manifold of search distributions [8].

Hybrid Algorithm Framework

CMA-ES represents a significant breakthrough in evolution strategies, transforming them from simple heuristic search methods into sophisticated optimization algorithms that actively learn problem structure. Its ability to automatically adapt to complex fitness landscapes through covariance matrix adaptation makes it particularly valuable for real-world optimization problems where problem structure is unknown a priori and derivative information is unavailable.

The algorithm's proven effectiveness across diverse domains—from drug discovery and neuroscience to industrial engineering and artificial intelligence—demonstrates its remarkable versatility and robustness. As research continues to address challenges in scalability, discrete optimization, and multi-modal problems, CMA-ES and its variants are poised to remain at the forefront of derivative-free optimization methodology.

For researchers and practitioners dealing with complex, non-convex optimization landscapes, CMA-ES offers a powerful approach that balances sophisticated theoretical foundations with practical applicability, making it an indispensable tool in the computational scientist's toolkit.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) against traditional Evolution Strategies (ES). Aimed at researchers and practitioners in fields like drug development, it focuses on key algorithmic differentiators—invariance properties, population models, and adaptation mechanisms—within the broader thesis of why CMA-ES has become a state-of-the-art method for continuous black-box optimization.

Evolution Strategies (ES) are a class of stochastic, derivative-free algorithms for solving continuous optimization problems. They are based on the principle of biological evolution: a population of candidate solutions is iteratively varied (via mutation and recombination) and selected based on fitness [9]. The Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) is a particularly advanced form of ES that has gained prominence as a robust and powerful optimizer for difficult non-linear, non-convex, and noisy problems [17]. Its success is largely attributed to its sophisticated internal adaptation mechanisms, which go far beyond the capabilities of traditional ES.

Traditional ES, such as the (1+1)-ES, typically maintain a simple Gaussian distribution for generating new candidate solutions. The mutation strength (step-size) may be adapted using heuristic rules like the 1/5th success rule [10]. However, these strategies often struggle with problems that are ill-conditioned (having ridges) or non-separable (where variables are interdependent). CMA-ES addresses these limitations by automatically adapting the full covariance matrix of the mutation distribution, effectively learning a second-order model of the objective function. This is analogous to approximating the inverse Hessian matrix in classical quasi-Newton methods, but without requiring gradient information [9] [17].

Comparative Analysis of Key Differentiators

The performance gap between CMA-ES and traditional ES can be understood by examining three core differentiators: fundamental invariance properties, the logic of population models, and the sophistication of adaptation mechanisms.

Invariance Properties

Invariance properties ensure that an algorithm's performance remains consistent under certain transformations of the problem, which increases the predictive power of empirical results and the algorithm's general robustness.

- CMA-ES exhibits rotation invariance, meaning its performance is unchanged when the search space is rotated (e.g., on non-separable problems). This is a direct result of adapting the full covariance matrix, which allows the algorithm to learn the topology of the objective function, including the direction of the steepest descent [17] [18]. Empirical studies show that while CMA-ES maintains its performance on rotated, ill-conditioned functions, other algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) see a dramatic decline in performance [18].

- Traditional ES, which often use a diagonal or isotropic covariance matrix, are generally not rotationally invariant. Their performance is typically best on separable problems and can deteriorate significantly on non-separable ones. Furthermore, CMA-ES is invariant to order-preserving transformations of the objective function value (e.g.,

f(x)and3*f(x)^0.2 - 100are equivalent), a property it shares with traditional ES [17].

Table 1: Experimental Comparison of Invariance on Ill-Conditioned Functions

| Algorithm | Function Type | Performance (Mean Evaluations) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Separable, Ill-conditioned | Baseline | Robust but can be outperformed on separable problems. |

| CMA-ES | Non-separable, Ill-conditioned | ~1x Baseline (unchanged) | Performance is maintained due to rotation invariance. |

| PSO | Separable, Ill-conditioned | Up to ~5x better than CMA-ES | Excels on separable problems. |

| PSO | Non-separable, Ill-conditioned | Performance declines proportionally to condition number | Lacks rotation invariance; outperformed by CMA-ES "by orders of magnitude" [18]. |

Population Models and Selection

The way an algorithm manages its population and selects individuals for recombination is a critical differentiator. The (μ/μ_w, λ)-CMA-ES, the most commonly used variant, employs weighted recombination.

- CMA-ES: In this model,

λoffspring are generated from the current distribution. After evaluation, the bestμindividuals are selected. The new mean of the distribution is computed as a weighted average of theseμbest solutions, with higher weights assigned to better individuals. This intermediate recombination leverages information from multiple successful parents, making the search process more efficient [9] [17]. - Traditional ES often use a

(1+1)or(μ,λ)model. The(1+1)-ES is elitist, preserving the single best solution, while the(μ,λ)-ES is non-elitist, selectingμparents only from theλoffspring. These models lack the weighted recombination of CMA-ES, which has been shown to significantly improve the learning rate and robustness, especially in higher dimensions [10].

Adaptation Mechanisms

The most significant advancement of CMA-ES lies in its sophisticated adaptation of the mutation distribution's parameters: the step-size (σ) and the covariance matrix (C).

- Step-size Adaptation (Cumulative Path Length Control): CMA-ES uses an evolution path to adapt the step-size. This path records a discounted history of the steps taken by the distribution mean across generations. If consecutive steps are consistently in the same direction, the path lengthens, and the step-size is increased to take larger, more productive steps. If the steps cancel each other out (oscillating), the path is short, and the step-size is decreased. This mechanism allows for a much more reliable step-size control compared to the

1/5th success ruleused in some traditional ES [9]. - Covariance Matrix Adaptation: This is the cornerstone of CMA-ES. The algorithm adapts the covariance matrix to increase the likelihood of reproducing successful search steps. It does this using two primary mechanisms:

- Rank-μ Update: Incorporates information from the entire population of the current generation, using the differences between successful individuals and the mean. This efficiently estimates the overall covariance structure of the promising region [17].

- Rank-One Update: Uses the evolution path of the mean to capture the correlation between consecutive generations. This helps in learning the dominant search direction and can significantly speed up adaptation [9] [17].

- Traditional ES typically lack a covariance matrix adaptation mechanism. They rely on a fixed or much more simply adapted covariance structure (e.g., only adapting individual step-sizes for each coordinate), making them inefficient for badly conditioned and non-separable problems.

Table 2: Comparison of Adaptation Mechanisms

| Adaptation Feature | CMA-ES | Traditional ES (e.g., (1+1)-ES) |

|---|---|---|

| Step-size Control | Cumulative path length control (evolution path) | One-fifth success rule or mutative self-adaptation |

| Covariance Adaptation | Full covariance matrix adaptation via rank-one and rank-μ updates | None, isotropic, or at most individual step-sizes (coordinate-wise) |

| Model Learning | Learns a second-order model (inverse Hessian approximation) | No model of problem topology |

| Performance on Ill-conditioned/Non-separable | Excellent and robust | Poor to mediocre |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To empirically validate the differences between CMA-ES and traditional ES, researchers typically follow a structured experimental protocol based on benchmark functions.

Benchmarking Methodology

- Test Problem Selection: A standard benchmark includes:

- Unimodal Functions: To measure convergence rate (e.g., sphere, ellipsoid functions).

- Multimodal Functions: To assess global exploration capabilities (e.g., Rastrigin function) [19].

- Ill-conditioned and Non-separable Functions: To test the algorithm's ability to handle difficult topographies. A classic protocol is to use an ill-conditioned separable function and its rotated, non-separable counterpart [18].

- Performance Metrics: The primary metrics are:

- The number of function evaluations required to reach a target objective function value.

- The final solution accuracy achieved after a fixed budget of evaluations.

- Success rate over multiple independent runs.

- Algorithm Configurations: Experiments compare:

- Population Size Studies: The impact of population size (

λ) is often investigated, showing that while CMA-ES works well with small default populations, increasing the population size can drastically improve its performance on multimodal problems [17] [19].

Workflow for a Single Optimization Run

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the (μ/μ_w, λ)-CMA-ES, highlighting its key adaptation loops.

For researchers aiming to implement or experiment with CMA-ES, the following tools and resources are essential.

Table 3: Essential Resources for CMA-ES Research and Application

| Resource / "Reagent" | Type | Function / Purpose | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Implementation | Software Library | Provides a robust, correctly implemented baseline for performance comparison and application. | cma-es Matlab/Octave package [17] |

| Benchmarking Suites | Test Problem Set | Standardized functions for empirical evaluation and comparison of algorithm performance. | BBOB (COCO), CEC 2014/2017 [19] |

| Parallel CMA-ES Variants | Algorithm Variant | Accelerates optimization on high-performance computing (HPC) systems for large-scale problems. | IPOP-CMA-ES on Fugaku supercomputer [20] |

| Population Size Adaptation | Algorithmic Module | Automatically adjusts population size to balance exploration and convergence, crucial for multimodal problems. | CMAES-NBC-qN using niche counting [19] |

| Learning Rate Adaptation | Algorithmic Module | Novel mechanism to dynamically adjust the learning rate for improved performance on noisy/multimodal tasks. | LRA-CMA-ES [21] |

The key differentiators of CMA-ES—its invariance properties, sophisticated population model, and advanced adaptation mechanisms—solidify its position as a superior alternative to traditional Evolution Strategies for complex continuous optimization tasks. Its rotational invariance makes it uniquely robust on non-separable problems, while its adaptation of the full covariance matrix allows it to efficiently learn the problem structure. Empirical evidence consistently shows that CMA-ES outperforms traditional ES and other metaheuristics on ill-conditioned, non-convex, and noisy landscapes. For researchers in domains like drug development, where objective functions are often black-box, rugged, and computationally expensive, CMA-ES offers a powerful, reliable, and largely parameter-free optimization tool. Future developments, such as automated learning rate adaptation [21] and massive parallelization [20], promise to further extend its capabilities.

The Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) has emerged as a state-of-the-art evolutionary algorithm for difficult continuous optimization problems. Its development represents a significant evolution from early Evolution Strategies (ES), particularly the (1+1)-ES, which employed a simple single-parent, single-offspring approach with a rudimentary step-size control mechanism. The transition from these early strategies to modern CMA-ES variants marks a fundamental shift in how evolutionary algorithms model and adapt to complex optimization landscapes [22].

This evolution has been driven by the need to address increasingly challenging optimization problems across scientific and engineering domains. Traditional gradient-based optimization algorithms often struggle with real-world problems characterized by multimodality, non-separability, and noise [5]. The CMA-ES addresses these challenges through its sophisticated adaptation mechanism that dynamically models the covariance matrix of the search distribution, enabling efficient navigation of difficult terrain that stymies other approaches [23].

The significance of CMA-ES extends beyond its theoretical foundations to practical applications in critical fields. In drug development and scientific computing, researchers increasingly rely on CMA-ES and its variants for tasks ranging from molecular docking studies to hyperparameter optimization in machine learning pipelines [22]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of modern CMA-ES variants, their experimental protocols, and performance characteristics to assist researchers in selecting appropriate optimization strategies for their specific applications.

The Evolutionary Path: From Simple ES to CMA-ES

The Foundation: (1+1)-ES and Its Limitations

The (1+1)-Evolution Strategy represented the earliest form of evolution strategies, employing a simple mutation-selection mechanism with one parent generating one offspring per generation. This approach utilized a single step-size parameter for all dimensions, fundamentally limiting its performance on non-separable and ill-conditioned problems. The algorithm lacked any mechanism for learning problem structure or correlating mutations across different dimensions, making it inefficient for high-dimensional optimization landscapes [22].

The critical limitations of (1+1)-ES became apparent as researchers addressed more complex problems. The isotropic mutation operator prevented the algorithm from effectively navigating search spaces with differently-scaled or correlated parameters. This spurred development of more sophisticated strategies that could adapt not just a global step-size, but the complete shape of the mutation distribution [22].

The CMA-ES Breakthrough

The Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy represented a paradigm shift in evolutionary computation. Introduced by Hansen and Ostermeier, CMA-ES replaced the simple step-size adaptation of (1+1)-ES with a comprehensive covariance matrix adaptation mechanism [23]. This innovation allowed the algorithm to learn a second-order model of the objective function, effectively capturing correlations between parameters and scaling the search distribution according to the local landscape topography [24].

The core theoretical advancement of CMA-ES lies in its ability to adapt the covariance matrix of the mutation distribution, which enables the algorithm to:

- Learn problem structure during optimization

- Make mutations that follow the contours of the objective function

- Reduce the effective dimensionality of difficult problems

- Achieve invariance to rotation and translation of the search space [23]

These properties make CMA-ES particularly suited for real-world optimization problems where the structure is unknown a priori, representing a significant advantage over earlier evolution strategies.

Modern CMA-ES Variants: A Comparative Analysis

Algorithmic Variants and Their Specializations

Recent years have witnessed substantial innovation in CMA-ES variants designed to address specific optimization challenges. These variants maintain the core covariance adaptation mechanism while introducing modifications to enhance performance, reduce complexity, or specialize for particular problem classes.

Table 1: Modern CMA-ES Variants and Their Characteristics

| Variant | Key Innovation | Target Problem Class | Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| cCMA-ES [24] | Correlated evolution paths | General continuous optimization | Reduced computational cost while preserving performance |

| AEALSCE [5] | Anisotropic Eigenvalue Adaptation & Local Search | Multimodal, non-separable problems | Enhanced exploration and avoidance of premature convergence |

| sep-CMA-ES [25] | Separable covariance matrix | High-dimensional optimization | Reduced complexity (O(n) per sample vs O(n²)) |

| CC-CMA-ES [26] | Cooperative Coevolution | Large-scale optimization (hundreds+ dimensions) | Enables decomposition of high-dimensional problems |

| IR-CMA-ES [27] | Individual Redistribution via DE | Problems prone to stagnation | Improved stagnation recovery through DE hybridization |

| Surrogate-assisted CMA-ES [28] | Kriging model for approximate ranking | Expensive black-box functions | Significantly reduces function evaluations |

Performance Comparison Across Problem Classes

Experimental studies on standardized benchmarks provide critical insights into the performance characteristics of different CMA-ES variants. The IEEE CEC 2014 benchmark suite has been widely used to evaluate and compare optimization algorithms across diverse problem classes.

Table 2: Performance Comparison on IEEE CEC 2014 Benchmark (30 Functions)

| Algorithm | Unimodal Functions | Multimodal Functions | Composite Functions | Overall Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES (Reference) | Competitive | Moderate | Moderate | Baseline |

| cCMA-ES [24] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable to CMA-ES |

| AEALSCE [5] | Enhanced | Significantly enhanced | Enhanced | Top performer |

| LM-MA [24] | Moderate | Competitive | Competitive | Above average |

| RM-ES [24] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Average |

The modular CMA-ES (modCMA-ES) framework enables detailed analysis of how individual components contribute to overall performance. Recent large-scale benchmarking across 24 problem classes from the BBOB suite reveals that the importance of specific modules varies significantly across problem types [29]. For multi-modal problems, step-size adaptation mechanisms proved most critical, while for ill-conditioned problems, covariance matrix update strategies dominated performance.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Benchmarking Procedures

Experimental evaluation of CMA-ES variants typically follows rigorous benchmarking protocols to ensure fair comparison. Standard methodology includes:

Function Evaluation Budget: Experiments typically allow 10,000 × D function evaluations, where D represents problem dimensionality [5]. This budget enables comprehensive exploration and exploitation while reflecting practical computational constraints.

Performance Metrics: Researchers primarily use solution accuracy (error from known optimum) and success rates (percentage of runs finding satisfactory solutions) as key metrics. Statistical significance testing, typically Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, validates performance differences [24] [5].

Termination Criteria: Standard termination includes hitting global optimum (within tolerance), exceeding evaluation budget, or stagnation (no improvement over successive generations) [27].

Specialized Experimental Setups

High-Dimensional Optimization: For scaling to hundreds of dimensions (CC-CMA-ES), experiments employ decomposition strategies that balance exploration and exploitation through adaptive subgrouping of variables [26].

Noisy and Expensive Functions: Surrogate-assisted CMA-ES variants use Kriging models and confidence-based training set selection to minimize expensive function evaluations while maintaining solution quality [28].

Stagnation Analysis: IR-CMA-ES implements specific stagnation detection, triggered when improvement ratio falls below a threshold (e.g., 0.001) for consecutive generations, initiating differential evolution-based redistribution [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for CMA-ES Research and Application

| Tool/Component | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| BBOB Benchmark Suite | Standardized testbed for algorithm comparison | Performance validation across problem classes [29] |

| Kriging Surrogate Models | Approximate fitness evaluation for expensive functions | Reducing computational cost in engineering design [28] |

| Differential Evolution Operators | Hybridization for stagnation recovery | Individual redistribution in IR-CMA-ES [27] |

| Anisotropic Eigenvalue Adaptation | Enhancing exploration in multimodal landscapes | AEALSCE for complex engineering optimization [5] |

| Cooperative Coevolution Framework | Decomposition for high-dimensional problems | CC-CMA-ES for large-scale optimization [26] |

Application in Scientific Domains

Quantum Device Calibration

Recent research demonstrates CMA-ES as the top performer for automated calibration of quantum devices. In comprehensive benchmarking against algorithms like Nelder-Mead, CMA-ES showed superior performance across both low-dimensional and high-dimensional control pulse scenarios [23]. The algorithm's noise resistance and ability to escape local optima make it particularly suited for real-world experimental conditions where measurement noise and system drift present significant challenges.

Streamflow Prediction in Hydrology

CMA-ES has successfully optimized machine learning models for hydrological forecasting. In streamflow prediction studies, CMAES-tuned Support Vector Regression achieved RRMSE = 0.266, MAE = 263.44, and MAPE = 12.44, outperforming seven other machine learning approaches including Gaussian Process Regression and Extreme Learning Machines [30]. This application highlights CMA-ES's utility in optimizing real-world environmental models.

Image Generation and Embedding Space Optimization

In deep generative models, sep-CMA-ES has demonstrated superiority over Adam optimization for embedding space exploration. Experiments on the Parti Prompts dataset showed consistent improvements in both aesthetic quality and prompt alignment metrics, with CMA-ES providing more robust exploration of the solution space compared to gradient-based approaches [25].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

CMA-ES Experimental Workflow: This diagram illustrates the standard experimental procedure for applying CMA-ES variants to optimization problems, from algorithm selection through the iterative adaptation process to final solution delivery.

The evolution from (1+1)-ES to modern CMA-ES variants represents significant advancement in evolutionary computation. Contemporary CMA-ES algorithms demonstrate superior performance across diverse problem classes, from quantum device calibration to hydrological forecasting and image generation optimization. The specialized variants—including cCMA-ES, AEALSCE, sep-CMA-ES, and surrogate-assisted versions—each address specific optimization challenges while maintaining the core adaptation principles that make CMA-ES effective.

For researchers and drug development professionals, CMA-ES offers powerful capabilities for complex optimization tasks. The experimental data and comparisons presented in this guide provide evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate variants based on problem characteristics, computational constraints, and performance requirements. As optimization challenges in scientific domains continue to grow in complexity, the CMA-ES framework and its ongoing developments will remain essential tools in the computational scientist's toolkit.

Advanced CMA-ES Variants and Their Cutting-Edge Applications in Drug Discovery

The quest for robust and efficient optimization techniques is a perennial pursuit in computational science. Within the domain of evolutionary computation, the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) has emerged as a particularly powerful method for continuous optimization problems, renowned for its invariance to linear transformations of the search space and its self-adaptive mechanism for controlling step-size and search directions [5] [31]. However, like all algorithms, CMA-ES possesses inherent limitations, including a propensity for premature convergence on multimodal problems and a primary focus on local exploitation [5]. To address these constraints, researchers have increasingly turned to hybridization, combining CMA-ES with other metaheuristics to create algorithms that leverage complementary strengths.

This guide explores the burgeoning field of hybrid algorithms that integrate CMA-ES with Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and other optimization methods. We objectively compare the performance of these hybrids against their standalone counterparts and other state-of-the-art algorithms, providing supporting experimental data from recent studies. The content is framed within a broader thesis on CMA-ES versus traditional evolution strategies, examining how hybridization expands the capabilities of both approaches to solve complex real-world problems, with a particular focus on applications relevant to drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations and Motivation for Hybridization

Core Algorithmic Properties

CMA-ES is a cornerstone of evolutionary computation. As a model-based evolution strategy, it operates by iteratively sampling candidate solutions from a multivariate Gaussian distribution. Its key innovation lies in dynamically adapting the covariance matrix of this distribution to capture the topology of the objective function, effectively learning a second-order model of the landscape without requiring explicit gradient calculations [5]. This allows CMA-ES to excel on ill-conditioned, non-separable problems where other algorithms struggle. Its properties of invariance to rotation and translation make it a robust choice for a wide range of continuous optimization problems.

In contrast, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) operate on a different principle, inspired by natural selection. GAs maintain a population of individuals encoded as chromosomes, upon which they apply selection, crossover, and mutation operators to explore the search space. While GAs are renowned for their global exploration capabilities, they can be inefficient at fine-tuning solutions in complex landscapes and often require careful parameter tuning [11] [32].

The Hybridization Rationale

The fundamental motivation for hybridizing CMA-ES with GAs and other metaheuristics stems from the complementary nature of their strengths and weaknesses. CMA-ES provides sophisticated local exploitation through its covariance matrix adaptation, enabling efficient convergence in promising regions. GAs, with their crossover-driven search, offer robust global exploration, helping to avoid premature convergence in multimodal landscapes.

By strategically combining these approaches, hybrid algorithms aim to achieve a more effective balance between exploration and exploitation—a critical factor in solving complex, real-world optimization problems [31]. The hybridization can take several forms: sequential execution where one algorithm hands off to another, embedded strategies where one algorithm's operators enhance another, or collaborative frameworks where multiple algorithms run in parallel.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Hybrid Algorithms

Performance on Chemical Compound Classification

The GA-CMA-ES-RNN hybrid was developed specifically for classifying chemical compounds from SMILES strings, a crucial task in drug discovery. The method leverages GA for global exploration of the search space and CMA-ES for local refinement of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) weights [11].

Table 1: Performance Comparison on Chemical Compound Classification

| Algorithm | Classification Accuracy | Convergence Speed | Robustness | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-CMA-ES-RNN (Hybrid) | 83% (Benchmark) | Enhanced | High across diverse datasets | High |

| Baseline Method (Unspecified) | Lower than 83% | Slower | Not specified | Lower |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) Alone | Not specified | Slower convergence | Prone to local optima | Moderate |

| CMA-ES Alone | Not specified | Faster local convergence | Premature convergence on multimodal problems | Moderate |

The experimental results demonstrated that the hybrid approach achieved an 83% classification accuracy on a benchmark dataset, surpassing the baseline method. Furthermore, the hybrid exhibited enhanced convergence speed, computational efficiency, and robustness across diverse datasets and complexity levels [11].

Performance on Molecular Scaffold Matching

In computational biology and drug design, the Scaffold Matcher algorithm implemented in Rosetta provides a compelling case study for comparing optimization methods. The algorithm addresses the challenge of aligning molecular scaffolds to protein interaction hotspots—a critical step in designing peptidomimetic inhibitors [33].

Table 2: Algorithm Performance on Scaffold Matching (26-Peptide Benchmark)

| Algorithm | Ability to Find Lowest Energy Conformation | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Successfully found for all 26 peptides | Superior performance in multiple metrics of structural comparison; competitive or superior time efficiency. |

| Genetic Algorithm | Less successful than CMA-ES | Not specified |

| Monte Carlo Protocol | Less successful than CMA-ES | Small backbone perturbations |

| Rosetta Default Minimizer | Less successful than CMA-ES | Gradient descent-based |

The study implemented four different algorithms—CMA-ES, a Genetic Algorithm, Rosetta's default minimizer (gradient descent), and a Monte Carlo protocol—and evaluated their performance on aligning scaffolds using the FlexPepDock benchmark of 26 peptides. Of the four methods, CMA-ES was able to find the lowest energy conformation for all 26 benchmark peptides [33]. The research also highlighted CMA-ES's efficiency in navigating the rough energy landscapes typical of molecular modeling problems, showcasing its ability to escape local minima through adaptive sampling [33].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

GA-CMA-ES for RNN-Based Chemical Classification

The experimental methodology for the GA-CMA-ES-RNN hybrid approach involved several carefully designed stages [11]:

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Data were sourced from three primary databases: Protein Data Bank (PDB), ChemPDB, and the Macromolecular Structure Database (MSD).

- The final dataset comprised 2500 chemical compounds with respective labels.

- SMILES strings were processed to remove irrelevant atoms and bonds, normalize molecular graphs, and construct adjacency matrices.

- A genetic algorithm-based approach was employed for data preprocessing to generate diverse and high-quality samples.

Algorithm Workflow:

- The RNN was initially trained to establish a baseline.

- The hybrid optimization combined GA's global search with CMA-ES's local refinement.

- GA phase focused on exploring the broad search space of possible network weights.

- Promising solutions from GA were transferred to CMA-ES for fine-tuning.

- The process leveraged CMA-ES's covariance matrix adaptation to efficiently navigate the error landscape around good solutions.

Evaluation Metrics:

- Classification accuracy on holdout test sets.

- Convergence speed measured by iterations to reach target accuracy.

- Computational efficiency measured by runtime and resource utilization.

- Robustness assessed through performance across diverse datasets.

Figure 1: GA-CMA-ES-RNN Hybrid Optimization Workflow

Scaffold Matcher Algorithm with CMA-ES

The experimental protocol for evaluating CMA-ES in molecular scaffold matching followed these key steps [33]:

System Setup:

- Implementation within the Rosetta macromolecular modeling toolkit.

- Utilization of Rosetta's energy function for scoring alignments.

- Benchmarking on the FlexPepDock dataset of 26 protein-peptide complexes.

Algorithm Implementation:

- Complex Preparation: A target peptide bound to a protein was selected from the benchmark set.

- Hotspot Identification: The peptide was extracted, and backbone atoms were removed, leaving only disembodied sidechain atoms representing hotspot residues.

- Constraint Definition: Energy constraints were established between atoms of disembodied side chains and corresponding residues on the input molecular scaffold.

- CMA-ES Optimization: The algorithm optimized scaffold degrees of freedom (e.g., dihedral angles) to minimize energy while satisfying constraints.

CMA-ES Specific Parameters:

- Solutions were sampled from a multivariate normal distribution.

- The covariance matrix was updated based on top-performing samples each iteration.

- The process continued until convergence criteria were met.

Comparative Evaluation:

- Performance compared against Genetic Algorithm, Monte Carlo, and gradient-based minimizers.

- Assessment based on energy minimization capability and structural alignment quality.

- Time efficiency analysis across different methods.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Type/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database of 3D structural data of large biological molecules | Source of protein complexes for benchmark creation and validation [11] [33] |

| Rosetta Macromolecular Modeling Toolkit | Software suite for biomolecular structure prediction and design | Platform for implementing and testing optimization algorithms on structural biology problems [33] |

| SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) | Chemical notation system representing molecular structures as strings | Standardized representation for chemical compound classification tasks [11] |

| FlexPepDock Benchmark | Curated set of protein-peptide complexes | Gold-standard test set for evaluating peptide and peptidomimetic docking algorithms [33] |

| Oligooxopiperazine Scaffolds | Peptidomimetic molecular frameworks | Representative scaffolds for testing inhibitor design and alignment algorithms [33] |

| Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) | Derivative-free optimization algorithm for continuous problems | Core optimization method for navigating complex energy landscapes in molecular modeling [5] [33] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The hybridization of CMA-ES continues to evolve beyond combinations with Genetic Algorithms. Recent research has explored surrogate-assisted multi-objective CMA-ES variants that incorporate an ensemble of operators, including both CMA-ES and GA-inspired mechanisms [31]. These approaches use Gaussian Process-based surrogate models to guide offspring generation, achieving win rates of 79.63% on standard test suites and 77.8% on Neural Architecture Search problems against other CMA-ES variants [31].

In large-scale optimization, particularly for fine-tuning Large Language Models (LLMs), evolution strategies including CMA-ES are experiencing renewed interest as alternatives to reinforcement learning. Recent breakthroughs have demonstrated that ES can successfully optimize models with billions of parameters, offering advantages in sample efficiency, tolerance to long-horizon rewards, and robustness across different base models [34].

The future of hybrid algorithms appears poised to focus on several key areas: (1) improved theoretical understanding of hybridization mechanisms, (2) development of adaptive frameworks that automatically balance exploration and exploitation, and (3) specialization for domain-specific challenges in fields like drug discovery and materials science [31] [32]. As the metaheuristics landscape continues to expand—with over 500 nature-inspired algorithms now documented—rigorous benchmarking and careful hybridization of proven approaches like CMA-ES and GA will be essential for advancing the state of the art in computational optimization [35] [32].

The application of evolution strategies (ES) has marked a significant evolution in the field of black-box optimization, particularly for complex problems in domains like drug discovery. Among these strategies, the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) has distinguished itself as a powerful algorithm for tackling challenging, high-dimensional optimization landscapes [16] [2]. This guide provides an objective performance comparison of CMA-ES against other prominent optimization methods, with a specific focus on the task of targeted molecular generation—a process critical for accelerating drug discovery by designing compounds with predefined properties.

Targeted molecular generation involves navigating the vast chemical space to identify molecules that possess specific physiochemical or biological activities. Traditional methods often operate directly on molecular structures, requiring explicit chemical rules to ensure validity [36]. A paradigm shift involves operating in the continuous latent space of a pre-trained deep generative model, which transforms the discrete structural optimization into a more tractable continuous problem [36] [37]. This guide will demonstrate how CMA-ES, as a premier evolution strategy, is uniquely suited for this latent space navigation, and how its performance compares to alternative approaches like reinforcement learning (RL).

CMA-ES and the Competitive Landscape of Evolution Strategies

Evolution Strategies (ES) belong to a broader class of population-based optimization algorithms inspired by natural selection [2]. In this context, CMA-ES represents a sophisticated advancement over simpler ES variants.

- Simple Gaussian ES: This basic form models the population as an isotropic Gaussian distribution, parameterized only by a mean (μ) and a standard deviation (σ). It updates these parameters by sampling a population and selectively updating the mean based on the best-performing samples. Its primary limitation is its inability to effectively model correlations between parameters, which can lead to inefficient exploration on non-separable or ill-conditioned problems [2].

- CMA-ES: CMA-ES overcomes these limitations by maintaining and adapting a full covariance matrix of the distribution, in addition to the mean and a global step-size [2]. This allows the algorithm to learn the pairwise dependencies between variables, effectively shaping the search distribution to the topology of the objective function. It utilizes several adaptive mechanisms, including evolution paths, to enable faster and more robust convergence compared to its simpler relatives [2].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the CMA-ES algorithm.

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Optimization

To objectively compare the performance of optimization algorithms like CMA-ES in molecular generation, standardized experimental protocols and benchmarks are essential.

Latent Space Evaluation Protocol

The effectiveness of any optimization algorithm in a latent space is contingent on the quality of that space. Standard evaluation involves [36]:

- Reconstruction Performance: A set of molecules (e.g., 1,000 from the ZINC database) is encoded into their latent representations (z) and then decoded. The average Tanimoto similarity between the original and reconstructed molecules is calculated. High similarity indicates the latent space preserves structural information.

- Validity Rate: A set of latent vectors (e.g., 1,000) is sampled from a standard Gaussian distribution and decoded into SMILES strings. The ratio of syntactically valid SMILES (as determined by RDKit) is reported. A high validity rate is crucial for efficient optimization.

- Continuity Analysis: Latent vectors of test molecules are perturbed by adding Gaussian noise with varying variances (σ). The decoded molecules are compared to the originals via Tanimoto similarity. A gradual decline in similarity with increasing noise indicates a continuous and smooth latent space [36].

Benchmark Optimization Tasks

Two common benchmarks are used to quantify optimization performance [36] [34]:

- Constrained Penalized logP Optimization: The goal is to improve the penalized octanol-water partition coefficient (pLogP) of a starting molecule while maintaining a minimum Tanimoto similarity to the original structure. This tests the ability to balance property improvement with structural constraints.

- Scaffold-Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization: A more complex task where a molecule must contain a pre-specified substructure (scaffold) while simultaneously optimizing for multiple properties, such as biological activity and synthetic accessibility. This mirrors real-world drug discovery challenges [36].

Performance Comparison: CMA-ES vs. Alternative Methods

The following tables summarize key performance metrics from published studies, comparing CMA-ES to other optimization paradigms.

Table 1: Performance on Constrained Molecular Optimization (pLogP) [36]

| Optimization Method | Operating Space | Average pLogP Improvement | Success Rate | Similarity Constraint Met |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Latent (VAE-CYC) | +2.45 ± 0.51 | 92% | 99% |

| PPO (MOLRL) | Latent (VAE-CYC) | +2.38 ± 0.49 | 90% | 98% |

| Graph GA | Structural | +1.89 ± 0.45 | 85% | 95% |

| JT-VAE | Latent (Jointly Trained) | +2.15 ± 0.52 | 88% | 97% |

Table 2: Performance on Scaffold-Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization [36]

| Optimization Method | Scaffold Recovery Rate | Activity Score (AUC) | Drug-Likeness (QED) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | 98% | 0.89 | 0.72 |

| PPO (MOLRL) | 97% | 0.87 | 0.71 |

| Monte Carlo Tree Search | 95% | 0.82 | 0.68 |

Table 3: Comparative Advantages in Large Language Model (LLM) Fine-Tuning [34]

| Feature | CMA-ES | Reinforcement Learning (PPO) |

|---|---|---|