Cis-Regulatory Mutations and GRN Evolution: From Evolutionary Mechanisms to Precision Medicine

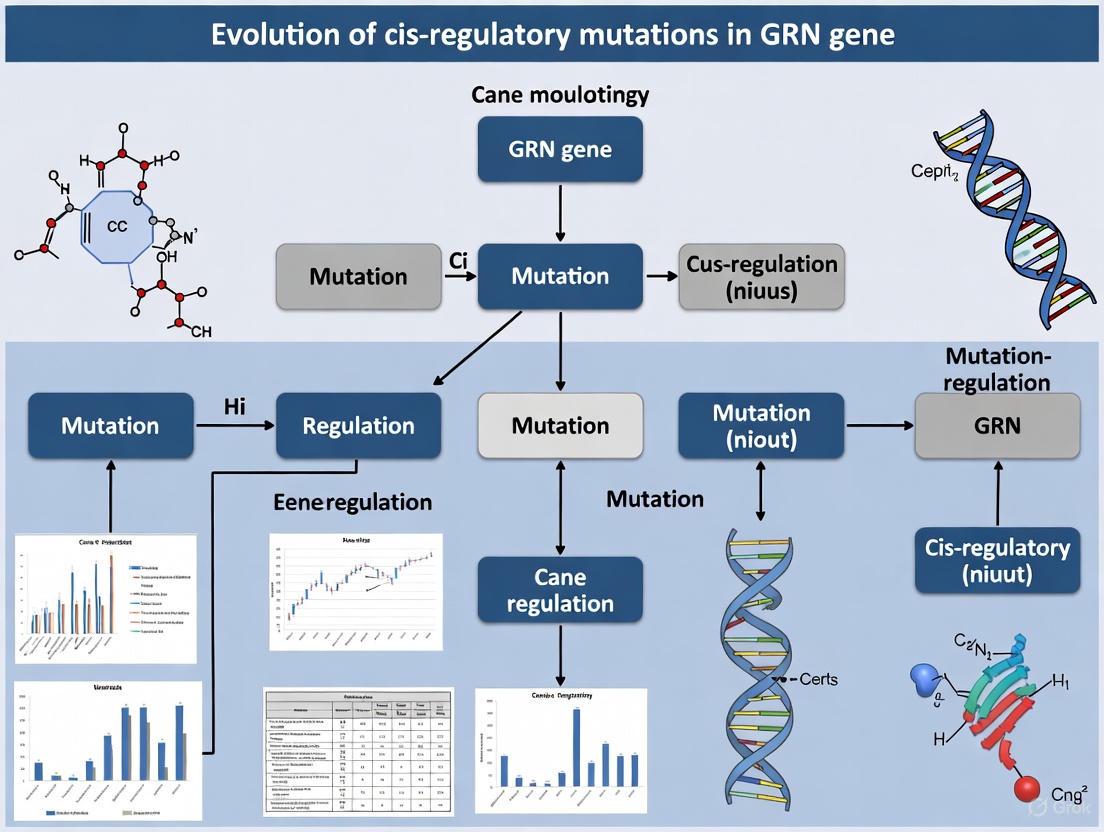

This comprehensive review explores how cis-regulatory mutations drive the evolution of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs), with profound implications for developmental biology, evolutionary processes, and human disease.

Cis-Regulatory Mutations and GRN Evolution: From Evolutionary Mechanisms to Precision Medicine

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores how cis-regulatory mutations drive the evolution of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs), with profound implications for developmental biology, evolutionary processes, and human disease. We examine the fundamental mechanisms by which non-coding DNA alterations rewire transcriptional programs, covering evolutionary conservation patterns, innovative computational methodologies for mutation identification, and current challenges in functional validation. By integrating perspectives from evolutionary developmental biology, cancer genomics, and regulatory genomics, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for understanding how cis-regulatory variation shapes phenotypic diversity and disease pathogenesis, highlighting emerging opportunities for therapeutic intervention through regulatory network manipulation.

The Architectural Blueprint: How Cis-Regulatory Mutations Reshape Gene Regulatory Networks

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) are fundamental blueprints for understanding how genes are expressed spatiotemporally to direct development, physiological homeostasis, and evolutionary processes. At their core, GRNs consist of transcription factors (TFs) and cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) that form precise regulatory linkages governing transcriptional outputs [1] [2]. TFs receive input information from upstream signaling cascades and bind directly or indirectly to target sequences within CRMs, which include enhancers, silencers, promoters, and insulators [3] [2]. These elements work in concert to stimulate or repress the assembly of pre-initiation complexes on gene promoters, thereby precisely controlling RNA polymerase activity [2]. The functional linkages between regulatory genes and their genomic target sites constitute the network architecture that coordinates complex biological processes, from cell differentiation to organism-level responses [2]. Disruptions in these networks, particularly through cis-regulatory mutations, can lead to significant developmental defects and disease states, making their understanding crucial for both basic biology and therapeutic development [4] [5].

Core Components of the GRN Framework

Transcription Factors: The Trans-Acting Regulators

Transcription factors are proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences to regulate the transcription of genetic information from DNA to mRNA. They serve as the primary trans-acting regulators within GRNs, receiving inputs from signaling pathways and transmitting these signals to the transcriptional machinery [2]. Each TF recognizes a degenerate recognition sequence typically 6-20 base pairs long, represented mathematically as a position weight matrix (PWM) [1]. The binding specificity and combinatorial nature of TFs allow for immense regulatory complexity, with multiple TFs often cooperating within a single CRM to fine-tune gene expression patterns in response to developmental and environmental cues [1] [6].

Cis-Regulatory Modules: The Integration Platforms

Cis-regulatory modules are clusters of transcription factor binding sites that function as regulatory integration platforms to process transcriptional inputs [3] [1]. These modules typically range from hundreds to thousands of base pairs in length and can be located upstream, downstream, within introns, or even exons relative to their target genes [1]. CRMs are classified by their functional roles:

- Enhancers facilitate the recruitment of RNA polymerase to promoters, resulting in upregulation of gene transcription [3]

- Silencers repress transcription by inhibiting the recruitment of transcriptional machinery [3]

- Promoters are situated at transcription start sites and bind RNA polymerase and core transcription factors [1]

- Insulators establish boundaries between topological domains, preventing cross-regulation between adjacent CRMs [3]

Notably, some CRMs exhibit dual functionality, acting as both enhancers and silencers in different cellular contexts, with these dual-functional CRMs tending to regulate more distant genes than exclusive enhancers or silencers [3].

Network Hierarchy: The Logic of Gene Regulation

The hierarchical organization of GRNs creates a regulatory logic that governs developmental processes and cellular responses. At the highest level, pioneer transcription factors establish broad regulatory domains that are subsequently refined by downstream TFs operating within more restricted contexts [5]. This hierarchy is evident in the Ciona notochord GRN, where the evolutionarily conserved TFs Brachyury and Foxa2 coordinate the deployment of other notochord transcription factors through specific regulatory connections [5]. The network architecture often contains recurring motifs, such as feed-forward loops (FFLs), where a master regulator controls both a target gene and another regulator that also controls the target, creating precise temporal control and noise-filtering capabilities [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Properties of CRMs and TFBSs in Mouse Genome

| Genomic Element | Count | Genome Coverage | Average Length | Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRM Candidates | 912,197 | 55.5% of mappable genome | ~2,400 bp (enhancers) | Under strong evolutionary constraints |

| TF Binding Site Islands | 38,554,729 | 24.4% of mappable genome | Varies (6-20 bp core) | Cluster within CRMs |

| Experimentally Supported cCREs | 339,815 | 3.4% of genome | 272 bp (fragments) | Likely partial CRM fragments |

Methodologies for Delineating GRN Architecture

Mapping Cis-Regulatory Modules and Their Targets

Accurately mapping CRMs and their target genes remains challenging due to the fact that CRMs often do not regulate their closest genes and can be located hundreds of kilobases away from their targets [3] [4]. The CAPP (Correlation and Physical Proximity) method represents a significant advancement by leveraging predicted CRMs with chromatin accessibility (CA) and RNA-seq data across multiple cell/tissue types, supplemented by Hi-C data [3]. When applied to 107 human cell/tissue types, CAPP predicted target genes for 14.3% of 1.2 million CRMs, with 98.2% as exclusive enhancers, 0.4% as exclusive silencers, and 1.4% as dual-functional CRMs [3].

Experimental Protocol: CAPP Method for CRM-Target Gene Prediction

- Input Data Requirements: Collect chromatin accessibility data (ATAC-seq or DNase-seq) and RNA-seq data from a panel of 107+ cell/tissue types; include Hi-C data from a few cell types for spatial conformation

- CRM Pre-processing: Utilize a pre-computed map of 1.2 million CRMs predicted from TF ChIP-seq data integration

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate correlations between CRM accessibility signals and gene expression levels across the cell/tissue panel

- Physical Proximity Integration: Integrate Hi-C chromatin interaction data to identify spatial proximities between CRMs and candidate genes

- Target Gene Assignment: Assign target genes based on both correlation strength and physical interaction evidence

- Functional Classification: Classify CRMs as enhancers, silencers, or dual-functional based on the directionality of expression correlation

High-resolution chromatin conformation capture methods like Micro-C have revolutionized the mapping of enhancer-promoter interactions by providing unprecedented resolution of chromatin architecture [4]. Micro-C uses micrococcal nuclease (MNase) to fragment chromatin into mononucleosomal fragments (100-200 bp) in a motif-independent manner, generating more consistent fragment sizes and improved genome-wide coverage compared to conventional Hi-C [4].

Deep Learning Approaches for cis-Regulatory Code Interpretation

Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated remarkable capability in deciphering the cis-regulatory code from DNA sequence alone [7]. These models can predict gene expression levels from gene flanking regions with over 80% accuracy across multiple plant species, enabling identification of both conserved and species-specific regulatory sequence features [7]. The model architecture typically consists of three convolutional blocks, each composed of two convolutional layers, that efficiently capture sequence features of different scales and complexity within flanking sequences [7].

Experimental Protocol: CNN Model for Expression Prediction

- Sequence Extraction: For each gene, extract 1000 bp promoter and 500 bp 5'UTR upstream, and 500 bp 3'UTR and 1000 bp terminator downstream regions

- Data Encoding: One-hot encode DNA sequences to serve as input to the CNN model

- Expression Classification: Classify gene expression levels as low, medium, or high based on quartiles of log-transformed TPM values

- Model Training: Train CNN using chromosomal cross-validation, omitting homologous genes from validation sets to prevent bias

- Feature Interpretation: Use predictive feature selection to identify important sequence elements, revealing the significant role of UTR regions

In Vivo CRM Validation and Functional Analysis

Functional validation of predicted CRMs remains essential, with in vivo reporter assays providing the gold standard for confirmation [1] [5]. In Ciona, this involves cloning genomic fragments (1-2 kb) upstream of a basal promoter driving LacZ, electroporating the constructs into zygotes, and scoring expression patterns in developing embryos [5]. Putative CRMs are systematically reduced to minimal elements (100-560 bp) and subjected to site-directed mutagenesis of predicted TF binding sites to identify necessary sequences [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for GRN Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| TF ChIP-seq Datasets (9,060 mouse datasets) | Mapping protein-DNA interactions genome-wide | Predicting CRMs and TFBSs; covers 79.9% of mappable genome [6] |

| Micro-C / Hi-C Libraries | Mapping 3D chromatin architecture | Identifying enhancer-promoter interactions; TAD boundaries [4] [8] |

| dePCRM2 Algorithm | Predicting CRM loci from TF ChIP-seq data | Identified 912,197 putative CRMs in mouse genome [6] |

| CAPP Algorithm | Predicting CRM target genes and functional types | Leverages CA, RNA-seq, and Hi-C data across cell types [3] |

| CNN Expression Models | Predicting expression from sequence features | Cross-species regulatory code analysis; 80%+ accuracy [7] |

| LacZ Reporter Vectors | In vivo CRM validation | Testing minimal CRMs in electroporated embryos [5] |

Chromatin Architecture and 3D Genome Organization

The three-dimensional organization of chromatin plays a fundamental role in GRN function by facilitating spatial proximity between regulatory elements and their target genes [4]. Eukaryotic genomes are hierarchically compacted from nucleosomes to chromosome territories, with long-range chromatin interactions mediated by multi-protein complexes enabling communication between distant genomic elements [4]. These interactions occur within topologically associating domains (TADs), which bring enhancers into close proximity with their target promoters for efficient and precise gene control [4]. Disruptions to these chromatin interactions can misregulate gene expression, contributing to developmental defects and sensory disorders, including hereditary hearing loss [4].

Advanced methods for comparing chromatin contact maps enable quantitative assessment of how 3D genome organization changes across biological conditions [8]. Evaluation of 25 comparison methods revealed that global methods like Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Spearman Correlation are suitable for initial screening, while biologically informed methods (Eigenvector, Contact Directionality, Distance Enrichment) are necessary for identifying specific structural differences and generating functional hypotheses [8].

Evolutionary Dynamics and cis-Regulatory Mutations in GRNs

Cis-regulatory mutations represent a fundamental mechanism driving evolutionary change and phenotypic diversity across species [9]. In plant domestication, genetic variants within CREs have been instrumental in the transition from wild to cultivated species, affecting traits such as fruit size, architecture, and timing of development [9]. These variants can arise through de novo evolution or mutations in ancestral elements, with CRE evolution contributing significantly to domestication syndrome - the suite of traits that differentiate domesticated species from their wild ancestors [9].

The Ciona notochord GRN reveals deeply conserved regulatory circuitry, particularly the cross-regulatory circuit between Brachyury and Foxa2 that lies at the core of notochord formation across chordates [5]. This conservation enables detailed studies of how cis-regulatory changes impact network function and morphological evolution. Deep learning approaches further enable systematic investigation of sequence-to-regulation relationships across multiple species, identifying both conserved and species-specific regulatory features [7]. For example, CNN models trained on multiple plant species effectively identified regulatory sequences predictive of gene expression and revealed causal links between genetic variation and expression changes across fourteen tomato genomes [7].

Understanding the intricate framework of GRNs - comprising transcription factors, cis-regulatory modules, and their hierarchical organization - provides crucial insights into normal development, disease mechanisms, and evolutionary processes. The experimental and computational methodologies outlined here enable researchers to systematically map regulatory networks, identify functional elements, and understand how perturbations contribute to disease. For drug development professionals, this knowledge offers new avenues for therapeutic intervention, particularly through targeting specific regulatory nodes or correcting dysregulated network activity. As technologies for profiling and manipulating regulatory elements continue to advance, so too will our ability to precisely engineer GRNs for both basic research and clinical applications.

Modification of gene regulation has long been considered a primary force in evolution, particularly through changes to cis-regulatory elements (CREs) that control transcriptional regulation [10]. The evolution of a body plan is fundamentally a system-level problem governed by changes in developmental Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs), and the alteration of GRN functional organization represents a major mechanism of evolutionary change in animal morphology [11]. Since developmental GRN structure determines GRN function, and since derived evolutionary change in animal body plans must occur because of change in the genomic apparatus controlling development, evolution of the body plan must be effected by alterations in the structure of developmental GRNs [11]. The predominant mechanism of evolutionary change in GRN structure is alteration of cis-regulatory modules that determine regulatory gene expression, making the classification and functional understanding of these mutations crucial for evolutionary and biomedical research [11].

Classification of Cis-Regulatory Mutations and Their Functional Consequences

The topology of a GRN is encoded directly in cis-regulatory sequence at its nodes, giving evolutionary changes in this sequence great potency to alter developmental GRN structure and function [11]. Cis-regulatory mutations can be broadly categorized into two fundamental classes: internal changes affecting sequence within cis-regulatory modules, and contextual sequence changes which alter the physical disposition of entire cis-regulatory modules [11].

Table 1: Classification of Cis-Regulatory Mutations and Their Functional Consequences

| Mutation Category | Specific Mutation Type | Primary Functional Consequence | Potential Impact on GRN Topology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Sequence Changes | Appearance of new transcription factor binding site(s) | Quantitative output change; Input gain within GRN; Cooptive redeployment to new GRN | Potentially alters network connectivity by creating new regulatory inputs |

| Loss of existing transcription factor binding site(s) | Loss of function; Quantitative output change; Input loss within GRN | Eliminates existing regulatory connections, potentially simplifying network architecture | |

| Change in binding site number | Quantitative output change | Modifies regulatory strength without necessarily altering connectivity pattern | |

| Change in binding site spacing | Quantitative output change; Possible input gain/loss | May affect cooperative binding and transcriptional output | |

| Change in binding site arrangement | Quantitative output change; Possible input gain/loss | Can alter combinatorial logic of regulatory integration | |

| Contextual Changes | Translocation of module to new genomic position | Cooptive redeployment to new GRN | Potentially creates novel network connections by placing regulatory control under new influences |

| Module deletion | Loss of function | Removes regulatory nodes entirely from the network | |

| Acquisition of new tethering function | Input gain/loss within GRN; Cooptive redeployment | Can establish new long-range regulatory relationships | |

| Duplication followed by subfunctionalization | Quantitative output change; Cooptive redeployment | Creates redundancy and opportunities for specialized regulatory division |

The functional consequences of these mutations range from complete loss of function (LOF) to subtle quantitative changes in transcriptional output, to qualitative gain of function (GOF) that can result in redeployment of gene expression to new spatial or temporal contexts [11]. Research has demonstrated considerable freedom in cis-regulatory design, with orthologous modules from distantly related species often maintaining identical regulatory function despite extreme differences in transcription factor binding site order, number, and spacing [11]. This suggests that the qualitative identity of regulatory inputs, rather than their precise arrangement, represents the primary constraint on cis-regulatory function in many cases.

Experimental Approaches for Cis-Regulatory Analysis

Advanced Functional Genomics Methods

Modern approaches to cis-regulatory analysis leverage high-throughput functional genomics techniques to systematically identify and characterize regulatory elements. Pooled CRISPR inhibition (CRISPRi) screens have emerged as a powerful method for comprehensively probing cis-regulatory function at nucleotide resolution [12] [13]. This approach involves designing guide RNA (gRNA) libraries that tile across large genomic regions, such as topologically associated domains (TADs), then introducing these libraries into cell populations to measure the effects of regulatory perturbations on phenotypic outcomes like cell growth or transcriptional output [12].

Recent applications of this technology have enabled the identification of functional CREs within a 2.8 Mb TAD containing the MYC oncogene across six human cancer cell lines [12]. This systematic approach mapped 32 CREs where inhibition impacted cell growth, with targeting of specific CREs decreasing MYC expression by up to 60% and cell growth by up to 50% [12]. Importantly, this research demonstrated that while CREs identified through this functional approach almost always contact MYC via 3D chromatin interactions, less than 10% of total MYC contacts actually impact growth when silenced, highlighting the utility of perturbation-based approaches to identify phenotypically relevant CREs among the numerous potential regulatory connections [12].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Cis-Regulatory Analysis

| Research Tool Category | Specific Reagents/Methods | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Perturbation Systems | CRISPR inhibition (CRISPRi) | Targeted repression of regulatory elements | Functional mapping of enhancers and silencers; Identification of essential regulatory regions |

| CRISPR nuclease (CRISPR-Cas9) | Targeted deletion of regulatory elements | Validation of enhancer function through loss-of-function studies | |

| RNA-targeting Cas13 systems | Knockdown of noncoding transcripts | Functional analysis of regulatory RNAs involved in cis-regulation | |

| Genomic Profiling Methods | ATAC-STARR-seq | Simultaneous measurement of chromatin accessibility and enhancer activity | Direct identification of cis- vs trans-acting regulatory divergence |

| ChIPmentation (ChIP-seq) | Mapping histone modifications and transcription factor binding | Epigenetic characterization of regulatory element activity states | |

| Hi-C and chromatin conformation capture | Mapping 3D genome architecture and chromatin interactions | Identification of physical contacts between regulatory elements and target genes | |

| Computational & Analytical Frameworks | Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) | Synteny-based identification of orthologous regulatory regions | Discovery of functionally conserved but sequence-divergent CREs across species |

| Correlation and Physical Proximity (CAPP) | Prediction of CRM target genes and functional types | Integration of chromatin accessibility and expression data to infer regulatory relationships | |

| dePCRM2 algorithm | Genome-wide prediction of cis-regulatory modules | Comprehensive mapping of regulatory elements from TF ChIP-seq data |

Distinguishing Cis and Trans Regulatory Divergence

A critical advancement in regulatory genomics has been the development of methods to distinguish cis-acting from trans-acting regulatory changes. The ATAC-STARR-seq methodology enables simultaneous measurement of chromatin accessibility (primarily influenced by trans-acting factors) and enhancer activity (driven by cis-sequence) in a single assay [14]. Application of this approach to human and rhesus macaque lymphoblastoid cells revealed that approximately 67% of divergent regulatory elements experienced changes in both cis and trans, highlighting the intertwined nature of these regulatory modes in evolution [14]. This research demonstrated that trans divergence contributes substantially to differences between species, with approximately 37% of human trans differences linking to a handful of transcription factors [14].

Regulatory Divergence Pathways

Evolutionary Dynamics of Cis-Regulatory Elements

Conservation Beyond Sequence Alignment

A paradigm-shifting insight from recent evolutionary genomics is that functional conservation of CREs often persists despite extensive sequence divergence. When examining CREs between mouse and chicken embryonic hearts, fewer than 50% of promoters and only approximately 10% of enhancers show significant sequence conservation using traditional alignment-based methods [15]. However, employing synteny-based algorithms like Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) that identify orthologous genomic regions based on relative position rather than sequence similarity reveals a substantially different picture—positionally conserved promoters increase more than threefold (from 18.9% to 65%) and enhancers more than fivefold (from 7.4% to 42%) [15].

This discovery of "indirectly conserved" (IC) regulatory elements demonstrates widespread functional conservation of sequence-divergent CREs across large evolutionary distances [15]. These IC elements exhibit chromatin signatures and sequence composition similar to sequence-conserved CREs but show greater shuffling of transcription factor binding sites between orthologs, suggesting that positional conservation relative to target genes may be more evolutionarily constrained than the precise regulatory sequence itself [15].

Population Genetics of Cis-Regulatory Variation

Analysis of human polymorphism data has revealed distinct evolutionary patterns in cis-regulatory elements. Studies examining 1000 Genomes Project data in various classes of coding and noncoding elements have found that transcription factor binding sites are significantly constrained, though less strongly than coding sequences [10]. Negative selection appears to dominate in these regions, with stronger constraint observed in bound versus unbound TFBSs, in TFBSs proximal to transcription start sites versus distal ones, and in TFBSs with strong rather than weak ChIP-seq signals [10].

The application of McDonald-Kreitman and related tests to regulatory elements has provided evidence for both negative and positive selection acting on CREs in human evolution [10]. Some studies have found that mutations decreasing the matching score of a transcription factor binding motif are enriched for rare alleles compared to ones that do not, consistent with purifying selection, while other approaches have detected contributions from positive selection in several types of regulatory elements, including DNase-I hypersensitive sites and sequence-specific TFBSs [10].

Cis-Regulatory Element Evolutionary Paths

Implications for Gene Regulatory Network Evolution and Disease

Hierarchical Organization and Evolutionary Flexibility

The organization of gene regulatory networks follows a hierarchical structure that profoundly influences evolutionary dynamics [11]. Developmental GRNs are structured as assemblages of subcircuits that control sequential phases of development, from early embryonic patterning to terminal differentiation [11]. This hierarchical organization creates a mosaic of evolutionary constraints and opportunities, with some GRN subcircuits exhibiting great evolutionary antiquity while others demonstrate remarkable flexibility [11].

The peripheral components of GRNs, particularly those controlling terminal differentiation genes, appear more evolutionarily labile than the kernels governing early developmental patterning [11]. This differential flexibility explains major aspects of evolutionary process, including hierarchical phylogeny and discontinuities in paleontological change and stasis [11]. The concentration of evolutionary innovation in specific network regions rather than uniform distribution across the entire GRN provides a framework for understanding how developmental systems can both maintain essential functions while exploring novel morphological solutions.

Cancer as a Model for Cis-Regulatory Dysregulation

Cancer genomes provide compelling models for understanding the functional consequences of cis-regulatory mutations in human disease. Comprehensive dissection of the MYC locus in multiple cancers has revealed how lineage-specific transcription factors influence oncogene regulation through specific CREs [12]. These studies have detected strong, tumor-specific correlations between transcription factor and MYC expression not found in normal tissue, illustrating how the rewiring of regulatory connections contributes to oncogenic states [12].

The discovery that noncoding RNAs can themselves modulate the regulatory impact of DNA cis-regulatory elements adds another layer of complexity to GRN organization [12]. For example, repression of the CCAT1 noncoding transcript not only reduces MYC expression but also decreases looping of the CCAT1 locus with the MYC promoter, demonstrating that RNA molecules can participate in establishing or maintaining the 3D genomic architecture that underlies cis-regulation [12].

The classification of cis-regulatory mutations and their functional consequences provides a foundational framework for understanding evolutionary innovation and disease mechanisms. The diverse categories of cis-regulatory changes—from internal sequence alterations to contextual genomic rearrangements—exert distinct effects on gene regulatory network topology and function. Advanced experimental approaches, including CRISPR-based functional genomics and multi-species comparative analyses, have revealed unexpected complexities in regulatory evolution, including the prevalence of positional conservation despite sequence divergence and the intertwined nature of cis and trans regulatory changes. As these methodologies continue to illuminate the mechanisms of cis-regulatory evolution, they promise to enhance our understanding of both evolutionary biology and human disease pathogenesis.

{#abstract}

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) represent the complex circuits of regulatory interactions that control development and phenotype. Within the broader context of cis-regulatory mutations and GRN evolution research, this whitepaper examines the core principles governing the conservation and innovation of GRN subcircuits across species. Comparative analyses of metazoan species reveal remarkable conservation in global network architecture—including high-occupancy target regions, feed-forward loop motifs, and transcription factor binding specificities—even as individual network connections undergo extensive rewiring. Conversely, evolutionary innovation frequently occurs through accelerated sequence evolution within deeply conserved, pleiotropic enhancer elements, particularly those regulating developmental genes. This dynamic interplay between architectural conservation and regulatory sequence divergence provides a framework for understanding how phenotypic diversity arises from genetic variation and offers new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

{#introduction}

The evolution of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) is fundamentally constrained by the functional architecture of cis-regulatory DNA. These non-coding sequences serve as computational modules that integrate transcriptional inputs to determine spatiotemporal gene expression patterns. The hypothesis that cis-regulatory mutations represent the primary substrate for morphological evolution stems from their capacity to alter specific aspects of gene expression without introducing pleiotropic effects typically associated with protein-coding changes [16]. This modularity enables the accumulation of genetic variation within enhancer elements that control developmental genes, facilitating evolutionary innovation while preserving essential biological functions.

Research spanning mammalian phylogenies has demonstrated that conserved non-coding elements, particularly those with regulatory functions, cluster around developmental transcription factors and signaling pathway components [16]. These deeply conserved sequences exhibit unexpected patterns of accelerated evolution, suggesting that evolutionary innovation frequently occurs not through the creation of entirely new regulatory elements, but through the functional modification of existing, conserved regulatory architecture. This whitepaper synthesizes evidence from cross-species comparative studies, evolutionary simulations, and empirical analyses to elucidate the principles governing conservation and innovation in GRN subcircuits, with particular emphasis on implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

{#conserved-elements}

Conserved Architectural Principles in GRN Organization

Despite extensive evolutionary divergence, metazoan GRNs maintain remarkably conserved organizational principles. Cross-species analyses of 165 human, 93 worm, and 52 fly transcription factors revealed that structural properties of regulatory networks are highly conserved, with orthologous regulatory factor families recognizing similar binding motifs in vivo [17].

High-Occupancy Target (HOT) Regions

A fundamental conserved feature is the organization of regulatory factor binding into high-occupancy target regions, where approximately 50% of binding events cluster in densely occupied cis-regulatory elements across all three species [17]. These HOT regions demonstrate both constitutive and context-specific functions:

- Constitutive HOT regions (5-10% of total) primarily localize to promoter chromatin states and maintain stable regulatory functions across cellular contexts.

- Context-specific HOT regions (90-95% of total) predominantly function as enhancers and display dynamic establishment during development and cellular differentiation, with approximately 80-90% falling within enhancer chromatin states [17].

Network Motif Conservation

The local structure of regulatory networks shows striking conservation in enriched sub-graphs, with the feed-forward loop (FFL) representing the most abundant network motif across human, worm, and fly species [17]. The prevalence of specific motifs varies by developmental stage, with L1 stage in worm and late-embryo stage in fly showing the highest number of FFLs, suggesting conserved mechanisms for filtering fluctuations and accelerating transcriptional responses during critical developmental windows [17].

{#innovation-mechanisms}

Mechanisms of Evolutionary Innovation in Conserved GRNs

Evolutionary innovation within conserved GRN architecture occurs through multiple mechanisms that modify regulatory sequences while preserving core network topology.

Accelerated Evolution in Conserved Enhancers

Comparative genomic analyses across 120 mammalian species have revealed pervasive accelerated sequence evolution within conserved enhancer elements. These acceleration events are particularly enriched in pleiotropic genes involved in gene regulatory and developmental processes [16]. Such genes typically possess an excess number of enhancers compared to other genes, enabling substantial sequence acceleration across their combined regulatory landscape while buffering against detrimental effects on essential functions.

Regulatory Circuit Rewiring

While global network architecture and factor co-associations are conserved, specific regulatory connections show extensive evolutionary turnover. Analysis of orthologous transcription factors in worm and fly revealed minimal significant overlap in target genes, indicating substantial rewiring of regulatory control despite conservation of DNA-binding specificity [17]. This divergence in network connectivity underlies species-specific adaptations while operating within conserved architectural constraints.

Mutation, Drift, and Selection in GRN Evolution

Forward-in-time simulations of GRN evolution (EvoNET) demonstrate that the fitness effects of mutations are not constant but evaluated at the phenotypic level through each individual's distance from an optimal phenotype [18]. This framework reveals three key deviations from classic selective sweep theory in GRN evolution:

- Variation in selection intensity over time as networks approach phenotypic optima.

- Soft sweeps originating from multiple favorable alleles rather than single mutations.

- Overlapping selective events throughout the genome [18].

Natural selection, combined with random genetic drift, modifies gene expression patterns and consequently the properties of GRNs, favoring variants that produce similar phenotypes despite underlying genotypic variation [18].

{#quantitative-data}

Quantitative Analysis of GRN Conservation and Divergence

{#table1}

Table 1. Conservation of Architectural Features Across Metazoan GRNs

| Architectural Feature | Human | C. elegans | D. melanogaster | Conservation Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOT Region Distribution | ~50% of binding in HOT regions | ~50% of binding in HOT regions | ~50% of binding in HOT regions | Quantitative conservation |

| Constitutive HOT Regions | 5-10% | 5-10% | 5-10% | Quantitative conservation |

| Feed-Forward Loop Prevalence | Most abundant motif | Most abundant motif | Most abundant motif | Qualitative conservation |

| Upward-Flowing Edges | 30% | 22% | 7% | Species-specific variation |

| Master Regulators (Top Layer) | 33% | 13% | 7% | Species-specific variation |

| Orthologous TF Motif Conservation | Reference | 12/18 families | 12/18 families | High conservation |

Source: Adapted from cross-species analysis of 310 transcription factors [17]

{#table2}

Table 2. Properties of Accelerated Evolution in Mammalian Enhancers

| Feature | phastCons Elements (pCEs) | ENCODE cCREs | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Elements | 319,292 | 115,014 | N/A |

| Mean phastCons Score | 0.761 | 0.299 | P < 10⁻³⁰⁷ |

| Genome Coverage | 5.7% of non-coding, non-repetitive genome | 5.7% of non-coding, non-repetitive genome | N/A |

| Overlap with pCEs | 100% | 43.8% | P < 0.0001 |

| Acceleration Across Phylogeny | Pervasive | Pervasive | Branch-specific patterns |

| Functional Association | Developmental signaling | Immune function & developmental regulation | Gene set enrichment |

Source: Analysis of 120 mammalian genomes and 434,306 putative regulatory elements [16]

{#experimental-methods}

Experimental Protocols for Comparative GRN Analysis

Cross-Species Regulatory Factor Profiling

The ENCODE and modENCODE consortia established standardized protocols for comparative GRN analysis that enable direct cross-species comparisons [17]:

- Transcription Factor Selection: Orthologous regulatory factor families were identified across human (165 factors), C. elegans (93 factors), and D. melanogaster (52 factors).

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation: All factors were analyzed by ChIP-seq according to consortium standards, with extensive antibody characterization and at least two independent biological replicates.

- Binding Site Identification: A uniform computational pipeline identified reproducible targets using Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) analysis to ensure robust, quality-filtered datasets.

- Motif Conservation Analysis: Sequence-enriched motifs were identified for orthologous families, with conservation assessed through cross-species motif enrichment.

Identification of Accelerated Evolution in Enhancers

Protocol for detecting sequence acceleration in conserved regulatory elements across mammalian phylogeny [16]:

- Element Definition: Collect putative regulatory elements (PREs) comprising phastCons elements (pCEs) and ENCODE candidate cis-regulatory elements (cCREs) with conserved biochemical signatures between human and mouse.

- Sequence Alignment: Map PREs to orthologous sequences across 120 mammalian genomes using whole genome alignment.

- Acceleration Testing: Use phyloP to test for accelerated sequence substitutions on 100 selected internal branches of the mammalian phylogeny, excluding terminal branches to avoid confusion between polymorphic and fixed variants.

- Filtering: Remove PRE sequences with extensive indels (>120% or <80% of human PRE length) and exclude results potentially affected by GC-biased gene conversion.

Evolutionary Simulation of GRNs (EvoNET)

The EvoNET framework implements forward-in-time simulation of GRN evolution, extending Wagner's classical model with enhanced biological realism [18]:

- Population Initialization: Create a population of N haploid individuals, each comprising a set of genes with binary cis and trans regulatory regions of length L.

- Interaction Calculation: Compute interaction matrix Mn×n using the function I(Ri,c, R_j,t) that determines interaction type and strength based on complementarity between cis and trans regulatory regions.

- Phenotypic Evaluation: Subject each individual to a maturation period where GRN may reach equilibrium, then evaluate fitness by measuring phenotypic distance from optimum.

- Generational Turnover: Individuals compete to produce next generation through selection and recombination, with mutations introduced in regulatory regions.

{#visualization}

Visualization of GRN Architecture and Evolution

{#figure1}

Figure 1. Conserved GRN Architecture Across Metazoans

{#figure2}

Figure 2. Mechanisms of Evolutionary Innovation in GRNs

{#research-tools}

Research Reagent Solutions for GRN Evolution Studies

{#table3}

Table 3. Essential Research Reagents for Comparative GRN Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in GRN Research | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq Validated Antibodies | ENCODE/modENCODE characterized antibodies for 310 transcription factors across three species | Specific immunoprecipitation of DNA-bound regulatory factors | Cross-species binding site identification and conservation analysis [17] |

| Whole Genome Alignment Resources | 120-mammal genome alignment; MULTIZ | Identification of orthologous regulatory sequences and constrained elements | Detection of accelerated evolution in conserved non-coding elements [16] |

| Regulatory Element Annotations | phastCons Elements (pCEs); ENCODE cCREs | Curated sets of putative regulatory elements with evolutionary conservation | Definition of element sets for acceleration testing and functional validation [16] |

| Evolutionary Analysis Software | phyloP; phastCons | Detection of sequence acceleration and evolutionary constraint | Quantification of substitution rate variation across phylogenetic trees [16] |

| GRN Simulation Platforms | EvoNET; Wagner-style simulators | Forward-in-time simulation of GRN evolution under selection and drift | Modeling population-level dynamics of regulatory evolution [18] |

| Motif Discovery Tools | MEME; HOMER | Identification of enriched sequence motifs in bound regions | Conservation analysis of transcription factor binding specificities [17] |

{#conclusion}

The evolutionary patterns of GRN subcircuits reveal a fundamental principle: innovation occurs predominantly within conserved architectural frameworks. For biomedical researchers and drug development professionals, this principle has profound implications. The enrichment of accelerated evolution in enhancers regulating developmental signaling pathways suggests these elements as potential targets for therapeutic intervention in diseases with developmental origins. Furthermore, the understanding that pleiotropic genes can evolve through modular enhancer changes without catastrophic consequences provides a framework for developing targeted regulatory therapies.

The conservation of global network architecture across species validates the use of model organisms for studying fundamental regulatory principles, while the extensive rewiring of specific connections highlights the importance of human-specific validation for therapeutic targets. As cis-regulatory mutations increasingly emerge as contributors to disease susceptibility and morphological evolution, the analytical frameworks and experimental approaches outlined in this review provide a roadmap for translating evolutionary insights into biomedical advances.

The quest to understand the genetic basis of morphological diversity has increasingly shifted from protein-coding genes to the non-coding regulatory genome. Cis-regulatory elements (CREs)—non-coding DNA sequences including enhancers, promoters, and silencers—orchestrate complex spatiotemporal expression patterns that guide embryonic development and evolutionary change. These elements form the foundational components of gene regulatory networks (GRNs), which integrate signals from multiple transcription factors to control developmental processes. The evolution of morphological traits is now recognized to occur predominantly through mutations in these regulatory sequences rather than alterations to protein-coding regions themselves [19].

The central thesis of modern evolutionary developmental biology posits that cis-regulatory mutations provide a privileged mechanism for phenotypic evolution because they enable tissue-specific changes without the pervasive pleiotropic effects that often accompany coding mutations. This review synthesizes recent advances in our understanding of how regulatory alterations reshape developmental processes, focusing on the interplay between cis-regulatory evolution, GRN architecture, and the emergence of novel morphological traits. We examine both the theoretical frameworks and experimental methodologies that are illuminating the principles governing regulatory evolution across diverse vertebrate and invertebrate systems.

Theoretical Framework: Cis-Regulatory Evolution and GRN Architecture

The Molecular Logic of Cis-Regulatory Function

Cis-regulatory elements function as computational units that process inputs from multiple transcription factors to determine precise spatial and temporal expression patterns of target genes. Each CRE contains a specific arrangement of transcription factor binding sites that collectively determine its regulatory output. The properties of CREs—including their combinatorial logic, binding site affinity, and chromatin accessibility—create a sophisticated regulatory code that evolves through distinct mechanisms compared to protein-coding sequences [19].

The conventional view of enhancers as autonomous, modular elements controlling discrete expression domains has been challenged by recent findings demonstrating extensive functional interdependence and pleiotropy. Many CREs regulate gene expression in multiple developmental contexts, and deleting a single enhancer can affect seemingly unrelated phenotypes [19]. This complexity necessitates a more nuanced understanding of how regulatory changes propagate through developmental networks to produce phenotypic outcomes.

Evolutionary Dynamics of Regulatory Sequences

The evolution of cis-regulatory elements occurs through several distinct mechanisms with different implications for phenotypic innovation:

- Co-option of existing elements: Preexisting CREs are redeployed to new developmental contexts, often through changes in the transcription factors expressed in different tissues.

- De novo emergence: New regulatory elements arise from previously non-functional sequences, potentially through transposable element exaptation.

- Modification of existing elements: Sequence changes alter the function of established CREs, fine-tuning their expression output or changing their responsiveness to specific transcription factors.

Recent evidence suggests that covertly homologous elements—CREs that perform similar regulatory functions across species but have diverged considerably in sequence—may be more common than previously recognized [19]. This sequence divergence with functional conservation complicates the identification of homologous regulatory elements and suggests that regulatory grammar may be more conserved than nucleotide sequences [20].

Table 1: Mechanisms of Cis-Regulatory Evolution and Their Characteristics

| Mechanism | Sequence Characteristics | Phenotypic Effect | Evolutionary Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-option | Preexisting element with conserved binding sites | Novel expression context, potentially major effect | Rapid, enabled by transcription factor changes |

| De novo emergence | Previously non-functional sequence, often from transposable elements | Truly novel regulatory functions | Variable, constrained by random mutation |

| Modification | Altered transcription factor binding sites or arrangement | Fine-tuning of expression pattern, modest effects | Gradual, dependent on selective constraint |

| Compensatory changes | Multiple sequence changes that preserve function | Phenotypic stability despite sequence divergence | Slow, constrained by functional requirements |

Robustness and Evolvability in Gene Regulatory Networks

GRNs exhibit properties of robustness—the ability to buffer against perturbations—and evolvability—the capacity to generate phenotypic variation. Simulations of evolving GRNs, such as those implemented in the EvoNET framework, demonstrate that populations evolving under stabilizing selection develop increased robustness against deleterious mutations [18]. This robustness arises through redundant regulatory pathways and network architectures that can maintain stable phenotypic outputs despite genetic variation.

The relationship between robustness and evolvability creates a paradox: while robustness buffers against immediate deleterious effects of mutation, it also allows the accumulation of cryptic genetic variation that can be released under changing environmental conditions or genetic backgrounds. This hidden variation provides substrates for evolutionary innovation when networks are perturbed beyond their stable operating parameters [18] [19].

Empirical Evidence: Case Studies in Morphological Evolution

Wnt Gene Cluster Evolution in Silkworm Morphology

A compelling example of cis-regulatory evolution driving morphological divergence comes from comparative studies of silkworm species (Bombyx mori and B. mandarina). These species exhibit differences in larval caudal horn size, a morphological trait that has evolved diversity across Lepidopteran species. Through quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping and interspecific crosses, researchers identified a conserved Wnt-family gene cluster on chromosome 4 as the largest effector of caudal horn size difference, accounting for approximately one-third of the mean horn length divergence [21].

Functional validation using CRISPR/Cas9 knockouts and allele-specific expression analysis demonstrated that tissue-specific cis-regulatory changes to Wnt1 and Wnt6 underlie the species difference in horn development. This case illustrates how modular cis-regulatory changes enable highly pleiotropic developmental regulators like Wnt genes to contribute to the evolution of specific morphological traits without causing widespread deleterious effects [21]. The compartmentalization of gene expression allowed evolutionary change in one tissue (the caudal horn) while preserving essential Wnt signaling functions in other developmental contexts.

Cis-Regulatory Architecture and Vertebrate Evolution

Comparative studies across vertebrate species reveal fundamental principles of regulatory evolution. The development of UUATAC-seq—an ultra-throughput, ultra-sensitive single-nucleus assay for transposase-accessible chromatin—has enabled comprehensive mapping of candidate CREs (cCREs) across five representative vertebrate species [20]. This approach revealed that genome size differences across species influence the number but not the size of cCREs, suggesting constraints on the fundamental unit of regulatory function.

Deep learning models like NvwaCE can predict cis-regulatory landscapes directly from genomic sequences with high precision, demonstrating that regulatory grammar is more conserved than nucleotide sequences [20]. These models have accurately predicted the effects of synthetic mutations on lineage-specific cCRE function, aligning with causal QTLs and genome editing results. The organization of cCREs into distinct functional modules helps explain how conserved regulatory logic can generate diverse morphological outcomes across vertebrate evolution.

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Studying Cis-Regulatory Evolution

| Method | Primary Application | Key Readout | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq | Mapping transcription factor binding sites | Protein-DNA interactions | Low-throughput, requires specific antibodies |

| ATAC-seq | Identifying accessible chromatin regions | Chromatin accessibility | Does not directly measure regulatory activity |

| UUATAC-seq | High-throughput cCRE mapping across species | Comparative chromatin accessibility landscapes | Technical complexity, analysis challenges |

| CRISPR/Cas9 screening | Functional validation of CREs | Phenotypic consequences of regulatory mutations | Throughput limitations, pleiotropic effects |

| Deep learning models | Predicting regulatory grammar from sequence | cis-regulatory activity predictions | Black box limitations, training data requirements |

| Interspecific QTL mapping | Linking regulatory regions to phenotypes | Genotype-phenotype associations | Resolution limitations, complex trait architecture |

Methodologies: Experimental and Computational Approaches

Mapping Cis-Regulatory Elements

Comprehensive identification of functional CREs requires integrating multiple experimental and computational approaches. Experimental methods include:

- Chromatin accessibility assays (ATAC-seq, DNase-seq): Identify nucleosome-depleted regions where transcription factors can bind.

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq): Directly maps binding sites for specific transcription factors or histone modifications.

- DNA methylation profiling: Identifies hypomethylated regions that often overlap with functional CREs.

Computational approaches include:

- Conserved non-coding sequence (CNS) detection: Uses evolutionary conservation to identify putative functional elements.

- Deep learning models (e.g., NvwaCE, OmniReg-GPT): Predict regulatory activity directly from DNA sequence.

Integration of these methods, as demonstrated in maize studies, generates high-confidence CRE maps that outperform any single approach [22]. Benchmarking against experimental gold standards (e.g., ChIP-seq data) reveals complementary strengths of different methods, with integration maximizing both completeness and precision of CRE identification.

Forward-Time Simulations of GRN Evolution

Computational frameworks like EvoNET simulate forward-in-time evolution of GRNs in populations, incorporating both natural selection and random genetic drift [18]. These simulations implement:

- Realistic regulatory architectures with separate cis and trans regulatory regions

- Mutation models that alter regulatory interactions

- Fitness evaluation at the phenotypic level based on distance from an optimal phenotype

- Population dynamics including competition and reproduction

EvoNET simulations have confirmed that populations evolving under stabilizing selection develop increased robustness to mutations and that neutral variation facilitates evolutionary innovation by enabling exploration of genotype space [18]. These models provide insights into how selective pressures shape the evolvability of GRNs and the emergence of regulatory robustness.

Foundation Models for Genomic Sequence Understanding

Recent advances in foundation models represent a paradigm shift in computational analysis of regulatory sequences. OmniReg-GPT is a generative foundation model specifically designed for long genomic sequence understanding, addressing previous limitations in processing extended regulatory contexts [23]. Key innovations include:

- Hybrid attention mechanism combining local and global attention blocks to capture both short-range regulatory grammar and long-range genomic interactions

- Linear computational complexity enabling processing of sequences up to 200 kb

- Generative capabilities allowing creation of candidate cell-type-specific enhancers through prompt engineering

These models demonstrate exceptional performance in diverse regulatory prediction tasks, including cis-regulatory element identification, context-dependent gene expression prediction, and 3D chromatin contact modeling [23]. The ability to process long genomic contexts is particularly valuable for understanding complex regulatory landscapes where interactions occur across large genomic distances.

Visualization: Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Cis-Regulatory Evolution Cascade: This diagram illustrates the mechanistic pathway from sequence variation to evolutionary change, highlighting how experimental approaches interrogate specific stages of the process.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Regulatory Evolution

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Function | Example Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| UUATAC-seq reagents | Ultra-throughput chromatin accessibility profiling | Comparative cCRE mapping across species [20] | Single-nucleus resolution, species-wide application |

| CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Precise genome editing for functional validation | Wnt enhancer knockout in silkworms [21] | Tissue-specific delivery, multiplexed targeting |

| OmniReg-GPT model | Long-sequence genomic understanding | Enhancer prediction, regulatory grammar decoding [23] | 200 kb context window, generative capabilities |

| NvwaCE deep learning model | cis-regulatory landscape prediction | Synthetic mutation effect prediction [20] | Cross-species applicability, functional module identification |

| EvoNET simulation framework | GRN evolution modeling | Robustness and drift studies [18] | Forward-time population genetics, phenotypic selection |

| Integrated CRE maps | Reference regulatory annotations | Drought-responsive GRN construction in maize [22] | Multi-method integration, improved TFBS prediction |

The study of regulatory evolution has progressed from individual case studies toward a comprehensive understanding of the principles governing how sequence changes reshape phenotypes through GRN modification. Key insights emerging from recent research include:

First, the relationship between cis-regulatory sequence divergence and functional conservation is more complex than previously recognized. Covertly homologous elements that retain similar functions despite significant sequence divergence challenge simple homology assessments based solely on sequence similarity [19]. This underscores the importance of functional validation and the value of deep learning models that can identify conserved regulatory grammar beyond primary sequence.

Second, the interdependence of cis-regulatory elements and their frequent pleiotropy necessitates network-level understanding rather than element-centric approaches. The fragility or robustness of specific cis-regulatory architectures may predict evolutionary potential, with fragile architectures enabling rapid evolution and robust architectures constraining phenotypic change [19].

Third, technological advances in long-sequence foundation models and high-throughput functional genomics are dramatically expanding our ability to decode regulatory landscapes. Models like OmniReg-GPT that can process 200 kb sequences will enable researchers to capture the full complexity of regulatory contexts, including long-range interactions and multi-element coordination [23].

As these capabilities mature, the field moves closer to predictive understanding of how regulatory sequences encode morphological outcomes—a fundamental goal with profound implications for evolutionary biology, regenerative medicine, and synthetic biology. The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation across diverse organisms will continue to reveal the fundamental principles governing the journey from regulatory sequence to phenotypic diversity.

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) represent the complex architecture of interactions between transcription factors, cis-regulatory elements (CREs), and their target genes, governing developmental processes and cellular functions. The evolution of these networks is a primary driver of phenotypic diversity. Within a broader thesis on cis-regulatory mutations, this review examines three specific modes of GRN evolution: in place modification of existing networks, evolution through serial homology in repeated structures, and non-homologous co-option of networks for novel functions. Genetic variants within CREs—non-coding DNA sequences that regulate the spatial and temporal expression of genes—have been critical drivers of phenotypic transitions from wild to cultivated plants during domestication and are presumed to play equally important roles in natural adaptation [9]. These variants can arise de novo or from mutations in ancestral elements, subtly altering gene expression patterns without the deleterious pleiotropic effects often associated with protein-coding mutations. The framework for understanding GRN evolution now integrates advanced computational simulations, such as the EvoNET system, which models how populations of GRNs evolve forward-in-time through the interplay of genetic drift and natural selection operating on phenotypic outcomes [18]. These models confirm that natural selection, combined with neutral processes, modifies gene expression and the properties of GRNs, favoring variants that produce robust phenotypes under mutation pressure.

In Place Evolution of GRNs

Concept and Mechanistic Basis

"In place" evolution describes the modification of an existing GRN within its native developmental and cellular context, without duplication or redeployment to a novel location. This mode typically involves cis-regulatory mutations that fine-tune the expression of genes within the network, or trans-regulatory mutations that alter the specificity or activity of transcription factors. The structure of the GRN itself imposes constraints on the potential evolutionary paths; networks characterized by properties such as sparsity, hierarchical organization, and modularity tend to dampen the effects of perturbations, thereby influencing the distribution of mutation effects [24]. The EvoNET simulation framework demonstrates that GRNs evolve robustness—the resilience to buffer the deleterious effects of mutations—after evolving under stabilizing selection. This robustness often stems from redundancy, which can be implemented through gene duplication or via unrelated genes performing similar functions, allowing for thorough exploration of the genotype space and facilitating evolutionary innovation [18].

Experimental Evidence and Key Findings

A key experimental system for studying in-place evolution is the Auxenochlorella, a genus of oleaginous green algae. These diploid algae exhibit efficient site-specific homologous recombination in their nuclear genomes, a rarity among green algae, making them highly amenable to genetic manipulation and reverse genetics studies [25]. Research has revealed that Auxenochlorella are allodiploid hybrids, resulting from the crossing of divergent parental species. During asexual division, these algae experience pervasive loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) events, which can unmask recessive alleles and create novel genotypic and phenotypic states. Furthermore, the emergence of trisomy (aneuploidy) provides another mechanism for rapid in-place evolution by altering gene dosage [25]. These processes—hybridization, mitotic recombination, LOH, and aneuploidy—parallel evolutionary forces previously well-characterized in yeasts and illustrate how a diploid genome can evolve within its original cellular framework.

Table 1: Quantitative Data from In Place GRN Evolution Studies in Auxenochlorella

| Measurement | Value | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Haploid Genome Length | 22 Mb | Streamlined genome size [25] |

| Genes per Haplotype | ~7,500 | Gene content in a phased diploid genome [25] |

| Genes with Antisense lncRNAs | ~10% | Potential regulatory mechanism for DNA repair and sex genes [25] |

| Promoter Methylation | Periodic Adenine | Potential cis-regulatory influence [25] |

| Gene Body Methylation | Periodic Cytosine | Potential impact on gene expression [25] |

Experimental Protocol: Site-Specific Genetic Manipulation in Auxenochlorella

The following protocol is adapted from methods used to achieve targeted genetic manipulation in Auxenochlorella, enabling the functional study of in-place GRN evolution [25].

- Toolkit Construction: Assemble a genetic toolkit containing several selectable markers (e.g., antibiotic resistance genes), inducible promoters, and fluorescent protein genes for localization studies.

- Vector Design: Clone the gene of interest (e.g., for knockout, reporter expression, or mutant complementation) into an expression vector. Flank the construct with DNA sequences homologous to the target genomic locus (5' and 3' homology arms; typically 500-1000 bp each) to facilitate homologous recombination.

- Transformation: Introduce the linearized DNA construct into Auxenochlorella cells via established transformation methods such as electroporation or glass bead agitation.

- Selection: Plate transformed cells onto solid medium containing the appropriate selective agent (e.g., antibiotic) and incubate under optimal growth conditions (e.g., light for phototrophic growth or glucose for heterotrophic growth).

- Screening: Screen for successful homologous recombination events by PCR amplification across the 5' and 3' junctions of the integrated DNA using gene-specific and vector-specific primers. For fluorescent reporters, confirm protein localization via fluorescence microscopy.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Characterize the phenotypic consequences of the genetic manipulation through analyses of growth rate, lipid content, photosynthetic efficiency, or transcriptome profiling (RNA-seq).

GRN Evolution via Serial Homology

Concept and Mechanistic Basis

Serial homology refers to the evolution of repeated anatomical structures—such as teeth, vertebrae, or limbs—derived from a common developmental blueprint. While these serial organs may diverge morphologically, their development is governed by shared, co-evolved GRNs. The evolution of one organ in a series can consequently drive compensatory or correlated changes in the GRNs of other, potentially phenotypically stable, serial organs, a process linked to developmental system drift [26]. This mode of evolution challenges the simplistic view that morphological stasis implies developmental stasis.

Experimental Evidence and Key Findings

A seminal study comparing molar tooth development in mice and hamsters provides a compelling example of GRN evolution via serial homology. The mouse upper molar is an evolutionary novelty, having acquired two additional cusps not found in its hamster ancestor. Surprisingly, comparative transcriptomic time-series of developing upper and lower molars revealed that while the mouse lower molar underwent limited morphological change, its developmental trajectory evolved as much as that of the upper molar [26]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the transcriptome data showed that the first component (47.8% variance) separated species (mouse vs. hamster), while the time axis accounted for 10.2% of variance. Upper and lower molars were separated only on the sixth component (3% variance), indicating deep developmental similarity [26]. This finding suggests that shared changes in the GRN, some of which are clearly involved in the novel upper molar phenotype, have organ-specific effects on the final morphology. A similar pattern was observed in bat limbs, where extensive co-evolution of wing and leg transcriptomes accompanied the extreme phenotypic divergence of the wing, suggesting this may be a general principle for serial organ evolution [26].

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Serial Homology GRN Studies in Molars

| Measurement | Value | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Component 1 (Species) | 47.8% of variance | Major transcriptome difference is between species [26] |

| Principal Component 2 (Time) | 10.2% of variance | Represents conserved developmental progression [26] |

| Principal Component 6 (Organ Identity) | 3.0% of variance | Underlying similarity between upper/lower molar GRNs [26] |

| Mouse-Hamster Divergence | Highest in upper molars | Correlates with novel two-cusp phenotype [26] |

| Transcriptome Divergence | Constant with early peaks | Contradicts pure "terminal addition" model [26] |

Experimental Protocol: Comparative Transcriptomics for Serial Organ GRN Analysis

This protocol outlines the methodology for comparing developmental GRNs across serial organs and species, as used in the mouse-hamster molar study [26].

- Sample Collection: Collect serial organs (e.g., upper and lower molars, or forelimbs and hindlimbs) from model and reference species across a dense time series covering key stages of organogenesis. Precise developmental staging is critical.

- RNA Sequencing: For each sample, extract total RNA and prepare sequencing libraries. Sequence to a sufficient depth (e.g., 30 million reads per sample) using standard RNA-seq protocols.

- Data Processing and Homologization: Align RNA-seq reads to the respective reference genomes. Normalize expression counts (e.g., using TPM) to account for technical variation. Homologize developmental time series between species using known conserved landmarks (e.g., initiation of first cusp patterning).

- Temporal Expression Modeling: Model temporal expression profiles for each gene in each organ using polynomial regression or similar smoothing techniques.

- Divergence Quantification: Calculate the pairwise distance between the fitted expression curves (e.g., between mouse upper molar and hamster upper molar) across multiple time windows during development.

- Identification of Co-evolved Changes: Use statistical tests (e.g., differential expression, PCA) to identify genes and pathways whose expression dynamics have diverged in one organ and also changed in a correlated, though potentially phenotypically silent, manner in a serial organ.

Non-Homologous Co-option of GRNs

Concept and Mechanistic Basis

Non-homologous co-option involves the recruitment of an existing GRN to govern an entirely new developmental process or structure that is not evolutionarily related to its original context. This mode of evolution relies on the modularity and hierarchical organization of GRNs, which allow a self-contained regulatory sub-circuit (a "module") to be decoupled and reactivated in a novel location or time. The small-world, scale-free topology of biological networks—characterized by short path lengths between nodes and a power-law distribution of connectivity—facilitates such co-option by ensuring that regulatory modules are accessible and can be integrated with new inputs and outputs [24].

Insights from Computational Modeling

While empirical examples of non-homologous co-option are abundant (e.g., the recruitment of eye lens crystallins from various metabolic enzymes), computational models provide key insights into the network properties that make co-option feasible. Simulations using generated GRN structures reveal that properties like sparsity, modular groups, and degree dispersion not only make networks robust to perturbations but also create discrete, semi-autonomous functional units that are primed for co-option [24]. Furthermore, the EvoNET simulator shows that neutral variation—genetic changes with no immediate effect on the phenotype—allows GRNs to explore a wide genotype space, potentially generating latent regulatory circuits that can be co-opted later for new functions without disrupting the original network output [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for GRN Evolution Studies

| Reagent / System | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Auxenochlorella Spp. | Diploid green algae with efficient homologous recombination for targeted genetic manipulation. | In-place GRN evolution studies via gene knockouts, allele-specific transformation, and tracking loss-of-heterozygosity [25]. |

| OrthoRep System | An orthogonal DNA polymerase-plasmid pair in yeast that mutates user-defined genes ~100,000-fold faster than the host genome. | Continuous directed evolution of genes in vivo to study adaptive trajectories and map fitness landscapes of GRN components [27]. |

| EvoNET Simulator | A forward-in-time simulator that models the evolution of GRN populations under selection and genetic drift. | Theoretical study of how GRN properties (robustness, redundancy) evolve and respond to mutations over generations [18]. |

| PRISM-GRN | A Bayesian model that integrates scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, and prior knowledge to infer cell type-specific GRNs. | Reconstructing context-specific GRNs from single-cell multiomics data to identify co-opted networks or diverged regulatory connections [28]. |

| Perturb-seq | A CRISPR-based method for performing large-scale genetic perturbations coupled with single-cell RNA sequencing. | High-throughput experimental mapping of causal regulatory interactions and functional consequences within a GRN [24]. |

Integrated Visualization of GRN Evolutionary Modes

The study of GRN evolution has moved beyond a gene-centric view to embrace the complexity of network dynamics, structure, and constraint. The three modes explored—in place modification, evolution via serial homology, and non-homologous co-option—collectively highlight the central role of cis-regulatory changes in driving phenotypic innovation. The integration of powerful new model systems like Auxenochlorella, sophisticated evolutionary simulations like EvoNET, and high-resolution multiomics inference tools like PRISM-GRN, provides an unprecedented toolkit for dissecting the causal relationships between CRE variation, GRN architecture, and evolutionary outcomes. Future research, particularly leveraging single-cell multiomics and continuous directed evolution platforms, will continue to refine our understanding of how the interplay of selection, drift, and network topology shapes the diverse tapestry of life.

Decoding the Regulatory Code: Computational and Experimental Approaches for Mapping Mutational Impact

The precise mapping of cis-regulatory elements (CREs) is fundamental to understanding the evolution of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) and the phenotypic diversity in eukaryotic organisms. These elements, which include promoters, enhancers, and silencers, fine-tune spatiotemporal gene expression without altering the protein-coding sequence itself. Over the past decade, three high-throughput genomic technologies—ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and Hi-C—have become indispensable tools for creating comprehensive maps of these regulatory landscapes. These techniques enable researchers to identify accessible chromatin regions, transcription factor binding sites, and long-range chromatin interactions, respectively.

When integrated, these methods provide a powerful multi-modal framework for dissecting how cis-regulatory mutations influence transcriptional output, shape GRN topology, and ultimately drive evolutionary processes. Technical advances have steadily improved the resolution and scalability of each method, facilitating their application across diverse species, including emerging model organisms and crops with complex genomes [29]. This guide details the core principles, methodologies, and integrated application of these technologies, with a specific focus on their role in elucidating the mechanisms of GRN evolution.

Technology-Specific Methodologies and Applications

ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing)

ATAC-seq is a rapid and sensitive method for profiling genome-wide chromatin accessibility. Its principle relies on the Tn5 transposase, which simultaneously fragments DNA and inserts sequencing adapters into open chromatin regions, a process known as tagmentation. These accessible regions are typically nucleosome-free and enriched for active regulatory elements [30].

- Experimental Protocol: For bulk ATAC-seq, fresh tissue or cells are first lysed to isolate nuclei. Critical optimization steps include using the right number of intact nuclei and avoiding over-digestion during the tagmentation reaction. The nuclei are then incubated with the Tn5 transposase. After tagmentation, the DNA is purified and amplified by PCR to create the sequencing library. For challenging samples, such as those from emerging model organisms, preservation methods can significantly impact chromatin integrity; preserving the homogenate in cell culture medium is recommended over direct cryopreservation of tissue [29].

- Key Applications: Beyond merely identifying open chromatin, ATAC-seq data can be used for nucleosome positioning and transcription factor (TF) footprinting, which infers TF binding based on characteristic patterns of protection from tagmentation [30]. In evolutionary and ecological contexts, ATAC-seq has been applied to study caste determination in social insects and morphological diversification in arthropods [29].

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for ATAC-seq

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase | Fragments DNA and inserts sequencing adapters into accessible genomic regions. | Highly active; preferentially targets open chromatin. |

| Cell Culture Medium | Tissue preservation medium for chromatin integrity. | Superior to direct cryopreservation for some samples [29]. |

| Nuclei Isolation Buffers | Lyses cell membrane while keeping nuclear membrane intact. | Species- and tissue-specific optimization is often required [29]. |

| Biotin-Streptavidin System | (In TAC-C) Isolates biotin-labeled chromatin ligation products [31]. | Used in integrated methods like TAC-C. |

ChIP-seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by Sequencing)

ChIP-seq is the gold-standard method for identifying genome-wide binding sites of specific proteins, such as transcription factors or histone modifications. It provides direct evidence of protein-DNA interactions, offering a snapshot of the regulatory state of a cell.

- Experimental Protocol: Cells are first cross-linked with formaldehyde to preserve protein-DNA interactions. The chromatin is then fragmented, typically by sonication. An antibody specific to the protein of interest is used to immunoprecipitate the protein-DNA complexes. After reversing the cross-links, the co-precipitated DNA is purified and sequenced. A significant challenge is the limited availability of high-quality, specific antibodies, which restricts the feasible TF-cell type combinations that can be studied [32].