Beyond the Mouse: How Model Organisms Are Revolutionizing Evolutionary Developmental Biology and Biomedical Research

This article explores the pivotal role of model organisms in evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo) and its implications for biomedical science.

Beyond the Mouse: How Model Organisms Are Revolutionizing Evolutionary Developmental Biology and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the pivotal role of model organisms in evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo) and its implications for biomedical science. It covers the foundational principles of using species from fruit flies to zebrafish to understand conserved developmental mechanisms. The article details methodological advances that are expanding the repertoire of research organisms, analyzes the limitations and challenges of translating findings from models to humans, and provides a comparative framework for validating and selecting appropriate models for specific research questions. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how a diversified approach to model organisms, including non-traditional and wild species, is crucial for unlocking fundamental biological processes and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

The Evolutionary Bedrock: How Model Organisms Reveal Conserved Developmental Principles

Model organisms are defined as non-human species that are extensively studied in the laboratory to understand specific biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries will provide insight into the workings of other organisms [1]. In evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), this model system strategy achieves a unique synthesis, negotiating the tension between developmental conservation and evolutionary modification to address fundamental questions about the evolution of development and the developmental basis of evolutionary change [2]. These organisms instantiate a research approach that combines model system strategies from developmental biology with comparative methods from evolutionary biology, creating a powerful framework for investigating both deep homology and evolutionary novelty.

The selection of model organisms is not arbitrary; researchers consider multiple criteria including genetic tractability, life cycle duration, accessibility to genetic manipulation, and relevance to human biology or particular evolutionary questions [2]. The remarkable advances made in healthcare and modern medicine are largely attributable to insights gained from model organisms, as they enable research that would be difficult, inappropriate, or unethical to conduct on humans [1]. As evo-devo has matured as a discipline, the scope of model organisms has expanded beyond classical genetic workhorses to include non-traditional species that offer unique windows into evolutionary processes, developmental mechanisms, and the origins of biological diversity.

Classification and Characteristics of Model Organisms

Categorical Framework

Model organisms in evolutionary developmental biology can be categorized according to their phylogenetic position, experimental advantages, and the specific biological questions they address. The distinction between "exemplary" and "surrogate" models is particularly relevant in evo-devo contexts, where some organisms serve as broad representatives of taxonomic groups while others are chosen to investigate specific evolutionary transitions or developmental mechanisms [2].

Table 1: Classification of Model Organisms in Evolutionary Developmental Biology

| Category | Definition | Primary Research Applications | Representative Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Genetic Models | Organisms with well-established genetic tools and extensive historical data | Gene function analysis, mutational studies, genetic pathways | Drosophila melanogaster, Arabidopsis thaliana, Mus musculus |

| Emerging Evo-Devo Models | Species chosen for specific evolutionary positions or unique biological features | Evolutionary origins of developmental processes, body plan evolution | Nematostella vectensis, Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus, Ambystoma mexicanum (axolotl) |

| Non-Traditional Systems | Organisms recently developed for laboratory study with unique biological properties | Regeneration, extreme adaptation, novel trait evolution | Tardigrades, Volvox, Pomacea canaliculata (apple snail) |

| Comparative Bridge Species | Species that span key evolutionary transitions | Understanding major evolutionary innovations | Zebrafish, corn snake, mayfly (Cloeon dipterum) |

Quantitative Comparison of Key Model Organisms

The selection of an appropriate model organism requires careful consideration of technical and biological parameters. The following table provides a comparative overview of representative species across key practical and biological dimensions.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Model Organisms in Evo-Devo Research

| Organism | Average Generation Time | Genome Size (Approx.) | Genetic Tractability | Key Evo-Devo Research Applications | Notable Biological Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (mouse-ear cress) | 4-6 weeks [1] | ~135 Mb | High (efficient transformation) | Plant development, evolutionary genetics | Small stature, self-fertile, numerous ecotypes |

| Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) | 8-10 days [1] | ~180 Mb | High (extensive genetic tools) | Body patterning, Hox gene function, organ development | Simple nervous system, complete connectome |

| Danio rerio (zebrafish) | 3 months [1] | ~1.4 Gb | Moderate-High (transgenesis, CRISPR) | Vertebrate development, organogenesis, disease modeling | Transparent embryos, external development |

| Nematostella vectensis (starlet sea anemone) | 3-4 months | ~450 Mb | Moderate (morpholinos, CRISPR) | Origins of bilateral symmetry, axial patterning [2] | Regenerative capacity, simple body plan |

| Pomacea canaliculata (apple snail) | 4-6 months | ~Unknown | Emerging (genetic tools developing) | Complete camera-type eye regeneration [3] | Regenerative capacity, complex eye structure similar to vertebrates |

Application Notes: Research Applications in Evolutionary Developmental Biology

Investigating Evolutionary Origins with Basal Metazoans

The starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis has emerged as a critical model for understanding the evolutionary origins of key developmental processes. As a cnidarian, it occupies a phylogenetic position that provides insights into the last common ancestor of bilaterians, making it exceptionally valuable for studying the evolution of axial patterning and the origins of bilateral symmetry [2]. Research using Nematostella has revealed that Hox and Dpp expression patterns previously associated exclusively with bilaterians are present in cnidarians, suggesting deep evolutionary origins for these patterning systems [2]. More recent studies have identified an axial Hox code that controls tissue segmentation and body patterning in Nematostella, challenging previous assumptions about the evolutionary history of these fundamental developmental mechanisms [2].

The experimental value of Nematostella extends beyond its phylogenetic position. This organism is readily cultivated in laboratory settings, produces large numbers of embryos through external fertilization, and exhibits remarkable regenerative capabilities [2]. These technical advantages, combined with the development of gene manipulation techniques including morpholino knockdown and CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, have established Nematostella as a powerful system for interrogating the evolution of developmental mechanisms. Recent single-cell atlas comparisons of cnidarians like Hydractinia and Nematostella have revealed unexpected cellular diversity in mechanosensory neurons, suggesting more complex evolutionary histories of neural cell types than previously recognized [3].

Understanding Major Evolutionary Transformations in Vertebrates

Snakes have emerged as important model systems for investigating major evolutionary changes in body plan organization, particularly the dramatic elongation of the body axis and reduction of limbs [2]. Studies using corn snakes (Pantherophis guttatus) and other snake species have revealed that reorganization of Hoxd regulatory landscapes underlies the evolution of the snake-like body plan [2]. These changes in gene regulation have been linked to the expansion of thoracic identity at the expense of cervical and lumbar regions, providing a developmental basis for the extreme axial elongation characteristic of snakes.

Research on snake development employs a comparative approach, examining embryonic patterning in snakes alongside other reptiles and model vertebrates to identify both conserved and derived aspects of morphogenesis [2]. These studies have demonstrated that the limbless condition of snakes results from alterations in the deployment of sonic hedgehog signaling and other key patterning pathways during limb bud development [2]. The accessibility of snake embryos for experimental manipulation, including tissue grafting and bead implantation, enables functional testing of hypotheses about the developmental mechanisms underlying evolutionary change. This research program exemplifies how non-traditional model organisms can provide unique insights into the developmental genetics of major evolutionary transitions.

Emerging Models for Novel Biological Insights

Recent technological advances have enabled scientists to explore a wider range of non-traditional organisms that offer unique biological insights [1]. These emerging models include:

- Tardigrades: Used to study survival mechanisms in extreme conditions, revealing fundamental insights about stress tolerance and cellular protection mechanisms [1].

- Volvox: A green alga employed to investigate the evolution of multicellularity from unicellular ancestors, providing a simple system for understanding cell differentiation and coordination [1].

- Pomacea canaliculata: The apple snail has been established as a genetically tractable system to study complete camera-type eye regeneration, revealing conserved mechanisms of eye development and repair [3].

- Cave planarians: Research on these organisms has revealed that reduced adult stem cell fate specification leads to evolutionary eye reduction, demonstrating how progenitor depletion can drive evolutionary diminution of organ size [3].

These emerging models exemplify how organisms with particular biological features can address specific evolutionary and developmental questions that are inaccessible using traditional model systems alone.

Experimental Protocols for Evo-Devo Research

Protocol: Gene Expression Analysis in Non-Traditional Model Organisms

Objective: To characterize spatial and temporal gene expression patterns in the starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis to investigate the evolutionary origins of axial patterning.

Materials and Reagents:

- Nematostella adults and embryos maintained in artificial seawater at 16-18°C

- Fixative: 4% paraformaldehyde in MOPS-buffered artificial seawater

- Proteinase K solution (10 μg/mL in PBS)

- Hybridization buffer for riboprobes

- DIG-labeled RNA probes for target genes (e.g., Hox genes, Dpp)

- Anti-DIG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody

- NBT/BCIP staining solution

- Mounting medium for microscopy

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect Nematostella embryos at desired developmental stages (blastula, gastrula, planula, polyp).

- Fixation: Transfer embryos to fixative for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Permeabilization: Treat fixed embryos with Proteinase K for 10-30 minutes depending on stage.

- Pre-hybridization: Incubate samples in hybridization buffer for 2-4 hours at 65°C.

- Hybridization: Add DIG-labeled RNA probes to hybridization buffer and incubate overnight at 65°C.

- Washes: Perform stringent washes to remove unbound probe.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate with anti-DIG antibody overnight at 4°C.

- Color Reaction: Develop signal with NBT/BCIP staining solution, monitoring under microscope.

- Imaging: Clear samples and image using differential interference contrast microscopy.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For difficult-to-permeabilize stages, consider alternative permeabilization methods including detergent treatment.

- Optimal proteinase K concentration and incubation time should be determined empirically for each developmental stage.

- Signal-to-noise ratio can be improved by increasing wash stringency or adjusting probe concentration.

Protocol: Functional Genetic Analysis in Emerging Model Systems

Objective: To manipulate gene function in developing snake embryos to test hypotheses about the developmental basis of axial elongation and limb reduction.

Materials and Reagents:

- Freshly laid corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) eggs incubated at 29°C

- Physiological saline for reptile embryos

- Morpholino oligonucleotides or CRISPR-Cas9 components

- Microinjection apparatus (puller, injector, manipulator)

- Fine glass needles for microinjection

- Agarose plates for embryo stabilization

- Small molecule inhibitors for signaling pathways (e.g., cyclopamine for hedgehog inhibition)

Procedure:

- Egg Windowing: Carefully open a small window in the eggshell above the embryo using fine forceps.

- Embryo Staging: Stage embryos according to established developmental tables for snakes.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare morpholino or CRISPR-Cas9 solutions in injection buffer with tracking dye.

- Microinjection: Inject solutions into target tissues (e.g., limb buds, axial mesoderm) at appropriate developmental stages.

- Incubation: Reseal eggs with tape and return to incubator for continued development.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Harvest embryos at later stages for morphological analysis (whole-mount imaging, skeletal preparation) and molecular analysis (in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry).

- Validation: Confirm targeting efficiency through sequencing or western blotting where applicable.

Technical Considerations:

- Reptile embryos are particularly sensitive to temperature fluctuations; maintain stable incubation conditions.

- Optimal injection parameters (volume, concentration, timing) must be determined empirically.

- Include appropriate controls (scrambled morpholinos, inactive Cas9) to establish specificity.

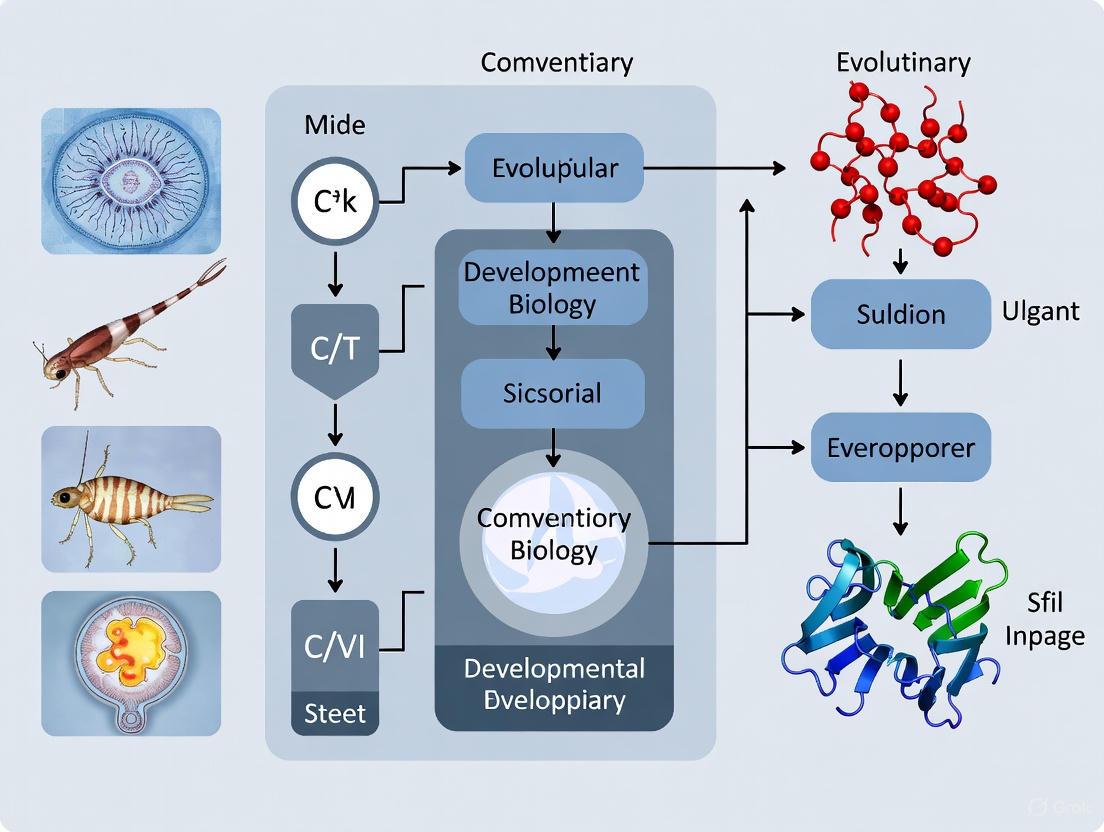

Visualization of Evo-Devo Research Workflows

Experimental Pipeline for Evo-Devo Research

Experimental Pipeline for Evo-Devo Research

Model Organism Selection Algorithm

Model Organism Selection Algorithm

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evo-Devo Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Targeted genome editing for functional genetic analysis | Gene knockout in emerging models (zebrafish, snakes), regulatory element manipulation | Optimization required for each new species; delivery method varies by organism |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Transient gene knockdown by blocking translation or splicing | Rapid functional testing in embryos (Nematostella, fish, frogs) | Controls essential to rule off-target effects; efficacy varies |

| RNAscope/ HCR in situ Hybridization | High-sensitivity detection of RNA expression with single-molecule resolution | Spatial mapping of gene expression in non-traditional species | Works well across diverse species with proper probe design |

| Phalloidin and DAPI Staining | Visualization of F-actin and nuclear architecture | Morphological analysis of embryonic development across species | Universal application across metazoans with minimal optimization |

| Transcriptomic Databases | Comparative gene expression analysis across species and developmental stages | Identifying conserved and novel genetic programs | Cross-species comparisons require careful orthology assignment |

| Species-Specific Antibodies | Protein localization and functional analysis | Cell type identification, protein expression patterns | Limited availability for non-traditional models; often require custom generation |

Future Directions and Technological Integration

The future of model organisms in evolutionary developmental biology is being shaped by technological advances that are expanding the range of organisms accessible to detailed mechanistic study. Single-cell transcriptomic technologies now enable comprehensive characterization of cell type diversity and developmental trajectories across a wide range of species, facilitating comparisons that reveal both conserved and novel features of development [3]. The integration of computational approaches, including artificial intelligence, is beginning to assist researchers in selecting appropriate model organisms by comparing genomic similarity and predicting biological relevance for specific research questions [1].

These technological advances are particularly valuable for the study of non-traditional model organisms, which often possess unique biological features but lack the extensive research infrastructure of classical models. The development of generalized methods for genetic manipulation, including transgenesis and genome editing, is lowering the barrier to establishing new model systems [3]. Similarly, improvements in imaging technologies are enabling detailed morphological analysis without the need for species-specific reagents. As these tools continue to mature, they will further expand the range of biological questions accessible to experimental investigation, strengthening the comparative foundation of evolutionary developmental biology and enabling deeper insights into the developmental mechanisms underlying evolutionary change.

The ongoing expansion of model organisms in evo-devo reflects the field's recognition that biological diversity is not fully represented by traditional laboratory models. By strategically selecting organisms based on phylogenetic position, unique biological features, or specific evolutionary transitions, researchers can address fundamental questions about the evolution of developmental processes that would be inaccessible using any single model system. This comparative approach, supported by increasingly powerful experimental tools, continues to reveal both the deep conservation and striking innovation that characterize the evolution of development across the tree of life.

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway represents one of the most fascinating examples of evolutionary conservation in animal development. First identified in Drosophila through mutational studies that produced larvae with a distinctive "hedgehog-like" appearance, this pathway has since been recognized as a fundamental regulatory system conserved across bilaterians [4]. The core principle emerging from decades of research is that while the fundamental framework of Hh signaling is deeply conserved, significant mechanistic divergence has occurred between Drosophila and vertebrates, offering profound insights for evolutionary developmental biology [5]. This conservation-divergence duality makes the Hh pathway an ideal model for understanding how core developmental mechanisms are both preserved and adapted across evolutionary lineages.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these evolutionary nuances is not merely academic curiosity but has direct implications for therapeutic targeting. The Hh pathway's roles in tissue homeostasis, stem cell maintenance, and its frequent dysregulation in cancers have made it a prime target for pharmaceutical intervention [6]. By examining the conserved core and species-specific adaptations of Hh signaling, we can develop more precise, context-specific therapeutic strategies that account for both universal principles and lineage-specific modifications.

Core Signaling Mechanism: Conserved Framework with Lineage-Specific Adaptations

The Basic Hedgehog Signaling Circuit

The Hh signaling pathway operates through a remarkably conserved framework centered on the interaction between two key transmembrane proteins: Patched (Ptc) and Smoothened (Smo). In the absence of Hh ligand, Ptc inhibits Smo activity, maintaining the pathway in an OFF state. When Hh ligand binds to Ptc, this inhibition is relieved, allowing Smo to activate downstream intracellular events that ultimately regulate transcription factors of the Cubitus interruptus (Ci)/Gli family [5] [4].

This basic circuit exhibits remarkable conservation from Drosophila to humans, but with crucial modifications. In Drosophila, the response to Hh is primarily mediated through the transcription factor Cubitus interruptus (Ci), which can be processed into either a repressor (CiR) or activator (CiA) form depending on Hh signaling status [4]. Vertebrates possess three Gli proteins (Gli1-3) that perform analogous functions, with Gli3 showing the strongest functional similarity to Drosophila Ci in its ability to form both repressor and activator forms [6].

Table 1: Core Components of Hedgehog Signaling Pathway: Drosophila-Vertebrate Comparison

| Component | Drosophila | Vertebrates | Functional Conservation | Key Divergences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | Hedgehog (Hh) | Sonic Hh, Indian Hh, Desert Hh | Dual lipid modification, autoprocessing | Single ligand in flies vs. multiple specialized ligands in vertebrates |

| Receptor | Patched (Ptc) | PTCH1, PTCH2 | Inhibits Smo in absence of Hh | Similar mechanism with potential differences in cholesterol handling |

| Signal Transducer | Smoothened (Smo) | Smoothened (SMO) | GPCR-family protein, activates pathway | Ciliary localization in vertebrates vs. apical-basal polarization in Drosophila |

| Cytoplasmic Complex | Costal-2 (Cos2), Fused (Fu), Suppressor of Fused (Su(fu)) | KIF7, SUFU | Regulates Ci/Gli processing and activity | Cos2 essential in flies, minor role for KIF7 in mammals; reversed importance of Su(fu) |

| Transcription Factor | Cubitus interruptus (Ci) | Gli1, Gli2, Gli3 | Zinc-finger transcription factors, processing into repressors/activators | Single Ci protein vs. three specialized Gli proteins in vertebrates |

Key Mechanistic Divergences Between Drosophila and Vertebrates

Research over the past two decades has revealed fundamental differences in how Hh signals are transduced from Smo to Ci/Gli transcription factors between Drosophila and vertebrates. In Drosophila, the kinesin-like protein Costal-2 (Cos2) plays an essential scaffolding role, forming a complex with Ci, the protein kinase Fused (Fu), and Suppressor of Fused (Su(fu)) that regulates Ci processing and activity [7]. This complex is tethered to microtubules, and Hh signaling triggers its dissociation, allowing Ci activation.

In striking contrast, mammalian Hh signaling has largely dispensed with the Cos2 ortholog KIF7, which plays only a minor role, while Suppressor of Fused (SUFU) has become critically important for pathway regulation [7]. Another major divergence involves the role of primary cilia in vertebrate Hh signaling. While Drosophila cells lack primary cilia, vertebrate Hh signaling is intimately connected to this organelle, with multiple pathway components trafficking through cilia during signal transduction [5]. This fundamental difference in subcellular localization represents one of the most significant adaptations of the pathway in vertebrate evolution.

Diagram 1: Hedgehog signaling mechanism comparison between Drosophila and vertebrates

Quantitative Analysis of Pathway Components and Dynamics

Evolutionary Conservation Metrics

Analysis of sequence conservation and functional studies reveals a complex pattern of evolutionary constraint across Hh pathway components. The ligand-receptor interface shows particularly high conservation, with structural studies demonstrating similar binding modes between Hh and Ptc across species [6]. However, downstream components exhibit varying degrees of conservation, with some elements showing remarkable functional flexibility despite maintaining their core signaling roles.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Hedgehog Signaling Dynamics in Drosophila Wing Imaginal Disc

| Parameter | Value/Range | Experimental Basis | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hh gradient range | 10-15 cells | Fluorescence labeling, antibody staining [8] | Defines short-range patterning vs. longer-range Dpp signaling |

| Response domains | 3 distinct gene expression patterns | Target gene expression analysis (dpp, col, ptc, en) [8] | Establishes distinct cell fates along A-P axis |

| Key phosphorylation sites on Smo | 3 PKA sites, 3 CKI sites | Phospho-mutant analysis [9] | Gradual Smo activation in response to increasing Hh |

| Ptc up-regulation fold-change | >10x baseline | mRNA quantification, Ptc-lacZ reporting [8] | Critical for gradient dynamics and signal interpretation |

| Ci-155 to Ci-75 processing ratio | High in absence of Hh, negligible at high Hh | Western blot, Ci staining intensity [4] | Determines repressor vs. activator balance |

| SMO basolateral enrichment at high Hh | >3x apical levels | SNAP-SMO surface labeling quantification [9] | Correlates with high-level pathway activation |

Dynamic Interpretation of Hedgehog Signaling

Traditional models of morphogen signaling suggested that cells simply read local morphogen concentrations at steady state. However, recent research in Drosophila has revealed that Hh gradient interpretation is far more dynamic. Cells exposed to Hh not only measure current concentration but also incorporate their history of Hh exposure, a phenomenon described as "temporal integration" [8].

Mathematical modeling of the Hh signaling network predicts that a static Hh gradient would be insufficient to specify the multiple distinct gene expression patterns observed in the wing imaginal disc. Instead, a transient "overshoot" of the Hh gradient occurs during development, where the Hh profile expands compared to its final steady-state distribution [8]. This dynamic behavior arises from the network architecture itself, particularly the Hh-dependent up-regulation of its receptor Ptc, which subsequently limits Hh spread through ligand sequestration and degradation.

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Hedgehog Signaling

Monitoring Smo Trafficking and Subcellular Localization

Purpose: To investigate Hh-dependent regulation of Smo subcellular localization and its relationship to signaling strength in Drosophila epithelial cells.

Background: In polarized epithelia like the wing imaginal disc, Hh signaling involves compartmentalization of pathway components along the apico-basal axis. Recent studies demonstrate that high Hh signaling promotes Smo stabilization and redistribution to basolateral membranes [9].

Materials:

- Drosophila strains: SNAP-tagged Smo (SNAP-SMO)

- Non-liposoluble fluorescent SNAP ligands (e.g., SNAP-Cell 647-SiR)

- Standard Drosophila culture materials

- Confocal microscopy setup with capability for XZ sectioning

- Antibodies: anti-DLG (septate junctions), anti-Ci

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Express SNAP-SMO in dorsal compartment of third instar larval wing imaginal discs using ap-Gal4 driver.

- Surface Labeling: Dissect discs in cold Schneider's medium and incubate with non-liposoluble SNAP ligand (1 μM) for 10 minutes at 4°C to specifically label cell surface SNAP-SMO.

- Fixation and Staining: Fix discs in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, then immunostain with anti-DLG to mark apical junctions and anti-Ci to identify anterior compartment and regions with different Ci forms.

- Imaging: Acquire confocal Z-stacks with approximately 0.5 μm steps across entire apico-basal axis.

- Quantification: Using XZ projections, measure fluorescence intensity in three defined regions:

- Apical region: 15% most apical region based on DLG staining

- Basal region: 10% most basal part

- Lateral region: intermediate region between apical and basal

Interpretation: High Hh signaling leads to pronounced basolateral enrichment of surface Smo. This redistribution depends on the sequential action of PKA, CKI, and Fu kinase, with Fu required for the extreme basal accumulation observed at highest Hh levels [9].

Mapping Ci/Gli Chromatin Binding Sites

Purpose: To identify direct transcriptional targets of Ci/Gli transcription factors and investigate tissue-specific responses to Hh signaling.

Background: While core pathway components respond similarly to Hh across tissues, many tissue-specific effects suggest collaboration between Ci/Gli and other transcription factors. Identifying genomic binding sites reveals how tissue-specific responses are generated.

Materials:

- Drosophila embryos (2-6 hours old)

- DamID constructs: pUAST-DamCi76 (repressor), pUAST-DamCim1-m4 (activator)

- Genomic DNA isolation kit

- DpnI and DpnII restriction enzymes

- Adaptor oligos for amplification

- Microarray or sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Transgenic Expression: Cross DamCi fusion lines to appropriate Gal4 drivers for embryonic expression.

- DNA Isolation: Extract genomic DNA from 2-6 hour old embryos containing DamCi or Dam transgenes.

- Methylation-Specific Digestion: Digest 2.5 μg DNA with DpnI (cuts only methylated GATC sites).

- Adaptor Ligation: Ligate DpnI-digested DNA with double-stranded adaptor oligos.

- Secondary Digestion: Digest with DpnII (cuts unmethylated GATC sites) to fragment unmethylated DNA.

- Amplification: PCR-amplify methylated DNA fragments using adaptor-specific primers.

- Detection: Label amplified fragments with Cy dyes and hybridize to genome tiling arrays or prepare for sequencing.

Interpretation: This DamID approach identifies genomic regions bound by Ci repressor and activator forms. Comparison with expression profiling of Hh pathway mutants reveals direct versus indirect targets. Most non-core pathway targets show tissue-specific regulation, indicating collaboration with Hh-independent transcription factors [10].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflows for analyzing Smo trafficking and Ci chromatin binding

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hedgehog Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tagged Pathway Components | SNAP-tagged Smo | Live imaging of Smo trafficking and surface levels | Enables specific labeling of cell surface pool; functional in rescue assays [9] |

| Signaling Reporters | Ptc-lacZ, Ci-lacZ, Hh-responsive GFP | Readout of pathway activity | Reveals spatial domains of signaling; dynamic response to Hh levels [8] |

| Kinase Tools | PKA, CKI, Fu mutants and inhibitors | Dissecting phosphorylation-dependent regulation | Identify sequential kinase actions in Smo activation [9] |

| Chromatin Mapping | DamCi fusions (Ci76, Cim1-m4) | Genome-wide identification of binding sites | Distinguish repressor vs. activator binding; tissue-specific targets [10] |

| Genetic Tools | hh, ptc, smo, ci mutants; RNAi lines | Loss-of-function studies | Essential for epistasis analysis and pathway dissection |

| Trafficking Inhibitors | Dynamin inhibitors, recycling blockers | Endocytosis and trafficking studies | Reveal importance of vesicular trafficking in pathway regulation [9] |

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Disease Modeling

The evolutionary conservation and divergence of Hh signaling mechanisms have profound implications for therapeutic development. While the core pathway is conserved, the significant differences between Drosophila and vertebrate signaling necessitate careful translation of findings from model systems to mammalian contexts and clinical applications.

For cancer therapeutics targeting aberrant Hh signaling, understanding these distinctions is crucial. The differential importance of SUFU between species suggests that targeting strategies effective in Drosophila may not directly translate to human cancers [7]. Similarly, the ciliary dependence of vertebrate Hh signaling presents both challenges and opportunities for drug development, as cilia-specific targeting could potentially achieve tissue-specific effects [5].

The dynamic interpretation of Hh gradients also has implications for therapeutic intervention. The temporal aspects of signaling interpretation suggest that pulsed versus continuous inhibition strategies might produce different outcomes in pathological contexts [8]. Furthermore, the feedback mechanisms embedded within the pathway, such as Ptc up-regulation and HIB/SPOP-mediated Su(fu) regulation, create built-in resistance mechanisms that must be considered in therapeutic design [11].

From a developmental perspective, understanding how Hh signaling integrates with tissue-specific transcription factors provides a blueprint for regenerative medicine approaches. The demonstration that Hh responses are shaped by collaboration with tissue-specific factors like Trachealess in tracheal development suggests strategies for achieving tissue-specific outcomes in regenerative contexts [10].

As we continue to unravel the complexities of this evolutionarily conserved pathway, the principles emerging from Drosophila studies provide both fundamental insights and practical guidance for manipulating this crucial signaling system in development, homeostasis, and disease.

Evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) represents a synthesis of model system approaches from developmental biology and comparative strategies from evolutionary biology. This framework negotiates the tension between developmental conservation and evolutionary modification to address fundamental questions about the evolution of developmental processes and the developmental basis of evolutionary change [2]. The phylogenetic tree of life provides the essential historical roadmap for this scientific exploration, revealing how developmental genes and processes have been modified to generate the vast diversity of animal body plans observed throughout evolutionary history [2] [12].

Model organisms in evo-devo instantiate a unique reasoning practice that differs from traditional model systems. While classical model organisms like Drosophila or C. elegans were selected for their experimental tractability, evo-devo model species are strategically chosen based on their phylogenetic position to illuminate specific evolutionary transitions [2]. This approach enables researchers to investigate how changes in developmental gene regulation and expression patterns have generated major morphological innovations, from the origin of bilateral symmetry to the evolution of specialized appendages and axial patterning [2].

This protocol article provides detailed methodologies for using phylogenetic position to understand body plan evolution, framed within the broader context of model organism research in evolutionary developmental biology. We present specific application notes for three exemplar organisms that span key phylogenetic positions, experimental protocols for phylogenetic analysis and morphological comparison, and visualization tools for integrating phylogenetic and morphological data.

Application Notes: Model Organisms for Key Evolutionary Transitions

The Starlet Sea Anemone (Nematostella vectensis) and the Origins of Bilaterality

Rationale and Phylogenetic Context: The starlet sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis, occupies a critical phylogenetic position as a cnidarian representative, providing insight into the early evolutionary history of animals before the emergence of bilaterality [2]. Cnidarians diverged from the lineage leading to bilaterians approximately 600 million years ago, making them invaluable for reconstructing the ancestral condition of animal development [2].

Key Experimental Findings: Despite their radial symmetry, Nematostella possesses orthologs of many genes that establish the bilateral body plan, including Hox and Dpp (BMP) genes [2]. Surprisingly, these genes are expressed in overlapping axial domains along the oral-aboral axis during Nematostella development [2]. This discovery suggests that the ancestral function of these genes was to pattern the primary body axis, and their role in establishing bilateral symmetry was co-opted later in animal evolution. More recent research has revealed that Nematostella utilizes an axial Hox code to control tissue segmentation and body patterning, demonstrating that sophisticated regulatory mechanisms for axial patterning predate the evolution of bilateral symmetry [2].

Leeches (e.g.,Helobdellaspp.) and the Evolution of Segmentation

Rationale and Phylogenetic Context: Leeces belong to the superphylum Lophotrochozoa, a group that exhibits remarkable diversity in body plans but remains underrepresented in developmental studies compared to ecdysozoans and deuterostomes [2]. Their phylogenetic position makes them essential for understanding whether segmentation—the repetition of body units—has a single evolutionary origin or emerged multiple times independently in different animal lineages [2].

Key Experimental Findings: Studies in leeches have revealed that despite the extensive morphological differences between annelid, arthropod, and vertebrate segments, the genetic machinery for segment formation involves conserved patterning genes [2]. However, the specific regulatory interactions and developmental timing differ significantly, suggesting that segmentation evolved through the modification of a conserved genetic toolkit rather than through entirely novel genetic inventions. This exemplifies the evo-devo principle of "deep homology," where conserved genetic circuits are reconfigured to produce novel morphological structures [2].

The Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) and Major Axial Evolution

Rationale and Phylogenetic Context: Snakes represent one of the most dramatic examples of body plan evolution among vertebrates, with extraordinary modifications to the axial skeleton and loss of limb elements [2]. The corn snake serves as an excellent model for studying the developmental basis of these transformations due to its experimental accessibility and phylogenetic position within the squamate reptiles [2].

Key Experimental Findings: Research on corn snakes has illuminated how major changes in Hox gene expression domains have driven the extensive elongation of the body axis and reduction of limb structures [2]. Snakes exhibit a posterior expansion of Hox gene expression domains that correlates with an increase in vertebral number, particularly in the thoracic region [2]. Additionally, modifications to the Hox code in lateral plate mesoderm have contributed to the loss of forelimbs and reduction of hindlimbs [2]. These changes in gene regulation illustrate how major evolutionary transformations can arise through modifications of existing developmental programs rather than through the evolution of entirely new genes.

Table 1: Strategic Selection of Model Organisms for Key Evolutionary Transitions

| Model Organism | Phylogenetic Position | Evolutionary Transition | Key Genetic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis) | Cnidaria (sister to Bilateria) | Origin of bilateral symmetry | Hox and Dpp genes pattern primary axis before bilaterality evolution [2] |

| Leech (Helobdella spp.) | Lophotrochozoa (Annelida) | Evolution of segmentation | Conserved genetic toolkit with modified regulatory interactions [2] |

| Corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) | Squamata (Reptilia) | Axial elongation and limb reduction | Posterior expansion of Hox domains; modified limb bud Hox code [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Phylogenomic Analysis for Phylogenetic Positioning

Objective: To reconstruct robust phylogenetic relationships using genome-scale data for accurate phylogenetic positioning of target organisms.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality genomic DNA or transcriptome data

- DNA/RNA extraction kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy, RNeasy)

- Sequencing library preparation kits (e.g., Illumina TruSeq)

- PCR reagents and primers for orthologous gene amplification

- Computational resources (high-performance computing cluster recommended)

Procedure:

- Taxon Sampling: Select a broad representation of taxa that spans the phylogenetic diversity of the clade of interest, including appropriate outgroups.

- Data Matrix Construction:

- Identify orthologous genes across sampled taxa using bidirectional BLAST and orthology assessment tools (e.g., OrthoFinder).

- Align amino acid or nucleotide sequences for each orthologous gene using MAFFT or MUSCLE.

- Visually inspect alignments and trim poorly aligned regions using Gblocks or trimAl.

- Concatenate aligned gene sequences into a supermatrix using FASconCAT or custom scripts.

- Phylogenetic Inference:

- Partition the data by gene and/or codon position using PartitionFinder to determine best-fit substitution models.

- Perform maximum likelihood analysis using RAxML or IQ-TREE with thorough bootstrap analysis (≥1000 replicates).

- Alternatively, perform Bayesian analysis using MrBayes or PhyloBayes with appropriate model settings.

- Assess node support using bootstrap values (ML) or posterior probabilities (Bayesian).

- Divergence Time Estimation:

- Calibrate the tree using fossil data or molecular clock constraints.

- Perform dating analysis using BEAST2 or MCMCTree.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Incomplete taxon sampling can lead to systematic error; maximize taxonomic coverage within practical constraints.

- Model misspecification can strongly impact phylogenetic inference; use model testing and partitioned analyses.

- Computational time can be extensive for large datasets; consider approximate methods for initial exploratory analyses.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Orthogroup inference | Identifying orthologous genes across multiple species [13] |

| MAFFT | Multiple sequence alignment | Aligning amino acid or nucleotide sequences [13] |

| RAxML/IQ-TREE | Maximum likelihood phylogenetics | Phylogenetic tree inference from molecular sequences [13] |

| BEAST2 | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Divergence time estimation and phylogenetic inference [13] |

| PhyloScape | Tree visualization | Interactive visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees [13] |

Protocol 2: Comparative Morphometric Analysis of Body Plans

Objective: To quantify and compare morphological variation across species using geometric morphometrics.

Materials and Reagents:

- Specimens for morphological analysis (cleared and stained, CT-scanned, or histological)

- Imaging equipment (microscopes, micro-CT scanners)

- Landmark digitization software (e.g., tpsDig2, MorphoJ)

- R statistical environment with geomorph and morphospace packages

Procedure:

- Landmark Configuration Design:

- Identify homologous anatomical points (landmarks) that capture essential shape information.

- Include Type I (discrete juxtapositions), Type II (maxima of curvature), and Type III (sliding semilandmarks for curves and surfaces) landmarks.

- Data Acquisition:

- Digitize landmarks from physical specimens or digital images using appropriate software.

- For 3D data, use micro-CT scanning and landmark digitization in 3D space.

- Capture semilandmarks along curves and surfaces to comprehensively capture shape.

- Generalized Procrustes Analysis:

- Perform Procrustes superimposition to remove differences in position, orientation, and scale using

geomorph::gpagen(). - This step isolates pure "shape" information for subsequent analysis.

- Perform Procrustes superimposition to remove differences in position, orientation, and scale using

- Morphospace Construction:

- Perform Principal Components Analysis (PCA) on Procrustes-aligned coordinates using

morphospace::mspace(). - Visualize shape variation along principal component axes using wireframes, deformation grids, or 3D models.

- Perform Principal Components Analysis (PCA) on Procrustes-aligned coordinates using

- Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis:

- Map shape data onto phylogenetic trees to create phylomorphospaces using

phytools::phylomorphospace(). - Test for phylogenetic signal using

geomorph::physignal(). - Compare rates of evolution across lineages using

geomorph::compare.evol.rates().

- Map shape data onto phylogenetic trees to create phylomorphospaces using

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Landmark homology is critical; ensure consistent anatomical identification across specimens.

- Missing data can be handled using estimation approaches in geomorph.

- For complex shapes, supplement landmarks with semilandmarks to adequately capture curvature.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for comparative morphometric analysis of body plans, showing key stages from specimen collection to visualization.

Visualization and Data Integration Tools

Phylogenetic Tree Visualization Platforms

PhyloScape is a web-based application for interactive visualization of phylogenetic trees that supports customizable visualization features and includes a flexible metadata annotation system [13]. The platform enables researchers to create publishable, interactive views of trees with extensions for viewing amino acid identity, geometry, and protein structure [13]. PhyloScape's architecture allows real-time tree editing, interactivity between different charts, and composable plug-ins for customizable visualizations, making it applicable to various areas including microbial taxonomy, pathogen phylogeny, and plant conservation [13].

TreeViewer is a flexible, modular software designed to visualize phylogenetic trees with high customizability for publication-quality figures [14]. Its modular design enables users to create customized pipelines that can be applied to different trees, enhancing reproducibility and efficiency [14]. TreeViewer supports multiple tree file formats including Newick, NEXUS, and NCBI ASN.1, and offers a command-line interface for working with large trees and automated pipelines [14].

OneZoom is an interactive tree of life explorer that visualizes evolutionary relationships between millions of species on a single zoomable page [12]. Each leaf represents a different species, and branches illustrate how these species evolved from common ancestors over billions of years [12]. This platform is particularly valuable for education and exploration of evolutionary patterns across the entire tree of life.

Integrated Visualization of Phylogenetic and Morphological Data

The integration of phylogenetic and morphological data requires specialized visualization approaches. The morphospace R package provides a streamlined workflow for building and visualizing multivariate ordinations of shape data [15]. This package integrates with existing geometric morphometrics tools to create morphospaces that can include phylogenetic trees, shape clusters, morphometric axes, and performance landscapes [15].

Figure 2: Workflow for integrating phylogenetic and morphological data to create phylomorphospaces for identifying evolutionary patterns.

Procedure for Creating Phylomorphospaces:

- Data Preparation: Obtain Procrustes-aligned shape coordinates and a time-calibrated phylogenetic tree with matching taxa.

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Estimate ancestral character states for shape variables using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods with

phytools::fastAnc()orgeomorph::procD.pgls(). - Space Construction: Project the phylogenetic tree into the morphospace by connecting ancestor-descendant pairs in the shape space.

- Visualization: Plot the phylomorphospace using

morphospace::mspace()with additional layers for specific clades, evolutionary trajectories, or morphological disparity. - Interpretation: Analyze patterns in the phylomorphospace to identify instances of convergent evolution, phylogenetic constraint, or adaptive radiation.

Table 3: Software Tools for Phylogenetic and Morphological Data Visualization

| Software Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PhyloScape | Web-based tree visualization | Interactive, metadata annotation, multiple plug-ins [13] | Pathogen phylogeny, taxonomic studies [13] |

| TreeViewer | Desktop tree visualization | Modular pipeline, high customizability, command-line interface [14] | Publication-quality figures, large trees [14] |

| OneZoom | Tree of life exploration | Zoomable interface, millions of species, educational focus [12] | Evolutionary patterns across entire tree of life [12] |

| morphospace R | Morphospace construction | Shape ordination, phylogenetic integration [15] | Geometric morphometrics, evolutionary morphology [15] |

Concluding Remarks

The integration of phylogenetic comparative methods with evolutionary developmental biology has transformed our understanding of body plan evolution. By strategically selecting model organisms based on their phylogenetic position rather than solely on experimental convenience, researchers can reconstruct the evolutionary history of developmental processes and identify the genetic and developmental changes responsible for major morphological innovations [2].

The protocols outlined here for phylogenetic analysis, morphometric comparison, and data visualization provide a comprehensive framework for investigating the relationship between phylogenetic position and body plan evolution. As new technologies emerge for genomic sequencing, morphological analysis, and computational visualization, this integrative approach will continue to reveal the deep historical patterns and developmental processes that have generated the remarkable diversity of animal forms throughout evolutionary history.

The tree of life itself continues to be refined as new data and analytical methods become available. Recent mathematical modeling suggests that the living tree of life exhibits multifractal properties, with each branch representing a distinct fractal curve [16]. This sophisticated understanding of phylogenetic structure provides an increasingly powerful foundation for exploring the relationship between evolutionary history and developmental mechanisms that continues to unfold through ongoing research in evolutionary developmental biology.

The concept of deep homology represents a paradigm shift in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), revealing that despite vast morphological divergence, distantly related animals share conserved genetic circuitry for building body structures. This principle is powerfully illustrated through comparative studies of model organisms such as Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly), Mus musculus (laboratory mouse), and Homo sapiens (human). The evo-devo gene toolkit—a set of highly conserved genes controlling embryonic development—forms the mechanistic basis for these deep homologies [17]. These toolkit genes are ancient, often dating back to the last common ancestor of bilaterian animals, and primarily encode transcription factors, signaling ligands, receptors, and morphogens that define cell fates and spatial patterning [17].

Research in model organisms demonstrates that morphological evolution occurs largely through changes in the regulation of conserved toolkit genes rather than through the evolution of entirely new genes. The surprising finding that the same genes control development in flies, mice, and humans has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of developmental evolution and provides powerful experimental approaches for biomedical research [2] [17]. This application note details the experimental evidence, methodologies, and practical applications of these shared genetic tools for research and drug development.

Quantitative Evidence for Conserved Genetic Architecture

Comparative genomic analyses across multiple species reveal striking conservation in both protein-coding sequences and gene regulatory architectures. The genetic architecture of quantitative traits follows similar patterns across flies, mice, and humans, characterized by many loci of small effect [18].

Table 1: Evolutionary Conservation of RecQ Helicase Gene Family Across Species

| Organism | Gene Name | Protein Length (Amino Acids) | Conserved Domains | Chromosomal Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. sapiens (Human) | RECQL5β | 991 | Helicase domain, RECQL5-specific regions | 17q25.2-q25.3 |

| M. musculus (Mouse) | RECQL5β | 982 | Helicase domain, RECQL5-specific regions | 11E2 |

| D. melanogaster (Fruit fly) | RECQ5 | Varies by isoform | Helicase domain, RECQL5-specific regions | Multiple |

| C. elegans (Nematode) | RECQL5 | Varies by isoform | Helicase domain, RECQL5-specific regions | Multiple |

Table 2: Genetic Architecture of Quantitative Traits in Model Organisms

| Organism | Number of Loci for Typical Complex Traits | Distribution of Effect Sizes | Common Experimental Design | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. melanogaster (Fruit fly) | Dozens to hundreds | Exponential distribution: few moderate-to-large effects, many small effects | Recombinant inbred lines; large-scale mapping (2,000+ markers) | Single QTLs often fractionate into multiple closely linked loci with opposing effects |

| M. musculus (Laboratory mouse) | Dozens to hundreds | Exponential distribution (Robertson, 1967) | Crosses between inbred strains; congenic strain analysis | Doubling mapping population from 800 to 1600 more than doubles number of detected QTLs |

| H. sapiens (Human) | Hundreds to thousands | Predominantly small effects (most explain <0.1% of variance) | Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of outbred populations | Discrepancies with model organisms largely explained by allele frequency differences in experimental designs |

The conservation of gene structures across evolutionary time provides independent evidence for deep homology. Analysis of 11 animal genomes demonstrates that intron-exon structure evolution is largely independent of protein sequence evolution, following a clock-like pattern that can inform phylogenetic relationships [19]. This structural conservation reinforces the significance of sequence conservation observed in toolkit genes.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Deep Homology

Protocol 1: Cross-Species Gene Expression Analysis via RNA-seq

Purpose: To quantify expression conservation and identify evolutionary patterns across mammalian species.

Applications: Determining whether a gene's expression level is under stabilizing selection, neutral evolution, or directional selection; identifying deleterious expression levels in disease models.

Workflow:

- Sample Collection: Collect equivalent tissues (brain, heart, kidney, liver, testis) from multiple mammalian species across different evolutionary distances [20].

- RNA Extraction & Sequencing: Extract total RNA using TRIzol method; prepare stranded RNA-seq libraries; sequence on Illumina platform to minimum depth of 30 million reads per sample.

- Ortholog Mapping: Map reads to respective reference genomes using STAR aligner; quantify expression for 10,899 one-to-one orthologs identified through Ensembl Compara [20].

- Evolutionary Modeling: Model expression evolution using Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process with framework that accounts for phylogenetic relationships. The OU process is described by the equation: dXₜ = σdBₜ + α(θ - Xₜ)dt, where σ represents drift rate, α represents strength of selective pressure, and θ represents optimal expression level [20].

- Selection Analysis: Classify genes into categories: (a) neutral evolution (α ≈ 0), (b) stabilizing selection (α > 0, single θ across phylogeny), (c) directional selection (α > 0, different θ in specific lineages) [20].

Protocol 2: Functional Validation via Cross-Species Transgenesis

Purpose: To test whether regulatory elements or coding sequences are functionally interchangeable between species.

Applications: Validating deep homology of developmental genes; identifying conserved regulatory networks; understanding the evolution of morphological structures.

Workflow:

- Vector Construction: Clone candidate gene or regulatory sequence from donor species (e.g., mouse Pax6) into appropriate expression vector with minimal promoter [17].

- Germline Transformation: For Drosophila: inject plasmid into pre-blastoderm embryos along with transposase helper plasmid using standard P-element or φC31 integration. For mouse: perform pronuclear injection of fertilized oocytes [17].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Score transgenic individuals for rescue of mutant phenotypes or ectopic expression effects. For example, assess eye development in Drosophila eyeless mutants expressing mouse Pax6 [17].

- Tissue-Specific Expression: Analyze spatial and temporal expression patterns of transgene via in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry; compare to endogenous expression pattern.

- Quantitative Morphometrics: For structural phenotypes (e.g., limb formation, eye development), use geometric morphometrics to quantify shape differences between experimental groups.

Protocol 3: High-Resolution Mapping of Toolkit Gene Expression

Purpose: To visualize co-expression of multiple toolkit genes with cellular resolution.

Applications: Understanding combinatorial gene regulation in development; comparing gene expression networks across species; validating single-cell RNA-seq findings.

Workflow:

- Probe Design: Design initiator sequences for HCR v3.0 against target genes; order DNA hairpins with fluorophores (Alexa 488, 546, 594, 647) [21].

- Sample Fixation & Permeabilization: Fix tissues in 4% PFA for 45 minutes; permeabilize with proteinase K (10 μg/mL, 5-15 minutes depending on tissue size) [21].

- Hybridization Chain Reaction: Hybridize initiator probes overnight at 37°C; amplify signal with hairpin assembly for 12-16 hours at room temperature [21].

- Imaging & Analysis: Image using confocal or light-sheet microscopy; perform 3D reconstruction of expression patterns; quantify expression domains relative to morphological landmarks.

Visualization of Conserved Genetic Pathways

The conservation of developmental genetic pathways across flies, mice, and humans reveals the deep homology controlling body plan organization and organ formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Deep Homology

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Cross-Species Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies for Conserved Proteins | Anti-PAX6, Anti-DLL/DLX, Anti-HOX | Immunohistochemistry to visualize protein expression patterns; Western blot to confirm conservation | Many commercial antibodies cross-react between mouse and human; limited cross-reactivity to Drosophila |

| In Situ Hybridization Probes | HCR v3.0 RNA probes | Precise spatial localization of gene expression with multiplexing capability | Requires species-specific probe design; effective across all model systems |

| Transgenic Constructs | UAS-GAL4 system (Drosophila); Cre-lox system (mouse) | Tissue-specific manipulation of gene expression; lineage tracing | Species-specific systems with some cross-application (e.g., mouse Pax6 in Drosophila) |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 with species-optimized gRNAs | Targeted gene knockout; knock-in of reporter genes | CRISPR systems work across species with optimization of delivery method and gRNA design |

| Evolutionary Analysis Software | CGL (Comparative Genomics Library); OU model implementations | Analyzing gene structure evolution; modeling expression evolution across phylogenies | Compatible with genomic data from any species |

Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

The deep homology between flies, mice, and humans provides powerful platforms for understanding disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic compounds. Behavioral genetic toolkits represent an emerging frontier, where conserved genes regulate complex behavioral phenotypes across species [22]. Furthermore, the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model of gene expression evolution can identify deleterious expression levels in patient data, nominating candidate disease genes and pathways [20].

The ability to study conserved genetic pathways in complementary model systems accelerates the pace of biomedical discovery. For example, studies of segmentation genes in Drosophila directly informed our understanding of somitogenesis in mammals, while analysis of photoreceptor development in flies provided insights into human retinal diseases [2] [17]. This comparative approach continues to yield dividends for understanding the genetic basis of both normal development and disease states.

Evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) represents a foundational synthesis that merges principles of evolutionary theory with the mechanistic insights of developmental biology. This integrated discipline investigates how changes in developmental processes and regulatory mechanisms generate the phenotypic variation upon which natural selection acts. A core tenet of evo-devo is that evolutionary innovations, including novel body plans and complex structures, often arise from alterations in the genetic toolkit that governs embryonic development [23]. This Application Note provides detailed protocols for key evo-devo methodologies and contextualizes them within the critical framework of model organism selection, which is essential for drawing robust evolutionary inferences.

The choice of model species in evo-devo is not arbitrary; it instantiates a unique synthesis of model systems strategies from developmental biology and comparative approaches from evolutionary biology [2]. This synthesis negotiates a fundamental tension between developmental conservation and evolutionary modification. Research has demonstrated that traditional models like Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans are fast-evolving organisms that have lost many ancestral genes and modified their development more extensively than other bilaterians, thereby complicating evolutionary studies [24]. Consequently, evo-devo has expanded to include a phylogenetically diverse range of organisms—such as the starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis), the polychaete worm (Platynereis dumerilii), and the corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus)—to better reconstruct ancestral states and evolutionary trajectories [24] [2].

Key Concepts and Theoretical Framework

Evo-devo research is guided by several core concepts that describe how developmental processes bias and constrain evolutionary outcomes. Understanding these concepts is prerequisite to designing and interpreting evo-devo experiments.

- Modularity: The organization of developmental processes and anatomical structures into semi-independent units or modules. This allows one module to evolve without necessarily disrupting the function of others, facilitating evolutionary change [25].

- Canalization: The buffering of developmental pathways against genetic or environmental perturbations. This process produces robust phenotypic outcomes but can also store cryptic genetic variation that may be released under altered conditions and become subject to selection [25].

- Developmental Bias: The phenomenon whereby the structure of developmental systems makes some phenotypic variants more likely to arise than others, thereby channeling evolutionary change along certain predictable paths [26].

- Exploratory Mechanisms: Developmental processes that generate excess variation initially, which is then pruned based on functional criteria. A classic example is the overproduction of neurons and synapses, followed by activity-dependent stabilization and elimination, which shapes neural circuits [25].

The following table summarizes the core properties of developmental systems that influence evolvability.

Table 1: Core Properties of Developmental Systems that Facilitate Evolutionary Change

| Property | Definition | Evo-Devo Significance | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Linkage | Coupling between processes is switch-like, not lock-and-key, allowing for easy re-wiring [25]. | Enables evolutionary changes in regulatory networks without disrupting core biochemical functions. | Hormonal signaling triggers can be evolutionarily modified. |

| Versatility | Molecules or processes have flexible requirements or substrates [25]. | Allows for the recruitment of existing genes and pathways to novel developmental contexts. | Same transcription factor used in limb, fin, and appendage development. |

| Exploratory Mechanisms | Overproduction of elements (e.g., neurons, synapses) followed by selective stabilization [25]. | Provides a substrate for selection to mold complex, adaptive structures without requiring precise genetic pre-specification. | Formation of neural circuits and vascular networks. |

| Degeneracy | Different mechanisms can produce the same functional outcome [25]. | Buffers the organism against mutations, increasing robustness and evolvability. | Multiple genetic pathways can lead to a similar behavioral output. |

Experimental Protocols in Evo-Devo

This section provides detailed methodologies for central techniques in evolutionary developmental biology, with a focus on functional genetics in emerging model organisms.

Protocol: Parental RNAi in the WaspNasonia vitripennis

Application: Functional analysis of genes involved in anterior-posterior axis patterning in a long germ-band insect, independent of the derived bicoid system found in Drosophila [24].

I. Principle RNA interference (RNAi) is induced in parental generation wasps by injection of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) into the abdomen of adult females. The dsRNA is incorporated into the developing oocytes, leading to knockdown of the target gene's mRNA in the offspring, allowing for assessment of embryonic phenotypes.

II. Reagents and Equipment

- Nasonia vitripennis (wild-type strain)

- T7 RiboMAX Express RNAi System (Promega)

- PCR primers with T7 promoter sequences

- Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1)

- Microinjection apparatus (e.g., Picospritzer III)

- Borosilicate glass capillary needles

- CO₂ pad for anesthesia

- Standard insect rearing supplies and host pupae (Sarcophaga bullata)

III. Procedure

- dsRNA Template Preparation: Design PCR primers containing T7 promoter sequences to amplify a 300-600 bp fragment of the target gene (e.g., otx). Amplify the template from cDNA.

- dsRNA Synthesis: Use the T7 RiboMAX system to synthesize dsRNA according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- dsRNA Purification: Purify the synthesized dsRNA by phenol:chloroform extraction and precipitate with ethanol. Resuspend the pellet in nuclease-free injection buffer (0.5 mM NaH₂PO₄, 5 mM KCl) to a final concentration of 1-3 µg/µL.

- Microinjection: a. Anesthetize 1-2 day old adult female wasps on a CO₂ pad. b. Back-load a glass capillary needle with the dsRNA solution. c. Using a micromanipulator, carefully inject approximately 50 nL of dsRNA into the abdomen of the female wasp. d. Allow recovered females to mate and then provide them with host pupae for oviposition.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Collect the offspring (F1 generation) embryos and fix them at appropriate developmental time points. Analyze phenotypes via: a. Bright-field microscopy for gross morphological defects (e.g., segment deletion). b. In situ hybridization to examine the expression of downstream segmentation genes (e.g., engrailed, even-skipped).

IV. Interpretation Phenotypes such as the "headless embryo" upon otx knockdown demonstrate the gene's critical, bicoid-like role in anterior patterning in Nasonia, revealing an independent evolutionary solution for long germ-band development [24].

Protocol: Establishing Transgenesis in the Amphipod CrustaceanParhyale hawaiensis

Application: Introduction of foreign DNA for functional genomics and evolutionary comparisons of crustacean and insect developmental mechanisms [24].

I. Principle Plasmid DNA containing a transposable element (e.g., minos from Drosophila hydei) and a fluorescent reporter gene is injected into early embryos. The transposase facilitates integration of the transgene into the host genome, enabling stable germline transmission.

II. Reagents and Equipment

- Parhyale hawaiensis adults and embryos

- Plasmid DNA: Transformation vector containing minos inverted terminal repeats, a promoter (e.g., Phaw-Ubiquitin), and a reporter (e.g., EGFP).

- Helper plasmid: Source of minos transposase mRNA.

- Injection buffer: 0.1 mM NaH₂PO₄, 5 mM KCl.

- Microinjection system and needle puller

- Fine tungsten needles for dechorionation

- Fluorescence dissection microscope

III. Procedure

- Embryo Collection and Preparation: Collect embryos from brood chambers and manually dechorionate using sharpened tungsten needles.

- DNA Preparation: Co-inject the transformation vector and helper plasmid (or synthetically capped transposase mRNA) at a concentration of 100-200 ng/µL each in injection buffer.

- Microinjection: Align dechorionated one-cell or two-cell stage embryos on an agarose ramp. Inject the DNA solution into the cytoplasm using a pressurized glass capillary needle.

- Screening and Rearing: Raise injected embryos (G0 generation) to adulthood. Screen for somatic mosaic expression of the reporter gene at later embryonic stages. Outcross G0 adults to wild-type partners and screen the F1 offspring for ubiquitous fluorescence to identify stable germline transformants.

IV. Interpretation Successful transgenesis enables functional assays (e.g., enhancer trapping, CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis) in a crustacean, permitting direct tests of gene regulatory hypotheses related to appendage diversification and segmentation that are difficult to perform in established insect models [24].

Visualization of Evo-Devo Workflows and Concepts

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate core experimental and conceptual frameworks in evo-devo research.

Evo-Devo Model Organism Selection Logic

Hox Gene Regulatory Network Module

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful evo-devo research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools tailored for comparative and functional studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Evo-Devo Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Composition / Type | Primary Function in Evo-Devo |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Species Antibodies | Affinity-purified polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies against conserved protein epitopes. | Immunodetection of protein expression in non-traditional model organisms where species-specific reagents are unavailable. |

| Degenerate PCR Primers | Oligonucleotide pools designed from alignments of conserved protein domains (e.g., homeobox). | Isolation of orthologous genes from novel species for phylogenetic and expression analysis. |

| Transposon-Based Vectors | Plasmid DNA containing transposable elements (e.g., Minos, PiggyBac). | Stable germline transformation for transgenesis and gene trapping in emerging model organisms [24]. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Stable, antisense oligonucleotides that block mRNA translation or splicing. | Transient gene knockdown in organisms where genetic mutants are not yet available. |

| Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization Kits | Optimized buffers and enzymes for colorimetric RNA detection. | Spatial mapping of gene expression patterns in embryos across diverse species, a cornerstone of comparative evo-devo. |

| Parental RNAi Reagents | dsRNA synthesized in vitro targeting specific maternal or zygotic transcripts. | Functional analysis of genes required for early embryonic patterning, as demonstrated in Nasonia [24]. |

Advanced Quantitative Modeling in Evo-Devo

Modern evo-devo increasingly integrates mathematical modeling to formalize hypotheses and generate testable predictions. A recent framework modeling evo-devo dynamics of hominin brain size demonstrates this approach. The model mechanistically replicates the evolution of adult brain and body sizes across seven hominin species by incorporating developmental constraints and genetic correlations, rather than relying solely on direct selection for larger brains [27].

The model's key equations describe the developmental dynamics of tissue growth:

- Energy Allocation:

dB/dt = E * r_B(t) - c_B * B(Brain tissue growth) - Body Growth:

dS/dt = E * r_S(t) - c_S * S(Somatic tissue growth) - Fertility Investment:

dR/dt = E * r_R(t)(Reproductive tissue/follicle growth)

Where B, S, and R are brain, somatic, and reproductive tissue sizes; E is metabolizable energy; r_i(t) are genotype-dependent allocation traits; and c_i are maintenance costs [27]. This modeling shows that hominin brain expansion can be an indirect result of selection on other traits (e.g., follicle count), with the correlation generated by developmental processes under specific ecological and cultural conditions [27].

The Evo-Devo Toolkit: Methodological Advances and Research Applications Across Species

The selection of appropriate model organisms is a cornerstone of biological research, enabling scientists to uncover fundamental principles of development, disease, and evolutionary processes. In the specific context of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), this practice takes on a distinct character, representing a unique synthesis of model system strategies from developmental biology and comparative approaches from evolutionary biology [2]. This article outlines the key criteria and emerging methodologies for selecting new model organisms, providing a practical framework for researchers engaged in expanding the experimental pantheon to answer novel scientific questions.

Key Criteria for Model Organism Selection

Foundational Biological and Practical Criteria

When evaluating a potential new model organism, researchers must balance a set of core biological and practical considerations. These criteria ensure the organism is both scientifically valuable and experimentally tractable.

The table below summarizes the primary factors influencing model organism selection:

| Criterion | Description | Examples/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Position | Occupies a key evolutionary position to study trait origins or conservation [2] [3]. | Starlet sea anemone for bilaterian symmetry; leeches for bilaterian segmentation [2]. |

| Genetic Tractability | Amenable to genetic manipulation and genomic analysis [28]. | Availability of CRISPR-Cas9, RNAi, transgenic methods [29]. |

| Experimental Accessibility | Allows for observation and manipulation during development [28]. | Transparent embryos (zebrafish), external development (frogs), simple body plans (placozoans) [3] [28]. |

| Life History Traits | Possesses practical characteristics for laboratory maintenance [28]. | Short generation time, high fecundity, ease of rearing in a lab setting [28]. |

| Defined Genetic Background | Availability of a sequenced genome and established genetic tools [28]. | Well-annotated genome, inbred strains, known genetic markers. |

Advanced and Evo-Devo Specific Considerations

Beyond the foundational criteria, several advanced considerations are particularly critical for evolutionary developmental biology studies.

- Phenotypic Novelty: Organisms exhibiting extreme or novel adaptations can reveal how developmental processes are altered to generate evolutionary innovation. For instance, snakes serve as powerful models for understanding the evolution of limb loss and axial patterning [2].

- Conservation of Biological Context: Moving beyond simple sequence similarity, a modern approach assesses functional conservation of protein networks, structures, and pathways. A data-driven framework can sometimes identify non-intuitive models; for example, certain unicellular algae have been suggested as relevant models for studying the conserved biological processes underlying spinal muscular atrophy [30].

- Strength of Stabilizing Selection: Quantitative models, such as the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process, can be applied to expression data to quantify the evolutionary constraint on a gene's expression level across species. This helps identify tissues where a gene's function is most critical and can even detect deleterious expression levels in disease [20].

A Data-Driven Selection Framework: Protocol and Workflow

The traditional reliance on historical precedent or intuition for model selection is being supplanted by more rigorous, data-driven frameworks. The following protocol outlines key steps for this process.

Protocol: A Data-Driven Pipeline for Organism Selection

Objective: To systematically identify the most suitable organism for studying a specific human biological process or disease.

Materials:

- Genomic and transcriptomic data from a diverse set of species.

- Phylogenetic analysis software (e.g., PhyloXML, PAUP).

- Protein structure prediction tools (e.g., AlphaFold2).

- Computational resources for comparative genomics.

Workflow Steps:

- Define Research Problem: Clearly articulate the biological process or disease pathway of interest. Identify key genes and proteins involved.