Beyond the Model System: Integrating Comparative and Mechanistic Approaches in Modern Biology and Drug Discovery

This article explores the foundational dichotomy and emerging synthesis between the comparative and mechanistic approaches in biology.

Beyond the Model System: Integrating Comparative and Mechanistic Approaches in Modern Biology and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the foundational dichotomy and emerging synthesis between the comparative and mechanistic approaches in biology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it delves into the historical and philosophical underpinnings of both methods, showcasing their distinct applications from basic research to therapeutic development. We provide a practical framework for selecting and optimizing each approach, address common pitfalls like the 'essentialist trap' of over-relying on model organisms, and outline rigorous validation strategies. By synthesizing key insights, the article advocates for an integrated methodology that leverages the strengths of both perspectives to drive robust scientific discovery and enhance the translational pipeline in biomedicine.

Philosophical Roots and Core Principles: Defining the Two Biological Worldviews

The mechanistic paradigm in biology is a way of thinking that views living organisms as complex machines whose functions can be understood by studying their component parts and the physical and chemical interactions between them [1]. This perspective, rooted in Cartesian dualism and Newtonian physics, has profoundly shaped modern biological research, suggesting that biological systems operate through predictable, cause-and-effect relationships [2]. The application of this paradigm to the study of development, known as "Entwicklungsmechanik" or developmental mechanics, emerged in the late 19th century and represented a pivotal shift from purely descriptive embryology to experimental analysis of developmental processes [3]. This transformative approach sought to explain the mysteries of development not through vital forces or abstract principles, but through identifiable, testable mechanisms.

The subsequent rise of model organisms represents the logical extension of this mechanistic worldview. These non-human species, extensively studied with the expectation that discoveries will provide insight into the workings of other organisms, became the practical instruments through which the mechanistic paradigm could be implemented in laboratory settings [4] [5]. The foundational premise is that despite tremendous morphological and physiological diversity, all living organisms share common metabolic, developmental, and genetic pathways conserved through evolution [4]. This article will compare the performance of different model organisms within the context of the mechanistic approach, contrasting it with the comparative method in biology, and provide supporting experimental data that illustrates their respective utilities and limitations in biomedical research.

The Foundation: Entwicklungsmechanik and its Legacy

The concept of Entwicklungsmechanik (developmental mechanics) established a new research program that focused on the "mechanics" of development, emphasizing physicochemical contributions—mechanical, molecular, and otherwise—to understanding how organisms develop [3]. This approach stood in stark contrast to the predominantly descriptive and comparative morphological traditions that preceded it. Where comparative biology sought to understand patterns of diversity through historical relationships and homologies, Entwicklungsmechanik asked proximate questions about causal mechanisms: What physical forces shape the embryo? What chemical signals coordinate cellular differentiation?

This mechanistic approach gained considerable momentum throughout the 20th century with the growth of disciplines such as physiology and genetics, and particularly with the rise of molecular biology from the 1950s onward [3]. The analysis of mutants and the identification of affected genes, along with the mapping of epistatic relationships, provided developmental biology with powerful tools for deciphering the minute details involved in the generation of body structures, from cellular processes to three-dimensional patterning [3]. The enthusiasm for this approach eventually led to what some scholars have termed an "essentialist trap" in developmental biology—the assumption that mechanisms discovered in a handful of laboratory models universally represent developmental processes across diverse species [3].

Model Organisms as Mechanistic Platforms

The Concept and Selection Criteria

Model organisms are defined as non-human species that are extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in them will provide insight into the workings of other organisms [4]. They are widely used to research human disease when human experimentation would be unfeasible or unethical [4] [5]. The selection of model organisms is not random; they are typically chosen based on practical considerations that facilitate mechanistic investigation under controlled laboratory conditions.

Key criteria for model organism selection include:

- Short generation time to observe multiple life cycles and genetic inheritance

- Tractability to genetic manipulation through inbred strains, stem cell lines, and transformation methods

- Compact genome with low proportion of junk DNA to facilitate sequencing

- Specialized living requirements that are easily replicated in laboratory settings

- Economic considerations related to cost-effective maintenance [4] [5]

As one analysis notes, "The use of (a few) models has led to a narrow view of the processes that occur at a higher level (supra-cellular) in animals, since these processes tend to be quite diverse and thus cannot be well-represented by the idiosyncrasies of any specific animal model" [3]. This limitation represents a significant challenge when applying the mechanistic paradigm to broader biological questions.

Historical Trajectory of Key Model Organisms

The use of animals in research dates back to ancient Greece, with Aristotle and Erasistratus among the first to perform experiments on living animals [4]. The 18th and 19th centuries saw landmark experiments, including Antoine Lavoisier's use of guinea pigs in calorimeters to prove respiration was a form of combustion, and Louis Pasteur's demonstration of the germ theory of disease using anthrax in sheep [4].

The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster emerged as one of the first, and for some time the most widely used, model organisms in the early 20th century [4]. Thomas Hunt Morgan's work between 1910 and 1927 identified chromosomes as the vector of inheritance for genes, discoveries that "helped transform biology into an experimental science" [4]. During this same period, William Ernest Castle's laboratory, in collaboration with Abbie Lathrop, began systematic generation of inbred mouse strains, establishing Mus musculus as another foundational model organism [4].

The late 20th century saw the introduction of new model organisms, including the zebrafish Danio rerio around 1970, which was developed through three recognizable stages: choice and stabilization of the organism; accumulation of mutant strains and genomic data; and the use of the organism to construct models of mechanisms [6]. Similar trajectories occurred with other organisms like C. elegans, while established models like Drosophila were redesigned for new experimental approaches [6].

Table 1: Historical Development of Key Model Organisms

| Organism | Introduction Period | Key Historical Figures | Major Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila melanogaster (Fruit fly) | 1910-1927 | Thomas Hunt Morgan | Chromosomal theory of inheritance, gene mapping |

| Mus musculus (Mouse) | Early 1900s | William Ernest Castle, Abbie Lathrop | Mammalian genetics, inbred strains, immunology |

| Danio rerio (Zebrafish) | circa 1970 | George Streisinger | Vertebrate development, genetic screens |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Mouse-ear cress) | 1943 | Friedrich Laibach | Plant genetics, molecular biology |

Comparative Analysis of Model Organisms in Mechanistic Research

Representative Model Organisms and Their Applications

Different model organisms offer distinct advantages for investigating specific biological questions within the mechanistic paradigm. The following table summarizes key characteristics and applications of major model organisms:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Major Model Organisms in Mechanistic Research

| Organism | Life Cycle | Genetic Tools | Key Advantages | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Mouse-ear cress) | 4-6 weeks | Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, T-DNA insertion mutants | Small genome, small size, high seed production | Plant genetics, molecular biology, development, physiology |

| Drosophila melanogaster (Fruit fly) | 8-10 days | P-element transgenesis, GAL4/UAS system, RNAi | Complex nervous system, well-characterized development, low cost | Human development, neurobiology, genetics, behavior |

| Danio rerio (Zebrafish) | 3 months | CRISPR-Cas9, morpholinos, transgenesis | Transparent embryos, vertebrate biology, high fecundity | Vertebrate development, organogenesis, toxicology, gene function |

| Mus musculus (Laboratory mouse) | 10-12 weeks | CRISPR-Cas9, embryonic stem cells, transgenesis | Mammalian physiology, similar to human disease | Human disease models, immunology, cancer, therapeutics |

Quantitative Experimental Data from Model Organism Research

The utility of model organisms in the mechanistic paradigm is demonstrated by their extensive contributions to understanding disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic interventions. The following table summarizes key experimental findings and their biomedical implications:

Table 3: Key Experimental Findings and Biomedical Applications from Model Organism Research

| Organism | Experimental Approach | Key Finding | Human Disease Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | Targeted mutagenesis using CRISPR-Cas9 [7] | Zebrafish mutants exhibited stroke symptoms, confirming gene role | Stroke and vascular inflammation in children |

| Fruit flies | Genetic mapping and phenotypic characterization [4] [5] | Genes are physical features of chromosomes | Fundamental genetic principles |

| Mouse | Knockout Mouse Phenotyping Program (KOMP2) [7] | Systematic characterization of null mutations in every mouse gene | Understanding gene function in mammalian systems |

| Maize | Cytogenetic studies [5] | Discovery of transposons ("jumping genes") | Genome evolution, mutation mechanisms |

The Mechanistic versus Comparative Approach in Biology

The comparative method in biology represents a fundamentally different approach to understanding biological systems. Rather than seeking proximate, mechanistic explanations through experimental manipulation, it focuses on historical products and evolutionary patterns [3]. Organisms and clades are defined by their uniqueness, and their comparison provides insight into patterns of diversification [3]. As one researcher notes, "Process analysis gives us information on proximal causes while patterns inform us of ultimate (evolutionary) causes/mechanisms" [3].

The tension between these approaches reflects a deeper philosophical divide in biological research. The mechanistic approach, with its emphasis on controlled experimentation and predictable outcomes, aligns with a positivist epistemology that favors quantitative methods and empirical evidence obtained through sensory experience [2]. In contrast, the comparative approach embraces the historical contingency and uniqueness of biological systems, recognizing that "processes such as development can be interrogated through external intervention (manipulation of the system); but not so patterns: patterns are mental (re)constructions" [3].

This distinction has profound implications for how biological research is conducted and interpreted. As one analysis observes, "It is a sociological truth that we tend to think that the analysis of the mechanistic particularities of any biological process somehow represents a superior form of analysis; but this only reflects a particular (cultural) bias in our view of what it means to understand nature" [3].

Experimental Protocols in Mechanistic Research

Large-Scale Mutagenesis Screens in Zebrafish

The "Big Screen" in zebrafish research exemplifies the application of the mechanistic paradigm to identify genes essential for development [6]. This coordinated, large-scale mutagenesis approach involved:

Mutagenesis: Male zebrafish were treated with ethylnitrosourea (ENU), a chemical mutagen that introduces random point mutations throughout the genome.

Breeding Scheme: Treated males were crossed with wild-type females to establish F1 families. These F1 fish, each carrying different heterozygous mutations, were then intercrossed to produce homozygous mutant offspring in the F2 generation.

Phenotypic Screening: F2 embryos were systematically examined for developmental abnormalities at specific stages using morphological criteria. This identified mutants with defects in various processes including organogenesis, patterning, and physiology.

Genetic Mapping: Mutants of interest were outcrossed to polymorphic strains to map the chromosomal location of the causative mutation.

Gene Identification: Positional cloning techniques were used to identify the specific genes responsible for the observed phenotypes [6].

This approach led to the identification of numerous genes critical for vertebrate development, including the one-eyed pinhead (oep) gene, which was found to be essential for nodal signaling and establishment of the embryonic axis [6].

CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Engineering in Model Organisms

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized mechanistic research in model organisms by enabling precise genome manipulations:

Guide RNA Design: Sequence-specific guide RNAs (gRNAs) are designed to target the gene of interest.

Delivery System: gRNAs and Cas9 nuclease are introduced into the organism via microinjection (in embryos), viral vectors, or other transformation methods.

Genetic Modification: The Cas9 nuclease creates double-strand breaks at the target site, which are repaired through non-homologous end joining (introducing insertions/deletions) or homology-directed repair (for precise edits).

Phenotypic Characterization: Mutant organisms are systematically analyzed for morphological, physiological, or behavioral changes compared to wild-type controls.

Validation: The specific genetic lesion is confirmed through sequencing, and its correlation with the phenotype is verified through rescue experiments or independent alleles [7].

This approach has been successfully applied in zebrafish, mice, fruit flies, and other model organisms to model human diseases and investigate gene function [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Mechanistic Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Their Applications in Mechanistic Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Composition/Type | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Cas9 nuclease + guide RNA | Targeted genome editing | Creating specific disease models in various organisms [7] |

| Ethylnitrosourea (ENU) | Chemical mutagen | Induces random point mutations | Large-scale mutagenesis screens [6] |

| Morpholinos | Modified oligonucleotides | Transient gene knockdown | Assessing gene function during development |

| Antibodies | Immunoglobulin molecules | Protein detection and localization | Spatial and temporal expression pattern analysis |

| Mutant Strain Collections | Curated genetic stocks | Repository of genetic variants | Phenotypic analysis of specific mutations [6] |

Visualization of Mechanistic Research Workflows

The Progression from Model Organism to Therapeutic Insight

Diagram 1: From Model Organisms to Therapeutic Insight

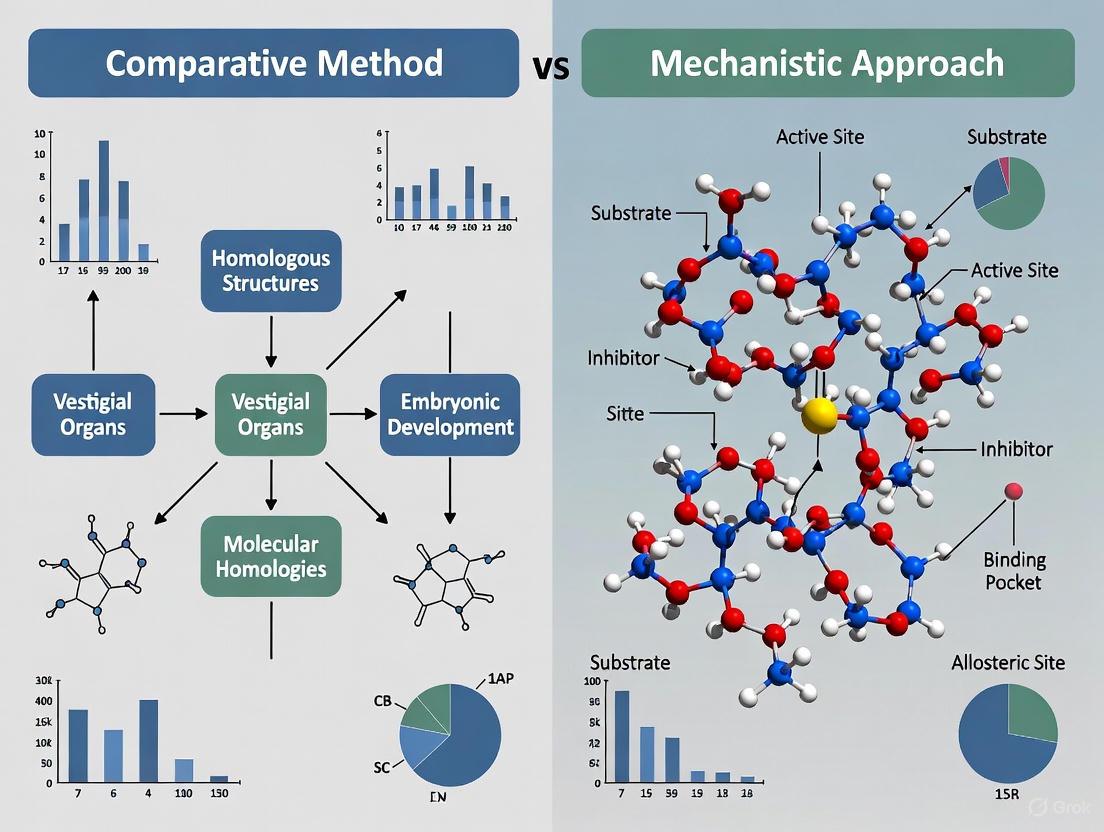

Comparative vs. Mechanistic Approaches in Biology

Diagram 2: Two Approaches to Biological Research

The mechanistic paradigm, from its origins in Entwicklungsmechanik to its contemporary implementation through model organisms, has proven enormously powerful in elucidating the proximate causes of biological phenomena [8] [3]. The strategic use of model organisms has enabled researchers to dissect complex biological processes into manageable, experimentally tractable components, leading to fundamental discoveries about gene function, developmental mechanisms, and disease pathogenesis [4] [5] [7].

However, the limitations of this approach are increasingly apparent. The focus on a handful of laboratory models has created a narrow view of biological diversity, and the assumption that mechanisms discovered in these systems universally apply across taxa represents what some term an "essentialist trap" [3]. The comparative method offers an essential complementary approach by placing biological mechanisms in an evolutionary context, testing their generality across diverse species, and appreciating the uniqueness of different organisms [3] [9].

Future progress in biological research will likely require a more integrated approach that combines the methodological rigor of the mechanistic paradigm with the evolutionary perspective of the comparative method. Such integration would leverage the strengths of both approaches: the ability to establish causal mechanisms through experimental manipulation and the capacity to understand their evolutionary significance through comparative analysis. As technological advances such as artificial intelligence make a wider range of organisms accessible to detailed mechanistic study [5], this synthesis may become increasingly feasible, potentially leading to a more comprehensive understanding of biological systems that transcends the limitations of both approaches alone.

Evolutionary biology has long been guided by two distinct yet complementary methodological paradigms: the comparative tradition, which discerns evolutionary history through patterns of diversity, and the mechanistic approach, which seeks proximal causes through experimental intervention. This guide objectively compares these research frameworks, detailing their philosophical underpinnings, technical requirements, and applications in modern biological research, including drug development. We provide structured comparisons of their capabilities, experimental protocols, and outputs, supported by quantitative data and visualizations of research workflows.

A significant methodological schism characterized 20th-century biology, with evolutionary and molecular disciplines developing largely separate cultures and modes of inference [10]. The comparative tradition emphasizes the analysis of variation across individuals, populations, and taxa as the fundamental phenomenon requiring explanation. It draws historical inferences from patterns detected in sequences, allele frequencies, and phenotypes, offering a realistic view of biological systems in their natural and historical contexts [10] [3]. In contrast, the mechanistic approach employs controlled experiments to isolate factors and establish causal links, setting aside natural complexity to achieve high-standard, evidence-based inferences [10] [3].

Today, a "functional synthesis" bridges this divide, combining statistical analyses of gene sequences with manipulative molecular experiments to reveal how historical mutations altered biochemical processes and produced novel phenotypes [10] [11]. This synthesis leverages the strengths of both approaches while compensating for their respective limitations.

Framework Comparison: Comparative vs. Mechanistic Approaches

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each research approach and their modern synthesis.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Biological Research Approaches

| Aspect | Comparative Approach | Mechanistic Approach | Functional Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Patterns of diversification; historical relationships [3] | Physicochemical "mechanics" of processes; proximal causes [3] | Mechanism and history of phenotypic evolution [10] |

| Core Strength | Historical realism; focus on natural variation [10] | Strong causal inference via controlled experiments [10] | Decisive insights into adaptation's mechanistic basis [10] |

| Inference Basis | Statistical associations from surveys and sequences [10] | Isolation of variables with all else held constant [10] | Corroboration of statistical patterns with experimental tests [10] |

| View of Organisms | Historical products defined by uniqueness [3] | Model systems representing general processes [3] | Historical entities amenable to reductionist analysis [10] |

| Typical Data | Phylogenies, fossil records, morphological homologies [3] | Molecular pathways, mutant phenotypes, reaction rates [10] | Resurrected protein functions, fitness effects of historical mutations [10] |

| Key Limitation | Associations do not reliably indicate causality [10] | Limited generalizability due to reduced complexity [10] | Technically challenging; requires cross-disciplinary expertise [10] |

The Functional Synthesis: A Hybrid Workflow

The integrated functional synthesis approach follows a defined pathway, leveraging the strengths of both comparative and mechanistic methods.

Diagram 1: Functional synthesis workflow combining comparative and mechanistic methods.

Experimental Protocols in the Functional Synthesis

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction and Resurrection

This protocol tests evolutionary hypotheses by experimentally characterizing the functions of ancestral proteins [10] [11].

Detailed Methodology:

- Sequence Alignment and Curation: Collect and align homologous gene sequences from diverse extant species. Verify alignment accuracy and identify conserved regions.

- Phylogenetic Tree Inference: Reconstruct the evolutionary relationships among sequences using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods.

- Ancestral State Reconstruction: Infer the most probable protein sequences at ancestral nodes of the phylogenetic tree using probabilistic models of sequence evolution.

- Gene Synthesis: Physically synthesize the DNA sequences encoding the inferred ancestral proteins, with codon optimization for the intended expression system (e.g., E. coli).

- Protein Expression and Purification: Clone synthesized genes into expression vectors, express in host cells, and purify proteins using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag purification).

- Functional Characterization: Perform biochemical assays to determine kinetic parameters (e.g., Km, kcat), ligand binding affinity, stability, or other relevant functions. Compare activities between ancestral and modern proteins.

Historical Mutagenesis and Functional Tests

This protocol identifies the specific mutations responsible for functional shifts and characterizes their effects [10].

Detailed Methodology:

- Identify Historical Mutations: Using comparative sequence analysis, identify amino acid replacements that occurred on specific lineages during a period of putative adaptive evolution.

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Introduce individual or combined historical mutations into the background of a resurrected ancestral protein or a modern protein.

- In Vitro Functional Assays: Measure the functional consequences of each mutation. For example, in the study of insecticide resistance:

- Structural Analysis (Optional): Model protein structures based on related crystallographic data to visualize how mutations alter active site geometry and catalytic mechanisms [10].

- In Vivo Verification (Ideal): In suitable model organisms, use transgenesis to introduce ancestral and modern alleles and measure their effects on whole-organism phenotypes and fitness in controlled environments [10].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following tools and reagents are fundamental for conducting research in the functional synthesis.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Evolutionary-Mechanistic Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Synthesis Services | Physically creates DNA sequences inferred for ancestral genes, enabling their resurrection [10]. | Ancestral sequence reconstruction |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introduces specific historical amino acid changes into plasmid DNA for functional testing [10]. | Historical mutagenesis |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Produces large quantities of ancestral/modern proteins for purification (e.g., E. coli, yeast) [10]. | Protein biochemistry |

| Affinity Chromatography Resins | Purifies recombinant proteins from cell lysates based on specific tags (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins). | Protein biochemistry |

| Spectrophotometric Assay Kits | Measures enzyme kinetic parameters (e.g., Vmax, Km) by tracking substrate depletion or product formation. | Functional characterization |

| Model Organism Strains | Provides a genetically tractable system (e.g., fruit flies, mice) for testing phenotypic effects of alleles in vivo [10]. | Transgenic phenotyping |

Case Study: Evolution of Insecticide Resistance

A seminal study on diazinon resistance in the sheep blowfly Lucilia cuprina exemplifies the functional synthesis [10].

Table 3: Quantitative Data from Insecticide Resistance Study

| Measurement | Susceptible E3 Allele | Resistant E3 Allele | Gly135Asp Mutant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphate Hydrolysis Rate | Very low/undetectable [10] | High [10] | Confered novel capacity for high-rate hydrolysis [10] |

| Key Active Site Residue | Glycine (Gly135) [10] | Aspartate (Asp135) [10] | Single-site determinant of novel function |

| Functional Effect of Reverse Mutation (Asp135Gly) | Not applicable | Not applicable | Produced susceptible phenotype [10] |

Experimental Workflow:

- Comparative Analysis: Researchers compared E3 esterase sequences from resistant and susceptible fly populations, identifying five amino acid differences [10].

- Chimeric Protein Construction: Created and expressed chimeric enzymes to localize the functional source of resistance [10].

- Site-Specific Mutagenesis: Pinpointed the Gly135Asp switch as conferring the novel capacity to hydrolyze organophosphates. The reverse mutation (Asp135Gly) reverted the enzyme to a susceptible phenotype [10].

- Structural Modeling: Modeled the active site on a related esterase structure, revealing the mechanistic basis: the aspartate's side-chain carboxylate activates a water molecule, enabling hydrolysis of the enzyme-inhibitor complex [10].

This case demonstrates how the functional synthesis can move from statistical association to a decisive, mechanistic understanding of adaptation.

Implications for Drug Development

The comparative and mechanistic approaches also underpin critical methodologies in pharmaceutical research, particularly in regulatory science.

Table 4: Application of Comparative and Mechanistic Thinking in Drug Development

| Aspect | 505(b)(1) Pathway (Novel Drug) | 505(b)(2) Pathway (Modified Drug) |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Analogy | Largely mechanistic: requires full, de novo characterization of the agent's action [12]. | Largely comparative: relies on bridging and comparison to an already approved reference drug [12]. |

| Clinical Pharmacology Requirement | Full assessment of MOA, ADME, PK/PD, and safety in specialized populations [12]. | Leverages data from Listed Drugs; focuses on establishing bioequivalence or justifying differences [12]. |

| Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) | Used to predict human dose response, refine dosing regimens, and support waivers for specific clinical studies (e.g., TQT) [12]. | Used to establish a scientific bridge to the reference drug, especially for complex changes (e.g., formulation) [12]. |

The power of the comparative approach in drug development is exemplified by the bioequivalence concept for generic drugs, where demonstrating comparable pharmacokinetic (PK) exposure to a reference drug serves as a surrogate for re-establishing clinical efficacy and safety, thereby avoiding redundant clinical trials [13]. Furthermore, clinical pharmacology employs PK and pharmacodynamic (PD) data as comparative tools throughout development for dose-finding, assessing the impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, and supporting biomarker development [13].

In biological research, the distinction between proximate and ultimate causation represents a fundamental epistemological divide that shapes how scientists investigate and interpret biological phenomena. This dichotomy, famously articulated by Ernst Mayr, separates questions of immediate function (how) from questions of evolutionary origin and adaptive significance (why) [14]. Proximate causes explain biological function in terms of immediate physiological or environmental factors, while ultimate explanations address traits in terms of evolutionary forces that have acted upon them throughout history [15]. This framework creates two complementary but distinct approaches to biological investigation: the mechanistic approach, which focuses on decoding immediate operational processes, and the comparative method, which seeks to reconstruct historical evolutionary pathways [3]. Understanding this epistemological divide is essential for researchers navigating the complexities of modern biological research, particularly in fields like drug development where both immediate mechanism and evolutionary context inform therapeutic strategies.

Conceptual Framework: Definitions and Philosophical Foundations

Proximate Causation: The Mechanistic Approach

Proximate causation refers to the immediate, mechanical factors that underlie biological function. This approach investigates the biochemical, physiological, and developmental processes that operate within an organism's lifetime. Proximate explanations focus on how structures and behaviors function through molecular interactions, cellular processes, and organ system functions [15]. In scientific practice, this represents the mechanistic approach, which employs reductionist methods to isolate and characterize biological components. For example, when studying a disease mechanism, a proximate approach would investigate the specific molecular pathways disrupted in the condition, the cellular responses to this disruption, and the physiological consequences that manifest as symptoms [3]. The mechanistic approach dominates fields like molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology, where controlled experimentation allows researchers to establish causal links between factors and their effects by holding other variables constant [10].

Ultimate Explanations: The Evolutionary Approach

Ultimate causation explains why traits exist by reference to their evolutionary history and adaptive significance. This approach investigates the selective pressures, phylogenetic constraints, and historical contingencies that have shaped traits over generational time [14]. Ultimate explanations address why certain characteristics have evolved and persisted in populations, typically through comparative analysis across species or populations [15]. This epistemological stance aligns with the comparative method in biology, which uses patterns of variation across taxa to infer evolutionary processes [3]. For instance, when investigating antibiotic resistance, an ultimate perspective would examine the evolutionary pressures that favored resistant strains, the genetic variation that made resistance possible, and the historical emergence and spread of resistance mechanisms in bacterial populations [10]. The comparative method is central to evolutionary biology, ecology, and systematics, where statistical analyses of variation reveal patterns that illuminate evolutionary processes.

Table 1: Fundamental Contrasts Between Proximate and Ultimate Approaches

| Aspect | Proximate/Mechanistic Approach | Ultimate/Comparative Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | How does it work? | Why did it evolve? |

| Timescale | Immediate (organism's lifetime) | Historical (evolutionary time) |

| Analytical Focus | Internal processes & mechanisms | Evolutionary patterns & selective history |

| Primary Methods | Controlled experimentation, molecular analysis | Comparative analysis, phylogenetic reconstruction |

| Standards of Evidence | Causal demonstration via isolation of variables | Statistical inference from patterns of variation |

| Explanatory Scope | Universal mechanisms across taxa | Historical trajectories specific to lineages |

Methodological Applications: Experimental Paradigms and Workflows

The Mechanistic Research Program: Establishing Proximate Causality

The mechanistic approach to establishing proximate causation follows a defined workflow that emphasizes controlled experimentation and molecular manipulation. This research program typically begins with phenotype characterization, where a biological phenomenon of interest is carefully described and quantified. Researchers then proceed to hypothesis generation about potential molecular mechanisms, often based on prior knowledge of similar systems or preliminary data. The core of the mechanistic approach involves experimental manipulation, where specific components of the system are selectively altered through genetic, pharmacological, or environmental interventions [10]. This is followed by functional assessment to determine the effects of these manipulations on the phenotype of interest.

A powerful illustration of this approach comes from studies of insecticide resistance in the sheep blowfly Lucilia cuprina [10]. Researchers investigating resistance to diazinon employed a systematic mechanistic workflow:

- Statistical association of resistance with specific alleles at the E3 esterase locus

- Sequence comparison between resistant and susceptible populations, identifying five amino acid differences

- Chimeric protein construction to test functional contributions of different protein regions

- Site-directed mutagenesis to isolate the specific mutation responsible (Gly135Asp)

- Structural modeling to understand the mechanistic basis for the functional change

- Functional assays confirming that the Asp135 replacement enabled organophosphate hydrolysis

This workflow established that a single amino acid change conferred resistance by altering the enzyme's active site, allowing it to hydrolyze the insecticide rather than being inhibited by it [10]. The mechanistic approach thus moved from correlation to causation by systematically testing and verifying the molecular basis of the phenotype.

The Comparative Research Program: Inferring Ultimate Causality

The comparative method for establishing ultimate explanations follows a different epistemological pathway focused on pattern detection and historical inference. This approach typically begins with character documentation across multiple taxa or populations, identifying variations in the trait of interest. Researchers then employ phylogenetic reconstruction to establish evolutionary relationships among the studied entities. The core analytical phase involves mapping character evolution onto the phylogenetic framework to infer historical patterns of trait origin, modification, and loss. Finally, researchers test evolutionary hypotheses by examining correlations between trait variations and ecological factors or by detecting statistical signatures of selection in genetic data [3].

A modern extension of the comparative approach integrates molecular biology with evolutionary analysis in what has been termed the "functional synthesis" [10]. This integrated workflow includes:

- Phylogenetic analysis to identify lineages where functional changes occurred

- Ancestral sequence reconstruction to infer historical genetic states

- Gene resurrection to express and characterize ancestral proteins

- Site-directed mutagenesis of historical mutations into ancestral backgrounds

- Functional characterization of effects on molecular phenotype

- Fitness assessment through competition experiments or other measures

This approach allows researchers to move beyond statistical inference to experimental verification of evolutionary hypotheses, effectively bridging the proximate-ultimate divide [10].

Experimental Data and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Research Approaches

The epistemological differences between proximate and ultimate approaches manifest in distinctive methodological preferences, analytical techniques, and interpretive frameworks. These differences can be quantified across multiple dimensions of scientific practice, reflecting deeper philosophical commitments about what constitutes biological explanation.

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of Research Approaches in Biology

| Dimension | Mechanistic Approach | Comparative Method | Functional Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Data | Experimental measurements from controlled manipulations | Patterns of variation across taxa/populations | Combined sequence patterns & experimental measurements |

| Model Systems | Few, highly tractable "model organisms" | Diverse representatives of clades of interest | Phylogenetically informed selection of study systems |

| Causal Inference | Direct demonstration through intervention | Statistical inference from correlated variation | Experimental testing of evolutionary hypotheses |

| Analytical Scope | Isolated components & pathways | Broad taxonomic & historical patterns | Historical mutations & their functional consequences |

| Strength of Inference | High internal validity through variable control | Identification of natural patterns & correlations | Combined historical & experimental verification |

| Generalizability | Potentially limited by system-specific factors | Broad evolutionary patterns but correlational | Mechanistic generalizability with historical context |

Case Study: Molecular Evolution of Hormone Signaling

Research on the evolution of hormone-receptor interactions provides compelling quantitative data illustrating both the distinct contributions and complementary nature of proximate and ultimate approaches. Studies of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) evolution have employed both mechanistic and comparative methods to reconstruct the historical path by which this important signaling system acquired its modern specificity.

In one landmark study, researchers combined phylogenetic analysis of vertebrate GR sequences with experimental characterization of resurrected ancestral proteins [10]. This integrated approach revealed that a historical change in receptor specificity involved multiple permissive mutations that initially had no effect on function but later enabled the specificity switch through additional mutations. The quantitative data from functional assays demonstrated how historical mutations progressively shifted receptor specificity:

- Ancstral GR: Broad sensitivity to multiple steroid hormones

- Intermediate forms: Gradual reduction in sensitivity to certain ligands

- Modern GR: High specificity for cortisol over other steroids

This case study exemplifies how the integration of proximate and ultimate approaches can yield insights inaccessible to either approach alone. The comparative method identified the historical sequence of changes, while mechanistic analyses revealed the functional consequences of each step in the evolutionary pathway.

Table 3: Experimental Data from GR Evolution Study

| Receptor Form | Cortisol Activation (EC50) | Aldosterone Activation (EC50) | Specificity Ratio | Key Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestral GR | 0.5 nM | 1.2 nM | 2.4:1 | Baseline |

| Intermediate 1 | 0.6 nM | 5.8 nM | 9.7:1 | S106P, L111Q |

| Intermediate 2 | 0.7 nM | 28.4 nM | 40.6:1 | L29M, F98I |

| Modern GR | 1.0 nM | >1000 nM | >1000:1 | C127D, S212A |

Essential Research Tools and Reagent Solutions

The practical implementation of both proximate and ultimate research programs requires specialized methodological tools and reagents. These resources enable the distinctive forms of experimentation and analysis characteristic of each approach.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Proximate and Ultimate Approaches

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Site-directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introduce specific historical or mechanistic mutations into genes | Both approaches |

| Protein Expression Systems | Produce ancestral or modified proteins for functional characterization | Both approaches |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software | Reconstruct evolutionary relationships and ancestral sequences | Ultimate approach |

| High-throughput Sequencers | Generate genetic data from multiple taxa/populations for comparative analysis | Ultimate approach |

| Crystallography Platforms | Determine three-dimensional protein structures to understand mechanistic basis of function | Proximate approach |

| Functional Assay Reagents | Measure biochemical activities, binding affinities, and catalytic properties | Proximate approach |

| Model Organism Resources | Genetically tractable systems for experimental manipulation | Proximate approach |

| Comparative Collections | Biodiversity specimens representing taxonomic and evolutionary diversity | Ultimate approach |

For the integrated "functional synthesis" approach, researchers particularly rely on tools that bridge evolutionary and experimental methods. Gene synthesis services enable the physical resurrection of ancestral sequences inferred from phylogenetic analyses. Directed evolution platforms allow experimental testing of evolutionary hypotheses by generating alternative historical trajectories. High-throughput screening technologies facilitate the functional characterization of numerous historical variants, generating quantitative data that link historical mutations to functional consequences [10].

Discussion: Complementary Epistemologies in Biological Research

The distinction between proximate and ultimate causation represents more than a simple methodological divide; it reflects fundamentally different epistemologies for constructing biological knowledge. The mechanistic approach prioritizes causal demonstration through experimental control, offering strong evidence for how biological systems operate in the present. The comparative method emphasizes historical inference through pattern analysis, providing explanatory power for why biological systems have their current forms. Rather than representing competing paradigms, these approaches offer complementary strengths that address different aspects of biological explanation.

Contemporary biological research increasingly recognizes the limitations of pursuing either approach in isolation. The mechanistic focus on a few model organisms, while powerful for establishing general principles, risks what some have termed an "essentialist trap" – assuming that mechanisms discovered in one system apply universally across diverse taxa [3]. Conversely, the comparative method's reliance on statistical correlation leaves evolutionary hypotheses vulnerable to alternative explanations. The emerging functional synthesis represents a promising integration of these epistemologies, combining the historical inference of comparative biology with the causal demonstration of mechanistic approaches [10].

This epistemological integration has particular significance for applied fields like drug development. Understanding the proximate mechanisms of disease pathways enables targeted therapeutic interventions, while appreciation of ultimate evolutionary perspectives helps anticipate resistance mechanisms and understand species-specific differences in drug responses. The most robust biological explanations increasingly incorporate both perspectives – elucidating both how biological systems operate and why they have evolved to function as they do.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Two Faces of Biological Inquiry

- Defining the Approaches: Comparative Method vs. Mechanistic Approach

- The Essentialist Trap: How Model Systems Constrain Vision

- Case Study: Drug Development and the Rise of Integrative Strategies

- Visualizing the Scientific Workflow: From Trap to Synthesis

- Essential Research Reagent Solutions

- Conclusion: Embracing a Pluralistic Scientific Vision

In biological research, two powerful streams of inquiry coexist: the comparative method, which seeks to understand diversity and evolutionary history by analyzing patterns across species, and the mechanistic approach, which aims to elucidate the underlying physico-chemical processes that govern a specific biological system [3]. The mechanistic approach, fueled by molecular biology and genetics, has achieved monumental success, but this success has come with a significant, often unacknowledged, cost. An over-enthusiastic embrace of this methodology, particularly its reliance on a handful of standardized model organisms, has led the field into what some theorists identify as an "essentialist trap" [3]. This trap is a narrowed view of biological diversity, where the intricate, plastic, and varied developmental processes seen across the tree of life are unconsciously streamlined into the idiosyncrasies of a few lab-adapted models. This article will explore the contours of this trap, contrast the philosophical underpinnings of comparative and mechanistic biology, and demonstrate through contemporary examples from drug development how a synthesis of both approaches is essential for a truly robust and innovative scientific vision.

Defining the Approaches: Comparative Method vs. Mechanistic Approach

The comparative and mechanistic approaches are founded on distinct philosophical foundations and are geared toward answering different types of biological questions. The table below provides a structured comparison of these two paradigms.

Table 1: Core Differences Between the Comparative and Mechanistic Approaches

| Feature | Comparative Method | Mechanistic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Understand patterns of diversification, evolutionary history, and ultimate causes [3] | Decipher the proximate, physico-chemical causes and step-by-step processes underlying a biological phenomenon [3] |

| Unit of Analysis | Species, clades, and groups across phylogeny [3] | Entities and their activities within a specific system (e.g., a cell, organism) [3] |

| Core Concept | Homology (shared ancestry) [3] | Mechanism (organized entities and interactions) [16] |

| View of Nature | Dynamic, historical product of evolution [3] | System to be decomposed and analyzed [3] |

| Typical Output | Phylogenetic trees, identification of synapomorphies, predictive models of trait evolution [3] [17] | Pathway maps, molecular interaction networks, quantitative models of system behavior [16] |

| Inherent Strength | Captures the breadth and plasticity of biological diversity [3] | Provides deep, causal detail and enables targeted intervention [18] |

| Inherent Limitation | Often correlational; cannot alone establish proximate causality [17] | Risk of over-generalizing from a few model systems, leading to the "essentialist trap" [3] |

The Essentialist Trap: How Model Systems Constrain Vision

The "essentialist trap" arises from the pragmatic necessities of the mechanistic approach. To manage overwhelming complexity, researchers focus on model organisms like fruit flies, zebrafish, and lab mice. These models are selected for practical advantages such as short generation times, ease of manipulation, and robustness in a laboratory setting [3]. The trap is sprung when researchers unconsciously begin to treat these models not as convenient tools, but as perfect representatives of broader biological categories—the "essence" of a clade or process [3].

This has several consequences:

- A Narrowed View of Diversity: The development and physiology of a handful of models are taken as the general rule, while the fascinating and informative variations seen in other organisms are treated as exceptions or noise [3]. This obscures the true extent of nature's plasticity.

- Streamlined Systems: The use of inbred laboratory lines creates a streamlined, simplified version of a species, which reinforces typological thinking and departs from the polymorphic reality of wild populations [3].

- The Illusion of Understanding: There is a dangerous assumption that by thoroughly understanding a mechanism in one model system, we fundamentally "understand" that process in all of evolution, which is "further from the truth" as shown by studies revealing high developmental plasticity [3].

This trap is not merely a philosophical concern; it has tangible effects on scientific progress. In conservation biology, for instance, an over-reliance on general principles derived from a few well-studied species can lead to poor predictions and failed interventions for other species with different traits, such as habitat specialization or reproductive strategies [17]. The solution is not to abandon the mechanistic approach, but to consciously free it from the essentialist trap by re-integrating the comparative perspective.

Case Study: Drug Development and the Rise of Integrative Strategies

The field of drug development provides a powerful, real-world case study of the essentialist trap and the ongoing shift toward a more integrative, pluralistic approach. The traditional pipeline has been dominated by a mechanistic, model-centric philosophy, but its high failure rates and costs are a direct manifestation of the trap's limitations.

The Trap in Action: Limitations of Traditional Models

The preclinical stage of drug development has long relied on standardized in vitro models (e.g., specific cell lines) and in vivo animal models to predict human efficacy and toxicity. These models are the mechanistic equivalents of standard biological model organisms. However, they often fail to capture the complex heterogeneity of human diseases and populations. This oversimplification contributes to the staggering statistic that over 90% of drugs that enter clinical trials fail, often due to a lack of efficacy or unforeseen safety issues that were not apparent in the streamlined model systems [19]. This is the essentialist trap on an industrial scale: assuming that a response in a mouse model is the essential predictor of a response in humans.

Breaking the Trap: Comparative and Integrative MIDD

The field is now aggressively adopting Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), which uses a suite of quantitative approaches to break free from this narrow view. MIDD does not reject mechanistic models but enhances them with comparative and computational methods that account for complexity and diversity [20].

Table 2: Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) Tools to Overcome Mechanistic Limitations

| MIDD Tool | Description | How It Mitigates the Essentialist Trap |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Integrative modeling combining systems biology and pharmacology to simulate drug effects across multiple biological scales [20]. | Moves beyond a single model organism by integrating diverse human data (genomic, proteomic) to create a "virtual human" for testing. |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) | Mechanistic modeling that simulates the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of a drug based on human physiology [20]. | Allows for extrapolation between species (e.g., from rat to human) and across different human populations, acknowledging biological variation. |

| AI/ML for Target Discovery | Machine learning analyzes massive, diverse datasets (genomic, clinical) to identify novel drug targets and biomarkers [19] [21]. | Uses a comparative analysis of large populations to find patterns invisible in single-model studies, highlighting diversity rather than ignoring it. |

| Real-World Evidence (RWE) | Incorporates data from actual patient care (e.g., electronic health records) into regulatory and development decisions [22]. | Brings the "comparative method" to the clinic, using real-world human diversity to validate or challenge findings from controlled, mechanistic trials. |

The following experimental workflow diagram illustrates how these tools are integrated into a modern, trap-avoiding drug development pipeline.

Diagram 1: Integrative drug development workflow.

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Drug Target with an Integrative Approach

This protocol outlines a key experiment that combines both comparative and mechanistic methods to avoid the essentialist trap in early-stage drug discovery.

- Objective: To identify and preliminarily validate a novel therapeutic target for a complex disease (e.g., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome - PCOS) using an integrative methodology that transcends reliance on a single model [23].

- Hypothesis: Gene X, identified through a comparative analysis of human genomic data, plays a conserved but context-dependent role in a metabolic pathway relevant to PCOS pathology.

Methodology:

- Comparative Identification (The "Comparative Method"):

- Data Collection: Curate large-scale human genomic and transcriptomic datasets from consortia like UK Biobank, including data from PCOS patients and healthy controls of diverse ancestries [19].

- AI/ML Analysis: Employ machine learning algorithms (e.g., deep neural networks) to perform a genome-wide association study (GWAS) and differential expression analysis. The goal is to identify Gene X, which shows a strong statistical association with PCOS phenotypes across a broad population, not just a homogenous cohort [21].

- Mechanistic Validation (The "Mechanistic Approach"):

- In Vitro Model: Transfer the findings into a controlled lab setting. Use CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to create a knockout of the ortholog of Gene X in a human cell line relevant to PCOS (e.g., ovarian granulosa cell line). The use of a human-derived cell line is a conscious choice to reduce cross-species extrapolation error at this stage.

- Phenotypic Assays: Measure downstream effects of Gene X knockout using high-content imaging and molecular profiling (RNA-seq, proteomics) to map the altered pathway mechanisms [23].

- Integrative Synthesis (Bridging the Approaches):

- QSP Modeling: Build a preliminary QSP model that incorporates the kinetic parameters of the pathway affected by Gene X, derived from the in vitro data.

- In Silico Prediction: Use this model to simulate the effect of modulating Gene X activity in a simulated virtual population, predicting which patient subpopulations (e.g., defined by specific genetic backgrounds) would most likely respond to a therapy targeting Gene X [20]. This step directly tests if the mechanistic finding from the cell line holds across a more diverse, "comparative" virtual cohort.

Visualizing the Scientific Workflow: From Trap to Synthesis

The conceptual journey from a constrained, model-centric vision to a pluralistic, integrative one is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: Shifting from essentialist trap to integrative pluralism.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and tools that are foundational for the experiments cited in this article, particularly for the integrative validation of novel drug targets.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrative Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing System | Precise knockout or modification of specific genes in model systems to determine gene function. | Creating isogenic cell lines with a target gene (e.g., Gene X from protocol) knocked out to study its mechanistic role in a pathway [23]. |

| Trusted Research Environment (TRE) | A secure data platform that allows analysis of sensitive genomic and clinical data without the data leaving a protected environment. | Enabling the comparative analysis of large-scale human data (e.g., from UK Biobank) for target identification while preserving patient privacy [19]. |

| Federated Learning AI Platform | A machine learning technique where an algorithm is trained across multiple decentralized data holders without sharing the data itself. | Allowing a drug target prediction model to learn from diverse, proprietary datasets across multiple hospitals or research institutes, mitigating bias [19]. |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Software | Software that implements PBPK modeling to simulate the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of a compound. | Predicting human pharmacokinetics and drug-drug interactions early in development, reducing reliance on animal model extrapolation alone [20]. |

| Validated Antibodies for Pathway Analysis | Antibodies used in Western Blot or Immunohistochemistry to detect and quantify specific proteins in a biological sample. | Measuring the expression levels of proteins in a hypothesized pathway (e.g., in PCOS models) after a genetic or therapeutic intervention [23]. |

The history of biology shows that scientific progress is often hampered not by a lack of tools, but by a lack of vision. The essentialist trap—the uncanny, unconscious narrowing of scientific inquiry through over-reliance on a few model systems—is a profound but surmountable challenge. As philosopher William Bechtel's approach suggests, the path forward is not to discard the powerful, detail-generating mechanistic approach, but to embed it within a framework of integrative pluralism [24]. This requires a conscious effort to continually place mechanistic findings within the broader, comparative context of biological diversity, whether that diversity is found across species or within human populations.

The transformation already underway in drug development, through Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) and AI-driven analyses of diverse datasets, serves as a powerful template for all of biology [20] [21]. By deliberately using multiple kinds of models and bringing them into productive contact, we can free ourselves from the essentialist trap. The future of biological discovery, and the rapid translation of that discovery into therapies, depends on a vision that values both the deep, causal story and the broad, comparative narrative that together reveal the true richness of the living world.

The history of biological discovery has been shaped by two fundamentally different yet complementary approaches: the comparative method and the mechanistic approach. The comparative method, rooted in historical analysis and pattern observation, seeks to understand biological diversity through examination of similarities and differences across species, lineages, and evolutionary time [3]. In contrast, the mechanistic approach focuses on dissecting proximate causes through experimental intervention to uncover the physicochemical underpinnings of biological processes [3] [25]. This article examines how these distinct methodologies have collectively advanced biological knowledge, driven drug discovery, and shaped modern research paradigms.

The tension and synergy between these approaches reflect a deeper philosophical divide in scientific pursuit. While the mechanistic approach offers deep, causal explanations of how specific biological systems operate, the comparative method provides broader evolutionary context for why these systems vary across organisms [3]. As biology increasingly embraces both perspectives through fields like Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Evo-Devo), understanding their respective contributions and limitations becomes essential for navigating contemporary research challenges.

The Comparative Method: Understanding Through Patterns

Historical Foundations and Key Principles

The comparative method dates to Aristotle and gained substantial momentum through 19th-century comparative anatomy [3]. This approach fundamentally views organisms as historical products, with their unique characteristics reflecting evolutionary diversification patterns [3]. By analyzing regularities and variations across species, researchers can reconstruct evolutionary histories and identify homologous structures—shared characters derived from common ancestors [3].

Table 1: Historical Applications of the Comparative Method in Biology

| Era | Key Researchers | Primary Contribution | Impact on Biological Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19th Century | Geoffroy, Cuvier | Comparative anatomy | Established structural homologies across species [3] |

| Early 20th Century | Medawar, Comfort, Sacher | Lifespan and mortality patterns | Developed foundational concepts in biogerontology [9] |

| Late 20th Century | Willi Hennig | Phylogenetic systematics | Introduced cladistic methodology based on synapomorphies [3] |

| Contemporary Genomic Era | Comparative genomics consortia | Cross-species sequence analysis | Identified conserved genes and regulatory elements [26] |

The introduction of phylogenetic systematics by Willi Hennig revolutionized comparative biology by providing rigorous methods for classifying organisms based on evolutionary relationships rather than superficial similarities [3]. His crucial distinction between plesiomorphic (ancestral) and synapomorphic (derived) characters enabled biologists to identify sister groups and reconstruct evolutionary history with greater accuracy [3].

Modern Applications: Comparative Genomics

Contemporary comparative biology finds powerful expression in comparative genomics, which leverages evolutionary conservation to identify functional genetic elements. This approach operates on the principle that important biological sequences are conserved between species due to functional constraints [26]. The strategic selection of species for comparison—balancing evolutionary distance, biological relevance, and sequence conservation—has proven crucial for deciphering genomic function [26].

Table 2: Comparative Genomics Applications and Discoveries

| Comparative Framework | Evolutionary Distance | Key Discoveries | Biological Insights Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-Mouse | ~80 million years | APOA5 gene identification [26] | Discovery of pivotal regulator of plasma triglyceride levels [26] |

| Human-Rodent | ~80-100 million years | Interleukin gene cluster regulation [26] | Identification of conserved coordinate regulatory element controlling three interleukin genes [26] |

| Human-Fish | ~400 million years | Conserved non-coding elements | Identification of long-range gene regulatory sequences [26] |

| Multiple vertebrate comparisons | Varying distances | "Phylogenetic footprinting" | Detailed characterization of transcription factor binding sites [26] |

A landmark application of comparative genomics emerged from human-mouse sequence comparisons, which revealed the previously unknown apolipoprotein A5 gene (APOA5) based on its high degree of sequence conservation within a well-studied cluster of apolipoproteins [26]. Subsequent functional studies demonstrated that this gene serves as a pivotal determinant of plasma triglyceride levels, with significant implications for understanding cardiovascular disease [26]. Similarly, comparative analysis of interleukin gene clusters uncovered a highly conserved 401-basepair non-coding sequence that coordinates the expression of three interleukin genes across 120 kilobases of genomic sequence—a regulatory relationship that had eluded traditional experimental approaches [26].

Experimental Protocols in Comparative Biology

Protocol 1: Cross-Species Sequence Analysis for Gene Discovery

- Sequence Alignment: Select genomic regions of interest from multiple species with varying evolutionary distances (e.g., human, mouse, zebrafish, pufferfish) [26].

- Conservation Detection: Use computational tools (e.g., BLASTZ, MultiPipMaker) to identify evolutionarily conserved sequences with significantly reduced mutation rates [26].

- Functional Annotation: Classify conserved sequences as coding exons, regulatory elements, or structural components based on sequence features and genomic context.

- Expression Validation: Isolate transcripts from relevant tissues (e.g., liver for APOA5) using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to confirm conserved sequences represent expressed genes [26].

- Functional Characterization: Employ transgenic and knockout animal models to determine the physiological role of newly identified genes [26].

Protocol 2: Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis in Aging Research

- Trait Data Collection: Assemble lifespan, metabolic rate, and body size data across multiple taxa (e.g., mammals, birds, reptiles) [9].

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Build or select a phylogenetic tree representing evolutionary relationships among studied species.

- Statistical Control for Phylogeny: Use comparative methods (e.g., independent contrasts, phylogenetic generalized least squares) to account for shared evolutionary history [9].

- Correlation Analysis: Test hypotheses about evolutionary trade-offs (e.g., between reproduction and longevity) while controlling for phylogenetic non-independence [9].

- Exception Identification: Identify exceptionally long- or short-lived species for further mechanistic study (e.g., naked mole-rats for aging research) [9].

Figure 1: Comparative genomics workflow for identifying functional elements through evolutionary conservation.

The Mechanistic Approach: Dissecting Causality

Historical Development and Philosophical Foundations

The mechanistic approach in biology traces its origins to the concept of "Entwicklungsmechanik" or developmental mechanics, which emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries [3]. This perspective gained substantial momentum with the rise of physiology, genetics, and molecular biology, which provided tools and conceptual frameworks for dissecting biological processes into constituent parts and interactions [3]. The approach focuses on proximate causes—how biological systems operate through molecular interactions, biochemical pathways, and physical forces.

Philosophically, mechanistic inquiry is guided by normative constraints to increase the intelligibility of phenomena and completely uncover their causal structure [25]. This often involves developing multiple complementary models that capture different aspects of how various entities and activities contribute to a mechanism's operation [25]. In contemporary biology, the mechanistic approach is characterized by deep investigation into specific model systems, with the assumption that fundamental biological processes are conserved across diverse organisms [3].

Model Systems and Their Limitations

The mechanistic approach relies heavily on a limited set of model organisms selected for practical experimental considerations: short generation times, ease of laboratory manipulation, and availability of genetic tools [3]. These include baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), nematodes (Caenorhabditis elegans), fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), and inbred laboratory mice (Mus musculus) [9]. While this strategy has been enormously productive, it has introduced what some term an "essentialist trap"—the assumption that a handful of model systems can adequately represent biological diversity [3].

Table 3: Traditional Model Organisms in Mechanistic Biology

| Model Organism | Key Experimental Advantages | Semantic Contributions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Baker's yeast) | Rapid reproduction, easy genetic manipulation | Cell cycle regulation, aging mechanisms [9] | Limited relevance to multicellular organization |

| Caenorhabditis elegans (Nematode) | Transparent body, invariant cell lineage | Programmed cell death, neural development | Simplified physiology compared to vertebrates |

| Drosophila melanogaster (Fruit fly) | Complex development, genetic toolbox | Embryonic patterning, signal transduction | Evolutionary distance from mammalian systems |

| Mus musculus (Laboratory mouse) | Mammalian physiology, genetic models | Immunological function, drug metabolism | Inbred lines lack genetic diversity of wild populations [9] |

The use of inbred laboratory models has produced a streamlined version of animal species that incorporates essentialist/typological undertones, potentially misrepresenting the true diversity of biological systems [3]. This limitation has become increasingly apparent as researchers discover substantial plasticity in developmental processes across different organisms [3].

Experimental Protocols in Mechanistic Research

Protocol 3: Gene Regulatory Element Characterization

- Candidate Identification: Identify putative regulatory sequences through comparative genomics or chromatin features [26].

- Reporter Construct Design: Clone candidate sequences upstream of a minimal promoter driving a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, luciferase).

- Transgenic Validation: Introduce reporter constructs into model organisms (e.g., mouse zygotes) or cell cultures.

- Expression Pattern Analysis: Document spatial and temporal reporter expression to determine regulatory function.

- Binding Site Mapping: Use "phylogenetic footprinting" to identify transcription factor binding sites through cross-species sequence comparison [26].

- Functional Disruption: Employ CRISPR-Cas9 to delete endogenous regulatory elements and assess phenotypic consequences [26].

Protocol 4: Visual Processing Circuit Mapping

- Anatomical Tracing: Inject neuronal tracers (e.g., horseradish peroxidase, fluorescent dextrans) into specific brain regions.

- Electrophysiological Recording: Measure neuronal responses to visual stimuli using single-unit or multi-electrode arrays.

- Computational Modeling: Develop canonical microcircuit models representing connectivity patterns and signal transformations [25].

- Model Testing: Generate predictions from competing circuit models and test through targeted experimental manipulations [25].

- Model Refinement: Iteratively revise models based on empirical evidence, pursuing both complementary and competing explanations [25].

Figure 2: Iterative cycle of mechanistic inquiry involving hypothesis generation, experimental intervention, and model refinement.

Case Study Integration: Aging Research

Complementary Insights from Both Approaches

Aging research exemplifies how comparative and mechanistic approaches provide complementary insights. The comparative method has revealed extraordinary diversity in aging patterns across species—from short-lived rodents to centuries-old naked mole-rats and bowhead whales [9]. These observations have tested mechanistic theories, including the oxidative damage hypothesis, by examining whether exceptional longevity correlates with enhanced antioxidant capacity or reduced oxidative damage across species [9].

The mechanistic approach has dissected conserved longevity pathways through genetic manipulations in model organisms, identifying insulin/IGF-1 signaling, mTOR pathways, and mitochondrial function as critical regulators of lifespan [9]. However, the limitations of standard laboratory models—inbred strains maintained in pathogen-free environments—have prompted calls for incorporating wild-derived, outbred animal models that may better represent natural aging processes [9].

Data Exploration and Quantitative Analysis

Modern biological research increasingly depends on sophisticated data exploration workflows that serve both comparative and mechanistic approaches [27]. Effective data exploration requires flexible, visualization-rich approaches that reveal trends, identify outliers, and refine hypotheses [27]. Quantitative cell biology exemplifies this integration, employing both:

- Continuous data: Measured values within a range (e.g., fluorescence intensity, cell size) [27]

- Categorical data: Distinct groups or categories (e.g., control vs. treated, wild type vs. mutant) [27]

Best practices include assessing biological variability through SuperPlots that display individual data points by biological repeat while capturing overall trends, and maintaining meticulous metadata tracking to understand variability and ensure reproducibility [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Comparative and Mechanistic Biology

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Tools | BLASTZ, MultiPipMaker, phylogenetic footprinting algorithms | Identify evolutionarily conserved sequences [26] | Comparative genomics, regulatory element discovery |

| Model Organisms | Inbred laboratory mice (Mus musculus), wild-derived species (Peromyscus) [9] | Experimental manipulation, natural genetic variation studies | Mechanistic testing, evolutionary adaptations |

| Visualization Reagents | Horseradish peroxidase, fluorescent dextrans, GFP reporters | Neuronal tracing, gene expression monitoring | Circuit mapping, promoter analysis |

| Data Analysis Platforms | R, Python with imaging libraries (e.g., scikit-image) [27] | Quantitative analysis, statistical modeling | Data exploration, hypothesis testing |

| Genetic Manipulation Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, transgenic constructs, knockout models | Gene function assessment | Causal testing, validation of conserved elements |

The historical development of biology reveals that comparative and mechanistic approaches are not competing alternatives but complementary strategies that collectively drive scientific progress. The comparative method provides the essential evolutionary context for interpreting biological diversity, while the mechanistic approach offers causal explanations for how specific biological systems operate [3]. Rather than representing a dichotomy, these approaches form a continuum of biological inquiry [25].

Future progress will depend on effectively integrating both perspectives—employing comparative methods to identify evolutionarily significant phenomena and mechanistic approaches to dissect their underlying causal structures. This integration is particularly crucial for addressing complex biomedical challenges, where evolutionary insights can guide mechanistic investigation toward biologically significant targets, and mechanistic understanding can translate comparative observations into therapeutic strategies [9]. As biology continues to evolve, the productive tension between these approaches will remain essential for generating deep, comprehensive understanding of living systems.

From Theory to Bench: A Practical Guide to Implementing Each Approach

In modern biological research and drug development, two fundamental philosophies guide experimentation: the comparative approach and the mechanistic approach. The comparative method relies on observing and correlating differences between biological states, often through high-throughput screening and omics-scale comparisons. In contrast, the mechanistic approach seeks to establish causal relationships by systematically perturbing biological systems and quantitatively measuring outcomes. This guide objectively evaluates key methodologies for executing the mechanistic approach, focusing on three foundational pillars: genetic manipulation technologies, molecular assays for validation, and computational frameworks for pathway analysis. Each method carries distinct advantages and limitations that determine its appropriate application across different research contexts, from basic biological discovery to therapeutic development.

The mechanistic approach demands tools that enable precise intervention, accurate measurement, and meaningful interpretation of biological processes. Recent advances in CRISPR technology, artificial intelligence, and modeling frameworks have significantly enhanced our ability to dissect causal mechanisms in complex biological systems. By comparing the performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and output data of these methodologies, researchers can make informed decisions about which tools best address their specific scientific questions within a mechanistic research paradigm.

Comparative Analysis of Genetic Manipulation Techniques

Genetic manipulation represents the cornerstone of the mechanistic approach, enabling researchers to establish causal relationships between genes and phenotypes. Current methodologies offer diverse mechanisms of action, temporal dynamics, and specificity profiles. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of four prominent genetic perturbation techniques based on recent experimental data.

Table 1: Performance comparison of genetic manipulation techniques

| Method | Mechanism of Action | Temporal Onset | Off-target Transcripts | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Knock-out | Permanent DNA cleavage and gene disruption | Delayed (protein degradation-dependent) | 70% overlap with control [28] | Functional genomics, disease modeling |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) | mRNA degradation and translational inhibition | Intermediate (24-72 hours) | 10% overlap with control [28] | High-throughput screening, target validation |

| Antibody-mediated Loss-of-function | Intracellular antibody-target interaction | Rapid (<24 hours) | 30% overlap with control [28] | Acute functional inhibition, signaling studies |

| CRISPR Activation/Inhibition | Epigenetic modulation of gene expression | Intermediate to delayed (24-96 hours) | Varies by guide RNA design [29] | Gene regulatory studies, synthetic circuits |