Applied Evolutionary Biology: Principles for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for applying evolutionary principles to accelerate drug discovery and address core challenges in biomedical research.

Applied Evolutionary Biology: Principles for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for applying evolutionary principles to accelerate drug discovery and address core challenges in biomedical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational concepts—variation, selection, connectivity, and eco-evolutionary dynamics—into a practical methodology. We explore how evolutionary thinking can inform target identification, combat antibiotic resistance, optimize clinical trials, and validate novel therapeutic strategies. By integrating evolutionary biology with pharmaceutical science, this primer aims to foster a unified, multidisciplinary approach to developing more effective and durable medical interventions.

The Evolutionary Roots of Disease and Treatment: Core Principles for Biomedicine

Evolution, in its most fundamental applied context, refers to the change in heritable traits of biological populations over successive generations, driven by mechanisms including natural selection, genetic drift, and gene flow. In modern research settings, this definition extends to measurable changes in allele frequencies and phenotypic expressions that impact fitness and function. Evolutionary mismatch represents a critical phenomenon within applied evolutionary biology, occurring when previously adaptive traits become maladaptive in novel environments, creating a state of detrimental disequilibrium between an organism and its altered surroundings [1] [2]. This concept operates across both temporal and spatial dimensions, where traits that evolved in ancestral environments (E1) become mismatched in contemporary environments (E2), leading to reduced fitness or health outcomes [3].

The framework for understanding mismatch necessitates clear identification of three core components: the specific population involved, the trait(s) under investigation, and the environmental contexts (both ancestral and novel) that define the selective pressures [3]. This paradigm has profound implications across multiple fields, from disease etiology and drug development to conservation biology and public health policy. Applied evolutionary biology research utilizes this framework to decipher the origins of modern health disorders, develop targeted therapeutic interventions, and predict species responses to rapid environmental change, particularly anthropogenic transformations that characterize the Anthropocene [1] [3].

Quantitative Frameworks for Analyzing Mismatch

Modeling Trait Evolution and Selection

Advanced statistical models are essential for quantifying evolutionary processes and identifying mismatch in biological systems. The Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process has emerged as a powerful framework for modeling the evolution of continuous traits, such as gene expression levels, under stabilizing selection [4]. This model elegantly parameterizes the interplay between selective pressures and stochastic drift, described by the equation: dXₜ = σdBₜ + α(θ - Xₜ)dt, where Xₜ represents the trait value, σ quantifies the rate of random drift (Brownian motion), α represents the strength of stabilizing selection pulling the trait toward an optimal value θ, and dBₜ denotes stochastic noise [4].

Research analyzing RNA-seq data across seven tissues from 17 mammalian species demonstrates that gene expression evolution follows OU dynamics rather than neutral drift patterns [4]. This approach enables researchers to distinguish between neutral evolution, stabilizing selection, and directional selection on phenotypic traits. The OU model's asymptotic variance (σ²/2α) quantitatively represents the evolutionary constraint on a trait, with higher values indicating greater permissible deviation from the optimum before fitness costs accumulate [4]. This statistical framework allows for the identification of deleterious trait values in clinical samples by comparing observed expressions to evolutionarily optimized distributions, facilitating the nomination of candidate disease genes and pathways [4].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Evolutionary Models of Trait Dynamics

| Parameter | Biological Interpretation | Application in Mismatch Research |

|---|---|---|

| θ | Optimal trait value under stabilizing selection | Reference point for identifying maladaptive traits in novel environments |

| α | Strength of stabilizing selection | Quantifies how rapidly fitness declines as trait deviates from optimum |

| σ | Rate of random drift in trait value | Measures stochastic evolutionary forces independent of selection |

| Evolutionary Variance (σ²/2α) | Expected trait variance under stabilizing selection | Benchmark for evaluating whether observed trait variance indicates mismatch |

Experimental Evolution and Rescue Paradigms

Evolutionary rescue (ER) experiments provide a robust methodological approach for studying mismatch dynamics in controlled settings. These investigations examine how populations persist when faced with abrupt environmental changes that would otherwise cause extinction [5]. The experimental framework typically involves introducing replicate populations to stressful novel environments and monitoring demographic and genetic changes over successive generations.

Protocols for evolutionary rescue studies require careful consideration of several key elements [5]:

- Population replicates: Sufficient replicates (typically >10) to account for stochasticity in evolutionary processes

- Environmental control: Precise manipulation of environmental factors to create defined selective pressures

- Generational monitoring: Tracking of demographic parameters (birth, death, migration rates) and phenotypic traits across generations

- Selection quantification: Measurement of selection differentials and heritability of traits affecting fitness

These experiments have revealed that phenotypic plasticity significantly influences rescue trajectories. Populations with adaptive plasticity often show higher persistence rates following environmental shifts, as pre-existing plasticity provides immediate fitness benefits while genetic adaptations accumulate [5]. The experimental evolution approach allows researchers to quantify costs and benefits of plasticity, measure generalist-specialist trade-offs, and determine the genetic architecture underlying rapid adaptation to novel environments [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics in Evolutionary Rescue Experiments

| Metric | Measurement Approach | Interpretation in Mismatch Context |

|---|---|---|

| Population Growth Rate (λ) | Counts or estimates across generations | λ<1 indicates declining population; λ≥1 suggests potential rescue |

| Selection Differential (S) | Covariance between trait and fitness | Strength of selection on mismatched traits |

| Rate of Adaptation | Change in mean fitness per generation | Speed at which population compensates for mismatch |

| Plasticity Coefficient | Reaction norm slope | Degree of phenotypic response to environmental change |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Comparative Genomics and Transcriptomics

Genomic approaches enable researchers to identify evolutionary mismatch at the molecular level through comparative analysis across species and populations. Standardized protocols for these investigations include:

RNA-seq Cross-Species Analysis Protocol [4]:

- Tissue Collection: Preserve tissues from multiple species in RNAlater or similar stabilization reagents

- RNA Extraction: Use column-based or TRIzol methods with DNase treatment

- Library Preparation: Employ stranded mRNA-seq protocols with unique dual indexing

- Sequencing: Conduct minimum 30M paired-end reads (2x150bp) on Illumina platforms

- Ortholog Identification: Map to respective genomes using STAR/Salmon pipelines; identify one-to-one orthologs via reciprocal best BLAST

- Expression Quantification: Calculate TPM or FPKM values with correction for GC content and transcript length biases

- Evolutionary Modeling: Fit OU processes to expression trajectories using phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS)

- Selection Testing: Compare OU models with Brownian motion null models via likelihood ratio tests

This protocol successfully identified stabilizing selection on gene expression levels across 17 mammalian species, revealing that approximately 70% of mammalian genes show signatures of expression constraint in at least one tissue type [4]. The method enables detection of genes whose expression has evolved under directional selection in specific lineages, potentially indicating adaptations to novel environmental challenges.

Mismatch Detection in Clinical and Ecological Contexts

Applied protocols for identifying mismatch in human health and wildlife populations include:

Human Mismatch Assessment Framework [3]:

- Ancestral Environment Reconstruction: Integrate archaeological, anthropological, and physiological data to characterize E1

- Contemporary Environment Analysis: Quantify key differences between E1 and E2 relevant to the trait of interest

- Trait Function Mapping: Determine the trait's adaptive significance in E1 versus its fitness consequences in E2

- Intervention Testing: Develop and evaluate strategies to ameliorate mismatch effects

Experimental Evolution Protocol [5]:

- Base Population Establishment: Create genetically variable founder populations through hybridization or sampling

- Environmental Shift Implementation: Apply controlled environmental change (thermal, nutritional, chemical)

- Generational Monitoring: Track population size, individual fitness, and trait values across generations

- Selection Analysis: Estimate selection gradients and evolutionary responses using animal models or similar approaches

- Plasticity Assessment: Measure reaction norms by raising genotypes across multiple environments

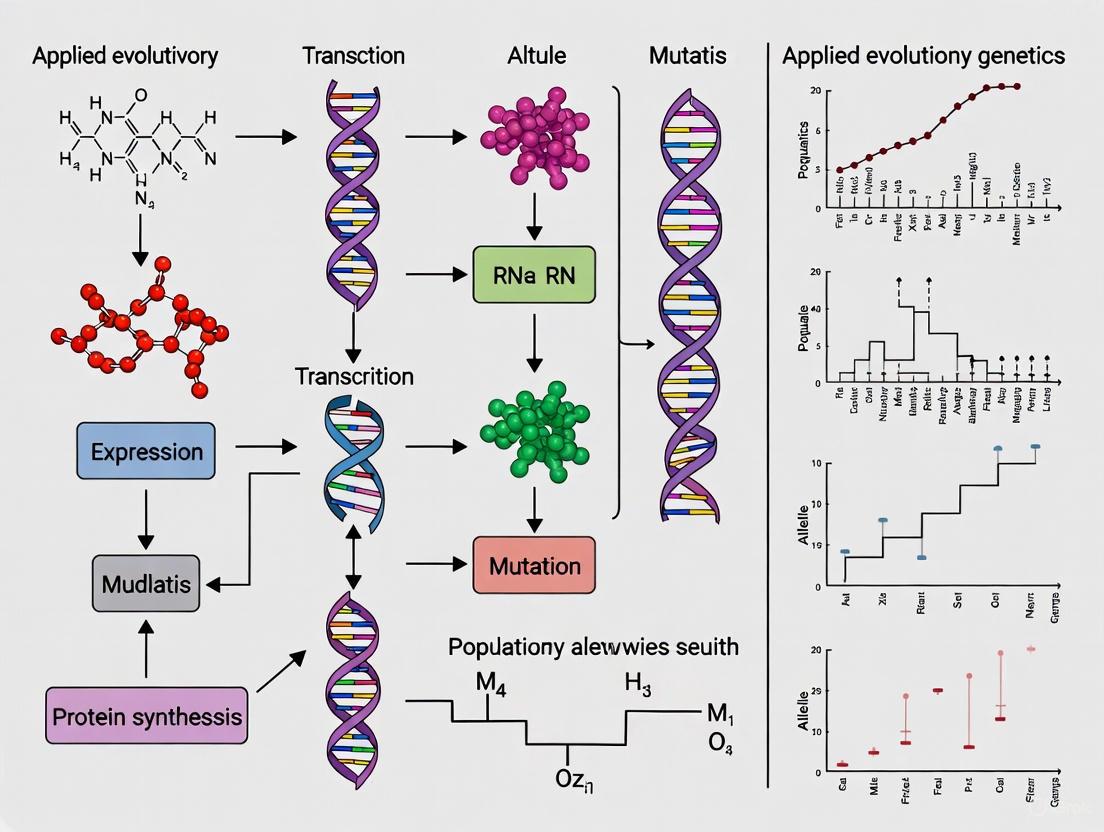

Visualization of Evolutionary Mismatch Concepts

Evolutionary Mismatch Conceptual Framework

Mismatch Research Workflow

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Evolutionary Mismatch Investigations

| Reagent/Material | Specific Application | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Tissue preservation for transcriptomics | Maintains RNA integrity during collection from multiple species |

| Illumina RNA-seq Library Prep Kits | Comparative transcriptomics | Generates sequencing libraries for expression profiling across evolutionary lineages |

| Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplification of orthologous loci | Enables sequencing of specific genetic regions across species with high accuracy |

| DNeasy/RNEasy Kits | Nucleic acid extraction | Standardized isolation of high-quality genetic material from diverse tissue types |

| Custom Synthesized Oligonucleotides | Phylogenetic marker development | Amplifies conserved genetic regions for constructing robust species trees |

| Restriction Enzymes | Genotyping-by-sequencing libraries | Facilitates reduced-representation sequencing for population genomic studies |

| SYBR Green/TAQMAN Master Mix | Quantitative PCR validation | Confirms RNA-seq expression patterns for candidate mismatch genes |

| Cell Culture Media Formulations | Experimental evolution studies | Creates defined environmental conditions for selection experiments |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Systems | Functional validation of candidate loci | Tests phenotypic effects of putative adaptive alleles in model systems |

| Histology Reagents | Tissue structure analysis | Correlates molecular changes with phenotypic alterations in anatomical traits |

| Titanium triisostearoylisopropoxide | Titanium triisostearoylisopropoxide, CAS:61417-49-0, MF:C57H116O7Ti, MW:961.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-bromo-2H-pyran-2-one | 3-Bromo-2H-pyran-2-one|CAS 19978-32-6|≥98% | 3-Bromo-2H-pyran-2-one (CAS 19978-32-6), an ambiphilic diene for Diels-Alder cycloadditions. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The framework of evolutionary mismatch provides a powerful paradigm for interpreting modern health challenges through an evolutionary lens. The thrifty genotype hypothesis exemplifies this approach, explaining how energy-efficient genotypes selected in feast-or-famine ancestral environments now contribute to obesity and diabetes epidemics in calorie-abundant modern societies [1] [2]. Similarly, the hygiene hypothesis links reduced exposure to microorganisms in sanitized contemporary environments to increased incidence of autoimmune and allergic disorders [1] [2]. These examples underscore how applied evolutionary biology moves beyond proximate biological explanations to ultimate evolutionary causation.

Future research directions in evolutionary mismatch should prioritize longitudinal studies tracking genetic and phenotypic changes in real-time, integration of ancient DNA analyses to reconstruct ancestral trait states, and development of computational models that better predict mismatch trajectories under various environmental change scenarios [4] [3]. Additionally, expanding mismatch frameworks to incorporate cultural evolution and gene-culture coevolution will provide more comprehensive models for addressing human health challenges in rapidly changing environments [3]. By employing the quantitative frameworks, experimental protocols, and research tools outlined in this technical guide, researchers can systematically investigate and potentially mitigate the detrimental consequences of evolutionary mismatch across biological systems.

Applied evolutionary biology utilizes evolutionary principles to address practical challenges in fields such as medicine, agriculture, conservation biology, and natural resource management [6]. Despite the shared fundamental concepts underlying these applications, their adoption has often proceeded independently across different disciplines. This whitepaper synthesizes these core principles into four unifying pillars—variation, selection, connectivity, and eco-evolutionary dynamics—to advance a unified multidisciplinary framework [6] [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this framework provides essential insights for predicting evolutionary responses and designing effective interventions, from managing antibiotic resistance to improving crop yields [6].

The Foundational Pillars

Variation

Phenotypic variation, which includes genetic differences, individual phenotypic plasticity, epigenetic changes, and maternal effects, determines how organisms interact with their environment and respond to selection pressures [6]. Understanding the origins and maintenance of this variation is foundational for predicting responses to changing conditions, such as climate change or novel drug treatments [6].

Key Concepts and Research Applications:

- Phenotypes are the Direct Interface: Selection acts directly on phenotypes, with genetic change occurring as an indirect consequence. Phenotypes also have direct ecological effects on population dynamics and ecosystem function [6].

- Reaction Norms: Phenotypic traits should be considered as reaction norms—the range of phenotypes a genotype can express across different environmental conditions. These norms can themselves evolve [6].

- Identifying Key Traits: A central task is identifying "key" traits strongly linked to fitness or ecological processes. This is typically done by relating variation in measured traits to fitness components (e.g., survival, fecundity) and ecological responses [6].

Table 1: Types and Origins of Phenotypic Variation

| Type of Variation | Origin/Source | Practical Research Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic | Differences in DNA sequence (alleles) | Provides the raw material for long-term adaptation; measured via genomic tools [6]. |

| Phenotypic Plasticity | Ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in different environments | Allows for rapid, non-genetic response to environmental change; quantified via reaction norm studies [6]. |

| Epigenetic | Modifications to DNA or histones that regulate gene expression | Can be heritable; mechanism for environmental effects to be transmitted across generations [6]. |

| Maternal Effects | Influence of the mother's phenotype on her offspring's phenotype | Can cause time lags in evolutionary response and affect population dynamics [6]. |

Selection

Selection occurs when environmental pressures create a mismatch between an organism's current phenotype and the optimal phenotype for that environment, leading to differential survival and reproduction [6]. In applied contexts, the goal can be to minimize this mismatch (e.g., for conservation) or maximize it (e.g., for pest control) [6].

Key Concepts and Research Applications:

- Measuring Selection: The strength and direction of selection can be quantified by relating variation in phenotypic traits to fitness metrics such as lifetime reproductive success or major fitness components (survival, fecundity) using statistical methods like multiple regression [6].

- Natural vs. Artificial Selection: Applied biology often involves artificial selection (e.g., in crop breeding) or human-induced natural selection (e.g., antibiotic and pesticide application), both of which are powerful evolutionary forces [6].

- Maladaptation: Selection can sometimes lead to traits that increase individual fitness (relative fitness) but reduce the mean absolute fitness of the population (e.g., rate of increase), a crucial consideration for managing harvested species [6].

Connectivity

Connectivity, or gene flow, refers to the movement of individuals and their genetic material between populations. It is a critical determinant of population structure, genetic diversity, and adaptive potential [6] [8]. Landscape pattern is a primary driver of connectivity, influencing dispersal and mating success [8].

Key Concepts and Research Applications:

- Gene Flow and Local Adaptation: Gene flow can introduce beneficial alleles into a population, increasing adaptive potential. However, high gene flow can also swamp local adaptation by introducing maladapted genes [6].

- Inbreeding Avoidance: In small, isolated populations, limited connectivity leads to inbreeding and loss of genetic variation, increasing extinction risk. Connectivity helps maintain genetic health [6].

- Spatially-Explicit Modeling: Modern tools like individual-based, spatially-explicit models (e.g., HexSim) allow researchers to mechanistically simulate how complex landscapes structure gene flow, moving beyond simplistic migration parameters ('m') to more realistic forecasts [8].

Table 2: Connectivity Considerations in Applied Research

| Context | High Connectivity | Low Connectivity |

|---|---|---|

| Conservation Biology | Maintains genetic diversity; prevents inbreeding depression. | Leads to loss of genetic diversity; increases extinction risk. |

| Pest/Pathogen Management | Can speed the spread of resistance alleles. | Can allow for localized containment or eradication strategies. |

| Drug Development (e.g., antibiotic resistance) | Horizontal gene transfer between bacterial strains acts as a form of connectivity. | --- |

| Research Method | Utility | Limitations |

| Landscape Genetics | Links landscape patterns to observed genetic structure [8]. | Historically limited in spatial/demographic sophistication [8]. |

| Spatially-Explicit Individual-Based Models | Mechanistically simulates gene flow and mating in complex landscapes [8]. | Computationally intensive; requires detailed parameterization [8]. |

Eco-evolutionary Dynamics

Eco-evolutionary dynamics result when ecological and evolutionary processes interact reciprocally and occur on the same contemporary time scale [9]. Ecological change can drive rapid evolutionary change, which in turn can leave a detectable signature on ecological processes such as population dynamics, community composition, and ecosystem function [9].

Key Concepts and Research Applications:

- Contemporary Evolution: Evolution can occur rapidly enough (over a few generations) to influence ecological processes in real-time, contradicting the traditional view that evolution is too slow to be ecologically relevant [9].

- Bidirectional Feedback: The core of eco-evolutionary dynamics is the feedback loop: ecological changes (e.g., new predator) cause evolutionary changes (e.g., prey defense traits), which subsequently alter the ecological context (e.g., predator population dynamics) [9].

- Demographic Links: Because natural selection acts on traits linked to survival and reproduction, it directly influences demographic rates and thus population growth and dynamics [9].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics

Common Garden and Reciprocal Transplant Designs

Objective: To disentangle the genetic (evolutionary) and environmental (plastic) components of phenotypic variation and to test for local adaptation [6].

Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect individuals or propagules (seeds, larvae) from multiple populations across an environmental gradient (e.g., temperature, pesticide exposure).

- Common Garden Experiment: Raise collected samples in a uniform controlled environment (e.g., lab, common garden). Phenotypic differences observed under these conditions can be attributed to genetic differences.

- Reciprocal Transplant Experiment: Transplant individuals from each population back into their native environment and into the other populations' environments. Additionally, raise individuals from all populations in a controlled neutral environment.

- Fitness Measurement: Measure fitness components (e.g., survival, growth rate, reproduction) in each environment.

- Data Analysis: Local adaptation is indicated when "local" genotypes have higher fitness than "foreign" genotypes in their home environment. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) of fitness data can partition the variance into effects of population (genetic), environment (plastic), and their interaction (GxE).

Estimating Selection Gradients

Objective: To quantify the strength and form of natural selection acting on specific phenotypic traits in a wild or experimental population [6].

Protocol:

- Phenotypic Measurement: Measure the traits of interest (e.g., body size, beak depth, flowering time) on a large number of individuals in the population at a specific life stage.

- Fitness Assignment: Record a measure of relative fitness for each individual (e.g., survival to a later life stage, lifetime reproductive success, number of seeds produced).

- Standardization: Standardize both the trait values (to mean=0, standard deviation=1) and the relative fitness values (to mean=1) across the population.

- Regression Analysis: Perform a multiple linear regression of standardized relative fitness on the standardized trait values. The partial regression coefficients for each trait represent the directional selection gradient (β). To detect nonlinear selection (e.g., stabilizing or disruptive), a multiple quadratic regression model is used, including squared trait terms.

Spatially-Explicit Individual-Based Simulation

Objective: To mechanistically model and forecast how landscape pattern and dynamic processes influence eco-evolutionary outcomes like gene flow, local adaptation, and population viability [8].

Protocol (using a platform like HexSim):

- Landscape Representation: Construct a raster-based landscape map where each cell is assigned a habitat type with associated qualities and permeabilities.

- Individual Parameterization: Define a population of individuals, each with a set of demo-genetic traits (e.g., sex, age, genotype at neutral or functional loci, dispersal propensity).

- Process Definition: Program life history processes (e.g., survival, reproduction, dispersal, mating, resource use) as functions of an individual's traits, its location, and the surrounding landscape.

- Model Execution: Run the simulation over hundreds to thousands of time steps, tracking emergent properties such as allele frequencies, population size, and movement pathways.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test the effect of different landscape scenarios (e.g., habitat fragmentation, climate change) or biological parameters (e.g., mutation rate, strength of selection) on the eco-evolutionary outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Applied Evolutionary Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Sequencers | Platforms for determining the DNA sequence of entire genomes or targeted regions for many individuals. | Genotyping individuals to measure genetic variation, identify loci under selection (scans), and reconstruct pedigrees [6]. |

| SNP Arrays | Microarrays that allow for the genotyping of hundreds of thousands of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome. | Cost-effective genotyping for large-scale population genetic studies and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [10]. |

| Geographic Information Systems (GIS) | Software for capturing, storing, analyzing, and managing spatial or geographic data. | Creating and manipulating landscape maps for spatially-explicit models and analyzing spatial patterns of genetic variation [8]. |

| R Statistical Environment with Specialized Packages | A programming language and free software environment for statistical computing and graphics. | ggplot2: Creating publication-quality data visualizations [11]. adegenet/poppr: Population genetic analysis. vegan: Ecological community analysis. nlme/lme4: Fitting linear and generalized linear mixed-effects models. |

| Spatially-Explicit Individual-Based Modeling Platforms (e.g., HexSim) | Software designed to simulate the fate of individual organisms and their genes in complex, dynamic landscapes [8]. | Forecasting eco-evolutionary dynamics under different management or climate scenarios; testing classical assumptions of population genetics with realistic spatial structure [8]. |

| Molecular Lab Reagents | Kits and chemicals for DNA/RNA extraction, PCR, qPCR, and library preparation for sequencing. | Isolving genetic material from tissue samples for subsequent genotyping, gene expression analysis, or epigenotyping. |

| 3,8-Dimethylquinoxalin-6-amine | 3,8-Dimethylquinoxalin-6-amine|CAS 103139-99-7 | High-purity 3,8-Dimethylquinoxalin-6-amine for cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| N-(1-Benzhydrylazetidin-3-yl)acetamide | N-(1-Benzhydrylazetidin-3-yl)acetamide for Research | High-quality N-(1-Benzhydrylazetidin-3-yl)acetamide for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Phenotypes—the observable traits of an organism—constitute the direct interface through which natural selection operates, serving as the critical link between genotype and environment. In applied evolutionary biology research, understanding phenotypic expression and plasticity is paramount for deciphering how organisms adapt to changing environments, respond to selective pressures, and evolve novel functions. Unlike genotypes which represent potential, phenotypes represent the realized expression of this potential that is directly tested by environmental challenges. This article provides a comprehensive technical examination of phenotype-environment interactions, focusing on theoretical frameworks, quantitative assessment methodologies, and practical applications with particular relevance to biomedical and pharmaceutical research. We present a detailed analysis of how organisms employ diverse adaptation strategies—from unvarying specialists to sophisticated cue-tracking systems—and provide experimental protocols for quantifying these relationships in research settings.

Theoretical Framework: Environment-to-Phenotype Mapping

Biological organisms exhibit diverse strategies for adapting to varying environments, which can be formally conceptualized through an environment-to-phenotype mapping framework [12]. This mapping describes how organisms' traits or behaviors depend on environmental conditions, emphasizing an evolutionary rather than purely mechanistic understanding of organisms [12].

Adaptation Strategy Classifications

- Unvarying Strategy: Organisms express the same phenotype in all environments, typically favoring generalist traits suitable for most conditions [12]. Example: Birds with midsized beaks that can both catch insects and crack seeds [12].

- Tracking Strategy: Organisms follow environmental cues and express alternative phenotypes to match specific environmental conditions [12]. Example: Seasonal changes in butterfly wing patterns and mammal coat colors for camouflage [12].

- Bet-Hedging Strategy: A population diversifies into coexisting phenotypes to cope with environmental uncertainty [12]. Example: Seed banks where only a fraction of seeds germinate each season, ensuring some survive unpredictable conditions [12].

These strategies represent special cases within a continuum of possible adaptive responses, with the optimal strategy depending on environmental predictability, cue accuracy, and selection strength [12].

Mathematical Modeling of Phenotypic Response

The phenotypic response can be modeled as a function Φ that maps environmental cues ξ to phenotypic traits ϕ: ϕ = Φ(ξ) [12]. In a population dynamics framework, the population size in generation t+1 is given by:

N{t+1} = Nt × Σ{ξt} P(ξt | εt) f(Φ(ξt); εt)

where P(ξt | εt) is the probability of receiving cue ξt in environment εt, and f(Φ(ξt); εt) is the fitness function [12]. The long-term population growth rate Λ serves as the measure of evolutionary success:

Λ = Σμ pμ log[Σξ P(ξ | εμ) f(Φ(ξ); ε_μ)]

where pμ is the probability of environment εμ occurring [12].

Quantitative Assessment of Phenotypic Traits

Classification of Phenotypic Traits

Phenotypic traits are broadly categorized based on their measurement scale and underlying genetic architecture:

Table 1: Classification of Phenotypic Traits

| Trait Category | Definition | Population Distribution | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Traits | Discrete, categorical phenotypes | Discrete classes | Flower color, seed shape, morphological polymorphisms [13] |

| Quantitative Traits | Continuous phenotypic variation | Approximates normal distribution | Height, weight, blood pressure, aggression, gene expression levels [14] |

| Threshhold Traits | Discrete manifestation with continuous underlying liability | Binary outcome with continuous risk distribution | Disease susceptibility, developmental disorders [15] |

Genetic Architecture of Phenotypic Variation

Quantitative traits display continuous variation in populations due to genetic complexity and environmental sensitivity [14]. The continuous distribution arises from segregating alleles at multiple loci, each with relatively small effects on the trait phenotype, with expression sensitive to environmental conditions [14].

- Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) Mapping: QTL are genomic regions containing one or more genes that affect variation in a quantitative trait [14]. Mapping approaches include:

- Linkage Mapping: Tracing co-segregation of traits and markers in pedigrees or designed crosses [14]. Advantage: increased power from intermediate allele frequencies [14].

- Association Mapping: Detecting correlations between traits and markers in unrelated individuals from populations [14]. Advantage: increased mapping resolution due to historical recombination [14].

The power to detect a QTL depends on δ/σw, where δ is the difference in mean between marker classes, and σw is the standard deviation within each marker class [14]. For QTLs with moderate effects (δ/σw = 0.25), 500-1,000 individuals are typically required; for small effects (δ/σw = 0.0625), >10,000 individuals may be necessary [14].

Methodologies for Phenotypic Analysis

Experimental Designs for Phenotypic Assessment

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Phenotype Analysis

| Method | Application | Key Outputs | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| QTL Mapping | Identifying genomic regions associated with trait variation [16] | QTL positions, effect sizes, contribution to variance | Requires large sample sizes, precise phenotyping, dense genetic markers [14] |

| Reaction Norm Analysis | Quantifying phenotypic plasticity across environments [16] | Slope of reaction norm, G×E interaction effects | Requires multiple environments, controlled genetic backgrounds [16] |

| Multivariate Morphometrics | Characterizing complex phenotypic patterns [13] | Principal components, discriminant functions, covariance matrices | Captures correlated traits, requires careful measurement standardization [13] |

| Naive Bayes Classification | Computational phenotyping for syndrome identification [15] | Probability tables, classification accuracy, cluster assignments | Handles missing data, enables unsupervised pattern discovery [15] |

Protocol: QTL Mapping for Phenotypic Plasticity

This protocol details the detection of quantitative trait loci associated with phenotypic plasticity in plant-insect systems, adapted from the approach described by PMC (2011) [16].

Materials and Reagents

- Doubled haploid (DH) mapping population (150+ lines recommended)

- Genotyping platform (SNP chips, SSR markers, or sequencing-based)

- Controlled environment growth facilities

- Standardized soil and nutrient media

- DNA extraction kit (CTAB or commercial kit)

- Phenotyping equipment (digital calipers, scales, imaging systems)

Procedure

- Population Establishment: Plant 10-15 replicates of each DH line in randomized complete block design across multiple environments (e.g., varying rhizobacterial supplementation, pest exposure) [16].

- Phenotypic Measurement: Record quantitative traits (e.g., root/shoot biomass, aphid fitness measures) at appropriate developmental stages using standardized protocols [16].

- Genotype Data Collection: Extract DNA from leaf tissue and genotype with sufficient marker density (5-10 cM spacing ideal) [16].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Perform interval mapping using software such as R/qtl or QTL Cartographer

- Calculate logarithm of odds (LOD) scores genome-wide

- Establish significance thresholds via permutation tests (1,000 permutations)

- Test for QTL × environment interaction using appropriate linear models

- Plasticity QTL Mapping: Map the difference in mean trait values between environments as a separate trait to identify loci specifically associated with plasticity [16].

Data Analysis

The standard model for QTL mapping includes: y = μ + E + G + G×E + ε where y is the trait value, μ is the overall mean, E is the environment effect, G is the QTL genotype effect, G×E is the interaction term, and ε is the residual error [16].

Case Studies in Phenotypic Analysis

Phenotypic Diversity in Field Pea (Pisum sativum L.)

A comprehensive study of 85 field pea genotypes evaluated phenotypic diversity for qualitative and quantitative traits related to powdery mildew resistance and yield potential [13].

Table 3: Phenotypic Diversity and Powdery Mildew Resistance in Field Pea

| Trait Category | Specific Traits Measured | Diversity Index (H') | Correlations with Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Traits | Flower color, seed coat pattern, pod shape | 0.62-0.85 | Pod color associated with disease resistance |

| Growth and Architecture | Plant height, branching pattern, internode length | 0.71-0.89 | Positive correlation with yield (r=0.67) |

| Reproductive Traits | Pods per plant, seeds per pod, 100-seed weight | 0.75-0.92 | Strong positive correlation (r=0.74-0.81) |

| Disease Response | Powdery mildew susceptibility index | 0.68 | Negative correlation with yield (r=-0.59) |

Twelve genotypes showed extreme resistance to powdery mildew, 29 were resistant, 25 moderately resistant, 18 fairly susceptible, and 1 susceptible [13]. Cluster analysis using Mahalanobis distance identified five distinct groups, with the highest inter-cluster distance between clusters 2 and 3 (D²=11.89) and the lowest between clusters 3 and 4 (D²=2.06) [13]. Principal component analysis revealed the first four PCs with eigenvalues >1 accounted for 88.4% of total variability for quantitative traits [13].

Computational Phenotyping in Developmental Disorders

The Deciphering Developmental Disorders (DDD) study employed computational approaches to identify phenotypic patterns in 6,993 probands with whole-exome sequencing data [15]. Methodologies included:

- Median Euclidean Distance (mEuD): Calculated as the median pairwise Euclidean distance between growth z-scores (height, weight, occipital-frontal circumference) within gene-specific patient sets [15].

- Naive Bayes Classification: Unsupervised clustering of growth and developmental data defined 23 in silico syndromes (ISSs) using phenotypic data alone [15].

- HPO Term Similarity: Assessment of Human Phenotype Ontology term similarity within patient sets using information content metrics [15].

This phenotype-first approach successfully identified heterozygous de novo nonsynonymous variants in SPTBN2 as causative in three DDD probands, demonstrating the power of phenotypic pattern recognition for gene discovery [15].

Visualization of Phenotypic Concepts and Workflows

Environment-to-Phenotype Mapping Model

Figure 1: Environment-to-Phenotype Mapping Framework. This model illustrates the pathway from environmental signals through internal representation to phenotypic expression and fitness consequences [12].

QTL Mapping Workflow for Phenotypic Plasticity

Figure 2: QTL Mapping Workflow for Phenotypic Plasticity. Experimental design for detecting genotype-by-environment interactions and plasticity-specific QTL [16].

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for Phenotypic Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mapping Populations | Doubled haploid lines, Recombinant inbred lines (RILs), Advanced intercross lines [16] | Genetic mapping of trait architecture | Homozygosity simplifies analysis, historical recombination improves resolution [16] |

| Genotyping Platforms | SNP arrays, Whole-genome sequencing, RAD-seq | Genotype-phenotype association studies | Marker density must be sufficient for population-specific LD patterns [14] |

| Phenotyping Systems | Automated image analysis, High-throughput phenotyping platforms, Environmental control systems | Quantitative trait measurement | Standardization critical for multi-environment trials [13] |

| Ontology Resources | Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO), Plant Ontology Project, Animal trait ontology [15] | Standardized phenotype description | Enables computational analysis and cross-study comparisons [15] |

| Statistical Packages | R/qtl, TASSEL, PLINK, Naive Bayes classifiers [15] [14] | Genetic analysis and pattern recognition | Method selection depends on experimental design and trait distribution [14] |

Phenotypes represent the fundamental interface through which organisms interact with their environments, and precise characterization of phenotype-environment relationships enables advances across evolutionary biology, agriculture, and medicine. The framework of environment-to-phenotype mapping provides a unifying conceptual structure for understanding diverse adaptation strategies, from unvarying specialists to sophisticated cue-tracking systems [12]. Quantitative genetic approaches, particularly QTL mapping and reaction norm analysis, allow researchers to dissect the genetic architecture underlying phenotypic variation and plasticity [16] [14]. Emerging computational methods, including naive Bayes classification and multivariate distance metrics, further enhance our ability to identify subtle phenotypic patterns and their genetic correlates [15]. For applied researchers in drug development and biomedical sciences, these approaches offer powerful tools for understanding host-pathogen interactions, identifying genetic determinants of disease susceptibility, and developing interventions that account for phenotypic plasticity in evolving biological systems.

The evolutionary mismatch concept provides a powerful framework for understanding how traits that were once advantageous or neutral can become maladaptive in novel environments. This principle is critically relevant to human health, explaining the rise of non-communicable diseases in industrialized populations, and to pathogen evolution, particularly in the context of antimicrobial resistance. This whitepaper synthesizes the current scientific understanding of mismatch phenomena, detailing the underlying mechanisms, methodological approaches for its study, and implications for therapeutic development. We present a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, integrating evolutionary theory with empirical research protocols to advance the application of evolutionary principles in biomedical science.

Evolutionary mismatch describes a state of disequilibrium that arises when an organism possesses traits adapted to a previous environment that become maladaptive in a new environment [3]. This concept, central to applied evolutionary biology, explains numerous modern health challenges by recognizing the lag between environmental change and biological adaptation. The fundamental premise is that many contemporary human ailments and pathogen survival strategies represent mismatches between evolved biological systems and rapidly altered environments.

The theoretical foundation of mismatch originates from the broader concept of "adaptive lag" in evolutionary theory [17]. While natural selection gradually optimizes organisms for their environments, large-scale environmental changes can outpace this adaptive process. In contemporary research, mismatch is understood to operate across multiple timescales—from evolutionary changes over generations to developmental adjustments within a single lifespan [17]. This multi-scale perspective is essential for a comprehensive understanding of how organisms track environmental changes and why these tracking mechanisms sometimes fail.

For human health, mismatch explains the high prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and autoimmune disorders in industrial populations [18]. Similarly, in pathogens, mismatch principles illuminate how antimicrobial resistance emerges when drug pressures create environments radically different from those in which the pathogens evolved. Understanding these dynamics provides critical insights for developing more effective therapeutic interventions and public health strategies.

Theoretical Framework and Definitions

Core Concepts and Terminology

The study of evolutionary mismatch requires precise operational definitions of key concepts:

Evolutionary Mismatch: A phenomenon whereby previously adaptive or neutral traits are no longer favored in a new environment, resulting in detrimental effects on fitness or well-being [1] [3]. This occurs when the timescale and/or magnitude of environmental change exceeds the combined capacity of adaptation through homeostatic mechanisms, phenotypic plasticity, and transgenerational adaptation [17].

Ancestral Environment (E1): The historical environment to which an organism's traits were adapted. For humans, this typically refers to the environments experienced by hunter-gatherer societies before the Neolithic Revolution [2] [3].

Novel Environment (E2): The current environment that differs significantly from the ancestral environment, rendering previously adapted traits maladaptive [3]. Modern industrialized environments represent E2 for most human mismatch studies.

Developmental Mismatch: Distinct from evolutionary mismatch, this occurs when environmental conditions during development program physiological responses that become maladaptive later in life if environmental conditions change [17]. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis, which proposes that fetal undernutrition leads to metabolic adaptations that increase disease risk in nutritionally abundant environments, exemplifies this concept [17].

Modes of Adaptation and Mismatch

Organisms employ multiple modes of adaptation to track environmental changes across different timescales [17]:

Table: Modes of Biological Adaptation and Their Timescales

| Mode of Adaptation | Timescale | Mechanism | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homeostasis | Seconds to minutes | Physiological regulation | Blood glucose regulation |

| Allostasis | Hours to days | Physiological adjustment | Stress response system activation |

| Developmental Plasticity | In utero to childhood | Phenotypic programming | Birth weight adjustment to maternal nutrition |

| Cultural Evolution | Years to centuries | Cultural transmission & innovation | Dietary practices and food technologies |

| Genetic Evolution | Generations to millennia | Natural selection on genes | Lactose persistence in pastoralist populations |

Failure in any of these adaptive modes can lead to mismatch. The integrative theory of mismatch captures how organisms track environments across space and time on multiple scales to maintain an adaptive match, and how failures of this tracking lead to disease [17].

Mismatch in Human Health and Disease

Metabolic Diseases: Thrifty Genotype and Phenotype

The thrifty genotype hypothesis, first proposed by Neel [17], suggests that genes promoting efficient fat storage were advantageous in ancestral environments with periodic food scarcity but predispose to obesity and type 2 diabetes in modern environments with constant caloric abundance [2] [1]. This genetic predisposition, combined with sedentary lifestyles and energy-dense diets, creates a fundamental evolutionary mismatch explaining the global rise of metabolic syndrome.

Complementing this, the thrifty phenotype hypothesis proposes that developmental mismatch contributes to metabolic disease. When fetal development occurs under conditions of poor maternal nutrition, the developing organism makes physiological adaptations that optimize metabolic function for a resource-poor environment. If the actual postnatal environment is nutritionally abundant, these adaptations become maladaptive, increasing risk for obesity, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease [17].

Immune Function and the Hygiene Hypothesis

The hygiene hypothesis (sometimes termed "biome depletion theory") represents another critical mismatch phenomenon in human health [2]. Human immune systems evolved in pathogen-rich environments, constantly challenged by diverse microorganisms including helminthic worms. Modern hygiene practices, antibiotics, and sanitized environments have drastically reduced exposure to these immunomodulatory organisms.

This environmental shift has created a mismatch wherein immune systems adapted for robust pathogen defense now operate in an environment lacking sufficient microbial input, leading to improper immune regulation. The result is an increased prevalence of allergic, autoimmune, and inflammatory disorders in industrialized populations [2] [1]. This mismatch framework has inspired novel therapeutic approaches, including helminthic therapy that deliberately reintroduces controlled helminth infections to recalibrate immune function [1].

Musculoskeletal and Behavioral Health

Osteoporosis represents another mismatch condition prevalent in modern sedentary populations. Fossil evidence indicates that hunter-gatherer women rarely developed osteoporosis, likely due to high levels of physical activity throughout life leading to greater peak bone mass [2]. The sedentary nature of modern industrial lifestyles fails to provide the mechanical loading necessary to maintain optimal bone density, creating a mismatch between evolved skeletal maintenance mechanisms and contemporary activity patterns.

Behavioral and psychological mismatches are equally significant. Human reward systems evolved to reinforce behaviors essential for survival and reproduction in ancestral environments (e.g., seeking high-calorie foods). In modern environments, these same systems can be exploited by hyperpalatable foods, drugs, and gambling, leading to addiction [2]. Similarly, anxiety systems that evolved to respond to immediate physical threats may become maladaptive when triggered by abstract or chronic stressors in modern life [2].

Table: Examples of Evolutionary Mismatch in Human Health

| Condition | Ancestral Benefit (E1) | Modern Detriment (E2) | Environmental Shift |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity & Type 2 Diabetes | Efficient energy storage during feast-famine cycles | Pathological fat accumulation, insulin resistance | Constant caloric abundance, reduced energy expenditure |

| Autoimmune & Allergic Disorders | Robust immune response to diverse pathogens | Inappropriate inflammation, autoimmunity | Reduced pathogen exposure, altered microbiome |

| Osteoporosis | High bone density from lifelong physical activity | Fracture risk during aging | Sedentary lifestyle, reduced mechanical loading |

| Anxiety Disorders | Rapid response to immediate physical threats | Chronic anxiety without resolution | Abstract, chronic psychosocial stressors |

| Addiction | Appropriate pursuit of rewards (food, social status) | Maladaptive overconsumption | Hyper-stimulating rewards (drugs, gambling, hyperpalatable foods) |

Mismatch in Pathogen Evolution and Antimicrobial Resistance

While the search results focus primarily on human health applications, the mismatch principle provides equally powerful insights into pathogen evolution and antimicrobial resistance. From an evolutionary perspective, pathogens experience radical environmental shifts when encountering antimicrobial drugs, creating strong selection pressures that can lead to resistance through multiple mechanisms.

Antibiotic Exposure as Environmental Mismatch

For pathogens, the pre-antibiotic environment (E1) represented an evolutionary context where resistance mechanisms provided little selective advantage. The introduction of antimicrobial agents created a novel environment (E2) where previously neutral or slightly costly resistance mechanisms became highly advantageous. This represents a classic evolutionary mismatch from the pathogen perspective.

The rapid evolution of resistance illustrates several key mismatch concepts:

- Directional selection favors previously rare resistance alleles

- Stabilizing selection maintains core pathogen functions while accommodating resistance mechanisms

- Evolutionary trade-offs between resistance and fitness in the absence of drugs can create opportunities for evolutionary interventions

Research Approaches for Pathogen Mismatch

Studying mismatch in pathogens requires complementary approaches to human research:

- Comparative genomics of pre- and post-antibiotic era isolates identifies selection signatures

- Experimental evolution tracks adaptive trajectories in controlled environments

- Pharmaco-ecology examines how drug exposure creates novel selection landscapes

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Genotype-by-Environment (GxE) Interaction Studies

The evolutionary mismatch framework predicts that loci with a history of selection will exhibit genotype-by-environment (GxE) interactions, with different health effects in ancestral versus modern environments [18]. Detecting these interactions requires specific methodological approaches:

Protocol 1: GxE Mapping in Transitional Populations

- Population Selection: Partner with subsistence-level populations experiencing rapid lifestyle change, creating a natural experiment of environmental transition [18]

- Environmental Metrics: Quantify modernization using continuous variables (e.g., dietary composition, physical activity levels, microbiome diversity) rather than binary classifications

- Genomic Data Collection: Perform genome-wide sequencing or genotyping with particular attention to loci with signatures of positive selection

- Phenotypic Assessment: Measure relevant health outcomes (e.g., glucose tolerance, inflammatory markers, body composition)

- Interaction Testing: Implement statistical models that explicitly test for GxE interactions while controlling for population structure and related covariates

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Mismatch Hypotheses

- Candidate Gene Selection: Identify genetic variants with known metabolic functions and evidence of historical selection

- In Vitro Modeling: Create cell culture systems (e.g., hepatocytes, adipocytes) with different genetic backgrounds

- Environmental Manipulation: Expose cells to nutrient conditions mimicking ancestral (varied, fasting-refeeding cycles) versus modern (constant high energy) environments

- Outcome Measurement: Assess metabolic outputs (e.g., glucose uptake, lipid accumulation, mitochondrial function)

- Pathway Analysis: Evaluate signaling pathways that show differential activation across environments

Comparative Physiological Studies

Protocol 3: Cross-Population Metabolic Comparison

- Cohort Establishment: Recruit matched participants from populations representing different positions on the modernization spectrum (e.g., urban industrial, rural transitional, subsistence-level)

- Metabolic Assessment: Conduct detailed metabolic phenotyping including:

- Oral glucose tolerance tests

- Doubly labeled water measurements of energy expenditure

- Stable isotope assessments of macronutrient metabolism

- Environmental Exposure Quantification: Document dietary patterns, physical activity, microbiome composition, and other relevant environmental factors

- Data Integration: Analyze how physiological responses correlate with environmental exposures across populations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Mismatch Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Arrays | Genome-wide association studies | Illumina Global Screening Array, Infinium MethylationEPIC Kit |

| Metabolomics Kits | Comprehensive metabolic profiling | Biocrates AbsoluteIDQ p400 HR Kit, Cell-based metabolic flux assays |

| Microbiome Analysis | Gut microbiota characterization | 16S rRNA sequencing primers, Shotgun metagenomics kits |

| Immune Profiling | Inflammatory marker quantification | Multiplex cytokine panels (Luminex), Flow cytometry antibody panels |

| Environmental Sensors | Objective activity and exposure measurement | Accelerometers, GPS loggers, Personal air pollution monitors |

| Dietary Assessment | Nutritional intake quantification | Food frequency questionnaires, Metabolic kitchen equipment |

| 4-(Pyrrolidin-2-yl)pyrimidine | 4-(Pyrrolidin-2-yl)pyrimidine|High-Purity Research Chemical | |

| 1,5-Bis(6-methyl-4-pyrimidyl)carbazone | 1,5-Bis(6-methyl-4-pyrimidyl)carbazone|CAS 102430-61-5 | 1,5-Bis(6-methyl-4-pyrimidyl)carbazone for research. This chemical is For Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. |

Data Presentation and Analysis Frameworks

Criteria for Establishing Evolutionary Mismatch

Rigorous demonstration of evolutionary mismatch requires satisfying three key criteria [18]:

Prevalence Difference: The proposed mismatch condition must be more common or severe in the novel environment compared to the ancestral environment (or correlate with continuous metrics of modernization)

Environmental Correlation: The condition must be tied to specific environmental variables that differ between ancestral and novel environments

Mechanistic Explanation: A molecular or physiological mechanism must explain how the environmental shift generates the mismatch condition

At the genetic level, this manifests as loci showing past history of positive selection with health benefits in the ancestral environment but health detriments in the novel environment, or loci where past stabilizing selection created intermediate alleles with similar fitness in the ancestral environment but differential effects in the novel environment [18].

Quantitative Assessment of Mismatch Effects

Table: Statistical Approaches for Mismatch Research

| Analysis Type | Application | Key Outputs | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GxE Interaction Testing | Identifying genetic variants with environment-dependent effects | Interaction p-values, β coefficients for GxE terms | Requires large sample sizes, careful environmental measurement |

| Mediation Analysis | Dissecting causal pathways between environment and health | Direct and indirect effect estimates | Assumes no unmeasured confounding |

| Polygenic Risk Scoring | Assessing cumulative genetic susceptibility | PRS-by-environment interaction effects | Population-specific PRS calibration needed |

| Metabolome-Wide Association | Linking metabolic profiles to mismatch conditions | Altered metabolic pathways, biomarker identification | Integration with genomic data strengthens causal inference |

| Microbiome-Host Interaction | Characterizing host-genome dependent microbiome effects | Variance explained by host genetics, microbiome-mediated health effects | Confounding by diet and environment must be controlled |

The evolutionary mismatch principle provides a powerful unifying framework for understanding diverse challenges in human health and pathogen evolution. By systematically examining how traits evolved in ancestral environments function in contemporary contexts, researchers can identify fundamental mechanisms underlying disease etiology and progression.

Future research directions should prioritize:

- Longitudinal studies in transitioning populations to directly observe mismatch processes as they unfold

- Integration of multi-omics data to comprehensively map pathways from genetic variation to phenotypic outcomes across environments

- Development of mismatch-informed interventions that either reverse environmental mismatches or modulate biological responses to them

- Application to antimicrobial resistance through evolutionary-based drug development and treatment strategies

For drug development professionals, the mismatch framework offers novel approaches for target identification, patient stratification, and clinical trial design that account for evolutionary history and environmental context. Similarly, for pathogen control, it suggests evolution-informed strategies that anticipate resistance development and mitigate its impact.

The continued refinement and application of mismatch principles will enhance our ability to address both longstanding and emerging health challenges through the integrated perspective of evolutionary medicine.

The field of evolutionary biology has traditionally been associated with change over vast, geological timescales. However, a paradigm shift has established that substantial evolutionary change can occur rapidly within ecologically relevant timeframes—contemporaneously with ecological dynamics such as population fluctuations and community interactions. This phenomenon, termed contemporary evolution, demonstrates that genetic and phenotypic changes can be both a cause and consequence of ecological change, creating dynamic feedback loops [19]. The foundational theory for this field stems from population genetics, a mature discipline that provides a rigorous, quantitative framework for understanding how forces like natural selection, genetic drift, migration, and mutation shape genetic variation within and between populations over time [20]. The recognition that evolution is a quantitative science, built on axiomatic biological foundations capable of precise mathematical formulation, is crucial for researching these rapid changes [20].

This synthesis is particularly relevant for applied evolutionary biology research, where understanding the pace and drivers of adaptation is essential. For researchers and drug development professionals, these principles are invaluable, whether tracking the evolution of pathogen resistance, understanding host-pathogen coevolution, or leveraging evolutionary models to identify selectively constrained genomic regions as drug targets.

Theoretical Foundations and Quantitative Frameworks

The neo-Darwinian synthesis reconciled Darwin's vision of gradual evolution through natural selection with Mendelian genetics by considering the effect of selection on variations in Mendelian genes [20]. The standard model for predicting the rate of directional evolutionary change in a trait mean is encapsulated by the Lande equation, which describes how selection acts on heritable variation:

dz/dt = h²v² (∂W/∂z)

Here, dz/dt is the rate of change in the mean of trait z per unit time, h² is the narrow-sense heritability, v² is the additive genetic variance, and ∂W/∂z is the fitness gradient representing the strength of selection [19].

To link evolutionary rates directly to concurrent ecological change (specifically, changes in population size), this equation can be reframed. By substituting the definition of mean fitness W as the per capita population growth rate, (1/N)(dN/dt), the relationship becomes:

(1/z)(dz/dt) = [ h²v² / z * (∂logW)/∂z ] * (1/N)(dN/dt)

This formulation reveals that the ratio of the rate of phenotypic change to the rate of population change is determined by the fraction of heritable variation and the relative fitness gradient [19]. This provides a theoretical basis for comparing the pace of evolutionary and ecological change across different systems and traits.

Empirical Evidence and Rates of Change

A key question in contemporary evolution is how the speed of phenotypic change compares to the speed of ecological change. A comparative analysis of standardized rates across a wide range of species and taxonomic groups provides a quantitative answer.

Table 1: Standardized Rates of Phenotypic and Population Change Across Studies

| Species | Trait | Taxonomic Group | Rate of Population Change (1/N dN/dt) | Rate of Phenotypic Change (1/z dz/dt) | Ratio (Phenotypic:Population) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brachionus calyciflorus | Propensity for mixis | Rotifer (R) | Data from source | Data from source | Calculated |

| Marmota flaviventris | Body mass | Mammal (M) | Data from source | Data from source | Calculated |

| Petrochelidon pyrrhonota | Wing length | Bird (B) | Data from source | Data from source | Calculated |

| Ovis canadensis | Horn length | Mammal (M) | Data from source | Data from source | Calculated |

| Homo sapiens | Age first reproduction | Mammal (M) | Data from source | Data from source | Calculated |

Note: This table is a template. The specific rate values for each study, which were not fully detailed in the search results, would need to be populated from the original source, [19].

The analysis of this data reveals several critical patterns. First, rates of phenotypic change are generally slower than concurrent rates of population change; they are typically no more than two-thirds, and on average about one-fourth, the rate of population change [19]. This suggests that while evolution operates on ecological timescales, populations rarely change as fast in their traits as they do in their abundance. Second, there is no consistent relationship between rates of population change and rates of phenotypic change across different biological systems. A system with fast population dynamics is not necessarily a system with fast evolutionary dynamics [19]. Finally, the variance of both phenotypic and ecological rates increases with the mean following a power law, but temporal variation in phenotypic rates is lower than in ecological rates [19].

Methodological Approaches for Studying Contemporary Evolution

Research in contemporary evolution relies on a suite of modern methodological approaches that combine genomic tools, longitudinal field studies, and controlled experiments.

Genomic Analysis of Population Structure and Demography

As demonstrated in a study on the shrub Sophora moorcroftiana, researchers can investigate patterns of local adaptation by analyzing population genomic data from multiple populations across environmental gradients [21]. The standard workflow is as follows:

- Sample Collection & Sequencing: Collect tissue samples (e.g., leaves) from multiple individuals across many populations spanning different environmental conditions (e.g., altitude). Perform Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) or whole-genome sequencing to generate genomic data [21].

- Variant Calling: Align sequence data to a reference genome and identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to serve as genetic markers [21].

- Population Genetic Analysis:

- Structure: Use programs like STRUCTURE or ADMIXTURE to identify distinct genetic subpopulations and visualize their distribution [21].

- Genetic Diversity & Differentiation: Calculate statistics like nucleotide diversity (Pi) and genetic differentiation (Fst) to compare genetic variation within and between populations [21].

- Demographic History: Apply models like SMC++ to infer historical population sizes, identifying past bottlenecks, expansions, and the timing of these events [21].

- Testing Drivers of Genetic Variation: Conduct partial Mantel tests to disentangle the effects of geographic distance (Isolation by Distance) and environmental difference (Isolation by Environment) on genetic variation [21].

- Genotype-Environment Association (GEA) Analysis: Use methods like BayPass or LFMM to identify specific SNPs that are significantly associated with environmental variables, pinpointing candidate genes for local adaptation [21].

Research Workflow for Genomic Analysis of Local Adaptation

Individual-Based Modeling (IBM)

Individual-Based Modeling is a powerful tool for dissecting the complex interplay between individual variation, population dynamics, and evolution. It allows researchers to test how different mechanisms (e.g., genetic rules, plasticity) influence observed outcomes. A protocol based on soil mite (Sancassania berlesei) studies involves [22]:

- Purpose & Scope: Define the model's goal: to explore how phenotypic and genetic variation influence population dynamics.

- Agent State Variables: Each individual agent is defined by its state variables: size (

Si), age (Ai), reserves (Ri), maturation status, and a set of eight "genetic" rules governing resource allocation [22]. - Process Overview & Scheduling: The model runs in daily time steps. The sequence is: a) Food is supplied; b) Food is competitively shared among individuals; c) Individuals allocate food according to their genetic rules to growth, reserves, or reproduction; d) Maturation and survival are determined probabilistically; e) State variables are updated [22].

- Design Concepts:

- Emergence: Population-level dynamics (abundance, trait distribution) emerge from individual-level rules and interactions.

- Stochasticity: Incorporate stochasticity in food supply, maturation decisions, and survival to reflect realistic environmental variation [22].

- Initialization & Input: Initialize the model with a population of individuals with random genetic values. Define environmental input, such as constant or variable food supply regimes [22].

- Simulation Experiments: Run simulations under different scenarios (e.g., fixed phenotypes, plastic variation only, full genetic and plastic variation) to isolate the dynamical importance of different types of variation [22].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Contemporary Evolution

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | A high-quality, assembled genome sequence for a species. | Serves as a scaffold for aligning sequencing reads and calling genetic variants like SNPs. Essential for GEA studies [21]. |

| GBS (Genotyping-by-Sequencing) Kit | A protocol for efficiently discovering and genotyping thousands of SNPs across many individuals. | Provides the raw genomic data for population structure, demographic history, and selection scans without the cost of whole-genome sequencing [21]. |

| SNP Array | A microarray designed to genotype a predefined set of SNPs across the genome. | A cost-effective alternative to sequencing for genotyping many individuals at known, variable sites in well-studied organisms. |

| Environmental Data Layers | Geospatial data on variables like temperature, precipitation, and UV radiation. | Used in GEA analysis to test for correlations between allele frequencies and environmental gradients, identifying local adaptation [21]. |

| Individual-Based Model (IBM) Platform | Software frameworks (e.g., coded in R) for simulating individual agents with inherited traits. | Used to test hypotheses about how individual-level processes (growth, reproduction) give rise to population-level eco-evolutionary dynamics [22]. |

The evidence is clear that evolution can proceed on ecological timescales, acting as a contemporary force that can interact with and alter ecological dynamics. The principles of applied evolutionary biology research—rooted in quantitative population genetic theory and empowered by modern genomic tools—provide a robust framework for measuring, understanding, and predicting this rapid change. For scientists and drug development professionals, integrating this evolutionary perspective is no longer optional but essential. It allows for forecasting the evolution of resistance, understanding the genetic basis of adaptation in pathogens and hosts, and managing populations of conservation or economic concern in the face of rapid environmental change. Future progress will hinge on the continued integration of genomic data, sophisticated statistical models, and experimental manipulations across diverse biological systems.

Harnessing Evolutionary Principles in the Drug Discovery Pipeline

The process of drug discovery bears a profound resemblance to biological evolution, a concept that provides a powerful framework for understanding the selection and optimization of therapeutic molecules. In nature, evolution operates through the generation of genetic variation within a population, followed by the selective pressure of the environment, leading to the survival and reproduction of the fittest individuals. Similarly, in drug discovery, researchers create vast molecular libraries containing immense chemical diversity, which then undergo rigorous selection pressure through screening assays to identify the rare variants possessing the desired therapeutic properties. This evolutionary analogy extends to the terminology used in pharmacology, which echoes the taxonomic classification of flora and fauna, and to the development pathway where candidate molecules are described in generations, with each iteration representing a step toward optimized function and fitness for their biological niche [23].

The parallels run deep: both processes feature tremendous attrition rates, with only a minute fraction of initial variants surviving the selection process. Between 1958 and 1982, for instance, the National Cancer Institute screened approximately 340,000 natural products for biological activity, yet only a handful yielded viable drug candidates [23]. A major pharmaceutical company may maintain a library of over 2 million compounds available for screening, yet the journey from this vast chemical diversity to a single approved medicine represents an extreme selective bottleneck [23]. This evolutionary perspective not only provides a conceptual framework for understanding drug discovery but may also offer practical insights for improving its efficiency and success rates by applying evolutionary first principles to molecular design and selection strategies.

The Evolutionary Drug Discovery Workflow

The drug discovery process mirrors evolutionary mechanisms through iterative cycles of variation, selection, and replication. The diagram below illustrates this parallel workflow, highlighting how each stage in conventional drug discovery corresponds to a fundamental evolutionary process.

Molecular Library Generation (Variation)

The initial variation phase in drug discovery involves creating extensive molecular libraries that serve as the population from which candidates will be selected. Modern approaches include:

- Combinatorial Chemistry: Automated synthesis techniques that systematically create large collections of related compounds through different combinations of chemical building blocks [24].

- Natural Product Screening: Examination of compounds derived from microbial, marine, and plant sources, which offer evolved biological activity honed by natural selection [23].

- Virtual Compound Generation: Using generative AI and computational models to create novel molecular structures in silico before synthesis. For example, deep graph networks were used to generate 26,000+ virtual analogs in a 2025 study, resulting in sub-nanomolar inhibitors with dramatic potency improvements [25].

High-Throughput Screening (Selection)

Screening represents the selection pressure phase, where molecular libraries undergo biological testing to identify "fit" candidates. Key methodologies include:

- Target-Based Screening: Tests compounds against isolated biological targets (e.g., proteins, enzymes) to identify binders [24].

- Phenotypic Screening: Assesses compound effects in cells or tissues, selecting for functional outcomes rather than specific target binding [26].

- AI-Enhanced Screening: Machine learning models predict compound activity before experimental testing, dramatically improving efficiency. Recent work demonstrated that integrating pharmacophoric features with protein-ligand interaction data can boost hit enrichment rates by more than 50-fold compared to traditional methods [25].

Hit-to-Lead Optimization (Iteration)

Successful hits undergo iterative optimization through design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycles, analogous to generational improvement in evolution:

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies: Systematic modification of chemical structures to establish correlations between structure and biological activity [24].

- AI-Guided Optimization: Algorithms propose structural modifications to improve potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties. Companies like Exscientia report 70% faster design cycles requiring 10x fewer synthesized compounds than industry norms [26].

- Multi-Parameter Optimization: Simultaneous improvement of multiple drug properties, acknowledging that therapeutic fitness depends on balancing various characteristics [24].

Quantitative Landscape of Molecular Libraries and Screening

The scale of molecular exploration in drug discovery has expanded dramatically, with both physical and virtual libraries growing exponentially. The table below summarizes key quantitative aspects of modern molecular library screening and selection.

Table 1: Scale and Success Metrics in Evolutionary Drug Discovery

| Parameter | Historical Scale | Current Scale (2025) | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | 180,000 microbial products (1958-1982) [23] | 2M+ compounds in pharma libraries [23] | N/A |

| Screening Capacity | Manual/low-throughput assays | 100,000+ compounds/day via HTS [24] | ~0.01% hit rate [24] |

| Hit-to-Lead Time | 12-18 months | Weeks to months with AI [25] | 50-70% attrition [25] |

| AI-Accelerated Discovery | N/A | 75+ AI-derived molecules in clinical trials [26] | 136 compounds to candidate (vs. 1000s traditionally) [26] |

The implementation of artificial intelligence has particularly transformed the efficiency of molecular selection. For instance, in one program examining a CDK7 inhibitor, a clinical candidate was achieved after synthesizing only 136 compounds, whereas traditional programs often require thousands [26]. This represents a significant compression of the evolutionary timeline, enabling more rapid iteration and selection of fitter molecular candidates.

Experimental Protocols for Evolutionary Drug Discovery

Protocol 1: Ligand-Based Similarity Screening

Ligand-based drug design operates on the evolutionary principle that structurally similar molecules likely share biological properties, analogous to the inheritance of traits in biology [24].

Principle: The "chemical similarity principle" assumes that if two molecules share similar structures, they will likely have similar biological properties, enabling the identification of improved variants from known active compounds [24].

Methodology:

- Query Compound Selection: Begin with a compound demonstrating desired biological activity (the "fit" parent).

- Chemical Fingerprint Generation: Convert molecular structure into a mathematical representation using:

- Path-based fingerprints (e.g., Daylight fingerprints): Enumerate potential paths at different bond lengths in the molecular graph

- Substructure-based fingerprints (e.g., MACCS keys): Encode presence/absence of predefined substructures using binary arrays [24]

- Similarity Searching: Calculate Tanimoto similarity index against compound database: