A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Causal Gene Knockout Models: From AI Discovery to Experimental Confirmation

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating causal gene knockout models, a critical step in functional genomics and therapeutic target discovery.

A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Causal Gene Knockout Models: From AI Discovery to Experimental Confirmation

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating causal gene knockout models, a critical step in functional genomics and therapeutic target discovery. It covers the foundational principles of causal gene identification, explores cutting-edge machine learning and CRISPR-based methodological pipelines, details troubleshooting and optimization strategies for efficient editing, and establishes robust multi-level validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest advances in computational prediction and experimental confirmation, this resource aims to enhance the accuracy, efficiency, and reliability of gene function validation in biomedical research.

The Foundation of Causal Gene Validation: From Computational Prediction to Biological Causality

A fundamental challenge in functional genomics lies in distinguishing mere correlative observations from definitive causal understanding of gene function in vivo [1]. While transcriptomic studies have cataloged extensive RNA expression dynamics across biological processes and disease states, establishing causative roles for these molecules remains elusive for the vast majority [1]. This gap is particularly problematic in drug discovery, where targets with genuine genetic support demonstrate substantially higher success rates—yet identifying these true causal genes remains methodologically challenging [2] [3]. The traditional assumption that a single causal variant explains most of a genetic association signal is increasingly being questioned, with emerging evidence suggesting that even single association signals may involve multiple functional variants in strong linkage disequilibrium, each contributing to the observed genetic association [4].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of contemporary methodologies for defining causal genes, evaluating their experimental requirements, performance characteristics, and applicability to drug discovery pipelines. We move beyond theoretical discussion to present quantitative performance data and detailed protocols that researchers can directly implement in their validation workflows.

Methodological Landscape: Approaches for Causal Gene Identification

Multiple computational and experimental frameworks have been developed to address the correlation-to-causation gap in gene identification. The table below compares the primary approaches used in current research.

Table 1: Methodological Approaches for Causal Gene Identification

| Method Category | Key Features | Typical Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Integration | Combines multiple algorithms (e.g., Stepglm, Random Forest) to identify diagnostic biomarkers [5] | Disease biomarker discovery, diagnostic model development [5] | High predictive accuracy (AUC up to 0.976), robust cross-validation performance [5] | Model complexity, requires large training datasets |

| Genetic Prioritization Scores | Uses genetic associations across allele frequency spectrum to prioritize causal genes [2] [3] | Drug target prioritization, direction-of-effect prediction [3] | Associated with clinical trial success, predicts direction of therapeutic effect [3] | Limited by GWAS design, population-specific biases |

| Causal Inference Frameworks | Integrates network analysis with statistical mediation to identify causally linked genes [6] | Complex disease target identification, understanding disease mechanisms [6] | Identifies driver genes rather than secondary effects, adjusts for confounders [6] | Computationally intensive, requires careful confounding adjustment |

| 3D Multi-omics | Maps genome folding with regulatory elements to link non-coding variants to target genes [7] | Interpreting non-coding GWAS variants, identifying regulatory networks [7] | Directly maps physical gene-regulatory relationships, overcomes nearest-gene limitations [7] | Experimentally complex, requires specialized assays |

| Functional Validation Toolkit | Uses CRISPR/Cas9, viral vectors for direct in vivo validation of gene function [1] | Direct causal validation, mechanistic studies [1] | Provides definitive evidence of causal function, establishes mechanism [1] | Low throughput, technically challenging, species-specific considerations |

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Benchmarking of Causal Gene Methods

Diagnostic Accuracy and Clinical Predictive Value

Rigorous benchmarking of causal gene prioritization methods against therapeutic outcomes provides critical insight into their real-world performance. The following table summarizes quantitative performance metrics across multiple methodologies.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Causal Gene Identification Methods

| Method | Dataset/Context | Performance Metrics | Clinical/Therapeutic Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (13-algorithm ensemble) | Endometriosis diagnostic biomarkers [5] | Training set AUC: 0.962; 10-fold CV mean AUC: 0.975 [5] | High discriminative power for disease diagnosis |

| Nearest Gene Method | Drug clinical trial outcomes [2] | Odds Ratio for drug approval: 3.08 (CI: 2.25-4.11) [2] | Predictive of clinical trial success |

| L2G Score (Machine Learning) | Drug clinical trial outcomes [2] | Odds Ratio for drug approval: 3.14 (CI: 2.31-4.28) [2] | Similar to nearest gene method for trial prediction |

| eQTL Colocalization | Drug clinical trial outcomes (without nearest genes) [2] | Odds Ratio for drug approval: 0.33 (CI: 0.05-2.41) [2] | Poor independent predictive value for approval |

| Direction-of-Effect Prediction | Gene-disease pairs with genetic evidence [3] | Macro-averaged AUROC: 0.59-0.85 depending on evidence [3] | Informs therapeutic activation vs. inhibition |

| Decision Tree Marker Pairs | Neuronal senescence identification [8] | Accuracy: 99%, Sensitivity: 83%, Specificity: 100% [8] | High accuracy for cellular state classification |

Genetic Data Integration Frameworks

The scale of modern genetic datasets requires specialized computational infrastructure. Genetic data lakes have emerged as a solution, enabling efficient storage and analysis of GWAS, molecular quantitative trait loci (mQTL), and epigenetic data within a unified big data infrastructure [9]. One such implementation prioritized 54,586 gene-trait associations—including 34,779 found exclusively in consortium datasets—and completed 1,373,376 Mendelian randomization analyses in under two minutes, demonstrating the power of scalable genetic data architecture for accelerating target discovery [9].

Experimental Protocols: Detailed Methodologies for Causal Gene Validation

Machine Learning Ensemble Approach for Diagnostic Biomarkers

Protocol Overview: This methodology integrates multiple machine learning algorithms to identify robust diagnostic biomarkers with causal implications [5].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Obtain transcriptomic datasets from public repositories (e.g., GEO). For endometriosis research, the GSE141549 dataset (179 cases, 43 controls) served as training data, with validation across GSE7305, GSE23339, and GSE25628 series [5].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Perform comprehensive differential analysis using Bayesian models (limma package, version 3.50.0) with strict criteria: absolute log-fold change >1.5 and FDR-adjusted p-value <0.05 [5].

- Feature Intersection: Identify differentially expressed genes overlapping with predefined biologically relevant gene sets (e.g., 271 neutrophil extracellular trap-related markers for endometriosis) using Venn analysis [5].

- Multi-Algorithm Modeling: Apply 13 machine learning algorithms including Lasso, Stepglm, SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Naive Bayes to construct 107 distinct models [5].

- Model Selection and Validation: Select optimal model based on AUC evaluation with rigorous 10-fold cross-validation. Assess robustness through calibration plots and decision curve analysis [5].

Key Implementation Details:

- The optimal diagnostic model for endometriosis integrated Stepglm [backward] and Random Forest algorithms [5].

- Final biomarkers (CEACAM1, FOS, PLA2G2A, THBS1) were identified through ensemble feature importance across models [5].

- Immune infiltration analysis connected identified biomarkers to potential biological mechanisms [5].

Machine Learning Ensemble Workflow

Causal Inference Framework with Network Analysis

Protocol Overview: This approach combines weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) with bidirectional mediation to identify genes causally linked to disease phenotypes [6].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Network Construction: Generate gene co-expression networks from transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-seq from 103 IPF patients and 103 controls) using WGCNA algorithm [6].

- Module Identification: Identify significantly correlated modules (e.g., 7 out of 16 modules significantly correlated with IPF in original study) [6].

- Confounder Adjustment: Test for confounding effects of clinical variables (age, gender, smoking status) using type-III ANOVA models, adjusting mediation analyses for significant confounders [6].

- Bidirectional Mediation: Apply bidirectional mediation models for each candidate module to identify significant mediator genes acting as potential disease drivers [6].

- Validation: Validate candidate causal genes against independent datasets and known disease associations (e.g., Open Targets Platform) [6].

Key Implementation Details:

- In idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, this approach identified 145 unique mediator genes from seven significantly correlated modules [6].

- 35 of 145 identified genes (24%) were part of the druggable genome collection, indicating therapeutic potential [6].

- Method successfully identified known IPF-associated genes (37/145) while also discovering novel candidates [6].

Causal Inference Analysis Workflow

3D Multi-omics for Linking Non-coding Variants to Causal Genes

Protocol Overview: This methodology maps the three-dimensional folding of the genome to connect non-coding GWAS variants with their target genes through physical interactions [7].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Reference Atlas Construction: Systematically generate multi-omic profiles (3D genomics, chromatin accessibility, gene expression) across relevant healthy cell types to establish baseline regulatory networks [7].

- Disease Variant Mapping: Overlay disease-associated GWAS variants onto the 3D genome structure to identify disrupted regulatory relationships [7].

- Interaction Mapping: Profile genome folding using specialized assays (e.g., Enhanced Genomics' platform) that capture long-range physical interactions genome-wide [7].

- Target Prioritization: Integrate folding data with functional genomics to pinpoint causal genes, considering safety, feasibility, and intellectual property for final selection [7].

Key Implementation Details:

- Traditional nearest-gene approaches are incorrect approximately 50% of the time, highlighting the need for 3D contextual information [7].

- The approach has been particularly valuable for immune-mediated diseases like inflammatory bowel disease with strong genetic components in non-coding regions [7].

- Provides built-in genetic validation by physically connecting associations to target genes [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementation of causal gene validation requires specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table details essential solutions for establishing a functional causality research pipeline.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Causal Gene Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Specific Applications | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors | In vivo gene manipulation for functional validation [1] | Gain/loss-of-function studies in disease models [1] | Adenovirus, lentivirus, RCAS systems [1] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Precise genome editing for causal validation [1] | Direct functional testing of candidate genes [1] | Various delivery formats (viral, nanoparticle) [1] |

| snRNA-seq Platforms | Single-nucleus transcriptomic profiling of tissues [8] | Cell-type specific expression analysis in complex tissues [8] | 10X Genomics, Parse Biosciences [8] |

| Genetic Data Lakes | Scalable storage and analysis of GWAS/mQTL data [9] | Large-scale genetic association analysis [9] | Custom implementations integrating public/private data [9] |

| 3D Genome Mapping Assays | Profiling genome folding and regulatory interactions [7] | Linking non-coding variants to target genes [7] | Enhanced Genomics platform, Hi-C, ChIA-PET [7] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Multi-algorithm ensemble modeling for biomarker discovery [5] | Diagnostic model development, feature selection [5] | Stepglm, Random Forest, XGBoost, SVM [5] |

| Mediation Analysis Frameworks | Statistical causal inference in network analysis [6] | Identifying driver genes in complex diseases [6] | CWGCNA (causal WGCNA) implementation [6] |

The evolving landscape of causal gene identification demonstrates that no single methodology provides a perfect solution. Instead, integrated workflows that combine computational prioritization with experimental validation deliver the most robust results. Machine learning ensembles offer high predictive accuracy for diagnostic applications [5], while causal inference frameworks using network analysis and mediation models effectively distinguish driver genes from passive correlates in complex diseases [6]. For interpreting the non-coding genome that constitutes most GWAS discoveries, 3D multi-omics approaches provide essential physical evidence of gene-regulatory relationships [7].

The most successful pipelines will leverage genetic data lakes for scalable analysis [9], implement multi-algorithm prioritization, and employ direct functional validation using CRISPR/Cas9 and viral vector systems [1]. This integrated approach, moving beyond correlation to definitive causal understanding, promises to accelerate the identification of genetically validated therapeutic targets and ultimately improve success rates in drug development.

The Critical Role of Knockout Validation in Functional Genomics and Drug Development

In the post-genome era, the biopharmaceutical industry has modernized its drug discovery methodology, moving from correlative data to causal evidence. Gene knockout technologies have emerged as a standard currency of mammalian functional genomics research, widely recognized as critical, if not obligatory, in the discovery of new targets for therapeutic intervention [10]. The fundamental premise is straightforward: understanding a gene's function by observing what happens when it is missing provides powerful insights into its role in health and disease [11]. However, as these technologies have advanced, so too has the recognition that proper validation is not merely a supplementary step but the cornerstone of reliable functional genomics and successful drug development.

The validation process ensures that observed phenotypic changes are genuinely attributable to the intended genetic modification rather than technical artifacts or confounding factors. This article examines the critical importance of knockout validation across multiple methodologies, provides detailed experimental protocols, and explores the implications for target identification in pharmaceutical development.

Comparative Analysis of Knockout Technologies and Their Validation Challenges

Technology Landscape and Characteristic Limitations

Different gene perturbation methods present distinct validation challenges and are susceptible to specific artifacts that can compromise experimental interpretation if not properly addressed.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Gene Knockout Technologies and Validation Requirements

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Primary Validation Challenges | Common Validation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 KO | CRISPR-Cas9 induces double-strand breaks repaired by error-prone NHEJ, introducing frameshift mutations [11] | High efficiency; applicable to many genes; enables complete gene disruption | Off-target effects; incomplete editing; potential for exon skipping and chromosomal rearrangements [12] [13] | TIDE analysis; NGS; Western blot; functional assays [14] [15] |

| CRISPRi | dCas9-KRAB fusion protein silences gene expression without DNA cleavage [13] | Reduced off-target effects; reversible; targets non-coding regions | Incomplete knockdown; potential for residual protein function | RNA-seq; qPCR; Western blot; phenotypic confirmation |

| RNAi | Double-stranded siRNA mediates sequence-specific degradation of target mRNA [16] | Well-established; transient effect | Off-target transcription effects; incomplete knockdown; transient nature [16] | qPCR; Western blot; rescue experiments |

| Antibody-mediated LOF | Intracellular antibodies bind and inhibit protein function without altering expression [16] | Rapid onset; targets specific protein domains; no genetic alteration | Delivery efficiency; specificity confirmation; transient effect | Phenotypic assays; control antibodies; expression analysis [16] |

| Traditional KO Mice | Homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells creates heritable null alleles [17] | Whole-organism context; stable genetic modification; developmental studies | Flanking gene effects; genetic background complications; compensatory mechanisms [17] | Backcrossing; phenotypic characterization; complementation tests |

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Methods

Recent comparative studies provide quantitative insights into the performance characteristics of different knockout approaches, particularly regarding their transcriptional impact and reliability.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Gene Knockout and Knockdown Methods

| Method | Target Reduction Efficiency | Time to Phenotypic Onset | Off-Target Transcriptional Changes | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 KO | 82-93% INDEL efficiency in optimized systems [15] | Delayed (requires protein turnover) | Moderate (30% of deregulated mRNAs shared with negative controls) [16] | Functional genomics; disease modeling; target identification |

| RNAi | Variable mRNA reduction (technology-dependent) | Intermediate (hours to days) | High (only 10% of deregulated mRNAs shared with negative controls) [16] | Rapid screening; transient studies; therapeutic development |

| Antibody-mediated LOF | No reduction in target expression [16] | Rapid (direct protein inhibition) | Low (70% of deregulated mRNAs shared with negative controls) [16] | Acute inhibition studies; protein function dissection; target validation |

| CRISPRi | Variable transcriptional repression | Intermediate (transcriptional silencing) | Lower than RNAi (more specific) [13] | Essential gene studies; non-coding RNA investigation; functional genomics |

Critical Methodologies for Knockout Validation

DNA-Level Validation Techniques

Validation begins at the DNA level to confirm intended genetic modifications have occurred. Several established methods provide varying levels of resolution and throughput.

TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition) Analysis

- Protocol: Amplify target region by PCR (ensuring ~200 bp flanking sequence on each side), perform Sanger sequencing of both unedited and edited populations, upload trace files to TIDE online tool with sgRNA sequence [14]

- Applications: Rapid assessment of editing efficiency in bulk populations; quantification of insertion and deletion frequencies; estimating minimum number of clones to screen [14]

- Limitations: Does not detect large structural variations; less sensitive for complex editing patterns

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Approaches

- Protocol: Design PCR amplicons covering target sites and potential off-target regions; sequence using Illumina, Nanopore, or similar platforms; compare to unedited control population using tools like CRISPResso [12] [14]

- Applications: Comprehensive identification of on-target editing efficiency; detection of off-target effects; discovery of complex structural variants (inter-chromosomal fusions, exon skipping, chromosomal truncation) [12]

- Advantages: Unbiased detection of unexpected editing outcomes; quantitative assessment of editing efficiency

Restriction Enzyme Screening

- Protocol: Design knock-in to introduce or disrupt restriction enzyme site; amplify target region by PCR; digest with appropriate restriction enzyme; analyze fragment patterns by gel electrophoresis [14]

- Applications: Rapid screening for specific edits; validation of homozygous knock-in clones; intermediate throughput screening

- Pro Tip: Introduce silent "passenger" mutations creating novel restriction sites when natural sites are unavailable [14]

RNA- and Protein-Level Validation

DNA confirmation alone is insufficient, as transcriptional and translational adaptations can bypass intended knockout effects.

RNA-Sequencing for Transcriptional Validation

- Background: RNA-seq data from CRISPR knockout experiments reveals many unanticipated changes not detectable by DNA amplification alone, including fusion events, exon skipping, and unintended transcriptional modifications of neighboring genes [12]

- Protocol: Extract RNA from knockout and control cells; prepare sequencing libraries; perform RNA-seq; analyze for complete loss of target transcript and unexpected transcriptional changes

- Critical Finding: In one study, 30% of deregulated mRNAs in antibody-transfected cells and 70% in sgRNA-treated cells were shared with their negative controls, compared to only 10% in RNAi experiments, highlighting method-specific confounders [16]

Western Blotting for Protein-Level Confirmation

- Protocol: Separate protein lysates by SDS-PAGE; transfer to membrane; probe with target-specific antibodies; detect with appropriate secondary reagents

- Critical Importance: Some sgRNAs generate high INDEL frequencies (e.g., 80%) but fail to eliminate protein expression, creating potentially misleading results without protein-level validation [15]

- Case Example: An ineffective sgRNA targeting exon 2 of ACE2 showed 80% INDELs but retained full ACE2 protein expression, underscoring the necessity of Western validation [15]

Functional Validation in Biological Context

Genetic and molecular validation must be complemented with functional assays confirming the phenotypic consequences of gene knockout.

Cell-Based Functional Assays

- Adhesion Assays: As employed in comparative studies of Talin1 and Kindlin-2 knockouts, revealing distinct temporal onset dynamics for different knockout methods [16]

- Viability/Proliferation Assays: Essential for confirming essential gene functions

- Pathway-Specific Reporters: Validation of expected pathway disruption

In Vivo Phenotypic Screening

- Comprehensive Phenotyping Protocols: Modeled on human clinical exams, including metabolic profiling, cardiovascular function, neurological and behavioral assessment, hematological analysis, and histological examination [10]

- Applications: Identification of both therapeutic potential and potential side effects; understanding systemic consequences of target ablation

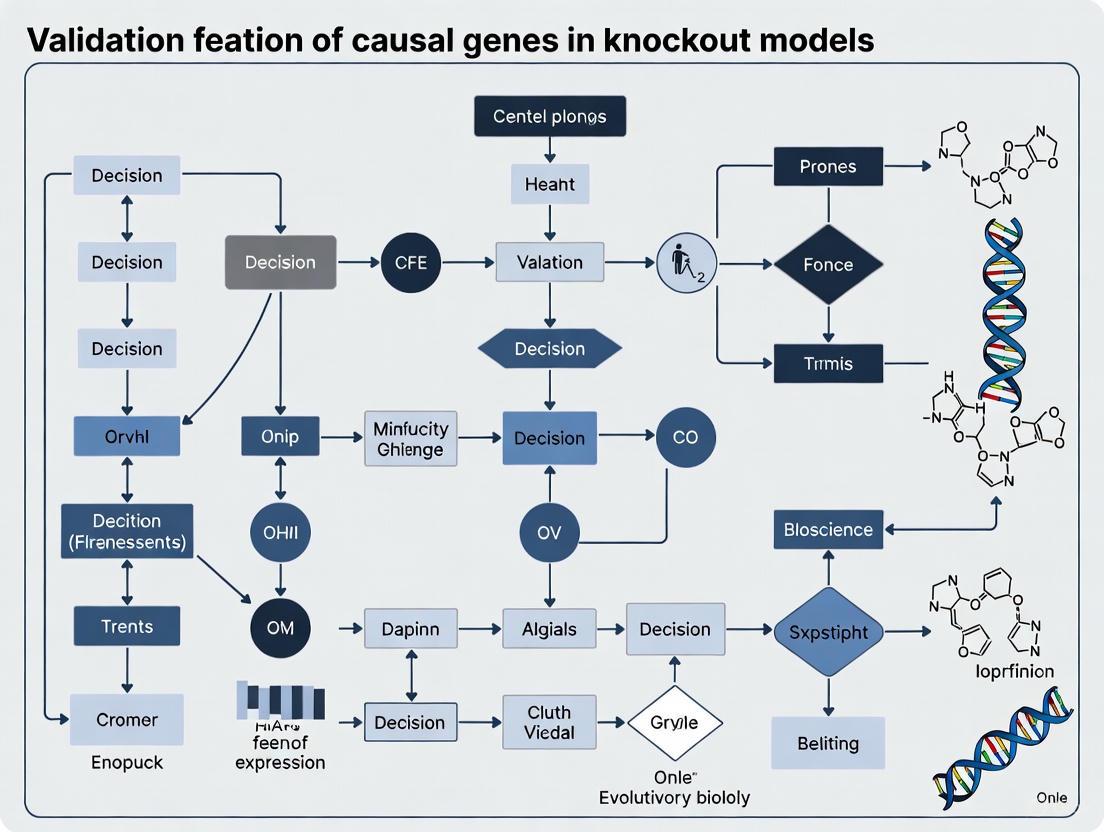

The Knockout Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive validation workflow essential for confirming successful gene knockout and establishing confidence in subsequent phenotypic observations:

Advanced Considerations in Knockout Validation

Addressing Method-Specific Artifacts

Genetic Background Effects in Mouse Models

- Problem: Traditional knockout mice generated using 129-derived embryonic stem cells implanted into C57BL/6 blastocysts retain regions of 129-derived genetic material despite extensive backcrossing [17]

- Impact: These "passenger genes" can produce observable phenotypes misinterpreted as resulting from the targeted knockout [17]

- Solution: Conduct appropriate control experiments including:

- Comparison with coisogenic controls (same 129 substrain with intact target gene)

- Backcrossing to multiple genetic backgrounds

- Complementation tests with different mutant alleles

CRISPR-Specific Artifacts

- Problem: DNA-level validation approaches miss unexpected transcriptional changes including inter-chromosomal fusions, exon skipping, and unintentional amplification of neighboring genes [12]

- Impact: Observed phenotypes may result from these unexpected changes rather than intended knockout

- Solution: Implement RNA-seq as a standard validation step to identify transcriptional changes beyond the target locus [12]

Temporal Dynamics of Phenotype Appearance

Different knockout methods exhibit distinct temporal patterns in phenotypic onset, which must be considered in experimental design and interpretation:

- Antibody-mediated LOF: Rapid phenotypic onset (direct protein inhibition) [16]

- RNAi: Intermediate onset (hours to days, requires mRNA turnover) [16]

- CRISPR-Cas9 KO: Delayed onset (requires protein turnover; dependent on cell division for complete disruption) [16] [11]

- Traditional KO Mice: Developmental onset (potential for compensation throughout development) [17]

Knockout Validation in Drug Target Discovery and Development

The Target Validation Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates how knockout validation integrates into the comprehensive drug target discovery and validation pipeline:

Successful Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

Properly validated knockout models have contributed significantly to target identification and validation across therapeutic areas:

Metabolic Disease Targets

- Melanocortin-4 Receptor (MC-4R): Knockout validation revealed profound obesity phenotype, establishing this target for obesity therapeutics [10]

- Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase 2 (ACC2): Knockout mice showed reduced malonyl-CoA levels and increased fatty acid oxidation without toxic lipid accumulation, supporting its potential for metabolic disorder treatment [10]

Bone Disease Targets

- Cathepsin K: Knockout validation demonstrated osteopetrosis due to impaired bone matrix resorption, identifying this protease as a target for osteoporosis treatment [10]

Neuropsychiatric and Addiction Disorders

- High-Throughput Behavioral Screening: Knockout validation of 33 candidate genes revealed 22 causal drivers of substance intake, providing novel targets for addiction treatment [18]

Safety Assessment and Side Effect Profiling

Knockout validation provides crucial safety information during target assessment:

- Mechanism-Based Toxicity Identification: Phenotypic analysis of knockouts reveals potential mechanism-based side effects before drug development investment [10]

- Target-Specific Effect Anticipation: Knockout phenotypes provide insight into potential side effects of pharmacological inhibition of the same target [10]

- Comprehensive Phenotypic Screening: Standardized phenotyping protocols (e.g., metabolic profiling, cardiovascular function, neurological assessment) identify potential safety concerns [10]

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Knockout Validation

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation Algorithms | TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition) [14] | Quantifies editing efficiency from Sanger sequencing traces | Rapid screening; requires ~200bp flanking sequence in PCR amplicons |

| ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) [15] | Analysis of Sanger sequencing data for INDEL quantification | Compared favorably with TIDE and T7EI assays in accuracy validation [15] | |

| CRISPResso [14] | NGS data analysis for CRISPR editing quantification | Enables simultaneous on-target and off-target assessment | |

| sgRNA Design Tools | Benchling [15] | sgRNA design and efficiency prediction | Most accurate predictions in experimental validation [15] |

| CRISPOR [14] | sgRNA design with off-target prediction | Integrates multiple scoring algorithms | |

| Specialized Reagents | Chemically Modified sgRNA [15] | Enhanced stability with 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications | Improves editing efficiency through increased nuclease resistance |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants (SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) [14] | Reduced off-target editing | Crucial for genes where off-target effects are a concern | |

| Cell Culture Systems | Inducible Cas9 Systems (iCas9) [15] | Doxycycline-controlled Cas9 expression | Achieves 82-93% INDEL efficiency in optimized systems [15] |

Knockout validation represents the critical bridge between genetic manipulation and meaningful biological insight. As functional genomics increasingly drives drug discovery, the implementation of comprehensive, multi-level validation protocols becomes essential for distinguishing true phenotypic effects from methodological artifacts. The integration of DNA-, RNA-, protein-, and functional-level assessments provides a robust framework for establishing confidence in knockout models and the targets they validate. Through rigorous validation approaches, researchers can maximize the translational potential of functional genomics, accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic targets while minimizing costly misinterpretations in the drug development pipeline.

In the landscape of genomic medicine, Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) represent a critical interpretive challenge that stands between genetic data and clinical actionability. A VUS is a genetic alteration identified through testing whose association with disease risk is currently unclear—it is neither classified as pathogenic (disease-causing) nor benign (harmless) [19]. The central dilemma of VUS interpretation lies in navigating the uncertainty that complicates clinical decision-making, exposes patients to potential adverse outcomes, and places significant demands on healthcare resources [19]. As genomic testing expands, VUS substantially outnumber pathogenic findings; for instance, a meta-analysis of breast cancer predisposition testing revealed a VUS to pathogenic variant ratio of 2.5:1, while a 80-gene panel study of unselected cancer patients found 47.4% carried a VUS compared to only 13.3% with pathogenic/likely pathogenic findings [19]. This article examines the current methodologies for VUS resolution, comparing their effectiveness and providing experimental frameworks for researchers engaged in causal gene validation.

Methodologies for VUS Interpretation: A Comparative Analysis

Clinical and Family Studies Approach

The clinical and family studies approach leverages inheritance patterns and segregation data to assess variant pathogenicity, relying on the co-occurrence of genetic variants and clinical phenotypes within families [19].

Table 1: Evidence Types for Variant Classification

| Evidence Category | Key Principles | Strength for Pathogenicity Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Segregation Data | Analyzes variant co-occurrence with disease across family members | Provides evidence that increases with number of families studied [19] |

| De Novo Data | Identifies variants absent in parents but present in affected offspring | Strong evidence when maternity/paternity confirmed [19] |

| Population Data | Compares variant prevalence against disease prevalence in populations | Higher variant prevalence than disease prevalence supports benign classification [19] |

| Clinical Correlation | Matches patient's clinical features with known gene-disease associations | Supports pathogenicity when phenotype matches known condition [19] |

Experimental Protocol for Family Studies:

- Pedigree Construction: Document comprehensive family history across multiple generations, noting disease status and age of onset.

- Sample Collection: Obtain DNA samples from affected and unaffected family members, prioritizing those with definitive phenotype data.

- Genetic Analysis: Perform targeted sequencing for the VUS across family members to establish segregation pattern.

- Lod Score Calculation: Statistically assess the likelihood of linkage between the variant and disease phenotype versus chance.

- Integration: Combine segregation evidence with other data types for comprehensive variant assessment.

Computational and In Silico Prediction Methods

Computational methods leverage bioinformatics algorithms and population genomics data to predict variant effects, serving as a first-line approach for VUS prioritization [19] [20].

Table 2: Computational Platforms for Variant Interpretation

| Tool/Platform | Methodology | Application in VUS Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| VarSome | Integrates ACMG guidelines with multiple prediction algorithms | Provides pathogenicity classification aligned with professional standards [20] |

| CADD | Combines multiple genomic annotations into a quantitative score | Prioritizes variants likely to have deleterious effects [20] |

| SIFT | Predicts whether amino acid substitution affects protein function | Assesses functional impact of missense variants [20] |

| geneBurdenRD | Open-source R framework for gene burden testing | Identifies disease-associated genes through case-control analyses [21] |

| DRAGEN-Hail Pipeline | Trio-based whole genome sequence analysis | Identifies de novo, compound heterozygous, and homozygous variants [20] |

Experimental Protocol for Computational Analysis:

- Variant Annotation: Process VUS through multiple prediction algorithms (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD) to assess functional impact.

- Population Frequency Filtering: Compare against population databases (gnomAD) to exclude common polymorphisms.

- Conservation Analysis: Assess evolutionary conservation of affected amino acid or nucleotide across species.

- Structural Modeling: Predict effects on protein structure, stability, and functional domains.

- Meta-Prediction: Integrate scores from multiple algorithms for consensus classification.

Functional Validation in Model Organisms

Functional studies in model organisms provide direct experimental evidence of variant impact by assessing phenotypic consequences in living systems, offering a powerful approach for VUS resolution [22].

Table 3: Model Organisms for Functional Validation

| Model System | Key Strengths | Limitations | Representative Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. elegans | Simple, cost-effective; high genetic homology; rapid generation time | Limited organ complexity; differences in physiology | Coq-2 missense variants recapitulated CoQ10 deficiency phenotypes, rescue possible with CoQ10 supplementation [22] |

| Zebrafish | Vertebrate development; organ system complexity; transparent embryos | Specialized facilities required; higher maintenance costs | Six candidate genes (RYR3, NRXN1, FREM2, CSMD1, RARS1, NOTCH1) showed phenotypes aligning with patient presentations [20] |

| Mouse Models | Mammalian physiology; sophisticated genetic manipulation | Expensive; time-intensive; ethical considerations | Not explicitly covered in search results but widely used in field |

Experimental Protocol for C. elegans Functional Validation:

- Ortholog Identification: Identify C. elegans orthologs of human genes containing VUS through sequence alignment and functional conservation analysis.

- Strain Generation: Use CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to introduce human-equivalent missense variants into the C. elegans genome.

- Phenotypic Characterization: Assess mutant worms for relevant pathological phenotypes (e.g., movement defects, metabolic abnormalities, morphological changes).

- Rescue Experiments: Test whether human wild-type gene expression or therapeutic interventions (e.g., CoQ10 supplementation) can ameliorate observed phenotypes.

- Multiplexing: Assess multiple variants in parallel to establish spectrum of severity across different mutations.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for VUS interpretation, combining clinical, computational, and functional approaches:

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for VUS Investigation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in VUS Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Precise genome editing to introduce specific variants | Generating humanized missense variants in model organisms [22] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Comprehensive variant detection across entire genome | Identifying structural variants, non-coding variants missed by targeted approaches [20] |

| VarSome Platform | Automated variant interpretation and classification | Implementing ACMG guidelines consistently across variants [20] |

| Phenotypic Screening Assays | Quantitative assessment of pathological features | Measuring movement, metabolic, or developmental phenotypes in model organisms [22] |

| Population Databases (gnomAD) | Determining variant frequency across populations | Filtering out common polymorphisms unlikely to cause rare diseases [20] |

Discussion: Integration and Clinical Translation

The reclassification of VUS requires integrating multiple evidence types to reach a definitive conclusion. Current data indicate that approximately 10-15% of reclassified VUS are upgraded to likely pathogenic/pathogenic, while the remainder are downgraded to likely benign/benign [19]. However, resolution occurs slowly—one study found only 7.7% of unique VUS were resolved over a 10-year period in a major laboratory [19]. This timeline creates challenges for clinical utility, as patients and clinicians may struggle with the uncertainty of unresolved results.

The psychological impact of VUS results is significant; patients with VUS report higher genetic test-specific concerns than those with negative results, though lower than those with positive results [23]. This underscores the importance of clear communication and appropriate counseling when delivering VUS results. While patients with VUS and those with negative results are similarly likely to have changes in clinical management, both are substantially less likely to have management changes compared to patients with pathogenic variants [23].

The following diagram illustrates the evidence integration process for VUS reclassification:

The future of VUS interpretation lies in collaborative data sharing, standardized classification frameworks, and technological advances in functional genomics. Large-scale initiatives like the 100,000 Genomes Project demonstrate the power of statistical approaches for novel gene-disease association discovery [21]. Meanwhile, model organism screening provides a scalable platform for experimental validation of missense variants [22]. As these methodologies mature, they will gradually transform the VUS landscape from one of uncertainty to actionable insight, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine for patients with genetic disorders.

For researchers, the path forward involves systematic application of the integrated framework presented here—combining computational predictions with experimental validation in appropriate model systems, all contextualized within clinical and family data. This multidisciplinary approach will accelerate VUS resolution and enhance our fundamental understanding of gene function in human health and disease.

Leveraging Large-Scale Genomic Data for Cross-Species Gene Discovery

The explosion of large-scale genomic data presents an unprecedented opportunity to accelerate the discovery of functionally important genes. Traditional methods for gene identification, such as mutant screening and genome-wide association studies (GWAS), are often limited to single-species analyses, requiring substantial time, resources, and facing challenges in handling lethal mutations or achieving comprehensive gene coverage [24]. Cross-species computational approaches are overcoming these limitations by leveraging conserved functional elements across organisms to identify candidate genes associated with complex traits. This guide compares emerging methodologies that integrate machine learning with multi-species genomic data, evaluates their performance against traditional techniques, and details experimental protocols for validating computational predictions through causal gene knockout models.

Comparative Analysis of Cross-Species Gene Discovery Methods

The table below summarizes the core methodologies, strengths, and validation evidence for several key approaches in cross-species gene discovery.

Table 1: Comparison of Cross-Species Gene Discovery Platforms and Methods

| Method Name | Core Methodology | Data Inputs | Key Advantages | Experimental Validation Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPGI [24] | Random Forest ML on protein domain profiles | Proteomes, phenotypic data (e.g., shape) | Rapid identification of multiple key genes; interpretable feature importance | CRISPR/Cpf1 knockout in E. coli confirmed role of pal and mreB in rod-shape |

| LPM [25] | Deep learning with disentangled (P,R,C) dimensions | Heterogeneous perturbation data (CRISPR, chemical) | Integrates diverse data types; identifies shared perturbation mechanisms | Predicted drug-target interactions and mechanisms consistent with clinical observations |

| Cross-Species CNN [26] | Multi-task deep convolutional neural networks | DNA sequence, multi-species functional genomics profiles (e.g., ENCODE, FANTOM) | Improved prediction accuracy; enables analysis of human variants with mouse models | Predictions for human variants showed significant correspondence with eQTL statistics |

| Multi-Species Microarray [27] | Cross-hybridization on multi-species cDNA microarrays | cDNA from oocytes of different species | Discovery of evolutionarily conserved genes without prior genome annotation | RT-PCR and gene-specific microarrays confirmed conserved oocyte transcripts |

Detailed Methodologies and Workflows

Genomic and Phenotype-Based Machine Learning (GPGI)

The GPGI framework uses a supervised machine learning approach to predict phenotypes from genomic data and identify influential genes [24].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Curation: Compile a dataset of bacterial genomes with associated phenotypic information (e.g., shape). The cited study used 3,750 bacterial proteomes with shape classifications (cocci, rods, spirilla) [24].

- Feature Matrix Construction: Identify protein structural domains in each proteome using tools like

pfam_scanagainst the Pfam database. Construct a frequency matrix where rows represent bacteria and columns represent unique protein domains. - Model Training and Optimization: Train a machine learning model, such as Random Forest, to predict the phenotype from the domain frequency matrix. The model is trained with parameters like

ntree=1000and feature importance evaluation enabled. - Candidate Gene Selection: Extract the importance ranking of all protein domains from the model. Select the top-ranked domains as key influencers of the phenotype and identify their corresponding genes in a target organism (e.g., E. coli) for experimental validation.

- Validation via Gene Knockout: Use a CRISPR/Cpf1 dual-plasmid system to knock out candidate genes. crRNA sequences targeting the genes are cloned into a plasmid vector, which is then used to transform the host strain. The resulting mutant strains are phenotyped to confirm the predicted trait change [24].

The workflow for this process, from data collection to experimental validation, is illustrated below.

Large Perturbation Models (LPM) for Biological Discovery

LPMs represent a foundational model approach designed to integrate heterogeneous perturbation data. The model architecture disentangles the core components of any perturbation experiment: the Perturbation (P, e.g., a specific CRISPR guide RNA or drug), the Readout (R, e.g., transcriptome or cell viability), and the biological Context (C, e.g., specific cell line or tissue) [25].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Integration: Pool data from diverse perturbation experiments, including genetic (CRISPR) and chemical (drug) perturbations across multiple biological contexts and readout modalities.

- Model Training: Train a decoder-only deep learning model to predict experimental outcomes based on symbolic (P, R, C) tuples. This allows the model to learn perturbation-response rules that are disentangled from the specific context.

- Biological Discovery Tasks:

- Mechanism of Action Analysis: The model generates a joint embedding space for perturbations. Similar embeddings between a compound and a genetic perturbation of a specific gene suggest shared molecular mechanisms [25].

- Therapeutic Discovery: The trained model can be used to simulate the effects of perturbations in silico, identifying potential therapeutics for diseases by linking them to relevant molecular pathways [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Cross-Species Discovery and Validation

| Category | Item | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | Pfam Database | Provides protein domain annotations for functional feature extraction | Used in GPGI to build the feature matrix [24] |

| Basenji Software | Framework for predicting regulatory activity from DNA sequence | Used for cross-species CNN models [26] | |

| Validation Reagents | CRISPR/Cpf1 System | Enables precise gene knockout for functional validation in model organisms | Dual-plasmid system (pEcCpf1/pcrEG) used in E. coli [24] |

| cDNA Microarrays | Platforms for profiling gene expression across multiple species | Custom multi-species arrays identify conserved transcripts [27] | |

| Data Resources | ENCODE/FANTOM | Public compendia of functional genomics profiles (e.g., ChIP-seq, CAGE) | Source of training data for sequence activity models [26] |

| BacDive Database | Provides structured phenotypic and taxonomic data for bacteria | Source of bacterial shape phenotype for GPGI [24] |

Cross-species gene discovery methods are transforming functional genomics by leveraging the power of machine learning on expansive, heterogeneous datasets. Approaches like GPGI, LPM, and cross-species neural networks demonstrate that integrating data across organisms yields more accurate predictions and provides a powerful lens for identifying core functional genes and their mechanisms. The critical step in this pipeline remains the robust experimental validation of computational predictions, typically through targeted genetic perturbations like CRISPR knockout in model organisms, thereby closing the loop between in-silico discovery and confirmed biological function.

A major challenge in modern genetics lies in translating the statistical associations from Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) into a mechanistic understanding of disease. While GWAS successfully identify genomic regions linked to traits, the final step—identifying the specific effector gene and validating its causal role—remains a significant bottleneck [28] [29]. This guide compares the key computational and experimental methods researchers use to bridge this genotype-phenotype gap.

The Core Challenge: From Association to Causation

GWAS identify regions of the genome where genetic variation is associated with a disease or trait. However, most associated variants reside in non-coding regions of the genome, suggesting they influence gene regulation rather than protein structure [30] [31]. Furthermore, linkage disequilibrium (LD) means that the identified variant is often just a marker in tight linkage with the true, causal variant, making pinpointing the exact effector gene difficult [28] [30].

The community has increasingly adopted the term "effector gene" to describe the gene whose product mediates the effect of a genetically associated variant. This term is preferred over "causal gene" as it more accurately describes the predicted role without implying deterministic causality [28]. The process of moving from a GWAS hit to a validated effector gene involves two main steps: gene prioritization (ranking nearby genes by the likelihood of being the effector) and effector-gene prediction (integrating evidence to identify the most likely single gene) [28].

Computational Methods for Gene Prioritization

Computational tools are essential for prioritizing genes at GWAS loci for further experimental validation. The table below compares several state-of-the-art methods and their applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Gene Prioritization and Analysis

| Method Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Reported Performance / Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ODBAE [32] | Identifies complex phenotypes from high-dimensional data (e.g., knockout mouse phenotypes). | Uses a balanced autoencoder to detect outliers based on correlated disruptions across multiple physiological parameters. | Identified Ckb knockout mice with abnormal body mass index despite normal individual body length and weight parameters [32]. |

| Fast3VmrMLM [33] | Genome-wide association study (GWAS) algorithm for polygenic traits. | Integrates genome-wide scanning with machine learning; models additive and dominant effects with polygenic backgrounds. | In simulation studies, showed an average detection power of 92.12% for quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs), outperforming FarmCPU (46.20%) and EMMAX (36.00%) [33]. |

| GGRN/PEREGGRN [34] | Benchmarks tools that forecast gene expression changes from genetic perturbations. | A software framework and benchmarking platform for evaluating expression forecasting methods on diverse perturbation datasets. | Found that it is uncommon for expression forecasting methods to outperform simple baselines when predicting outcomes of entirely unseen genetic perturbations [34]. |

| Ensembl VEP & ANNOVAR [31] | Functional annotation of genetic variants from sequencing data. | Maps variants to genomic features (genes, promoters, regulatory regions) and predicts functional impact. Considered fundamental, primary annotation tools [31]. | Used for the initial annotation step in pipelines to process raw variant call format (VCF) files from WGS or WES studies [31]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Variant to Validated Effector Gene

The following diagram outlines a multi-step workflow for moving from a GWAS association to a functionally validated effector gene, integrating both computational and experimental approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Functional Validation

After computational prioritization, experimental validation is crucial to confirm the effector gene's biological role. The following protocols detail key functional experiments.

Protocol 1: In Vitro Validation of Non-Coding Variants in Transcriptional Regulatory Elements

This protocol is used to test if a non-coding GWAS variant alters the function of a putative enhancer or promoter [30].

- Cloning of Regulatory Element: Amplify the genomic region containing the candidate regulatory element (e.g., enhancer) from both the risk and protective haplotypes using human genomic DNA. Clone each allele into a luciferase reporter plasmid (e.g., pGL4.23).

- Cell Transfection: Transfect the constructed reporter plasmids into a disease-relevant cell line. Include a Renilla luciferase plasmid (e.g., pRL-TK) as a transfection control.

- Dual-Luciferase Assay: After 48 hours, lyse the cells and measure firefly and Renilla luciferase activity using a dual-luciferase assay system. Normalize the firefly luminescence to the Renilla luminescence for each sample.

- Data Analysis: Compare the normalized luciferase activity between the risk and protective haplotype constructs. A statistically significant difference confirms the variant's functional impact on regulatory activity [30].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Validation Using Knockout Mouse Models

Knockout (KO) mouse models are a cornerstone for validating gene function in a whole-organism context [35] [36].

- Model Generation: Generate a gene-specific knockout mouse line using technologies like CRISPR-Cas9. This may be a constitutive or conditional knockout model.

- Phenotypic Screening: Subject the KO mice and wild-type littermate controls to a comprehensive phenotypic screen. This includes:

- Multi-Omics Profiling: Conduct deep phenotyping of tissues (e.g., plasma, heart, kidney) from KO and control mice using techniques like RNA-seq (transcriptomics) and LC-MS/MS (proteomics) to identify dysregulated pathways [36].

- Data Integration: Integrate the phenotypic and omics data to establish a coherent biological narrative. For example, Svep1 deficiency in mice was shown to cause proteomic alterations in pathways related to extracellular matrix organisation and platelet degranulation, providing a mechanistic link to its association with cardiovascular disease [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful functional validation relies on key reagents and resources. The table below lists essential tools for research in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research | Specific Examples / Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Assay Vectors | To test the regulatory activity of non-coding DNA sequences (e.g., enhancers, promoters) in a cellular context. | pGL4-series luciferase vectors; co-transfection with pRL-TK for normalization [30]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | To create targeted gene knockouts in cell lines or animal models for functional studies. | Generation of constitutive or conditional knockout mouse models [35] [36]. |

| Phenotyping Consortia Datasets | Provide large-scale, standardized reference data on the physiological effects of gene knockouts. | Data from the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) for comparing mutant mouse phenotypes [32]. |

| LC-MS/MS Platforms | For deep, quantitative profiling of protein expression changes (proteomics) in tissues or plasma from knockout models. | Used to identify dysregulated pathways in Svep1+/− mice, revealing changes in complement cascade and Rho GTPase pathways [36]. |

| GWAS Catalog & Annotation Tools | Foundational resources for accessing GWAS results and annotating the potential functional impact of genetic variants. | NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog [28]; Ensembl VEP and ANNOVAR for variant annotation [30] [31]. |

Data Integration and Pathway Mapping Workflow

Upon generating data from knockout models, integrating the results is key to understanding the broader biological impact. The following diagram illustrates the process of multi-omics data integration and pathway analysis.

Bridging the genotype-phenotype gap requires a systematic, multi-faceted approach. Researchers must leverage robust computational tools for gene prioritization, followed by rigorous experimental validation in increasingly complex model systems, from cell-based assays to in vivo knockout models. The integration of large-scale phenotypic and multi-omics data from these models is what ultimately transforms a statistical GWAS association into a validated effector gene and a mechanistic understanding of disease.

Principles of Causal Inference in Biological Networks

Establishing causality, rather than merely correlation, is a fundamental challenge in molecular biology and drug discovery. High-throughput technologies generate vast amounts of data on biological entities—genes, proteins, metabolites—and their interactions, but these correlations often provide an illusion of understanding without revealing true causal mechanisms [37]. The core principle of causal inference in biological networks leverages the inherent directionality in biological systems: DNA variations influence changes in transcript abundances and clinical phenotypes, not the reverse [38]. This directionality reduces the number of possible relationship models among correlated traits to three primary types: causal, reactive, and independent [38]. Advanced computational methods now integrate DNA variation, gene transcription, and phenotypic information to distinguish these relationships, enabling high-confidence prediction of causal genes and their roles in disease pathways and networks [38].

The ability to infer true causal relationships has transformative potential for therapeutic development. Traditional drug discovery pipelines risk being clogged by numerous genes of unknown function, with correlative data from genomics, proteomics, and gene arrays often mistaken for causal evidence [10]. Causal inference methodologies address this by identifying "key switches" in mammalian physiology that can be therapeutically targeted, moving beyond associative biomarkers to genuine mechanistic drivers of disease [10]. This review comprehensively compares the leading methodologies for causal inference in biological networks, their experimental validation frameworks, and practical tools for implementation, with a special focus on applications in causal gene validation through knockout models.

Methodological Comparison for Causal Network Inference

Diverse computational methodologies have been developed to reconstruct causal biological networks from observational and experimental data. These approaches differ in their underlying principles, assumptions, and applicability to various biological contexts.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Causal Inference Methods

| Method | Underlying Principle | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRPC | Integrates Principle of Mendelian Randomization (PMR) with PC algorithm [39] | Individual-level genotype & molecular phenotype data (e.g., eQTLs) | Robust to confounding; efficiently distinguishes direct vs. indirect targets of eQTLs [39] | Limited to moderate-dimensional networks |

| LCMS (Likelihood-based Causality Model Selection) | Evaluates causal, reactive, and independent models for traits controlled by DNA loci [38] | DNA variants, transcript levels, clinical phenotypes | Successful prediction of causal genes for abdominal obesity (8/9 genes validated) [38] | Requires well-defined QTLs and trait correlations |

| RACIPE (RAndom CIrcuit PErturbation) | Parameter sampling & ODE simulation for network dynamics [40] | Network topology (without precise parameters) | Describes potential dynamics across broad parameter space; agnostic to precise parameters [40] | Computational intensive for large networks |

| DSGRN (Dynamic Signatures Generated by Regulatory Networks) | Combinatorial analysis of multi-level Boolean models [40] | Network topology only | Rigorous parameter space decomposition; fast computation without ODE simulation [40] | Assumes high Hill coefficients (approximates steep nonlinearities) |

The integration of Mendelian randomization principles with causal graph learning algorithms represents a particularly powerful approach. MRPC incorporates the PMR—which treats genetic variants as naturally randomized perturbations—into the PC algorithm, a classical causal graph learning method [39]. This integration enables robust learning of causal networks where directed edges indicate regulatory directions, overcoming the symmetry of correlation that plagues many association-based methods [39]. The method leverages the fact that alleles of a genetic variant are randomly assigned in populations, analogous to natural perturbation experiments, under three key assumptions: (1) genotypes causally influence phenotypes, (2) genetic variants are not associated with confounding variables, and (3) causal relationships cannot be explained by other variables [39].

Meanwhile, dynamics-based approaches like RACIPE and DSGRN focus on understanding the emergent behaviors of gene regulatory networks across different parameter regimes. Remarkably, despite their different foundations, these methods show strong agreement in predicting network dynamics. Studies comparing them on 2- and 3-node networks found that DSGRN parameter domains effectively predict ODE model dynamics even within biologically reasonable Hill coefficient ranges (1-10), not just in the theoretical limit of very high coefficients [40].

Experimental Validation of Causal Genes

Computational predictions of causal genes require rigorous experimental validation, with mouse knockout models serving as the gold standard for confirming gene function in the context of mammalian physiology.

Validation Workflow and Protocols

The validation pipeline for candidate causal genes involves a systematic multi-stage process:

Candidate Identification: Computational methods (e.g., LCMS, MRPC) analyze genetic mapping data, expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), and phenotypic associations to nominate candidate causal genes [38]. Genes with cis-eQTLs coincident with clinical trait QTLs receive priority, particularly if their expression correlates with disease severity [38].

Animal Model Generation: Knockout (ko) or transgenic (tg) mouse models are constructed for top candidate genes. For comprehensive phenotyping, models are typically generated on standardized genetic backgrounds (e.g., C57BL/6J) with appropriate wild-type littermate controls [38].

Phenotypic Screening: Transgenic and knockout mice undergo comprehensive phenotypic characterization, including:

- Body Composition Analysis: Longitudinal monitoring of fat mass, lean mass, and adiposity using methods like NMR or DEXA [38].

- Metabolic Profiling: Endpoint measurements of plasma lipids (triglycerides, LDL, HDL, total cholesterol), glucose, and free fatty acids [38].

- Tissue-Specific Effects: Detailed dissection and weighing of specific fat pads (gonadal, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, subcutaneous) [38].

- Behavioral and Dietary Responses: Assessment of food intake and response to controlled diets (e.g., high-fat, high-sucrose) when physiologically relevant [38].

Mechanistic Investigation: Gene expression profiling of relevant tissues (e.g., liver) via microarrays or RNA-seq to identify downstream pathways and networks affected by gene perturbation [38].

Network Analysis: Integration of expression signatures with biological pathway databases and protein-protein interaction networks to place validated genes within broader biological contexts [38].

Figure 1: Experimental Validation Workflow for Causal Genes

Case Study: Validation of Obesity Genes

The power of this integrated approach is exemplified by the validation of causal genes for abdominal obesity. Using the LCMS procedure, researchers predicted approximately 100 causal genes from an F2 intercross between C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mouse strains [38]. Nine top candidates were selected for in vivo validation through knockout or transgenic mouse models:

Table 2: Validation Results for Candidate Obesity Genes

| Gene | Model Type | Phenotypic Effects | Additional Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gas7 | Transgenic | Male tg: ↓ fat/lean ratio, ↓ body weight, ↓ fat pad weights; Altered lipid profiles [38] | Novel obesity gene; expressed in multiple tissues; embryonic weights unaffected |

| Me1 | Knockout | ↓ body weight on high-fat diet; Trend toward ↓ fat mass [38] | Novel obesity gene; diet-dependent effects |

| Gpx3 | Transgenic | Male tg: ↓ fat/lean ratio growth; Females: altered cholesterol [38] | Novel obesity gene; sex-specific effects |

| Zfp90 | Transgenic | ↑ fat/lean ratio, ↑ body weight, ↑ fat pad masses [38] | Breeding limitations restricted cohort size |

| C3ar1 | Knockout | Male ko: ↓ fat/lean ratio; Females: opposite trend [38] | Significant sex-by-genotype interaction |

| Tgfbr2 | Heterozygous ko | Male ko: ↓ fat/lean ratio; Females: opposite trend [38] | Homozygous lethal; sex-specific effects |

| Lpl | Heterozygous ko | ↑ adiposity and fat pad weights; Altered lipid profiles [38] | Confirmed previous findings |

| Lactb | Transgenic | Female tg: ↑ adiposity (in additional line) [38] | Sex-specific effects; no lipid changes |

| Gyk | Heterozygous female ko | No significant adiposity changes; Altered metabolites [38] | X-linked; male knockout lethal |

This validation study demonstrated exceptional success, with eight of the nine tested genes significantly influencing obesity-related traits [38]. The high validation rate (89%) underscores the predictive power of sophisticated causal inference methods. Importantly, liver expression signatures revealed that these genes altered common metabolic pathways and networks, suggesting that obesity is driven by a coordinated network rather than single genes in isolation [38].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Implementing causal inference and validation pipelines requires specialized research reagents and computational tools:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Causal Inference

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | MRPC (R package) [39] | Causal network inference integrating PMR with PC algorithm | Distinguishing direct vs. indirect eQTL targets |

| NetConfer [41] | Web application for comparative analysis of multiple networks | Identifying network rewiring across conditions | |

| Cytoscape with plugins [41] | Network visualization and analysis platform | Biological network exploration and comparison | |

| Experimental Models | Knockout mice [38] [10] | In vivo target validation in mammalian physiology | Confirming causal gene functions and side effect profiling |

| Gene trapping ES cells [10] | High-throughput generation of mutant mouse lines | Genome-scale functional genomics screens | |

| Data Resources | eQTL datasets [39] | Genetic variants associated with expression changes | Mendelian randomization-based causal inference |

| Protein-protein interaction networks [42] | Known biochemical interactions among proteins | Constraining causal networks with prior knowledge | |

| Pathway databases [42] | Curated biological pathways | Interpreting validated genes in functional contexts |

Integrated Workflow for Causal Gene Discovery

Combining computational and experimental approaches provides the most robust framework for causal gene discovery. The following workflow integrates multiple methodologies in a coordinated pipeline:

Figure 2: Integrated Causal Gene Discovery Workflow

This integrated approach addresses the fundamental challenge in complex trait genetics: distinguishing causal genes from reactive ones among hundreds of candidates in quantitative trait loci [38]. The workflow leverages the complementary strengths of each methodology—MRPC for robust causal directionality from genetic data, LCMS for evaluating specific causal models, RACIPE/DSGRN for understanding network dynamics, and knockout models for definitive in vivo validation [39] [38] [40].

The value of this comprehensive approach extends beyond basic biological insight to direct therapeutic applications. As demonstrated by the obesity gene validation study, causal inference can identify novel therapeutic targets (e.g., Gas7, Me1, Gpx3) that would likely be missed by conventional association studies [38]. Furthermore, knockout models of potential drug targets provide crucial information about both therapeutic potential and possible side effects by revealing the full phenotypic consequences of target inhibition [10]. This is particularly valuable in drug development, where understanding the complete biological role of a target can de-risk the clinical development process.

Methodological Pipeline: Implementing CRISPR Workflows and Multi-Omics Validation

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering, offering unprecedented precision in gene editing for research and therapeutic development. For researchers focused on validating causal genes through knockout models, two aspects are particularly critical: the design of single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) and the selection of appropriate delivery methods. The efficacy of a CRISPR experiment hinges on sgRNAs that maximize on-target activity while minimizing off-target effects, coupled with delivery vehicles that safely and efficiently transport editing components into target cells. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current sgRNA design tools and delivery methodologies, supported by experimental data and protocols relevant to creating knockout models.

sgRNA Design Fundamentals and Comparison of Design Tools

The single guide RNA (sgRNA) is a synthetic RNA molecule that combines the target-specific crispr RNA (crRNA) with the scaffold trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) into a single sequence [43]. It directs the Cas9 nuclease to a specific genomic locus complementary to its 20-nucleotide targeting region [44]. Proper sgRNA design is paramount for successful gene knockout, influencing both editing efficiency and specificity.

Key Design Parameters for Effective sgRNAs

Several factors significantly impact sgRNA efficiency and must be considered during design [43] [44] [45]:

Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) Requirement: The Cas9 nuclease requires a specific PAM sequence adjacent to the target site. For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' (where "N" is any nucleotide). The target sequence must be located immediately upstream of this PAM, which itself is not part of the sgRNA [43] [45].

GC Content: Optimal sgRNAs typically have GC content between 40-80%, with 40-60% often considered ideal. Both very low and very high GC content can impair efficiency [43] [44].

Sequence Length: For SpCas9, the optimal target sequence length is typically 17-23 nucleotides, with 20 nucleotides being the standard [43] [46].

Position-Specific Nucleotides: Certain nucleotide positions influence efficiency. For instance, a guanine (G) at position 20 (adjacent to the PAM) and an adenine (A) or thymine (T) at position 17 are associated with higher efficiency [45]. Poly-nucleotide repeats (e.g., GGGG) should be avoided [44].

Off-Target Considerations: The sgRNA sequence should be unique within the genome to minimize off-target effects. Mismatches between the sgRNA and DNA target, especially in the "seed region" near the PAM, can lead to unintended cleavage [43] [44].

Comparative Analysis of sgRNA Design Tools

Various computational tools assist researchers in designing optimal sgRNAs by predicting on-target efficiency and potential off-target effects. The table below compares major sgRNA design tools:

Table 1: Comparison of sgRNA Design Tools

| Tool Name | Type/Approach | Key Features | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthego Design Tool [43] | Learning-based | Library of >120,000 genomes; ~97% claimed editing efficiency; Validates externally designed guides. | User-reported: "Extremely fast... reduces significant time in the design process." [43] |

| IDT CRISPR Design Tool [46] | Hybrid (Pre-designed & Custom) | Pre-designed guides for 5 species; Provides on-target & off-target scores. | Recommends testing 3 guides per target to identify the most effective sequence. [46] |

| CHOPCHOP [43] | Varied | Options for alternative Cas nucleases (e.g., Cas12) and their PAM sequences. | Broad nuclease compatibility beyond standard SpCas9. [43] |

| Cas-Offinder [43] | Alignment-based | Specifically developed for detecting potential off-target editing sites. | Focuses on specificity rather than on-target efficiency prediction. [43] |

| Deep Learning Tools [44] | Deep Learning (CNN) | Automated feature extraction from sequence data for activity prediction. | Emerging evidence suggests potential for higher accuracy than earlier machine learning tools. [44] |

Delivery Methods for CRISPR-Cas9

Getting CRISPR components into cells remains a significant challenge. The choice of delivery method impacts editing efficiency, specificity, and applicability for in vivo or ex vivo approaches. CRISPR cargo can be delivered as DNA, mRNA, or, most effectively for knockout studies, as a preassembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex [47].

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Delivery Methods

Delivery vehicles are broadly categorized into viral, non-viral, and physical methods. The table below compares their characteristics, advantages, and limitations:

Table 2: Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Methods

| Delivery Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) [47] | Viral vector infects cells, leading to expression of CRISPR components from delivered DNA. | Mild immune response; Non-integrating (mostly). | Very limited cargo capacity (~4.7 kb); difficult to fit SpCas9 with sgRNAs/donor. [47] |

| Lentivirus (LV) [47] | Viral vector integrates into host genome for stable expression. | Can infect dividing/non-dividing cells; No practical cargo size limit. | Integrates into genome (safety concerns); Prolonged expression increases off-target risk. [47] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [47] [48] | Synthetic lipid vesicles encapsulate and deliver cargo (RNP, mRNA). | Favorable safety profile; Suitable for in vivo use; Enables re-dosing. [48] | Can be trapped in endosomes; Primarily targets liver cells without modification. [47] |

| Electroporation [49] | Physical method using electrical pulses to create pores in cell membranes. | High efficiency for ex vivo editing (e.g., in zygotes, immune cells). | Mostly applicable to ex vivo settings; Can cause significant cell death. [49] |

| LNP-SNAs [50] | LNP core with CRISPR cargo coated with a spherical nucleic acid shell. | 3x higher editing efficiency & cell uptake; Reduced toxicity vs. standard LNPs. [50] | Novel technology (2025), not yet widely adopted; Further in vivo validation ongoing. [50] |

Advanced Delivery Systems: LNP-SNAs

A 2025 study introduced Lipid Nanoparticle Spherical Nucleic Acids (LNP-SNAs) as a superior delivery platform [50]. This architecture involves a standard LNP core packed with CRISPR machinery, coated with a dense shell of DNA strands. This structure promotes enhanced cellular uptake and endosomal escape. In tests across various human and animal cell types, LNP-SNAs demonstrated:

- Threefold increase in cell entry compared to standard LNPs

- Tripled gene-editing efficiency

- Dramatically reduced toxicity

- Over 60% improvement in the success rate of precise homology-directed repair (HDR) [50]

This platform exemplifies the principle that the structure of the delivery vehicle is as crucial as its cargo for unlocking CRISPR's full potential.

Experimental Protocols for Knockout Model Validation

Protocol: RNP Assembly and Zygote Electroporation for Mouse Models

Generating knockout mouse models via zygote electroporation is a highly efficient method. The following protocol is adapted from Winiarczyk et al. (2025) [49]:

- gRNA Preparation: Combine 100 µM crRNA and 100 µM tracrRNA in nuclease-free duplex buffer. Heat the mixture at 95°C for 3 minutes and then allow it to cool slowly to anneal the gRNA [49].

- RNP Complex Formation: Dilute the Cas9 protein (e.g., 61 µM NLS-Cas9) in a transfection medium like Opti-MEM I. Mix the diluted Cas9 with the annealed gRNA and incubate for a few minutes to form the RNP complex [49].

- Zygote Collection & Electroporation: Collect mouse zygotes and wash them thoroughly to remove any residual medium. Line up the zygotes in an electrode gap filled with the RNP complex solution. Perform electroporation (e.g., 30 V, 3 ms ON + 97 ms OFF, 10 pulses) [49].

- Post-Electroporation Culture: Immediately post-electroporation, collect and wash the zygotes. Culture them in KSOM medium at 37°C under 5% CO2 until they reach the blastocyst stage for transfer or analysis [49].

This method's efficiency is demonstrated by studies showing over 90% of newborn mice carrying mutations when targeting single genes and up to 80% with biallelic mutations for two genes [51].

Protocol: Cleavage Assay for Rapid Validation of Editing

The Cleavage Assay (CA) provides a rapid, cost-effective method to validate CRISPR efficacy in edited embryos before proceeding to animal generation [49].

- Principle: The assay leverages the fact that after successful CRISPR-mediated editing, the target locus is altered. When genomic DNA from edited embryos is incubated with a freshly prepared RNP complex targeting the original sequence, the modified DNA will no longer be cleaved efficiently.

- Procedure: Extract genomic DNA from a subset of edited embryos (e.g., at the blastocyst stage). Incubate this DNA with a new batch of RNP complex in vitro. Analyze the DNA by PCR and electrophoresis. A successful edit is indicated by a significant reduction in cleavage compared to a control, as the RNP can no longer recognize and cut the modified target site effectively [49].

- Advantage: This method serves as a predictive screening tool, reducing reliance on extensive and costly Sanger sequencing during initial screening phases [49].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for creating and validating knockout mouse models using CRISPR-Cas9.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions