A Comprehensive Guide to Selecting Variants for Powerful Rare Variant Analysis

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and analyzing rare genetic variants.

A Comprehensive Guide to Selecting Variants for Powerful Rare Variant Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and analyzing rare genetic variants. We cover the foundational principles of rare variants and their role in explaining 'missing heritability' in complex diseases. The guide delves into state-of-the-art methodological approaches, including burden, SKAT, and combined tests, alongside practical software implementation with tools like RVTESTS. It also addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for challenges like population stratification and power limitations. Finally, we explore validation techniques and comparative analyses, highlighting the impact of large biobank studies and emerging AI models that are accelerating rare disease diagnosis and therapeutic development.

Understanding Rare Variants: From Biology to Analysis Rationale

Variant Spectrum: Definitions and Analysis Methods

Quantitative Definitions of Variant Classes

The classification of genetic variants is primarily based on their Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) within a population. The table below summarizes the standard quantitative thresholds for each class.

| Variant Class | Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Rare | < 0.1% (MAF < 0.001) | Often recent in origin, can have large phenotypic effects, may be family-specific or de novo [1] [2]. |

| Rare | 0.1% - 1% (0.001 ≤ MAF < 0.01) | Contributes to severe Mendelian disorders and complex traits; analysis often requires large sample sizes [3] [4]. |

| Low-Frequency | 1% - 5% (0.01 ≤ MAF < 0.05) | Serves as a bridge between rare and common variation; can be identified via genotyping arrays [4] [2]. |

Core Methodologies for Rare Variant Analysis

Choosing the correct statistical approach is crucial for well-powered rare variant association studies. The following table outlines the primary classes of methods used.

| Method Class | Core Principle | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Burden Tests | Collapses multiple variants within a region (e.g., a gene) into a single combined score, assuming all variants influence the trait in the same direction [4] [2]. | Ideal when you have prior evidence that most rare variants in your gene-set are deleterious. |

| Variance Component Tests (e.g., SKAT) | Tests for the cumulative effect of multiple variants but allows for both risk-increasing and protective variants within the same set [4] [2]. | Superior when the genetic region likely contains variants with mixed effects on the trait. |

| Combination Tests (e.g., SKAT-O) | A hybrid approach that blends burden and variance component tests to optimize power across different scenarios [4] [2]. | A robust default choice when the true genetic architecture of the trait is unknown. |

Experimental Protocols for Rare Variant Research

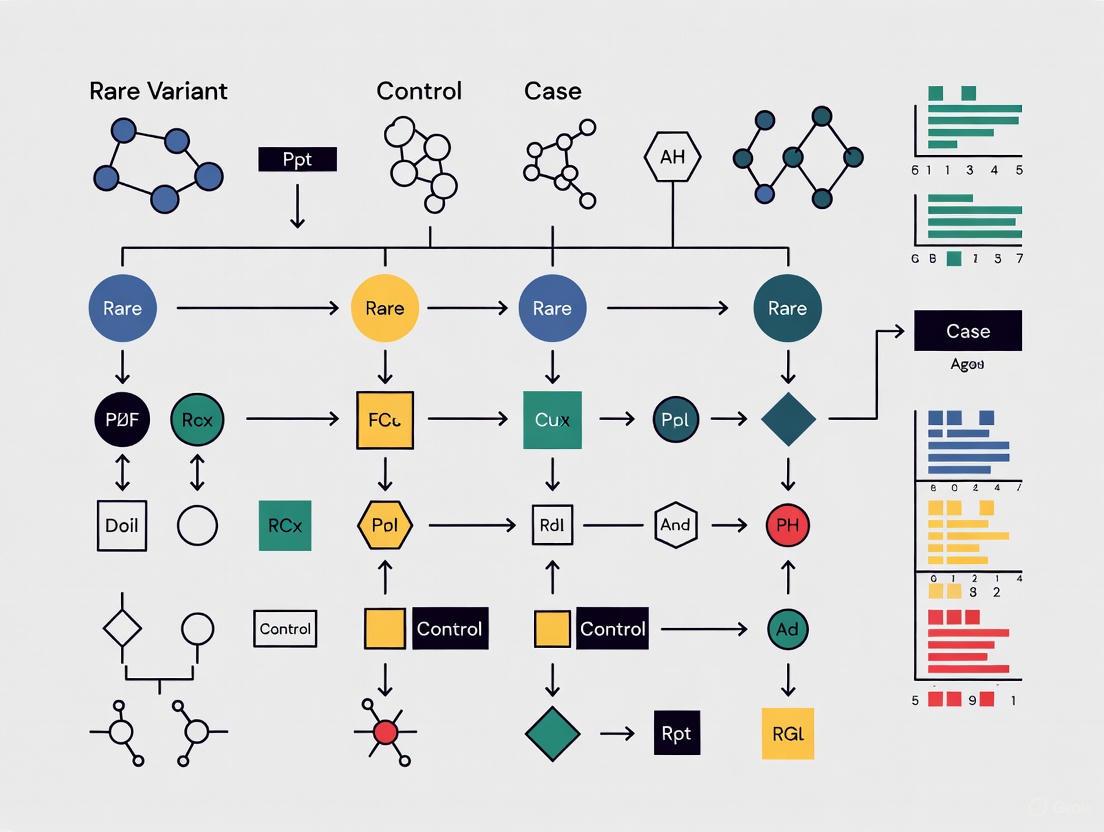

Workflow for an Integrated Rare Variant Association Study

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for a rare variant study, from initial sequencing to functional validation.

Detailed Methodological Steps

Sequencing and Variant Discovery: The process typically begins with whole-exome sequencing (WES) or whole-genome sequencing (WGS). For WES, library preparation uses probes to capture protein-coding regions, which are then sequenced on platforms like the Illumina NovaSeq6000. Subsequent variant calling is performed using established pipelines like the GATK best practices for mapping and annotation [5]. For focused studies, targeted-region sequencing is a cost-effective alternative [4].

Variant Annotation and Filtering: Identified variants are annotated using tools like ANNOVAR or Variant Effect Predictor (VEP). Key filtering steps include:

- Frequency-based filtering: Removing variants that are too common to be likely drivers of a rare disease, using population databases like gnomAD [6] [7].

- Quality and depth filtering: Ensuring high-confidence variant calls.

- Functional impact prediction: Using in silico tools to predict if a variant is disruptive (e.g., protein-truncating variants) [7].

Rare Variant Association Analysis: This involves testing for an excess of rare variants in cases versus controls within pre-defined genomic units, most commonly genes.

- Defining Variant Sets: Variants are grouped by gene or functional unit. For case-control studies, a binary trait (e.g., severe vs. mild COVID-19) is defined [5].

- Choosing a Statistical Test: Apply burden, variance component (like SKAT), or combination tests (like SKAT-O) as described in the methods table above [4] [2].

- Accounting for Covariates: Regression-based models are used to adjust for confounding factors such as age, sex, and genetic ancestry (population structure), which is particularly important for rare variants [5] [2].

Variant Interpretation and Prioritization: Significant variants or genes from the association analysis must be interpreted for potential pathogenicity. This is guided by frameworks like the ACMG-AMP guidelines, which classify variants as Benign, Likely Benign, Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS), Likely Pathogenic, or Pathogenic [6] [7]. This process integrates multiple lines of evidence, including population data, computational predictions, and functional data.

Decision Pathway for Selecting a Rare Variant Test

Selecting the most appropriate statistical test is a critical step. This decision pathway helps guide researchers based on their hypotheses about the genetic architecture of their trait of interest.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQs: Experimental Design and Analysis

Q: What is the most critical factor for a well-powered rare variant study? A: Sample size is paramount. Because individual rare variants are, by definition, found in very few individuals, extremely large cohorts (often tens of thousands of participants) are required to achieve sufficient statistical power to detect associations [2].

Q: How can I control for population stratification in rare variant studies? A: Population structure is a greater confounder for rare variants, which can be recent and population-specific. Standard methods include using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or linear mixed models. However, these may be less effective for ultra-rare variants, and specialized methods that incorporate finer population structure are sometimes needed [4] [2].

Q: What should I do if my rare variant analysis identifies a gene with a significant association, but it contains many variants? A: This is a common challenge. Follow-up prioritization is essential. Focus on variants with the highest predicted functional impact (e.g., protein-truncating variants), those that are ultra-rare, and those located in functional domains critical to the gene. Integration with functional annotations and AI-based pathogenicity prediction models like popEVE can help identify the most likely causal variants [8].

Troubleshooting Common Sequencing Preparation Issues

Library preparation is a frequent source of error in sequencing-based studies. The table below outlines common problems and their solutions.

| Problem | Failure Signals | Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Library Yield | Low concentration; faint/smeared electropherogram peaks [9]. | Degraded DNA/RNA; sample contaminants; inaccurate quantification [9]. | Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) over UV; verify fragmentation parameters [9]. |

| Adapter Dimer Contamination | Sharp peak at ~70-90 bp in Bioanalyzer output [9]. | Excess adapters; inefficient ligation; overly aggressive purification [9]. | Titrate adapter-to-insert ratio; optimize ligation conditions; use bead-based cleanup with correct ratios [9]. |

| Low Library Complexity / High Duplication | High rate of PCR duplicates in sequencing data; overamplification artifacts [9]. | Too few PCR cycles; insufficient input DNA; PCR inhibitors [9]. | Increase input DNA if possible; optimize PCR cycle number; ensure clean sample input without inhibitors [9]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, tools, and databases that are essential for conducting rare variant analysis.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Kits | Prepare genetic material for sequencing on NGS platforms. | Illumina Exome Panel, TruSeq DNA PCR-free kit [5]. |

| Variant Caller | Identify genetic variants from raw sequencing data. | GATK, DRAGEN pipeline [5]. |

| Population Database | Determine variant frequency to filter common polymorphisms. | gnomAD, 1000 Genomes Project [6] [7]. |

| Variant Annotator | Add functional, conservation, and pathogenic information to variants. | ANNOVAR, Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) [5] [6]. |

| Pathogenicity Predictor | Computational prediction of a variant's deleteriousness. | In-silico tools (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen); AI models (e.g., EVE, popEVE) [8] [7]. |

| Clinical Variant Database | Access curated information on variant-disease associations. | ClinVar, ClinVar, CIViC [6]. |

| Rare Variant Analysis Software | Perform burden, SKAT, and other association tests. | R packages (e.g., SKAT, CAST); SAIGE-GENE [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does purifying selection influence the allele frequency of variants in genetic databases? Purifying selection acts against deleterious genetic variants, removing them from the population over time. Consequently, variants with high penetrance and strong detrimental effects are kept at very low frequencies. In large genetic databases like gnomAD, you will observe a strong negative correlation between variant pathogenicity scores (e.g., CADD scores) and their allele frequency. Highly scored (likely deleterious) variants are overwhelmingly rare or even singletons (found in only one individual), whereas neutral variants are common. This principle allows researchers to use allele frequency as a proxy for variant deleteriousness, with rare variants being enriched for functional impact. [10]

Q2: What are the key statistical challenges in rare variant association studies (RVAS) and how can they be addressed? RVAS face distinct challenges compared to common variant studies. The table below summarizes the main issues and common solutions. [2] [4]

Table 1: Key Challenges and Solutions in Rare Variant Analysis

| Challenge | Description | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Statistical Power | Single-variant tests are underpowered due to very low Minor Allele Frequency (MAF). | Use gene-based or region-based aggregative tests (e.g., burden tests, SKAT) that combine multiple variants. [2] |

| Multiple Testing Burden | The number of rare variants is vastly greater than common variants. | Aggregate variants in predefined units (genes, pathways); use sliding-window approaches for non-coding regions. [2] [4] |

| Population Stratification | Rare variants can be recent and reflect fine-scale population structure, causing false positives. | Use methods that account for relatedness (e.g., SAIGE-GENE), include more principal components, or use family-based designs. [2] [4] |

| Allelic Heterogeneity | Causal variants within a gene may have opposing effects (risk vs. protective). | Use variance-component tests like SKAT or combination tests like SKAT-O, which are robust to mixed effect directions. [2] [4] |

Q3: What is the difference between a burden test and a variance-component test for rare variant analysis? These are two primary classes of gene-based aggregative tests, and they make different assumptions about the variants being analyzed: [2] [4]

- Burden Tests: These tests collapse rare variants within a gene into a single "burden score" (e.g., a count of rare alleles per individual). They assume all causal variants in the set influence the trait in the same direction and with similar magnitude. Examples include the Cohort Allelic Sums Test (CAST) and weighted-sum tests. [2]

- Variance-Component Tests (e.g., SKAT): These tests model the effects of individual variants as random effects, allowing for the presence of both risk and protective variants within the same gene set. They do not require assumptions about the direction of effect and are therefore more robust when such heterogeneity exists. [2] [4]

Q4: How can I optimize variant prioritization tools for rare disease research? Tools like Exomiser and Genomiser, which integrate genotypic and phenotypic data, are central to rare disease diagnosis. Performance is highly dependent on parameter optimization. A 2025 study on Undiagnosed Diseases Network data demonstrated that optimizing parameters—such as the choice of variant pathogenicity predictors, frequency filters, and the quality/quantity of Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms—can dramatically improve diagnostic yield. For instance, optimizing Exomiser increased the percentage of coding diagnostic variants ranked in the top 10 from 49.7% to 85.5% for genome sequencing data. Always use comprehensive, high-quality HPO terms for the proband for best results. [11]

Q5: When should I consider the presence of structural variants (SVs) in my analysis? You should suspect SVs, which include deletions, duplications, inversions, and translocations, in cases where a strong clinical suspicion exists but no causative single-nucleotide variant or small indel has been found. While long-read sequencing is the gold standard for SV detection, novel bioinformatics pipelines can now identify complex SVs from standard short-read whole-genome sequencing data. One such study identified diagnostic SVs in 145 children, about half of whom had variants difficult to detect with other genetic tests. If your initial analysis is negative, consider a dedicated SV analysis, as SVs contribute significantly to rare diseases. [12]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inadequate Statistical Power in Rare Variant Association Analysis

Symptoms:

- No variants or genes reach statistical significance despite a strong prior hypothesis.

- Manually inspected variants appear compelling but do not pass stringent significance thresholds.

Investigation and Solutions:

- Verify Study Design and Sampling:

- Action: Consider using an extreme-phenotype sampling strategy, which enriches for rare variants by selecting individuals at the tails of a trait distribution. This can increase power while reducing sequencing costs. [4]

- Action: For family-based studies, ensure you are using statistical methods robust to relatedness, such as the Transmission Disequilibrium Test (TDT) or family-based association tests (FBATs). [4]

- Re-evaluate Your Association Testing Strategy:

- Action: If you suspect all rare variants in your gene of interest are deleterious, switch to a burden test.

- Action: If you suspect a mix of risk and protective variants, or variants with highly variable effect sizes, use a variance-component test like SKAT or a combined test like SKAT-O. [2] [4]

- Action: For very large sample sizes (N > 40,000) with binary traits, use a scalable method like SAIGE-GENE to control type I error rates effectively. [4]

- Incorporate Functional Annotations:

Problem 2: High-Ranking Candidate Variants are False Positives or Not Causative

Symptoms:

- Top variants from prioritization tools are common in the general population or are not de novo in a family trio.

- A candidate variant fails to segregate with the disease in a family.

Investigation and Solutions:

- Scrutinize Population Frequency Filters:

- Validate Segregation and De Novo Status:

- Action: For family studies, always confirm the inheritance pattern. A reported de novo variant should be absent in both biological parents. Use trio sequencing to definitively establish inheritance. [13] [11]

- Action: Check that the variant co-segregates with the disease in larger families, if available. A lack of perfect segregation is a strong indicator against pathogenicity for a highly penetrant variant.

- Check for Population Stratification:

Problem 3: Diagnostic Dead End in a Rare Mendelian Disease Case

Symptoms:

- Comprehensive exome or genome sequencing has been performed.

- All obvious candidate variants (e.g., in known disease genes) have been ruled out.

Investigation and Solutions:

- Reanalyze with Optimized Prioritization Parameters:

- Action: Systematically optimize your variant prioritization tool. As demonstrated in a 2025 study, adjusting parameters in Exomiser/Genomiser for gene-phenotype associations and pathogenicity scores can recover previously missed diagnostic variants, boosting top-10 rankings by over 35%. [11]

- Expand Search to Non-Coding Regions:

- Action: Use tools like Genomiser that are specifically designed to prioritize regulatory variants in non-coding regions. This is crucial when a coding variant is found on only one allele for a recessive disease. [11]

- Initiate a Structural Variant (SV) Analysis:

- Action: Re-analyze your WGS data with a dedicated SV-calling pipeline. As one study showed, ~8% of pathogenic SVs are complex, involving multiple changes that are easily missed by standard variant callers. [12]

- Request Reanalysis of Raw Data:

- Action: Many clinical and research labs offer no-cost reanalysis of existing sequencing data within a certain timeframe (e.g., 3 years). Periodic reanalysis can yield a diagnosis as knowledge bases and methods improve. [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Resources for Rare Variant Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Prioritization Software | Exomiser, Genomiser, AI-MARRVEL [11] | Integrates genotype, phenotype (HPO terms), and inheritance to rank candidate variants. |

| Variant Pathicity Predictors | CADD (Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion), ReMM [10] [11] | Provides a genome-wide score predicting the deleteriousness of a variant. ReMM is specialized for non-coding regulatory variants. |

| Population Frequency Databases | gnomAD, ALFA, TOPMed [10] | Provides allele frequency data across diverse populations to filter out common polymorphisms. |

| Phenotype Ontology | Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) [11] | A standardized vocabulary for clinical features, essential for computational phenotype-driven analysis. |

| Rare Variant Association Tests | SKAT/SKAT-O, Burden Tests, SAIGE-GENE [2] [4] | Statistical packages for performing gene-based or region-based aggregative tests for rare variants. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: A Workflow for Case-Control Rare Variant Association Analysis

This protocol outlines a standard analytical workflow for identifying genes enriched for rare variants in a case-control cohort.

1. Preprocessing and Quality Control (QC)

- Variant Calling: Perform whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing on all cases and controls. Jointly call variants across all samples to ensure consistent genotypes.

- Variant QC: Apply standard filters for call rate, depth, and genotype quality. Remove technical outliers.

- Sample QC: Check for relatedness and genetic sex mismatches. Remove duplicate samples.

2. Variant Filtering and Annotation

- Define "Rare": Set a Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) threshold (e.g., < 0.01 or < 0.001) based on your sample size and study power. [2]

- Annotate Variants: Use a tool like ANNOVAR or VEP to annotate variants with functional consequences (e.g., missense, loss-of-function, splice-site) and population frequencies from databases like gnomAD.

- Select Variant Set: Focus on potentially functional variants, such as loss-of-function (LoF), missense, and splice-site variants. You may choose to include non-coding variants if using WGS data.

3. Gene-Based Association Testing

- Choose a Test:

- Account for Covariates: Include relevant covariates like age, sex, and genetic principal components (PCs) to control for population stratification.

4. Interpretation and Validation

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply a multiple testing correction method (e.g., Bonferroni, FDR) to the gene-based p-values.

- Replication: If possible, attempt to replicate top association signals in an independent cohort.

- Functional Validation: Plan downstream functional experiments (e.g., in vitro assays, animal models) for the most promising candidate genes.

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow for this analysis.

Protocol 2: A Diagnostic Variant Prioritization Workflow for Rare Mendelian Disease

This protocol is designed for diagnosing an individual proband or family using sequencing data.

1. Data Input and Preparation

- Sequencing Data: Obtain a VCF file from the proband's exome or genome sequencing. Trio sequencing (proband + parents) is highly recommended.

- Phenotype Data: Create a comprehensive list of the proband's clinical features using precise Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms. [11]

- Pedigree File: Prepare a PED file specifying the family structure and affected status.

2. Run Variant Prioritization Tool (Exomiser/Genomiser)

- Input Files: Provide the VCF, HPO list, and PED files to Exomiser.

- Parameter Optimization: Based on recent evidence, use optimized parameters for:

- Variant pathogenicity predictors: CADD v1.6/1.7.

- Frequency filters: Use stringent cutoffs (e.g., MAF < 0.001).

- Inheritance modes: Analyze all plausible modes (e.g., autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, de novo). [11]

3. Candidate Evaluation

- Review Top Candidates: Manually inspect the top 10-30 ranked variants/genes from the Exomiser output.

- Check Guidelines: Evaluate candidate variants according to established clinical guidelines (e.g., ACMG-AMP) for pathogenicity.

- Segregation Analysis: Confirm that the variant's inheritance pattern in the family matches the suspected disease model.

4. Complementary and Secondary Analyses

- Run Genomiser: If no causal variant is found, run Genomiser to search for non-coding regulatory variants. [11]

- Structural Variant Analysis: If the above steps are negative, perform a dedicated structural variant analysis on the WGS data. [12]

- Reanalysis: Schedule periodic reanalysis of the raw data, as new disease genes and variant interpretations are continuously discovered. [14]

The diagnostic journey, from initial testing to a potential result, is summarized in the workflow below.

Solving the 'Missing Heritability' Problem in Complex Traits

Key Evidence: The Role of Rare Variants

The following table summarizes the key quantitative evidence from recent large-scale studies on the contribution of rare genetic variants to complex trait heritability.

| Evidence Source | Sample Size & Data | Key Finding on Rare Variants | Proportion of WGS-based Heritability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heritability Mapping Study [15] | 347,630 WGS individuals; 34 phenotypes | On average, rare variants (MAF < 1%) account for 20% of WGS-based heritability. | 20% from rare variants; 68% from common variants |

| Heritability Mapping Study [15] | 347,630 WGS individuals; 34 phenotypes | Of the rare-variant heritability, ~79% is attributed to non-coding variants. | 21% coding, 79% non-coding (of the rare-variant component) |

| Rare Variant Risk Study [16] | 454,712 exomes; 90 phenotypes | Rare, penetrant mutations in GWAS-implicated genes confer ~10-fold larger effects than common variants in the same genes. | N/A (Effect size comparison) |

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Your Rare Variant Analysis

Question: Our rare variant meta-analysis shows inflated type I error rates for low-prevalence binary traits. How can we fix this?

Answer: Type I error inflation is a common challenge in meta-analysis of binary traits with case-control imbalance, such as low-prevalence diseases [17].

- Recommended Solution: Implement the Meta-SAIGE method. It employs a two-level saddlepoint approximation (SPA) to accurately estimate the null distribution [17].

- Level 1: SPA is applied to the score statistics within each individual cohort.

- Level 2: A genotype-count-based SPA is used for the combined score statistics across all cohorts in the meta-analysis [17].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Per-cohort preparation: Use SAIGE to generate per-variant score statistics (S) and their variances for each cohort. Simultaneously, generate a sparse linkage disequilibrium (LD) matrix (Ω) for the regions to be tested [17].

- Summary statistic combination: Combine score statistics from all cohorts. The covariance matrix is calculated as ( \text{Cov}(S) = V^{1/2} \text{Cor}(G) V^{1/2} ), where ( \text{Cor}(G) ) is derived from the LD matrix and ( V ) is the variance from the SPA-adjusted P values [17].

- Gene-based testing: Conduct Burden, SKAT, and SKAT-O tests on the combined summary statistics using the same approach as SAIGE-GENE+ [17].

Answer: Yes, you can leverage methods that reuse computational components across phenotypes.

- Recommended Solution: Adopt the Meta-SAIGE framework, which is designed for computational efficiency in phenome-wide analyses [17].

- Efficiency Protocol:

- Reuse the LD Matrix: Meta-SAIGE uses a sparse LD matrix that is not phenotype-specific. This same LD matrix, once computed for a cohort, can be reused across hundreds or thousands of different phenotypes [17].

- Storage Optimization: For meta-analyzing M variants from K cohorts for P phenotypes, this approach requires (O(MFK + MKP)) storage. In contrast, methods requiring phenotype-specific LD matrices (e.g., MetaSTAAR) need (O(MFKP + MKP)) storage, which is substantially larger [17].

Question: How can we improve the statistical power of our rare variant burden tests?

Answer: Power in burden tests is highly dependent on accurately classifying which rare variants are likely to be functional.

- Recommended Solution: Integrate advanced in-silico pathogenicity predictors into your variant prioritization strategy.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Apply a High-Performance Predictor: Use a tool like PrimateAI-3D, a deep learning-based classifier trained on evolutionary data from primate species. Integrate its scores into your burden testing pipeline [16].

- Benchmark the Improvement: Compare gene discovery rates with and without the predictor. In one study, using PrimateAI-3D improved gene discovery by 73% (1,285 more associations) at the same false discovery rate (FDR) [16].

- Validate Associations: Confirm that the newly discovered gene-phenotype pairs are enriched for genes implicated by GWAS and genes known for related Mendelian diseases, supporting their biological relevance [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions

The table below lists key resources for designing and conducting a robust rare variant analysis study.

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-SAIGE [17] | Software | Rare variant meta-analysis | Scalable meta-analysis that controls type I error for binary traits and boosts efficiency via LD matrix reuse. |

| PrimateAI-3D [16] | Pathicity Predictor | Prioritizes deleterious missense variants | Increases power in burden tests by correctly weighting pathogenic variants; correlates with effect size and age of onset. |

| SAIGE/SAIGE-GENE+ [17] | Software | Rare variant association testing | Provides accurate per-cohort summary statistics and P values, adjusting for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness. |

| Ensembl VEP [18] | Annotation Tool | Predicts functional consequences of variants | Standardized annotation (e.g., stop-gained, splice-site) using Sequence Ontology terms; crucial for variant filtering and grouping. |

| Exome/Genome Array [19] | Genotyping Platform | Interrogates known coding variants | A cost-effective alternative to sequencing for genotyping a pre-defined set of rare exonic variants in very large samples. |

| DRAGEN Secondary Analysis [20] | Bioinformatic Pipeline | Accurate variant calling from NGS data | Provides highly accurate calling of SNVs, indels, and CNVs from whole-genome, whole-exome, or targeted sequencing data. |

Experimental Workflow: From Sequencing to Discovery

The diagram below outlines a robust workflow for a rare variant association study, from data generation through to meta-analysis and interpretation.

Analysis Workflow: Statistical Methods for Gene-Based Tests

Once summary data is prepared, the core of a rare variant association study involves applying specialized gene-based statistical tests. The diagram below illustrates the logical relationships between the main classes of tests.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the key advantage of using extreme phenotype sampling for rare variant studies? Extreme phenotype sampling (EPS) significantly increases statistical power for detecting rare variant associations. This design enriches the sample with causal rare variants; individuals at the tails of a phenotypic distribution are more likely to carry these variants. One study found a much stronger association signal (P=0.0006) when using a sample of 701 phenotypic extremes compared to a sample of 1,600 randomly selected individuals (P=0.03) for the same trait and gene [21].

2. My rare variant association test has inflated type I error. What could be the cause? Type I error inflation is a common challenge, particularly for low-prevalence binary traits and in studies with highly unbalanced case-control ratios [17]. This can also occur due to population stratification, where rare variants can reflect fine-scale population structure that standard adjustment methods may not fully account for [2]. Using methods specifically designed to handle these issues, such as those employing saddlepoint approximations, is crucial [17].

3. Should I use a burden test or a variance-component test like SKAT for my analysis? The choice depends on the assumed genetic architecture of your trait:

- Burden tests are most powerful when most of the rare variants in your region are causal and their effects on the trait are in the same direction [4] [2].

- Variance-component tests (e.g., SKAT) are more robust and powerful when a large proportion of variants are non-causal or when causal variants have effects in opposite directions (e.g., both risk and protective) [4] [22].

- Combined tests (e.g., SKAT-O) offer a middle ground, often providing robust power across various scenarios [4] [22].

4. How can biobanks with linked electronic health records (EHRs) enhance rare variant studies? EHR-linked biobanks provide deep longitudinal clinical data on large cohorts, enabling researchers to:

- Define and validate phenotypes for a wide range of diseases using clinical codes, lab values, and medication records [23].

- Achieve large sample sizes necessary for well-powered rare variant analyses more efficiently and cost-effectively than prospective cohort studies [23].

- Study diverse populations and conditions that are often underrepresented in traditional research cohorts [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Statistical Power in Rare Variant Association Analysis

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Inefficient Study Design.

- Solution: Implement an Extreme Phenotype Sampling (EPS) design. Power can be substantially greater in rare variant studies using EPS compared to random sampling [21] [22]. For continuous traits, use methods that analyze the full continuous phenotypic values rather than dichotomizing them, as this retains more information and increases power [22].

Cause: Small Sample Size for Rare Variants.

- Solution: Utilize large biobanks (e.g., UK Biobank, All of Us) that provide the scale needed [24] [23]. If a single cohort is insufficient, consider a meta-analysis to combine summary statistics from multiple studies. Methods like Meta-SAIGE are designed for this purpose and can achieve power comparable to analyzing pooled individual-level data [17].

Cause: Suboptimal Variant Filtering or Weighting.

- Solution: Incorporate variant functional annotations (e.g., predicted deleteriousness) to prioritize likely causal variants. Using informed variant weights in tests like SKAT or burden tests can also improve power [2].

Issue 2: Controlling False Positives (Population Stratification)

Problem: Rare variants can be recent and geographically localized, leading to confounding by fine-scale population structure [2].

Recommended Actions:

- Genetic Principal Components (PCs): Include a larger number of genetic PCs as covariates in your model compared to common variant analyses [4] [2].

- Linear Mixed Models (LMMs): Use methods that employ LMMs to account for sample relatedness and underlying structure. The SAIGE method and its derivatives (SAIGE-GENE, Meta-SAIGE) are specifically designed for this in the context of rare variants and binary traits [4] [17].

- Family-Based Designs: For robust control of confounding, consider family-based association tests (FBATs) or Transmission Disequilibrium Tests (TDTs), which are inherently robust to population stratification [4].

Issue 3: Analyzing Data from Multiple Cohorts (Meta-Analysis)

Challenge: Combining gene-based rare variant test results from different studies while controlling type I error and maintaining computational efficiency.

Step-by-Step Protocol using Modern Methods:

Preparation (Per Cohort):

- Use SAIGE to perform single-variant association analyses for each cohort. This generates per-variant score statistics (S) and their variances, accurately controlling for case-control imbalance and relatedness [17].

- Generate a sparse linkage disequilibrium (LD) matrix (Ω) for each gene or region of interest. Meta-SAIGE allows this LD matrix to be reused across all phenotypes, drastically reducing computational costs for phenome-wide analyses [17].

Summary Statistics Consolidation:

- Combine the per-variant score statistics and LD matrices from all contributing cohorts into a single superset.

- Apply the Genotype-Count-based SaddlePoint Approximation (GC-SPA) to the combined statistics. This step is critical for maintaining correct type I error rates for low-prevalence binary traits [17].

Gene-Based Association Testing:

- Perform Burden, SKAT, and SKAT-O tests on the combined summary statistics.

- Collapse ultrarare variants (e.g., those with a minor allele count < 10) to boost power and computation efficiency [17].

- Use the Cauchy combination method to combine P values from different functional annotations and MAF cutoffs for a final gene-based test result [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Resources for Rare Variant Association Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank [24] | Population Biobank | Provides deep genetic (genotyping, WES) and phenotypic data for ~500,000 individuals, enabling large-scale discovery. |

| All of Us [17] [23] | Population Biobank | Aims to build a diverse US cohort of >1M participants with genomic data and EHR linkages. |

| SAIGE / SAIGE-GENE+ [17] | Software Tool | Performs single-variant and gene-based rare variant tests, accurately controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness. |

| Meta-SAIGE [17] | Software Tool | Conducts scalable rare variant meta-analysis using summary statistics from multiple cohorts, with accurate type I error control. |

| SKAT/SKAT-O [4] [22] | Statistical Method | A variance-component test for set-based rare variant association, robust to the presence of non-causal and opposite-effect variants. |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Study Design and Analysis Workflow

Meta-Analysis Computational Pipeline

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key technological differences between WES, WGS, and genotyping arrays? Genotyping arrays probe a predefined set of hundreds of thousands of common variants across the genome. Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) targets and sequences the protein-coding regions (exons), which constitute about 1-2% of the genome. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) sequences the entire genome, capturing both coding and non-coding variation [25] [26] [27].

Q2: For rare variant analysis, should I use a single-variant test or a gene-based aggregation test? The choice depends on the underlying genetic architecture. Single-variant tests are generally more powerful for detecting associations with individual, high-impact rare variants. Gene-based aggregation tests (such as Burden or SKAT tests) pool signals from multiple rare variants within a gene and are more powerful only when a substantial proportion of the aggregated variants are causal and have effects in the same direction. The performance is strongly dependent on the sample size, region heritability, and the specific variant mask used (e.g., including only protein-truncating and deleterious missense variants) [28].

Q3: Does WGS offer a significant advantage over WES for discovering rare variant associations in large-scale studies? Current empirical evidence from large biobanks suggests that for a fixed sample size, the discovery yield for rare variant associations is very similar between WGS and a combined strategy of WES plus imputation from arrays (WES+IMP). Although WGS identifies about five times more total variants than WES+IMP, nearly half are singletons (variants found in only one individual) that are underpowered for association testing. The number of detected association signals for 100 complex traits differed by only about 1% between the two approaches [25] [27].

Q4: What is the primary advantage of a larger sample size versus a more comprehensive sequencing technology? Sample size is a critical driver of discovery power for rare variants. One study found that increasing the sample size for WES+IMP analysis from ~47,000 to ~468,000 individuals (a 10-fold increase) led to an approximately 20-fold increase in association signals. Given that WES+IMP is typically less expensive per sample than WGS, allocating resources to sequence a larger sample with WES+IMP can often yield more discoveries than sequencing a smaller sample with WGS [25] [27].

Q5: What is haplotype phasing and why is it important for rare variant analysis? Haplotype phasing involves distinguishing the two parentally inherited copies of each chromosome. This is crucial for identifying compound heterozygous events, where two different rare mutations knock out both copies of a gene, a common model for recessive rare diseases. Accurate phasing of rare variants enables the screening for such events in large cohorts [29].

Q6: When is WGS clearly preferred over WES in a clinical or research setting? WGS is preferred when the analysis requires the detection of variants in non-coding regions, such as regulatory elements or deep intronic regions, or for the comprehensive identification of structural variants. It is particularly valuable in rare disease diagnosis for families where WES has failed to provide a diagnosis, as it can uncover pathogenic non-coding variants that WES would miss [11] [26] [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconclusive results from a genotyping array in a rare disease case.

- Potential Cause: Microarrays are designed to detect known common variants and large copy number variations (CNVs). They have limited resolution for small insertions/deletions (indels), cannot detect novel rare variants not on the array, and offer poor coverage of non-coding regions [30].

- Solution: Proceed to a sequencing-based test. Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) is a comprehensive next-step, as it can identify rare and novel single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small indels in the coding regions where most known disease-causing variants are located [30].

Problem 2: Low statistical power in a rare variant association study.

- Potential Cause: The carrier count for individual ultra-rare variants is too low for single-variant tests to achieve statistical significance [28] [27].

- Solution:

- Employ gene-based aggregation tests: Collapse rare variants within a gene (e.g., all predicted loss-of-function variants) and test the combined burden of the gene. This increases power by effectively increasing the carrier count for the gene unit [28] [27].

- Increase sample size: Consider a meta-analysis to combine summary statistics from multiple cohorts. Methods like Meta-SAIGE are designed to control type I error rates and can achieve power comparable to a pooled analysis of individual-level data [17].

- Optimize the variant mask: Ensure you are aggregating variants most likely to be functional (e.g., protein-truncating and deleterious missense) to increase the proportion of causal variants in the test [28].

Problem 3: Difficulty interpreting the clinical significance of a prioritized rare variant.

- Potential Cause: A typical WES or WGS analysis generates a large number of rare variants, and manual review is time-consuming.

- Solution: Use a variant prioritization tool like Exomiser/Genomiser. Systematically evaluate the impact of key parameters for optimization [11]:

- Input high-quality phenotypic data: Provide a comprehensive and accurate set of the patient's clinical features using Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms.

- Leverage gene-phenotype associations: Ensure the tool uses up-to-date databases linking genes to diseases.

- Apply appropriate variant pathogenicity predictors: Select and combine scores that are well-calibrated for your variant type (e.g., missense, non-coding).

- Incorporate family segregation data: When available, input genotype data from related affected and unaffected individuals to assess co-segregation with the disease.

Platform Comparison and Selection

Table 1: A quantitative comparison of data generation platforms based on UK Biobank analyses. [25]

| Feature | Genotyping + Imputation (IMP) | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | WES + IMP (Combined) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate Total Variants | ~111 million [25] | ~17 million [25] | ~599 million [25] | ~126 million [25] |

| Coding Variants | Limited to those in reference panel | ~10.5 million [25] | ~6.7 million [25] | ~6.8 million [25] |

| Variant Type | Common variants (MAF >0.1-1%) | Rare coding variants | Rare & common variants, coding & non-coding | Common genome-wide & rare coding variants |

| Singleton Proportion | Very Low | ~48% (of coding variants) [25] | ~47% (of all variants) [25] | ~7% (of all variants) [25] |

| Association Yield (100 traits in ~150k samples) | Lower than sequencing | Similar to WGS [25] | ~3,534 signals (baseline) [25] | ~3,506 signals (1% fewer than WGS) [25] |

Table 2: A functional comparison to guide platform selection. [31] [26] [30]

| Aspect | Genotyping Arrays | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strengths | Cost-effective for very large cohorts; excellent for common variant GWAS. | Focuses on coding regions (~85% of known disease variants); high depth enables sensitive rare variant calling; lower cost than WGS. | Comprehensive view; detects all variant types anywhere, including non-coding and structural variants. |

| Major Limitations | Limited to pre-defined variants; poor for rare/novel variants; cannot phase de novo. | Misses non-coding and regulatory variants; capture efficiency can lead to coverage gaps and biases. | High cost per sample; massive data storage/analysis burden; challenging interpretation of non-coding variants. |

| Ideal Use Case | Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of common variants in large populations. | Identifying rare coding variants associated with complex diseases or finding causative mutations in Mendelian disorders. | Discovery of non-coding variants, comprehensive structural variant detection, and unresolved rare disease cases. |

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Protocol 1: Accurate Phasing of Rare Variants in Large Cohorts using SHAPEIT5 [29]

Application: This protocol is used for haplotype phasing of large-scale whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing data, which is a prerequisite for analyses like compound heterozygous mutation screening and genotype imputation.

Methodology: SHAPEIT5 uses a three-stage approach to achieve high accuracy, especially for rare variants:

- Common Variant Phasing: Common variants (MAF > 0.1%) are first phased using an optimized SHAPEIT4 algorithm, which is highly accurate for common variants in large sample sizes. The resulting haplotypes form a "scaffold."

- Rare Variant Phasing: Each rare heterozygous variant (MAF < 0.1%) is phased onto the scaffold haplotypes using an imputation-based model. For a given rare variant, the method identifies a set of conditioning haplotypes that are (a) locally identical-by-descent (IBD) with the target sample and (b) carry the minor allele. The Li and Stephens model is then used to determine the most likely phase.

- Singleton Phasing: Singletons (variants with a minor allele count of 1) are phased using a coalescent-inspired model that leverages IBD sharing patterns. The model assumes singletons are recent mutations and assigns them to the target haplotype that shares the shortest IBD segment with others.

Protocol 2: Gene-Based Rare Variant Meta-Analysis with Meta-SAIGE [17]

Application: This protocol enables the meta-analysis of gene-based rare variant association tests (e.g., Burden, SKAT, SKAT-O) across multiple cohorts without sharing individual-level data. It is designed to control type I error rates effectively, even for low-prevalence binary traits.

Methodology:

- Step 1 - Cohort-Level Preparation: For each cohort, use SAIGE to generate per-variant score statistics (S) and their variances, accounting for sample relatedness and case-control imbalance. Also, generate a sparse linkage disequilibrium (LD) matrix (Ω) for variants in the gene/region. This LD matrix is not phenotype-specific and can be reused across different traits.

- Step 2 - Summary Statistics Combination: Combine the per-variant score statistics from all cohorts. For binary traits, apply a two-level saddlepoint approximation (SPA): first on the score statistics of each cohort, and then a genotype-count-based SPA on the combined statistics to ensure accurate type I error control.

- Step 3 - Gene-Based Testing: Perform gene-based Burden, SKAT, and SKAT-O tests using the combined score statistics and covariance matrix. Ultrarare variants (e.g., MAC < 10) can be collapsed to improve power and computation efficiency. Finally, use the Cauchy combination method to combine P values from different functional annotations and MAF cutoffs.

Table 3: Key software tools and resources for rare variant analysis.

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHAPEIT5 [29] | Haplotype Phasing | WGS/WES data processing | Provides high accuracy for rare variants and singletons; essential for compound heterozygote detection. |

| Meta-SAIGE [17] | Rare Variant Meta-Analysis | Multi-cohort association studies | Controls type I error for unbalanced case-control traits; reuses LD matrices for computational efficiency. |

| SAIGE/SAIGE-GENE+ [17] | Single-Variant & Gene-Based Tests | Single-cohort association analysis | Uses SPA to control for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large biobanks. |

| Exomiser/Genomiser [11] | Variant Prioritization | Rare disease diagnosis | Ranks variants by integrating genotype, pathogenicity predictions, and patient HPO phenotype terms. |

| REGENIE [25] | Genome-Wide Association | Large-scale regression | Used for efficient single-variant and gene-based association tests on quantitative and binary traits. |

A Practical Pipeline for Rare Variant Association Testing

Variant Quality Control (QC) and Annotation Best Practices

Variant Quality Control (QC) and annotation form the critical foundation of rare variant analysis research, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of genetic findings. In rare disease research and drug development, stringent QC processes are essential for distinguishing true pathogenic variants from technical artifacts, while comprehensive annotation provides the biological context needed for clinical interpretation. This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face during these processes and provides evidence-based solutions to improve diagnostic yield and research validity.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Why is my diagnostic variant not ranked highly by prioritization tools like Exomiser?

Problem: Diagnostic variants are ranked outside the top candidates in variant prioritization tools, potentially causing them to be missed during manual review.

Solutions:

- Optimize prioritization parameters: Systematically evaluate and adjust key parameters including gene-phenotype association data, variant pathogenicity predictors, and phenotype term quality. One study demonstrated that parameter optimization improved Exomiser's performance for genome sequencing data from 49.7% to 85.5% for top-10 ranking of coding diagnostic variants [11].

- Enhance phenotype data quality: Provide comprehensive, accurate Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms. The number and quality of HPO terms significantly impact prioritization performance. Avoid randomly sampled or incomplete phenotype terms [11].

- Verify family data inclusion: Ensure proper inclusion and accuracy of family variant data in PED format files, as familial segregation patterns strengthen variant prioritization [11].

- Apply complementary tools: For cases with suspected regulatory variants, use Genomiser alongside Exomiser. One study showed optimization improved noncoding variant ranking in the top 10 from 15.0% to 40.0% [11].

How can I resolve memory errors during variant calling and annotation workflows?

Problem: Workflows encounter memory errors during aggregation steps, particularly for genes with high variant counts or longer genes.

Solutions:

- Increase memory allocation: For problematic genes (e.g., RYR2, SCN5A), adjust memory parameters as shown in the table below [32]:

Table 1: Memory Allocation Adjustments for Problematic Genes

| Workflow Component | Task | Default Memory | Adjusted Memory |

|---|---|---|---|

quick_merge.wdl |

split | 1GB | 2GB |

quick_merge.wdl |

firstroundmerge | 20GB | 32GB |

quick_merge.wdl |

secondroundmerge | 10GB | 48GB |

annotation.wdl |

filltagsquery | 2GB | 5GB |

annotation.wdl |

annotate | 1GB | 5GB |

annotation.wdl |

sumandannotate | 5GB | 10GB |

- Adjust CPU and queue settings: Increase CPU cores for computationally intensive tasks and use appropriate queue types (short vs. medium) based on job requirements [32].

- Monitor specific genes: Be particularly aware of known problematic genes including TNNI3, KIF1A, ACTN2, PRKAG2, RYR2, SCN5A, CRELD1, and BBS10, which often require additional resources [32].

Why does my autosomal variant show hemizygous calls (ACHemivariant > 0)?

Problem: Autosomal variants display haploid (hemizygous-like) calls despite not being on sex chromosomes.

Explanation and Solution:

- Understand the mechanism: These haploid calls indicate that the variant is located within a deletion on the other chromosome for the same sample. They originate from single-sample gVCFs, not the aggregation procedure [32].

- Review adjacent variants: Check for nearby deletions that might explain the haploid call pattern [32].

- Worked example: As illustrated in the table below, a haploid ALT call at position chr1:2118756 can be explained by a heterozygous 2bp deletion immediately upstream (chr1:2118754-2118755) [32]:

Table 2: Example of Haploid Calls from Adjacent Deletions

| CHROM | POS | REF | ALT | GT | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr1 | 2118754 | TGA | T | 0/1 | 2bp deletion called as heterozygous |

| chr1 | 2118755 | G | . | 0 | Reference call, haploid due to deletion |

| chr1 | 2118756 | A | T | 1 | ALT call, haploid due to deletion |

What quality metrics should I check for SNP array data in quality control?

Problem: Determining which quality metrics and thresholds ensure reliable copy number variant (CNV) detection in SNP array data.

Solutions:

- Verify call rates: Maintain call rates between 95% and 98% for SNP array data. Call rate represents the percentage of SNPs successfully assigned a genotype out of the total probes on the array [33].

- Utilize B-allele frequency and log R ratio: These key values in GenomeStudio help detect chromosomal aberrations. B-allele frequency shows the allele ratio, while log R ratio indicates intensity deviations that suggest copy number changes [33].

- Detect copy-neutral LOH: Leverage SNP array's unique ability to identify copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH), which cannot be detected by traditional G-banding [33].

- Combine with traditional methods: Use SNP array analysis alongside G-banding, which remains valuable for detecting balanced translocations and provides a whole-genome overview [33].

When should I use WGS instead of WES for rare variant detection?

Problem: Deciding between whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES) for optimal detection of diagnostically challenging variants.

Solutions:

- Select WGS for technically challenging variants: WGS demonstrates superior capability in detecting variants that are technically intractable to WES, including: variants in low-coverage regions with PCR bias, deep intronic variants, repeat expansions, structural variants, and variants in genes with homologous pseudogenes [34].

- Consider WGS as first-line testing: One study found that WGS provided causative variants in 42.9% of patients with high clinical suspicion of rare disorders, with 21.7% of these attributable to technically challenging variants missed by other methods [34].

- Implement comprehensive analysis: Employ PCR-free short-read WGS and comprehensive analytical pipelines to maximize variant detection across the entire genome [34].

- Evaluate diagnostic yield: Research shows WGS can serve as an all-in-one test for patients with high clinical suspicion of rare diseases, potentially ending diagnostic odysseys [34].

Experimental Protocols

Optimized Variant Prioritization Protocol Using Exomiser/Genomiser

Purpose: To systematically prioritize coding and noncoding variants in rare disease cases using optimized parameters.

Methodology:

- Input Preparation:

- Collect multi-sample family variant call format (VCF) files

- Prepare corresponding pedigree file in PED format

- Encode patient clinical presentations using Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms

Parameter Optimization:

- Adjust gene-phenotype similarity algorithms

- Optimize variant pathogenicity score thresholds

- Set appropriate frequency filters based on population databases

- Configure mode of inheritance patterns

Execution and Refinement:

- Run Exomiser for coding variants and Genomiser for regulatory variants

- Apply p-value thresholds to refine outputs

- Flag genes frequently ranked in top 30 but rarely associated with diagnoses

- Combine results from both tools for comprehensive variant prioritization [11]

Standardized Clinical Bioinformatics Pipeline for WGS

Purpose: To ensure clinical consensus, accuracy, reproducibility, and comparability in diagnostic WGS.

Methodology:

- Data Processing:

- De-multiplex raw sequencing output (BCL to FASTQ)

- Align sequencing reads to reference genome hg38 (FASTQ to BAM)

Variant Calling:

- Call SNVs and small insertions/deletions (indels)

- Detect copy number variants (CNVs), structural variants (SVs), short tandem repeats (STRs)

- Identify loss of heterozygosity (LOH) regions indicating uniparental disomy (UPD)

- Call mitochondrial SNVs and indels using tailored approaches

Quality Assurance:

- Verify data integrity using file hashing

- Confirm sample identity through fingerprinting and genetically inferred markers

- Perform automated quality checks within the analysis pipeline

- Utilize standard truth sets (GIAB for germline, SEQC2 for somatic variant calling)

- Supplement with recall testing of real human samples previously tested with validated methods [35]

Table 3: Key Recommendations for Clinical Bioinformatics Production

| Category | Recommendation | Implementation Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | Adopt hg38 genome build | Use as standard reference for all analyses |

| Variant Calling | Use multiple tools for structural variant calling | Complement standard SNV/indel calling with specialized SV callers |

| Quality Control | Implement in-house datasets for filtering recurrent calls | Maintain laboratory-specific artifact databases |

| Technical Standards | Operate at standards similar to ISO 15189 | Utilize off-grid clinical-grade high-performance computing systems |

| Reproducibility | Ensure containerized software environments | Use Docker or Singularity for consistent software versions |

| Data Integrity | Verify through file hashing and sample fingerprinting | Implement genetic relatedness checks and sex inference [35] |

Table 4: Performance Improvements Through Parameter Optimization in Exomiser

| Sequencing Type | Default Top-10 Ranking | Optimized Top-10 Ranking | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Sequencing (Coding) | 49.7% | 85.5% | +35.8% |

| Exome Sequencing (Coding) | 67.3% | 88.2% | +20.9% |

| Noncoding Variants (Genomiser) | 15.0% | 40.0% | +25.0% [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Variant QC and Annotation

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Exomiser/Genomiser | Prioritizes coding and noncoding variants | Open-source; integrates allele frequency, pathogenicity predictions, HPO terms |

| GenomeStudio with cnvPartition | Analyzes SNP array data for CNV detection | User-friendly interface for researchers with minimal bioinformatics expertise |

| Global Screening Array v3.0 | SNP array platform for chromosomal aberration detection | Suitable for quality control of hPSCs; detects CNVs >350 kb |

| Clinical Genome Analysis Pipeline (CGAP) | Processes WGS/WES data in cloud environment | Compatible with Amazon Web Services; produces per-sample GVCF files |

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | Extracts genomic DNA for SNP array processing | Provides high-quality DNA for accurate genotyping |

| Sentieon | Jointly calls variants across samples | Used for processing cohort-level sequencing data [11] [33] [35] |

Workflow Diagrams

Variant Analysis and QC Workflow

Rare Variant Analysis Framework

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary advantage of using gene-based analysis units over single-variant tests for rare variants? Gene-based analysis units aggregate multiple rare variants within a functional region, which increases statistical power. Single-variant tests for rare variants are often underpowered due to low minor allele frequencies, whereas methods like burden tests and SKAT combine evidence across multiple variants in a gene [36] [37]. Aggregation tests are particularly more powerful when a substantial proportion of the aggregated variants are causal and have effects in the same direction [28].

2. When should I consider using a sliding window approach instead of a gene-based unit? Sliding window approaches are particularly valuable for exploring associations in non-coding regions of the genome, where functional units are not as clearly defined as genes. This method systematically analyzes the genome in contiguous segments, allowing for the discovery of associations outside of known gene boundaries [38]. This is crucial in whole-genome sequencing studies for identifying novel, non-coding rare variant associations.

3. How does the choice of analysis unit impact the control of Type I error? The choice of analysis unit and the subsequent statistical method must account for data characteristics like case-control imbalance. For binary traits with low prevalence, some meta-analysis methods can exhibit inflated Type I error rates. Methods like Meta-SAIGE employ statistical adjustments, such as saddlepoint approximation, to accurately estimate the null distribution and control Type I error, regardless of the analysis unit used [17].

4. What are the common factors that lead to loss of power in gene-based burden tests? Power loss in burden tests typically occurs when the aggregated rare variants include a mix of causal variants with opposing effect directions (bidirectional effects) or when a significant number of neutral (non-causal) variants are included in the unit. This cancels out association signals and dilutes the statistical power [36] [28]. Careful variant selection through functional annotation is key to mitigating this.

5. How can functional annotations be integrated into the definition of analysis units? Functional annotations, such as predicting whether a variant is protein-truncating or deleterious, can be used to create more refined analysis units or to weight variants within a unit. For example, you can define a unit to include only protein-truncating variants (PTVs) and deleterious missense variants within a gene, which increases the prior probability that variants in the unit are causal and can boost power [28] [37]. Frameworks like STAAR and MultiSTAAR systematically integrate multiple functional annotations into association testing [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inflated Type I Error in Meta-Analysis of Binary Traits

Issue: When meta-analyzing rare variant associations for a low-prevalence binary trait (e.g., a disease with 1% prevalence), your results show an inflated Type I error rate, leading to false positive associations.

Solution:

- Root Cause: Standard meta-analysis methods can fail to accurately estimate the true null distribution when case-control ratios are highly imbalanced.

- Steps for Resolution:

- Utilize Robust Methods: Implement meta-analysis methods specifically designed to handle case-control imbalance. The Meta-SAIGE method, for example, employs a two-level saddlepoint approximation (SPA) to accurately estimate the null distribution [17].

- Apply Genotype-Count SPA: Ensure the method includes a genotype-count-based SPA for the combined score statistics from all cohorts in the meta-analysis. This additional adjustment is critical for controlling Type I error in low-prevalence settings [17].

- Verify with Simulation: If possible, conduct a small-scale simulation using your study's genotype data and phenotype structure to confirm that the chosen method controls Type I error adequately before proceeding with the full analysis.

Problem: Low Power in Gene-Based Aggregation Tests

Issue: Your gene-based rare variant association test is not identifying significant associations, despite a prior belief that a gene is involved.

Solution:

- Root Cause: Power is low because the aggregated variants contain many non-causal variants or causal variants with effects in opposite directions.

- Steps for Resolution:

- Refine Your Variant Mask: Instead of aggregating all rare variants, restrict your analysis unit to variants with a higher prior probability of being functional. Focus on protein-truncating variants (PTVs) and deleterious missense variants, using annotations from tools like popEVE [28] [39].

- Choose an Adaptive Test: Switch from a simple burden test to an omnibus test like SKAT-O or a method that combines p-values from different masks and tests (e.g., using the Cauchy combination method). These tests are more robust to the presence of non-causal variants and bidirectional effects [17] [40].

- Check Genetic Model Parameters: Use available resources (like the R Shiny app from [28]) to understand the power of aggregation tests under different assumptions. Power is strongly dependent on the proportion of causal variants (

c), the total number of variants (v), and the region-wide heritability (h2) [28].

Problem: Handling Population Structure and Relatedness in Large-Scale WGS

Issue: Analyses in large-scale whole-genome sequencing (WGS) studies, which often include related individuals or multiple ancestries, may yield spurious associations due to population stratification or cryptic relatedness.

Solution:

- Root Cause: Standard regression models assume individuals are unrelated, and violations of this assumption can inflate test statistics.

- Steps for Resolution:

- Use Mixed Models: Apply statistical frameworks that can account for sample relatedness. Methods like SAIGE and MultiSTAAR use generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) that incorporate a genetic relationship matrix (GRM) to adjust for relatedness and population structure [17] [38].

- Incorporate Principal Components: Include leading principal components from genetic data as covariates in your model to control for broad-scale population structure [37].

- Employ Functional Informed Frameworks: For multi-trait analysis in diverse cohorts, use frameworks like MultiSTAAR that are explicitly designed to account for relatedness, population structure, and correlation among phenotypes simultaneously [38].

Methodological Comparison of Analysis Units

Table 1: Key characteristics and applications of different analysis units in rare variant studies.

| Analysis Unit | Definition | Best Use Cases | Common Statistical Tests | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Aggregates variants within the boundaries of a gene. | Testing the cumulative effect of rare variants on protein function; exome-wide association studies. | Burden, SKAT, SKAT-O [36] [37] | Power depends heavily on the proportion of causal variants within the gene [28]. |

| Pathway | Aggregates variants across multiple genes that share a common biological function. | Identifying subtle polygenic effects spread across a biological system; generating hypotheses on disease mechanisms. | Often uses gene-based p-value combination methods. | Requires well-annotated pathway databases; interpretation can be complex. |

| Sliding Window | Analyzes the genome in small, contiguous, and overlapping segments. | Discovering associations in non-coding regions; whole-genome sequencing studies without pre-defined hypotheses. | Burden, SKAT, STAAR [38] | Computationally intensive; requires careful multiple-testing correction. |

Table 2: Strategic selection of statistical tests for different genetic models within an analysis unit.

| Genetic Model Scenario | Recommended Test | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| All or most aggregated rare variants are causal and have effects in the same direction. | Burden Test [28] [40] | Maximizes power by pooling effects, assuming a unidirectional model. |

| Mixture of causal and non-causal variants, or causal variants have effects in opposite directions. | Variance-Component Test (e.g., SKAT) [28] [40] | Robust to the inclusion of neutral variants and bidirectional effects. |

| The underlying genetic model is unknown (a common real-world scenario). | Omnibus Test (e.g., SKAT-O) [17] [37] | Adaptively combines burden and variance-component tests to achieve robust power across various scenarios. |

Experimental Protocols for Unit Definition

Protocol 1: Defining and Testing Gene-Based Units with Functional Annotations

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for conducting a gene-based rare variant association analysis, incorporating functional annotations to increase power.

- Variant Quality Control (QC): Start with high-quality sequencing or imputed data. Filter out variants with low call rate, deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, or poor imputation quality [37].

- Variant Annotation: Annotate all variants using bioinformatics tools. Prioritize functional consequences (e.g., synonymous, missense, protein-truncating) and use pathogenicity prediction scores from tools like popEVE [39] [6].

- Define Gene Units and Masks: For each gene, create one or more "masks" (variant sets). A common strategy is to create masks for:

- All rare variants (MAF < 0.01).

- Only protein-truncating variants (PTVs).

- PTVs and deleterious missense variants.

- Association Testing: For each gene and mask, perform rare variant association tests. It is recommended to run an omnibus test like SKAT-O, which is robust to different genetic models [17].

- P-value Combination: If multiple masks were tested per gene, combine the p-values using a method like the Cauchy combination test to generate a single, aggregate p-value for the gene [17].

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply a multiple testing correction (e.g., Bonferroni) across all tested genes to control the family-wise error rate.

Protocol 2: Conducting a Sliding Window Analysis in Non-Coding Regions

This protocol is designed for scanning the entire genome for rare variant associations outside of protein-coding genes.

- Define Window Parameters: Set the size of the window (e.g., 5 kb) and the step size (e.g., 2.5 kb). A smaller step size creates more overlap, reducing the chance of missing a signal at a window boundary.

- Tiling the Genome: Systematically slide the window across all autosomes and sex chromosomes, creating a comprehensive set of non-overlapping or overlapping analysis units [38].

- Variant Inclusion: Within each window, aggregate all rare variants (e.g., MAF < 0.01) that pass QC.

- Association Testing: Perform a rare variant association test (e.g., burden or SKAT) for each window. Computational efficiency is critical here due to the vast number of units tested.

- Functional Annotation of Significant Windows: For windows that show significant association, annotate the region using databases like ENCODE to check for regulatory elements (e.g., enhancers, promoters) that may indicate biological relevance [37].

- Multiple Testing Correction: Use a stringent multiple testing correction method, such as Bonferroni or a permutation-based approach, to account for the millions of tests performed.

Workflow Diagram for Analysis Unit Selection

Diagram 1: A workflow to guide the selection of analysis units and statistical tests based on study goals and genetic models.

Table 3: Key computational tools and data resources for defining and analyzing rare variant units.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| popEVE [39] | AI Prediction Tool | Scores each genetic variant for its likelihood of being disease-causing, enabling cross-gene comparison and variant prioritization for masks. |

| gnomAD [6] | Population Frequency Database | Provides allele frequency data across diverse populations to filter out common variants unlikely to cause rare diseases. |

| ClinVar [6] | Clinical Annotation Database | A public archive of reports on the relationships between human variants and phenotypes, with supporting evidence. |

| SKAT/SKAT-O [17] [37] | Statistical Test Software | R packages for performing powerful and flexible rare variant association tests for genes, regions, or windows. |

| Meta-SAIGE [17] | Meta-Analysis Software | A scalable tool for rare variant meta-analysis that controls Type I error and boosts computational efficiency. |

| ACMG-AMP Guidelines [6] | Classification Framework | A standardized system for interpreting the clinical significance of sequence variants (Pathogenic, VUS, Benign). |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental principle behind a burden test? Burden tests operate on the core principle of aggregating, or "collapsing," multiple rare genetic variants within a gene or genomic region into a single burden score for each individual. This score is then tested for association with a trait or disease, under the assumption that the aggregated rare variants collectively influence the phenotype, typically in the same direction. This approach increases statistical power for detecting associations that would be too weak to detect with single-variant tests for very rare variants [41] [42] [43].

When should I choose a burden test over a single-variant test or SKAT? The choice of test depends heavily on the assumed genetic architecture of the trait [44] [43].

- Burden tests are most powerful when a substantial proportion of the aggregated rare variants are causal and their effects on the trait are in the same direction (e.g., all are deleterious). They can lose power if many variants are non-causal or if effects are bidirectional [45] [44].

- Single-variant tests are often more effective when only a very small number of rare variants in a region are causal [44].

- Variance-component tests like SKAT are more powerful when a large fraction of variants are non-causal or when causal variants have effects in different directions (both risk-increasing and protective) [45] [46]. Hybrid tests like SKAT-O were developed to combine the advantages of burden and SKAT, providing robust power across various scenarios [45] [17].

How do I define the variant set or "mask" for my burden test? Defining the variant set is a critical step. A "mask" specifies which variants to include based on criteria such as [44]:

- Variant Function: Prioritize variants with likely high impact on protein function, such as protein-truncating variants (PTVs) or putatively deleterious missense variants.

- Allele Frequency: Use a minor allele frequency (MAF) threshold (e.g., MAF < 0.01 or 0.001) to focus on rare variants. It is common to test multiple masks (e.g., PTVs only, PTVs + deleterious missense) across a range of frequency thresholds to explore different biological hypotheses [47].

I've heard burden tests can be sensitive to population stratification. How can I control for this? Population stratification is a major confounder. Best practices to address it include [41]:

- Covariate Adjustment: Include principal components (PCs) derived from genetic data as covariates in your regression model to account for ancestral differences.

- Genetic Relatedness Matrix: Use mixed models (as implemented in tools like REGENIE or SAIGE) that incorporate a genetic relatedness matrix to account for sample relatedness and fine-scale population structure [17].

- Calibration with Synonymous Variants: Using presumably benign synonymous variants to calibrate the test can help guard against false positives caused by technical artifacts or stratification [41].

What should I do if my burden test results are highly correlated across different masks? When testing multiple, highly correlated burden scores (e.g., the same annotation class at different frequency thresholds), interpretation and multiple testing correction can be challenging. One solution is to use methods that jointly test the set of burden scores. For example, the Sparse Burden Association Test (SBAT) uses a non-negative least squares approach to jointly model burden scores, which also induces sparsity and can aid in selecting the most relevant frequency bin and annotation class [47].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inflated Type I Error in Case-Control Studies

- Symptoms: Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) plot shows genomic inflation (lambda >1). An unacceptable number of false positive associations are observed in negative control tests.

- Solution: This is a common issue in studies of binary traits, especially with low prevalence and case-control imbalance [17].

- Use Adjusted Methods: Employ software specifically designed to handle case-control imbalance. Meta-SAIGE uses a two-level saddlepoint approximation (SPA) to accurately estimate the null distribution and control type I error [17].

- Check LD Matrix Construction: If performing meta-analysis, ensure the linkage disequilibrium (LD) matrix is appropriately calculated. Using a single, study-wide sparse LD reference file that is rescaled for each phenotype can be both computationally efficient and accurate [48].

Problem: Low Power to Detect Associations

- Symptoms: Known associated genes do not appear significant in your analysis. Power calculations suggest an inability to detect effect sizes of interest.

- Solution:

- Increase Sample Size: Power for rare variants is profoundly dependent on sample size. Consider meta-analysis to combine summary statistics from multiple cohorts. Tools like REMETA and Meta-SAIGE are designed for scalable rare variant meta-analysis [48] [17].

- Re-evaluate Your Mask: The chosen variant mask might not optimally capture the causal variants. Try different functional annotations and frequency cut-offs. If you have a priori knowledge that effects are likely bidirectional, switch from a pure burden test to SKAT or SKAT-O [45] [44].

- Leverage Public Controls: For very rare diseases, sequencing large control cohorts may be infeasible. Using publicly available control databases like gnomAD is a viable strategy, but requires careful harmonization of variant calling and quality control to avoid artifacts. The TRAPD software provides a framework for this approach [41].